?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Gender diversity in the board has recently become the most intensely deliberated and scrutinized corporate governance aspect, especially its linkage with various corporate economic outcomes following numerous corporate scandals as a results of weak governance mechanisms. This empirical work examined association between board gender diversity (BGD), efficiency and risk-taking behavior (RTB) of insurers in Kenya over 8 year’s period from 2013 to 2020 using a dynamic data analysis model on a Kenyan sample of 53 insurers. The findings confirm a significant inverse association between BGD and RTB. The study also reports an insignificant negative association with risk taking, despite showing that generally insurers are technically inefficient. The study, therefore, suggests that boards with relatively higher proportions of women have lower propensity for risk taking. The outcomes have implications for the shareholders on the potential benefits of women on board in reducing propensity for risk taking among insurers. With regard to regulatory and policy implications, the findings support the argument for policy formulation and regulations on gender quotas in both public and private insurance firms. This is particularly valuable in emerging countries where corporate governance is at nascent stage. The study recommends that future studies could extend the scope to determine the optimal gender mix as well as broaden the studies to cover gender inclusivity among the top executives and embrace additional BGD variables.

1. Introduction

Insurance firms make significant contribution to the total gross domestic product of a country like any other financial intermediary and are, therefore, viewed as an irresistible device of economic advancement for emerging economies. The insurers contribute to economic development through financial intermediation, risks pooling and provision of other additional financial services (Danquah et al., Citation2018). Boamah et al. (Citation2021) highlight that efficient intermediation by financial institutions enhances financial performance, thus resulting in efficient utilization of resources. As such, efficient insurance firms create financial stability which is necessary in economic growth of a country (Shair et al., Citation2019). However, efficient undertaking of insurance business activities is motivated by risk-taking incentives or expected returns without which there will be no risk taking. Yet, Muhammad et al. (Citation2022) affirm that the outcome of taking excessive risk may be undesirable with adverse consequences such as insurance failure and, therefore, analysis of the factors which impinge on the insurer’s governance and the incentives for managerial risk-taking is critical to safeguard against wealth misappropriation. As such, Fama and Jensen (Citation1983) and Mgammal (Citation2022) emphasize that the board of directors (BOD) is a vital corporate governance (CG) device for harmonizing the diverse interests of various parties in the firm. In this regard, Alves (Citation2023) and Sarhan et al. (Citation2019) underscore the significance of BGD as a CG mechanism for safeguarding investors’ wealth.

Although risk taking is indispensable for enhanced performance for the insurance firms, it follows that extreme risk taking may nonetheless endanger their survival and financial health. Bsoul et al. (Citation2022) opine that the corporate success and sustainability are contingent on the RTB of the BOD. Consequently, the emphasis of this article is on the link between BGD, technical efficiency and RTB of insurers. This line of research is stimulated by the documented empirical evidence from psychological and behavioral economics studies such as Peltomäki et al. (Citation2021) on impact of gender-based differences on risk tolerance. Similarly, Bin Khidmat et al. (Citation2020) contend that diversity in demographics of the members of the board introduces competitiveness, creativeness, monitoring and supervisory capabilities, and superior financial choices. Indeed, Dong et al. (Citation2017) recently affirmed that a larger percentage of females on boards profoundly impact governance dynamics, although its influence on firm RTB is not forthright. In the same line of thought, Gyapong et al. (Citation2019) submit that stakeholders have lately underscored the need for enhanced BGD in response to extant empirical literature showing BGD influences efficiency of the board.

The agency theory (AT) offers a platform that illuminates the discourse on the association between CG mechanisms such as BGD and corporate outcomes such as risk taking. For instance, Muhammad et al. (Citation2022) employing AT recommend appointment of diverse boards of directors as a mitigating governance device. Similarly, resource-dependency theory (RDT) postulates a favorable linkage between board diversity, predominantly BGD, and corporate outcomes. In agreement with AT and RDT perspectives, the upper echelons theory (UET) proposes that managerial characteristics and inclinations impact corporate policy selections such as RTB (Bsoul et al., Citation2022; Perryman et al., Citation2016) and other strategic decisions (Ahmed et al., Citation2019). The gender-based risk-taking behavioral variations suggested by UET are widely recognized in previous empirical literature in experimental economics and psychology (Peltomäki et al., Citation2021). It can, therefore, be claimed that inclusion of female members on boards strengthens BODs independence and thus promotes its oversight role in safeguarding the owners’ interests. Nevertheless, budding empirical literature is inconclusive with regard to whether the female presence on the boards is significantly different from male representation and affinity for taking risk.

Gender inclusivity in the board, therefore, has recently become the most intensely deliberated (Bogdan et al., Citation2022; Sanyaolu et al., Citation2022) and scrutinized CG aspect, especially its linkage with numerous metrics of corporate performance (Saeed et al., Citation2021). Several studies have explicated how BGD might affect risk-taking behavior of firms. For instance, Levin et al. (Citation1988) demonstrate that females are extra cautious when making critical decisions and extra cautious in taking risk (Bernile et al., Citation2018). Further, women abhor being allied to firms which engage in fraudulent activities in contrast to male contemporaries (Gao et al., Citation2017). This raises the empirical question on whether the BGD should impact the firm’s risk-taking behavior, yet the proponents of perfect capital markets framework contend that managerial traits are irrelevant in the investment selection process (Faccio et al., Citation2016). In contrast, UET, agency and other traditional finance theorists support the view that managerial traits and those of the shareholders are important in making investment choice. For example, Jizi and Nehme (Citation2017), in support of AT, underscore the merits of BGD in enhancing CG and consequently reducing preferences for extreme risk-taking. Additionally, Amin et al. (Citation2022) observe that females make decisions involving less risk in comparison to male colleagues.

The prior empirical literature on boardroom diversity has emphasized the importance of BGD in creation of efficient boards (Alves, Citation2023; Ararat & Yurtoglu, Citation2021). Board diversity has, however, been put on the spotlight in the CG debate following numerous corporate scandals as a result of weak governance mechanisms (Adusei et al., Citation2017; Al-Jaifi et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, empirical works on the BGD–risk-taking behavior nexus are still controversial. Several previous studies document evidence showing an inverse linkage of females existence in boardroom and corporate risk taking (Abou-El-Sood, Citation2019; Gulamhussen & Santa, Citation2015; Harjoto et al., Citation2018; Jizi & Nehme, Citation2017; Muhammad et al., Citation2022; Sbai & Ed Dafali, Citation2023). In contrast, some authors report evidence of direct association between proportions of women members of board and RTB (Chatjuthamard et al., Citation2021; Safiullah et al., Citation2022). Yet, others find insignificant linkage of women representation on boardroom and RTB (Bruna et al., Citation2019). This is congruent with Nguyen et al. (Citation2020) who document insignificant linkage of BGD and risk taking from several studies in their systematic literature review. Therefore, there is a lack of unanimity in the extant empirical evidence regarding the involvement of women and men on board level of risk aversion in making corporate financial decisions. Thus, it is plausible to review the BGD and RTB relationship using recent Kenyan insurers’ dataset, a different geographical region as a pathway to reconcile the contentious empirical findings.

Generally, Brady et al. (Citation2011) observe that the fraction of females occupying top managerial positions and membership of boards is inexplicably small. Consequently, policy-makers in several countries have implemented gender-centered quota system in board formation, notably Denmark, Norway, France, Finland, Iceland, Spain and Iceland. Similarly, in Kenya, the Constitution 2010 requires that all appointments in public institutions should not comprise greater than two-thirds of the identical gender, but there is no legislation for appointments in private institutions. Despite many studies in finance and economics literature focusing on gender diversity, riskiness and performance of a firm, Elisa and Guido (Citation2020) contend that the debate has shifted to question whether the rising participation of females in leadership can affect economic outcomes of financial firms. Furthermore, Kirkpatrick (Citation2009) indicted that managers in the financial institutions were taking extreme risk which was identified as a key trigger for the 2007 to 2009 financial crisis. This article examines the unresolved empirical question of participation of women in top leadership and incentives to take risks, particularly in the insurance sector from an emerging country perspective.

Maheshe (Citation2021) observes that a high number of entities appreciate that a workforce that is well gender-diversified is a foundation for competitive advantage. Similarly, Nguyen et al. (Citation2020) indicate that despite women experiencing certain gender-based challenges in appointment to board membership, they contribute more to corporate performance. However, Fraser-Moleketi et al. (Citation2015) document evidence from 307 listed firms operating in 12 African countries showing that Africa ranks third on women representation on boardrooms among topmost listed firms following the US and Europe, yet Africa is leading other emerging countries in inclusion of women in boardrooms. Particularly, they reported that women members in boardrooms in the listed corporations operating in 12 African countries was 12.7% compared to 17.3% in biggest global firms. Further, the reports generally indicated that majority of the listed corporations in Africa exhibit low women representation in boardrooms with Kenya having the highest proportion of women representation on boards at 19.8% followed by South Africa (17.4%) and Botswana (16.9%). Interestingly, women form slightly above half of the rising Africa’s population, yet they also comprise the bulk of the poor since the mainstream economic activities for about 70% of the women is in the informal sector. There are a few women participating in corporate boards in African countries as is the case globally, except in those countries, which have implemented policy intervention on women inclusivity in boardrooms. Faccio et al. (Citation2016) argue this “gender gap” in top leadership is a chronic problem which is widespread across many global corporations. This observation elicits the question whether presence of male or female board members has implications for risk-taking incentives and, are there implications for the firm efficiency on RTB?

Consequently, this study contributes to the embryonic scientific literature on corporate control in manifold ways. First, this is one of the few studies focusing on the link between BGD, efficiency and the RTB in the insurance industry, which is unexpectedly scarcely explored. As aforementioned, the scarcity of studies focusing on managerial traits such as women participation on boards (Nguyen et al., Citation2020), efficiency of firm and risk nexus, taken together with the mixed and inconclusive previous empirical results motivate this study with the aim to document empirical evidence on this association from insurance firms’ in Kenya, an emerging market. The paper also offers new intuitions into the linkage between BGD as a CG device and firm RTB. Further, the paper provides insights on the impact of insurers’ efficiency and their risk-taking incentives. This paper thus extends and augments the burgeoning literature on BGD-efficiency-RTB nexus in the context of Kenyan insurance firms.

Second, although extant literature presents some publications in the area of BGD and risk-taking incentives, there are limited published works from emerging economies such as Kenya, particularly from the insurance industry. For instance, Claessens and Yurtoglu (Citation2013) indicate that extant literature on CG in emerging markets focuses mostly on banks performance and other listed firms. Equally, Sila et al. (Citation2016) decry lack of studies focusing on female boardroom membership and incentives for firms to take risk. Therefore, this paper complements and extends the work of previous scholars on BGD, efficiency and RTB, contextually as well as geographically in response to the call for more country-based research by Elisa and Guido (Citation2020) and Khatib et al. (Citation2021) from emerging financial markets where little is known regarding governance practices and risk behavior. Finally, the study uses two-step dynamic panel, system GMM methodology towards control of any probable endogeneity problems which enriches the quality of the study results.

The rest of the article is structured to cover a brief explanation of the theoretical literature in section 3, prior empirical literature review and hypothesis development are discussed in section 4 and the general methodology implemented by the study is reported in section 5. This is then followed by presentation of empirical findings and discussions in section 6, and finally results are summarized and conclusions drawn in section 7.

2. Background

The Insurance Regulatory Authority (IRA) licenses insurance players in Kenya and had licensed 61 insurance and reinsurance firms by end of the year 2020. The IRA industry report for 2021 indicates that the Kenyan insurance industry makes contribution to the economy through provision of financial security, mobilising savings and promoting investments. Further, IRA reported that 10 insurers were financially penalized for non-compliance with guidelines and there was a rise in number of complaints lodged by policy holders from 1,637 in 2020 to 1,686 in 2021. Largely, these observations are indicators of governance inefficiencies among the insurers, in spite of the application of the CG guidelines by IRA since 2011.

In 2021, IRA reported that the Kenyan insurance industry combined net profit considerably grew by 56.5% in 2021. During the same period, Kenya was placed in fourth position in Africa in relations to gross premium income. Similarly, insurance penetration increased to 2.24% in 2021 from 2.17% 2020, although this is far below the world average insurance penetration of 7.0%. Despite the improved industry performance, there are numerous complaints from policy holders, non-compliance with industry governance guidelines and some firms were either put on statutory management (e.g. Blue Shield Insurance Company and United Insurance Company Limited) or were under liquidation (e.g. Standard Assurance Company Limited and Concord Insurance Company). This then leads to the question of whether the improved performance is as a result of extreme risk-taking behavior of the boards and how it relates to the board gender diversity and efficiency.

Kenya is, therefore, ideal for a study on BGD component of CG to evaluate the outcome of women involvement in boardrooms on corporate risk taking following the Fraser-Moleketi et al. (Citation2015) revelation that out of the 12 countries included in their study on women’s participation on boards of topmost listed firms in Africa, Kenya had the greatest proportion of women directors (19.8%). This percentage of women on boards is, however, low considering that the Kenyan Constitution 2010 requires that all appointments in public institutions and enterprises should not comprise greater than two-thirds of the identical gender, demonstrating the government intention for more inclusive boards, although, there is no legislation for appointments in private institutions. It is, therefore, intuitive to establish the contribution of the female directors from the Kenyan insurance corporate boards with the view of influencing policy to enhance women inclusivity in boards in view of the current media, political and academic debate on gender equality quotas. This is congruent with Al-Jaifi et al. (Citation2023) argument that board diversity especially gender attributes has only been subject to limited studies prompting regulators in developed or emerging countries to require boards to reinforce their board gender diversity.

3. Theoretical literature review

The complexity of the theoretical development linking the study on the nexus between BGD, efficiency and firm RTB requires a multi-theoretical framework. The paper employs UET, RDT and AT as seen in Muhammad et al. (Citation2022) and Bin Khidmat et al. (Citation2020).

3.1. Agency theory

This theory presents the conflicts of interest that subsist among the owners (principals) and the management (agents). Thus, AT offers a platform that illuminates the association between CG devices such as board configuration and organization outcomes such as risk taking. In order to alleviate the dissonance of interest and the associated agency challenges such as asymmetric information amongst the corporate stakeholders, Muhammad et al. (Citation2022) recommend appointment of diverse boards of directors (BOD) as a mitigating governance device. This theory perceives BOD as a vital governance stratagem that can create harmony among the interested stakeholders such as the owners, management among others, especially the idea of enhancing variety in management positions (Bogdan et al., Citation2022).

It can therefore be claimed that inclusion of female members on boards strengthens their independence (Ntim, Citation2015) and thus promotes BODs oversight role in safeguarding the owners’ interests. Similarly, Saeed et al. (Citation2021) observe that BGD is a cradle of knowledge and capability which is needed in evolving corporate strategic decisions especially on risk-taking. As such, Bernile et al. (Citation2018) affirm that BGD improves board objectivity, monitoring capabilities and efficiency which influences CG positively, which in turn reduces firm risk-taking. The fundamental thrust of this article, therefore, is to determine the role of BGD on enhancing independence of the board as suggested in literature that BGD is beneficial in enriching monitoring capability of the board to minimize management expropriation of shareholders wealth.

3.2. Resource-dependency theory

Previously, the theory of agency was used to explain BGD-RTB linkage, but RDT has lately gained significant consideration in illustrating this association (Tyrowicz et al., Citation2020). The RDT is a theoretical foundation which views BOD as a resource to the firm. The survival and continuity of a firm, therefore, depends on its linkage with the external business environment with the view of accessing external resources (Pfeffer & Salancik, Citation1978). Proponents of this theory focus on nomination of independent representatives of other entities as a pathway for accessing critical inputs for the success of the firm such as competencies, information, and linkage to strategic partners such as consumers, policy-makers, dealers and gaining acceptability of the larger community. According to RBT, gender diversity is a major component of the governance devices for strengthening board efficiency by leveraging on female members unique talents, opinions, capabilities and addition of novel dynamics during board discussions (Jamali et al., Citation2006).

RDT is viewed by Bogdan et al. (Citation2022) as a major theoretical base supporting the formation of diverse BOD. For example, Ramadan and Hassan (Citation2021) underscore the importance of female directorship to promote BGD as a means of accessing a combination of resources which are critical in the operation of the firm. Hillman et al. (Citation2009) also endorse larger diversity arguing that it is necessary in sourcing for vital exterior resources translating to superior decisions and modest risk taking. The existing previous empirical literature notably by Byrnes et al. (Citation1999) illustrates that gender-diverse board is linked with wider viewpoints, greater level of innovations and creativity as well as superior risk mitigation. Women on board improve the linkage among firms’ stakeholders which is essential in improving board functionalities such as judicious decision-making and managing risk of the firm (Brammer et al., Citation2007).

3.3. Upper echelons theory

The UET illuminates the debate on the role of managerial traits such as attitudes, experiences, knowledge, characteristic and individual inclinations on corporate outcomes such as efficiency, risk- taking among others. Proponents of the UET as suggested by Hambrick and Mason (Citation1984) propose that managerial characteristics and inclinations impact corporate policy selection (Bsoul et al., Citation2022; Perryman et al., Citation2016), outcomes and other strategic decisions (Ahmed et al., Citation2019). The gender-based risk-taking behavioral variations are widely recognized in previous empirical literature in experimental economics and psychology (Peltomäki et al., Citation2021). Accordingly, the management team gender traits and architecture is anticipated to significantly impact on decisions made in corporate entities from the viewpoint of UET (Bogdan et al., Citation2022).

Existing literature show that womenfolk are generally risk averse compared to the male contemporaries (Dwyer et al., Citation2002; Palvia et al., Citation2020). This observation is attributed to women having lower experience levels than their male colleagues. In support of UET, Chatjuthamard et al. (Citation2021) in their study established that managers’ incentives for risk taking are influenced by the degree of boards gender inclusivity. Moreover, Bernile et al. (Citation2018) demonstrate that women exercise caution when making critical and risky corporate choices. Further, Gao et al. (Citation2017) affirm that women abhor being allied to firms which engage in fraudulent activities in contrast to male contemporaries. Despite the plethora of papers in psychology and economics showing that females have lower risk inclination as compared to men (Borghans et al., Citation2009; Watson & McNaughton, Citation2007), UET is critiqued due to its ambiguity in explaining whether participation on boards by a larger proportions of women would translate to firms engaging in reduced risk taking (Sila et al., Citation2016).

4. Empirical literature review and hypotheses development

4.1. Board gender diversity and insurance firms’ risk-taking

BGD is the existence of women on top management and directorship of business entities (Elisa & Guido, Citation2020). Gender diversity according to Milliken and Martins (Citation1996) is a vital ingredient of an efficient board and other scholars such as García and Herrero (Citation2021) have indicated that women are more diligent, independent and responsible as compared to men. Muhammad et al. (Citation2022) opine that the global discourse towards enhanced gender inclusivity at the place of work has recently gained traction. Extant literature demonstrates that inclusion of women on board enhances monitoring capability which favorably impacts on governance as well as corporate performance. Additionally, women are more cautious when making critical decisions (Levin et al., Citation1988) and extra cautious in taking risk (Bernile et al., Citation2018). Further, women abhor being allied to firms which engage in fraudulent activities in contrast to male contemporaries (Gao et al., Citation2017). This raises the empirical question on whether the BGD should impact the firm’s risk-taking behavior yet, the proponents of perfect capital markets framework contend that managerial traits are irrelevant in the investment selection process (Faccio et al., Citation2016). In contrast, UET, agency and other traditional finance theorists support the view that managerial traits and those of the shareholders are important in making investment choice. For example, Jizi and Nehme (Citation2017), in support of AT, underscore the merits of BGD in enhancing CG and consequently reducing preferences for extreme risk-taking. Additionally, Amin et al. (Citation2022) observe that females make decisions involving less risk in comparison to male colleagues.

The differences in gender risk inclinations and appetite are extensively recognized in the literature on behavioral economics and cognitive psychology (Palvia et al., Citation2020). Nonetheless, empirical works on the BGD-risk-taking behavior nexus are still controversial. Several previous studies document evidence showing an inverse linkage of females existence in boardroom and corporate risk-taking (Abou-El-Sood, Citation2019; Gulamhussen & Santa, Citation2015; Harjoto et al., Citation2018; Jizi & Nehme, Citation2017; Muhammad et al., Citation2022; Sbai & Ed Dafali, Citation2023). In contrast, some authors report evidence of direct association between proportions of women members of board and RTB (Chatjuthamard et al., Citation2021; Safiullah et al., Citation2022). Yet, others find insignificant linkage of women representation on boardroom and RTB (Bruna et al., Citation2019). This is reinforced by Nguyen et al. (Citation2020) who report insignificant linkage of BGD and risk taking in their systematic review of literature. Therefore, there is a lack of unanimity in the extant empirical evidence regarding the involvement of women and men on board level of risk aversion in making corporate financial decisions.

Several scholarly works have explored the effect of women contribution in boardrooms on corporate outcomes. In a study of banking institutions in Germany for the duration 1994–2010, Berger et al. (Citation2014) present evidence showing that increase in female participation in boardrooms raises their portfolio risk. This observation is attributed to women having lower experience levels than their male colleagues. Similarly, Chatjuthamard et al. (Citation2021) in their study established that gender-diversity acts as an incentive for taking additional risk by the managerial team. Another strand of literature such as Elisa and Guido (Citation2020) supports inverse linkage between gender of 312 Italian financial institutions’ executives and their risk-taking behavior, demonstrating that females exhibit lower propensity for risk. Similarly, Mohsni et al. (Citation2021) in their cross-country research reported inverse association between BGD and financial risk. Collectively, these studies support the view that inclusion of women on board resolves the agency problems such as reduction in information asymmetries and promote investor’s confidence (García & Herrero, Citation2021). Following the findings of numerous studies, recommendations by IRA on formation of diversified BOD consistent with the AT claim that inclusion of women members on boards strengthens their independence, UET position that womenfolk are generally risk averse and RDT support for the formation of diverse BOD to enhance access for external resources, the study therefore tests the hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1:

BGD of insurance firms is inversely related to their risk-taking behavior.

4.2. Efficiency and firm risk-taking

The efficiency and RTB studies in financial institutions predominantly focus on the commercial and investment banking sector (Alam, Citation2012; Fiordelisi et al., Citation2011; Tan et al., Citation2021). Notwithstanding the developing scholarly interest on governance and corporate performance both in emerging and developed worlds, there is a paucity of studies focusing on BGD as a CGM, efficiency and RTB in insurance industry. The dearth of efficiency risk-taking studies in insurance industry cannot be explained owing to the economic importance of the insurance industry. However, the latest growth in the literature dealing with the efficiency and risk in banks can support in circumventing this problem.

Recently, Ofori-Sasu et al. (Citation2022) have, however, provided empirical evidence that increased risk-taking lowers the efficiency of insurers using 40 Ghanaian insurance firms for the period 2008–2017. Largely, existing empirical evidence in banking industry suggests that well-diversified boards provide efficient governance which may result to a lower propensity for risk. Dong et al. (Citation2017) argue that a strengthened board structure would minimize agency conflicts in a firm translating to improved choice of inputs and outputs which then enhances efficiency which lowers risk-taking behavior. Similarly, Meles and Starita (Citation2013) argue that according to moral hazard hypothesis, information asymmetry reduces efficiency levels of insurers which increases insurers’ risk-taking. Further, the bad management hypothesis as applied in banking efficiency studies proposes that reduced efficiency translates to increased expenses (inputs) and consequently increased risk affinity (Tan et al., Citation2021). Therefore, the study tests the hypothesis that higher gender inclusivity on insurers corporate boards promotes better monitoring of insurance managers as proposed by both AT and RDT, hence improving efficiency and lowering risk of insurers as follows:

Hypothesis 2:

The efficiency of insurance firms is inversely associated with the risk-taking behavior.

5. Research design

5.1. Data and selection of the sample

The study targeted all the 61 insurance firms registered by IRA as at 31 December 2020. However, eight firms which were excluded from the study, where four of the firms were licensed to operate in Kenya from 2018 and the other four firms did not have complete data set for CG and/or the required financial aspects for the 8-year period. The article, therefore, gathered panel data from 53 insurance firms which were certified by Insurance Regulatory Authority (IRA) to operate in Kenya and had complete data. The selection of the sample is summarized in Table . The data were extracted from audited financial statements for 8-year duration (2013–2020) and the industry annual reports published by the Kenyan Insurance Regulatory Authority.

Table 1. Selection of the sample

5.2. Variables of the study

5.2.1. Risk-taking behavior

This study measures the RTB of insurance businesses by calculating Z score on ROA and ROE, i.e. a measure of solvency as seen in numerous earlier research such as Saeed et al. (Citation2021), Akbar et al. (Citation2017) and Houston et al. (Citation2010). Z score on ROA (RTB1) is determined as follows:

While Z score on ROE (RTB2) is determined as follows:

ROA represents each company net income/overall assets; ROE represents each company net income/overall equity; is the proportion of overall equity to overall assets and

and

are the dispersions of the insurance company ROA and ROE, respectively, in standard deviations.

The Z score is directly connected to the stability of the insurance firm and it inversely proxy RTB. The study focuses on the volatility of ROA instead of security market returns due to almost all the targeted insurance companies in Kenya being privately owned.

The study also used leverage (RTB3) to proxy financial risk taking since it considers the risk of financing decisions, i.e. greater degree of leverage intensifies the financial risk by increasing the odds of debt default as used by other scholars, for example Mohsni et al. (Citation2021) and Saeed et al. (Citation2021). Leverage was, thus, determined as overall firm debt divided by overall firm assets as used in the aforementioned studies.

5.2.2. Board gender diversity

The BGD was determined as a fraction of directors who are women to the board membership. This approach is congruent with former similar works, notably Dwaikat et al. (Citation2021), Sbai and Ed Dafali (Citation2023), Bogdan et al. (Citation2022), among others.

5.2.3. Efficiency estimation

Efficiency estimation focuses on the identification of the DMUs with the best conversion of inputs into outputs to act as the model for the inefficient DMUs (Alhassan & Biekpe, Citation2015). From extant literature, two methodologies specifically DEA (non-parametric) and SFA (parametric) have prominently featured for estimation of efficiency (Cummins et al., Citation1999; Eling & Jia, Citation2019). This study employs DEA since previous literature proposes that DEA efficiency scores are more superior to other frontier approaches for efficiency estimation among insurers (Eling & Jia, Citation2019; Jaloudi & Bakir, Citation2019). DEA efficiency scores vary from 0 and 1 where 1 signifies the greatest efficiency and 0 signifies inefficient firm. Thus, any efficiency score below 1 indicates inefficiency with the the difference between a DMU efficiency score and 1 representing the firm’s potential for efficiency improvement.

The input–output variables employed in this paper for estimation of efficiency are as indicated in Table . These variables were identified following previous empirical works in DEA efficiency measurement by Al‐Amri et al. (Citation2012), Jaloudi and Bakir (Citation2019) and Diacon et al. (Citation2002).

Table 2. Inputs and outputs variables used in DEA efficiency analysis

5.2.4. Control variables

The study employed the following board characteristics and firm-specific control variables: lag of the risk-taking behavior, size of the board, board independence, chief executive officer duality, intensity of board activity, audit quality, firm age and size consistent with previous works on CG which shows that risk taking can be affected by firm characteristics and CG control variables which were measured as indicated in Table .

Table 3. Measurement of study variables

5.3. Econometric model

The paper recognizes the need to precisely determine the effect of BGD and TE on RTB of insurers taking into consideration the endogeneity of these variables. Several earlier studies, for example Akbar et al. (Citation2017), García and Herrero (Citation2021), Elsaid and Ursel (Citation2011) and Li and Zhang (Citation2019), indicate that corporate board architecture is determined endogenously and therefore previous results of a vast majority of papers suffer from endogeneity problem. For example, Dong et al. (Citation2017) observe that the probability of reverse causality where the current BGD and efficiency may be determined by the past levels of corporate risk causes the endogeneity problem. The paper thus adopts a two-step dynamic panel system (DPS) GMM model as seen in similar scholarly work by Akbar et al. (Citation2017) and Bruna et al. (Citation2019). The application of DPS-GMM provides more robust results by addressing the potential problem of unobserved heterogeneity, dynamic endogeneity and simultaneity which would otherwise results in significantly biased estimations.

The following econometric equation is estimated:

is the predicted variable (Z score and Leverage),

and

are the first and second lags for RTB. The study uses the first and second lags Z-risk for the RTB, while for leverage, the study uses the first lag only. BGD denotes board gender diversity, TE represents technical efficiency,

are CG control variables,

are insurance-firm-specific control variables,

denotes unobserved firm effect and

is the estimation error term. Table presents a summary of study variable measurements. This study assumes that BGD, TE, CG and firm characteristics control variables are endogenous excluding age of the firm and year dummies which are exogenous as seen in Wintoki et al. (Citation2012).

5.4. Model specifications tests

The study followed the approach employed by Akbar et al. (Citation2017) to establish the necessary lags for inclusion in the estimation model. The study regressed each of the three proxies of risk on three lags of the previous year RTB, besides the predicted and control variables. The findings of this analysis indicated that two lags were significant for RTB1 and RTB2 where risk was measured as Z score of ROE and ROA, respectively. In contrast, only one lag was found to be significant for the RTB3 where leverage was used as the measure of risk. Therefore, two lags were deemed adequate to address the dynamic effect for Z-risk and one lag for leverage based risk in estimating the DPS- GMM.

To confirm whether indeed the model was correctly specified, the paper conducted two post-estimation tests as recommended by Roodman (Citation2009) and successfully employed in similar other studies, for example Bruna et al. (Citation2019). First, the study conducted AR1 and AR2 to look for the existence of the first-order and the second-order residuals’ correlation, respectively. Specifically, the first-order correlation (AR1) may be present but the second-order (AR2) correlation need to be absent. Secondly, the study employed the Hansen test to confirm that all instrumental variables are jointly valid. Roodman (Citation2009) recommends that the probability results of the Hansen test should lie between 0.05 and 0.8, and the optimum value lies between 0.1 and 0.25.

6. Empirical results and discussion

The descriptive results on the risk-taking behavior of the insurers “management (dependent variables), independent variables, control variables and dynamic panel system GMM models” statistical analyses results are provided in the preceding sections.

6.1. Descriptive statistics

The summary findings for the 8-year period are as presented in Table . With regard to the dependent variable, risk-taking behavior, the mean Z score using ROA (RTB1) was 5.40 and decreased from 6.32 in 2013 to 4.61 in 2019 and then marginally improved to 5.13 in 2020. Similar trends were observed for the mean Z score using ROE (RTB2) and leverage (RTB3) as measures of risk taking. This indicates that the insurers risk taking increased during the study period, whereas their stability diminished.

Table 4. Insurers descriptive statistics for the period 2013–2020

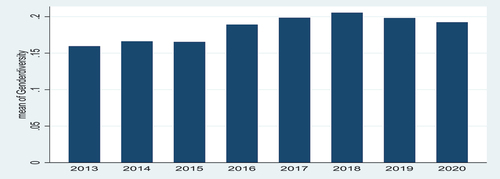

The BGD had a mean of 0.184 (18.4%), with a maximum of 0.5 (50%) and minimum of zero. This observation is not surprising that a number of insurers have no female representation whereas others have up to 50% female representation since there is no legal or CG code prescribing minimum level of women representation for private and public firms’ corporate boards in Kenya. The percentage of women in boardroom grew from an average of 0.159 (15.9%) in 2013 to a high of 0.205 (20.5%) in 2018 and then marginally declined to 0.198 and 0.192 in 2019 and 2020, respectively, as shown in Figure . The findings on the average female representation on Kenyan insurance boards affirm the results of Fraser-Moleketi et al. (Citation2015) study of 307 listed firms operating in 12 African countries which documented that Kenya had the highest women directors on board at 19.8%. The observed average gender diversity of 18.4% is way below the two-thirds (30%) threshold in public institutions appointment prescribed by the Kenyan Constitution 2010. However, the Kenyan Constitution 2010 does not address gender inclusivity in private institutions yet majority of the insurers are privately owned.

The average technical efficiency among the insurers in Kenya over the 8-year study period was 0.348 (34.8%) with a standard deviation of 0.2429 (24.3%), indicating technical inefficiency. Generally, the mean technical efficiency was volatile during the study period, fluctuating between 38.99% in 2013 and the lowest figure of 30.02% in 2015, to highest level of 42.14% in 2016, dropped to low figure of 30.84% in 2018 and remained below the average TE at 32.31% in 2020.

6.2. Correlation analysis

Appendix I shows the findings on pairwise correlation among study variables. The correlation matrix indicates low correlation coefficients among the variables ruling out any potential multicollinearity among the variables since all the coefficients had a value lower than the recommended maximum of 0.8 by Gujarati and Porter (Citation2008).

6.3. Regression analysis and discussions

The summary results of the inferential findings of the connection between risk-taking behavior, BGD, efficiency and selected control are presented in Table that are in line with the study hypotheses. The study regresses risk 1 (Z score ROA), risk 2 (Z score ROE) and risk 3 (proxied using leverage) on gender diversity, efficiency and the control variables using two step DPS-GMM model with corrected standard errors to mitigate against any probable endogeneity problems.

Table 5. DPS-GMM regression analysis results

As indicated in Table , BGD is significant and directly linked to Z score ROA at 5% significance level. Similarly, BGD is significant and directly linked to Z score ROE at 10% significance level. These findings indicate that increase in gender diversity among Kenyan insurers enhances their financial stability and consequently reduces their risk taking, i.e. there exists an inverse relation between BGD and RTB1 and TTB2 measured using reciprocal of Z score. This observation is collaborated by significant inverse relationship between BGD and the third proxy for risk taking (leverage) at 5% significance level. The negative association illustrates that an increase in BGD weakens the RTB of the management board. All the three measures of RTB empirically confirm the first hypothesis that BGD of insurance firms is inversely related to their risk-taking behavior.

The results complement empirical evidence that has recently been documented by similar studies, such as Elamer et al. (Citation2018), Adams and Ferreira (Citation2009), Sbai and Ed Dafali (Citation2023), Gulamhussen and Santa (Citation2015), Muhammad et al. (Citation2022) and Palvia et al. (Citation2020), which documented negative linkage between women membership on board and RTB. The results, therefore, uphold the AT argument that inclusion of females on boardrooms enhances CG mechanisms by strengthening boards’ independence, objectivity, monitoring capabilities and efficiency, and thus diminishes the affinity for extreme risk-taking. The outcomes also agree with the RDT view that women on board are a vital resource which improves the linkage among firms’ stakeholders to enhance board functionalities such as judicious decision-making and risk management (Brammer et al., Citation2007). However, the results disagree with a few studies which report direct association between BGD and RTB, for example Safiullah et al. (Citation2022). The finding also supports UET view on existence of gender-based risk-taking behavioral variations as previously confirmed by Chatjuthamard et al. (Citation2021) in their study which established that managers’ incentives for risk-taking are influenced by the degree of boards gender inclusivity. The study finding resonates with the Kenyan Constitution 2010 requirement for all appointments in public institutions to comprise one-third of women. Further, the IRA may consider policy reform on the CG guidelines in order to strengthen formation of diverse BOD through gender-oriented diversity in recognition of the potential benefits of inclusion of women on board demonstrated in this study.

The article documents negative but insignificant relationship between technical efficiency of insurers and the risk-taking behavior as proxied using all the three aforementioned measures, i.e. Z score of ROA, Z score of ROE and leverage. Therefore, the study findings in Table fail to support second hypothesis on an inverse significant link between efficiency of insurance firms and the risk-taking behavior. Nonetheless, the reported evidence suggest that technically inefficient firms may result in a higher disposition for risk taking. This empirical evidence contradicts suggestion by Dong et al. (Citation2017) that enhanced efficiency for the banking industry lowers RTB, which is consistent with AT propositions.

Lastly, in connection to the control variables, the BS had a positive significant connection with both ZROA and ZROE measures of risk-taking behavior and a significant negative relationship with leverage of insurance at 5% significance. This implies that large insurance companies’ boards create financial stability and ultimately reduce risk taking possibly due to the benefits of diversity in expertise. Both intensity of board activity and audit quality were significantly and inversely associated with ZROE and ZROA measures of risk-taking behavior and a significant positive relationship with leverage of insurance at 10% significance. Also, board independence, CEO duality, firm age and firm size had insignificant effect on risk-taking behavior for all the three risk-taking models.

Table also gives the findings for the residuals autocorrelation tests. According to the findings, first-order serial correlation was present; nonetheless, second-order correlation of the residuals was absent. Also the validity of the instruments of the study was confirmed by Hansen test suggesting that previous risk-taking behavior, gender diversity, efficiency and selected control variables were exogenous. Generally, all the three models’ overall goodness of fit was found to be significant with P < 0.05.

6.4. Robustness analysis

To validate the sensitivity of the outcomes, the study used alternate measure for BGD as seen in Sbai and Ed Dafali (Citation2023). BGD was also determined using Blau index (BI) which was calculated as ; R is the portion of females and males membership of the board for the ith insurance firm. The study also employed a different regression analysis model (2SLS) as a substitute to system dynamic GMM regression to further confirm robustness of the findings and address any potential endogeneity problem which is expected to arise in CG studies as highlighted in recent academic debate. The results of robustness check are as shown in Tables .

Table 6. DPS-GMM regression analysis for alternative results

Table 7. Instrumental variables (2SLS) regression

The results for DPS-GMM analysis using the alternate measure of BGD (BI) are shown in Table . Interestingly, the findings for different risk measures show that gender diversity retained the signs of the coefficients and significance as formerly described in Table , affirming that the outcomes are robust. Additionally, the outcomes of the 2SLS regression analysis as reported in Table are similar to the DPS-GMM outcomes formerly reported in Table .

7. Summary and conclusion

The paper looked at the influence of BGD and efficiency on RTB of insurers in Kenya over 8 year’s period from 2013 to 2020 using a dynamic panel system GMM approach. The study reported significant inverse link between BGD and RTB. As a consequence, the study concludes that boards with relatively higher proportions of women have lower propensity for risk taking. This is congruent with prior conclusions documented by Sbai and Ed Dafali (Citation2023), Harjoto et al. (Citation2018), and Muhammad et al. (Citation2022). Indeed, these empirical outcomes support the UET proponents’ view that women by and large are averse to risk, resulting in gender-based risk-taking behavioral variations. Further, the study supports the suggestion by agency theorists that inclusion of women on boards strengthens board’s independence and thus promotes their oversight role in safeguarding the interests of the stakeholders. However, this outcome contradicts the recent new insights by Safiullah et al. (Citation2022) from a Spanish sample which showed that firms with higher female directorship take more risks, discounting the hitherto available evidence, which is supported by this article that female executives are averse to risk.

With regard to insurers’ technical efficiency, the study reports an insignificant negative association with risk taking. Possibly, the converse relationship could be plausible as shown in a recent publication by Ofori-Sasu et al. (Citation2022) that increased risk taking lowers the efficiency of Ghanaian insurers. Despite the insignificant relationship, the reported evidence suggest that technically efficient firms may result in a lower inclination for risk taking. This reinforces the necessity for corporate boards’ reforms to enhance their efficiency in the light of the documented technical inefficacies among the Kenyan insurers to lower risk of insurers.

Following the growing global pressure to embrace gender inclusivity on corporate boards and other appointments, this paper has some implications for practice and policy. First, it gives insights to the shareholders on the potential benefits of women representation on board in reducing propensity for risk taking in the insurance industry from an emerging market perspective. Second, it makes contribution to the budding academic debate on the desirable impact of the corporate decision-makers’ demographic orientations, especially gender diversity on economic outcomes of financial institutions such as insurers. Third, this study pioneers in focusing on gender inclusivity, efficiency and risk-taking behavior among insurers in East Africa region and contributes to the scanty reservoir of knowledge in this area. Particularly, the findings support the application of DPS-GMM as a remedy for controlling endogeneity problems in studies on CG. Finally, with regard to regulatory and policy implications, the findings showing reduced firm risk ensuing from higher level of women representation in line with the upper echelon and agency theoretical frameworks support the argument for policy formulation and regulations on gender quotas in both public and private insurance firms. The policy intervention will serve as an important avenue towards encouraging insurers to embrace more gender inclusivity in their boardrooms to minimize risk taking and promote firm financial stability for the benefit of all the insurance industry stakeholders. This is particularly valuable in emerging countries where CG is at nascent stage of development in order to minimize agency conflicts and promote shareholder’s confidence.

This paper recognizes several limitations like any other empirical study, particularly relating to choice of variables, period of study and collection of data from Kenyan insurers, an emerging economy. Thus, to validate the results, similar cross-country studies are recommended in other emerging economies. Also future studies may extend the time period. Further, future studies could extend the scope to determine optimal gender mix as well as broaden the studies to cover gender inclusivity among the top executives and embrace additional variables such as professional diversity, top management demographics (age, tenure and education level), ownership structures and other control variables among others.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Abou-El-Sood, H. (2019). Corporate governance and risk taking: The role of board gender diversity. Pacific Accounting Review, 31(1), 19–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/PAR-03-2017-0021

- Adams, R. B., & Ferreira, D. (2009). Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 94(2), 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.10.007

- Adusei, M., Akomea, S. Y., Poku, K., & McMillan, D. (2017). Board and management gender diversity and financial performance of microfinance institutions. Cogent Business & Management, 4(1), 1360030. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2017.1360030

- Ahmed, S., Sihvonen, J., & Vähämaa, S. (2019). CEO facial masculinity and bank risk-taking. Personality and Individual Differences, 138, 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.09.029

- Akbar, S., Kharabsheh, B., Poletti-Hughes, J., & Shah, S. Z. A. (2017). Board structure and corporate risk taking in the UK financial sector. International Review of Financial Analysis, 50, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2017.02.001

- Al‐Amri, K., Gattoufi, S., & Al‐Muharrami, S. (2012). Analyzing the technical efficiency of insurance companies in GCC. The Journal of Risk Finance, 13(4), 362–380. https://doi.org/10.1108/15265941211254471

- Alam, N. (2012). Efficiency and risk-taking in dual banking system: Evidence from emerging markets. International Review of Business Research Papers, 8(4), 94–111.

- Alhassan, A. L., & Biekpe, N. (2015). Efficiency, productivity and returns to scale economies in the non-life insurance market in South Africa. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance-Issues and Practice, 40(3), 493–515. https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2014.37

- Al-Jaifi, H. A., Al-Qadasi, A. A., & Al-Rassas, A. H. (2023). Board diversity effects on environmental performance and the moderating effect of board independence: Evidence from the Asia-Pacific region. Cogent Business & Management, 10(2), 2210349. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2210349

- Alves, S. (2023). Gender diversity on corporate boards and earnings management: Evidence for European Union listed firms. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2193138. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2193138

- Amin, A., Ur Rehman, R., Ali, R., & Mohd Said, R. (2022). Corporate governance and capital structure: Moderating effect of gender diversity. SAGE Open, 12(1), 21582440221082110. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221082110

- Ararat, M., & Yurtoglu, B. B. (2021). Female directors, board committees, and firm performance: Time-series evidence from Turkey. Emerging Markets Review, 48, 100768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2020.100768

- Berger, A. N., Kick, T., & Schaeck, K. (2014). Executive board composition and bank risk taking. Journal of Corporate Finance, 28, 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2013.11.006

- Bernile, G., Bhagwat, V., & Yonker, S. (2018). Board diversity, firm risk, and corporate policies. Journal of Financial Economics, 127(3), 588–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2017.12.009

- Bin Khidmat, W., Ayub Khan, M., & Ullah, H. (2020). The effect of board diversity on firm performance: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Indian Journal of Corporate Governance, 13(1), 9–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0974686220923793

- Boamah, N. A., Boakye Dankwa, A., & Opoku, E. (2021). Risk-taking behavior, competition, diversification and performance of frontier and emerging economy banks. Asian Journal of Economics and Banking, 6(1), 50–68. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJEB-04-2021-0047

- Bogdan, V., Popa, D. N., Beleneşi, M., & Jiang, Z.-Q. (2022). The complexity of interaction between executive board gender diversity and financial performance: A panel analysis approach based on random effects. Complexity, 2022, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9559342

- Borghans, L., Heckman, J. J., Golsteyn, B. H., & Meijers, H. (2009). Gender differences in risk aversion and ambiguity aversion. Journal of the European Economic Association, 7(2–3), 649–658. https://doi.org/10.1162/JEEA.2009.7.2-3.649

- Brady, D., Isaacs, K., Reeves, M., Burroway, R., & Reynolds, M. (2011). Sector, size, stability, and scandal: Explaining the presence of female executives in Fortune 500 firms. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 26(1), 84–105. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542411111109327

- Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Pavelin, S. (2007). Gender and ethnic diversity among UK corporate boards. Corporate Governance an International Review, 15(2), 393–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2007.00569.x

- Bruna, M. G., Dang, R., Scotto, M. J., & Ammari, A. (2019). Does board gender diversity affect firm risk-taking? Evidence from the French stock market. Journal of Management & Governance, 23(4), 915–938. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-019-09473-1

- Bsoul, R., Atwa, R., Odat, M., Haddad, L., & Shakhatreh, M. (2022). Do CEOs’ demographic characteristics affect firms’ risk-taking? Evidence from Jordan. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2152646. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2152646

- Byrnes, J. P., Miller, D. C., & Schafer, W. D. (1999). Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125(3), 367. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.3.367

- Chatjuthamard, P., Jiraporn, P., Lee, S. M., & Gherghina, S. C. (2021). Does board gender diversity weaken or strengthen executive risk-taking incentives? PloS One, 16(10), e0258163. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258163

- Claessens, S., & Yurtoglu, B. B. (2013). Corporate governance in emerging markets: A survey. Emerging Markets Review, 15, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2012.03.002

- Cummins, J. D., Tennyson, S., & Weiss, M. A. (1999). Consolidation and efficiency in the US life insurance industry. Journal of Banking & Finance, 23(2–4), 325–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-42669800089-2

- Danquah, M., Otoo, D. M., & Baah‐Nuakoh, A. (2018). Cost efficiency of insurance firms in Ghana. Managerial and Decision Economics, 39(2), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.2897

- Diacon, S. R., Starkey, K., & O’Brien, C. (2002). Size and efficiency in European long-term insurance companies: An international comparison. Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance: Issues and Practice, 27(3), 444–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0440.00184

- Dong, Y., Girardone, C., & Kuo, J. M. (2017). Governance, efficiency and risk taking in Chinese banking. The British Accounting Review, 49(2), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2016.08.001

- Dwaikat, N., Qubbaj, I. S., Queiri, A., & Seetharam, Y. (2021). Gender diversity on the board of directors and its impact on the Palestinian financial performance of the firm. Cogent Economics & Finance, 9(1), 1948659. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2021.1948659

- Dwyer, P. D., Gilkeson, J. H., & List, J. A. (2002). Gender differences in revealed risk taking: Evidence from mutual fund investors. Economics Letters, 76(2), 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-17650200045-9

- Elamer, A. A., AlHares, A., Ntim, C. G., & Benyazid, I. (2018). The corporate governance–risk-taking nexus: Evidence from insurance companies. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, 34(4), 493–509. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOES-07-2018-0103

- Eling, M., & Jia, R. (2019). Efficiency and profitability in the global insurance industry. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 57, 101190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2019.101190

- Elisa, M., & Guido, P. (2020). Does gender diversity matter for risk-taking? Evidence from Italian financial institutions. African Journal of Business Management, 14(10), 324–334. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM2020.9089

- Elsaid, E., & Ursel, N. D. (2011). CEO succession, gender and risk taking. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 26(7), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542411111175478

- Faccio, M., Marchica, M. T., & Mura, R. (2016). CEO gender, corporate risk-taking, and the efficiency of capital allocation. Journal of Corporate Finance, 39, 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2016.02.008

- Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. The Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 301–325. https://doi.org/10.1086/467037

- Fiordelisi, F., Marques-Ibanez, D., & Molyneux, P. (2011). Efficiency and risk in European banking. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(5), 1315–1326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2010.10.005

- Fraser-Moleketi, G. J., Mizrahi, S., & African Development Bank. (2015). Where are the women: Inclusive boardrooms in Africa’s top listed companies.

- Gao, Y., Kim, J. B., Tsang, D., & Wu, H. (2017). Go before the whistle blows: An empirical analysis of director turnover and financial fraud. Review of Accounting Studies, 22(1), 320–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-016-9381-z

- García, C. J., & Herrero, B. (2021). Female directors, capital structure, and financial distress. Journal of Business Research, 136, 592–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.07.061

- Gujarati, D. N., & Porter, D. C. (2008). Basic Econometrics (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

- Gulamhussen, M. A., & Santa, S. F. (2015). Female directors in bank boardrooms and their influence on performance and risk-taking. Global Finance Journal, 28, 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfj.2015.11.002

- Gyapong, E., Ahmed, A., Ntim, C. G., & Nadeem, M. (2019). Board gender diversity and dividend policy in Australian listed firms: The effect of ownership concentration. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-019-09672-2

- Hambrick, D. C., & Mason, P. A. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. The Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.2307/258434

- Harjoto, M. A., Laksmana, I., & Yang, Y. W. (2018). Board diversity and corporate investment oversight. Journal of Business Research, 90, 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.04.033

- Hillman, A. J., Withers, M. C., & Collins, B. J. (2009). Resource dependence theory: A review. Journal of Management, 35(6), 1404–1427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309343469

- Houston, J. F., Lin, C., Lin, P., & Ma, Y. (2010). Creditor rights, information sharing, and bank risk taking. Journal of Financial Economics, 96(3), 485–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2010.02.008

- Jaloudi, M., & Bakir, A. (2019). Market structure, efficiency, and performance of Jordan insurance market. International Journal of Business and Economics Research, 8(1), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijber.20190801.12

- Jamali, D., Safieddine, A., & Daouk, M. (2006). The glass ceiling: Some positive trends from the Lebanese banking sector. Women in Management Review, 21(8), 625–642. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420610712027

- Jizi, M. I., & Nehme, R. (2017). Board gender diversity and firms’ equity risk. Equality, Diversity & Inclusion: An International Journal, 36(7), 590–606. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-02-2017-0044

- Khatib, S. F., Abdullah, D. F., Elamer, A. A., & Abueid, R. (2021). Nudging toward diversity in the boardroom: A systematic literature review of board diversity of financial institutions. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(2), 985–1002. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2665

- Kirkpatrick, G. (2009, 1). The corporate governance lessons from the financial crisis. OECD Journal: Financial Market Trends, 2009, 61–87. https://doi.org/10.1787/fmt-v2009-art3-en

- Levin, I. P., Snyder, M. A., & Chapman, D. P. (1988). The interaction of experiential and situational factors and gender in a simulated risky decision-making task. The Journal of Psychology, 122(2), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1988.9712703

- Li, Y., & Zhang, X. Y. (2019). Impact of board gender composition on corporate debt maturity structures. European Financial Management, 25(5), 1286–1320. https://doi.org/10.1111/eufm.12214

- Maheshe, N. R. (2021). Gender Diversity and Performance of International Non-governmental Organizations in the Democratic Republic of Congo [ Doctoral dissertation]. University of Nairobi.

- Meles, A., & Starita, M. G. (2013). Does governance structure affect insurance risk-taking? In Financial Systems in Troubled Waters (pp. 82–98). Routledge.

- Mgammal, M. H. (2022). Appraisal study on board diversity: Review and agenda for future research. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2121241. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2121241

- Milliken, F. J., & Martins, L. L. (1996). Searching for common threads: Understanding the multiple effects of diversity in organizational groups. The Academy of Management Review, 21(2), 402–433. https://doi.org/10.2307/258667

- Mohsni, S., Otchere, I., & Shahriar, S. (2021). Board gender diversity, firm performance and risk-taking in developing countries: The moderating effect of culture. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 73, 101360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2021.101360

- Muhammad, H., Migliori, S., & Mohsni, S. (2022). Corporate governance and firm risk-taking: The moderating role of board gender diversity. Meditari Accountancy Research.

- Nguyen, T. H. H., Ntim, C. G., & Malagila, J. K. (2020). Women on corporate boards and corporate financial and non-financial performance: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. International Review of Financial Analysis, 71, 101554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2020.101554

- Ntim, C. G. (2015). Board diversity and organizational valuation: Unravelling the effects of ethnicity and gender. Journal of Management & Governance, 19(1), 167–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-013-9283-4

- Ofori-Sasu, D., Kuwornu, J., Dzeha, G. C., & Kusi, B. A. (2022). Risk behaviour and insurance efficiency: The role of ownership and regulations from an emerging economies. SN Business & Economics, 2(7), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-022-00254-x

- Palvia, A., Vähämaa, E., & Vähämaa, S. (2020). Female leadership and bank risk-taking: Evidence from the effects of real estate shocks on bank lending performance and default risk. Journal of Business Research, 117, 897–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.04.057

- Peltomäki, J., Sihvonen, J., Swidler, S., & Vähämaa, S. (2021). Age, gender, and risk‐taking: Evidence from the S&P 1500 executives and market‐based measures of firm risk. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 48(9–10), 1988–2014. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbfa.12528

- Perryman, A. A., Fernando, G. D., & Tripathy, A. (2016). Do gender differences persist? An examination of gender diversity on firm performance, risk, and executive compensation. Journal of Business Research, 69(2), 579–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.05.013

- Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. (1978). A resource dependence perspective. In Intercorporate relations. The structural analysis of business. Cambridge University Press.

- Ramadan, M. M., & Hassan, M. K. (2021). Board gender diversity, governance and Egyptian listed firms’ performance. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-02-2021-0057

- Roodman, D. (2009). How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. The Stata Journal, 9(1), 86–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0900900106

- Saeed, A., Mukarram, S. S., & Belghitar, Y. (2021). Read between the lines: Board gender diversity, family ownership, and risk‐taking in Indian high‐tech firms. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 26(1), 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.1784

- Safiullah, M., Akhter, T., Saona, P., & Azad, M. A. K. (2022). Gender diversity on corporate boards, firm performance, and risk-taking: New evidence from Spain. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 35, 100721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2022.100721

- Sanyaolu, W. A., Eniola, A. A., Zhaxat, K., Nursapina, K., Kuangaliyeva, T. K., & Odunayo, J. (2022). Board of directors’ gender diversity and intellectual capital efficiency: The role of international authorisation. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2122802. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2122802

- Sarhan, A. A., Ntim, C. G., & Al‐Najjar, B. (2019). Board diversity, corporate governance, corporate performance, and executive pay. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 24(2), 761–786. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.1690

- Sbai, H., & Ed Dafali, S. (2023). Gender diversity and risk-taking: Evidence from dual banking systems. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRA-07-2022-0248

- Shair, F., Sun, N., Shaorong, S., Atta, F., Hussain, M., & Gherghina, S. C. (2019). Impacts of risk and competition on the profitability of banks: Empirical evidence from Pakistan. PloS One, 14(11), e0224378. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224378

- Sila, V., Gonzalez, A., & Hagendorff, J. (2016). Women on board: Does boardroom gender diversity affect firm risk? Journal of Corporate Finance, 36, 26–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2015.10.003

- Tan, Y., Charles, V., Belimam, D., & Dastgir, S. (2021). Risk, competition, efficiency and its interrelationships: Evidence from the Chinese banking industry. Asian Review of Accounting, 29(4), 579–598. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARA-06-2020-0100

- Tyrowicz, J., Terjesen, S., & Mazurek, J. (2020). All on board? New evidence on board gender diversity from a large panel of European firms. European Management Journal, 38(4), 634–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2020.01.001

- Watson, J., & McNaughton, M. (2007). Gender differences in risk aversion and expected retirement benefits. Financial Analysts Journal, 63(4), 52–62. https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v63.n4.4749

- Wintoki, M. B., Linck, J. S., & Netter, J. M. (2012). Endogeneity and the dynamics of internal corporate governance. Journal of Financial Economics, 105(3), 581–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2012.03.005