?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study investigates the impact of excluding stock options for non-executive directors (NEDs) on the relationship between executive pay and firm performance. The research focuses on accounting measures and market performance. Using a sample of 220 non-financial firms, including 110 listed firms from the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) as the treatment group and 110 firms from alternative stock markets as the control group, the study employs the Difference-In-Difference (DID) regression analysis. The findings show that excluding stock options for NEDs leads to a significant increase in the value of executive performance compensation. However, this relationship lacks statistical significance for market-based performance. The study also reveals a significant positive influence of executive ownership on executive compensation. The results suggest the importance of alternative compensation structures and aligning executive interests with shareholder interests. The study recommends encouraging the exclusion of stock options for NEDs, exploring alternative compensation structures tied to accounting-based measures, conducting further research on market-based performance metrics, implementing executive ownership programs, and continuously monitoring and evaluating executive compensation practices. The findings validate their recommendations, which may be helpful for future decisions in that area. The results are also valuable for shareholders, as they vote on remuneration policies, including the different forms of incentives relating to NEDs.

1. Introduction

The substance of firms’ boards’ actions is questionable because observing their daily effect is challenging. According to Adams et al. (Citation2010), the firm’s Board of Directors (BODs) is more often held accountable for a firm’s poor outcome when the firm’s poor results are evident. Defining the proper steps for board members is unclear (Bindert, Citation2010). The desire to improve boards as corporate governance (CG) mechanisms to curtail agency conflicts in South Africa led to King IV’s enactment in 2017. CG comprises firms’ administration and control techniques (Fama & Jensen, Citation1983; Felix Eluyela et al., Citation2020; Kjærland et al., Citation2020; Orazalin et al., Citation2016). King IV builds on King III. South Africa’s King IV code is designed as a report incorporating a code for governance structures and business operations in the country. King IV comprises both principles and recommended practices to achieve governance outcomes. One special feature is of King IV is its application explanation of rules for all listed firms on the Johannesburg Stock Market which implies that one size fits all policy.

Globally, corporate governance is a predominant concern on firms’ boards. Stakeholders such as legislators, regulators, academics, and practitioners are inclined to uphold CG principles and policies (Agyei-Boapeah et al., Citation2019). Therefore, CG in the firm serves as a vital mechanism for profitability. Theoretically, complying with recommendations of corporate governance codes is fundamentally regarded as a good signal by companies toward markets and firm performance. This indicates that, because a company follows the best practices of corporate governance, investors will be assured that managers will act in the best interests of shareholders. This means that the potential and existing investors will bid high prices for companies with a good corporate governance system, because the investment in such companies will be profitable (La Porta, et al., Citation2002; Elmagrhi et al., Citation2020). Several internal and external factors can be utilized to minimize corporate agency conflicts, such as the framework of board directorship, financing debts, legal and regulatory tools, supervisory systems, capital markets, and product market competition (Fama & Jensen, Citation1983). With these CG principles and polices, firms still have a lot to do to guard and prevent agency problems occurrence.

The financial crisis of 2008, increasing stakeholder activism, financial and trade liberalization, and capital mobilization reflect the existence of agency conflicts around the globe. The failure of several prestigious enterprises in emergent nations and developed economies over the past few years illustrates the prevalence of agency conflicts. The rising rate of failing enterprises is necessary to address and mitigation measures identified (Artiga González & Calluzzo, Citation2020; Peng, Citation2004; Zang, Citation2012). Examples include Kmart, Bear Stearns, Dynegy, and Theranos in the United States; Polly Peck, Anglo Irish Bank, and Royal Bank of Scotland in the United Kingdom; Wirecard, Hypo Real Estate, Arcandor in Germany; ABN-Amro in the Netherlands; and Dick Smith in Australia. One of the most mentioned reasons for these business crises is the directors’ lack of oversight or failure to prohibit management’s harmful activities. Eron and Worldcom are two classic examples of failed companies despite the BOD composition mostly of NEDs.

The Board of Directors (BOD) comprises both non-executive directors (NEDs) and executive directors. According to the King IV corporate governance guidelines, at least two executive directors, usually the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and Chief Financial Officer (CFO), should provide operational information to the BOD. Non-Executive Directors (NEDs) provide an independent oversight function and act in the company’s and its stakeholders’ best interests, including shareholders. Due to their independence from the firm and its management, NEDs are considered well-suited for establishing and overseeing executive compensation programs (Platt & Platt, Citation2012). Numerous scholars have questioned the board of directors’ effectiveness in developing an adequate executive compensation program.

However, Chhaochharia and Grinstein (Citation2009) study suggests that the BOD does not significantly influence executive or CEO compensation programs, which contradicts the managerial power hypothesis. This hypothesis posits that executives can control pay and extract rents through inefficient governance structures and excessive compensation program (Bebchuk et al., Citation2010; Elmagrhi & Ntim, Citation2022). Fama and Jensen (Citation1983) have argued that the BOD can effectively devise an appropriate executive compensation program. According to the optimal contracting theory, the BOD has a critical role in creating an efficient executive compensation program to curtail agency conflicts and maximize shareholder value (Core & Guay, Citation1999; Dorff, Citation2004; Tang, Citation2014). The BOD is responsible for minimizing costs, aligning executives’ interests with shareholders, and retaining talented executives when setting up executive compensation programs (Tang, Citation2014). Thus, the effectiveness of the BOD in designing executive compensation programs has been supported by various scholars. Chhaochharia and Grinstein (Citation2009) opines, changes in executive compensation are linked to adjustments in board structure, indicating that the design of executive compensation is the responsibility of the BOD rather than the executives themselves. Studies by J. Graham et al. (Citation2011) support the optimal contracting hypothesis, which shows higher compensation for talented and performing executives, and by Morgan and Poulsen (Citation2001), which demonstrate a buoyant stock market reaction to plans that tie CEO compensation to performance.

These findings suggest two general views regarding the BOD’s role in setting executive compensation: the managerial power hypothesis challenges the BODs’ influential role in developing executive compensation, while the optimal contracting theory acknowledges their role in designing it. Empirical evidence supports both views, with Bussin’s (Citation2015) study indicating that the BODs’ role in setting executive compensation programs in South Africa remains unresolved. The optimal contracting theory prevails during periods of high economic performance, while the managerial power theory takes center stage during the low economic performance. Bussin (Citation2015) found evidence to support the managerial power hypothesis, noting a weakened association between executive incentives and performance, with a shift away from performance-related executive contracts.

One indorsed mechanism of CG is NEDs. They are in particular preferred agents for monitoring and reducing agency conflicts (Platt & Platt, Citation2012). NEDs are considered independent (Alves, Citation2014; Zhou et al., Citation2017). The impartial and objective nature of NEDs makes them effective in addressing agency issues. At the same time, executive directors, who are insiders and part of the management team, have little incentive to actively monitor and reduce such issues (Sengupta & Zhang, Citation2015). Unfortunately, assessments enumerated by Fama and Jensen (Citation1983), Platt and Platt (Citation2012), Lin and Lin (Citation2014), and Zhou et al. (Citation2017) demonstrate that NEDs do not constantly act in utmost good faith or align with the objectives of the shareholders. As a result, another agency conflict arises called secondary agency conflicts.

Secondary agency conflicts are caused by the divergence of interest, interest gaps, or misalignment of shareholders’ targets and aspirations and NEDs’ goals (Perry, Citation2000). These conflicts arise when NEDs tasked with a variety of responsibilities, including monitoring management, representing shareholders’ interests, and resolving management and shareholders’ agency issues, neglect to fulfill their obligations and conspire with the firm’s management to undertake projects that benefit themselves and managers to the disadvantage of the shareholders (Andreas et al., Citation2011). The prevalence of secondary agency conflicts is due to several factors: the lack of NEDs’ benefits, interest, and financial motivations to supervise and monitor management and safeguard the shareholder’s interest (Bebchuk & Fried, Citation2006). Secondary agency conflicts are fundamentally due to a break in NEDs’ monitoring.

The composition of independent directors and their compensation are needed in improving board independence. The two aspects are two crucial techniques for addressing secondary agency-related conflicts. These two techniques address the core causes of NEDs’ loss of motivation and objectivity regarding monitoring management (Abdullah & Nasir, Citation2004; Alves, Citation2014; Jensen & Murphy, Citation1990). The composition of NEDs and NEDs’ compensation are two processes emanating from the authority of shareholders. Even though King IV’s recommendations include both the composition and compensation of NEDs, the study focused more on NEDs’ compensation. The effectiveness of NEDs’ compensation in reducing secondary agency conflicts is an ardently debated topic. Previous research has provided two opposing arguments, both supported by empirical evidence in response to it.

The first is the rent extraction viewpoint. The rent extraction viewpoint is supported by facts and other countries’ CG regulations. The Australian Stock Exchange (ASX) recommends against incentive pay for NEDs in its Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations (Conway, Citation2012). However, ASX does not prohibit the use of NED incentives. ASX acknowledges that there is no one-size-fits-all governance structure and it adopts the if not, why not approach. A firm can use NED incentive pay where appropriate; ASX only requires the firm to explain why it chooses not to follow the recommendation. The Financial Reporting Council (FRC) adopts a similar recommendation against NED incentive pay and the if not, why not approach in the UK (Council & Britain, Citation2012). This viewpoint perceives the exclusion of NEDs’ equity-based pay as an effective method to improve the work of NEDs. Orazalin et al. (Citation2016) claim a strong link between NEDs and stock volatility. The exclusion of NEDs’ equity compensation enhances their independence and capacity to make objective and independent decisions when their actions do not directly influence their wealth. As a result, their neutrality and power to make independent and objective decisions will not be impaired.

Certo et al. (Citation2001) indicates that utilizing the same incentives criteria for performance, for instance, stock options payment for NEDs and management, establishes mutual benefit between two agents (NEDs and management). These two agents who work interdependently may have an information lead over the shareholders. In the short run, this will create a disincentive for NEDs to concentrate on the business of maximizing the shareholders’ wealth. They engage in unethical acts and activities which advance the price of stocks and the stock volatility to boost their benefits in the short run rather than the increasing shareholder’s capital in the long run. Additionally, some researches have links between the equity compensation of NEDs and elements that reveal indications of weak levels of monitoring and supervision and misalignment of interests between the management and NEDs as one group and the shareholder on the opposite decision. The factors include false financial reporting including earnings management intending to increase the stock price to its advantage (Liao et al., Citation2017); financial statements falsification and misstatements due to fraud and errors (Dalnial et al., Citation2014) reviewing stock options date, legal actions, and fraud (Crutchley & Minnick, Citation2012); an inconsistent association between management and NEDs (Lin & Lin, Citation2014;).

While the above studies on CG principles proof and empirical confirmations support the exclusion of equity-based pay as a valuable and efficient tool in curtailing agency conflicts, the incentive hypothesis envisages NEDs’ compensation with equity as a better way of dealing with agency related problems (Fich & Shivdasani, Citation2006; Seamer & Melia, Citation2015). Therefore, compulsory excluding stock options is a disincentive for NEDs. According to the research cited, NEDs who receive equity-based payment are offered a financial interest in the firm’s performance, prompting the NEDs to act as shareholders. Again, it aligns their objectives and aspirations to those of the shareholders, incentivizing NEDs to monitor management vigilance and provide adequate supervision (Goh & Gupta, Citation2016). Kroll et al. (Citation2008) supported and outlined that over the last two decades, there has been a steady increase in the usage of equity remuneration to reward NEDs in countries such as the United States of America (USA). This expansion is sponsored by prominent and powerful USA-based professional companies that promote and back the idea of share grants and stock options incentives to help grow small and medium businesses. The National Association of Corporate Directors, the California Public Employees Retirement System, and the Blue-Ribbon Report on Director Compensation are a few influential companies backing the concept. Prior studies have also found a relation between equity-based compensation for NEDs incentives and enhanced monitoring. The proxies for improved monitoring include increased firm performance (Adithipyangkul & Leung, Citation2018; Felix Eluyela et al., Citation2020; Nyantakyi et al., Citation2023); preferences for risk (Lipton & Lorsch, Citation1992); executive reward and executive turnover after a poor performance (Hoitash & Mkrtchyan, (Citation2022) quality of reporting (Bierstaker, Citation2012) hostile take-overs and acquisitions (Lahlou & Navatte, Citation2017); and bridging information asymmetry (Jermias and Yigit, Citation2013).

Notwithstanding the debate enumerated above, there is insufficiency of literature in emerging countries including South Africa. In particular is the study of NED’s compensation after the enactment of the King IV CG principles which made it compulsory requirement for firms listed in the Johannesburg Stock Market. Also, the research investigates the deviation of South Africa CGs from the American blue print and from the Anglo-Saxon countries—thus to compulsory halt the payment of equity incentives to NEDs for effective monitoring. The study also differentiates investigation from prior studies by using the JSC and alternate stock markets in South Africa.

The study’s contribution firstly, lies in its focus on secondary agency conflicts (NEDs monitoring) in the South African context that is an important board independence factor but has been largely neglected by previous research. Some studies have identified the urgency to study secondary agency conflicts and the impact of equity incentives on monitoring (Deutsch & Valente, Citation2013; Perry, Citation2000). Secondly, the uniqueness of South Africa provides opportunities and fresh evidence to study in-depth on this topic. The South African’s King IV principles which makes the country, the foremost in Africa to strictly exclude stock options for NEDs. It has a more stringent definition of board independence than other countries. By emphasizing this aspect of corporate governance, the study adds to the growing literature on the topic. thirdly, NEDs’ compensation effectiveness in executive remuneration design is uncertain because prior studies have not investigated in-depth, especially in Africa. Nonetheless, executive compensation is a prominent agency issues making business headlines in South Africa and around the world, making them ideal for research in this study. Lastly, the compulsory exclusion of NEDs’ stock options creates an opportunity for a natural experiment on South African businesses. The natural experiment can address endogeneity, deduce causality, and confirm the different views on corporate governance reforms and monitoring power of NEDs’. Hence the need to investigate whether excluding stock stock options for NEDs enhances the tie between executive pay and firm performance based on accounting and market measures. The remainder of the study is as follows. Section 2 discusses the literature and hypothesis development. Section 3 examines the data and methodology. Section 4 starts by providing descriptive statistics of the research data, followed by empirical studies. The paper is concluded with recommendations and areas of further research.

2. Theoretical review

NEDs by their monitoring authority ensures firms’ efficient executive compensation program. Setting executive compensation policies is an essential component of the success of an organization. It shapes how top executives behave and helps regulate the types of executives an organization attracts (M. C. Jensen & Murphy, Citation1990). Chen et al. (Citation2021) categorized executive compensation into four components, namely, fixed versus variable pay, short-term versus long-term pay, cash versus equity, and individual versus group pay. According to Guay et al. (Citation2001) and Frydman and Jenter (Citation2010), there is no clear standard for all industries for fixing an efficient executive incentive. Therefore, a compensation program tailored to maximize shareholder value in a particular situation may need to be revised for some periods and cases to mitigate the agency challenges.

According to M. C. Jensen and Murphy (Citation1990), aligning executive compensation with performance is crucial in reducing the divide between management and shareholders. It also incentivizes executives to act in the best interest of shareholders and make decisions accordingly. These ideas are consistent with the optimal contracting theory, which suggests that well-designed executive compensation programs can enhance shareholder value while mitigating agency problems (Core & Guay, Citation1999; Dorff, Citation2004; Lokko et al., Citation2021). Murphy (Citation2013) attributed the rise in pay-performance sensitivity in the United States to the optimal contracting theory, noting that compensation programs were suboptimal before the 1990s but have improved since then.

If offered a performance-linked compensation program, executives are incentivized to act upon projects that align with shareholders’ interests. Maher and Andersson (Citation2000) consider agency theory focusing on efficient executives and propose compensation is linked to aspects of performance over which managers have some control. Performance areas that executives have control over are indicated as return on assets, equity, sales, and investment (Eisdorfer et al., Citation2013). Otherwise, executives would not have the urgency to make significant efforts and projections to increase firm performance since executives know they will be earned their salary irrespective of the firm’s performance. Shareholders may not be willing to pay managers for events beyond their control, e.g., a better firm performance due to a general boom in the stock market. In similar cases, owners will not penalize (fire) managers due to adverse outcomes that are not the manager’s fault, e.g., poor performance due to a recession. However, when other firms in the industry are performing well, it is tough for the management team to claim that the firm has achieved poorly due to general market conditions. Instead, executive directors’ compensation programs should correlate compensation to rises in relative performance.

To determine optimal compensation, one possible proxy is the sensitivity of total performance pay, specifically cash performance bonuses. The study focuses on the total executive’s performance pay and uses the executive directors’ performance. The executive directors’ power is significant and an effective CG mechanism (Baker, Citation2019; Feng et al., Citation2007; J. R. Graham et al., Citation2017; Lawal, Citation2011; Sheikh, Citation2019). Previous studies have pointed out that using stock incentives as a component of executive compensation can have negative implications. For instance, if it does not align with firm performance, excessive equity incentives can lead to unwarranted compensation and encourage earnings manipulation (Armstrong et al., Citation2013; C. Laux & Laux, Citation2009). Maher and Andersson (Citation2000) have also demonstrated a relatively weak link between executive performance and compensation programs that exclude stock incentives. Consequently, executives’ equity compensation changes can indicate either poor or effective monitoring by NEDs. Studies examining equity compensation view NEDs and executive directors as interchangeable. Therefore, performance cash bonuses can be a suitable measure for evaluating the impact of excluding stock options compensation for NEDs on secondary agency conflicts.

The antecedent enquiry for company’s performance which appeals for enormous study gives different views on the use of different variables to assess the company’s performance. A company’s decisions, actions, activities and its results may be a measure of its performance. There are various performance evaluation and accepted standards. Various criteria have been used to evaluate and measure business units’ performance in accounting studies and researches that categorize performance into of market-based criteria, accounting data-based criteria and economic models. Accounting profit is the most traditional performance evaluation criteria, which is of utmost importance for investors, shareholders, managers, creditors and securities analysts. Accounting profit is calculated by accrual basis and many scholars believe that it is one of the most important measures of performance. By comparison, although market-based criteria are more objective, but at the same time, they are affected by a large number of factors uncontrollable by management, affected (Gani and Jermias, Citation2006). With the advent of theories in the field of economic benefit or residual income, models were proposed to calculate the economic benefit (Stewart, Citation1991). In these models, net operating profit after tax deduction and cost of capital is defined as economic profit or residual income. In economic models, company’s value is a function of profitability, existing priorities, potential investment and difference of the rate of return and cost of capital (Bausch et al., Citation2009). In this study, the accounting measures and markets measurements were utilized following similar studies by Boakye et al. (Citation2020).

3. Empirical review

The managerial power theory casts doubt on the relevance and effectiveness of the BODs in the setting of inefficient compensation. The fact that the studies reviewed indicated different opinions and empirical proof on the role of BODs’ decisions and actions means an unsolved matter demands in-depth investigation. Prior literature on the effect of compulsory excluding stock options compensation for NEDs on setting an efficient executive compensation is uncommon. Most literature on board structure and executive pay has focused on various board characteristics, including board size, independence, and executive pay levels. However, only a few studies, such as Bebchuk et al. (Citation2010), Brick et al. (Citation2006), Byard and Li (Citation2004), and Minnick and Zhao (Citation2009), have investigated the impact of equity-based compensation on the board and they have shown that it can hinder monitoring and lead to secondary agency problems. However, few studies have examined the relationship between non-executive directors’ monitoring and equity-based compensation. Majoni (Citation2019) is the only study with no significant relationship between the two.

The scholars observed that the evaluations are still needed to investigate the effect of the mandatory elimination of stock option incentives on the structure of executive compensation and the sensitivity of pay-for-performance. Such exclusions may lead to different levels of risk aversion among NEDs and impact their independence and neutrality. Moreover, the theoretical conclusions regarding the impact of stock options incentives need to be made more apparent when they are excluded on a mandatory basis. One of the reasons for the controversy surrounding stock options incentives could be their tendency to induce relatively high risk-taking behavior and a short-term focus. This may be why King IV targeted them for exclusion, as listed firms on the JSE are now required to exclude payment of stock options to NEDs, making it the third form of compensation to be excluded.

Empirical evidence shows that NEDs’ compensation can influence executive compensation. Brick et al. (Citation2006) found a positive relationship between excessive compensation for NEDs and executives not linked to performance, suggesting collaboration. This negatively impacts firm performance. Bebchuk et al. (Citation2010) found that directors were more likely to receive “lucky” stock options when executives also did. Byard and Li (Citation2004) notes that executives benefit from timing executive stock options when board members receive significant stock option compensation. Minnick and Zhao (Citation2009) found that directors with higher stock option incentives were more receptive to backdating. However, Majoni (Citation2019) found that removing stock option incentives did not significantly impact NEDs’ monitoring.

This study evaluates opposing theoretical arguments and existing empirical evidence to examine the effectiveness of the mandatory exclusion of stock options compensation in addressing secondary agency conflicts. While theoretical arguments on the impact of equity-based compensation on various monitoring aspects are conflicting, empirical evidence on executive incentives supports the rent extraction view, as demonstrated by previous studies (Bebchuk et al., Citation2010; Brick et al., Citation2006; Byard & Li, Citation2004; Majoni, Citation2019; Minnick & Zhao, Citation2009). The rent extraction view posits that equity-based compensation weakens the monitoring of executive incentives. Previous research has also indicated that providing stock options incentives for NEDs either worsens secondary agency conflicts or has no significant effect on executive pay-performance sensitivity. Therefore, the mandatory exclusion of stock options incentives by King IV is expected to enhance executive compensation monitoring substantially. By eliminating a barrier to effective monitoring, the compulsory removal of stock options for NEDs can mitigate secondary agency issues. In light of these arguments, the sought to investigate whether during the Post-King IV, excluding stock options for NEDs, will enhance the tie between executive pay and firm performance based on accounting and market measures in South Africa.

4. Research design

4.1. Data composition

The study’s sample period was from 2015 to 2019, following Chalevas’ approach of using two years before and after implementing a law. The year 2015 represented the second year before King IV’s implementation and the fifth year after King III’s implementation. The sample period ended in 2019 to avoid contamination from the COVID-19 pandemic’s effects on financial reporting. Initially, the study considered 325 companies for the treatment group (CECI, Citation2021). Firms from the financial sector were excluded to avoid industry bias, given the regulatory and governance differences between regulated and non-regulated industries (Deutsch & Valente, Citation2013). We manually collected individual compensation information from the integrated annual financial reports or the remuneration reports as the first stage. Most of these reports were available on the firms’ websites, but africamarkets.com was used for inaccessible websites. We examined all annual reports from 2015 to 2019 for each company and documented compensation details before and after the implementation of King IV.

The study focused on non-financial firms on the JSE that offered stock options incentives to NEDs before implementing King IV or had NEDs with balances of outstanding stock options before 2017. A total of 110 firms were identified as the treatment sample, and the researcher matched them with control groups using the DID methodology, resulting in a final sample of 110 firms. The firms in the sample were labeled as “treatment companies” and had data available for both pre-King IV and post-King IV periods. Table in the study summarizes the number of companies at each stage of the sample construction process.

Table 1. Summary of treatment and control sample

The selection was based on industry or size, ensuring the control firms were as similar as possible to the treatment firms. To be eligible, control firms had to have adopted a stock options policy for NEDs throughout the sample period and have unexpired and unexercised stock options before and after implementing King IV’s principles.

4.2. Variables definition

Table presents the variables measurement to explore how exclusion of stock options incentives for NEDs, as mandated by King IV, impacts executive pay and performance.

Table 2. Variable measurement

4.2.1. Dependent variable

The dependent variable in this study, Execomp, is represented by the logarithm of total cash performance bonus compensation measured annually.

4.2.2. Independent variables

This study employs the NEDcomDum dummy variable, which takes a value of one for treatment companies that are required to exclude stock options. In contrast, the variable takes a value of zero for control companies that are not subject to any restrictions in using NEDs’ stock option compensation during the analyzed period. The variable K4 is used as a dummy variable that takes a value of one for observations in the post-King IV period and zero for observations in the pre-King IV period, facilitating a comparison of executive compensation before and after the implementation of King IV.

This study utilizes both market-based and accounting measures to assess firm performance. Market-based performance is proxied by Tobin’s Q, which is calculated as the market value of equity and the book value of total debt divided by the book value of assets, following the approach used by Majoni (Citation2019) and KIng et al. (Citation2021). Accounting performance is measured by the return on assets (ROA) used by Gao and Li (Citation2015). The FP variable’s coefficient indicates CEO pay’s sensitivity to performance over the entire sample period. The study utilizes the NEDcomDum*K4 interaction term to assess executive compensation differences between treatment and control groups in the post-King IV eras. This term enables the examination of disparities in executive compensation practices between the two types of firms. The NEDcomDum*FP interaction term gauges the executive pay sensitivity to performance for treatment companies versus control companies. The variable of particular interest in this equation is NEDcomDumK4*FP, which represents the interaction between non-executive directors’ compensation, firm performance change, and the post-King IV period. This variable evaluates how executive pay sensitivity to performance altered for treatment firms during the post-King IV era relative to control firms.

4.2.3. Control variables

This study further examines several control variables to understand the relationship between executive compensation and various factors, including firm size (Fsize) (Bereskin & Cicero, Citation2013; Firth et al., Citation2006; Gao & Li, Citation2015), leverage (Leverage) (Brick et al., Citation2006; Cao et al., Citation2011), firm performance (ROA) (Firth et al., Citation2006; Gao & Li, Citation2015), executive ownership (EOwnDum) (Chen et al., Citation2014; Gao & Li, Citation2015; Guay et al., Citation2001), board independence (Indp) (V. Laux & Mittendorf, Citation2011; Ryan & Wiggins, Citation2004), board size (Bsize), directors’ multiple positions (Bbusy) (Daniliuc et al., Citation2021; Fich & Shivdasani, Citation2006; Hauser, Citation2018), institutional investors (Instin) (Bereskin & Cicero, Citation2013; Hartzell & Starks, Citation2003), CEO tenure (CEOt) (Ali & Zhang, Citation2015; Allgood & Farrell, Citation2000), executive age (Eage) (Conyon & He, Citation2011; Fung & Pecha, Citation2019), and firm’s growth opportunities (Tq) (Conyon & He, Citation2016; Hartzell & Starks, Citation2003; Harvey & Shrieves, Citation2001). Controlling for these variables enables a comprehensive analysis of the relationship between executive compensation and other factors, informing the design of effective compensation policies aligned with strategic objectives and market conditions.

4.3. Model specification

The study uses the difference-in-difference method (DID) to answer research questions in a natural experiment context. The study utilized a difference-in-difference analysis by creating two sample groups: the treatment group of 110 JSE-listed companies affected by King IV reforms, including a mandatory exclusion of stock options compensation for non-executive directors (NEDs), and the control group of unlisted firms on the JSE that were not subject to the same mandatory exclusion. The control group was matched to the treatment firms on the JSE to create a comparison group. To analyze the effect of the King IV reforms on the treatment group as compared to the control group, the researchers created dummy indicator variables to represent the sample groups and observations in the pre-King IV and post-King IV periods. These variables were then used to interact in the difference-in-difference regression.

The DID approach is used to compare the impact of a treatment on a treatment group with that on a control group. This study applied the DID approach to compare pre-King IV and post-King IV observations of 110 JSE-listed companies in the treatment group affected by the King IV regulatory reforms with those of unlisted firms on the JSE not subject to the reforms in the control group. The study followed a three-step approach to assess the impact of the King IV reforms on the treatment group in comparison to the control group. First, the difference between pre-King and post-King IV observations was calculated for the treatment group. Second, the difference between pre- King and post-King IV observations was also calculated for the control group. Finally, the two differences were compared to determine the impact of the treatment, while the control group served as a counterfactual benchmark.

The difference-in-difference regression analysis is employed since no univariate analysis is available for the executive cash pay-performance variable, which is measured from the primary analysis regression. EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) , based on the methodology of Gao and Li (Citation2015) and Majoni (Citation2019), is utilized to assess the impact of the compulsory exclusion of stock options incentives for NEDs on the executive cash pay-performance sensitivity during the post-King IV period. Using this approach, we can effectively investigate the relationship between executive pay and performance and determine whether the elimination of stock options incentives for NEDs has any bearing on this crucial aspect of corporate governance. The following equation guided the study:

The regression model as seen in Equationequation 1(1)

(1) holds the year and industry fixed effects (represented by μ) constant, while the other variables are discussed in the following sections. To avoid the problem of collinearity and to overfit in the regression model, firm fixed effects were not included in the analysis since the non-interacted variables for K4 and NEDcomDum have already been accounted for, as noted by Low (Citation2009). This approach ensures that estimating the coefficients for the interaction term in the difference-in-difference regression is not biased by firm-specific unobserved heterogeneity. By controlling for the main effects of K4 and NEDcomDum and allowing for their interaction, the analysis provides a more robust assessment of the impact of the King IV reforms on executive compensation. The research study utilized the Generalized Moment of Methods (see Equationequation 2

(2)

(2) ) to analyze the panel data, following the methodology outlined in the study conducted by Sarpong et al. (Citation2023) using GMM.

5. Empirical results and discussions

This empirical analysis is divided into three main sections. The first section presents descriptive statistics, a correlation matrix, and the results of the research questions and hypotheses tested in the first analysis, including the parallel trends assumption. The second section investigates the impact of excluding stock options compensation for NEDs on executive performance compensation. The section also includes a table comparing descriptive mean statistics of treatment and control firms.

5.1. Pre-diagnosis

To ensure the robustness of the difference-in-differences (DID) estimates, several diagnostic tests such as parallel trends assumption and covariate balance was conducted. These tests helped assess the validity of the underlying assumptions and the reliability of the estimated treatment effect. Table displays the findings that indicate treatment firms have a higher average total executive performance compensation of R4.31 million per annum compared to control firms, which have an average of R3.92 million per annum. The difference in means between the treatment and control groups is statistically significant at the 5% level. Additionally, the mean for CEO performance compensation is higher in treatment firms than in control firms, with a statistically significant difference in means.

Table 3. Summary of descriptive statistics

The study also presents the mean figures for executive ages, corporate governance variables, and firm characteristics. The mean for executive ages is the same for treatment and control companies. The mean figure for executive ownership is higher in control companies than in treatment firms, with a statistically significant difference. Treatment firms have a larger mean board size than control companies, with a statistically significant difference at the 5% level. The mean for the proportion of board independence is slightly higher in control companies, with a statistically significant difference at the 1% level. The mean for CEO tenure is longer in control firms than in treatment firms. Finally, treatment companies have a higher level of institutional ownership, with a statistically significant difference.

The findings in Table indicate a need for better monitoring of executive performance in South African firms. Treatment firms have higher total executive performance compensation, CEO performance compensation, and real-activities manipulation than control firms. These differences are statistically significant, with the mean difference in total executive and CEO performance compensation at 1%. Additionally, the study reveals differences in corporate governance and firm characteristics between treatment and control firms. Treatment firms are larger and have higher leverage and growth opportunities than control firms, as indicated by higher Tobin’s Q. However, control firms have higher executive ownership and a longer CEO tenure. The proportion of board independence is slightly higher in control firms, while institutional ownership is higher in treatment firms.

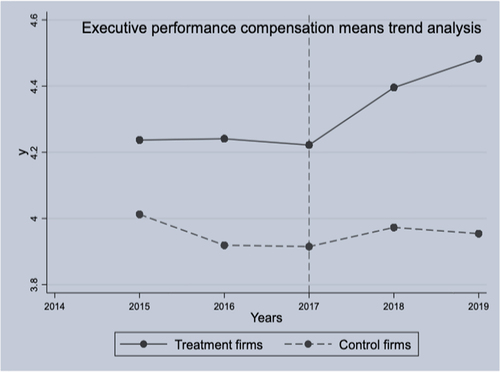

The validity of the DID tests in a natural experiment, as per Billett et al. (Citation2017), is also dependent on the parallel trends assumption. To test the parallel trends assumption for the pre-King IV periods, this study employs line graphs of the dependent variables for both control and treatment firms, like the approach used by Duchin et al. (Citation2010) and Billett et al. (Citation2017). The graphs presented in Figure shows that both groups’ dependent variable trends were similar before the treatment effects and diverged after the reform. This suggests that the parallel trends assumption is valid and that any observed differences in the dependent variables between the two groups after the reform are attributable to the effects of King IV. The parallel trends assumption holds for executive compensation since the treatment and control groups’ trends are similar, as depicted in Figure .

Table displays a correlation matrix for the independent variables used in this study. The results reveal no high correlations between the independent variables, with the highest correlation coefficient being 54%. These findings suggest that multicollinearity is not an issue in the analysis, consistent with Allison’s (Citation2012), Sappor et al. (Citation2023), Kir et al. (Citation2021), Cobbinah et al. (Citation2020) and Sarpong et al. (Citation2022) recommendations on the appropriateness of correlation matrix for a panel analysis.

Table 4. Correlation matrix

5.2. Principal analysis component

The study employed various econometric approaches to examine the impact of excluding stock options for non-executive directors (NEDs) on the relationship between executive pay and firm performance, utilizing accounting and market measures. In this investigation, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was employed as a powerful tool for dimensionality reduction and uncovering the underlying structure within the dataset.

PCA allows for the identification of patterns and correlations in a dataset that includes variables related to executive pay, firm performance, and other relevant factors. By transforming the original set of potentially correlated variables into a smaller set of uncorrelated variables called principal components, PCA provides insights into the complex connections among these variables. The results of the PCA analysis, as presented in Table , shed light on the interplay between the variables and provide a comprehensive understanding of how excluding stock options for NEDs may enhance the link between executive pay and firm performance.

Table 5. Principal component analysis

The results indicate that components one to five collectively accounted for 56.24% of the total variances observed. The eigenvectors associated with these components were employed to assess the extent to which the explanatory factors explained fluctuations in the response variable. The loadings of the variables under each component revealed valuable insights. Specifically, variables such as ROA, Tq, Eown, and Eage exhibited strong loadings under component 1, indicating a significant association with this component. However, it was observed that Tq did not display substantial loadings under components three to five. By utilizing PCA, this study advances our understanding of the relationship between executive pay, firm performance, and the impact of excluding stock options for NEDs.

5.3. Regression analysis

Pay-performance sensitivity remains a crucial aspect of executive pay programs, serving as a deterrent to agency problems and ensuring efficiency in compensation schemes (M. C. Jensen & Murphy, Citation1990; Murphy, Citation2013). Pay-performance is a motivating mechanism for executives (M. C. Jensen & Murphy, Citation1990). In this section, the study tested the impact of removing stock options compensation for NEDs on executive directors’ pay incentives. The study employed the difference-in-difference regression method to test this research question, as presented in Table . The study used two different measures of firm performance: returns on assets (ROA) and Tobin’s Q (Tq), and the variable of interest was NEDcomDumK4FP. This variable indicates how the sensitivity of executive pay to performance changed after the mandatory exclusion of stock options compensation for NEDs in the treatment firms compared to the control firms.

Table 6. NEDs compensation and executive performance pay sensitivity based on accounting measures

5.3.1. Relationship between executive pay and firm performance based upon accounting measures

Table employs a fixed-effects model with a difference-in-difference method to investigate the effect of mandatory exclusion of stock option compensation for NEDs on executive pay-performance sensitivity. The study examines this effect on accounting and market-based performance measures before and after implementing the King IV code. Models 1 and 2 use ROA to measure accounting performance. The variable of interest is NEDcomDum*K4*FP, which measures the change in executive pay-performance sensitivity for treatment companies after implementing the King IV code, compared to control companies. All other variables are defined in Table , and the table reports robust standard errors in parentheses.

Model 1 demonstrates that the coefficient for NEDcomDum*K4*FP is positive and statistically significant (coefficient = 0.0278, p < 0.10). This result highlights that the exclusion of stock options compensation for NEDs had a more pronounced impact on enhancing executive pay-performance sensitivity based on accounting performance (ROA) in the post-King IV period for treatment companies compared to control companies. Therefore, the compulsory exclusion has effectively strengthened the monitoring of executive compensation and ensured that executive pay better aligns with accounting performance.

Furthermore, Model 1 reveals that the NEDcomDum*FP coefficient is positive and significant (coefficient = 0.147, p < 0.01), suggesting that executive compensation is significantly more sensitive to performance (measured by ROA) for treatment companies than control companies throughout the full sample period. This finding underscores the inclination of treatment companies to link executive pay with their accounting performance to a greater extent than control companies. Overall, these results emphasize the importance of the compulsory exclusion of stock options compensation for NEDs in increasing the alignment between executive pay and firm performance and improving corporate governance practices.

Similarly, the study explores the same model during the pre-King IV period to ascertain the responsiveness of executive pay performance while excluding stock options compensation for NEDs was voluntary. The outcomes illustrate that the voluntary exclusion of stock options compensation for NEDs adversely affected the supervision of executive pay incentives. Specifically, the coefficient for NEDcomDum*FP is negative and statistically significant (coefficient=−0.0453, p < 0.01), implying a considerable amount of remuneration for low performance during the pre-King IV period. This finding underscores the significance of the mandatory exclusion of stock options compensation for NEDs in reinforcing the oversight of executive compensation and aligning executive pay with the firm’s performance. The fact that firms could apply or explain why they did not exclude stock options incentives for NEDs indicates that firms were not strictly complying with the principle, leading to impaired monitoring by NEDs. This option allowed management to exercise discretion in choosing the principles in the code they deemed fit for the firm. The use of multiple directorships on boards, advocated by the King’s committee, may have contributed to busy NEDs relying on consuming management information that was not factual, leading to incorrect decisions.

Moreover, the comparison of the standard error (SE) for NEDcomDum*K4*FP during the post-King IV period (SE = 1.049) and the pre-King IV period (SE = 2.081) indicates that the spread of standard deviations was wider in the pre-King IV period. This observation highlights the increased consistency and accuracy in the coefficient measurement during the post-King IV period, further underscoring the effectiveness of the mandatory exclusion of stock options compensation for NEDs in enhancing the alignment between executive pay and firm performance. This demonstrates that the sample mean in the pre-King IV period varies more than in the post-King IV period, confirming the higher significance levels of the coefficient as indicated above.

Table findings suggest that the coefficient for NEDcomDum*K4*FP indicates a more significant increase in executive pay-performance sensitivity in treatment companies compared to control companies following the mandatory exclusion of stock options compensation during the post-King IV period. These results underscore the crucial role of the compulsory exclusion of stock options compensation for NEDs in improving corporate governance practices and aligning executive pay with firm performance. In contrast, the voluntary exclusion of stock options compensation during the pre-King IV period led to negative executive pay-performance sensitivity, indicating that high compensation was given for poor performance. The voluntary exclusion of stock options compensation weakened monitoring by NEDs, which resulted in the need for compulsory exclusion to remove the impediment to effective monitoring. Therefore, the findings suggest that the King IV code’s compulsory exclusion of stock options compensation for NEDs improved monitoring and increased executive pay-performance sensitivity, indicating a positive impact on corporate governance.

The study’s results support the fact that that there was a significant increase in the sensitivity of executive pay to performance after excluding stock options compensation for NEDs. This finding supports the idea that stock options can create conflicts of interest for NEDs, making it easier for executives to manipulate the system and receive excessive pay unrelated to company performance. The study highlights the importance of re-evaluating stock options compensation for NEDs in corporate governance practices to ensure that executive pay is aligned with performance.

Prior research has not assessed the impact of obligatory exclusion of stock options compensation for NEDs on executive pay-performance sensitivity. However, Majoni (Citation2019) conducted a similar study that scrutinized the effect of voluntary inclusion of NEDs stock options and pay-performance sensitivity (unlike the present research that evaluated compulsory exclusion of stock options) and established evidence that supported the private benefit hypothesis, corroborating this study’s findings. However, Majoni (Citation2019) concentrated on incentives for CEOs specifically. Similarly, Minnick and Zhao (Citation2009) found that NEDs were more receptive to option backdating if they received stock options because they benefited from it. Bebchuk et al. (Citation2010) and Byard and Li (Citation2004) established evidence regarding stock options’ opportunistic timing and backdating when directors receive stock options. Other studies used alternative measures to executive pay-performance such as financial reporting, lawsuits, and proxies for their analysis to validate the rent extraction view (Campbell et al., Citation2011; Kim et al., Citation2019; Liao et al., Citation2017; Rose et al., Citation2013). Based on empirical studies that support the present research findings, it can be concluded that the obligatory exclusion of stock options compensation for NEDs enhances monitoring.

Regarding the relationship between executive performance compensation and performance measures, the study found a positive but non-significant connection with accounting-based performance (ROA). The results were consistent with prior research by Majoni (Citation2019).

The study’s findings suggest a positive but non-significant relationship between firm size and executive performance compensation, contradicting earlier research. The analysis revealed that leverage was not associated with executive performance compensation, consistent with previous studies. The study also found that executive ownership significantly influenced executive compensation, supporting both the incentive-alignment hypothesis and the entrenchment theory.

The study showed a negative but non-significant relationship between executive age and executive performance compensation, which contrasts with previous research. Board size and board independence did not have a significant relationship with executive compensation, aligning with the findings of Majoni (Citation2019). However, the study found a positive association between a firm’s growth opportunities and executive compensation, consistent with earlier research.

The study observed a positive but not statistically significant correlation between institutional ownership and executive performance compensation, contradicting prior research. Additionally, busy directors had no significant association with executive performance compensation, inconsistent with previous research by Hauser (Citation2018) and Daniliuc et al. (Citation2021). Hence, after introducing King IV regulations, the study provides insights into the factors influencing executive performance compensation in South African firms. While some findings were consistent with prior research, others contradicted previous studies. The results suggest that various factors influence executive performance compensation, including firm performance, ownership structure, and growth opportunities.

5.4. Additional analysis

The study employed a variety of methodologies to enhance the credibility of its findings. This included incorporating diverse independent variables, such as market-based executive compensation performance measures. Additionally, the study utilized different econometric models, including the Generalized Method of Moment, to analyze the data. Moreover, the study examined both financial and non-financial firms separately to investigate whether excluding stock options for NEDs would strengthen the relationship between executive pay and firm performance as illustrated below.

5.4.1. Relationship between executive pay and firm performance based upon market performance

For robust check the study replaced ROA with Tobin’s q as a proxy for market-based performance instead of accounting measure. Table analyzes the relationship between executive pay and market-based performance measures, specifically Tobin’s q, to examine the effects of the compulsory exclusion of stock options compensation for NEDs. Model 1 of Table shows a positive but statistically insignificant coefficient for NEDcomDum*K4*FP, with a coefficient of 0.180. This finding suggests that excluding stock options compensation for NEDs did not significantly affect executive pay-performance sensitivity in the post-King IV period for treatment companies compared to control companies, regarding Tobin’s q measure. Therefore, it can be inferred that the exclusion of stock options compensation for NEDs did not alter the ability of NEDs to monitor executive compensation, and their independence and objectivity remained unaffected.

Table 7. NEDs compensation and executive performance pay sensitivity based on market measures

If the stock options incentives had impacted the independence and objectivity of NEDs, their mandatory exclusion would have removed a hurdle to effective monitoring, resulting in a substantial increase in executive pay-performance sensitivity for treatment companies compared to control companies. Conversely, if the stock options incentives had improved monitoring, their compulsory exclusion would have weakened monitoring, resulting in a significant decrease in executive pay-performance sensitivity. Nevertheless, Table indicates that there was no significant change in pay-performance sensitivity, indicating that the exclusion of stock options compensation for NEDs did not affect NEDs’ ability to monitor executive compensation.

Based on the results presented in Table , the second part of the research question was not supported. The research question had anticipated that there would be a significant difference in executive pay sensitivity to market-based performance measures between treatment companies (i.e., those subject to the exclusion of stock options compensation for NEDs) and control companies (i.e., those not subject to the exclusion) after the implementation of the King IV code. However, the results show that the coefficient of the lower-order interaction term NEDcomDum*FP is positive but not statistically significant. This suggests that there was no significant difference in the sensitivity of executive pay to market-based performance between treatment companies and control companies over the entire sample period. Therefore, the study did not find support for the incentive alignment or rent extraction views, which suggests that the exclusion of stock options for NEDs would have a significant impact on executive pay-performance sensitivity.

5.4.2. Placebo test results

Using the placebo tests, the analysis of the results is consistent with the difference-in-difference method on the sensitivity of executive pay to returns on assets and Tobin’s q for the first year after the effective year of the King IV principles. By conducting placebo tests, we can demonstrate that the results obtained from the main analysis are not driven by arbitrary categorizations or chance. Instead, they reflect meaningful and consistent patterns specific to NEDs executive compensation. This strengthens the overall credibility and reliability of the study’s findings, enhancing the confidence in the observed differences between the two types of firms in terms of executive pay and firm performance.The results show that the compulsory removal of stock options for NEDs had a significant effect on the executive pay to ROA. The placebo model results showed a 1% significant negative effect, which contrasts with the difference-in-difference method where the effect is insignificant, suggesting that the compulsory removal of stock options for NED as seen in Table .

Table 8. NEDs compensation and executive performance pay sensitivity (Placebo test)

5.4.3. Robustness check using generalized method of moment

The robustness analysis was conducted to examine the whether the exclusion of executive pay influence the firm performance using another model. The Generalized Method of Moment (GMM) was employed as the analytical approach to ensure the reliability and validity of the findings of the DID fixed effect. By applying GMM, we aimed to assess the stability of the observed associations under different econometric models and specifications as presented in Table . Initial pre-diagnostic assessments were carried out to verify the absence of serial correlation by examining autocorrelation and implementing necessary corrections. As part of this study, post-diagnostic checks, such as AR (1) and AR (2), were employed to identify the order of serial correlation and determine the optimal order that improved the model’s performance. Remarkably, the same results were obtained using the dynamic GMM. The analysis revealed the presence of first-order autocorrelation in the two robust models, leading to the adoption of AR(1) to rectify the model, yielding a significant outcome (AR(1) = 1479, p = 0.003, < 0.05, AR(2) = 2689, p = 0.001). To assess the instrumental validity of the dynamic GMM, the Hansen and Sargan test was conducted, revealing insignificant p-values, indicating a lack of instrumental validity in the GMM model.

Table 9. Robustness analysis using GMM

5.4.4. Difference between financial and non-financial firms’ executive pay and firm performance using DID

The examination of the difference between financial and non-financial firms’ executive pay and firm performance is a crucial aspect of the study. Financial firms, such as banks or investment companies, often operate in a different economic and regulatory environment compared to non-financial firms, such as manufacturing or service-based companies. These differences can lead to variations in executive pay practices and the impact of executive compensation on firm performance. Understanding the disparity in executive pay and its association with firm performance between financial and non-financial firms provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of executive compensation schemes in different industry sectors. It allows researchers and practitioners to identify potential factors that contribute to divergent outcomes and tailor compensation practices accordingly.

To further examine the difference between financial and non-financial firms regarding executive pay and firm performance, a robustness analysis was conducted using the fixed effect of DID. The findings are presented in Table . Model 1 and Model 2 focused on the relationship between financial firms and executive pay. In Model 1, the coefficient for NEDcomDum was 0.272 (p < 0.05), indicating a significant positive association with post-King IV return on assets (ROA). Similarly, in Model 2, NEDcomDum showed a significant positive relationship with pre-King IV ROA, with a coefficient of 0.183 (p < 0.05). These results suggest that financial firms have higher executive pay-performance linkages compared to non-financial firms.

Table 10. Further analysis of difference between financial and non-financial firms

Model 3 and Model 4 examined the relationship between non-financial firms and executive pay. In Model 3, the coefficient for NEDcomDum was 0.272 (p < 0.05), indicating a significant positive association with post-King IV ROA. Similarly, in Model 4, NEDcomDum showed a significant positive relationship with pre-King IV ROA, with a coefficient of 0.202 (p < 0.05). These findings suggest that non-financial firms also exhibit a positive link between executive pay and firm performance. Furthermore, the interaction effects were assessed. Model 1 and Model 2 showed a significant positive interaction between NEDcomDum and K4 (p < 0.05), indicating that financial firms with higher NED representation and King IV compliance experienced a stronger association between executive pay and ROA. Model 3 and Model 4, on the other hand, did not demonstrate significant interaction effects between NEDcomDum and K4 for non-financial firms.

The presence of control variables, industry fixed effects, and year fixed effects in all models ensured the robustness of the findings. The results provide robust evidence of the difference between financial and non-financial firms in terms of the association between executive pay and firm performance. Financial firms exhibit a stronger linkage, while non-financial firms also demonstrate a positive relationship between these variables. By employing the DID methodology, we can provide rigorous evidence on the distinct relationship between executive pay and firm performance in financial and non-financial firms. This analysis contributes to a deeper understanding of the effectiveness and implications of executive compensation practices in different industry contexts, ultimately informing discussions on optimal executive pay structures and their impact on firm outcomes.

6. Summary and conclusions

The study’s results indicated that the mandatory exclusion of stock options incentives for NEDs resulted in a notable increase in the relationship between executive performance cash incentives and accounting-based performance for treatment companies. Nevertheless, there was no significant effect observed on the market-based measure. This study contributes to the limited research on secondary agency conflicts in the South African context. Previous studies have highlighted the lack of research in this area (Deutsch & Valente, Citation2013; Kor, Citation2006; Majoni, Citation2019; Perry, Citation2000). South Africa’s unique corporate environment presents an opportunity to investigate corporate governance mechanisms’ challenges in addressing secondary agency problems. The South African corporate setting is characterized by a distinct understanding of board independence, a high presence of institutional investors, and weaker stakeholder activism than in other contexts (Viviers et al., Citation2019). Despite the increasing interest in corporate governance in South Africa, limited attention has been given to secondary agency conflicts in this environment (Majoni, Citation2019). Past empirical studies on corporate governance in South Africa have primarily focused on primary agency problems between shareholders and management, overlooking the challenges of secondary agency conflicts (Ntim et al., Citation2015, 2019; Pamburai et al., Citation2015; Steyn & Stainbank, Citation2013).

The results of this study carry significant implications for future corporate governance policies and principles, not only in South Africa but also beyond. The findings specifically relate to the compensation of non-executive directors (NEDs). Specifically, the study sheds light on the impact of the compulsory exclusion of stock options incentives for NEDs on secondary agency conflicts, which can inform decisions about NED compensation. The study supports the King IV code’s recommendation for total compliance, suggesting that removing stock options incentives for NEDs does not weaken monitoring and may even improve it.The study results showed that the compulsory exclusion of stock options incentives improves monitoring in most cases. However, in other monitoring cases, it had no effect. This specified that stock options incentives in South Africa do not benefit shareholders in general. These results support the decision taken by the King IV corporate governance code to exclude compulsory stock options incentives as a form of compensation for NEDs. The study focused on executive performance compensation as its dependent variable, overseen by the remuneration and audit sub-committees. Given the specialized nature of financial reporting and compensation-related issues, the study’s focus on these sub-committees is appropriate. However, a limitation of the study is that it did not examine payment for audit and remuneration committee members specifically, as data on the members of the control group sub-committees needed to be included.

To properly examine the impact of the compulsory exclusion of stock options incentives for non-executive directors (NEDs) on the relevant committees overseeing the areas under investigation, it would have been ideal for focusing solely on audit and remuneration committee members. However, a lack of data on the members of the control group sub-committees hindered this approach, particularly in firms before the implementation of King IV (Ferguson, Citation2019; Natesan, Citation2020). Consequently, the study investigated the impact of the compulsory exclusion of stock options compensation for all NEDs. This is because audit and remuneration committees handle the dependent variables under consideration (Leith et al., 2021). A more detailed justification for focusing on all NEDs is presented in section three. It is important to note that the sample size of this study, which included 220 firms, is relatively small compared to other prior studies. For instance, Lahlou and Navatte (Citation2017) and Bierstaker (Citation2012) used larger sample sizes of 1,358 firms and 757 members, respectively. A smaller sample size might lead to skewed results and a lack of statistical power (Radier et al., Citation2016). Additionally, the Johannesburg Stock Exchange dimensions and alternative markets made matching treatment and control companies challenging. In this study, the treatment companies were more significant than the control companies (Leith et al., 2021). Subsequent studies could investigate the impact of mandatory stock options incentives for the audit committee and remuneration committee directors in settings falling under their purview, considering the significant effect of the King IV code on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) and alternative markets. The study focuses only on South Africa; further studies can be based on cross-country analysis to assess the full impact of compulsory compliance of excluding stock options globally.

Authors contribution

Agyeiwaa Owusu Nkwantabisa: Concept development, literature review and full manuscript Francis Sarpong: Conceptualization, methodology, and formal analysis. Nelly Joel Tchuiendem: Proof-reading, discussion, and conclusion. Winnifred Coleman: Revision and proof reading.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abdullah, S. N., & Nasir, N. M. (2004). Accrual management and the independence of the boards of directors and audit committees. International Journal of Economics, Management and Accounting, 12(1).

- Adams, R. B., Hermalin, B. E., & Weisbach, M. S. (2010). The role of boards of directors in corporate governance: A conceptual framework and survey. Journal of Economic Literature, 48(1), 58–28. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.48.1.58

- Adithipyangkul, P., & Leung, T. (2018). Incentive pay for non-executive directors: The direct and interaction effects on firm performance. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 35(4), 943–964. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-017-9534-z

- Agyei-Boapeah, H., Ntim, C. G., & Fosu, S. (2019). Governance structures and the compensation of powerful corporate leaders in financial firms during M&As. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing & Taxation, 37, 100285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2019.100285

- Ali, A., & Zhang, W. (2015). CEO tenure and earnings management. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 59(1), 60–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2014.11.004

- Allgood, S., & Farrell, K. A. (2000). The effect of CEO tenure on the relation between firm performance and turnover. Journal of Financial Research, 23(3), 373–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6803.2000.tb00748.x

- Allison, P. (2012). When can you safely ignore multicollinearity? | statistical horizons. https://statisticalhorizons.com/multicollinearity

- Alves, S. (2014). The effect of board independence on the earnings quality: Evidence from Portuguese listed companies. Australasian Accounting Business & Finance Journal, 8(3), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.14453/aabfj.v8i3.3

- Andres, C. (2011). Family ownership, financing constraints and investment decisions. Applied Financial Economics, 21(22), 1641–1659.

- Armstrong, C., Larcker, D., Ormazabal, G., & Taylor, D. (2013). The relation between equity incentives and misreporting: The role of risk-taking incentives. Journal of Financial Economics, 109(2), 327–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2013.02.019

- Artiga González, T., & Calluzzo, P. (2020). A new breed of activism. Finance Research Letters, 37, 101369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2019.101369

- Baker, D. (2019). Reining in CEO compensation and curbing the rise of inequality. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/reining-in-ceo-compensation-and-curbing-the-rise-of-inequality/

- Bausch, A., Hunoldt, M., & Matysiak, L. (2009). Superior performance through value-based management. Handbook utility management, 15–36.

- Bebchuk, L. A., & Fried, J. M. (2006). Pay without performance: Overview of the issues. Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(1), 5–24.

- Bebchuk, L. A., Grinstein, Y., & Peyer, U. (2010). Lucky CEOs and lucky directors. The Journal of Finance, 65(6), 2363–2401. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01618.x

- Bereskin, F. L., & Cicero, D. C. (2013). CEO compensation contagion: Evidence from an exogenous shock. Journal of Financial Economics, 107(2), 477–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2012.09.005

- Bierstaker, J. (2012). Audit committee compensation, fairness, and the resolution of accounting disagreements. https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=f_7v09sAAAAJ&hl=en

- Billett, M. T., Garfinkel, J. A., & Yu, M. (2017). The effect of asymmetric information on product market outcomes. Journal of Financial Economics, 123(2), 357–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2016.11.001

- Bindert, C. M. (2010). The impact of CEO compensation on firm performance in the oil industry. [ CMC Senior Theses]. 47. Assessed from https://schorlarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/47

- Boakye, D. J., TIngbani, I., Ahinful, G., Damoah, I., & Tauringana, V. (2020). Sustainable environmental practices and financial performance: Evidence from listed small and medium‐sized enterprise in the United Kingdom. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(6), 2583–2602.

- Brick, I. E., Palmon, O., & Wald, J. K. (2006). CEO compensation, director compensation, and firm performance: Evidence of cronyism? Journal of Corporate Finance, 12(3), 403–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2005.08.005

- Bussin, M. (2015). (PDF) CEO pay-performance sensitivity in the South African context. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281361133_CEO_payperformance_sensitivity_in_the_South_African_context

- Byard, D., & Li, Y. (2004). The impact of option-based compensation on director independence. Review of Accounting and Finance, 3(4), 21–46.

- Campbell, J. L., Hansen, J. C., Simon, C., & Smith, J. L. (2011). Audit committee stock options and financial reporting quality after the Sarbanes-Oxley act of 2002. Managerial Auditing Journal, 33(2), 192–216.

- Cao, J., Pan, X., & Tian, G. (2011). Disproportional ownership structure and pay–performance relationship: Evidence from China’s listed firms. Faculty of Commerce - Papers (Archive), 541–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2011.02.006

- CECI. (2021). South Africa number of listed companies: JSE | Economic Indicators | CEIC. https://www.ceicdata.com/en/south-africa/johannesburg-stock-exchange-number-of-companies/no-of-listed-companies-jse

- Certo, S. T., Daily, C. M., & Dalton, D. R. (2001). Signaling firm value through board structure: An investigation of initial public offerings. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(2), 33–50.

- Chen, X., Cheng, Q., & Wng, X. Does increased board independence reduce earnings management? Evidence from recent regulatory reforms. (2014). American Accounting Association Annual Meeting, 20(2), 899–933. Research Collection School Of Accountancy.management. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-015-9316-0

- Cheng, J. Y. J., Groysberg, B., Healy, P., & Vijayaraghavan, R. (2021). Directors’ perceptions of board effectiveness and internal operations. Management science, 67(10), 6399–6420.

- Chhaochharia, V., & Grinstein, Y. (2009). CEO Compensation and board structure. The Journal of Finance, 64(1), 231–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2008.01433.x

- Cobbinah, B. B., Cheng, Y., Milly, N., & Sarpong, F. A. (2020). Relationship between determinants of financial assistance and credit accessibility of small and medium-enterprises (sme’s): A case study of sme’s in Takoradi metropolis in the western region of ghana. Open Journal of Business and Management, 9(1), 430–447. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2021.91023

- Conway, S. L. (2012). Guidelines for corporate governance disclosure-are Australian listed companies conforming?. Journal of the Asia-Pacific Centre for Environmental Accountability, 18(1), 5–24.

- Conyon, M. J., & He, L. (2016). Executive compensation and corporate fraud in China. Journal of Business Ethics, 134(4), 669–691. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2390-6

- Core, J., & Guay, W. (1999). The use of equity grants to manage optimal equity incentive levels. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 28(2), 151–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-41019900019-1

- Council, F. R., & Britain, G. (2012). FRS 100: Application of Financial Reporting Requirements. FRC Publications.

- Crutchley, C. E., & Minnick, K. (2012). Cash versus incentive compensation: Lawsuits and director pay. Journal of Business Research, 65(7), 907–913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.05.008

- Dalnial, H., Kamaluddin, A., Sanusi, Z. M., & Khairuddin, K. S. (2014). Accountability in financial reporting: Detecting fraudulent firms. Procedia-Social & Behavioral Sciences, 145, 61–69.

- Daniliuc, S., Li, L., & Wee, M. (2021). Busy directors and firm performance: A replication and extension of Hauser (2018). Accounting & Finance, 61(S1), 1415–1423. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12631

- Deutsch, Y., & Valente, M. (2013). Compensating outside directors with stock: The impact on non-primary stakeholders. Journal of Business Ethics, 116(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1447-7

- Dorff, M. B. (2004). Does one hand wash the other? Testing the managerial power and optimal contracting hypotheses of executive compensation. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/SSRN.574861