Abstract

Employee engagement is not only a temporary attractive topic but gradually becomes the focus of attention of managers and scholars, especially in the travel industry in the face of shocks due to Covid-19. This study, under the guidance of social exchange theory, has proposed a meta-analytic framework examining the relationship between two dimensions of engagement, namely job and organizational engagement, and organizational culture. The results of data analysis from 338 employees of travel agencies in Hanoi, a major tourism center of Vietnam, have enriched the literature on the role of organizational culture in fostering organizational engagement through job engagement by providing perspective from a developing country during the pandemic. The paper also provides suggestions for scholars in investigating the promoters of engagement and implications for managers in developing organizational culture to achieve the dual benefits related to job and organizational engagement.

1. Introduction

Employee engagement captures the attention of businesses around the world because its benefits include not only retaining a talented and highly productive workforce but also improving customer satisfaction and the reputation of the business (Alam et al., Citation2021; Sacher & Lal, Citation2017; Sendawula et al., Citation2018). The importance of employee engagement is even more emphasized in the tourism and travel industry—which is known as a labor-intensive sector, where human resources make a decisive contribution to service quality and customer experience (Aslam et al., Citation2020; Pompurová et al., Citation2022). Moreover, compared with other services, the high seasonality with relatively large and frequent fluctuations in personnel of the travel industry also poses a greater challenge for managers of travel agencies. Beyond maintaining employee satisfaction and commitment, they need to keep employees engaged in the role of a service provider and aligns with the long-term direction of the business. Specifically, due to the serious impact of the Covid-19, the employee-organization linkage became looser and more vulnerable as numerous tourism employees were forced to suspend their jobs during the epidemic, which greatly affected their satisfaction and engagement (Barba-Sanchez et al., Citation2022; Hassanein & Özgit, Citation2022; Jibril & Yesiltas, Citation2022). Thus, during and after the pandemic, the topic of employee engagement continues to fascinate scholars, consultants, and practitioners alike.

Particularly, in Vietnam, tourism and travel is a crucial industry that not only strongly boosts the country’s economic growth with a contribution of about 9.2% to GDP and millions of jobs provided in 2019, but also has a spillover impact on many other sectors such as retail, entertainment, construction… (VNAT, Citation2020). When the pandemic unfolded, tourism and travel was the first industry affected by strict regulations on social distancing and travel restrictions between countries, but the last one that recovered when the pandemic was under control, following manufacturing and other essential services such as retail and logistics (Zaman et al., Citation2021). Specifically, personel in the travel industry experienced strong fluctuations during COVID-19 with the majority of employees facing job loss, furlough, or reduced working hours (GSO, Citation2021). Along with the general change in the world, the Vietnamese travel industry is facing considerable difficulties in recovering from the pandemic, the foundation of which is attracting and maintaining a skilled and engaged workforce. Employee engagement is once again recognized more seriously when a few businesses still maintain an engaged workforce, who go through challenges with the organization after a difficult time, there will be momentum to break through after the pandemic (Peterson & DiPietro, Citation2021).

In the literature, scholars are gradually approaching engagement as a multidimensional concept, including two main dimensions, job and organizational engagement (Bailey et al., Citation2017). However, most of the research has focused on job engagement while a modest number of empirical studies have addressed these two dimensions of engagement simultaneously, especially in the travel industry (Kim & Kim, Citation2021; Phan et al., Citation2023; Saks, Citation2019). In many available studies, the focus on job engagement was to help businesses move towards the goal of individual performance improvement. Meanwhile, moving towards organizational engagement could bring long-term value to the organization, especially in the context of high volatility business such as during COVID-19 (Kundu & Lata, Citation2017; Saks, Citation2019). Therefore, attention should be shifted from trying to promote job engagement to more concerned with how to improve organizational engagement, and preferably to achieve these two dimensions of engagement simultaneously.

Secondly, faced with the problem of employee engagement improvement, developing organizational culture is a feasible, reasonable direction and even strategically imperative to managers of travel agencies because it both sustains a skilled and engaged workforce and enhances competitiveness based on making a difference in value and experience for customers (AlShehhi et al., Citation2021; Bendak et al., Citation2020). Although studies on organizational culture and employee engagement are increasingly being carried out (Bhardwaj & Kalia, Citation2021; Gabel-Shemueli et al., Citation2019; Latta, Citation2020), the role of organizational culture in improving engagement has not been comprehensively recognized. A few studies have focused on only one cultural dimension, a specific type of culture (Huhtala et al., Citation2015; Rofcanin et al., Citation2017), or have considered culture as one of the organizational factors that could have an impact on employee engagement without clearly describing which cultural characteristics are important determinants of engagement (Chittiprolu et al., Citation2021; Kwon & Kim, Citation2020). This partly made it difficult for academics and practitioners to determine a handbook for the development of culture towards engagement. A better understanding of the complex mechanism of improving engagement through organizational culture is also significant in the context of travel industry because the culture of travel agencies, with highlights that stand out from the other services, may open up opportunities for businesses to be distinct. Thirdly, exploring the mediating role of job engagement in the relationship between organizational culture and organizational engagement is scarce. Besides a limited number of theoretical studies that have addressed the mediating role of job engagement, very few empirical studies have been conducted to test this relationship (Rai & Maheshwari, Citation2021; Sendawula et al., Citation2018). Meanwhile, insight into the complex relationship between these constructs will provide more specific implications for travel agencies in focusing resources on employee engagement improvement and achieving greater value in the long run. Fourthly, the lack of studies on this topic from the perspective of developing countries, where tourism constitutes an important pillar for post-pandemic economic recovery, should be addressed because several solutions drawn from studies conducted in developed countries could be less feasible or not effective in developing countries like Vietnam (Cardon et al., Citation2021; Oriade et al., Citation2021).

Given these research requirements, a comprehensive research framework that takes into account the mediating role of job engagement to explain the importance of organizational culture in fostering job and organizational engagement simultaneously is an essential requirement for enriching the literature. In addition, exploring this topic in the context of the travel industry in Vietnam during the Covid period was expected to bring a new perspective and interesting results compared to the conclusions obtained from the previous studies.

To find the key to the practical problems and partially fill the aforementioned research gaps, this study endeavors to examine the role of organizational culture in improving job engagement, and ultimately creating important changes in organizational engagement in the context of travel agencies in Vietnam. Accordingly, the authors aim to explore the relationship between organizational culture, job engagement and organizational engagement, including the mediating role of job engagement, and to outline the variety in the job and organizational engagement of different groups of employees in travel agencies.

The originality of this study comes from the research approach on employee engagement and the perspective from a special context. On the one hand, different from the previous studies which have focused more on job engagement—the dimension affecting the immediate work results, we concentrated on organizational engagement—the dimension is more closely related to overall performance and long-term success of the organization (Saks, Citation2019). We used Social Exchange theory (SET) as a foundation to explore engagement from an organizational sociological perspective, thereby clarifying the influencers of engagement at the organizational level (Bailey et al., Citation2017). Under the guidance of the SET, we have searched for a solid way to improve organizational engagement in the long-term based on strengthening the mediator, job engagement, with the starting point of cultural change in travel agencies. On the other hand, we have observed more deeply the employee engagement in the travel industry. This industry, with an important contribution to the economies of many developing countries like Vietnam, is urgently looking for solutions in terms of human resources but less discussed in the academic literature than many other services (Baum et al., Citation2020). This unique context will allow us to see similarities and differences compared to other studies.

From the results obtained, the study will theoretically contribute an analytical framework that allows us to comprehensively explore the relationship between cultural environment of the organization and two different but related dimensions of employee engagement. The paper also provides empirical evidence to answer the need for further research on mediators in the theoretical framework of engagement, specifically, job engagement should be considered as the key behind the mechanism of organizational culture’s influence on organizational engagement at travel agencies. The study also contributes interesting remarks on organizational culture and engagement related to the characteristics of the travel industry in developing countries during Covid-19. Practically, the study’s contribution relates to suggestions that help businesses figure out how to change their culture to attract, retain, and engage talented staff to better prepare for post-pandemic recovery and long-term goals.

Before providing tailor-made solutions for travel agencies in developing countries like Vietnam, this study begins with a review of the literature on engagement and its relationship with organizational culture. Based on that, a meta-analytic framework is proposed to explore the influence of organizational culture on two dimensions of engagement. Next, the authors discuss and draw implications for scholars in deepening ways to promote the ultimate goal, organizational engagement, and suggest implications for managers in developing organizational culture towards employee engagement.

2. Literature review

2.1. Employee engagement

Employee engagement has gone beyond the trend of the moment and become an attractive topic for more and more researchers, which is associated with efforts to better understand and encourage employees in the organization. Kahn’s (Citation1990) definition, which dissects physical, cognitive, and psychological facets of engagement, is a potential starting point for many of the ideas of 21st-century researchers. Accordingly, engagement is concretized by fully harnessing one’s complete self in his or her work role in the organization. Engaged employees will invest a lot of effort and time to improve their skills and knowledge to adapt and be more creative in the workplace (Jia et al., Citation2022). Although initially, many scholars mentioned engagement, they mainly revolved around job engagement. Several studies later argued that engagement should be recognized more broadly as a multi-dimensional concept, not just covering the engagement with the job but also with the organization (Saks, Citation2019; W. Schaufeli & Salanova, Citation2011). Obviously, diversity in the level of job and organizational engagement always exists among individuals in the workplace (Saks & Gruman, Citation2014). In other words, employee engagement refers to the total physical, cognitive and emotional dedication of the employees to the role in their job (job engagement) and the role as a member of the organization (organizational engagement) (Christian et al., Citation2011; Saks, Citation2019).

Various theories have been cited to explain engagement, among which the SET allows to examine the drivers of engagement from the organizational sociological perspective (Bailey et al., Citation2017). This is significantly different from existing studies based on theoretical frameworks, such as job demands—resources framework, conservation of resources theory or broaden-and-build theory, which focus on the individual level (Schaufeli, Citation2014). In line with the SET, employee engagement should be considered as the result of reciprocal exchange between employees and their organization. When the organization values and brings more benefits to employees, employees will repay with a higher level of engagement (Alfes et al., Citation2013). This theory also implies that employee engagement is not only associated with the job but also with the organization. The distinguishment between the two dimensions of engagement highlights the significance of this concept to the organization when compared with other familiar concepts such as employee satisfaction, commitment, and performance. On the one hand, job satisfaction and performance could not create sustainable value for an enterprise if that employee is less engaged and is likely to leave the organization at any time (Rai & Maheshwari, Citation2020). On the other hand, commitment to the organization is often explained by a sense of obligation that does not stem from voluntary (engaged) will not bring value to the organization (Meyer & Allen, Citation1991).

The significance of engagement for improving outcomes such as employee performance, productivity, profitability, and customer satisfaction, has been mentioned in various papers (Aslam et al., Citation2020; Sendawula et al., Citation2018). In more detail, each dimension of engagement has its own benefit for the organization. Job engagement is often mentioned as a predictor of outcomes related to in-role behaviors of employees, significantly determining absenteeism and turnover intention (Aslam et al., Citation2020, Rai & Maheshwari, Citation2020; Sadaqat & Ghulam Abid & Francoise Contreras, Citation2022). Whilst, organizational engagement is more closely related to organizational-level variables such as organizational citizenship behavior, firm performance, and still has an important influence on employee in-role behaviors such as turnover intention (Barrick et al., Citation2015; Malinen & Harju, Citation2017; Saks, Citation2019).

In the travel industry with high human contact, where service quality depends mainly on the effective interaction between employees and customers, engaged employees not only lead to productivity enhancement, but also contribute to a superior customer experience and keep them satisfied (Aslam et al., Citation2020). Promoting engagement becomes a challenge and more urgent in the context of the pandemic, when all business activities were disrupted, and staff’s physical and psychological well-being were also seriously affected. During the early stages of the pandemic, some studies showed a slight increase in employee engagement (Cardon et al., Citation2021; J. Harter, Citation2020), but in the period during and after Covid-19, the fluctuation of employee engagement is still a big question mark for managers, especially in the field of tourism in developing countries, that calls for more research to continue and expand the discussion of this topic.

2.2. Organizational culture

There are a few topics that have been discussed very early but never lose their heat in academic discussions like organizational culture. From the most influential definition of Schein (Citation2010), organizational culture is considered as a set of assumptions shared and recognized by individuals in an organization, resulting from interactions of the organization with the internal and external environment. Organizational culture is expressed and maintained permanently in the organization, thereby shapes the attitudes and behaviors of employees in the workplace, such as engagement (Bhardwaj & Kalia, Citation2021; Guiso et al., Citation2015). According to the SET, in order to determine the appropriate intervention that allows to improve employee engagement, it is necessary to pay attention to the organizational factors, including the organizational culture (Bailey et al., Citation2017).

The unique functional characteristics of each industry play a crucial role in defining an organization’s culture (Bavik, Citation2016; O’Reilly & Chatman, Citation1996). This is even more obvious in service industries as employee involvement and human interactions determine the customer experience and the outcome of the service delivery (Walker & Miller, Citation2009). Therefore, organizational culture, which is seen as a potential tool to regulate employee behavior and at the same time, facilitate the service delivery process and make a significant contribution to competitiveness, becomes one of the top common preoccupations of managers (Gustafson, Citation2012; Oriade et al., Citation2021). Interestingly, studies on culture within the travel industry context are relatively scarce in comparison with the hospitality industry (Bavik, Citation2016). In general, in studies on organizational culture in the tourism industry, the dimensional approach is suitable for measuring different facets of culture by facilitating the discovery of the nature of culture and highlighting the unique cultural dimensions associated with the characteristics of the business industry (Bavik, Citation2016; Dawson et al., Citation2011; Jung et al., Citation2009; Tepeci & Bartlett, Citation2002).

Regarding travel businesses, although there is an outpouring of cultural dimensions that have been mentioned by scholars, it seems to still have intersections in certain dimensions. Among these dimensions, Result orientation and Innovation have been found in most research in the service sector and especially in the tourism and travel industry (Oriade et al., Citation2021; Tepeci & Bartlett, Citation2002). Indeed, these dimensions allow more flexibility for all stages of the service delivery and facilitate meeting the increasingly strict requirements of customers and gain a foothold in the fiercely competitive market (AlShehhi et al., Citation2021; Verbeeten & Speklé, Citation2015). Further, Formality, Customer orientation, Employee development, and Team orientation have been emphasized as unique aspects of the tourism industry, allowing the service providing to take place smoothly, effectively controlling resources and providing superior value for customers (Bavik, Citation2016; Dawson et al., Citation2011; Gustafson, Citation2012). Cultural dimensions of Social responsibility and Fair compensation have been not only mentioned in studies of the tourism and travel industry, which is closely related to the environment and communities, but are even more concerned in the context of the increasing awareness about sustainability and the COVID-19 pandemic (Mgammal et al., Citation2022; Oriade et al., Citation2021). Moreover, because of its close relation with changes in the business environment (Schein, Citation1990), organizational culture needs to be better understood during the COVID-19 crisis associated with changes in the nature of working and interacting among members of the organization. Several cultural dimensions are mentioned more during this tumultuous period such as Formality, Integrity, while others receive less attention (Cardon et al., Citation2021; R. Singh, Citation2016).

2.3. The influence of organizational culture on employee engagement and the mediating role of job engagement

Developing organizational culture is considered as a hidden but potential driving force of engagement because that could affect the bond between employees and the organization by strengthening trust, affection and commitment of employees to the organization (Justwan et al., Citation2018). Organizational culture not only affects employees’ outward behaviors but also touches deeper into their attitudes, cognition, and emotions (Oriade et al., Citation2021). However, from the literature review on the relationship between organizational culture and employee engagement, several research gaps need to be dealt with.

Firstly, in understanding the drivers of engagement, many scholars and practitioners alike focus their attention on job engagement, as demonstrated by the popularity of the UWES scale or the Gallup Q12 in the early years of the 21st century (Bailey et al., Citation2017; J. K. Harter et al., Citation2002; W. B. Schaufeli et al., Citation2002). Notably, it is known that organizational engagement, rather than job engagement, is the endpoint that businesses should aim for because of its proximal effect on performance improvement, the number of empirical studies referring to organizational engagement is quite modest (Saks, Citation2019). This further underlines the need to explore more about this dimension of engagement.

Secondly, most studies have underestimated the role of culture, which is only considered as one of the organizational factors influencing employee engagement (Choy & Kamoche, Citation2021; Latta, Citation2020). These studies have focused on the influence of a particular cultural type or examined the overall impact of cultural dimensions on engagement (Kwon & Kim, Citation2020). This somewhat limits the significance of the conclusion since organizational culture is a multidimensional concept and needs to be considered comprehensively.

Thirdly, the influence of organizational factors in general, and organizational culture in particular, on organizational engagement through job engagement has been rarely investigated in prior studies (Gyensare et al., Citation2019). In terms of theoretical frameworks, various theories that allow elucidation of the mechanism underlying job engagement often narrow the point of view at the individual level. Therefore, it is necessary to further examine this issue from an organizational sociological perspective to consider antecedents of engagement at the organizational level (Bailey et al., Citation2017). The SET has proved relevant to explain the mediating role of job engagement but has been under-reported in previous studies (Saks, Citation2006). A few empirical studies have introduced job engagement as a mediator in the relationship between organizational engagement and factors related to personal psychological characteristics or job characteristics but have not properly acknowledged the role of organizational factors, such as organizational culture (Latta, Citation2020; Rai & Maheshwari, Citation2021; Sendawula et al., Citation2018). In particular, this relationship has not been exploited deeply in the travel context and the results are still inconsistent (Choy & Kamoche, Citation2021). In terms of context, most of the research on engagement and its relationship with organizational culture has been conducted from the perspective of Western developed countries, so the solutions offered may be occasionally difficult to apply in developing countries in Asia (Cardon et al., Citation2021; Oriade et al., Citation2021). Despite research efforts, clarifying the way to improve employee engagement through organizational culture in the context of travel industry in Asia in general, and Vietnam in particular, is still under-reported compared with other regions. Practically, the spotlight is directed on improving organizational engagement, it requires managers to identify and promote all cultural dimensions that have both direct and indirect impacts on organizational engagement through job engagement. Irrespective of the research efforts to meet the theoretical and practical requirements, the relationship between these constructs is still unclear and calls for more empirical research (Saks, Citation2019).

From the above impulses, it is necessary to propose a meta-analytic framework that allows quantifying and exploring in more detail the mechanism of the influence of organizational culture on employee engagement encompassing the mediating role of job engagement within the context of the travel industry.

2.4. Analytical framework and hypotheses development

The previous theoretical and empirical studies have provided rationales to propose a meta-analytic framework to thoroughly examine the influence of organizational culture on organizational engagement taking into account the mediating role of job engagement in the context of travel business in Vietnam.

The Vietnamese travel business context should be taken into account while proposing the analytical framework. In 2019, Vietnam’s tourism in general, and travel in particular, created a highlight when it was rated as one of the ten countries with the fastest growth in tourism in the world with a record of welcoming nearly 105 million visitors, increased by more than 16% compared to the previous year, directly contributed more than 9% of the GDP of the country and created nearly 5 million jobs (VNAT, Citation2020). However, similar to many other countries in the world, Vietnam also suffered a huge shock due to the COVID-19 outbreak (Zaman et al., Citation2021). Changes in the number of international and domestic tourists have a direct impact on the operations of travel agencies with the reduction of more than 70% of staff in the two years 2020–2021, and the contribution to the GDP of Vietnam down more than four times to 2% by 2021 (VNAT-Vietnam National Administration of Tourism, Citation2022a). The travel industry began to prosper in early 2021 thanks to efforts to stimulate domestic demand and the return of international tourists as social distancing regulations gradually eased (McKinsey&Company, Citation2021). Optimistic forecasts about the rapid recovery of Vietnamese tourism and travel industry pose challenges for managers in attracting and retaining skilled and engaged employees. Given that the travel industry is one of the important drivers of Vietnam’s tourism recovery, the author has more motivation to find a way to promote an engaged workforce at travel agencies through organizational culture development.

For a better understanding of the mechanism behind the relationship between organizational culture and two dimensions of engagement, this study adopted the SET as the theoretical foundation. Relying on the SET, the authors suggest that efforts to develop organizational culture could directly improve organizational engagement significantly and indirectly through promoting job engagement. This theory pertains to the relationship between the employee and the organization, which is built and maintained based on the norm of reciprocity (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005). Organizational culture, which is an expression of the organization’s concern for employees, will make them want to reciprocate with greater engagement with the organization. In addition, the SET is incorporated to propose the mediating role of job engagement as the organizational culture creates a favorable environment for the performance of the job role and the member role at the travel agency. Therefore, the staff is likely to repay by engaging initially with the job, which is obviously perceived as worthwhile, and then engaging with the organization, which benefits in the long run (Guest, Citation2014; Rai & Maheshwari, Citation2021).

In the proposed analytical framework, cultural dimensions were identified based on a combination of literature and practice. First of all, cultural dimensions mentioned as drivers of at least one of the two dimensions of engagement were included in the framework. The interference between the drivers of job and organizational engagement mentioned in previous empirical studies suggests that it is possible to test the influence of these factors on both dimensions of engagement (Rai & Maheshwari, Citation2021). Next, this study prioritized cultural dimensions associated with the tourism and travel business context, especially in Vietnam. The dimensions drawn from the literature were then confirmed through in-depth interviews with three experts on human resource management, organizational culture, tourism and travel management. Therefore, in the proposed framework, organizational culture consists of eight dimensions: Result orientation, Innovation, Formality, Customer orientation, Employee development, Team orientation, Social responsibility, Fair compensation.

In terms of empirical evidence, Result orientation can motivate employees to be willing to make efforts and devote their abilities to work and to be more engaged (W. B. Schaufeli et al., Citation2009). Innovation dimension that encourages new ideas, and even accepts failures, makes employees feel psychologically safe during their work, which in turn leads to employee engagement (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2008; Halbesleben & Wheeler, Citation2008; Kahn, Citation1990). Formality, with a high degree of standardization, an emphasis on control, and highly in favor of following rules and regulations, maintains a systematic and orderly association between individuals and the organization, thereby making them more engaged (Bradley et al., Citation2006; Devi, Citation2009; Yang et al., Citation2014). Employees at an enterprise with a customer-oriented culture and towards superior service quality often have higher engagement (Anaza et al., Citation2016; Taneja et al., Citation2015). In addition, they will also feel significant benefits from the organization which focuses on employee development, thereby making them more engaged, and want to align their career with the future of the organization (Ahmadi et al., Citation2012; Levinson, Citation2007). Team orientation, which facilitates interactions and close relationships in the workplace, is believed to make employees feel more meaningful when performing work at the organization and has a positive impact on employee engagement (Lockwood, Citation2007; May et al., Citation2004). Social responsibility, which shows that the organization considers the interests of stakeholders including employees in all business decisions, will also promote employee engagement (Hu et al., Citation2020; S. Singh & Singh, Citation2019; Taneja et al., Citation2015). Fair compensation is seen by employees as an organization’s recognition of the achievements they have created, so they will feel more mentally secure and more engaged (Kahn, Citation1990; Saks, Citation2006; Taneja et al., Citation2015).

Although theoretical studies have mentioned organizational culture as a driver of engagement in general (Frenking, Citation2016; Saks, Citation2019), empirical studies addressing and comparing the influence of each cultural dimension on job and organizational engagement are still limited, especially the influence on the latter (Saks, Citation2006). Due to the lack of studies examining the influence of organizational culture on job and organizational engagement simultaneously, it is difficult to come up with specific hypotheses for each cultural dimension. In addition, a strong relationship was predicted between these two dimensions of engagement (Saks & Gruman, Citation2014) motivated the authors to hypothesize the influence of organizational culture on organizational engagement based on both empirical bases related to job engagement as follows:

H1-8a:

Organizational culture (Result orientation, Innovation, Formality, Customer orientation, Employee development, Team orientation, Social responsibility, Fair compensation) has a positive influence on job engagement.

H1-8b:

Organizational culture (Result orientation, Innovation, Formality, Customer orientation, Employee development, Team orientation, Social responsibility, Fair compensation) has a positive influence on organizational engagement.

In this study, the mediating role of job engagement is elicited from both theoretical and practical support. Theoretically, the SET is a solid foundation for exploring the complex relationship between organizational culture and the two dimensions of engagement (Saks, Citation2006). Accordingly, the engagement of employees is formed and strengthened based on the reciprocal exchange between them and the organization (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005). Indeed, corporate culture signals the organization’s concern for employees and brings value to them, thereby, they feel the need to repay the organization through investing greater efforts at work and being more engaged. On the other hand, employees are more likely to be engaged with the organization if they perceive that the organization provides them with a supportive cultural environment and makes them more engaged in their job (Meng & Berger, Citation2019; Ogueyungbo et al., Citation2020; Rahman et al., Citation2020).

In empirical studies, the mediating role of job engagement in the relationship between culture and organizational engagement has been suggested for two main reasons. First, fluctuations in job engagement will lead to changes in organizational engagement, in other words, job engagement could be considered an important premise of organizational engagement (Rai & Maheshwari, Citation2021; Saks & Gruman, Citation2014). Second, although several scholars argued that job and organizational engagement should be predicted by different factors related to the job and organization respectively, a significant overlap between the predictors of these two dimensions of engagement has been recorded in the existing studies (Kwon & Kim, Citation2020; Saks, Citation2019). Therefore, it is logical to infer the mediating role of job engagement since several cultural dimensions driving job and organizational engagement overlap remarkably in previous studies (Latta, Citation2020; Lesener et al., Citation2020, Rai & Maheshwari, Citation2020; Saks, Citation2019; Phan et al., Citation2023). From the SET combined with various empirical evidence, we have hypotheses:

H1-8c:

Job engagement mediates the relationship between organizational culture (Result orientation, Innovation, Formality, Customer orientation, Employee development, Team orientation, Social responsibility, Fair compensation) and organizational engagement.

Along these lines, for measuring job and organizational engagement, the scales of Saks (Citation2019) were adopted. Organizational culture of travel agencies in Vietnam was defined based on the OCP model suggested by Tepeci and Bartlett (Citation2002) and Oriade et al. (Citation2021), which allows encompassing most of the earlier cultural dimensions. These scales were all adapted to the characteristics of the travel business in Vietnam. First of all, the authors based on the scales that have been verified for the reliability of previous studies to propose a preliminary set of scales (Table ). These scales were then translated into Vietnamese and double-checked by two language experts. Next, the results of in-depth interviews with five experts and five employees were combined with secondary documents on corporate culture, employee engagement and the travel and tourism industry in Vietnam to adjust the wording and clarify the content of some scales in accordance with the research context in Vietnam. The adjusted scales were sent back to the interviewees to confirm the changes and obtain the final questionnaire used in the large-scale survey. In addition to socio-demographic information, the questionnaire consisted of 59 questions designed on a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

Table 1. Descriptions of measurement scales

3. Methodology

3.1. Data collection

The testing of hypotheses was conducted based on data obtained from a questionnaire survey. The data collection procedure started with a focus on exploring the travel industry in Hanoi, where the largest number of travel agencies in Vietnam are located. In addition, with the expectation of drawing valuable lessons from this survey, we focused on travel agencies in Hanoi which have suffered huge fluctuations in human resources due to the COVID-19 aftermath. This is also the place where tourism has had a noticeable recovery after the first wave of the pandemic with nearly 19 million visitors in 2022, about five times more than in 2021 and 65% of the number of visitors in the year before the pandemic (HTD, Citation2022). Tourism and travel enterprises in Hanoi have also contributed significantly to the total tourism revenue of about 2.5 billion USD, reaching more than 55% compared to 2019 (HTD, Citation2022). Investigating this context will therefore allow us to find effective interventions for travel agencies to maintain an engaged workforce in a volatile business environment.

Survey participants were employees at travel agencies in Hanoi, who are critical to improving service quality, customer experience, and ultimately the success of the organization. The engaged workforce could help save costs, create competitiveness and difference from competitors (Peterson & DiPietro, Citation2021). Moreover, employees in this industry were susceptible to many changes due to the Covid pandemic including many issues affecting their psychology such as working remotely, interrupting work, or losing jobs (GSO, Citation2021).

Initially, we used purposive sampling to select travel agencies from the list published on the website of the Vietnam National Administration of Tourism (VNAT, Citation2021). Purposive sampling is consistent with the purpose of this study because it allows to identify participants who are knowledgeable about the research topics and provides deeper insights into these complex social topics (Robinson, Citation2014; Saunders et al., Citation2016). Compared with the random sampling, this technique helps us to limit the survey questionnaires filled out by employees from organizations with unclearly defined culture. In fact, it takes a certain amount of time for the process of organizational socialization to take place with newcomers, so that they can understand the organizational culture and have a clear opinion on whether or not they will engage with the job and the organization (Saks & Gruman, Citation2018). Therefore, the enterprises selected must be established before 2019 to ensure a certain level of employee engagement and taken-for-granted organizational culture. The author first contacted these travel agencies to ask for permission to send the questionnaire to employees. The survey period lasted from December 2021 to June 2022. This was the last stage of the 4th wave of covid taking place in the world and in Vietnam, where the tourism industry is heavily affected with the number of domestic and international tourists still plunging (VNAT, Citation2022b). During the survey period, access to employees was greatly hindered due to the strictness of social distancing regulations in Hanoi and the prevalence of remote working. The minimum sample size to conduct hypothesis testing should be five times the number of observed variables, which was 295 (Hair et al., Citation2014). However, after contacting employees based on lists provided by travel agencies, the number of employees who agreed to participate in the survey did not reach the allowable threshold. Realizing the difficulties of getting accessibility to the employees, we decided to consider the previous respondents as a starting point to use the snowball method (Parker et al., Citation2019). In some cases, the purposive sampling method has been used to determine the key informants, which in turn was followed by the snowball method (Brown, Citation2006; Tongco, Citation2007). The snowball method was conducted until a suitable sample size was reached to test the model and it appeared that the next referrer had participated in the survey (Hair et al., Citation2014).

The questionnaire was sent to employees via email with a Google form link. Through the questionnaire, the respondents expressed to what extent they agree or disagree with the statements related to organizational culture and employee engagement. Of 400 questionnaires sent, 342 questionnaires were collected, achieving a response rate of 86%. After excluding four questionnaires that were not fully completed, the data from 338 valid questionnaires was included in the analysis to test the scale and research hypotheses. The utilization of AMOS.20 helps to conduct structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis to test the relationship between the constructs in the proposed framework.

To control common method bias, we paid attention to both procedural and statistical strategies. We first reversed the order of observed variables to restrict respondents from answering based on inferences from the previous questions (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012). The questions after being adapted from the original scales were also improved based on the results of in-depth interviews with experts and employees. By prioritizing the simple words, adding specific examples related to the context of travel business in Vietnam, the questionnaire was constructed to avoid causing ambiguity, difficult to interpret for the respondents (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012). In addition, although the survey was conducted via email and online survey link, we also included a cover letter that clearly explains how the collected data would be used to bring value to the business and the employees, thereby helping participants give more accurate answers (Jordan & Troth, Citation2020). In terms of statistical approach, we conducted Harman’s one-factor test, which is commonly used in self-report studies (Fuller et al., Citation2016). The analysis results showed a single factor accounting for 28.7% of the variance, much lower than the proposed threshold of 50%, so common method bias was not present (Cooper et al., Citation2020).

Surveyed employees were diverse in terms of gender, age, education level, and seniority (Table ). Young staff under 35 years old accounted for more than 37%. Females made up the majority with about 63%. Employees were highly qualified with nearly 75% having a bachelor’s degree or higher. Those with less than 5 years of seniority accounted for nearly 60%.

Table 2. Descriptions of sample

3.2. Measurement tests

To verify the validity of the measurement model, convergent validity and discriminant were examined (Table ). The AVE coefficients were all above the acceptable threshold of 0.5, showing that latent variables have high convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Comparing the square root of the AVE and the inter-construct squared correlation estimates of each construct also ensured discriminant validity. The scores of construct reliability between 0.82 and 0.90 indicate that the scales were reliable (Hair et al., Citation2014).

Table 3. Descriptive analysis and measurement analysis

4. Data analysis and hypothesis testing

4.1. Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistical analysis and finding differences in responses between groups of respondents are informative for generalizing the perception of employees about organizational culture and their degree of engagement. All cultural dimensions were highly evaluated with a mean value greater than 3, except for Formality (Table ). That reflects cultural characteristics in Hanoi travel businesses, as most of them are small and medium-sized enterprises with poorly established procedures and policies, a compact and flexible structure, and a low level of specialization. On the other hand, the job and organizational engagement were all greater than 3.5. Looking deeply into each dimension of engagement, the results of the One-way ANOVA analysis showed significant differences in both job and organizational engagement by gender, age, and job position (Table ). In terms of seniority, the difference in organizational engagement between employees was noted. In addition, there was no difference in engagement by education level.

Table 4. ANOVA test (classification by gender, job position, age, and seniority)

4.2. Structural model and hypothesis testing

The tested structural model includes dimensions of engagement and organizational culture. Based on the combination of various indices including the values of chi-square/df, CFI, RMSEA, IFI, and TLI, the model fit is guaranteed (Table ).

Table 5. Model fit summary

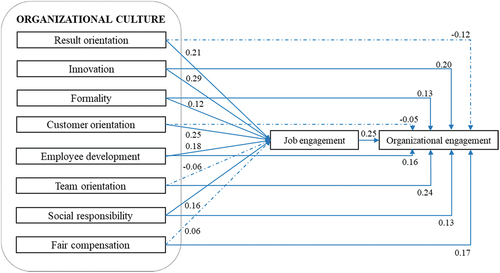

8 examined cultural dimensions explain 66% of the variation in job engagement while 68% of the change in organizational engagement was explained by the combined impacts of organizational culture and job engagement (Table ). The analysis results showed that all cultural dimensions have a meaningful direct influence on at least one dimension of engagement, in which there are four dimensions (Innovation, Formality, Employee development, and Social responsibility) impacting job and organizational engagement simultaneously.

Table 6. Summary of hypothesis tests

The mediating role of job engagement was verified based on the bootstrapping results. Accordingly, Result orientation and Customer orientation have no direct impact on organizational engagement but have an indirect impact through job engagement (Table ). Meanwhile, the mediating effect of job engagement in the relationship between Team orientation and Fair compensation was not supported (Figure ). The combination of these analysis results suggested that hypotheses H1-5a, H7a, H2-3b, H5-8b, H1-5c, H7c should be accepted.

Table 7. Summary of mediation tests

5. Discussions and implications

5.1. Main findings and discussions

Examining the interrelationship between organizational culture, job engagement and organizational engagement has elucidated the mechanism behind the motivating role of culture for engagement improvement.

Firstly, broadening the perspective to pay more attention to organizational engagement helps to identify cultural dimensions that have a dual impact on job and organizational engagement instead of just focusing on promoting job engagement-related dimensions like several previous studies. The role of culture has been demonstrated in improving not only job engagement but also organizational engagement. This result is consistent with the SET theory that employee engagement could be motivated based on the principle of reciprocity (Saks, Citation2019). Employees consider organizational culture as the organization’s efforts to bring values and benefits to them. They are then willing to engage with the organization as a commensurate return. The presence of the appropriate culture fosters a psychological bond in which employees engage and stay with the organization, which they believe will benefit them in the long term (Kwon & Kim, Citation2020).

In particular, the impact of Innovation was not only recognized on job engagement as in studies of Bakker & Demerouti (Citation2008), Halbesleben and Wheeler (Citation2008) but also on organizational engagement. In the context of a fluctuating environment, similar to the study of Hassanein and Özgit (Citation2022) that in the period of COVID-19 disrupting the operation of travel businesses, employees need to be listened to and more involved in order to innovate and be more responsive to the changing working environment. The role of Employee development for both job and organizational engagement, instead of just the former, has also expanded the suggestion of the previous scholars (AlShehhi et al., Citation2021). In line with the SET and Job Demands-Resources theory (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007), in order to maintain employee engagement in the context of the Covid-19, higher job demands need to be rebalanced by more both economic and socioemotional resources from the organization (Saks, Citation2019), including employee development through emphasis on training and prioritizing a clearer career path for employees. The influence of Social responsibility is explained by the fact that if travel agencies still pay attention to the interests of the community and stakeholders even during difficult times, employees will be more confident and optimistic about the future of the business, thereby want to be engaged with this job and organization for a long time (Kim & Kim, Citation2021). An intriguing finding is the prominent effect of Formality on both job and organizational engagement. This is different from the study of Cardon et al. (Citation2021) which has suggested that informality, especially in communication, is related to engagement in the blended work environment during the Covid-19. This could be explained based on the specifications of the travel industry. The standardization of service provision processes, and the system of rules and policies help employees to keep pace with the new working rhythm, create a corridor to maintain working order and interact within the organization even through technology-mediated communications (Gustafson, Citation2012).

Secondly, the study has clarified the role of job engagement in organizational engagement improvement and in the relationship between organizational culture and organizational engagement. This result has added to the rare number of models that address both forms of engagement simultaneously (Saks, Citation2019) and has further extended the implication of the SET theory. Accordingly, the reciprocal exchange between employees and the organization could eventually create organizational engagement when the organizational culture brings certain values that make employees engage with the job. On the one hand, job engagement is an important driver of organizational engagement. This adds empirical evidence about the direction of the relationship between these dimensions of engagement to the conclusions of Saks and Gruman (Citation2014). On the other hand, the results have supported the idea that job engagement mediates the relationship between organizational culture and organizational engagement. In fact, in tourism and travel industry, the job that employees, especially frontline employees, undertake is seasonal and high pressure as they have to serve and satisfy diverse and increasingly demanding customers (Gonzalez-González & García-Almeida, Citation2021). The connection between them and the organization is first formed from passion and engagement with the job, then built over time in the process of interacting with the organization and gradually becoming more engaged with the organization (Saks, Citation2019). This result has diversified the results of Barrick et al. (Citation2015), Rai & Maheshwari (Citation2020) on the influence of job- and organization-related variables, including organizational culture, on organizational engagement through job engagement.

Thirdly, the study revealed the difference in the level of job and organizational engagement between different groups of employees. Dissimilar to the results of Tsaur et al. (Citation2019) and Khodakarami and Dirani (Citation2020), the degree of engagement in the tourism and travel industry varies according to age, gender and seniority. Notably, young staff from Generation Z (born after 1995) in travel agencies showed lower engagement. This is related to the difference in work value of Generation Z, who are also looking for a job and career stability like previous generations but give more priority to promotion and self-development (Maloni et al., Citation2019). During the Covid-19, many of them saw this crisis as an opportunity to test themselves in other jobs, look for opportunities in other organizations instead of deciding to be engaged with the organization with an unpredictable future (Wang, Citation2022). In addition, women also showed a higher level of engagement than men in this study, partly because male employees were significantly more favorable in looking for other jobs when businesses downsized and also faced heavier pressure to earn alternative income to support the family. Interestingly, frontline employees have a low level of engagement compared to those who hold back-office positions. A reasonable explanation for this is related to the job characteristics of frontline employees with high autonomy, flexibility but more pressure of dealing directly with the strict requirements of customers (Baum et al., Citation2020). This makes the relationship between frontline employees and their organization become looser.

5.2. Theoretical and managerial implications

This study suggested that organizational sociological perspectives need to be supplemented in the studies on the antecedents of engagement. The multi-level framework that includes variables at both the organizational and individual levels implies that adjusting the cultural context could bring multiple benefits related to job and organizational engagement in travel agencies. Supported proximal and distal effects of organizational culture on organizational engagement further confirm its essential role in engagement improvement. This study has supported the SET theory by emphasizing the role of cultural environmental factors on engagement. The application of the SET theory needs to be viewed more broadly when the benefits that businesses bring in reciprocal relationships with employees are not only financial benefits but also socio-emotional values that can be demonstrated via organizational culture (Kwon & Kim, Citation2020). Secondly, the mediating role of job engagement also allows for changing the view of two distinct dimensions of engagement. While job engagement needs to be considered as a starting point for further research on improving engagement, organizational engagement needs to be given proper attention in the tourism and travel industry. This study has shown that the SET theory is relevant to comprehensively explain how to simultaneously promote job and organizational engagement through organizational culture. Thirdly, it is necessary to recognize the problems of travel businesses with the diversity in the level of engagement and the important influences that come from distinct cultural features.

For managers of travel agencies who are facing a decline in the engagement of staff, developing organizational culture is a viable way to create profound and enduring changes in employee engagement. When setting up the corporate culture manual, with the restriction of the manager’s effort and resource constraints, the managers should give priority to the cultural dimensions that help to achieve dual objectives of improving both job and organizational engagement, including Innovation, Formality, Employee development, and Social Responsibility. Specifically, building a creative working environment, accepting risks, respecting employee voice, and always upholding the interests of the community and environment in all business programs should be prioritized. In addition, the cultural dimension of employee development with support through training activities and career development should be promoted to help individuals’ values align with corporate values, thereby making them more engaged in the workplace (Anitha, Citation2014). Moreover, in a risky environment, travel agencies should pay attention to Social Responsibility to show employees the concern of the organization, so that employees will accompany the enterprise to overcome difficulties (Kim & Kim, Citation2021). In addition, the data analysis results showed that Formality has not properly been promoted in travel businesses in Vietnam while this dimension has a significant influence on both dimensions of engagement. Therefore, this cultural dimension needs to be promoted through strengthening the organizational structure with a detailed system of rules and regulations associated with each employee’s daily tasks and responsibilities. Finally, the remaining cultural factors also need to be developed because job engagement formed by a suitable cultural environment could also lead to organizational engagement among employees in travel agencies.

Additionally, managers in travel agencies should also distribute different concerns for each group of employees, especially turn more attention to Generation Z in the workforce and frontline employees, who play a vital role in determining service quality, resilience and rapid growth after the pandemic, but have a remarkable low level of engagement. The discussions, ongoing training courses aimed at raising awareness of the importance of engagement, chain of engagement activities for remote staff should be deployed based on the flexible use of formal and informal internal communication.

In order for the study’s implications to be truly meaningful and suggestive for further research, some limitations need to be acknowledged. This study focuses on organizational culture that fundamentally shapes employees’ attitudes and behaviors. Future studies should continue to exploit the employee-organization relationship based on the SET theory, especially studies on important contextual antecedents of individual and organizational outcomes. Expanding the research scope to include other developing countries or conducting comparative studies with developed countries could also unfold interesting results. In addition, due to the complexity of the topic of organizational culture and employee psychology, further research could be extended to other groups of multinational travel agencies or cross-border travel services to look for outstanding features of organizational culture and employee engagement in an intercultural environment. Besides, this study was based mainly on survey data to test the influence of organizational culture on employee engagement. However, these are all multi-dimensional constructs, so the addition of qualitative data such as in-depth interviews or case studies could allow for a deeper interpretation of the research results.

6. Conclusions

The COVID-19 crisis has not only completely altered the operations of travel agencies, but also posed a big challenge in attracting and retaining human resources who are engaged and make more efforts for the organization to quickly recover and adapt to the new business landscape. The journey to find solutions to promote employee engagement has provided a remarkable hint for both researchers and practitioners about another significance of developing organizational culture, in addition to its role as a tool to improve competitiveness. This study proposed an analytical framework that synthesizes the relationships between organizational culture and employee engagement. Data collected from 338 employees at travel agencies in Hanoi, the tourism center of Vietnam, provided insight into the impact of the cultural environment on organizational engagement and the mediating role of job engagement in this relationship. The results not only contribute to the engagement literature with a detailed perspective from the travel industry in a developing country during the pandemic, but also suggests solutions for managers in establishing a list of cultural dimensions that need to be prioritized in order to improve employee engagement. Accordingly, enhancing organizational engagement needs to come from developing organizational culture to facilitate the employee’s working process at the workplace, providing meaningful work experiences, thereby creating the premise of forming and strengthening the engagement with the organization.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahmadi, A. A., Ahmadi, F., & Abbaspalangi, J. (2012). Talent management and succession planning. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 4(1), 213–23.

- Alam, I., Singh, J. S. K., Islam, M. U., & Abbas, M. (2021). Does supportive supervisor complements the effect of ethical leadership on employee engagement? Cogent Business & Management, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1978371

- Albrecht, S., Breidahl, E., & Marty, A. (2018). Organizational resources, organizational engagement climate, and employee engagement. Career Development International, 23(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-04-2017-0064

- Alfes, K., Shantz, A. D., Truss, C., & Soane, E. C. (2013). The link between perceived human resource management practices, engagement and employee behavior: A moderated mediation model. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(2), 330–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.679950

- AlShehhi, N., AlZaabi, F., Alnahhal, M., Sakhrieh, A., Tabash, M. I., & Ratajczak-Mrozek, M. (2021). The effect of organizational culture on the performance of UAE organizations. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1980934

- Anaza, N. A., Nowlin, E. L., & Wu, G. J. (2016). Staying engaged on the job: The role of emotional labor, job resources, and customer orientation. European Journal of Marketing, 50(7/8), 1470–1492. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-11-2014-0682

- Anitha, J. (2014). Determinants of employee engagement and their impact on employee performance. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 63(3), 308–323. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-01-2013-0008

- Aslam, M. Z., Nor, M. N. M., Omar, S., Bustaman, H. A., & Foroudi, P. (2020). Predicting proactive service performance: The role of employee engagement and positive emotional labor among frontline hospitality employees. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1771117. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1771117

- Atadil, H. A., & Green, A. J. (2021). An analysis of attitudes towards management during culture shifts. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, 102699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102439

- Bailey, C., Madden, A., Alfes, K., & Fletcher, L. (2017). The meaning, antecedents and outcomes of employee engagement: A narrative synthesis. International Journal of Management Reviews, 19(1), 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12077

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International, 13(3), 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430810870476

- Barba-Sanchez, V., Gouveia-Rodrigues, R., & Meseguer Martinez, A. (2022). Information and communication technology (ICT) skills and job satisfaction of primary education teachers in the context of Covid-19. Theoretical model. Profesional de la información, 31(6), 1–16.s. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2022.nov.17

- Barrick, M. R., Thurgood, G. R., Smith, T. A., & Courtright, S. H. (2015). Collective organizational engagement: Linking motivational antecedents, strategic implementation, and firm performance. Academy of Management Journal, 58(1), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0227

- Baum, T., Solnet, D., Robinson, R., & Mooney, S. K. (2020). Tourism employment paradoxes, 1946-2095: A perspective article. Tourism Review, 75(1), 252–255. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-05-2019-0188

- Bavik, A. (2016). Developing a new hospitality industry organizational culture scale. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 58, 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.07.005

- Bendak, S., Shikhli, A. M., Abdel-Razek, R. H., & Ardito, L. (2020). How changing organizational culture can enhance innovation: Development of the innovative culture enhancement framework. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1712125. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1712125

- Bhardwaj, B., & Kalia, N. (2021). Contextual and task performance: Role of employee engagement and organizational culture in hospitality industry. Vilakshan - XIMB Journal of Management, 18(2), 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1108/XJM-08-2020-0089

- Bradley, R. V., Pridmore, J. L., & Byrd, T. A. (2006). Information systems success in the context of different corporate cultural types: An empirical investigation. Journal of Management Information Systems, 23(2), 267–294. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222230211

- Brown, K. M. (2006). Reconciling moral and legal collective entitlement: Implications for community-based land re- form. Land Use Policy, 24(4), 633–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2006.02.004

- Cardon, P. W., Feng, M., Ma, H., & Ma, Q. (2021). Employee voice, communication formality, and employee engagement: Is there a new normal for internal communication in China? Business Communication Research and Practice, 4(2), 82–91. https://doi.org/10.22682/bcrp.2021.4.2.82

- Chittiprolu, V., Singh, S., Bellamkonda, R. S., & Vanka, S. (2021). A text mining analysis of online reviews of Indian hotel employees. Anatolia, 32(2), 232–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2020.1856157

- Choy, M. W. C., & Kamoche, K. (2021). Identifying stabilizing and destabilizing factors of job change: A qualitative study of employee retention in the Hong Kong travel agency industry. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(10), 1375–1388. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1792853

- Christian, M. S., Garza, A. S., & Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 89–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01203.x

- Cooper, B., Eva, N., Fazlelahi, F. Z., Newman, A., Lee, A., & Obschonka, M. (2020). Addressing common method variance and endogeneity in vocational behavior research: A review of the literature and suggestions for future research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 121, 103472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103472

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

- Dawson, M., Abbott, J., & Shoemaker, S. (2011). The hospitality culture scale: A measure organizational culture and personal attributes. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(2), 290–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.10.002

- Devi, R. V. (2009). Employee engagement is a two-way street. Human Resource Management International Digest, 17(2), 3–4. https://doi.org/10.1108/09670730910940186

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Frenking, S. (2016). Feel good management as valuable tool to shape workplace culture and drive employee happiness. Strategic HR Review, 15(1), 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/SHR-11-2015-0091

- Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3192–3198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.008

- Gabel-Shemueli, R., Westman, M., Chen, S., & Bahamonde, D. (2019). Does cultural intelligence increase work engagement? The role of idiocentrism-allocentrism and organizational culture in MNCs. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 26(1), 46–66. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-10-2017-0126

- Gonzalez-González, T., & García-Almeida, D. J. (2021). Frontline employee-driven innovation through suggestions in hospitality firms: The role of the employee’s creativity, knowledge, and motivation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102877

- GSO- GENERAL STATISTICS OFFICE of Vietnam. (2021). Vietnam Tourism 2021: Needs Determination and Effort to Overcome Difficulties, Retrieved May 2, 2023, https://www.gso.gov.vn/en/data-and-statistics/2021/03/vietnam-tourism-2021-needs-determination-and-effort-to-overcome-difficulties/

- Guest, D. (2014). Employee engagement: A sceptical analysis. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People & Performance, 1(2), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-04-2014-0017

- Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2015). The value of corporate culture. Journal of Financial Economics, 117(1), 60–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2014.05.010

- Gustafson, P. (2012). Managing business travel: Developments and dilemmas in corporate travel management. Tourism Management, 33(2), 276–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.03.006

- Gyensare, M., Arthur, R., Twumasi, E., Agyapong, J.-A., & Ratajczak-Mrozek, M. (2019). Leader effectiveness – the missing link in the relationship between employee voice and engagement. Cogent Business & Management, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1634910

- Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., & Anderson, R.E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th Ed). Pearson, New York.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th Ed.). Pearson Education, Upper Saddle River.

- Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Wheeler, A. R. (2008). The relative roles of engagement and embeddedness in predicting job performance and intention to leave. Work & Stress, 22(3), 242–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802383962

- Harter, J. (2020). Employee Engagement Continues Historic Rise Amid Coronavirus. Gallup. Retrieved March 11, 2022 https://www.gallup.com/workplace/311561/employee-engagement-continues-historic-rise-amid-coronavirus.aspx

- Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., & Hayes, T. L. (2002). Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 268–279. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.268

- Hassanein, F., & Özgit, H. (2022). Sustaining human resources through talent management strategies and employee engagement in the middle east hotel industry. Sustainability, 14(22), 15365. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215365

- HTD – Hanoi Tourism Department. (2022). Statistics of Travel Businesses, Retrieved March 15, 2022 https://tourism.hanoi.gov.vn/

- Huhtala, M., Tolvanen, A., Mauno, S., & Feldt, T. (2015). The associations between ethical organizational culture, burnout and engagement: A multilevel study. Journal of Business Psychology, 30(2), 399–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-014-9369-2

- Hu, B., Liu, J., & Zhang, X. (2020). The impact of employees’ perceived CSR on customer orientation: An integrated perspective of generalized exchange and social identity theory. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(7), 2345–2364. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2019-0822

- Jia, K., Zhu, T., Zhang, W., Rasool, S. F., Asghar, A., & Chin, T. (2022). The linkage between ethical leadership, well-being, work engagement, and innovative work behavior: The empirical evidence from the higher education sector of China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5414. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095414

- Jibril, I. A., & Yesiltas, M. (2022). Employee satisfaction, talent management practices and sustainable competitive advantage in the Northern Cyprus hotel industry. Sustainability, 14(12), 7082. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127082

- Jordan, P. J., & Troth, A. C. (2020). Common method bias in applied settings: The dilemma of researching in organizations. Australian Journal of Management, 45(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896219871976

- Jung, T., Scott, T., Davies, H. T. O., Bower, P., Whalley, D., McNally, R., & Mannion, R. (2009). Instruments for exploring organizational culture: A review of the literature. Public Administration Review, 69(6), 1087–1096. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2009.02066.x

- Justwan, F., Bakker, R., & Berejikian, J. D. (2018). Measuring social trust and trusting the measure. The Social Science Journal, 55(2), 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2017.10.001

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. https://doi.org/10.2307/256287

- Khodakarami, N., & Dirani, K. (2020). Drivers of employee engagement: Differences by work area and gender. Industrial and Commercial Training, 52(1), 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-06-2019-0060

- Kim, M., & Kim, J. (2021). Corporate social responsibility, employee engagement, well-being and the task performance of frontline employees. Management Decision, 59(8), 2040–2056. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-03-2020-0268

- Kundu, S. C., & Lata, K. (2017). Effects of supportive work environment on employee retention: Mediating role of organizational engagement. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 25(4), 703–722. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-12-2016-1100

- Kwon, K., & Kim, T. (2020). An integrative literature review of employee engagement and innovative behavior: Revisiting the JD-R model. Human Resource Management Review, 30(2), 100704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100704

- Latta, G. F. (2020). A complexity analysis of organizational culture, leadership and engagement: Integration, differentiation and fragmentation. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 23(3), 274–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2018.1562095

- Lesener, T., Gusy, B., Jochmann, A., & Wolter, C. (2020). The drivers of work engagement: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal evidence. Work & Stress, 34(3), 259–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2019.1686440

- Levinson, E. (2007). Developing High Employee Engagement Makes Good Business Sense. Retrieved March 15, 2022, www.interactionassociates.com/ideas/2007/05/developinghighemployeeengagementmakesgoodbusinesssense.php

- Lockwood, N. R. (2007). Leveraging employee engagement for competitive advantage: HR’s strategic role. HR Magazine, 52(3), 1–11.

- Malinen, S., & Harju, L. (2017). Volunteer engagement: Exploring the distinction between job and organizational engagement. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary & Nonprofit Organizations, 28(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9823-z

- Maloni, M., Hiatt, M. S., & Campbell, S. (2019). Understanding the work values of Gen Z business students. The International Journal of Management Education, 17(3), 100320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2019.100320

- May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 77(1), 11–37. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317904322915892

- McKinsey&Company. (2021) . Tourism innovation: How Vietnam can accelerate recovery. McKinsey Global Publishing.

- Meng, J., & Berger, B. K. (2019). The impact of organizational culture and leadership performance on PR professionals’ job satisfaction: Testing the joint mediating effects of engagement and trust. Public Relations Review, 45(1), 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.11.002

- Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

- Mgammal, M. H., Al-Matari, E. M., & Bardai, B. (2022). How coronavirus (COVID-19). pandemic thought concern affects employees’ work performance: Evidence from real time survey. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2064707

- Naqshbandi, M. M., Kaur, S., & Ma, P. (2015). What organizational culture types enable and retard open innovation? Quality and Quantity, 49(5), 2123–2144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-014-0097-5

- Ogueyungbo, O. O., Chinonye, L. M., Igbinoba, E., Salau, O., Falola, H., Olokundun, M., & Foroudi, P. (2020). Organisational learning and employee engagement: The mediating role of supervisory support. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1816419. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1816419

- O’Reilly, C. A., & Chatman, J. A. (1996). Culture as social control: Corporation, cults, and commitment. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior (Vol. 18, pp. 157–200). JAI Press.

- Oriade, A., Osinaike, A., Aduhene, K., & Wang, Y. (2021). Sustainability awareness, management practices and organisational culture in hotels: Evidence from developing countries. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, 102699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102699

- Parker, C., Scott, S., & Geddes, A. (2019). Snowball Sampling. In P. Atkinson, S. Delamont, A. Cernat, J. W. Sakshaug, & R. A. Williams, (Eds.), SAGE Research methods foundations. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526421036831710

- Peterson, R. R., & DiPietro, R. B. (2021). Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the perceptions and sentiments of tourism employees: Evidence from a small island tourism economy in the Caribbean. International Hospitality Review, 35(2), 156–170. https://doi.org/10.1108/IHR-10-2020-0063

- Phan, A. C., Le, A. T. T., Nguyen, H. T., & Nguyen, H. (2023). Determinants of employee performance in tourism industry – mediating role of engagement and meaningfulness. International Journal of Productivity and Quality Management, 38(2), 243–269. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPQM.2023.129606

- Phan, A. C., Le, A. T. T., Nguyen, H. T., & Nguyen, H. (2023). Determinants of employee performance in tourism industry – mediating role of engagement and meaningfulness. International Journal of Productivity and Quality Management, 38(2), 243. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPQM.2023.129606/

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Pompurová, K., Sebova, Ľ., & Scholz, P. (2022). Reimagining the tour operator industry in the post-pandemic period: Is the platform economy a cure or a poison? Cogent Business & Management, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2034400