Abstract

We explore the socially responsible investment practices and implementation approaches of some extractive listed firms through the lens of institutional theory. Using an interpretive case study approach with data collected from interviews, observations, and archival documents, over 10 months, we find that the SRI practices of the firms were in line with the SDGs. Furthermore, we reveal that the case firms’ choice of practices along the SDGs was because of the government’s drive for SRI practices in line with the SDGs. We also observe that the government-dominated case firm used its SRI practices to augment the developmental activities of the government. Finally, we show that alien to literature, a multinational company implements its SRI practices using the global approach, because of the pressure from its parent company. Our empirical findings possess the rigour expected from qualitative research. The empirical findings are credible, dependable, and confirmable. In ensuring credibility, the interviews were recorded. However, detailed notes were taken of the interviewees who refused to be recorded. The transcribed data were resent to the interviewees to ensure what they said was accurately captured. Recruiting qualified assistants to undertake some interviews, providing in-depth descriptions of the research method and the analysis of the findings from both the intra and cross-case perspective ensured that the findings are dependable. Finally, the use of semi-structured interviews where further clarity was sought when needed makes the empirical findings confirmable. Largely, our findings support the institutional theory, albeit with some deviations.

Subject Classification:

Public Interest Statement

Research into the Socially Responsible Investment Practices of firms, especially those in the extractive industry, has become topical and relevant. Even more relevant is this research from the perspective of developing economies. Extant literature on SRI has looked at areas such as challenges faced by firms when implementing, etc. This study aims at looking at the SRI practices and implementation among listed extractive firms in Ghana. To achieve this, the study uses a multiple-interpretive case study with data collected through interviews, observation, and archival data.

1. Introduction

Socially Responsible Investment practices refer to practices of firms that extend beyond the returns given to equity participants (Hasan et al., Citation2021). These practices are a combination of both mandatory and voluntary practices of firms.

In understanding what SRI practices entail, there must be a clear distinction between SRI and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) practices. CSR practices are strictly voluntary practices that firms engage in, whilst SRI practices consist of both voluntary and mandatory practices. Thus, it is not only what the firms of their own volition do for the communities they operate in but also what they are mandated by law to do. Failure of which leads to them being punished. SRI has been severally defined in the literature. The definition of SRI is malleable, since it means different things to different people depending on the situation at stake (Aguilera, Ganapathi, Rupp, & Williams, Citation2007). Although some researchers think it means the same thing as Sustainability Accounting, others believe SRI is akin to ethical investment, sustainability investment, Social and Environmental Reporting (SER) or even CSR (Gray & Laughlin, Citation2012; Renneboog et al., Citation2008). SRI practices are the activities, actions and projects that firms undertake in ensuring that they maintain the enclave they work within and at the same time give financial rewards to the providers of the capital. According to Idemudia (2009) and Idemudia and Ite (Citation2006), CSR and SRI practices mean the same thing. However, this study does not agree with the definition of Idemudia (2009) and Idemudia and Ite (Citation2006) where the two terms are said to be synonymous. This is because while CSR constitutes a responsibility, SRI is an investment.

Firms have varied reasons for their choice of the SRI practices they engage in. For instance, while Kirat (Citation2015) posited that these SRI practices could be a response to the challenges caused by globalization, governance and sustainable development, Henry, Nysten-Haarala, Tulaeva and Tysiachniouk (Citation2016) and Akpan (2006) argued that some firms could choose SRI practices to overcome pressures they receive from governments and host communities. Pham, Do, Doan, Nguyen and Pham (Citation2021) also suggested that when firms want to improve their financial performance, they tend to increase the level of corporate sustainability they engage in. That is, they will pursue whatever SRI practices which will give them legitimacy or mileage with stakeholders.

There is also evidence in the literature that there are numerous practices that firms can engage in. They include practices on environmental, social or community development, economics, health, education, ethics, governance, sports, human rights, accountability, transparency and the like (Kirat, Citation2015). Despite these varied practices available to the firms, there is evidence that a firm’s choice mainly depends on the type of economy and country in which the firm is located. For instance, Idemudia and Ite (Citation2006), Idemudia (2009) and Kirat (Citation2015) suggested that the SRI practices that firms within developing economies engage in have predominantly been on environmental and community development at the expense of other equally important practices.

Literature suggests that firms in the past were skewed towards profit maximization (Friedman, Citation1970). An era where the responsibility of business was profit maximization (Chaffee, Citation2017; McWilliams & Siegel, Citation2001). Managers of firms were profit-oriented and were willing to be fined for neglect of the environment once those fines were just a negligible part of their profits (Friedman, Citation2007). According to Qureshi et al. (Citation2020) and Tan and Zhu (Citation2022) in recent times, environmental consciousness has become a part of organizations’ agenda and these firms’ care for the environment transcends beyond the needs of equity providers.

Earlier studies have suggested that firms focus their SRI practices on the environment, community development, education, welfare, health, and safety (Dobele et al., Citation2014; Hoi et al., Citation2018; Nazir & Islam, Citation2020; Somachandra et al., Citation2022). Firms have varied reasons for their choice of the SRI practices they engage in. For instance, Kirat (Citation2015) posited that these SRI practices could be a response to the challenges caused by globalization, governance and sustainable development, Henry, Nysten-Haarala, Tulaeva and Tysiachniouk (Citation2016). Firms also use their practices or initiatives to create positive impressions in the minds of relevant stakeholders (Orazalin et al., Citation2023) or even use these CSR practices to pursue their socially responsible agenda (Ntim & Soobaroyen, Citation2013).

There are two main approaches that firms use when implementing their SRI practice. They are the global and integrated approaches (Bondy & Starkey, Citation2014). The integrated approach is the approach in which the values, culture, and environment the firms were situated in, are incorporated into the policy formulation stage to enable the actors or stakeholders to express their opinions on what affects them. The global approach is used by MNCs in developing economies. This approach ignores the environment the firm is situated in and only passes down the SRI practices seen as internationally best. The global approach is common among multinational companies (MNCs) in developing economies. According to Bhatia and Makkar (Citation2020), some SRI approaches can be implemented in developing economies, whilst others are not feasible for implementation in developing economies.

One of the world’s most important resources is oil and gas, because of its several uses and the boost it gives to economies. The extractive industry has negative impacts on the environment. And the benefits from the SRI practices engaged in have hardly resulted in better living standards, especially for developing nations (Frynas & Buur, Citation2020). According to the World Bank (2020), approximately 15% of Ghanaians do not have access to electricity, which is a huge challenge in meeting SDG 7 (Sachs et al., Citation2021). Also, El-Horr et al. (Citation2022) argued that despite the strides made in growth by Ghana, there still exist some inequalities on social and environmental fronts and if this is not checked it will lead to high poverty level.

Discussions on SRI practices in developing economies have become topical and a budding area of research. With what has been done, very little is known about the factors that influence the approach firms use in implementing their SRI practices. According to Cudjoe et al. (Citation2019), SRI activities are context-specific. Nwobu et al. (Citation2021) espoused that a lack of close monitoring of the SRI practices of the oil and gas industry had caused harm such as oil spillages on farmlands and in waterbodies.

García‐Rodríguez et al. (Citation2013) reported that the SRI practices of some oil and gas firms in a developing economy had helped to improve and mitigate environmental impacts caused by hydrocarbons and urban waste. Contrarily, Apronti (Citation2017) and Osei-Kojo and Andrews (Citation2020) concluded that the SRI practices of oil and gas firms in Ghana do not improve the welfare of the community members. Inconsistencies in the results of the benefits of SRI practices in developing economies made Berkowitz et al. (Citation2017) conclude that SRI practices within developing economies have painted a bleak picture.

These inconsistencies in SRI practices from the perspective of developing economies lead us to want to conduct in-depth research into the SRI practices of some listed extractive firms in Ghana. Hence, the purpose of this paper is to examine the SRI practices as implementation approaches used by listed extractive firms in Ghana.

Consequently, this paper seeks to make the following contributions to the existing literature. First, the paper will augment the scanty but budding area of research, especially from the perspective of the chosen context. Second, the paper will be a reference point for future studies as most of the world’s deposits in oil and other natural resources are in developing economies. Third, this study is novel and a shift from what is seen in the literature on the challenges or general factors of sustainability.

The remaining parts of the paper include a background, theoretical literature review, research design and empirical results and discussions. The final part presents the summary and conclusions drawn based on the findings of the study.

2. Background

The need to undertake this study in the chosen context was informed by some regulatory, reforms and policy and development issues. First, the government of Ghana’s amendment of the Petroleum Revenue Management Act (Act 893) and the Petroleum Exploration and Production Bills (Act 919) in 2015 and 2016, respectively, to ensure some level of better scrutiny within the extractive industry and ensure the nation benefits from the oil finds in the country.

Second, the constant reminder by the government of Ghana for firms to be socially responsible and work towards the attainment of the 17 UN SDGs. This call by the government is not exclusive to extractive firms but also to the District Assemblies.

Third, statistics on the negative effects of the activities of firms on developing nations including Ghana and their link with climate change. Ghana according to the UNEP Climate Action has had one of the biggest increases in GHG emissions of about 256% since 1990, with 1990 as the baseline year (Crippa et al., Citation2021). Although the negative effects of firms’ activities are a worldwide phenomenon, poor countries are more severely affected by the negative effects (Acemoglu et al., Citation2002). The UNDP suggests that developing economies will suffer about 99% of the casualties of this worldwide phenomenon even though these developing countries contribute only 1% of this harm.

Fourth, the extractive sector of Ghana has historically been contributing towards national growth. Given the economic boom, especially after the commercialisation of the oil and gas industry in 2007. After this discovery, not much attention has been given to this sector beyond the financial returns that are made from it.

According to Besada and Golla (Citation2023), Ghana is among the 10 top mineral-producing countries in Africa. Alongside gold, Ghana is also endowed with deposits of iron ore, limestone, columbite-tantalite, feldspar, quartz and salt, and there are also minor deposits of ilmenite, magnetite and rutile. Annual minerals production: $14,970mn. These extractions are either done by large extractive firms that obtain permits to mine (with its peculiar issues) or by smaller individuals who engage in small-scale artisanal mining activities illegally. These small-scale miners popularly known as galamsey have no regard for SRI practices. Abdulai (Citation2017) suggested that evidence points out that efforts by governments in curbing this menace have mainly been a technocratic approach.

Finally, the oil curse in other developing economies makes this paper timely and apt for the chosen context. The resource curse is the paradox that countries with an abundance of natural resources often fail to grow as rapidly as those without such resources. Thus, the situation whereby a country has an export-driven natural resources sector that generates large revenues for the government but leads paradoxically to economic stagnation and political instability.

Sub-Saharan African countries with natural resources are often found in this situation, in that their economic development lies behind the rest of the world despite their wealth of oil, gas, and minerals (Moti, Citation2019). The SRI practices of the firms need to be thoroughly investigated to understand what direction these firms are moving. Whether Ghana will end up like the others in terms of the oil curse.

3. Theoretical literature review

3.1. Institutional theory

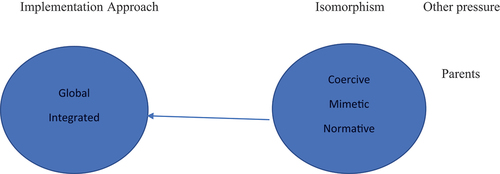

The institutional theory posits that firms are mindful of institutionalized legitimacy. This legitimacy presents itself because of some pressures on those firms. The institutional theory was propounded by Meyer and Rowan (Citation1977) with updates from DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1983) and Scott (Citation2001). This theory explains why firms look similar when viewed on the outside but different within. The process called isomorphism makes firms look similar from the outside (Boxenbaum & Jonsson, Citation2017; DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983) or structures/pillars (Scott, Citation2001). The three isomorphisms are coercive, mimetic, and normative, with regulative, normative, and cognitive being the pillars.

Even though the three pressures affect the practices and approach to implementation, other institutional pressures should be considered (Islam & Deegan, Citation2008; Wooten & Hoffman, Citation2008). Even though the three isomorphisms determine the SRI practices and approach adopted by firms, the peculiar environment firms are situated in is also a relevant pressure (Campbell, Citation2007; Putnam Rankin, Citation2021). The field or industry of a firm determines the SRI practices and approach for implementations (Beschorner & Hajduk, Citation2017; Dabic et al., Citation2016; Jamali & Neville, Citation2011; Jamali et al., Citation2020) and by extension, the isomorphism at play.

The effects of these pressures are context-specific. When there is a relatively healthy economic environment and the existence of strong and well-enforced state regulations or private independent organisations or strong normative calls for such behaviour, firms will engage in and implement these SRI practices, compared to when it is not prevalent (Matten & Moon, Citation2008). Firms whether in developed or developing economies show a varied level of responses to these pressures (Alazzani & Wan-Hussin, Citation2013; Li & Lu, Citation2020). With SRI practices, Comyns and Figge (Citation2015) also posited that when SRI practices are being considered, the most important isomorphism is the strict regulation from the government as a guide for the activities of firms.

Some of the studies that used the institutional theory, and their outcomes are discussed.

Wooten and Hoffman (Citation2008) and Azizul Islam and Deegan (Citation2008) for instance argued that firms faced the three pressures or isomorphism when engaging in SRI practices. They asserted that a firm’s engagement in SRI practices was solely not because of the pressures from these three institutional groups (that is as a form of reaction to the actions in the form of pressures). These researchers also believed that in addition to the pressures that these firms face when engaging in their SRI practices, there should also be an effective institutional environment which their study left out. In sum, they realised that pressures on the firms alone are not enough to make firms engage in SRI practices.

Using the institutional theory to explain the SRI practices of firms, Li and Lu (Citation2020) argued that the different institutional environments influence differently the kind of pressures the firm will face. They argued that these pressures could affect the SRI practices the firms engage in. However, they agreed that the economic environment that firms operate in is a major determinant of whether these firms will be moved by the pressures. In other words, the three isomorphisms that encourage firms to engage in SRI will only be possible if the economic environment these firms work in is a favourable one.

Jamali and Neville (Citation2011) used the institutional theory to explain CSR practices and their subsequent implementation (within the firms). They argued that firms find themselves within a certain organisational field and this organisational field in turn affects the three isomorphisms. They asserted that these isomorphisms affect firms differently based on the political, cultural, educational, labour and financial systems and that not all three isomorphisms affect a firm at the same time. In other words, whereas some firms will be pressured by only one isomorphism, others will be pressured by two. The researchers also argued that with the case firms studied, only the mimetic pressure was prevalent.

Matten and Moon (Citation2008) also observed that in using the institutional theory to explain why firms engage in SRI practices, they realised that when there is a relatively healthy economic environment, the existence of strong and well-enforced state regulations, private independent organisations and strong normative calls for such behaviour, firms will engage in and implement these SRI practices. These support the idea that not all isomorphisms apply in all cases because only coercive and normative isomorphisms were present (Matten & Moon, Citation2008).

Alazzani and Wan-Hussin (Citation2013) however argued that firms whether in developed or developing economies would show varying levels of responses to the three isomorphisms based on the level of commitment these pressures exert on environmental issues. Comyns and Figge (Citation2015) also posited that when SRI practices are being considered, the most important isomorphism is the strict regulation from the government as a guide for the activities of firms. In a related study Raufflet, Cruz and Bres (Citation2014) realised that firms within the mining, oil and gas industries operate under different institutional contexts depending on whether these firms are found in the developed or the developing economies. Thus, the differences in the economy between the developed and developing economies will determine the pressures and the importance of these pressures on the firm.

The use of the institutional theory in the studies above makes it apt for this research based on the following reasons. First, the unique ownership characteristics (mostly foreign-dominated) of the listed firms in Ghana. These foreign-dominated firms have their parents mostly in different developed economies outside Ghana, thus the economic, cultural, social, political and financial environments are different. Which isomorphism will be most relevant to foreign or government-dominated firms? According to Frynas and Yamahaki (Citation2016), foreign MNCs are faced with a lot of competing and sometimes conflicting institutional pressures and these MNCs may disregard the SRI practices or change the institutional environment.

4. Empirical literature

4.1. SRI practices and implementation

A review of the literature on SRI demonstrates that there are a couple of areas or practices that firms have implemented over the years. These are practices on environmental stewardship, community development, education, welfare, health and safety (Dobele et al., Citation2014). Amaeshi et al. (Citation2006) suggested that not all practices were feasible to be implemented in developing economies. However, firms within developing economies are seen implementing practices that address the socio-economic challenges of the government (e.g., poverty alleviation, health-care provision, infrastructure development, education, etc.). This is entirely different from the Western standard or expectations of SRI, e.g., consumer protection, fair trade, green marketing, climate change concerns, socially responsible investments, etc. (Dobele et al., Citation2013; Amaeshi et al., Citation2006).

Firms within developing economies are also seen to engage in practices that will equally bring the utmost benefits so far as they do not fall foul of any law. They are thus seen to be very subjective through and through once it keeps them in the good books of the communities (Kirat, Citation2015), having in mind the negative effects these extractive firms have on communities (Mbilima, Citation2021).

This paper highlights how literature has used the two approaches for implementation of SRI practices and the areas on which firms concentrated. Although literature argues that firms face context-specific factors that inhibit them from effectively implementing their chosen SRI practices, evidence in extant literature highlighted broad external factors. This is relevant as it seeks to properly situate the approaches used by the firms in this study on what literature emphasizes to be able to spot deviations. The studies on SRI implementation within oil and gas firms found that there are two main approaches used by firms when implementing SRI.

Dobele et al. (Citation2013) gave evidence of how an MNC's choice of the global approach (with no heed to the desires and demands of the local stakeholders but rather took orders from their foreign parents although, at the earlier stages, the firm was in contact with the community and this) led to conflicts.

With the implementation of SRI practices, Graafland and Zhang (Citation2014), observed that in some developing economies, local firms were disadvantaged compared to their MNC competitors. As a result, the government influenced and supported local firms intending to encourage them to get to the level of the MNCs. Although these local firms had support from the government, very little was achieved due to some factors that inhibited their progress. This pointed to the idea that in keeping up with the standards of their foreign counterparts, the practices they engaged in were imported from the West, and they did suit the conditions in the developing economies (Fatima & Elbanna, Citation2023; Frynas, Citation2005; Graafland & Zhang, Citation2014).

Frederiksen (Citation2019) found out that CSR practices impact Zambia’s metal mining sector. These firms or sectors featured received very little attention on the national level, compared to the local level. This research also found that CSR practices of the case firms influence the governance of extraction and the possibility of inclusive development, with notable consequences for institutions of traditional leadership.

From the review of the literature above, it was realized that the SRI practices of firms were determined by the kind of economy these firms were situated in and that no two firms in two different developing economies are the same, and if the approach implemented does not sit well with stakeholders, it leads to conflicts. The gaps seen in the literature thus make a case for this current study.

Jnr et al. (Citation2021)’s study concluded that in Ghana, companies’ internal policies and objectives lead them to engage in these practices and that these practices were mainly social intervention practices, such as education, provision of portable water, roads and the like. Most SRI practices in developing economies are related to social, ethical, and environmental issues (Amos, Citation2018b). With SRI practices in the mining sector of Ghana are linked to community involvement, work ethics, environment, health/safety and

welfare of employees/communities, respect for the law, and financial sustainability (Amos, Citation2018a). Apart from the internal policy and objective reasons for these practices by firms in Ghana, Dartey-Baah and Amponsah Tawiah (Citation2011) suggested that the concerns raised by governments and other policymakers’ and firms’ appetite to be portrayed as ethical and socially responsible have compelled firms to engage in these SRI practices. Or even use these practices to contribute towards economic, social and environmental sustainability (Amponsah-Tawiah & Dartey-Baah, Citation2016).

4.2. Implementation of SRI practices

In this section, the researcher highlights how literature has used the two approaches for implementation of SRI practices and the areas the firms concentrated on. Although literature argues that firms face context-specific factors that inhibit them from effectively implementing their chosen SRI practices, evidence in extant literature highlighted broad external factors. This is relevant as it seeks to understand what the literature says about the two approaches to properly situate the approaches used by the firms in this study on what literature says to spot deviations.

The studies on SRI implementation within oil and gas firms found that there are two main approaches used by firms when implementing SRI. These are the global and integrated approaches (Bondy & Starkey, Citation2014). Bartlett and Ghoshal (Citation1998) and Harzing (Citation2000), however, identified the use of three approaches. They are multi-domestic, global, and integrated or transnational. These three approaches feed into the two main approaches. With the integrated approach, the values, culture, and environment in which the firms were situated, were incorporated into the policy formulation stage to enable the actors or stakeholders to express their opinions on what affects them. The global approach which is seen to be rather popular, especially among MNCs accommodated few or no stakeholder engagements. In other words, this global approach ignores the local factors but only takes into consideration globally recognised best approaches. This practice which is identified as the best is imposed on and implemented by all subsidiary firms. While the integrated approach incorporates home or national cultures into the process, the global approach ignores local factors and only takes into consideration globally recognised processes.

Although it can be seen from the above that there is the need to satisfy all relevant stakeholders if the firm wants to avoid conflicts and clashes, especially with communities they operate in, Maon, Lindgreen and Swaen (Citation2009), however, contended that the idea of satisfying stakeholders might not necessarily apply to all environments. This study, however, failed to test which situations stakeholders need to be taken seriously but rather suggested that it would be imperative for future studies to develop frameworks that are comprehensive enough to accommodate the context of the firms in the implementation of these SRI practices.

In another example, Dobele, Westberg, Steel and Flowers (Citation2013) gave evidence on how an MNC’s choice of the global approach ignored the desires and demands of the local stakeholders but rather took orders from their foreign parents although, at the earlier stages, the firm was in contact with the community, and this led to conflicts. Even though the firm’s Head Office felt they had put the best practices in place to manage the impact of their activities on the environment, the stakeholders on the contrary felt these practices did not work well. However, after the firm modified its strategy by bringing its physical presence into the community through proper stakeholder engagements, the conflicts were minimised. This shows that the global approach used by MNCs in developing economies leads to avoidable conflicts when implemented. The conclusion that the implementation of SRI practices by MNCs leads to conflicts is also reiterated by the study of Idemudia and Ite (Citation2006). They found out that conflicts always occurred between the MNCs and communities because these communities felt their issues and concerns were overlooked by the MNCs. Thus, to avoid conflicts from the implementation of the SRI practices of firms, certain factors need to be critically looked at. These include the proper identification and prioritization of influential stakeholders, the identification of the relationship between the firms’ stakeholders, the need for internal commitment of management and employees to SRI and the appointment of an SRI Champion. There is also the need for a local presence to facilitate community engagement, provide feedback and monitor economic activities. But the imperative is to build trust and social legitimacy within the local community. Failure to consider these factors will always result in conflicts with peeved stakeholders, especially community members.

About the nature of SRI practices, the literature suggests that there are a couple of areas or practices firms have implemented over the years. These are practices on environmental stewardship, community development, education, welfare, health, and safety (Dobele et al., 2013). Amaeshi et al. (Citation2006) suggested that not all the practices were feasible, especially in developing economies. Practices on employee welfare were not feasible in Nigeria because a private company could terminate the employment of its employees at will and for no reason after issuing a month’s notice by statute and usually 3 months by contract. However, the firms within developing economies are seen to implement practices that address the socio-economic challenges of the government (e.g., poverty alleviation, health-care provision, infrastructure development, education, etc.). This is entirely different from the Western standard or expectations of SRI e.g., consumer protection, fair trade, green marketing, climate change concerns, socially responsible investments, etc. (Dobele et al., 2013; Amaeshi et al., Citation2006). Firms within developing economies are also seen to engage in practices that will equally bring the utmost benefits so far as they do not fall foul of any law. They are thus seen to be very subjective across the board once it keeps them in the good books of the communities (Kirat, Citation2015). So, if a firm engages in only health-related practices, so long as they obtain the utmost benefits from it, it is fine by them.

With the implementation of SRI practices, Graafland and Zhang (Citation2014) observed that in some developing economies, local firms were disadvantaged compared to their MNC competitors. As a result, the government influenced and supported local firms to encourage them to get to the level of the MNCs. Although these local firms had support from the government, very little was achieved due to certain factors that inhibited their progress. This pointed to the idea that in keeping up with the standards of their foreign counterparts, practices they engaged in were imported from the West, and they did not suit the conditions in the developing economies (Frynas, Citation2005; Graafland & Zhang, Citation2014).

Rahaman, Lawrence and Roper (Citation2004) realised that in Ghana, in the case of a public sector institution (the Volta River Authority (VRA)), the firm implemented SRI practices not because it wanted to but because it was compelled by its foreign donor agencies. Although the pressures from the government were in play as well, the greatest pressure was from the foreign donors because of the provision of funds. This study, however, failed to discuss whether these SRI practices were relevant in Ghana at the time they were implemented or whether they were merely implemented at the request of the donors, thus its relevance was not considered.

From the review of the literature above, it was realised that the SRI practices of firms were determined by the kind of economy these firms were situated in. No two firms in two different developing economies are the same, and if the approach implemented does not sit well with stakeholders, it leads to conflicts. The gaps seen in the literature thus make a case for this current study.

5. Research design

The appropriate research design for the gaps identified by this study is the qualitative research design with the interpretive case study, the most appropriate method.

The interpretive case study was the most appropriate method because it will provide concrete, contextual, and in-depth knowledge about the practices and implementation approaches engaged by the case firms. Case studies provide the researcher with an opportunity to gain an in-depth holistic view of a research problem as well as help in describing, understanding, and explaining a research problem or situation.

Once the interpretive case study was settled on as the appropriate method, the researchers had to decide on selecting the firms that formed the cases.

5.1. Selection criteria

We started by looking at firms that were first classified as extractive firms and listed on the GSE.

The next consideration was whether the firms identified above engaged in any SRI practices.

The access to data and theoretical interest of the researchers also played a key role.

Using the criteria above, three firms were ultimately selected to form the cases.

For confidentiality and ethical reasons, they are anonymously called Firm Alpha, Firm Beta and Firm Gamma.

5.2. Profile of case firms

5.2.1. Firm Alpha (Firm A)

Firm Alpha was initially founded as a private company in the early 1960s to deal with oil and gas products such as fuels, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), lubricants, bitumen and other petroleum products in Ghana. In the early 1970s, the Government of Ghana acquired the shares of the smaller shareholders leaving the ownership of this firm in the hands of only two shareholders, namely the government of Ghana and another shareholder. Firm Alpha is a publicly listed company that was listed on the Ghana Stock Exchange in 2007. Although it is a listed firm, the government and its quasi-institutions appoint almost all the members of the board.

5.2.2. Firm Beta (Firm B)

Firm Beta forms part of a multinational company with a presence in over 130 countries in the world. Its operation in Ghana started in the early 1960s and it was listed on the GSE in 1991 under a different name from what it uses currently. It is a world-class oil, gas and chemicals group with industrial and commercial operations spanning oil, gas, power generation, renewable energies and chemicals. This firm was part of the cases because it has achieved a lot regarding SRI practices within the industry. It has won several awards in the oil and gas sector CIMG Hall of Fame for CSR Practices, staff development and new business development.

5.2.3. Firm Gamma (Firm G)

Firm Gamma is a multinational company that is present in almost all the continents in the world. In Ghana, it is the only firm currently involved in the actual drilling of oil (upstream) as the others have just begun with the process of a permit for drilling. Firm Gamma was listed on the Ghana Stock Exchange in 2011 after going through all the necessary processes for drilling oil. In as much as the Annual Reports do not in any place explicitly state the firm’s engagements in SRI, some sections within the Report showed the firms’ engagement in SRI.

5.3. Data collection

Data were collected from interviews, observations, and archival documents.

5.4. Interviews

Once the three cases were selected, the researchers had to decide who the interviewees were. In all three firms, the gatekeepers who were lower-ranked staff introduced us to our first interviewees. Once the first interviewees were identified, through snowballing, the other interviewees were reached.

The number of interviewees was not predetermined. The number of interviewees depended on the number of staff in the SRI department and on the saturation level.

The interviews were semi-structured. The interviews were conducted from September 2019 to December 2019 and April 2022 to September 2022. The break in time was because of the insurgence of Covid-19. Forty interviews were conducted with fourteen (14) individuals (6, 4,2, and 2) from Firms Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and the Regulators, respectively. Pseudonyms were used to represent both the firm and the interviewees to ensure their identities are protected. For instance, in Firm Alpha, the researcher used FAM1 for the 1st interviewee in Firm Alpha, etc. Details of the interviewees can be found in the Appendices.

5.5. Observations

The researchers observed the work environment and behaviours of the interviewees in their natural environment. Observation is another primary source of gathering data.

5.5.1. Archival documents

The annual reports of the firms, their websites as well as the websites of the GSE were good sources of gathering data. The profile of the firms was sourced from the annual reports.

The multiple data collection techniques are used to ensure triangulation, complementation, and richness of the data collected.

6. Empirical results and discussions

The empirical results and findings will be discussed along two strands (intra-case and cross-case analyses). The intra-case will look at the findings and peculiarities of individual case firms. The cross-case analysis will bring out the difference and similarities among the three case firms linking them to theory and empirical literature.

6.1. Intra-case analysis

6.1.1. Firm Alpha

The findings of this research reveal that Firm Alpha’s selected SRI practices are mainly in line with the SDGs, with the most recent ones linked to SDGs 6, 4, and 2. This firm implements its SRI practices using the integrated approach.

Find below the implementation process.

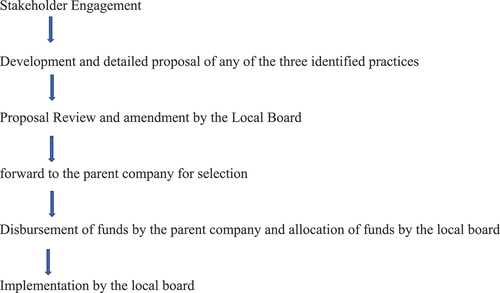

6.1.2. Firm Beta

We found out that Firm Beta’s SRI practices are also in line with the SDGs. This firm, however, uses a global approach in implementing their SRI practices. Below is the implementation process.

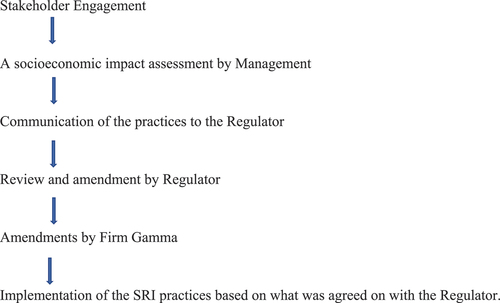

6.1.3. Firm Gamma

Firm Gamma’s SRI practices, like the other two, are in line with the SDGs. The findings of this study also reveal that Firm Gamma implements its SRI practices using an integrated approach. Find below the implementation process.

6.3. SRI implementation approaches

The similarities in the SRI practices of the firms are channelled towards community development in line with the SDGs. They are formalised and well-documented as well. This study asserts that it is so because these firms are abreast of changing trends and the passionate appeal by the government after the SDGs were launched. This research suspects that this is so because although these three firms operate under different scopes (local vs. foreign: upstream vs. downstream), they are mindful of how the international communities view them and whether their implementation of SRI practices would be accepted by all the staff (they want the full acceptance and cooperation of their employees).

Firm Beta has no autonomy in its implementation choice and process because it relies on its parent company for some financial assistance in the implementation of its SRI practices and it is therefore forced by the parent company to do what they require by way of their SRI practices. Although they engage in stakeholder engagements, they place a small premium on this stakeholder engagement and rather go by the dictates of the parent. The parent firm is seen to be the most important or dominant pressure on this firm. This is not explained by the three isomorphisms of the institutional theory. The dependence on the parent company for financial assistance in implementing the SRI practices renders the local board of directors who are supposed to take decisions such as the implementation approach and its timing powerless. This shows some level of weakness in the corporate governance system for listed firms although there is a local board, their role seems only ceremonial.

There are some similarities as well as deviations seen in the findings of this study, comparing it to the literature. Just as in the literature on SRI, the government-owned firm uses the integrated approach, while one of the foreign-owned firms uses the global approach. The implementation approach used by the firms is indicative of the importance the firm place on stakeholder engagements (Bondy & Starkey, Citation2014). Firms that place greater importance on stakeholders and their concerns use the integrated approach (Tripathi & Kaur, Citation2022), as the reverse is true for the global approach (Badulescu et al., Citation2018). The firms that are likely to put a higher degree of importance on the stakeholder engagement process, literature documents are the MNCs operating in developing economies (Sun & Xu, Citation2023), and these MNCs use the integrated approach as a mitigating tool for some unforeseen risk including the loss of legitimacy from the developing economies they operate in (Hatane & Soewarno, Citation2022).

The finding that is alien to the literature is how another MNC uses the integrated approach, although there seems to be some stakeholder engagement done by the firm. This suggests that the stakeholder engagement process is a mere formality, with little importance placed on what comes out of this stakeholder engagement. These findings direct us to the idea that firms react differently to different sets of pressures, and these influence the choice of their SRI implementation approach selected (Cudjoe et al., Citation2019; Perez-Batres et al., Citation2012). However, whether an influence is succumbed to be dependent on the type and intensiveness of the stakeholder pressures and whether these stakeholders provide finances. Also, beyond the three isomorphisms, a major source of pressure could be the parent company.

An interesting finding of this research, worthy of extending the theory, is that apart from the lack of coercive isomorphism in the downstream foreign-owned firm, this firm is at the CSR phase because its parent company mandates their practices to be at that phase. This defies the norm seen in the literature for foreign-dominated firms operating in developing economies. From the literature and the predictions of the theoretical framework, one would expect that mimetic pressures or normative pressures would be the dominant isomorphism at play such that even without laws, a foreign MNC would be at the SRI phase based on its membership in international professional bodies or based on the SRI phase of other competitors. This study finds that this MNC is in no way affected by mimetic or normative isomorphism but that the most important pressure on this MNC is pressure from its parent company. Thus, internal legitimacy is more important to this firm than any form of legitimacy. This study concludes that although the institutional theory gives evidence of pressure on firms regarding their SRI practices, it did not mention the parent being a form of pressure or isomorphism on the firm. This finding therefore advances the pressures oil and gas firms face when engaging in SRI but in Ghana, downstream MNCs deal with parent pressures and acceptance, especially when the parent serves as a source of funding or financing for the firm.

In summary, this study argues that whereas the coercive and normative pressures are pressures for the upstream MNC explained by the institutional theory, the downstream MNC pressure comes from the parent and is not explained but rather serves as a suggestion for the build-up of the institutional theory.

6.4. Results from our observations

Apart from the intra and cross-case results and discussions, we observed some discrepancies or conflicts in the behaviours of some of the interviewees of Firm Alpha concerning what they said off the- record and what was said on record regarding how and the extent to which government ownership leads to interference and/or manipulation of SRI within the firm. On record, they seem to unanimously argue that since the firm is a listed firm, it goes by the dictates of the GSE as a regulator. However, some observations included the trooping in of government officials into the top-level Managers’ office as well as off-the-camera complaints of government influence during the interview. Also, in Firm Beta, it was observed that there was a strict Head of department who influences the thoughts and work of his subordinates and is greatly feared by those in his department. No wonder one of the interviewees (FBM1) opted for a meeting outside the office environment. Thirdly, this study observed that across all three firms, apart from those within the SRI department or sector, SRI is not fully and widely accepted within the firms. Hence, others within the other sectors of the firm were mostly clueless about what the SRI department entailed although the interviewees argued that SRI practices are part and parcel of their firm’s practical goals. This research finally observed that what SRI entailed by way of definition, whether it was mandatory or voluntary, was not too different across the three firms. The use of observation has helped in a better understanding of the context. It has also helped in complementing the findings seen from the interview sessions instead of solely relying on the interviews.

7. Summary and conclusion

Owing to the topical nature of SRI practices within the extractive industry and especially from the perspective of a developing economy, and the gaps identified in the literature on the SRI practices of firms, we set out to delve into the SRI practices and the implementation approaches used by the case firms. Through semi-structured interviews and observations, this paper found that: First, the SRI practices of the case firms were in line with the SDGs attributable to the essence of the SDGs to the country as a whole and the firms as individual entities. Second, this study finds that the case firms implement their SRI practices using either the integrated or global approaches but unlike what is seen in the literature, an MNC uses the global approach because of the pressure it receives from its parent firm. This finding suggests that MNC values the relationship it has with its parent firm over any other local relationship. Third, the findings also suggest that for the context being considered, the institutional theory does not fully explain the SRI practices and its implementation approaches, thus a call for the extension of this theory thus an extension of the earlier studies (Dabic et al., Citation2016; Beschorner & Hajduk, Citation2017, Jamali, Jai, Samara & Zoghbi, Citation2020; Wooten & Hoffman, Citation2008; Alazzani & Wan-Hussin, Citation2013; Comyns & Figge, Citation2015)

Our study offers some academic, practical and policy. First, our study will augment the very scanty literature on SRI from the chosen context (CitationNwobu et al., Citation2021). It will be a reference point for future studies as most of the world’s deposits in oil and other natural resources are in developing economies. This study is novel and a shift from what is seen in the literature on the challenges or general factors of sustainability. Further, this paper indicates that theoretically, the Institutional theory needs to be extended. Second, regulators and policymakers need to close the loopholes and develop a proactive system, especially for listed firms. They consider stricter avenues for listed firms to respect all the dictates of the regulator. This will avoid interference from the owners of these listed firms (whether government or foreign owners). Additionally, regulators can consider standardized rules and guidelines on the SRI practices of firms. The findings of the study also contribute to the dialogue on corporate governance and accountability in the extractive industry. It may provide insights into the effectiveness of existing policies and initiatives related to social and environmental responsibility and offer recommendations for improving governance frameworks and reporting requirements.

Finally, managers and firms should know the effect their SRI investment practices contribute towards the livelihood of individuals and should always select and implement practices that benefit society at large.

Our study has some limitations that should be addressed by future research. First, our study’s case firms are skewed and do not fully depict the definition of the extractive industry by United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (Citation2017), which includes oil and gas firms, transport and storage, exploration, development, production, and decommissioning. Although interpretive studies do not aim to generalize, future research should include the other firms that are part of the extractive industry but not part of the study’s case firms. Second, studies on SRI practices are a grey area of research in developing economies (Jamali & Karam, Citation2018). It is an area that is also now emerging in Ghana, this study’s case firms were extractive firms that are listed. There are a lot more unlisted extractive firms in Ghana. This study, therefore, proposes that future studies should look at this research from the unlisted firms’ angle because they are not regulated. If there are loopholes in the activities of the listed firms, how much more are the unlisted ones? Third, the findings indicated the inadequacy of the institutional theory in explaining the SRI practices of a case firm. Future research studies can look at the possibility of grounded research on how the institutional theory can be extended to incorporate into it the aspect of the research not fully explained.

8. Statement of Publication

This article has not been published elsewhere and has not been submitted simultaneously for publication elsewhere.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mawuena Akosua Cudjoe

Mawuena Akosua Cudjoe is a Lecturer in Accounting and Sustainability, at the Department of Accounting, University of Ghana Business School. Her research interest is in Corporate Governance and Sustainability Reporting/Accounting.

Ahmed Razman Abdul Latiff

Ahmed Razman Abdul Latiff is an Associate Professor at the Putra Business School, Universiti Putra Malaysia, and the Head of Non-Thesis Based Programmes at Putra Business School.

Nor Aziah Abu Kasim

Nor Aziah Abu Kasim is a retiree. She was an Associate Professor in Accounting at the Faculty of Economics and Management, Universiti Putra Malaysia.

Mohammad Noor Hisham Osman

Mohammad Noor Hisham Osman is affiliated with the Faculty of Economics and Management, Universiti Putra Malaysia.

References

- Abdulai, A. G. (2017). Competitive clientelism and the political economy of mining in Ghana. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2986754

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2002). Reversal of fortune: Geography and institutions in the making of the modern world income distribution. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4), 1231–21. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355302320935025

- Aguilera, R. V., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 836–863.

- Alazzani, A., & Wan-Hussin, W. N. (2013). Global Reporting Initiative’s environmental reporting: A study of oil and gas companies. Ecological Indicators, 32, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.02.019

- Amaeshi, K., Adi, A. B. C., Ogbechie, C., & Amao, O. O. (2006). Corporate social responsibility in Nigeria: Western mimicry or indigenous influences? Available at SSRN 896500. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.896500

- Amos, G. J. (2018a). Corporate social responsibility in the mining industry: An exploration of host communities perceptions and expectations in a developing country. Corporate Governance the International Journal of Business in Society, 18(6), 1177–1195. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-01-2018-0006

- Amos, G. J. (2018b). Researching corporate social responsibility in developing-countries context: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Law and Management, 60(2), 284–310. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLMA-04-2017-0093

- Amponsah-Tawiah, K., & Dartey-Baah, K. (2016). Corporate social responsibility in Ghana: A sectoral analysis. In S. Vertigans, S. O. Idowu, & R. Schmidpeter (Eds.), Corporate social responsibility in Sub-Saharan Africa: Sustainable development in its embryonic form (pp. 189–216). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26668-8_9

- Apronti, P. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and sustainable community development. A case study of AngloGold Ashanti, Adieyie, and Teberebie, Ghana ( Doctoral dissertation).

- Badulescu, A., Badulescu, D., Saveanu, T., & Hatos, R. (2018). The relationship between firm size and age, and its social responsibility actions—Focus on a developing country (Romania). Sustainability, 10(3), 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030805

- Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Beyond strategic planning to organization learning: Lifeblood of the individualized corporation. Strategy & Leadership, 26(1), 34–39. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb054610

- Berkowitz, H., Bucheli, M., & Dumez, H. (2017). Collectively designing CSR through meta-organizations: A case study of the oil and gas industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 143(4), 753–769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3073-2

- Besada, H., & Golla, T. (2023). Policy impacts on Ghana’s extractive sector: The implicative dominance of gold and the future of oil. The Extractive Industries and Society, 14, 101214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2023.101214

- Beschorner, T., & Hajduk, T. (2017). Responsible practices are culturally embedded: Theoretical considerations on industry-specific corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 143(4), 635–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3405-2

- Bhatia, A., & Makkar, B. (2020). CSR disclosure in developing and developed countries: A comparative study. Journal of Global Responsibility, 11(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGR-04-2019-0043

- Bondy, K., & Starkey, K. (2014). The dilemmas of internationalization: Corporate social responsibility in the multinational corporation. British Journal of Management, 25(1), 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2012.00840.x

- Boxenbaum, E., & Jonsson, S. (2017). Isomorphism, diffusion, and decoupling: Concept evolution and theoretical challenges. The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism, 2, 77–101.

- Campbell, J. L. (2007). Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 946–967. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.25275684

- Chaffee, E. C. (2017). The origins of corporate social responsibility. University of Cincinnati Law Review, 85, 353.

- Comyns, B., & Figge, F. (2015). Greenhouse gas reporting quality in the oil and gas industry: A longitudinal study using the typology of “search”, “experience” and “credence” information. Accounting Auditing & Accountability Journal, 28(3), 403–433. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-10-2013-1498

- Crippa, M., Guizzardi, D., Solazzo, E., Muntean, M., Schaaf, E., Monforti-Ferrario, F., & Vignati, E. (2021). GHG emissions of all world countries. Publications Office of the European Union https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/jrc126363

- Cudjoe, M. A., Abdul Latiff, A. R., Abu Kasim, N. A., Hisham Bin Osman, M. N., & Ntim, C. G. (2019). Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) initiatives in developing economies: Challenges faced by oil and gas firms in Ghana. Cogent Business & Management, 6(1), 1666640. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1666640

- Dabic, M., Colovic, A., Lamotte, O., Painter-Morland, M., & Brozovic, S. (2016). Industry-specific CSR: Analysis of 20 years of research. European Business Review, 28(3), 250–273. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-06-2015-0058

- Dartey-Baah, K., & Amponsah-Tawiah, K. (2011). Exploring the limits of Western corporate social responsibility theories in Africa. International Journal of Business & Social Science, 2(18).

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- Dobele, A. R., Westberg, K., Steel, M., & Flowers, K. (2014). An examination of corporate social responsibility implementation and stakeholder engagement: A case study in the Australian mining industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 23(3), 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1775

- Dobele, A. R., Westberg, K., Steel, M., & Flowers, K. (2014). An examination of corporate social responsibility implementation and stakeholder engagement: A case study in the Australian mining industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 23(3), 145–159.

- El-Horr, J., Pecorari, N. G., Miller, M., Caulker, C. G., & Izevbigie, J. I. (2022). Ghana: Social Sustainability and Inclusion Profile.

- Fatima, T., & Elbanna, S. (2023). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) implementation: A review and a research agenda towards an integrative framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 183(1), 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05047-8

- Frederiksen, T. (2019). Political settlements, the mining industry and corporate social responsibility in developing countries. The Extractive Industries and Society, 6(1), 162–170.

- Friedman, M. (1970). A theoretical framework for monetary analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 78(2), 193–238.

- Friedman, M. (2007). The social responsibility of a business is to increase its profits. In Corporate ethics and corporate governance (pp. 173–178). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-70818-6_14

- Frynas, J. G. (2005). The false developmental promise of corporate social responsibility: Evidence from multinational oil companies. International Affairs, 81(3), 581–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2005.00470.x

- Frynas, J. G., & Buur, L. (2020). The resource curse in Africa: Economic and political effects of anticipating natural resource revenues. The Extractive Industries and Society, 7(4), 1257–1270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2020.05.014

- Frynas, J. G., & Yamahaki, C. (2016). Corporate social responsibility: Review and roadmap of theoretical perspectives. Business Ethics: A European Review, 25(3), 258–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12115

- García‐Rodríguez, F. J., García‐Rodríguez, J. L., Castilla‐Gutiérrez, C., & Major, S. A. (2013). Corporate social responsibility of oil companies in developing countries: From altruism to business strategy. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 20(6), 371–384. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1320

- Graafland, J., & Zhang, L. (2014). Corporate social responsibility in China: Implementation and challenges. Business Ethics: A European Review, 23(1), 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12036

- Gray, R., & Laughlin, R. (2012). It was 20 years ago today: Sgt Pepper, accounting, auditing & accountability journal, green accounting and the blue meanies. Accounting Auditing & Accountability Journal, 25(2), 228–255.

- Harzing, A. W. (2000). An empirical analysis and extension of the Bartlett and Ghoshal typology of multinational companies. Journal of International Business Studies, 31, 101–120.

- Hasan, I., Singh, S., & Kashiramka, S. (2021). Does corporate social responsibility disclosure impact firm performance? An industry-wise analysis of Indian firms. Environment Development and Sustainability, 24(8), 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01859-2

- Hatane, S. E., & Soewarno, N. (2022). Corporate social responsibility and internationalisation in mitigating risk. International Journal of Sustainable Society, 14(3), 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSSOC.2022.125647

- Henry, L. A., Nysten-Haarala, S., Tulaeva, S., & Tysiachniouk, M. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and the oil industry in the Russian Arctic: Global norms and neo-paternalism. Europe-Asia studies, 68(8), 1340–1368.

- Hoi, C. K., Wu, Q., & Zhang, H. (2018). Community social capital and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 152(3), 647–665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3335-z

- Idemudia, U., & Ite, U. E. (2006). Corporate–community relations in Nigeria's oil industry: challenges and imperatives. Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management, 13(4), 194–206.

- Islam, M. A., & Deegan, C. (2008). Motivations for an organisation within a developing country to report social responsibility information: Evidence from Bangladesh. Accounting Auditing & Accountability Journal, 21(6), 850–874.

- Jamali, D., Jain, T., Samara, G., & Zoghbi, E. (2020). How institutions affect CSR practices in the Middle East and North Africa: A critical review. Journal of World Business, 55(5), 101127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2020.101127

- Jamali, D., & Karam, C. (2018). Corporate social responsibility in developing countries as an emerging field of study. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(1), 32–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12112

- Jamali, D., & Neville, B. (2011). Convergence versus divergence of CSR in developing countries: An embedded multi-layered institutional lens. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(4), 599–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0830-0

- Jnr, A. V. K. B., Kukah, A. S. K., & Akotia, J. (2021). Assessing perception and practice of corporate social responsibility (CSR) by energy sector firms in Ghana. International Journal of Real Estate Studies, 15(2), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.11113/intrest.v15n2.87

- Kirat, M. (2015). Corporate social responsibility in the oil and gas industry in Qatar perceptions and practices. Public Relations Review, 41(4), 438–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.07.001

- Li, S., & Lu, J. W. (2020). A dual-agency model of firm CSR in response to institutional pressure: Evidence from Chinese publicly listed firms. Academy of Management Journal, 63(6), 2004–2032. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2018.0557

- Maon, F., Lindgreen, A., & Swaen, V. (2009). Designing and implementing corporate social responsibility: An integrative framework grounded in theory and practice. Journal of Business Ethics, 87, 71–89.

- Matten, D., & Moon, J. (2008). “Implicit” and “explicit” CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 404–424. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2008.31193458

- Mbilima, F. (2021). Extractive industries and local sustainable development in Zambia: The case of corporate social responsibility of selected metal mines. Resources Policy, 74, 101441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2019.101441

- McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Profit maximizing corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 26(4), 504–505. https://doi.org/10.2307/259398

- Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1086/226550

- Moti, U. G. (2019). Africa’s Natural Resource Wealth: A Paradox of Plenty and Poverty. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 6(7), 4983–4503.

- Nazir, O., & Islam, J. U. (2020). Effect of CSR activities on meaningfulness, compassion, and employee engagement: A sense-making theoretical approach. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 90, 102630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102630

- Ntim, C. G., & Soobaroyen, T. (2013). Corporate governance and performance in socially responsible corporations: New empirical insights from a Neo‐Institutional framework. Corporate Governance an International Review, 21(5), 468–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12026

- Nwobu, O. A., Ngwakwe, C., Owolabi, A., & Adeyemo, K. (2021). An assessment of sustainability disclosures in oil and gas listed companies in Nigeria. International Journal of Energy Economics & Policy, 11(4), 352–361. https://doi.org/10.32479/ijeep.11095

- Orazalin, N. S., Ntim, C. G., & Malagila, J. K. (2023). Board sustainability committees, climate change initiatives, carbon performance, and market value. British Journal of Management. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12715

- Osei-Kojo, A., & Andrews, N. (2020). A developmental paradox? The “dark forces” against corporate social responsibility in Ghana’s extractive industry. Environment Development and Sustainability, 22(2), 1051–1071. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-018-0233-9

- Perez-Batres, L. A., Doh, J. P., Miller, V. V., & Pisani, M. J. (2012). Stakeholder pressures as determinants of CSR strategic choice: Why do firms choose symbolic versus substantive self-regulatory codes of conduct? Journal of Business Ethics, 110(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1419-y

- Pham, D. C., Do, T. N. A., Doan, T. N., Nguyen, T. X. H., Pham, T. K. Y., & Tan, A. W. K. (2021). The impact of sustainability practices on financial performance: Empirical evidence from Sweden. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1912526. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1912526

- Putnam Rankin, C. (2021). Under pressure: Exploring pressures for corporate social responsibility in mutual funds. Qualitative Research in Organizations & Management: An International Journal, 16(3/4), 594–613. https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-07-2020-2000

- Qureshi, M. A., Kirkerud, S., Theresa, K., & Ahsan, T. (2020). The impact of sustainability (environmental, social, and governance) disclosure and board diversity on firm value: The moderating role of industry sensitivity. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(3), 1199–1214. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2427

- Rahaman, A. S., Lawrence, S., & Roper, J. (2004). Social and environmental reporting at the VRA: institutionalised legitimacy or legitimation crisis?. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 15(1), 35–56.

- Raufflet, E., Cruz, L. B., & Bres, L. (2014). An assessment of corporate social responsibility practices in the mining and oil and gas industries. Journal of Cleaner Production, 84, 256–270.

- Renneboog, L., Ter Horst, J., & Zhang, C. (2008). Socially responsible investments: Institutional aspects, performance, and investor behavior. Journal of banking and finance, 32(9), 1723–1742.

- Sachs, J., Kroll, C., Lafortune, G., Fuller, G., & Woelm, F. (2021). Sustainable development report 2021. Cambridge University Press.

- Scott, W. R. (2001). Institutions and organizations. Sage.

- Somachandra, W. D. I. V., Sylva, K. K. K., Bandara, C. S., & Dissanayake, P. B. R. (2022). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices in the construction industry of Sri Lanka. International Journal of Construction Management, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2022.2049489

- Sun, W., & Xu, X. (2023). Sustaining firm sustainability endeavors: The role of international diversification on firm CSR capability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 412, 137402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137402

- Tan, Y., & Zhu, Z. (2022). The effect of ESG rating events on corporate green innovation in China: The mediating role of financial constraints and managers’ environmental awareness. Technology in Society, 68, 101906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.101906

- Tripathi, V., & Kaur, A. (2022). Does socially responsible investing pay in developing countries? A comparative study across select developed and developing markets. FIIB Business Review, 11(2), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/2319714520980288

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2017). State of commodity dependence 2016. UNCTAD.

- Wooten, M., & Hoffman, A. (2008). Organizational fields: past, present and future. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), Handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 130–148). Oxford University Press.