Abstract

This research was conducted by Coaches and Mentors of South Africa’s (COMENSA) Research Portfolio Committee (RPC) on behalf of the COMENSA board and the COMENSA Supervision Portfolio Committee (SPC). The purpose was to investigate how international and relevant literature defines supervision and how COMENSA might adapt their definition of supervision accordingly. In this way, COMENSA ensures that the definition is based on current research and evidence-based practice. The research design was descriptive in nature—it obtained information concerning the current status of a phenomenon (definitions of supervision) and described “what exists” concerning the phenomenon. Members of the RPC reviewed several academic articles and book chapters and then summarised these in a custom-developed template. The content of these templates was then transferred to ATLAS.ti for coding and thematic analysis. The research highlighted two main concepts related to the definition: The specialised knowledge of a trained supervisor; the end focus of supervision is and must be on the quality of the relationship between coach and coachee, in that the coachee must receive the best possible coaching from the practitioner.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Coaches and Mentors of South Africa (COMENSA) was recognised as a non-statutory (or self-regulating) professional body in 2015 by the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA). Through this recognition, and the registration of its designations, COMENSA commits to contributing to strengthening social responsiveness and accountability within the coaching and mentoring profession and promoting pride in association for the profession.

The primary purpose of regulation (both statutory and non-statutory) is the protection of the public from incompetence and unethical practitioners. Professional practitioners are therefore morally and behaviourally accountable to these associations. By credentialling its members, COMENSA aims to increase the credibility of their members, thereby instilling a level of trust with the public.

Credentialled members are required to maintain their professional designation through continuous professional development (CPD), of which receiving regular coaching supervision is but one activity. COMENSA requested research into this area, specifically to review their definition of coaching supervision.

1. Introduction

Coaches and Mentors of South Africa (COMENSA), founded in 2006, is a non-statutory professional body, recognised as such by the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA) in 2015. As a professional body, it is committed to enhancing the credibility of its members and is responsible for coherence and a framework within which its members work and are led by their professional ethics. COMENSA also operates in partnership and collegiality with international bodies of coaches and mentors. In recent years, COMENSA has paid attention to how international bodies of coaches and mentors conceptualise both coaching and coaching supervision. The immediate impression is that there are many different conceptualisations. Admittedly, for coaching supervision, this is due to the different contexts or academic traditions on which it is patterned. However, COMENSA committed to conceptualising coaching supervision for its members with a South African outlook (perspective)—this was also a commitment to reviewing its current definition of coaching supervision.

Thus, COMENSA through its RPC decided on a desk review of relevant literature, in a bid to conceptualise coaching supervision to situate it within the South African perspective, in addition to ensuring that the definition is based on current research and evidence-based practice. This paper presents a systematic review of relevant literature on coaching supervision. It aims to describe how, both locally and globally, the concept of coaching supervision is understood and defined. Accordingly, the review explores these questions:

(Q1) How does the relevant literature define coaching supervision?

(Q2) What are the elements of definitions?

(Q3) How might COMENSA adapt a new definition of supervision from the relevant literature?

The findings (definitions) presented in this paper are useful to the members of the COMENSA board, government departments, policymakers, researchers, and organisations interested in business and labour. The paper begins with a review of relevant literature on the definitions and conceptualisation of coaching supervision, with emphasis on the South African context. It also explicates the current definition within which COMENSA operates. Next, the methodology used in this paper is discussed, and the findings presented. The latter part of the paper focuses on discussing the findings and proposes the new definition for COMENSA.

2. Coaching supervision: relevant conceptualisations

There are several definitions of coaching supervision that are available in the literature. These definitions are significantly demonstrative of the growth that continues to take place in the field of coaching supervision. Like the coaching industry, the field of coaching supervision is not in its neophyte stages; it is a continuously evolving and developing space.

Coaching supervision aims at the transformation of the work of both the coach and the coached. Hawkins and Smith (Citation2006) demonstrated, in their work, that coaching is about the transformation of the system which includes both the coach and the client. This system is not only about the relationship between the coach and the client, but the system that includes the client’s work and practice. These authors also cautioned about the semblance of counselling supervision and coaching supervision. They posit that they are different, and this difference should be noted in the relationship especially as the notion of transformation could be blurred. It is that invitation to create the distinction that will enable coaching supervision to achieve a clearer identity with unnecessary complexity. Here, the drift is that the concept of coaching supervision cannot be universalised—this is a pertinent point made by the authors which has also shaped this current paper aiming to conceptualise coaching supervision for the South African context.

The growth and development of the coach has been given priority in different conceptualisations of coaching supervision. In this instance, coaching supervision is understood in a communitarian sense. The conceptualisation is that the coach also needs to be aided to continue to be a good service provider to the client. This is a dual action of improving the coach and inherently supporting the client with whom the coach works. Bluckert (Citation2006) avowed that there needs to be support given to coaches in their practice, and to facilitate the ability to assess what kind of service they truly give to their clients. The author describes supervision as “ … an opportunity to receive support, both practical, in the form of ideas and suggestions, and emotional” (Bluckert, Citation2006, p. 110). He acknowledges that supervision should be in the interest of both coach and client, and the responsibility and ethics rests within the relationship between coach and client.

Supporting the coach and supervising his or her work should be formalised and monitored. Here, the discourse is on recognising that coaching supervision needs to have hallmarks and performance indicators (Bachkirova et al., Citation2005). These indicators will engage the effectiveness of the current coach’s practice to his or her clients, evaluate their experiences and support their growth process. Coaching supervision is a process that cannot be left to chance. It needs to be formalised with the coaches’ association or regulatory bodies. Bachkirova et al. (Citation2005) did not explicate how it needs to be done (therefore our Q2 above regarding what the elements of a definition should be). But their emphasis is that a formalised structure and a known process determine it. This needed structure and formality is another propeller for this article from the COMENSA point of view—ensuring that their members can be supported with an evidence-based structure and contextual process. This emphasis on structure and formalisation has been echoed by Bachkirova (Citation2020) and even in their different works. The broader consensus is that coaching supervision is necessary and should be a working process. However, recognising that coaching supervision happens within different contexts, a universal approach cannot be established. This is the gap this paper looks to fill and engage: creating from already established discourses, a South African perspective of coaching supervision.

Significantly, COMENSA has a definition and conceptualisation with which they work, but there is a need with the changing global and local landscape to review and readapt it. The current COMENSA definition reads: “Supervision for coaches and mentors provides a safe and confidential space for reflective practice, in which a supervisee and a supervisor collaboratively and regularly engage in dialogue on the supervisee’s experiences, for professional and personal learning and development” (COMENSA, Citation2021). The above definition sits well with global leading research on supervision. However, the urgency to review, adapt and improve the definition is the major objective for the paper.

3. Methodology

This study adopted the interpretivism research philosophy that utilises qualitative techniques to collect and analyse data (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018). The methodology used in this study was twofold. In the first phase, the study made use of a qualitative literature review, as it was found to be more suitable for answering the research question. The study made use of thematic analysis to look at the keywords that have been used to define coaching supervision. Finally, the study applied a process by Unified Compliance Framework®, the Science of Compliance® (UCF, Citationn.d.), an online educational resource which describes how to write definitions. The process was adapted slightly to cater for this research project’s circumstances. A theory of change and a process model perspective was applied to the result, which provided additional focus points of supervision. Several academic articles and book chapters were reviewed by members of the Research Portfolio Committee and then summarised in a customer-developed template. The content of these templates was transferred to ATLAS.ti® for coding and thematic analysis. The result was then processed using the definitions writing approach, as mentioned above, and eventually, compared with the current definition of supervision.

4. How to write definitions

As researchers, we were confronted with the question of how to create or write a definition; what process and structure should be used to yield a well-researched and well-formulated definition? An additional research question was therefore established: What are the elements of definitions?

We found very little formal guidance other than that provided by UCF (Citationn.d..) with their extensive description of the importance of defining terms, describing what a definition is, types of definitions, and a highly useful process to follow for writing definitions.

UCF’s (Citationn.d.) handbook provided several steps in a definition-writing process. Of importance from an academic perspective, step one is to research the term, overlapping with a literature review. The next step is to select the definition type.

The definition writing process distinguishes between two general types of definitions and several specific types of definitions. The first general type is Intentional definitions, describing a clearly defined set of properties or features, all necessary and sufficient in themselves to fully explain the concept. The second general type is Extensional definitions, which defines a concept by providing a list of examples of items of the concept to define the concept. More specific types of definitions include Stipulative, Lexical, Partitive, Functional, Theoretical, Synonymous, and Encyclopaedic. The latter type of definition provides context and characteristics of the concept, and additional information about the concept.

We expected that a new definition of coaching supervision would be categorised as Intentional and Encyclopaedic.

The definition writing process steps continues with examples of cheat sheets and detailed diagrams for advanced definitions, which we adapted for our purpose.

5. Data collection and processing

In this systematic review, several scholarly publications and research works were used from South Africa, Africa and the international community that addresses the concept of coaching supervision. Table below explains the different criteria that were used in selecting the publications for this review. This paper examined both work that are peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed, like textbooks and reports. This was to provide an opportunity to engage every piece of work whether it was directly helpful to our current project or not. The works selected were those with content related to defining the concept of coaching supervision, rather than other content such as the benefits of supervision, challenges of supervision, supervision needs for newly qualified coaches, or supervision as an act of continuous professional development. Preference was given to high-profile and highly published researchers and practitioners in the global coaching industry like Bachkirova, Grant, Lawrence, Hawkins, and Passmore. Notably, since we were all English-speaking authors, we only considered publications that were written in the English language. This was to ensure we had the required linguistic tools to work effectively with the publications.

Table 1. Selection criteria of publications

No publication has been excluded in this work on the grounds of publication date. Different works were accepted within reasonable fashion, especially where they consider directly the concept of coaching supervision. Importantly, several kinds of works were accepted in the analysis of this paper—empirical studies, qualitative studies, quantitative studies, conceptual papers, conference proceedings, industry reports, organisational/institutional reports, and books. There is a synthetic possibility and knowledge that can emerge from every kind of work. We recognised this and incorporated as many works as possible into this paper (Denyer & Tranfield, Citation2009).

The identification of materials (publications) for this study was done through searching different academic sources, such as Google Scholar and several reputable journals. The initial publications assembled were 43. From this number, about 15 were excluded based on the main exclusion criteria that they were not focused on the definition or the conceptualisation of coaching supervision (Table ). They focused instead on the benefits of supervision, challenges of supervision, supervision needs for newly qualified coaches, supervision as an act of continuous professional development, amongst other issues raised therein.

From the initial 43, the publications were reduced to 28 publications. These 28 publications consisted of:

14 peer reviewed papers

6 organisational/institutional policies, guides, or research reports

4 books/chapters in a book

2 industry reports

1 dissertation

1 conference proceeding

The entire process of gathering the articles and deciding on which to include and exclude was carried out by members of the COMENSA Research Portfolio Committee between May 2021 and December 2021. The selected publications were summarised in a custom-developed template. The content of these templates was transferred to ATLAS.ti for coding and thematic analysis. The result was then processed using the definitions writing approach as mentioned above, and eventually compared with the current definition of supervision.

6. Results and discussion

Following the coding of the different publications, in conjunction with an adapted UCF (Citationn.d..) process of writing definitions, these initial categories emerged: reflective practice, systemic approach, structured and formal process, supervision models, psychological dimensions, knowledge and experience, professional support, professional coaching development, continued learning and co-created learning. On inspection of these categories, the researchers realised that these may already be a combination of categories and sub-categories, as required by the definitions writing process. We then proceeded to regroup them, and this yielded the following: systemic, structured, formal, contractual, confidential, regular process, professional support, professional coaching development, coach development, personal development, coaching competency development, continued learning; co-created learning, specific focus, intent, or impact and specialised knowledge.

Accordingly, the following two main themes emerged and are discussed below from synthesising the literature and the researchers’ analysis:

Reflective practice.

Professional coaching.

6.1. Reflective practice

Reflective practice studies within the coaching context have offered key models over the years for productive engagement within team coach supervision and one-on-one supervision (Cropley et al., Citation2018; Grant, Citation2022; A. Hullinger et al., Citation2019; Johns, Citation2017; Kovacs & Corrie, Citation2017; Seiler, Citation2021). This is recognised as a vital aspect in the supervisory field, reflective practices in dialogue and an in-depth context (McAnally et al., Citation2019). Moral and Lamy (Citation2018) offer a significant role in shaping the function of the definition for coach supervision. Validated as a core competency of the capacity of the supervisor by EMCC global framework 2019 (EMCC Supervision Guidelines), it is noted that reflective practices by coach supervisors demonstrate psychological mindedness as a competency (Association for Coaching, Citationn.d..).

Reflective practice can help avoid repeating unproductive behaviours while hoping for a productive result. This thinking approach is prevalent throughout the literature centred on coaching (A. Hullinger & DiGirolamo, Citation2020; Leary-Joyce & Lines, Citation2018). This is also seen more recently in the literature on coach supervision (Carden et al., Citation2021; A. M. Hullinger & J. A. DiGirolamo, Citation2020; Humphrey, Citation2020; Widdowson et al., Citation2020). Since reflective practice is commonly recommended for trainees in their coaching qualification journey, and experienced coaches looking to deepen their practice (van Nieuwerburgh & Love, Citation2019), we believe that it would enhance both in coach supervision. As the world leans towards globalisation, corporations and professionals constantly need productive ways to bridge diversity gaps while being inclusive. This will require coach supervisors to possess in-depth knowledge and resources to stretch their competencies to examine their performance and identify potential blind spots and/or unconscious prejudice when engaging with coaches (Dunford, Citation2017; Roche & Passmore, Citation2022; Tucker, Citation2018). Therefore, reflective practices can significantly impact the coach-coachee relationship, especially in the professional context.

6.2. Professional coaching

The greatest advantage of professional executive coaching is that it can help in managing large-scale change, that could result in a more meaningful behavioural change (Baykal, Citation2020; Enescu & Popescu, Citation2012; Gan et al., Citation2021). With the rise of concern of the tendencies of unconscious bias from executive leaders (McCafferty, Citation2022), positive coaching has increased self-efficacy, the motivation to advance and the sense of safety to discuss previously avoided personal issues—which requires a sufficient level of reflective skills (Tia Moin & Van Nieuwerburgh, Citation2021). Hence, professional executive coaching enhances the possibility for sustainable growth for their (coach and coachee) overall organisation, as executives can intentionally apply behavioural changes towards the needed change (Agarwal et al., Citation2022).

Coaching supervision comes in where space is offered to coaches for reflective practices to understand and resolve organisational ethical dilemmas (Ratlabala & Terblanche, Citation2022). From the coachees’ perspective in a professional setting, several authors agree that a coachee’s self-awareness has a direct impact on their perceived effectiveness or purpose from their coaching sessions (Gallastegui et al., Citation2019; Mosteo et al., Citation2021). Subsequently, professional executive coaching is a necessary step towards facilitating learning and applying reflective practices for accomplishing organisational goals as diversity, inclusion and change factors will effectively be resolved.

Further following the adapted process for writing definitions, Table , below, lists the regrouped set of categories and their sub-categories. A brief review of the literature combined with the researchers’ knowledge and experience provided sub-categories where sub-categories were unavailable. Upon further inspection of the table’s content, one of the researchers was reminded of previous unpublished research related to the South African coaching industry and the recognition of COMENSA as a non-statutory professional body. The research (Myburgh, Citation2014) is an unpublished master’s dissertation, Towards an impact evaluation: COMENSA’s strategic intent to professionalise the South African coaching industry, completed in 2014. The intention of any organisation registering as a non-statutory or self-regulating body with the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA) is to protect the public from incompetence and unethical practitioners, by establishing credibility of its members with the public. Even though professionalisation benefits the organisation’s members, the main focus is on the public’s interest. Applying this concept to supervision, the focus of supervision must be on the quality of the relationship between coach and coachee, in that the coachee must receive the best possible coaching from the practitioner.

Table 2. Category and sub-category analysis

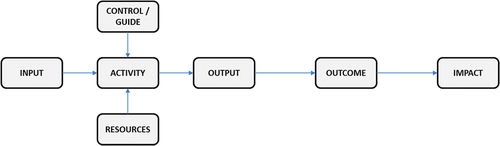

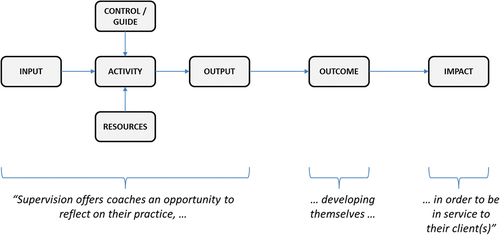

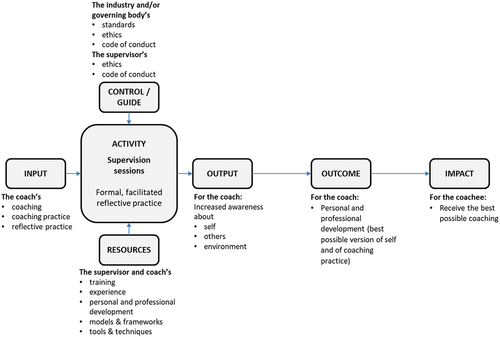

Through further application of the concepts in Myburgh’s (Citation2014) research, it is possible to provide a process perspective on coach supervision about the coach-coachee relationship. A combined visual perspective (Figure ) of a Theory of Change (TOC) and the process modelling technique (IDEF0) was used in the mentioned research to depict the impact of the professional coaching industry. TOC originates from the monitoring and evaluation industry to explain consequences—both intended and unintended. The horizontal activities of input, activity, output, outcome, and impact represent a typical TOC of “how an intervention is expected to lead to desired results” (Morra Imas & Rust, Citation2009, p. 109).

IDEF0 is a widely used function modelling or process documentation standard, now also integrated into the IEEE standards as a business process re-engineering standard (Li & Chen, Citation2009). The method combines graphics and text to provide logic and facilitate understanding and analysis. The core components of IDEF0 have a similar input, activity, and output approach with two additional “input” flows of control and resources.

The result is the diagram template below, where the input is transformed by the activity into an immediate output; the control and resources guide and support (respectively); the outcome represents a proximal output; and the impact represents a distal output.

Hullinger et al. (Citation2020), as cited in A. M. Hullinger and J. A. DiGirolamo (Citation2020, p. 3) made a statement about supervision, as a result of their research into the state of coaching supervision. They asserted that “ … supervision offers coaches an opportunity to reflect on their practice, developing themselves to be in service to their client(s)”. Applying this statement to the diagram template, it yielded Figure below, containing elements of the assertion below the figure:

Each of the TOC process blocks in the horizontal flow (as well as the IDEF0 resource process block), was then completed with explanatory content originating from Table . The content of the control process block is informed by the guidance from COMENSA’s (Citation2021) Supervision Policy, with the policy further contributing to the content resource process block.

Finally, the process outcome of coaching supervision consists of the direct output of increased awareness during and after a supervision session, leading to the proximal outcome of personal and professional development, and which results in the eventual (distal) impact of facilitating the best possible coaching for the coachee. The adapted theory of change demonstrates visually how the coaching, the coaching practice, and the reflective practice of the coach is transformed by coaching supervision to ultimately contribute to the relationship between the coach and coachee, for the coachee to receive the best possible coaching experience.

The next activity was to compare the result of the above process and the content of Table with COMENSA’s definition for coaching supervision at that point in time. The Supervision Policy (COMENSA, Citation2021) defined coaching supervision as follows:

Supervision for coaches and mentors provides a safe and confidential space for reflective practice, in which a supervisee and supervisor collaboratively and regularly engage in dialogue on the supervisee’s experiences, for professional and personal learning and development.

With the definition already containing concepts such as reflective practice, collaborative, regularly, dialogue, and professional and personal learning, we concluded that the COMENSA definition compares extremely favourably with the results of the research process thus far. As depicted in Figure , coaching supervision, not only benefits the coach but also the coachees through improved coaching service.

7. Necessity and sufficiency

While reflecting on the categories in Table , the current definition, and the distal impact of supervision, the researchers grappled with the question of whether this is sufficient as a definition—as stipulated by UCF (Citationn.d..) in their description of intentional definitions. As described by Myburgh (Citation2014), the coaching industry was, and still is, a globally statutorily unregulated space, which by default extends to coaching supervision. As far as we are aware, COMENSA is still one of two South African coaching organisations, and the only two worldwide, that are non-statutory professional bodies, regulating their credentialled members according to a country’s qualifications authority. This means that any person may declare themselves a coach and by extension, a coach supervisor. The further question arising was how to distinguish between coaching a coach and supervising a coach. Does the answer lie in the use of specific supervision models such as the well-known seven-eyed supervision model? Is the use of a supervision model sufficient to distinguish between coaching and supervision of a coach? If one coach applies a supervision model in a conversation with another coach, is that supervision or is it coaching the coach using a supervision model? Similarly, if a supervisor applies what is generally understood to be a coaching model in a conversation with a coach, is that coaching or supervision?

As researchers, we felt that the use of specific supervision models is necessary but not sufficient to define a conversation with a coach as supervision. Therefore, a coach using a supervision model in a conversation with another coach is not supervising—the person is coaching, even though they intend to supervise. The answer may be found in the last category in Table , i.e., the category of specialised knowledge, and supported by Hawkins et al.’s (2019) conclusion of formal training of the coach supervisor. Supervision requires specialised knowledge about concepts in which coaches are not necessarily trained. Psychological dimensions include parallel processes, knowledge of personal and professional coach development, and theoretical knowledge: solution-focused supervision, transactional analysis supervision or systemic supervision. Similar to a general person (with no training in the dynamics of coaching), a structured conversation with someone cannot strictly and safely be labelled as coaching. A conversation without being supported by specialised training in supervision should therefore not be labelled as supervision. By extension, this also applies to the popular concept of “peer group supervision”, wherein a group of coaches may apply supervision models and approaches with each other but are not trained in supervision. The COMENSA Supervision Portfolio Committee may want to deliberate on what kind of training/qualification is acceptable or desirable and if another form of training, such as in the case of a psychologist or coaching psychologist, would be acceptable.

As mentioned above, we expected that a new definition of coaching supervision would be categorised as both Intentional (general definition type) and Encyclopaedic (specific type).

We concluded that the COMENSA definition for coaching supervision should be expanded to highlight 1) that a supervisor should have received specific training in coaching supervision, and 2) that the distal outcome (impact) of coaching supervision is clearly stated. These additions would allow the new definition to conform to the Intentional definition description of UCF (Citationn.d..).

To conform to an Encyclopaedic type of definition, and to provide explanatory information to readers of the definition, we suggested to the COMENSA Supervision Portfolio Committee to expand on the properties or elements of the new definition. This will assist readers to have a shared understanding of the underlying concepts of the definition. The following summarises the guidance to the committee on which elements may require a more detailed description:

Formal: including contractual, systemic, structured, confidential, safe, regular

Reflective practice: Based on the work by Dewey (Citation1910), Schön (Citation1983), Kolb (Citation1984) and Wilson (Citation2008)

Coaching and mentoring practice: professional business practice, including any business processes, coaching or mentoring approaches, client interaction, models, tools and techniques, etc.

Personal development, and

Professional development

8. Conclusion

Answering our first research question above (how does the relevant literature define coaching supervision?), the literature provided evidence of a wide range of definitions of coaching supervision. The intention and terminology across these definitions overlap a great deal, as is demonstrated by the fact that COMENSA’s definition at the time of this analysis comparing so favourably with the broader research into coaching supervision. Finding an industry-based answer to research question 2 (what are the elements of a definition?), assisted the definition writing process tremendously, and we were able to successfully integrate it in our research process.

The answers to the first two questions provided background and a process to finding an answer to the third research question—How might COMENSA adapt a new definition of supervision from the relevant literature? Even though the COMENSA definition compared so favourably, we were still curious whether it was sufficient. By applying necessity and sufficiency principles to the current definition, considering the categories identified through the literature review, supervision requires specialised knowledge about concepts in which coaches are not necessarily trained. Examples of these are psychological dimensions, such as parallel processes, knowledge of personal and professional coach development, and theoretical knowledge, such as solution-focused supervision, transactional analysis supervision and systemic supervision. The result of this research can therefore be summarised by the proposal to COMENSA of a somewhat updated definition, with the addition of some of the categories as discussed in this paper:

Supervision for coaches and mentors provides a formal space for reflective practice in which a qualified supervisor and supervisee engage in dialogue. It is focused on supervisees’ coaching and mentoring practices for the purposes of their professional and personal development so that their clients receive the best possible coaching and mentoring.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Patrick Ebong Ebewo

Patrick Ebong Ebewo is a versatile Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Developer. He has worked with private and governmental organisations to develop ventures focusing on social impact. He was instrumental in establishing the Tshwane University of Technology Arts Incubator, a Southern African UNESCO Chair in Cultural Policy and Sustainable Development and the Centre for Entrepreneurship Development.

Elona Ndlovu-Hlatshwayo

Elona Ndlovu-Hlatshwayo (Candidate) is an emerging researcher interested in sustainable entrepreneurial development through entrepreneurial coaching and building sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems. She supervises Master research in both entrepreneurship and coaching. She is a Master Coach (ABCCCP).

Jacques Carl Myburgh

Jacques Carl Myburgh is an independent professional. He is involved with several South African academic organisations as a research supervisor, external moderator, and peer reviewer. He is one of the first credentialled members of this professional body – COMENSA Senior Coach (CSC). Together they sit on the COMENSA Research Portfolio Committee overseeing the research function.

References

- Agarwal, A., Mukherjee, B., Meyer, M., & Lomis, K. D. (2022). Coaching and ethics, diversity, equity, and inclusion. In M. M. Hammoud, N. M. Deiorio, M. Moore, & M. Wolff (Eds.), Coaching in medical education (pp. 75–13). Elsevier.

- Association for Coaching. (n.d.). AC Coach supervisor/supervisor competency framework. Retrieved August 7, 2021, from https://www.associationforcoaching.com/page/SADetails

- Bachkirova, T., Jackson, P., Hennig, C., & Moral, M. (2020). Supervision in coaching: Systematic literature review. International Coaching Psychology Review, 15(2), 1–24. https://radar.brookes.ac.uk/radar/items/b6abc742-08ba-41b9-b4f5-4c058a1e0536/1/

- Bachkirova, T., Willis, P., & Stevens, P. (2005). Panel discussion on coaching supervision. Oxford Brooks University Coaching and Mentoring Society, Spring 2005.

- Baykal, E. (2020). Mindfulness and mindful coaching. In E. Baykal, (Ed.), Handbook of research on positive organizational behavior for improved workplace performance (pp. 72–85). IGI Global. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.4018/978-1-7998-0058-3.ch005

- Bluckert, P. (2006). Psychological dimensions of executive coaching. Open University Press.

- Carden, J., Jones, R. J., & Passmore, J. (2021). An exploration of the role of coach training in developing self-awareness: A mixed methods study. Current Psychology, 42(8), 6164–6178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01929-8

- COMENSA. (2021). COMENSA Supervision Policy 6 July 2021. Version 1. Retrieved October 9, 2021, from https://www.comensa.org.za/

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage.

- Cropley, B., Miles, A., & Knowles, Z. (2018). Making reflective practice beneficial. In R. Thelwell & M. Dicks (Eds.), Professional advances in sports coaching (pp. 397–414). Routledge.

- Denyer, D., & Tranfield, D. (2009). Chapter 39 Producing a systematic review. In D. Buchanan & A. Bryman (Eds.), The sage handbook of organizational research methods (pp. 671–689). Editors Sage Publications Ltd.

- Dewey, J. (1910). How we think. D C Heath. https://doi.org/10.1037/10903-000

- Dunford, R. (2017). Toward a decolonial global ethics. Journal of Global Ethics, 13(3), 380–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449626.2017.1373140

- Enescu, C., & Popescu, D. M. (2012). Executive coaching-instrument for implementing organizational change. Revista de Management Comparat International, 13(3), 378–386. https://ideas.repec.org/a/rom/rmcimn/v13y2012i3p378-386.html

- Gallastegui, A. E., Abasolo, R. I., Rodríguez, L. J., & Ferrín, F. P. (2019). Analysis of executive coaching effectiveness: A study from the coachee perspective. Cuadernos de Gestión. https://doi.org/10.5295/cdg.170876ea

- Gan, G. C., Chong, C. W., Yuen, Y. Y., Yen Teoh, W. M., & Rahman, M. S. (2021). Executive coaching effectiveness: Towards sustainable business excellence. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 32(13–14), 405–1423. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2020.1724507

- Grant, A. M. (2022). Reflection, note‐taking and coaching: If it ain’t written, it ain’t coaching! In D. Tee & J. Passmore (Eds.), Coaching Practiced (pp. 71–83). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Hawkins, P., & Smith, N. (2006). Coaching, mentoring and organizational consultancy. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Hullinger, A., & DiGirolamo, J. (2020). A professional development study: The lifelong journey of coaches. International Coaching Psychology Review, 15(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsicpr.2020.15.1.8

- Hullinger, A. M., & DiGirolamo, J. A. (2020). The state of coaching supervision research 2019 update. International Coaching Federation. https://coachingfederation.org/app/uploads/2020/09/CoachingSupervision2019_SEP25.pdf

- Hullinger, A., DiGirolamo, J., & Tkach, J. (2019). Reflective practice for coaches and clients: An integrated model for learning. Philosophy of Coaching: An International Journal, 4(2), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.22316/poc/04.2.02

- Humphrey, S. (2020). An exploration of what experienced business coaches take to supervision. [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Wales Trinity Saint David.

- Johns, C. (2017). Becoming a reflective practitioner. John Wiley & Sons.

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall Inc.

- Kovacs, L., & Corrie, S. (2017). Building reflective capability to enhance coaching practice. In D. Tee & J. Passmore (Eds.), Coaching practiced (pp. 85–96). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Leary-Joyce, J., & Lines, H. (2018). Systemic team coaching. AOEC Press.

- Li, Q., & Chen, Y. (2009). IDEF0 function modelling. In L. Qing & Y. Chen (Eds.), Modeling and analysis of enterprise and information systems. From requirements to realisation (pp. 98–122). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-89556-5_5

- McAnally, K., Abrams, L., Asmus, M. J., & Hildebrandt, T. (2019, April 24-26). Coaching supervision: Global perceptions and practices. Proceedings of the 25th EMCC Mentoring and Coaching Conference, Dublin, Ireland. https://www.emccglobal.org/conference/25th-annual-mentoring-coaching-and-supervision-conference/

- McCafferty, A. (2022). How May Executive Coaches Advance Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Organizations?. Dissertation. Thomas Jefferson University

- Moral, M., & Lamy, F. (2018). La supervision des coachs à travers le monde: Situations et perspectives. In E. Devienne (Ed.), Le grand livre de la supervision (pp. 175–183). Éditions Eyrolles.

- Morra Imas, L. G., & Rust, R. C. (2009). The road to results. Designing and conducting effective development evaluations. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-7891-5

- Mosteo, L., Chekanov, A., & de Osso, J. R. (2021). Executive coaching: An exploration of the coachee’s perceived value. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(8), 1241–1253. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-02-2021-0046

- Myburgh, J. C. (2014). Towards an impact evaluation: COMENSA’s strategic intent to professionalise the South African coaching industry. [ Unpublished master’s dissertation]. Stellenbosch University.

- Ratlabala, P., & Terblanche, N. (2022). Supervisors’ perspectives on the contribution of coaching supervision to the development of ethical organisational coaching practice. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 20, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v20i0.1930

- Roche, C., & Passmore, J. (2022). Anti-racism in coaching: A global call to action. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research & Practice, 16(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17521882.2022.2098789

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Seiler, H. (2021). Using client feedback in executive coaching improving reflective practice. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Tia Moin, F. K., & Van Nieuwerburgh, C. (2021). The experience of positive psychology coaching following unconscious bias training: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching & Mentoring, 19(1), 74–89. https://doi.org/10.24384/n4hw-vz57

- Tucker, K. (2018). Unraveling coloniality in international relations: Knowledge, relationality, and strategies for engagement. International Political Sociology, 12(3), 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/oly005

- UCF. (n.d.). The Definitions Book: How to Write Definitions. Retrieved October 10, 2021, from https://www.unifiedcompliance.com/education/how-to-write-definitions/

- van Nieuwerburgh, C., & Love, D. (2019). Advanced coaching practice: Inspiring change in others. Sage.

- Widdowson, L., Rochester, L., Barbour, P. J., & Hullinger, A. M. (2020). Bridging the team coaching competency gap: A review of the literature. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching & Mentoring, 18(2), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.24384/z9zb-hj74

- Wilson, J. P. (2008). Reflecting‐on‐the‐future: A chrono-logical consideration of reflective practice. Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 9(2), 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940802005525