Abstract

This study intended to examine the relationships between empowerment leadership, psychological empowerment, and affective commitment on work engagement. Importantly, this study aimed to examine the moderating role of self-efficacy on the relationship between psychological empowerment and affective commitment on work engagement. The data were collected in a two-waves week time lag, data was gained from 375 full-time front-line employees working in five-star hotels in Erbil. The structural equation modelling (SEM) using partial least squares (PLS) was used to analyze the research model. Thus, our results indicated that empowerment leadership is positively related to psychological empowerment, and affective commitment as well as psychological empowerment, and affective commitment were found to be significantly related to work engagement. Self-efficacy was a vital moderator in the relation of psychological empowerment, and affective commitment toward work engagement such as the relationship is stronger when self-efficacy is high than low. This study provides theoretical and managerial implications such as having to empower leadership in the workplace because it provides a sustainable competitive advantage to organizations as well as limitations and future research directions. This study, like every study, has limitations. To begin with, the responses were confined to front-line employees working in five-star hotels, thus the findings cannot be applied to employees working in other types of hotels in the hotel industry. The managerial implication is this study has shown the importance of having empowering leadership in the workplace because it provides a sustainable competitive advantage to organizations. In suggestions to initiate empowerment leadership, hotels should hire and train leaders who are willing to empower their subordinates how to empower their subordinates.

1. Introduction

Since the current global economic downturn and post-recession recovery, there has been an increase in global competition, which has an impact on many businesses and industries around the world. Tourism and hospitality are particularly mentioned for major and ongoing consequences (Ghaderi et al., Citation2021; Veile et al., Citation2022). Businesses in the hotel sector have noticed major changes in customer demand, consumer buying habits, and income (Sipe, Citation2021). Higher service standards and a greater need for quality service from a wider range of clients are also listed as new challenges. In light of these problems, the relevance of the links between customer service, employee work habits, and corporate outcomes has expanded (Martínez-Martínez et al., Citation2019; Teng et al., Citation2020). Therefore, in the dynamic and fast-paced environment of hotels, employee engagement stands as a fundamental pillar for sustainable success and exceptional guest experiences. When hotel employees are genuinely engaged in their work, it becomes evident in the passion and dedication they display while serving guests. Engaged employees go beyond their job descriptions, actively seeking opportunities to elevate the level of service they provide. Their emotional connection to the organization fosters a sense of ownership and pride in their roles, leading to a positive impact on team collaboration and overall work culture. Additionally, engaged employees are more inclined to embrace continuous improvement, constantly seeking ways to enhance their skills and knowledge to better serve guests. By investing in employee engagement initiatives, hotels can create a fulfilling work environment that not only boosts employee morale and loyalty but also leaves a lasting impression on the hearts of every guest who walks through the doors (Hassan et al., Citation2021a; Rabiul et al., Citation2022; Wang & Hall, Citation2023).

Therefore, in the current global business environment, studies have proven that businesses with engaged employees are more successful (Bakker & Bal, Citation2010; Putra et al., Citation2017). Moreover, employee engagement increases business revenue, lowers labour costs (Rabiul et al., Citation2023; Uzir et al., Citation2020), increases employee retention rates (Karatepe et al., Citation2013; Tsaur et al., Citation2019), and boosts job satisfaction and performance overall employees (Hassan et al., Citation2020; Saks, Citation2006). Employee work engagement, on the other hand, is a challenge for several businesses around the world (Bakker & Leiter, Citation2017; Tsaur & Hsieh, Citation2020). Therefore, academics and business experts have devoted focused attention to the study of work engagement in order to test and learn precise determinants and effects of work engagement (Alarcon & Edwards, Citation2011; Uzir et al., Citation2021).

According to various academics, empowered leadership is an important approach to raising employee engagement at work (e.g., Rabiul & Yean, Citation2021). This is because employees believe that their leaders are enabling them to exercise self-control, self-regulation, self-management, and self-leading when they engage in empowerment leadership (Dewettinck & van Ameijde, Citation2011). In addition, empowered leaders are more likely to delegate tasks and share information, promote accountability, permit group decision-making, coach, share information, set an exemplary example, and show empathy for their subordinates by paying attention to them (Bester et al., Citation2015; Joo et al., Citation2016). Consequently, employee engagement depends on empowered leadership.

Additionally, studies have shown that organizational commitment helps organizations succeed better and reach their goals since linked people are more productive and committed to their work (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005). Since affective commitment involves an obligation, it is one of the essential components of organizational behavior. This study also focuses on emotional commitment. So, affective commitment is more likely than the other two commitment dimensions to be significantly linked with attitudes and behaviors (Grant et al., Citation2008; Gupta et al., Citation2016). Also, psychological empowerment was considered as echoes the continuous flow of employees’ perceptions and behavior about their workplace (both the local and the larger organization setting) in regard to one another (e.g., Rabiul et al., Citation2023). Psychological empowerment to a variety of organizational variables, where one of the most important factors is work engagement (Spreitzer, Citation1992)

Despite, the agreement of prior studies on the importance of these factors none of the previous research has incorporated them in a single model. For example, past studies found that empowered leadership is related to work engagement (e.g., Alotaibi et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, the current study brought all of the variables together in a single which may to some extent substitute for each other in affecting employee engagement and enhancing the theory as well as in a different developing context like Iraq unlike the prior studies (e.g., Al Otaibi et al., Citation2022). Importantly, self-efficacy was deemed an essential moderator in this study. Thus, this study also contributes to the knowledge by introducing self-efficacy s a moderator that can affect and enhance the link between psychological empowerment and work engagement as well as the link between effective commitment to work engagement. This is considered a crucial contribution because self-efficacy refers to both one’s actual skills and one’s perceptions of what one could accomplish with those skills (Bandura, Citation1986a). People’s belief and confidence in their ability to execute a task, as well as their willingness to modify their thoughts in the future, are referred to as self-efficacy (Munir et al., Citation2016; Hassan et al., Citation2021b) in order to remain a member of the organization Employees with a high level of self-efficacy believe they have sufficient talents and abilities to achieve their individual and organizational goals, and their state of mind at work supports this conviction (i.e., work engagement) (Bandura, Citation1991). Thus, employees having high self-efficacy (that is, a better expectation of mastery) have been more likely to retain working on their objectives irrespective of the situation (Bandura & Schunk, Citation1981).

In short, this study has examined the following aspects: (i) The relationships between empowerment leadership, psychological empowerment, and affective commitment on work engagement. (ii) this study further explores the moderating role of self-efficacy on the relationship between psychological empowerment and affective commitment on work engagement among front-line employees in the hotel’s context and has identified the three specific objectives are driven as followed:

Examining the influence of empowerment leadership on psychological empowerment and affective commitment.

Clarifying the effect of psychological empowerment and affective commitment on the employee’s work engagement

Exploring the moderating role of self-efficacy on the relationship of psychological empowerment and affective commitment toward employee’s work engagement.

1.1. Contextualization

Regarding the subject of engagement in Iraq, not only is there less of it, but the caliber of the job may be deteriorating as well. This is so because disengaged workers are less focused on the quality of their work and are consequently lesser likely to perform at a high level (Mohammed & Khlif,). As a result, unmotivated and unhappy workers frequently feel trapped in their employment and unable to envision a clear career path. They appear inactive and as if they aren’t picking up new abilities. All of that is a result of the industries’ lack of leadership empowerment and psychological empowerment, both of which are unquestionably essential for work engagement (Ismael & Yesiltas, Citation2020). Additionally, the expectations for team performance could be overwhelming them. As a result, they could feel uneasy and put undue pressure on their workers. In short, micromanagement might encourage low involvement. Therefore, this unique study provides new evidence from different perspectives not only to help understand the scope and type of Iraqi industries (e.g., hotels) but also to analyze the effectiveness of leadership and their psychological empowerment a self-efficacy, in order to assess the weakness in the engagement scheme. In order to do so, new data, which focuses on the experience of empowerment leadership, psychological empowerment, affective commitment and self-efficacy, have been collected and analyzed focusing on the hospitality industry.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Empowerment leadership theory

Empowerment leadership theory explains that empowered leaders encouraged their followers to be self-leaders, participate in goal setting, and to work in teams (Dewettinck & van Ameijde, Citation2011). Thus, they argued that this theory is applicable in situations involving self-managed teams and empowered leadership. One of the essences of empowerment leadership is self-leadership, which refers to steps taken by individuals who push themselves towards higher levels of performance and effectiveness (Manz, Citation1986).

Empowerment leadership theory draws its foundations from social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation1986b) and participative goal-setting research (Erez & Arad, Citation1986). The triadic reciprocity in social cognitive theory explains that individuals’ cognitive processes, their behavior, and environment influence one another (Al Halbusi et al., Citation2021; Pearce et al., Citation2003). Therefore, it implies how empowered leaders are able to influence their subordinates to be self-leaders (Dewettinck & van Ameijde, Citation2011). Empowered leadership is also important in participative goal setting because of the need for self-management skills (Pearce et al., Citation2003). Empowered leaders nurtured self-management skills among subordinates through participative goal setting especially by implementing management by objectives (Pearce et al., Citation2003). Hence, empowerment leadership theory sets the causal flow from empowerment leadership to psychological empowerment. Furthermore, according to Alotaibi et al. (Citation2020) both empowering leadership and psychological empowerment form empowerment leadership theory.

2.2. Empowering Leadership (EL) and Psychological Empowerment (PE)

Empowerment Leadership is a management strategy that entails giving employees authority, autonomy, and decision-making ability, allowing them for consumption responsibility for their jobs and contribute more effectively to the organization’s success (Bharadwaja & Tripathi, Citation2020). This leadership style is distinguished by trust, open communication, and an emphasis on growing team members’ abilities and potential. Leaders who believe in their employees’ skills empower them to make decisions, solve problems, and innovate (Spreitzer, Citation1995).

Empowerment leadership is critical in ensuring employee psychological empowerment. Leaders that practice empowerment leadership establish a work climate based on trust, respect, and open communication (Knezovic & Musrati, Citation2018; Rabiul et al., Citation2023). This approach encompasses delegating authority, granting autonomy, and encouraging employees to make decisions and take ownership of their roles. When employees feel trusted and supported by their leaders, they develop a sense of control and self-determination in their work, contributing to the dimension of psychological empowerment related to autonomy (Amundsen & Martinsen, Citation2015; Wen et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, empowerment leaders invest in developing the skills and capabilities of their team members, instilling a belief in their competence to handle challenges and achieve their goals, addressing the dimension of psychological empowerment associated with competence. Moreover, by involving employees in decision-making processes and recognizing their contributions, empowerment leadership enhances the meaning and impact of their work, further reinforcing the dimensions of psychological empowerment (Alotaibi et al., Citation2020). In this way, empowerment leadership creates a positive and empowering work environment that nurtures employees’ self-belief, fostering their psychological empowerment and ultimately leading to higher levels of motivation, job satisfaction, and commitment to the organization (Singh & Sarkar, Citation2012).

In essence, empowering leadership (EL) represents a transformative approach to leadership that prioritizes decentralization of authority, fostering a sense of autonomy and accountability among team members. By relinquishing control and enabling individuals to make decisions, EL aims to cultivate a dynamic and innovative work environment. However, its efficacy heavily hinges on the leader’s ability to strike a balance between guidance and freedom, as excessive autonomy can lead to chaos (Wen et al., Citation2023). On the other hand, Psychological Empowerment underscores the intrinsic motivation and belief in one’s capabilities within a professional setting. This concept recognizes that individuals who feel competent, have a sense of impact, can influence their work environment, and perceive their tasks as meaningful, are more likely to contribute positively. Nonetheless, Psychological Empowerment is not a one-size-fits-all solution; its effectiveness is contingent upon organizational support and alignment between individual aspirations and collective goals (Turcotte‐Légaré et al., Citation2023). Both empowering leadership and psychological empowerment present promising paradigms, yet their practical implementation necessitates astute calibration to maximize their benefits while mitigating potential pitfalls. Therefore, based on the empirical support and the foundation of EL theory where empowered leaders encourage their subordinates to be self-leaders, the following hypothesis has been established.

H-1: Empowering leadership (EL) is positively related to psychological empowerment (PE)

2.3. Empowering leadership and affective commitment

Meyer and Allen (Citation1991) defined affective commitment as “an emotional attachment to identification with and involvement in the organization as a result of positive work experiences” (p. 67) and added that affective commitment produces a profound emotional relationship of the followers with their organization. Because empowering leaders fosters enthusiasm and competence amongst individuals, as well as increases their engagement in working practices, followers may feel more confident and have favorable experiences and emotions about their work (Meyer & Allen, Citation1997). Thus, empowering leadership has a strong and positive relationship with affective commitment among employees, as evidenced by recent research. Thus, empowering leadership represents a progressive leadership style that promotes autonomy, participation, and shared decision-making among team members. This approach is believed to foster a sense of ownership and engagement, leading to positive outcomes such as increased job satisfaction and performance. However, while EL can enhance employees’ affective commitment by nurturing a sense of belonging and fulfillment, its impact can vary based on factors like organizational culture, employee readiness, and leader competence. Leaders must be attuned to the individual needs and preferences of their team members to effectively cultivate strong affective commitment through Empowering Leadership (Zhang et al., Citation2023).

Empowering leaders creates a work environment that fosters trust, open communication, and employee involvement in decision-making (Carmeli, Citation2003). This approach cultivates a sense of ownership and dedication to the organization, leading to higher levels of affective commitment (Chaudhry et al., Citation2021). Employees who experience empowerment are more likely to feel emotionally attached to the organization, exhibit higher loyalty, and have a desire to contribute to its success (Ma et al., Citation2020). Affective commitment, in turn, reinforces the relationship with empowering leadership, as committed employees are more likely to respond positively to leadership efforts, trust their leaders, and feel valued for their contributions (Al-Riyami & Dollard, Citation2020). Overall, recent studies confirm that empowering leadership plays a vital role in fostering affective commitment among employees, resulting in a more engaged and committed workforce. Hence, based on the above argument we developed the hypothesis.

H-2: Empowering Leadership (EL) is positively related to affective commitment.

2.4. Psychological empowerment and work engagement

Based on Spreitzer (Citation1995), psychological empowerment refers to an individual’s sense of control, competence, and autonomy in their work environment. It is a subjective perception of empowerment that encompasses four key dimensions: meaning, competence, self-determination, and impact. People who experience psychological empowerment at work feel a sense of purpose in their tasks, believe in their ability to accomplish their work successfully, have a degree of autonomy in decision-making, and perceive that their efforts can make a difference and have an impact.

Typically, psychological empowerment and work engagement share a significant and positive relationship, as supported by recent research findings. Psychological empowerment refers to an individual’s belief in their own competence, autonomy, and impact in the workplace (Li et al., Citation2021). When employees feel empowered, they are more likely to experience higher levels of work engagement. Work engagement is characterized by enthusiasm, dedication, and absorption in one’s job (Schaufeli et al., Citation2006). Empowered employees tend to be more motivated, proactive, and committed to their roles, leading to increased levels of work engagement (Breevaart et al., Citation2014). They feel a sense of ownership and responsibility for their work, and this emotional connection translates into higher job satisfaction and performance (Gómez et al., Citation2022). In turn, work engagement further reinforces the perception of psychological empowerment, creating and positive feedback loop that enhances both aspects. Recent studies demonstrate that psychological empowerment and work engagement are mutually reinforcing constructs that contribute to a more productive and fulfilling work environment (Al Otaibi et al., Citation2022; Zhang et al., Citation2022). Therefore, psychological empowerment is a key factor in driving work engagement, representing a vital interplay between an individual’s perception of their own capabilities, autonomy, impact, and the meaningfulness of their work. When employees feel empowered to make decisions and influence their work environment, it often leads to a heightened sense of ownership and investment in their tasks. This, in turn, fosters work engagement—a state of deep involvement, enthusiasm, and dedication to one’s job. Nevertheless, the relationship between psychological empowerment and work engagement is not unidirectional; a high level of work engagement can further reinforce an individual’s sense of empowerment as they experience the positive outcomes of their efforts. Organizations that prioritize both psychological empowerment and work engagement can create a virtuous cycle that promotes employee well-being and organizational success (Schaufeli et al., Citation2006). Thus, organizations that foster psychological empowerment are more likely to experience higher levels of work engagement, leading to a more committed and enthusiastic workforce. Consequently, based on the above argument the research hypothesis is formulated.

H-3: Psychological empowerment is positively related to work engagement.

2.5. Affective commitment and work engagement

Affective commitment and work engagement are two important constructs in the field of organizational psychology, and understanding their relationship is crucial for promoting employee well-being and organizational success. Affective commitment refers to an individual’s emotional attachment and identification with their organization, while work engagement represents a positive, fulfilling, and energized state in which employees are fully immersed in their work tasks. While these concepts share similarities, recent research emphasizes the need to differentiate them, as they are distinct in nature.

Studies have shown that affective commitment can have a positive influence on work engagement. When employees feel emotionally connected to their organization, they are more likely to invest themselves in their roles and display higher levels of dedication and enthusiasm (Meyer et al.,). However, it is essential to recognize that affective commitment alone may not guarantee high levels of work engagement. Other factors, such as job resources, leadership support, and individual characteristics, play crucial roles in shaping work engagement (Dirks, Citation2023; Liang & Scott, Citation2020). Organizations should adopt a multi-faceted approach to enhance both affective commitment and work engagement among their employees. This can be achieved by fostering a positive work environment that promotes job satisfaction, supports employee growth and development, and recognizes and rewards their contributions (Bakker & Albrecht, Citation2018). Additionally, providing opportunities for employees to participate in decision-making processes and ensuring a fair and inclusive workplace can further bolster affective commitment and work engagement (Rich et al., Citation2022). In particular, affective commitment and work engagement are intertwined constructs that reflect employees’ emotional connection and dedication to their work and organization. Affective commitment signifies an employee’s attachment to the organization, driven by feelings of loyalty and identification, often resulting in higher retention rates and reduced turnover intentions. On the other hand, work engagement represents a dynamic state of vigor, absorption, and dedication in one’s tasks, leading to enhanced job performance and overall well-being. While both Affective Commitment and Work Engagement contribute to positive outcomes, they encompass distinct dimensions—commitment focusing on the emotional bond with the organization and engagement on the active involvement in tasks. Organizations aiming to cultivate a motivated and loyal workforce should consider nurturing both Affective Commitment and Work Engagement, recognizing their nuanced roles in influencing employee behavior and organizational success (Jiang et al., Citation2020). Thus, recognizing the distinct but interconnected nature of affective commitment and work engagement is vital for organizations seeking to create a motivated and dedicated workforce. By implementing comprehensive strategies that address both constructs and considering the influence of various factors, organizations can cultivate an environment that fosters high levels of affective commitment and work engagement, leading to increased employee satisfaction and improved organizational performance (Dehghanpour et al., Citation2022). Thus, the following hypothesis was stated.

H-4: Affective Commitment is positively related work engagement.

2.6. Moderating role of self-efficacy

The moderating role of self-efficacy in the relationships between psychological empowerment and work engagement, as well as between affective commitment and work engagement, has become a prominent area of research in organizational psychology. Typically, psychological empowerment refers to the perception of having control over one’s work and the ability to make meaningful contributions, while work engagement signifies a positive and fulfilling state of being fully absorbed in one’s job tasks. Recent studies have explored how self-efficacy, the belief in one’s capabilities to accomplish tasks, can influence these associations (Al Halbusi & Amir Hammad Hamid, Citation2018; Lu et al., Citation2018). Research by Zhang et al. (Citation2022) revealed that self-efficacy moderates the relationship between psychological empowerment and work engagement. Employees with high self-efficacy are more likely to perceive themselves as capable of taking on challenging tasks resulting from their psychological empowerment, leading to increased work engagement. On the other hand, individuals with low self-efficacy may struggle to translate feelings of empowerment into active engagement, potentially hindering their enthusiasm and dedication to work tasks.

Moreover, a study by Li and Scott (Citation2023) highlighted that self-efficacy also plays a moderating role in the relationship between affective commitment and work engagement. Employees with strong affective commitment tend to be more engaged when they have high self-efficacy, as they believe in their abilities to contribute meaningfully to the organization. In contrast, individuals with low self-efficacy may find it challenging to fully engage, despite their emotional attachment to the organization. Understanding the moderating role of self-efficacy in these relationships offers valuable insights for organizations aiming to promote employee engagement. By fostering a sense of empowerment and providing opportunities for skill development, organizations can enhance self-efficacy beliefs among employees, leading to heightened work engagement (Naeem et al., Citation2020). Moreover, supporting individuals with lower self-efficacy through training and mentoring initiatives can help bridge the gap and boost their engagement levels. Hence, recent research underscores the critical role of self-efficacy in influencing the connections between psychological empowerment, affective commitment, and work engagement. Recognizing and addressing the moderating effect of self-efficacy can guide organizations in formulating targeted strategies to foster a highly engaged and committed workforce (Hassan et al., Citation2021). Thus, in this study, it is hypothesized that the impacts of psychological empowerment and affective commitment on work engagement are stronger in high self-efficacious employees compared to those with lower self-efficacy (See Figure ).

H-5:

The relationship between psychological empowerment and work engagement is moderated by self-efficacy such this relationship is stronger under a high level of self-efficacy than a low level of self-efficacy.

H-6:

The relationship between affective commitment and work engagement is moderated by self-efficacy such this the relationship is stronger under a high level of self-efficacy than the low level of self-efficacy.

3. Method

3.1. Sampling and process

The population of this study is defined as employees working at hotels. Thus, this study used the non-probability sampling technique as it’s considered the best option to achieve the target number of respondents. Among all types of non-probability sampling design, a purposive sampling design was chosen for this study. So, as the level of analysis of this research is individual (Hulland et al., Citation2018). The employees are the population of this study since they are involved in the process of data collection to fill-up separate sets of questionnaires based on the research objectives. Since this study consists of full-time employees who are working in such industries.

The data was gathered from 375 full-time front-line employees in five-star hotels in the northern region of the Republic of Iraq, mainly Erbil was used to verify the proposed relationships. Therefore, in the current research, there were contacted 15 five stars hotels only 10 agreed to participate in the study. Thus, as the Kurdistan region is considered the safest place hotel accommodation in Iraqi Kurdistan (e.g., Erbil) has grown enormously in the past few years, even though the region still has to establish itself as a tourist destination. The total number of hotels in Erbil has tripled over the past three years (Al Halbusi et al., Citation2022). Nevertheless, prior to the circulation of the survey, senior human resources were approached in each hotel to ask permission for the study: once permission was approved, the survey was circulated. Thus, with 10 five-star hotels in Erbil, the research team communicated with the senior human resources of all five-star hotels with a letter that encompassed the drive of the study (e.g., empowerment leadership, affective commitment, psychological empowerment, self-efficacy, and work engagement) and permission for data gathering. Hence, the data was collected self-administered this method was chosen since is one of the most common practices in this field of study.

Since measurement error may exaggerate or deflate the reported relationships among research variables, common method bias is a serious risk (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003, Citation2012). Hence, in accordance with that, several guidelines were utilized such as a temporal separation by introducing a time lag of two weeks between the measurement of the predictor and criterion variables. In particular, two different questionnaires were used in this study: the (Time-I) and (Time-II) questionnaires. The (Time-I) questionnaire included the empowerment leadership affective commitment and psychological empowerment. The (Time-II) survey contained self-efficacy and work engagement as well as items relating to respondents’ age, gender, education, and organizational tenure (Afthanorhan et al., Citation2021). Therefore, two waves of data were obtained from frontline hotel personnel, separated by a two-week time gap. Each employee was assigned a unique number, which was then recorded on each questionnaire in the master list. The study team took great care to maintain confidentiality throughout the process. A similar process was used to match the questionnaires from (Time-I) and (Time-II). The research team has given Time I and Time II questionnaires to frontline employees, which would comprise instructions concerning anonymity and confidentiality. Each employee was instructed to fill out the survey on their own, place it in an envelope, and return it to the research group.

In addition, the survey was heading with a cover letter explaining the purpose of the survey and gave clear instructions as well as assured the confidentiality of their responses and requested that respondents return the completed survey directly using the prestamped envelope. The refusal rate was very low. Therefore, out of 470 questionnaires sent out only responses 375 were returned from the data collection. We checked the missing data and outliers and thus, notably, 95 of the questionnaires were not returned and others had irregularities and had to be excluded.

3.2. Variables measurement

The items measurement was defined and developed for final data collection all the items were adapted from the previous research. However, in this study, all the items were translated from the English version to the Arabic version because all the respondents are Arab speakers. Prior to translating, the researcher conducted a pre-test on the English version to ensure that the content is accurate, understandable, and appropriate. Also, the pre-test and pilot test procedures were applied for the Arabic version. As mentioned earlier, the pre-test was conducted using a target sample and a pilot test was conducted in this study to ensure the appropriateness and clarity of the questions, so the pilot study was conducted among 85 participants which are completely different from the main sample and thus both procedures help us to ensure the items validate and reliability before the final data collection (Memon et al., Citation2017). Subsequently. the questionnaires were translated according to the Double-Blinded Principle. The original English version of the scales was translated into Arabic, and the Arabic version was back-translated by two professional researchers (Brislin, Citation1980) to assure their validity. Thus, they resolved any disagreements and finalized the questionnaire. The 5-point Liker-type scale with strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neutral (3), agree (4), and strongly agree (5) as anchors were employed.

Empowering leadership (EL), was measured with 20-items these items were taken from Zhang and Bartol (Citation2010). This 20-item measure has multi-item sub-scales responding to four dimensions: (1) leading by example (3-items), (2) participative decision-making (4-items), (3) coaching (4-items), (4) informing (4-items), and (5) showing concern and developing strong relationships with members (5-items). For the affective organizational commitment was measured with the six-item scale used in Rhoades et al. (Citation2001), which combines items from measures presented by Meyer and Allen (Citation1997). Regarding psychological empowerment (PE), this variable was assessed with the 12-items taken from (Spreitzer, Citation1995) which encompasses four dimensions: (1) work meaning (3-items), (2) competence (3-items), (3) self-determination (3-items) and (4) work impact (3-items). In regards to self-efficacy, this variable contained 4-items borrowed from (Spreitzer, Citation1995). Finally, the work engagement was measured with 17-items reflecting four dimensions. (1) Vigor (6-items), (2) dedication, (5-items), (3) absorption (6-items) adopted from (Schaufeli et al., Citation2006).

3.3. Demographic profile of respondents

Participants’ gender, age, marital status, degree of education, and employment experience were acquired from the respondents, as seen in Table . Regarding gender, 75.6% of the respondents were males 24.4% were females. In terms of age, 10.6% were under 25 years old, 29.6% were between ages 25 and 30, 42.6% were between ages 31 and 40, 22.4% were between ages 41 and 50, and 8.7% were above the age 51. In sorting marital status 18.9% were single and 73.7% were married. For the educational level, 13.2 were had high school, 15.3 held a diploma, for the people who had bachelor’s degree were around 54.8%, only 9.1% were had a master’s degree and 6.5% held a doctorate degree. In regards to the job experience, 5.1% had less than 2 years of experience, 23.1% had 3–5 years, 36.9% had 6–10 years, 12.6% had 11–15 years, and 8.9% had more than 16 years.

Table 1. Respondent’s Demographics Profile

4. Data analysis and results

In this work, structural equation modeling (SEM) using partial least squares (PLS) was employed to examine the research framework. Therefore, Smart-PLS 3.3.9 software was employed (Ringle et al., Citation2018). This is due to the fact that Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) utilizing (PLS) is a strong, reliable statistical procedure (Henseler et al., Citation2009). It is suitable for complex causal analyses with both first- and second-order constructs and does not necessitate strict assumptions about the distribution of the variables (Hair et al., Citation2017). The PLS analysis generated bootstrap t-statistics with n − 1 degrees of freedom using 5,000 subsamples to examine the statistical significance of the route coefficients (Hair et al., Citation2017, Citation2019).

4.1. Measurement model assessment

To assess the measurement model, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity were used to evaluate the measurement model. Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability (CR) were used to assess the measuring scale’s internal consistency. The range of the Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability (CR) were indicative of the acceptable level of 0.70. Based on these, the indication of the internal consistency reliability was established (Hair et al., Citation2017). The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) was also confirmed because the AVE for all the constructs exceeded the threshold (Hair et al., Citation2017) (see Table ). In addition, there was no problems with discriminant validity; the AVE for each construct was greater than the variance shared by each construct with the other latent variables (Hair et al., Citation2017). Also, as shown in Table , the HTMT values are less than 0.90, indicating that each pair of variables has discriminant validity. All HTMT values are significantly different from 1, and the 95 percent confidence intervals (CI) do not include 1 (Henseler et al., Citation2015), indicating that each pair of variables has discriminant validity.

Table 2. Measurement model, Loading, construct Reliability and Convergent validity

Table 3. Discriminant validity via Fornell and Larcher

4.2. Structural model assessment: hypothesis testing

The hypothesis was examined as it presents the relationship between (empowering leadership and work engagement through affective commitment and psychological empowerment). Based on the application, the results demonstrated in Table , there is a statistically significant positive relationship between empowering leadership and psychological empowerment with (β = 0.386, t = 6.467, p < 0.000). Hence, H1 was supported, meaning that empowering leadership enhances psychological empowerment positively. For the H2 the relationship between empowering leadership and affective commitment was significant with (β = 0.198, t = 3.019, p < 0.001). Hence, H2 was supported, which means empowering leadership significant towards affective commitment. With respect to the relationship between psychological empowerment and work, engagement H3 was positively significant with values (β = 0.280, t = 3.990, p < 0.000). Thus, H3 was supported which indicated that psychological empowerment is positively related to work engagement. Regarding H4, the relationship between affective commitment and work engagement was significant with values (β = 0.301, t = 4.881, p < 0.000). Hence, H4 was supported, that mean affective commitment is significant towards work engagement.

Table 4. Discriminant validity via HTMT

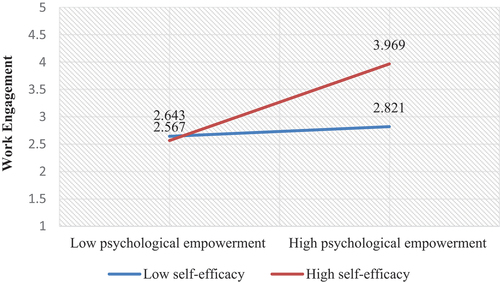

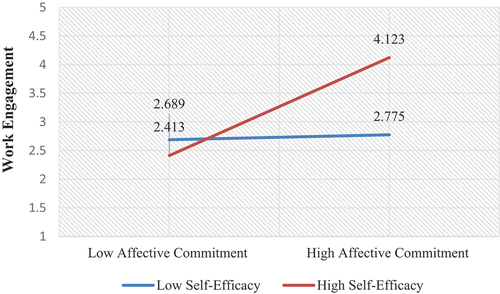

To test moderation prediction in H5 and H6, according to the results in Table , there is a significant among psychological empowerment and self-efficacy interaction effect towards work engagement (β = 0.149, t = 2.988, p < 0.001). Also, self-efficacy positively moderated the relationship between affective commitment and work engagement (β = 0.299, t = 3.166, p < 0.001). therefore, H5 and H6 were supported, meaning that self-efficacy is augmented the relationship between psychological empowerment and employee work engagement as well as the relationship between affective commitment and work engagement. Therefore, following the instruction of Dawson (Citation2014), was displayed high and low employee self-efficacy regression lines (+1 and − 1 standard deviation from the mean) to explain this interaction. This step indicates that the positive relationship between psychological empowerment and work engagement is stronger (slope is more pronounced) when employee self-efficacy is high rather than low (Figure ). In terms of the relationship between affective commitment and work engagement was greater when employee self-efficacy higher than low (see Figure ).

Table 5. Structural Path analysis: Direct effect

4.3. Assessment of explanatory power

The model yields an R-square value of 0.511 for work engagement -a moderate to substantial effect (Hair et al., Citation2017)- and a value of 0.211 for psychological empowerment and 0.217 for affective commitment (See Table ). In regards to the Stone-Geisser blindfolding sample reuse analysis reveals Q-square values greater than 0, which means that psychological empowerment (Q2 = 0.147), affective commitment (Q2 = 0.221) and work engagement (Q2 = 0.251) are effectively predicted (Hair et al., Citation2017). (See Table ).

Table 6. Structural Path analysis: The interaction effect (Moderation)

Table 7. Explanatory power

5. Discussion

This research aims to add to the body of knowledge by empirically analyzing the effects of empowering leadership, psychological empowerment, and emotional commitment on the work engagement of 375 full-time front-line staff in five-star hotels in Iraq’s northern region, notably Erbil. In addition, the moderating influence of self-efficacy in the relationship between psychological empowerment and affective commitment on work engagement is explored in this research. According to the results, empowerment leadership is linked to psychological empowerment and affective commitment. Besides, psychological empowerment and affective commitment were found to be significantly related to work engagement and the positive relationship between psychological empowerment and affective commitment on work engagement is stronger when self-efficacy is high. This indicates that the managers exhibit empowering leadership in fostering the employees’ feeling of meaningful work, competence, making an impact and self-determination which will positively influence the level of affective commitment and work engagement in order to face the stiff competitiveness of the hospitality industry.

With H1 supported, this study indicates that empowering leadership (EL) has a positive effect on employee psychological empowerment. This finding is consistent with the findings of scholars (Alotaibi et al., Citation2020; Bharadwaja & Tripathi, Citation2021; Fong & Snape, Citation2015; Kundu et al., Citation2018; Tripathi & Bharadwaja, Citation2020). Hence, employees feel empowered when leaders provide support and autonomy (Alotaibi et al., Citation2020). Additionally, with H2 supported, it indicates that empowering leadership has a positive influence on affective commitment, which is supported by previous studies (Bharadwaja & Tripathi, Citation2021; Kim & Beehr, Citation2018; Laschinger et al., Citation2009). Empowering leaders that emphasize employee autonomy, participation, and growth through self-direction (Dewettinck & van Ameijde, Citation2011) will increase employees’ affective connection to the company. This is because enabling leaders who foster staff motivation and efficacy while also encouraging employee participation in work processes will elicit pleasant experiences and emotions, resulting in emotional connection to and involvement in the organization (Meyer & Allen, Citation1997). Furthermore, H3 was supported showing that psychological empowerment was positively related to work engagement which is consistent with the findings of previous studies (Alotaibi et al., Citation2020; Moura et al., Citation2015; Wang & Liu, Citation2015). Hence, employees will be engaged in a work environment that offers them more psychological meaningfulness of being empowered particularly when they are more psychologically available (Kahn, Citation1990). With H4 being supported, affective commitment was also found to be positively related to work engagement which is consistent with the findings of previous studies (Asif et al., Citation2019; Gupta et al., Citation2016; van Gelderen & Bik, Citation2016). The finding suggests that when the employees expect and believe that their organization is committed to supporting their career needs, they feel obligated to reciprocate this commitment by giving their commitment to the organization (Blau, Citation1964; Gouldner, Citation1960) in order to sustain their self-image of being those who settle their indebtedness to their organizations (Eisenberger et al., Citation2001).

With H5 and H6 supported, this study also confirms the moderating role of self-efficacy on the relationship of psychological empowerment and affective commitment on work engagement such that the positive relationship between psychological empowerment and affective commitment on work engagement is stronger when self-efficacy is high. This finding is consistent with the view that employees with higher self-efficacy make continuous endeavors to reach their goals and to achieve their organizations’ objectives (Mulki & Jaramillo, Citation2011; Munir et al., Citation2016).

5.1. Theoretical implications

Firstly, this study has theoretically contributed to the increasing body of literature on self-efficacy by empirically demonstrating the moderating role of self-efficacy in strengthening the relationships between psychological empowerment and work engagement as well as between affective commitment and work engagement. Prior studies have shown the buffering role of self-efficacy in the stressor-strain relationship (Naeem et al., Citation2020; Nauta et al., Citation2010), this study, therefore, provides additional empirical evidence on how self-efficacy could strengthen the impact on positive organizational outcomes such as work engagement in this study. Secondly, this study has theoretically contributed to the growing body of literature on empowerment leadership theory by demonstrating the positive roles of empowerment leadership and structural empowerment on elevating affective commitment and work engagement; thus, substantiating and enriching the empowerment leadership theory. The study also demonstrates that the empowerment leadership theory supports the moderating role of self-efficacy. Thirdly, apart from the empowerment leadership theory, this study also helped advance the empowerment leadership literature by examining its outcomes in the hospitality industry. It showcases the applicability of empowerment leadership and psychological empowerment in driving positive outcomes in organizations.

5.2. Managerial implications

In regard to the first managerial implication of this study. In suggestions to initiate empowerment leadership, hotels should hire and train leaders who are willing to empower their subordinates how to empower their subordinates (Kundu et al., Citation2018; Srivastava et al., Citation2006). Additionally, such leaders also provide coaching and emotional support to their subordinates in order to empower them (Kundu et al., Citation2019). Thus, empowered leaders delegate responsibility to their employees and enable them to control important decisions, and show faith in their workers’ capacity to do their professions. These leaders motivate their teams to develop professionally and personally to their full potential. The employees will comprehend this. In a marketplace, everybody should succeed.

In regard to the importance of psychological empowerment aspects in the workplace. Initially, psychological empowerment indicates an “intrinsic task motivation reflecting a sense of self-control in relation to one’s work and an active engagement with one’s work role. According to studies, businesses have discovered that psychological empowerment can successfully increase people’s enthusiasm for their jobs (e.g., Tharanganie & Perera, Citation2021). Therefore, hotel management should focus on psychological empowerment as a significant key as it gives front-line employees the power and responsibility to make decisions is known as employee empowerment. Giving your sales and service employees the freedom to make decisions can boost morale and enhance customer service when it comes to handling issues. For affective commitment describes how individuals can display affection and commit to their organization because they believe it upholds similar values to their own. The emotional involvement one has with their employer might improve work happiness. Affective commitment occurs when the employee desires to be committed to a specific goal. For instance, if a worker has a high level of affective commitment to the organization, then they have a pleasant association with the group and are further probable to stay (Asif et al., Citation2019). Hence, within a business, commitments offer significant advantages. These help employees prioritize and plan respective tasks, and they provide them with a distinctly high level of dedication also an inspiration to continue at their work.

Another important implication is that managers should view self-efficacy as an asset and therefore nurture self-efficacy among their subordinates due to its stress-buffering role (Nauta et al., Citation2010). This study has demonstrated the ability of self-efficacy in strengthening the relationship between psychological empowerment and work engagement as well as between affective commitment and work engagement. Zhou et al. (Citation2018) recommended organizations to nurture an organizational climate that encourages employees to build their self-confidence in order to generate higher self-efficacy (Al Halbusi et al., Citation2020). One suggestion to build higher confidence among employees is that managers should demonstrate empathy and concern towards their subordinates (Tu & Lu, Citation2016). It means that managers should show genuine interest and listen empathetically to work-related issues raised by employees and have open-door communication with subordinates to demonstrate that they care about their subordinates. Meanwhile, in order to develop higher self-efficacy among employees, organizations should provide extensive skills development training to employees and allow employees to participate in goal setting to elevate their self-efficacy.

Overall, the findings of this research benefit Iraqi and global economic practitioners and policymakers in addressing problems relating to the region’s and Iraq’s economy. People who make use of the hotel business spend money in retail stores, restaurants, entertainment venues, and other places. The improvement of regional infrastructure can also be financed in part by the hospitality industry. A country’s infrastructure is developed, its revenue is increased, and a sense of cultural interaction between locals and visitors has been established thanks to tourism. In numerous locations, tourism generates a sizable number of employees (Al Halbusi et al., Citation2021; Al-Wattar et al., Citation2019). The generation of revenue, employment, and foreign exchange earnings are three objectives that are of utmost importance to emerging economies. This is the most significant economic element of operations associated with the tourism sector.

5.3. Limitations and suggestions for future research

This study, like every study, has limitations. To begin with, the responses were confined to front-line employees working in five-star hotels, thus the findings cannot be applied to employees working in other types of hotels in the hotel industry. It would also be interesting to investigate whether the findings vary across different categories of hotels; therefore, it is suggested that future studies should extend the samples to other categories of hotels to gain further insights. Second, the sample area is limited to northern Iraqi provinces, and the findings’ applicability to other locations is worthy to be examined in future studies. Future studies can perhaps extend the model to other countries (both developed and developing countries) with different cultural settings to explore the applicability of the research model in those countries. Third, because this is a cross-sectional study, it can only be used to infer the link between the variables, not causality. Future studies may consider a longitudinal study where it would be easier to understand how organizational incentives affect employees’ work engagement. Finally, future studies may investigate other moderating variables specifically on individual differences in the relationships among the relationships in this research model. For instance, it would be interesting to explore whether personality variables such as grit and proactive personality play a role in elevating higher work engagement in a multi-group analysis study.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study investigated the effects of empowering leadership, psychological empowerment, and affective commitment on the work engagement of 375 full-time front-line staff in five-star hotels in northern Iraq, specifically Erbil. In addition, the moderating influence of self-efficacy in the relationship between psychological empowerment and affective commitment on work engagement is investigated in this study. According to the results, empowerment leadership is linked to psychological empowerment and affective commitment. Furthermore, psychological empowerment and affective commitment have been demonstrated to be strongly connected to work engagement, with a stronger positive relationship between psychological empowerment and affective commitment on work engagement when self-efficacy is higher. This suggests that managers use empowering leadership to promote employees’ feelings of meaningful work, competence, impact, and self-determination, all of which will have a favourable impact on the level of affective commitment and work engagement needed to succeed in the hospitality sector.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the Qatar National Library (QNL) for providing the Open Access funding for this work.

Disclosure statement

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Afthanorhan, A., Awang, Z., Abd Majid, N., Foziah, H., Ismail, I., Al Halbusi, H., & Tehseen, S. Gain more Insight from common Latent Factor in structural equation modeling. (2021). Journal of Physics Conference Series, 1793(1), 012030. IOP Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1793/1/012030

- Alarcon, G. M., & Edwards, J. M. (2011). The relationship of engagement, job satisfaction and turnover intentions. Stress and Health, 27(3), e294–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1365

- Al Halbusi, H., & Amir Hammad Hamid, F. (2018). Antecedents influence turnover intention: Theory extension. Journal of Organizational Behavior Research, 3(2), 287–304.

- Al Halbusi, H., Jimenez Estevez, P., Eleen, T., Ramayah, T., & Hossain Uzir, M. U. (2020). The roles of the physical environment, social servicescape, Co-created value, and customer satisfaction in determining tourists’ citizenship behavior: Malaysian cultural and creative industries. Sustainability, 12(8), 3229. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083229

- Al Halbusi, H., Ruiz-Palomino, P., Jimenez-Estevez, P., & Gutiérrez-Broncano, S. (2021). How upper/middle managers’ ethical leadership activates employee ethical behavior? The role of organizational justice perceptions among employees. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.652471

- Al Halbusi, H., Ruiz-Palomino, P., Morales-Sánchez, R., & Abdel Fattah, F. A. M. (2021). Managerial ethical leadership, ethical climate and employee ethical behavior: Does moral attentiveness matter? Ethics & Behavior, 31(8), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2021.1937628

- Al Halbusi, H., Tang, T. L. P., Williams, K. A., & Ramayah, T. (2022). Do ethical leaders enhance employee ethical behaviors? Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 11(1), 105–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-022-00143-4

- Al Halbusi, H., Williams, K. A., Mansoor, H. O., Hassan, M. S., & Hamid, F. A. H. (2020). Examining the impact of ethical leadership and organizational justice on employees’ ethical behavior: Does person–organization fit play a role?. Ethics & Behavior, 30(7), 514–532.

- Alotaibi, S. M., Amin, M., & Winterton, J. (2020). Does emotional intelligence and empowering leadership affect psychological empowerment and work engagement? Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 41(8), 971–991. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-07-2020-0313

- Al Otaibi, S. M., Amin, M., & Winterton, J. (2022). The role of empowering leadership and psychological empowerment on nurses’ work engagement and affective commitment. International Journal of Organizational Analysis. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-11-2021-3049

- Al-Riyami, A., & Dollard, M. F. (2020). Affective commitment as a mediator between empowering leadership and job outcomes: A study in the middle East. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(17), 2200–2223. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1474312

- Al-Wattar, Y. M. A., Almagtome, A. H., & Al-Shafeay, K. M. (2019). The role of integrating hotel sustainability reporting practices into an Accounting Information System to enhance hotel Financial performance: Evidence from Iraq. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism & Leisure, 8(5), 1–16.

- Amundsen, S., & Martinsen, L. (2015). Linking empowering leadership to job satisfaction, work effort, and creativity: The role of self-leadership and psychological empowerment. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 22(3), 304–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051814565819

- Asif, M., Qing, M., Hwang, J., & Shi, H. (2019). Ethical leadership, affective commitment, work engagement, and creativity: Testing a multiple mediation approach. Sustainability, 11(16), 4489. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164489

- Bakker, A. B., & Albrecht, S. L. (2018). Work engagement: Current trends. Career Development International, 23(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-11-2017-0207

- Bakker, A. B., & Bal, M. P. (2010). Weekly work engagement and performance: A study among starting teachers. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(1), 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X402596

- Bakker, A. B., & Leiter, M. (2017). Strategic and proactive approaches to work engagement. Organizational Dynamics, 46(2), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2017.04.002

- Bandura, A. (1986a). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

- Bandura, A. (1986b). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 4(3), 359–373. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359

- Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90022-L

- Bandura, A., & Schunk, D. H. (1981). Cultivating competence, self-efficacy, and intrinsic interest through proximal self-motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41(3), 586. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.41.3.586

- Bester, J., Stander, M., & van Zyl, L. E. (2015). Leadership empowering behaviour, psychological empowerment, organizational citizenship behaviours and turnover intention in a manufacturing division. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 41(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v41i1.1215

- Bharadwaja, M., & Tripathi, N. (2020). Linking empowering leadership and job attitudes: The role of psychological empowerment. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 15(1), 110–127. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABS-03-2020-0098

- Bharadwaja, M., & Tripathi, N. (2021). Linking empowering leadership and job attitudes: The role of psychological empowerment. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 15(1), 110–127. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABS-03-2020-0098

- Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley.

- Breevaart, K., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., Sleebos, D. M., & Maduro, V. (2014). Uncovering the Underlying Relationship Between Transformational Leaders and Followers. Task Performance. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 13(4), 194–203. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000118

- Brislin, R. W. (1980). Cross-cultural research methods: Strategies, problems, applications. In I. Altman, A. Rapoport, & J. F. Wohlwill (Eds.), Human Behavior and Environment (pp. 47–82). Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0451-5_3

- Carmeli, A. (2003). The relationship between emotional intelligence and work attitudes, behavior and outcomes: An examination among senior managers. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(8), 788–813. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940310511881

- Chaudhry, N., Javed, B., Rasheed, A., & Zaman, S. (2021). Empowering leadership and organizational commitment: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 633950. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633950

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

- Dawson, J. F. (2014). Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7

- Dehghanpour, A., Jafarnejad, A., & Bahrami, M. A. (2022). The effect of affective commitment on employee job satisfaction and turnover intention. Modern Applied Science, 16(2), 45–56.

- Dewettinck, K., & van Ameijde, M. (2011). Linking leadership empowerment behaviour to employee attitudes and behavioural intentions: Testing the mediating role of psychological empowerment. Personnel Review, 40(3), 284–305. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483481111118621

- Dirks, K. (2023). Enhancing work engagement through leadership and organizational interventions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 109(1), 125–138.

- Eisenberger, R., Armeli, S., Rexwinkel, B., Lynch, P. D., & Rhoades, L. (2001). Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.42

- Erez, M., & Arad, R. (1986). Participative goal setting: Social, motivational, and cognitive factors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(4), 591–597. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.4.591

- Fong, K. H., & Snape, E. (2015). Empowering leadership, psychological empowerment and employee outcomes: Testing a multi‐level mediating model. British Journal of Management, 26(1), 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12048

- Ghaderi, Z., Tabatabaei, F., Khoshkam, M., & Shahabi Sorman Abadi, R. (2021). Exploring the role of perceived organizational Justice and organizational commitment as Predictors of job satisfaction among employees in the Hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 24(3), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2021.1988882

- Gomes, G. P., Ribeiro, N., & Gomes, D. R. (2022). The Impact of Burnout on Police Officers’ Performance and Turnover Intention: The Moderating Role of Compassion Satisfaction. Administrative Sciences, 12(3), 92.

- Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092623

- Grant, A. M., Dutton, J. E., & Rosso, B. D. (2008). Giving commitment: Employee support programs and the prosocial sensemaking process. Academy of Management Journal, 51(5), 898–918. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2008.34789652

- Gupta, V., Agarwal, U. A., & Khatri, N. (2016). The relationships between perceived organizational support, affective commitment, psychological contract Breach, organizational citizenship behaviour and work engagement. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(11), 2806–2817. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13043

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A Primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2d ed.). Sage.

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. European Journal of Marketing, 53(4), 566–584. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-10-2018-0665

- Hassan, M. S., Ariffin, R. N. R., Mansor, N., & Al Halbusi, H. (2021a). The moderating role of Willingness to Implement Policy on Street-level Bureaucrats’ Multidimensional Enforcement style and Discretion. International Journal of Public Administration, 46(6), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2021.2001008

- Hassan, M. M., Jambulingam, M., Alagas, E. N., Uzir, M. U. H., & Halbusi, H. A. (2020). Necessities and ways of combating dissatisfactions at workplaces against the job-Hopping Generation Y employees. Global Business Review, 0972150920926966. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150920926966

- Hassan, M. S., Raja Ariffin, R. N., Mansor, N., & Al Halbusi, H. (2021). An examination of Street-level Bureaucrats’ Discretion and the moderating role of Supervisory support: Evidence from the field. Administrative Sciences, 11(3), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11030065

- Hassan, M. S., Raja Ariffin, R. N., Mansor, N., & Al Halbusi, H. (2021b). An Examination of Street-Level Bureaucrats’ Discretion and the Moderating Role of Supervisory Support: Evidence from the Field. Administrative Sciences, 11(3), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11030065

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New challenges to international marketing (Vol. 20, pp. 277–319). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Hulland, J., Baumgartner, H., & Smith, K. M. (2018). Marketing survey research best practices: Evidence and recommendations from a review of JAMS articles. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46(1), 92–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0532-y

- Ismael, F., & Yesiltas, M. (2020). Sustainability of CSR on organizational citizenship Behavior, work engagement and job satisfaction: Evidence from Iraq. Revista de Cercetare si Interventie Sociala, 71, 212–249. https://doi.org/10.33788/rcis.71.15

- Jiang, Q., Lee, H., & Xu, D. (2020). Challenge stressors, work engagement, and affective commitment among Chinese public servants. Public Personnel Management, 49(4), 547–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091026020912525

- Joo, B.-K., Lim, D. H., & Kim, S. (2016). Enhancing work engagement: The roles of psychological capital, authentic leadership, and work empowerment. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 37(8), 1117–1134. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-01-2015-0005

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. https://doi.org/10.2307/256287

- Karatepe, O. M., Karadas, G., Azar, A. K., & Naderiadib, N. (2013). Does work engagement mediate the effect of polychronicity on performance outcomes? A study in the hospitality industry in northern Cyprus. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism, 12(1), 52–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332845.2013.723266

- Kim, M., & Beehr, T. A. (2018). Empowering leadership: Leading people to be present through affective organizational commitment? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(16), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1424017

- Knezovic, E., & Musrati, M. A. (2018). Empowering leadership, psychological empowerment and employees’ creativity: A gender perspective. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity & Change, 4(2), 51–72.

- Kundu, S. C., Kumar, S., & Gahlawat, N. (2018). Empowering leadership and job performance: Mediating role of psychological empowerment. Management Research Review, 42(5), 605–624. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-04-2018-0183

- Laschinger, H. K. S., Finegan, J., & Wilk, P. (2009). Context matters: The impact of unit leadership and empowerment on nurses’ organizational commitment. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 39(5), 228–235. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181a23d2b

- Liang, H., & Scott, B. A. (2020). The effect of job resources on work engagement: The moderating role of affective commitment. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(7), 655–669.

- Li, Y., Li, X., & Liu, Y. (2021). How Does high-performance work system prompt job crafting through autonomous motivation: the moderating role of initiative climate. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 384.

- Li, Y., & Scott, B. A. (2023). The moderating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between affective commitment and work engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 96(1), 215–234.

- Lu, X., Xie, B., & Guo, Y. (2018). The trickle-down of work engagement from leader to follower: The roles of optimism and self-efficacy. Journal of Business Research, 84, 186–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.11.014

- Manz, C. C. (1986). Self-leadership: Toward an expanded theory of self-influence processes in organizations. The Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 585–600. https://doi.org/10.2307/258312

- Martínez-Martínez, A., Cegarra-Navarro, J. G., Garcia-Perez, A., & Wensley, A. (2019). Knowledge agents as drivers of environmental sustainability and business performance in the hospitality sector. Tourism Management, 70, 381–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.08.030

- Ma, Y., Zeng, Z., Li, Y., & Bai, W. (2020). Empowering leadership and employee performance: The moderating role of affective commitment. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 608612. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.608612

- Memon, M., Ting, H., Ramayah, T., Chuah, F., & Cheah, J. (2017). A review of the methodological misconceptions and guidelines related to the application of structural equation modeling: A Malaysian scenario. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling, 1(1), i–xiii. https://doi.org/10.47263/JASEM.1(1)01

- Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

- Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and application. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452231556

- Moura, D., Orgambídez-Ramos, A., & de Jesus, S. N. (2015). Psychological empowerment and work engagement as predictors of work satisfaction: A sample of hotel employees. Journal of Spatial and Organizational Dynamics, 3(2), 125–134.

- Mulki, J. P., & Jaramillo, F. (2011). Workplace isolation: Salespeople and supervisors in USA. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(4), 902–923. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.555133

- Munir, Y., Sadiq, M., Ali, I., Hamdan, Y., & Munir, E. (2016). Workplace isolation in pharmaceutical companies: Moderating role of self-efficacy. Social Indicators Research, 126(3), 1157–1174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0940-7

- Naeem, M., Weng, Q. D., Ali, A., & Hameed, Z. (2020). Linking family incivility to workplace incivility: Mediating role of negative emotions and moderating role of self-efficacy for emotional regulation. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 23(1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12391

- Nauta, M. M., Liu, C., & Li, C. (2010). A cross-national examination of self-efficacy as a moderator of autonomy/job strain relationships. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 59(1), 159–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00375.x

- Pearce, C. L., Sims, H. P., Jr., Cox, J. F., Ball, G., Schnell, K. A., Smith, K. A., & Trevino, L. (2003). Transactors, transformers and beyond: A multi-method development of a theoretical typology of leadership. Journal of Management Development, 22(4), 273–307. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710310467587

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Putra, E. D., Cho, S., & Liu, J. (2017). Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation on work engagement in the hospitality industry: Test of motivation crowding theory. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 17(2), 228–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358415613393

- Rabiul, M. K., Karatepe, O. M., Al Karim, R., & Panha, I. M. (2023). An investigation of the interrelationships of leadership styles, psychological safety, thriving at work, and work engagement in the hotel industry: A sequential mediation model. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 113, 103508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2023.103508

- Rabiul, M. K., Patwary, A. K., & Panha, I. M. (2022). The role of servant leadership, self-efficacy, high performance work systems, and work engagement in increasing service-oriented behavior. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 31(4), 504–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2022.1990169

- Rabiul, M. K., Shamsudin, F. M., Yean, T. F., & Patwary, A. K. (2023). Linking leadership styles to communication competency and work engagement: Evidence from the hotel industry. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 6(2), 425–446. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-09-2021-0247

- Rabiul, M. K., & Yean, T. F. (2021). Leadership styles, motivating language, and work engagement: An empirical investigation of the hotel industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, 102712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102712

- Rhoades, L., Eisenberger, R., & Armeli, S. (2001). Affective commitment to the organization: The contribution of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 825. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.825

- Rich, B. L., Lepine, J. A., & Crawford, E. R. (2022). Job engagement: Antecedents, consequences, and mechanisms. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(1), 75–96.

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J.-M. (2018). SmartPLS 3, Retrieved December 30, 2018 from. http://www.smartpls.com

- Saks, A. M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(7), 600–619. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940610690169

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross- national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

- Singh, M., & Sarkar, A. (2012). The relationship between psychological empowerment and innovative behavior. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 11(3), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000065

- Sipe, L. J. (2021). Towards an experience innovation canvas: A framework for measuring innovation in the hospitality and tourism industry. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 22(1), 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2018.1547240

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1992). When Organizations Dare: The Dynamics of Psychological Empowerment in the Workplace, [ Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation], University of Michigan.

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465. https://doi.org/10.2307/256865

- Srivastava, A., Bartol, K. M., & Locke, E. A. (2006). Empowering leadership in management teams: Effects on knowledge sharing, efficacy, and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 49(6), 1239–1251. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.23478718

- Teng, C. C., Hsu, S. M., Lai, H. S., & Chen, H. (2020). Exploring ethical incidents in the Taiwanese hotel industry. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 21(4), 422–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2018.1511496

- Tharanganie, M. G., & Perera, G. D. N. (2021). The role of psychological empowerment on human resource-related performance outcomes among Generation Y employees in the hotel industry in Sri Lanka. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism, 20(3), 368–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332845.2021.1923916

- Tripathi, N., & Bharadwaja, M. (2020). Empowering leadership and psychological health: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Employee Responsibilities & Rights Journal, 32(3), 97–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-020-09349-9

- Tsaur, S. H., & Hsieh, H. Y. (2020). The influence of aesthetic labor burden on work engagement in the hospitality industry: The moderating roles of employee attributes. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 45, 90–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.07.010

- Tsaur, S. H., Hsu, F. S., & Lin, H. (2019). Workplace fun and work engagement in tourism and hospitality: The role of psychological capital. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 81, 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.03.016