Abstract

Drawing on the transaction cost analysis perspective, this study examines how three types of exchange risks influence performance in exporter-importer exchange relationships. These risks include cultural distance, which gives rise to behavioral uncertainty and its associated measurement problem; market turbulence, a dimension of environmental uncertainty that gives rise to an adaptation problem; and transaction-specific assets, representing a safeguarding problem. The conceptual model assesses how an informal governance mechanism, inter-organizational trust, responds to these three exchange risks and, in doing so, fosters relational and export performance. Based on a structural equation model conducted in PLS, our findings indicate that cultural distance relates positively to inter-organizational trust, and market turbulence positively relates to exporter-specific assets. Exporter-specific assets and inter-organizational trust were found to have a reciprocal relationship. This research also confirms the mediating role of relational performance concerning the effects of exporter-specific assets and inter-organizational trust on financial export performance.

1. Introduction

Exporters often operate in challenging contexts arising from the higher risks, dynamism, and complexity associated with maintaining international exchange relationships (Bodlaj et al., Citation2017; Leonidou et al., Citation2002, Citation2014). Turbulent export markets are often characterized by rapidly changing buyer preferences, varied buyer demand, and a persistent focus on new market offerings (Srivastava et al., Citation2015). Turbulent export markets thrust the exporters not only to employ finance but may also leave a long-lasting effect on the bilateral exchange relationships. This dreadful context, coupled with the exporter’s need to operate in a culture significantly different from the home country, has the equally hostile possibility to challenge the exporter-importer relationship eventually, the performance.

Exporters took myriad strategic responses to mitigate the risks posed by challenging contexts. International distribution networks represent hybrid forms of transaction governance, given that they are relational exchanges that involve multiple transactions that recur over time. Hence, they represent ongoing processes embedded in historical and socio-cultural contexts surrounding the transactions (Dwyer et al., Citation1987; Granovetter, Citation1992, Citation1995; Heide, Citation1994). For exporters, maintaining long-term relational exchanges with foreign distributors (importers) represents an essential performance and competitive advantage source.

Numerous studies have drawn on Transaction Cost Analysis (TCA) (Williamson, Citation1985, Citation1991), a theoretical framework that has spawned considerable research across many disciplines, including international business, marketing channels, and strategy. TCA argues that firms make discriminating choices about which governance structure to use to facilitate transactions, given the particular exchange risks that may be present. The choice among governance structures includes markets (through competition among current and potential exchange partners), the firm (i.e., full vertical integration), and hybrid or intermediate forms (i.e., ongoing exchange relationships in which specific governance mechanisms can be crafted).

Further, a related framework of relational exchange theory (RET) (Dwyer et al., Citation1987; Gilliland & Bello, Citation2002; Macneil, Citation1980; Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994) has been widely used, wherein researchers have proposed an array of relational variables as governance mechanisms to manage the conditions that may arise in ongoing exchange relationships, whether domestic or international (Bloemer et al., Citation2013; Styles & Ambler, Citation2000; Styles et al., Citation2008). Trust is a relational variable prevalent in many international marketing, marketing channels, and exporting studies. It is a construct that has come to be recognized as an informal governance mechanism in interfirm relationships (Ahamed et al., Citation2015; Heide & John, Citation1990; Kautonen, Citation2006; Skarmeas et al., Citation2008; Wang et al., Citation2019) as well as it is potential to foster favorable strategic and financial outcomes (Ashnai et al., Citation2016; Zaheer et al., Citation1998).

Despite having a rich research tradition of both theoretical streams, several significant research gaps persist. One is that the process by which the cultural context and market turbulence may influence trust and deployment of specific asset investments and, ultimately, financial, relational, and/or strategic performance outcomes have not been fully explicated. Another is the equivocal nature of the relationship of cultural distance with trust and market turbulence with specific asset investments. Still, another is that few studies have provided consistent empirical evidence that relationship performance functions as an antecedent of export performance (O’Toole & Donaldson, Citation2002). Responding to these gaps, we constructed an integrated model of “context-strategic response-performance” that shows how exchange risk context can affect trust and investment in specific assets, as well as their ability to manage exchange risks and enhance performance. In particular, we examine the role of perceived cultural distance and market turbulence relative to inter-organizational trust and exporter-specific assets and two dimensions of performance, i.e., relational performance and financial export performance.

Furthermore, this study took place in a rarely studied national context, i.e., a developing nation. Many of the empirical studies found in the exporter-importer, international business, and marketing channels literature have been conducted in countries representing highly developed economies and are especially skewed toward Europe, Asia, and North America (Aykol & Leonidou, Citation2018; Bianchi & Saleh, Citation2011; Samiee & Chirapanda, Citation2019; Tesfom et al., Citation2004). We test our proposed model with data from exporters located in the Latin American country of Ecuador, a research setting where limited little empirical evidence has been generated (Fastoso & Whitelock, Citation2011).

In the next section, we present our model, its embedded hypotheses, and the theoretical rationale for each. Following that, we summarize our data collection methods, operational measures, and methods used to evaluate data quality. Next are the results of our substantive analysis. We conclude by discussing our findings, theoretical and managerial implications, limitations, and directions for future research.

2. Theory and hypothesis development

2.1. Perceived cultural distance

Foreignness-induced problems are issues that firms face when entering foreign markets (Obadia, Citation2013). Zaheer and Venkatraman (Citation1995, p. 341) asserts that foreignness issues result from the “unfamiliarity of the [foreign] environment, from cultural, political and economic differences and the need for coordination across geographic distance.” Research on foreignness and cultural issues in international business studies has yielded inconsistent results (Papadopoulos et al., Citation2011; Zanger et al., Citation2008). Culture refers to transmitted patterns of values, ideas, and other symbolic systems that distinguish the members of one group or category of people from another and shape individual members’ beliefs, assumptions, expectations, attitudes, and behaviors (Hofstede, Citation1991; Kroeber & Kluckhohn, Citation1952). Thus, the perceptions and behaviors of export-import exchange partners will likely vary according to their respective national, industry, and organizational cultures and prior experience with firms from other countries.

In studies of foreignness that use psychic or cultural distance constructs, the terms often appear interchangeably (Sousa & Bradley, Citation2006), creating conceptual confusion and inconsistencies. More precisely, psychic distance, also known as perceived cultural distance, is a managerial perception that comprises the sum of differences between the home and foreign markets in terms of “culture, language, legal and economic systems, business practices, and other country-level factors” (Katsikeas et al., Citation2009, p. 138). Although some studies apply psychic distance as a national-level phenomenon, individual or organizational-level analyses are more appropriate because these perceptions constitute the subjective interpretations of the reality of key informants. Hence, psychic distance does not influence each person or organization similarly (Sousa & Bradley, Citation2006). Psychic distance can also impede export-import relationship performance because these dyads often lack common cultural values, social norms, and business practices, leading to communication difficulties, misunderstandings, incomplete contracts, and increased transaction costs (Ahamed & Skallerud, Citation2013; Dow & Ferencikova, Citation2010; Karunaratna et al., Citation2001; Luo, Citation2002; North et al., Citation2017; Park et al., Citation2018; Simonin, Citation1999).

How cultural distance influences export performance and the underlying processes remain poorly understood. Reflecting what has become known as the paradox of cultural distance, a growing number of studies provide evidence that greater cultural distance enhances performance (Chakrabarti et al., Citation2009; Evans & Mavondo, Citation2002; Hu & Chen, Citation1996; Morosini et al., Citation1998; O’Grady & Lane, Citation1996; Park et al., Citation2018). Similarly, Lui et al. (Citation2006) posit that trust may partially or fully mediate cultural distance’s influence on performance. Moreover, conflicting views exist about the direct effect of cultural distance (or theoretically similar constructs) on trust i.e., some researchers (e.g., Obadia, Citation2013) have depicted it as a negative antecedent, whereas others (e.g., Zhang et al., Citation2003) predict a positive impact of cultural distance on trust.

Reflecting the perspective of TCA theory, cultural distance can be construed as a factor that gives rise to behavioral uncertainty (Azar & Drogendijk, Citation2016), which can evoke monitoring or performance evaluation problems (John & Reve, Citation2010; Rindfleisch & Heide, Citation1997). On the one hand, the lack of shared cultural values, social norms, and business practices may impede communication, so cultural distance will impede an exporter’s ability to monitor its partner. On the other hand, despite potential monitoring difficulties, the cultural distance could motivate exporters to develop closer relationships with their exchange partners, reflected in pledges to signal a desire for continuity. In close exchange relationships marked by greater trust, information sharing, collaborative efforts, joint decision-making, and greater reliance on self-monitoring by exchange partners become more feasible (Bhatti et al., Citation2020).

2.2. Market turbulence

Environmental uncertainty is an exogenous factor vital in inter-organizational relationships and outcomes (Palmatier et al., Citation2007). It has been conceptualized as “the difficulties in effectively planning for future conditions concerning international buyer-seller operations, caused by both the diversity (i.e., the existence of multiple external factors which need to be considered when making decisions) and dynamism (i.e., changes in the external factors over time) associated with the external environment” (Leonidou et al., Citation2006, p. 578). According to the TCA perspective, environmental uncertainty gives rise to an adaptation problem, such that contingencies might not be foreseen, making them difficult to address contractually at the outset of a transaction. Appropriate responses may become apparent only as events transpire (John & Reve, Citation2010; Rindfleisch & Heide, Citation1997). This situation provides firms with a powerful motivation to seek flexibility, as might be achieved through relational exchange mechanisms.

Several studies provide empirical evidence of the positive influences of relational variables (e.g., commitment, trust, interdependence, relational norms) on relational exchange outcomes in conditions of high uncertainty (Cannon et al., Citation2000; Palmatier et al., Citation2007). In particular, environmental uncertainty may manifest in the form of market turbulence, which is a function of market volatility and heterogeneity and captures the extent to which markets are fragmented, as well as the frequency with which customers’ preferences and compositions change (Kohli & Jaworski, Citation1990; Srivastava et al., Citation2015). When market turbulence is greater, firms cannot accurately monitor and respond to market demand, or forecast market trends accurately. Consequently, it motivates them to seek more environmental information (Mason & Staude, Citation2009). One way for exporters to do so is to draw closer to an importer exchange partner to benefit from its market knowledge and environmental scanning efforts.

2.3. Transaction specific assets

When one party commits to specific investments dedicated to a particular exchange partner, transaction-specific assets (specialized or dedicated investments) are created (Heide & John, Citation1990; Williamson, Citation1985). For example, an exporter may tailor its end product, manufacturing line and/or logistics processes to deal with a particular importer and the market it serves. While such investments are usually made intentionally because of their productive nature, exporters may use them to gain better terms or more effective marketing efforts from importers, as such specialized assets can also be viewed as a pledge or bond that signals commitment (Rindfleisch & Heide, Citation1997; Stump & Joshi, Citation1999; Williamson, Citation1985).

The essence of specific investments is that they represent both switching costs (Porter, Citation1980) and a hold-up potential. At the onset of an exchange relationship with a particular importer, the exporter may have multiple importers who are viable alternatives for one another. However, once specific investments have been committed, the buying situation becomes fundamentally transformed (Williamson, Citation1985), i.e., the exporter’s ability to turn to other importers is effectively curtailed for the duration of that transaction. Consequently, specific investments create a safeguarding problem (Heide & John, Citation1990) since they evoke a need to protect their value from opportunistic appropriation by the importer to whom they are dedicated. This is because specific investments cannot be costlessly or easily be redeployed for use with another exchange partner without their value becoming severely reduced should the transaction be terminated prematurely (Williamson, Citation1985). A contractual (formal) or organizational (bureaucratic and/or relational) safeguarding mechanism can sometimes be incorporated into ongoing exchange relationships by exporters (Wathne & Heide, Citation2000; Williamson, Citation1985). Such mechanisms provide a means to impose social control (Vanneste, Citation2016) by inhibiting opportunistic behaviors and/or promoting pro-social behaviors and the continuance of the exchange relationship.

2.4. Trust

Trust has long been a topic of interest across many disciplines, including economics, marketing, organizational behavior, strategic management, and international business studies (Bodlaj et al., Citation2017; Luo, Citation2002; Mayer et al., Citation1995; Zhong et al., Citation2017). Trust is among the most researched constructs in the export marketing literature (Bloemer et al., Citation2013). Critics argue that the theory of trust is still developing (e.g., Seppänen et al., Citation2007) and that this construct has been vaguely measured (Ellis & Shockley‐Zalabak, Citation2001). A recent literature review revealed more than 40 conceptualizations of trust (Bodlaj et al., Citation2017), particularly concerning its definition, dimensionality, and direction. Because the trust construct draws on multiple theories from various disciplines, it has been conceptualized and operationalized in divergent ways, leading to mixed findings and limited explanatory power (Bodlaj et al., Citation2017; Ganesan & Hess, Citation1997; Zhong et al., Citation2017). Several researchers assume that a concise and universally accepted definition does not yet exist (Mayer et al., Citation1995,; Zhong et al., Citation2017). Although several conceptualizations of the multidimensional nature of trust exist, the trust construct is often operationalized as a more abstract, unidimensional phenomenon (Ganesan & Hess, Citation1997; Moorman et al., Citation1992; Rempel et al., Citation1985). Trust, too, has been conceptualized as a bidirectional phenomenon (i.e., both partners must trust and be trusted to engage in mutually beneficial exchanges), yet it typically is conceptualized and measured as a unidirectional phenomenon (Bodlaj et al., Citation2017; Korsgaard et al., Citation2015). Despite these many conceptualizations, the trust literature tends to agree on several key aspects: vulnerability, reliance on another, and confidence that the vulnerability will not be exploited (Mayer et al., Citation1995; Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994; Sabel, Citation1993). To build trust, channel members and end users must be confident that the other party will not exploit their vulnerabilities; furthermore, it facilitates cooperative behaviors that are crucial for inter-organizational communication (Bloemer et al., Citation2013; Doney & Cannon, Citation1997; Dyer & Chu, Citation2000; Ganesan & Hess, Citation1997; Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994; Zhong et al., Citation2017). At the outset of an exchange relationship, trust takes on more of a calculative nature based on qualification efforts that assess the proposed partner’s capabilities and motivation to perform (Stump & Heide, Citation1996) and the expected future benefits and costs of transacting (Poppo et al., Citation2016). Thereafter, the development of trust entails a learning process, usually through interactions that enable partners to learn about each other’s trustworthiness and the value of trusting (Bodlaj et al., Citation2017). In effect, trust is a function of both the past behaviors of the exchange partners and their expectations of the future. Partners in a trusting relationship likely sense betrayal if the counterpart’s behaviors or performance fail to meet expectations (Ashnai et al., Citation2016; Zaheer et al., Citation1998). Thus, trust is central to all exchange relationships and represents one of the core dimensions of relationship quality (Leonidou et al., Citation2006, Citation2014; Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994; Styles et al., Citation2008). Besides focusing on the conceptual nature of trust, the extant literature also encompasses this construct’s antecedents and consequences (Lui et al., Citation2006). In this study, we focus on the inter-organizational dimension of trust (Zaheer et al., Citation1998), which they define as “ … the extent to which there is a collectively-held trust orientation by organizational members toward the partner firm” (p. 143).

2.5. Export performance

A plethora of indicators exist to measure export performance (Zou & Stan, Citation1998). In a recent review, Chen et al. (Citation2016) found export performance operationalized in 53 different ways, with nearly half of these measures used only once or twice. Economic measures appear to dominate all available measures of export performance. Despite the glut of operational measures, several comprehensive export performance measurement frameworks have been proposed, albeit with varying dimensions and categories and associated limitations (Carneiro et al., Citation2007). For example, the widely cited EXPERF scale (Zou & Stan, Citation1998) incorporates three dimensions: financial export performance (export profits, export sales, and export sales growth), strategic export performance (contribution of the export venture to the firm’s competitiveness, strategic position, and market share), and satisfaction with export performance (perceived success of the venture, satisfaction with the venture, and degree to which the venture meets expectations). Katsikeas et al. (Citation2000) distinguish economic (i.e., sales-, profit-, and market share-related), non-economic (i.e., product- and market-related and miscellaneous), and generic measures of export performance. Sousa’s (Citation2004) categorization of export performance measures consists of sales, profit, market-related, general, and miscellaneous indicators. However, these measures have rarely included relationship performance, despite calls to include it as an indicator of export performance (e.g., O’Toole & Donaldson, Citation2002).

Relationship performance stems from a specific set of non-financial export performance measures that seek to assess inter-organizational relational dynamics attributed to a focal exchange partner (e.g., level of efficiency, productivity, contribution toward achieving financial goals) (Luo et al., Citation2015; O’Toole & Donaldson, Citation2002). Relationship performance can be defined as the perceived economic performance of a particular dyad within a broader network of exchange relationships as compared to expectations (Medlin, Citation2003). This can significantly impact on sales growth, market position, marketing support, or qualified services. By leveraging a partner’s capabilities and resources, successful inter-organizational relationships can enhance firms’ financial performance.

2.6. Relationships among perceived cultural distance, market turbulence, exporter specific assets, and interorganizational trust

Perceived cultural distance is a generalized managerial perception that tends to be based on stereotypes, anecdotes, cultural norms, socialization, or media reports, more so than on first-hand experience—unlike an inter-organizational trust, which is largely based on experience and specific to the exchange relationship. The influence of national culture on individual and organizational behavior is well documented in the international marketing literature, as are its implications for trust development and efficacy (Atuahene-Gima & Li, Citation2002). Because perceived cultural distance can hinder information flows among the trading parties, limit the effectiveness of contracts (Karunaratna et al., Citation2001), and hinder the development and maintenance of trust (Obadia, Citation2013). A study by Nes et al. (Citation2007) found that cultural distance had a significant adverse effect on trust. Hence, we propose the following:

H1:

Perceived cultural distance will have a negative effect on inter-organizational trust.

We leverage TCA’s conceptual argument that market turbulence represents an adaptation problem (John & Reve, Citation2010; Rindfleisch & Heide, Citation1997), which can be mitigated by shifting toward relational exchange postures. On the one hand, market turbulence could inhibit specific assets since it could be a factor that may lead to the premature termination of an exchange relationship and thus would heighten the risk that the value of specific asset investments will be extinguished. Hence, a negative relationship can be expected. We propose the following hypotheses:

H2:

Market turbulence will have a negative effect on exporter-specific assets.

2.7. Relationship between exporter-specific assets and inter-organizational trust

Drawing on the logic of TCA, market governance is precluded when a safeguarding problem exists. When specific assets are tendered in an ongoing relationship, we can expect that firms will install governance mechanism(s) in ongoing exchange relationships to protect their interests. Several remedies are possible, reflecting market-like mechanisms, such as contracts or hostages (e.g., reciprocal specialized investments), bureaucratic mechanisms (such as monitoring or decision control), or relational mechanisms (such as trust, commitment, and relational norms) (Wathne & Heide, Citation2000; Williamson, Citation1985). At the beginning of an exchange relationship, initial perceptions of reliability and fidelity can be attributed to the reputation of the prospective exchange partner (for example, an importer), recommendations, and the qualifications conducted before selecting the firm (Stump & Heide, Citation1996). Such efforts can provide the confidence to tender specific assets as an inducement, pledge, or signal commitment to an ongoing exchange relationship. Another view holds that inter-organizational trust develops from rational and pragmatic considerations of interfirm adaptations (e.g., specific assets) and inter-organizational learning, as well as other historical aspects of inter-organizational relationships, such as previous transactions, negotiations, or conflicts (Ashnai et al., Citation2016; Dwyer et al., Citation1987; Ford, Citation1980). Thus, the interrelationship between exporter-specific assets and inter-organizational trust can be expected to be reciprocal over time. As such, higher levels of inter-organizational trust can represent confidence about the lack of opportunistic intent by the importer, which can lead to relationship-enhancing behaviors, such as the growth of specific asset investments as the exchange relationship persists. Reflecting our expectation of mutual influence, this leads us to propose: there will be a reciprocal positive effect between exporter-specific assets and inter-organizational trust. More specifically,

H3

(a): Exporter-specific assets are positively related to the inter-organizational trust.

H3

(b) Interorganizational trust is positively related to exporter-specific assets.

2.8. Relationships among interorganizational trust, exporter specific assets and performance

Although trust should generally foster performance, Katsikeas et al. (Citation2009) contend that its relationship with performance is complex and poorly understood. Medlin (Citation2003), argues that perceived economic performance accrues from the efforts of jointly acting relationship parties. Trusting relationships are expected to positively affect performance by promoting productive behaviors, thus increasing the efficiency and economic production potential of firms that engage in such exchanges (Luo et al., Citation2015; Obadia & Vida, Citation2011). In general, trust allows individuals or organizations to accept their vulnerability to others and to make riskier decisions that could lead to superior outcomes (Mayer et al., Citation1995). Trust is generally thought to improve performance because it facilitates critical and sufficient information flows, lowers transaction costs, improves capabilities, and increases strategic flexibility, all of which are not possible in arms-length exchanges (Katsikeas et al., Citation2009; Luo, Citation2002). Despite this conceptual consensus, empirical evidence is divided. For example, Zhang et al. (Citation2003) and Katsikeas et al. (Citation2009) find a positive trust—financial performance relationship, but Aulakh et al. (Citation1996) report an insignificant direct effect. Solberg (Citation2006) and Barnes et al. (Citation2015)) provide evidence that the effect of interfirm trust on financial performance is mediated by interfirm relationship quality, which parallels the notion of relationship performance. A recent meta-analysis by Leonidou et al. (Citation2014) reveals that trust relates positively only to relationship performance, not financial performance. In light of these many arguments and prior findings, we propose the following hypotheses:

H4

(a): Interorganizational trust is positively related to relationship performance

H4

(b): Interorganizational trust is positively related to financial export performance.

H5:

Relationship performance is positively related to financial export performance.

Exporter-specific investments can also be expected to influence both relational performance and financial performance. Such investments are tangible evidence of commitment to the importer and the desire for continuity. They thus can serve as the basis for relationship-building efforts and pro-social behaviors on both sides of the dyad (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994). Furthermore, such investments are thought to be more productive than generalized investments (Stump & Joshi, Citation1999). Thus, we propose these final hypotheses:

H6

(a): Exporter-specific assets are positively related to relationship performance.

H6

(b): Exporter-specific assets are positively related to financial export performance.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and data collection procedures

Our sampling frame was the listed non-oil exporters published by the Ministerio de Comercio Exterior (Ecuadorian Ministry of Foreign Trade). Recent criticisms that export-import studies have been conducted mainly in North America, Europe, and Asia influenced our choice of Ecuador as our country context, along with calls for more research involving firms from developing nations (Aykol & Leonidou, Citation2018; Samiee & Chirapanda, Citation2019) and Latin American firms in particular (Bianchi & Saleh, Citation2020; Fastoso & Whitelock, Citation2011; Paul & Mas, Citation2020). Our data collection procedures followed the World Bank’s data collection protocol for its 2017 Enterprise Survey (World Bank Enterprise Survey, Citation2017). Data were obtained using a telephone survey conducted by an independent call center rather than relying on a mail or internet survey. The former was not considered feasible because of the generally low and declining response rates to mail surveys in Latin American countries and Ecuador’s low postal reliability. At the same time, the latter was ruled out, given Ecuador’s low broadband penetration rate. Our data collection involved key informants from exporting firms, who were instructed to respond relative to a single export venture, which helps reduce the potential for systematic or random sources of error (John & Reve, Citation1982; Krause et al., Citation2018). A total of 1,330 companies were attempted to be contacted. However, only 985 companies could actually be reached because of incorrect contact information or because they were no longer involved in exporting. Among those contacted, 404 met the screening criteria and agreed to participate. To maintain an ethical data collection practice, we informed the respondents that there were no foreseeable hazards in completing the survey, anonymity was guaranteed, it would only be presented in a summated form, and assured that there would be no commercial uses of the collected data. Our final sample consisted of 142 valid surveys (corresponding to a 14.4% response rate).Footnote1 Although this is a relatively small sample size, it is consistent with previous organizational research (Baruch & Holtom, Citation2008; Krishnan & Poulose, Citation2016). To assess whether nonresponse bias may have been present, we compared the early versus late responses on select demographic and substantive variables (Armstrong & Overton, Citation1977) and performed the homogeneity of variances test (Levene statistic) in SPSS. None of these tests signaled that nonresponse bias threatened this research. To minimize and assess whether common method bias was present (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003) and minimize potential social desirability bias, our data collection methods included assurances of voluntary responses and anonymity, separating the different variable measurements, and counterbalanced question order. Common method bias was determined to be absent based on conducting Harman’s one-factor test (Lindell & Whitney, Citation2001).

3.2. Measurement instruments

The operational measures of the constructs included in our model were based on established English language scales drawn from the extant literature. The initial questionnaire was developed in English. Next, a professional translator translated it from English to Spanish, then back-translated it to English again to check for possible anomalies (Bianchi & Saleh, Citation2020). The questionnaire was then pretested using a group of 20 graduate students from a prominent university (all with experience working for different corporations in Ecuador). The results of this pretest revealed no substantial problems or misunderstandings of the questions. The six latent variables used in this study are measured with 7-point Likert scales adapted from previously published studies. These measurements were already tested in multiple geographical and empirical contexts and were considered sufficient face validity. Perceived cultural distance measures came from a seven-item scale from Papadopoulos et al. (Citation2011). The five items used to measure market turbulence were introduced by Jaworski and Kohli (Citation1993). We developed six items based on previous research to measure asset specificity (Joshi & Stump, Citation1999). We adopted the ten-item scale from Zaheer et al. (Citation1998) to measure inter-organizational trust. Relationship performance was measured by taking four items from Luo et al. (Citation2015). Export financial performance used four items drawn from Lages (Citation2000). In this research, we used the export relationship’s length as the control variable and measured it with the number of years (Heide & Stump, Citation1995).

3.3. Sample profile

The organizations from which we gathered data were mostly empresas medianas y grandes (i.e., medium and large companies), with half of them reporting annual sales exceeding five million USD and 47% in the 1–5 million USD range. These firms employed an average of 191 employees (minimum 4, maximum 1500). On average, these firms had 18 years of exporting experience and relationships with the focal importer of more than 10 years. The key informants represented high managerial levels, including 43% presidents, 16% CFOs, 18% export managers, foreign trade executives, or coordinators. The United States was the main export destination (37%), followed by Colombia (22%), European Union (12.6%), and Russia (9.2%).

4. Analysis and results

4.1. Assessments of measure quality

We tested the validity and reliability of our conceptual model by running a measurement model in SmartPLS-3, following guidelines for structural equation modeling in practice (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988). The measurement model results reveal three inter-organizational trusts and one market turbulence item with loadings below the threshold of 0.50; we, therefore, excluded these items from further analysis and reran the measurement model (Hair et al., Citation2009; Pham & Petersen, Citation2021) (see the for the purified measurement scales). The remaining measurement items all demonstrated convergent validity, as listed in Table .

Table 1. Reliability, convergent and discriminant validity, and Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT ratio)

The average variance extracted (AVE) values exceed the recommended threshold of 0.50, and the shared variance between each pair of the constructs was smaller than the respective AVE, in support of discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Overall, the CFA results confirm the constructs’ unidimensionality and their significant convergent and discriminant validity (Hair et al., Citation2014; Henseler et al., Citation2015).

4.2. Hypotheses tests

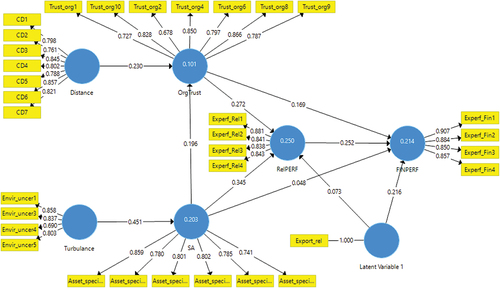

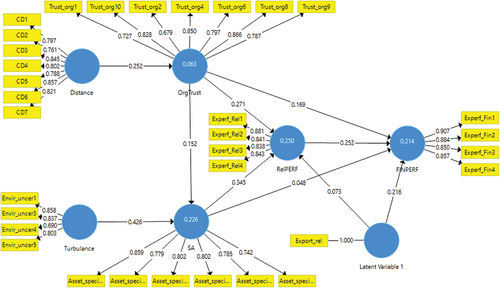

To test the hypothesized relationships, we ran bootstrapping in SmartPLS-3, a resampling technique that estimates the standard error without relying on distributional assumptions (Hair et al., Citation2014). Recall that because H3 portrayed a reciprocal relationship between exporter-specific assets (ESA) and inter-organizational trust (IOT), two parallel models were run, where all paths were identical except the direction between ESA and IOT. Model fit indices and coefficients for paths sharing the same direction were nearly identical in both models. Both sets of model fit indices are displayed in Table , and both models’ parameter estimates (path coefficients) are reported in Figure . All model fit indices are within conventional standards for international marketing and PLS research (Chin, Citation2010; Hair et al., Citation2014; Henseler & Sarstedt, Citation2013; Henseler et al., Citation2016). Hence, we concluded that both versions of our model offer met the requirements to continue examining the path coefficients related to the tests of our hypotheses. Both the analytical model figures and the measurement items are shown in .

Table 2. Model fit indices

With regards to the specific hypotheses, our results showed that for both the models, perceived cultural distance had a significant positive effect on inter-organizational trust (β = 0.23, p < 0.05 [Model A]; 0.25, p < 0.01 [Model B, ]), thus not supporting hypotheses H1. We found a significant positive association between market turbulence and exporter specific assets (β = 0.45, p < 0.01 [A]; 0.43, p < 0.01 [B]), opposing H2. As expected, we found that exporter specific assets exerted a significant, positive effect on inter-organizational trust (H3(a): β = 0.20, p < 0.05 [A]), as well as inter-organizational trust having a significant positive effect on exporter specific assets (H3(b): β = 0.15, p < 0.05 [B]). Interorganizational trust had a significant and positive effect relative to relationship performance (H4(a): β = 0.27, p < 0.01 [A & B]); however, it had no significant effect on financial export performance (H4(b): β = 0.17, p > 0.10 [A & B]).Footnote2 Relationship performance was found to have a significant, positive effect on export financial performance (β = 0.25, p < 0.05), which supported H5. Concerning exporter specific assets, it significantly and positively influenced relationship performance (H6(a): β = 0.35, p ≤0.001), as predicted, but was to found to be nonsignificant influence on financial export (H6(b): β = 0.05, p > .10). The control variable (the length of the inter-organizational relationships) had a significant positive effect on financial export performance (β = 0.22, p ≤0.01) but not on relationship performance (β = 0.07, p > .10.

Figure 2. Three exchange risks model (B).

5. Discussion

Exchange risks exist in varying degrees with any transaction, including the ongoing exchange relationships between exporters and importers. Such risks have performance implications, so discriminating choices of what governance mechanisms to craft into the exchange relationship is critical. This study presented a process model that portrayed how the exchange risks, i.e., those arising from a cultural distance and market turbulence, influence inter-organizational trust and exporter-specific assets and, subsequently, relationship and export financial performance. Previous research has identified cultural distance as an antecedent of trust (Dyer & Chu, Citation2000; Nes et al., Citation2007). However, the prior evidence has been inconsistent; for instance, several researchers (e.g., Ha et al., Citation2004; Zhang et al., Citation2003) have not found any statistically significant effect of national culture on trust. Some researchers even found a negative effect of the distance perceptions on relational variables such as trust (Ahamed & Skallerud, Citation2013). Conversely, the perceived cultural distance could also motivate firms to draw closer to their exchange partners, to facilitate greater market knowledge, gain access to complementary resources, enable richer information exchanges, and mitigate monitoring problems (Bodlaj et al., Citation2017; John & Reve, Citation2010; Rindfleisch & Heide, Citation1997; Shenkar, Citation2001, Citation2012). Given that our results oppose H1, our findings of a positive relationship between cultural distance and inter-organization trust is consistent with the results of Zhang et al. (Citation2003) but contest those of Obadia (Citation2013). Following the logic of TCA, cultural distance represents a source of behavioral uncertainty and thus can contribute to monitoring or performance evaluation problems (John & Reve, Citation2010). Behavioral uncertainties make it difficult to anticipate exchange partners’ actions (Krishnan et al., Citation2006) and detect their propensity to act opportunistically (Wathne & Heide, Citation2000). Cultural distance is apt to foster monitoring problems for various reasons. For example, contractual terms may be interpreted differently, communications may be impeded or misconstrued due to different values, norms, and cultural references on each side, or the ability to communicate with distant importers may rely on media channels that cannot effectively convey common ground or cultural nuances.

Nevertheless, support for the TCA perspective was not found and may represent a limitation of that theoretical framework, at least regarding perceived cultural distance. That is because cultural distance has both negative and positive aspects, or the national context of the exporter may determine the valence. For example, a perspective opposite to TCA is presented by other researchers (e.g., Smith et al., Citation2011), who posit that businesses from less developed countries may find it easier to operate in a developed nation than at home. Thus, the perceived cultural distance may not be regarded as a difficulty to be overcome but instead an opportunity, which could be a basis for bolstering trust. Krishnan et al. (Citation2006) refer to behavioral uncertainties as boundary conditions that enhance the trust—performance relationship. Consequently, one way to manage the behavioral uncertainties caused by cultural distance perceptions is to rely on informal or relational governance mechanisms such as trust, relational norms, or joint decision-making. Thus, the positive effect of cultural distance on inter-organizational trust appears reasonable.

Environmental uncertainty (Krishnan et al., Citation2006), which can result from economic, social, and other conditions beyond the organization’s control, can be challenging to anticipate. Several previous studies also support that environmental uncertainty and specific assets are positively related; for instance, Huo et al. (Citation2018) found the empirical support for 3PL relationships in China. In this sense, market turbulence, as an environmental uncertainty presents an adaptation problem since it restricts contracting efficacy because contingencies and remedies cannot be foreseen and specified from the outset. This factor can also be a condition where exchange partners may seek provisions that would enable or hinder them from being able to turn to alternative trading partners in the future. Arguments for expecting market turbulence to influence exporter-specific assets negatively were posed in H2 since it could lead to premature termination of contracts. However, the non-significant negative results reflected the view that market turbulence could serve as a motivation to seek continuity and lead to signals of this desire through pledges or a bond, such as committing specific asset investments as a means of securing the services of an importer who operates and is knowledgeable about a targeted country market. In turbulent markets, investing in specific assets can reflect that an exporter is seeking greater assurance of continuity with a focal importer; this could be a prudent way to preserve flexibility to respond to future market conditions; our results support the latter perspective.

Exporters may tender specific assets as an inducement to commence an exchange relationship with a particular importer, as a means to secure better terms or marketing efforts, as a signal of commitment to an importer and desire for continuity in the exchange relationship, and/or to restrict their ability to trade with other intermediaries. Interorganizational trust is recognized as developing from rational and pragmatic considerations of interfirm adaptations (i.e., specific assets), inter-organizational learning, and experience (Ashnai et al., Citation2016; Dwyer et al., Citation1987; Ford, Citation1980). Our results suggest that exporter-specific assets provided the foundation for trust development and imply the importer’s absence of any serious opportunistic behaviors, which could be interpreted as acts of betrayal. However, over time, the interrelationship between exporter-specific assets and inter-organizational trust can be expected to be reciprocal. As such, higher levels of inter-organizational trust can represent confidence about the lack of opportunistic intent by the importer, which can lead to the growth of specific asset investments as the exchange relationship persists. Thus, the positive and significant coefficients in both directions between exporter-specific assets and inter-organizational trust support H3(a) &; (b) and our premise of reciprocal causation.

As expected, inter-organizational trust and exporter-specific assets positively affected relationship performance, reflecting support for H4(a) and H6(a), respectively. Both of these factors are relational exchange elements, indicative of a positive climate that can foster cooperation, reciprocal sentiments, and productive efforts by the importer, which is consistent with relationship performance (Styles et al., Citation2008). Relationship performance was found to have a positive and significant effect on export financial performance, which indicates support for H5. Relationship performance captures the inter-organizational relational dynamics attributed to a focal importer, such that successful inter-organizational relationships will also enhance the exporter’s financial performance through more collaborative efforts and effective leverage of the importer’s capabilities and resources (Luo et al., Citation2015; Medlin, Citation2003; O’Toole & Donaldson, Citation2002). While both inter-organizational trust and exporter-specific assets were expected to positively influence export financial performance (H4(b) & H6(b), respectively), neither was supported, which suggests that the influence of inter-organizational trust on financial export performance is fully mediated by relationship performance, which is consistent with the meta-analysis by Leonidou et al. (Citation2014).

6. Implications, limitations, and future research directions

6.1. Theoretical contribution

Despite calls for investigations of channel environments going back decades (e.g., Achrol & Stern, Citation1988), empirical evidence remains limited, especially from the context of developing nations, and often contradictory. In dynamic international business environments, it is imperative that we expand our knowledge of how companies from different parts of the world respond to exchange risks caused by geographical or cultural distances, turmoil due to changing consumer trends, global economic conditions, and even extraordinary events such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Organization theory predicts that how firms respond to their operating environment is crucial for their performance (Perrow, Citation1970). With this research, we have taken a distinct conceptualization inspired by transaction cost analysis theory and focused on three factors (perceived cultural distance, market turbulence, and exporter-specific assets) that embody three different types of exchange risks that exist in international marketing and the manner by which relationship and financial export performance are influenced through the informal, relational governance mechanism of inter-organizational trust. From a theoretical perspective, this study contributes to the extant literature in several ways. One is that we provide new empirical evidence that perceived cultural distance affects inter-organizational trust positively, which gives further credence to the view that this construct has implications for trust development and efficacy (Atuahene-Gima & Li, Citation2002). Rather than being a limiting factor, as indicated by Obadia (Citation2013), the positive relationship found in this study suggests it may motivate exporters to draw closer to their importer exchange partners. Conceivably, when the exporter operates from a developing nation, it may be easier to deal with a foreign intermediary and rely more on relational exchange mechanisms than distributors operating in its home market. We also provide added clarity about how market turbulence influences exporter-specific asset investments, this contribution might be more relevant analyzing exporter-importer relationships during a global economic downturn. Given the positive effect of market turbulence on exporter-specific assets, the logic of relational exchange theory again appears to prevail over that of transaction cost analysis.

6.2. Managerial implications

This research also offers implications for managers and policymakers, especially in less developed countries. Our results suggest that despite the vulnerability of these dedicated investments, exporters are committing transaction-specific assets as a signal of their desire for continuity and a bilateral approach to their exchange relationships. When forward integration is not possible, maintaining ongoing exchange relationships with importers can be an effective strategy to penetrate foreign markets. By establishing an ongoing exchange relationship with importers, exporters can access foreign markets and gain additional knowledge, skills, and resources, expanding revenues and profits (Riddle & Gillespie, Citation2003).

6.3. Limitations and direction for future research

We acknowledge the several limitations of this study and suggest some aspects that future research could address. One is that we focused on a single informal, relational governance mechanism, while future studies could incorporate a broader range of market-like, bureaucratic, and relational governance mechanisms that can be crafted into ongoing exchange relationships between exporters and importers that represent hybrid governance forms. Another is that we collected data from exporting members of exchange dyads, so we lack insights into the importers’ perspective. Researchers could conduct more intensive data collection efforts by including variables representing the perspectives of both exporters and importers using either a single key informant or informants from both sides of the dyad. Still another limitation is our limited ability to generalize from the findings of this study, given that we only collected data from a single country. We also recognize the limitations of employing a cross-sectional design. Thus, while we presented plausible and logical sequences to the variables, we cannot establish causality with certainty. Future research could employ longitudinal data to support time-series analyses that can provide more insights. Future research could also explore the effects of the variables being better represented in a contingent manner. For example, is the relationship between perceived cultural distance and inter-organizational trust the same when the exporter and importer are both operating from developed nations versus when the exporter is from a developing nation? Or, what if the importer is from a developed nation. Another consideration for future studies is whether the performance effects of inter-organizational trust or exporter-specific assets are moderated by cultural distance and/or market turbulence. In conclusion, despite some limitations this study contributes to the transaction cost analysis and export marketing literature by providing new insights into how exchange risks are managed through the relational governance mechanism of inter-organizational trust and its efficacy in promoting relationships and financial export performance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Response rated based on the qualified contacts.

2. Identical beta-coefficient and p-value were found for both Model A and Model B for path coefficients related to H4-a&b, H5, and H6-a&b.

References

- Achrol, R. S., & Stern, L. W. (1988). Environmental determinants of decision-making uncertainty in marketing channels. Journal of Marketing Research, 25(1), 36–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378802500104

- Ahamed, A. J., & Skallerud, K. (2013). Effect of distance and communication climate on export performance: The mediating role of relationship quality. Journal of Global Marketing, 26(5), 284–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2013.830170

- Ahamed, A. J., Stump, R. L., & Skallerud, K. (2015). The mediating effect of relationship quality on the transaction cost–export performance link: Bangladeshi exporters’ perspectives. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 14(2), 152–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332667.2015.1042345

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), 396–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377701400320

- Ashnai, B., Henneberg, S. C., Naudé, P., & Francescucci, A. (2016). Inter-personal and inter-organizational trust in business relationships: An attitude–behavior–outcome model. Industrial Marketing Management, 52, 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.05.020

- Atuahene-Gima, K., & Li, H. (2002). When does trust matter? Antecedents and contingent effects of supervisee trust on performance in selling new products in China and the United States. Journal of Marketing, 66(3), 61–81. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.66.3.61.18501

- Aulakh, P. S., Kotabe, M., & Sahay, A. (1996). Trust and performance in cross-border marketing partnerships: A behavioral approach. Journal of International Business Studies, 27(5), 1005–1032. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490161

- Aykol, B., & Leonidou, L. C. (2018). Exporter-importer business relationships: Past empirical research and future directions. International Business Review, 27(5), 1007–1021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2018.03.001

- Azar, G., & Drogendijk, R. (2016). Cultural distance, innovation and export performance: An examination of perceived and objective cultural distance. European Business Review, 28(2), 176–207. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-06-2015-0065

- Barnes, B. R., Leonidou, L. C., Siu, N. Y., & Leonidou, C. N. (2015). Interpersonal factors as drivers of quality and performance in Western–Hong Kong interorganizational business relationships. Journal of International Marketing, 23(1), 23–49. https://doi.org/10.1509/jim.14.0008

- Baruch, Y., & Holtom, B. C. (2008). Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Human Relations, 61(8), 1139–1160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726708094863

- Bhatti, W. A., Larimo, J., & Servais, P. (2020). Relationship learning: A conduit for internationalization. International Business Review, 29(3), 101694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101694

- Bianchi, C. C., & Saleh, M. A. (2011). Antecedents of importer relationship performance in Latin America. Journal of Business Research, 64(3), 258–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.11.010

- Bianchi, C., & Saleh, M. A. (2020). Investigating SME importer–foreign supplier relationship trust and commitment. Journal of Business Research, 119, 572–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.07.023

- Bloemer, J., Pluymaekers, M., & Odekerken, A. (2013). Trust and affective commitment as energizing forces for export performance. International Business Review, 22(2), 363–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2012.05.002

- Bodlaj, M., Povše, H., & Vida, I. (2017). Cross-border relational exchange in SMEs: The impact of flexibility-based trust on export performance. Journal of East European Management Studies, 22(2), 199–220. https://doi.org/10.5771/0949-6181-2017-2-199

- Cannon, J. P., Achrol, R. S., & Gundlach, G. T. (2000). Contracts, norms, and plural form governance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(2), 180–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070300282001

- Carneiro, J., Rocha, A. D., & Silva, J. F. D. (2007). A critical analysis of measurement models of export performance. BAR-Brazilian Administration Review, 4(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1807-76922007000200002

- Chakrabarti, R., Gupta-Mukherjee, S., & Jayaraman, N. (2009). Mars–Venus marriages: Culture and cross-border M&A. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(2), 216–236. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2008.58

- Chen, J., Sousa, C. M., & He, X. (2016). The determinants of export performance: A review of the literature 2006-2014. International Marketing Review, 33(5), 626–670. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-10-2015-0212

- Chin, W. W. (2010). How to write up and report PLS analyses. In Handbook of partial least squares (pp. 655–690). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-32827-8_29

- Doney, P. M., & Cannon, J. P. (1997). An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 61(2), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299706100203

- Dow, D., & Ferencikova, S. (2010). More than just national cultural distance: Testing new distance scales on FDI in Slovakia. International Business Review, 19(1), 46–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2009.11.001

- Dwyer, F. R., Schurr, P. H., & Oh, S. (1987). Developing buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298705100202

- Dyer, J. H., & Chu, W. (2000). The determinants of trust in supplier-automaker relationships in the US, Japan and Korea. Journal of International Business Studies, 31(2), 259–285. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490905

- Ellis, K., & Shockley‐Zalabak, P. (2001). Trust in top management and immediate supervisor: The relationship to satisfaction, perceived organizational effectiveness, and information receiving. Communication Quarterly, 49(4), 382–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463370109385637

- Evans, J., & Mavondo, F. T. (2002). Psychic distance and organizational performance: An empirical examination of international retailing operations. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(3), 515–532. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8491029

- Fastoso, F., & Whitelock, J. (2011). Why is so little marketing research on Latin America published in high quality journals and what can we do about it? International Marketing Review, 28(4), 435–449. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651331111149967

- Ford, D. (1980). The development of buyer‐seller relationships in industrial markets. European Journal of Marketing, 14(5/6), 339–353. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000004910

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. In: Sage Publications Sage CA.

- Ganesan, S., & Hess, R. (1997). Dimensions and levels of trust: Implications for commitment to a relationship. Marketing Letters, 8(4), 439–448. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007955514781

- Gilliland, D. I., & Bello, D. C. (2002). Two sides to attitudinal commitment: The effect of calculative and loyalty commitment on enforcement mechanisms in distribution channels. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30(1), 24–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/03079450094306

- Granovetter, M. (1992). Economic institutions as social constructions: A framework for analysis. Acta Sociologica, 35(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/000169939203500101

- Granovetter, M. (1995). Coase revisited: Business groups in the modern economy. Industrial and Corporate Change, 4(1), 93–130. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/4.1.93

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

- Ha, J., Karande, K., & Singhapakdi, A. (2004). Importers’ relationships with exporters: Does culture matter? International Marketing Review, 21(4/5), 447–461. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651330410547135

- Heide, J. B. (1994). Interorganizational governance in marketing channels. Journal of Marketing, 58(1), 71–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299405800106

- Heide, J. B., & John, G. (1990). Alliances in industrial purchasing: The determinants of joint action in buyer-supplier relationships. Journal of Marketing Research, 27(1), 24–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379002700103

- Heide, J. B., & Stump, R. L. (1995). Performance implications of buyer-supplier relationships in industrial markets: A transaction cost explanation. Journal of Business Research, 32(1), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(94)00010-C

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Henseler, J., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Goodness-of-fit indices for partial least squares path modeling. Computational Statistics, 28(2), 565–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00180-012-0317-1

- Hofstede, G. (1991). Management in a multicultural society. Malaysian Management Review, 26(1), 3–12.

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hu, M. Y., & Chen, H. (1996). An empirical analysis of factors explaining foreign joint venture performance in China. Journal of Business Research, 35(2), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(95)00087-9

- Huo, B., Ye, Y., Zhao, X., Wei, J., & Hua, Z. (2018). Environmental uncertainty, specific assets, and opportunism in 3PL relationships: A transaction cost economics perspective. International Journal of Production Economics, 203, 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.01.031

- Jaworski, B. J., & Kohli, A. K. (1993). Market orientation: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Marketing, 57(3), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299305700304

- John, G., & Reve, T. (1982). The reliability and validity of key informant data from dyadic relationships in marketing channels. Journal of Marketing Research, 19(4), 517–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378201900412

- John, G., & Reve, T. (2010). Transaction cost analysis in marketing: Looking back, moving forward. Journal of Retailing, 86(3), 248–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2010.07.012

- Joshi, A. W., & Stump, R. L. (1999). The contingent effect of specific asset investments on joint action in manufacturer-supplier relationships: An empirical test of the moderating role of reciprocal asset investments, uncertainty, and trust. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27, 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070399273001

- Karunaratna, A. R., Johnson, L. W., & Rao, C. (2001). The exporter-import agent contract and the influence of cultural dimensions. Journal of Marketing Management, 17(1–2), 137–159. https://doi.org/10.1362/0267257012571492

- Katsikeas, C. S., Leonidou, L. C., & Morgan, N. A. (2000). Firm-level export performance assessment: Review, evaluation, and development. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(4), 493–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070300284003

- Katsikeas, C. S., Skarmeas, D., & Bello, D. C. (2009). Developing successful trust-based international exchange relationships. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(1), 132–155. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400401

- Kautonen, T. (2006). Trust as a governance mechanism in inter-firm relations—conceptual considerations. Evolutionary and Institutional Economics Review, 3(1), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.14441/eier.3.89

- Kohli, A. K., & Jaworski, B. J. (1990). Market orientation: The construct, research propositions, and managerial implications. Journal of Marketing, 54(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299005400201

- Korsgaard, M. A., Brower, H. H., & Lester, S. W. (2015). It isn’t always mutual: A critical review of dyadic trust. Journal of Management, 41(1), 47–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314547521

- Krause, D., Luzzini, D., & Lawson, B. (2018). Building the case for a single key informant in supply chain management survey research. The Journal of Supply Chain Management, 54(1), 42–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12159

- Krishnan, R., Martin, X., & Noorderhaven, N. G. (2006). When does trust matter to alliance performance? Academy of Management Journal, 49(5), 894–917. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.22798171

- Krishnan, T., & Poulose, S. (2016). Response rate in industrial surveys conducted in India: Trends and implications. IIMB Management Review, 28(2), 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iimb.2016.05.001

- Kroeber, A. L., & Kluckhohn, C. (1952). Culture: A critical review of concepts and definitions. Papers, 47(1– viii), 223. Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology, Harvard University.

- Lages, L. F. (2000). A conceptual framework of the determinants of export performance: Reorganizing key variables and shifting contingencies in export marketing. Journal of Global Marketing, 13(3), 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1300/J042v13n03_03

- Leonidou, L. C., Barnes, B. R., & Talias, M. A. (2006). Exporter–importer relationship quality: The inhibiting role of uncertainty, distance, and conflict. Industrial Marketing Management, 35(5), 576–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2005.06.012

- Leonidou, L. C., Katsikeas, C. S., & Hadjimarcou, J. (2002). Executive insights: Building successful export business relationships: A behavioral perspective. Journal of International Marketing, 10(3), 96–115. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.10.3.96.19543

- Leonidou, L. C., Samiee, S., Aykol, B., & Talias, M. A. (2014). Antecedents and outcomes of exporter–importer relationship quality: Synthesis, meta-analysis, and directions for further research. Journal of International Marketing, 22(2), 21–46. https://doi.org/10.1509/jim.13.0129

- Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.114

- Lui, S. S., Ngo, H.-Y., & Hon, A. H. (2006). Coercive strategy in interfirm cooperation: Mediating roles of interpersonal and interorganizational trust. Journal of Business Research, 59(4), 466–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.09.001

- Luo, Y. (2002). Building trust in cross-cultural collaborations: Toward a contingency perspective. Journal of Management, 28(5), 669–694. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630202800506

- Luo, Y., Liu, Y., Yang, Q., Maksimov, V., & Hou, J. (2015). Improving performance and reducing cost in buyer-supplier relationships: The role of justice in curtailing opportunism. Journal of Business Research, 68(3), 607–615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.08.011

- Macneil, I. R. (1980). The new social contract. Yale University Press.

- Mason, R. B., & Staude, G. (2009). An exploration of marketing tactics for turbulent environments. Industrial Management & Data Systems.

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. https://doi.org/10.2307/258792

- Medlin, C. J. (2003). Relationship performance: A relationship level construct. IMP conference proceedings, In I. Snehota & R. Fiocca (Eds.), Proceedings of the 19th Annual IMP Conference: 2003 (Lugano, Switzerland.) (pp. 1–13).

- Moorman, C., Zaltman, G., & Deshpande, R. (1992). Relationships between providers and users of market research: The dynamics of trust within and between organizations. Journal of Marketing Research, 29(3), 314–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379202900303

- Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299405800302

- Morosini, P., Shane, S., & Singh, H. (1998). National cultural distance and cross-border acquisition performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 29(1), 137–158. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490029

- Nes, E. B., Solberg, C. A., & Silkoset, R. (2007). The impact of national culture and communication on exporter–distributor relations and on export performance. International Business Review, 16(4), 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2007.01.008

- North, C., O’Donnell, E., & Marsh, L. (2017). The economics of trust in buyer-seller relationships: A transaction cost perspective. Global Journal of Management and Marketing, 1(1), 81.

- Obadia, C. (2013). Foreigness-induced cognitive disorientation. Management International Review, 53(3), 325–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-012-0149-9

- Obadia, C., & Vida, I. (2011). Cross-border relationships and performance: Revisiting a complex linkage. Journal of Business Research, 64(5), 467–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.03.006

- O’Grady, S., & Lane, H. W. (1996). The psychic distance paradox. Journal of International Business Studies, 27(2), 309–333. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490137

- O’Toole, T., & Donaldson, B. (2002). Relationship performance dimensions of buyer-supplier exchanges. European Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management, 8(4), 197–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0969-7012(02)00008-4

- Palmatier, R. W., Dant, R. P., & Grewal, D. (2007). A comparative longitudinal analysis of theoretical perspectives of interorganizational relationship performance. Journal of Marketing, 71(4), 172–194. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.71.4.172

- Papadopoulos, N., Martín, O. M., Sousa, C. M., & Lages, L. F. (2011). The PD scale: A measure of psychic distance and its impact on international marketing strategy. International Marketing Review, 28(2), 201–222. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651331111122678

- Park, H., Han, K., & Joon, W. (2018). The impact of cultural distance on the performance of foreign subsidiaries: Evidence from the Korean market. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies, 9(1), 123–134. https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2018.10.00007

- Paul, J., & Mas, E. (2020). Toward a 7-P framework for international marketing. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 28(8), 681–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2019.1569111

- Perrow, C. B. (1970). Organizational analysis: A sociological view. Brooks/Cole.

- Pham, H. S. T., & Petersen, B. (2021). The bargaining power, value capture, and export performance of Vietnamese manufacturers in global value chains. International Business Review, 30(6), 101829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2021.101829

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Poppo, L., Zhou, K. Z., & Li, J. J. (2016). When can you trust “trust”? Calculative trust, relational trust, and supplier performance. Strategic Management Journal, 37(4), 724–741. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2374

- Porter, M. E. (1980). Industry structure and competitive strategy: Keys to profitability. Financial Analysts Journal, 36(4), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v36.n4.30

- Rempel, J. K., Holmes, J. G., & Zanna, M. P. (1985). Trust in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49(1), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.49.1.95

- Riddle, L. A., & Gillespie, K. (2003). Information sources for new ventures in the Turkish clothing export industry. Small Business Economics, 20(1), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020252606058

- Rindfleisch, A., & Heide, J. B. (1997). Transaction cost analysis: Past, present, and future applications. Journal of Marketing, 61(4), 30–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299706100403

- Sabel, C. F. (1993). Studied trust: Building new forms of cooperation in a volatile economy. Human Relations, 46(9), 1133–1170. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679304600907

- Samiee, S., & Chirapanda, S. (2019). International marketing strategy in emerging-market exporting firms. Journal of International Marketing, 27(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069031X18812731

- Seppänen, R., Blomqvist, K., & Sundqvist, S. (2007). Measuring inter-organizational trust—a critical review of the empirical research in 1990–2003. Industrial Marketing Management, 36(2), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2005.09.003

- Shenkar, O. (2001). Cultural distance revisited: Towards a more rigorous conceptualization and measurement of cultural differences. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(3), 519–535. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490982

- Shenkar, O. (2012). Beyond cultural distance: Switching to a friction lens in the study of cultural differences. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(1), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.42

- Simonin, B. L. (1999). Transfer of marketing know-how in international strategic alliances: An empirical investigation of the role and antecedents of knowledge ambiguity. Journal of International Business Studies, 30(3), 463–490. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490079

- Skarmeas, D., Katsikeas, C. S., Spyropoulou, S., & Salehi-Sangari, E. (2008). Market and supplier characteristics driving distributor relationship quality in international marketing channels of industrial products. Industrial Marketing Management, 37(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2007.04.004

- Smith, M., Dowling, P. J., & Rose, E. L. (2011). Psychic distance revisited: A proposed conceptual framework and research agenda. Journal of Management & Organization, 17(1), 123–143. https://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.2011.17.1.123

- Solberg, C. A. (2006). Relational Drivers, Controls and Relationship Quality in Exporter–Foreign Middleman Relations. In C. Arthur Solberg (Ed.), Relationship Between Exporters and Their Foreign Sales and Marketing Intermediaries (Advances in International Marketing (Vol. 16, pp. 81–105). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-7979(05)16004-9

- Sousa, C. M. (2004). Export performance measurement: An evaluation of the empirical research in the literature. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 9(12), 1–23.

- Sousa, C. M., & Bradley, F. (2006). Cultural distance and psychic distance: Two peas in a pod? Journal of International Marketing, 14(1), 49–70. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.14.1.49

- Srivastava, P., Srinivasan, M., & Iyer, K. N. (2015). Relational resource antecedents and operational outcome of supply chain collaboration: The role of environmental turbulence. Transportation Journal, 54(2), 240–274. https://doi.org/10.5325/transportationj.54.2.0240

- Stump, R. L., & Heide, J. B. (1996). Controlling supplier opportunism in industrial relationships. Journal of Marketing Research, 33(4), 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379603300405

- Stump, R. L., & Joshi, A. W. (1999). To be or not to be [locked in]: An investigation of buyers’ commitments of dedicated investments to support new transactions. Journal of Business-To-Business Marketing, 5(3), 33–63. https://doi.org/10.1300/J033v05n03_03

- Styles, C., & Ambler, T. (2000). The impact of relational variables on export performance: An empirical investigation in Australia and the UK. Australian Journal of Management, 25(3), 261–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/031289620002500302

- Styles, C., Patterson, P. G., & Ahmed, F. (2008). A relational model of export performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(5), 880–900. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400385

- Tesfom, G., Lutz, C., & Ghauri, P. (2004). Comparing export marketing channels: Developed versus developing countries. International Marketing Review, 21(4/5), 409–422. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651330410547117

- Vanneste, B. S. (2016). From interpersonal to interorganisational trust: The role of indirect reciprocity. Journal of Trust Research, 6(1), 7–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2015.1108849

- Wang, L., Jiang, F., Li, J., Motohashi, K., & Zheng, X. (2019). The contingent effects of asset specificity, contract specificity, and trust on offshore relationship performance. Journal of Business Research, 99, 338–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.02.055

- Wathne, K. H., & Heide, J. B. (2000). Opportunism in interfirm relationships: Forms, outcomes, and solutions. Journal of Marketing, 64(4), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.64.4.36.18070

- Williamson, O. E. (1985). The economic institutions of capitalism: Firms, markets, relational contracting. The Free Press.

- Williamson, O. E. (1991). Comparative economic organization: The analysis of discrete structural alternatives. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(2), 269–296. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393356

- World Bank Enterprise Survey. (2017), Washington DC, World Bank, available at: Retrieved: February 1, 2018, from https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/3396andhttps://www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/methodology.

- Zaheer, A., McEvily, B., & Perrone, V. (1998). Does trust matter? Exploring the effects of interorganizational and interpersonal trust on performance. Organization Science, 9(2), 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.9.2.141

- Zaheer, A., & Venkatraman, N. (1995). Relational governance as an interorganizational strategy: An empirical test of the role of trust in economic exchange. Strategic Management Journal, 16(5), 373–392. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250160504

- Zanger, C., Hodicová, R., & Gaus, H. (2008). Psychic distance and cross—border cooperation of SMEs: An empirical study on Saxon and Czech entrepreneurs’ interest in cooperation. Journal for East European Management Studies, 13(1), 40–62. https://doi.org/10.5771/0949-6181-2008-1-40