Abstract

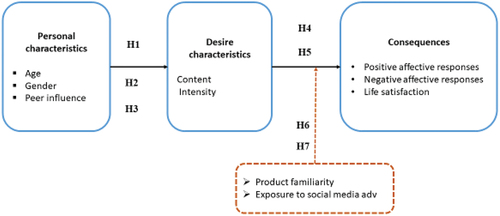

This paper aims to investigate the origins and outcomes of consumer desires in children, with a specific focus on the role of individual attributes (such as age, gender, and susceptibility to peer influence), desire traits (including content and intensity), exposure to social media ads, and familiarity with desired items. This study applies a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches. First, multi-method qualitative study was used to explore the experience of consumption desire among children (collage exercise, focus groups with children and informal surveys with the parents of interviewed children). Subsequently, we conducted an experimental study, surveying 267 school children (aged 7 to 11), to empirically examine how personal and desire traits influence their emotional responses and overall life satisfaction. The results strongly underscore the significant impact of child-specific attributes (age, gender, and peer influence) and desire caracteristics (content and intensity) on consequences generated by the experience of consumption desire among children. Furthermore, our research conclusively affirms the pivotal role of peer influence, familiarity with desired products, and exposure to social media ads in shaping the personal desires of children aged 7 to 11.

1. Introduction

Desires represent a central aspect of human motivation (Bengtsson et al., Citation2021; Boujbel & Et d’Astous, Citation2015; Kozinets et al., Citation2017). They have been studied in several disciplines such as philosophy, psychology and sociology. In the field of consumer behavior, desiring a product or a service is considered as a subjective experience (Kavanagh et al., Citation2005; Kozinets et al., Citation2017; Yi & Jai, Citation2020) that is emotionally ambivalent (Boujbel & Et d’Astous, Citation2015; Ramanathan & Et Williams, Citation2007), likely to generate a combination of pleasant and discomforting emotions (Belk et al., Citation2003; Boujbel et al., Citation2018; Kavanagh et al., Citation2005), and involves the interaction of the heart (emotion) and mind (cognition) (Kavanagh et al., Citation2005; Tangsupwattana & Liu, Citation2018).

In modern society, the role of the child within the family has changed from a “consumer-actor” to a “consumer-decider” who actively participates in the family’s purchasing decisions making process (BenDahmane et al., Citation2021; Brée, Citation2021; Watkins et al., Citation2021). In other words, when a child wants an object, he will try to buy it or have it as a gift from his parents. So, as a result, consumption within the family becomes largely influenced by the child’s desires (Ezan et al., Citation2014; Hoffmann et al., Citation2012; Radesky et al., Citation2020; Watkins et al., Citation2021).

The emergence of consumer desires in children remains a relatively unexplored psychological phenomenon, primarily due to the limited amount of research dedicated to the subject. At present, studies on children’s desires are notably rare, despite the central role of consumer desires as a fundamental element of human motivation, forming at an early stage of development and subsequently shaping consumer preferences. Given the formative nature of these desires and their lasting influence on children’s future consumption behavior, it becomes pertinent to introduce an explanatory framework to elucidate the experience of consumer desire within the specific age bracket of 7 to 11-year-olds. To do so, we will try to explain the emergence and evolution of this experience while studying the factors determining children’s’ behavior during the experience of consumption desire. Within this study, we set out to address the following key inquiries: Q1: Can we establish a comprehensive categorization of consumption desires among children? Q2: How do intrinsic child attributes (such as gender, age, and peer relationships) exert their influence on the nuances of desire (content, intensity, clarity, etc.)? Q3: What is the role played by product familiarity and the exposure to social media advertisements in defining the nature of desire and the consequences generated by the experience of consumption desire among children (affective responses, satisfaction with life, etc.)? To address Q1, our approach encompassed a multifaceted qualitative exploration employing techniques like collage exercises, focus groups involving children, and informal surveys conducted with the parents of the participants. To answer Q2 and Q3 a quantitative study based on survey data collection to 267 school children (aged from 7 to 11) was conducted to test the influence of personal characteristics and desire characteristics on children’s emotional responses and the feeling of satisfaction with their lives.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1. The experience of desire consumption

Consumer desire has been researched in various disciplines such as philosophy, psychology, and sociology. In order to better understand this phenomenon in the field of consumer behavior, we relied on definitions provided by these different disciplines. In philosophy, for example, Platon defined desire as “what we do not have, what we are not and what we are missing to have” (Belk & Llamas, Citation2012). In psychology, desire was defined as “an affectively charged cognitive event in which attention is focused on an object or activity, associated with pleasure or relief from discomfort” (Kavanagh et al., Citation2005). And in sociology, Baudrillard (Citation1998) confirmed that “consumption is an explicit form of desire, it is not essentially linked to the symbolic characteristics of the desired object, but rather to the social signs attached to it” (Holm, Citation1999). Based on these different definitions of consumption desire, several researchers in consumer behavior have tried to characterize this concept. As a result, several definitions have been presented. Desire is defined as “a mixture of primary emotions: love or happiness, and sadness or depression. It is experienced as a) need for something: an object, a state, a relationship, without which life seems incomplete” (Holm, Citation1999). It is also defined as “a powerful cyclical emotion that is both pleasurable and uncomfortable” (Belk et al., Citation2003) (for example when a consumer is hesitating between indulging his desire or controlling it for reasons of social image). From another point, Boujbel and d’Astous (Citation2012) defined the experience of desire “as a subjective, emotionally ambivalent experience that is likely to incorporate a combination of pleasurable and uncomfortable emotions, and involves the interaction of emotions and cognition”. In fact, the consumption desire experience is a subjective experience because it depends on personal perceptions (Bengtsson et al., Citation2021; Yi & Jai, Citation2020). What is desired by a consumer may not be desired by another (Belk & Llamas, Citation2012). Also, desires are not experienced in the same way by all consumers; they vary enormously in their content, intensity, complexity and duration from one consumer to another. However, all kinds of things can be desired, from the most trivial to the most important. In other words, we can desire objects, goods or services, or we can desire to live certain experiences. Consumer desires are very diverse. Depending on the financial costs they generate, desires can be classified as small desires (everyday, inexpensive desires that generally mark moments in the day), intermediate desires (slightly more expensive) and large desires (buying a house, taking a trip, etc.) (Boujbel & Et d’Astous, Citation2015). It can be banal or complicated; easily accessible or difficult to have; a real passion or an obsession (d’Astous & Deschênes, Citation2005). The consumption desire experience is also ambivalent. As a result, the experience of desire can create a situation of ambivalence for the consumer who will choose either to satisfy his personal desire or to abandon it. This ambivalence can generate a combination of pleasant and uncomfortable emotions (Boujbel et al., Citation2018; Kavanagh et al., Citation2005). Campbell (Citation1987), for example, describes the desire to consume as a state of pleasant discomfort. Desiring a product or a service can be pleasurable as well as unpleasant to the extent that, the consumer finds himself unable to satisfy his desire. This inability may be due to religious, moral, social, or material constraints (Boujbel & Et d’Astous, Citation2015). Sometimes having consumption desires is like a battle between emotion (feelings) and cognition (rational thinking) (Boujbel et al., Citation2018). In some situations, consumers can have experiences where the heart and brain are in conflict. For example, when a consumer desires a luxury product, he faces a dilemma: satisfying his desire or saving his money for other priorities.

2.2. Consumption desire as a phenomenon of everyday life

Exposed to a consumption society, desiring has become an affirmation of everyday life (Bengtsson et al., Citation2021; Boujbel & Et d’Astous, Citation2015; Hoffmann et al., Citation2012; Kozinets et al., Citation2017; Yi & Jai, Citation2020). Desires are often stimulated by internal sources (personal wishes) and also external sources, including advertising, commercial posts, social media ads, movies, television shows, stories told by others, and the consumption behavior of others (Belk et al., Citation2003; Ezan et al., Citation2014; John, Citation2001; Krupicka, Citation2005; Mishra & Maity, Citation2021; Watkins et al., Citation2021). In general, the relevance of desires in the daily lives of consumers depends on several factors. For example the propensity to desire, the financial resources available to satisfy consumer desires, the impulsive or compulsive nature of the purchase, the sensitivity of the consumer to social influences, etc (Belk & Llamas, Citation2012; Boujbel & Et d’Astous, Citation2015; Boujbel et al., Citation2018; Japutra & Song, Citation2020). From this perspective, Hoffmann et al. (Citation2012) confirm that desire in everyday life can be a continuous drama in which internal factors (such as personality characteristics) set the state of motivation and conflict while external factors (such as the social context, the presence of others with the consumer when desires arise) contribute to how well people manage to resist or satisfy their desires and aspirations.

2.3. Children’s desire for consumption

The child is a consumer who has always aroused the curiosity of researchers, because of the psychological and sociological complexity of his behavior (Brée, Citation2021; John, Citation2001). Since birth, this young consumer has been consuming, mainly motivated by his or her continuous and uncontrollable desires. Therefore, it is necessary to trace the emergence of this psychological phenomenon in order to understand the behavior of the child consumer in the face of his desires. In fact, some researchers have focused on the study of children’s desires, mainly the work of Holm (Citation1999) who defined desire as “a strong and intense emotion that appears from birth and develops over time as the child grows” (Holm, Citation1999, p. 3). To answer our research questions, we will first trace the factors that may define children’s consumption desires, namely age, gender and sensitivity to peers’ influence. Second, we will identify the consequences of satisfying consumption desires on children’s behavior (such as affective responses and satisfaction with life). Finally, we will explore the influence that the variables “familiarity with desired product «and “exposure to social media ads” might have on the process of satisfying the desire in question.

2.4. The hypotheses of the present study

To explain the experience of consumer desire, numerous prior research studies have presented theoretical models (Belk et al., Citation2003; Boujbel & Et d’Astous, Citation2015; d’Astous & Deschênes, Citation2005; Hoffmann et al., Citation2012). These researchers based themselves on the theory of consumption dreams presented by d’Astous and Deschênes (Citation2005). According to this theory, consumer traits (both individual characteristics and those associated with consumer aspirations) exert a significant impact on the emotional and cognitive responses of consumers.

Applied to consumer desires, the theory of consumption dreams has highlighted the relationship between individual consumer characteristics (context of desire, effort expended, financial constraints, propensity to desire, self-esteem, sensitivity to social influence, etc.), the characteristics of the consumer’s desired products and experiences (Content, Emergence of desire, Intensity of desire, Evolution of desire, Clarity of desire, etc.) and the consequences engendered by this experience (Affective and cognitive reactions Pleasure Discomfort Guilt Control, Satisfaction with life, etc.).

In fact, the literature review does not allow us to propose a clear hypothesis about the experience of consumption desire among children. Children’s consumption desires are absent in previous research. So, in order to explore the hidden facets of children’s behavior regarding desires, we opted for a qualitative approach (collage exercise, small-focus groups with the children and informal surveys with the parents of interviewed children). As a first step, and to identify a categorization of children’s desired objects according to their age and gender, a collage exercise was conducted with 36 children aged from 7 to 11. Children were asked to choose images corresponding to the objects they wanted from the magazines distributed. In a second step, we continued our investigation by conducting 6 small focus groups with a total of 25 children. In this research, focus groups seem to be the most relevant method of information collection. Indeed, we seek to understand the definition that children give to their own desires as well as the influence of certain factors (such as family influence, peers, pocket money, familiarity with the desired product, and exposure to advertising on social media) on these desires. According to Brée (Citation2021) to study children’s behavior, focus groups (of 4 to 5 children maximum) seem to be a very interesting way of collecting information. It allows children to use their own words and expressions and while limiting the risk of distraction (Ayadi, Citation2011). The interview guide was developed using the researches of Holm (Citation1999), Belk et al. (Citation2003), Hoffmann et al. (Citation2012) and Boujbel and Et d’Astous (Citation2015). In fact, children were invited to discuss a number of topics including: 1) exploring the nature of desired products or services; 2) identifying sources of influence in determining children’s consumption desires; 3) understanding the emotional and behavioral consequences of getting the desired products or services. Focus groups will allow us to better understand the role played by variables related to children (age, gender, family and sensitivity to the influence of peers) in the definition of their own desires, their intention to acquire the desired object and the emotional and behavioral consequences of the experience of consumption desires among children (affective responses and the feeling of satisfaction with life).

2.5. Ethics statement

At this level, it is worth mentioning that the collage exercise and focus group sessions were conducted after having the agreement of the children desiring to participate in our study as well as the agreement of their parents. In fact, collage exercise and focus group sessions were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim and thematically coded and analyzed. We explained to participants and their parents that participation would be entirely voluntary and that the data would be treated anonymously and confidentially and that it would be used just for research purposes. In fact, studies reported here were conducted according to internationally accepted ethical standards and were reviewed and approved by the University Ethics Committee, and all participants signed informed consent forms before they were enrolled in the study.

According to McNeal (Citation1992), for interviews related to the field of consumption and child behavior, it is appropriate to conduct interviews with parents. So, in a third step, we completed our investigation with an informal survey with a total of 10 parents of children already interviewed. This was done in order to better understand the influence of parents in the description of children’s personal desires).

Through the qualitative study, we were first able to categorize children’s desires. These desires can be divided into five categories: “Video games and high tech products”, “Food products”, “Clothing and accessories”, “Toys” and “Entertainment, travel and other products”. Second, we were able to confirm that the definition of a child’s consumption desires depends mainly on his age, gender, peers and familiarity with the desired products. Then, we found that parents and exposure to social media advertisements can largely influence the choice of objects desired by children. Finally, we identified that the acquisition of a desired product by a child can generate positive affective reactions (fun, joy, and pleasure), negative affective responses (sadness, anxiety, boredom) and also a feeling of satisfaction with life.

From the qualitative study previously conducted, we noted that, as children grow up, their choices become more specific and clear for both girls and boys. This is supported by Krupicka (Citation2005) who confirmed that cognitive, social, and verbal development allow children to be more specific in their choices. In fact, “the nature of desires changes with the stage of cognitive development: the older the child, the more specific and sophisticated the objects desired” (Piaget, Citation1964).

Other researches confirm also that the majority of children feel a desire, but not all are able to use this concept or describe it verbally. A clear definition of consumption desires is only possible with children who are more verbally, mentally and cognitively capable (Ezan et al., Citation2014; John, Citation2001). In other words, as children grow up, they become more capable of forming a preference for one object over another. This ability to analyze desired objects increases when mental, verbal, and social development reach a certain level of maturity. They could so decide which choice to make among a multitude of similar products (Brée, Citation2021; Krupicka, Citation2005). This has led us to propose the following hypothesis:

H1:

The developmental stage of a child (age) influences their consumption desire characteristics.

H1.a:

The developmental stage of a child positively affects the content of their desires. H1.b: The developmental stage of a child positively influences the intensity of their desires.

Based on the results of our qualitative study, we identified a difference between the items desired by boys and those desired by girls. Boys tend to prefer high-tech products and interactive games, while girls prefer clothes and accessories. This difference can be explained by the importance that girls place on their appearance and social image. Indeed, these results converge with those of Kremer (Citation2001) who identified that girls mostly desire objects that express their femininity. Indeed, our results confirm the findings of Brée (Citation2021) who presented the desire to consume as “a vital phenomenon related to the age and sex of the child, which results from his or her massive exposure to the attractive temptations of the world around him or her, and which can provoke a desire to buy”. This conclusion is also confirmed by Holm (Citation1999) who identified a difference between girls and boys in their understanding of the experience of desire. These researchers found that girls are more clear and specific than boys in their responses, and therefore have a better explanation of their desires. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2:

Gender Effects on Consumption Desire Characteristics in Children

H2.a:

Gender exerts a significant influence on the diversity of desire content in children.

H2.b:

Gender plays a role in shaping the intensity levels of desires in children, resulting in discernible variations.

According to the model of brand learning by the child (Brée, Citation2021; Elías Zambrano et al., Citation2021; Ezan et al., Citation2014; Gunter, Citation2015) the child receives information from different socialization agents, which he or she uses in the construction of his or her desires and which will, in turn, influence his or her behavior (the intention to buy the desired product). Indeed, information from parents (family), advertising (media), peers, exposure to the market (money owned by the child) and direct experience with the product determine the interest given to the objects desired by the child (Krupicka, Citation2005; McNeal, Citation1992; Mishra & Maity, Citation2021; Rossiter, Citation2019). The idea is that social influences are important determinants in the process by which consumer desires are formed (Boujbel et al., Citation2018). In other words, the social environment in general plays an important role in how desires are created and how they progress. Hoffmann et al. (Citation2012) postulated that an object is desired not only for its usefulness, but also for the image it helps to project in one’s social environment. For children, consumption desires are primarily guided by their peers especially during preadolescence and adolescence (Bree, Citation1990; Krupicka, Citation2005; Rossiter, Citation2019). From this perspective, Krupicka (Citation2005, p. 58) confirmed that “children’s consumption preferences are dictated by their peer groups and can be explained by both the fear of being excluded and the need for conformity”.

The results of our qualitative study allowed us to highlight the importance of peer influence in defining the objects desired by children. All of the children interviewed wanted to have the same objects as their peers. This can be explained by the fact that children, during the period from 7 to 11 years old, are preoccupied with integrating their environment. They have a need for approval and acceptance by their reference group and are concerned with maintaining a self-image that is synchronized with it (Bree, Citation1990; Krupicka, Citation2005). These findings lead us to propose the following hypotheses:

H3:

The presence of a child’s peer has an impact on his consumption desire characteristics

H3.a:

The presence of a child’s peer has an impact on his desire’s content

H3.b:

The presence of a child’s peer has an impact on his desire’s intensity

Previous studies in psychology have shown that experiences of desire are, in general, charged with cognitive and affective elements (Boujbel & Et d’Astous, Citation2015; Boujbel et al., Citation2018; Kavanagh et al., Citation2005). On an emotional level, consumer desires incorporate and provide a sense of pleasure provided not only by having personal desires, but also by knowing that they can be achieved (Belk et al., Citation2003). Other positive emotions are associated with the experience of consumer desire such as excitement, happiness, joy, fun, nostalgia, etc (Boujbel et al., Citation2018; Boujbel, Citation2009). Negative emotions are also associated with the experience of desire for consumption such as discomfort, disappointment, frustration, sadness, jealousy, etc. These negative emotions are felt when what is expected, hoped for, or desired is not acquired (Belk et al., Citation2003; Boujbel & Et d’Astous, Citation2015).

On the cognitive level, control is the dimension that reflects the cognitive aspect of consumer desires (Boujbel & Et d’Astous, Citation2015; Boujbel et al., Citation2018; Kavanagh et al., Citation2005). Consumer desires generally involve an ambivalence between indulging (satisfying the desire) and holding back (giving up the desire). Consumers always look for a balance between taking control and being controlled by their desired object (Boujbel & Et d’Astous, Citation2015; Boujbel, Citation2009; Baumeister, Citation2002). In addition to the cognitive (control) and affective (pleasure, discomfort, and guilt) responses that accompany the experience of consumption desire, some other consequences can be mentioned such as satisfaction with life, self-esteem, and social recognition (Boujbel & Et d’Astous, Citation2015).

Based on the results of the qualitative study, we were able to identify that the experience of consumption desire generates positive emotions among children such as joy, pleasure and fun. It also generates negative emotions such as boredom, sadness, and anxiety. Other consequences were identified, such as the feeling of satisfaction with one’s life and self-esteem. Indeed, through this study, we seek to understand how the characteristics of personal desire influence the affective and cognitive reactions resulting from the experience of a recent personal desire. Hence, the following hypothesis is:

H4:

The content of children’s personal desire influences consequences generated by the experience of consumption desire.

H4.a:

The content of children’s personal desire influences positive affective responses generated by the experience of consumption desire.

H4.b:

The content of children’s personal desire influences negative affective responses generated by the experience of consumption desire.

H4.c:

The content of children’s personal desire influences the feeling of satisfaction with life generated by the experience of consumption desire.

H5:

The intensity of children’s personal desire influences consequences generated by the experience of consumption desire.

H5.a:

The intensity of children’s personal desire influences positive affective responses generated by the experience of consumption desire.

H5.b:

The intensity of children’s personal desire influences negative affective responses generated by the experience of consumption desire.

H5.c:

The intensity of children’s personal desire influences the feeling of satisfaction with life generated by the experience of consumption desire.

Children tend to refuse to consume products with which they are not familiar (Masserot, Citation2007). This result was confirmed by our qualitative study which found that the majority of interviewed children always seek to acquire objects with which they are familiar. According to Krupicka (Citation2005, p. 24), children’s preferences for certain brands or products can be explained by their familiarity with them. In other words, children may refuse to consume products with which they are not familiar, but a product that is presented in a repeated and familiar way will be more easily accepted by them (Hudders & Cauberghe, Citation2018). For example, “children who see their parents consuming certain food products will tend to develop a mimetic attitude. Hence, a predisposition to consume these products” (Masserot, Citation2007, p. 6). So, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6:

Familiarity with a desired product moderates the relationship between the characteristics of personal desire and the consequences generated by the experience of consumption desire among children.

For children, social media has become an important source of exposure to advertising. Indeed, advertisements on social media have been developed for some time, and have become almost impossible to avoid (Kozinets et al., Citation2017; Mishra & Maity, Citation2021). This strategy of advertising to children is found in various forms (Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, in online video games, interactive sites, wallpapers, etc.). According to the Canadian-based Media Awareness Network, “children are ideal targets for Internet advertisers because they stay online for longer periods of time than adults and participate in a wider range of online activities” (World Health Organization, Citation2020).

Recent researchers found that children’s desires are more likely to be influenced by advertising at the perceptual stage than at the analytic stage. Indeed, children’s judgments at the perceptual stage are more emotional than rational and are more likely to be influenced by advertising messages through social media (colors, music, animation, etc.) (Alruwaily et al., Citation2020; Araújo et al., Citation2017; Brée, Citation2021; Coates & Boyland, Citation2021; Ezan et al., Citation2014; Radesky et al., Citation2020; Watkins et al., Citation2021). This leads us to believe that the preferences of children aged 7 to 11 can be influenced by advertisements specifically social media advertising. Hence our next hypothesis is:

H7:

Children’s exposure to advertisements on social media moderates the relationship between the characteristics of personal desire and the consequences generated by the experience of consumption desire.

Conclusions from our qualitative study as well as the literature findings (Baumeister, Citation2002; Bengtsson et al., Citation2021; Boujbel & d’Astous, Citation2017; Boujbel & Et d’Astous, Citation2015; d’Astous & Deschênes, Citation2005; Hoffmann et al., Citation2012; Kavanagh et al., Citation2005; Krupicka, Citation2005; Yi & Jai, Citation2020), allowed us to propose our conceptual model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Procedure

Through this study, we seek, on one hand, to test the influence of personal characteristics (age, gender and peer influence) on children’s desire characteristics (content, intensity). On the other hand, we want to test the impact of children’s desire characteristics on the consequences that accompany the experience of consumption desire among children. To achieve these objectives, a survey was conducted among a convenience sample of 267 children aged from 7 to 11 to assess the various concepts of the theoretical framework ) and test the hypothesized relations. This was accomplished using a series of mediation analyses performed based on the collected data. The data collection was carried out using a survey containing 16 questions evaluated on a 4-point Likert scale (Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Agree and Strongly Agree) following the recommendations of Brée (Citation2021) and Derbaix et al., (Citation2012). We used similar scales with previous research to make it easier to relate our findings to this research. Indeed, the use of this scale is widely used in kids’ marketing (Brée, Citation2021) (see Table for sample characteristics). To make the survey easier for children, and following the recommendations of Brée (Citation2021) and Derbaix et al., (Citation1997) for collecting data among kids, we have replaced Strongly Disagree by “NO”, Disagree by “NO”, Agree by “yes” and strongly agree by “yes”. We have, also, opted for a design that uses different sizes and colors for the answer boxes. For the positive steps, we used the green color with a small “yes” and a large “yes”. And for the negative steps, we used the red color with a small “NO” and a large “NO” (the same response procedure was used for all scales in the survey questionnaire).

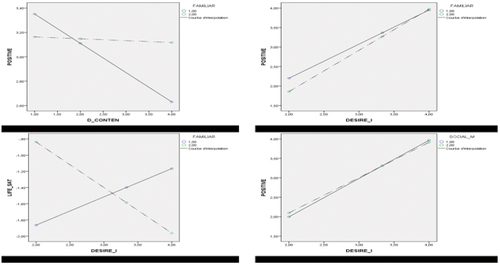

Figure 1. Significant moderation effect of familiarity with desired product and exposure to social media advertisements.

Table 1. Sample characteristics

To obtain the most reliable results possible, we first contacted the schools chosen for our data collection a few months in advance. Then, and in collaboration with the administrations of these schools, we asked for the agreement of the parents of children who wished to participate.

3.2. Measuring instruments

Previous researches studying the experience of consumption desire among children are very limited. This led us to use measurement scales mainly developed for adults (Boujbel & Et d’Astous, Citation2015; Boujbel et al., Citation2018; d’Astous & Deschênes, Citation2005; Hoffmann et al., Citation2012).

Personal desire characteristics were measured through the d’Astous and Deschênes (Citation2005) scale. The affective and cognitive responses that accompany consumption desires were measured with Boujbel and Et d’Astous’s (Citation2015) scale and life satisfaction (Diener et al., Citation1985). In fact, all measurement scales have been adapted to the children’s context through the qualitative study previously conducted (all scales were chosen because of their theoretical relevance for further validation as well as their good psychometric properties and acceptable length).

4. Analysis and results

4.1. Validating the measuring instruments

The examination of the Cronbach’s alpha shows that measurement scales have satisfactory reliability (ranging from 0.739 to 0.948). To examine the reliability and validity of our model, we used two indicators, namely the Rhô of Jöreskog and the Rhô of convergent validity (AVE). Our results show that the Jöreskog Rhô values of our model are good. They exceed the minimum threshold of 0.7 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). The Rhô values of the convergent validity of our measurement model are satisfying, they are between 0.682 and 0.821 exceeding the threshold of 0.5. Discriminant validity is verified for all the constructs (AVE> the square of the correlation between a variable and the rest of the other variables according to Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981) (Table ).

Table 2. Measurements reliability and validity

4.2. Hypothesis testing

The research hypotheses were tested by means of a series of bivariate analyses (Hayes, Citation2018; MacKinnon, Citation2008) using SPSS v.21. Comparisons of means, one-way analyses of variance and correlations were also conducted. Results indicate that H1.a, H2.a, H3.a, H3.b, H4.a, H4.b, H4.c, H5.a and H5.b are validated (results for hypothesis tests are presented in Table ). H1 predicts that the age of the child has a positive impact on consumption desire characteristics (desire content and desire intensity). Our results show that the age of the child has a positive and significant influence only on his desire content (χ2 = 6.541; p = 0.006). Hypothesis H1.a is then validated. The relationship between the kid’s gender and his desire intensity is also positive and significant (F = 1.376; p = 0.015). Therefore, hypothesis H2.a is validated. Our results also confirm that the presence of a child’s peers has an impact on his consumption desire characteristics. In fact, the relationship between peer influence and the desire content is significant (χ2 = 4.454; p = 0.05) (details are presented in Table ) The presence of peers impacts significantly the desire intensity (F = 0.4042; p = 0.054). So that H3.a and H3.b are confirmed. Results of our research showed that the content of children’s personal desires influences the consequences generated by the experience of consumption desire. In fact, desire content has a positive and significant influence on positive affective responses, negative affective responses and satisfaction with life. Hence hypotheses H4.a, H4.b and H4.c are validated. The relationship between the desire content and the child’s affective responses is positively significant.

Table 3. Results for cross tabs

In order to test H5.a and H5.b we used Pearson’s correlation. We found that desire’s intensity was significantly and positively associated with children’s positive affective responses generated by the experience of consumption desire (Pearson’s r = 0.805; p < 0.001), and also with children’s negative affective responses (Pearson’s r = 0.736; p < 0.001) (Table ) H5.a and H5.b are confirmed. However, our results indicate that the desire content has no influence on a child’s life satisfaction (F = 3.689; p = 0.407). H5.c was rejected.

Table 5. Results for hypothesis testing

Table 4. Correlations between intensity of desire and desire’s consequences

4.3. Moderating effects of familiarity with desired products and children’s exposure to advertisements on social media

To test the moderating effect of familiarity with the desired product and children’s exposure to advertisements on social media we used model 1 in PROCESS V.21 by Hayes (Citation2018) with a bootstrap analysis (with 5000 samples). Our results indicated that hypotheses H6 and H7 are supported. First, we identified a moderating effect of familiarity with the desired product on the relation between children’s desire content and positive affective responses (β = 0.225; SE = 0.098; R2 = 0.041; p = 0.023). The familiarity with desired product is moderate, also, the relation between children’s desire intensity and positive affective responses (β = 0.183; SE = 0.088; R2 = 0.658; p = 0.038) and even the relation between children’s desire intensity and satisfaction with life (β = 0.912; SE = 0.370; R2 = 0.674; p = 0.013). Second, our results confirm that children’s exposure to advertisements on social media moderates the relation between children’s desire intensity and positive affective responses (β = 0.077; SE = 0.108; R2 = 0.649; p = 0.047) (for details see Table , Figure ). The acquisition of products already seen on social media generates stronger positive emotions in children than when they simply acquire desired products.

Table 6. Results for moderating effects

5. Discussion

The main objective of this research is to study the influence of specific variables such as age, gender, peer influence, familiarity, and exposure to social media advertisements on the definition of personal desires of children aged from 7 to 11 years. To achieve this objective, we, first carried out a qualitative study (collage exercise, mini focus groups with children, and informal surveys with the parents of the interviewed children). Second, we conducted a quantitative study with a sample of 267 children aged from 7 to 11.

Through the qualitative study, we were able to identify a categorization for children’s desires. These desires can be divided into five categories: “Video games and high-tech products”, “Food products”, “Clothing and accessories”, “Toys” and “Entertainment, travel and other products”. We also, identified that the experience of consumption desire generates among children consequences such as positive affective responses, negative affective responses, and a feeling of satisfaction with life. Results of the qualitative study revealed the importance of peer influence in the definition of desired products or brands by children. All children surveyed wanted to have the same objects as their peers. We have also identified the indirect influence of family and social media advertisements on children’s choices. Parents may not choose the desired object for the child, but they may play a guiding and advisory role. Also, advertisements on social media may not have an immediate effect on children’s choices. However, they can act as a stimulus to remind the child of their desire. Regarding product familiarity, children tend to refuse to consume products with which they are not familiar (Masserot, Citation2007). This result is confirmed by our study where the majority of children surveyed always seek to acquire objects with which they are familiar.

Through the quantitative study, we can confirm three main conclusions. First, a child’s personal characteristics have an important influence on his consumption desire characteristics. In fact, our results show that the variables “age”, “gender” and “peer influence” have a significant impact on the definition of a child’s desire. Our findings are consistent with Brée (Citation2021),and Ezan et al. (Citation2014), who confirmed that children between 7 and 11 have developed the ability to make reasoned choices based on more than a single attribute. In our research, we noticed that, as children grow up, their choices become more precise and clearer for both girls and boys. Those findings confirm the results of Krupicka (Citation2005) according to whom cognitive, social and verbal development allow the child to be more precise in his choices. We also, found a significant difference between the products desired by boys and girls. Boys tend to prefer high tech products and interactive games, while, girls prefer clothes and accessories. This difference can be explained by the importance that girls give to their appearance and social image. Indeed, these results converge with those of Brée (Citation2021) and Ezan et al. (Citation2014) who identified that girls rather desire objects that express their femininity. In fact, the results of our study confirm the findings of Brée (Citation2021) who presented the desire for consumption as a vital phenomenon related to the age and gender of the child. This desire results from massive exposure to the attractive temptations of the world. This can cause as a consequence a desire to purchase a specific product or a brand. Our results confirm the influence of peers on a child’s choices. This converges with the conclusions of Rossiter (Citation2019), Boujbel et al. (Citation2018), Hoffmann et al. (Citation2012) and Krupicka (Citation2005) that children generally want to have the same objects as their peers.

Second, the results of our research confirm the impact of desire characteristics (content and intensity) on the consequences generated by the experience of consumption desire. In fact, the content of desire positively influences positive affective responses, negative affective responses, and satisfaction with life. Those findings are consistent with Boujbel et al. (Citation2018), Boujbel and Et d’Astous (Citation2015), Masserot (Citation2007), and Baumeister (Citation2002).

Third, analyzing results of our research, we can confirm that familiarity with the desired product and children’s exposure to social media advertisements moderate the relationship between children’s desire characteristics and positive affective responses. They, also, moderate the relation between children’s desire characteristics and the feeling of satisfaction with one’s life. This confirms the conclusions of Coates and Boyland (Citation2021), Radesky et al. (Citation2020), Alruwaily et al. (Citation2020), Araújo et al. (Citation2017), Ezan et al. (Citation2014) and Brée (Citation2021) who confirmed that the acquisition of desired products by the children can provoke in them a feeling of satisfaction with life. This feeling is stronger especially when these products are well recognized by child’s peers, they are generally products already seen on social media or already consumed by the child.

6. Conclusion

6.1. Theoretical implications

This study is the first to investigate the desire characteristics and the children’s cognitive and affective responses when they experience consumption desires. The results of this study have several interesting implications. On a theoretical level, this research provides a set of contributions to enrich the existing literature. A conceptual framework for the experience of consumption desires among children aged from 7 to 11 years is proposed and tested. To our knowledge, this is the first research study to present a framework that integrates individual characteristics, the characteristics of children’s desire, and the consequences generated by the experience of consumption desire. On the one hand, this framework allows the presentation of the variables that can be involved in the formation of children’s desires, such as: age, gender, and sensitivity to peer influence. On the other hand, it allowed testing the relationship between these different variables and children’s desires characteristics. In fact, further studies should be undertaken in order to verify if the relationships that were uncovered can be replicated.

6.2. Managerial implications

Children’s consumer desires play an important role in their consumption behavior. These desires serve as motivating factors that influence what children eventually want and buy. From a managerial point of view, recognizing and addressing these desires can be a powerful strategy for driving sales and customer engagement. Additionally, studying and analyzing children’s consumer desires, marketing professionals can gain insight into what interests children and what they are likely to be looking for. This information can help predict their preferences and behaviors.

In addition to age and gender, other variables can also impact children’s consumption desires. These variables could include cultural backgrounds, socio-economic factors, family structures, and trends. By comprehending these influences, businesses can refine their marketing strategies and product offerings to cater to a diverse range of consumer desires. In fact, Understanding children’s consumption desires has direct implications for commercial and advertising management. It enables companies to craft more effective advertising campaigns that speak directly to children’s desires, making the marketing message more compelling and relatable. This can lead to higher engagement, brand loyalty, and sales. As a conclusion, studying and analyzing consumption desires among children aged 7 to 11, along with the various factors influencing these desires, can yield actionable insights for businesses. By adjusting their products and marketing strategies in line with these desires, companies can strengthen their connection with their target audience, increase their customer satisfaction and help their business grow.

6.3. Limits and research perspectives

This study has some limitations that offer opportunities for future research. First, the field exploration allowed us to draw some interesting conclusions, but it was a long and difficult process that required a lot of effort especially with children when administrating surveys. Second, our sample is not large enough to generalize our results. The collage exercise was carried out with 36 children, the mini-focus groups were administered to 25 children and 18 parents and surveys were carried out with 267 children. It would therefore be more interesting to conduct the study with a larger sample. Finally, several difficulties were noted when conducting surveys with children. These difficulties are related to the limited cognitive and expressive capacities of the target group studied. This research demonstrates interesting new lines of inquiry for future research. In this study, we used several data collection techniques that may ensure better validity of the results especially with children (Brée, Citation2021). The results will then be more meaningful if this study is supplemented by more data collection among a larger sample. Also, future research could consider other variables that may affect children’s consumption desires. For example, the influence of brand characters, packaging and direct experience on children’s choices.

Ethics Statement

It is worth mentioning that to obtain the most reliable and ethical results possible, we first contacted the schools chosen for our study a few months in advance. We explained the objectives of our research and the modalities of carrying out our exploration. Then, and in collaboration with the administrations of these schools, we asked for the agreement of parents of children who wished to participate as well as their children (the same procedures were carried out for both the qualitative and quantitative studies). We explained to participants and their parents that participation would be entirely voluntary and that the data would be treated anonymously and confidentially and that it would be used just for research purposes. In fact, studies reported here were conducted according to internationally accepted ethical standards and were reviewed, and all participants signed informed consent forms before they were enrolled in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ayoub Nefzi

Kawther Methlouthi research delves into the intricate realm of child consumer behavior, shedding light on the multifaceted dynamics that influence their choices and preferences. Her research also focuses on understanding the reactions of child consumers to threatening communications.

References

- Alruwaily, A., Mangold, C., Greene, T., Arshonsky, J., Cassidy, O., Pomeranz, J. L., & Bragg, M. (2020). Child social media influencers and unhealthy food product placement. Pediatrics, 146(5). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-4057

- Andréani, J. C., & Conchon, F. (2005). Fiabilité ET Validité Des Enquêtes Qualitatives. UN État DE L’ART EN Marketing. Revue Française du Marketing, 201. https://doi.org/10.3917/mav.015.0156

- Araújo, C. S., Magno, G., Meira, W., Almeida, V., Hartung, P., & Doneda, D. (2017, September). Characterizing videos, audience and advertising in youtube channels for kids. In International Conference on Social Informatics, (pp. 341–16). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-67217-5_21

- Ayadi, K. (2011), « La diffusion des préférences et pratiques alimentaires entre les enfants et les parents » [ Doctoral dissertation] ANRT, Université de Lille 3.

- Baudrillard, J. (1998). Société de consommation: Ses mythes, ses structures (Vol. 53). Sage.

- Baumeister, R. F. (2002). Yielding to temptation: Self-control failure, impulsive purchasing, and consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(4), 670–676. https://doi.org/10.1086/338209

- Belk, R. W., Ger, G., & Askegaard, S. (2003). « the fire of desire: A multisited inquiry into consumer passion». The Journal of Consumer Research, 30(3), 326–351. https://doi.org/10.1086/378613

- Belk, R., & Llamas, R. (2012), The nature and effects of sharing in consumer behavior. Transformative consumer research for personal and collective well-being.625–646. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291907271

- BenDahmane, M., Norchene, B., Joël, E. Muratore, I. (2021). « Une generation immergée dans le numérique ». HAL. https://doi.org/10.3917/ems.bree.2021.01.0379

- Bengtsson, S., Fast, K., Jansson, A., & Lindell, J. (2021). Media and basic desires: An approach to measuring the mediatization of daily human life. Communications, 46(2), 275–296. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2019-0122

- Boujbel, L. (2009). Les dimensions affectives et cognitives des désirs de consommation ( Doctoral dissertation). HEC Montréal.

- Boujbel, L., & d’Astous, A. (2012). Voluntary simplicity and life satisfaction: Exploring the mediating role of consumption desires. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 11(6), 487–494. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1399

- Boujbel, L., & d’Astous, A. (2017). « Marketing et bien-être des consommateurs: une approche intégrant les valeurs de la simplicité volontaire ». Revue Française du Marketing, (260), 43–58.

- Boujbel, L., d’Astous, A., & Kachani, L. (2018). Exploring the psychological mechanisms underlying the cognitive and affective responses to consumption desires. Journal of Marketing Trends, 5(2), 1961–7798.

- Boujbel, L., & Et d’Astous, A. (2015). « exploring the feelings and thoughts that accompany the experience of consumption desires». Psychology Et Marketing, 32(2), 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20774

- Bree, J. (1990). « Les enfants et la consommation: un tour d’horizon des recherches ». Recherche Et Applications En Marketing (French Edition), 5(1), 43–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/076737019000500103

- Brée, J. (2021). Kids marketing (3e ed.). EMS. https://doi.org/10.3917/ems.bree.2021.01

- Campbell, C. (1987). The romantic ethic and the spirit of modern consumerism. Basil Blackwell.

- Coates, A., & Boyland, E. (2021). Kid influencers—a new arena of social media food marketing. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 17(3), 133–134. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-020-00455-0

- d’Astous, A., & Deschênes, J. (2005). Consuming in one’s mind: An exploration. Psychology & Marketing, 22(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20044

- Derbaix, C., & Bree, J. (1997). The impact of children's affective reactions elicited by commercials on attitudes toward the advertisement and the brand. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 14(3), 207–229.

- Derbaix, C., Poncin, I., Droulers, O., & Roullet, B. (2012). Mesures des réactions affectives induites par des campagnes pour des causes sociales: complémentarité et convergence de mesures iconiques et verbales French. Recherche Et Applications En Marketing, 27(2), 71–90.

- Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

- Elías Zambrano, R., Jiménez-Marín, G., Galiano-Coronil, A., & Ravina-Ripoll, R. (2021). Children, media and food. A new paradigm in food advertising, social marketing and happiness management. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3588. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073588

- Ezan, P., Gollety, M., Guichard, N., & Hémar-Nicolas, V. (2014). Renforcer l’efficacité des actions de lutte contre l’obésité. Vers l’identification de leviers de persuasion spécifiques aux enfants. Décisions Marketing (73), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.7193/dm.073.13.26.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150980

- Gunter, B. (2015). Kids and branding. In Kids and branding in a digital world (pp. 22–55). Manchester University Press. https://doi.org/10.7228/manchester/9780719097874.003.0003

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

- Hoffmann, W., Baumeister, R. F., Förster, G., & Et Vohs, K. D. (2012). « Everyday temptations: An experience sampling study of desire, conflict, and self-control». Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 102(6), 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026545

- Holm, O. (1999). « Analyses of longing: Origins, levels, and dimensions». The Journal of Psychology, 133(6), 621–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223989909599768

- Hudders, L., & Cauberghe, V. (2018). The mediating role of advertising literacy and the moderating influence of parental mediation on how children of different ages react to brand placements. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 17(2), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1704

- Japutra, A., & Song, Z. (2020). Mindsets, shopping motivations and compulsive buying: Insights from China. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 19(5), 423–437. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1821

- John, D. R. (2001). « 25 ans de recherche sur la ocialization de l’enfant-consommateur ». Recherche Et Applications En Marketing (French Edition), 16(1), 87–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/076737010101600106

- Kavanagh, D. J., Andrade, J., & Et May, J. (2005). « imaginary relish and exquisite torture: The elaborated intrusion theory of desire». Psychological Review, 112(2), 446. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.112.2.446

- Kozinets, R., Patterson, A., Ashman, R., Dahl, D., & Thompson, C. (2017). Networks of desire: How technology increases our passion to consume. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(5), 659–682. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucw061

- Kremer-Sadlik, T. (2001). How children with autism and asperger syndrome respond to questions: An ethnographic study. University of California.

- Krupicka, A. (2005). L’expérience avec le produit: une dimension à reconsidérer dans les modèles de comportement du consommateur enfant?. L'enfant consommateur. Variations interdisciplinaires sur l'enfant et le marché (pp. 17–32). Vuibert.

- MacKinnon, D. P., & Luecken, L. J. (2008). How and for whom? Mediation and moderation in health psychology. Health Psychology, 27(2S), S99.

- Masserot, C. (2007), «Publicité télévisée et obésité infantile: l’ambiguïté d’une relation », Actes des 6èmes journées de Recherche sur la Consommation, Sociétés et Consommations, p.19–20.

- McNeal, J. U. (1992). Kids as customers: A handbook of marketing to children. Lexington Books.

- Mishra, A., & Maity, M. (2021). Influence of parents, peers, and media on adolescents’ consumer knowledge, attitudes, and purchase behavior: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 20(6), 1675–1689. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1946

- Petit, O., Wang, Q. J., & Spence, C. (2022). Does pleasure facilitate healthy drinking? The role of epicurean pleasure in the regulation of wine consumption. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 21(6), 1390–1404. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.2084

- Piaget, J. (1964). « part I: Cognitive development in children: Piaget development and learning». Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 2(3), 176–186. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660020306

- Radesky, J., Chassiakos, Y. L. R., Ameenuddin, N., & Navsaria, D. (2020). Digital advertising to children. Pediatrics, 14, 61. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-1681

- Ramanathan, S., & Et Williams, P. (2007). « immediate and delayed emotional consequences of indulgence: The moderating influence of personality type on mixed emotions». The Journal of Consumer Research, 34(2), 212–223. https://doi.org/10.1086/519149

- Rossiter, J. R. (2019). Children and “junk food” advertising: Critique of a recent Australian study. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 18(4), 275–282. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1773

- Tangsupwattana, W., & Liu, X. (2018). Effect of emotional experience on symbolic consumption in generation Y consumers. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 36(5), 514–527.

- Watkins, L., Robertson, K., & Aitken, R. (2021). Preschoolers’ request behaviour and family conflict: The role of family communication and advertising mediation styles. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 20(5), 1326–1335. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1938

- World Health Organization. (2020) . International classification of functioning, disability, and Health: Children & youth version. ICF-CY. World Health Organization.

- Yi, S., & Jai, T. (2020). Impacts of consumers’ beliefs, desires and emotions on their impulse buying behavior: Application of an integrated model of belief-desire theory of emotion. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 29(6), 662–681. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2020.1692267