Abstract

Grounded in the conservation of resources and social exchange theories, this study aimed to understand how self-initiated expatriate engineers’ (SIEEs) perception of financial, adjustment and career support enhances their creativity level and how cross-cultural resilience (C-CR) moderates this perception. An online survey was conducted with 147 SIEEs from Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries working in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results were analysed by principal least square-structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). Findings demonstrated that financial and adjustment supports have a significant positive relationship with individual creativity while career support does not. Further, C-CR moderates the relationship between financial support and creativity. The study offers significant theoretical and practical implications regarding perceived organisational support (POS) and creativity for host organisations in high-adversity contexts.

1. Introduction

Considering the current drastic decline in oil prices, Saudi Arabia has adopted the 2030 Vision Strategic Framework to transform its oil-based economy into a knowledge-based one and develop various sectors, including technology (Zain et al., Citation2017; Nurunnabi, Citation2017; Vision 2030). One way the country aims to achieve this is by relying on employees’ skills as a key ingredient of innovation and growth sustainability (Bakker et al., Citation2020; Ghafoor & Haar, Citation2021; Kalyar et al., Citation2020; Zhou & George, Citation2001). It urgently needs to create a supportive and safe work environment to propel employees’ creativity to support the country in attaining a sustainable competitiveness ranking target (Zain et al., Citation2017). Along with this idea, fostering creative behaviors among expatriates who represent more than 41% of the Saudi workforce (GASTAT, Citation2022), poses a crucial challenge for host organisations striving to gain and maintain competitiveness in high-adversity contexts (Ali et al., Citation2019; Swalhi et al., Citation2023). High adversity refers to situations or conditions characterized by significant unpredictability, volatility, or ambiguity (Caligiuri et al., Citation2020; Kraus et al., Citation2023) (e.g. pandemics, wars, global recession). A such context may stifle expat engineers ‘aptitudes in terms of creativity for goals achievement.

Creativity is the production of new, novel and useful ideas by individuals or groups in any domain (Amabile et al., Citation1996). Self-initiated expatriate engineers (SIEE) who pursue international careers independent of their home organisation (Andresen et al., Citation2020; Selmer & Lauring, Citation2013) must distinguish themselves by developing creative behaviours to maintain their position within their host organisations (Stoermer et al., Citation2020; Swalhi et al., Citation2023). SIEEs can be understood as (a) talented individuals, (b) who selfintiated their international assignment, (c) having regular employment intentions and (d) with temporary stay in the host country (Cerdin & Selmer, Citation2014). However, these highly skilled professionals are often anxious about their employability owing to their exposure to various challenges related to the expatriate journey they undertake (Amari, Citation2022; Amari et al., Citation2021; Crowley-Henry et al., Citation2018; Panda et al., Citation2022; Stoermer et al., Citation2021). They experience severe uncertainty, which has been further accentuated by the indigenisation of human resources measures adopted in Gulf Cooperation Countries (GCC), such as in KSA (Darwish et al., Citation2002; Amari, Citation2022; Hasanov et al., Citation2021).These adverse circumstances are liable to curb their cognitive abilities and skills and, in turn, reduce their level of creativity (Carnevale & Hatak, Citation2020; Marinov & Marinova, Citation2021). However, the engagement in creative thinking and creative behaviors by expatriates has gone largely neglected in the international business literature (Ali et al., Citation2019; Stoermer et al., Citation2020; Swalhi et al., Citation2023), including engineers cohort. Thus, a deeper understanding of creativity predictors among SIEEs is necessary.

Prior research has underlined the role of perceived organisational support (POS) as a veritable lever to reduce individuals’ anxiety and create an environment that encourages creative behaviours (Duan et al., Citation2020; Zhou & George, Citation2001). From a cross-cultural perspective, POS is a function of adjustment, career and financial support (Kraimer & Wayne, Citation2004), which reduces the negative effects of adverse circumstances and encourages creative behaviours (Inam et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2016). To do so, Social Exchange Theory SET (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005), often deployed as a framework to explain POS’ effects (see Inam et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2016), is mobilised in this study as a theoretical lens to explain how the perception of receiving organisational support may result in psychological obligation, which, in turn, may be transformed into creative behaviours.

Furthermore, expatriates are encouraged to be more persistent and act proactively in anticipation of the challenges they may encounter in overseas employment Andresen et al. (Citation2020), Amari (Citation2022). More particularly, SIEEs must be psychologically equipped to handle stressful challenges in unfamiliar contexts (He et al., Citation2019; Milosevic et al., Citation2017; Prayag et al., Citation2020). In this respect, resilience as a component of positive psychological capital is required to help SIEEs combat adversities (Avey et al., Citation2009; Luthans et al., Citation2007; Prayag et al., Citation2020; Singh et al., Citation2021). However, resilience has largely been neglected in international management research (Amari, Citation2022; Davies et al., Citation2019). In expatriation literature, cross-cultural resilient expatriate employees are those who learn from new experiences by interacting with colleagues from different cultures even during adversities (Dollwet & Reichard, Citation2014). In this vein, cross-cultural resilience (C-CR) is integrated in this study as a potential moderator variable to determine the hidden mechanism by which POS impacts creativity in high-adversity contexts. To this end, the conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018) is added to the conceptual model to thoroughly understand how expatriate employees’ C-CR in overseas employment strengthens the impact of organisational support on creativity. From COR perspective, the accretion of job resources (e.g. POS) and personal resources (e.g. C-CR) would increase the likelihood to engaged in proactive behaviours (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018, including creativity.

The research question is -To what extent does POS helps propel creative behaviors among SIEEs in the context of adversity? and how does C-CR moderate the relationship between POS and creativity?

In answering this questions, this study has several important contributions. First, numerous predictors of creativity have been investigated considering contextual factors and personal or psychological factors. However, the relationship between POS and individual creativity remains largely unexamined (Aldabbas et al., Citation2021; Duan et al., Citation2020). Among the few relevant studies, most have considered Western nations (Davies et al., Citation2019; He et al., Citation2019; Mumtaz & Nadeem, Citation2022) rather than Middle-Eastern nations such as Saudi Arabia (Alshahrani, Citation2022). Hence, this research enriches international business literature by exploring the relationship between POS and creativity in a cross-cultural framework with a greater focus on international employees from MENA countries such as Tunisia and Egypt working in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia was considered, in particular, because of the country’s high proportion of overseas workers (Andresen et al., Citation2020), which makes it a fertile ground for research. Second, most researchers have studied POS as a homogeneous entity that predicts creativity (Davies et al., Citation2019; Duan et al., Citation2020). Contrarily, POS is deconstructed in this study into three dimensions: financial, career and adjustment POS (Kraimer & Wayne, Citation2004). This deconstruction makes POS more adaptable to a cross-cultural context and is more effective in explaining expatriate employees’ success (Kraimer & Wayne, Citation2004). Therefore, this study contributes to creativity literature in that by identifying exactly which kind of POS is required to enhance expatriate employees’ creativity based on the social exchange theory. Third, considering the several inconsistencies that persist, POS’ indirect effect on fostering creativity (Duan et al., Citation2020; Inam et al., Citation2021) is little known and requires further investigation (Zhang et al., Citation2016). Drawing upon the COR theory (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018), this research advances resilience literature by introducing C-CR as a potential moderator by which POS can encourage creative thinking among expatriate employees. This choice is justified by the fact that resilience is considered an essential personal resource in uncertain and dynamic business environments (Tonkin et al., Citation2018).

The results concerning a potential impact of POS on creativity among MENA expatriates, moderated by C-CR, are expected to make previously unexplored contributions to the cross-cultural literature regarding the role of POS. Specifically, the results add to the understanding of the mechanism by which POS can help MENA expatriates achieve this goal in high challenged context. From a practical perspective, this research provides recommendations for the management of Saudi host organisations to foster creativity among their cross-cultural employees in critical context.

The remainder of the paper provides a focused literature review, a discussion of relevant studies, and presents the hypotheses of this study, followed by the methodology and results sections. Thereafter, it presents a discussion and the study’s main implications in relation to the literature. Finally, the paper presents the study’s limitations and possible future research.

2. Literature review and theoretical frameworks

Creativity is the ability to generate novel ideas and practical solutions to problems (Amabile, Citation1983). It has been identified as a key element that helps an organisation achieve sustainable performance (Bammens, Citation2016). However, host organisations’ increasing desire for innovation may be counterproductive and threaten expatriate employees’ well-being (Zhang et al., Citation2016). Therefore, creating a vocational environment where supportive policies are provided may be a prerequisite to ensuring creative performance (Duan et al., Citation2020; Ibrahim et al., Citation2016).

POS gains an increasing attention in international management literature due to adverse circumstances experienced by expatriates (Nolan, Citation2023). In cross-cultural contexts, POS is viewed as a function of (a) financial, (b) career and (c) adjustment support (Kraimer & Wayne, Citation2004) and refers to employees’ perception of the extent to which their professional entourage values their contributions and cares about their well-being (Haar & Brougham, Citation2022; Kurtessis et al., Citation2017). POS has been largely examined as a predictor of individual creativity (Chand & Ambardar, Citation2020; Duan et al., Citation2020; Eisenberger et al., Citation2020; Inam et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2016); however, studies combining the different constructs are scare in expatriate literature. In other words, prior studies have focused on studying POS as a homogeneous contrast due to which its potential impacts on individual outcomes may not have been fully clarified. This limitation may be overcome if POS is deconstructed to identify which kind of support most affects expatriate employees’ creativity.

2.1. Social exchange theory

One of the most valuable theoretical frameworks that I have mobilised in my research model is SET (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005) to explain the impact of POS’ different components on creativity. This framework, characterised by continuous mutual obligations, is often considered in relation to POS as the latter generates positive emotions among individuals (Duan et al., Citation2020) and promotes their well-being (Aldabbas et al., Citation2021; Bammens, Citation2016; Kurtessis et al., Citation2017). SET also suggests that a positive perception of organisational support creates feelings of obligation whereby individuals feel highly committed to their work and respond positively to their organisation by engaging in behaviours that support organisational goals (Wayne et al., Citation1997). In other words, POS make SIEEs feel indebted to their host organisations (Asif et al., Citation2019; Haar & Spell, Citation2004; Zhang et al., Citation2016), who tend to pay back the good intention they receive by diverting their positive energies to fulfilling their organisations’ goals for innovation. Hence, from the SET perspective, it can be argued that positive perceptions towards organisational policies intrinsically motivate employees (Eisenberger et al., Citation1986) to reciprocate by adopting positive behaviours (Bammens, Citation2016; Duan et al., Citation2020; Rhoades & Eisenberger, Citation2002; Zhang et al., Citation2016), including creative behaviours (Aldabbas et al., Citation2021; Asif et al., Citation2019; Zhou & George, Citation2001). Alternatively, a lack of support is liable to negatively influence employees’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and make the job feel less meaningful, thereby resulting in anti-social orientations towards task performance, which undermine their creativity (Duan et al., Citation2020). Accordingly, from the SET perspective, it can be argued that expatriates attempt to concretise “the good treatment” they receive from host organisations by working towards remaining distinguished and creative.

2.1.1. Financial support and creativity

Financial support is defined as the extent to which host organisations care about employees’ financial needs and reward their contributions through compensation and employment benefits (Kraimer & Wayne, Citation2004, pg.218). Expatriate employees, like “mercenaries” (Richardson & McKenna, Citation2006) are motivated by financial incentives, including the opportunity to make and save large amounts of money. Hence, providing financial support to expatriate employees may help foster their creative involvement (Saether, Citation2020; Zhou & George, Citation2001).

Significantly, two conflicting pathways on how monetary rewards affect creativity exist in the literature (Muzafary et al., Citation2021; Wang & Holahan, Citation2017). The first school of thought, based on the self-determination theory, states that monetary rewards reduce intrinsic motivation and, in turn, creativity among highly self-determined individuals. More precisely, employees may perceive financial support as an attempt to control their behaviour, which undermines their perception of self-determination and, in turn, reduces their interest and motivation at work (Deci & Ryan, Citation1985; Selart et al., Citation2008; Wang & Holahan, Citation2017). Financial rewards are also viewed as a distraction from the creative process (Amabile et al., Citation1996). Remarkably, no significant relationship has been found between material incentives and creativity (Wang & Holahan, Citation2017). The second school of thought identifies a positive correlation between individual creativity and material incentives (Eisenberger & Rhoades, Citation2001; Malik et al., Citation2015; Saether, Citation2020). For instance, Saether (Citation2020) found that monetary rewards increase intrinsic motivation and performance and, in turn, creativity. Similarly, Malik et al. (Citation2015) demonstrated that extrinsic rewards contributed to creativity for individuals with high creative self-efficacy and an internal locus of control. Furthermore, when employees’ positive perception of financial incentives is synonymous with recognition, growth or mastery (Li et al., Citation2017), it increases their self-efficacy (Eisenberger & Rhoades, Citation2001) and promotes creative thinking and innovation (Markova & Ford, Citation2011).

Therefore, SIEEs from emerging countries are expected to be interested in material support due to low wages in their home country (Amari et al., Citation2021). From the SET perspective, the recognition of high-skilled expatriate employees through financial support may be said to contribute to creative behaviours. Thus, the following hypothesis is drawn:

Hypothesis 1a.

Financial support would positively impact creativity.

2.1.2. Career support and creativity

Career support is defined as the extent to which host organisations care about employees’ career needs (Kraimer & Wayne, Citation2004, pg. 218). By providing career policies and programs (e.g. career guidance, education, and counselling), host organisations can help expatriate employees cope with career decisions (Bimrose & Brown, Citation2020). In particular, career counselling has been known to foster career adaptability and contributes to increased proactive career behaviours (Spurk et al., Citation2019). In other words, when employees perceive that they are well-supported by their managers, they are psychologically more prepared to cope with challenging career transitions by developing transactional competencies (Savickas, Citation2005) and proactive behaviours (Spurk et al., Citation2019). Similarly, Abukhait et al. (Citation2020) defined highly career-adaptive employees as those who develop abilities, solutions and non-routine approaches for solving problems in highly unpredictable contexts, which, in turn, fosters innovative work behaviour. The idea that career supportive policies enhance employees’ knowledge capital in terms of functional skills and managerial capabilities further supports this reasoning (Kraimer et al., Citation2011; Xu et al., Citation2021). Contrarily, when expatriate employees perceive a lack of career support, they are dissatisfied and more predisposed to withdraw from creativity goals within their host organisations.

Therefore, from the SET perspective, expatriate employees can be expected to repay organisational care and support for their career prospects by exhibiting new competencies to cope with adversity. Thus, the following hypothesis is drawn:

Hypothesis 1b.

Career support would positively impact creativity.

2.1.3. Adjustment support and creativity

Adjustment support is defined as the extent to which host organisations care about expatriate employees’ (including their families) adjustment following a job transfer (Kraimer & Wayne, Citation2004, p. 218). One of the most common reasons that expatriate employees cite for prematurely terminating foreign assignments is poor cross-cultural adjustment or adaptation (Davies et al., Citation2015; Takeuchi et al., Citation2002). In this regard, better adjustment among expatriate employees and their families is likely to encourage better engagement in organisational performance (Chen, Citation2019; Nolan, Citation2023; Shen & Jiang, Citation2015), including creativity.

Empirically, POS has been proved to directly impact expatriate employees’ adjustment and job performance (Kraimer et al., Citation2001). Adjustment policies provided within host organisations enhance employees’ acceptance of unfamiliar contexts and facilitate proper adaptation, thereby helping them meet the requirement for high job performance (Chen, Citation2019; Mumtaz et al., Citation2020; Nolan, Citation2023). Additionally, studies have found that expatriate employees whose personal value orientation fits with the host country’s national culture have a high tendency to exhibit innovative behaviour (Tsegaye et al., Citation2019). This is because they are culturally intelligent and can easily interact with people from different cultures (Jyoti & Kour, Citation2017; Stoermer et al., Citation2021). This interaction helps them acquiring the necessary knowledge and social skills to perform their job effectively (Nolan, Citation2023). Thus, team-knowledge sharing may help foster individual competitiveness within host organisations and subsequently, encourage expatriate employees to exhibit greater degrees of innovative work behaviours (Ratasuk & Charoensukmongkol, Citation2020).

Contrarily, socio-cultural factors (e.g. the inability of employees’ spouses and children to adapt to the host country’s culture, family instability and lack of language skills) are also identified as important obstacles to adjustment to the host country (Kraimer & Wayne, Citation2004; Takeuchi et al., Citation2002). In particular, this obstacle is more pronounced among collectivistic expatriate employees because they try to maintain strong familial bonds even with family members in their home country (Amari et al., Citation2023). For instance, Shaffer et al. (Citation2012) advocated that family-related factors, such as individuals’ responsibility to care for elderly parents in their home country, pose significant barriers to staying abroad. In the absence of social ties with their family, expatriate employees are likely to be exposed to the risk of superficial performance (Erogul & Rahman, Citation2017) and are likely to withdraw from the creative process.

From the SET perspective, policies that consider expatriate employees’ adjustment to the host country and their family issues are likely to fuel creativity. Thus, the following hypothesis is drawn:

Hypothesis 1c.

Adjustment support would positively impact creativity.

2.2. Moderating role of C-CR

Prior researches pointed out that the effectiveness of POS can be questioned because in some cases, POS may be intrusive and undermine employees’ abilities (Bammens, Citation2016). As such, creativity is conditional and individuals cannot express it at all times (Bakker et al., Citation2020). Therefore, it is important to integrate personality trait variables, such as C-CR, to understand the hidden mechanism by which POS impacts creativity.

Cross-Cultural Resilience is an emerging topic and has recently been documented to be essential to organisational adaptability in uncertain and dynamic business environments (Prayag et al., Citation2020; Tonkin et al., Citation2018). To be creative, SIEEs must be resilient to bounce back from the host adverse environment, in this case Saudi Arabia. Resilience enables them to be more psychological comfortable while facing adversity (Amari, Citation2022; Andresen et al., Citation2020; He et al., Citation2019, Kuntz et al., Citation2019; Luthans et al., Citation2007; Milosevic et al., Citation2017). Thus, it is essential that they can reduce this adversity by adopting resilient behaviors for organisational achievement goals.

C-CR is defined as the ability to learn from new experiences by interacting with colleagues from different cultures even when they are facing difficulties such as cross-cultural conflicts (Dollwet & Reichard, Citation2014). Resilient people are known to be innovative, skilled and confident (Yu et al., Citation2019). Scholars sate that resilience is a detrimental element that influences employees’ cognitive skills and fosters motivation for workplace creativity (Kalyar et al., Citation2020; Shalley et al., Citation2004). These proactive skills and tactics allow them to promote creativity within the organisation (Bakker et al., Citation2020; Singh et al., Citation2021). Taken together, C-CR can be viewed as a set of proactive learning behaviours that facilitate change and innovation even in adverse cross-cultural contexts (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018; Kuntz et al., Citation2017; Singh et al., Citation2021). In some previous studies, it’s found that C-CR fosters cultural intelligence among cross-cultural employees by helping them cope with uncertainty and exhibit broadened thinking (Clapp-Smith et al., Citation2007).

The COR theory constitutes a viable theoretical framework for an in-depth understanding of how expatriate employees’ C-CR enhances POS’ impact on creativity. It posits that individuals are genetically motivated to acquire and conserve resources for their survival (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018). Hobfoll et al. (Citation2018) defined resources as anything that helps individuals attain their goals. These resources may emanate from organizational (e.g. POS) as well as from or personal sources (e.g. C-CR). COR theory theorized that resources generate other resources and, then they are interrelated and co-travel together in “caravan” (Hobfoll, Citation2002). To recover from resources loss due to high adversity, people must invest in resources (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018). In this regard, the threat of resource drainage, instigated by host country challenges, directs individuals toward behaviours that enable them to gain further resources to cope with hardships (De Clercq & Pereira, Citation2022) by accumulating and maximising all kinds of received organisational benefits (e.g. rewards, career opportunities, training). Thus, individuals who invest more in psychological resources, in our case C-CR, tend to overweigh organizational resources acquired from organisational support. This accretion of resources occurred from both organisational support and C-CR would increase the likelihood to engaged in proactive behaviours (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018), including creativity. Hence, C-CR as a personal positive resource (Bakker et al., Citation2020; Luthans et al., Citation2007; Roemer & Harris, Citation2018) can enable SIEEs to maximise POS benefits within Saudi host organisations leading them to adopt creativity-oriented behaviour in high-adversity contexts (Singh et al., Citation2021).

Accordingly, C-CR can be suggested to function as a moderator between POS and creativity. It can be argued that highly resilient SIEEs tend to maximise the benefits of resources provided in a supportive environment, which encourages them to handle high-adversity contexts competently and proactively (Singh et al., Citation2021). Using the COR theory, it can be expected that the impact of financial, adjustment and career supports or POS on creativity will be stronger for SIEEs’ who have high C-CR levels than those who have low C-CR levels. The following hypotheses are drawn:

Hypothesis 2a.

Cross-cultural Resilience moderates the positive relationship between Financial POS and creativity.

Hypothesis 2b.

Cross-cultural Resilience moderates the positive relationship between Career POS and creativity.

Hypothesis 2c.

Cross-cultural Resilience moderates the positive relationship between Adjustment POS and creativity.

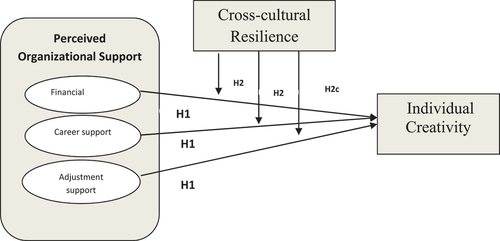

The figure illustrates the hypohtesised coneptual model

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and data collection

A cross-design online survey was conducted with SIEEs from MENA countries working in Saudi Information and Telecommunication (IT) sector. According to the Saudi Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, IT sector is considered as strategic for the government since it would contribute to compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 3.40% during the forecast period (2023–2028). Additionally, this sector is a pillar of the Vision 2023 program aimed at building a thriving digital economy and innovation. MENA’s IT expatriates engineers in Saudi Arabia are targeted in this study for two main reasons. First, Saudi Arabia need to focus on industrial engineers, including IT cohort, to achieve the 2030 vision targets (Alkahtani et al., Citation2018). Second, Saudi Arabia is significant for this study because is potentially interesting destination for expatriates. Indeed, the Saudi IT sector is dominated by IT expatriates engineers (Hasanov et al., Citation2021). Approximately, 37% of expatriates come from Arabic region (GASTAT, Citation2022), including MENA countries.

A pilot study was performed to test the content validity of the bilingual questionnaire (Arabic-English) among three associate professors and two practitioners. In order to enhance the response rate, a snowball methodology is applied to ask the initial survey participants to share the questionnaire with others who would be willing to participate in the study (Panda et al., Citation2022). The researcher ensured voluntary participation and informed participants that their responses would be entirely anonymous and collected for academic research purposes. Over 500 invitations were sent to telecom engineering expatriates in their professional emails, LinkedIn accounts and on social networking sites (e.g. Facebook) during summer—Fall 2021. However, 46 individuals were removed because their nationalities did not match the targeted survey region (the MENA region). The final data was collected from 147 SIEEs, yielding a response rate of 29.4%. The sample population characteristics are presented in Table .

Table 1. Sample sociodemographic proprieties

3.2. Measurement instruments

A well-established five-point Likert scale instruments is used, ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree), to measure the variables (see Table for reference). The researcher adopted individual creativity from Gao et al. (Citation2021), financial, adjustment, and career POS from Kraimer and Wayne’s (Citation2004), and C-CR from Dollwet and Reichard’s (Citation2014).

Table 2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of measurement model

A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted following the recommendations of Hair et al. (Citation2020) regarding which analysis to conduct, what indicators to assess the measurement model, and how to display the findings of the partial least squares-structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). PLS-SEM was used in this research as it can easily evaluate complex models incorporating multi-item constructs and test mediating and moderating links. It can also separately evaluate the measurement model and the structural model (Hair et al., Citation2020). Lastly, it imposes fewer restrictions on the sample size (Hair et al., Citation2020).

The reliability of the constructs is assessed to determine whether each item is consistent with other items belonging to the same construct. This study removed ADJ3, ADJ4, and CCR1 after the first run of the PLS algorithm due to low loadings (0.005 and 0.193, 0.406, respectively). After dropping these two items, the analysis was rerun. First, all outer loadings are satisfactory and significant (p < 0.05). Second, Cronbach’s alpha and rho_A (ρA) values are above the threshold of 0.7. This results reflect the reliability of the constructs (Hair et al., Citation2020). Indeed, Table highlights that the values of the Cronbach’s alphas range from 0.701 to 0.850 and those of rho_A (ρA) range from 0.756 to 0.864.

Table 3. Loadings, CA, ρA, and AVE

In addition, a convergent validity was assessed by ensuring that the average variance extracted (AVE) for all the constructs was above 0.5. This result shows convergent validity. Table highlights that the AVE values range between 0.603 and 0.917. Thus, all the constructs illustrate a satisfactory reliability and convergent validity. Furthermore, common method variance is not a problem in this study since the first factor accounts for less than 50% of the overall variance, in line with Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003).

Lastly, the discriminant validity referring to the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT) method of correlation (Hair et al., Citation2020) is evaluated. Table shows that the HTMT values are lower than 0.85 and statistically different from 1. These results reflect discriminant validity, in line with Hair et al. (Citation2017).

Table 4. Discriminant validity

4.2. Evaluation of structural model

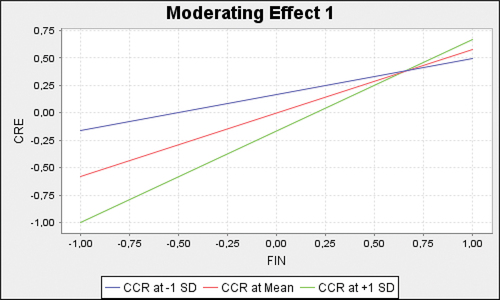

As shown in Table , the proposed model explains 51.2% of the variance in individual creativity. Regarding the hypotheses, financial POS and adjustment POS have positive effects on individual creativity (β = 0.577;CI = [0.460; 0.678] and β = 0.287;CI = [0.157; 0.418], respectively). Thus, H1a and H1c are supported. However, career POS has a non-significant effect on individual creativity. H1b is not supported. In addition, the results show that cross-cultural resilience positively moderates the effect of financial POS on individual creativity (βFINxCCR = 0.253; CI = [0.007; 0.354]), as shown in Figure . However, it does not moderate the effects of career POS and adjustment POS on individual creativity (βCARxCCR = 0.000; CI = [−0.141; 0.124] and βADJxCCR = 0.029; CI = [−0.132; 0.185], respectively).

Table 5. Results of the structural model

5. Discussion and implications

Although POS is an important resource that host organisations should provide to make the work environment more appealing, studies on POS as a combination of financial, career and adjustment supports and its relationship with expatriate employees’ creativity are scarce. This study, therefore, determined which kind of POS influences creativity among SIEEs from MENA countries. It further investigated whether C-CR moderates this relationship.

Accordingly, the proposed conceptual model demonstrated the different impacts of POS as the set of financial, career and adjustment support on employees’ creativity. Results demonstrated a significant positive relationship between financial POS and creativity, thereby supporting the hypothesis (Ha1). These findings are also in line with those of Saether (Citation2020) and Malik et al. (Citation2015) but incongruent with those of Wang and Holahan (Citation2017). SET posits that SEEIs perceive financial support as a sign of recognition (Li et al., Citation2017) for their efforts, which increases their self-efficacy (Eisenberger & Rhoades, Citation2001) and promotes creative thinking in future projects. This study supports this view in that my study respondents were predominantly interested in financial rewards and shifted to an international location for material gains (Amari et al., Citation2021).

However, contrary to the hypothesis (H1b), the impact of career support on SEEIs’ creativity was insignificant. This result contrasts the findings of Kraimer et al. (Citation2011) and Xu et al. (Citation2021) who suggested the need for career supportive policies to foster SIEEs’ distinguished skills. The researcher may not have found any remarkable association between career support and creativity in this study because most of the respondents were highly qualified with over 10 years of experience (see Table ). Therefore, career supportive policies may not have any significant impact, particularly in terms of creativity.

Additionally, findings showed a significant positive association between adjustment support and creativity, which is in line with the hypothesis (H1c). This result can be explained from the SET perspective in that when SIEEs perceive that their host organisations care about their adaptability and family issues, they feel protected and are more predisposed to respond creatively even in high-adversity contexts. This finding also coincides with those of Chen (Citation2019) and Tsegaye et al. (Citation2019) and demonstrates the need for adjustment policies to foster SIEEs’ cultural intelligence (Stoermer et al., Citation2021) and, ultimately, their creativity. In this study, this positive association could be further explained in light of the Arabo-Islamic culture of some SIEEs, for whom cultural similarities between their home country and Saudi Arabia might increase the likelihood of exhibiting innovative behaviour (Tsegaye et al., Citation2019).

Finally, the results also demonstrated that C-CR significantly moderates the relationship between financial support and creativity. The higher the C-CR, the stronger the effect of financial rewards on creativity. This finding can be explained in terms of the COR theory (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018), which suggests that highly resilient SIEEs will express high optimism and take advantage of financial support to deal competently and proactively in high-adversity contexts (Singh et al., Citation2021). This finding also implies that resilience as a protective factor for expatriates (Clapp-Smith et al., Citation2007) shapes the positive perceptions about financial support, which is conducive to creativity. It also highlights the importance of financial support during critical circumstances such as those experienced by SIEES in the two last years.

5.1. Implications for theory

This study makes three main contributions to international business literature. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have linked POS as a combination of financial, career and adjustment supports to expatriate employees’ creativity.

First, this study clarifies which kind of POS has the greatest influence on creativity. The deconstruction of POS empirically extends Kraimer and Wayne’s (Citation2004) approach. Specifically, findings establish financial and adjustment supports, as key predictors of expatriate employees’ creativity in high-adversity contexts. The SET was employed to further establish this point and demonstrate that expatriate employees find their work more meaningful when they receive financial and adjustment support (Duan et al., Citation2020) and reciprocate by exhibiting creative behaviours within their host organisations. These kinds of support create a plausible atmosphere for them in high-adversity contexts. Likewise, in the case of SIEEs, they will work more meticulously if they feel that their host organisations care for them and protect them. Further, compared to financial or adjustment support, the impact of career support is insignificant and does not boost creativity. Thus, this study strengthens the idea that different supportive policies (financial, career and adjustment) that comprise POS have different impacts on expatriate employees’ creativity, and investigating POS as a single construct would distort these interpretations.

Second, the current study enriches the existing literature by focusing on expatriate SIEEs from MENA countries. This population is highly under-researched; little is known about their experience in their host countries (Amari et al., Citation2021; Andresen et al., Citation2020). Based on study’s findings, the researcher concludes that high-skilled expatriate SIEEs from MENA countries are more interested in financial and adjustment support than career support and demonstrate significant creativity when they receive such support.

Third, this research offers novel insight to prior research by introducing C-CR as a coping mechanism by which the three components of POS affect creativity in high-adversity contexts. In this regard, the results demonstrate that C-CR reinforces the effect of financially supportive practices on creativity, thereby extending the studies conducted by Zhang et al. (Citation2016) and Kalyar et al. (Citation2020). This further establishes that high-resilient SIEEs require more material support from their managers to enhance their potential and engage in creative ways. Organisations can fulfil this requirement by helping them and their families adapt to their new environment. Additionally, this study supports the relationship between POS and creativity by providing evidence about C-CR as the boundary condition in high-adversity contexts and times of adversity, thereby extending Davies et al. (Citation2019) and Inam et al. (Citation2021) study.

5.2. Implications for practice

As Saudi Arabia shifts from an oil-dependent economy to a knowledge economy, it creates the need for empirical research of human resource professionals in the region, such as that presented in this study, to help organisations formulate a sustainable strategy focusing on creativity. The findings of this study have two main practical implications.

First, financial and adjustment supports are influential factors that enhance SEEIs’ creativity and indicate the vital role of creativity in establishing a safe vocational environment where SIEEs feel more comfortable working and feel motivated to develop novel ideas (Inam et al., Citation2021) even in high-adversity contexts. Therefore, considering the positive effects of both financial and adjustment supports on employees’ creativity, managers in host organisations should pay more attention to these two kinds of POS and consider them basic requirements that stimulate employees’ creativity (Amabile et al., Citation1996). This, in turn, can make expatriate employees more cross-culturally equipped by increasing their creativity and helping them thrive in high-adversity contexts. Hence, host organisations can help expatriate employees cope with global crises by rewarding their creativity. Additionally, training SIEEs about the host culture promotes an harmony working environment (Zaman et al., Citation2021), that encouraging interaction and cohesion between native and non-native employees. Such cultural intelligence-oriented policies may also lead to creative behaviours (Aldabbas et al., Citation2021; Tsegaye et al., Citation2019).

Second, high resilience among SIEEs strengthens the positive effect of financial support on creativity in high-adversity contexts (Singh et al., Citation2021). Thus, managers should promote high resilience as a way to enhance expatriate employees’ performance. They may emphasise, in particular, professional promotion and training as resilience-building initiatives to improve individual abilities (Kuntz et al., Citation2017). Further, multi-cultural organisations should foster inclusive behaviours (Davies et al., Citation2019) as a way to protect expatriate employees’ resilience, particularly in Saudi Arabian organisations where power distance, collectivism and uncertainty avoidance are significant (Hofstede, Citation2001). Subsequently, Saudi Arabian managers should endorse an inclusive leadership style to reduce native employees’ fear related to uncertainty about interactions with non-native expatriate employees (Davies et al., Citation2019).

6. Limitations and future recommendations

This study has several limitations that leave scope for future research. First, the research design has limited scope. Only MENA’s engineers working in the Riyadh region were covered. Therefore, findings may not be generalizable to SIEEs working in other countries because of the high level of collectivism in this region (Hofstede, Citation2001; Jannesari & Sullivan, Citation2021). Thus, the geographical boundary of this research should be expanded to include other regions and oriental cultures, and the results should be compared to make this current research more conclusive. Second, although this study ensured the anonymity and confidentiality of the study respondents and regarded their responses as honest responses, as suggested by Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003), the researcher conducted a self-administered survey, which could be exposed to the risk of bias. Moreover, the model’s cross-sectional design prevented causality deduction between POS and creativity. Thus, to establish a proportional connection between these two constructs, future research should consider longitudinal or qualitative methods within this research design. Finally, although researchers’ concerns regarding the lack of underlying mechanisms and boundary conditions in explanations of creativity were addressed, the scope of this study was limited to psychological factors (resilience). Future studies can extend this aspect by incorporating others moderators or mediators, such as age, and performing generational analysis. This is because the effects of POS can differ, especially in times of crisis (Li et al., Citation2021).

7. Conclusion

This study recommends ways in which host organisations can reduce the vulnerability that expatriate employees experience, particularly in high-adversity contexts. Significantly, one of the major concerns of expatriate employees is uncertainty about their future. Therefore, host organisations must ensure their safety and security. To this end, managers in host organisations should promote supportive HR policies in terms of rewards, career and adjustment support to make expatriate employees feel more comfortable in an unfamiliar work environment. This, in turn, will enhance employees’ creativity and benefit the organisation. This research improves the understanding of how financial and adjustment supports contribute to SIEEs’ creativity in high-adversity contexts. It also establishes C-CR as an important psychological resource that reinforces the impact of financial support on individual creativity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Amina Amari

Amina Amari is an Assistant Professor in Human Resources Management at the College of Economics and Administrative Sciences in Al-Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (Riyadh, KSA). She is also at FSEG of Nabeul in Tunisia. With more than 18 years of research and teaching experience, she has published many prestigious international articles. Her research and teaching interests lie in the area of cross-cultural management, organizational behaviour and expatriation.

References

- Abukhait, R., Bani-Melhem, S., & Shamsudin, F. (2020). Do employee resilience, focus on opportunity, and work-related curiosity predict innovative work behaviour? the mediating role of career adaptability. International Journal of Innovation Management, 24(2050070), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1142/S136391962050070X

- Aldabbas, H., Pinnington, T., & Lahrech, A. (2021). The influence of perceived organizational support on employee creativity: The mediating role of work engagemen. Current Psychology, 42(8), 6501–6515. In press. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01992-1

- Ali, I., Ali, M., Leal-Rodriguez Antonio, L., & Albort-Morant, G. (2019). The role of knowledge spillovers and cultural intelligence in enhancing expatriate employees’ individual and team creativity. Journal of Business Research, 101, 561–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.012

- Alkahtani, M. S., El-Sherbeeny, A. M., Noman, M. A., & Abdullah, F. M. (2018). Trends in industrial engineering and the Saudi Vision 2030. In K. Barker, D. Berry, & C. Rainwater (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2018 IISE Annual Conference, Florida- USA.

- Alshahrani, S. T. (2022). The motivation for the mobility–A comparison of the company assigned and self-initiated expatriates in Saudi Arabia. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), 2027626. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2027626

- Amabile, T. M. (1983). The social pschology of creativity: A componential conceptualization. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 45(2), 357–376.

- Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 39(5), 1154–1184. https://doi.org/10.2307/256995

- Amari, A. (2022). Does justice climate prevent MENA female self-initiated expatriates to quit their companies? The mediating effect of cross-cultural resilience. Handbook of Research on Entrepreneurship and Organizational Resilience During Unprecedented Times. https://doi.org/10.408/978-1-6684

- Amari, A., Berrais, S., & Hofaidhllaoui, M. (2023). Does expatriates’ cross-cultural psychological capital mediate the link between ethical organisational climate and turnover intention? A generational cohort comparison. European Journal of International Management.

- Amari, A., Hofaidhllaoui, M., & Swalhi, A. (2021). How do academics manage their stay and career prospects during their International assignment? An exploratory analysis. Recherches en Sciences de Gestion, N° 145(4), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.3917/resg.145.0185

- Andresen, M., Pattie, M. W., & Hippler, T. (2020). What does it mean to be a ‘self-initiated’ expatriate in different contexts? A conceptual analysis and suggestions for future research. International Journal of HRM, 31(1), 174–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1674359

- Asif, M., Qing, M., Hwang, J., & Shi, H. (2019). Ethical leadership, affective commitment, work engagement, and creativity: Testing a multiple mediation approach. Sustainability, 11(4489), 4489. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164489

- Avey, J. B., Luthans, F., & Jensen, S. M. (2009). Psychological capital: A positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Human Resource Management, 48(5), 677–693. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20294

- Bakker, B. A., Petrou, P., Kamp, E., & Tims, M. (2020). Proactive vitality Management, work engagement, and creativity: The role of goal orientation. Applied Psychology, 69(2), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12173

- Bammens, Y. P. M. (2016). Employees’ innovative behavior in social context: A closer examination of the role of organizational care. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 33(3), 244–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12267

- Bimrose, J., & Brown, A. (2020). The interplay between career support and career pathways, in career pathways: From school to retirement. Hedge J., Carter G. Eds. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190907785.003.0005

- Caligiuri, P., De Cieri, H., Minbaeva, D., Verbeke, A., & Zimmermann, A. (2020). International HRM insights for navigating the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for future research and practice. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(5), 697–713. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00335-9

- Carnevale, J. B., & Hatak, I. (2020). Employee adjustment and wellbeing in the era of COVID-19: Implications for human resource management. Journal of Business Research, 116, 183–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.037

- Cerdin, J. L., & Selmer, J. (2014). Who is a self-initiated expatriate? Towards conceptual clarity of a common notion. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(9), 1281–1301. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.863793

- Chand, M., & Ambardar, A. (2020). The impact of HRM praticies on orgnaizational innovation performance, the mediating effects of employee’s creativity and perceived organizational support. Internationa Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Systems, 13(1), 68–80.

- Chen, M. (2019). The impact of expatriates’ cross-cultural adjustment on work stress and job involvement in the high-tech industry. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(2228), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02228

- Clapp-Smith, R., Luthans, F., & Avolio, B. J. (2007). The role of psychological capital in global mindset development. Advances in International Management, 19, 105–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1571-5027

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

- Crowley-Henry, M., O’Connor, E., & Al-Ariss, A. (2018). Portrayal of skilled Migrants’ careers. European Management Review, 15(3), 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12072

- Darwish, Y. K., Al Waqfi, M. A., Alenzi, A. N., Haak-Shaheem, W., & Brewester, C. (2002). Bringing it all back home: In the HRM role in workfor localisation in MNEs in Saudi Arabia. The International Journal of Human Ressource Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585193.2022.2148551

- Davies, S., Kraeh, A., & Froeze, F. (2015). Burden or support? The influence of partner nationality on expatriates cross-cultrual adjustement. Journal Fo Global Mobility, 3(2), 169–182.

- Davies, S. E., Stoermer, S., & Forese, F. J. (2019). When the going gets tough: The influence of expatriate resilience and perceived organizational inclusion climate on work adjustment and turnover intentions. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(8), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1528558

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7

- De Clercq, D., & Pereira, R. (2022). Pandemic fears, family interference with work, and organizational citizenship behavior: Buffering role of work-related goal congruence. European Management Review, 19(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12502

- Dollwet, M., & Reichard, R. (2014). Assessing cross-cultural skills: Validation of a new measure of cross-cultural psychological capital. International Journal of HRM, 25(12), 1669–1696. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.845239

- Duan, W., Tang, X., Li, Y., Cheng, X., & Zhang, H. (2020). Perceived organizational support and employee creativity: The mediation role of calling. Creativity Research Journal, 2(4), 403–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2020.1821563

- Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Percived orgnizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(2), 500–5007.

- Eisenberger, R., & Rhoades, L. (2001). Incremental effects of reward on creativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(4), 728–741. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.4.728

- Eisenberger, R., Rhoades Shanock, L., & Wen, X. (2020). Perceived organizational support: Why caring about employees counts. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 7(1), 101–124. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012119-044917

- Erogul, M. S., & Rahman, A. (2017). The impact of family adjustment in expatriate success. Journal of International Business and Economy, 18(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.51240/jib2.2017.1.1

- Gao, Y., Zhao, X., Xu, X., & Ma, F. (2021). A study on the cross level transformation from individual creativity to organizational creativity. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 171), 120958, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120958

- GASTAT. (2022). Labor market statistics. Available at. https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/814

- Ghafoor, A., & Haar, J. (2021). Does job stress enhance employee creativity? Exploring the role of psychological capital. Personnel Review, 51(2), 644–661. In Press. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-08-2019-0443

- Haar, J., & Brougham, D. (2022). A teams approach towards job insecurity, perceived organisational support and cooperative norms: A moderated-mediation study of individual wellbeing. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(8), 1670–1695. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1837200

- Haar, J., & Spell, C. (2004). Program knowledge and value of work-family practices and organizational commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 15(6), 1040–1055. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190410001677304

- Hair, J. F., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage.

- Hasanov, F. J., Mikayilov, J. I., Javid, M., Al-Rasasi, M., Joutz, F., & B Alabdullah, M. (2021). Sectoral employment analysis for Saudi Arabia. Applied Economics, 53(45), 5267–5280. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2021.1922590

- He, B., An, R., & Berry, J. (2019). Psychological adjustment and social capital: A qualitative investigation of Chinese expatriates. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 26(1), 67–92. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-04-2018-0054

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological ressources and adpatation. Review of General Psyhology, 6(4), 307–334.

- Hobfoll, S., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviours, institutions and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Sage Publication.

- Ibrahim, H. I., Isa, A., & Shahbudin, A. S. M. (2016). Organizational support and creativity: The role of developmental experiences as a moderator. Procedia Economics and Finance, 35, 509–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(16)00063-0

- Inam, A., Ho, J. A., Zafar, H., Khan, U., Sheikh, A. A., & Najam, U. (2021). Fostering creativity and work engagement through perceived organizational support: The interactive role of stressors. SAGE Open, 11(3), 215824402110469. in press. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211046937

- Jannesari, M. T., & Sullivan, S. E. (2021). Leaving on a jet plane? The effect of challenge–hindrance stressors, emotional resilience and cultural novelty on self-initiated expatriates’ decision to exit China. Personnel Review, 51(1), 118–136. in press. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-05-2020-0362

- Jyoti, J., & Kour, S. (2017). Cultural intelligence and job performance an empirical investigation of moderating and mediating variables. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 17(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595817718001

- Kalyar, M. N., Saeed, M., Usta, A., & Shafique, I. (2020). Workplace cyberbullying and creativity: Examining the roles of psychological distress and psychological capital. Management Research Review, 44(4), 607–624. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-03-2020-0130

- Kraimer, M. L., Seiber, S., Wayne, S. J., Liden, R. C., & Bravo, J. (2011). Antecedents and outcomes of organizational support for development: The critical role of career opportunities. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(3), 485–500. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021452

- Kraimer, M. L., & Wayne, S. J. (2004). An examination of perceived organizational support as a multidimensional construct in the context of an expatriate assignment. Journal of Management, 30(2), 209–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2003.01.001

- Kraimer, M. L., Wayne, S. J., & Jaworski, R. A. (2001). Sources of support and expatriate performance: Role of expatriate adjustement. Personnel Psychology, 54(1), 71–99.

- Kraus, S. A., Blake, B. D., Festing, M., & Shaffer, M. A. (2023). Global employees and exogenous shocks: Considering positive psychological capital as a personal resource in international human resource management. Journal of World Business, 58(3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2023.101444

- Kuntz, J. R. C., Malinen, S., & Näswall, K. (2017). Employee resilience: Directions for resilience development. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 69(3), 223–242. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000097

- Kuntz, J. M., S., & Naswall, K. (2017). Employee resilience: Driection for resilience development. Psychology Journal: Oratice and Resaerch, 69(3), 232–242.

- Kurtessis, J. N., Eisenberger, R., Ford, M. T., Buffardi, L. C., Stewart, K. A., & Adis, C. S. (2017). Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1854–1884. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315575554

- Li, F., Deng, H., Leung, K., & Zhao, Y. (2017). Is perceived creativity-reward contingency good for creativity. The role of challanges and threats appraisals. Human Ressource Management, 56, 551–709.

- Li, F., Luo, S., Mu, W., Li, Y., Ye, L., Zheng, X., Xu, B., Ding, Y., Ling, P., Zhou, M., & Chen, X. (2021). Effects of sources of social support and resilience on the mental health of different age groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-03012-1

- Luthans, F., Bruce, O., James, B. A., & Steven, M. S. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Leadership Institute Faculty Publications, 60(3), 541–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x

- Malik, M. A. R., Butt, A. N., & Choi, J. N. (2015). Rewards and employee creative performance: Moderating effects of creative self-efficacy, reward importance, and locus of control. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1943

- Marinov, M. A., & Marinova, S. T. (2021). Covid-19 and International Business: Change of era. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003108924

- Markova, G., & Ford, C. (2011). Is money the panacea? Rewards for knowledge workers. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 60(8), 813–823. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410401111182206

- Milosevic, I., Bass, A. E., & Milosevic, D. (2017). Leveraging positive psychological capital (PsyCap) in crisis: A multiphase framework. Organization Management Journal, 14(3), 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/15416518.2017.1353898

- Mumtaz, S., & Nadeem, S. (2022). Understanding the development of a common social identity between expatriates and host country nationals. Personnel Review, 52(1), 42–57. in press. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-07-2021-0535

- Mumtaz, S., Nadeem, S., Wright, L. T., & Wright, L. T. (2020). When too much adjustment is bad: A curvilinear relationship between expatriates’ adjustment and social changes in HCNs. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1857064

- Muzafary, S. S., Wahdat, M. N., Hussain, M., Mdletshe, B., Tilwani, S. A., Khattak, R., & Rezvani, E. (2021). Intrinsic rewards for creativity and employee creativity to the mediation role of knowledge sharing and intrinsic motivation. Education Research International, 2021, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6464124

- Nolan, E. (2023). The cultural adjustment of self-initiated expatriate doctors working and living in Ireland. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2164138. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2164138

- Nurunnabi, M. (2017). Transformation from an oil-based economy to a knowledge-based economy in Saudi Arabia: The direction of Saudi vision 2030. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 8(2), 536–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-017-0479-8

- Panda, M., Pradhan, R. K., & Singh, S. K. (2022). What makes organization-assigned expatriates perform in the host country? A moderated mediation analysis in the India-China context. Journal of Business Research, 142, 663–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.01.010

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Prayag, G., Spector, S., Orchiston, C., & Chowdhury, M. (2020). Psychological resilience, organizational resilience and life satisfaction in tourism firms: Insights from the Canterbury earthquakes. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(10), 1216–1233. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1607832

- Ratasuk, A., & Charoensukmongkol, P. (2020). Does cultural intelligence promote cross-cultural teams’ knowledge sharing and innovation in the restaurant business. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 12(2), 183–203. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJBA-05-2019-0109

- Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698–714. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698

- Richardson, J., & McKenna, S. (2006). Exploring relationships with home and host countries: A study of self-directed expatriate. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, 13(2006), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/13527600610643448

- Roemer, A., & Harris, C. (2018). Perceived organizational support and well-being: The role of psychological capital as a mediator. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 44(2). https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v44i0.1539

- Saether, E. A. (2020). Creativity-Contingent rewards, intrinsic motivation, and creativity: The importance of fair reward evaluation procedures. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(974), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00974

- Savickas, M. L. (2005). The theory and practice of career construction. In S. Brown & R. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counselling: Putting theory and research to work (1st ed., pp. 42–70). John Wiley and Sons.

- Selart, M., Nordstroem, T., Kuvaas, B., & Takemura, K. (2008). Effects of reward on self-regulation, intrinsic motivation and creativity. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 52(5), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830802346314

- Selmer, J., & Lauring, J. (2013). Cognitive and affective reasons to expatriate and work adjustment of expatriate academics. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, 13(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595813485382

- Shaffer, M. A., Kraimer, M. L., Chen, Y., & Bolino, M. C. (2012). Choices, challenges and careeer consequences of global work experiences a reveiw and fture agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 1282–1327.

- Shalley, C. E., Zhou, J., & Oldman, G. R. (2004). The effects of personal and contextual characteristics on creativity: Where should we go from here?. Journal of Management, 30(6), 933–958.

- Shen, J., & Jiang, F. (2015). Factors influencing Chinese female expatriates’ performance in international assignments. International Journal of HRM, 26(3), 299–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.581637

- Singh, S. K., Vrontis, D., & Christofi, M. (2021). What makes mindful self-initiated expatriates bounce back, improvise and perform: Empirical evidence from the emerging markets. European Management Review, 19(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12456

- Spurk, D., Volmer, J., Orth, M., & Göritz, A. S. (2019). How do career adaptability and proactive career behaviours interrelate over time? An inter- and intraindividual investigation. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 93(1), 158–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12288

- Stoermer, S., Davies, S. E., & Froese, F. J. (2021). The influence of expatriate cultural intelligence on organizational embeddedness and knowledge sharing: The moderating effects of host country context. Journal of International Business Studies, 52(3), 432–453. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00349-3

- Stoermer, S., Lauring, J., & Selmer, J. (2020). The effects of positive affectivity on expatriate creativity and perceived performance: What is the role of perceived cultural novelty? International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 79, 155–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2020.09.001

- Swalhi, A., Mnisri, K., Amari, A., & Hofaidhllaoui, M. (2023). The role of ethical organizational climate in enhancing International executives’ individual and team creativity. International Journal of Innovation, 27(1m02). https://doi.org/10.1142/S136391962350010X

- Takeuchi, R., Yun, S., & Tesluk, P. E. (2002). An examination of crossover and spillover effects of spousal and expatriate cross-cultural adjustment on expatriate Outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 655–666. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.655

- Tonkin, K., Malien, S., Naswall, K., & Kuntz, J. (2018). Building employee resilience through wellbeing in organizations. Human Resources Development Quarterly, 29(2), 107–124. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21306

- Tsegaye, K. W., Su, Q., & Malik, M. (2019). Expatriate cultural values alignment: The mediating effect of cross-cultural adjustment level on innovative behaviour. Creativity and Innovation Management, 18(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12308

- Wang, K., & Holahan, P. (2017). The effect of monetary reward on creativity: The role of motivational orientation. Proceedings of the 50th Hawai International Conference on System Sciences, Hawai (pp. 224–233).

- Wayne, S., Shore, L., & Liden, R. (1997). Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 40(1), 82–111. https://doi.org/10.2307/257021

- Xu, S., Liu, P., Yang, Z., Cui, Z., & Yang, F. (2021). How does mentoring affect the creative performance of mentors: The role of personal learning and career stage. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(741139). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.741139

- Yu, X., Li, D., Tsai, C. H., & Wang, C. (2019). The role of psychological capital in employee creativity. Career Development International, 24(5), 420–437. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-04-2018-0103

- Zain, M., Kassim, N., & Kadasah, N. (2017). Isn’t it now a crucial time for Saudi Arabian firms to be more innovative and competitive? International Journal of Innovation Management, 21(03), 1750021. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919617500219

- Zaman, U., Nawaz, S., Anjam, M., Anwar, R. S., & Siddique, M. S. (2021). Human resource diversity management (HRDM) practices as a coping mechanism for xenophobia at transnational work-place: A case of a multi-billion-dollar economic corridor. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1883828

- Zhang, L., Bu, Q., & Wee, S. (2016). Effect of perceived organizational support on employee creativity: Moderating role of job stressors. International Journal of Stress Management, 23(4), 400–417. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000025

- Zhou, J., & George, J. M. (2001). When job dissatisfaction leads to creativity: Encouraging the expression of voice. Academy of Management Journal, 44(4), 682–696. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069410