Abstract

This study aimed to examine the relationships among workplace civility, social cohesion, and job embeddedness, and to measure the moderating effect of work overload on these relationships. Three hundred twelve respondents from various job sectors in Indonesia participated in this study. All hypotheses were examined using hierarchical multiple regression analysis using Hayes’ macro PROCESS. Workplace civility was positively and significantly related to social cohesion and employee job embeddedness. This study also found that social cohesion mediates the relationship between workplace civility and job embeddedness. Work overload was found to be a moderator in the relationship between workplace civility-job embeddedness and social cohesion-job embeddedness, such as these relationships are stronger when the work overload is low and vice versa.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study provide novel evidence of a relationship between civility, social cohesion and job embeddedness. Drawing on social exchange theory, relational cohesion theory, and the job demands-resources model, we uncovered a relationship between the workplace environment (e.g., workplace civility and social cohesion) and employee job embeddedness, and provided initial findings on this relationship. Our initial study provides a green light for future research and provides direction to gain a more nuanced understanding of workplace civility behavior and how these organizational factors can promote positive behavior among employees.

1. Introduction

The phenomenon of incivility in the workplace has dramatically increased in the past two decades, encouraging all parties to make strenuous efforts to promote civility in the work environment. Perceived civility in the workplace aids in attaining a mutually respectful work environment, in which communication is based on politeness norms that mandate that employees empathize with others, treat others with respect, and act with restraint (Andersson & Pearson, Citation1999). Workplace civility has been widely associated with individual behavior (e.g., work satisfaction, well-being, OCB, work engagement; Campbell et al., Citation2021; der Kinderen et al., Citation2020; Myers et al., Citation2016; Sawada et al., Citation2021), and group behavior (e.g., social climate, team humility, organization performance; Rego & Simpson, Citation2018; Sawada et al., Citation2021). Despite the strong link between workplace civility and positive employee attitudes and behavior, there still needs to be more research areas on this topic (Leiter et al., Citation2011) that will be addressed in the present study.

The present study tests a moderation mediation model to address the research need. Specifically, we examine social cohesion and job embeddedness as outcomes of civility climate and work overload as boundary conditions (see Figure ). In doing so, our study makes several contributions to the literature on civility climate. First, while previous research has identified civility climate is likely to increase the quality of social interactions, trust, and sense of community, which is possibly congruent with group cohesion (Morrison, Citation2008). Prior studies on social cohesion were mainly focused on various situations in the work environment, including inequality, incivility, and social justice (Coll et al., Citation2020; Jørgensen & Fallov, Citation2022; Moran & Mallman, Citation2019; Porath & Pearson, Citation2010; Thompson et al., Citation2017); and civility climate has not received attention. Drawing social exchange theory (SET; Blau, Citation1964) and COR theory (Hobfoll, Citation2001) as theoretical bases, we propose workplace civility to promote social cohesion. To the best of our knowledge, the relationship between workplace civility and social cohesion has never been explored; thus, we extend the relational cohesion theory by revealing that civility in the workplace fosters social cohesion.

Second, our study further uncovered the possible effect of workplace civility on job embeddedness. Previously, researchers focused more on incivility as an antecedent of job embeddedness. For example, workplace incivility has been shown to have a negative impact on job embeddedness and work engagement (Alola et al., Citation2019; Boo & Kim, Citation2013; Cahyadi et al., Citation2021; Rahim & Cosby, Citation2016). The present study uses a different angle by exploring the potential of civility climate as an antecedent of job embeddedness. Moreover, we also explore the relationship between job embeddedness and social cohesion in response to Coetzer et al. (Citation2019) study among Australian employees. The present study took a sample of employees in Indonesia who have significant differences from Australian culture, especially in terms of power distance and individualism (Hofstede et al., Citation2005). Hence, the study aims to provide empirical evidence on the relationship between cohesion and job embeddedness in different cultural contexts. Indonesia is the fourth-most populous country in the world; it can provide an exciting background for these issues.

Third, this study examines a complex model that places social cohesion as an intermediate relationship between workplace civility and job embeddedness and, at the same time, proposes work overload as the boundary condition for this relationship. Our study provides an alternative explanation for workplace civility-job embeddedness relationship process model by considering social cohesion. Moreover, in contrast to previous studies (e.g., Karatepe, Citation2013; Khorakian et al., Citation2018; Marques-Quinteiro et al., Citation2020) that considered work overload as the antecedent of job embeddedness, our study explores the role of work overload as a moderator. Perceived work overload can deplete personal resources, resulting in no resources left to carry out other activities (i.e., fulfilling other tasks and reducing their work-life balance). The consequence of work overload is that employees will recalculate the continuity of their work in the future; hence, in line with the conservation of resources (COR) theory, we reveal that work overload is associated with less job embeddedness.

In sum, our study offer valuable insights that can inform organizational practices by highlighting the significance of civility climate as a crucial group characteristic. This climate can promote group cohesion and an individual’s sense of job embeddedness within the work environment. By recognizing and fostering a positive team civility climate, organizations can create a conducive atmosphere that benefits both the group as a whole and individual employee. The next chapter will explain the theoretical basis and hypotheses. To test the research model, moderated mediated procedures were applied using a survey of 312 employees in various sectors in the methodology chapter. Results and discussion (including theoretical and practical implications) are explained before the chapter conclusion.

2. Theoretical background and hypothesis development

2.1. Workplace civility

Workplace civility is a behavior that promotes norms for mutual respect at work, including building empathic relationships and respect for others within a group (Pearson et al., Citation2000; Walsh et al., Citation2012). Civility involves a broader awareness that goes beyond oneself and demonstrates respect, empathy, and concern for others, forming positive community interaction patterns (Pearson et al., Citation2000). Because a civil work environment promotes mutual respect, promoting it is equivalent to efforts to minimize disrespectful behavior or workplace incivility (Andersson & Pearson, Citation1999). Furthermore, Leiter (Citation2021) specifically classified workplace civility in various terms (i.e., supervisor civility, coworker civility, and instigated civility) and showed that it was negatively associated with forms of incivility (e.g., supervisor incivility, supervisor intimidation, coworker incivility, coworker intimidation, instigated incivility, and instigated intimidation).

Researchers have identified the importance of promoting a civility climate to form a good social environment that can also influence the attitudes and behavior of individuals regarding their work environment. According to Osatuke et al. (Citation2009), civility in the workplace is most appropriate when approached from an organizational perspective rather than only focusing on individual behavior. As a process of social interaction, civility involves interactions between individuals, groups, or entire organizations (Pearson & Porath, Citation2005); As a result, perceived civility in the workplace shapes employees’ perceptions of their group. When employees feel they are treated with respect, they are more likely to have high levels of well-being and satisfaction and be more engaged in their jobs (Campbell et al., Citation2021; DiFabio et al., Citation2016; Gori & Topino, Citation2020). In this study, we investigate links between workplace civility, social cohesion, and job embeddedness and the role of work overload in these relationships through the lens of the social exchange theory (SET; Blau, Citation1964) and COR theory (Hobfoll, Citation2001).

2.2. Workplace civility and social cohesion

A cohesive climate is associated with collegial relationships, close friendships, and feelings of closeness and similarity within the group (Odden & Sias, Citation1997). Cohesiveness involves friendly relations, cooperation, and positive communication (Morrison, Citation2008). Members of a cohesive team tend to be more inclined to help one another and have high sensitivity to other members (Kidwell et al., Citation1997). At the individual level, group cohesion can act as a control (e.g., adherence to group norms, Beal et al., Citation2003) and can foster other positive attitudes and behaviors. Cohesion can also positively impact job satisfaction and turnover intention (Jiang et al., Citation2017), self-determination motivation (Pacewicz et al., Citation2020), and affective commitment (Charbonneau & Wood, Citation2018). However, group cohesion can negatively influence ethical decision-making; groups with high cohesion tend to be involved in unethical behavior to benefit the group (Alleyne et al., Citation2019).

Group cohesion is a two-dimensional construct consisting of task cohesion and social cohesion. In the present study, we focus on social cohesion as the strength of group members’ motivation to develop and extend social relationships. As a form of social interaction, poor interaction between members in a group can lead to poor interpersonal relationships that harm team cohesion (Morrison et al., Citation2015). Correspondingly, perception of civility implies that employees perceive a mutually respectful work environment; communication is based on politeness norms, where employees empathize with others, treat others with respect, and act with restraint (Andersson & Pearson, Citation1999). Politeness and respect can trigger more effective, two-way communication and openness, which stimulates employee involvement in the group. In different contexts, incivility has been shown to have adverse effects on employee exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect (Coll et al., Citation2020). Porath and Pearson (Citation2010) have suggested that civility can foster teamwork, whereas incivility causes a reduction in employee enthusiasm and increases stress. Group members in an uncivil environment will be less connected, have low trust in other group members, and less group cohesion (Porath & Pearson, Citation2010). Civility is likely to increase the quality of interpersonal interactions, social climate, mutual trust, and sense of community, which is congruent with group cohesion (Morrison, Citation2008; Sawada et al., Citation2021). Thus, we hypothesized the following:

H1:

workplace civility is positively related to social cohesion

2.3. Workplace civility and job embeddedness

Job embeddedness theory suggests that a set of processes influence an individual’s decision to stay on the job (Holtom & Darabi, Citation2018; Mitchell et al., Citation2001). Fit, links, and sacrifice are the three components of job embeddedness. They refer to the individual’s fit to the organization or job, number of links, and losses incurred if the employee decides to leave the organization, respectively (Holtom et al., Citation2006). Fit and link in the context of job embeddedness can be related to the work environment. For example, the links to entities in the organization, such as work networks and structure with other parts, teamwork, and friendship relationships outside the work environment. The greater the number and the more important links between the individual and the entity in the organization, the more a worker is bound to the organization (Mitchell et al., Citation2001).

A civil workplace is one in which the workers have awareness that extends beyond the self, preserve the norms of mutual respect and concern for the well-being of others, and demonstrate empathy (Pearson et al., Citation2000; Walsh et al., Citation2012). Although the direct relationship between workplace civility and job embeddedness has never been studied, we argue that the two are interrelated for several reasons: First, SET suggests that the civil workplace is a source of exchange in the form of affection, and a comfortable environment can create positive emotions in employees, increase employee well-being (der Kinderen et al., Citation2020), OCB (Myers et al., Citation2016), and work engagement (Gupta & Singh, Citation2021; Sawada et al., Citation2021). Civility climate also reduced employee deviation and burnout (Clark & Walsh, Citation2016; Laschinger & Read, Citation2016). Second, unlike civility (Andersson & Pearson, Citation1999), workplace incivility has been widely studied in relation to job embeddedness and turnover intention (Alola et al., Citation2019; Tricahyadinata et al., Citation2020) and engagement (Boo & Kim, Citation2013; Cahyadi et al., Citation2021; Rahim & Cosby, Citation2016). Incivility has also been empirically proven to be related to employee exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect (Coll et al., Citation2020). Third, ethics and norms are central to workplace civility and incivility (Andersson & Pearson, Citation1999; Marchiondo et al., Citation2018). Accordingly, job embeddedness is closely related to the interaction of individuals with the organization, including how they perceive the policies, procedures, and practices designed to maintain civility in the workplace. Thus, we assume that employees with favorable perceptions of civility in the workplace are more embedded in their jobs and organizations. Therefore, we hypothesized the following:

H2:

workplace civility is positively related to job embeddedness

2.4. Social cohesion and job embeddedness

According to SET, cohesion is formed through interactions between individuals and other members of the organization in the form of sharing, having the same goals and values, interpersonal closeness, and helping each other, which is consistent with job embeddedness theory. In particular, employees perceive that their values fit well with the group, have many links with other organization members, and have a high degree of embeddedness (Holtom & Darabi, Citation2018; Holtom et al., Citation2006). Organizational links include connections between individuals and groups within an organization. The higher the quality of the relationship created and the more influential the link is for employees, the more employees become embedded (Mitchell et al., Citation2001). Fit refers to the employee perceptions of their suitability in terms of professional values with the organization. Social cohesion refers to friendly relations, cooperation, feelings of closeness and similarity within the group, and positive communication (Morrison, Citation2008; Odden & Sias, Citation1997). Finally, sacrifices refer to perceived financial and non-financial (e.g., social or psychological) losses related to leaving the job (Coetzer et al., Citation2017, Citation2019). Furthermore, the empirical evidence recently confirmed a positive relationship between cohesion to job embeddedness (Coetzer et al., Citation2019). In short, employees with favorable perceptions of social cohesion are more embedded in their jobs/organizations. Therefore, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H3:

Social cohesion is positively related to job embeddedness

Furthermore, based on SET and the above theoretical exposition concerning H1 and H3, we posit that workplace civility influences job embeddedness via social cohesion. In other words, workplace civility leads employees to obtain higher perceived social cohesion. Given that cohesion has a positive effect on job embeddedness (Coetzer et al., Citation2019), it can be assumed that higher social cohesion fosters a comfortable environment that encourages employees to stay in their organization. In this process, social cohesion serves as a unique psychological mechanism that mediates the effect of workplace civility on job embeddedness. In a similar context, positive emotions also strengthen perceptions of cohesion, which is related to an increased likelihood (intent) of remaining at the organization (Price & Collett, Citation2012). Based on the previous explanation, we argue that workplace civility and group cohesion are both representative of work environments that have a positive emotional impact, and job embeddedness as the degree to which employees want to stay in the organization is a logical consequence of the positive emotions presented by workplace civility and group cohesion. Therefore, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H4:

Social cohesion mediates the relationship between workplace civility and job embeddedness.

2.5. The moderating effect of work overload

Work overload occurs when employees feel that their expected workload, responsibilities, and time pressures exceed their ability to complete their work (Kahn et al., Citation1964). It is a condition that describes the availability of employee resources (e.g., emotional, time, and energy) to meet work targets. In this study, employees’ positive perceptions of workplace civility and social cohesion are hypothesized to increase their embeddedness within the organization; however, work overload may moderate this relationship. Previous researchers have linked work overload to various negative consequences on employee attitudes and behavior. For example, the presence of work overload places strain on workers (e.g., emotional exhaustion and stress) that in turn results in adverse outcomes (e.g., OCB, less creativity, ineffective job performance, and bullying) (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007; Islam et al., Citation2019; Karatepe, Citation2013; Schaufeli & Taris, Citation2005).

Present study uses COR theory to explain the role of work overload in the formation of job embeddedness through workplace civility and cohesion. Several reasons underly the role of work overload as a boundary condition. First, COR theory is built from the concept of resources, which are interpreted as valuable values for the individual to maintain their position in the organization. These valuable resources can be in the form of conditions, energy, objects, individual characteristics, or social support (Halbesleben, Citation2010). Work overload has been confirmed as a source of stress and burnout (Kimura et al., Citation2018), so it can deplete valuable individual resources (Khorakian et al., Citation2018); for example, employees who have overloaded tasks would lose their precious time with family. The depletion of further valuable resources can be the basis for an employee’s consideration to stay or leave the organization based on the COR assumption.

Second, using the COR framework, Khorakian et al. (Citation2018) and Karatepe (Citation2013) confirmed work overload to be a determinant of job embeddedness. Another explanation of work overload as a moderator can be seen in the JD-R model, which identifies two sources (job and personal) as determinants of work engagement; situational factors such as job demands will moderate the strength of the relationship. Bakker and Demerouti (Citation2007) provided three examples of work demands: role conflict, role overload, and role ambiguity. Overall, the JD-R model facilitates how job demands or resources are closely related to employees’ job embeddedness (Karatepe, Citation2013; Khorakian et al., Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2021; Zabrodska et al., Citation2018), job satisfaction, and work-lice balance (Ahmad & Islam, Citation2019; McDaniel et al., Citation2021; Poulose & Dhal, Citation2020).

Accordingly, using COR theory, we predicted that the main effects of workplace civility and cohesion on job embeddedness would decrease in line with the high work overload. Therefore, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H5:

Work overload influences the strength of the relationship between workplace civility and job embeddedness such that it is strong when work overload is low and vice versa.

H6:

Work overload influences the strength of the relationship between social cohesion and job embeddedness such that it is strong when work overload is low and vice versa

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and procedure

This study adopted purposive and convenience sampling methods to select participants from the student centers of four universities in Indonesia. Data collection was carried out when cases of COVID-19 in Indonesia experienced a drastic increase (April to August 2021); thus, purposive and convenience sampling was selected by contacting colleagues at the four universities who gave their consent to be involved in the study. Since a crisis causes data collection in this study to be highly unstructured and unpredictable (Lin et al., Citation2017), we argue that this approach is well-suited. More than 500 undergraduates and master’s registered students at four universities who worked were invited to participate via email. The companies were from different industries, including education, manufacturing, SMEs, banking and financial services, and government institutions.

There were two phases of data collection. Phase 1 was performed between March and April of 2021, and Phase 2 was performed between June and August of 2021. In the first phase, the participants were asked to report their biographical information (gender, age, education, years of service, company sectors) and their perceptions of workplace civility and social cohesion at their organization.

The second phase was carried out 4 weeks after the first; participants were asked to report their workload and job embeddedness. A total of 379 complete and usable questionnaire responses were obtained in Phase 1, while in Phase 2, only 48 percent (182 of respondents) answered an emailed questionnaire in a period of 4 weeks. The low response in phase two was due to Indonesia experiencing an explosion of COVID-19 cases, which caused many respondents to be unable to be contacted or not to respond to the email. We extended the data collection period to 8 weeks to obtain 312 complete and usable questionnaire responses (82 percent). This sample size exceeds the minimum sample to produce a yield of power of around 0.80 (effect size medium = 0.15, alpha value 0.05, number of predictors 2) based on the calculation of the G*power program for multiple regression analysis. Moreover, the sample size exceeded the minimum of 237 and 300 for multiple regression (Islam et al., Citation2023; Kelley & Maxwell, Citation2003).

As shown in Table , participants came from various sectors, including education (19.3%), manufacturing (16.1%), and SMEs (31.9%). More than half of the respondents were women (66.3%), average age of 29.96 years (SD = 7.27), 53.3% held bachelor’s degrees or above, and the majority of them had worked for 1 to 3 years (44.1%).

Table 1. Respondents’ biographical characteristics

3.2. Measures

All scales were anchored on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to (5) (“strongly agree”). We followed a three-stage back-translation procedure to translate the originally English scales into Indonesian (Brislin, Citation1980; Jia et al., Citation2020). First, we assigned a professional translator to translate the original English scale items into Indonesian. Second, two other experts independently back-translated the Indonesian scale items into English (Jia et al., Citation2020). Finally, we discussed with three experts in human resources and organizational behavior to validate the content by reviewing the accuracy of each translated item. Workplace civility was measured using four items of the Civility Norms Questionnaire-Brief (CNQ-B) to cover employees’ experiences of workgroup civility norms (der Kinderen et al., Citation2020; Walsh et al., Citation2012). One example of an item is “Your coworkers do not accept rude behavior.” The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .94.

We used a five-item scale adapted from Manata (Citation2016) to measure team cohesiveness; respondents considered their social cohesion in their company. Two examples of the items are “I do not enjoy being a part of my current workgroup/team” and “I would have rather preferred being in members with other people.” A higher value reflects a stronger level of social cohesion. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .91. Work overload was measured using a four-item scale adapted from Schaufeli and Taris (Citation2005). One example of an item is, “You have too much work to do.” The alpha coefficient for the scale was .89. Finally, we used the nine-item scale developed by Crossley et al. (Citation2007) to measure job embeddedness. One example of the items on that scale is “I feel embedded in this organization.” The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.84.

3.3. Control variables

We included demographic variables (age, education, tenure, and marital status) as control variables because they were previously associated with job embeddedness (Dechawatanapaisal, Citation2018; Holtom et al., Citation2006; Huning et al., Citation2020). We also tested for mean differences in job embeddedness scores by gender, age, education, and tenure. For gender, an independent t-test was used and resulted in a t-value of −.22 (sig .84 > .05), indicating there was no significant difference in job embeddedness based on gender. The analysis of variance revealed that job embeddedness does not differ by age, education, or tenure (sig > .05).

4. Results

4.1. Common-method bias and exploratory factor analysis

Data collection in this study was performed using a single survey instrument based on the same source for all the variables studied; thus, it was necessary to address the issue of common method bias. To reduce concerns regarding common method variance (CMV), data collection in this study used a design time-lag approach (Law et al., Citation2016). We also tested for differences in the scores for job embeddedness based on demographic data to ensure that there were no biases based on age, gender, education, or tenure (see Table ). In addition, we performed a Harman one-factor test to evaluate whether the common method was biased in the data we used (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012).

Table 2. Evaluation of the measurement model

Findings of the factor analysis produced a four-component solution based on the eigenvalue = 1.0. Overall, these four components made up 80.07% of the total variance. The factor analysis results also revealed that none of the components had a dominant percentage above 50%, indicating that the variance was spread across the four components. Thus, we are certain that the CMV in this study did not significantly influence the results (see Table ).

As shown in Table , convergent and discriminant validity were tested. First, all the standardized factor loadings were greater than .70, and the average variances extracted (AVEs) of all the variables were above 0.5 (ranging from .71 to .82), and construct reliability (CR) was > 0.70, indicating that convergent validity was fulfilled (Hair et al., Citation2019). Discriminant validity indicates that the measures of constructs are distinguished from each other (Hair et al., Citation2019) or if theoretically each construct that should not be highly related to each other (Hubley, Citation2014). This study uses Fornel and Lacker’s (Citation1981) criteria by comparing the root of AVE values with all correlations between variables. As shown in Table III, the findings show that the root square values of the AVEs (diagonal bold italic) were more significant than the correlation between variables; thus, discriminant validity for the measurement model was also fulfilled (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and correlations of the study variables

4.1.1. Descriptive statistics

Table presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the variables. As expected, workplace civility was significantly positively related to social cohesion (r = .34, p < .01) and job embeddedness (r = .49, p < 0.01). Social cohesion was positively related to job embeddedness (r = .35, p < .01), and work overload was positively related to job embeddedness (r = .19, p < .01). These results provide initial support for the proposed relationships between workplace civility, social cohesion, and job embeddedness.

4.2. Hypothesis testing

We used the PROCESS macro v.4.0 developed by Hayes (Citation2017) to test the moderated mediation model. The 15 macro-process model was used to test the mediation moderation model (Hayes, Citation2017). Table IV presents the results for all the study’s hypotheses. First, workplace civility was found to be positively related to social cohesion (β = .32, p < .01), workplace civility was positively related to job embeddedness (β = .37, p < .01), and social cohesion was positively related to job embeddedness (β = .18, p < .01). Thus, H1-H3 were supported. Second, the results showed that social cohesion mediates the relationship between workplace civility and job embeddedness; the indirect effect is significantly positive (β = .05, SE = .02). Next, we used bootstrapping estimation for additional testing on indirect effects and found results that supported the significance of the previous results (the confidence interval [CI] using a 5,000-bootstrap sample that did not include 0; CI was .02 and .09). Therefore, H4 was supported.

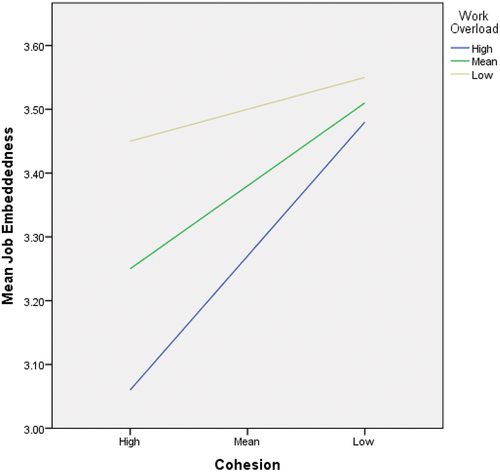

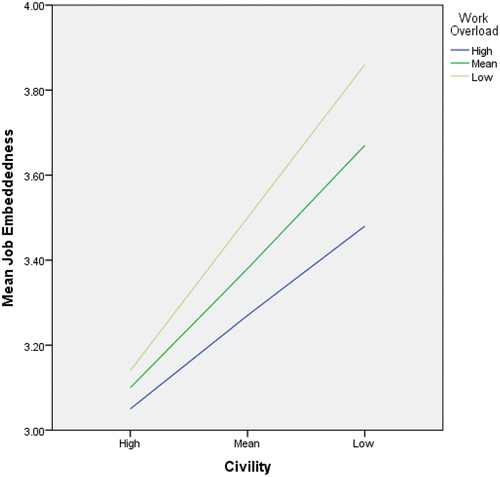

Finally, H5 and H6 were moderation hypotheses suggesting that work overload moderates the relationship between workplace civility and job embeddedness (H5) and social cohesion and job embeddedness (H6). As shown in Table , the two interaction variables were significant. The interaction term of workplace civility × work overload showed a negative and significant parameter (β = −.10, t = −2.25, p < .05), supporting H5. The conditional effect of workplace civility on job embeddedness is stronger under a low-level of work overload (effect = .45; t-values = 7.89; CI = .34–.56) and weaker under high-level work overload (effect = .28; t-values = 4.67; CI = .16–.36).

Table 4. Results of the moderated mediation analyses (PROCESS: model 15)

Figure shows that the conditional effect of workplace civility on job embeddedness s based on the values of the moderator. In this study, we use −1 SD, mean, and + 1 SD as condition values of the moderator. Figure shows the conditional effect of workplace civility on job embeddedness based on work overload values of .27 (−1 SD), .37 (mean), and .45 (+1 SD), which we labeled as “low,” “medium,” and “high” in work overload. As shown in Figure , workplace civility had a positive effect on job embeddedness for all levels of work overload. The effect is higher with the increase in work overload, indicating that work overload has a positive tone, where an increase in work overload will increase the effect of workplace civility on job embeddedness.

Figure 2. Moderating effect of work overload on the relationship between workplace civility and job embeddedness.

H6 proposed that work overload moderates the relationship between social cohesion and job embeddedness, and this hypothesis was supported (β= −.12, t = −2.49, p < .05). In contrast to its positive role in the workplace civility-job embeddedness relationship, work overload has a negative role in the social cohesion-job embeddedness relationship. Table shows that the effect of social cohesion on job embeddedness was only significant when work overload was at a low level (effect = .29; t-values = 4.74; CI = .17–.41), and vice versa. The relationship becomes insignificant when work overload is at a high level (effect = .08; t-values = 1.27; CI = −.04–.20). However, H6 was still supported.

A different situation is shown in the moderation model of the relationship between cohesion and job embeddedness. As shown in Figure , work overload plays a negative role, where the effect of cohesion on job embeddedness becomes insignificant when work overload is at a high level. Figure shows the conditional effect of cohesion on job embeddedness based on work overload values of .30 (−1 SD), .17 (mean), and .08 (+1 SD), where the effect is only significant at “low” and “medium,” and not for “high” level in work overload. However, the conditional effects on the three percentiles of the work overload distribution are all positive. However, this positive association was more significant in individuals with lower perceived job embeddedness, and was statistically significant only among individuals with low and moderate work overload.

5. Discussion

The primary purpose of this study is to explore the impact of workplace civility on job embeddedness through a mediation moderation model by treating social cohesion as a mediator and work overload as a moderator. These reported results support a relationship between higher-level workplace civility, workgroup cohesiveness, and job embeddedness. This study’s moderated and mediation model approach provides evidence of the direct and indirect impact of workplace civility on job embeddedness through social cohesion. Moreover, the strength of the effect of workplace civility and social cohesion on job embeddedness is highly dependent on the perceived work overload of the employees. Work overload in our study gives mixed results, such as strengthening the effect of workplace civility on job embeddedness and, conversely, weakening the effect of social cohesion on job embeddedness. In particular, workplace civility’s effects moved from weak to strong for employees who rated low to high-level of work overload. Conversely, a high level of perceived work overload causes social cohesion to have no significant effect on job embeddedness; this effect was only found when employees perceived a low level of work overload. Thus, perceived work overload among employees is a critical boundary condition of workplace civility, social cohesion, and job embeddedness. In the following section, we will explore the implications of our findings for both theoretical and practical applications in organizational settings. Additionally, we will address the limitations of our current investigation and propose several potential directions for future research in this field.

5.1. Theoretical implications

The outcomes of our study align with the Social Exchange Theory (SET) and Conservation of Resources (COR) theory in explaining the impacts of workplace civility within organizations. However, our findings also provide further insights beyond what these theories have previously suggested. First, the results provide novel evidence of a relationship between civility and social cohesion that was previously untested. For example, previous researchers have primarily associated workplace civility with work satisfaction and well-being (Campbell et al., Citation2021; der Kinderen et al., Citation2020),OCB (Myers et al., Citation2016), work engagement (Sawada et al., Citation2021), and employee voice (Achmadi et al., Citation2022). Therefore, in the civil workplace, employees feel mutually respectful and communicate based on the norms of decency, mutual empathy, and respect in interactions in the work environment (Andersson & Pearson, Citation1999) so that cohesion among employees will be more easily formed. In line with the SET argument, the civility climate within the organization can encourage the quality of social interaction, cooperation, mutual trust, and enthusiasm so that the interactions created are less stressful (Clark & Watson, Citation2016; Laschinger & Read, Citation2016; Porath & Pearson, Citation2010); hence, it is logical that perceived workplace civility fostering social cohesion (Morrison, Citation2008; Sawada et al., Citation2021).

Second, our study is the first to examine the relationship between workplace civility and job embeddedness; our findings provide initial support for the vital role of workplace civility in encouraging positive behaviors (e.g., job embeddedness) among employees. In line with the SET assumption, employees perceive a mutually respectful politeness norm in the workplace as a valuable source of non-financial exchange on which to base future exchanges. When individuals perceive civility as positive feelings and emotions in their interactions, they tend to develop stronger ties with their groups (Lawler & Yoon, Citation1996). The results of the study used a different perspective in studying job embeddedness and employee intentions to stay, which previously focused more on workplace incivility behavior (Alola et al., Citation2019; Boo & Kim, Citation2013; Cahyadi et al., Citation2021; Rahim & Cosby, Citation2016; Tricahyadinata et al., Citation2020). Conversely, by encouraging a civility climate, job embeddedness can be promoted. Therefore, workplace civility that encourages quality social interaction through mutual trust and respect contributes to the “link” component that leads to teamwork and friendship relationships inside and outside the work environment as a prominent part of job embeddedness.

Third, the present study confirms a complex model that places social cohesion as an intermediate relationship between workplace civility and job embeddedness and, at the same time, proposes work overload as the boundary condition for this relationship. These findings can be discussed from two points of view. The first point concerns the partial mediating role of cohesion (Coetzer et al., Citation2019), which has been confirmed as a mediator of the job embeddedness—turnover relationship. Hence, our study can provide an alternative explanation for workplace civility in the job embeddedness relationship process model by considering social cohesion. The second point concerns the role moderating effect of work overload. Our study found a different moderating role for work overload in the proposed relationship model.

In the first situation, work overload has a positive direction, where the effect of civility climate on job embeddedness significantly increases along with an increase in perceived work overload for employees. On the other hand, work overload leads to negativity in the relationship between cohesion and job embeddedness. The effect of social cohesion on job embeddedness decreases drastically along with increased work overload. Based on COR theory, both workplace civility and cohesion are valuable resources for calculating employees’ stays in the organization. Similarly, the JD-R model (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007) suggests that work overload (job demands) moderates the relationship between job resources (workplace civility and social cohesion) and work engagement. Hence, our study extends the JD-R model by placing job embeddedness as the primary focus. In short, we offer a more comprehensive theoretical framework to explain social cohesion by relying on SET and integrating job embeddedness and work overload using the COR frameworks into a single model.

Finally, the results prove that job embeddedness is positively correlated with work overload. In contrast to Khorakian et al. (Citation2018) and Karatepe (Citation2013), who confirmed that work overload was negatively associated with embeddedness, we found the opposite relationship. However, the positive relationship between work overload and job embeddedness can be explained by the theory of job embeddedness itself. For example, overloaded employees are likely to spend more time at work and, thus, have more links and connections than standard jobs. The second element of job embeddedness is fit, which relates to employees’ subjective assessment of whether they feel compatible with their current workload. Additionally, sacrifice, which involves evaluating the potential material losses associated with leaving the organization, is heavily influenced by job opportunities elsewhere. In the context of COR theory, employees may experience a trade-off where they sacrifice time and resources with their families due to work overload. Hence, they will compare what they may gain from other resources at work, such as relationships and greater rewards, as a means of exchanging workload.

5.2. Practical implications

Our study has practical implications for fostering a climate of civility in the workplace to promote social cohesion and enhance employee job embeddedness. Since civility is closely connected to societal norms and culture, cultivating politeness values should be integrated into the organizational culture and value system. One practical approach is introducing and reinforcing these values during the early socialization process when new employees join the organization. By establishing civility as a foundational element for interaction within the organization, new employees can develop a solid understanding of the importance of civility and how it aligns with the organization’s values.

Second, managers can consider creating formal regulations to set ethical standards and norms that promote climate civility and reduce incivility. Supervisors and managers must be able to serve as role models for employees in order to communicate effectively with them. Thus, companies need to train line supervisors and managers on effective communication by prioritizing the norms of politeness that apply to local communities. By encouraging civility in the workplace, organizations can develop social cohesion and promote job embeddedness. Specifically, ethical standards are established through formal regulations, role modelling, and the integration of person-organizational fit via selection procedures.

Third, the results of this study also found that social cohesion is a determining factor for job embeddedness, and work overload moderates this relationship. This indicates that job embeddedness can be improved by creating social cohesion within the organization; management still needs to pay attention to work overload. Although most respondents (above 50 percent) in this study came from SMEs that tend to apply multi-tasking methods to their employees, efforts to balance workload, time, and employee competencies need attention. Redesigning task load needs to be carried out by management to ensure the suitability of competences, loads, and time so as not to put pressure on employees. The initial step is to ask employees to fill out a form regarding their current tasks to detect whether certain employees or sections have an overload so that further policies can be implemented.

5.3. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered in future research. First, because the study was conducted only in Indonesia, there may be some strengths and limitations in generalizability. The results of this study may be generalized to Asian countries, which tend to have relatively similar national cultures in terms of high power distance and collectivism (Hofstede et al., Citation2005). However, the combination of high power distance and collectivism may make research results for that country different from those of Western countries with low power distance and more individualism. In addition, civility is related to the norms that apply to a community; thus, future research should test the generalizability of this study in cross-cultural settings to better understand workplace civility, group cohesion, and employee job embeddedness relationships. Second, the sample in this study consisted of students who worked in various sectors identified through a purposive approach. However, it is not known to what extent these students worked, as they likely did not work full time while studying. This limitation could affect the generalizability of the results and anticipate future studies. Third, this study used single-source data, which could increase the risk of CMV (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012). While the Harmans’ single-factor test results and time-lag design employed in this study have alleviated concerns about CMV, as noted by Podsakoff et al. (Citation2012), future research could benefit from utilizing multiple sources such as supervisors, subordinates, and managers to strengthen the overall study (Ruiz‐Palomino et al., Citation2021). Finally, although this study uses a time-lag design to facilitate testing of the mediation model (Law et al., Citation2016), we still recommend that further studies employ a longitudinal or experimental study design to cope with causality limitations in this model (Mizani et al., Citation2022).

6. Conclusion

Our study aimed to examine the relationships among workplace civility, social cohesion, and job embeddedness, and to uncover the moderating effect of work overload on these relationships. Drawing on SET and COR theory, we found that the workplace environment (e.g., workplace civility and social cohesion) can promote employee job embeddedness. This study also found that social cohesion mediates the relationship between workplace civility and job embeddedness. Extending previous theories, we demonstrated that workplace civility can elicit a positive response from employees, which can result in positive outcomes that increase job embeddedness. We hope our initial study provides a green light for future research and provides direction to gain a more nuanced understanding of workplace civility behavior and how these organizational factors can promote positive behavior among employees.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Achmadi

Achmadi is a senior lecturer at Universitas Teknologi Muhammadiyah Jakarta, Indonesia. His research interests include organizational behavior, strategic management, and marketing. Email: [email protected]

Hendryadi

Hendryadi is a lecturer at Sekolah Tinggi Ilmu Ekonomi Indonesia Jakarta and a Doctorate Student in Management at Universitas Pancasila. His academic interests revolve around human resource management, organizational behavior, Islamic work ethics, workplace incivility, and quantitative research methods. Email: [email protected]

Amelia Oktrivina

Amelia Oktrivina is an associate professor at the Economics and Business Faculty of Universitas Pancasila. Her research interests include tax avoidance, auditing, and financial management. Email: [email protected].

References

- Achmadi, A., Hendryadi, H., Siregar, A. O., & Hadmar, A. S. (2022). How can a leader’s humility enhance civility climate and employee voice in a competitive environment? Journal of Management Development, 41(4), 257–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-11-2021-0297

- Ahmad, R., & Islam, T. (2019). Does work and family imbalance impact the satisfaction of police force employees? A “net or a web” model. Policing: An International Journal, 42(4), 585–597. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-05-2018-0061

- Alleyne, P., Haniffa, R., & Hudaib, M. (2019). Does group cohesion moderate auditors’ whistleblowing intentions? Journal of International Accounting, Auditing & Taxation, 34, 69–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2019.02.004

- Alola, U. V., Olugbade, O. A., Avci, T., & Öztüren, A. (2019). Customer incivility and employees’ outcomes in the hotel: Testing the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Tourism Management Perspectives, 29, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.10.004

- Andersson, L. M., & Pearson, C. M. (1999). Tit for Tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 452–471. https://doi.org/10.2307/259136

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands‐resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

- Beal, D. J., Cohen, R. R., Burke, M. J., & McLendon, C. L. (2003). Cohesion and performance in groups: A meta-analytic clarification of construct relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(6), 989–1004. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.6.989

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Transaction Publishers.

- Boo, S., & Kim, J. (2013). Comparison of negative eWOM Intention: An exploratory study. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 14(1), 24–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2013.749381

- Brislin, R. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In H. Triandis & J. Berry(Eds.), Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology (2nd ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

- Cahyadi, A., Hendryadi, H., & Mappadang, A. (2021). Workplace and classroom incivility and learning engagement: The moderating role of locus of control. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 17(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-021-00071-z

- Campbell, L. A., LaFreniere, J. R., Almekdash, M. H., Perlmutter, D. D., Song, H., Kelly, P. J., Keesari, R., Shannon, K. L., & Ren, T. (2021). Assessing civility at an academic health science center: Implications for employee satisfaction and well-being. PLOS ONE, 16(2), e0247715. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247715

- Charbonneau, D., & Wood, V. M. (2018). Antecedents and outcomes of unit cohesion and affective commitment to the Army. Military Psychology, 30(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/08995605.2017.1420974

- Clark, O. L., & Walsh, B. M. (2016). Civility climate mitigates deviant reactions to organizational constraints. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(1), 186–201. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-01-2014-0021

- Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (2016). Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. In Methodological issues and strategies in clinical research, 4th ed (pp. 187–203). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14805-012

- Coetzer, A., Inma, C., & Poisat, P. (2017). The job embeddedness-turnover relationship. Personnel Review, 46(6), 1070–1088. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-12-2015-0312

- Coetzer, A., Inma, C., Poisat, P., Redmond, J., & Standing, C. (2019). Does job embeddedness predict turnover intentions in SMEs? International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 68(2), 340–361. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-03-2018-0108

- Coll, K. A., Bain, K., Tenney, E. R., & Kreps, T. A. (2020). Battling incivility: Increasing willingness to voice through amplification. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2020(1), 21444. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2020.217

- Crossley, C. D., Bennett, R. J., Jex, S. M., & Burnfield, J. L. (2007). Development of a global measure of job embeddedness and integration into a traditional model of voluntary turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1031–1042. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1031

- Dechawatanapaisal, D. (2018). The moderating effects of demographic characteristics and certain psychological factors on the job embeddedness – turnover relationship among Thai health-care employees. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 26(1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-11-2016-1082

- der Kinderen, S., Valk, A., Khapova, S. N., & Tims, M. (2020). Facilitating eudaimonic well-being in mental Health care organizations: The role of servant leadership and workplace civility climate. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041173

- DiFabio, A., Giannini, M., Loscalzo, Y., Palazzeschi, L., Bucci, O., Guazzini, A., & Gori, A. (2016). The challenge of fostering healthy organizations: An empirical study on the role of workplace relational civility in acceptance of change and well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01748

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gori, A., & Topino, E. (2020). Predisposition to change is linked to job satisfaction: Assessing the mediation roles of workplace relation civility and insight. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 2141. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062141

- Gupta, A., & Singh, P. (2021). Job crafting, workplace civility and work outcomes: The mediating role of work engagement. Global Knowledge, Memory & Communication, 70(6/7), 637–654. https://doi.org/10.1108/GKMC-09-2020-0140

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Halbesleben, J. R. (2010). A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. In A. Bakker & M. Leiter (Eds.), Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (pp. 102–117). Psychology Press.

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approac. Guilford publications.

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the Nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (2nd ed.). Mcgraw-hill.

- Holtom, B. C., & Darabi, T. (2018). Job embeddedness theory as a tool for improving employee retention. In M. Coetzee, I. Potgieter, & N. Ferreira (Eds.), Psychology of retention (pp. 95–117). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98920-4_5

- Holtom, B. C., Mitchell, T. R., & Lee, T. W. (2006). Increasing human and social capital by applying job embeddedness theory. Organizational Dynamics, 35(4), 316–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2006.08.007

- Hubley, A. M. (2014). Discriminant validity BT - Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. (A. C. Michalos, Ed.), Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_751

- Huning, T. M., Hurt, K. J., & Frieder, R. E. (2020). The effect of servant leadership, perceived organizational support, job satisfaction and job embeddedness on turnover intentions. Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, 8(2), 177–194. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBHRM-06-2019-0049

- Islam, T., Ahmad, S., & Ahmed, I. (2023). Linking environment specific servant leadership with organizational environmental citizenship behavior: The roles of CSR and attachment anxiety. Review of Managerial Science, 17(3), 855–879. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00547-3

- Islam, T., Ahmed, I., & Ali, G. (2019). Effects of ethical leadership on bullying and voice behavior among nurses. Leadership in Health Services, 32(1), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHS-02-2017-0006

- Jiang, H., Ma, L., Gao, C., Li, T., Huang, L., & Huang, W. (2017). Satisfaction, burnout and intention to stay of emergency nurses in Shanghai. Emergency Medicine Journal, 34(7), 448–453. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2016-205886

- Jia, J., Yan, J., Jahanshahi, A. A., Lin, W., & Bhattacharjee, A. (2020). What makes employees more proactive? Roles of job embeddedness, the perceived strength of the HRM system and empowering leadership. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 58(1), 107–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12249

- Jørgensen, A., & Fallov, M. A. (2022). Urbanization and the organization of territorial cohesion – results from a comparative Danish case-study on territorial inequality and social cohesion. Journal of Organizational Ethnography, 11(1), 64–78. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOE-01-2021-0006

- Kahn, R. L., Wolfe, D. M., Quinn, R. P., Snoek, J. D., & Rosenthal, R. A. (1964). Organizational stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity. In R. L. Khan (Ed.), Organizational stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity (pp. 470). John Wiley.

- Karatepe, O. M. (2013). The effects of work overload and work‐family conflict on job embeddedness and job performance. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(4), 614–634. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111311322952

- Kelley, K., & Maxwell, S. E. (2003). Sample size for multiple regression: Obtaining regression coefficients that are accurate, not simply significant. Psychological Methods, 8(3), 305–321. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.8.3.305

- Khorakian, A., Nosrati, S., & Eslami, G. (2018). Conflict at work, job embeddedness, and their effects on intention to quit among women employed in travel agencies: Evidence from a religious city in a developing country. International Journal of Tourism Research, 20(2), 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2174

- Kidwell, R. E., Mossholder, K. W., & Bennett, N. (1997). Cohesiveness and organizational citizenship behavior: A multilevel analysis using work groups and individuals. Journal of Management, 23(6), 775–793. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639702300605

- Kimura, T., Bande, B., & Fernández-Ferrín, P. (2018). Work overload and intimidation: The moderating role of resilience. European Management Journal, 36(6), 736–745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2018.03.002

- Laschinger, H. K. S., & Read, E. A. (2016). The effect of authentic leadership, person-job fit, and civility norms on New Graduate nurses’ experiences of coworker incivility and burnout. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 46(11), 574–580. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000407

- Lawler, E. J., & Yoon, J. (1996). Commitment in exchange relations: Test of a theory of relational cohesion. American sociological review, 61(1), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096408

- Law, K. S., Wong, C.-S., Yan, M., & Huang, G. (2016). Asian researchers should be more critical: The example of testing mediators using time-lagged data. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 33(2), 319–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-015-9453-9

- Leiter, M. P. (2021). Assessment of workplace social encounters: Social profiles, burnout and engagement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073533

- Leiter, M. P., Laschinger, H. K. S., Day, A., & Oore, D. G. (2011). The impact of civility interventions on employee social behavior, distress, and attitudes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(6), 1258–1274. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024442

- Lin, X., Xu, Z., Rainer, A., Robert Patric, R., Lachlan, S., & Kenneth, A. (2017). Research in crises: Data collection suggestions and practices. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

- Manata, B. (2016). Exploring the association between relationship conflict and group performance. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research & Practice, 20(2), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/gdn0000047

- Marchiondo, L. A., Cortina, L. M., & Kabat-Farr, D. (2018). Attributions and appraisals of workplace incivility: Finding light on the dark side? Applied Psychology, 67(3), 369–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12127

- Marques-Quinteiro, P., Santos, C. M. D., Costa, P., Graça, A. M., Marôco, J., & Rico, R. (2020). Team adaptability and task cohesion as resources to the non-linear dynamics of workload and sickness absenteeism in firefighter teams. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(4), 525–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1691646

- McDaniel, B. T., O’Connor, K., & Drouin, M. (2021). Work-related technoference at home and feelings of work spillover, overload, life satisfaction and job satisfaction. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 14(5), 526–541. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-11-2020-0197

- Mitchell, T. R., Holtom, B. C., Lee, T. W., Sablynski, C. J., & Erez, M. (2001). Why people stay: Using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 44(6), 1102–1121. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069391

- Mizani, H., Cahyadi, A., Hendryadi, H., Salamah, S., & Retno Sari, S. (2022). Loneliness, student engagement, and academic achievement during emergency remote teaching during COVID-19: The role of the god locus of control. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 305. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01328-9

- Moran, A., & Mallman, M. (2019). Social cohesion in rural Australia: Framework for conformity or social justice? Australian Journal of Social Issues, 54(2), 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.65

- Morrison, R. L. (2008). Negative relationships in the workplace: Associations with organisational commitment, cohesion, job satisfaction and intention to turnover. Journal of Management & Organization, 14(4), 330–344. https://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.837.14.4.330

- Morrison, E. W., See, K. E., & Pan, C. (2015). An approach-inhibition model of employee silence: The joint effects of personal sense of power and target openness. Personnel Psychology, 68(3), 547–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12087

- Myers, S. A., Goldman, Z. W., Atkinson, J., Ball, H., Carton, S. T., Tindage, M. F., & Anderson, A. O. (2016). Student civility in the college classroom: Exploring Student use and effects of classroom citizenship behavior. Communication Education, 65(1), 64–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2015.1061197

- Odden, C. M., & Sias, P. M. (1997). Peer communication relationships and psychological climate. Communication Quarterly, 45(3), 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463379709370058

- Osatuke, K., Moore, S. C., Ward, C., Dyrenforth, S. R., & Belton, L. (2009). Civility, respect, engagement in the workforce (CREW). The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 45(3), 384–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886309335067

- Pacewicz, C. E., Smith, A. L., & Raedeke, T. D. (2020). Group cohesion and relatedness as predictors of self-determined motivation and burnout in adolescent female athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 50, 101709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101709

- Pearson, C. M., Andersson, L. M., & Porath, C. L. (2000). Assessing and attacking workplace incivility. Organizational Dynamics, 29(2), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0090-2616(00)00019-x

- Pearson, C. M., & Porath, C. L. (2005). On the nature, consequences and remedies of workplace incivility: No time for “nice”? Think again. Academy of Management Perspectives, 19(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2005.15841946

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social Science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Porath, C. L., & Pearson, C. M. (2010). The cost of bad behavior. Organizational Dynamics, 39(1), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2009.10.006

- Poulose, S., & Dhal, M. (2020). Role of perceived work–life balance between work overload and career commitment. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 35(3), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-03-2018-0117

- Price, H. E., & Collett, J. L. (2012). The role of exchange and emotion on commitment: A study of teachers. Social Science Research, 41(6), 1469–1479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.05.016

- Rahim, A., & Cosby, D. (2016). A model of workplace incivility, job burnout, turnover intentions, and job performance. Journal of Management Development, 35(10), 1255–1265. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-09-2015-0138

- Rego, A., & Simpson, A. V. (2018). The perceived impact of leaders’ humility on team effectiveness: An empirical study. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(1), 205–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-3008-3

- Ruiz‐Palomino, P., Linuesa‐Langreo, J., & Elche, D. (2021). Team‐level servant leadership and team performance: The mediating roles of organizational citizenship behavior and internal social capital. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility, 30(S2), 127–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12390

- Sawada, U., Shimazu, A., Kawakami, N., Miyamoto, Y., Speigel, L., & Leiter, M. P. (2021). The effects of the civility, respect, and engagement in the workplace (CREW) program on social climate and work engagement in a psychiatric ward in Japan: A Pilot study. Nursing Reports, 11(2), 320–330. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep11020031

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2005). The conceptualization and measurement of burnout: Common ground and worlds apart the views expressed in work & stress commentaries are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily represent those of any other person or organization, or of the journal. Work & Stress, 19(3), 256–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370500385913

- Thompson, M. J., Carlson, D. S., & Hoobler, J. M. (2017). Spillover and crossover of workplace aggression. In M. S. Hershcovis & N. A. Bowling (Eds.), Research and theory on Workplace Aggression (pp. 186–220). Cambridge University Press.

- Tricahyadinata, I., Suryani, H., Zainurossalamia, Z. A. S., & Riadi, S. S. (2020). Workplace incivility, work engagement, and turnover intentions: Multi-group analysis. Cogent Psychology, 7(1), 1743627. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2020.1743627

- Walsh, B. M., Magley, V. J., Reeves, D. W., Davies-Schrils, K. A., Marmet, M. D., & Gallus, J. A. (2012). Assessing workgroup norms for civility: The Development of the civility norms questionnaire-brief. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27(4), 407–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9251-4

- Wang, T., Wang, D., & Liu, Z. (2021). Feedback-seeking from team members increases employee creativity: The roles of thriving at work and mindfulness. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 39(4), 1321–1340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-021-09768-8

- Zabrodska, K., Mudrák, J., Šolcová, I., Květon, P., Blatný, M., & Machovcová, K. (2018). Burnout among university faculty: The central role of work–family conflict. Educational Psychology, 38(6), 800–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2017.1340590