Abstract

This paper examined the mediating role of emotional intelligence in the relationship between psychological empowerment and job performance. The quantitative approach was employed using a survey research design with a sample of 289 respondents from the star-rated hotels in the Central Region, Ghana. The explanatory research design was adopted to explain the relationships among psychological empowerment, emotional intelligence and job performance through the testing of hypotheses. PLS-SEM was used to test these hypotheses. It was found that psychological empowerment had a positive significant relationship with job performance in star-rated hotels. Furthermore, psychological empowerment had a positive relationship with emotional intelligence. Also, emotional intelligence had a positive significant relationship with job performance. Additionally, it was identified that emotional intelligence partially mediates the relationship between psychological empowerment and job performance. From the results, management of star-rated hotels should pay critical attention to employees’ psychological empowerment as a job resource since it improves emotional intelligence and enhance job performance.

1. Introduction

Globally, the travel and tourism sector contributes significantly to the achievement of the sustainable development goals, specifically, SDG#1, 2 and 8. In a fast-developing continent like Africa, the travel, tourism, and hospitality sector has become a major sector that employed approximately 24.7 million people and contributed about USD 169 billion to the continent’s GDP in 2019 (World Travel and Tourism Council, Citation2021). Specifically, in Ghana, the hospitality sector generated around 525,374 jobs as of 2021. The hotel industry in Ghana is made up of budget and star-rated hotels, totalling over 4,000 (Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture, Citation2019).

The star-rated hotels with its wide variety of packages, space, facilities, and workers are usually preferred by most tourists and visitors. Among the 16 regions in Ghana, the Central Region holds four of the Worlds Heritage Monuments sites in the country (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation [UNESCO]), which attracts a greater number of tourists to the region. However, most of these tourists and visitors prefer to lodge in Accra or Takoradi even though the Region has over 197 star-rated hotels (Anaman & Dacosta, Citation2017; Ghana Hotels Association [GHA], Citation2022). This has been attributed to poor job performance behaviours of the hotel workers (International Labour Organisation [ILO], Citation2020). These behaviours of the workers manifest in slow response to reservations, lack of cooperation and flexibility, insubordination, inappropriate work methods and unwillingness to take responsibility coupled with lower friendliness among workers and managers (International Labour Organisation, Citation2020; Amankwah-Amoah et al., Citation2017; Anaman & Dacosta, Citation2017). These poor job performance behaviours have resulted in customer dissatisfaction, loss of clients, poor patronage and loss of business investment capital.

In view of this, several interventions have been taken by industry partners in the form of rewards, pieces of training, capacity building, and development. Despite all these efforts, the problem still exists. In stimulating hotel workers’ performance in this Region, psychological empowerment and emotional intelligence (EI) of workers are sensitive antecedents for consideration (Francis & Alagas, Citation2020) as supported by the job demands-resources theory. Psychological empowerment and emotional intelligence are job and personal resources that can help employees in managing job demands such as job performance and promote positive job outcomes by motivating employees.

Literature reveals that psychological empowerment has gained the attention of many scholars in their quest to alienate poor job performance behaviours among workers in Western nationals (Commey et al., Citation2016; Li et al., Citation2018; Ölçer & Florescu, Citation2015; Shi et al., Citation2022; Tuuli & Rowlinson, Citation2009). However, in the context of developing nations, there is scanty literature on psychological empowerment and job performance in the hotel industry, especially in the Central region of Ghana (Francis & Alagas, Citation2020). Furthermore, studies have not focused on regressing psychological empowerment on employee job performance with recourse to how emotional intelligence could impact the relationship. In addition, most of these studies employed only task and contextual performance in the operationalisation of job performance without looking at the adaptive performance aspect of job performance (Yao et al., Citation2020). On this premise, the foci of this paper were to examine the relationship between psychological empowerment and job performance as well as the mediating role of emotional intelligence in the relationship between psychological empowerment and job performance in the star-rated hotels in the Central Region-Ghana.

The rest of the paper looks at the literature review, research methods and model. These are followed by the analysis of hypotheses, findings, discussions, and conclusions. Lastly, the implications of the study and suggestions for future studies were presented.

2. Literature review

2.1. Job demands-resources theory (JD-R)

The job demands-resources theory (JD-R) is an organisational theory propounded after the publication by Demerouti et al. (Citation2001). The JD-R theory which is an extension of the job demands-resources model, is a theoretical framework that explains how job demands and resources can affect employees’ well-being and job performance. According to the theory, there are two types of environments in every workplace, which are the demands required by the job (job demands) and the resources (job resources) available or needed to meet those demands (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007, Citation2017). The recent extension included in the theory is personal resources (Xanthopoulou et al., Citation2007;Citation2009). This is known as the person’s sense of self-efficacy and optimism with their ability to influence their work environment (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017).

The job demands encompass all the physiological, social, and emotional pressures associated with one’s work and require a persistent effort and a corresponding psychological cost (Demerouti et al., Citation2001). Included in the job demands are a hefty workload, conflicting demands from managers and clients, a stressful work environment, emotional labour, poor relationships, and uncertainty in the role. On the contrary, job resources are the physical, psychological, social, and organisational dynamics that help individuals perform well and reduce negative work outcomes (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017; Demerouti et al., Citation2001). Autonomy, self-efficacy, the opportunity for advancement, coaching, learning, and development are all considered resources. According to the theory when job resources are high and job demands are low, it improves motivation, upsurges performance, and other positive job outcomes.

Additionally, the theory explains how job demands and resources have multiple effects on motivation and stress (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2014). Khan et al. (Citation2020) indicated that empowered staff are more sensitive to client needs and deal with consumers more cordially, leading to increased performance. According to this notion, job demands, as well as job and personal resources, activate different processes. Job resources result in a motivational process; therefore, possessing those leads to better job performance. Similarly, in this current study, it was suggested that psychological empowerment is a job and personal resource. Moreover, per the job demands-resources theory, employees use their resources to meet the job demands (Bakker & de Vries, Citation2021).

For example, having autonomy in one’s work, which is the same as the self-determination dimension of psychological empowerment, can suppport an employee in dealing with a heavy workload. On the other hand, when high, job demands cause job strain, which harms job performance (Tummers & Bakker, Citation2021). Additionally, the JD-R theory is a two-pronged paradigm, with one focusing on health impairment and the other on motivation. According to the health impairment process, high employment demands lead to burnout and health concerns (e.g., exhaustion, sleep disturbances, and cardiac dangers). Employees who are subjected to high emotional demands, excessive work overload, or workplace emotional discord, for example, have been reported to experience exhaustion (Bakker & de Vries, Citation2021; Bakker et al., Citation2003).

Alternatively, job resources lead to good job outcomes such as employee commitment, employee performance, and intention to stay, in the motivational process (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007). This is because embedded in job resources are both intrinsic and extrinsic stimulus on performance since it supports employee knowledge acquisition, development, and evolution (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007). Also, job resources intrinsically motivate and enhance job performance (Lupsa et al., Citation2019). It assists in fulfilling fundamental human needs including competence and relatedness (Bakker & de Vries, Citation2021).

Psychological empowerment is a four-dimensional variable, which is defined as the extent to which employees feel competent, find their work meaningful, and are determined in their work, and is considered a critical job resource (Spreitzer, Citation1995). Empowered employees are more likely to feel engaged, motivated, and committed to their work, which can lead to higher job performance (Afsar & Badir, Citation2016). Psychological empowerment was recognised by Ugwu et al. (Citation2014) as a resource, while Schaufeli and Taris (Citation2014) identified risk-taking and performance as job demands. Also, Ugwu et al. (Citation2014) indicated that psychological empowerment is a resource that retains personnel on track to complete their tasks. The Job Demands-Resources theory explains the interaction between job demands and job resources as well as their influence on job outcomes (Iqbal et al., Citation2020; Kirrane et al., Citation2018).

This study is peripheral to the JD-R theory and on the premise that job performance constitutes a job demand which can be better dealt with by psychological empowerment serving as a job resource to improve the well-being of employees and promotes positive job outcomes. The JD-R model (Demerouti et al., Citation2001; Seibert et al., Citation2011) reveals that employees can use psychological empowerment as a resource on the job to stimulate job performance. Lupsa et al. (Citation2019) highlight that when employees have access to and increase these resources, it enhances job performance and improves their well-being. Furthermore, The JD-R theory suggests that job resources, such as psychological empowerment, can buffer the negative effects of job demands on employees’ well-being and job performance. This means that even when employees face high job demands, having access to job resources like psychological empowerment can help them cope and perform better (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017).

In the context of emotional intelligence, job demands such as emotional labour or stress can deplete an employee’s emotional resources, while emotional intelligence can act as a job resource to help employees effectively manage these demands (Bakker & De Vries, Citation2021). For example, employees high in emotional intelligence may be better equipped to manage the emotional demands of a customer service role, leading to reduced burnout and turnover (Bakker & De Vries, Citation2021). This highlights the importance of emotional intelligence as a job resource in managing job demands and promoting positive job outcomes.

Emotional intelligence refers to the ability to recognize and understand one’s emotions, as well as the emotions of others, and use that information to guide thinking and behaviour. According to a study by Sanchez-Gomez and Breso (Citation2020), employees who possess high levels of EI are better able to cope with job demands and are more likely to experience positive job outcomes, such as job satisfaction and performance. Employees who possess high levels of EI may be better able to leverage the resources provided by psychological empowerment to enhance their job performance.

This study broadens the theoretical perspective of job demands-resources theory by looking at how psychological empowerment and emotional intelligence might be used to deal with workplace demands such as job performance. Figure depicts the hypotheses that were examined in this study.

3. Conceptual review

3.1. Psychological empowerment

Conger and Kanungo (Citation1988) defined psychological empowerment as a process that fires emotions of self-efficacy among employees by removing all variables that promote powerlessness through formal organisational procedures and informal means of providing useful knowledge. It stimulates and induces employees’ enthusiasm to work and promotes job performance (Meng & Sun, Citation2019) through meaningful work, self-determination, and the impact of the employees as well as their competence.

Meaning produces an emotional response to the relevance and significance of work to the individual. The self-determination dimension of psychological empowerment implies some control over employees’ work habits and procedures (Bell & Staw, Citation1989). Increased flexibility, inventiveness, initiative, resilience, and self—control result from the self—determination of employees (Thomas & Velthouse, Citation1990). Competence is seen as self-efficacy, an individual’s confidence and belief in one’s ability to execute well within their domain of skill. Bandura (Citation1977) compares competence to personal mastery or effort—performance expectancy. The impact of employees is described as the extent to which an individual’s behaviour or job brings a difference in the workplace. Impact refers to an employee’s ability to influence strategic, administrative (Ashforth, Citation1989), and work results for the organisation (Spreitzer, Citation1995), as well as persuade others to assent to their ideas (Quinn & Spreitzer, Citation1997). Despite their differences, all of these elements contribute to the overall concept of psychological empowerment (Spreitzer, Citation1995).

4. Emotional intelligence

Wong and Law (Citation2002) established the WLEIS scale, which is linked to the four measures of emotional intelligence: Self-Emotion Appraisal, Others’ Emotion Appraisal, Use of Emotion and Regulation of Emotion. A self-emotion appraisal is an ability to be familiar with and express one’s profound emotions. The ability to detect and comprehend others’ emotions is referred to as others’ emotion appraisal. Regulation of emotion is explained as a person’s capability to control their emotions, which allows them to recover from psychological pain more quickly. The use of emotion gauges a person’s capacity to direct their emotions toward useful endeavours and superior achievement (Hur et al., Citation2011; Yan et al., Citation2018).

5. Job performance

Borman and Motowidlo (Citation1997) classified individual performance into two categories: task performance and contextual performance. Adaptive performance has been included as a distinct domain in job performance evaluation by Sinclair and Tucker (Citation2006) and Haneberg (Citation2011) in response to recent environmental dynamics. Overall, job performance is described as the behaviour of an individual employee that is relevant to the organisation’s aim. Job performance is determined by the behaviours and actions of the employees (Campbell & Wiernik, Citation2015).

Task performance is characterised as an employee’s conduct consistent with the requirements of their job description. It is seen as behaviours that aid in the creation of a product or the delivery of services. It contains work-related behaviours that are largely role-specific and are typically stated in job descriptions (Borman & Motowidlo, Citation1997). As a result, the universal frameworks for task performance are difficult to obtain because they are related to fundamental job functions, and perspective frameworks are used.

Contextual performance is viewed as the behaviour which supports the ideal corporate, social, and psychological surroundings and is consistent with the organisation’s goal, it is known as organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB). It is also described as the conduct that assists the organisation in achieving its objectives by enhancing the social and psychological environment (Rotundo & Sackett, Citation2002). It includes activities that go above and beyond what is required for a job, like initiative, proactivity, teamwork, and enthusiasm (Koopmans et al., Citation2011). Adaptive performance is concerned with interdependent development, work system uncertainty, and continual changes in the workplace.

6. Psychological empowerment and job performance

Since the term’s inception, scholars have emphasised the link between psychological empowerment and job performance (Figure ), because psychological empowerment’s ultimate goal is to improve workplace performance. Empowerment should not only been captured as a phenomenon that lies on managers to execute to their employees but instead, it should focus on the psychological perspective that produces intrinsic motivation and helps employees to perform better.

Ölçer and Florescu (Citation2015) conducted a study to assess the mediating role of job satisfaction in the relationship between the aspects of psychological empowerment-meaning, competence, self-determination, and impact-and job performance in the manufacturing sector. It was discovered that the psychological empowerment characteristics, competence, self-determination, and impact improved job performance, whereas meaning had no link to job performance. Again, Al-Makhadmah et al. (Citation2020) researched psychological empowerment and employee performance in four and five-star hotels in the Dead Sea- Jordon tourist Area. In their study, it was revealed that the performance of employees was influenced by meaning and self-determination dimensions of psychological empowerment, while competence and impact of employees did not affect job performance. Also, the educational level of the employees significantly moderated the relationship between impact and employee performance but did not affect the meaning, competence, and self-determination.

Research on the effect of psychological empowerment on job performance is still in its early stages. For instance, Spreitzer’s four-dimensional psychological empowerment measure was utilised by Liden et al. (Citation2000) to examine how it affects job performance. They discovered that psychological empowerment had a significant positive effect on job performance. According to Dewettinck et al. (Citation2003), psychological empowerment has no seeming effect on job performance, although it can boost employee job satisfaction and commmitment. In the study by Pepra-Mensah et al. (Citation2015) among hotel employees in Cape Coast and Elmina in the Central Region of Ghana on the effect of work attitudes on turnover intentions, it was found that satisfaction, motivation, and alternative job opportunities had a significant relationship with intention to quit. Albeit, organisational commitment and job hopping were not significant to the intention to quit. Instead, they concluded that the management of hotel businesses must consider proper compensation and motivational strategies to retain employees to enhance job performance. This raises a key question that needs careful attention in the current literature; what motivational strategies should hotel managers adopt to retain employees and improve job performance?

Psychological empowerment is the process that ignites self-efficacy among employees. It is a form of intrinsic motivation that makes employees feel they have work-related abilities and control over their decision. Most of the studies (Amankwah et al., Citation2020) focused on the theorised motivational packages, rewards as well as training and how they influence the performance of employees. It was identified that studies on psychological empowerment as a motivational strategy is scanty, especially in Ghana. Therefore, it was hypothesised that,

H1:

There is a significant positive relationship between psychological empowerment and job performance of workers in star-rated hotels.

7. Psychological empowerment and emotional intelligence

Conger and Kanungo (Citation1988) defined psychological empowerment as a process that fires emotions of self-efficacy among employees by removing all variables that promote powerlessness through formal organisational procedures and informal means of providing useful knowledge. Thomas and Velthouse (Citation1990) expanded on this premise, stating that a broad collection of activities, including meaningfulness, choice, competence, and impact of employees, might inherently inspire people. Despite their differences, all of these elements contribute to the overall concept of psychological empowerment (Spreitzer, Citation1995).

Meaning produces an emotional response to the relevance and significance of work to the individual. Meaning is the importance of the work objectives to one’s ideals and the assessment of a task’s goal (Spreitzer, Citation1995). The self-determination dimension of psychological empowerment implies some control over employees’ work habits and procedures (Bell & Staw, Citation1989). The impact of employees is described as the extent to which an individual’s behaviour or job brings a difference in the workplace. Impact refers to an employee’s ability to influence strategic, administrative (Ashforth, Citation1989), and work results for the organisation (Thomas & Velthouse, Citation1990), as well as persuade others to buy into their ideas (Spreitzer, Citation1995).

Emotional intelligence according to the definition is described as a concept with four dimensions; the capacity for emotion management, sensation, and expression of emotions as well as the understanding and use of emotions as a tool for thought (Goleman, Citation1995). Emotionally intelligent employees may be more conscious of their own and others’ emotions. As a result of their great emotional intelligence, people may be able to perform well (Kamassi et al., Citation2019). In addition, employees must be able to grasp customers’ perspectives and form relationships with them to support possible transactions, most notably in the service organisations like the hotel industry.

Wong and Law (Citation2002) established the WLEIS scale, which is linked to the four measures of emotional intelligence: Self-Emotion Appraisal, Others’ Emotion Appraisal, Use of Emotion and Regulation of Emotion. A self-emotion appraisal is an ability to be familiar with and express one’s profound emotions. The ability to detect and comprehend others’ emotions is called others’ emotion appraisal. Finally, emotion regulation is explained as a person’s ability to control their emotions, allowing them to recover from psychological pain more quickly. Taking into consideration these measures, psychological empowerment may enhance the emotional intelligence of employee through incresase self-awareness, social awareness and adaptability.

In this light, psychological empowerment dimensions, including meaningful work, competence, impact and self-determination, may influence employees’ emotional intelligence (see ). Thus, when empoloyees are empowered, they are likely to engage in work bahaviours and practices that promote emotional intelligence. For instance, the meaningful work dimension of psychological empowerment can boost employees’ emotional intelligence. Emotional intelligence, unlike intelligence quotient, can be learnt over time on the job. As employees find meaningfulness in their work, they become attached to it and develop the essential skills to perform their work quickly and efficiently. The hotel work environment requires employees to be emotionally intelligent and employees who find their work meaningful are psychologically empowered, and their emotional intelligence may be enhanced. Employees who possess high levels of EI may be better able to leverage the resources provided by psychological empowerment. Thus, it was hypothesised that:

H2:

There is a significant positive relationship between psychological empowerment and emotional intelligence of workers in star-rated hotels.

8. Emotional intelligence and job performance

Emotional Intelligence (EI) theory, explains emotional intelligence as a set of interconnected social and emotional competencies that connote how well people comprehend and communicate, understand and relate to others, and manage the pressures of everyday life. Countless interaction with clients from diverse backgrounds and high demands on employees from both customers and managers (Brunetto et al., Citation2012; Siaw et al., Citation2018) requires that employees are emotionally intelligent to communicate effectively and control their emotions.

In other words, whether employee’s conduct reflects the organisation’s objectives depends on its ability to produce the intended outcomes. One of the categories of performance, job performance, indicates whether the work done by the employees is effective or whether they can demonstrate good talent, which represents how well a person is exploiting opportunities (Gong et al., Citation2019). In a study by Chong, Falahat and Lee (Citation2020), it was found that emotional intelligence dimensions (intrapersonal skills, interpersonal skills, adaptability and general mood) have a significant positive relationship with job performance.

An individual who can thrive in the hotel industry or the hospitality profession, and coordinate closely with customers and managers, must be someone with sufficient emotional intelligence to recognise and take advantage of their sentiments and thoughts. In their study, Zhang and Fan (Citation2013) discovered that emotional intelligence has a positive significant relationship with project performance. Their study also revealed that international involvement and contract type moderate the relationship between emotional intelligence and project performance. Another study by Alonazi (Citation2020) on the effect of emotional intelligence and job performance during the COVID-19 pandemic found that emotional intelligence had a significant relationship with job performance. Similarly, Asiamah (Citation2017) studied the relationship between emotional intelligence and job performance among health workers. It was discovered that emotional intelligence had a significant positive effect on job performance. Also, it was concluded that employees’ emotional intelligence helps them to perform their job roles and thus when improved, employees will increase their job performance (Asiamah, Citation2017). In response, it was hypothesised in this study that;

H3:

There is a significant positive relationship between emotional intelligence and job performance of employees in the hotel industry in the Central region.

9. Psychological empowerment, emotional intelligence and job performance

Scholars have found relationships between psychological empowerment and emotional intelligence. Several studies on emotional intelligence, such as (Bar-On, Citation1997; Bar-On & Parker, Citation2000; Langhorn, Citation2004; Goleman, Citation1995), concluded that emotional intelligence and job performance are positively correlated. According to a meta-analysis, employees having high emotional intelligence outperformed those with low emotional intelligence (O’Boyle et al., Citation2011). Similarly, Jung and Yoon (Citation2012) discovered that among food and beverage (F&B) personnel in a luxury hotel, there is a direct negative relationship between emotional intelligence and counter productive work behaviours.

According to Idrus et al. (Citation2015), psychological empowerment influences employees’ emotional intelligence. Also, Francis et al. (Citation2018), studied the causal relationship between employees’ emotional intelligence, organisational support, organisational citizenship behaviour, and job performance. They found that emotional intelligence and psychological empowerment positively impact job performance. Furthermore, Lipson (Citation2020) conducted a study to determine the role of emotional intelligence in the relationship between job resources and employee work engagement, and it was discovered that emotional intelligence did not affect the relationship between supervisor support, autonomy and employee engagement. Emotional intelligence may be crucial when working in the service sector and other businesses where employees must interact with customers (Karimi et al., Citation2021). Emotional intelligence (EI) is the capacity to identify, comprehend, and use one’s own and others’ emotions to inform one’s own and others’ actions. According to a study by , employees who have high levels of EI are better equipped to handle job demands and are more likely to have favourable employment outcomes, such as job satisfaction and performance. High EI employees may be more adept at utilising the tools offered by psychological empowerment to improve their work output. Moreover,employees who feel psychologically empowered are more motivated in their job roles which can enable them to effectively understand and manage their emotions to maintain a positive attitude and build better interpersonal relationships in the workplace. This emotional intelligence, in turn, positively affects job performance (Figure ). As a result, it was hypothesised that;

H4:

Emotional intelligence mediates the relationship between psychological empowerment and job performance.

10. Summary of literature review

10.1. Psychological empowerment, emotional intelligence and job performance

11. Methodology

11.1. Research methods

This research employed the quantitative research approach. The fundamental research design is survey design. This permitted testing hypotheses and administering the same set of questions to respondents. The quantitative approach allowed for the use of quantitative tools such as inferential and descriptive statistics to describe issues in this study (Hoover & Donovan, Citation2008). Also, validity and reliability were all tested in this study as they are vital to this study.

12. Survey instrument

The instrument employed for gathering data for the study was a structured questionnaire. The questionnaire contained closed-ended items which were self-administered. After developing the instruments, reliability and validity were tested through the use of Cronbach Alpha, and peer and expert review. Prior to the distribution to the employees in the star-rated hotels in the region, the instrument was pre-tested and revised based on experts’ opinions. All items were rated on a 5-Point Likert-like scale with “1-least agreement to 5-highest agreement.”

The survey questionnaire (see Appendix B) contained four sections. Section A gathered information on the demographics of the respondents (see Appendix A). Section B collected information on workers psychological empowerment using the Psychological Empowerment Scale (PES) given by Spreitzer (Citation1995) was adapted and was supported with items from Singh and Sarkar (Citation2018). Each sub-dimension had five items making a total of 20 items. Section C comprised question items on emotional intelligence. The Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS), established by Wong and Law (Citation2002), was used. This scale had a total of 16 items with 4 items for each subscale. And Section D was on job performance of the employees. It was measured by “The Individual Work Performance Questionnaire” (IWPQ) by Koopmans et al. (Citation2015) for the task and contextual performance. Individual Adaptive performance measure given by Marques-Quinteiro et al. (Citation2015) was used to measure Adaptive Performance.

13. Data collection

The respondents for this study were employees in star-rated hotels in the Central Region. The probability sampling technique known as simple random sampling was used in this study. The lottery method of simple random sampling technique was used. This technique gives every employee in the target population an equal chance of participating in the study, thus ensuring that biases associated with data collection were minimised. This technique was used because all the employees in the star-rated hotels were considered a homogenous group with similar characteristics. All the respondents in the various hotels were assigned numbers to represent them on paper cards. These papers were folded and placed into a container, afterwards, these paper cards were blindly selected until the sample size was obtained. Table represents the sample frame for the employees of star-rated hotels in the Central Region and the proportion of the sample.

Table 1. Sample frame of respondents

14. Sample size

A sample size of 289 hotel employees was generated using Krejcie and Morgan sample size determination table (Krejcie & Morgan, Citation1970). The distribution of the sample size among the hotels were done using proportions (see Table ). Simple randomly sampling was used through the lottery method (Rahman et al., Citation2022). Ethical issues such as voluntary participation, anonymity and informed consent were adhered to in this study.

15. Area of study

The area of study was the Central Region of Ghana. The area was selected for the study because of its numerous contributions to tourism and ecotourism in Ghana. The region’s capital, Cape Coast was Ghana’s first Capital of Ghana. Tourism, particularly high-end leisure and ecotourism, is already significantly influencing jobs and community income in the Cape Coast, Elmina, and other districts along the region. The target population were employees working in star-rated hotels in the Central Region at the time of the survey. Information from the Office of the Ghana Tourism Authority in Cape Coast indicated that the total number of employees of the star-rated (3-star, 2-star and 1-star) hotels in the Central Region was 1,145 employees as of 2022.

16. Measurement of variables

16.1. Psychological empowerment

In measuring psychological empowerment, four measures were utilised: meaningful work, competence of employees, self-determination and impact of employees (Spreitzer, Citation1995).

16.2. Emotional intelligence

In this study, Emotional Intelligence had four measurements from Wong and Law (Citation2002) which are: self-emotion appraisal, others’ emotion appraisal, use of emotion, and regulation of emotion.

16.3. Job performance

The measuring components of job performance were Task performance, Contextual performance (Koopmans et al., 2014) and Adaptive performance (Marques-Quinteiro et al., Citation2015).

17. Data analysis

The structural equation modelling partial least square using the SmartPLS 3.0 was utilised to test the measurement model and hypotheses, it was used to calculate the path coefficient (β), coefficient of determination (R2), effect size (f2), and predictive relevance (Q2) to assess the predictive capability of the structural model (Ringle, Sarstedt & Schlittgen, Citation2014). Structural equation modelling has been an appropriate analysis procedure for testing mediation effects. According to Alwin and Hauser (Citation1975) and Bollen (Citation1987), the mediation effect in SEM can be described as an indirect effect, such that “the indirect effect of an independent variable (X) on a dependent variable (Y) via a mediator (M)” in which X influences M, which then influences Hair et al. (Citation2021) defined that mediation happens once a mediator construct regulates the dependent and independent variables. Thus, a change in the exogenous variable causes a change in the mediator construct, resulting in a change in the endogenous construct (see Figure ). It is represented by the direct and indirect effects. The causal connection between dependent and independent variables is known as a direct effect.

A structural path is considered to have indirect effects when it involves some interactions with at least one intervening construct. As a result, an indirect influence is a chain of two or more direct effects and is visually represented by many connections (Hair et al., Citation2021; Nitzl et al., Citation2017). Thorough research of mediation is based on relationships that have been theorised and hypothesised, such as the mediating effect on a model that is theoretically supported. There are three possible outcomes of the mediation process: complementary mediation, competitive mediation, and indirect-only mediation (Hair et al., Citation2021; Nitzl et al., Citation2017). Complementary mediation takes place when both the direct and indirect effects are significant and point in the same direction. This is known to be partial (complementary) mediation.

When the direct and indirect effects are both significant but in the opposite direction, a competitive partial mediation-also known as competing mediation occurs. Additionally, when only the indirect effect is significant, there is an indirect only mediation, thus the full mediation (Baron & Kenny, Citation1986; Hair et al., Citation2021). Emotional intelligence’s potential to play a role between psychological empowerment and job performance was examined in this current study.

18. Results

18.1. Preliminary assessment

This section presents the assessment of the PLS-SEM measurement. Assessing the measurement model includes the reliability of the indicators, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity. The model measurement assessment is evaluated using the factor loadings (see ), the RhoA and composite reliability were used to assess the internal consistency reliability. Also, the convergent validity was evaluated using Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and the discriminant validity, using the Fornell-Larcker Criterion and HTMT. The values for RhoA, Composite reliability and AVE are shown in . The values of RhoA and Composite reliability must load more than 0.7, the AVE values must be above 0,50 (Hair et al., Citation2021). The HTMT values for discriminant validity is depicted in Table . Even though the Fornell-Larcker criterion for discriminant validity was achieved in this study, Henseler et al. (Citation2015) suggest evaluating the correlations’ heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) is more appropriate in establishing the discriminant validity to address the shortcomings in the Fornell-Larcker criterion’s inability to reliably identify the discriminant validity. Also, the demographic characteristics of respondents are shown in Appendix A.

Table 2. Factor loadings

Table 3. Internal consistency and discriminant validity

Table 4. Heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) values

19. Factor loadings

According to Awang (Citation2014), a valid indicator must load 0.60 and above. For that reason, all indicators that loaded below the threshold of 0.6 were removed to meet the requirement and enhance the reliability of the measurement model. A total of 51 indicators were used to measure all the latent variables in the study. Table presents the indicator loadings for the latent variables. Psychological empowerment measurement items (MW1, MW3, MW4, MW5, IM1-IM5, CM1, CM2, and SD2-SD5) were deleted. Emotional intelligence items (SEA1, SEA3, SEA4, and OEA1-OEA3) were also deleted. Additionally, (AP1, CP1-CP5, TP1, and TP4) were deleted to improve the model’s reliability.

Table shows that some indicators have been deleted; all indicators loaded below 0.6 as prescribed by Awang (Citation2014), were removed from the model to increase reliability. In addition, all indicators loaded below the threshold were deleted given that they fell short of the requirement as Awang (Citation2014) prescribed. Thus, they are not a true measure of their construct in this study.

20. Reliability test

According to Hair et al. (Citation2021), values ranging between 0.70 and 0.90 thresholds represent a satisfactory to a good level of reliability. The coefficient RhoA and the composite reliability were used for the internal consistency reliability because of the deficiencies with the Cronbach Alpha. The Cronbach Alpha has a limitation of tau-equivalence (It is more conservative and assumes all the population has the same indicator loadings) (Dijkstra & Henseler, Citation2015). From Table , using the coefficient RhoA and the composite reliability, all the loadings were above 0.7, showing greater reliability of the variables (Hair et al., Citation2021).

21. Validity test

The Validity test has two main tests: convergent validity and divergent validity. Convergent validity measures the degree to which the indicators converge to explain the latent variables’ variance, thus the degree by which a given measure is positively correlated with other measurements of the same construct (Hair et al., Citation2021). The average variance extracted (AVE) was employed. A construct is said to explain at least 50% of the variance of its indicators when the AVE value is 0.50 or higher (Hair et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, an AVE of less than 0.50 denotes that, on average, more variance is still present in the item errors than in the variance explained by the construct. From Table , the findings show that each construct has an AVE of more than 0.50.

22. Discriminant validity

The degree to which the constructs in the structural model are distinct from one another is measured by discriminant validity. For discriminant validity, a construct must be distinct and capture phenomena not captured by other constructs in the model (MacKinnon, Citation2008). The heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) was employed in this study to establish discriminant validity.

Due to flaws in the Fornell-Larcker Criteria, the HTMT has been approved and is more appropriate. As a result, the HTMT was analysed, see Table . Henseler et al. (Citation2015) suggest evaluating the correlations’ heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) is more appropriate in establishing the discriminant validity to address the shortcomings in the Fornell-Larcker criterion’s inability to identify the discriminant validity reliably. The indicator correlations’ average value across the construct is known as HTMT. A latent construct possesses discriminant validity, when the HTMT value is less than 0.850 (Henseler et al., Citation2015). From Table , discriminant validity was achieved.

23. Assessing multicollinearity

Collinearity occurs when the predictor indicators in the model are highly correlated (Hair et al., Citation2021). The metric for assessing the collinearity of indicators in this study is the Variance Inflator Factor (VIF). In PLS-SEM, a VIF score of 0.2 or lower and a score of 5 or higher indicates a problem of collinearity among the construct. The results for multicollinearity among independent variables are presented in Table .

Table 5. Collinearity among variables

The collinearity results from Table indicate that the independent variables have no issues with multicollinearity because they all meet the threshold. A common method bias is not present, according to the VIF data in Table . According to the standards outlined by Kock and Lynn (Citation2012), a VIF score of more than 3.3 indicates pathological collinearity and a cautionary indicator that the model may be vulnerable to common method bias. The model can be said to be free from the issue of vertical or lateral collinearity as well as common method bias if all of the VIFs from a full collinearity test are equal to or lower than 3.3 (Kock, Citation2017).

24. Assessing the coefficient of determination and the predictive relevance

The model’s explanatory power in terms of the endogenous component is measured using the coefficient of determination (R2) (Shmueli & Koppius, Citation2011). The R2 values range from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 indicating a better explanatory power. Even though R2 values are acceptable on the bases of the research context, R2 values of 0.25 are considered weak, 0.50 are considered moderate whilst 0.75 are considered substantial in the social sciences field (Hair et al., Citation2011, Citation2021). The author also claimed that for structural models, a predictive relevance (Q2) of “0.02, 0.15, and 0.35” and an effect size (f2) of “0.02, 0.15, and 0.35” are viewed as “small, medium, and large,” respectively.

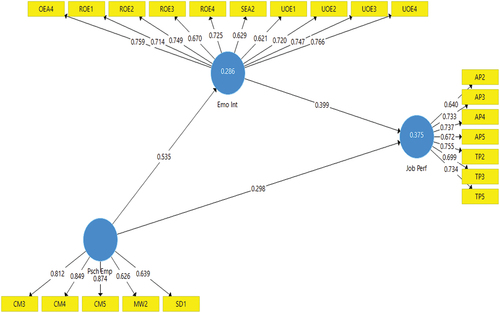

From Table , the model had a moderate explanatory power (0.375). This means that psychological performance and emotional intelligence account for 37.5% of the variations in job performance. Additionally, psychological empowerment enhances emotional intelligence by 28.6%. Therefore, the model results indicate that the model has a moderate predictive significance.

Table 6. Coefficient of determination

25. Structural model

This study aimed to assess the mediating role of emotional intelligence in the relationship between psychological empowerment and job performance among star-rated hotels in the Central Region of Ghana. Information relating to the evaluation of the research hypotheses is provided in this section. This section assesses the relevance and significance of the path coefficients. The bootstrapping method in PLS-SEM was used to test the hypotheses. The regression model was employed to test the hypotheses. All the hypotheses in the study had a significant positive relationship as presented in Figure . With H1 the statistical values are: β = 0.298, t = 4.033, p = 0.000; the values for H2 are: β = 0.535, t = 9.869, p = 0.000; the values for H3 are: β = 0.399, t = 5.818, p = 0.000; and the values for H4 are: β = 0.213, t = 4.930, p = 0.000. The R2 for Job performance is 0.375, and R2 for emotional intelligence is 0.286.

26. Testing the significance of the model

In PLS-SEM, the bootstrapping process is undertaken to assess the significance of the path model. Bootstrapping is a SEM resampling technique to evaluate the path model’s significance. A bootstrap approach is used by creating numerous subsamples from the original sample and estimating parameters for each subsample. At a 5% significance level (two-tailed), any t-value above 1.96 is considered to be statistically significant. The results of the path modelling are depicted in Figure , Table . Concerning the P-values, any value of 0.05 or lower is interpreted as being significant. The next section presents the results of the hypotheses and discussions on the findings.

Table 7. Path coefficients

From Table , the results of the SEM indicate that psychological empowerment had a significant positive relationship with job performance (β = 0.298, p < 0.05, f2=0.102). Also, emotional intelligence had a significant positive relationship with job performance (β = 0.399, p < 0.05, f2=0.182). Psychological empowerment had a significant positive relationship with emotional intelligence (β = 0.535, p < 0.05, f2=0.401).

Table presents the mediating effect of emotional intelligence in the relationship between psychological empowerment and job performance. From Table , emotional intelligence partially mediates the relationship between psychological empowerment and job performance (β = 0.213, t-value >2; p < 0.05).

Table 8. Mediating effect

27. Discussion

The study assessed the role of emotional intelligence in the relationship between psychological empowerment and job performance of star-rated hotels in the Central Region. Specifically, the study examined the relationship between psychological empowerment and job performance. The findings revealed that when employees are psychologically empowered, they perform better. Thus, psychological empowerment significantly impacts employees’ job performance in star-rated hotels in the Central Region. This present study in assertion supports that all dimensions of psychological empowerment are crucial to job performance since it serves as employees’ resource that helps them meet their job demands. Contrary to the findings of Liden et al. (Citation2000), Okyireh and Simpeh (Citation2016); Mahmoud et al. (Citation2021), Dewettinck et al. (Citation2003) who discovered that psychological empowerment could boost employee job satisfaction but has no discernible effect on job performance. This study discovered that, psychological empowerment has a singnificant positive relationship with job performance. This shows that psychological empowerment in the Ghanaian hotel industry is key in stimulating the needed response of employees for job performance.

The findings of this objective also agree with the Job Demands-Resources theory (Demerouti et al., Citation2001), which is based on the notion that there are two types of work environments: job demands and job resources that impact the performance of employees. The job demands encompass all the physical, social and emotional pressures associated with one’s work and require a sustained effort. On the other side, job resources are the physical, psychological, social and organisational dynamics that help individuals perform well and reduce negative work outcomes (Bakker et al., Citation2003).

The four cognitions of competence, impact, self-determination, and meaning were used by (Spreitzer, Citation1995) to define psychological empowerment as a psychological condition. Psychological empowerment constitutes a job resource, that is, employees are more driven to achieve at a high level as a result of empowerment since it increases their intrinsic motivational resources (Arshadi, Citation2010). Consequently, employees tend to perform well as a result of being psychologically empowered. Employees who feel empowered at work perform better because their job is meaningful to them and align with their life goals reflecting a sense of self-control with one’s work and active involvement with one’s work role. This gives them access to essential resources that help them improve themselves in the workplace (Javed et al., Citation2017).

The study also examined the relationship between psychological empowerment and emotional intelligence. It was found that when employees are psychologically empowered, it boosts their emotional intelligence. Employees’ psychological empowerment enhances their emotional intelligence. Both psychological empowerment and emotional intelligence serve as job resources that assist employees to handle their job demands in the workplace.

Based on the study’s findings, it was concluded that there is a significant positive relationship between emotional intelligence and job performance. This implies that higher emotional intelligence leads to higher job performance among employees. The findings are also in line with Asiamah (Citation2017), who concluded that emotional intelligence positively affected job performance. It was asserted that employees’ emotional intelligence helps them perform their job roles and improve job and organisational performance. Similarly, Edward and Purba (Citation2020), found that emotional intelligence had a significant positive relationship with the employee’s performance. The study also examined the mediating role of emotional intelligence in the relationship between psychological empowerment and job performance. It was found that emotional intelligence partially mediates the relationship between psychological empowerment and job performance.

The findings are supported by the results, employees who have high levels of EI are better equipped to handle job demands and are more likely to have favourable employment outcomes, such as job satisfaction and performance. Similar finding is seen in Karimi et al. (Citation2021), emotional intelligence may be crucial when working in the service sector and other businesses where employees must interact with customers. This implies that even though psychological empowerment enhances job performance, it can also boost employees’ emotional intelligence. This will then cause them to perform well and better by maintaining a positive composure while handling their job duties through communication with clients and managers, constructive conflict resolutions and relations with colleagues in the organisation. Employee control over their roles in the workplace and their feelings of capacity to contribute to the organisation are addressed through psychological empowerment (Najafi et al., Citation2011).

28. Conclusion

Policymakers, including the management, industry stakeholders and the ministries, should develop policies that enforce psychological empowerment as a vital job resource that helps employees improve their job performance and the image of the industry. Employees may generate several outcomes according to the extent to which they are psychologically empowered. This will reduce employee turnover and promote the success of the industry. Additionally, it will ensure employees’ efficiency and effectiveness, which manifest in reducing total cost, smooth operations and customer satisfaction.

In relation to emotional intelligence, it was concluded that aside from looking to employ emotionally intelligent employees during the hiring processes, managers can put mechanisms that will allow personnel in the star-rated hotels to develop and build their emotional capabilities within the context of the work in the hotel. This will help them understand and manage their emotions with their work requirement and environment since they deal with visitors and customers from diverse backgrounds to not affect how they respond to and serve customers. Thus, maintaining a positive composure at the workplace irrespective of their encounters with customers, colleagues and managers.

29. Government policy implications

This study’s findings hold significant implications for government policies related to the hospitality industry. Governments could consider introducing regulations that prioritize the well-being of hotel employees. This might involve mandating training programs that enhance emotional intelligence skills and stress management techniques. Incentive programs, such as tax benefits or grants, could encourage star-rated hotels to invest in employee development, ultimately leading to improved psychological empowerment and job performance. Additionally, labour standards could be revised to ensure a healthier balance between job demands and resources, safeguarding the overall welfare of hotel staff.

30. Management practice implications

Hotel management can draw valuable insights from this study to enhance their practices. Prioritizing employee training and development in emotional intelligence could lead to improved interpersonal skills and better stress management. Encouraging psychological empowerment through initiatives like increased autonomy and skill-building opportunities could result in higher job satisfaction and performance. Managers could also redesign job roles to reduce excessive demands and allocate resources more effectively, aligning with the job demands-resource theory. These practices could create a positive work environment that fosters employee well-being and productivity.

31. Theory (job demands-resources theory) implications

The study enriches the job demands-resources theory by highlighting the importance of emotional intelligence and psychological empowerment. It suggests that emotional intelligence acts as a mediating factor, influencing how employees perceive and respond to job demands. This implies that interventions aimed at improving emotional intelligence could mitigate the negative impact of high job demands on performance. The study encourages a deeper exploration of moderating factors, such as organizational culture and leadership styles, to better understand how they interact with the proposed relationships. Overall, the study advances our understanding of how job demands and resources interact, providing new avenues for theory development and application.

32. Social impact

Employees with high emotional intelligence are better able to manage interpersonal relationships and communication, leading to more positive social interactions in the workplace. This can have a positive impact on team cohesion, job satisfaction, and overall organisational culture. Furthermore, employees who have higher levels of psychological empowerment and emotional intelligence may be more likely to engage in prosocial behaviour, such as helping colleagues, volunteering for additional tasks, and promoting teamwork. This can lead to a positive social impact within the organisation, promoting a culture of cooperation and collaboration.

33. Limitations and suggestion for future studies

Also, the instrument used did not permit respondents to give information other than the ones presented on the scale. This research adopted the cross-sectional design for data collection and relied on respondents’ assessment which was not checked with their superiors. This study was cross-sectional and restricted to only the star-rated hotels in the Central Region. Therefore, further studies should be undertaken in other parts of Ghana or the entire hotel industry. Future research could replicate this study on a longitudinal design to discover how psychological empowerment changes over a period and its influence on emotional intelligence and job performance in the long run. Also, prospective studies can consider measuring both employee and management job performance.

The motivation for the study

This study was inspired by the need to contribute to the survival and growth of the hospitality industry (hotels) in the Central Region of Ghana. More specifically, it has become a pressing demand to improve the job performance of hotel workers and the hotels’ workspace in the Region to meet international standards. Furthermore, the Region is known for attracting more tourists and visitors who visit the country due to its unique and numerous tourist sites. This has necessitated a hotel environment that is made up of emotionally stable, smart, motivated and empowered staff who understands their work roles and responsibilities and can deliver without continuous supervision from their superior.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Afsar, B., & Badir, Y. (2016). The mediating role of psychological empowerment on the relationship between person-organization fit and innovative work behaviour. Journal of Chinese Human Resource Management, 7(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHRM-11-2015-0016

- Al-Makhadmah, I. M., Al Najdawi, B. M., & Al-Muala, I. M. (2020). Impact of psychological empowerment on the performance of employees in the four- and five-star hotel sector in the dead Sea–Jordan tourist area. Geo Journal of Tourism and Geosites, 30(2 supplement), 896–904. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.302spl16-520

- Alonazi, W. B. (2020). The impact of emotional intelligence on job performance during COVID-19 crisis: A cross-sectional analysis. Psychology Research and Behaviour Management, 13, 749–757. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S263656

- Alwin, D. F., & Hauser, R. M. (1975). The decomposition of effects in path analysis. American Sociological Review, 40(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094445

- Amankwah-Amoah, J., Debrah, Y. A., Honenuga, B. Q., & Adzoyi, P. N. (2017). Business and government independence in emerging economies: Insights from hotels in Ghana. International Journal of Tourism Research, 20(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2154

- Amankwah, E., Sarfo, B., & Antwi, D. E. (2020). The impact of motivation on employee satisfaction and work performance within Ghana’s hospitality industry. GSJ, 8(7), 1699–1700.

- Anaman, A., & Dacosta, F. D. (2017). A conceptual review of the role of hotels in tourism development using hotels in Cape Coast and Elmina, Ghana. African Journal of Applied Research, 3(1), 45–58.

- Arshadi, N. (2010). Basic need satisfaction, work motivation, and job performance in an industrial company in Iran. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 1267–1272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.273

- Ashforth, B. E. (1989). The experience of powerlessness in organisations. Organisational Behaviour & Human Decision Processes, 43(2), 207–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(89)90051-4

- Asiamah, N. (2017). The nexus between health workers’ emotional intelligence and job performance: Controlling for gender, education, tenure and in-service training. Journal of Global Responsibility, 8(1), 10–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGR-08-2016-0024

- Awang, Z. (2014). A handbook on SEM for Academicians and practitioners: The step-by-step practical guides for the beginners. MPWS Rich Resources.

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands‐resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands–resources theory. Wellbeing: A complete reference guide. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118539415.wbwell019

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056

- Bakker, A., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. (2003). Dual processes at work in a call centre: An application of the job demands-resources model. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 12(4), 393–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320344000165

- Bakker, A. B., & de Vries, J. D. (2021). Job demands–resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 34(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1797695

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191.

- Bar-On, R. (1997). Bar-on emotional quotient inventory: Technical manual. Multi-Health Systems.

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Bar-On, R. E., & Parker, J. D. (2000). The handbook of emotional intelligence: Theory, development, assessment, and application at home, school, and in the workplace. Jossey-Bass.

- Bell, N. E., & Staw, B. M. (1989). Handbook of Career Theory (pp. 232–251).

- Bollen, K. A. (1987). Total, direct, and indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 17, 37–69. Retrieve from. https://doi.org/10.2307/271028

- Borman, W. C., & Motowidlo, S. J. (1997). Task performance and contextual performance: The meaning for personnel selection research. Human Performance, 10(2), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327043hup1002_3

- Brunetto, Y., Teo, S. T., Shacklock, K., & Farr‐Wharton, R. (2012). Emotional intelligence, job satisfaction, well‐being and engagement: explaining organisational commitment and turnover intentions in policing. Human Resource Management Journal, 22(4), 428–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2012.00198.x

- Campbell, J. P., & Wiernik, B. M. (2015). The modeling and assessment of work performance. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology & Organizational Behavior, 2(1), 47–74. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111427

- Chong, S. C., Falahat, M., & Lee, Y. S. (2020). Emotional intelligence and job performance of academicians in Malaysia. International Journal of Higher Education, 9(1), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v9n1p69.

- Commey, V., Sarkodie, N. A., & Frimpong, M. (2016). Assessing employee empowerment implementation in popular hotels in Sunyani, Ghana. International Journal of Educational Policy Research and Review, 3(5), 80–88.

- Conger, J. A., & Kanungo, R. N. (1988). The empowerment process: Integrating theory and practice. The Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 471–482. https://doi.org/10.2307/258093

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

- Dewettinck, K., Singh, J., & Buyens, D. (2003). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Reviewing the empowerment effects on critical work outcomes. 1–26. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12127/1029

- Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modelling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.2.02

- Edward, Y. R., & Purba, K. (2020). The effect analysis of emotional intelligence and work environment on employee performance with organisational commitment as intervening variable in PT berkat bima sentana. Budapest International Research and Critics Institute-Journal (BIRCI-Journal), 3(3), 1552–1563. https://doi.org/10.33258/birci.v3i3.1084

- Francis, R. S., & Alagas, E. N. (2020). Hotel employees’ psychological empowerment influence on their organisational citizenship behaviour towards their job performance. Organisational Behaviour Challenges in the Tourism Industry, 284–304. http://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-1474-0.ch016

- Francis, R. S., Alagas, E. N., & Jambulingam, M. (2018). Emotional intelligence, perceived organisation support and organisation citizenship behaviour: Their influence on job performance among hotel employees. Asia-Pacific Journal of Innovation in Hospitality and Tourism (APJIHT), 7(2), 1–20.

- Ghana Hotels Association. (2022). Membership. https://ghanahotelsassociation.com/membership/

- Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. Bantam Books.

- Gong, Z., Chen, Y., & Wang, Y. (2019). The influence of emotional intelligence on job burnout and job performance: Mediating effect of psychological capital. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02707

- Haenlein, M., & Kaplan, A. M. (2004). A beginner's guide to partial least squares analysis. Understanding Statistics, 3(4), 283–297.

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook. 197.

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed, a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Haneberg, L. (2011). Training for agility: Building the skills of employees need to zig and zag. Training and Development, 51–56.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modelling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hoover, K., & Donovan, T. (2008). The elements of social science thinking. Thomson/Wadsworth.

- Hur, Y., Van Den Berg, P. T., & Wilderom, C. P. (2011). Transformational leadership as a mediator between emotional intelligence and team outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(4), 591–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.05.002

- Idrus, S., Alhabji, T., Al Musadieq, M., & Utami, H. (2015). The effect of psychological empowerment on self-efficacy, burnout, emotional intelligence, job satisfaction, and individual performance. European Journal of Business and Management, 7(8), 139–148.

- International Labour Organisation. (2020). Sector skills strategy: Ghana tourism and hospitality sector. Internatimal Labour Organisation.

- Iqbal, Q., Ahmad, N. H., Nasim, A., & Khan, S. A. R. (2020). A moderated-mediation analysis of psychological empowerment: Sustainable leadership and sustainable performance. Journal of Cleaner Production 262, 121429. Retrieved from. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121429

- Javed, B., Khan, A. A., Bashir, S., & Arjoon, S. (2017). Impact of ethical leadership on creativity: The role of psychological empowerment. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(8), 839–851. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1188894

- Jung, H. S., & Yoon, H. H. (2012). The effects of emotional intelligence on counterproductive work behaviours and organisational citizenship behaviours among food and beverage employees in a deluxe hotel. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(2), 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.06.008

- Kamassi, A., Boulahlib, L., Abd Manaf, N., & Omar, A. (2019). Emotional labour strategies and employee performance: The role of emotional intelligence. Management Research Review, 43(2), 133–149. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-03-2019-0097

- Karimi, L., Leggat, S. G., Bartram, T., Afshari, L., Sarkeshik, S., & Verulava, T. (2021). Emotional intelligence: A predictor of employees’ well-being, quality of patient care, and psychological empowerment. BMC Psychology, 9(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00593-8

- Khan, J., Malik, M., & Saleem, S. (2020). The impact of psychological empowerment of project-oriented employees on project success: A moderated mediation model. Economic Research-Ekonomska istraživanja, 33(1), 1311–1329. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2020.1756374

- Kirrane, M., Kilroy, S., & O’Connor, C. (2018). The moderating effect of team psychological empowerment on the relationship between abusive supervision and engagement. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 40(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-07-2018-0252

- Kock, N. (2017). Common method bias: A full collinearity assessment method for PLS-SEM. In Partial least squares path modelling (pp. 245–257). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64069-3_11

- Kock, N., & Lynn, G. (2012). Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 13(7), 546–580. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00302

- Koopmans, L., Bernaards, C. M., Hildebrandt, V. H., Schaufeli, W. B., de Vet Henrica, C. W., & Van Der Beek, A. J. (2011). Conceptual frameworks of individual work performance: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 53(8), 856–866.

- Koopmans, L., Bernaards, C. M., Hildebrandt, V. H., van Buuren, S., van der Beek, A. J., & de Vet, H. C. (2015). Individual work performance questionnaire. Journal of Applied Measurement.

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308

- Langhorn, S. (2004). How emotional intelligence can improve management performance. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 16(4), 220–230.

- Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., & Sparrowe, R. T. (2000). An examination of the mediating role of psychological empowerment on the relations between the job, interpersonal relationships, and work outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 407–416. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.407

- Lipson, A. (2020). The Moderating Role of Emotional Intelligence on the Relationship between Job Resources and Employee Engagement. [ Doctoral dissertation], San Jose State University.

- Li, H., Shi, Y., Li, Y., Xing, Z., Wang, S., Ying, J., Zhang, M., & Sun, J. (2018). Relationship between nurse psychological empowerment and job satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74(6), 1264–1277. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13549

- Lupsa, D., Baciu, L., & Virga, D. (2019). Psychological capital, organisational justice and health: The mediating role of work engagement. Personnel Review, 49(1), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-08-2018-0292

- MacKinnon, D. P. (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Routledge.

- Mahmoud, M. A., Ahmad, S., & Poespowidjojo, D. A. L. (2021). Psychological empowerment and individual performance: The mediating effect of intrapreneurial behaviour. European Journal of Innovation Management, 25(5), 1388–1408. Retrieved from. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-12-2020-0517

- Marques-Quinteiro, P., Ramos-Villagrasa, P. J., Passos, A. M., & Curral, L. (2015). Measuring adaptive performance in individuals and teams. Team Performance Management, 21(7/8), 339–360. https://doi.org/10.1108/TPM-03-2015-0014

- Meng, Q., & Sun, F. (2019). The impact of psychological empowerment on work engagement among university faculty members in China. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 12, 983–990. Retrieved from. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S215912

- Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture. 2019).In Programme-based budget estimates, 2019-2022

- Najafi, S., Noruzy, A., Azar, H. K., Nazari-Shirkouhi, S., & Dalv, M. R. (2011). Investigating the relationship between organisational justice, psychological empowerment, job satisfaction, organisational commitment and organisational citizenship behaviour: An empirical model. African Journal of Business Management, 5(13), 5241–5248.

- Nitzl, C., Roldán, J. L., & Cepeda, G. (2017). Mediation analyses in partial least squares structural equation modelling, helping researchers discuss more sophisticated models: An abstract. Marketing at the Confluence Between Entertainment and Analytics, 693–693. Retrieved from. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47331-4_130

- O’Boyle, E. H., Jr., Humphrey, R. H., Pollack, J. M., Hawver, T. H., & Story, P. A. (2011). The relation between emotional intelligence and job performance: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 32(5), 788–818. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.714

- Okyireh, M. A., & Simpeh, K. N. (2016). Exploring the nature of psychological empowerment of women entrepreneurs in a rural setting in greater Accra, Ghana. Journal of Business, 4(6), 138–141.

- Ölçer, F., & Florescu, M. (2015). Mediating effect of job satisfaction in the relationship between psychological empowerment and job performance. Theoretical and Applied Economics, 22(3), 111–136.

- Pepra-Mensah, J., Adjei, L. N., & Yeboah-Appiagyei, K. (2015). The effect of work attitudes on turnover intentions in the hotel industry: The case of Cape Coast and Elmina (Ghana). European Journal of Business and Management, 7(14), 114–121.

- Quinn, R. E., & Spreitzer, G. M. (1997). The road to empowerment: Seven questions every leader should consider. Organizational Dynamics, 26(2), 37–49.

- Rahman, M. M., Tabash, M. I., Salamzadeh, A., Abduli, S., & Rahaman, M. S. (2022). Sampling techniques (probability) for quantitative social science researchers: A conceptual guidelines with examples. Seeu Review, 17(1), 42–51. https://doi.org/10.2478/seeur-2022-0023

- Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Schlittgen, R. (2014). Genetic algorithm segmentation in partial least squares structural equation modeling. OR Spectrum, 36, 251–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00291-013-0320-0

- Rotundo, M., & Sackett, P. R. (2002). The relative importance of task, citizenship, and counterproductive performance to global ratings of job performance: A policy-capturing approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.66

- Sanchez-Gomez, M., & Breso, E. (2020). In pursuit of work performance: Testing the contribution of emotional intelligence and burnout. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 5373.

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2014). A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health, 43–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5640-3_4

- Seibert, S. E., Wang, G., & Courtright, S. H. (2011). Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organisations: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(5), 981. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022676

- Shi, R., Meng, Q., & Huang, J. (2022). Impact of psychological empowerment on job performance of Chinese university faculty members: A cross-sectional study. Social Behaviour and Personality: An International Journal, 50(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.10975

- Shmueli, G., & Koppius, O. R. (2011). Predictive analytics in information systems research. MIS Quarterly, 35(3), 553–572. https://doi.org/10.2307/23042796

- Siaw, G. A., Khayiya, R., & Mugambi, R. (2018). Working conditions and work safety of hotel housekeepers in budget hotels of the eastern region of Ghana. International Journal of Research in Business, Economics and Management, 2(3), 181–192.

- Sinclair, R. R., & Tucker, J. S. (2006). Stress-CARE: An integrated model of individual differences in soldier performance under stress.

- Singh, M., & Sarkar, A. (2019). Role of psychological empowerment in the relationship between structural empowerment and innovative behavior. Management Research Review, 42(4), 521–538.

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465. https://doi.org/10.2307/256865

- Thomas, K. W., & Velthouse, B. A. (1990). Cognitive elements of empowerment: An “interpretive” model of intrinsic task motivation. Academy of Management Review, 15(4), 666–681. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1990.4310926

- Tummers, L. G., & Bakker, A. B. (2021). Leadership and job demand-resources theory: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. Retrieved from. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.722080

- Tuuli, M. M., & Rowlinson, S. (2009). Performance consequences of psychological empowerment. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 135(12), 1334–1347. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000103

- Ugwu, F. O., Onyishi, I. E., & Rodríguez-Sánchez, A. M. (2014). Linking organisational trust with employee engagement: The role of psychological empowerment. Personnel Review, 43(3), 377–400. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-11-2012-0198

- Wong, C. S., & Law, K. S. (2002). Wong and Law emotional intelligence scale. The Leadership Quarterly. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/t07398-000.

- World Travel and Tourism Council. (2021). Global Economic impact and trends. World Travel & Tourism Council. https://wttc.org/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/2021/Global%20Economic%20Impact%20and%20Trends%202021.pdf