Abstract

In the context of middle eastern countries like Saudi Arabia, the existing literature lacks in sufficient research on the impact of Transactional Leadership (TL) on job satisfaction (JS) and the indirect impact of extrinsic motivation (EM) and intrinsic motivation (IM) on achieving JS. This research investigates the direct influence of TL on JS and the indirect impact of EM and IM on achieving JS. The study defines compensation satisfaction (CS) and performance-based incentives (PBIs) as factors driving EM and employee empowerment (EE), while employee recognition drives (ER). Data were collected through survey questionnaires from 300 managers across different small, medium-sized, and large enterprises in Saudi Arabia. The analysis utilized partial least squares structural equation modeling. The findings indicate that both EM and IM significantly influence JS. The relationship between these motivations and job satisfaction is moderated by TL. Specifically, TL enhances the positive effects of EM on JS while attenuating the impact of IM. These results underscore the pivotal role of TL in establishing a connection between employee motivation and their job satisfaction level. This highlights the importance for businesses to cultivate a leadership style that aligns with the underlying motivations of their workforce, leading to improved staff morale and increased productivity. This study contributes a unique perspective by emphasizing TL’s significance within the organizational framework, particularly concerning job satisfaction and motivation in an evolving work landscape characterized by automation and remote work practices.

1. Introduction

Job satisfaction is a highly important construct in both the academic literature and managerial discourse, as evidenced in both theory and practice (Amin, Citation2021). Job satisfaction is correlated with positive factors such as greater productivity (Storey et al., Citation2019), innovation (Nguyen, Citation2020), and higher organizational performance (Dugan et al., Citation2019). Thus, high job satisfaction is always an end goal for managers and leaders within an organization. For managers, the literature provides insights into the factors that affect the manipulation and implementation of interventions to achieve higher job satisfaction (Wu et al., Citation2021). Meta-analytical studies such as those by Hoff et al. (Citation2020) suggest that interest fit is a precursor to job satisfaction, while Madigan and Kim (Citation2021) indicate that lowering workplace burnout is an antecedent. Miao et al. (Citation2017) argue that emotional intelligence helps employees develop job resources, which in turn creates long-lasting job satisfaction. Niskala et al. (Citation2020) compare the role of intrinsic and extrinsic factors in achieving job satisfaction and assert that intrinsic factors precede extrinsic ones. Although these meta-analytical and systematic review studies offer important insights into job satisfaction in organizations, fresh understanding is required to grasp job satisfaction in the current era, which is defined by technological disruption and a changing work culture.

Leadership has long been regarded as an important driver of employees’ job satisfaction (Eliyana et al., Citation2019). Empirical evidence also confirms that leaders who use communication skills, persuasion, and personality tend to influence employees’ job satisfaction (Staempfli & Lamarche, Citation2020). The theory of leadership is broad and various styles are documented in the literature. The transactional leadership style is one of the most significant leadership styles on which many studies have capitalized (Abdelwahed et al., Citation2022). Transactional leadership refers to the idea that leaders of an organization tend to influence their followers using an exchange instrument (Hasan & Islam, Citation2022). The exchange can include diverse elements such as rewards, punishments, and pleasantries (Alrowwad et al., Citation2020). Specifically, empirical research is extremely limited in the number and scope of studies on the relationship between transactional leadership and job satisfaction (Alarabiat & Eyupoglu, Citation2022). Thus, we hypothesized that, given the changing nature of the work structure and culture due to numerous factors, the transactional leadership style can play a significant role in enhancing job satisfaction compared with other leadership styles (Gemeda & Lee, Citation2020). Transactional leadership can be effective for employees in today’s world by assessing both the organization’s and the job’s relative contributions. Hence, the exchange of financial and non-financial rewards can be an important predictor of employees’ perceived satisfaction with their jobs (Hassi, Citation2019).

To establish a transactional leader’s influence, different set elements—such as financial motivation or extrinsic motivation as well as non-financial motivation or intrinsic motivation—can be utilized (Zen, Citation2023). The financial or external motivation necessary to create the transactional leadership style can include factors such as employees’ perceived satisfaction with their overall compensation (Nurlina, Citation2022) and performance-based incentives such as bonuses, pay raises, and promotions (Masa’deh et al., Citation2016). The literature suggests that compensation satisfaction is becoming highly important, especially in situations affected by the global rise in the prices of essential commodities. Employee satisfaction might not be achieved when employees perceive themselves to be inadequately paid (Nazir et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, performance appraisal is an effective tool for enhancing job satisfaction. An employee appraised more highly by a manager can be satisfied with a reward that includes generous bonuses, pay raises, and promotions (Cantarelli et al., Citation2016). However, non-financial or intrinsic motivation exchange tools can also be powerful in enhancing the influence of transactional leadership on job satisfaction. Based on the current literature, we posited that employee empowerment (Choi et al., Citation2016) and employee recognition (Tsarenko et al., Citation2018) would be important exchanges for job satisfaction as mediated by transactional leadership. Employee empowerment is becoming an important factor in the era of remote work and technology-assisted work structures. Empowered employees tend to work freely and complete tasks using technology-assisted tools. Employee empowerment can help boost both productivity (although this is beyond the scope of our research) and job satisfaction (Tariq et al., Citation2016). Finally, employee recognition is also a critical factor, as recognized employees see themselves as an important part of the organization, which tends to influence their overall satisfaction with their job and organization (Al-Emadi et al., Citation2015).

The exchange of external motivation factors (such as compensation satisfaction (Nazir et al., Citation2013) and performance-based incentives (Cantarelli et al., Citation2016) and intrinsic motivation factors (such as employee empowerment (Tariq et al., Citation2016) and employee recognition (Al-Emadi et al., Citation2015) can enhance job satisfaction through transactional leadership. However, empirical evidence in the context of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and large enterprises in Middle Eastern countries is limited. Past researchers, such as Masi and Cooke (Citation2000) and Andersen et al. (Citation2018), have capitalized on motivation and leadership. However, there is still a dearth of literature on the transactional leadership-mediated (Schwarz et al., Citation2020) exchange of motivational factors (both intrinsic and extrinsic), and job satisfaction.

Our study addresses a critical gap in the existing literature by presenting and testing a comprehensive conceptual framework that examines the mediating role of transactional leadership. By investigating the potential mediating effect of transactional leadership through intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, this study seeks to understand the impact of different parameters on job satisfaction.

Furthermore, the selection of our sample, which consists exclusively of managers, warrants an explanation. The rationale behind this decision stems from the inherent nature of transactional leadership, which often intersects more prominently with managerial roles due to its focus on structured exchanges and performance-based incentives. Additionally, we concur with the observation that empirical evidence on job satisfaction from regions such as Saudi Arabia is limited within the broader Middle Eastern context. Our research seeks to contribute significantly to this gap by collecting and analyzing data specifically from Saudi Arabia. The uniqueness of our investigation from this region provides a valuable opportunity to enrich the literature on job satisfaction within this specific context.

2. Literature review

2.1. Compensation satisfaction

Compensation is a widely used term in the academic literature on human resource (HR) management; it refers to the forms of financial and non-financial payments and quantifiable rewards that an employee receives in exchange for his/her services to the organization (Williams et al., Citation2008). The financial aspect of compensation can include a monthly salary, and/or—depending on the job contract—bonuses, commissions on sales, and other monetary incentives (Williams et al., Citation2007). In contrast, non-financial aspects of compensation may include health and group insurance, paid holiday vacations, and child/family support (Williams et al., Citation2007, Citation2008). Employee satisfaction with compensation is a basic requirement for many organizational behavioral variables such as job satisfaction (Igalens & Roussel, Citation1999), employee motivation (Jeha et al., Citation2022), less intention to switch jobs, and higher productivity (Samnani & Singh, Citation2014).

2.2. Employee recognition

The literature on the use of financial incentives to motivate employees and achieve performance and job satisfaction is vast (Abdullah et al., Citation2016); it offers important managerial insights into strategies to attain positive organizational behavioral objectives (Merino & Privado, Citation2015). In recent years, the debate has shifted toward the use of non-financial or non-cash-based elements to engender employee motivation and subsequent job satisfaction (Montani et al., Citation2020). A vital key concept for non-cash-based tools to enhance motivation is the recognition of an employee for being a highly valuable part of the organization (Magnus, Citation1981). Employee recognition can be explained as “judgment made about a person’s [the employee’s] contribution [to the organization], reflecting not just work performance but also personal dedication and engagement” (Brun & Dugas, Citation2008, p. 727). Recognition will strengthen employees’ sense of self-worth in the organization, causing them to see themselves as highly valued members; recognition will also help them to dispel their perceived work-related limitations to set higher targets and to devise innovative, sophisticated ways to achieve such targets.

2.3. Performance-based incentives

Performance-based incentives comprise a range of financial and non-financial incentives that employees receive because of positive performance appraisals conducted by their organization in coordination with managers (Aggarwal & Samwick, Citation2003). Performance appraisal is a routine activity undertaken by the HR department along with the managers and leaders of the organization. The primary purpose of performance appraisal is to “appraise” or assess an employee’s performance over a period of time (Liu et al., Citation2019). Performance is appraised based on a range of factors, including performance on the set of targets an employee receives (Coles & Li, Citation2020), behavioral factors such as absenteeism, and other non-behavioral factors such as technical competence and quality of work (Lin et al., Citation2022). Performance-based incentives can be categorized into financial incentives, which include pay rises and annual bonuses, and non-financial incentives, such as foreign-sponsored trips (Aggarwal & Samwick, Citation2003; Coles & Li, Citation2020).

2.4. Employee empowerment

The term “employee empowerment” refers to “employee participation [empowerment] in promotion, evaluation, job content, technological change, work standards, financial policies, cost control, organization[al] structure, work force size, safety programs, work methods, and pricing” (Nykodym et al., Citation1994). Employee empowerment has been a popular area for HR management researchers for several decades (Hanaysha, Citation2016). Today, employee empowerment is attracting a wide range of attention from scholars, as it has important managerial implications for the workplace (Tariq et al., Citation2016). At the behavioral level, employee empowerment is a powerful tool, as it brings many positive changes to employees and organizations (Hanaysha & Tahir, Citation2016). Employees themselves are becoming a vital source of employee motivation, particularly intrinsic motivation, productivity, and long-term commitment to the organization (Han et al., Citation2016). Employee empowerment inculcates a sense of responsibility and ownership toward one’s job, department, and organization, which translates into higher motivation and productivity in the workplace (Aghazamani & Hunt, Citation2017). Additionally, empowered employees are more creative and innovative, which leads to better problem-solving and new ideas. From a managerial or leadership perspective, employee empowerment has been correlated with greater employee satisfaction, increased employee retention rates, and reduced costs associated with turnover and training (Baird et al., Citation2018).

3. Theoretical framework of the research

The research is grounded in several key theoretical structures that provide the foundation for understanding the relationships and dynamics being explored:

3.1. Self-determination theory

The self-determination theory (SDT) asserts that individuals possess inherent psychological requirements for autonomy, competence, and a sense of connection. It discerns between intrinsic motivation (engaging in activities for personal gratification) and extrinsic motivation (participating for external inducements). SDT proposes that when individuals experience intrinsic motivation, they encounter elevated levels of well-being, contentment, and effectiveness. The degree of self-determination within extrinsic motivation varies, encompassing controlled to autonomous regulation.

3.2. Job characteristics model

The job characteristics model, conceived by Hackman and Oldham, underscores the influence of specific job attributes on motivation and job satisfaction. It outlines five fundamental job traits: skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, and feedback. The model postulates that roles characterized by these attributes amplify intrinsic motivation, culminating in favorable outcomes such as job satisfaction.

3.3. Transactional leadership theory

The transactional leadership theory delineates an exchange-based rapport between leaders and followers. It centers on task-focused conduct, contingent rewards, and the clarification of role expectations. The theory posits that transactional leaders offer extrinsic incentives (such as rewards and acknowledgment) as reciprocation for employee performance. Transactional leadership corresponds with extrinsic motivation, wherein external inducements steer employee conduct.

Current research integrates these theoretical frameworks to examine how extrinsic and intrinsic motivation influence job satisfaction, with a specific focus on the mediating role of transactional leadership. It posits that employees who are intrinsically motivated (driven by personal satisfaction) or extrinsically motivated (driven by external rewards) experience varying levels of job satisfaction. Transactional leadership serves as a potential mediator in this relationship. The framework suggests that transactional leaders, through contingent rewards and clarifying expectations, can amplify the impact of extrinsic motivation on job satisfaction. Simultaneously, transactional leadership may attenuate the link between intrinsic motivation and job satisfaction, as the external focus on rewards may overshadow the internal drive for satisfaction.

4. Hypotheses development

4.1. Compensation satisfaction and extrinsic motivation

Compensation Satisfaction (CS) refers to overall employee contentment with the amount of financial and non-financial rewards received by the organization in exchange for services provided (Stringer et al., Citation2011). The literature suggests that diverse factors can play a role in enhancing employees’ perceived satisfaction with compensation, such as fairness of pay. Employee motivation is an important aspect of compensation satisfaction. Employees who perceive their pay as fair and competitive are more likely to be satisfied with their compensation packages (Van Herpen et al., Citation2005). Employees who feel satisfied with their compensation will always be motivated toward their jobs and organizations, which can lead to higher job satisfaction (Litman et al., Citation2015). The concept of external motivation—which suggests that employee motivation is predetermined by the rewards employees receive in exchange for performing their jobs—considers compensation satisfaction to be a vital determinant. Compensation satisfaction reinforces positive energy among employees, which helps them to be even more driven in the workplace for their personal and professional development and the betterment of the organization (Olafsen et al., Citation2015). Thus, we posited the following:

H1:

There is a positive and significant relationship between Compensation Satisfaction and External Motivation.

4.2. Performance-based incentives and extrinsic motivation

Literature suggests that employees prefer financial incentives to non-financial ones, as prior incentives play an important role in enhancing motivation and perceptions of overall job satisfaction (Cao et al., Citation2019). This theoretical insight suggests the positive impact of performance-based Incentives on external motivation, which can ultimately enhance job satisfaction (Chien et al., Citation2020). Performance-based incentives improve employees’ external motivation through rewards received by an employee in exchange for targets such as sales, cost cutting, and innovation (Ormel et al., Citation2019). Rewards, specifically financial ones, are a necessary condition for an employee’s external motivation (Bruni et al., Citation2020). Thus, a more attractive financial-based incentive will energize employees to work actively toward their performance-based targets and attain higher performance on those targets (Aninanya et al., Citation2016). Employee motivation from incentives based on performance also plays a crucial role in enhancing job satisfaction.

H2:

There is a positive and significant relationship between performance-based incentives and employees’ external motivation.

4.3. Employee recognition and intrinsic motivation

Employee recognition is another important aspect of motivation (Hansen et al., Citation2002). However, employee recognition is very different compared to motivation derived from compensation satisfaction and performance-based incentives (Honore, Citation2009). Employee recognition directly strengthens intrinsic motivation, which is based on an employee’s internal drive to do better for the organization, department, and himself/herself as a valued member of the organization (Asaari et al., Citation2019). Employee recognition—which takes the form of written or verbal praise, or any other tool—enhances employees’ self-confidence and self-worth (Rai et al., Citation2018), which reinforce their basic beliefs about being responsible members of the organization whose actions will directly affect its overall performance (Howell et al., Citation2015). Thus, ongoing concern about working for the good of an organization and its betterment will keep employees intrinsically motivated to perform their jobs. Furthermore, intrinsic motivation derived from recognition can play an instrumental role in enhancing job satisfaction. Thus, we hypothesized the following:

H3:

There is a positive and significant relationship between employee recognition and intrinsic motivation.

4.4. Employee empowerment and intrinsic motivation

Employee empowerment has a significant impact on intrinsic motivation. Employee empowerment enhances intrinsic motivation through autonomy, meaningfulness at work, and responsibility (Tariq et al., Citation2016). Employees who feel autonomous at work become task- and innovation-oriented, which drives them to contribute positively to organizational performance (Inceoglu et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, employee empowerment makes one’s job and workplace feel meaningful; this engenders a sense of vision and purpose with which employees form their identities. Thus, meaningfulness and a sense of purpose enhance employees’ intrinsic motivation to work hard and to innovatively achieve a desired goal. Finally, employee empowerment creates a sense of responsibility (Wirtz & Jerger, Citation2016). The literature implies that empowered employees have a general sense of responsibility toward their jobs, performance targets, departments, and organizations. As such, a sense of responsibility toward one’s job, department, and organization automatically brings about intrinsic motivation, which helps employees to perform their duties. Hence, we posited the following:

H4:

There is a positive and significant relationship between employee empowerment and intrinsic motivation.

4.5. Employee intrinsic motivation and job satisfaction

Recent research has explored the impact of intrinsic motivation on job satisfaction, highlighting its role in enhancing employee well-being and organizational outcomes such as job satisfaction. Studies have revealed that employees who derive personal satisfaction from their tasks tend to experience higher levels of job satisfaction. Grounded in SDT, intrinsic motivation, characterized by autonomy, competence, and relatedness, has been recognized as a driving force behind employees’ contentment with their work. Furthermore, studies have also recognized the reciprocal nature of the relationship between intrinsic motivation and job satisfaction. While intrinsic motivation positively affects job satisfaction, satisfaction with one’s job also reinforces intrinsic motivation. Recent research has shown that employees who are content with their jobs are more likely to experience heightened intrinsic motivation, creating a mutually reinforcing cycle. In essence, the existing research provides insights for organizations aiming to cultivate intrinsic motivation as a means to enhance job satisfaction and foster a positive work environment. Thus, leading to the following hypothesis.

H5:

There is positive and significant relationship between intrinsic motivation and job satisfaction.

4.6. Employee extrinsic motivation and job satisfaction

Based on empirical findings, it becomes apparent that employees tend to achieve elevated levels of job satisfaction when they feel that their external requirements, including financial compensation and concrete advantages, are satisfactorily fulfilled. These outcomes align with the concept that extrinsic motivation, anchored in tangible incentives, plays a role in fostering employees’ contentment within their work roles. Furthermore, it is explored in the context of organizational context how the setting within an organization, encompassing elements like performance-linked incentives and acknowledgment initiatives, can amplify employees’ extrinsic motivation, thereby influencing their subsequent levels of job satisfaction. Scholarly investigations have shown that adeptly structured incentive systems tied to performance can elicit heightened motivation and satisfaction within the employee cohort. Furthermore, the imparting of substantial recognition and rewards to acknowledge employees’ contributions has been linked to augmented job satisfaction and favorable organizational outcomes. Thus, the existing research body provides insights for organizations aiming to strategically utilize extrinsic motivation to enhance job satisfaction and promote a positive work environment, resulting in the following hypothesis of the study:

H6:

There is positive and significant relationship between external motivation and job satisfaction

4.7. Extrinsic motivation and job satisfaction’s relationship mediated by transactional leadership

Workers and managers have a positive connection, and both transformational and transactional elements are associated with increased motivation and employee engagement in job satisfaction. According to Bass and Stogdill (Citation1990), transactional leaders use reward and punishment systems for their staff. Such systems are prevalent among leaders with strong instrumental motivation. However, Herzberg’s hygiene considerations are the source of motivation that transactional leaders use to compel their subordinates to work for them. A well-known form of leadership is transactional leadership, which places a strong emphasis on the fulfillment of agreements between a leader and his/her followers, as well as the exchange of rewards and penalties for performance (Sarros & Santora, Citation2001). Employees are more likely to feel satisfied with their jobs when they believe that their performance has been fairly rewarded (Saleem, Citation2015). According to a study, transactional leadership has a beneficial effect on job satisfaction, which is inextricably linked to performance (Chi et al., Citation2023). In addition, financial incentives act as mediator in the relationship between transactional leadership and job performance, indicating that a combination of the two may be effective in motivating people and boosting productivity. Another study points to a favorable correlation between transactional leadership and both intrinsic motivation and performance on the job (Khan et al., Citation2020). However, we found no evidence linking transactional leadership with job burnout or social shirking. Leaders in organizations are urged to embrace transactional leadership traits to motivate workers, increase morale, and improve productivity. Furthermore, one study explains why transactional leadership is vital to Saudi Arabia’s organizational management and change sustainability (Khan & Varshney, Citation2013). To fully grasp the dynamics of transactional leadership and its applicability to Saudi managers, more studies are needed at the national and regional levels in the Middle East and the Arab world. Additionally, Jensen et al. (Citation2019) highlight the need for clarity and application in both public and commercial organizations, addressing the limitations of current conceptualizations and measurements of transactional leadership (Jensen et al., Citation2019). This contributes to our knowledge of the link between leadership and performance by reconsidering leadership styles, and by creating and testing new metrics. Whenever the topic of motivation arises in academic or general discussions, intrinsic motivation is the type of motivation being discussed both directly and indirectly. Intrinsic motivation represents an employee’s internal, natural desire to engage in various organizational activities without directly seeking and asking for external rewards (Deci et al., Citation1981). A crucial consequence of intrinsic motivation is employees’ leadership capabilities (Barbuto, Citation2005). The connection between intrinsic motivation and leadership has been widely studied and empirically tested in the academic literature, offering highly insightful implications for both managers and researchers. Most studies conducted on motivation and leadership focus on leadership behaviors such as transactional behavior. This argument has been proven by recent meta-analytical studies conducted by Badura et al. (Citation2020), who suggest that transactional leadership is the most popular and widely preferred leadership style or behavior compared to others. However, the transactional leadership style can also be an effective leadership style with respect to intrinsic motivation with the right set of elements such as praise, celebration, and public acknowledgment of employees’ work. Another identified type of motivation is external motivation, which represents an employee’s drive to receive an external reward—most importantly money, which is financial and tangible—and to avoid punishment (Legault, Citation2020). External motivation is always external, whereby tangible, environmental, and other external factors can enhance motivation (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). One central aspect still missing from the academic debate is the link between external motivation and leadership. Motivation can play an instrumental role in improving employees’ leadership capabilities (Fisher, Citation2009). However, motivation, once defined in terms of external motivation and intrinsic motivation, may alter the leadership context. Leadership theory suggests that there are different styles through which a leader may try to influence his/her followers or subordinates (Miner, Citation2005). Hence, the relationship between external motivation and transactional leadership is understudied in the academic literature. External motivation and transactional leadership are highly similar, as both constructs rely on the instruments of rewards and punishments for employees to become motivated and to influence their workplace behavior. As such, we examined the relationship between intrinsic motivation and external motivation as mediated by transactional leadership, and we hypothesized the following:

H7:

There is a positive and significant mediating effect of transactional leadership between intrinsic motivation and job satisfaction.

H8:

There is a positive and significant mediating effect of transactional leadership between external motivation and job satisfaction.

5. Research methods

5.1. Research design and approach

We aimed to understand job satisfaction and posited that transactional leadership would play an instrumental role in enhancing employees’ job satisfaction. We further hypothesized that transactional leadership—which uses the instrument of exchange as a tool to influence employees or subordinates—can be driven by factors that are part of external motivation (such as compensation satisfaction and performance-based incentives) and intrinsic motivation (such as employee empowerment and employee recognition). Since our goal was to empirically test Job satisfaction based on a range of factors, we used a quantitative research design (Bloomfield & Fisher, Citation2019). This design helped us collect data on each factor of job satisfaction and subsequent factors, and to employ statistical methods to test the relationship (Black, Citation1998). For data collection, we employed a survey questionnaire and partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) for data analysis. We collected data from managers of SMEs and large enterprises in Saudi Arabia.

5.2. Data collection instrument

The survey questionnaire was the combination of adopted instruments for each of the study variable separately (see Table ) to gather data (Martin, Citation2006), which are widely used for data collection in quantitative research (Taherdoost, Citation2016) as well as in the empirical context of organizational behavior. The survey questionnaire comprised three parts. With the first part, we attempted to capture demographic data, which are important for generalizing the results of the sample to the broader population. The second part consisted of items to assess respondents’ knowledge of critical factors such as leadership, motivation, and job satisfaction. The third part involved items for each construct of the study, as mentioned in the conceptual framework. We used a 5-point Likert scale to measure each construct of the conceptual framework (Joshi et al., Citation2015). We collected data from 306 managers working in various SMEs and large enterprises in Saudi Arabia, including different manufacturing sectors. Table presents the number of items for each construct and their sources. Performance-based bonuses focus on financial rewards for exceptional work done by a person or group; the section focused on this area has six questions used to evaluate the success of performance-based pay plans. Employees’ happiness with their pay (including salary, perks, and bonuses) is measured by the construct of compensation satisfaction based on a 10-item scale that asks workers to rate their Job satisfaction and pay. The term “job satisfaction” is used to describe how happy or unhappy an individual is with his/her current position. The section regarding this term contains 10 questions designed to gauge how satisfied an employee is with his/her job in terms of diverse factors, including working conditions, interpersonal interactions, and career development prospects. Employee empowerment measures the extent to which workers are trusted with responsibility, independence, and decision-making at their jobs; eight questions are asked to gauge how workers feel about their autonomy at work. We quantified the extent to which workers believe that their efforts and contributions are acknowledged using the construct of employee recognition. The section for this concept has six questions that evaluate the official and informal methods of appreciation used by the company.

Table 1. Data collection instrument

The term “intrinsic motivation” describes the inspiration and pleasure one gets from doing something for its own sake. Eight components make up this construct and measure how interested workers are in their jobs for their own sake. Motivation that comes from outside a person, or external motivation, includes incentives, praise, and penalties. The section for external motivation consists of six questions designed to establish the degree to which workers are driven by money or other rewards. Transactional leadership is rooted in the exchange of incentives and penalties for performance. The four elements constituting transactional leadership examine the prevalence and efficacy of the transactional leadership style.

5.3. Sampling and population

Our goal was to examine job satisfaction based on transactional leadership as well as the factors of intrinsic motivation and external motivation by collecting data from managers working at SMEs in Saudi Arabia. Thus, this study has considered the population that worked at various managerial level posts. The rationale behind positioning our empirical setting at firms in Saudi Arabia relates to the general empirical research gap that exists in the literature, which calls for understanding organizational behavioral phenomena within Saudi Arabia, since most research has been conducted by gathering data from Western countries and some eastern ones (such as China, Malaysia, Indonesia, and India). Empirical research conducted in the greater Middle East and Saudi Arabia is limited; thus, we attempted to fill this critical gap in the literature. Due to the size and unknown composition of the population in the current study (i.e., employees working in SMEs and large enterprises in Saudi Arabia), we employed a non-probability sampling technique (Vehovar et al., Citation2016). We also conducted purposive sampling to collect as much data as possible from an intended group of respondents who are managers working in SMEs and large enterprises in Saudi Arabia (Etikan et al., Citation2016). We utilized the software G*Power to determine the sample size by using the t-test family with a statistical test of linear bivariate regression in one group, where the alpha error probability was set at 0.05. In survey research, one sample * power is a frequently employed sample of G*Power (Kang, Citation2021). The results showed a recommended sample size of 290. By rounding the number, this study set the sample size of 300 as an appropriate size for data collection.

5.4. Demographic analysis

We employed IBM-SPSS (version 25.0) to perform demographic analysis of the data to understand the sample’s characteristics. Appendix I presents the outcomes of this analysis. The majority of the sample was male (71.3%). The age group did not show any major trend, but the majority belonged to two groups: 26–35 (38.9%) and 36–45 (28.9%). As for education level, the majority had completed undergraduate (39%), post-graduate (32.4%), and other levels of education (17.8%). As for roles at work, we included four categories: manager (32%), senior manager (22%), head of the department (27%), and chief executive officer (19%). Regarding years of work experience, 11% of the sample had 0–2 years of experience; 32% had 3–5 years of experience; 28% had 5–7 years of experience; 17% had 7–9 years of experience; 5% had 9–11 years of experience, and 7% had 12 or more years of experience. Finally, the different firm sizes showed an adequate distribution. The results indicated that 24% of the sample worked at small firms, 32% at medium firms, 27% at small and medium firms, and 17% at large firms.

5.5. Methodology

We employed PLS-SEM utilizing SmartPLS 4 for data analysis (Hair et al., Citation2011). PLS-SEM is a widely used tool for assessing the cause and effect of relationships between complex conceptual and path models (Hair et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, we assessed the data using both measurement and structural models. We harnessed the measurement model to evaluate the relative validity and reliability of both the data and the data collection instrument through a range of statistical analyses and tests (). We also used a structural model for which we applied bootstrapping procedures by creating 5,000 subsamples to assess our hypotheses. We also employed IBM SPSS to analyze the respondents’ demographic data. Hence, we used two different software packages: IBM-SPSS (version 25.0), and SmartPLS 4. We summarize the results in the following sections.

6. Empirical results

6.1. Construct validity and reliability

We assessed construct reliability—which refers to the internal consistency of measures with their construct—using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (Peterson & Kim, Citation2013). The literature suggests that both Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability values above 0.70 can be considered constructs achieving reliability (Hair et al., Citation2019). The results, as depicted in Table , indicate that each of the constructs achieved reliability, as both the value of the correlation alpha and composite reliability were higher than 0.70. We assessed construct validity using the average variance extracted (AVE). The literature suggests a threshold value of 0.50 for assuming that construct validity has been achieved (Zaiţ & Bertea, Citation2011). The findings in Table imply that each construct achieved validity, as each construct reported an AVE value higher than 0.50.

Table 2. Reliability and validity of study variables

6.2. Discriminant validity

Discriminant validity refers to a construct’s ability to differentiate itself from other constructs in the research model and measure its own unique phenomena (Zaiţ & Bertea, Citation2011). PLS-SEM allows researchers to assess discriminant validity using the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT). HTMT is a powerful tool for assessing the discriminant validity of a PLS-SEM model. Hair et al. (Citation2021) suggest that an HTMT value below 0.90 can be considered a threshold value to assume that a construct has achieved discriminant validity. The results, as seen in Table , indicate that each construct achieved an HTMT value below 0.90; hence, we can deduce that discriminant validity was achieved in the current research.

Table 3. Heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations

Comparing the square roots of AVE values to the off-diagonal values in the rows above. Thesubstantial discriminant reliability is established when the covariate within a construct surpasses the covariate involving other constructs. The current findings, as per Fornell and Larcker’s criteria (1981), are presented in Table . The square roots of AVE values in the table surpass the off-diagonal values above them. Consequently, significant discriminant validity is consistent with Fornell and Larcker’s criteria (1981).

Table 4. Discriminant validity based on forner-larcker criteria

6.3. Measurement model

6.3.1. Structural model 1

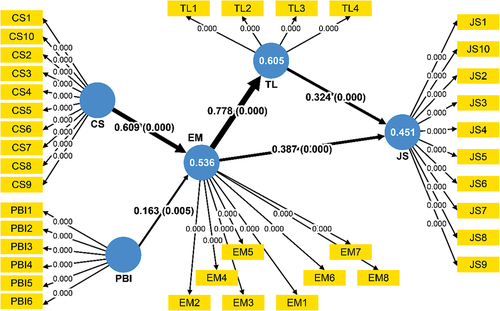

We assessed Structural Model 1 to test both our direct and indirect hypotheses, considering compensation satisfaction (CS), performance-based incentives (PBIs), extrinsic motivation (EM), and job satisfaction (JS), as well as transactional leadership (TL) as a mediator variable. The model fit was determined with an NFI value of 0.851 and an SRMR value of 0.062 (<0.08). Thus, the structural model was considered fit following . We assessed the data via the structural model using a bootstrapping procedure to create 5,000 subsamples. This model shows the relationships between CS, PBIs, EM, and JS, as well as the mediating effect of TL. In addition to these relationships, we examined the acceptance of H1, H2, H6 and H8. Figure presents a graphical representation of the data that displays the path coefficient and p-values in brackets. The results indicate that all of the hypotheses were accepted. Tables depict the detailed outcomes of the direct and indirect effects.

Table 5. Direct effect among the variables

Table 6. Indirect effect among the variables

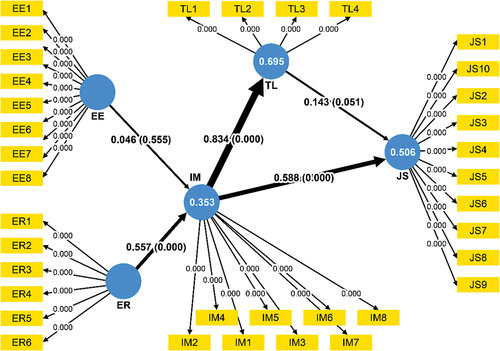

6.3.2. Structural model 2

We investigated Structural Model 2 to test both the direct and indirect hypotheses, considering employee engagement (EE), employee recognition (ER), intrinsic motivation (IM), and JS, as well as TL as a mediator variable. The model fit was determined with an NFI value of 0.701 (>0.60) and an SRMR value of 0.069 (<0.08). Thus, the structural model was considered fit following Hair et al. (Citation2010). We assessed the data via the structural model using a bootstrapping procedure to create 5,000 subsamples. This model shows the relationships among EE, ER, IM, and JS, and investigates the mediating effect of TL. In addition to these relationships, we examined the acceptance of H3, H4, H5 and H7. Figure presents a graphical representation of the data, which shows the path coefficient and p-values in brackets. The outcomes indicate that all of the hypothesis paths were accepted, except for H4. The p-value of the hypothesis was 0.555, which was greater than the acceptable p-value range (P < 0.05). Tables display the detailed results for the direct and indirect effects.

Table 7. Direct effect among the variables

Table 8. Indirect effect among the variables

6.4. Hypotheses testing and analysis

Table outlines the testing of the hypotheses, the results of which imply a positive and significant relationship between CS and EM, as well as between PBIs and employees’ EM. Additionally, there is a positive and significant relationship between ER and IM. However, we rejected the hypothesis suggesting a positive and significant relationship between EE and IM due to insufficient evidence. A positive and significant relationship exists between IM and JS. A significant positive relationship is found between EM and JS. Furthermore, there is a positive and significant mediating effect of TL between IM and JS, as well as between EM and JS. These findings provide valuable insights into the interplay of factors influencing motivation and JS in the context of our study. Among the accepted hypotheses, H1 shows the strongest path coefficient (0.609). Regarding a direct relationship, CS influences IM significantly. H2 reveals the smallest path coefficient (01.69). PBIs do not influence EM more significantly. In terms of the mediator variable, the highest path coefficient of EM -> TL -> JS (H6) is 0.252. The mediator, TL, has the most significant mediator effect between EM and JS.

Table 9. Results of hypothesis testing

7. Discussion

Job satisfaction remains a major problem for managers who supervise employees. Many researchers have been trying to establish important and insightful research models to conceptualize job satisfaction in this context. This research also provides vital insights into job satisfaction in the changing work culture and structure, and stresses the role and development of transactional leadership as a critical predictor of job satisfaction. The current literature offers insights into the role of leadership in various aspects of organizational behavior, including job satisfaction. The focus on transactional leadership is based on the assertion that it is effective in achieving job satisfaction through rewards and recognition by creating a clear set of expectations through employees, performance-based incentives, and empowerment. We divided these factors into two sets of motivation—intrinsic motivation and external motivation—that directly affect transactional leadership and indirectly yield job satisfaction, compensation satisfaction, employee empowerment, external motivation, employee recognition, intrinsic motivation, job satisfaction, performance-based incentives, and transactional leadership.

7.1. Motivation

Employee motivation is an important organizational behavioral variable that has been widely studied. The current literature suggests that motivation plays a vital role in enhancing both leadership capacity and job satisfaction. We theorized that motivation has two aspects: intrinsic and extrinsic. External motivation refers to an employee’s drive to receive an external reward—most importantly money, which is financial and tangible—and to avoid punishment (Legault, Citation2020). Intrinsic motivation is an employee’s internal, natural desire to engage in various organizational activities without directly seeking or asking for an external reward (Deci et al., Citation1981). We posited that the two-factor compensation satisfaction (Litman et al., Citation2015; Olafsen et al., Citation2015) and performance-based incentives (Cao et al., Citation2019; Coles & Li, Citation2020) would have direct and significant impacts on external motivation. The data collected using a survey questionnaire and the analysis of data using PLS-SEM suggest that both compensation satisfaction and performance-based incentives have a positive and direct impact on employees’ external motivation. The results clearly indicate that financial exchanges (e.g., adequate levels of compensation) and performance-based incentives, which can include variables such as bonuses and pay raises, play an important role in maintaining employee motivation. Furthermore, the indirect effects of compensation satisfaction and performance-based incentives are also positively significant. Thus, we can conclude that these financial exchange tools not only create motivation among employees, but also help establish and foster transactional leadership capabilities among them. We also theorized that intrinsic motivation is a critical variable in the organizational setting of modern work structures. Two factors, employee empowerment (Aghazamani & Hunt, Citation2017; Baird et al., Citation2018) and employee recognition (Asaari et al., Citation2019; Montani et al., Citation2020), have been conceptualized as having a direct and significant impact on intrinsic motivation. The PLS-SEM analysis showed mixed results. The outcomes indicate that employee recognition had a positive and significant effect on intrinsic motivation. Hence, we can deduce that recognizing employees’ extra efforts can be an important source of their motivation in the workplace. The indirect effect analysis also reveals that recognizing employees could foster transactional leadership capabilities. However, the results do not support any role of employee empowerment, either directly for intrinsic motivation or indirectly for transactional leadership through intrinsic motivation. The current literature, such as studies by DiDomenico and Ryan (Citation2017), suggests that other factors like autonomy, mastery, and purpose are just a few of the qualities that can significantly affect intrinsic motivation. The current study might not have captured all elements that effect intrinsic motivation if simply focusing on employee empowerment, which may lead to a negligible association between employee empowerment and intrinsic motivation.

7.2. Transactional leadership

We theorized that transactional leadership would be powered by intrinsic motivation and external motivation as a source of job satisfaction. Leadership research is broad, and prior studies suggest that leadership can play an important role in organizations (Uhl-Bien & Arena, Citation2018). However, researchers place less stress on transactional leadership than on transformational leadership (Mach et al., Citation2022). The research has also conceptualized transactional leadership as the source of job satisfaction based on the assertion that, to establish a productive workplace that encourages motivation and engagement, this leadership style relies on the usage of rewards and recognition, as well as a clear set of expectations from workers. Transactional leaders can provide their staff with the skills and resources needed to become successful in their profession using performance-based rewards and empowerment, which may have a substantial influence on job satisfaction (Dartey-Baah & Ampofo, Citation2016; Saleem, Citation2015). Apart from job satisfaction as a consequence of transactional leadership, we also hypothesized that both external motivation (Devloo et al., Citation2015) and intrinsic motivation (Jensen, Citation2018) would be sources of transactional leadership. Moreover, we conceptualized the roles of intrinsic motivation and external motivation based on the assertion that although intrinsic motivation is fueled by internal elements (such as personal contentment or a feeling of purpose), external motivation is fueled by external benefits (such as income, promotions, or recognition). Extrinsically motivated transactional leaders may be more prone to utilize performance-based incentives (such as bonuses or promotions) to inspire their staff and achieve job satisfaction. Transactional leaders can also employ intrinsic motivation to offer opportunities for professional and personal development, such as training programs or the ability to work on worthwhile initiatives.

The results suggest that both intrinsic motivation and external motivation have a positive and significant impact on transactional leadership. Thus, we can infer that the exchange of intrinsic motivation factors, such as employee recognition and external motivation, can have a positive impact on transactional leadership. The findings further demonstrate the positive and significant effects of transactional leadership on job satisfaction. Finally, the indirect effects of both intrinsic motivation and external motivation have also been established. Thus, we can deduce that transactional leaders using various intrinsic motivation and external motivation tools have an adequate capacity to achieve Job satisfaction among employees.

8. Implications of the study

8.1. Theoretical implications

In the field of modern work structures, job satisfaction emerges as a pivotal managerial concern. This study reveals the essential role of transactional leadership in achieving job satisfaction, shedding light on a dimension historically underemphasized in comparison to transformational leadership. Leaders’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation significantly shape their transactional leadership style, with positive effects observed for both intrinsic and external motivation. This suggests the potential for enhancing transactional leadership through staff incentives and praise. Notably, a robust link between transactional leadership and employees’ happiness underscores the positive impact of transactional leaders on workforce contentment. Additionally, job satisfaction is directly influenced by intrinsic motivation and indirectly by external motivation, implying that transactional leaders’ use of both motivation types can elevate employees’ happiness. These findings underscore the dual significance of intrinsic motivation and external motivation in transactional leadership development, offering businesses insights to foster effective leadership practices and enhance employee well-being.

8.2. Practical implications

The practical implications drawn from these findings hold significant value for managerial practices in modern work environments. Given the growing importance of job satisfaction, managers are urged to adopt innovative strategies to enhance it. This study underscores the pivotal role of transactional leadership in achieving job satisfaction, filling a historical research gap in its recognition. The notable influence of leaders’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation on their transactional leadership style implies actionable steps for improvement through staff incentives and acknowledgment. The robust link between transactional leadership and employees’ happiness underscores the positive impact of transactional leaders, offering a pathway to elevate workforce contentment. Moreover, the study’s revelation that both intrinsic motivation and external motivation directly contribute to work satisfaction highlights the potential for enhancing employee happiness through transactional leaders’ combined use of motivation tactics. By leveraging internally motivating elements and applying extrinsic motivators, such as recognition and awards, transactional leaders can significantly impact employees’ job satisfaction. These findings provide practical guidance for organizations aiming to cultivate effective leadership practices, create motivating work environments, and ultimately bolster employee well-being and satisfaction.

9. Conclusion

Job satisfaction is becoming a crucial source of managerial concern in today’s world of modern work structures. Managers must work innovatively to achieve job satisfaction. We concluded that transactional leadership plays a role in achieving job satisfaction. The role of transactional leadership has historically been ignored or stressed less by researchers than that of transactional leadership. The results indicate that leaders’ levels of intrinsic motivation and external motivation significantly contribute to determining their transactional leadership style. We observed positive and substantial effects of both intrinsic motivation and external motivation on transactional leadership. This finding implies that transactional leadership can be improved through staff incentives and praise. In addition, the results show a favorable and statistically significant link between transactional leadership and employees’ happiness. It follows that workers are more content in their roles when they are led by transactional leaders. Furthermore, work satisfaction was influenced both directly by intrinsic motivation and indirectly by external motivation. Employees’ happiness at work may be increased by transactional leaders’ use of both intrinsic motivation and external motivation tactics. The results indicate that intrinsic motivation and external motivation are equally crucial to the development of transactional leadership. Transactional leaders may have a significant effect on employees’ job satisfaction by capitalizing on internally motivating elements and applying extrinsic motivators, such as recognition and awards. These findings highlight the value of motivating tools in transactional leadership and provide guidance to businesses seeking to cultivate effective leadership practices and boost their employees’ happiness.

9.1. Limitations and future research

Future studies that include employee empowerment could shed light on the relationship between transactional leadership and job content. Future research might benefit from considering culture as a factor in determining whether a person is happy and motivated at work. Understanding cross-cultural differences in leadership styles and motivational approaches may require an investigation of the relationship between cultural influences, transactional leadership, and other motivational approaches. In addition, future studies could broaden the focus outside of Saudi Arabia, which would help make the results more applicable to the global population. Researchers may gain a deeper understanding of the generalizability of the theoretical implications offered by gathering data from a variety of cultural settings. Future research needs to compare the transactional leadership style with other management styles, such as ethical style (Al Halbusi et al., Citation2021b) and servant style (Ruiz-Palomino et al., Citation2019; Ruiz-Palomino et al. 2021). Specifically, the future research should explore the impact of ethical and servant leadership on employee satisfaction in contrast to transactional leadership. This will involve an investigation into how these leadership styles affect various aspects of employee satisfaction, including job satisfaction and motivation. Overall, advancing our knowledge of the connection between transactional leadership, motivation, and work satisfaction will help overcome this study’s limitations and provide opportunities for future studies.

Geolocation information

Saudi Arabia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Abdelwahed, N. A. A., Soomro, B. A., & Shah, N. (2022). Predicting employee performance through transactional leadership and entrepreneur’s passion among the employees of Pakistan. Asia Pacific Management Review, 28(1), 60–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2022.03.001

- Abdullah, N., Shonubi, O. A., Hashim, R., & Hamid, N. (2016). Recognition and appreciation and its psychological effect on job satisfaction and performance in a Malaysia IT company: Systematic review. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 21(9), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-2109064755

- Aggarwal, R. K., & Samwick, A. A. (2003). Performance incentives within firms: The effect of managerial responsibility. The Journal of Finance, 58(4), 1613–1650. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6261.00579

- Aghazamani, Y., & Hunt, C. A. (2017). Empowerment in tourism: A review of peer-reviewed literature. Tourism Review International, 21(4), 333–346. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427217X15094520591321

- Alarabiat, Y. A., & Eyupoglu, S. (2022). Is silence golden? The influence of employee silence on the transactional leadership and job satisfaction relationship. Sustainability, 14(22), 15205. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215205

- Al-Emadi, A. A. Q., Schwabenland, C., & Wei, Q. (2015). The vital role of employee retention in human resource management: A literature review. IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14(3), 7.

- Al Halbusi, H., Ruiz-Palomino, P., Jimenez-Estevez, P., & Gutiérrez-Broncano, S. (2021b). How upper/Middle managers’ ethical leadership activates employee ethical behavior? The role of organizational justice perceptions among employees. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 652471. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.652471

- Alrowwad, A. A., Abualoush, S. H., & Masa’deh, R. E. (2020). Innovation and intellectual capital as intermediary variables among transformational leadership, transactional leadership, and organizational performance. Journal of Management Development, 39(2), 196–222. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-02-2019-0062

- Amin, F. A. B. M. (2021). A review of the job satisfaction theory for special education perspective. Turkish Journal of Computer & Mathematics Education (TURCOMAT), 12(11), 5224–5228.

- Andersen, L. B., Bjørnholt, B., Bro, L. L., & Holm-Petersen, C. (2018). Leadership and motivation: A qualitative study of transformational leadership and public service motivation. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 84(4), 675–691. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852316654747

- Aninanya, G. A., Howard, N., Williams, J. E., Apam, B., Prytherch, H., Loukanova, S., Kamara, E. K., & Otupiri, E. (2016). Can performance-based incentives improve motivation of nurses and midwives in primary facilities in northern Ghana? A quasi-experimental study. Global Health Action, 9(1), 32404. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v9.32404

- Asaari, M. H. A. H., Desa, N. M., & Subramaniam, L. (2019). Influence of salary, promotion, and recognition toward work motivation among government trade agency employees. International Journal of Business & Management, 14(4), 48–59. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v14n4p48

- Badura, K. L., Grijalva, E., Galvin, B. M., Owens, B. P., & Joseph, D. L. (2020). Motivation to lead: A meta-analysis and distal-proximal model of motivation and leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(4), 331. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000439

- Baird, K., Su, S., & Munir, R. (2018). The relationship between the enabling use of controls, employee empowerment, and performance. Personnel Review, 47(1), 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-12-2016-0324

- Barbuto, J. E., Jr. (2005). Motivation and transactional, charismatic, and transformational leadership: A test of antecedents. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 11(4), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/107179190501100403

- Bass, B. M., & Stogdill, R. M. (1990). Bass & Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications. Simon and Schuster.

- Black, T. R. (1998). Doing quantitative research in the social sciences: An integrated approach to research design, measurement and statistics. Sage.

- Bloomfield, J., & Fisher, M. J. (2019). Quantitative research design. Journal of the Australasian Rehabilitation Nurses Association, 22(2), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.33235/jarna.22.2.27-30

- Brun, J. P., & Dugas, N. (2008). An analysis of employee recognition: Perspectives on human resources practices. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(4), 716–730. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190801953723

- Bruni, L., Pelligra, V., Reggiani, T., & Rizzolli, M. (2020). The pied piper: Prizes, incentives, and motivation crowding-in. Journal of Business Ethics, 166(3), 643–658. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04154-3

- Cantarelli, P., Belardinelli, P., & Belle, N. (2016). A meta-analysis of job satisfaction correlates in the public administration literature. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 36(2), 115–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X15578534

- Cao, X., Lemmon, M., Pan, X., Qian, M., & Tian, G. (2019). Political promotion, CEO incentives, and the relationship between pay and performance. Management Science, 65(7), 2947–2965. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2017.2966

- Chien, G. C., Mao, I., Nergui, E., & Chang, W. (2020). The effect of work motivation on employee performance: Empirical evidence from 4-star hotels in Mongolia. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism, 19(4), 473–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332845.2020.1763766

- Chi, H., Vu, T. V., Nguyen, H. V., & Truong, T. H. (2023). How financial and non–financial rewards mediate the relationships between transformational leadership, job satisfaction, and job performance. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2173850. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2173850

- Choi, S. L., Goh, C. F., Adam, M. B. H., & Tan, O. K. (2016). Transformational leadership, empowerment, and job satisfaction: The mediating role of employee empowerment. Human Resources for Health, 14(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-016-0171-2

- Coles, J. L., & Li, Z. (2020). Managerial attributes, incentives, and performance. The Review of Corporate Finance Studies, 9(2), 256–301. https://doi.org/10.1093/rcfs/cfaa004

- Dartey-Baah, K., & Ampofo, E. (2016). Carrot and stick” leadership style: Can it predict employees’ job satisfaction in a contemporary business organisation? African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 7(3), 328–345. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJEMS-04-2014-0029

- Deci, E. L., Nezlek, J., & Sheinman, L. (1981). Characteristics of the rewarder and intrinsic motivation of the rewardee. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.40.1.1

- Devloo, T., Anseel, F., De Beuckelaer, A., & Salanova, M. (2015). Keep the fire burning: Reciprocal gains of basic need satisfaction, intrinsic motivation and innovative work behaviour. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(4), 491–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2014.931326

- DiDomenico, S. I., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). The emerging neuroscience of intrinsic motivation: A new frontier in self-determination research. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 145. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00145

- Dugan, R., Hochstein, B., Rouziou, M., & Britton, B. (2019). Gritting their teeth to close the sale: The positive effect of salesperson grit on job satisfaction and performance. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 39(1), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853134.2018.1489726

- Eliyana, A., & Ma’arif, S. (2019). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment effect in the transformational leadership towards employee performance. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 25(3), 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2019.05.001

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

- Fisher, E. A. (2009). Motivation and leadership in social work management: A review of theories and related studies. Administration in Social Work, 33(4), 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/03643100902769160

- Gemeda, H. K., & Lee, J. (2020). Leadership styles, work engagement and outcomes among information and communications technology professionals: A cross-national study. Heliyon, 6(4), e03699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03699

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage.

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hanaysha, J. (2016). Examining the effects of employee empowerment, teamwork, and employee training on organizational commitment. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 229, 298–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.07.140

- Hanaysha, J., & Tahir, P. R. (2016). Examining the effects of employee empowerment, teamwork, and employee training on job satisfaction. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 219, 272–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.016

- Hansen, F., Smith, M., & Hansen, R. B. (2002). Rewards and recognition in employee motivation. Compensation & Benefits Review, 34(5), 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886368702034005010

- Han, S. H., Seo, G., Li, J., & Yoon, S. W. (2016). The mediating effect of organizational commitment and employee empowerment: How transformational leadership impacts employee knowledge sharing intention. Human Resource Development International, 19(2), 98–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2015.1099357

- Hasan, I., & Islam, M. N. (2022). Leadership instills organizational effectiveness: A viewpoint on business organizations. SN Business & Economics, 2(3), 26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-021-00193-z

- Hassi, A. (2019). “You get what you appreciate”: Effects of leadership on job satisfaction, affective commitment and organisational citizenship behaviour. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 27(3), 786–811. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-08-2018-1506

- Hoff, K. A., Song, Q. C., Wee, C. J., Phan, W. M. J., & Rounds, J. (2020). Interest fit and job satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 123, 103503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103503

- Honore, J. (2009). Employee motivation. Consortium Journal of Hospitality & Tourism, 14(1), 63–75.

- Howell, T. M., Harrison, D. A., Burris, E. R., & Detert, J. R. (2015). Who gets credit for input? Demographic and structural status cues in voice recognition. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(6), 1765. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000025

- Igalens, J., & Roussel, P. (1999). A study of the relationships between compensation package, work motivation and job satisfaction. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20(7), 1003–1025. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199912)20:7<1003:AID-JOB941>3.0.CO;2-K

- Inceoglu, I., Thomas, G., Chu, C., Plans, D., & Gerbasi, A. (2018). Leadership behavior and employee well-being: An integrated review and a future research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 179–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.12.006

- Jeha, H., Knio, M., & Bellos, G. (2022). The impact of compensation practices on employees’ engagement and motivation in times of COVID-19. COVID-19: Tackling Global Pandemics Through Scientific and Social Tools, 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-85844-1.00004-0

- Jensen, J. D. (2018). Employee motivation: A leadership imperative. International Journal of Business Administration, 9(2), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijba.v9n2p93

- Jensen, U. T., Andersen, L. B., Bro, L. L., Bøllingtoft, A., Eriksen, T. L. M., Holten, A. L., Jacobsen, C. B., Ladenburg, J., Nielsen, P. A., Salomonsen, H. H., Westergard-Nielsen, N., & Würtz, A. (2019). Conceptualizing and measuring transformational and transactional leadership. Administration & Society, 51(1), 3–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399716667157

- Joshi, A., Kale, S., Chandel, S., & Pal, D. K. (2015). Likert scale: Explored andexplained. British Journal of Applied Science & Technology, 7(4), 396. https://doi.org/10.9734/BJAST/2015/14975

- Kang, H. (2021). Sample size determination and power analysis using the G* power software. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 18, 17. https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2021.18.17

- Khan, H., Rehmat, M., Butt, T. H., Farooqi, S., & Asim, J. (2020). Impact of transformational leadership on work performance, burnout and social loafing: A mediation model. Future Business Journal, 6(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-020-00043-8

- Khan, S. A., & Varshney, D. (2013). Transformational leadership in the Saudi Arabian cultural context: Prospects and challenges. In J. Rajasekar & L.-S. Beh (Eds.), Culture and gender in leadership: Perspectives from the Middle East and Asia (pp. 200–227). Springer.

- Legault, L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences, 2416–2419. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_1139-1

- Lin, T. K., Werner, K., Witter, S., Alluhidan, M., Alghaith, T., Hamza, M. M., Herbst, C. H., & Alazemi, N. (2022). Individual performance-based incentives for health care workers in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and development member countries: A systematic literature review. Health Policy, 126(6), 512–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.03.016

- Litman, L., Robinson, J., & Rosenzweig, C. (2015). The relationship between motivation, monetary compensation, and data quality among US-and India-based workers on mechanical Turk. Behavior Research Methods, 47(2), 519–528. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-014-0483-x

- Liu, B., Huang, W., & Wang, L. (2019). Performance-based equity incentives, vesting restrictions, and corporate innovation. Nankai Business Review International, 10(1), 138–164. https://doi.org/10.1108/NBRI-10-2018-0061

- Mach, M., Ferreira, A. I., & Abrantes, A. C. (2022). Transformational leadership and team performance in sports teams: A conditional indirect model. Applied Psychology, 71(2), 662–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12342

- Madigan, D. J., & Kim, L. E. (2021). Towards an understanding of teacher attrition: A meta-analysis of burnout, job satisfaction, and teachers’ intentions to quit. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105, 103425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103425

- Magnus, M. (1981). Employee recognition: A key to motivation. Personnel Journal, 60(2), 103–107.

- Martin, E. (2006). Survey questionnaire construction. Survey Methodology, 13, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-12-369398-5/00433-3

- Masa’deh, R. E., Obeidat, B. Y., & Tarhini, A. (2016). A Jordanian empirical study of the associations among transformational leadership, transactional leadership, knowledge sharing, job performance, and firm performance: A structural equation modelling approach. Journal of Management Development, 35(5), 681–705. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-09-2015-0134

- Masi, R. J., & Cooke, R. A. (2000). Effects of transformational leadership on subordinate motivation, empowering norms, and organizational productivity. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 8(1), 16–47. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb028909

- Merino, M. D., & Privado, J. (2015). Does employee recognition affect positive psychological functioning and well-being? The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 18, E64. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2015.67

- Miao, C., Humphrey, R. H., & Qian, S. (2017). A meta-analysis of emotional intelligence effects on job satisfaction mediated by job resources, and a test of moderators. Personality and Individual Differences, 116, 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.031

- Miner, J. B. (2005). Organizational behavior: Essential theories of motivation and leadership 1. M.E. Sharpe.

- Montani, F., Boudrias, J. S., & Pigeon, M. (2020). Employee recognition, meaningfulness and behavioural involvement: Test of a moderated mediation model. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(3), 356–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1288153

- Nazir, T., Khan, S. U. R., Shah, S. F. H., & Zaman, K. (2013). Impact of rewards and compensation on job satisfaction: Public and private universities of UK. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 14(3), 394–403.

- Nguyen, T. H. (2020). Impact of leader-member relationship quality on job satisfaction, innovation and operational performance: A case in Vietnam. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics & Business, 7(6), 449–456. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no6.449

- Niskala, J., Kanste, O., Tomietto, M., Miettunen, J., Tuomikoski, A. M., Kyngäs, H., & Mikkonen, K. (2020). Interventions to improve nurses’ job satisfaction: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(7), 1498–1508. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14342

- Nurlina, N. (2022). Examining linkage between transactional leadership, organizational culture, commitment and compensation on work satisfaction and performance. Golden Ratio of Human Resource Management, 2(2), 108–122. https://doi.org/10.52970/grhrm.v2i2.182

- Nykodym, N., Simonetti, J. L., Nielsen, W. R., & Welling, B. (1994). Employee empowerment. Empowerment in Organizations, 2(3), 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1108/09684899410071699

- Olafsen, A. H., Halvari, H., Forest, J., & Deci, E. L. (2015). Show them the money? The role of pay, managerial need support, and justice in a self‐determination theory model of intrinsic work motivation. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 56(4), 447–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12211

- Ormel, H., Kok, M., Kane, S., Ahmed, R., Chikaphupha, K., Rashid, S. F., Gemechu, D., Otiso, L., Sidat, M., Theobald, S., Taegtmeyer, M., & de Koning, K. (2019). Salaried and voluntary community health workers: Exploring how incentives and expectation gaps influence motivation. Human Resources for Health, 17(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-019-0387-z

- Peterson, R. A., & Kim, Y. (2013). On the relationship between coefficient alpha and composite reliability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(1), 194. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030767

- Rai, A., Ghosh, P., Chauhan, R., & Singh, R. (2018). Improving in-role and extra-role performances with rewards and recognition: Does engagement mediate the process? Management Research Review, 41(8), 902–919. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-12-2016-0280

- Ruiz-Palomino, P., Hernández-Perlines, F., Jiménez-Estévez, P., & Gutiérrez-Broncano, S. (2019). CEO servant leadership and firm innovativeness in hotels: A multiple mediation model of encouragement of participation and employees’ voice. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(4), 1647–1665. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-01-2018-0023

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

- Saleem, H. (2015). The impact of leadership styles on job satisfaction and mediating role of perceived organizational politics. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 172, 563–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.403

- Samnani, A. K., & Singh, P. (2014). Performance-enhancing compensation practices and employee productivity: The role of workplace bullying. Human Resource Management Review, 24(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2013.08.013

- Sarros, J. C., & Santora, J. C. (2001). The transformational‐transactional leadership model in practice. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 22(8), 383–394. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730110410107

- Schwarz, G., Eva, N., & Newman, A. (2020). Can public leadership increase public service motivation and job performance? Public Administration Review, 80(4), 543–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13182