Abstract

The rapid growth of the digital economy in Indonesia provides a positive trend for startups. The valuation of Indonesia’s digital economy is the highest in Southeast Asia. This paper aims to identify problems and legal issues regarding startups. This research also tries to formulate regulations that can support the development of startups in Indonesia. The data collection technique used is library research by examining books, journals, reports, and laws related to startups. The data analysis technique used is the legal norm method by analyzing laws and regulations related to startups. Based on the results of the research, it was found that startups in Indonesia still face various legal problems such as the absence of startup regulations and the complicated and lengthy startup licensing process. Based on these problems, it is recommended that Indonesia has regulations that specifically regulate startups. The regulation regulates the process of facilitating business licensing for startups, financial support and capital raising schemes. To overcome these problems, Indonesia needs to reformed regulations in the startup sector and apply the licensing concept through a risk-based approach.

1. Introduction

Startups are project-based organizations or businesses operating in various industries that commercialize a novel business model by fusing cutting-edge concepts or cutting-edge technology to deal with unclear environments (Goswami et al., Citation2023). The term startups also may refer to newly started businesses, especially those with technology-based services or products (Kim et al., Citation2018). In short, startups include only those that work with information technology. Indonesia has been one of Southeast Asia’s most active startup markets. Additionally, it boasts one of the most active startup ecosystems in the world.

According to the Startup Ranking 2023, Indonesia is in 2nd place in Southeast Asia and 9th in Asia Pacific, above Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam. The largest market size in Southeast Asia and having a young generation, talented and internet-savvy workforce is the potential for startups in Indonesia to grow and develop (StartupBlink, Citation2023). E-commerce, transportation & food, and financial services are Indonesia’s most prevalent startup business sectors.

The market valuation of Indonesian unicorns and decacorns also dominates the startups in Southeast Asia. Indonesia now has two decacorn and nine unicorns: (1) Goto (Valuation: $40 billion); (2) J&T Express (Valuation: $20 billion); (3) Bukalapak (Valuation: $3.5 billion); (4) Traveloka (Valuation: $3 billion); (5) OVO (Valuation: $2.9 billion); (6) OnlinePajak (Valuation: $1.7 billion); (7) Xendit (Valuation: $1 billion); (8) Ajaib (Valuation: $1 billion); (9) Tiket.com Valuation: $1 billion; and (10) JD.ID (Valuation: $1 billion) (StartupBlink, Citation2023).

Eight startups from Indonesia have even made it to the Forbes Asia 100 to Watch list. Beau Bakery, Bobobox, Dekoruma, Otoklix, Evermos, Populix, Sampingan, and PrivyID (Forbes, Citation2021). Indonesian startups have also contributed a lot during the COVID-19 pandemic in Asia-Pacific. They have helped tackle transportation problems in congested cities, broaden the connectivity in remote areas, and prevent food wastage. Indonesia has the largest market in Southeast Asia. Due to its strategic location, Indonesia provides access to important markets such as Australia and the Philippines. Nevertheless, Indonesia faces several challenges due to its unpredictable political situation and extensive bureaucracy and regulation (StartupBlink, Citation2023).

In the Global Startup Ecosystem Index (GSEI) 2023, Indonesia is ranked 41th, with a score of 5,411. One factor contributing to this low position is the absence of policies and regulations supporting startups (StartupBlink, Citation2023). This might hamper the growth of startups in Indonesia. To combat this, the government should create a suitable legal infrastructure and support structures to allow startups and entrepreneurs to thrive. Legal infrastructure is critical to the success of companies (Francesc et al., Citation2023; Goswami et al., Citation2023). Precourt (Citation2019) discovered that the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act, or JOBS Act, positively impacted the growth of startups in the U.S. The JOBS Act is a bill intended to stimulate small business finance in the United States by loosening many of the country’s securities restrictions.

Similarly, the support of policies and regulations in India has positioned the nation as the world’s third largest startup ecosystem (Singh, Citation2020). In addition to protecting the founders’ interests of the company, the legislation provides a cushion for pursuing additional opportunities. Other studies (Parrino & Romeo, Citation2012; Trifu et al., Citation2015) suggested that regulations may bring either positive or negative impacts to startups. This paper aims to identify problems and legal issues regarding startups. This research also tries to formulate regulations that can support the development of startups in Indonesia to help entrepreneurs and startups flourish.

2. Literature review

2.1. Definition of startup

The term “startup” is more categorized for companies that run their businesses using information technology and the internet (Kim et al., Citation2018). Startup business is a company that has just been built or is in the pilot period, but does not apply to all categories of business fields (StartupBlink, Citation2023). A startup can be defined as a project-based organization or company in various business fields that commercializes a new business model by combining innovative ideas or advanced technologies to deal with uncertain environments (Eric, Citation2011). It is a new business model in establishing a business by maximizing technological facilities supported by careful planning, individual idealism, and unique business theme (Yudhanto, Citation2018). Startup company is a company that has just been pioneered and refers to company whose services or products are technology-based (Kim et al., Citation2018). It means, a startup is a company that uses information technology in its products. If it does not use elements of information technology, the business can be said to be a startup (Baskoro, Citation2013).

There are several factors that can influence the success of a startup. Ruiz-palomino & Martínez-Cañas identified the role of family and friends-based entrepreneurial social networks as a factor that influences startup success (Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, Citation2021). However, apart from that, the legal infrastructure factor is also a factor that also influences the running of the startup business (Francesc et al., Citation2023; Goswami et al., Citation2023).

The startup business sector can be divided into five areas with the largest market range, namely e-Commerce (Marketplaces, Malls Direct to Consumer), Transport & Food (Transport, Food Delivery), Online Media (Advertising, Gaming, Video on Demand, Music on Demand), Online Travel (Flights, Hotels, Vacation Rentals) and Financial Services (Payment, Remittance, Lending, Insurance, Investing). During the COVID-19 pandemic, new fields were added in line with community needs and technological developments, namely HealthTech and EdTech (Google, Temasek and Bain & Company, Citation2021).

2.2. The role of law in economic development

In economic development, several factors for law to play a role are whether the law is able to create stability, predictability and fairness (Theberge, Citation1980). Stability means that the law must be able to play a role in balancing and accommodating competing interests. Predictability means that the need for predictable laws is important for countries where most of the people enter into economic relations beyond the traditional social environment. The aspect of fairness means that the law must be able to provide equal treatment and standard patterns of government behavior, necessary to maintain market mechanisms and prevent excessive bureaucracy (Theberge, Citation1980).

Regulations play an important role in economic development. The better the law and regulatory conditions, the better investment in that country is considered (Wiwoho & Kharisma, Citation2021). The government’s role in creating an investment climate is necessary to overcome market failure or failure to achieve efficiency. To overcome this failure, the government intervened through law and regulation (Perry, Citation2002). In this case the law functions as a facilitator of business development (Cross, Citation2002). The rule of law is very important to regulate economic globalization so that it has positive benefits for the country (Francesc et al., Citation2023).

3. Research method

This research examines at the various regulations and laws that regulate startups, enterprises, and information technology in order to generate legal arguments about the issues at hand. This is a legal analysis using a statute approach and a conceptual approach. The legal approach is adopted by examining all laws and regulations pertinent to the studied legal issues (Marzuki, Citation2019).

This study’s data was gathered through a survey of the literature and observation of primary and secondary legal sources. The primary legal documents include the Information and Electronic Transactions Act, the Job Creation Act, the Trade Act, the Government policy on Trading Through Electronic Systems, and several laws governing Indonesian startup business activities (e-commerce, transportation & food, online media, online travel agents, and financial services). Meanwhile, secondary legal materials consist of journal articles, research findings, papers, and books on the legal implications of new businesses.

First, the data were analyzed with the statutory and comparative approaches, the results of which were then further explored with the conceptual approach. The data were then subjected to qualitative legal analysis, which involved legal reasoning, legal interpretation, and legal argumentation. Finally, the result would be a legal framework to construct a startup regulation.

The data analysis technique used is the legal norm method. The legal norm method is carried out by examining various regulations related to startups. It aims to identify the applicable law (das sein) and the law as it should be (das sollen). The findings obtained were processed using the interactive analysis model. An interactive model was used to do qualitative data analysis. In qualitative research, the analysis process occurs concurrently with the data collecting implementation phase (Mattew & Huberman, Citation1992). In the implementation of qualitative research, there are three major components that are interconnected and interact. The process is illustrated in Figure below.

Figure 1. Interactive model of analysis (Mattew & Huberman, Citation1992).

Material law used in the study, includes:

Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) Act of 2008 in Indonesia;

Information and Electronic Transactions Act of 2008 in Indonesia (2016 revision);

Job Creation Act of 2020 in Indonesia;

Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act (JOBS Act) of 2012 in United States;

Company Act of 2018 in China;

Foreign Investment Act of 2019 in China; and

The Italian Startup Act (ISA) of 2012 in Italy.

4. Result and discussion

4.1. Startup legal issues in Indonesia

The ranking of EoDB in Indonesia is still far behind compared to neighboring countries or other countries in the world as shown in Table . Based on EoDB ranking in 2020, Indonesia was ranked 73rd (seventy third), far below Malaysia which was ranked 12th (twelfth) and Thailand which was ranked 21st (twenty first). In terms of competitiveness based on the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) in 2019, Indonesia was ranked 50th (fiftieth) while Malaysia was ranked 27th (twenty seventh) and Thailand was ranked 40th (fortieth). Even in terms of digitalization, Indonesia’s Digital Business Competitiveness in 2019 was ranked 56th (fifty sixth) while Malaysia was ranked 26th (twenty sixth) (World Bank Group, Citation2020).

Table 1. EoDB ranking in 2019/2020

In detail, some of the problems and challenges faced by startup players in Indonesia are:

4.1.1. Over-regulated in startup licensing

Regulations regarding startups in Indonesia are still partially regulated in several Acts, such as Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) Act 2008 Information and Electronic Transactions Act 2008 as amended in 2016, and Job Creation Act 2020 (Kharisma, Citation2020; Kharisma & Hunaifa, Citation2022). Unlike the United States, which has the JOBS Act 2012, Italy with the ISA 2012, the Philippines with the Innovative Startup Act 2019, or Tunisia with the Tunisian Startup Act 2020, there is currently no Act in Indonesia that particularly regulates startups.

Regulations on startups in Indonesia are still scattered in many Acts. More than that, each has different rules about startup licenses, depending on the business category. For example, for financial service startups, there are 10 Acts, 8 Government Regulations, 2 Presidential Regulation, 1 Minister Regulation, and 7 Regulation of the Head of the Authority that regulates business licenses, as presented in Table .

Table 2. Regulations on Financial Services startup license

The complicated regulations make the license process even more complicated because it includes several ministries. Startup players, especially those in the financial technology sector, still face a lengthy license process (Muryanto et al., Citation2021). They must pass 13 ministries or government agencies before the license is issued. Besides, for a license of a Limited Liability Company (P.T.), they must have 14 documents of application.

Alternative text for chart image:

The chart consists of three main sections, each outlining the steps of the initiating license process. The first step is to take care of licensing startup legal entities. The second step is to take care of startup business licensing. Then the third step is to take care of special sector licensing.

Figure shows the license application process that Startup had to go. They have to go through three stages:

Startup Legal Entity Establishment License. This is the initial license for the establishment of a startup legal entity. The process starts with making a notary agreement between the founders until the license to establish a P.T. is published by the Ministry of Law and Human Rights.

Startup Business License. This process is a common license that a P.T. should have before starting a business. After completing this stage, applicants will receive documents such as Business Identification Number (NIB), Standard Certificate, and Taxpayer Identification Number (NPWP).

Special Sector License. This is a special license that a startup must have, depending on the type of business activity. Several relevant ministries or authorities must pass nine sector-specific licenses.

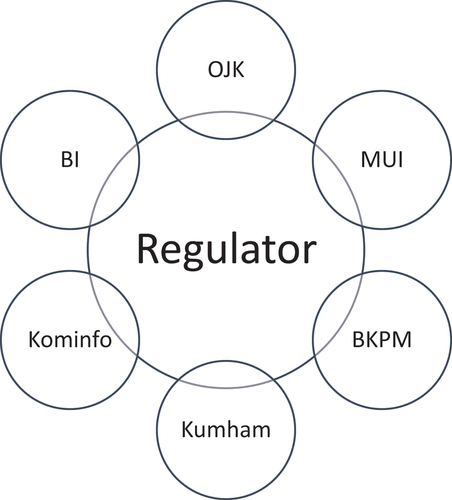

4.1.2. Over-regulators in the startup field

The regulation and supervision of startup businesses in Indonesia has unique characteristics. The startup business is under 10 authorities according to the type of business activity, namely the Ministry of Law and Human Rights (Kumham), Ministry of Communication and Information Technology (Kominfo), Ministry of Trade, Investment and Coordinating Board (BKPM), Ministry of Transportation, Ministry of Health, Food and Drug Supervisory Agency (Badan Pengawas Obat dan Makanan/BPOM), Financial Services Authority (Otoritas Jasa Keuangan/OJK), Bank Indonesia (BI), and the Indonesian Ulema Council (Majelis Ulama Indonesia/MUI).

For example, the startup is engaged in the Islamic FinTech sector. The regulation and supervision are under six authorities as shown in Figure .

Alternative text for chart image:

There are several startup regulators. For example, a startup operating in the Islamic fintech business sector. There are 6 regulators, including: BI, OJK, Kominfo, Kumham, BKPM, and MUI. The regulator is tasked with regulating, supervising, and granting business licenses.

The various problems faced by startup actors are an indication that the Indonesian Government’s vision to encourage startup growth is still weak. This can be seen by the absence of a national startup strategy for Indonesia that functions as a roadmap and guideline for the government, private sector, academics and the public in empowering startups. In fact, there is no government institution specifically responsible for empowering startups. This condition certainly has a negative impact on startup empowerment because there are no institutions or commissions that provide facilitation and incentives for startup actors.

4.2. Legal strategies to overcome startup issues

4.2.1. Reformed regulations in the startup sector

Regulatory reform is a strong stimulus for innovation. Government regulations can have both positive and negative impacts on the process of innovation and competitiveness (Cho et al., Citation2020). The pressure point of regulatory reform is carried out to provide a positive impact on innovation and competitiveness. Regulatory reform is expected to help ensure that laws and regulations in all areas of activity are fully responsive to the changing economic, social and technological conditions surrounding them. The regulatory process takes into account the impact of regulations relating to innovation as well as the implications of technological change for the rationale and design of regulations. Regulations and regulatory reforms can affect technology as well as innovation processes (OECD, nd). Public policy is an important element to encourage startup growth. Public policy is an important element to encourage startup growth. Therefore, it is important to design policies and regulations (Martínez-Cañas et al., Citation2023).

There are three general types of regulation, all of which affect innovation. First, economic regulation, is intended to ensure market efficiency, in part through the promotion of adequate competitiveness among business actors. In economic regulation, reform can mean market deregulation, privatization, or opening to increase competition. Second, social regulation, is intended to promote the internalization of all relevant costs by actors. In terms of social regulation, reform generally means increasing the cost flexibility and effectiveness of regulation. Third, administrative regulation, aims to ensure the function of public and private sector operations. In administrative regulation, reform is usually directed at streamlining and increasing regulatory efficiency. In some cases, regulatory reform can be an increase rather than a decrease of regulation level or government supervision (OECD, nd).

In the context of startup, America carried out regulatory reform in 2012 through the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act. The JOBS Act aims to create the EoDB and eliminate various provisions that hinder investment, especially for startup companies (Parrino & Romeo, Citation2012). It was proven in 2012, there were 6,000 such startups contributing to the local and national economy by ways of creating jobs, new products and, moreover, better opportunities. It means that regulations in the startup sector have an important role not only becoming a regulatory ecosystem but also protecting startup actors and providing a cushion to explore further opportunities (Pattnaik & Pandey, Citation2017).

Indonesia as a country that requires investment to finance its development must fix the time, the procedures, and the funding of business establishment, especially through its policies and regulations. The length or difficulty of the startup licensing process has implications for Indonesia’s low competitiveness compared to neighboring countries. One of the complexities or difficulties of investing can be seen from the licensing process.

Regulatory reform in the licensing sector can be a government strategy in order to encourage digital economic growth through the increase of investment. The reform that needs to be carried out is aimed at solving investment barriers, namely over-regulation in the field of startup licensing, the length of the licensing process, and the large number of regulators who regulate and supervise. According to Anthony Allot in his theory of the effectiveness of law, one of the regulatory functions is a facilitative function, to facilitate the needs of legal subjects to take legal actions (Allot, Citation1981).

Structuring the regulations in the startup licensing field will create ease of doing business and increase qualified investment in Indonesia. With qualified and effective investment, it is hoped that the value of the Incremental Capital-Output Ratio (ICOR) will decrease to 6.2 (six point two) in 2024. Furthermore, investment allocation needs to be directed to focus more on the digital economy sector and encourage downstreaming to increase value-added. By creating EoDB for startups, it will create jobs that are able to absorb many job seekers. It is not only in terms of quantity but also quality, which creates jobs with high productivity which will have an impact on continuous wage increases.

As what happens in the U.S. and Italy, a specific Act is crucial to the success of developing the startup ecosystem (Precourt, Citation2019; Yu et al., Citation2019). The success of the startup is influenced by the support of the Act (Francesc et al., Citation2023; Goswami et al., Citation2023). The JOBS Act 2012 has successfully created ease of business and eliminated various provisions that hinder investment, especially for startup companies (Parrino & Romeo, Citation2012). The JOBS Act was enacted in 2012, and more than 6,000 startups have contributed to the local and national economies by producing jobs, new goods, and better possibilities. The Startup Act serves not only as a regulatory ecosystem but also as a cushion for exploring additional options (Pattnaik & Pandey, Citation2017)

Indonesia must create a Startup Act as a legal infrastructure of a startup ecosystem and a roadmap to provide ease of business and facilitate startups (Wiwoho et al., Citation2022). The Startup Act will eliminate regulations and simplify the lengthy license application process (Parrino & Romeo, Citation2012). The existence of regulations that regulate startups can also protect investors from fraud in startups (Gleason et al., Citation2022).

Here are some legal constructs that the Startup Act in Indonesia should cover:

startup convenience, protection, and empowerment;

provision of startup infrastructure;

startup incubation;

establishment of the National Startup Commission;

startup partnerships;

sources of capital and financial support; and

market access

4.2.2. Licensing concept through a risk-based approach

In the startup business sector recently, Indonesian government uses the concept of a license approach. With this concept, the Government places licensing as a form of obligation that must be fulfilled by business actors to be able to carry out business activities legally. Business actors are faced with so many numbers or types of required business licenses that they burden business activities and result in ineffective and inefficient business processes.

The government uses regulation as a control over all risks that have an impact on the economy, society, and environment. The regulatory system is spread out and applies to various business activities, so it affects almost all aspects of business activities. This condition burdens business actors because there is duplication of requirements and licenses in various Ministries and Government Agencies which causes the increase of costs and the difficulty in starting a business.

To overcome these problems, the government can change the concept of the license approach to a risk-based approach in startup licensing. The risk-based approach is an approach where the level of risk becomes a consideration for every action or effort taken. The higher the potential risk caused by a particular business activity, the tighter the control from the government, and the more licenses or inspections required. As for low-risk activities, licenses and inspections are generally not required.

The right methodology or tool is needed to be able to classify the risks of each business or activity through a risk matrix. The risk matrix is the fundamental instrument used to classify the establishment depending on the level of business risk and to adapt them to regulatory responses (e.g are strictly required inspections and licenses). It is intended that the resources owned can be used more effectively and efficiently, and the burden of government administration can be minimized.

Table is an example of a matrix with risk-based approach in the United Kingdom (UK) (Office BRD, n.d.; World Bank Group, Citation2019):

Table 3. Risk approach matrix in UK likelihood of Compliance

In this matrix, the level of “hazard” is equivalent to “amount of damage.” In the UK, the possibility of compliance is used more than the possibility of a violation or adverse event. The factors that can cause risk in the matrix in the table above are generally described in the following aspects:

The type of activity (some types of activity are factually more dangerous than others, because they are more likely to occur; Also, some can cause very severe damage, meaning that the seriousness of the impact is higher) affecting the amount of the damage and probability;

The size of the establishment (a larger establishment will have a proportionally higher negative effect in the event of an accident) affecting its amount of the damage;

Location of establishment (isolation will have a negative effect on the environment; proximity to sensitive natural resources or to densely populated areas will increase risk) affecting the amount of the damage;

History (frequent or repeated offences, or vice versa is the “establishment model,” in the first case that accidents are more likely and vice versa) influencing probability.

The risk matrix is a fundamental instrument used to classify company establishments depending on the level of business risk to be carried out and relate it to regulatory responses (i.e. licenses that are really needed and inspections that must be carried out). It is intended that the resources owned can be used more effectively and efficiently, and the burden of government administration can be minimized.

The government can control all risks that occur in the startup business by applying standard implementation setting for conducting startup business activities. Using the standards, it will be possible to identify the possibility/probability of the occurrence of risks from startup business activities. By using the concept of applying risk-based standards/approach, the government can determine the types of licenses that must be owned by a business activity and the quality and quantity of inspections that must be carried out in the context of monitoring the implementation of business activities.

By implementing risk-based regulations as a reference for determining the type of business licensing accompanied by the implementation of inspections for effective control, it will simplify the business licensing mechanism and will ultimately provide economic, social, and environmental benefits. However, a strong commitment from the government is required for the implementation and enforcement of these regulations.

5. Conclusion and recommendation

Indonesia has a huge digital economy potential. This potential can be seen in the valuation of Indonesia’s digital economy, which is the largest in the Southeast Asia region. However, startup actors as key actors in the development of the digital economy face various challenges, such as being over-regulated in the startup licensing sector, a complicated and lengthy startup licensing process, and over-regulators in the startup sector. To overcome these problems, holistic strategies that can be carried out include the regulatory reform in the field of startup licensing and the application of the licensing concept through a risk-based approach. Apart from licensing matters, government regulations must also accommodate factors that can foster entrepreneurship, such as entrepreneurial education and training and building entrepreneurial social networks. Furthermore, further research is needed that discusses the causes of startup business failure from a legal perspective and how the role of the National Commission of Startups should be in overcoming this.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Acep Rohendi

Acep Rohendi is an Academic Vice Rector at Universitas Adhirajasa Reswara Sanjaya (ARS University) Indonesia. He is also a lecturer at Magister Management Postgraduate Program, Faculty of Economic, ARS University. The author has been focused with Law, Business & Management, and Banking Law lecture. In the last three years, the author has been concerned with Banking Law, and he has been successfully published in international journals, such as: (1) Reporting Obligation of Credit Card Transaction :Perspective of Bank Secrecy and The Government Regulation in Lieu of Law No 1/2017 on the Access to Information for Taxation Purposes; 2) Consumer Protection in the E- Commerce: Indonesian Law and International law Perspective; 3) Islamic-Based Political Party Branding in the 2019 of Legislative Election; 4) Implications of GATS principles in the Liberalization of Foreign Investment: A Case of Current Indonesian Banking Law; 5) Liberalization Policy of Foreign Investment in Indonesian Banking: A Juridical Review. The author is also a member of deputy chairman of lecturer association West Java area.

Asriani Asriani

Asriani, Asriani, M.H is a Head of Research Center in The Departement of Research Institutes an Community Service, in Raden Intan State Islamic University Lampung. She is also a lecturer at Magister Management Postgraduate Program, in Business of Law, and Islamic Law of The Engagements, in Faculty of Economic and Islamic Business, and also lecturer at Degree Program in Pancasila and Civic Education of Raden Intan State Islamic University Lampung. In the last ten years the author has been concerned with Business of Law and five years in Islamic Law of The Engagements and she has been successfully published in international journals such as : (1) Sharia Economic Dispute Revolution During COVID-19 Pandemic In 2021, can be accessed http://ejournal.radenintan.ac.id; (2) The Role of Indonesia Islamic Bank In Improving Economics Growth In Indonesia on The Analysis of Opportunities and Obstacles of Islamic Banks Post Mergen, in 2022; (3) Islamic Gold Investment In the Perspective of Islamic Law in, 2015; (4) Perspective of Islamic Law and positive Law on Gold Pawning in Financial Institutions, 2016; (5) Perceptions of Domestic Violence in Religious Courts and District Courts in Relation to Divorce Litigation; (6) Juridical Analysis of The Legal Protection of the Position of Extra-Marital Children in Inheritance Relations According to Law no.1 of 1974 Concerning Marriage, Law no.23 of 2002 Concerning Child Protection. The author is also a member organization of Association of Indonesia Doctor of Law.

Dona Budi Kharisma

Dona Budi Kharisma is a lecturer in the Department of Private Law, Faculty of Law, Universitas Sebelas Maret Indonesia. In the last three years the author has been concerned with digital economic law. Several research titles that have been successfully published in international journals include: (1) Comparative study of personal data protection regulations in Indonesia, Hong Kong and Malaysia; (2) Prospects and challenges of Islamic FinTech in Indonesia: a legal viewpoint; (3) Comparative study of disgorgement and disgorgement of fund regulations in Indonesia, the USA and the UK; (4) Urgency of financial technology (FinTech) laws in Indonesia. The author is a member of the Private Law Teacher Association (APHK), the Intellectual Property Law Teacher Association (APHKI), and founder of Mahuta (Society of Private Law) Indonesia.

References

- Allot, A. (1981). The effectiveness of laws. Symposium on International Perspectives of Jurisprudence, 15(2), 229–12.

- Baskoro, L. (2013). It’s my startup. Metagraf.

- Cho, K., Hyun, S., Lee, H., & Oh, Y. (2020). China’s startup ecosystem policy and implications. World Economy Brief, 10(17), 1–4. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3889160.

- Cross, F. B. (2002). Law and economic growth. Texas Law Review, 80(7), 1737–1775.

- Eric, R. (2011). The lean startup: How Today’s entrepreneurs use continuous innovation to create radically successful businesses. Crown Books.

- Forbes. (2021). Forbes Asia 100 to watch, accessed from https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesasiateam/2021/08/09/forbes-asia-100-to-watch/?sh=52d31eb23752 28 December. 2021.

- Francesc, F., Lara-Navarra, P., & Serradell-Lopez, E. (2023). Digital transformation policies to develop an effective startup ecosystem: The case of Barcelona. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy, 17(3) 344–355. https://doi.org/10.1108/TG-01-2023-0006

- Gleason, K., Kannan, Y. H., & Rauch, C. (2022). Fraud in startups: What stakeholders need to know. Journal of Financial Crime, 29(4), 1191–1221. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-12-2021-0264

- Google, Temasek and Bain & Company. (2021). e-Conomy SEA 2021 Report.

- Goswami, N., Murti, A. B., & Dwivedi, R. (2023). Why do Indian startups fail? A narrative analysis of key business stakeholders. Indian Growth and Development Review, 16(2), 141–157. October 2021. https://doi.org/10.1108/IGDR-11-2022-0136

- Kharisma, D. B. (2020). Urgency of financial technology (fintech) laws in Indonesia. International Journal of Law and Management, 63(3), 320–331. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLMA-08-2020-0233

- Kharisma, D. B., & Hunaifa, A. (2022). Comparative study of disgorgement and disgorgement fund regulations in Indonesia, the USA and the U.K. Journal of Financial Crime, 30(3), 635–649. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-01-2022-0022

- Kim, B., Kim, H., & Jeon, Y. (2018). Critical success factors of a design startup business. Sustainability, 10(9), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10092981

- Martínez-Cañas, R., Ruiz-Palomino, P., Jiménez-Moreno, J. J., & Linuesa-Langreo, J. (2023). Push versus pull motivations in entrepreneurial intention: The mediating effect of perceived risk and opportunity recognition. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 29(2), 100214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2023.100214

- Marzuki, P. M. (2019). Penelitian Hukum (Cetakan Ke-14). Prenada Media Group.

- Mattew, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1992). Translated by: Tjepjep Rohendi Rohidi. Analisis Data Kualitatif: Qualitative data analysis. UI Press.

- Muryanto, Y. T., Kharisma, D. B., & Ciptorukmi Nugraheni, A. S. (2021). Prospects and challenges of Islamic fintech in Indonesia: A legal viewpoint. International Journal of Law and Management, 64(2), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLMA-07-2021-0162

- Parrino, R. J., & Romeo, P. J. (2012). JOBS Act eases securities‐law regulation of smaller companies. Journal of Investment Compliance, 13(3), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/15285811211266083

- Pattnaik, P. N., & Pandey, S. C. (2017). University startups and special legislations: Genesis and developments in the United States of America, Japan and India. International Journal of Law and Management, 59(5), 718–728. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLMA-05-2016-0046

- Perry, A. J. (2002). The relationship between legal Systems and economic development: Integrating economic and cultural approaches. Journal of Law and Society, 29(2), 282–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6478.00219

- Precourt, E. (2019). The effect of the JOBS act on analyst coverage of emerging growth companies. Journal of Financial Regulation & Compliance, 27(1), 86–109. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRC-10-2017-0082

- Ruiz-Palomino, P., & Martínez-Cañas, R. (2021, September). From opportunity recognition to the start-up phase: The moderating role of family and friends-based entrepreneurial social networks. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, Springer, 17(3), 1159–1182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00734-2

- Singh, V. K. (2020). Policy and regulatory changes for a successful startup revolution: Experiences from the startup action plan in India. ADBI Working Paper Series. Asian Development Bank Institute. 1146.s

- StartupBlink. (2023). Global startup ecosystem index 2023 (Report No. 1–333).

- Theberge, L. J. (1980). Law and economic development. Denver Journal of International Law and Policy, 9(2), 231–238.

- Trifu, A. E., Girneata, A., & Potcovaru, A. M. (2015). The impact of regulations upon the startup of new businesses. Economia: Seria Management, 18(1), 49–59. http://www.management.ase.ro/reveconomia/eng/index.htm%0Ahttps://liverpool.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ecn&AN=1611913&site=eds-live&scope=site

- Wiwoho, J., & Kharisma, D. B. (2021). Isu-Isu Hukum di Sektor Fintech. Setara Press.

- Wiwoho, J., Kharisma, D. B., & Wardhono, D. T. K. (2022). Financial crime in digital payments. Journal of Central Banking Law and Institutions, 1(1), 47–70. https://doi.org/10.21098/jcli.v1i1.7

- World Bank Group. (2019). Introducing a risk-based approach to regulate businesses: How to build a risk matrix to classify enterprises or activities. 1–8. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/investment-climate/brief/business-environment

- World Bank Group. (2020). Ease of doing business rankings. Accessed from https://archive.doingbusiness.org/en/rankingson9

- Yudhanto, Y. (2018). Information technology business Start-Up: Ilmu Dasar Merintis Start-Up Berbasis Teknologi Informasi. Elex Media Komputindo.

- Yu, J., Rezaee, Z., & Zhang, J. H. (2019). The accounting and market consequences of the JOBS Act of 2012: An early study. Asian Review of Accounting, 27(1), 49–68. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARA-02-2017-0033