?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

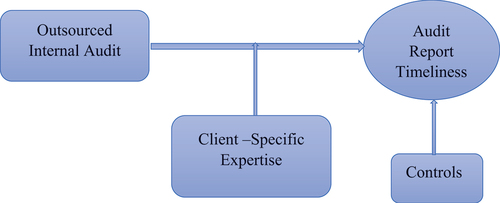

Motivated by the increasing interest of auditing regulators, organizations, and researchers in outsourced internal audit function (OIAF), this paper examines how outsourced IAF provider is connected with timely audit reporting, and particularly explores the moderating influence of client-specific expertise on the relationship between outsourced IAF provider and audit report timeliness. A sample of Omani-listed firms over the period 2013–2019 and pooled regression analysis with robust standard errors are utilized. The findings reveal that the external IAF provider is slightly related to reduced delay in the audit report. In particular, the reduction is more pronounced when the external IAF provider has client-specific expertise and increases audit timeliness. These results are robust after conducting a sensitivity analysis. This paper presents the importance of outsourced IAF providers, particularly those with clients’ expertise, in supporting the best practices of external audits and timely reporting.

Public Interest Statement

An internal audit function is a powerful instrument for supporting the internal control system and assisting the external auditor in minimizing audit effort and time. This study extends the recent stream of outsourced IAF literature. It also provides empirical evidence of the positive effect of external IAF providers with clients’ expertise in improving timely audit reporting in an emerging economy. Timely reporting mitigates the information asymmetry problem and supports the value and usefulness of information for decision-makers.

1. Introduction

Since the series of financial scandals have occurred in the past few years. Thus, regulators and stakeholders promoted the pivotal role of the internal audit function (IAF) in detecting fraud and wrongdoing and promoting internal control effectiveness (Khelil, Citation2023; Khelil & Khlif, Citation2022). Such as, external auditors are encouraged to utilize internal auditors’ work to test internal control and financial reporting for a company by the regulatory authorities of audit standards, i.e., the International Federation of Accountants (IFA), International Standard on Auditing (ISA) 610), and also section 404 in the Sarbanes—Oxley Act 2002 (SOX) lingering the IAF work for public companies in the USA. Accordingly, many authorities of capital markets requested listed firms to set up an IAF like the New York Stock Exchange in 2006, the Omani Capital Market Authority (CMA) (Citation2002), and the Malaysian Securities Commission in 2008. Other instances of IAF setting up involve Taiwan, Thailand, and China. Nevertheless, these states authorize only a third party of a company to supply IAF. Given the modern tendency for the majority of regulatory authorities around the globe that require public companies to set up an IAF, companies overall favor outsourcing this function to a third party to execute an effective function and efficient cost (Baatwah et al., Citation2021; Mubako, Citation2019). Globally, a survey in 2015 by the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) exhibited that 38% of respondents recognized outsourcing IAF to a third party, and 88% of respondents predicted to rise or even preserve the same ratio in the coming five years (Barr-Pulliam, Citation2016). Therefore, this study concentrates on that issue and delivers empirical evidence about how outsourced IAF providers influence timely audit reporting. It also investigates whether the client-specific expertise of an outsourced IAF provider is linked with reducing the delay in external audit reporting.

Delayed audit reporting significantly affects the timing of financial reporting release (Chen et al., Citation2022; Durand, Citation2019), and the deferred issue of financial reporting is related to raising asymmetric information in the market and uncertainty in investment decisions (Bamber et al., Citation1993; Chen et al., Citation2022). Hence, accounting information loses its value in making decisions (Harjoto & Laksmana, Citation2022). Therefore, some bodies of accounting standards like Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) (2002) requested to publish the related information for users in the speediest time before it lost its capability to influence the decision. This in turn has exacerbated the pressure on companies and external auditors to promptly audit financial information (Durand, Citation2019; Oussii & Taktak, Citation2018). This pressure, therefore, pushed to increase the significance of looking for techniques to decrease the delay in audits and increase audit efficiency (Harjoto & Laksmana, Citation2022)

Several setters of auditing standards and norms (such as IFAC, IIA, and Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) have thus suggested methods to achieve this strategy, including the internal auditor task. For instance, the PCAOB (2010) Auditing Standard No. 5 permits external auditors to rely on assignments executed autonomously by internal auditors to identify audit ranges, as long as the IAF has acceptable quality. Academic researchers further indicated that the audit timeliness reflects the efforts of both external and internal auditors as the work achieved by the IAF assists the external auditor in minimizing the effort needed to finalize audits (Abbott et al., Citation2012; Pizzini et al., Citation2015; Wan-Hussin & Bamahros, Citation2013). Hence, an efficient IAF is expected to shorten the delay in external audits. It is worth noting that the body of research on the evaluation of external auditors for IAF quality describes the greatest developed studies area and the most established subject in the literature of auditing research (Behrend & Eulerich, Citation2019; Khelil, Citation2023). However, a thorough understanding of the positive effect of the IAF on external auditing outcomes is not yet attained as practical evidence regarding this scant subject (Baatwah et al., Citation2019; Behrend & Eulerich, Citation2019; Khelil, Citation2023).

The motivation behind this study is therefore as follows. First, it has been a trend for activities of outsourced IAF providers in recent years (e.g., Baatwah et al., Citation2019, Citation2021; Mubako, Citation2019) because of the features provided by this trend such as cost savings, and strengthening IAF objectivity (Ahlawat & Lowe, Citation2004; Glover et al., Citation2008; Mubako, Citation2019). There is little research on this subject, which may be due to the shortage of data for outsourced IAF in the majority of countries, or the lack of requirements imposed on companies to report data about IAF. From these few studies, Baatwah et al. (Citation2021), Baatwah et al. (Citation2019), and Prawitt et al. (Citation2012) are the only studies that deliver insight into this topic. Prawitt et al. (Citation2012) used data from US firms and pre-SOX since external auditors were permitted to deliver the IAF practice for their clients. These scholars indicate that outsourced IAF is a more relevant mechanism for reducing fraudulent risks in financial reporting. Outsourced IAF providers can detect and deter earnings management practices more efficiently than internal IAF providers since they share bigger objectivity, independence, and expertise (Baatwah et al., Citation2021; James, Citation2003), and can deliver internal audits with high quality, supporting the efficiency of external auditors in issuing audit reports in early time (Baatwah et al., Citation2022; Gros et al., Citation2017). These scholars call upon to investigate further research on how outsourced IAF provider affects the decision and efforts of the external auditor and the quality of financial reporting. Thus, this study extends this stream of research and posits that outsourced IAF providers can reduce the delays in external audit reporting by using data from an emerging market. While, the profession of internal auditing is still embryonic with unregulated tasks (Khelil & Khlif, Citation2022).

Second and significantly, the quality of IAF can be also enhanced if external IAF providers have certain expertise for a client’s business. This expertise or knowledge is acquired from ongoing commitment with a certain client for a long time, giving the external IAF provider an in-depth perception of a client’s accounting systems, business risk, and internal control systems and assisting him/her in developing firm-related audit procedures. Also, this expertise will enhance their ability to assess and observe the sufficiency and effectiveness of internal controls on reporting, compliance, and other a company’s operations. Accordingly, outsourced IAF providers carrying client-specific information would pay more care to detect fraud and opportunistic practices and report these activities to an auditing committee and external auditors, which will assist the external auditor in reducing audit efforts in turn. Previous research confirmed that external IAF providers deliver services with high quality and guarantee the quality of accounting statements since they hold a greater degree of expertise concerning specialist knowledge such as client business (Baatwah et al., Citation2021; Caplan & Kirschenheiter, Citation2000). Outside IAF providers with strong expertise concerning their clients-specific information are associated with high-quality earnings and low business risks. This expertise supports their monitoring functions (Baatwah et al., Citation2021). This view assumes that external IAF providers depict the quality of accounting information and internal controls effectiveness for external auditors. Auditors thus can rely on external IAF providers and minimize the evaluation of risk and required tests, time, and effort. Concerning the main research objective; to the best of our knowledge, Baatwah et al. (Citation2021) and Baatwah et al. (Citation2022) are the only studies that provide a vision of outsourced IAF providers’ client-specific expertise. They revealed that the outsourced IAF provider’s expertise in the client’s business enhances the effectiveness of internal controls and greatly reduces the real earnings management and issuance audit reports in early time. Thus, this research seeks to extend the literature of client-specific expertise for outsourced IAF providers and also follows Baatwah’s et al. (Citation2022) study by exploring the interaction influence between outsourced IAF providers and client-specific expertise on the timely audit reporting, which supposes that external IAF providers with client-specific expertise can curtail the time and work of audit. The external IAF possesses the ability to support internal control mechanisms effectively and discovers and reports opportunistic activities, decreasing audit risks and efforts, and hence producing audit reports promptly. Therefore, the question posed by this research is: “What is the effect of interaction between client-specific expertise and outsourced IAF providers on audit report timeliness?”

Finally, the Gulf Cooperation Countries (GCC), specifically Oman, have witnessed significant reforms concerning IAF. For instance, the CMA in Oman requires the listed companies, which should establish an internal audit department (CMA, Citation2002). Nevertheless, this environment has a deficiency in skilled staff that requires expertise (Baatwah et al., Citation2019) and difficulties in maintaining the objectivity of IAF (Al-Akra et al., Citation2016). Consequently, firms are stimulated to outsource the activities of IAF to rid of these limitations (PWC, 2016), particularly those who have the expertise to support the audit committee’s effectiveness in checking the eminence of financial reports by enhancing internal control systems (Baatwah et al., Citation2021; Dang & Nguyen, Citation2022). Despite the IA practices recently having evolved and attracted many stakeholders in emerging markets such as GCC, further empirical evidence is still needed (Al-Akra et al., Citation2016; Baatwah et al., Citation2022; Khelil, Citation2023). Furthermore, some studies have shown some parts of IAF such as Leung et al. (Citation2009) in China and Taiwan, Mat Zain et al. (Citation2015) and Abdullah et al. (Citation2018) in Malaysia, Alzeban and Gwilliam (Citation2014) in Saudi Arabia, and Al‐Sukker et al. (Citation2018) in Jordan. Nevertheless, in these economies, outsourced IAF is the prevalent activity. However, the evidence from these studies relies on the IAF’s traditional structure, which is “in-house”. Thus, this paper narrows this gap and extends our understanding of the existing IAF mechanism in an emerging economy like Oman.

The main contributions of this research to the literature on IAF and audit timeliness are as follows. First, this research sheds light on the activities of external IAF providers, which have only received very limited attention so far. Thus this study advances and extends the literature that examines the practices of external IAF providers. Literature analyzes how the outsourced IAF providers affect timely reporting, which is proxied by external audit timeliness (Baatwah et al., Citation2019, Citation2021, Citation2022; Prawitt et al., Citation2012). Secondly, unlike other research that concentrated on the client-specific expertise of external auditors (e.g., Chen et al., Citation2022; Raweh et al., Citation2021; Wan-Hussin et al., Citation2018), this study is the first to take into consideration the moderating effect of client-specific expertise on the relationship between external IAF and timely audit reporting. Thus, this study provides novel contributions to the literature at the level of IAF as this expertise type boosts timely reporting. Third, this research acknowledges the role of familiarity with a client’s businesses in enhancing the quality of external IAF providers and its positive reflection on the efficiency of auditors to improve the timeliness of audit reports by decreasing audit delay. Timely reporting is considered the cornerstone of investors’ decisions and is necessary for healthy economic markets (Oussii & Taktak, Citation2018). Therefore, there is a decisive need to consider this context for designing future studies. The research’s findings benefit the investors, decision-makers in companies, and regulatory authorities in reassessing the quality of IAF and executing strategies to outsource for IAF.

The remainder of the study proceeds as follows. Section two presents the background, the literature review, and hypothesis development. The research design and findings are presented and discussed in Section Third, followed by the conclusion of this paper in Section Four.

2. Institutional background

The Omani regulations structure has experienced significant development. For example, the CMA issued a code of corporate governance (CG) in 2002, and all listed companies were requested to implement articles of the CG code. This code covers the compositions, functions, and relationships amongst the board of directors, audit committee, external auditors, internal auditors, management, and stakeholders. This is the first code in the Arab region and emerging economies. All listed firms and their external auditors should prepare their audited financial annual reports with international standards for example IFRS and IAS. Companies also are required to release their annual reports within two months to the public. Regulations of the Omani Capital Market further forbid external auditors from supplying non-audit services (such as IAF). Thus, they should be rotated after four consecutive years. In addition, the CMA declared that all firms established with five million and above Omani Riyal should set up a department for an internal audit task, as well as they can outsource this assignment to a third party (CMA, Citation2002). Several of the Omani regulations related to external and internal audits are similar to those in more developed economies such as the USA and the UK, which are more advanced than those of some developing markets (Baatwah et al., Citation2019; Raweh et al., Citation2021). Oman has a lack of empirical studies about the role of the internal audit function in diverse proxies of financial and audit quality.

3. Theoretical literature review

From the perspective of monitoring, and reducing agency costs the IAF is established to observe the extent of sufficiency and effectiveness of internal controls (Adams, Citation1994; Carey et al., Citation2000). Due to the separation between principals and agents in current business, the agents can arrive and employ information to their private interest, which creates asymmetric information between principals and agents, and exploit the opportunity to act against the principals’ interests, leading to conflicting interests between the agent and the principal (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). To align this conflict, establishing a control mechanism is needed. The main role of IA is to design systems to protect the assets of the organization and control cash flows to keep the accounting systems accurate and honest. IAF, therefore, is an internal monitoring device that ensures the financial integrity of a company and restricts financial shenanigans such as embezzlement, and nepotism in contracts (Anderson et al., Citation1993; Fadzil et al., Citation2005). Thereby, it manages the relationship of the contract between managers (agents) and owners (principals) and assists owners in tackling the asymmetric information problem and efficiently observing the practices of managers (Adams, Citation1994; Fadzil et al., Citation2005). In line with this viewpoint, the IIA (2005) suggests that IAFs advise examining and reviewing practices, policies, activities, and processes of financial reporting and disclosure. The IAF plays a vital role in monitoring the process of financial reporting direct or indirect (Abbott et al., Citation2016; Baatwah et al., Citation2021; Chen et al., Citation2017). Some emerging countries, therefore, prefer to use IAF as an oversee mechanism over other practices or mechanisms of corporate governance (Beisland et al., Citation2015). Agency theory argues that both internal and external auditors are control devices to deter accounting irregularities and any fraudulent in financial reporting (Arnold & Wilner, Citation1990; Beasley et al., Citation2000) and show that risk management operation and internal control systems work appropriately (Dang & Nguyen, Citation2021)). IAF is a powerful instrument for alleviating the agency problem by supporting internal control quality (Adams, Citation1994; Caplan & Kirschenheiter, Citation2000; Mat Zain et al., Citation2015) and the quality of internal control enhances the quality of accounting information, and timely disclosure by shorten lag of audit report (Bajra & Cadez, Citation2018; Gontara et al., Citation2023), which mitigates information asymmetry and agency conflict (Gontara et al., Citation2023). In the same line, it is reported that IAFs with experience are more attuned to an entity’s culture, sources of information, and series of leadership (Abbott et al., Citation2007). Experienced internal auditors thus reinforce the function of audits and effectively curb the practices of managerial opportunism, leading to the minimization of agency problems (Adams, Citation1994; Baatwah et al., Citation2021).

4. Empirical literature and hypothesis development

4.1 Outsourced IAF providers

Recently, outsourcing IAF has become the main source for internal audit services requirements for many companies globally (Baatwah et al., Citation2021; Barr-Pulliam, Citation2016; Mubako, Citation2019). Outsourced IAF signifies engaging a third party to perform IA activity in risk assessment, compliance with regulations, and a guarantee of internal controls, which is supplied by accounting firms that perform all or part of IA services (Caplan & Kirschenheiter, Citation2000; Selim & Yiannakas, Citation2000). Nevertheless, there are arguments for the merits and demerits of outsourcing the IAF (Mubako, Citation2019). On the one hand, it is claimed that the choice of outsourced IAF is more significant than in-house IAF since a third party gives an efficient service in terms of cost. Outsourced IAF further allows clients to hold a more experienced and skilled provider as well as achieve effective internal audits and retrieve losses if there is an audit failure (e.g., Carey et al., Citation2006; James, Citation2003; Rittenberg & Covaleski, Citation2001). And, outsourced internal auditors have less incentive to satisfy or align with management while the in-house internal auditor is more likely to be exposed and give in to management pressures (Desai et al., Citation2011). Conversely, the rivals argue that an outsourced IAF provider is not healthier than an in-house internal audit provider in some cases. It lacks specialized knowledge about a company and its processes and procedures and is not independent in delivering internal and external audits at the same time (Baatwah et al., Citation2019; Del Vecchio & Clinton, Citation2003; Institute of Internal Auditors IIA, Citation1994; James, Citation2003).

Although such conflicting evidence and arguments, outsourcing IAF work is an increasing phenomenon (Baatwah et al., Citation2109; Caplan & Kirschenheiter, Citation2000). It is argued that most economy’s markets demand the function of internal audit to be supplied through a different external audit firm than that performing external audit as it is identified as more independent (Baatwah et al., Citation2021). Similarly, as shown by a study by Swanger and Chewning (Citation2001), analysts perceive that an external auditor is greater independent if a company outsources its internal audit work to auditing firms except for the financial reports external audit firm. Furthermore, finding staff for internal audit with highly experienced and qualified to considered a challenge for organizations owning or preparing to set up in-house IAFs (Baatwah et al., Citation2021; Barr-Pulliam, Citation2016). An international survey study by Abdolmohammadi (Citation2013) revealed that 57% of organizations outsourced the IAF. Moreover, Mubako (Citation2019) synthesized the literature related to outsourcing IAF by concluding that organizations have a great tendency to adopt strategies for outsourcing IAF. The study also reported that the results of the majority present empirical evidence favoring external IAFs concerning service with high quality and their independence. In alignment with this, a predictive study by CBOK (2006) showed that 33% of participants expected that the demand for outsourcing for IAF would increasingly grow during the following three years (Burnaby et al., Citation2009). These arguments confirm the efficiency and effectiveness of outsourcing IA services. This research focuses on outsourcing the IAF and assumes that an external IAF provider is more effective than an internal IAF provider in shortening external audit times.

To the researchers’ knowledge, very few studies considered the issue of outsourcing the IAF with financial reports. For instance, Prawitt et al. (Citation2012) examine the relationship among the providers of internal audit outsourced and accounting risk in the U.S. by employing pre-SOX data. The scholars found a lower accounting risk significantly in firms that outsource IA services to external auditors particularly Big N providers than in companies with other kinds of outsourcing IAF. The most relevant to the present one is a study by Baatwah et al. (Citation2019), which is the only study that investigated the impact of outsourced IAF on audit efficiency using data from the Omani market. Their findings showed that external providers of internal audit services significantly contribute to improving external audit efficiency through lower audit fees and audit delay, particularly if such services are provided by Big 4- audit firms more than other types of IAF providers, concluding that IAF services have a supervising role in financial reporting in a direct or indirect.

Indeed, the literature argues that the outsourced internal audit task provider, especially a well-known audit firm, possesses specialized and qualified staff and advanced resources to sophisticate audit techniques and work (Carey et al., Citation2006). These resources can support the external provider in observing un-normal processes and analyzing the motivations that led to them, helping an external auditor to reduce the probability of audit risks, effort, and time (Baatwah et al., Citation2019). Caplan and Kirschenheiter (Citation2000) pointed out that IAF provided by larger audit firms is high-quality since it is more skilled at delivering several services of internal audits including developed resources that boost the quality of internal controls. Desai et al. (Citation2011) expected external auditors to deem the outsourced IAF to be efficient and objective. As indicated by international standards and empirical evidence, such two features are the main ones to make high-quality IAF (ISA 610; Abbott et al., Citation2016; Baatwah et al., Citation2019). Researchers also report that external auditors are allowed significantly to rely upon the IAF service if the adequacy of competence and objectivity of IAF is emphasized (Abbott et al., Citation2012; Desai et al., Citation2011; Gros et al., Citation2017; Munro & Stewart, Citation2010). It is confirmed that audit efficiency is achieved when external auditors can shorten the effort and time of audit procedures to finalize audits early (Baatwah et al., Citation2019; Bamber et al., Citation1993; Gros et al., Citation2017; Knechel & Sharma, Citation2012; Pizzini et al., Citation2015). Baatwah et al. (Citation2019) indicate that objectivity and competence make external IAF providers able effectively to control and review accounting statements and disclosure policies, discover misstatements, and propose proper corrections. Hence, it is more likely external auditors’ confidence will be increased in utilizing an IAF service to execute part or assist in external audits. According to the preceding discussion, these scenarios are predicted to support the external auditors in reducing the audit procedure, effort, and time, leading to improving the timeliness of audit reporting. Thus, this study proposes the following:

H1:

Outsourced IAF providers are associated with shorter audit delays.

4.2 Client-specific expertise of outsourced IAF providers

One primary objective of this study is to explore the moderating effect of client-specific expertise on the relationship between outsourced IAF providers and timely audit reports. Scholars have indicated that outsourced IAF providers having specific experience with their clients contribute to increasing the quality of IAF (Baatwah et al., Citation2022; James, Citation2003; Mubako, Citation2019). To gain this experience requires an individual to have conducted the same work for a long time. It is claimed that the accumulated experience across years of work significantly affects the auditor’s performance (Libby & Frederick, Citation1990). As argued by Mayer et al. (Citation2012), the external provider for a client-specific project or task can improve the specific experience and knowledge of the relevant client and promote communication and reciprocal confidence with the client if the provider performed an equal task in the previous or past, which in turn would enhance the effectiveness of work. It is stated that gaining specific expertise about the firm’s business reduces the asymmetry of internal information as it offers an in-depth familiarity with the risk and the firm’s industry. It also boosts managers’ connections with main industry actors, increasing their access to relevant information about the nature of the industry and its risks (Raweh et al., Citation2021). Accordingly, the specific experience and understanding of the client’s business and its internal control systems can be gained by the external provider for IAF if he/she serves with the same company for the long term (Baatwah et al., Citation2021).

Previous literature reported that client-specific expertise supports the ability of auditors to specify business risks (Chen et al., Citation2022; Contessotto et al., Citation2019) and also enhances their ability to detect and constrain the financial irregularities intended or unintended, increasing the quality of disclosure and accounting statements (Lai & Liu, Citation2018). This specific expertise and knowledge of the client increase with a long auditor’s tenure (Chen et al., Citation2022; Contessotto et al., Citation2019). Similarly, scholars assert that auditors with knowledge and experience resulting from an ongoing tenure with their clients are positively related to audit quality and financial reporting quality (Cahan & Sun, Citation2015; Chen et al., Citation2022; Dao & Pham, Citation2014; Habib & Bhuiyan, Citation2011). Concerning the IAF, a study by Sarens et al. (Citation2009) of a qualitative approach revealed that internal auditors who possess client-specific expertise and knowledge support the audit committee’s confidence in the internal controls’ structure.

However, the research on the value of client expertise of outsourced IAF providers is very little. Among the few studies are two by Baatwah et al (Citation2021, Citation2022), who argued that external IAF providers can be identified as firm-specific experts if they engage with their clients for lengthy tenure. Baatwah et al. (Citation2021) investigated the association between the firm-specific expertise of external IAF providers and earnings management and found that external IAF providers significantly contribute to curbing managerial opportunistic activities and constrain real earning management, particularly in emerging markets. The authors report that earnings management could be committed by violating the policies and procedures of internal control, for instance, revenue and expense recognition and raw materials flow. Therefore, since the pivotal role played by IAF in auditing and developing internal control policies concerning the organization’s operations and its financial reports, external IAF providers can establish in-depth expertise and knowledge about the internal control environment of the client through familiarity in the long term. Such expertise and knowledge assist in observing the extent of weakness in the control systems that increase the managers’ opportunity to manipulate operational activities. This experience for external providers of IAF also contributes to increased external audit efficiency (Baatwah et al., Citation2022). Therefore, it is expected that the quality of internal control would be promoted, in turn, reducing business risks and time and effort in audits. This is confirmed by Gontara et al. (Citation2023) study, which proved that internal control quality is associated with short audit report lag.

Regarding timely audit reporting, empirical evidence has proven that audit firm partners and staff work effectively to issue audit reports in a short time with a long auditor—client relationship (Chen et al., Citation2022; Dao & Pham, Citation2014; Lee et al., Citation2009; Raweh et al., Citation2021; Sharma et al., Citation2017; Wan-Hussin et al., Citation2018). In the initial period of an audit engagement, the auditor needs more time to acquire extensive knowledge and understanding of the client’s operations and risk and hence takes a longer period to issue an audit report. And so, audits are less competent compared to later periods (Bedard & Johnstone, Citation2010; Chen et al., Citation2022; Dao & Pham, Citation2014). Concerning external IAF providers, Baatwah et al. (Citation2022) study is the only research that examined the relationship between the expertise of outsourced IAF providers and audit efficiency measured by audit lag and audit fee and found that it has a significant association with audit efficiency through reducing delays in audit reporting and audit fees.

It can be argued that with the knowledge of external audit firms’ partners and advanced resources, outsourced internal audit providers could develop audit tests and analytical processes based on client-specific experience, that assist external auditors to reduce audit procedures and enhance timely audit reporting. The discussion above leads us to suppose that the client-specific expertise will support external IAF providers in managing internal controls effectively to limit the fraud and manipulation in financial statements and then decrease the anticipated audit risks, enabling the completion of the required audits quickly, and issuance and signature of the audit report promptly. We hypothesize the following hypothesis:

H2:

The client-specific expertise will enhance the relationship between outsourced IAF providers and shorter delays in audit reporting.

5. Research methodology

5.1. Data source and collection

To examine the hypotheses, this study collects data from listed Omani companies over the period 2013 – 2019. Given the amendment of some articles of the Omani Code of CG pre-2013; 2013 is selected as the first year for the study’s sample. All observations of companies during this period are 798, it is deleted 245 observations of financial and investment companies were because they have strict and unique regulations and control devices. Further, 69 observations with non-complete data are eliminated. Summarizing the sample selection and description is shown in Table . As seen in Panel A, the final sample for analysis is 484 year-observations. The sampled companies based on the industry are described in Panel B, followed by the distribution of the observations on the tested period in Panel C.

Table 1. Sample selection

This study obtains data related to audit report timeliness from audit reports. Data on IAF is extracted from corporate governance reports and websites of companies. Also, data on control variables were got from corporate governance reports, audit reports, and financial reports.

5.2. Measure of audit report timeliness

Drawing on prior scholars (e.g., Abbott et al., Citation2012; Bamber et al., Citation1993; Habib et al., Citation2019), external audit report timeliness (proxy by audit delay-AD) is defined as the number of calendar days between the fiscal year-end date and the signed audit report date.

5.3. Measures of the test variables

Outsourced IAF provider (OIAF) is measured as a value equal to “One” if the IAF is outsourced, “Zero” otherwise (Baatwah et al., Citation2019; Prawitt et al., Citation2012). Client-specific expertise for an outside IAF provider (OIAFCEX) as a moderator variable is defined as the number of consecutive years the outside internal audit provider has been engaged with that client (Baatwah et al., Citation2021; Contessotto et al., Citation2019). As the longer tenure, expertise increases. This measurement is further employed by some previous studies for the tenure of an external auditor (e.g., Chen et al., Citation2022; Gul et al., Citation2009; Lim & Tan, Citation2010; Raweh et al., Citation2021) to obtain the auditor’s expertise of a client.

5.4. Control variables

Based on prior literature (e.g., Abbott et al., Citation2012; Baatwah et al., Citation2019; Bamber et al., Citation1993; Dao & Pham, Citation2014; Raweh et al., Citation2021), this study uses some control variables that affect the audit timeliness model. First, it controls the internal governance mechanism to monitor the quality of financial reporting by including characteristics of the audit committee (AC) such as AC size (ACS), AC financial expertise (ACFX), AC independence (ACI), AC meeting (ACM), and size for the board of directors (BOZ). ACS and BOZ are both measured as the number of directors on the AC and the board of directors respectively. Other variables ACFX, ACI, and ACM are measured by the proportion of members with financial expertise on the AC, the ratio of independent directors on the AC, and the number of meetings held yearly for AC respectively. Second, this study controls the attributes of external auditor quality, such as external auditor type (ADTYP), going-concern opinion of audit (GCOP), audit firm tenure (ADFT), and audit fees (ADFEE). Respectively, these variables are identified by assigned “1” if the external auditor is one of the Big 4 audit firms and “0” otherwise; equal “1” if the firm has a going-concern opinion and “0” otherwise; the number of consecutive years the auditor has served with the company; and the natural logarithm of audit fees. Third, this study controls the company’s characteristics: ownership concentration (OWCO) measured by the largest shareholders owning ≥ 10%, firm size (LNS) measured by the natural logarithm of total assets, and performance (PROF) measured by net income deflated by total assets. Finally, this research includes dummies for industry (INDFX) and year (YEFX) indicators to control the fixed influences of industry and year. Table summarizes all definitions of the study variables

Table 2. Variables definitions

5.5. Model Specification

This study estimates its model using pooled OLS regression to test its hypotheses by following Raweh et al. (Citation2021), Baatwah et al. (Citation2021), Bamber et al. (Citation1993), and Abbott et al. (Citation2012). This study runs regression analysis with robust standard error and winsorizing continuous variables at 1 and 99 percentiles to overcome the potential effect of heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation. The following equations are formulated from the Research Model displayed in the Figure .

6. Results and discussion

6.1. Descriptive statistics

Table demonstrates the descriptive analysis of the study’s variables. For briefness, this study discusses the results related to the main variables and not to those of the control variables. The mean (median) of audit delay (AD) for a sample company is 51.67 (51) days. Despite not being included in the study’s model, IAF in-house is presented to show the IAF resource arrangement in Oman. The mean (median) of IAF in-house is 0.43(0), implying that most of the companies listed on the Omani market outsource their IAF providers. For OIAF, the mean (median) is 0.57 (1), suggesting that more than half of the Omani companies rely on outsourced providers to IAF. These results are consistent with Baatwah et al. (Citation2019) who report most Omani companies (58%) outsource IAF to external providers. Concerning the client-specific expertise of outsourced IAF providers (OIAFCEX), the mean (median) for the sampled companies is 2.59 (2). This result indicates that, on average, two and half years is the length of engagement among an external IAF provider and company.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics

Table presents the correlation matrix for the study variables. The matrix shows that outsourced IAF providers are negative and have a very marginal correlation with AD. It has shown also a negative correlation and low between the client-specific expertise of external IAF providers and AD. The study observes no very high correlation between independent and other variables. The highest correlation is (0.69) between audit fee (ADFEE) and auditor type (ADTYP), followed by company size (LNS) and ADFEE (0.52), indicating that the multicollinearity problem does not menace the estimates of study (Gujarati & Porter, Citation2009). This study supplements the correlation analysis by the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) test, the results in the untabulated table show that VIFs are below 3, implying that no multicollinearity problem.

Table 4. Correlation matrix

6.2. Regressions results

The regression results are presented in Table . We observe that the study’s models are highly significant (p < 0.001) with the F-value = 79.85 and 87.67, respectively; the explanatory power is almost 15.24, indicating that our models are fitted and explain the variance in audit delay (AD). Column (1) presents the results for the direct relationship of independent variables (OIAF and OIAFCEX) and dependent variable (AD); whereas column (2) shows findings for the interaction analysis (interaction between OIAF and OIAFCEX).

Table 5. Regressions results

The regression coefficients in Column (1) reveal that outsourced IAF providers (OIAF) are negative and marginally significant at p < 0.10 with AD (coefficient = −0.806, t-statistics = −2.420). This is preliminary evidence suggesting that outsourced IAF providers are associated with audit timeliness relative to companies with outsourced IAF. This marginal result may be due to a lack of understanding and knowledge of the client’s business. While, the results also reveal that the coefficient of client-specific expertise (OIAFCEX) is a negative and significant determinant of audit report timeliness (AD) at p < 0.01 (coefficient = −6.092, t = −5.410), indicating that client-specific expertise of outsourced IAF providers significantly contributes to shortening the time of audit reporting and enhancing the disclosure deadline of annual reports. This result reinforces Baatwah et al. (Citation2022) study, which shows external IAF providers with knowledge and expertise support audit efficiency by reducing audit fees and delays in audit reporting.

Excitingly, the results in Column 2 present the coefficient of the interaction between client-specific expertise and outsourced IAF providers (OIAF * OIAFCEX) is negative and statically significant at p < 0.01 (coefficient = −2.760, t-statistics = −4.08) with AD, suggesting that over-familiarity with clients’ businesses strengthens the effectiveness of external IAF providers in increasing the usefulness of accounting information by providing audit reports promptly, and in turn, increasing financial reporting quality. Thus, H2 is supported. These results support the earlier argument that experts IAs have an extensive accounting background and knowledge base enabling them to comprehend and analyze financial problems quickly, narrowing agency conflicts (Adams, Citation1994). Consequently, audit risks would be minimized, which assists external auditors in reducing substantive-level tests and effort and time of audit work. This result reinforces the view that the knowledge and experience about the client’s business restrict accounting misstatements “intended or un-intended” and limit audit business risk, hence increasing the quality of financial reporting (Cahan & Sun, Citation2015; Chen et al., Citation2022; Wan-Hussin et al., Citation2018) and the external auditors’ confidence in the quality of accounting statements and internal controls systems (Chen et al., Citation2008). Hence supporting the external auditors’ performance in reducing audit tests and effort, contributing to minimizing the delay in audit reporting (Chen et al., Citation2022; Gontara et al., Citation2023; Wan-Hussin et al., Citation2018).

This finding is consistent with the result of Baatwah et al. (Citation2021) that proved outside IAF with client-specific expertise hinders practices of real earnings management. It further supports earlier external audit studies on auditor client-specific expertise, example, Chen et al. (Citation2022), Raweh et al. (Citation2021), Wan-Hussin et al. (Citation2018), and Sharma et al. (Citation2017), all revealed a negative relationship between client-specific expertise of external auditors and audit reports delays; indicating that auditors who boosted their knowledge through their over-familiarity with clients’ business are related to high-quality audit and timely audit reports. It is also aligned with the general perspective of outsourced IAF literature (Baatwah et al., Citation2021; Mubako, Citation2019; Prawitt et al., Citation2012), implying that outsourced IAF providers provide great-quality tasks and thus increased audit efficiency and quality financial reports. Such results are also robust to an alternative method for measuring client-specific expertise and reveal empirical evidence indicating that an outsourced IAF provider who has client-specific expertise is associated with a strong decrease in audit delay. This result implies that this type of expertise is complementary and contributes significantly to minimizing delays in audit reports, more than those without this expertise.

The results show that the two hypotheses are confirmed. In line with agency theory and prior research, this research suggests that IAF is an effective internal monitoring mechanism guaranteeing the quality of accounting information and reducing agency problems. Overall, these results support the argument of agency theory that IAF is a significant control mechanism to protect a company’s assets and its financial integrity, particularly if they have knowledge and experience can contribute effectively to monitoring management activities and support internal control and external auditors’ work (Adams, Citation1994; Mat Zain et al., Citation2015), which leads to align interests of stakeholders, hence mitigating agency problems and create high value for companies (Langrafe et al., 2020; Caplan & Kirschenheiter, Citation2000).

Regarding the control variables presented in Table , the results are consistent with prior research (e.g., Baatwah et al., Citation2019; Raweh et al., Citation2021; Wan-Hussin et al., Citation2018). As shown in Table , audit committee financial expertise (ACFX), board size (BOZ), concentrated ownership (OWCO), and performance (PROF) are negatively and significantly associated with audit report delay (AD), implying that companies with a higher proportion of expertise, larger size, higher concentrated ownership, and high performance measured by profitability engage in reducing delay in audit reporting. In contrast, audit firm tenure (ADFT) and going concern opinion (GCOP) have a positive and significant association with AD, suggesting impeded audit timeliness. The rest of the control variables show insignificant coefficients, signifying that characteristics of the audit committee; size (ACS), independence (ACI) and meetings (ACM), also auditor type (ADTYP), and audit fees (ADFEE) have a marginal effect on audit report timeliness.

6.3. Robustness tests

To examine the robustness of the previous finding for the full sample related to client-specific expertise. For briefness, this study represses the findings of control variables. The external and internal audit literature employs a dichotomous method to measure tenure. These studies split up auditor’s tenure into long and short tenures and deems long tenure ranging from 7–9 years or above as a high degree of client-specific expertise, and short tenure is ≤ 3, as a low degree of client-specific expertise. In line with this approach, this study creates two measures for the client-specific expertise of outsourced IAF providers, first: An outsourced IAF provider with a high degree of client-specific expertise (OIAFHEX) equal “1” if he/she has more than 7 years of tenure; second measure: the outsourced IAF provider is with a low degree of client-specific expertise (OIAFLEX) equal “1” if he/she has less than 3 years’ tenure. Such measures may imply that short tenure for outsourced IAF providers means a lack of expertise in the client’s business. Long tenure is related to extensive expertise with the client’s business hence issuing audit reports promptly. From Table , the results reveal that the coefficient of OIAFHEX is negative and strongly significant with AD at p < 0.01, whereas the coefficient of OIAFLEX is positive and insignificant, confirming our initial findings.

Table 6. Results for alternative measures of outsourced IAF provider with client-specific expertise

7. Conclusion

The present study examines the moderating effect of client-specific expertise on the relationship between outsourced IAF providers and audit report timeliness. It also attempts to bridge a significant gap in the existing literature concerning outsourced IAF with audit report timeliness. This study has used panel data regressions for 484 observations during the period 2013–2019. Unlike previous IAF studies, this research uses a measure of IAF by employing external providers for IAF rather than the traditional structure which is “in-house”. The results indicate that outsourced IAF providers are slightly associated with shorter delays in audit reports. They also illustrate that audit reporting timeliness is significantly enhanced when the outsourced IAF providers are more familiar with clients’ business by reducing delays in audit reports. This finding is interesting due to it signifies that the external IAF providers with longer tenure leverage their client-specific expertise to deliver high-quality IAF. Furthermore, these findings are also robust to an alternative method for measuring client-specific expertise and reveal empirical evidence indicating that an outsourced IAF provider with higher client-specific expertise is associated with a strong decrease in audit delay. This result implies that this type of expertise is complementary and contributes effectively to minimizing delays in audit reports, more than those without this expertise. Overall, this study shows that this type of expertise for IAF providers is a critical factor and contributes effectively to strengthening the timeliness of reporting that would support the value and usefulness of information for decision-makers, reduce leaking information and rumors about the health of a company’s financial status, and hence restore the investors’ trust in equity capital markets, particularly in emerging markets.

This study has theoretical and empirical implications. First, it enriches the accounting and auditing literature, specifically recent streams of research that are interested in outsourced IAF, by providing novel empirical insight into the moderating effect of client-specific expertise on the relationship between external IAF providers and timely audit reporting. Second, this study is the first of its kind to document the significance of the indirect effect of acquiring a client’s expertise over a long duration by an external IAF provider, and its positive effect in supporting the external auditor effectively to shorten audit time and effort, meet hence disclosure deadlines, and increase the quality of accounting information. Accordingly, this study provides new evidence and contributions to the literature at the level of IAF and timely reports. Third, from the side of practical implications, the findings benefit the stakeholders and policymakers for performing a systemic analysis to choose an expert IAF provider, since an expert would increase the quality of financial information, particularly minimizing delays in audit reports. The findings also are of interest to the companies and auditors to know how they can save the effort and time of external audits and meet disclosure deadlines by considering the client-specific expertise of IAF providers. The study also is useful for regulators to support IAF policy and outsourcing IAF rather than only relying on setting up in-house IAF. This study has some limitations in Interpreting these findings. First, this study has used expertise about the client’s business. Therefore, it suggests using other measures for expertise for future studies. Finally, although this research’s results could apply to several economies, we call to be careful in generalizing these findings because the outcomes of this study are based on an emerging economy with cultural and institutional contexts different from those in developed countries. Thus, future research is open to perform in the different settings

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgement

This study is supported via funding from Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University (PSAU/2023/R/1445)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nahla Abdulrahman Mohammed Raweh

Nahla Abdulrahman Mohammed Raweh is an assistant professor of Accounting at Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia, and Hodeidah University, Yemen. She finished her Ph.D in Accounting at University Utara Malaysia. Her research interests include auditing, financial reporting and accounting, corporate governance and cost accounting.

Abdulwahid Ahmed Hashed Abdullah

Abdulwahid Ahmed Hashed Abdullah is an Associate Professor of Accounting at Prince Sattam BinAbdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia. He held Ph.D. in Accounting at Pune University- India. His research interests include cost accounting, financial accounting, auditing, financial reporting, and corporate governance

References

- Abbott, L. J., Daugherty, B., Parker, S., & Peters, G. F. (2016). Internal audit quality and financial reporting quality: The joint importance of independence and competence. Journal of Accounting Research, 54(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12099

- Abbott, L. J., Parker, S., & Peters, G. F. (2012). Internal audit assistance and external audit timeliness. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 31(4), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-10296

- Abbott, L. J., Parker, S., Peters, G. F., & Rama, D. V. (2007). Corporate governance, audit quality, and the sarbanes‐Oxley act: Evidence from internal audit outsourcing. The Accounting Review, 82(4), 803–835. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2007.82.4.803

- Abdolmohammadi, M. (2013). Correlates of co-sourcing/outsourcing of internal audit activities. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 32(3), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-50453

- Abdullah, R., Ismail, Z., & Smith, M. (2018). Audit committees’ involvement and the effects of quality in the internal audit function on corporate governance. International Journal of Auditing, 22(3), 385–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijau.12124

- Adams, M. B. (1994). Agency theory and the internal audit. Managerial Auditing Journal, 9(8), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686909410071133

- Ahlawat, S. S., & Lowe, D. J. (2004). An examination of internal auditor objectivity: In‐house versus outsourcing. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 23(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.2004.23.2.147

- Al‐Sukker, A., Ross, D., Abdel‐Qader, W., & Al‐Akra, M. (2018). External auditor reliance on the work of the internal audit function in Jordanian listed companies. International Journal of Auditing, 22(2), 317–328. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijau.12122

- Al-Akra, M., Abdel-Qader, W., & Billah, M. (2016). Internal auditing in the middle East and North Africa: A literature review. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing & Taxation, 26, 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2016.02.004

- Alzeban, A., & Gwilliam, D. (2014). Factors affecting the internal audit effectiveness: A survey of the Saudi public sector. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing & Taxation, 23(2), 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2014.06.001

- Anderson, D., Francis, J. R., & Stokes, D. J. (1993). Auditing, directorships and the demand for monitoring. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 12(4), 353–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-4254(93)90014-3

- Arnold, S., & Wilner, N. (1990). A test of audit deterrent to financial reporting irregularities using the randomized response technique. The Accounting Review, 65(3), 668–681. https://www.jstor.org/stable/247956

- Baatwah, S. R., Al‐Ebel, A. M., & Amrah, M. R. (2019). Is the type of outsourced internal audit function provider associated with audit efficiency? Empirical evidence from Oman. International Journal of Auditing, 23(3), 424–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijau.12170

- Baatwah, S. R., Omer, W. K. H., & Aljaaidi, K. S. (2022). Does the expertise of outsourced IAF providers affect audit efficiency? Empirical evidence from an emerging market. Pacific Accounting Review, 34(2), 249–273. https://doi.org/10.1108/PAR-04-2021-0044

- Baatwah, S. R., Omer, W. K., & Aljaaidi, K. S. (2021). Outsourced internal audit function and real earnings management: The role of industry and firm expertise of external providers. International Journal of Auditing, 25(1), 206–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijau.12217

- Bajra, U., & Cadez, S. (2018). The impact of corporate governance quality on earnings management: Evidence from European companies cross‐listed in the US. Australian Accounting Review, 28(2), 152–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/auar.12176

- Bamber, E. M., Bamber, L. S., & Schoderbek, M. P. (1993). Audit structure and other determinants of audit report lag: An empirical analysis. Auditing, 12(1), 1–23. https://search.proquest.com/docview/216739816?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true

- Barr-Pulliam, D. (2016). Engaging third parties for internal audit activities. Retrieved from https://www.iia.nl/SiteFiles/Downloads/IIARF%20CBOK%20Engaging%20Third%20Parties%20For%20IA%20Activities%20Jan%202016_0.pdf

- Beasley, M. S., Carcello, J. V., Hermanson, D. R., & Lapides, P. D. (2000). Fraudulent financial reporting: Consideration of industry traits and corporate governance mechanisms. Accounting Horizons, 14(4), 441–454. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch.2000.14.4.441

- Bedard, J. C., & Johnstone, K. M. (2010). Audit partner tenure and audit planning and pricing. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 29(2), 45–70. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.2010.29.2.45

- Behrend, J., & Eulerich, M. (2019). The evolution of internal audit research: A bibliometric analysis of published documents (1926–2016). Accounting History Review, 29(1), 103–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/21552851.2019.1606721

- Beisland, L. A., Mersland, R., & Strøm, R. Ø. (2015). Audit quality and corporate governance: Evidence from the microfinance industry. International Journal of Auditing, 19(3), 218–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijau.12041

- Burnaby, P., Hass, S., & Cooper, B. J. (2009). A summary of the global common body of knowledge 2006 (CBOK) study in internal auditing. Managerial Auditing Journal, 24(9), 813–834. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900910994782

- Cahan, S. F., & Sun, J. (2015). The effect of audit experience on audit fees and audit quality. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 30(1), 78–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558X14544503

- Capital Market Authority (CMA). (2002). Rules for the constitution of audit committee and appointment of internal auditor and legal advisor. ( Article 6 C.F.R (2002)). Capital Market Authority.

- Caplan, D. H., & Kirschenheiter, M. (2000). Outsourcing and audit risk for internal audit services. Contemporary Accounting Research, 17(3), 387–428. https://doi.org/10.1506/8CP5-XAYG-7U37-H7VR

- Carey, P., Simnett, R., & Tanewski, G. (2000). Voluntary demand for internal and external auditing by family businesses. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 19(s–1), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.2000.19.s-1.37

- Carey, P., Subramaniam, N., & Ching, K. C. W. (2006). Internal audit outsourcing in Australia. Accounting & Finance, 46(1), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-29X.2006.00159.x

- Chen, L. H., Chung, H. H., Peters, G. F., & Wynn, J. P. (2017). Does incentive-based compensation for chief internal auditors impact objectivity? An external audit risk perspective. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 36(2), 21–43. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-51575

- Chen, C., Jia, H., Xu, Y., & Ziebart, D. (2022). The effect of audit firm attributes on audit delay in the presence of financial reporting complexity. Managerial Auditing Journal, 37(2), 283–302. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-12-2020-2969

- Chen, C. Y., Lin, C. J., & Lin, Y. C. (2008). Audit partner tenure, audit firm tenure, and discretionary accruals: Does long auditor tenure impair earnings quality? Contemporary Accounting Research, 25(2), 415–445. https://doi.org/10.1506/car.25.2.5

- Contessotto, C., Knechel, W. R., & Moroney, R. A. (2019). The association between audit manager and auditor-in-charge experience, effort, and risk responsiveness. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 38(3), 121–147. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-52308

- Dang, V. C., & Nguyen, Q. K. (2021). Internal corporate governance and stock price crash risk: Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2021.2006128

- Dang, V. C., & Nguyen, Q. K. (2022). Audit committee characteristics and tax avoidance: Evidence from an emerging economy. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(10(1), 2–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2021.2023263

- Dao, M., & Pham, T. (2014). Audit tenure, auditor specialization and audit report lag. Managerial Auditing Journal, 29(6), 490–512. https://doi.org/10.1108/maj-07-2013-0906

- Del Vecchio, S. C., & Clinton, B. D. (2003). Cosourcing and other alternatives in acquiring internal auditing services. Internal Auditing, 18(3), 33–39.

- Desai, N. K., Gerard, G. J., & Tripathy, A. (2011). Internal audit sourcing arrangements and reliance by external auditors. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 30(1), 149–171. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.2011.30.1.149

- Durand, G. (2019). The determinants of audit report lag: A meta-analysis. Managerial Auditing Journal, 34(1), 44–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-06-2017-1572

- Fadzil, F. H., Haron, H., & Jantan, M. (2005). Internal auditing practices and internal control system. Managerial Auditing Journal, 20(8), 844–866. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900510619683

- Glover, S. M., Prawitt, D. F., & Wood, D. A. (2008). Internal audit sourcing arrangement and the external auditor’s reliance decision. Contemporary Accounting Research, 25(1), 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1506/car.25.1.7

- Gontara, H., Khelil, I., & Khlif, H. (2023). The association between internal control quality and audit report lag in the French setting: The moderating effect of family directors. Journal of Family Business Management, 13(2), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFBM-11-2021-0139

- Gros, M., Koch, S., & Wallek, C. (2017). Internal audit function quality and financial reporting: Results of a survey on German listed companies. Journal of Management & Governance, 21(2), 291–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-016-9342-8

- Gujarati, D. N. & Porter, D. C.(2009). Basic econometrics (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

- Gul, F. A., Fung, S. Y. K., & Jaggi, B. (2009). Earnings quality: Some evidence on the role of auditor tenure and auditors’ industry expertise. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 47(3), 265–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2009.03.001

- Habib, A., & Bhuiyan, M. B. U. (2011). Audit firm industry specialization and the audit report lag. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing & Taxation, 20(1), 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2010.12.00

- Habib, A., Bhuiyan, M. B. U., Huang, H. J., & Miah, M. S. (2019). Determinants of audit report lag: A meta‐analysis. International Journal of Auditing, 23(1), 20–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijau.12136

- Harjoto, M. A., & Laksmana, I. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on audit fees and audit delay: International evidence. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management, 30(4), 526–545. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJAIM-02-2022-0030

- Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA). (1994). In Institute of internal auditors. Ed., A professional briefing for chief audit executives: The Iia’s perspective on outsourcing internal auditing. Institute of Internal Auditors.

- James, K. L. (2003). The effects of internal audit structure on perceived financial statement fraud prevention. Accounting Horizons, 17(4), 315–327. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch.2003.17.4.315

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- Khelil, I. (2023). The working relationship between internal and external auditors and the moral courage of internal auditors: Tunisian evidence. Arab Gulf Journal of Scientific Research, 41(4), 462–477. https://doi.org/10.1108/AGJSR-07-2022-0121

- Khelil, I., & Khlif, H. (2022). Internal auditors’ perceptions of their role as assurance providers: A qualitative study in the Tunisian public sector. Meditari Accountancy Research, 30(1), 121–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-04-2020-0861

- Knechel, W. R., & Sharma, D. S. (2012). Auditor-provided nonaudit services and audit effectiveness and efficiency: Evidence from pre-and post-SOX audit report lags. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 31(4), 85–114. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-10298

- Lai, S. M., & Liu, C. L. (2018). The effect of auditor characteristics on the value of diversification. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 37(1), 115–137. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-51831

- Lee, H. Y., Mande, V., & Son, M. (2009). Do lengthy auditor tenure and the provision of non‐audit services by the external auditor reduce audit report lags? International Journal of Auditing, 13(2), 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-1123.2008.00406.x

- Leung, P., Cooper, B. J., & Cooper, B. J. (2009). Internal audit – an Asia-Pacific profile and the level of compliance with internal Auditing standards. Managerial Auditing Journal, 24(9), 861–882. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900910994809

- Libby, R., & Frederick, D. M. (1990). Experience and the ability to explain audit findings. Journal of Accounting Research, 28(2), 348–367. https://doi.org/10.2307/2491154

- Lim, C.-Y., & Tan, H.-T. (2010). Does auditor tenure improve audit quality? Moderating effects of industry specialization and fee dependence. Contemporary Accounting Research, 27(3), 923–957. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.2010.01031.x

- Mat Zain, M., Zaman, M., & Mohamed, Z. (2015). The effect of internal audit function quality and internal audit contribution to external audit on audit fees. International Journal of Auditing, 19(3), 134–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijau.12043

- Mayer, K. J., Somaya, D., & Williamson, I. O. (2012). Firm-specific, industry-specific, and occupational human capital and the sourcing of knowledge work. Organization Science, 23(5), 1311–1329. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0722

- Mubako, G. (2019). Internal audit outsourcing: A literature synthesis and future directions. Australian Accounting Review, 29(3), 532–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/auar.12272

- Munro, L., & Stewart, J. (2010). External auditors’ reliance on internal audit: The impact of sourcing arrangements and consulting activities. Accounting & Finance, 50(2), 371–387. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-629X.2009.00322.x

- Oussii, A. A., & Taktak, N. B. (2018). Audit report timeliness: Does internal audit function coordination with external auditors matter? Empirical evidence from Tunisia. EuroMed Journal of Business, 13(1), 60–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/EMJB-10-2016-0026

- Pizzini, M., Lin, S., & Ziegenfuss, D. E. (2015). The impact of internal audit function quality and contribution on audit delay. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory [ Retrieved from], 34(1), 25–58. http://ssrn.com/abstract¼1673490

- Prawitt, D. F., Sharp, N. Y., & Wood, D. A. (2012). Internal audit outsourcing and the risk of misleading or fraudulent financial reporting: Did Sarbanes‐Oxley get it wrong? Contemporary Accounting Research, 29(4), 1109–1136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.2012.01141.x

- Raweh, N. A. M., Abdullah, A. A. H., Kamardin, H., Malek, M., & Ntim, C. G. (2021). Industry expertise on audit committee and audit report timeliness. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1920113

- Raweh, N. A. M., Kamardin, H., Malik, M., & Abdullah, A. A. H. (2021). The association between audit partner busyness, audit partner tenure, and audit efficiency. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 11(1), 90–103. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.aefr.2021.111.90.103

- Rittenberg, L., & Covaleski, M. A. (2001). Internalization versus externalization of the internal audit function: An examination of professional and organizational imperatives. Accounting, Organizations & Society, 26(7–8), 617–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(01)00015-0

- Sarens, G., De Beelde, I., & Everaert, P. (2009). Internal audit: A comfort provider to the audit committee. The British Accounting Review, 41(2), 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2009.02.002

- Selim, G., & Yiannakas, A. (2000). Outsourcing the internal audit function: A survey of the UK public and private sectors. International Journal of Auditing, 4(3), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/1099-1123.00314

- Sharma, D. S., Tanyi, P. N., & Litt, B. A. (2017). Costs of mandatory periodic audit partner rotation: Evidence from audit fees and audit timeliness. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 36(1), 129–149. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-51515

- Swanger, S. L., & Chewning, E. G., Jr. (2001). The effect of internal audit outsourcing on financial analysts’ perceptions of external auditor independence. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 20(2), 115–129. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.2001.20.2.115

- Wan-Hussin, W. N., & Bamahros, H. M. (2013). Do investment in and the sourcing arrangement of the internal audit function affect audit delay? Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics, 9(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcae.2012.08.001

- Wan-Hussin, N. W., Bamahros, H. M., & Shukeri, S. N. (2018). Lead engagement partner workload, partner-client tenure and audit reporting lag: Evidence from Malaysia. Managerial Auditing Journal, 33(3), 246–266. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-07-2017-1601