Abstract

This paper investigates the antecedents and the consequences of ICC from the perspectives of the employees and validates the framework and operational definition of ICC in high-risk industry, which is yet to be identified in the past literature. Existing academic literature are used to develop the framework and conceptualizing the variables. This is followed by direct interviews with the engineers and administrative staff of the industry to confirm the antecedents and consequences of ICC. The qualitative data is analyzed using QSR Nvivo version 12.0 software while a deductive content analysis is used to classify the data using themes and keywords. The employees presented different views on high-risk industry as related to the antecedents and consequences of ICC. The findings show that the employee crisis perceptions are clearly played as a consequence of internal crisis communication in their workplace. This study further makes clarification by developing new concepts of ICC with clearer insights on the antecedents and consequences. This new development poses as blueprint to help the high-risk industries by successfully integrating the ICC framework into corporate management strategies. Also, this study revisited the concepts of ICC in a specific context and confirmed its antecedents and consequences through development of new measurements.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Notwithstanding the fact that vital information on the reciprocal interaction between managers and employees in times of crisis has been overemphasised, there is still paucity of research on internal communication crisis (ICC) and crisis management in high-risk industries. Due to this, the study analyses the antecedents and consequences of ICC from the perspective of key informants and validates the framework and operational definition of ICC. The results reveal that, safety culture, supportive environment, and management commitment are salient antecedents of ICC. Similarly, the study finds that employee crisis perception is clearly a consequence of ICC in the industry. This work addresses the issue further by proposing new ICC ideas with greater insights into the antecedents and consequences. This new development serves as a blueprint to high-risk industries through successful integratiion the ICC framework into corporate management strategies.

1. Introduction

Over the last decade, important information on mutual relationship between the managers and employees in times of crisis has been overemphasized. More specifically, a number of studies have demonstrated that employee conduct is important during crisis while internal communication and crisis management serve as a driver for positive outcomes (Björck & Barthelmess, Citation2019; Ecklebe & Löffler, Citation2021; Frandsen & Johansen, Citation2011; Mazzei et al., Citation2012, Citation2019; Taylor, Citation2010). With the increase in call for managers to include employees as important stakeholders during crisis, a surge in the formalization of employee participation in designing policies and strategies is getting attention (Andersson, Citation2020). This is due to the fact that organizational performance has been linked to employees’ communication on information, ideas and suggestion with the management regarding problems concerning the organizational survival (Kim & Lim, Citation2020; Mohamad et al., Citation2019). Literature on crisis management has consistently shown that employees are the key to the ability of an organization to resuscitate after crisis (Kim, Citation2020). However, there is still scant literature that looks at manager-to-employee’s communication in high-risk industry in times of crises.

To be strategic in internal crisis communication, to improvise and listen to the employees with their demands for sensemanking, organizations need to be aware of their culture and environment (Heide & Simonsson, Citation2020; Strandberg & Vigsø, Citation2016). Communication produce and reproduce organization while employees act based on their understanding of situations. They are both ambassadors and communicators of an organizations (Heide & Simonsson, Citation2014; Mazzei & Butera, Citation2021) as they communicate with their family, friends, relatives and media. Therefore, internal crisis communication can be a success or failure in a crisis situation (Mazzei & Ravazzani, Citation2015). It can therefore be argued that the quality and quantity of communication can influence the degree of trust and involvement of employees (Adamu & Mohamad, Citation2019a). This is supported by the argument that strategic initiatives and working with internal crisis communication constitute a profound way for an organization to become communicative (Simonsson & Heide, Citation2018).

Noting the compelling nature of this new evidence, Johansen et al. (Citation2012) reported that researchers on crisis communication have specifically focused on the external stakeholders, i.e., crises response strategy used by organization in protecting reputation from damage. Although research in the specific area of internal crisis communication is growing but still limited, indicating that it is a topic of emerging interest as the ramifications of internal communication become clearer in regards to organizational culture and strategic management goals (Palm, Citation2016).

Apart from being largely focusing on external stakeholder rather than internal stakeholders (employees), the underlying factors of ICC are another research gap that needs to be addressed. Despite a comprehensive literature review, previous studies have highlighted a paucity of literature and lack of theoretical development on ICC (Adamu et al., Citation2016; Frandsen & Johansen, Citation2011; Heide & Simonsson, Citation2019; Ravazzani, Citation2016). Hence, a research on the underlying factors of ICC will help the practitioners and policy makers to understand the implementation of ICC framework in the high-risk industry. More specifically, many scholars have suggested looking further into antecedents of ICC such as safety culture, supportive environment, and management commitment as part of the important results of ICC (Adamu & Mohamad, Citation2019b; Frandsen & Johansen, Citation2011; Heide, Citation2013).

Fundamentally, research on ICC are based on the Western context and theories. Across the nations, the issues of theoretical applicability are employed (Tsui, Citation2006). To establish external validity, many academic community and literature need new studies in different contexts in order to globally respond to research by testing the relationship between the new context and existing theories (Boyacigiller & Adler, Citation1991; Mohamad et al., Citation2018; Peng et al., Citation1991; Sekaran, Citation1981; Tsui, Citation2006). Many assumptions related to community and their institutional contexts are employed by the Western theories. Thus, investigating ICC framework in Malaysia’s high-risk industry provides additional insights into the already established literature, as Malaysian workers and their cultural contexts vary from those in western countries significantly (Abdullah & Lim, Citation2001; Abu Bakar et al., Citation2016; Hofstede, Citation1980). Notably, the collectivist culture of Malaysian context is different from the Western (Hofstede, Citation1980).

Thus, this study contributes to internal crisis communication research by empirically examining internal crisis communication in the Oil and Gas sector. It is a sector that is prone to crisis but often overlooked by researchers. In doing so, the study provides practical and theoretical implication on internal crisis communication surrounding elements of effective internal organizational relationship (Frandsen & Johansen, Citation2011; Taylor, Citation2010) and leadership (Heide & Simonsson, Citation2019) that are Oil and Gas sector specific. By differentiating multiple factors fostering network of relationship between an organization and its employees during crisis situation, this study contributes to theory building on internal crisis communication. In addition, the research yields managerial knowledge regarding strategies to promote favorable opinion of employees toward their organization in a negative situation.

Applying a qualitative approach, this study examined these antecedents of internal crisis communication. The study also explored whether internal crisis influences employee crisis perception. This supports the notion of network theory that shows the need to explore how information and resource-based relationships influence organizational outcomes (Taylor, Citation2010). Therefore, this study intends to address the issues of lack of understanding of what ICC entails by exploring the ICC operational concept in high-risk industry from the perspectives of employees. This article is based on empirical material from a two-year research project that focuses on internal crisis communication in highly reliable organizations in Malaysia. Below follows a discussion of Malaysian high-risk industries and a review on the antecedents and consequences of internal crisis communication in the context of high-risk industries. That section is followed by a presentation of how the empirical material was collected and analyzed. Lastly, the third section presents the analysis while the final section presents the conclusion.

2. Literature Review

2.1. High-Risk Industry in Malaysia

In the context of Malaysia, high-risk industries such as Oil and Gas industry or Commercial Aviation have developed rapidly. The demand for internal crisis communication becomes severe after the series of crisis such as the missing flight of MH370 and air crash of MH17. Having knowledge on the present regional and global markets for high-risk industry, Malaysian organizations need to develop a corporate reputation through excellence management of crisis communication. Therefore, the ICC should be well-delivered to the concerned stakeholders with a consistent and effective manner. Under these circumstances, organizations have finally realized the roles of ICC as a powerful source of maintaining operation and reputation.

Many organizations will be helped by strategically managing ICC to competitive advantage over others. As a consequence, a growing number of organizations in high-risk industry have started to develop and implement internal crisis communication as part of their strategic growth and expansion. Many scholars have suggested looking further into antecedents of ICC such as safety culture, supportive environment, and management commitment as part of the important indicators to ICC (Frandsen & Johansen, Citation2011; Heide, Citation2013). These determinants of ICC are intangible elements that can help organizations’ situation by maintaining and enhancing their corporate reputation and providing an immense competitive advantage to the organization (Sadri & Lees, Citation2001). The contributions of those elements have been proven by many management studies in the context of organizational system.

2.2. The Concept of ICC in High-Risk Industry

Existing research has shown that crisis distresses and impacts organizational rudimentary expectations, intimidating legitimacy and challenges decision-making process as well as negatively affect organizational performance (Coombs, Citation2015; Kim, Citation2020). Hence, to effectively manage an organizational crisis, internal stakeholders, i.e. the employee’s role is crucial; an act of employee can either minimize or possibly exacerbate a situation during a crisis (Lee, Citation2019). Crisis communication and communication scholars have demonstrated that organizations’ communication practices with employees in a symmetrical manner increase the quality of a relationship between an organization and its employees (Lee & Kim, Citation2021). As a matter of fact, employees have received remarkably little attention in practice and research within the area of study (Heide & Simonsson, Citation2011). Internal relationship and processes need to be studied in order to expand crisis communication research which emphasize the importance of internal crisis communication (Heide & Simonsson, Citation2019; Taylor, Citation2010).

Many scholars have discussed the conceptualisation of internal crisis communication from different point of views (e.g. Adamu & Mohamad, Citation2019a; Frandsen & Johansen, Citation2011; Heide & Simonsson, Citation2015; Taylor, Citation2010). Internal communication is seen to serve as a knob that assists in preventing crises, creating positive results, minimizing damages and finally yielding positive reactions (Mazzei & Ravazzani, Citation2013; Mazzei et al., Citation2012). According to Johansen et al. (Citation2012), ICC is “a connection between managers and employees through communication in an organization before, during and after a crisis”. In fact, organizations respond to crisis as a direct result of complex internal interpretation process and communication amongst employees (Heide & Simonsson, Citation2019). Past studies have also shown that internal crisis communication is a product of existing organizational internal communication, management practice and crisis event type (Björck & Barthelmess, Citation2019).

One of the main elements of internal crisis communication is to examine resilience and mindfulness of organizational crisis, including the ability of internal stakeholders to recover from the crisis and return to normalcy (Weick & Sutcliffe, Citation2001). In particular, high-risk industry has been classified as organizations committed to resilience, such as organizations that engage in anticipating activities, which include learning from failure (Weick & Sutcliffe, Citation2001). Generally, the concept of resilience means the ability of an organization to recover from a major mishap or continue to operate under stress. Therefore, such organization trains their internal stakeholders on how to manage the inflicted trauma as a result of the crisis. The organizations with resilience orientation and features like dialogue are embraced as a tool of knowledge-sharing for the organization’s stakeholders (Olsson, Citation2014). In the context of high-risk industry, the site engineers and senior managers who perform the roles of communication professionals during crises are only involved when the crises have occurred, which is regarded as communication on demand approach (Heide & Simonsson, Citation2013).

On the whole, a number of scholars concluded that internal crisis communication concentrated on the need for information, communication and sensemaking between organizational management and employees during a crisis situation (Heide & Simonsson, Citation2014). As a matter of fact, sensemaking theory demonstrates how essential internal crisis communication is to high-risk industry, as employees’ sensemaking affects their behavior and action during crisis (Heide & Simonsson, Citation2015; Mazzei et al., Citation2012; Weick, Citation1979). In addition, Maitlis and Sonenshein (Citation2010) asserted that crisis presents a strong and powerful situation for sensemaking. Therefore, investigating internal crisis communication from a Malaysian High-Risk industry will add a new perspective to this research area of crisis with the scant of literature from a non-western setting.

2.3. Theoretical Assumptions

This study draws its inspiration from the Network theory. As literature has demonstrated, socially constructed phenomenon can be explained and explored for comprehension and precision from a theoretical perspective. Network theory has been identified to be useful in the study of internal crisis communication (Taylor, Citation2010). The theory has been employed to investigate employee turnover, organizational change, and leadership. Organizations do not respond to each of their stakeholders individually, but rather must respond to the instantaneous demand of multiple stakeholders (Rowley, Citation1997). Again, internal crisis communication research has been called to begin with understating internal relationships (Frandsen & Johansen, Citation2011). Network theory can help public relations scholars to better understand the existing relationship inside organizations and once the intricate relational and communication dynamics inside an organization is comprehended, where there are holes can be better comprehended (Taylor, Citation2010). Notably, network theory is found relevant to explicate internal relationship in high reliability organization during crisis because of its focus on internal factors enhancing effective communication.

For many decades, the networking theory has been used in business management studies to examine how information and resource-based relationships impact organizational outcomes. More specifically, it has been applied in studies examining organizational change, leadership and employee turnover. Based on these findings, Taylor (Citation2010) asserted that communication scholars can apply this theory to better understand the existing relationships within organization. In particular, Network theory can identify weak and strong relationship within an organization during crisis. From these premises, investigating supportive environment and safety culture is supported in this study. Therefore, internal crisis communication theory is extended by examining the critical factors of relationship building and crisis management.

In the same vein, Network theory also recognizes the critical role played by organizational leadership in crisis management. For example, a number of researchers have reported that it is the role of a leader to make sense of crises situation and develop meaning for employees with effective leadership communication (Yeomans & Bowman, Citation2021). Specifically, organizational leadership demonstrates the opportunity to encourage and direct others in the creation and execution of shared vision, long-term quality plans and clear goals (Abbas et al., Citation2020, Citation2021). The impact of leadership in creating positive organizational climate on employees, decision-making as well as implementation and the management of a negative situation is crucial to organizational success (Abbas et al., Citation2020). At the heart of this communication effort is employee involvement which plays a role in motivating and supporting employees (Hussain et al., Citation2018; Ogbeibu et al., Citation2018, Citation2021). An organizational leadership is privileged to have access to information and can choose to frame, distribute and withhold it on the basis of various interests such as developing productive and sustainable environment (Samimi et al., Citation2020). This highlights the important of organization leadership as demonstrated by Networking theory and crisis management literature.

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has added a new concern for crisis communication practitioners and management efforts because of the unique crisis demands it created (Coombs, Citation2020; Sia & Adamu, Citation2020). As identified by Heide and Simonsson (Citation2021), a pandemic demands a leadership, culture as well as communicative approach that demonstrated the importance of employees. Recent research studies have shown that organizational leadership influences effective internal crisis communication which in turn increases employee knowledge sharing during the COVID-19 pandemic (Lee et al., Citation2020). Internal communication increased job engagement among employees during the pandemic when it is deemed to be transparent (Einwiller et al., Citation2021; Stranzl et al., Citation2021). Overall, this shows that organizational leadership plays a key role in crisis mitigation. In essence, it depicts that management commitment can be an important predictor of internal crisis communication.

During the time of uncertainty, no clear meaning can evolve from a crisis situation (Carroll, Citation2015). In such a situation of uncertainty, organizational members sudden loss meaningful reaction to engage in (Heide & Simonsson, Citation2021). Hence, retrospective sensemaking theory focusing on situations where organizational sensemaking breaks down in a crisis event (Weick, Citation1979, Citation1988, Citation1993), where need for sensemaking is critical and important in guiding internal crisis communication (Frandsen & Johansen, Citation2011). On this note, Frandsen and Johansen (Citation2011) hypothesise that why employees perceive or unable to perceive plethora of organizational crises and how their crisis perception is affected by organizational factors is worth exploration and beneficial to the development of internal crisis communication literature. Noting the compelling nature of this emphasis, this study therefore examined the relationship between internal crisis communication and crisis perception. Hence, this study aims to explain the relationship between safety culture, supportive environment, and management commitment and internal crisis communication as well as its impact on employee crisis perception.

2.4. Antecedents of Internal Crisis Communication

2.4.1. Safety Culture

For safety management, safety minded industries which are classified as high-risk industries need a frequent safety culture assessment to identify developments that are both critical and useful (Noort et al., Citation2016). More importantly, the fast importance of employee health and safety and the continued improvement standards have resulted to widespread focus on safety culture (Mohamad et al., Citation2022; Seymen & Bolat, Citation2010). Safety culture is considered to be the values, norms and practices shared by groups in relation to risk and safety (Cooper, Citation2000). “Safety culture emphasizes that the potential work accidents, job diseases or catastrophic situations are not merely caused by technical or individual mistakes, but are also affected by managers and employees’ perceptions, attitudes and behavior” (Seymen & Bolat, Citation2010).

Similarly, safety culture encompasses broad range of attributes which include communication on risk, incident reporting practices, training of personnel, and can be accessed via several measurement procedures including surveys, observations, focus groups, and incident analyses (Guldenmund, Citation2010; Mearns & Flin, Citation1999). This shows that an organization’s safety culture interacts with its environment and therefore should be considered in the context of internal crisis communication. It is important to note that, high reliability organizations theory emphasize on organizational culture where employees discuss, reflect and focus on risks and misses. This is to demonstrate that effective organizations have strong potentials and capabilities to learn from previous errors, which is an effect of a safety culture (Simonsson & Heide, Citation2018). The backbone to achieve this feat is strategic management thinking and discourse which requires decentralization (Heide & Simonsson, Citation2014). However, the role of internal crisis communication in high-risk industry in enhancing safety culture is to a large extent under-explored.

2.4.2. Supportive Environment

Over a long period of time, organizations have consistently worked on how to create a safe and supportive environment to foster productivity. Past literature also posited that supportive relationships in working environment are the key attribute of efficient organization (Gummer, Citation2001). Employees that relish their organization and like what they are doing in the work environment result to lower malingering, negative events and have a good job satisfaction (Taylor, Citation2008). In fact, supportive environment has been linked to the growth or cultivation of innovative activities (Okhomina, Citation2010). Supportive environment that employees receive from their immediate peers, superiors, and from other departments stimulates the employee outcomes in form of organization commitment and job satisfaction (Kundu & Lata, Citation2017). Factors that encourage supportive environment include information sharing, participation in problem-solving, forgiving, and a favorable caring attitude and friendly environment. This makes the employees to feel indebted and committed and the feelings of indebtedness and belongingness force them to remain with the organization to reciprocate a supportive environment (Naz et al., Citation2020).Therefore, this study adds to the extant literature by bringing a communication point of view to supportive environment study in the context of internal crisis communication. This study therefore proposed that supportive environment will enhance internal crisis communication.

2.4.3. Management Commitment

A number of scholars have demonstrated that top management play an important role in executing sustainability strategies (e.g., Akanmu et al., Citation2021), as such decisions involve resource commitment and organisational changes (Bansal & Roth, Citation2000; Wijethilake & Lama, Citation2019). Top management commitment has been recognized to include the ability of managers to demonstrate “strategic policies and goals establishment, providing training and resources that lower level workers need to achieve the goals, implementing those goals to lower levels of organizations, rewarding those who have performed well, participating in different work teams, reviewing progress and revising and aligning the existing policies to strategic and long-term objectives” (Majid et al., Citation2019). The top management of the organizations ensures that there is integration between business processes within the company with external and internal parties of the company (Leksono et al., Citation2020).

Past studies have highlighted the importance of investigating employee behaviors influenced by management commitment (Babakus et al., Citation2003). For instance, literature has demonstrated that effective policies implementation depends on the level of top management commitment; the stronger the commitment, the greater the potential for successful implementation of the policy (Rodgers et al., Citation1993). Therefore, management of an organization most show concern and caring toward their employees in times of crisis to trigger this impulse. Although the relationship between management commitment and other employee outcomes has been empirical tested, this managerial aspect has not been explored in the context of internal crisis communication. Drawing from network theory, this will show the value in understanding intra-organizational relationships across an organization during a crisis (Taylor, Citation2010).

2.5. Consequence of Internal Crisis Communication

2.5.1. Crisis Perception

According to Heider (Citation1958), any event, action or occurrence can give rise to search for the cause. Understanding the cause of the event is what is characterized as attribution for events (Weiner, Citation2008). Attribution is the internal and external process of interpreting and understanding what is behind human’s behaviors (Manusov & Spitzberg, Citation2008). It can be seen from the above analysis that, the literature on crisis perception draws its impetus from attribution theory. Results from earlier studies demonstrate an association between an organisation’s effectiveness in its crisis perception and its capacity to analyse the environment and detect and share the relevant signal (Snoeijers & Poels, Citation2018). This highlights that both internal and external stakeholders play a significant role in understanding a crisis situation. In the same manner, Billings et al. (Citation1980) identified that a situation must be noticed, treated and evaluated against normality before the organisation perceives it as a crisis. Past studies have shown that sufficient information and effective communication from the management, permit information to flow through the organization rapidly and provide up-to-date information to the stakeholders (Chan, Citation2020). Similarly, other studies have found that perception is capable to influence the level at which an organization is eager to have engagement on activities of crisis management (Penrose, Citation2000).

Similarly, Sense-making theory has played a very important role in providing information on individual information perception and interpretation (Weick, Citation1988). The premise of this theory is that individuals associate meaning to their own situation based on previous experience and by creating a personal frame in which their actions make sense (Weick, Citation1988, Citation1993). This attribute has been aligned with the factors that are essential for effective internal crisis communication (Frandsen & Johansen, Citation2011). Therefore, this study intends to investigate the relationship between internal crisis communication and crisis perception from employee perspective of Malaysian high-risk industry.

3. Research Methodology

A comprehensive literature review is conducted from numerous academic and article journals to examine the antecedents and consequences of ICC. It was observed that the relationships were not properly developed. Therefore, qualitative interviews with practitioners working in high risk industry were conducted to establish construct equivalence and to ensure that the concepts serve similar function in the organization involved in this research.

In Malaysia, face-to-face interviews were conducted in November 2019 to January 2020. From the 15 selected practitioners among the engineers, human resources managers and senior managers in the oil and gas industry, only nine agreed to participate in the interview as shown in Table . Four site engineers of Oil and Gas-related companies in Malaysia, and five senior managers who have once involved in training and planning for crisis management are the respondents. The respondents were selected based on purposeful sampling as they are knowledgeable and experienced in that field. Other potential respondents were not available because they were out of the station during the course of the interview. However, for this study, the 60 percent feedback rate is sufficient to generate information across the industry.

Table 1. Profile of interviewees (engineers and senior managers)

Throughout the collection phase of the data, interview procedures and protocols were used. The guidelines suggested by Easterby-Smith et al. (Citation1991) are followed to prepare the semi-structured interview. For accurate answers to the questions, the respondents were given space and time to reply. English language is the mode of communication for the interview as the respondents are all in business sector and are assumed to be proficient in the language (Lim, Citation2001). Following the policies of some companies, the personal information of some respondents (such as names of the organization and the respondents) are kept confidential upon their requests and such request are always protected at all time.

A transcription of the audio interview to text was initiated for the process of analyzing the data. Using themes and keywords, the data (in-depth interviews) were classified using deductive content analysis (Hinkin, Citation1995; Krippendorff, Citation1980). It was feasible to extract meaningful and segmented information and generate a tree map that tagged and branched the data by grouping sources and coding data with NVivo 12.0 software. According to Gibbs (Citation2002), the use of Nvivo makes data analysis easier, more reliable, accurate and transparent. The word cloud analysis was employed when the material was too variable in content or lacked sufficient instances to detect patterns, resulting in coding issues. Various antecedents and consequences of ICC were revealed based on the coding. To simplify the reproduction and analysis, the informants’ comments were transcribed while some new themes and aspects showed up during the analysis. The key findings on the definition and conceptualization of the constructs of ICC were then presented.

4. Results and Discussion

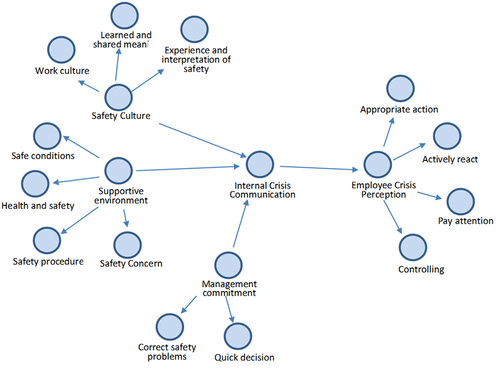

Various codes and categories were used to classify and categorise the focal data. These codes might be unstructured or organised into categories. In this study however, similar identifiers were used to categorise relevant data, while fresh information spurred the creation of additional categories. Notably, the antecedents and consequence of the ICC were the most discussed topics. Figure depicts informants’ perceptions of the antecedents and consequence of the ICC.

Apparently, the study revealed that ICC is associated with a safety culture, a supportive environment, and management commitment. Informants recognised that these factors might make the ICC important in any high-risk industry. In addition, the ICC was shown to be closely associated with employee crisis perceptions as a consequence. The following section discusses in details the antecedents and consequences of ICC and uses informant quotes to illustrate the five main nodes identified in the Figure .

4.1. The Antecedents of ICC

4.1.1. Safety Culture

According to Frandsen and Johansen (Citation2011), one of the important organizational factors identified by a researcher that has great influence on internal crisis communication is safety culture. Safety culture is a subdivision of organizational culture with an emotional impact on the behavior and attitudes of the employees in regards to the ongoing safety and health performance in their organizations (Cooper, Citation2000).

According to Richter and Koch (Citation2004), safety culture is the learned and shared meanings, experience and interpretation of safety and work which guide the actions of the people towards accidents, risks and prevention. It means the managers and employees are working together in order to create a conducive environment in the workplace. The definition is in line with the practice of safety culture in the high-risk industry. The results from the interview findings reveal that there is a strong parallel between present practice in the literature and high-risk industry. For instance, one of informant (Informant 3#) stated that “Safety culture is ingrained in every employee and that safety is number one; any meeting should start with safety briefing and sharing first […]. Any incident is recorded and shared and the lesson is learnt. We have monthly meeting and annual global meeting on safety where all the countries build up just to talk about safety, the safety incident that happened throughout the year, the learning and sharing and new things they can share with others”.

To support the safety culture practices in a high-risk workplace, informant 8 emphasized on learned and shared meanings, experience and interpretation of safety and work culture (Informant 8#): “In our organization, safety culture always comes up with safety briefing and safety timing in or outside of the office. […] we want the crew to follow our safety culture and rules. When they come to work with us they need to follow the rules. We give them the awareness during the safety briefing; we come up with the formalization”.

The result also shows that safety culture has a strong correlation with ICC. The majority of informants agreed that safety culture is the one of ICC determinants. One interviewee [Informant #8] explained: “Internal communication between employees to employee is very good; and between top management and employee is also good. When we have good communication with each other, safety is assured and performance will also be good. If we do not have good communication, how do we communicate safety culture; it all goes back to internal communication”. The informant 9# also made similar statement: “Crisis communication happens when there is crisis; safety culture is a way to prevent crisis from happening. So, if they put good safety culture in place, so most likely crisis wouldn’t occur. Anyway, even in a safer environment, sometimes accident happens that we cannot prevent. Whether you have a good safety culture or not, you still have to put crisis communication into consideration in case you have to use it”. This statement indicates that safety culture is the main antecedent of ICC framework in high-risk industry. This is supported by Frandsen and Johansen (Citation2011) that reveals a strong connection between safety culture and the organization capacity to address a crisis.

However, one of the informants (Informant 3#) from the international Oil and Gas companies has a different perspective. He believes safety culture and ICC has an indirect relation: “It doesn’t connect directly; it may contribute indirectly. Even without crisis, we normally talk about safety a lot. If there is any safety incident, there will be a stand-up communication from the management to the workers to talk about the crisis. That is where I see the connection [.]”. This statement can be justified based on the intangible corporate culture behavior. As highlighted by Turner et al. (Citation1989), safety culture not only associated with technical and social practices but includes intangible factors such as beliefs, norms and attitudes.

4.1.2. Supportive Environment

The internal environment of an organization is the determinant factor of a successful organization (Kazmi & Naaranoja, Citation2015). Therefore, the ability of management to form supportive environment will increase the commitment among the employees (Taylor, Citation2008). According to Hofmann and Morgeson (Citation1999) and Mearns and Hope (Citation2005), supportive environment indicates to the employees that they are valued and that the organization is committed to them. It includes the management effort to create a safe conditions, health and safety, safety procedures, safety concerns and on how to work safely. Therefore, some of the informants believed that supportive environment is important for the high-risk industry. One informant [informant #5] commented: “[.] How the management tries to make it a safe and comfortable place for me to work. I wouldn’t say stress-free, but for me, at least they put in effort to make it easy for me to do my job. My colleagues are always very concern; they always take the time to reach others and motivate each other to be careful and we have practices for all the time I have been working here”. This statement is supported by another informant [informant #9] who reiterated the role of management to create supportive environment: “In my company, it is very easier because we always go to our employees, if they have any concern or any suggestion for us to improve, they can always come to us. So, we do consider their suggestion and concern. That’s what I mean by supportive environment. We do always practice open door policy. The employees can come directly to us and to ask us for anything”.

In addition, the informants also highlighted the connection between supportive environment and ICC. One of the key informants [informant #9] insisted: “when the employees want to come to the managers, it depends on the attitude of the managers […] if anything happens at the end of the operation, they will chose to act as if nothing happens and communication can be broken down. The important thing is to maintain good relationship between the manager and the employees so that you will know what they are doing and vice versa and relay correct information”. While another informant [informant #6] pointed out: “supportive environment means you have conductive environment where people working have a sense of ownership; if they see something wrong, they will be very transparent (communication). People working there will be inclined”.

The findings show the majority of key informants agreed that the supportive environment is a key factor for a successful organization. The positive environment will create a good communication and interaction between the managers and the employees in a crisis situation. Therefore, the supportive environment should be included as main strategic management in a high-risk industry to prevent miscommunication among the employees.

4.1.3. Management Commitment

The top management commitment and visible leadership can improve the quality of relationship between employees (Babakus et al., Citation2003; Mohamad et al., Citation2022) and can influence the attitude of the employees (Michael et al., Citation2005). Management commitments are defined on how committed managements are to safety (Jones, Citation2014). It is translated to action needed to be taken to correct safety problems, quick decision when a safety concern is raised and to ensure the safety procedures. One informant [informant #9] commented: “You have corrective action; you have concern, management responses and improvement. For me, that really says many things about management commitment. […] For me, the organization needs to take serious the care of their employees. It is really up to the bonding of the employees and the management as well”. This statement also is supported by other informant (informant #2): “As part of the management team, we do value our staff as a very big asset to the company. It is the management responsibility to provide and to ensure that the crew understand the importance of safety and comply with the safety. If the management can do things without the support from the bottom line, that means something is wrong as you can plan and do the procedure but without the leg and arm of the organization, things cannot be successful”.

Many informants believe that management commitments are highly correlated with ICC. The informant from project Management Company iterated by saying [informant #8]: “For ICC, it is very connected to top management; if the management does not give commitment to any crisis that happen, how can we deal with it? They should work together to solve it. Luckily, our management is very good; if any incident, even at small scale happens, they will support and attend the meeting and discuss how to solve the problem”. Additionally, one informant [informant #6] made mentioned of the importance of building a good employee communication: “when there is crisis, there is anxiety and fear. It is very important for the boss to manage the certainties and uncertainties. Management commitment in terms of commitment to ICC involves how the manager sends the message down to everyone. The management just have to send the correct message to everyone”.

The management commitment is considered to be an important role as it is an underlying factor for ICC construct. In fact, in crisis management, the organizations need a top management commitment for crisis planning to protect the organization from the crisis (Jaques, Citation2007). According to the findings from the above analyses, this study shows that management commitment strengthens communication with the internal stakeholder (employees) in high-risk industry.

4.2. The Consequences of ICC

4.2.1. Employee Crisis Perception

Billings et al. (Citation1980) and Smart and Vertinsky (Citation1977) reported that employee crisis perception is the way of defining a situation as a crisis to be important to understand as it affects the processes of decision-making in both dysfunctional and functional ways. For instance, decision maker’s perception of a crisis of an individual is related to the organizational response in several ways. A key organizational member may see a crisis and then have to cause others to share that perception before the organization will respond. This sequence of events would involve such interpersonal processes as persuasion, power, coalition formation, and bargaining (Billings et al., Citation1980).

To understand the definition of employee crisis response in this specific context (high-risk industry), the qualitative interview reveals an interesting finding. Another informant [informant #6] stated that management played important roles in controlling the employee response on crisis: “If something happens, we will be anxious and worried but we will be very afraid when we know something is wrong. Different people will perceive the severity of every situation differently. Not everyone has the same financial situation or living situation. Irrespective of the situation, the management is forthcoming”. Meanwhile one senior manager at international oil company [Informant #3] added: “I think you should add in ‘post-crisis action’ because that is how the employee sees the management is trying to stop the reoccurrence of the incident. If it just stuck, then the action is not perceived by the employees as genuine. Then in the future, they will know management is serious and have carried out the action before. If they do not see that, they only see it as communication with no sense of responsibility from the management”.

In relations to the consequences of ICC, the majority of informants confirmed that employee crisis response must be one of the important variables. One of the key informants involved in Oil and Gas industry [informant #9] insisted: “When the organization does not take good care of the employee concern, it will reduce the bonding between the employee and the management. So, as a management, we have to find a way to reduce that gap. Everyone must feel that they are part of the organization. If they feel they are part of it, they will establish a good communication link between employee and the organization”. While another informant [informant #3] pointed out: “The Company is serious about crisis. If crisis happens, every work needs to stop because everyone (employees) needs to talk about it and learn from it before we can continue or resume to work. They need internal crisis communication to go through it first, learn and then resume. So, that shows how important it is”.

The results stated above are in line with the past researches. As an outcome, Billings et al. (Citation1980) and Lee (Citation2019) found that employee crisis perception can bring effective internal crisis communication. It is quite predictable that the continuing internal communication between management and employees during crisis will positively affect employees’ perception. The qualitative study clearly emphasized the role of ICC in shaping employee crisis perception in the context of high-risk industry.

Summarily, all the key informants (managers and engineers) have the same understanding on the operational concept of ICC and they all gave comprehensive explanation based on their experiences in high-risk industry specifically the oil and gas-related company (see Figure ). For instance, the key informants highlighted two main concepts of ICC: (1) the communication before, during and after a crisis; and (2) importance of communication between management and employee in a situation of crisis. The informants not only pointed out the operational concept of the ICC in the specific contexts but also discussed the antecedents and consequences of ICC. The increasing awareness and the forcing factors by the regulators in high-risk industry might lead to an intensification of safety culture, supportive environment and management commitment for the oil and gas related industries in consideration of a more comprehensive ICC activities. In furtherance, the tracks of the ICC activities of an organization are advised to be kept by the managers and be accordingly prepared for future consultation. Most importantly, managers are advised to consider the consequences of ICC on the crisis perception among the employees.

4.3. Research Implications

4.3.1. Academic Implication

This study was carried out on the basis of two principal gaps. First, the previous studies have highlighted a paucity of literature on the ICC and a lack of theoretical advancement (Adamu et al., Citation2016; Frandsen & Johansen, Citation2011; Heide & Simonsson, Citation2019; Ravazzani, Citation2016). In addition, the employees (internal stakeholder) have not been given adequate attention in the research area of crisis communication (Adamu et al., Citation2018; Kim, Citation2018; Strandberg & Vigsø, Citation2016). Also, the framework of ICC in high-risk industry addresses the antecedents and consequences as limitation that were yet to be attended to in the past literature. These researches thus lead to the study of ICC within the context of the Malaysian high-risk industry and help practitioners to understand the domain as related internal crisis communication and its underlying variables.

Furthermore, the study findings suggest that any Western theory application should be contextualized when analyzing a similar phenomenon in Malaysia. Furthermore, not all reported contexts in the past studies are applicable to the Malaysian context. This study however has shown that such concept can also be applied from management research point of view. This study focused on the perspectives of the internal stakeholder (employee) to get a deeper understanding of the functions of ICC. Thus, conception of ICC then became the focus of this research. The results help safety managers and practitioners to recognize the realistic needs for enhancing awareness about ICC.

In addition, one significant contribution of this study is the validation of the ICC framework consisting variables of antecedents and consequences in high-risk industry of Malaysia. Understanding the ICC framework for better safety planning is advantageous for the high-risk industry. This study can proffer assistance to the managers and engineers on how to make use of the best practice of ICC that are suitable for the companies.

4.3.2. Managerial Implication

The basis of recommendations for the managers and engineers in high-risk industry is the number of the managerial implications deduced from the results. Some guidance are outlined for ICC programs provided in this study.

First, there has been rapid development of Malaysian high-risk industries like the oil and gas industries and the commercial aviation. As a result, the high-risk player in the industry needs to understand the current global and regional market, where Malaysian industry needs to develop a corporate reputation through managing excellence crisis communication. The knowledge in crisis communication and the challenge of creating an ICC framework are of great interest to the industry player because of this development. The high-risk relevant companies find this useful in understanding the factors that lead to the enhancement of the practices of the ICC and its effects on performances. For instance, the outcome of this study can serve as reliable information for the high-risk companies to work consciously harder in order to improve and reinforce ICC to have better practices with the internal stakeholders i.e. the employees. More attention should be given to the underlying variables of ICC such as safety culture, supportive environments, and management commitment and employee crisis perception as they proved to have significant effects on organizational performance.

Also, the study found that ICC is an important tool for helping the professional status of organizations by maintaining and enhancing their corporate reputation and providing the organization with an immense competitive edge. Hence, ICC is considered to be an important competitive tool for supporting organizations in pursuing strategic goals and objectives of business. This study shows that strategic functions of ICC is a contribution to those elements of organizational system.

4.4. Limitation of the Study

The emphasis of this analysis is mainly on the expansion and comprehension of ICC constructs and their underlying variables. Despite the usefulness of the attempt, there are some limitation worth discussing.

First, a small number of respondents (9 informants) were used for this qualitative study where the informants are not enough to represent all the 16 categories of the companies under oil and gas industry. Although, the researcher made an attempt to contact 16 respondents that represent all the categories of the companies in the early stage but interviews were conducted for only 9 informants. If the qualitative study has included all the informants from all the categories, the result could be more diverse. Also, there is limited available researches; therefore, it can be safely concluded that this is the first study to examine the constructs of ICC and its framework. However, some important variables might not be included in the research framework or wrong variables might have been added in the framework.

In addition, the organizational attitude and behavior of oil and gas industry cannot be generalised to other types of high-risk industry such as aviation and construction. There is limited understanding of ICC in the findings of this study only from the views of the engineers and managers from the selected category of the high-risk companies. An empirical research will be more practical if it is considered on different types of organization as the results cannot be safely generalized to other sectors. The limitation in this study however does not reduce the quality and contribution of the outcomes. Thus, it gives an insight on the future direction when considering improvement in the area of that research.

5. Conclusion and Recommendation

5.1. Conclusion

The comprehensive findings of this study affirm the validity of the roles of ICC in one of the high-risk industries (oil and gas) in Malaysia. Therefore, the results are said to be sound and in line with the literature based on the discussion of the conceptualization and operational definitions of the constructs of the ICC. Evidently, most of the underpinning variables that strengthen the rationale of future qualitative testing of the proposed relationship are supported by these findings. Also, most of the respondents expected ICC to be determined by safety culture, supportive environment and management commitment. The informants are optimistic and positive on the future development of ICC in Malaysia specifically its applicability and practices in high-risk industries. Finally, ICC is considered by majority of informants to be applicable in all facets of crises management and is seen as tool of management and valuable element to an organization.

5.2. Future Research and Recommendation

From the limitations discussed in the previous section, recommendations are made to suggest future researches in order to elaborate the existing literature on ICC. First, this study examined empirically ICC in high-risk industry with qualitative approach which happened to be the first of its type in Malaysia. Despite the increase in attention on the interest to study more on crisis communication in the past two decades, the limitation in the empirical and systematic research on ICC calls for more attention. Notably, the result of this study can be different when considering other contexts or sectors as this study only investigated ICC in high-risk industry specifically, Malaysian oil and gas companies. Therefore, replication of the context of this study can be done to other sector to confirm the generalizability of the results in other contexts such as country and another industry such as construction or aviation.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about a crucial organizational concern and survival necessity which its bottom line is to ensure continuous job engagement among employees (Stranzl et al., Citation2021). Oil and gas and Aviation industry volatility during global pandemic has been also exposed. How do these high reliability organizations apply internal crisis communication to increase job engagement during the pandemic will be interesting for future studies? In the same vein, effective crisis leadership in a pandemic crisis is shown to be more democratic and collaborative (Heide & Simonsson, Citation2021). In such organizations that require employees to be aware from workstation all the time, examining the collaborative leadership style applied by the management will be beneficial to internal crisis communication literature. According to Coombs (Citation2020), studying crisis cases is one way to learn more about crisis management and communication. As employees are required to develop an agile mindset as a consequence of the pandemic. Many organizations have adopted unexpected standard routine in order to continue to survive the pandemic situation. Exploring the relationship between the indicators and consequences of internal crisis communication as an extension to the research within the domain of crisis communication and management is therefore highly needed.

Similarly, about nine Malaysian companies under oil and gas industry are considered in this study. The results have indicated general conceptualization of ICC for that particular settings (oil and gas industry) only. Another distinctive outcome can be revealed if the research focuses on other types of high-risk companies. For example, the aviation company has different stakeholders (mainly customers) and interest in comparison with oil and gas (mainly employees) which can affect the overall concept of ICC. Future researches can consider the outcome of this study for a specific high-risk industry to know if it differs from the combinations of all other high-risk industries. The consideration of this new approach can offer more insights into the roles of ICC in a specific industry which is more appropriate to practice by the company in that particular industry.

Public Interest Statement_30_09_2023.docx

Download MS Word (12.5 KB)About the authors 30_09_2023.docx

Download MS Word (14.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2281699

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bahtiar Mohamad

Bahtiar Mohamad is an Associate Professor of Corporate Communication and Strategy at Othman Yeop Abdullah Graduate School of Business (OYAGSB), Universiti Utara Malaysia. He is carrying out research and publication in the area of corporate identity, corporate image, crisis communication and corporate branding from the point of view of public relations and corporate communication.

Adamu Abbas Adamu

Adamu Abbas Adamu is Lecturer of Public Relations in the Department of Marketing, Curtin University Malaysia. His research interests are public relations in general, in particular, internal crisis communication, artificial intelligence in public relations and scale development.

Muslim Diekola Akanmu

Muslim Diekola Akanmu is a postdoctoral fellow at the Johannesburg Business School, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. He is a graduate member of Nigeria Society of Engineers (NSE), an affiliate member of Malaysian Institute of Management (MIM) and an associate member of Malaysian Society for Engineering (AMSET).

References

- Abbas, A., Ekowati, D., & Suhariadi, F. (2021). Managing individuals and organizations through leadership: Diversity consciousness roadmap. In Handbook of research on applied social psychology in multiculturalism (pp. 47–19). IGI Global.

- Abbas, A., Saud, M., Ekowati, D., Usman, I., & Suhariadi, F. (2020). Servant leadership a strategic choice for organizational performance. An empirical discussion from Pakistan. International Journal of Productivity and Quality Management, 34(4), 468–485. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPQM.2021.120599

- Abbas, A., Saud, M., Suhariadi, F., Usman, I., & Ekowati, D. (2020). Positive leadership psychology: Authentic and servant leadership in higher education in Pakistan. Current Psychology, 41(9), 5859–5871. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01051-1

- Abdullah, A., & Lim, L. (2001). Cultural dimensions of Anglos, Australians and Malaysian. Malaysian Management Review, 36(2), 1–17.

- Abu Bakar, H., Halim, H., Mustaffa, C. S., & Mohamad, B. (2016). Relationships differentiation: Cross-ethnic comparisons in the Malaysian workplace. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 45(2), 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2016.1140672

- Adamu, A. A., & Mohamad, B. (2019a). Developing a strategic model of internal crisis communication: Empirical evidence from Nigeria. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 13(3), 233–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2019.1629935

- Adamu, A. A., & Mohamad, B. (2019b). A reliable and valid measurement scale for assessing internal crisis communication. Journal of Communication Management, 23(2), 90–108. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-07-2018-0068

- Adamu, A. A., Mohamad, B., & Rahman, N. A. A. (2016). Antecedents of internal crisis communication and its consequences on employee performance. International Review of Management and Marketing, 6(7S), 33–41.

- Adamu, A. A., Mohamad, B., & Rahman, N. A. A. (2018). Towards measuring internal crisis communication. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 28(1), 107–128. https://doi.org/10.1075/japc.00006.ada

- Akanmu, M. D., Hassan, M. G., Mohamad, B., & Nordin, N. (2021). Sustainability through TQM practices in the food and beverages industry. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 40(2), 335–364. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-05-2021-0143

- Andersson, R. (2020). Strategic communication at the organizational frontline: Towards a better understanding of employees as communicators [ Doctoral dissertation, Lund University].

- Babakus, E., Yavas, U., Karatepe, O. M., & Avci, T. (2003). The effect of management commitment to service quality on employees’ affective and performance outcomes. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31(3), 272–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070303031003005

- Bansal, P., & Roth, K. (2000). Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 717–736. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556363

- Billings, R. S., Milburn, T. W., & Schaalman, M. L. (1980). A model of crisis perception: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 25(2), 300–316. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392456

- Björck, A., & Barthelmess, P. (2019). Internal crisis communication and corporate culture: Forging the links. Proceedings of the Fifth International Scientific Conference Knowledge Based Sustainable Development Conference, Budapest, Hungary (pp.215–222).

- Boyacigiller, N., & Adler, N. (1991). The parochial dinosaur: organisational science in a global context. Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 262–290. https://doi.org/10.2307/258862

- Carroll, J. S. (2015). Making sense of ambiguity through dialogue and collaborative action. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 23(2), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12075

- Chan, C. (2020), The role of communications in crisis management in public administration [ Doctoral dissertation, California State University].

- Coombs, W. T. (2015). The value of communication during a crisis: Insights from strategic communication research. Business Horizons, 58(2), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2014.10.003

- Coombs, W. T. (2020). Public sector crises: Realizations from COVID-19 for crisis communication. Partecipazione e Conflitto, 13(2), 990–1001.

- Cooper, M. D. (2000). Towards a model of safety culture. Safety Science, 36(2), 111–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-7535(00)00035-7

- Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R., & Lowe, A. (1991). Management research: An introduction (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Ecklebe, S., & Löffler, N. (2021). A question of quality: Perceptions of internal communication during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. Journal of Communication Management, 25(3), 214–232. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-09-2020-0101

- Einwiller, S., Ruppel, C., & Stranzl, J. (2021). Achieving employee support during the COVID-19 pandemic–the role of relational and informational crisis communication in Austrian nizations. Journal of Communication Management, 25(3), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-10-2020-0107

- Frandsen, F., & Johansen, W. (2011). The study of internal crisis communication: Towards an integrative framework. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 16(4), 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563281111186977

- Gibbs, G. (2002). Qualitative data analysis: Explorations with NVivo. Open University Press.

- Guldenmund, F. W. (2010). Understanding and exploring safety culture. Delft University of Technology.

- Gummer, B. (2001). Peer relationships in organizations: Mutual assistance, employees with disabilities, and distributive justice. Administration in Social Work, 25(4), 85–103. https://doi.org/10.1300/J147v25n04_05

- Heide, M. (2013). Internal crisis communication–the future of crisis management. In Handbuch Krisenmanagement (pp. 195–209). Springer VS.

- Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. Wiley.

- Heide, M., & Simonsson, C. (2011). Putting coworkers in the limelight: New challenges for communication professionals. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 5(4), 201–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2011.605777

- Heide, M., & Simonsson, C. (2013). Errors in organizations: Opportunities for crisis management. Proceedings of the Conference on Corporate Communication 2013.

- Heide, M., & Simonsson, C. (2014). Developing internal crisis communication. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 9(2), 128–146. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-09-2012-0063

- Heide, M., & Simonsson, C. (2015). Struggling with internal crisis communication: A balancing act between paradoxical tensions. Public Relations Inquiry, 4(2), 223–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/2046147X15570108

- Heide, M., & Simonsson, C. (2019). Internal crisis communication: Crisis awareness, leadership and Coworkership. Routledge.

- Heide, M., & Simonsson, C. (2020). 12 internal crisis communication: On current and future research. In Crisis communication (pp. 259–278). De Gruyter Mouton.

- Heide, M., & Simonsson, C. (2021). What was that all about? On internal crisis communication and communicative coworkership during a pandemic. Journal of Communication Management, 25(3), 256–275. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-09-2020-0105

- Hinkin, T. R. (1995). A review of scale development practices in the study of organisations. Journal of Management, 21(5), 967–988. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639502100509

- Hofmann, D. A., & Morgeson, F. P. (1999). Safety-related behavior as a social exchange: The role of perceived organizational support and leader–member exchange. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(2), 286–296. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.2.286

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Sage.

- Hussain, S. T., Lei, S., Akram, T., Haider, M. J., Hussain, S. H., & Ali, M. (2018). Kurt Lewin’s change model: A critical review of the role of leadership and employee involvement in organizational change. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 3(3), 123–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2016.07.002

- Jaques, T. (2007). Issue management and crisis management: An integrated, non-linear, relational construct. Public Relations Review, 33(2), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2007.02.001

- Johansen, W., Aggerholm, H. K., & Frandsen, F. (2012). Entering new territory: A study of internal crisis management and crisis communication in organizations. Public Relations Review, 38(2), 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2011.11.008

- Jones, M. (2014). Sustainable event management: A practical guide. Routledge.

- Kazmi, S. A. Z., & Naaranoja, M. (2015). Cultivating strategic thinking in organizational leaders by designing supportive work environment. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 181, 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.864

- Kim, Y. (2018). Enhancing employee communication behaviors for sensemaking and sensegiving in crisis situations: Strategic management approach for effective internal crisis communication. Journal of Communication Management, 22(4), 451–475. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-03-2018-0025

- Kim, Y. (2020). Organizational resilience and employee work-role performance after a crisis situation: Exploring the effects of organizational resilience on internal crisis communication. Journal of Public Relations Research, 32(1–2), 47–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2020.1765368

- Kim, Y., & Lim, H. (2020). Activating constructive employee behavioural responses in a crisis: Examining the effects of pre‐crisis reputation and crisis communication strategies on employee voice behaviours. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 28(2), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12289

- Krippendorff, K. (1980). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage Publications.

- Kundu, S. C., & Lata, K. (2017). Effects of supportive work environment on employee retention. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 25(4), 703–722. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-12-2016-1100

- Lee, Y. (2019). Crisis perceptions, relationship, and communicative behaviors of employees: Internal public segmentation approach. Public Relations Review, 45(4), 101832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2019.101832

- Lee, Y., & Kim, K. H. (2021). Enhancing employee advocacy on social media: The value of internal relationship management approach. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 26(2), 311–327. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-05-2020-0088

- Lee, Y., Tao, W., Li, J. Y. Q., & Sun, R. (2020). Enhancing employees’ knowledge sharing through diversity-oriented leadership and strategic internal communication during the COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Knowledge Management, 25(6), 1526–1549. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-06-2020-0483

- Leksono, F. D., Siagian, H., & Oei, S. J. (2020). The effects of top management commitment on operational performance through the use of information Technology and supply chain management practices. Proceedings of the SHS Web of Conferences (Vol. 76, p. 01009). EDP Sciences.

- Lim, L. (2001). Work-related values of malays and Chinese Malaysians. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 1(2), 209–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/147059580112005

- Maitlis, S., & Sonenshein, S. (2010). Sensemaking in crisis and change: Inspiration and insights from Weick (1988). Journal of Management Studies, 47(3), 551–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00908.x

- Majid, A., Yasir, M., Yousaf, Z., & Qudratullah, H. (2019). Role of network capability, structural flexibility and management commitment in defining strategic performance in hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(8), 3077–3096. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2018-0277

- Manusov, V., & Spitzberg, B. H. (2008). Attribution theory: Finding good cause in the search for theory. In L. A. Baxter & D. O. Braithwaite (Eds.), Engaging theories in interpersonal communication: Multiple perspectives (pp. 37–50). Sage Publications.

- Mazzei, A., & Butera, A. (2021). Internal crisis communication. In Current trends and issues in internal communication (pp. 165–181). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mazzei, A., Kim, J.-N., & Dell’oro, C. (2012). Strategic value of employee relationships and communicative actions: Overcoming corporate crisis with quality internal communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 6(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2011.634869

- Mazzei, A., Kim, J. N., Togna, G., Lee, Y., & Lovari, A. (2019). Employees as advocates or adversaries during a corporate crisis: The role of perceived authenticity and employee empowerment. Sinergie Italian Journal of Management, 37(2), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.7433/s109.2019.10

- Mazzei, A., & Ravazzani, S. (2013). Responsible communication with employees to mitigate the negative effects of crises: A study of Italian companies. Proceedings of the International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communication: Responsible Communication (pp. 2–11). IT.

- Mazzei, A., & Ravazzani, S. (2015). Internal crisis communication strategies to protect trust relationships: A study of Italian companies. International Journal of Business Communication, 52(3), 319–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488414525447

- Mearns, K., & Flin, R. (1999). Assessing the state of organizational safety – culture or climate? Current Psychology, 18(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-999-1013-3

- Mearns, K., & Hope, L. (2005). Health and well-being in the offshore environment: The management of personal health. HSE Books.

- Michael, J. H., Evans, D. D., Jansen, K. J., & Haight, J. M. (2005). Management commitment to safety as organizational support: Relationships with non-safety outcomes in wood manufacturing employees. Journal of Safety Research, 36(2), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2005.03.002

- Mohamad, B., Adamu, A. A., & Akanmu, M. D. (2022). Structural model for the antecedents and consequences of internal crisis communication (ICC) in Malaysia oil and gas high risk industry. Sage Open, 12(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221079887

- Mohamad, B., Dauda, S. A., & Halim, H. (2018). Youth offline political participation: Trends and role of social media. Jurnal Komunikasi, Malaysian Journal of Communication, 34(3), 192–207. https://doi.org/10.17576/JKMJC-2018-3403-11

- Mohamad, B., Nguyen, B., Melewar, T. C., & Gambetti, R. (2019). The dimensionality of corporate communication management (CCM) a qualitative study from practitioners’ perspectives in Malaysia. The Bottom Line, 32(1), 71–97. https://doi.org/10.1108/BL-12-2018-0052

- Naz, S., Li, C., Nisar, Q. A., Khan, M. A. S., Ahmad, N., & Anwar, F. (2020). A study in the relationship between supportive work environment and employee retention: Role of organizational commitment and person–organization fit as mediators. Sage Open, 10(2), 2158244020924694. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020924694

- Noort, M. C., Reader, T. W., Shorrock, S., & Kirwan, B. (2016). The relationship between national culture and safety culture: Implications for international safety culture assessments. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 89(3), 515–538. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12139

- Ogbeibu, S., Pereira, V., Burgess, J., Gaskin, J., Emelifeonwu, J., Tarba, S. Y., & Arslan, A. (2021). Responsible innovation in organisations–unpacking the effects of leader trustworthiness and organizational culture on employee creativity. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-021-09784-8

- Ogbeibu, S., Senadjki, A., & Gaskin, J. (2018). The moderating effect of benevolence on the impact of organisational culture on employee creativity. Journal of Business Research, 90, 334–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.05.032

- Okhomina, D. (2010). Entrepreneurial orientation and psychological traits: The moderating influence of supportive environment. Journal of Behavioral Studies in Business, 2, 1–16.

- Olsson, E. K. (2014). Crisis communication in public organisations: Dimensions of crisis communication revisited. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 22(2), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12047

- Palm, J. (2016). Using communication and culture to prevent crisis: A literature Review. Grand Valley State University.

- Peng, T., Peterson, M., & Shyi, Y. (1991). Quantitative method in cross national management research: Trends and equivalence issues. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 12(2), 87–107.

- Penrose, J. M. (2000). The role of perception in crisis planning. Public Relations Review, 26(2), 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0363-8111(00)00038-2

- Ravazzani, S. (2016). Exploring internal crisis communication in multicultural environments: A study among Danish managers. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 21(1), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-02-2015-0011

- Richter, A., & Koch, C. (2004). Integration, differentiation and ambiguity in safety cultures. Safety Science, 42(8), 703–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2003.12.003

- Rodgers, R., Hunter, J. E., & Rogers, D. L. (1993). Influence of top management commitment on management program success. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 151–155. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.151

- Rowley, T. J. (1997). Moving beyond dyadic ties: A network theory of stakeholder influences. The Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 887–910. https://doi.org/10.2307/259248

- Sadri, G., & Lees, B. (2001). Developing corporate culture as a competitive advantage. The Journal of Management Development, 20(10), 853–859. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710110410851

- Samimi, M., Cortes, A. F., Anderson, M. H., & Herrmann, P. (2020). What is strategic leadership? Developing a framework for future research. The Leadership Quarterly, 33(3), 101353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2019.101353

- Sekaran, U. (1981). Are US Organisational concepts and measures transferable to another culture? An empirical investigation. Academy of Management Journal, 24(2), 409–417. https://doi.org/10.2307/255851

- Seymen, O. A., & Bolat, O. I. (2010). The role of national culture in establishing an efficient safety culture in organizations: An evaluation in respect of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. Balikesir University.

- Sia, J. K. M., & Adamu, A. A. (2020). Facing the unknown: Pandemic and higher education in Malaysia. Asian Education and Development Studies, 10(2), 263–275. https://doi.org/10.1108/AEDS-05-2020-0114

- Simonsson, C., & Heide, M. (2018). How focusing positively on errors can help organizations become more communicative: An alternative approach to crisis communication. Journal of Communication Management, 22(2), 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-04-2017-0044

- Smart, C., & Vertinsky, I. (1977). Designs for crisis decision units. Administrative Science Quarterly, 22(2), 640–658. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392406

- Snoeijers, E., & Poels, K. (2018). Factors that influence organisational crisis perception from an internal stakeholder’s point of view. Public Relations Review, 44(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.12.003

- Strandberg, J. M., & Vigsø, O. (2016). Internal crisis communication. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 21(1), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-11-2014-0083

- Stranzl, J., Ruppel, C., & Einwiller, S. (2021). Examining the role of transparent organizational communication for employees’ job engagement and disengagement during the COVID-19 pandemic in Austria. Journal of International Crisis and Risk Communication Research, 4(2), 5. https://doi.org/10.30658/jicrcr.4.2.4

- Taylor, B. (2010). Brand is culture, culture is brand. Harvard Business Review, 27.