Abstract

Management Control Systems (MCS) have become increasingly important for the management of subsidiaries by the parent company. In addition, MCS are influenced by the cultural and organizational axes of both parties (parent company vs. subsidiaries).Therefore, an appropriate balance between these axes is required since there are differences between the country of origin and the host country of the investment. Thus, this study explores the MCS of a subsidiary and the parent company’s influences on it through a case study supported by multiple semi-structured interviews. The results obtained show that the parent company exerts a strong influence on the MCS of the subsidiary. This assertiveness is revealed in the subsidiary’s weak operational and non-operational autonomy as a reflection of the parent company’s organisational culture (country of origin of the investment). The main contribution of this study lies in the country of origin of the parent company (Asia) and in the study of an extractive industry whose end product (tungsten) is a strategic resource for the world. Another contribution is theoretical and related to the new institutional sociology. This theory recognizes the normative and cultural issues of organizations as essential and sees management accounting practices and management control systems as the result of internal and external pressures, as well as the growing importance given to the norms, beliefs, and values of stakeholders within the organization and the organizational environment itself. The use of the Flamholtz model applied to the mining sector also fills a gap identified in the literature.

1. Introduction

The relevance of planning, organising, and controlling has assumed a more relevant and vital role in organisations’ management process (Bedeian & Giglioni, Citation1974). Over time, management control has been defined from various perspectives (Flamholtz et al., Citation1985). The sociological perspective highlights the organisation as a whole and emphasises the importance of groups (Flamholtz et al., Citation1985; Thompson, Citation1967; Weber, Citation1947); the administrative perspective focused on the individual and departments within the organisation (Davis, Citation1940) and the psychological perspective that is relevant to the individual, namely his behaviour concerning groups and the objectives of the organisation (Flamholtz, Citation1979; Flamholtz et al., Citation1985).

Control has been defined in various ways using different concepts (e.g. power, authority, influence) over time (Mitter et al., Citation2023; Tannenbaum, Citation1962). Several authors have also studied the concept of management control (Bedeian & Giglioni, Citation1974; Straub & Zecher, Citation2013). Consequently, it can be seen that the focus of management control has evolved from a vision more focused on formal control and financial information to a more comprehensive vision that includes social and cultural controls (Simons & Simons, Citation1995), the choice of which is influenced by the institutional environment and the strategy to adopt (Collier, Citation2005). Management control has various meanings and has been interpreted in various ways (Ouchi, Citation1979; Sageder & Feldbauer-Durstmüller, Citation2019). Thus, for Etzioni (Citation1965), control is linked to power issues in the organisation; but according to Ouchi (Citation1979) the predominant view is to interpret control as the sum of the interpersonal relationships of influence in the organisation; finally, control can still be treated as an issue related to the flow of information Ouchi (Citation1979). Ouchi and Maguire (Citation1975) argued that control is related to creating rules and monitoring through a hierarchical system. The importance of control stems from the fact that any controlled act has two implications: one pragmatic and the other symbolic (Tannenbaum, Citation1962).

Pragmatics translates into what a person has to do or does not have to do. The symbolism comes from the meaning attributed to what is done. In the organisational context, the exercise of control has an emotional charge (Tannenbaum, Citation1962) that must be taken into account. Following this work, Ouchi (Citation1975, 1977a, 1977b, Ouchi, Citation1979) presents the control system divided into three types (market, bureaucracy and clan). Flamholtz et al. (Citation1985) so as Flamholtz (Citation1996) have shown that control plays an essential role in the management of the organisation and that it has a significant impact on the behaviour of the individuals within it; they also add that control, in the long run, can become a competitive advantage.

After this brief contextualization of the subject to be studied, it should be noted that the theoretical framework is an institutional theory, in particular the new institutional sociology, which was developed in the late 1970s based on various applications of system theories open to organisations and on the premise that the environment affected organisational practices (Leite, Citation2015). This theory holds that they assimilated the practices adopted by organisations due to a cultural process and not only as a formal means to improve their efficiency (Leite, Citation2015). On the other hand, it is premised on using structures and processes that are legitimised and standardised and part of an integrated whole. It approaches the MCS as a set of management practices and a mode of control per se and studies the parties involved’ organisational relationships. This means that this study fits into the new institutional sociology, according to which the change in management control practices may not only be related to economic aspects but also to external pressures from the environment surrounding the organisations and the search for legitimacy before the various stakeholders, as well as the implementation of less formal controls related to organisational culture and to the type of relationships between the parent company and the subsidiaries.

According to Mitter et al. (Citation2023) and Malmi et al. (Citation2020), a wide range of topics, perspectives, and research questions have been addressed in previous studies that address culture as a relevant factor under different theoretical lenses. Although the literature on MCS is extensive, there are still some gaps in it, for example, Brenner and Ambos (Citation2013a) argued that there is limited attention to the importance of social control, suggesting that it is important for the acceptance and legitimisation of other controls, such as expatriates; Wilkinson et al. (Citation2008) identified the need for further research on the influence of the national culture of subsidiaries on the control of the multinational, on the cost/benefit ratio of expatriate involvement in subsidiaries, on the effects of cultural distance on the strategy adopted; Malmi et al. (Citation2022) call for more research on multinationals and “how they either adjust, or not, their MC practices to local environments, and whether these choices have an impact on the effectiveness of those MC practices used”; and Mao et al. (Citation2020) suggest that the impact of subsidiary objectives on performance depends on the degree of managerial control exercised by the parent. Berry et al. (Citation2009) noted the importance of further research on the link between control and management risk and on the relationship between control and culture and according to Sageder and Feldbauer-Durstmüller (Citation2019), the impact of internationalization on process control and the relationship between shared values and decentralization remain unresolved.

This fragmentation of the research field is a clear indication of a research gap and, therefore, a call for more research (Malmi et al., Citation2020, Citation2022; Mitter et al., Citation2023). Consequently, the following research question arises: How does the parent influence the subsidiary’s MCS characteristics? Where it is intended to study dynamically the MCS of a subsidiary belonging to a foreign economic group, emphasising the constructs autonomy (e.g., Keupp et al., Citation2011; Luo, Citation2003; Mirchandani & Lederer, Citation2008), organisational and local culture (e.g., Björkman & Piekkari, Citation2009; Brenner & Ambos, Citation2013b), legitimacy (e.g., Busco et al., Citation2008; Mundy, Citation2010) and networking (e.g., Gammelgaard et al., Citation2012). More recently, Yue et al. (Citation2021) considered that it is important to study the subsidiaries acquired by multinationals (post-acquisition) regarding the control and its strategy. The research question formulated above aims to study dynamically the MCS of a subsidiary owned by an economic group, to identify the factors that affect the characteristics of the MCS in a subsidiary owned by a Multinational Enterprise (MNE).

The motivation behind this scientific study lies in the fact that, although this analysis model has been used previously in several scientific studies of reference, it has not yet been applied to the mining industry. Thus, this is intended to be a pioneering investigation in this area of knowledge.

After this brief introduction, the literature, methodology, results and conclusions are presented.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Institutional theory and management control systems

Previous studies have used this theoretical building block to investigate the various constructs impacting MNEs (Geary & Nyiawung, Citation2021; Ilhan-Nas et al., Citation2018; Xenia et al., Citation2019; Yahiaoui & Farndale, Citation2021; Zhang & Beamish, Citation2019), as the focus of this theory is on the macro-organisational environment and the legitimation strategies of organisations, as well as, by the use of the concepts of isomorphism and loose coupling (Leite, Citation2015). Hall, & Taylor,1(998) argued that sociological institutionalism defines institutions not as something that includes only formal rules and procedures but also cognitive and moral symbols. Within this framework, institutions (implying organisations as an institution) affect the behaviour of the individuals who are part of it, both in the rational (commonly called normal) preferences and their own cultural identity, the same author argued. For Meyer and Rowan (Citation1991), this theory emphasises organisations’ cognitive, symbolic, cultural, and normative factors. For these authors, organisations reflect economic pressures and the pressures of the institutional environment. Based on these conclusions, the case study (mining sector) is the mirror of this situation, in which its success in the face of the environment depends on the use of practices considered legitimate, in which isomorphism is visible by the existing pressure for the organization to adopt a posture of homogenization of practices, whether of a cultural, social and political nature (external pressure), or by the adoption of systems of similar practices within the sector of activity in which it is inserted and those imposed by the economic group to which it belongs (internal pressure). As for the concept of loose coupling, this translates the existing gap between the systems that are used for external legitimacy purposes (the mining sector has its own national and international regulatory entity) and those used for the management of operational activity (imposed by the economic group to which it belongs). Thus, in the international business context, some researchers have used institutional theory to explain the phenomena that occur in the management of subsidiaries owned by MNEs. By way of example, the institutional theory, for which organizations operate in a complex and uncertain environment, originates that their decision-making will depend on institutional forces that influence the organization (Francis et al., Citation2009). Also, to explain the strategies of MNEs, the same strategy has to be adapted to the ongoing global and local changes (Dabic et al., Citation2014). These authors argued that, in the case of MNEs, strategy is the way to improve the relations of the parent company with its subsidiaries, allowing to overcome the barriers that exist for the latter to have practical autonomy within them. Milliken (Citation1987) study explored the different types of uncertainty that strategic decision-makers may face. He distinguished them into three specific types: the first is uncertainty about the state (when the manager does not feel able to understand or perceive how a factor of the external environment will evolve); the second concerns the inability of managers to foresee the impact of external changes on the organization (uncertainty effect); thirdly, the uncertainty associated with attempts to understand which response options are available in the organization and their value as such (response uncertainty).

It should be noted that, environmental uncertainty (Dabic et al., Citation2014) and institutional distance (Aguilera Caracuel et al., Citation2010) have been grounded in institutional theory. Additionally, the institutional environment cannot be considered an independent factor for multinationals in defining and implementing their strategies (Dabic et al., Citation2014), with institutional theory having a predominant role in explaining this challenge (Ronda-Pupo & Angel, Citation2012). Harvey et al. (Citation2001) emphasized the role of human capital in multinationals, particularly the role of expatriates to manage issues related to cultural distance and language barriers. After explaining the use of institutional theory in research on MNEs and its explanatory power, as Geary and Nyiawung (Citation2021) argued, the next sections explore the MCS and its constructs.

2.2. Management control systems - characteristics and constraints in multinational companies

2.2.1. Management control and management control systems

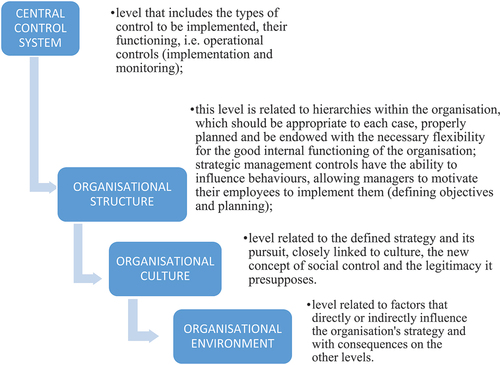

The control system is generally composed of several levels: central system, structure, culture and environment (Flamholtz, Citation1996). In the organizational environment level, the strategy implementation is a starting point for strategic planning (Dyson, Citation2000; Mintzberg, Citation1990). The strategy aims to align all organisational features in a comprehensive manner (Acuña-Carvajal et al., Citation2019; Hamid Hawass, Citation2010). Recent studies suggest that for a strategy to be viable, it must be aligned with a specific type of MCS (Jukka, Citation2021). Organizational strategies are dynamic, so managers need to regulate their strategies considering external opportunities and threats (Cokins, Citation2017). Managers who perform correct strategic planning can anticipate continuous changes (Montgomery, Citation2008), and MCS can be seen as the driving force behind organizational change (Bracci & Tallaki, Citation2021; Nuhu et al., Citation2019).

In this context, any MCS should include planning, coordination and communication activities, information assessment and, above all, influencing people to work in line with the organisation’s objectives (Icfai, Citation2006; Parker & Chung, Citation2018). The MCS should be based on general and inherent characteristics. Control decisions are based on the strategy defined by the shareholders, which should be understood as a tool to implement that strategy. In this process, it is important to consider individuals’ behaviour in the organisation and future orientations and clear objectives to avoid loss of control (Parker & Chung, Citation2018).

Given the evolution of the management control concept and, consequently, of the MCS, managers must be able to use accounting information to achieve, in a congruent manner, the defined goals, i.e., they must be flexible to adapt their behaviour to the environment (Xinxiang, Citation2016). In this line of thought, some authors (Chenhall, Citation2003; Collier, Citation2005) have considered that MCS has evolved over the years, and today there are several models to understand management control, namely those based on informal controls (Otley & Berry, Citation1980; Simons & Simons, Citation1995) and formal controls (Ditillo, Citation2004; Ouchi, Citation1979).

The MCS can be formal (based on written procedures and influences the behavior of individuals) or informal (no written procedures). If the MCS is formal, it includes entry controls (selection, hiring, training, resource allocation, among others), process controls (in routine activities), exit controls (comparison of planned and actual, leading to monitoring and evaluation). On the other hand, if the system is informal, it suggests self-control, through the congruence of individual objectives with the objectives of the organization, the introduction of social controls, which relate to values, commitments between both parties, but also monitoring and evaluation, and cultural controls, based on beliefs and rituals (Icfai, Citation2006).

2.3. Management control in multinational companies

In order to study MCS, it is crucial to take into account the relations between the multinational companies and their subsidiaries; in general, these relations reflect the relationship between two entities, one of which is financially dependent but legally independent from the other; in other words, the head office is generally the part of the organization where decisions are taken and strategy is defined, and the subsidiary is the reference unit controlled by the head office; however, the subsidiary is a legal entity separate and distinct from the head office for regulatory and tax purposes, as opposed to the control exercised by the head office and its dependence (Hoppmann, Citation2008). This is the case with large multinationals. Furthermore, the subsidiaries’ geographical dispersion and cultural differences make their control and proper integration an even more difficult task since headquarters is confronted with different socio-economic and legal realities (Kostova & Zaheer, Citation1999).

These relationships have been extensively studied under different theoretical frameworks, and multinationals represent one of the engines of economic development in the world (Hoppmann, Citation2008) since the growth of multinationals is based on the lower costs caused by the integration of operations (Roth & Nigh, Citation1992).

The effects of the MCS on organisations are intrinsically linked to its characteristics (formal and informal controls). However, many of the subsidiaries operate in emerging economies, which represents a difficulty in relocating expatriate managers regarding their cultural adaptation and quality of personal life (Harvey et al., Citation2001).

However, concerning management control in multinationals and its characteristics, companies have expanded beyond traditional borders in recent decades. Therefore, this business growth has made it imperative for managers/shareholders to increase awareness of the critical issues involved in investments, control mechanisms, management practices in subsidiaries, and culturally different countries’ diversity. Thus, multinationals must adapt to the various control practices used in the countries of origin (headquarters) to meet the host countries’ requirements (subsidiaries). In this process, an inadequate adaptation of the control systems used in the country of origin (headquarters) acts against the organisation’s interests. In this context, Icfai (Citation2006) considers several types of control (Personal controls, Output controls and Bureaucratic controls) used by multinationals to monitor and improve performance.

In this sense, according to Icfai (Citation2006), some of the factors that determine the type of influence the multinational has over the subsidiary are as follows: a) Headquarters/Subsidiary relations—the move from domestic to foreign markets involves greater strategic control by the parent company in its subsidiaries; b) Impact of global competition—In order to compete on the global market, a multinational must go beyond the boundaries of national markets and prepare a global strategy; c) Impact of host government requirements—Often the host government (i.e., the country’s government in which the multinational’s subsidiary operates) intervenes in the multinational’s operations.

2.3.1. Subsidiary autonomy and management control

Over the last few decades, the effect of subsidiaries’ greater autonomy on their performance has been an important research topic in the international context (Kawai & Strange, Citation2014). The complexity and diversification of activities within the parent companies have meant that they are under pressure to shape and coordinate their relationships with their subsidiaries while at the same time allowing them some authority and influence (Birkinshaw et al., Citation1995). Thus, autonomy is the degree of decision-making power the subsidiary possesses vis-à-vis the multinational in terms of strategy, function and operation (O’Donnell, Citation2000; Taggart & Hood, Citation1999). This implies that the subsidiaries’ managers may have more or less decision-making power regarding the choice of specific resources of the subsidiary, such as technology, knowledge, finance, and human resources.

Several authors contributed to the understanding and analysis of the autonomy variable in subsidiaries, synthetically, the main conclusions were the following: Birkinshaw et al. (Citation1995) argued that leadership and strategic initiative are promoted by autonomy, which contributes to competitive advantage; Luo (Citation2003) concluded that delegating decision-making power to subsidiary managers allows for an adequate and proactive response to customer needs, increasing competition and the progression of the product life cycle and that the independence of subsidiaries leads to the correct alignment of business strategy with local market conditions, as well as encourages organisational learning; Young and Tavares (Citation2004) highlighted the creation and dissemination of knowledge stimulated by autonomy; Mirchandani and Lederer (Citation2008) concluded that delegating decision-making power to subsidiary managers provides incentives for them to feel more responsible for it. However, Keupp et al. (Citation2011) argued that the subsidiaries’ autonomy leads to increased control and coordination costs to be borne by shareholders and the risk of isolation of the subsidiaries.

Kawai and Strange (Citation2014) have introduced a further variable in this field. For instance, they have suggested that the relationship between autonomy and performance is tempered by the multinational’s environmental uncertainty and internal coordination mechanisms. For these authors, this environmental contingency has provided important information for organisational learning, organisational responsibility (Goll & Rasheed, Citation2004), and entrepreneurial leadership (Ensley et al., Citation2006), for employment flexibility (Kawai & Strange, Citation2014; Lepak et al., Citation2003), for the results of the marketing strategy from the point of view of innovation (Atuahene-Gima et al., Citation2006) and to strengthen the profitability strategy (Andersen & Andersen, Citation2005).

On the other hand, internal coordination is related to the subsidiary’s autonomy, which can lead to the placement of expatriates in the subsidiary to increase its performance. Kawai and Strange (Citation2014) studied these issues in subsidiaries of Japanese multinationals, and reached the following conclusions: 1) the subsidiary’s perception of autonomy does not involve a direct and positive relationship with its performance and does not affect its competitive advantage; 2) under environmental, namely technological, uncertainty, the exclusion of a hierarchical structure leads to an increase in responsiveness; 3) the involvement of expatriates increases performance and is a moderating element in the subsidiary’s relations with the parent company, which can provide more comfortable and broader access to resources spread around the world (human, material, financial); 4) the involvement of expatriates may not be well accepted within the subsidiary and may generate some conflicts; 5) due to technological uncertainty, autonomy will be essential for the development of products adapted to the local market; 6) decentralized subsidiaries, although with control and coordination mechanisms, will probably collect information and improve the interdependence of resources, and increase their performance.

Following on from the previous idea, Wilkinson et al. (Citation2008) pointed out that as expatriates are seen as a control mechanism, this can be defined as a process through which the shareholders (multinational, parent company) protect their interests.

2.3.2. Cultural integration in management control systems

Another crucial issue is that multinationals must adapt to control systems’ prevailing practices at home to the foreign country’s prevailing conditions. These controls should be assessed continuously and modified when necessary. Control systems need modifications or changes because these are affected by cultural differences between countries and different business environments (Icfai, Citation2006). Cultural integration between multinationals and subsidiaries depends on the degree of resistance to change (Caldas & Tonelli, Citation2002), how to deal with differences and the alignment of values (Zago & Retour, Citation2013). Tanure et al. (Citation2011) also concluded that cultural integration is a challenge, as it consists of trying to minimise various effects, including the attempt to build a shared value chain that generates attitudes of cooperation and exchange of knowledge, i.e. the existence of the necessary synergies for business growth. Based on the cultural differences within multinationals, particularly between the parent company and its subsidiaries, it can be seen that the phenomenon of globalisation poses enormous challenges to management control practices, which have to adapt to the variable location. According to some authors (Giraud et al., Citation2011), it cannot be understood as a mere technique that encompasses procedures, practices, and people in an organisation also as a relationship with national cultures.

Giraud et al. (Citation2011) presented a summary of the implications of different crops in designing a control system based on the study by Hofstede (Hofstede, Citation1980). These authors concluded that management control, in a broad sense, can take different forms depending on the cultural influences of host countries (location of subsidiaries). Those cultural values can act as facilitators or obstacles to the proper functioning of this system.

The increasing globalisation of business has led to control being seen as a management tool used in different countries; however, the different cultures involved imply different attitudes towards control mechanisms (Chow et al., Citation1994). Thus, cultural differences may result in management controls being useful in one country and ineffective in another (Chow et al., Citation1994). Interest in research into cultural influences on MCS was triggered in the 1980s (Harrison & Mckinnon, Citation1999), remarkably comparing Anglo-Saxon culture and Asian culture. In the 1980s, the need to improve organisational performance gained particular urgency in the United States and other industrialised countries because of the enormous competition from Japanese companies (Jaeger & Baliga, Citation1985). According to Ouchi and M (Citation1978), Japanese industry’s success is because these companies have different characteristics from other areas of the world, i.e. lifetime employment, consensual decision-making, collective responsibility, slow assessment and promotion, informal implicit control, unskilled career plan and holistic concern.

Thus, in multinationals, the interaction between the MCS and culture has become pertinent. Several academic works study this theme, namely through Hofstede’s (Citation1980) dimensions, or the dimensions of the Globe (Grove, Citation2005). In this context, the relationship between MCS and culture has been analysed based on the taxonomy of Hofstede (Citation1980), who elaborated a study in subsidiaries, at a world level, in which the cultural dimensions were defined. With this typology’s appearance, it was possible to classify culture in measurable variables and countries according to these dimensions, evaluating their interaction with organisational variables and with MCS (Xinxiang, Citation2016). Giraud et al. (Citation2011) studied the differences between managers’ perceptions of various nationalities regarding the exercise of control, intending to conclude on the impact of cultural differences. They concluded that Japanese managers stand out from those in Europe and the US in terms of negotiating style, which is guided by non-confrontational principles, are also less positioned as business partners, and have less knowledge of the operational aspects of the business, where they rarely take initiatives of their own without the request coming from their hierarchical superior. In this context, they conclude that divergences and convergences between managers’ perceptions/behaviours from different countries and cultures lead to different control practices, so it is essential to understand the host country’s national culture. Japanese companies’ characteristics can be considered sui generis regarding the way they exercise control (centralised and personalised) due to their inherent culture.

Sarala and Vaara (Citation2010) found that cultural differences stimulate the transfer of knowledge through the exchange of different practices and that these should be seen as adding value for both parties. These authors also pointed out that reducing these differences may imply creating a new organisational culture focusing on communication between leaders and training. For their part, Chakrabarti et al. (Citation2009) found that there may be cultural conflicts between the subsidiaries and the parent company, depending on the structure’s rigidity, the level of collectivism and individualism and the degree of aversion to uncertainty. However, acquisitions are more profitable in the long run if the acquirer and the acquired company are from more culturally distant countries. These conclusions are not, however, consistent with those presented by Barkema et al. (Citation1996) who argued that when cultural distance is high, this has a negative effect on the long-term profitability of the investment.

Despite the physical distance, Moilanen (Citation2008) stressed the importance of accounting as a tool for multinationals to control their subsidiaries and even rely on their financial systems. Today, in the Western world, accounting is more linked to new technologies and new operations, more adjusted to multinationals’ reality, allowing managers to better assist in decision-making (Granlund & Lukka, Citation1998). Accounting information from subsidiaries is now used for different purposes. In this sense, there must be trust in the system (trust that the accounting data are true and correct) and trust in people (that the subsidiaries’ managers apply the multinational principles). In this context, accounting makes it possible to control and direct operations and communicate information between the parent company and the subsidiary.

Brenner and Ambos (Citation2013b) correlated the changes in recent decades with an imperative need for global competition. It is important for multinationals operating in a global environment to maintain control over overdispersion, added value, and distance from subsidiaries in this changing context. The persistence of cultural and institutional differences and the increase in local competition require some subsidiaries’ autonomy. Simultaneously, increased interdependence, cost pressure and standardization of rules require some levels of control and alignment with the parent company as a global chain. As a result, shareholders have to consider several trade-offs when designing their control strategy.

2.3.3. Legitimacy in management control systems

For Brenner and Ambos (Citation2013b), legitimacy and the process of institutionalisation are crucial to resolving the issue of multinational companies’ control over their subsidiaries. To this end, shareholders have to support implementing a control system because for control mechanisms to be institutionalised, they have to be legitimate. Furthermore, this transmission’s success can be translated into social control (standards, values, culture, training, learning and inclusion of expatriates) in the system. Thus, legitimacy is a social form of approval and is crucial for the exercise of authority, for building trust and accepting decisions.

Legitimacy is also related to the importance of the subsidiary for the multinational. Yamin and Andersson (Citation2011) conducted a study on Swedish multinationals, which concluded that the importance of subsidiaries correlates with the importance of products, level of production, size, number of expatriates, age (number of years of existence), degree of rooting (domain, commitment) in the multinational. These authors also pointed out that the importance of the multinational subsidiary may be conquered or lost over time; everything depends on its involvement in the multinational’s network and its corporate vision.

2.3.4. Networking in multinational control and coordination

As global competitiveness has increased, the need for competitive advantage has also intensified. Therefore, a multinational with geographically dispersed subsidiaries must have the flexibility to operate in networks, implying control and coordination (Ensign, Citation2007). Multinationals themselves must have the organisational capacity to respond and assess opportunities because they constitute a competitive network (Ensign, Citation2007). However, there are contingent factors, different from country to country, from sector to sector, so it is necessary to identify the factors that do not create a competitive advantage (Ensign, Citation2007). In this context, the organizational network must be characterized by flexibility and responsiveness to changes and uncertainties of the environment, which implies a broad involvement of managers in the identification of critical factors of the environment, the need for performance evaluation mechanisms, and dynamism on the part of managers (Ensign, Citation2007).

As we have already seen, another critical variable in the MCS is autonomy. Gammelgaard et al. (Citation2012) analysed subsidiaries’ autonomy at the level of the use and integration of network relations and their relationship with performance. From the analysis’s perspective, the subsidiaries’ development strategy is affected by the number of connections (quantity of transactions and relationships) and their effect on performance. In this analysis, the authors considered that, from Intra and Interconnections, there are benefits of innovation and learning. The subsidiary’s autonomy is associated with its level of power and freedom in decision-making and its level of performance. They also concluded that greater autonomy generates greater freedom for subsidiaries to interact in the multinational’s network and affects performance.

The following research propositions have, therefore, been defined:

P1 - The characteristics of the MCS influence the degree of autonomy of the subsidiary.

P2 - The local/organisational culture influences the characteristics of the MCS of the subsidiary.

P3 - The legitimacy/confidence that the parent company delegates to the subsidiary and directors of the subsidiary influence its MCS characteristics.

P4 - The non-networking between the subsidiary and the parent influences the characteristics of MCS in the subsidiary.

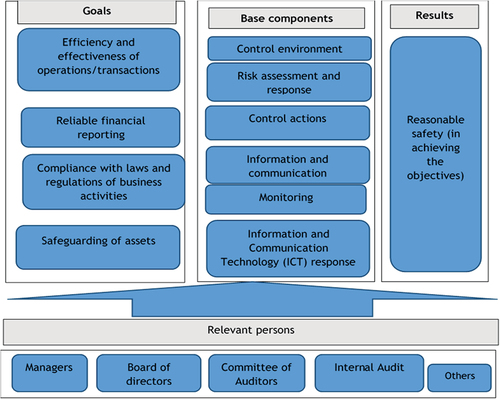

These propositions provide the answer to the research question: How does the parent influence the subsidiary’s MCS characteristics? They are supported in Flamholtz (Citation1983, Citation1996) model and Flamholtz et al. (Citation1985), which postulates with the necessary adaptations to the intended objective and is displayed in Figure . Level related to the defined strategy and its pursuit, closely linked to culture, the new concept of social control and the legitimacy it presupposes.

Figure 1. MCS - adapted for Flamholtz et al. (Citation1985); Flamholtz (Citation1983, Citation1996).

Taking into account the constructs under study, Table displays their connection with the framework presented in Table and their association with the literature reviewed.

Table 1. Variables vs. Flamholtz et al. (Citation1985) and Flamholtz (Citation1983, Citation1996) levels of control

Thus, with this analysis model, we intend to demonstrate the importance of the MCS for geographically dispersed subsidiaries with different cultures as a crucial tool for multinationals to control and carry out effective and strategic management of their businesses. In line with what has been stated throughout this dissertation, it is understood that there are fundamental principles that should underpin such a system, such as the use of financial and non-financial instruments, decentralisation, delegation and accountability, alignment of objectives; it should not be based solely on bureaucracy and papers; it should be visionary and proactive; it should influence people (behaviours) and should encompass a performance assessment system; it should presuppose planning and monitoring. Finally, it is fundamental that there is interconnection and alignment between all control system levels to achieve effective and efficient results. If each level only works per se and not as a whole, serious control failures will arise. In short, the adopted model allows providing organisations with the means to follow the whole cycle of management control (definition of objectives, planning and monitoring) and to demonstrate the pro-activity, dynamism and legitimisation of internal control systems, as well as that the congruence of objectives and individual, organisational and cultural behaviours that these implications are fundamental for the success and competitive advantage of organisations in the globalisation and knowledge era.

3. Methodology

Despite seeming, in the light of positivist theories, an inadmissible procedure, in interpretative research, the researcher is involved in the object of investigation in which the interpretation obtained results much from his experience as a researcher Silva (Citation2013). The results of this type of research usually present an account of concrete situations, allowing for various interpretations that are tested. In short, interpretive research advocates that there are varied and interesting ways, all valid, of seeing the world Silva (Citation2013). A widely used theory in this type of research is institutional theory. The positive approach also allows triangulation with the institutional theory. However, this crossing has been little used to study this theme (Leite, Citation2015). The use of qualitative research in management accounting studies has become more common to study the impacts of globalisation, particularly on the business of multinationals (Baxter & Chua, Citation2003). Because the case study allows for analysing the complexity of social phenomena (Yin, Citation2015), it has become popular in international management accounting and control research (Baxter & Chua, Citation2003). Yin (Citation2015) explains that the case study is an appropriate method for “how” and “why” type research questions, such as those formulated in this study, which allow the researcher to understand complex social phenomena holistically. And is a relevant research approach to study management control (Barros & Ferreira, Citation2022; Langfield-Smith, Citation1997; Rodrigues et al., Citation2021). Piekkari et al. (Citation2009) also argued that qualitative research is crucial for the study of multinationals since it makes it possible to interpret and understand the multiplicity of contexts, for instance, the organisational context, the cultural context and the institutional context, as well as their interconnection. For these reasons, and since we are going to study how the parent company influences the MCS of the subsidiary, a single case study approach was followed.

The methodological procedures to be followed in researching a case study are fundamental. However, it is also imperative that the research proposals are well grounded in the literature review (Yin, Citation2015). On the other hand, the steps of the methodology will be outlined according to Yin’s (Citation2015) case study design. First, the research design was based on the points reviewed in the literature, which support the research proposals, to ensure the reliability of information Yin (Citation2015). According to the literature, this is the most appropriate method for analysing qualitative results from interviews. Secondly, there is the preparation for information gathering—this phase reflects the researcher’s capacity, preparatory measures (e.g. contacts, dates for interviews, collection of written information), and preparation of interview scripts; this phase is also considered crucial by Yin (Citation2015). Then, evidence gathering included collecting information from multiple sources of evidence and setting up a database to ensure a chain of evidence (Yin, Citation2015). The study of several variables allows for a chain of evidence and data triangulation. In this study, written documents and interviews are a dual source of evidence (Leite, Citation2015). Then, analyze the evidence—based on the reliability of the evidence collected and its validity in its context, and establish standards for analysis (Yin, Citation2015). Finally, there is the writing of the case study—here, Yin (Citation2015) recommended following the proposed research questions in the presentation of the findings and in the written composition.

This study focuses on a case study of a qualitative and constructivist nature, as an intense and deep understanding of a given social context was sought to understand it in all its complexity (Yin, Citation2015). Thus, according to Yin’s definition, it is a single case study, as this research aims to study only one reality. For this type of case study, conducting interviews is a tool that allows understanding how the facts occur and their connections (how and why) given that this study typology deals with people, said the same author. The case study follows its methodological perspective and is not only a method for data collection (Ryan et al., Citation2002). In this sense and based on the case study protocol and the research question, the collection of evidence should be guided by three crucial rules, i.e., the use of various sources of evidence, the creation of a case study database and ensuring the existence of a chain of evidence; the criteria used to ensure the quality of the case study concerning the analysis model, internal and external validity and reliability (Yin, Citation2015). The data were collected through documents, observation, and interviews with senior management of the subsidiary under analysis, i.e. multiple sources of information were used, which allowed an empirical study to be carried out for the internal validation of the results. Finally, the reliability of the case study is corroborated by the various sources of evidence gathering, interviews and various documents (e.g. legislation, formal company documents), allowing the evidence to be credible.

Regarding the interviews (Appendix 1), and to increase their credibility, they were written and then sent to the interviewees to validate the text. Although the research focuses on a monographic/holistic study, it will be based on an analytic-linear structure, in which one’s ideas/propositions about the referred company will be presented (based on facts) and whose evidence will be confronted with the ideas presented by other authors, thus allowing the effectuation of conclusions and recommendations as an added value for this particular case (Barañano, Citation2004). Also, Yin (Citation2015) stated that a single case study becomes more vulnerable than a multiple case study, as the latter is more robust. However, these can also lead to a poor depth of the same analysis. However, as this single case study has several units of analysis, it fits into Yin’s (Citation2015) typology, i.e. it is a holistic and chained research.

The sources of evidence are primary, and the following have been used 1) Semi-structured interviews; these are the most widely used in qualitative research on this topic, through which an attempt has been made to collect as much information as possible from interviewees Silva (Citation2013); 2) Observation—this technique was applied at the same time as the on-the-spot interviews, in which the reaction of the interviewees to the questions raised was observed Silva (Citation2013); 3) Written documents and records, such as internal reports, written procedures and standards, audit reports, legislation, websites, among others Silva (Citation2013). Yin (Citation2015) concluded that formal documents as sources of information to be attached to the interviews are adequate for a case study. The documents obtained from the Financial and Administrative Department (director C) of the subsidiary based in Portugal have provided detailed information on the case under study. Access to this document is vital given the relevance of this documentary support to corroborate the interviews. According to Barros and Ferreira (Citation2022) “this use of multiple sources obtains richness in descriptions and explanations and a more in-depth understanding of what really is going on in the field” (p.10).

The selection of this subsidiary for this study is related to the fact that the extractive industries sector is at the base of the vast majority of downstream industrial activities, having enormous potential to create, contribute and support sustainable development both in the communities where it operates (opportunities for growth and employability), as well as in the communities where the processing industries that consume its products are installed (Franco, Citation2014; Rodrigues et al., Citation2021). In this scenario, this subsidiary is considered a strategic company for the development of the extractive industry in Portugal, being currently the only mining company in Portugal that explores tungsten (raw material considered critical by the European Union) as it is an essential pole of direct and indirect employment for the region. The interviewees are all the subsidiary’s directors and managers (the directors are from the areas of mining, geology, finance and management, human resources), given that they are all crucial pillars for the subsidiary’s productive activity and financial performance, as well as the expatriate placed there as a way for the MNE to exercise control.

The interviews were conducted in December 2015, on the 12th (directors (A, B) and expatriate), the 16th (directors C, B, and D), and the 20th (directors E and G). They were conducted in a face-to-face manner, with the researcher traveling to the premises of the subsidiary. Table provides some information about the 8 respondents (position and seniority in the subsidiary) and the interviews (time spent).

Table 2. Characterization of interviewees

As can be seen, all the local staff of the subsidiary have considerable experience in the company (between 4 and 12 years of experience). However, only Director B covers the entire Japanese holding period, so his contribution has proved extremely useful as a source of evidence. The interviews were not recorded at the request of the Board of Directors and external entities but were subsequently transcribed by the investigator. The interviews’ written document was sent and validated on the spot by the interviewees for their reading, possible corrections, and final validation. The final text of the interviews was a crucial source of evidence for the case study.

4. Case study characteristics

As for the national extractive sector, although Portugal’s territorial dimension is small, the country has very diverse and complex geology and is very rich in essential mineral resources. This potential, combined with the EU’s dependence on certain mineral raw materials, is an opportunity to help, through the development of the extractive industry, improve the endogenous national resources, and contribute to the development of the national economy through the services involved, distribution and sale of products, job creation and export growth (Direção Geral de Geologia e Energia, Citation2015). For this entity, this subsidiary is strategic nationally and regionally.

The parent company is involved in many different businesses and has excellent economic and institutional power in its home country. It also has a defined MCS for all its subsidiaries, in which an expatriate is included as an important control mechanism (interviews with local administrators and expatriate administrators). The subsidiary under analysis has a secular history in Portugal, whose sale of its final product (mineral concentrate) between 2007 and 2015 resulted in around 160,000 million euros of exports, which corresponds to approximately 1,800 tons of production, employing around 270 employees in 2015 (annual public accounts). On the other hand, its MCS has been adapted to what was required by the parent company, within what was possible in concrete terms.

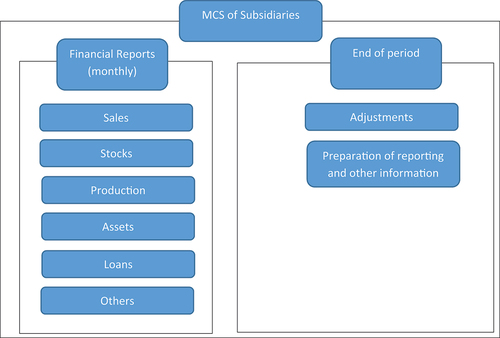

Thus, the MCS defined by the parent company for its subsidiaries is based on the following model (Figure ).

Thus, the characteristics of the MCS of MNE described below were defined by the Internal Control and Administrative. This means that management control must contain preventive measures to reduce possible risks in corporate (subsidiary) activities. The efficiency and effectiveness of operations/transactions promote business goals. However, they depend on the circumstances inherent to each business, as they are different from company to company and the assessment of this goal fluctuates according to these differences. Reliability of financial reporting and information has to take into consideration the material effect of possible errors on the financial statements; this objective is required by Japanese legislation—Financial Instrument and Exchange Law- to ensure this reliability, Io which implies that any information with a materially relevant effect on the financial statements must be identified so that the financial reporting is correctly reported; compliance ensures agreement with the legislation applied to each business, but also the application of the standards of ethics and conduct and the corporate philosophy (values), the safeguarding of tangible and intangible assets ensures that these are acquired, used and disposed of following formalised procedures.

As for the basic components of the MCS (Figure ), the control environment includes ethical values and integrity, management philosophy and style, management policies and strategy, the role of the board of directors and audit committee, organisational structure and practices, levels of authority and responsibility, and human resources policies and management. Risk assessment encompasses a series of processes to correctly analyse the factors that represent an adverse risk that may affect the achievement of the organisation’s objectives on which corrective measures and responses must be taken to eliminate or reduce them. The control actions and measures related to the procedures and policies established ensure that managers’ orders/instructions are adequately followed. These actions also include segregation of duties, responsibilities and authorisation levels. The communication and information system ensures that the necessary information is identified, understood, processed and communicated accurately to stakeholders at the right time. Monitoring is understood as a continuous process to assess the effectiveness of the internal control system. The internal control system must be observed, evaluated and modified according to the results of this monitoring. The response of information technology is to implement appropriate policies and procedures to ensure that the organisation’s objectives are achieved inside and outside the organisation (Figure ).

The companies’ levels should include a formalised organisational structure (organisation chart) with authority limits and segregation of duties; they should also consider the corporate culture and management, the risk, the existing information technology, and the internal audit recommendations. The management of the subsidiaries must implement a control system appropriate to their characteristics, but always to guarantee the objectives, essential components and levels of control mentioned and intended by the group.

This means that management control must contain preventive measures to reduce possible risks to incorporate activities (subsidiaries). The efficiency and effectiveness of operations/transactions promote business goals but depend on the circumstances inherent to each of them. They are different from company to company, and this objective’s evaluation oscillates according to these differences. The reliability of financial reporting and information has to take into account the material effect of possible errors in the financial statements, which implies that any information with a materially relevant effect on the financial statements must be identified in order for financial reporting to be correctly reported; compliance guarantees compliance with the legislation applied to each business, but also the application of standards of ethics and conduct and corporate philosophy (values), safeguarding tangible and intangible assets guarantees that they are acquired, used and written down following formalised procedures.

The managers of the subsidiaries must implement a control system appropriate to their characteristics, but always in such a way as to guarantee the objectives, necessary components and levels of control mentioned and intended by the group.

Regarding the MCS of this one, it has undergone changes/adaptations compared to what was intended by the parent company, as Director C explained. ”The control system implemented in the subsidiary aims to ensure the effectiveness and efficiency of all operations, the reliability of financial reporting; the compliance with legislation and internal regulations; the safeguarding of all assets.” This objective is achieved by an appropriate control environment, risk analysis of the company’s activity, information and communication, monitoring and information technology. It should be noted that locally, information technologies are reduced and below what is intended. The parent company defines control as a series of rules and procedures to carry out its economic activity well to prevent errors, fraud and inefficiencies. The group defined the implementation of the current MCS was defined in April 2008 by the group, following several policy changes caused by the ENRON and WORL-COM scandal. The imposition of this policy on subsidiaries by the group only started later, in our case in 2013. This change led to Directors having to reply to internal control questionnaires sent out by the Audit Committee: the one on control to assess the control environment; Reporting Finance to assess controls on reporting and the preparation of financial statements and others to assess controls information system. As a result of the results obtained from our responses, improvements were requested, which in some cases were implemented. However, this was not possible in other cases due to an apparent lack of time and financial availability (the case of information technology).

In 2014, the Audit Committee sent the same questionnaires to assess the progress of the controls mentioned above. In any case, some of the controls already existed before the acquisition in 2007 by this group. Others were adapted/changed or implemented at its request from 2008, and, finally, others have not yet been implemented (for example, the reporting procedures already explained in this interview). The controls planned and implemented by the group are segregation of duties (although not linear and easy to implement, given the small size of the financial area); Definition of authorisation levels per director; Annual staff evaluation; Preparation of the worker’s manual; Manual of conduct and ethics and the support hotline; Annual self-assessment of directors according to work developed in the respective area; Adoption of the group’s accounting policies, provided they are compatible with the SNC; Preparation of the monthly statement of currency exposure and the foreign exchange contracts performed; Confirmation of balances and transactions with group companies (twice a year); Preparation of written contracts for the provision of services and supplies in the medium and long term; Minimum stock in the warehouse. Controls already implemented and in place before the acquisition have been maintained or adapted and are in place: Comparison of the budget with the actual values (monthly) and respective explanation of the deviations by cost centre; Reconciliation of the analytical accounts with the general accounts (monthly); Monthly bank reconciliations, copies of which are sent to the parent company; Physical inventory of finished products and subsidiary and consumption raw materials, which started as annual and are now monthly in rotation system; Reconciliation of the trial balance accounts with the additional software that supports the stock and fixed assets applications; Preparation of a forecast cash flow and its comparison with the actual cash flow for receipts and payments, which started monthly, then weekly and in 2015 daily. Within the group, the control system operates at the highest level (Administration) through the Audit Committee, which controls and supervises the management of the subsidiaries and head office to implement the policies defined by the group. The planning of controls since 2007 is suggested/imposed by the parent company, and it is up to each director in his or her area to implement them. In my case, I have been implementing the controls as mentioned above since 2007, although this would add a burden for the financial department. The monitoring of these controls is carried out by the expatriate, the other local administrators and the group’s Financial Department. In addition to the answers to the control questionnaires, some of the controls mentioned above are periodically sent to the parent company, such as comparing the budget with the real, the cash-flows, the currency exposure, and bank reconciliations. “Sporadically, I also reply to questionnaires on other subjects, such as transfer pricing and deferred and local taxes”.

5. Presentation and discussion of results

5.1. Autonomy

Several authors (e.g., Birkinshaw et al., Citation1995; Keupp et al., Citation2011; Luo, Citation2003; Mirchandani & Lederer, Citation2008; Young & Tavares, Citation2004) have analysed the autonomy variable shows its relevance when studying multinationals, regardless of their context. Furthermore, this variable is also related to expatriates (Kawai & Strange, Citation2014).

According to the interviews carried out, it was found that the subsidiary only has operational autonomy for day-to-day management, as “… it does not have autonomy vis-à-vis the parent company in the decision-making process, such as on sales strategy…” argues Administrator A. This lack of autonomy implies that any crucial decision for the subsidiary is a lengthy process, reflecting the inefficiency of the channels of communication “…due to cultural and sometimes linguistic barriers, as well as, some lack of knowledge about lode mines, which implies that the added value, the synergies are only to one side…” says the same; Administrator B, still considers that this lack of autonomy does not bring benefits to the subsidiary. Both consider that the decision-making process is prolonged. The decisions taken are not always “…understandable…” but disagree on the transparency of the flow of information between the parent company and the subsidiary. That is, Administrator A considers that “…this flow is fast and transparent, which does not prevent the decision-making process from being slow…”, while Administrator Y understands that “the flow is very slow as I have already mentioned and sometimes it is not transparent and elucidative, it gives the impression that the shareholder does not know exactly what he wants to do, eventually due to technical ignorance of the seam mines. It has to do with the parents’ culture because they are suspicious and do not like changes; everything has to happen according to what is formalized”.

O’Donnell (Citation2000) and Taggart and Hood (Citation1999), where autonomy is the subsidiary’s decision-making power in strategic, functional and operational terms since it is clear that the autonomy of those in charge of the subsidiary is solely operational in order to cope with the day-to-day management of the subsidiary. It should also be noted that the lack of autonomy reflected in the total centralisation of decision-making and the high level of formalisation adversely affected the subsidiary’s performance, which according to the interviewees, is because the crucial decisions for the subsidiary are taken by people who are unaware of the exploration of lode mines, which goes against the conclusion of the study on Japanese companies by Kawai and Strange (Citation2014), which argues that the autonomy variable does not affect the subsidiary’s performance. Also, the argument that the persistence of cultural and institutional differences requires some subsidiaries’ autonomy is found only in the subsidiary’s operational autonomy (Brenner & Ambos, Citation2013b).

5.2. Organizational culture

The organisational/local culture variable assumes relevance in this case study, as the subsidiary under analysis has a very peculiar culture, given its long history in terms of culture. Precisely because of this historical and cultural issue, the local managers communicate the subsidiary’s mission, vision, and strategy to the rest of the staff to align with the intended organisational objectives. However, these objectives will have to be reviewed, compared to what was planned, with some frequency depending on market conditions, in which Director C states that “The organisational culture of the subsidiary is different from that of the parent company, as the cultural influences are very distinct; the expatriates/shareholders like everything to go according to plan, not liking last-minute changes or surprises, now as we know, the Portuguese are no longer like that!”. This statement reveals the degree of aversion to uncertainty on expatriates and the parent company, which generates difficulties in the relationship between this subsidiary and the parent company, as stated by Chakrabarti et al. (Citation2009).

In these statements, as well as during the on-the-spot interviews (by facial expressions and tone of voice), there was some crisis and cultural conflict between the local staff and the Expatriate Administrator, and also that a climate of mistrust persists between them, in which there was no attempt to bring the Expatriate Administrator closer as a representative of the parent company, because “…he has much respect for his hierarchical superiors in the parent company, which has to do with their culture” and ”… The fact that there is some difficulty of communication (due to the lack of a common language) between the subsidiary and the parent company also makes the expatriate/shareholders extremely suspicious…” claim Director D and Director C, respectively; these opinions are also supported by Director E who understands that the expatriate/shareholders do not know how to motivate people to achieve a given objective, because “…they are terrible at communicating and are arrogant…” which corroborates the reservation by Chakrabarti et al. (Citation2009), who pointed out that cultural conflicts between the subsidiaries and the parent company depend on the rigidity of the hierarchical structure and the level of collectivism and individualism.

The subsidiary’s organisational culture is based on its history, community culture, and country. In this sense, Director C claims that ”…the local organisational culture is based on the Portuguese culture and mainly on the subsidiary’s historical culture. This cultural constraint also implies in itself that the control of results is tighter”. That is, the fact that there are cultural differences between the subsidiary and the parent company, lack of knowledge of the business (seam mines) implies that the parent company feels the need to control any financial and non-financial operation that the subsidiary carries out, which leads the local staff to conclude that the control exercised by the subsidiary is high.

The fact that the parent company does not understand the changes that take place concerning what is planned due to new situations reveals an aversion to uncertainty, which according to Hofstede (Citation1980), is high in the culture of the country of origin of the capital, that is, uncertainty must always be avoided. The local management also stresses that the subsidiary’s organisational culture has not changed concerning the culture of the country of origin of the parent company. However, there is an attempt to overcome these cultural differences when they become obstacles to good relations with the parent company. Most of these situations arise because the parent company has no mining tradition. According to its guidelines, this lack of mining tradition has led to a change in how the mine is exploited between 2007 and 2015. In other words, the aim was only ”…to remove the good ore..” to compensate for its low price, but ”…the ore content has to be high to compensate, which would be an ambitious mining situation—if only the excellent ore were removed, the future of the mine would be compromised -! “argues Director E. This makes it possible to argue that the parent company’s understanding of the subsidiary and its host country’s organisational culture and its tradition of producing this ore is fundamental, as Giraud et al. (Citation2011) claim, which in this case did not happen.

Also, the management style of the parent company, reflected in the Expatriate Administrator’s posture, was not adapted to the specific characteristics of the organisational/local culture of the subsidiary, which does not corroborate the conclusions of Icfai (Citation2006) and Giraud et al. (Citation2011), here control was exercised merely as a technique, not taking into account the culture already existing in the subsidiary. Some of the parent company’s controls are also related to the culture of its country of origin, namely, cultural controls (Jaeger & Baliga, Citation1985).

Still, concerning the organisational culture of the subsidiary, Director G admits that this is “…sui generis…”, as “…a family…”, something that, for the local staff, was never understood by the Expatriate Administrator, who always made a point of not taking root in the local community and separating his personal life from his professional life, by not including his family in the arrangements organised by them and not participating in most of them. The non-adaptation of the expatriate was mentioned by Harvey et al. (Citation2001). Once again, there is a certain degree of acculturation between people of different cultures, making relations between them difficult. When relocated by the parent company to a subsidiary, this is a risk that the expatriate runs (Barkema et al., Citation1996; Harvey et al., Citation2001). This acculturation is still evident in the Expatriate Administrator’s expression when he affirms that “…they were malicious…”, that is, he understands that some local executives did not place the objectives of the mother company as priorities, which generated severe conflicts.

Caldas and Tonelli (Citation2002) s conclusions regarding cultural integration are also confirmed, in which it is dependent on whether or not there is resistance to change by the parties involved. Those of Tanure et al. (Citation2011) regarding the challenge that this integration constitutes have not been confirmed, as well as the alignment of values referred to by Zago and Retour (Citation2013), since there has been no mitigation of the effects of different cultures, nor the construction of a chain of shared values and, consequently, their alignment. It is also confirmed that it is important for the parent company to understand the host country’s culture, as it is linked to managers culture, influencing control (Giraud et al., Citation2011). Therefore, the task of adequately integrating the parent company referred to by Kostova and Zaheer (Citation1999) was not achieved, as the latter did not show any openness to it.

5.3. Legitimacy

Concerning the variable legitimacy/confidence that the local management feels for the parent company, this is considered relative by the latter, as Director D explains, ”My contribution is important and legitimate, but always following the guidelines of the parent company.” and ‘…it is merely operational…’ admits Director B, in whose statements the other local management review. It should be noted that for the local management, this variable is directly related to the autonomy held by the subsidiary, which, as we have seen, does not exist. On the other hand, the local executives feel that the parent company trusts in the way they carry out their functions, in terms of ethics and suitability, although the fact that they are questioned countless times on the same subjects may indicate some mistrust, that is, ”… although at times the way the Japanese act (of confirming everything two and more times) might indicate that there was some mistrust”, concludes Director C. It should be noted that the local staff who were not endowed with legitimacy/confidence by the parent company left the subsidiary, as the same director says.

Legitimacy/confidence is related to the alignment of objectives. Although this alignment of local frameworks takes place, it is not a pro-quo condition for this legitimacy to be evident in practice and sufficient for them to feel it in its entirety since they understand that they only have operational autonomy and have not been delegated decision-making power in the areas for which they are responsible. This alignment is mentioned by Hoppmann (Citation2008). This legitimacy’s role is crucial in solving the problems of control of the parent company vis-à-vis the subsidiary (Brenner & Ambos, Citation2013b). The legitimacy/confidence felt by local management is in the sense that they apply the principles/decisions of the parent company Granlund and Lukka (Citation1998), in which they adopt the position of the building and maintain the trust of the Expatriate Administrator and the parent company (Nixon & Burns, Citation2005).

5.4. Non-networking

Concerning the networks variable, i.e. network operation, this variable is fundamental to the parent company’s exercise of control in its dispersed subsidiaries (Ensign, Citation2007). However, the subsidiary under analysis does not operate in a network with the parent company, mainly because of the scarcity of financial resources to invest in an integrated information system, because the computer system and the information system (accounting, salaries, purchases, inventories, payments, and fixed assets) are not integrated, which implies substantial investment in software, personnel, and training, which “…has never been considered a priority by the parent company…” claims Director C. In fact, during his interview, he pointed out an improvement in an integrated information system for processing information. In this context, all the information requested by the parent company is prepared in Excel files sent to the parent company to be introduced into the parent company’s software for this purpose. Director C also adds that the existing software in the subsidiary “…is of poor quality concerning the parent company’s requirements” but emphasises that ”..over the years there has not been any information requested that has not been provided”.

For the Expatriate Administrator, this gap is justified because the staff of the subsidiary show ”…reluctance to transmit their knowledge. In management, it is important to create a system that transmits knowledge to other people, to improve what exists in the company, but this has not yet been done”. This reluctance can be related to the degree of acculturation already mentioned, because the manager is seen as a strange person, who has never shown openness to adapt to the procedures and culture of the subsidiary, and also because, in the dialogues/communication with the local staff, he transmitted his ignorance about the topics under discussion, which did not help him (Giraud et al., Citation2011).

In short, the subsidiary does not operate in a network with the parent company, and there is no integrated computer system but several applications at the local level. Correcting this situation implies a significant investment, which has not been considered a priority by the parent company, leading to all financial and non-financial information having to be worked on manually to meet the information and output requirements (control of results) by the parent company, since the performance of the existing software is precarious. For the shareholder, the section heads’ qualifications and their resistance to change also influence the performance of the system and an eventual investment.

The subsidiary does not operate in a network that prevents both parties’ benefits. However, it is not associated with its degree of autonomy, making it possible to refute the arguments (Gammelgaard et al., Citation2012).

Networking is an integral part of an integrated information system and is included in the main control level of the adopted analysis model. Although this operation does not exist in the subsidiary, it influences how results control is exercised and the number of indicators required. This situation also leads to increased costs. The additional work that the preparation of the intended information entails contradicts what was argued by Keupp et al. (Citation2011), i.e. the subsidiary under analysis is not endowed with autonomy. On the contrary, it has increased expenditures caused by tight results control.

Regarding the performance of the existing information systems in the subsidiary, it is concluded that they are incipient to respond proactively to the parent company’s requirements. However, they are still the basis of the MCS and the information prepared is still reliable (Moilanen, Citation2008).

In this way, the local executives understand that various factors explain the high level of control and the exact characteristics of the MCS, such as the culture of the country of origin, the high mistrust, the lack of knowledge of the activity, the uncertainty as to the return on the investment made, the lack of network operation, the lack of comparability of the information with other mining subsidiaries.

6. Conclusions

The results obtained in this research allowed the following conclusions to be drawn. Local managers feel they have legitimacy but not autonomy since the entire decision-making process and strategic planning is centralised in the parent company. The subsidiary only has autonomy in managing the means of production, safety and environmental issues. In short, the subsidiary only has operational autonomy and opinions on decisions taken can be accepted or not by the shareholder. In this sense, although the annual budget is prepared locally, it must be communicated, discussed and approved by the parent company. There is a high level of centralisation of decision-making and an aversion to uncertainty on the part of the shareholder. The expatriate also has relative autonomy vis-à-vis the parent company and is very dependent on the opinions of local administrators for lack of knowledge of mining activity. Also inherent in the country of origin culture, the expatriate has total respect for his or her hierarchical superiors.

So, the subsidiary’s organisational structure, mirrored in its organisation chart, is vertical and with well-defined authority levels written in the job description of the local management. However, communication with senior managers in the parent company is prolonged and time-consuming. Additionally, organisational culture has been considered historical and rooted in local culture for several decades. Since the beginning of mining activities, this culture has always been passed on to employees by managers. Today, for many of the local staff underlying the organisational culture, this company is considered a social enterprise for employees at the lowest hierarchical levels. It has social obligations towards them. The parent company’s culture implicit in the subsidiary is not understood. Adopted postures and communication failures have not strengthened this link to local and employee values during these 8 years. Thus, there was some resistance to the existing control system’s changes to the model intended by the parent company, which meant that some of their demands had not been concluded and implemented. However, the local management does not feel any cultural influence of the parent company in the way it carries out its functions and feels respected by it. However, the local staff of the subsidiary feel that there is a certain degree of legitimacy/confidence in the performance of their duties, but with some limitations resulting from the attitude of the most suspicious expatriate/shareholders, of being slower to make decisions and asking for the same information over and over again as a result of their own culture.

In the light of the previous, it is argued that the MCS (and its characteristics) implemented in the subsidiary is related to the degree of integration of the latter in the parent company/cultural integration. However, in that subsidiary, the MCS resulted from more than one imposition of the parent company, which materialises in the high degree of control exercised by the latter, in which the bureaucratic controls stand out.