Abstract

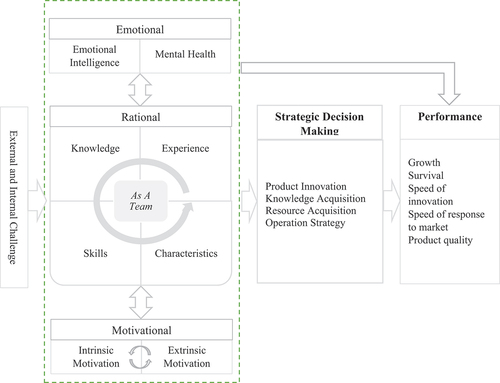

This study aims to identify the factors that must be present when founders develop start-ups and why these factors affect the success of start-ups. Despite the importance of founders’ involvement in start-up success, few studies have specifically and comprehensively focused on founders as the main factor in start-up success. This study presents an integrative literature review of start-up success studies published between 2010 and 2020 on the Web of Science. The study finds that the main founder-related factors that influence start-up success can be categorized as Knowledge, Experience, Competence, Characteristics, and Founding Team (KECCT). KECCT determinants have a substantial impact on strategic decision making, which ultimately determines start-up performance. The dynamic process that founders need to follow in building successful start-ups is described as the start-up success framework. The start-up success framework can be used for further research and by practitioners in developing start-ups. Our review indicates that previous studies have put more emphasis on the cognitive (rational) characteristics of the founder. Based on the Trilogy of Mind Theory, we add the emotional and motivational characteristics of the founder that contribute to the success of a start-up. Our proposed framework, the ERM Model, also enriches the upper echelons theory.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study aims to identify the factors that must be present when founders develop start-ups and why these factors affect the success of start-ups. Despite the importance of founders’ involvement in start-up success, few studies have specifically and comprehensively focused on founders as the main factor in start-up success. This study presents an integrative literature review of start-up success studies published between 2010 and 2020 on the Web of Science. Our review indicates that previous studies have put more emphasis on the cognitive (rational) characteristics of the founder. Based on the Trilogy of Mind Theory, we add the emotional and motivational characteristics of the founder that contribute to the success of a start-up. Our proposed framework, the ERM Model, also enriches the upper echelons theory.

1. Introduction

Founders are the most important variable in start-up success, and the start-up development process is often seen as a “one-man show” (Braun et al., Citation2017), where founders act as “creative destroyers” (Schumpeter, Citation1934) to find (Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000) or create opportunities (Alvarez et al., Citation2013). Researchers have attempted to determine what enables founders to succeed in creating and developing start-ups (Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000), and the individual characteristics of founders have been used extensively to explain why some start-ups achieve success whereas others fail (Boden & Nucci, Citation2000). Founders must innovatively launch start-ups, specifically using the creative activities of opportunity identification, problem solving, and the implementation of ideas (Lazear, Citation2005). The main issue that founders encounter when developing start-ups is that the success rate is low (Marmer et al., Citation2011). Most start-ups cannot achieve rapid growth or do not grow at all (Morris, Citation2011). Given the uncertainty in the development of start-ups, which frequently encounter setbacks and even failures, founders often feel frustrated and reluctant to continue with their businesses (Shane et al., Citation2003).

Despite the importance of founders’ involvement in start-up success, the most recent literature on start-ups still focuses on how to build a new company (Shepherd et al., Citation2020) and the role of inspirational entrepreneurs in the entrepreneurship process (Wartiovaara et al., Citation2019). There is limited research that has specifically and comprehensively viewed founders as the main factors in start-up success. By looking at these factors specifically and comprehensively, researchers may be able to provide a broad and in-depth picture for practitioners who want to develop start-ups. As a result, this study’s research questions are as follows:

What features of founders can influence start-up success?

Why do these factors affect start-up success?

To answer the research questions, an integrative literature review study is conducted (Torraco, Citation2005) which summarises previous research on start-up success. In addition, to acquire a more comprehensive view, a backward snowball method is applied (Wohlin, Citation2014). In this study, the research is initiated by describing start-ups, discussing the methodology utilized, and identifying relevant variables. A literature analysis is then conducted to answer the research questions and categorize the results of the analysis. Finally, in the form of a start-up founder framework, the final conclusions of the research are discussed.

The contributions of this research are as follows. Firstly, the findings map factors that influence start-up success from the founder’s perspective and why these factors are important. Secondly, the study lists strategic elements that are important concerns for business founders. Thirdly, the research establishes important indicators related to start-up performance. Fourthly, and most importantly, this study offers a start-up founder framework (Hambrick & Mason, Citation1984). This framework can be used as a guide for researchers in investigating additional factors related to founder success when developing start-ups and also contributes to existing discoveries in strategic management and entrepreneurship. Founders can use the framework as a guide to map the elements that affect them and the strategies that they need to use to grow their businesses. This action may help in reducing the number of start-ups that fail in the early stages.

2. Start-ups, entrepreneurship, and founders

A start-up is the initial stage of a company’s life cycle (Daily & Dalton, Citation1992) and represents a temporary organization designed to seek a scalable, iterative, profitable, and sustainable business model (Blank & Dorf, Citation2012). One characteristic of start-ups is that their organizational structure is often disorganized, even tending to be liquid (Davidsson & Gordon, Citation2009) and faces “liability of newness” (Stinchcombe, Citation1965) and “liabilities of smallness” (Aldrich & Auster, Citation1986).

There is a significant relationship between start-ups and entrepreneurship; therefore, the role of the founders becomes crucial and dominant in the start-up development process. One of the fundamental concepts of entrepreneurship is a focus on the individual. Entrepreneurship is a process of value creation and appropriation led by entrepreneurs in an uncertain environment (Mishra & Zachary, Citation2015). Founders of companies in the start-up phase are called nascent entrepreneurs, or individuals actively involved in establishing a new venture (Aldrich & Ruef, Citation2006). In this study, the term start-up founders refers to individuals or team (co-founders) members who are actively engaged in entrepreneurial activities to form a new company.

3. Method

In this study, an integrative literature review approach is used with the goal of assessing, criticizing, and synthesizing existing literature in a way that allows for new frameworks and perspectives (Supriharyanti & Sukoco, Citation2023; Torraco, Citation2005). The literature review includes all research related to start-up success published over the last 10 years. The Web of Science database, the world’s leading scientific citation search and analytical information platform (Li et al., Citation2018), was used to conduct the literature search using the keywords “start-up” and “performance”. These keywords were chosen to obtain broad initial results. From the initial results, 441 studies were found. In the process of identifying relevant and high-quality literature related to the research topic, inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied based on a practical plan and an assessment of the quality of the selected literature (Mudzakkir et al., Citation2022; Snyder, Citation2019). Firstly, literature unrelated to start-ups was excluded, such as studies in the context of ventures or corporations, venture capital, and start-ups founded by established companies. Secondly, the search only included research published between 2010 and 2020 in journals that meet Q1 criteria based on the Scimago Journal and Country Rank. Q1 journals are a collection of 25% of the highest-quality journals on the Scimago Journal and Country Rank list. Selecting papers from top-tier journals ensures that the papers chosen meet high quality requirements (quality stamp) and can be considered official sources of knowledge and information (Harvey et al., Citation2010; Hasanah et al., Citation2023). After applying the exclusion criteria and analysing the abstracts, 74 articles were screened, copied, and used as the foundation of the analysis.

Collecting data using an integrative literature review approach requires more creative data collection because the main goal is not to cover all journals that have been published on the same topics, but to combine perspectives and insights from various fields or research traditions (Snyder, Citation2019). As a result, to get a broader idea of the factors that influence the success of start-ups, a backward snowball strategy was used to select papers related to the topic and research objectives (Wohlin, Citation2014). The process of documentation and codification of the literature review was conducted using NVivo12 software.

4. Data analysis

Based on the integrative review of start-up success data analysis, we categorized the determinants of start-up success in terms of the founder’s characteristics as follows: Knowledge; Experience; Competence; Characteristic; and As a Team (KECCT), as shown in Appendix 1. Further descriptions of the relationship among categories and details of the benefits founders get from these factors are presented in .

4.1. Founders’ knowledge

Extensive knowledge and information are required to build a start-up (Aldrich & Ruef, Citation2006) because most of the activities carried out by entrepreneurs are related to previous knowledge and experience (Chwolka & Raith, Citation2012). This previous experience allows founders to more effectively manage their limited resources to exploit opportunities (Wales et al., Citation2013). Specifically, founders become aware of what needs to be done to achieve certain goals, are able to avoid past mistakes, and are faster and more adept at taking entrepreneurial action (Farmer et al., Citation2011). Based on the results of the analysis, the knowledge that founders must possess includes technical and product-related knowledge, market-related knowledge, and business environment-related knowledge. Technical knowledge is useful for commercializing the first product (Song et al., Citation2010), whereas knowledge of products related to product capabilities are useful in developing new products (Moorman & Slottegraaf, Citation1999) and exploiting opportunities (Martin & Javalgi, Citation2016). Knowledge of the market is particularly useful in new product development (Adams et al., Citation2015), whereas knowledge about whether the business environment can be controlled or presents profit/loss opportunities is the key to business success (Marion et al., Citation2015).

4.2. Founders’ experience

Founders’ experience is important in the entrepreneurial process and is positively related to business success (Staniewski, Citation2016). Serial entrepreneurs usually have better results than novice entrepreneurs (Delmar & Shane, Citation2006). In addition, most entrepreneurs have worked in other organizations before establishing their start-ups (Burton et al., Citation2016). Based on the results of the analysis, some of the experience required in start-up development are in the fields of managerial, technological, start-up procedures, and industry.

Managerial experience plays a role in organizing start-ups (Van Praag, Citation2005). Influential managerial experiences include business planning (Dencker et al., Citation2009) and experience in assembling and managing a constellation of resources (Baert et al., Citation2016). In addition, founders with more entrepreneurial and management experience are able to identify more market opportunities in a highly dynamic external environment (Dencker & Gruber, Citation2015; Gruber et al., Citation2012).

Technological experience has an impact on the amount of external knowledge that can be used to identify potential opportunities and is also useful for reducing product development risks and costs (Gruber et al., Citation2013). Previous start-up experience is a key element of start-up success (Marvel et al., Citation2014) because it has an impact on entrepreneurial and innovation processes (Farmer et al., Citation2011) and start-up viability (Delmar & Shane, Citation2006) regardless of whether the previous start-up resulted in success or failure (Parker, Citation2014). With this experience, founders can transfer previously learned routines and skills to the next start-up (Baron, Citation2006; Eesley & Roberts, Citation2012), thereby making decisions and taking action more quickly (Forbes, Citation2005). Founders with this experience are also better at understanding the market; pursuing, responding, and taking advantage of opportunities that exist in the market (Davidsson & Honig, Citation2003); and understanding the direct relationships between internal and external resources (Mosey & Wright, Citation2007).

Industry experience is important because the knowledge contributes to a company’s performance, survival, and growth (Baron, Citation2006; Cassar, Citation2014). This experience is useful in pursuing opportunities in a less dynamic external environment (Dencker & Gruber, Citation2015) and facilitating founders in pattern recognition and awareness of industry trends and the business environment (Baron, Citation2006). Founders may also have tacit knowledge regarding the technology, products, design processes, and value chains specific to the industry (Eesley & Roberts, Citation2012). In addition, founders also benefit from a pre-existing network of suppliers, investors, and customers (Lafontaine & Shaw, Citation2016; Park et al., Citation2020) as well as family and friends (Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, Citation2021).

4.3. Founders’ competencies (founders’ skills)

Founder skills provide confidence in developing start-ups because founders will reduce their efforts if they think they do not have the necessary skills to complete certain activities (Townsend et al., Citation2010). Based on the analysis, some of the skills needed in start-up development are management skills and political skills. Management skills are important in the process of innovation (Beckman, Citation2006) and can subsequently affect start-up performance (Kim & Steensma, Citation2017). In resource management, these competencies are useful in accumulating, integrating, and combining internal and external resources, and in the case of start-ups, these tasks are the responsibility of the founder (Baert et al., Citation2016). Founders who have management skills are better at overcoming obstacles related to start-up creation and growth (Brinckmann et al., Citation2011). In addition, political competence is useful in understanding the market, pursuing opportunities with higher probabilities of success (Elfring & Hulsink, Citation2003), and gaining access to external resources (Voudouris et al., Citation2017).

4.4. Founders’ characteristics

The characteristics of the founder have an effect on start-up progress (Brown et al., Citation2019). Based on the data analysis, important founder’s characteristics are self-efficacy, creativity, innovativeness, risk taking, and gender. Founders’ self-efficacy influences entrepreneurial intentions and business creation, which affect start-up performance (Baum & Locke, Citation2004). When facing setbacks or high uncertainty, founders with low self-efficacy will have a negative effect on their businesses or even stop developing their start-ups (Baum & Locke, Citation2004). Conversely, founders with high self-efficacy can manage stress better when facing environmental threats (Baron et al., Citation2013) and can improvise throughout the start-up development process, during which improvisation can improve start-up performance (Hmieleski & Corbett, Citation2008).

Founders are the main actors in the innovation process, particularly as a source of creativity (Ahlin et al., Citation2014). There is a positive relationship between organizational innovation and the subsequent viability of the start-up (Helmers & Rogers, Citation2010). The founder’s creativity and ability to innovate are useful for finding and identifying opportunities where new technologies may be used (Shane, Citation2000) and attracting potential investors and business partners (Wiklund & Shepherd, Citation2005).

Risk taking is a prominent characteristic of the field of entrepreneurship which requires bold risk taking (Brockhaus, Citation1980). Existing research has found that entrepreneurial activities such as the commercialization of the first product are often initiated by a strategic disposition that reflects a start-up’s level of propensity towards innovative behaviour and risk taking (Ahmadi & O’Cass, Citation2018). Founders with a greater willingness to take risks are more likely to pursue innovations that are risky ex ante (Forlani & Mullins, Citation2000). In terms of gender, Muñoz-Bullón and Cueto (Citation2011) found that female founders had a lower start-up survival rate than male founders. Women also have greater difficulties accessing capital than men (Caliendo & Kritikos, Citation2010). Start-ups run by female founders also appear to be more vulnerable due to low human resources and engagement (Fairlie & Robb, Citation2009).

4.5. Founding team

Most start-ups work in teams of two or more people (Davidsson & Honig, Citation2003) and the effectiveness of the founding team is critical to start-up success. Several studies have found that human capital support from founding teams can affect organizational performance and viability (Beckman, Citation2006). Moreover, businesses founded by teams tend to perform better (Kamm et al., Citation1990). Therefore, the founders’ collective skills play a key role in shaping the start-up strategy (Delmar & Shane, Citation2006).

Based on the data analysis, two factors that affect the success of start-ups are a founding team with experience working together and the diversity of the team. Founding teams that have worked together before have better start-up success because teams that have worked together can form a transactive memory system. Transactive memory systems refer to the sum of individual knowledge, expertise, and shared understanding, that is, “who knows what” (Zheng, Citation2012, p. 579). There is a positive relationship between the founding team’s transactive memory system and start-up performance (Zheng, Citation2012). A founding team with previous joint experience is able to develop collective perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours among organizational members to create a human resource value system (Leung et al., Citation2013).

Diversity is critical to start-up success (Leung et al., Citation2013). For example, team diversity is linked to educational background (Gruber et al., Citation2012). A diverse team of founders can work more effectively because the skills possessed by team members can complement one another, increasing start-up performance (Beckman & Burton, Citation2008). The combination of a diverse team that has worked together before will be more beneficial as the team is more likely to pursue an exploratory strategy to change the founders’ ideas and grow faster (Beckman, Citation2006). In addition, venture capitalists value teams with diverse educational backgrounds as long as one of the members has management education (Franke et al., Citation2006).

5. Framework upper echelons—ERM

Our review indicates that previous studies place more emphasis on cognitive (rational) characteristics of the founder. However, based on the Trilogy of Mind Theory (LeDoux, Citation2002), cognitive characteristics are not enough to define the founders. Emotional and motivational factors are needed (Huy & Zott, Citation2019) to understand the behaviours of founders that have start-up success. Therefore, we propose a framework that consists of three psychological factors of founders that facilitate the development of successful start-ups; the emotional, rational, motivational model (ERM Model, Figure ). The framework itself enriches the upper echelons theory (Neelyet al., Citation2020), particularly in the roles of the founders as team members and the role of the leader not only based on characteristics, but also based on knowledge, experience, and skills to make start-ups successful.

From left to right, the relationships in our framework are depicted using straight arrows, where the initial relationship shows that the start-up’s external and internal challenges are the driving factors for ERM (Emotional, Rational and Motivational) founders. Furthermore, the ERM characteristics of the founders guides strategic decision making which ultimately determines start-up performance. The term strategic decision making (Burgelman et al., Citation2018) is used to emphasize how founder ERM is reflected in decision quality and other features of founder decisions in the startup development process.

As noted in the previous data analysis, the external challenge that founders have to face is to scan, identify, and understand their highly dynamic external environment. Founders’ appraisal processes in perceiving potential harm/loss, threat, challenge, or benefit (Dewe et al., Citation2012) depend on the interaction between their environment and their coping resources. Founders will adapt their responses to the business environment based on the perceived need for action when goals and expectations of outcomes are not being met (Chell, Citation2000; Haynie et al., Citation2012). The internal challenges that founders must face are how they can optimize their internal resources and how they can connect existing internal and external resources. Therefore, founders need to balance internal needs, such as structure and resources, with the instability and uncertainty of the business environment (Duncan, Citation1972; McKelvie et al., Citation2011; McMullen & Shepherd, Citation2006).

To use external and internal challenges to their competitive advantage, the founders need the characteristics that we call ERM factors, and each of these factors is dynamic. In the emotional dimension, when facing a dynamic environment, the founder is required to be able to respond quickly to changes so that it is possible to affect the emotional founder (Baron, Citation2008). In the rational dimension, the founder must always upgrade his knowledge, experience, characteristics, and skills to continue to compete in a dynamic business environment. In the motivational dimension, the founder’s motivation is dynamic and can change during the process of developing a start up (Elfving, Citation2008).

There are two facets of the emotional characteristics of founders: emotional intelligence and mental health. Emotional intelligence is often associated with a person’s success at work and in life (Brackett et al., Citation2011). Individuals with high emotional intelligence have stable emotions, are better able to motivate themselves, have self-awareness, and have better social skills (Mayer et al., Citation2004). Founders need these skills to remain calm in stressful conditions. For example, in difficult conditions, individuals who have difficulty managing their emotions may make irrational decisions (Thompson et al., Citation1988), whereas individuals with high emotional intelligence are able to make better decisions (Brown et al., Citation2003). In addition to helping in decision making, emotional intelligence also plays a role in maintaining motivation and persistence and better managing social relationships (Cardon et al., Citation2012). In addition to emotional intelligence, founders also need good mental health. In the field of management, mental health is often referred to as General Mental Ability (GMA), which is an individual’s capacity for general information processing, including reasoning, problem solving, and using higher order thinking skills (Gottfredson, Citation1997). Individuals with high GMA have better creativity and problem-solving abilities (Kuncel et al., Citation2001). In the case of companies, business owners who have poor mental health (depressed mood, tension) will compromise the economic performance of the company over time (Gorgievski et al., Citation2000, Citation2010).

Based on our review, we grouped rational factors into four main factors: knowledge, experience, characteristics, and skills (KECS). The emphasis on rational factors reflects the need for continuous learning throughout the entrepreneurial process to explore, discover, and pursue new business opportunities (Minniti & Bygrave, Citation2001; Schumpeter, Citation1934; Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000). Learning and knowledge are essential to start-ups and their success (Levinthal & March, Citation1993). In addition, the learning process means that start-up development is carried out in stages, sequentially and evolutionarily, and does not depend on “eureka” moments (Alvarez & Barney, Citation2007; Baron, Citation2006). Learning can be done by observing (vicarious learning) or by doing (learning by doing). Learning by observing (vicarious learning) is needed to exploit entrepreneurial opportunities (Shane, Citation2000), in which recognizing opportunities as the initial step for the founders (Martínez-Cañas et al., Citation2023; Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, Citation2021). In observational learning, founders observe what founders of other organizations are doing. Learning by doing is necessary because most important information and knowledge needed to exploit opportunities can only be learned through experience (Hebert & Link, Citation1988).

The last necessary characteristic of founders is motivation. The founder’s motivational characteristics are grouped into two categories: intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation. There are two major theories often used by researchers in categorizing entrepreneurial motivation: Incentive and Drive-Reduction Theory (Hull, Citation1943) and Push and Pull Theory (Gilad & Levine, Citation1986). Carsrud and Brännback (Citation2011) categorize entrepreneurial motivation into intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation emphasizes the founder’s interests, while extrinsic motivation places more emphasis on rewards obtained external to the founder (Carsrud & Brännback, Citation2011). However, extrinsic motivation includes things that are intangible such as status, power, and social acceptance and tangible things such as money and other forms of compensation (Carsrud et al., Citation2009). The founder’s greatest motivation is to succeed, which can be termed the “need to achieve” (Prokopenko & Kornatowski, Citation2018). Therefore, to simplify the categorization of founder motivation we propose to categorize entrepreneurial motivation into Tangible Motives and Intangible Motives. Tangible motives are the founder’s motivation to achieve physical accomplishments. Intangible motives are the founder’s motivation to achieve to get inner satisfaction.

Furthermore, ERM founders become a determinant in strategic decision making. In start-ups, as the holder of authority and legitimacy, the founder is the main decision maker (Gedajlovic et al., Citation2004), both formally and informally. Therefore, start-ups rely heavily on founders when making strategic decisions (Nelson, Citation2003) and strategic decisions have a vital influence on start-up performance (Wasserman, Citation2012). This condition continues until the growing start-up reaches a significant size threshold (Daily & Dalton, Citation1992). The founder’s role in strategic decision making is to carry out strategic start up functions including Product Innovation, Knowledge and Resource Acquisition, Operational Strategy, and Learning. Product Innovation refers to the creation and introduction of new products that are different from existing products (Hull & Covin, Citation2010) and are crucial for maintaining a competitive advantage (Teece, Citation2007). Knowledge Acquisition is needed to create, distribute, and utilize knowledge to gain a sustainable competitive advantage (Rahimli, Citation2012). Resource Acquisition aims to obtain valuable, rare, and immutable resources so as to produce superior performance (Barney, Citation1991). Operational Strategy serves to determine policies and plans for the use of organizational resources to support a long-term competitive strategy (Reid & Sanders, Citation2019). Finally, learning helps founders make better decisions and take broader action when faced with ambiguity and uncertainty (Minniti & Bygrave, Citation2001).

Finally, the ultimate goal of our framework is start-up performance. The main indicators of start-up performance are survival and growth. Survival means that start-ups can continue to survive in the face of external and internal challenges and founders can continue to learn how to develop their start-ups. We use three growth indicators: inputs (investment funds, employees), business value (assets, market capitalization, economic value added), and outputs (sales revenues) (Garnsey et al., Citation2006). If one of the three indicators is positive, the start-up can be considered to be experiencing growth. In addition, we also added several additional indicators pertaining to product development (Giardino et al., Citation2016). Most start-ups fail due to self-destruction compared to the competition (Marmer et al., Citation2011). Product quality in start-ups is different from product quality in mature companies. The product quality start-up indicator is the Minimum Viable Product (MVP), where “MVP is a version of a new product, which allows a team to collect the maximum amount of validated learning about customers with the least effort” (Ries, Citation2011). Based on the definition of MVP, start-ups need to respond quickly to the market and innovate quickly to achieve success. Speed of response to the market is needed because start-ups generally develop products for very specific markets without knowing what customers want (market uncertainty) (Blank, Citation2013). At start-up, the speed of response to market strategy generally uses two approaches: first-mover strategy and fast-follower strategy. The first-mover strategy states that the first product to enter the market will get a larger profit and market share (Kerin et al., Citation1992). At the same time, the first-mover strategy also carries a high risk of failure. The fast-follower strategy is an alternative strategy to minimize the risk of the first-mover strategy. The key to both strategies is that the greater the speed of response to market a product, the greater its competitive advantage (Kessler & Chakrabarti, Citation1996). Meanwhile, speed of innovation is needed in a highly competitive environment (Kessler & Chakrabarti, Citation1999) and in companies facing rapid technological change (technological uncertainty) (Parry et al., Citation2009).

6. Discussion

Based on the premise of the upper echelons theory that the organization is a reflection of its top executives (Hambrick & Mason, Citation1984), the founder is the most important factor in the context of start-ups or entrepreneurship (Cheng & Tran-Pham, Citation2022). Finkelstein et al. (Citation2009) also stated that if we want to understand organizational strategy, we must understand the strategists within the organization. However, in the start-up context, modifications to the upper echelons theory are needed. It is necessary to modify the upper echelons theory for the following two reasons. First, the theory was originally intended for established companies. The most striking difference between established companies and start-ups is that start-ups have “liability of newness” (Stinchcombe, Citation1965) and “liabilities of smallness” (Aldrich & Auster, Citation1986) as constraints, so start-ups are more vulnerable and have more limited strategies than mature companies. Second, upper echelons theory emphasizes cognitive factors as a determinant of strategic choice. Referring to the Trilogy of Mind, cognitive factors are not the only human factors; there are also affective and conative factors that influence human behaviour (LeDoux, Citation2002). Therefore, it is necessary to add these two factors to the upper echelons theory. For example, founders’ emotions can significantly influence their entrepreneurial thinking and behaviour (Baron, Citation2008; Cardon et al., Citation2009). In addition, how founders manage or regulate their own emotions; such as pain, disappointment, and frustration or surprises that arise during the start-up development process will affect the amount and quality of effort and resources they dedicate to the start-up development process (Huy, Citation2002). According to research conducted by Freeman et al. (Citation2015, p. 8), 72% of entrepreneurs, either directly or indirectly experience mental health problems, with depression being the most common disorder experienced by founders (30%), followed by ADHD (29%), anxiety disorders (27%), substance abuse (12%), and bipolar disorder (11%). On the other hand, entrepreneurial motivation is an important mechanism to explain various entrepreneurial behaviours (Carsrud & Brännback, Citation2011, p. 20). The decision to launch a start-up applies not only to those who can afford it, but also to those who have the necessary motivation to do so (Barba-Sánchez & Atienza-Sahuquillo, Citation2012). Motivation provides energy, direction, and persistence in doing something (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). Not only financial related motivation, but founders with community focused values who are socially oriented and meeting these social needs is what is most important to them might become his/her motivation (Ruiz Palomino et al., Citation2019; Ruiz-Palomino et al. (Citation2021).

The contributions of our research are, first, that we map and categorize the factors that influence start-up success from the founder’s perspective and show why these factors affect start-up success. Second, we list strategic elements that are important concerns for founders in developing start-ups. Third, we provide important indicators related to start-up performance. Fourth, and most importantly, we also offer a start-up founder framework that researchers and practitioners can use. Our framework can be used as a guide to help researchers examine other factors related to founder success in developing start-ups and also as a guide to help founders map the factors that exist within themselves and the strategies needed to develop their start-ups. This activity is useful for minimizing start-up failures.

6.1. Future research agenda

Our review of the research on start-up success from the founder’s perspective reveals many opportunities for future research considering that research on the relationship between people and start-up success is a very complex topic. Based on previous reviews and discussions about start-up success from the founder’s perspective, we propose a number of potential research questions which we believe require further research. The research questions are grouped into three categories: general questions, ERM (emotional, rational, and motivational) founder factors, and dynamic nature.

FAQ

How does upper echelons theory, in the context of start-ups, help founders achieve success and avoid failure?

What strategies can the founder choose in developing a start-up?

How does the founder choose a start-up development strategy?

How does choosing a start-up development strategy affect start-up success?

ERM Founder Question

What are the internal and external challenges that affect ERM founders?

Why and how does the ERM founder directly influence the choice of development strategy and start-up performance?

How do emotional, rational, and motivational factors influence each other in start-up development?

What is the synergy between emotional, rational, and motivational founders?

ERM Founder’s Dynamic Nature Question

What are the internal and external challenges that affect the dynamics of ERM founders?

What is the process of developing the knowledge, experience, skills, and characteristics of the founder?

Why do founders change their motivation from intrinsic to extrinsic, and vice versa, and how does this affect the choice of strategy and start-up performance?

How do founders manage their emotions in uncertain situations and how does this affect the choice of strategy and start-up performance?

7. Conclusion

Research on start-up success, especially from the founder’s perspective, is a very interesting research topic, considering that research on this topic is still not as mature as research on human capital in an enterprise context. The research we conducted is an integrative literature review of research related to founders’ factors that determine start-up success. The integrative literature review method was chosen because the main contribution of our study was the establishment of a framework (Snyder, Citation2019). We also investigated why these factors affect start-up success. Our paper concludes that founders play critical roles in start-up success. This is in line with the opinion of Rauch and Frese (Citation2007) that “entrepreneurship research cannot develop a consistent theory about entrepreneurship if it does not take personality variables into account”. What needs to be emphasized is that the personality of the founder not only relates to cognitive/rational factors but also to other factors such as the emotional and motivational characteristics of the founder, known as the Trilogy of Mind (Hilgard, Citation1980).

Public Interest Statement.docx

Download MS Word (12.5 KB)About The Author.docx

Download MS Word (15.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2284451

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Himawat Aryadita

Himawat Aryadita ([email protected]) is a doctoral candidate, Department of Management, Universitas Airlangga. He is a faculty member at Department of Information Systems, Faculty of Computer Science, Universitas Brawijaya Malang, Indonesia. His major research interests include Entrepreneurship, Startup and Product Development.

Badri Munir Sukoco

Badri Munir Sukoco ([email protected]) is a Professor at Department of Management, Director of Postgraduate School, Universitas Airlangga. He received his PhD from National Cheng Kung University. His major research interests include Strategic Alliance, Competitive Behavior, and Innovative/Imitative Behavior.

Maurice Lyver

Maurice Lyver ([email protected]) is an Assistant Professor at the DOAE, National Taichung University of Science and Technology, Taiwan. He received his PhD from National Chung Hsing University. His major research interests include Strategic Management, Alliances, Innovation, Technology Management, and Entrepreneurship.

References

- Adams, P., Fontana, R., & Malerba, F. (2015). User-industry spinouts: Downstream industry knowledge as a source of new firm entry and survival. Organization Science, 27(1), 18–17. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2015.1029

- Ahlin, B., Drnovsek, M., & Hisrich, R. D. (2014). Entrepreneurs’ creativity and firm innovation: The moderating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Small Business Economics, 43(1), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9531-7

- Ahmadi, H., & O’Cass, A. (2018). Transforming entrepreneurial posture into a superior first product market position via dynamic capabilities and TMT prior start-up experience. Industrial Marketing Management, 68(1), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.10.008

- Aldrich, H. E., & Auster, E. R. (1986). Even dwarfs started small: Liabilities of age and size and their strategic implications. Research in Organizational Behavior, 8(1), 165–198.

- Aldrich, H. E., & Ruef, M. (2006). Organizations evolving (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Alvarez, S., & Barney, J. B. (2007). Discovery and creation: Alternative theories of entrepreneurial action. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 1(1–2), 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.4

- Alvarez, S. A., Barney, J. B., & Anderson, P. (2013). Forming and exploiting opportunities: The implications of discovery and creation processes for entrepreneurial and organizational research. Organization Science, 24(1), 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0727

- Baert, C., Meuleman, M., Debruyne, M., & Wright, M. (2016). Portfolio entrepreneurship and resource orchestration. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 10(4), 346–370. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1227

- Barba-Sánchez, V., & Atienza-Sahuquillo, C. (2012). Entrepreneurial behavior: Impact of motivation factors on decision to create a new venture. Investigaciones Europeas de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 18(1), 132–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1135-2523(12)70003-5

- Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063910170010

- Baron, R. A. (2006). Opportunity recognition as pattern recognition: How entrepreneurs “connect the dots” to identify new business opportunities. Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(1), 104–119. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMP.2006.19873412

- Baron, R. A. (2008). The role of affect in the entrepreneurial process. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 328–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159400

- Baron, R. A., Franklin, R. J., & Hmieleski, K. M. (2013). Why entrepreneurs often experience low, not high, levels of stress: The joint effects of selection and psychological capital. Journal of Management, 42(3), 742–768. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313495411

- Baum, J. R., & Locke, E. A. (2004). The relationship of entrepreneurial traits, skill, and motivation to subsequent venture growth. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(4), 587–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.4.587

- Beckman, C. M. (2006). The influence of founding team company affiliations on firm behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 49(4), 741–758. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2006.22083030

- Beckman, C. M. & Burton, M. D. (2008). Founding the future: Path dependence in the evolution of top management teams from founding to IPO. Organization Science, 19(1), 3–24.

- Blank, S. (2013). Why the lean start-up changes everything. Harvard Business Review, 91(5), 63–72.

- Blank, G., & Dorf, B. (2012). The start-up owner’s manual–the step-by-step guide for building a great company. KandS Ranch.

- Boden, R. J., & Nucci, A. R. (2000). On the survival prospects of men’s and women’s new business ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(4), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00004-4

- Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., & Salovey, P. (2011). Emotional intelligence: Implications for personal, social, academic, and workplace success. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(1), 88–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00334.x

- Braun, T., Ferreira, A. I., Schmidt, T., & Sydow, J. (2017). Another post-heroic view on entrepreneurship: The role of employees in networking the start-up process. British Journal of Management, 29(4), 652–669. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12256

- Brinckmann, J., Salomo, S., & Gemuenden, H. G. (2011). Financial Management Competence of founding teams and growth of new Technology–Based firms. Entrepreneurship Theory Practice, 35(2), 217–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00362.x

- Brockhaus, S. R. H. (1980). Risk taking propensity of entrepreneurs. Academy of Management Journal, 23(3), 509–520. https://doi.org/10.2307/255515

- Brown, J. D., Earle, J. S., Kim, M. J., & Lee, K. M. (2019). Start-ups, job creation, and founder characteristics. Industrial and Corporate Change, 28(6), 1637–1672. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtz030

- Brown, C., George-Curran, R., & Smith, M. L. (2003). The role of emotional intelligence in the career commitment and decision-making process. Journal of Career Assessment, 11(4), 379–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072703255834

- Burgelman, R. A., Floyd, S. W., Laamanen, T., Mantere, S., Vaara, E., & Whittington, R. (2018). Strategy processes and practices: Dialogues and intersections. Strategic Management Journal, 39(3), 531–558. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2741

- Burton, M. D., Sørensen, J. B., & Dobrev, S. D. (2016). A careers perspective on entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(2), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12230

- Caliendo, M., & Kritikos, A. (2010). Start-ups by the unemployed: Characteristics, survival and direct employment effects. Small Business Economics, 35(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9208-4

- Cardon, M. S., Foo, M. D., Shepherd, D., & Wiklund, J. (2012). Exploring the heart: Entrepreneurial emotion is a hot topic. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00501.x

- Cardon, M., Wincent, J., Singh, J., & Drnovsek, M. (2009). The nature and experience of entrepreneurial passion. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 511–532. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.40633190

- Carsrud, A., & Brännback, M. (2011). Entrepreneurial motivations: What do we still need to know? Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2010.00312.x

- Carsrud, A., Brännback, M., Elfving, J., & Brandt, K. (2009). Motivations: The entrepreneurial mind and behavior. In A. Carsrud & M. Brännback (Eds.), Understanding the entrepreneurial mind: Opening the Black Box (pp. 141–166). Springer.

- Cassar, G. (2014). Industry and start-up experience on entrepreneur forecast performance in new firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(1), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.10.002

- Chell, E. (2000). Towards researching the ‘opportunistic entrepreneur’: A social constructionist approach and research agenda. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 9(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/135943200398067

- Cheng, M. C., & Tran-Pham, Q. N. (2022). How did it happen: Exploring 25 years of research on founder succession. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2150115. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2150115

- Chwolka, A. & Raith, M. G. (2012). The value of business planning before start-up — a decision-theoretical perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(3), 385–399.

- Daily, C. M., & Dalton, D. R. (1992). Financial performance of founder-managed versus professionally managed small corporations. Journal of Small Business Management, 30(2), 25–34.

- Davidsson, P., & Gordon, S. R. (2009). Nascent entrepreneur(ship) research: A review. Working paper Queensland University of Technology,

- Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00097-6

- Delmar, F., & Shane, S. (2006). Does experience matter? The effect of founding team experience on the survival and sales of newly founded ventures. Strategic Organization, 4(3), 215–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127006066596

- Dencker, J. C., & Gruber, M. (2015). The effects of opportunities and founder experience on new firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 36(7), 1035–1052. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2269

- Dencker, J. C., Gruber, M., & Shah, S. (2009). Pre-entry knowledge and the survival of new firms. Organization Science, 20(3), 516–537. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0387

- Dewe, P. J., O’Driscoll, M. P., & Cooper, C. L. (2012). Theories of psychological stress at work. In R. J. Gatchel & I. J. Schultz (Eds.), Handbook of Occupational Health & Wellness (pp. 23–38). Springer.

- Duncan, R. B. (1972). Characteristics of organizational environments & perceived environmental uncertainty. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17(3), 313–327. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392145

- Eesley, C. E., & Roberts, E. B. (2012). Are you experienced or are you talented? When does innate talent versus experience explain entrepreneurial performance? Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 6(3), 207–219. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1141

- Elfring, T., & Hulsink, W. (2003). Networks in entrepreneurship: The case of high technology firms. Small Business Economics, 21(4), 409–422. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026180418357

- Elfving, J. (2008). Contextualizing entrepreneurial intentions: A multiple case study on entrepreneurial Cognitions and perceptions. Åbo Akademi Förlag.

- Fairlie, R., & Robb, A. (2009). Gender differences in business performance: Evidence from the characteristics of business owners survey. Small Business Economics, 33(4), 375–395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9207-5

- Farmer, S. M., Yao, X., & Kung-Mcintyre, K. (2011). The behavioral impact of entrepreneur identity aspiration and prior entrepreneurial experience. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(2), 245–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00358.x

- Finkelstein, S., Hambrick, D. C., & Cannella, A. A. (2009). Strategic leadership: Theory & research on executives, top management teams, and boards. Oxford University Press.

- Forbes, D. P. (2005). Managerial determinants of decision speed in new ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 26(4), 355–366.

- Forlani, D., & Mullins, J. W. (2000). Perceived risks and choices in entrepreneurs’ new venture decisions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(4), 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00017-2

- Franke, N., Gruber, M., Harhoff, D., & Henkel, J. (2006). What you are is what you like— similarity biases in venture capitalists’ evaluations of startup teams. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(6), 802–826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.07.001

- Freeman, M. A., Johnson, S. L., Staudenmaier, P. J., & Zisser, M. R. (2015). Are entrepreneurs “touched with fire”? Pre-publication manuscript.

- Garnsey, E., Stam, E., & Heffernan, P. (2006). New firm growth: Exploring processes and paths. Industry and Innovation, 13(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662710500513367

- Gedajlovic, E., Lubatkin, M. H., & Schulze, W. S. (2004). Crossing the threshold from founder management to professional management: A governance perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 41(5), 899–912. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2004.00459.x

- Giardino, C., Paternoster, N., Unterkalmsteiner, M., Gorschek, T., & Abrahamsson, P. (2016). Software development in startup companies: The greenfield startup model. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 42(6), 585–604. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSE.2015.2509970

- Gilad, B., & Levine, P. (1986). A behaviour model of entrepreneurial supply. Journal of Small Business Management, 24(4), 45–54.

- Gorgievski, M. J., Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Van der Veen, H. B., & Giesen, C. W. M. (2010). Financial problems and psychological distress: Investigating reciprocal effects among business owners. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(2), 513–530. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X434032

- Gorgievski, M. J., Giesen, C. W. M., & Bakker, A. B. (2000). Financial problems and health complaints among farm couples: Results of a 10-year follow-up study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(3), 359–373. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.3.359

- Gottfredson, L. S. (1997). Why g matters: The complexity of everyday life. Intelligence, 24(1), 79–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-2896(97)90014-3

- Gruber, M., MacMillan, I. C., & Thompson, J. D. (2012). From minds to markets: How human capital endowments shape market opportunity identification of technology startups. Journal of Management, 38(5), 1421–1449. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920631038622

- Gruber, M., MacMillan, I. C., & Thompson, J. D. (2013). Escaping the prior knowledge corridor: What shapes the number and variety of market opportunities identified before market entry of technology startups? Organization Science, 24(1), 280–300. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0721

- Hambrick, D. C., & Mason, P. A. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. The Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.2307/258434

- Harvey, C., Kelly, A., Morris, H., & Rowlinson, M. (Eds). (2010). Academic journal quality Guide,Version 4. The Association of Business Schools.

- Hasanah, U., Sukoco, B. M., Supriharyanti, E., Usman, I., & Wu, W. Y. (2023). Fifty years of artisan entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12(46), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-023-00308-w

- Haynie, J. M., Shepherd, D. A., & Patzelt, H. (2012). Cognitive adaptability and an entrepreneurial task: The role of metacognitive ability and feedback. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(2), 237–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00410.x

- Hebert, R., & Link, A. (1988). The entrepreneur: Mainstream views and radical critiques (2nd ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Helmers, C. & Rogers, M. (2010). Innovation and the survival of new firms in the UK. Review of Industrial Organization, 36(3), 227–248.

- Hilgard, E. R. (1980). The trilogy of mind: Cognition, affection, and conation. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 16(1), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6696(198004)16:2<107:AID-JHBS2300160202>3.0.CO;2-Y

- Hmieleski, K. M., & Corbett, A. C. (2008). The contrasting interaction effects of improvisational behavior with entrepreneurial self-efficacy on new venture performance and entrepreneur work satisfaction. Journal of Business Venturing, 23(4), 482–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2007.04.002

- Hull, C. L. (1943). Principles of behavior: An introduction to behavior theory. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Hull, C. E., & Covin, J. G. (2010). Learning capability, technological parity and innovation mode use. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 27(1), 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2009.00702.x

- Huy, Q. N. (2002). Emotional balancing of organizational continuity and radical change: The contribution of middle managers. Administrative science quarterly, 47(1), 31–69.

- Huy, Q. & Zott, C. (2019). Exploring the affective underpinnings of dynamic managerial capabilities: How managers' emotion regulation behaviors mobilize resources for their firms. Strategic Management Journal, 40(1), 28–54.

- Kamm, J. B., Shuman, J. C., Seeger, J. A., & Nurick, A. J. (1990). Entrepreneurial teams in new venture creation: A research agenda. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 14(4), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879001400403

- Kerin, R. A., Varadaragan, P. R., & Peterson, R. A. (1992). First-mover advantage: A synthesis, conceptual framework, and research propositions. Journal Marketing, 56(4), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299205600404

- Kessler, E. H., & Chakrabarti, A. K. (1996). Innovation speed: A conceptual model of context, antecedents and outcomes. Academy of Management Review, 21(4), 1143–1191. https://doi.org/10.2307/259167

- Kessler, E. H., & Chakrabarti, A. K. (1999). Speeding up the pace of new product innovations. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 16(3), 231–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5885.1630231

- Kim, J. Y. & Steensma, H. K. (2017). Employee mobility, spin-outs, and knowledge spill-in: How incumbent firms can learn from new ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 38(8), 1626–1645.

- Kuncel, N. R., Hezlett, S. A., & Ones, D. S. (2001). A comprehensive meta-analysis of the predictive validity of the graduate record examinations: Implications for graduate student selection and performance. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 162–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.162

- Lafontaine, F. & Shaw, K. (2016). Serial entrepreneurship: Learning by doing?. Journal of Labor Economics, 34(S2), S217–S254.

- Lazear, E. (2005). Entrepreneurship. Journal of Labor Economics, 23(4), 649–680. https://doi.org/10.1086/491605

- LeDoux, J. (2002). Synaptic self: How our brains become who we are. 1st ed. Penguin Books.

- Leung, A., Foo, M. D., & Chaturvedi, S. (2013). Imprinting effects of founding core teams on HR values in new ventures. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(1), 87–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00532.x

- Levinthal, D. A., & March, J. G. (1993). The myopia of learning. Strategic Management Journal, 14(S2), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250141009

- Li, K., Rollins, J., & Yan, E. (2018). Web of Science use in published research and review papers 1997–2017: A selective, dynamic, cross-domain, content-based analysis. Scientometrics, 115(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2622-5

- Marion, T. J., Eddleston, K. A., Friar, J. H., & Deeds, D. (2015). The evolution of interorganizational relationships in emerging ventures: An ethnographic study within the new product development process. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(1), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.07.003

- Marmer, M., Herrmann, B. L., Dogrultan, E., Berman, R., Eesley, C., & Blank, S. (2011). Startup genome report extra: Premature scaling, Startup Genome.

- Martínez-Cañas, R., Ruiz-Palomino, P., Jiménez-Moreno, J. J., & Linuesa-Langreo, J. (2023). Push versus pull motivations in entrepreneurial intention: The mediating effect of perceived risk and opportunity recognition. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 29(2), 100214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2023.100214

- Martin, S. L. & Javalgi, R. G. (2016). Entrepreneurial orientation, marketing capabilities and performance: The moderating role of competitive intensity on Latin American international new ventures. Journal of Business Research, 69(6), 2040–2051.

- Marvel, R., Davis, L., & Sproul, R. (2014). Human capital and entrepreneurship research: A critical review and future directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(3), 599–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12136

- Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. R. (2004). Emotional intelligence: Theory, findings, and implications. Psychological Inquiry, 15(3), 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1503_02

- McKelvie, A., Haynie, J. M., & Gustavsson, V. (2011). Unpacking the uncertainty construct: Implications for entrepreneurial action. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(3), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.10.004

- McMullen, J. S., & Shepherd, D. A. (2006). Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 132–152. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159189

- Minniti, M., & Bygrave, W. B. (2001). A dynamic model of entrepreneurial learning. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 25(3), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/10422587010250030

- Mishra, C. S., & Zachary, R. K. (2015). The theory of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 5(4), 251–268. https://doi.org/10.1515/erj-2015-0042

- Moorman, C. & Slotegraaf, R. J. (1999). The contingency value of complementary capabilities in product development. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(2), 239–257.

- Morris, R. (2011), High-impact entrepreneurship global report, Center for High-Impact Entrepreneurship at Endeavor and Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM),

- Mosey, S., & Wright, M. (2007). From Human Capital to Social Capital: A Longitudinal Study of Technology–Based Academic Entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(6), 909–935. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00203.x

- Mudzakkir, M. F., Sukoco, B. M., & Suwignjo, P. (2022). World-class universities: Past and future. International Journal of Educational Management, 36(3), 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-07-2021-0290

- Muñoz-Bullón, F., & Cueto, B. (2011). The sustainability of start-up firms among formerly wage-employed workers. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 29(1), 78–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242610369856

- Neely, B. H., Lovelace, J., Cowen, A. P. & Hiller, N. J. (2020). Metacritiques of upper echelons theory: Verdicts and recommendations for future research. Journal of Management, 46(6), 014920632090864.

- Nelson, T. (2003). The persistence of founder influence: Management, ownership, and performance effects at initial public offering. Strategic Management Journal, 24(8), 707–724. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.328

- Parker, S. (2014). Who become serial and portfolio entrepreneurs?. Small Business Economics, 43(4), 887–898.

- Park, J. E., Pulcrano, J., Leleux, B., & Wright, L. T. (2020). Impact of venture competitions on entrepreneurial network development. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1826090. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1826090

- Parry, M. E., Song, M., Weerd-Nederhof, P. C., & Visscher, K. (2009). The impact of NPD strategy, product strategy, and NPD process on perceived cycle time. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 26(6), 627–639. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2009.00688.x

- Prokopenko, O. & Kornatowski, R. (2018). Features of modern strategic market-oriented activity of enterprises. Marketing & Management of Innovations, 1, 295–303.

- Rahimli, A. (2012). Knowledge management and competitive management. Information and Knowledge Management, 2(7), 37–43.

- Rauch, A., & Frese, M. (2007). Let’s put the person back into entrepreneurship research: A meta-analysis on the relationship between business owners’ personality traits, business creation, and success. European Journal of Work Organization Psychology, 16(4), 353–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320701595438

- Reid, R. D., & Sanders, N. R. (2019). Operations Management: An integrated approach (7th ed.). John Wiley and Son International.

- Ries, E. (2011). The lean startup: How Today’s entrepreneurs use continuous Innovation to create radically successful businesses. Crown Currency.

- Ruiz-Palomino, P., Gutiérrez-Broncano, S., Jiménez-Estévez, P., & Hernandez-Perlines, F. (2021). CEO servant leadership and strategic service differentiation: The role of high-performance work systems and innovativeness. Tourism Management Perspectives, 40(10), 100891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100891

- Ruiz Palomino, P., Kelly, L., & Langreo, J. L. (2019). Towards new more social and human business models: The role of women in social and economy of communion entrepreneurship processes. REVISTA EMPRESA Y HUMANISMO, 22(2), 87–122. https://doi.org/10.15581/015.XXII.2.87-122

- Ruiz-Palomino, P., & Martínez-Cañas, R. (2021). From opportunity recognition to the start-up phase: The moderating role of family and friends-based entrepreneurial social networks. International Entrepreneurship & Management Journal, 17(3), 1159–1182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00734-2

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-Determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital Credit, interest and the Business cycle. Harvard University Press.

- Shane, S. (2000). Prior knowledge and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities. Organization Science, 11(4), 448–469. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.11.4.448.14602

- Shane, S., Locke, E. A., & Collins, C. J. (2003). Entrepreneurial motivation. Human Resource Management Review, 13(2), 257–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(03)00017-2

- Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-48543-8_8

- Shepherd, D. A., Souitaris, V., & Gruber, M. (2020). Creating new ventures: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 47(1), 11–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206319900537

- Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104(2), 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

- Song, L. Z., DiBenedetto, C., & Song, M. (2010). Competitive advantages in the first product of new ventures. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 57(1), 88–102. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2009.2013836

- Staniewski, M. W. (2016). The contribution of business experience and knowledge to successful entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 5147–5152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.095

- Stinchcombe, A. L. (1965). Social structure and organizations. In J. G. March (Ed.), Handbook of organizations (pp. 142–193). Rand McNally.

- Supriharyanti, E., & Sukoco, B. M. (2023). Organizational change capability: A systematic review and future research directions. Management Research Review, 46(1), 46–81. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-01-2021-0039

- Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–1350. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.640

- Thompson, R. A., Connell, J. P., & Bridges, L. J. (1988). Temperament, emotion, and social interactive behavior in the strange situation: A component process analysis of attachment system functioning. Child Development, 59(4), 1102–1110. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130277

- Torraco, R. J. (2005). Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Human Resource Development Review, 4(3), 356–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484305278283

- Townsend, D. M., Busenitz, L. W., & Arthurs, J. D. (2010). To start or not to start: Outcome and ability expectations in the decision to start a new venture. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 192–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.05.003

- Van Praag, C. M. (2005). Successful entrepreneurship: Confronting economic theory with empirical evidence. Edward Elgar.

- Voudouris, I., Deligianni, I., & Lioukas, S. (2017). Labor flexibility and innovation in new ventures. Industrial and Corporate Change, 26(5), 931–951. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtv019

- Wales, W., Patel, P. C., Parida, V., & Kreiser, P. M. (2013). Nonlinear effects of entrepreneurial orientation on small firm performance: The moderating role of resource orchestration capabilities. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 7(2), 93–121. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1153

- Wartiovaara, M., Lahti, T., & Wincent, J. (2019). The role of inspiration in entrepreneurship: Theory and the future research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 101(3), 548–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.035

- Wasserman, N. (2012). The founder’s dilemmas: Anticipating and avoiding the pitfalls that can sink a startup. Princeton University Press.

- Wiklund, J. & Shepherd, D. (2005). Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: A configurational approach. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(1), 71–91.

- Wohlin, C. (2014). Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. EASE ’14: Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, Karlskrona, Sweden (Vol. 38, pp. 1–10).

- Zheng, Y. (2012). Unlocking founding team prior shared experience: A transactive memory system perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(5), 577–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.11.001