Abstract

The role of new luxury fashion brand experience and authenticity on brand equity has not been sufficiently explored empirically. The current study offers a model of the relationship between brand experience, brand authenticity, and brand equity, considering the rising relevance of new luxury fashion brand authenticity and its advantages for practitioners. We used a self-administrative questionnaire, and the number of participants was 411 customers of new luxury fashion brands. Partial-least squares structural equation modeling (SmartPLS software, version 4) is used to evaluate the proposed model. The findings indicate that, with the exception of affective experience, all brand experience dimensions have a direct and indirect impact on brand equity dimensions, considering that brand authenticity is a fully mediating factor. The research results provide valuable advice to help brand managers engage more in practices that enhance brand equity by building memorable and pleasant brand experiences, leading to improved brand authenticity.

1. Introduction

Globalization in developing countries leads to a growing interest among customers to buy luxury brands to enhance their social self-image (Handa & Khare, Citation2013). Therefore, global brands are now more accessible, alluring, and frequently well-known in emerging markets (Safeer et al., Citation2022). Due to the luxury fashion market’s rapid expansion, academics and industry experts in marketing have long been interested in the luxury fashion industry (Talaat, Citation2022; Zollo et al., Citation2020). Luxury fashion market revenue was expected to reach USD 97.23 billion in 2022, with a 5.62 percent increase projected for 2022 to 2027 (Statista, Citation2022b). According to these expectations and the stimulative effects of COVID-19 on the luxury fashion industry compared with 2019 levels, a 15–20 percent increase in the global market was predicted for 2022 (Statista, Citation2022a).

Brand equity has attracted both academic and practical interest over the last three decades (Yoo & Donthu, Citation2001), and it has gained a lot of attention in the luxury industry (Husain et al., Citation2022; Siddiqui, Citation2022). Siddiqui (Citation2022) demonstrated that it is important for luxury firms to increase brand equity in addition to revenue. Ren et al. (Citation2023) mentioned that the objective concept of brand equity is based mainly on to what extent businesses can retain effective marketing outcomes. In this regard, brands with high equity are rewarded with advantages like committed customers and the ability to set higher prices (Siu et al., Citation2016). Considering that brand equity affects long-term sales and profitability, building strong brand equity has long been considered essential to building successful brands (Sharma, Citation2016). Several studies have investigated brand equity, but their results in developed countries (Iglesias et al., Citation2019; Rodríguez-López et al., Citation2020; Siu et al., Citation2016) might not apply to developing countries due to cultural differences. Consequently, both academics and managers should possess a deeper knowledge of brand equity and how it affects business (Siu et al., Citation2016).

In the last decades, brand experience has emerged as an essential marketing concept that seeks to create distinctive, enjoyable, and memorable experiences (Amoroso et al., Citation2021). In turn, academics have stated that gaining experience should be a top priority for any company (Brakus et al., Citation2009; Pine & Gilmore, Citation1998). In fact, the secret to capturing customers’ hearts and minds is to deliver a compellingly positive experience (Pine & Gilmore, Citation1998). Particularly today, brand experience has emerged as the most important way to distinguish among companies offering increasingly similar goods and services with few noticeable functional differences, with customer decisions increasingly influenced by emotional factors rather than logical considerations. Therefore, brands should incorporate a wide range of experiences in conjunction with a collection of qualities (Pina & Dias, Citation2021).

Authenticity is a fundamental human ambition in these times of increased uncertainty, which makes it a key issue in modern marketing and a major element of marketing success. To reduce this uncertainty, customers seek authenticity in many aspects of their daily lives, including the products they purchase and businesses they support (Bruhn et al., Citation2012). Moreover, brand authenticity is gaining attention in the literature since it might help firms maintain their competitiveness (Akbar & Wymer, Citation2017). In turn, academics proposed that brand authenticity is highly valued by customers and important for marketers’ success (Murshed et al., Citation2023). Subsequently, authenticity is considered one of the most pressing concerns confronting the luxury market today (Hitzler & Müller-Stewens, Citation2017). According to Napoli et al. (Citation2014), for companies to have authentic brands, they must act honestly and be dedicated to offering superior quality and long-lasting services and products that reflect their company histories. But while doing all these things, they should not stray from the core brand qualities associated with them from the beginning.

In the past decade, the democratisation of luxury brands has been facilitated by improvements in production techniques. This democratisation of luxury brands is known as new luxury brands (Ajitha & Sivakumar, Citation2019). Silverstein and Fiske (Citation2003) defined new luxury brands as “goods and services with premium attributes at an affordable price. Like traditional luxury brands, new luxury brands are authentic, exclusive, pride, and sophisticated” (Kim et al., Citation2019). In comparison to traditional luxury goods, which have well-contained exclusivity in terms of both accessibility and price, these new offers are frequently mass-marketed and affordable at premium prices (Truong et al., Citation2009).

Egypt is regarded as a potentially profitable market for global luxury brands owing to its recent steady growth and anticipated future expansion. According to Appiah-Nimo et al. (Citation2023), the leading markets for luxury brands in Africa include South Africa, Egypt, Morocco, Mauritius, and Nigeria. To successfully penetrate the market, international marketers must fully understand it (El Din & El Sahn, Citation2013). According to the Kearney Global Retail Development Index (GRDI), which covers emerging retail markets, Egypt is ranked seventh (up 19 positions). The retail industry in Egypt was anticipated to reach USD 200 billion in 2020. It is also predicted to increase by 5% annually between 2020 and 2025 to reach about USD 254 billion. Thus, from 2020 to 2025, fashion shops are predicted to see sales increase at a rate of 5.7% per year (Business today Egypt, Citation2021). Moreover, revenue in the luxury fashion industry in Egypt amounts USD 193 million in 2023. The market is anticipated to increase by 3.12% annually between 2023 and 2028 (Statista, Citation2023).

The primary objective of the current study is to investigate the effect of brand experience and brand authenticity on brand equity. Specifically, we focus on the brand experience’s direct and indirect effects on brand equity through brand authenticity. Our results can help new luxury fashion managers and providers understand the role of brand experience in enhancing brand authenticity and brand equity. In addition, the results may also help policymakers develop strategies to guide the new luxury fashion market in Egypt.

This study offers numerous contributions to the literature. The main contribution of the current study is to advance the existing knowledge by understanding how customers evaluate brand equity based on experiential marketing strategies and brand authenticity. Fritz et al. (Citation2017) proposed that there is limited empirical research examining the antecedents of brand authenticity as the vast majority of prior studies have been qualitative. In addition, previous studies have focused mostly on analyzing the impact of brand experience on brand authenticity in limited contexts such as the American luxury hotel context (Manthiou et al., Citation2018), in various manufacturing, retail, and service industries in China (Safeer et al., Citation2021), and for different global brands such as McDonald’s, Nike, and Apple (Tran & Nguyen, Citation2022). Therefore, this study offers empirical evidence that can be used to understand the causes of brand authenticity and how it relates to new luxury fashion brands.

Furthermore, most previous studies have indicated a positive effect of brand authenticity on some elements of brand equity, such as brand loyalty (Choi et al., Citation2015; Uysal & Okumuş, Citation2022) and perceived quality (Lu et al., Citation2015). Previous studies Rodríguez-López et al. (Citation2020); Tran et al. (Citation2021) concentrated on brand equity as a second-order component without considering how brand authenticity influences the various dimensions of brand equity. So, this study enriches the body of knowledge related to the consequences of brand authenticity by examining brand equity as a first-order factor in the context of new luxury fashion brands. Although there has been a lot of research on luxury fashion brands, there hasn’t been much research done on new luxury fashion brands (Kim et al., Citation2019). Consequently, this study focused on the following objectives, especially in the context of new luxury fashion brands:

To determine the importance of the brand experience and its outcomes (e.g., brand authenticity and brand equity) and linkages, specifically for new luxury fashion brands.

To understand how customers evaluate brand equity based on experiential marketing strategies and brand authenticity.

To ascertain the mediation role of brand authenticity in the relationship between brand experience and brand equity.

In order to fill the aforementioned research gap, this study analyses the effect of brand experience and brand authenticity on brand equity. The remainder of the research is organized as follows: We review the literature in Section 2. Section 3 investigates the mediating role of brand authenticity and links brand experience to brand equity. Section 4 covers the research methodology, and Section 5 displays our research findings. In Section 6, we present a discussion, conclusions, implications, and recommendations for future research studies.

2. Literature review

2.1. Brand experience

Since the concept of “brand experience” first appeared by Holbrook and Hirschman (Citation1982), the concept has become one of the most essential marketing terms in both theory and practice (Amoroso et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, Akoglu and Özbek (Citation2021) suggested that outstanding brands should develop strong relationships with their customers to keep them from switching to rival brands. In this regard, the initial step in creating these relationships is the brand experience. Brand experience is defined as “subjective, internal consumer responses (sensations, feelings, and cognitions) as well as behavioral responses evoked by brand-related stimuli that are part of a brand’s design and identity, packaging, communications, and environments” (Brakus et al., Citation2009, p. 53).

Prior literature (Carrizo Moreira et al., Citation2017; Iglesias et al., Citation2019; Khan et al., Citation2021; Park et al., Citation2023; Pina & Dias, Citation2021) proposed that brand experience involves four dimensions: sensory, affective, intellectual, and behavioral. Based on reviewing the previous studies, we contend there is an argument for operationalizing the four dimensions of brand experience proposed by Brakus et al. (Citation2009).The sensory dimension refers to customers’ perceived pleasure and excitement when they hear, taste, smell, see, and touch a brand (Khan et al., Citation2021); the affective component involves sentiments, emotions formed by the brands, and feelings and connections with brands that provoke a customer’s response (Brakus et al., Citation2009; Carrizo Moreira et al., Citation2017; Pina & Dias, Citation2021); and the intellectual dimension entails the innovative problem-solving thinking that a brand promotes through its goods and services (Khan et al., Citation2016). Finally, the behavioral component describes the physical behaviors, lifestyles, and physiological experiences that the brand stimulates (Brakus et al., Citation2009; Carrizo Moreira et al., Citation2017; Pina & Dias, Citation2021).

2.2. Brand authenticity

Nowadays, authenticity is one of the key aspects of goods or services that most customers are interested in (Tran & Nguyen, Citation2022). The word “authenticity” is thought to have its theoretical origins in the Greek word “authentiko,” which means “main, original” (Akbar & Wymer, Citation2017; Govarchin, Citation2019; Hernandez-Fernandez & Lewis, Citation2019). Nevertheless, few consumers and brand marketers can properly define what authenticity in branding means (Tran & Nguyen, Citation2022). In this regard, prior studies (Akbar & Wymer, Citation2017; Dwivedi & McDonald, Citation2018; Park et al., Citation2023) have attempted to identify brand authenticity as the extent to which a brand is regarded as unique and genuine, meaning it is distinct from competitors and truthful to itself. Authentic brands frequently set themselves apart from imitations by being consistent, reliable, original, and natural (Bruhn et al., Citation2012). A high degree of brand authenticity makes customers feel that they are members of a social or geographical community (Bertoli et al., Citation2016).

Previous studies (Fritz et al., Citation2017; Oh et al., Citation2019; Papadopoulou et al., Citation2023) suggested that brand authenticity involves four dimensions (naturalness, reliability, originality, and continuity). Based on reviewing the prior studies, the current study argues that there is justification for operationalizing the four aspects of brand authenticity described by Bruhn et al. (Citation2012). The continuity dimension is the ability of a brand to survive trends, be historically significant, and have timelessness (Papadopoulou et al., Citation2023). It also relates to a brand’s dependability, longevity, and consistency. (Bruhn et al., Citation2012). The brand’s ability to stand out from all other brands and its novel offerings to the market are both determined by the originality dimension (Akbar & Wymer, Citation2017; Bruhn et al., Citation2012). The reliability dimension concerns a brand’s adherence to its standards and credibility and its ability to keep its word (Bruhn et al., Citation2012; Oh et al., Citation2019). The naturalness dimension, which also relates to the sense of a brand’s sincerity, realness, and lack of artificiality, measures how effectively a brand stays grounded in its defined brand values (Bruhn et al., Citation2012; Napoli et al., Citation2014).

2.3. Brand equity

Once the concept of “brand equity” first emerged in the late 1990s, the concept has become one of the most significant marketing terms in both theory and real-world applications (Srinivasan et al., Citation2005). Previous studies by Emari and Emari (Citation2012) and Soenyoto (Citation2015) have defined brand equity by depending on two approaches: i) the firm’s perspective, which concentrates on financial value as a gauge of a company’s performance; and ii) the consumer’s perspective, which depends on the relationship between brands and customers.

The frameworks of Aaker (Citation1991) and Keller (Citation1993) have been acknowledged as two basic constituents of brand equity. First, Aaker (Citation1991) describes brand equity as “a set of brand assets and liabilities linked to a brand, its name, and symbol, which add to or subtract from the value provided by a product or service to a firm and/or to that firm’s customers” (p. 15). Aaker (Citation1991) posits five components of brand equity: brand awareness, brand loyalty, perceived quality, brand associations,, and other proprietary brand assets. The last dimension (other proprietary brand assets) is typically disregarded in marketing studies since it has little effect on how customers perceive a brand (Yoo & Donthu, Citation2001). On the other side, Keller (Citation1993) conceptualized brand equity as “the differential effect of brand knowledge on consumer response to the marketing of the brand” (p. 2).

This research adopts the four aspects of Aaker (Citation1991) (brand awareness, brand associations, perceived quality, and brand loyalty), which were most frequently employed in earlier literature (Emari & Emari, Citation2012; Ertemel & Civelek, Citation2020; Soenyoto, Citation2015). Brand awareness is “the ability for a potential buyer to recognize or recall that a brand is a member of a certain product category” (Aaker, Citation1991, p. 61). Brand associations are anything that a customer remembers in relation to a brand (Aaker, Citation1991; Keller, Citation1993). According to Chen-Yu et al. (Citation2016), it is essential to understand how a customer’s ideas are connected to a brand in order to inspire the reactions desired from them toward that brand. The consumer’s view of a product’s or service’s overall quality or superiority over rivals in relation to its intended use is known as perceived quality (Aaker, Citation1991). Brand loyalty is defined as the degree of consumers’ commitment to a brand as evidenced by their desire to buy the brand as a preferred choice. When customers are loyal to a brand, it is simpler and less expensive to keep them as customers (Ertemel & Civelek, Citation2020).

3. Development of hypotheses

3.1. Brand experience and brand authenticity

The relationship between brand experience and brand authenticity can be described using Heider’s (Citation1958) attribution theory, which argues that a person’s beliefs about the reasons for their past actions impact their future behavior and response. Human experience allows us to differentiate between internal and external causes, which aids in understanding inferences and predicting experiential events. The idea of attribution holds that outside factors, such as authentic features, are what ultimately contribute to consumers’ affective, sensory, behavioral, and intellectual brand experiences. Similarly, customers believe that when a company fulfills its promises, it is an authentic brand (Raza et al., Citation2021; Safeer et al., Citation2021). Therefore, brand experience dimensions and brand authenticity are crucial in today’s competitive market for developing consumer-brand interactions and motivating positive behavior (Park et al., Citation2023). According to Safeer et al. (Citation2021), the four elements of the brand experience have a favorable effect on brand authenticity.

Within the same context, Raza et al. (Citation2021) confirmed that brand experience has a positive impact on brand authenticity. These results are consistent with the work of Tran and Nguyen (Citation2022), who also found a significant positive relationship between brand experience and brand authenticity. Furthermore, Park et al. (Citation2023) demonstrated that all brand experience dimensions have a positive effect on brand authenticity, except the behavioral dimension. In addition, Murshed et al. (Citation2023) showed that brand experiences positively affect brand authenticity. Gilmore and Pine (Citation2007) and Manthiou et al. (Citation2018) asserted that improved brand performance results in consumers having pleasant brand experiences, which improves the brand’s perceived authenticity. Additionally, brand authenticity is a crucial consequence of brand experience that drives the brand toward success, provides significant consistency across brand experience dimensions, and helps brands become more authentic (Robbins et al., Citation2009; Tran et al., Citation2020). Accordingly, this study puts forth the following hypotheses:

H1

Brand experience has a positive impact on brand authenticity.

H1a

Sensory brand experience has a positive impact on brand authenticity.

H1b

Affective brand experience has a positive impact on brand authenticity.

H1c

Intellectual brand experience has a positive impact on brand authenticity.

H1d

Behavioral brand experience has a positive impact on brand authenticity.

3.2. Brand authenticity and brand equity

The stimulus—organism–response (SOR) model of Mehrabian and Russell (Citation1974) can be used to explain how authenticity affects brand equity. According to this model, environmental cues from the outside environment cause emotional reactions that then influence behavior. From this viewpoint, a brand’s authenticity serves as a significant stimulant that can cause a brand equity response (Rodríguez-López et al., Citation2020). On this subject, several researchers, including Tran et al. (Citation2020) and Rodríguez-López et al. (Citation2020), indicate that brand authenticity has a positive impact on brand equity.

Additionally, Lu et al. (Citation2015) revealed that brand authenticity and all components of brand equity (brand awareness, brand association, perceived quality, and brand loyalty) are positively and significantly related. In addition, Chen et al. (Citation2021) demonstrated that highly authentic brands have superior quality, greater consumer awareness, and are simpler to purchase, leading to improved brand equity. Based on the above-mentioned discussions, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2

Brand authenticity has a positive impact on brand equity.

H2a

Brand authenticity has a positive impact on brand awareness.

H2b

Brand authenticity has a positive impact on brand association.

H2c

Brand authenticity has a positive impact on perceived quality.

H2d

Brand authenticity has a positive impact on brand loyalty.

3.3. Brand experience and brand equity

Numerous studies support the concept that brand experience positively influences brand equity. According to Carrizo Moreira et al. (Citation2017); Zollo et al. (Citation2020) confirmed that brand experience has a substantial effect on brand equity components (brand awareness, associations, perceptions of quality, and loyalty). Moreover, Altaf et al. (Citation2017) concluded that brand experience is the most important area of focus when managing brand equity. Also, Shahzad et al. (Citation2019) showed that brand experiences can have an impact on brand equity in a variety of contexts. Additionally, Jeon and Yoo (Citation2021) asserted that sensory, affective, intellectual, and behaviorally experienced customers frequently recognize a brand quickly, have a strong association with it, and, through their experience, they generally evaluate quality more favorably. Furthermore, Ren et al. (Citation2023) demonstrated that customer experience has a positive and significant impact on brand equity. In addition, Sohaib et al. (Citation2022) addressed that the dimensions of brand experience positively affect brand equity. Nevertheless, Pina and Dias (Citation2021) concluded that all brand equity dimensions are more influenced by sensory and affective experiences. In light of the preceding discussions, the following hypothesis is developed:

H3

Brand experience has a positive impact on brand equity.

3.4. Brand authenticity as a mediator

An authentic brand should keep its promises to gain customer trust and evoke favorable feelings (Fritz et al., Citation2017). According to attribution theory, external factors like authentic features lead to favorable outcomes for customers’ sensory, affective, intellectual, and behavioral brand experiences. Safeer et al. (Citation2021) found that brand authenticity was one of the most significant consequences of the brand experience that positively impacted customer feelings.

According to the SOR theory of Mehrabian and Russell (Citation1974), when a consumer is exposed to external stimuli, they interpret them first by developing an emotional response, and then a behavior follows (Rodríguez-López et al., Citation2020). In this study, brand equity can be thought of as a marketing outcome, while brand experience can be understood as a stimulus. Previous studies have demonstrated that customer perception serves as a mediator between marketing stimulus and marketing outcomes (Shang et al., Citation2020). When modeled within the SOR paradigm, brand experience is a marketing stimulus (stimuli), brand authenticity reflects customer perceptions (organisms), and brand equity leads to behavioral responses (responses). To explore how brand authenticity mediates the relationship between brand experience and brand authenticity, we propose the following hypotheses:

H4

Brand authenticity mediates the relationship between sensory brand experience and brand awareness (H4a), brand associations (H4b), perceived quality (H4c), and brand loyalty (H4d).

H5

Brand authenticity mediates the relationship between affective brand experience and brand awareness (H5a), brand associations (H5b), perceived quality (H5c), and brand loyalty (H5d).

H6

Brand authenticity mediates the relationship between intellectual brand experience and brand awareness (H6a), brand associations (H6b), perceived quality (H6c), and brand loyalty (H6d).

H7

Brand authenticity mediates the relationship between behavioral brand experience and brand awareness (H7a), brand associations (H7b), perceived quality (H7c), and brand loyalty (H7d).

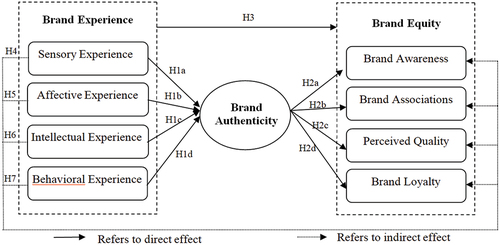

Figure depicts our study model, which is based on this review and the proposed direct and indirect relations between brand experiences and brand equity.

4. Methodology

4.1. Sample and procedure

This research is applied to new luxury brands in a developing country like Egypt for the following reasons: 1) New luxury brands are apparent in developing countries because of the extreme income inequality (Kumar et al., Citation2009), 2) New luxury brands have been developed to make luxury brands affordable for middle-class customers (Kim et al., Citation2019), 3) luxury purchasing in developing countries must meet the need of consumers to portray a western lifestyle and offer both emotional and practical benefits (Eng & Bogaert, Citation2010), 4) In developing countries, luxury consumption has focused mainly on customers buying luxury brands to enhance their social position (Husain et al., Citation2022), and 5) The findings of research conducted in developed countries might not be applicable to developing countries, as there is limited attention to analyse new luxury brand consumption behaviour and attitude in developing countries (Ajitha & Sivakumar, Citation2019; Truong et al., Citation2009).

In addition, this study applied to fashion brands, as fashion is the second-largest sector of the luxury market after luxury automobiles and personal luxury items. The personal luxury products sector, including luxury clothes, watches, jewellery, and eyewear, has climbed steadily in past decades (Statista, Citation2022b). Generally speaking, there are many different types of luxury products. They include items such as soft luxury (clothing and accessories) and hard luxury (watches and jewellery), as well as items like alcohol, food, travel, hotels, technology, and automobiles (Kim, Citation2019). The current study concentrates on soft luxury, particularly luxury fashion company goods such as clothing, shoes, and handbags (Kim, Citation2019). This may be due to Fionda and Moore’s (Citation2009) claim that the majority of luxury brands are luxury fashion brands. Furthermore, academics have been more interested in consumer research related to fashion brands.

In determining the sample size, we depend on Cochran’s formula for an infinite population. The formula is SS = [Z2p (1 − p)]/C2 (Godden, Citation2004). The confidence level is 95 percent (z value: 1.96), the confidence intervals (C) are 0.05, and the population percentage (p) is 0.5. To have a 95% confidence level, the real values should be within ±5% of the surveyed values; thus, 385 surveys are sufficient. This study employed a non-probabilistic sample, in which the respondents were selected using a convenience sampling approach that evolved into snowball sampling because it is often hard to inquire into the entire population by considering accessibility and resource restrictions (Etikan, Citation2016).

The data was gathered via a Google Forms-based online questionnaire. We posted the questionnaire’s link in luxury brand groups on Facebook. During April and July 2022, we received 415 surveys. Considering the study’s objectives, a filter question was included to screen out ineligible people because it was essential for participants to have already purchased new luxury brands in the last six months. The questionnaire began with a list of new luxury brands (Appendix). In this regard, we relied on reports and prior studies that helped the researchers determine the new luxury brand list (Appendix) (Ajitha & Sivakumar, Citation2019; Segura, Citation2019). Therefore, 411 of the 415 surveys had valid responses, which were regarded as adequate for our analysis. The sample profile is shown in Table . In addition, we used the Harman single-factor test. The results demonstrated that a single factor interpreted 42% of the total variance, which falls within the acceptable range (less than 50%) (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012). Thus, there is no common methodological bias.

Table 1. Sample characteristics

Table displays the demographic breakdown of the 411 respondents. Regarding gender, 302 (73.5%) were female, whereas 109 (26.5%) were male. This ratio is consistent with Handa and Khare (Citation2013) and Stokburger-Sauer and Teichmann (Citation2013), which showed that females have a greater attitude towards purchasing luxury brands than males. This is agreed with Talaat (Citation2022), who noted that the Egyptian young women (64.8%) have higher levels of fashion clothing purchases than men (35.2%). In addition, Abrar et al. (Citation2020) indicated that women are prominent players in the fashion clothing industry. (86.6%) of the sample’s participants were in the age range of 18 to 39 years old, 40–49 (8.5%), and 50 or above (4.9%). This is consistent with Handa and Khare (Citation2013), who mentioned that young women have higher levels of luxury fashion brand purchases. In this regard, Abrar et al. (Citation2020) addressed that the fashion industry is shaped by young women. Infomineo (Citation2014) stated that the Egyptian economy is being driven by the young people, who are educated, tolerant, technologically astute, and constantly exposed to social media. Concerning education level, nearly two-thirds of the sample (66.2%) holds at least a bachelor’s degree, followed by a master’s degree or doctorate (32.3%) and an undergraduate (1.5%). Regarding income, nearly most of the sample (96.6%) had an income of greater than 5,000 per month, and only (3.4%) had an income of greater than 1200 and less than 5000 per month. This ratio is matched with the Average Salary report in Egypt indicated that the average salary per month for a person is 9230 EGP (Salary explorer, Citation2023). In addition, this is agreed upon with the new luxury brand definition of Silverstein and Fiske (Citation2003), which defines it as “products and services that possess higher levels of quality and taste but are not so expensive as to be out of reach”. Furthermore, Truong et al. (Citation2009) stated that these new offers are frequently mass-marketed and affordable at premium prices.

4.2. Questionnaire and measures

There are two main parts of the questionnaire. The scale items for brand experience, brand authenticity, and brand equity are included in the first part. To evaluate the construct items, we employed a 5-point Likert scale, from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Demographic profiles such as gender, age, education, and income are included in the second part.

4.2.1. Brand experience (BEX)

We measured brand experience by using a multidimensional 12-item scale, which was developed by Brakus et al. (Citation2009). The scale has four components: sensory, affective, intellectual, and behavioral. This scale was adopted in many studies (e.g., Akoglu & Özbek, Citation2021; Altaf et al., Citation2017; Pina & Dias, Citation2021; Safeer et al., Citation2021).

4.2.2. For measuring brand authenticity (BA)

This study used a multidimensional 15-item scale developed by Bruhn et al. (Citation2012). This scale has four components: continuity, originality, reliability, and naturalness. As recommended by Little et al. (Citation2002), we reduced the number of parameters in our model by averaging the values of the second-order factors of the multidimensional constructs of brand authenticity. This scale was applied in prior studies (e.g., Oh et al., Citation2019; Rodrigues et al., Citation2021).

4.2.3. Brand equity (BEQ)

The brand equity measure was compiled from prior literature (e.g., Aaker (Citation1991, Citation1996); Lassar et al. (Citation1995); Netemeyer et al. (Citation2004); Yoo et al. (Citation2000)). Brand equity has four components: brand awareness, brand associations, perceived quality, and brand loyalty. We measured brand awareness using the Aaker (Citation1996) scale, which involves five items. Brand associations consist of eight items adopted from Aaker (Citation1996); Lassar et al. (Citation1995) and Netemeyer et al. (Citation2004). Perceived quality was measured using Aaker (Citation1991), and it includes four items. Finally, brand loyalty was evaluated by adopting Yoo et al. (Citation2000), and it consists of three items. In the current study, we adopted a measure for brand equity from different scales to understand the concept comprehensively from a customer’s perspective.

5. Results

We applied structural equation modeling (SEM). SEM is a useful and widely used statistical analytic technique (Hair et al., Citation2012). The proposed model (Figure ) was assessed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (SmartPLS software v. 4). We used SmartPLS for the following reasons: (1) it minimizes the residual variances of dependent variables; (2) it is helpful in evaluating complex research models that contain a large number of variables; (3) it aids in understanding the relationship between causes and prediction, especially in marketing research, and (4) it helps in avoiding the problems related to collinearity and normal distribution, compared with covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM) (Hair et al., Citation2019). For the statistical analysis, we used a two-step procedure. The first step is related to evaluating the validity and reliability of the measurement model. The second step is related to the evaluation of the structural model (Hair et al., Citation2019).

5.1. Measurement model evaluation (MME)

In MME, we assessed internal consistency reliability (ICR), convergent validity (CV), and discriminant validity (DV). According to the suggestion of Chin (Citation1998), we accepted all factor loadings that were above 0.60. During the preliminary model evaluation, it was verified that the factor loadings of all items were larger than 0.60 (Table ). Through calculating Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability, we evaluated construct reliability. The findings demonstrated that all constructs had scores greater than 0.70, which indicates that all constructs were internally consistent (Henseler et al., Citation2009) (Table ). Then, we evaluated the convergent validity as the values of the average variance extracted (AVE) of all constructs were more than 0.5, which supports that all constructs were convergently valid (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981), as shown in Table .

Table 2. Convergent validity and internal consistency reliability

In order to measure discriminant validity, we made sure that the AVE for each reflective construct was greater than its correlations with other constructs, which are shown in Table . All the constructs met the standards set out by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981). Overall, as indicated in Tables , the measurement model has achieved internal consistency, reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity.

Table 3. Correlation coefficients

5.2. Structural model evaluation

Hair et al. (Citation2011) outline four main steps for conducting the structural model evaluation: (1) calculate multicollinearity; (2) evaluate the coefficient of determination (R2 values); (3) determine the path coefficients’ significance; and (4) evaluate the predictive relevance (Q2 values).

First, we used the variance inflation factor (VIF) to ensure that there was no multicollinearity problem. All the VIF values ranged between 1.322 and 3.8, which falls within the acceptable range (less than 5) (Hair et al., Citation2011). Second, we tested the coefficient of determination (R2 value) to evaluate the predictive power of the model. Thus, we calculated R2 values for the five endogenous variables of brand authenticity, brand awareness, brand associations, perceived quality, and brand loyalty. They are 48.4%, 25.8%, 57.6%, 36.9%, and 31.1%, respectively, all greater than 10%, so the model has superior predictive power (Falk & Miller, Citation1992). Therefore, R2 was a good predictor for the structural model. Table shows the hypotheses assessed using the path coefficients and p-values. Third, we assess the significance of path coefficients using the bootstrapping approach at a significance level of 5% and 5000 subsamples (Chin, Citation1998; Hair et al., Citation2012). Finally, besides R2, we used Q2 to assess the structural model’s predictive validity. The Q2 values of the endogenous variables are larger than zero (brand authenticity: 0.988; brand awareness: 0.982; brand associations: 0.983; perceived quality: 0.978; and brand loyalty: 0.975), which shows that the exogenous constructs are predictive of the endogenous construct.

Table 4. Hypotheses testing results of direct effects

To assess the structural model’s fitness, we calculated the square root mean residual value, which we found to be 0.064, with the requirement that the accepted value should be less than 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999), which means that the model had a good fit. Additionally, we calculated the value of goodness-of-fit (GoF) using the Wetzels et al. (Citation2009) equation. In the current research, we relied on the values of R2 and AVE. The results showed that the GoF value was 0.528, which is higher than the standard value of 0.26. So, the model had a good fit.

5.3. Testing of hypotheses

The findings of the bootstrapping approach are shown in Table . The findings indicated that sensory experience has a positive and significant impact on brand authenticity (ß = 0.311, P < 0.05), supporting H1a. Furthermore, intellectual experience positively and significantly affects brand authenticity (ß = 0.188, P < 0.05), so H1c is accepted. Moreover, behavioral experience has a positive and significant influence on brand authenticity (ß = 0.331, P < 0.05), confirming H1d. However, no significant effect of affective brand experience was found on brand authenticity (ß =-0.050, P > 0.05), so H1b was rejected. Thus, H1 is partially supported.

The results showed that brand authenticity influences brand awareness positively and significantly (ß = 0.508, P < 0.05), confirming H2a. Moreover, brand authenticity significantly and positively influences brand associations (ß = 0.759, P < 0.05), hence H2b is accepted. Furthermore, brand authenticity positively and significantly impacts perceived quality (ß = 0.607, P < 0.05), supporting H2c. Additionally, brand authenticity significantly influences brand loyalty directly (ß = 0.557, P < 0.05), so H2d is accepted. Thus, H2 is fully supported. Additionally, we tested the impact of brand experience on brand equity. The results found that brand experience affects brand equity positively and significantly (ß = 0.765, P < 0.05), supporting H3 (Table ).

Table illustrates the findings of the mediation hypotheses. Our results demonstrate that brand authenticity fully mediates the effect of sensory experience on brand equity dimensions (brand awareness (H4a), brand associations (H4b), perceived quality (H4c), and brand loyalty (H4d)). Thus, H4a (ß = 0.158, P < 0.05), H4b (ß = 0.236, P < 0.05), H4c (ß = 0.189, P < 0.05), and H4d (ß = 0.173, P < 0.05) were supported. So, H4 is accepted. Furthermore, brand authenticity has a full mediation role in the relationship between intellectual experience and brand equity dimensions (brand awareness (H6a), brand associations (H6b), perceived quality (H6c), and brand loyalty (H6d)). Consequently, H6a (ß = 0.095, P < 0.05), H6b (ß = 0.142, P < 0.05), H6c (ß = 0.114, P < 0.05), and H6d (ß = 0.105, P < 0.05) were accepted. So, H6 is fully accepted. Moreover, brand authenticity fully mediates the impact of behavioral experience on brand equity dimensions (brand awareness (H7a), brand associations (H7b), perceived quality (H7c), and brand loyalty (H7d)). So, H7a (ß = 0.168, P < 0.05), H7b (ß = 0.251, P < 0.05), H7c (ß = 0.201, P < 0.05), and H7d (ß = 0.185, P < 0.05) were supported. Thus, H7 is fully supported. Nevertheless, brand authenticity did not significantly mediate the relation between affective experience and brand equity dimensions (brand awareness (H5a), brand associations (H5b), perceived quality (H5c), and brand loyalty (H5d)). Thus, H5a (ß = −0.026, P > 0.05), H5b (ß = −0.038, P > 0.05), H5c (ß = −0.031, P > 0.05), and H5d (ß = −0.028, P > 0.05) were rejected. So, H5 is fully rejected (Table ).

Table 5. Indirect effects hypotheses testing results

6. Conclusion, implications, and limitations

6.1. Conclusion

Our findings indicate that sensory, intellectual, and behavioral experiences have a positive effect on brand authenticity. These results support Gilmore and Pine’s (Citation2007) finding, who confirmed that high brand performance generates memorable and pleasant experiences, which in turn strengthens brand authenticity. Additionally, Robbins et al. (Citation2009) and Tran and Nguyen (Citation2022) acknowledged that brand authenticity is a crucial outcome of brand experience; therefore, authentic brands should correspond to how customers perceive the brand promises. Furthermore, Safeer et al. (Citation2021) discovered that brand authenticity is a pivotal consequence of brand experience that has a beneficial impact on customer emotions. However, our study found that affective experience has no impact on brand authenticity. This result contradicts Safeer et al. (Citation2021), who claimed affective brand experience has a positive influence on brand authenticity. This disagreement may be due to the role of culture in formulating authenticity (Slabu et al., Citation2014). Additionally, Kim and Sullivan (Citation2019) mentioned that in a retail context, managers of fashion brands should create new tactics to attract customers by employing an affective brand strategy to inspire customers’ wants, goals, desires, and egos.

Second, we find that brand authenticity has a positive influence on brand equity dimensions. Our findings support the claims made by Chen et al. (Citation2021) and Rodríguez-López et al. (Citation2020) that brand authenticity is an antecedent of brand equity. Third, the current study proposes that brand experience positively impacts brand equity. This result is consistent with those of Altaf et al. (Citation2017) and Jeon and Yoo (Citation2021), who concluded that brand experience is a fundamental determinant of brand equity.

Finally, this study addresses the mediation of sensory, intellectual, and behavioral experience and brand equity dimensions by brand authenticity. However, we find that brand authenticity does not mediate the relationship between affective brand experience and brand equity dimensions. This result is semi- compatible with the results of Pina and Dias (Citation2021), which indicated that an affective brand experience positively affects perceived quality and loyalty, while an affective brand experience does not influence brand awareness and brand associations. Additionally, Zollo et al. (Citation2020) mentioned that hedonic benefits have no effect on brand equity dimensions in the online context, while the offline context may help in satisfying customers’ hedonic benefits. So, this puts more stress on brand managers to design stores (offline environment) and brand websites (online environment) in a way that generates a memorable and unique affective experience.

6.2. Theoretical implications

Our research provides new insights into the existing brand experience, brand authenticity, and brand equity studies by applying the attribution theory to new luxury fashion markets. First, this study improves academic knowledge related to the predecessors of brand authenticity and the application of attribution theory within the Egyptian context. Even though there is a great interest in exploring the antecedents of brand authenticity, there is still a research gap, as most previous studies have been qualitative and descriptive (Fritz et al., Citation2017). Although the topic of customer experience has gained considerable attention, little research has been conducted on how brand experience impacts brand authenticity in limited contexts, such as the American luxury hotel context (Manthiou et al., Citation2018), in different manufacturing, retail, and service industries in China (Safeer et al., Citation2021), and for different global brands such as McDonald’s, Nike, and Apple (Tran & Nguyen, Citation2022). Furthermore, Ajitha and Sivakumar (Citation2019); Truong et al. (Citation2009) addressed that the findings of research conducted in developed countries might not be applicable to developing countries as there is limited emphasis on analysing new luxury brand consumption behaviour and attitude in developing countries. Consequently, the current research provides empirical evidence for understanding the antecedents of brand authenticity and its links to new luxury fashion brands in Egypt.

Second, our research contributes to the body of knowledge on brand equity by following the recommendations of Fritz et al. (Citation2017) to conduct further study on the long-term results of brand authenticity (e.g., brand equity). Prior research has confirmed that brand authenticity is one of the antecedents that influences brand equity within a wide range of industries, such as in heritage destinations in China (Chen et al., Citation2021), for three different brands—Nike, Starbucks, and Apple (Tran et al., Citation2021), and in the hospitality sector (Lu et al., Citation2015; Rodríguez-López et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, numerous studies have indicated a positive impact of brand authenticity on some elements of brand equity. For example, Choi et al. (Citation2015) and Uysal and Okumuş (Citation2022) proposed that brand authenticity positively influences brand loyalty. In the hospitality context, Lu et al. (Citation2015) discovered that brand authenticity positively impacts perceived quality. Moreover, they discovered that brand associations in ethnic restaurants are significantly influenced by customers’ perceptions of a brand’s authenticity. Chen et al. (Citation2021) mentioned that brand authenticity positively impacts brand awareness, perceived quality, and brand loyalty without considering the effect of brand authenticity on brand associations. On the other side, some studies focused on studying brand equity as a second-order factor without considering how brand authenticity affects the different dimensions of brand equity (Rodríguez-López et al., Citation2020; Tran et al., Citation2021). To sum up, we enrich the body of knowledge related to the consequences of brand authenticity by examining brand equity as a first-order factor in the new luxury fashion brands context.

Third, the current research is a response to Pina and Dias’s (Citation2021) call for further empirical research on the relationship between the dimensions of brand experience and the various constructs that make up brand equity. Additionally, we add to the literature on brand equity by illustrating how brand experience increases not only brand loyalty (e.g., Akoglu and Özbek (Citation2021); Hussein (Citation2018); Liu et al. (Citation2021)) but also brand awareness, perceived quality, and brand associations. Furthermore, considerable effort has been made to examine the influence of brand experience on brand equity in different contexts, e.g., Islamic banking in Malaysia and Pakistan (Altaf et al., Citation2017), groceries in South Korea (Jeon & Yoo, Citation2021), and Nespresso products in Portugal (Pina & Dias, Citation2021). In the field of luxury fashion markets, there was limited interest in studying how brand experience affects brand equity, as it was conducted in the USA (Zollo et al., Citation2020). Consequently, this research helps in comprehending how consumers assess brand equity by relying on experiential marketing techniques.

Finally, this study builds on the body of existing knowledge to offer an additional investigation into the effect of brand experience on brand equity through the mediation of brand authenticity in a setting that has not yet been empirically investigated for new luxury fashion brands in Egypt.

6.3. Practical implications

This research offers beneficial implications for new luxury fashion markets in Egypt. First, our study revealed that sensory, affective, intellectual, and behavioral experiences positively influence brand authenticity. A brand is considered successful if it engages the mind and body, excites the senses, and makes the consumer feel good (Brakus et al., Citation2009). Therefore, marketing managers should consider how to attract customers’ five senses to increase perceived authenticity in their eyes by creating brands that keep their promises through continuity, originality, reliability, and naturalness. Thus, good multidimensional brand experiences aid managers in both retaining and attracting new customers (Safeer et al., Citation2021).

Second, our research found that an authentic brand positively influences the four dimensions of brand equity. Managers should design authentic brands to increase customer perceptions of brand equity for their offerings by focusing on four things: (1) Managers should develop new luxury fashion brand awareness using authenticity ambience as a guide for designing their advertising campaigns (Tran et al., Citation2021) by focusing on words that reflect authenticity characteristics, e.g., continuity, consistency, originality, reliability, credibility, trustfulness, naturalness, and genuineness. Moreover, managers should develop marketing strategies to advertise the brand name to reflect the authenticity benefits. (2) New luxury brand managers should enhance brand associations by designing fashion brands that are linked in customers’ memories (Aaker, Citation1991). (3) Managers should improve customer perceptions of brand quality by offering excellent products that are unique and genuine. (4) Lastly, brand managers should encourage loyal customers by providing discounts and unique offers to encourage them to recommend their brands.

Third, our findings found that brand experience positively influences brand equity. Marketing managers can improve brand equity by offering their customers a memorable, pleasurable, and enjoyable experience as a means of appealing to customers and building brand equity. Finally, our results revealed that the relationship between brand experience and brand equity is mediated by brand authenticity. Managers can promote their brands using sensory and intellectual marketing tactics, using authentic brands to satisfy customers’ cognitive needs. Subsequently, managers can apply sensory and intellectual tactics on social media platforms to improve brand equity (Safeer et al., Citation2021). Additionally, managers should apply affective and behavioral experiences by offering customized and personalized service with unique, reliable, consistent, and continuous attributes. Consequently, these two types of experiences may strengthen brand authenticity, which in turn is linked to customers’ memories (Aaker, Citation1991), by designing brands with functional, experiential, and symbolic values that lead to enhanced brand equity.

6.4. Limitations and future studies

This research has constraints that could be investigated in future research. First, the research findings cannot be generalized beyond the Egyptian context because we collected data only from Egyptian customers. Future studies should be conducted in other countries. Second, this study only covered new luxury fashion brands. Future studies may encompass several product categories, such as comparing brand authenticity across industries. Furthermore, while the findings of this study cannot be extended beyond the consumer brand category, future research in developing countries may be conducted in other service sector types, such as hotels and restaurants. Third, for collecting data, this study relied on a convenience sample. Future studies should collect data on a larger scale. Fourth, the current study is a cross-sectional study; future research may conduct a longitudinal study. Fifth, brand authenticity was examined as a second-order factor. Future studies may examine it as a first-order factor, examining different determinants and outcomes of brand authenticity for new luxury fashion brands. Sixth, this study examined brand authenticity as a mediator. Future studies may incorporate the moderating role of brand familiarity, brand involvement, and demographics.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aaker, D. A. (1991). Building brand equity. The Free Press.

- Aaker, D. A. (1996). Measuring brand equity across products and markets. California Management Review, 38(3), 102–22. Available from. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165845.

- Abrar, M., Baig, S. A., & Hussain, I. (2020). Understanding brand love in fashion clothing online brand communities: Moderating role of social identity. Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences, 40(1), 315–325.

- Ajitha, S., & Sivakumar, V. J. (2019). The moderating role of age and gender on the attitude towards new luxury fashion brands. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 23(4), 440–465. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-05-2018-0074

- Akbar, M. M., & Wymer, W. (2017). Refining the conceptualization of brand authenticity. Journal of Brand Management, 24(1), 14–32. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-016-0023-3

- Akoglu, H. E., & Özbek, O. (2021). The effect of brand experiences on brand loyalty through perceived quality and brand trust: A study on sports consumers. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing & Logistics, 34(10), 2130–2148. Preprint. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-05-2021-0333

- Altaf, M., Iqbal, N., Mohd Mokhtar, S. S., & Sial, M. H. (2017). Managing consumer-based brand equity through brand experience in Islamic banking. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 8(2), 218–242. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-07-2015-0048

- Amoroso, S., Pattuglia, S., & Khan, I. (2021). Do millennials share similar perceptions of brand experience? A clusterization based on brand experience and other brand-related constructs: The case of Netflix. Journal of Marketing Analytics, 9(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41270-021-00103-0

- Appiah-Nimo, K., Muthambi, A., & Devey, R. (2023). Consumer-based brand equity of South African luxury fashion brands. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, ahead-of–print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-10-2021-0277

- Bertoli, G., Busacca, B., Ostillio, M. C., & DiVito, S. (2016). Corporate museums and brand authenticity: Explorative research of the Gucci Museo. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 7(3), 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2016.1166716

- Brakus, J. J., Schmitt, B. H., & Zarantonello, L. (2009). Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does It Affect Loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 73(3), 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.3.52

- Bruhn, M., Schoenmüller, V., Schäfer, D., & Heinrich, D. (2012). Brand authenticity: Towards a deeper understanding of its conceptualization and measurement. Advances in Consumer Research, 40.

- Business today Egypt. (2021). Global retail development index, Retrieved September 15, 2022: https://www.businesstodayegypt.com/Article/1/1203/Egypt-jumps-19-spots-on-2021-Global-Retail-Development-Index.

- Carrizo Moreira, A., Freitas, P. M., & Ferreira, V. M. (2017). The effects of brand experiences on quality, satisfaction and loyalty: An empirical study in the telecommunications multiple-play service market. Innovar, 27(64), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.15446/innovar.v27n64.62366

- Chen, X., You, E. S., Lee, T. J., & Li, X. (2021). The influence of historical nostalgia on a heritage destination’s brand authenticity, brand attachment, and brand equity: Historical nostalgia on a heritage destination’s brand authenticity. International Journal of Tourism Research, 23(6), 1176–1190. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2477

- Chen-Yu, J., Cho, S., & Kincade, D. (2016). Brand perception and brand repurchase intent in online apparel shopping: An examination of brand experience, image congruence, brand affect, and brand trust. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 7(1), 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2015.1110042

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern Methods for Business Research, 295(2), 295–336.

- Choi, H., Ko, E., Kim, E. Y., & Mattila, P. (2015). The role of fashion brand authenticity in product management: A holistic marketing approach: Fashion brand authenticity in product management. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 32(2), 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12175

- Dwivedi, A., & McDonald, R. (2018). Building brand authenticity in fast-moving consumer goods via consumer perceptions of brand marketing communications. European Journal of Marketing, 52(7/8), 1387–1411. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-11-2016-0665

- El Din, D. G., & El Sahn, F. (2013). Measuring the factors affecting Egyptian consumers’ intentions to purchase global luxury fashion brands. The Business & Management Review, 3(4), 44.

- Emari, H., & Emari, H. (2012). The mediatory impact of brand loyalty and brand image on brand equity. African Journal of Business Management, 6(17). https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM11.788

- Eng, T. Y., & Bogaert, J. (2010). Psychological and cultural insights into consumption of luxury western brands in India. Journal of Customer Behaviour, 9(1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1362/147539210X497620

- Ertemel, A. V., & Civelek, M. E. (2020). The role of brand equity and perceived value for stimulating purchase intention in b2c e-commerce web sites. Business and Economics Research Journal, 10(1), 233–243. https://doi.org/10.20409/berj.2019.165

- Etikan, I. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

- Falk, R. F., & Miller, N. B. (1992). A primer for soft modeling (1st ed.). University of Akron Press.

- Fionda, A. M., & Moore, C. M. (2009). The anatomy of the luxury fashion brand. Journal of Brand Management, 16(5–6), 347–363. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2008.45

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Fritz, K., Schoenmueller, V., & Bruhn, M. (2017). Authenticity in branding – exploring antecedents and consequences of brand authenticity. European Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 324–348. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-10-2014-0633

- Gilmore, J. H., & Pine, B. J. (2007). Authenticity: What consumers really want. Harvard Business School Press.

- Godden, B. (2004). Sample size formulas. Journal of Statistics, 3(66), 1.

- Govarchin, M. E. (2019). The moderating effect of requirement to the uniqueness in the effect of brand authenticity on brand love in hospitality industry. Humanidades & Inovação, 6(13), 55–71.

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). Pls-sem: indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. European Journal of Marketing, 53(4), 566–584. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-10-2018-0665

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6

- Handa, M., & Khare, A. (2013). Gender as a moderator of the relationship between materialism and fashion clothing involvement among Indian youth: Materialism and fashion clothing involvement among Indian youth. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 37(1), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2011.01057.x

- Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. John Wiley & Sons Inc. https://doi.org/10.1037/10628-000

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New challenges to international marketing (Vol. 39, pp. 277–319). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1474-7979(2009)0000020014

- Hernandez-Fernandez, A., & Lewis, M. C. (2019). Brand authenticity leads to perceived value and brand trust. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 28(3), 222–238. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJMBE-10-2017-0027

- Hitzler, P. A., & Müller-Stewens, G. (2017). The strategic role of authenticity in the luxury business. In Sustainable management of luxury (pp. 29–60). Springer Singapore.

- Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 132. https://doi.org/10.1086/208906

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives, Structural Equation Modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Husain, R., Ahmad, A., & Khan, B. M. (2022). The impact of brand equity, status consumption, and brand trust on purchase intention of luxury brands. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2034234. Edited by G. Liu. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2034234

- Hussein, A. S. (2018). Effects of brand experience on brand loyalty in Indonesian casual dining restaurant: Roles of customer satisfaction and brand of origin. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 24(1), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.20867/thm.24.1.4

- Iglesias, O., Markovic, S., & Rialp, J. (2019). How does sensory brand experience influence brand equity? Considering the roles of customer satisfaction, customer affective commitment, and employee empathy. Journal of Business Research, 96, 343–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.05.043

- Infomineo. (2014). Overview of the retail market in Egypt. viewed 2 August 2023, available at: https://infomineo.com/overview-of-the-retail-market-in-egypt/.

- Jeon, H. M., & Yoo, S. R. (2021). The relationship between brand experience and consumer-based brand equity in grocerants. Service Business, 15(2), 369–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-021-00439-8

- Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299305700101

- Khan, I., Fatma, M., Kumar, V., & Amoroso, S. (2021). Do experience and engagement matter to millennial consumers? Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 39(2), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1108/mip-01-2020-0033

- Khan, I., Rahman, Z., & Fatma, M. (2016). The concept of online corporate brand experience: An empirical assessment. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 34(5), 711–730. https://doi.org/10.1108/mip-01-2016-0007

- Kim, J.-H. (2019). Imperative challenge for luxury brands: Generation Y consumers’ perceptions of luxury fashion brands’ e-commerce sites. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 47(2), 220–244. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-06-2017-0128

- Kim, J. E., Lloyd, S., Adebeshin, K., & Kang, J. Y. M. (2019). Decoding fashion advertising symbolism in masstige and luxury brands. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 23(2), 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-04-2018-0047

- Kim, Y.-K., & Sullivan, P. (2019). Emotional branding speaks to consumers’ heart: The case of fashion brands. Fashion and Textiles, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40691-018-0164-y

- Kumar, A., Lee, H. J., & Kim, Y. K. (2009). Indian consumers’ purchase intention toward a United States versus local brand. Journal of Business Research, 62(5), 521–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.06.018

- Lassar, W., Mittal, B., & Sharma, A. (1995). Measuring customer‐based brand equity. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 12(4), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363769510095270

- Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits, structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1

- Liu, K.-N., Tsai, T.-I., Xiao, Q., & Hu, C. (2021). The impact of experience on brand loyalty: Mediating effect of images of Taiwan hotels. Journal of China Tourism Research, 17(3), 395–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388160.2020.1777238

- Lu, A. C. C., Gursoy, D., & Lu, C. Y. (2015). Authenticity perceptions, brand equity and brand choice intention: The case of ethnic restaurants. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 50, 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.07.008

- Manthiou, A., Kang, J., Hyun, S. S., & Fu, X. X. (2018). The impact of brand authenticity on building brand love: An investigation of impression in memory and lifestyle-congruence. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 75, 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.03.005

- Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology. M.I.T. Press.

- Murshed, F., Dwivedi, A., & Nayeem, T. (2023). Brand authenticity building effect of brand experience and downstream effects. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 32(7), 1032–1045. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-02-2021-3377

- Napoli, J., Dickinson, S. J., Beverland, M. B., & Farrelly, F. (2014). Measuring consumer-based brand authenticity. Journal of Business Research, 67(6), 1090–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.06.001

- Netemeyer, R. G., Krishnan, B., Pullig, C., Wang, G., Yagci, M., Dean, D., Ricks, J., & Wirth, F. (2004). Developing and validating measures of facets of customer-based brand equity. Journal of Business Research, 57(2), 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(01)00303-4

- Oh, H., Prado, P. H. M., Korelo, J. C., & Frizzo, F. (2019). The effect of brand authenticity on consumer–brand relationships. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 28(2), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-09-2017-1567

- Papadopoulou, C., Vardarsuyu, M., & Oghazi, P. (2023). Examining the relationships between brand authenticity, perceived value, and brand forgiveness: The role of cross-cultural happiness. Journal of Business Research, 167(114154), 114154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114154

- Park, J., Hong, E., & Park, Y. N. (2023). Toward a new business model of retail industry: The role of brand experience and brand authenticity. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 74, 103426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103426

- Pina, R., & Dias, Á. (2021). The influence of brand experiences on consumer-based brand equity. Journal of Brand Management, 28(2), 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-020-00215-5

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review, 76(4), 97–105.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. Available from. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452.

- Raza, M., Abd Rani, S. H., & Isa, N. M. (2021). Does brand authenticity bridges the effect of experience, value, and engagement on brand love: A case of fragrance industry of Pakistan. PalArch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/egyptology, 18(4), 6456–6474.

- Ren, Y., Choe, Y., & Song, H. (2023). Antecedents and consequences of brand equity: Evidence from Starbucks coffee brand. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 108(103351), 103351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103351

- Robbins, D., Colligan, K., & Hall, J. (2009). Brand authenticity: A new way forward in customer experience management. MI, Second to None, 1–16.

- Rodrigues, P., Pinto Borges, A., & Sousa, A. (2021). Authenticity as an antecedent of brand image in a positive emotional consumer relationship: The case of craft beer brands. EuroMed Journal of Business, 17(4), 634–651. Preprint. https://doi.org/10.1108/EMJB-03-2021-0041

- Rodríguez-López, M. E., Del Barrio-García, S., & Alcántara-Pilar, J. M. (2020). Formation of customer-based brand equity via authenticity: The mediating role of satisfaction and the moderating role of restaurant type. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(2), 815–834. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2019-0473

- Safeer, A. A., Abrar, M., Liu, H., & Yuanqiong, H. (2022). Effects of perceived brand localness and perceived brand globalness on consumer behavioral intentions in emerging markets. Management Decision, 60(9), 2482–2502. https://doi.org/10.1108/md-10-2021-1296

- Safeer, A. A., He, Y., & Abrar, M. (2021). The influence of brand experience on brand authenticity and brand love: An empirical study from Asian consumers’ perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing & Logistics, 33(5), 1123–1138. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-02-2020-0123

- Salary explorer. (2023). Average salary in Egypt 2023 - the complete guide. Retrieved August 18, 2023: http://www.salaryexplorer.com/salary-survey.php?loc=64&loctype=1.

- Segura, A. (2019, March 11). The fashion retailer the fashion pyramid of brands. The Fashion Retailer. https://fashionretail.blog/2019/03/11/the-fashion-pyramid-of-brands/

- Shahzad, M. F., Bilal, M., Xiao, J., & Yousaf, T. (2019). Impact of smartphone brand experience on brand equity: With mediation effect of hedonic emotions, utilitarian emotions and brand personality. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 10(2), 440–464. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-04-2017-0045

- Shang, W., Yuan, Q., & Chen, N. (2020). Examining structural relationships among brand experience, existential authenticity, and place attachment in slow tourism destinations. Sustainability, 12(7), 2784. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072784

- Sharma, R. (2016). Effect of celebrity endorsements on dimensions of customer-based brand equity: Empirical evidence from Indian luxury market. Journal of Creative Communications, 11(3), 264–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973258616667185

- Siddiqui, K. (2022). Brand equity trend analysis for fashion brands (2001-2021). Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 13(3), 238–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2022.2032792

- Silverstein, M. J., & Fiske, N. (2003). Luxury for the masses. Harvard Business Review, 81(4), 48–59.

- Siu, N. Y.-M., Kwan, H. Y., & Zeng, C. Y. (2016). The role of brand equity and face saving in Chinese luxury consumption. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 33(4), 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-08-2014-1116

- Slabu, L., Lenton, A. P., Sedikides, C., & Bruder, M. (2014). Trait and state authenticity across cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(9), 1347–1373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022114543520

- Soenyoto, F. L. (2015). The impact of brand equity on brand preference and purchase intention in Indonesia’s bicycle industry: A case study of polygon. iBuss Management, 3(2), 99–108.

- Sohaib, M., Mlynarski, J., & Wu, R. (2022). Building brand equity: The impact of brand experience, brand love, and brand engagement—A case study of customers’ perception of the Apple brand in China. Sustainability, 15(1), 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010746

- Srinivasan, V., Park, C. S., & Chang, D. R. (2005). An approach to the measurement, analysis, and prediction of brand equity and its sources. Management Science, 51(9), 1433–1448. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1050.0405

- Statista. (2022a) Luxury fashion: Sales growth. Retrieved August 30, 2022: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1314120/luxury-fashion-sales-growth/.

- Statista. (2022b) Luxury fashion: Worldwide. Retrieved August 30, 2022: https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/luxury-goods/luxury-fashion/worldwide.

- Statista. (2023). Luxury fashion - Egypt | statista market forecast’. Retrieved August 22, 2023: https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/luxury-goods/luxury-fashion/egypt.

- Stokburger-Sauer, N. E., & Teichmann, K. (2013). Is luxury just a female thing? The role of gender in luxury brand consumption. Journal of Business Research, 66(7), 889–896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.12.007

- Talaat, R. M. (2022). Fashion consciousness, materialism and fashion clothing purchase involvement of young fashion consumers in Egypt: The mediation role of materialism. Journal of Humanities and Applied Social Sciences, 4(2), 132–154. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHASS-02-2020-0027

- Tran, V. D., & Nguyen, N. T. T. (2022). Investigating the relationship between brand experience, brand authenticity, brand equity, and customer satisfaction: Evidence from Vietnam. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2084968. Edited by P. Foroudi. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2084968

- Tran, P. K. T., Nguyen, V. K., & Tran, V. T. (2021). Brand equity and customer satisfaction: A comparative analysis of international and domestic tourists in Vietnam. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 30(1), 180–194. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-08-2019-2540

- Tran, V. D., Vo, T. N. L., & Dinh, T. Q. (2020). The relationship between brand authenticity, brand equity and customer satisfaction. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics & Business, 7(4), 213–221. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no4.213

- Truong, Y., McColl, R., & Kitchen, P. J. (2009). New luxury brand positioning and the emergence of masstige brands. Journal of Brand Management, 16(5–6), 375–382. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2009.1

- Uysal, A., & Okumuş, A. (2022). The effect of consumer-based brand authenticity on customer satisfaction and brand loyalty. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing & Logistics, 34(8), 1740–1760. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-05-2021-0358

- Wetzels, M., Odekerken-Schröder, G., & Van Oppen, C. (2009). Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Quarterly, 33(1), 177. https://doi.org/10.2307/20650284

- Yoo, B., & Donthu, N. (2001). Developing and validating a multidimensional consumer-based brand equity scale. Journal of Business Research, 52(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(99)00098-3

- Yoo, B., Donthu, N., & Lee, S. (2000). An examination of selected marketing mix elements and brand equity. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(2), 195–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070300282002

- Zollo, L., Filieri, R., Rialti, R., & Yoon, S. (2020). Unpacking the relationship between social media marketing and brand equity: The mediating role of consumers’ benefits and experience. Journal of Business Research, 117, 256–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.001

Appendix

List of new luxury brands for respondents:

Calvin Klein

Tommy Hilfiger

Michael Kors

Us polo

Coach

Dkny

Guess

Ralph lauren

Under Armour

Adidas

Nike