Abstract

Materialism is a prevalent phenomenon in contemporary society and exerts a substantial influence on consumer behavior. Materialistic individuals prioritize their life goals, success criteria, and sources of happiness through the accumulation of wealth, often exhibiting a proclivity towards narcissism. Concurrently, conspicuous consumption entails the consumption of products or services primarily to fulfill social needs. These three facets—materialism, narcissistic behavior, and conspicuous consumption on social media—have garnered significant attention in academic research. However, prior investigations have not delved into the role of narcissistic behavior in elucidating the positive association between materialism and conspicuous consumption on social media. To address this gap, this study employed an online survey method, involving 330 respondents, with 292 questionnaires deemed suitable for analysis. The structural equation model analysis unveiled several noteworthy findings. Firstly, materialistic orientation exhibited a positive and significant impact on both narcissistic behavior and conspicuous consumption on social media. Secondly, narcissistic behavior demonstrated a positive influence on conspicuous consumption on social media. Finally, this study confirmed that narcissistic behavior mediates the positive relationship between materialism and conspicuous consumption on social media. As a result, this study constitutes a valuable contribution to the literature on consumer behavior.

1. Introduction

In recent years, Indonesia’s consumer culture has undergone a profound transformation, driven by the influential emergence of celebrity purchasing behavior on social media platforms. The widespread adoption of visually-engaging platforms like YouTube, Instagram, and Facebook has ushered in a paradigm shift in consumer-brand interactions and subsequently, has redefined consumption patterns (Duan & Dholakia, Citation2017; Wahab et al., Citation2022). Indonesia, celebrated for its rich and diverse celebrity culture, has emerged as a focal point for conspicuous consumption phenomena. Prominent figures, acknowledged for their achievements across various domains, leverage their online personas to showcase opulent acquisitions, encompassing luxury sport automobiles like Ferrari and Lamborghini, exclusive timepieces from renowned brands like Rolex and Richard Mille, and coveted fashion items from prestigious houses such as Hermes, Gucci, and Louis Vuitton (Nanda, Citation2020; Walker, Citation2023). These conspicuous displays of wealth have not only redefined contemporary consumerism but have also brought the phenomenon into the spotlight. This study embarks on an exploration into the intertwined domains of conspicuous consumption behavior (CCB) and its intricate relationship with narcissistic behavior, both of which collectively contribute to the narrative of modern consumer culture.

Within the field of consumer behavior, the observed phenomena in Indonesia align closely with the concept of CCB. CCB refers to “the process of gaining status or social prestige from the acquisition and consumption of goods that the individual and significant others perceive to be high in status” (O’Cass & Frost, Citation2002, p. 68). It transcends mere consumption; it is a symbolic gesture, a performative act that communicates one’s place within the social hierarchy. Notably, CCB is closely intertwined with the notion of narcissistic behavior (Sedikides & Hart, Citation2022; Taylor & Strutton, Citation2016). Narcissism, as a personality trait, encompasses a range of self-centered tendencies, including a heightened sense of self-importance, a desire for admiration, and a lack of empathy for others (Campbell et al., Citation2002). Individuals with higher scores in narcissistic traits are often more inclined toward conspicuous displays of wealth and status (Taylor & Strutton, Citation2016). Flaunting possessions, a hallmark of narcissistic behavior, aligns seamlessly with CCB. Together, these behaviors manifest as ostentatious displays of wealth and luxury, conspicuously showcased on social media platforms in Indonesia.

Scholarly discourse has long been captivated by the nuanced interplay between CCB and consumer narcissism. Previous research endeavors have explored various facets of this phenomenon. One notable facet of exploration centers on the influence of cultural values on CCB. Studies have demonstrated that values, including collectivism and materialism, exert a substantial influence on an individual’s propensity for CCB. For instance, research conducted by Zakaria et al. (Citation2021) has illuminated the impact of collectivism and materialism values on CCB, while revealing that religious values exert no significant effect on CCB. Concurrently, the proliferation of social media platforms has ushered in a new epoch in consumer behavior. The usage of social media has been linked to the amplification of envious and narcissistic behaviors among its users, thereby further fueling conspicuous online consumption behavior (COCB) (Taylor & Strutton, Citation2016). The digital age has metamorphosed the manner in which individuals engage with brands, their peers, and society at large. Social media platforms function as both a mirror and a stage, nurturing a culture of self-promotion and digital exhibitionism. Consequently, COCB, characterized by the ostentatious display of possessions and experiences online, has become an integral facet of the contemporary consumer experience.

While previous research has shed light on several dimensions of conspicuous consumption and consumer narcissism, a significant research gap remains. The specific role of narcissistic behavior in mediating the relationship between materialism and COCB on social media has not been thoroughly explored. Materialism, as a value orientation, pertains to the significance individuals place on the acquisition and possession of material goods as a source of life satisfaction and self-identity. Empirical evidence suggests that materialism is closely intertwined with both narcissistic behavior and CCB, as documented by Bergman et al. (Citation2013), Górnik-Durose and Pilch (Citation2016), and Shrum et al. (Citation2013). This study endeavors to address this critical research gap through a comprehensive exploration. Our aim is to investigate not only the direct effects of materialism orientation and narcissistic behavior on COCB within the digital sphere but also to scrutinize the mediating role of narcissistic behavior in elucidating the positive relationship between materialism orientation and COCB. Through rigorous empirical analysis, we endeavor to unveil the underlying mechanisms driving COCB in the context of social media.

This study is propelled by a dual objective. Primarily, we aspire to unravel the direct effects of materialism orientation and narcissistic behavior on COCB within the dynamic landscape of social media. Secondly, we delve into the intricate dynamics at play, elucidating the mediating role of narcissistic behavior in understanding the positive relationship between materialism orientation and COCB. This dual-pronged approach enables us to paint a comprehensive portrait of COCB and its underlying determinants within the Indonesian context.

The significance of this research extends beyond the realm of academia. As businesses navigate the ever-evolving landscape of consumer behavior in the digital age, the insights derived from this study hold substantial practical value. Understanding the multifaceted interplay of materialism, narcissism, and COCB on social media is paramount in shaping effective marketing strategies. Our findings offer actionable insights for businesses seeking to navigate the complex terrain of consumer culture, particularly within the Indonesian market.

2. Literature review

2.1. CCB and COCB

The concept of CCB, originating from Theory of the Leisure Class (Veblen, Citation1992), offers valuable insights into the motivations behind individuals’ consumption habits. Veblen’s theory argues that conspicuous consumption of valuable goods is a means for individuals of leisure to establish their reputation (Veblen, Citation1992, p. 36). This theory underscores that individuals often engage in consumption not solely for utilitarian or practical reasons but to conspicuously display their wealth, social standing, and prestige. This behavior effectively transforms material possessions into symbols of personal success and societal status, frequently leading to the acquisition of luxury items that serve as conspicuous markers of affluence. CCB posits that individuals derive satisfaction not only from the practical utility of products but also from comparing their possessions with those of others, thus highlighting its socially determined nature (Taylor & Strutton, Citation2016). Furthermore, conspicuous consumption serves as a mode of self-expression, enabling individuals to convey their values, creativity, lifestyle, and self-identity (Edgell, Citation1992).

In the digital age, conspicuous online consumption behavior (COCB) has emerged as a transformative extension of traditional CCB (Qattan & Al Khasawneh, Citation2020; Taylor & Strutton, Citation2016). COCB leverages the power of social media and the internet, providing individuals with a global platform to publicly exhibit their wealth, social status, and lifestyle choices. This phenomenon has gained significant traction among millennials, particularly concerning luxury fashion goods (Burnasheva & Suh, Citation2021; Zakaria et al., Citation2021). Prominent social media platforms, such as Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, and TikTok, enable users to prominently showcase their luxury possessions, signaling their social status and enhancing their self-image. COCB is heavily influenced by the concept of self-image congruity, wherein individuals seek alignment between their self-concept and a brand’s image, further propelling their conspicuous consumption choices (Burnasheva & Suh, Citation2021; O’Cass & Frost, Citation2002). A critical distinction between COCB and CCB lies in the unprecedented reach and immediacy that digital platforms offer. In the past, conspicuous consumption was often confined to one’s immediate social circle and local community; however, today, individuals can broadcast their consumption choices to a global audience, significantly amplifying the potential for comparison and competition (Taylor & Strutton, Citation2016).

Furthermore, COCB is strongly influenced by the concept of self-image congruity (Burnasheva & Suh, Citation2021). This psychological theory posits that individuals seek alignment between their self-concept and the image projected by a brand or product (Jacob et al., Citation2020). In the context of COCB, individuals meticulously curate their online presence to align with their chosen brands or lifestyles, further reinforcing their conspicuous consumption choices and strengthening the desire to showcase their identity and values on social media platforms (Qattan & Al Khasawneh, Citation2020).

The role of social media in shaping conspicuous consumption is undeniable. Social networking sites have magnified the visibility of consumption choices, effectively making nearly all consumption potentially conspicuous. Users now publicly express their self-concept through luxury items, with the act of posting purchases on social media becoming a manifestation of conspicuous spending (Duan & Dholakia, Citation2017). This phenomenon closely aligns with Veblen’s theory and underscores the profound impact of social media on seemingly irrational consumption choices, particularly in the realm of luxury fashion. Social media platforms offer various avenues for individuals to engage in COCB, including sharing images of luxury purchases, documenting extravagant experiences like lavish vacations or fine dining, and endorsing specific brands or products through sponsored content. The validation received in the form of likes, comments, and shares serves as immediate indicators of social approval and can further reinforce the behavior (Burnasheva & Suh, Citation2021; Taylor & Strutton, Citation2016). Additionally, social media algorithms play a significant role in perpetuating COCB. These algorithms are designed to maximize user engagement by displaying content that aligns with an individual’s previous interactions and interests, continually exposing users to aspirational content and fueling the desire for conspicuous consumption.

In conclusion, conspicuous consumption behavior (CCB) and conspicuous online consumption behavior (COCB) are complex phenomena deeply rooted in human psychology, social dynamics, and the digital age. While CCB holds historical significance, COCB represents a digital transformation that has globalized and intensified conspicuous consumption. Social media platforms, with their ability to showcase consumption choices and facilitate social comparisons, are at the forefront of this evolutionary shift.

2.2. Materialism

Materialism, at its core, represents a philosophical perspective deeply rooted in the belief that the material realm constitutes the fundamental and exclusive reality (Richins & Dawson, Citation1992). This viewpoint holds substantial implications for understanding human behavior, influencing the development of personality traits, the formation of values, and the guidance of individual aspirations. In a succinct definition, materialism can be described as “the importance ascribed to the ownership and acquisition of material goods in achieving major life goals or desired states” (Richins, Citation2004, p. 210). It serves as a fundamental driving force within contemporary hedonistic societies, fundamentally shaping individuals’ perceptions and pursuits of life goals (Shrum et al., Citation2013). Beyond mere consumerism, materialism encapsulates a profound belief in the intrinsic value of material possessions.

The intricate interplay between materialism, personality traits, and values merits close examination. Eminent scholars like Belk (Citation1984) have illuminated the symbiotic relationship between materialism and goals that prioritize material possessions and goods in life. This connection highlights the formative role of materialism in constructing personal identities and prioritizing life objectives.

In business contexts, Shrum et al. (Citation2013) provide enlightening insights into the nuanced aspects of materialism. They define it as the extent to which individuals engage in self-development and self-maintenance through the strategic acquisition of products, services, experiences, or relationships endowed with symbolic value. This perspective reveals the strategic considerations employed by marketers to cater to the preferences and desires of materialistic consumers. Materialistic individuals exhibit discernment in their consumption patterns, favoring a predilection for products and services that convey social status or affiliation with specific social groups (Lim et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, materialists often express a preference for global brands due to their high social signaling value (Fastoso & González-Jiménez, Citation2020) and report higher levels of life satisfaction (Thyroff & Kilbourne, Citation2018). These consumption preferences hold significant implications for businesses targeting this discerning consumer segment.

2.3. Narcissistic behavior

Consumer purchasing behavior is shaped by a multifaceted array of factors, among which personality plays a significant role. Each unique personality trait exerts an impact on product selection, choice of retail establishments, and the overall purchasing process. One personality trait that warrants comprehensive investigation for its role in consumer behavior is narcissism. Individuals possessing narcissistic traits tend to manifest characteristics such as egocentric exceptionalism, characterized by a belief in their own superiority, social egoism, marked by self-serving and antagonistic tendencies, and outward displays of extraversion, exhibitionism, and dominance (Velov et al., Citation2014; Zhu et al., Citation2021). Such individuals are deeply concerned with their identity and seek validation within society (Sedikides & Hart, Citation2022). Notably, there has been an observable rise in narcissistic behaviors, particularly among younger cohorts (Neave et al., Citation2020). It is important to note that narcissistic consumers often exhibit unfavorable post-purchase behaviors, including feelings of dissatisfaction, the propagation of negative word-of-mouth, and diminished brand loyalty (Saenger et al., Citation2013).

Within the realm of narcissism, two primary classifications exist: overt narcissism and covert narcissism (Wink, Citation1991). Both types share certain common traits, such as a propensity for self-aggrandizement and a strong desire for external validation (Sedikides & Hart, Citation2022). Individuals characterized by overt narcissism are typically self-reliant, outgoing, cheerful, and self-assured (Fastoso et al., Citation2018; Shane-Simpson et al., Citation2020). They possess a heightened self-concept and openly express themselves. In contrast, those with covert narcissism display traits of sensitivity, anxiety, insecurity, and a tendency to frequently overestimate their abilities, often grappling with lower self-esteem and feelings of inferiority (Fastoso et al., Citation2018; Shane-Simpson et al., Citation2020). Moreover, observable disparities in mental health outcomes exist between these two narcissistic subtypes. Individuals with overt narcissism tend to exhibit positive mental health indicators, as evidenced by increased life satisfaction and subjective well-being, while individuals with covert narcissism often confront mental health challenges, including heightened levels of anxiety, depression, and diminished self-confidence (Zhu et al., Citation2021).

2.4. Hypotheses development

Materialism underscores the pursuit of life goals, success criteria, and happiness through the acquisition of wealth, as emphasized by Richins and Dawson (Citation1992). Furthermore, it leads individuals to assess others based on their material possessions and prioritize financial accumulation over personal development, encompassing facets such as personal growth and self-esteem, and social relationships, including family life and friendships (Richins, Citation2004; Zakaria et al., Citation2021). This materialistic inclination extends into the business domain, where it manifests into a pronounced consumer preference for luxury goods, which augment their image and social status (Husain et al., Citation2022; Khan et al., Citation2022). Consequently, it is not unexpected that imported products and global brands consistently maintain high demand, especially among materialistic consumers residing in developing countries (Fastoso & González-Jiménez, Citation2020; Masoom & Moniruzzaman Sarker, Citation2017), where superior quality conveys hedonic social values.

Studies have shown that individuals characterized by high levels of materialism tend to assign elevated value to expensive items, linking them closely with perceptions of success (e.g., Kapferer & Valette-Florence, Citation2019). These individuals place substantial importance on the social symbolism inherent in luxury goods, viewing such items as potent representations of an individual’s status, dignity, and honor (Gierl & Huettl, Citation2010). Luxury items also serve as effective tools for expressing one’s identity, a concept that aligns with the concept of CCB (Kenton, Citation2021; Taylor & Strutton, Citation2016). When luxury products distinguish themselves from those owned by friends and colleagues, they generate a sense of social recognition and identity that garners respect and admiration within the individual’s social sphere (Gierl & Huettl, Citation2010). Consequently, products that resonate with the belief systems of specific social groups tend to enhance social acceptance. Thus, conspicuous consumption emerges as a clear indicator of social status, symbolizing an individual’s wealth and success, regardless of the resources expended. Moreover, it is worth noting that materialism stands out as the predominant value orientation driving conspicuous consumption behavior (Zakaria et al., Citation2021). Considering the arguments presented, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1:

Materialistic orientation has a positive effect on COCB on social media.

Materialistic individuals, who attach their self-worth to possessions, may perceive themselves as superior due to their material success, aligning with narcissistic traits (Velov et al., Citation2014). This reliance on external validation further strengthens the connection between materialism and narcissism. As materialists accumulate possessions, their sense of self-importance burgeons, encouraged by the rewards of admiration and elevated status (Sedikides & Hart, Citation2022). The display of these acquisitions serves as a visible marker of success, drawing attention in a manner akin to narcissistic behavior (Górnik-Durose & Pilch, Citation2016). Prioritizing possessions over relationships can exacerbate this cyclical phenomenon, whereby materialism reinforces narcissistic tendencies. Building on the arguments presented, this study posits the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2:

Materialistic orientation has a positive effect on narcissistic.

Previous research has demonstrated that individuals with high levels of narcissism exhibit a preference for purchasing luxury and customized products tailored for specific groups (de Bellis et al., Citation2016; Neave et al., Citation2020). They also tend to favor elite retailers (Naderi & Paswan, Citation2006). The act of acquiring luxury goods is perceived as prestigious, enabling individuals to stand out in society and garner recognition that elevates their status from the ordinary to the elite echelons of the community (de Bellis et al., Citation2016). The study conducted by Sedikides and Hart (Citation2022) sheds light on several reasons behind narcissistic consumers’ inclination towards luxury goods and services. These reasons include individuals’ goals and missions that imbue meaning and recognition into their lives (Zhu et al., Citation2021), which has a positive association with mental health. Narcissistic individuals tend to perceive life through the lens of materialistic satisfaction, closely linked to extrinsic goals such as fame (Kasser et al., Citation2007). Another contributing factor is the pride that narcissistic individuals take in their financial success and their positive sense of distinctiveness, which enhances their self-image and pride (Sedikides & Hart, Citation2022). This phenomenon significantly encourages COCB on social media platforms (Taylor & Strutton, Citation2016). Research findings further indicate that in the context of short-term dating, narcissistic men are more inclined to engage in conspicuous consumption, whereas women who engage in conspicuous consumption are more confident in their ability to attract potential partners successfully (Sundie et al., Citation2011). Consequently, the arguments presented above critically support the notion of a positive relationship between narcissistic behavior and its impact on COCB on social media. Therefore, the following hypotheses are formulated:

Hypothesis 3:

Narcissistic has a positive effect on COCB on social media.

By integrating Hypotheses 2 and 3, we can further propose that narcissistic behavior plays a significant role in mediating the positive relationship between materialistic orientation and COCB on social media. Consequently, this study posits the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4:

Narcissistic behavior mediates a positive relationship between materialistic orientation and COCB on social media.

3. Research method

3.1. Research design

A cross-sectional study was employed to examine the interrelationships among three pivotal variables: the independent variable (materialistic orientation), the dependent variable (COCB on social media), and the mediating variable (narcissistic behavior). For the purpose of data collection, an online questionnaire was developed using Google Forms, with its content proficiently translated into the Indonesian language. The introductory section of the questionnaire delineated the study’s objectives, provided instructions for completion, and emphasized the importance of respondents’ voluntary participation.

In order to mitigate potential response bias, following the recommendations of Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003), meticulous efforts were exerted in designing the questionnaire. This entailed the randomization of the sequence in which inquiries pertaining to measurement items were presented. Additionally, the identification of underlying variables was deliberately obscured, and the respondents’ personal information, encompassing details such as names, mobile phone numbers, and email addresses, were rendered anonymous. As such, this approach granted respondents complete independence, with explicit acknowledgment that their responses held no inherent correctness or incorrectness, thereby further bolstering their confidence in providing assessments. The primary objective of this endeavor was to generate high-quality primary data. Furthermore, the central focus of this investigation centered on individuals who actively engage in conspicuous online consumption within the domain of social media. These individuals constituted the fundamental units of analysis within the study’s overarching conceptual framework.

3.2. Sampling and data collection methods

The population for this study comprised Indonesian consumers aged 17 and above who possess experience in COCB and actively engage with social media. Given the vastness of the population, a non-random sampling method employing the snowball technique was utilized, recognized for its efficiency and effectiveness, particularly when faced with limited resources.

To ensure the questionnaire’s suitability, a preliminary feasibility test was conducted involving 30 students from Bengkulu University through face-to-face interactions. Based on the initial results, certain suggested modifications were incorporated into the questionnaire to enhance its clarity and comprehensibility. Subsequently, a pre-test was carried out with 20 Bengkulu University students, and no further suggestions for improvements were reported. Following these refinements, the questionnaire was distributed online via WhatsApp, resulting in a total of 330 participants in this study. After tabulation, 8 questionnaires were excluded as they provided identical answers to all statements, leaving a sample of 322 for analysis. Further refinement led to the inclusion of 292 samples that met the criteria for validity and reliability. This sample size aligns with the recommendations outlined by Hair et al. (Citation2014).

Regarding the demographics of the respondents (as displayed in Table ), a majority of them (60.6%) were female. Additionally, the largest age group represented was between 17 and 25 years old, constituting 61.3% of the sample. A significant portion of the respondents possessed diplomas and undergraduate degrees (46.6%), indicating that they are a group of productive young adults in the early stages of their careers. In terms of income level, most respondents (60.6%) fell within the lower-middle class category, with earnings ranging from the regional minimum wage of IDR 1,000,000 to IDR 5,000,000 (equivalent to below US$ 333,33). Instagram emerged as the most popular social media platform among respondents (69.5%), followed by Facebook (16.8%). Common activities on these platforms included photo uploading (32.2%), snapgram creation (27.1%), and status updating (24.7%).

Table 1. Characteristics of respondents

3.3. Measurement items

This study follows a confirmatory approach, utilizing measurement items derived from prior research. The materialism items were borrowed from Richins and Dawson (Citation1992), while the items related to narcissism and COCB on social media were adapted from Taylor and Strutton (Citation2016). Responses to these items were evaluated using a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (indicating strong disagreement) to 7 (indicating strong agreement). Detailed information about all measurement items is provided in Appendix 1.

4. Data analysis

4.1. Descriptive analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted by assessing the mean and standard deviation of the three research variables, alongside calculating the kurtosis and skewness values for all measurement items. The findings indicated that the mean and standard deviation values were 5.90 and 0.95 for materialistic orientation, 6.10 and 0.72 for narcissistic behavior, and 5.31 and 1.35 for COCB, respectively. This observation indicates that respondents perceive themselves as individuals characterized by relatively high levels of materialistic orientation, narcissistic behavior, and COCB. Additionally, the skewness values for all measurement items ranged from −1.746 to −0.407, while the kurtosis values ranged from −0.279 to 3.316. Importantly, all these values fall within the acceptable thresholds of > −3 to < 3 for skewness and > −10 to < 10 for kurtosis, thereby confirming that all items conform to the criteria of data normality (Brown, Citation2006).

4.2. Measurement model

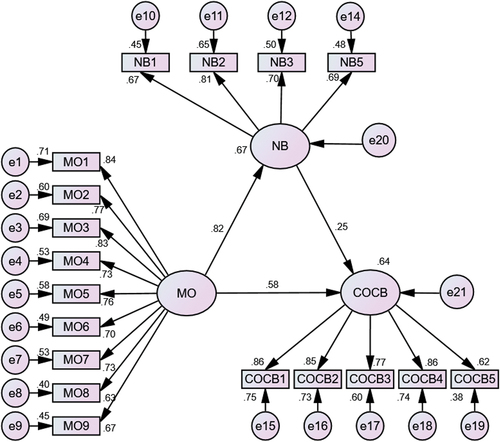

The data analysis for this study was conducted using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with the AMOS software. SEM is a multivariate statistical method that allows for the examination of relationships between constructs simultaneously, providing statistical efficiency. The SEM analysis comprised two stages: the measurement model using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and the testing of the structural model. The measurement model assessment involved evaluating the validity and reliability of the indicators/constructs.

The analysis of the measurement model, based on data from 322 respondents, revealed the following Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values: 0.546 for materialistic orientation, 0.438 for narcissistic behavior, and 0.730 for conspicuous online consumption. According to Hair et al. (Citation2014), the convergent validity requirement is not met if the AVE value of a construct is less than 0.5. To enhance the AVE value, one strategy is to eliminate an indicator with a factor loading value less than 0.5, such as NB4 with a factor loading of 0.388. Additionally, discriminant validity was examined, and the results showed that the square root of the AVE for each construct (on the diagonal) was smaller than the correlation coefficient between that construct and other constructs. Specifically, the square root of the AVE for materialistic orientation (0.739) was lower than the correlation coefficient between materialistic orientation and COCB (0.758), and the square root of the AVE for narcissistic behavior (0.655) was smaller than the correlation coefficient between materialistic orientation and narcissistic behavior (0.688). These results indicate inadequate discriminant validity, following the criteria outlined by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981).

Subsequently, after eliminating 30 questionnaires with low Mahalanobis distance values and the NB4 indicator with a factor loading value of 0.388, the measurement model with a sample size of 292 demonstrated improved performance (as shown in Table ). All research indicators exhibited factor loadings within the range of 0.615–0.864, meeting the criterion for convergent validity. Furthermore, the AVE values for the constructs were satisfactory: 0.552 for materialistic orientation, 0.518 for narcissistic behavior, and 0.638 for COCB on social media, confirming convergent validity. The composite reliability scores for these constructs were also above the minimum criterion of 0.700, with values of 0.917 for materialistic orientation, 0.811 for narcissistic behavior, and 0.897 for COCB. Additionally, Cronbach’s Alpha values for these constructs indicated robust internal consistency, with values of 0.915 for materialistic orientation, 0.806 for narcissistic behavior, and 0.895 for COCB. Furthermore, the measurement model also demonstrated improved results for discriminant validity. All correlation coefficients between pairs of constructs on the left diagonal were smaller than the square root of the AVE values for those constructs, confirming good discriminant validity (as shown in Table ).

Table 2. Measurement model analysis

Table 3. Analysis of discriminant validity

4.3. Structural model and hypothesis testing

After conducting the validity and reliability tests, the structural model was assessed, comprising three constructs: materialistic orientation as an exogenous construct, narcissistic behavior as a mediator construct, and COCB on social media as an endogenous construct. The structural model examined the causality relationships and the mediating role as outlined in the four research.

The data analysis results indicate that the majority of the structural model parameters meet the necessary criteria (χ2 = 371.121; df = 125; ρ < 0.001; χ2/df = 2.969; RMSEA = 0.082; TLI = 0.914, CFI = 0.930; GFI = 0.879; SRMR = 0.057), in line with the guidelines provided by Hair et al. (Citation2014). Overall, the data analysis demonstrated a robust level of fit, with approximately 67.4% of the variance accounted for in narcissistic behavior and 63.9% in COCB on social media.

The results of the proposed hypotheses are presented in Table and Figure . This study confirms that hypothesis 1 is accepted, indicating that materialistic orientation has a positive effect on COCB on social media (β = 0.579, ρ < 0.001). Hypothesis 2 is also supported, confirming the positive impact of materialistic orientation on narcissistic behavior (β = 0.821, ρ < 0.001). Furthermore, hypothesis 3 finds support, as narcissistic behavior has a positive and significant effect on COCB on social media (β = 0.253, ρ < 0.05).

Table 4. Hypothesis testing results

Furthermore, this study investigated the mediating effect of narcissistic behavior between materialistic orientation and COCB on social media. The bootstrapping method was employed with 2000 samples and bias-corrected confidence intervals (BC CI) set at 95% to examine the mediation effect.

The results of the analysis, as shown in Table , indicate an indirect effect of narcissistic behavior (β = 0.208, ρ < 0.05) between materialistic orientation and COCB on social media (MO → NB → COCB). The results pertaining to the mediation effect support the hypothesis, revealing that the relationship between materialistic orientation and COCB on social media is mediated by narcissistic behavior (β = 0.208, ρ < 0.05, BC CI 95% [0.046–0.557]), in accordance with the guidelines outlined by Hair et al. (Citation2014). Therefore, it is confirmed that there exists a significant direct effect between the research constructs as described in hypotheses 1–3, as well as an indirect effect from materialistic orientation to COCB on social media via narcissistic behavior, elucidating the partial mediating role of narcissistic behavior. Consequently, this study affirms that COCB on social media is not solely directly influenced by materialistic orientation but is also indirectly influenced by materialistic orientation through the mediation of narcissistic behavior.

Table 5. Mediation test of narcissistic behavior

5. Discussion and conclusion

This study investigates the effects of materialistic orientation on narcissistic behavior and COCB on social media, as well as the mediating role of narcissistic behavior in the relationship between materialistic orientation and COCB on social media. The key findings are summarized below:

First, materialistic orientation has a positive and significant impact on COCB on social media. This implies that individuals with a strong focus on materialism are motivated to showcase luxury goods on social media as a means of enhancing their self-image. They often attribute their success to the display of their wealth on social platforms. These findings align with previous research, such as Zakaria et al. (Citation2021), who observed that conspicuous consumption patterns are prevalent among materialistic young Malaysians. Additionally, Lee et al. (Citation2021) found that materialistic consumers, particularly those who prefer conspicuous luxury products, tend to have an interdependent self-construal. Their goal is not necessarily to stand out as unique (need-for-uniqueness) but rather to self-monitor and demonstrate their membership status within a group, ultimately enhancing their social image within their social circles.

Second, materialistic orientation also exerts a positive influence on narcissistic behavior. This suggests that materialistic individuals boost their self-esteem by demonstrating their superiority through displays of wealth, striving to stand out as exceptional in society. These findings are consistent with previous research that identifies materialism as a fundamental trait of narcissistic personalities (Velov et al., Citation2014). Materialistic consumers often seek to be perceived as unique by purchasing exclusive products that symbolize their personality (Shrum et al., Citation2013).

Third, narcissistic behavior positively and significantly affects COCB on social media. Individuals with high levels of narcissistic behavior tend to self-promote on social media platforms by showcasing their wealth. However, it is important to note that the products and services they endorse should align with their high social needs. These findings are consistent with previous research, which suggests that highly narcissistic individuals are willing to pay more for limited edition items exclusively designed for elite groups (Neave et al., Citation2020). For narcissistic consumers, purchasing and using such products are seen as highly prestigious strategies to highlight their vibrant lifestyles, attract attention, boost their self-image, and assert their superiority (de Bellis et al., Citation2016).

Fourth, narcissistic behavior mediates the positive relationship between materialistic orientation and COCB on social media. This indicates that COCB on social media is influenced not only directly by materialistic orientation but also indirectly through narcissistic behavior. Materialistic orientation plays a dual role in driving COCB on social media: as a direct antecedent and as an indirect antecedent via narcissistic behavior as a mediator. Specifically, COCB on social media is stimulated not only by consumers’ purchasing power due to their wealth (Khan et al., Citation2022) and the satisfaction of hedonic demands (Husain et al., Citation2022; Jacob et al., Citation2020) but also by their desire to showcase their superiority through their wealth and satisfy their hedonic needs (Loureiro et al., Citation2016).

This study provides a substantial contribution to both the academic and business communities. Firstly, it furnishes robust empirical evidence highlighting the considerable effects of materialistic orientation on narcissistic behavior, materialistic orientation on COCB, and narcissistic behavior on COCB. Furthermore, the findings shed light on the pivotal role performed by narcissistic behavior as a mediating factor in the relationship between materialistic orientation and COCB. Consequently, this study enriches the extant scholarly literature by illuminating the mediating role of narcissistic behavior in the materialistic orientation -COCB nexus. Second, this study places a noteworthy emphasis on the concepts of materialistic orientation, narcissistic behavior, and COCB within the specific context of Indonesian consumers. This contribution holds significance for both the academic and business domains, as it deepens our comprehension of consumer behavior within a distinct cultural milieu. This perspective aligns with the argument advanced by Zakaria et al. (Citation2021), which underscores the critical importance of recognizing that disparities in cultural capital, even within a single culture or country, can give rise to varying degrees of engagement with and appreciation of conspicuous consumption. Consequently, the contextualization of this study within the Indonesian consumer landscape underscores the imperative need for a culturally nuanced approach when seeking to comprehend COCB and formulate effective marketing strategies. Thirdly, materialistic individuals typically exhibit a propensity for actively seeking products that can assist in the realization of their self-identity goals, fortify their self-image, and engender heightened attention and admiration within their social circles. Consequently, in the pursuit of effectively targeting consumers characterized by materialistic tendencies, marketing managers are counseled to craft marketing strategies proficient in strategically positioning their products as symbols of elevated prestige. One actionable approach to achieve this positioning is through the provision of limited-edition product offerings. Such a strategy is anticipated to stimulate materialistic individuals to prominently showcase these high-prestige products on their social media platforms, thereby fostering COCB. Fourthly, in conjunction with the assertive inclination of materialistic and narcissistic consumers to conspicuously display their prestigious possessions on social media platforms, thereby fortifying COCB, marketing managers should proactively administer social media channels to cultivate profound engagements with these consumer segments. Furthermore, the company can facilitate a diverse spectrum of events, such as gatherings, gala dinners, and social activities, serving as avenues for demonstrating their consumers’ journey toward self-actualization. These events should be extensively documented and shared across social media platforms. The anticipated outcome of such exposure and dissemination of these activities is the reinforcement of conspicuous online consumption patterns, which, in turn, holds the potential to not only exert influence and resonate with the company’s own followers but also with the followers of the company’s consumers. Notably, this strategic approach yields inherent benefits for the company, as it garners complimentary endorsements and heightened brand advocacy, all at no additional cost.

This study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, this study employed the snowball sampling technique, which generates constraints concerning the extent to which research findings can be generalized. To enhance the robustness of these findings, it is advised to conduct replication studies utilizing the random sampling technique. Such an approach holds the potential to yield samples that more comprehensively encompass the inherent characteristics of the broader target population. Notably, interpretations drawn from outcomes obtained through random sampling possess the capacity to offer a heightened level of precision (generalizability) when compared to conclusions drawn from non-random sampling techniques, as emphasized by Hair et al. (Citation2014). Second, the study’s conceptual framework is relatively simple, featuring one exogenous, one endogenous, and one mediator construct. Future research should aim for a more intricate model, exploring both internal and external factors influencing COCB on social media. Additionally, investigating the impact of culture, particularly religiosity, on narcissistic behavior and COCB could offer valuable insights. The study’s focus on specific products or categories, such as prestigious electronic devices, branded fashion items, automobiles, and international travel, could enrich the understanding of COCB. Lastly, future research should consider the role of moderating variables, which were not addressed in this study, to provide a more comprehensive perspective on consumer behavior.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Belk, R. W. (1984). Three scales to measure constructs related to materialism: Reliability, validity, and relationships to measures of happiness. Advances in Consumer Research, 11, 291–16.

- Bergman, J. Z., Westerman, J. W., Bergman, S. M., & Daly, J. P. (2013). Narcissism, materialism, and environmental ethics in business students. Journal of Management Education, 38(4), 489–510. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562913488108

- Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Press.

- Burnasheva, R., & Suh, Y. G. (2021). The influence of social media usage, self-image congruity and self-esteem on conspicuous online consumption among millennials. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing & Logistics, 33(5), 1255–1269. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-03-2020-0180

- Campbell, W. K., Rudich, E. A., & Sedikides, C. (2002). Narcissism, self-esteem, and the positivity of self-views: Two portraits of self-love. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(3), 358–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202286007

- de Bellis, E., Sprott, D. E., Herrmann, A., Bierhoff, H.-W., & Rohmann, E. (2016). The influence of trait and state narcissism on the uniqueness of mass-customized products. Journal of Retailing, 92(2), 162–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2015.11.003

- Duan, J., & Dholakia, R. R. (2017). Posting purchases on social media increases happiness: The mediating roles of purchases’ impact on self and interpersonal relationships. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 34(5), 404–413. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-07-2016-1871

- Edgell, S. (1992). Veblen and post‐veblen studies of conspicuous consumption: Social stratification and fashion. International Review of Sociology, 3(3), 205–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.1992.9971128

- Fastoso, F., Bartikowski, B., & Wang, S. (2018). The “little emperor” and the luxury brand: How overt and covert narcissism affect brand loyalty and proneness to buy counterfeits. Psychology & Marketing, 35(7), 522–532. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21103

- Fastoso, F., & González-Jiménez, H. (2020). Materialism, cosmopolitanism, and emotional brand attachment: The roles of ideal self-congruity and perceived brand globalness. Journal of Business Research, 121, 429–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.015

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gierl, H., & Huettl, V. (2010). Are scarce products always more attractive? The interaction of different types of scarcity signals with products’ suitability for conspicuous consumption. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 27(3), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2010.02.002

- Górnik-Durose, M. E., & Pilch, I. (2016). The dual nature of materialism. How personality shapes materialistic value orientation. Journal of Economic Psychology, 57, 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2016.09.008

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

- Husain, R., Ahmad, A., & Khan, B. M. (2022). The impact of brand equity, status consumption, and brand trust on purchase intention of luxury brands. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2034234. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2034234

- Jacob, I., Khanna, M., & Rai, K. A. (2020). Attribution analysis of luxury brands: An investigation into consumer-brand congruence through conspicuous consumption. Journal of Business Research, 116, 597–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.007

- Kapferer, J. N., & Valette-Florence, P. (2019). How self-success drives luxury demand: An integrated model of luxury growth and country comparisons. Journal of Business Research, 102, 273–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.02.002

- Kasser, T., Cohn, S., Kanner, A. D., & Ryan, R. M. (2007). Some costs of the American corporate capitalism: A psychological exploration of value and goal conflicts. Psychological Inquiry, 18(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10478400701386579

- Kenton, W. (2021). Conspicuous consumption. www.investopedia.com/terms/c/conspicuous-consumption.asp#:~:text=Conspicuous%20consumption%20is%20a%20means,apply%20to%20any%20economic%20class

- Khan, S. A., Al Shamsi, I. R., Ghila, T. H., & Anjam, M. (2022). When luxury goes digital: Does digital marketing moderate multi-level luxury values and consumer luxury brand-related behavior? Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2135221. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2135221

- Lee, M., Bae, J., & Koo, D.-M. (2021). The effect of materialism on conspicuous vs inconspicuous luxury consumption: Focused on need for uniqueness, self-monitoring and self-construal. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing & Logistics, 33(3), 869–887. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-12-2019-0689

- Lim, W. M., Phang, C. S. C., & Lim, A. L. (2020). The effects of possession- and social inclusion-defined materialism on consumer behavior toward economical versus luxury product categories, goods versus services product types, and individual versus group marketplace scenarios. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 56, 102158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102158

- Loureiro, S. M. C., Kaufmann, H. R., & Wright, L. T. (2016). Luxury values as drivers for affective commitment: The case of luxury car tribes. Cogent Business & Management, 3(1), 1171192. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2016.1171192

- Masoom, M. R., & Moniruzzaman Sarker, M. (2017). Rising materialism in the developing economy: Assessing materialistic value orientation in contemporary Bangladesh. Cogent Business & Management, 4(1), 1345049. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2017.1345049

- Naderi, I., & Paswan, A. K. (2006). Narcissistic consumers in retail settings. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 33(5), 376–386. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-02-2015-1327

- Nanda, E. (2020). 10 Harga Jam Tangan Mewah Artis Ini Ada yang Mencapai Milliaran! https://www.idntimes.com/hype/entertainment/erfah-nanda-2/harga-jam-tangan-mewah-artis?page=all.

- Neave, L., Tzemou, E., & Fastoso, F. (2020). Seeking attention versus seeking approval: How conspicuous consumption differs between grandiose and vulnerable narcissists. Psychology & Marketing, 37(3), 418–427. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21308

- O’Cass, A., & Frost, H. (2002). Status brands: Examining the effects of non‐product‐related brand associations on status and conspicuous consumption. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 11(2), 67–88. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420210423455

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Qattan, J., & Al Khasawneh, M. (2020). The psychological motivations of online conspicuous consumption: A qualitative study. International Journal of E-Business Research, 16(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJEBR.2020040101

- Richins, M. L. (2004). The material values scale: Measurement properties and development of a short form. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(1), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1086/383436

- Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. (1992). A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1086/209304

- Saenger, C., Thomas, V. L., & Johnson, J. W. (2013). Consumption-focused self-expression word of mouth: A new scale and its role in consumer research. Psychology & Marketing, 30(11), 959–970. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20659

- Sedikides, C., & Hart, C. M. (2022). Narcissism and conspicuous consumption. Current Opinion in Psychology, 46, 101322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101322

- Shane-Simpson, C., Schwartz, A. M., Abi-Habib, R., Tohme, P., & Obeid, R. (2020). I love my selfie! An investigation of overt and covert narcissism to understand selfie-posting behaviors within three geographic communities. Computers in Human Behavior, 104, 106158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106158

- Shrum, L. J., Wong, N., Arif, F., Chugani, S. K., Gunz, A., Lowrey, T. M., Nairn, A., Pandelaere, M., Ross, S. M., Ruvio, A., Scott, K., & Sundie, J. (2013). Reconceptualizing materialism as identity goal pursuits: Functions, processes, and consequences. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 1179–1185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.08.010

- Sundie, J. M., Kenrick, D. T., Griskevicius, V., Tybur, J. M., Vohs, K. D., & Beal, D. J. (2011). Peacocks, porsches, and Thorstein Veblen: Conspicuous consumption as a sexual signaling system. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 100(4), 664–680. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021669

- Taylor, D. G., & Strutton, D. (2016). Does Facebook usage lead to conspicuous consumption? The role of envy, narcissism and self-promotion. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 10(3), 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-01-2015-0009

- Thyroff, A., & Kilbourne, W. E. (2018). Self-enhancement and individual competitiveness as mediators in the materialism/consumer satisfaction relationship. Journal of Business Research, 92, 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.023

- Veblen, T. (1992). The theory of the leisure class (1st ed.). Routledge. http://moglen.law.columbia.edu/LCS/theoryleisureclass.pdf

- Velov, B., Gojković, V., & Đurić, V. (2014). Materialism, narcissism and the attitude towards conspicuous consumption. Psihologija, 47(1), 113–129. https://doi.org/10.2298/PSI1401113V

- Wahab, H. K. A., Tao, M., Tandon, A., Ashfaq, M., & Dhir, A. (2022). Social media celebrities and new world order. What drives purchasing behavior among social media followers? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 68, 103076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103076

- Walker, A. (2023). Inside the home of the Indonesian superstars! - Unmasked vlog #42. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lefLkhUdLTs

- Wink, P. (1991). Two faces of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(4), 590–597. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.590

- Zakaria, N., Wan-Ismail, W.-N. A., & Abdul-Talib, A.-N. (2021). Seriously, conspicuous consumption? The impact of culture, materialism and religiosity on Malaysian generation Y consumers’ purchasing of foreign brands. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing & Logistics, 33(2), 526–560. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-07-2018-0283

- Zhu, C., Su, R., Zhang, X., & Liu, Y. (2021). Relation between narcissism and meaning in life: The role of conspicuous consumption. Heliyon, 7(9), e07885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07885

Appendix 1.

Measurement Items.

Materialistic Orientation (adapted from Richins & Dawson, Citation1992)

I admire people who own expensive things.

The things I own say a lot about how well I’m doing in life.

I like to own things that impress people.

Buying things give me a lot of pleasure.

I like a lot of luxury in my life.

Some of the most important achievements in life include acquiring material possessions.

My life would be better if I owned certain things I don’t have.

I’d be happier if I could afford to buy more things.

It sometimes bothers me quite a bit that I can’t afford to buy all the things I’d like

Narcissistic Behavior (adapted from Taylor & Strutton, Citation2016)

I am an extraordinary person

I think I am a special person

I am more capable than other people

I always know what I am doing

I know that I am good because everybody keeps telling me so

Conspicuous Online Consumption (adapted from Taylor & Strutton, Citation2016)

On social media, I show off things I buy if they are expensive.

I am more likely to highlight my possessions on social media if they have some ‘snob appeal’.

My social media page includes products and brands that are prestigious.

When I buy things, I like to show them off on social media.

I “like” brands on social media because they have status.