Abstract

The purpose of the research was to identify the sources of tensions, the factors that determine their magnitude and the circumstances that influence the management of said tensions in the context of coopetitive interactions between SMEs belonging to the agro-industrial sector of Ecuador. In the study, carried out with a qualitative approach using multiple case studies and grounded theory, 25 cases of companies belonging to the banana, cocoa, shrimp, and flowers subsectors of that country were included, in which 54 executives and 15 management experts participated strategic. The results indicate that the tensions and conflicts that occur in coopetitive relationships derive from unilateral factors associated with the organization, and from multilateral factors associated with the sector or the market. The study highlights the importance of strengthening the ability to manage tensions and conflicts that occur between companies that compete and collaborate simultaneously to increase the perceived value of the customer and the network, even in the presence of conflicts, rivalries, and divergent interests. This implies that interested parties must be able to deploy new inter-business interactions based on trust, mutual respect, and recognition of legitimate interests, with the aim of sharing resources, reducing costs, and taking advantage of new business opportunities. The novelty of the research lies in the fact that it is the first study that addresses, from an empirical perspective, the way in which the coopetitive paradox manifests itself in Ecuadorian SMEs.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This article identifies the sources of tension that occur when two or more companies that are competitors decide to collaborate with each other to take advantage of the resources they have and thus be able to achieve objectives that they could not achieve individually. The factors that influence the way these tensions are managed are also identified, taking as a sample 25 small and medium-sized companies that belong to four agroindustry sectors in Ecuador. The results reveal the complex and multidimensional nature of the phenomenon studied in which cultural and structural factors intervene that are present in the organizations themselves and in the sectors to which they belong. The study highlights the need to strengthen the ability to manage tensions and conflicts that occur between companies that compete and collaborate simultaneously to increase the perceived value of the customer and the network, even in the presence of rivalries and divergent interests.

1. Introduction

Coopetition represents a business strategy aimed at creating value through collaboration and simultaneous competition with competitors to achieve one or more common benefits (Branderburger & Nalebuff, Citation1996), but despite the abundant literature on the phenomenon, there is still no clarity about the complexities and challenges that are present in the value creation process, especially in terms of how companies manage to maintain a balance between cooperation and competition (Hannah & Eisenhardt, Citation2018). This is especially relevant when assuming that the levels of competition and cooperation between companies are not stable (Lascaux, Citation2020) but rather vary over time since they are subject to the power relations between them, and the priority assigned to the establishment of common objectives (Akpinar & Vincze, Citation2016).

The balance between cooperation and competition generates tensions between the creation of value that occurs through cooperation, and the appropriation of value that comes from competition (Ritala & Tidström, Citation2014). For this, the literature proposes two ways of doing it: one way is by separating cooperative actions from those of competition (Bengtsson & Kock, Citation2014), and the other is by integrating cooperative and competitive forces to cover them simultaneously (Gernsheimer et al., Citation2021).

Although these principles of separation and integration have been documented after studies in large companies, according to Virtanen and Kock (Citation2022), putting them into practice is much more difficult in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), even more so if one takes considering that the cultural tradition of this type of companies has been strongly oriented towards competition.

Recent studies have even come to suggest the scant relevance of Coopetition in SMEs that operate in turbulent contexts (Keen et al., Citation2022), which seems to refute the general orientation of the academic literature regarding their high dependence of the direct and indirect relationships that make up the cooperative ecosystem in which they are operating (Levanti et al., Citation2018). However, “despite the significant economic impact of SMEs and their propensity for collaborative strategies, Coopetition in this type of company remains uninvestigated” (Randolph et al., Citation2023, p. 273).

Despite the importance of studying the challenges faced by SMEs as drivers of innovation, growth, and exports (Paul et al., Citation2017), the tensions that arise from the need to create value have received little attention in the literature on coopetition (Ryan-Charleton & Gnyawali, Citation2022) and requires greater empirical research efforts (Le Roy & Czakon, Citation2015). In this sense, this article delves into the understanding of the management of the tensions inherent to coopetition between SMEs that operate in countries with emerging economies, as is the case of Ecuador.

The relevance of the research lies in the fact that no studies have been found that address in depth the complexity of the coopetitive relationships that occur between SMEs in that country, and specifically in the agroindustry sector, which is characterized by great benefits that it provides to the national economy by significantly affecting important macroeconomic variables, such as the Gross Domestic Product and the Economically Active Population (Oñate et al., Citation2021).

The study becomes more relevant if it is also considered that the SMEs that make up this sector are going through a set of financial, commercial, and climatological circumstances, which forces them to establish close collaborative relationships with their own competitors to continue operating in a globalized market. This generates tensions, conflicts and rivalries that threaten the achievement of business objectives and long-term sustainability.

Other elements that were considered to choose the agroindustry sector lie in the fact that, although it is true that this sector is particularly labor-intensive, it also has an important capital component. In addition, one of the main obstacles that must be overcome to reach the foreign market is its inability to satisfy consumer demand in terms of volume, although it has done so in terms of quality (Burgos, Citation2010). This demands a multidimensional effort aimed at strengthening the productive capacities of the sector, consolidating the value chain, and improving the positioning of Ecuadorian agroindustry in international markets.

In view of the above, this article answers the following questions: What are the sources of tensions and conflicts in coopetitive relationships in SMEs of the Ecuadorian agro-industrial sector? What factors determine the magnitude of tensions and conflicts in coopetitive interactions? How tensions and conflicts impact the achievement of the objectives of the Coopetition? What factors act as mediators between tensions and the achievement of the objectives of coopetition? What are the factors that determine the ability to manage the tensions and conflicts that occur in coopetitive relationships? The research is based on the hypothesis that the tensions and conflicts that occur in coopetitive interactions are multidimensional and their magnitude depends on the cultural context in which they occur.

In this way, the article fills an existing gap in the strategic management literature by illuminating the way to manage coopetition in terms of business value creation and joint value creation in the Ecuadorian case, and also, from an empirical perspective, the study contributes to deepening the theoretical understanding of the tensions that arise from coopetition in small and SMEs, which differs from other studies that tend to study coopetitive relationships in larger, strongly consolidated companies.

2. Literature review

2.1. Origins and evolution of the coopetition

The term Coopetition was introduced in the literature by Branderburger and Nalebuff (Citation1996), understanding it as “a value network between competitors, complementary companies, suppliers and customers” (p.177). Conceptually, Coopetition has been understood as “a condition in which we have cooperation and competition at the same time” (Dagnino, Citation2009, p. 3), as the simultaneous and paradoxical compromise between cooperation and competition (Bengtsson & Kock, Citation2014; Chou & Zolkiewski, Citation2018) with the intention to create value (Gnyawali & Ryan-Charleton, Citation2018) and as a strategy that demonstrates the need to cooperate with competitors to achieve success in a market characterized by the complexity of the relationships between the parties (Dziurski, Citation2020), for what is still an intentional strategy, driven by a logic aimed at achieving clearly defined benefits with the right partners (Czakon et al., Citation2020; Darbi & Knott, Citation2023).

More recently, Coopetition has also been understood as a commercial phenomenon that dominates many supply chains and that occurs by equilibrium driven by investment efficiency (Li & Zhao, Citation2022; Riquelme-Medina et al., Citation2022), as well as a form of strategic alliance that require joint learning, collaboration, and exchange of knowledge between organizations (Pan´kowska & Sołtysik-Piorunkiewicz, Citation2022).

A final theoretical approach refers to the knotted paradox of co-competition for sustainability, which arises when competitors cooperate with each other to promote environmental, social, and economic concerns (Manzhynski & Biedenbach, Citation2023)., Table shows the evolution of the concept of Coopetition.

Table 1. Evolution of the concept of Coopetition

In the previous Table it could be observed that co-competitive relationships between companies are created not only to take advantage of resources, but also to create them with a view to the development of new technologies, the joint creation or acquisition of information and knowledge, and for the acquisition of significant capabilities, including capabilities to cooperate (Cygler et al., Citation2018). Therefore, the importance of coopetition seems to be even greater in the context of small and medium-sized companies (Crick et al., Citation2022; Gnyawali & Park, Citation2009).

2.2. Dualities and contradictions

According to Gnyawali et al. (Citation2016), dualities are abstract forces that derive from participation in activities that must be carried out simultaneously even though they are opposite to each other. For their part, the contradictions are specific forces of each entity involved in the Coopetitive paradox, which result from the interactions that occur between individuals with different points of view, forms of reasoning and interests.

The magnitude of the dualities and contradictions will depend on organizational interests, growth and development expectations, organizational cultures, and the economic and financial resources involved in the relationship, which in turn are sources of conflict. According to Yami and Nemeh (Citation2014), the three dimensions that best illustrate Coopetitive dualities are: (a) value creation, as opposed to value appropriation, (b) separation (temporal or spatial) instead of integration and (c) the maintenance of weak links between the actors involved (bridge) as opposed to the search for deep links between them (linkage).

The dualities and contradictions precede the felt tension, which has two interrelated components: (a) the tension experienced by each individual when they feel a certain degree of discomfort or malaise with the paradoxical situation they are facing, and (b) the conflict that is expressed through the interaction between the people involved. For this reason, the literature that addresses the phenomenon of Coopetition assumes that tension is the central object of study, which is easily explained if one considers that tensions are implicit in the very nature of this phenomenon (Bouncken et al., Citation2018; Gnyawali et al., Citation2016; Le Roy & Czakon, Citation2015; Ritala & Tidström, Citation2014; Yami & Nemeh, Citation2014).

2.3. Tensions and coopetitive forces

In the field of Coopetition, tensions refer to the cognitive difficulties experienced by managers when they simultaneously pursue multiple contradictory objectives (Raza-Ullah, Citation2020). It has also been indicated that the tensions that occur in Coopetitive relationships reflect the differences between the coopetitors’ needs in terms of sharing and hiding information, and their willingness to co-create and obtain an appropriate value (Klimas et al., Citation2023). In practice, these differences and contradictions are difficult to manage, even more so in the case of SMEs where decision-making is concentrated in one or a few key people (Virtanen & Kock, Citation2022)

There is no uniformity in the literature on the typology of stresses experienced by managers. For example, Munten et al. (Citation2021) grouped the tensions created by the juxtaposition of contradictory elements into four categories: value generation, temporal articulation, relational evolution, and knowledge circulation. From another perspective, Virtanen and Kock (Citation2022) found three types of tension: (a) tensions due to the overlap of the market and the product; (b) tensions due to proximity to clients and strategic importance; and (c) tensions over congruence of objectives and return prospects.

For their part, Ryan-Charleton and Gnyawali (Citation2022) distinguish only two types of tension in Coopetitive relationships: (1) the tension experienced by Coopetitive partners due to the need to compete and collaborate simultaneously in pursuit of strategic objectives business through reciprocal exchanges; and (2) the tension that occurs in the process of joint value creation, which requires deep commitments and the search for shared objectives.

Lately, a new perspective of tensions has been proposed from a gender perspective, arguing that tensions and demands for co-competition can activate a dilemma mentality or a paradoxical mentality in the intragender dynamics that occur between women in an organizational context (Kark et al., Citation2023).

Gnyawali and Ryan-Charleton (Citation2018) indicated that the separation between the creation of business value and the creation of joint value is what makes it possible to recognize the double paradox that hangs over Coopetitive interactions since, in addition to the contradictory logic that implies competing and collaborating at the same time, there is a contrast between the creation of business value and the creation of joint value. Table shows their most significant differences considering the theoretical contributions of Ryan-Charleton and Gnyawali (Citation2022).

Table 2. Differences between the creation of value for a company and the creation of joint Coopetitive value for both companies

The tensions created by the contradictory logics between the creation of business value and the creation of joint value can be managed by separating the actions of competition and cooperation or by integrating both logics, which would imply having a Coopetitive mentality (Le Roy & Czakon, Citation2015). However, the management of Coopetitive tensions not only depends on the way in which the principles of separation and integration are used but is also subject to the emotional and balance capacities of the Coopetitive partners (Raza-Ullah, Citation2020). This is of particular importance in the context of SMEs whose activities are carried out in a volatile, dynamic environment influenced by global activities (Worimegbe et al., Citation2022).

From the previous points, the hypothesis emerges that the set of tensions and conflicts that arise during coopetitive interactions are multidimensional and are influenced by the cultural context in which they occur.

3. Methodology

From an ontological perspective, the research was framed within constructionism, understood as an interpretation of reality that privileges knowledge, and collective thinking of groups of individuals who live with a phenomenon, for the construction of knowledge (Aparicio & Ostos, Citation2018). The epistemological approach of the study corresponded to interpretativism, following a qualitative approach that allowed us to understand the points of view of the people who live immersed in the Coopetitive phenomenon.

A multiple case study was carried out in 25 companies belonging to the banana, cocoa, shrimp, and flower export sectors of Ecuador, in which 54 in-depth interviews were applied to the same number of executive directors. These companies were selected not because they were representative of a certain population, but because they were “particularly suitable for illustrating and amplifying the relationships and logic between the constructs” (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007, p. 27). The profile of the SMEs participating in the study is shown in Table .

Table 3. Profile of the SMEs participating in the study

In addition, 15 experts in coopetition and business strategies participated, to whom an online questionnaire was applied, made up of open questions, which allowed to broaden the understanding of the testimonies provided by the interviewed managers. The selection of these experts was made according to their suitability, availability, and motivation to participate. The suitability criteria were governed by the following order: (a) researchers with published papers on Coopetition, (b) directors of doctoral programs related to the field of study, and (c) professors of strategic management, business strategy, or equivalent specialization. Table describes the characteristics of the selected experts.

Table 4. Profile of the experts who participated in the research

This data collection process is consistent with the theoretical assumptions of Eisenhardt and Graebner (Citation2007) when they state that, in this type of research, a key aspect is the “use of numerous highly informed informants who see the focal phenomenon from different perspectives”. (p. 28) including organizational actors from different hierarchical levels and functional areas, as well as external observers who, in this case, were replaced by experts.

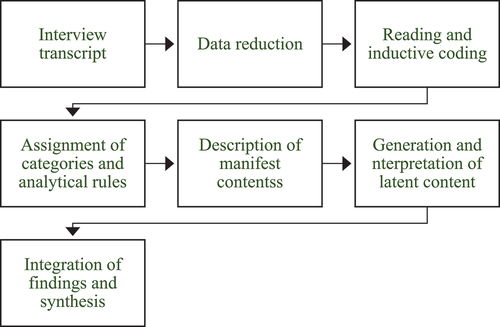

Data were collected until theoretical saturation was obtained; that is, until the information received through the in-depth interviews ceased to provide new relevant data to understand the phenomenon under study. The information obtained was subjected to an open and axial coding process using the constant comparative method. For this, in a first stage and using the Atlas.ti software (v.8) as support, the central content of each interview was analyzed using open coding and the creation of numerous memos, in such a way that it facilitated making sense of the information collected. Then, through the axial coding process, behavior patterns and connections between categories were identified that allowed the creation of conceptual networks. Subsequently, the central categories (selective coding) were identified, which, when related to each other, allowed the generation of an integrating description of the phenomenon studied, which may be subject to verification or validation in future research. Figure shows the coding and analysis process of the content of the interviews carried out.

Data reduction included simplification, ordering and classification of the data, using the constant comparative method with the help of Atlas.ti. With this method, common and divergent narrative incidents that were reflected in the interviews of key informants and experts were identified; This process allowed us to identify the properties of the deductive and emerging categories, explore their interrelationships and generate a substantive theoretical approach that would allow us to understand the coopetitive phenomenon in the SMEs studied and answer the research questions. This theoretical construction should be understood as an “approximation” and not as a formal theory itself. Table shows an example of the interpretive process.

Table 5. Simple example of the data coding and interpretation process

Regarding the criteria that allowed evaluating the quality of the research, those indicated by Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985) regarding credibility, transferability, reliability, and confirmability were used. In this regard, the credibility of the findings is supported by the triangulation of sources, having compared the points of view of the different people belonging to the different business ecosystems that have been considered for the study and, additionally, by contrasting those points of view with the perspectives of strategic management experts.

Regarding the transferability or applicability of knowledge in other contexts, this is of an analytical type since the evidence obtained allowed finding logical relationships and establishing their implications in the empirical field, so the conclusions are only valid in the contexts studied. In any case, the chain of evidence and the findings have been described in sufficient depth to allow the conclusions to be transferred to other situations and business scenarios with similar characteristics.

Regarding reliability, this is guaranteed by the recording and literal transcription of all the data obtained, which made it possible to preserve and recover the speeches and testimonies of the informants, thus making it easier for anyone outside the investigation to have the opportunity to question the methodological process carried out and evaluate the adequacy of the data and the findings obtained.

Finally, with the intention of increasing critical reflexivity, developing complementary interpretations, discovering new dialectical relationships, and reducing subjectivity bias, as Lincoln (1995) inquires, for the qualitative analysis of the data, triangulation of analysts of data was used in such a way that perspectives other than that of the researcher could be considered. To this end, the findings were corroborated by three scholars of cooperative strategies, with no connection to the business networks studied, thus demonstrating compliance with the confirmability criterion. On the other hand, the completeness criterion was met (Zhang & Shaw, Citation2012) since detailed information on the characteristics of the sample was provided together with a complete description of the techniques used to obtain the data and operationalize the constructs used.

Table shows the abbreviations used for the 52 interviewees and the 15 experts, according to the agricultural subsector they represented.

Table 6. Codes used to identify study participants

4. Results

4.1. Characterization of the agro-industrial sectors considered for the study

4.1.1. Banana sector

In this sector, a partial congruence of interests and objectives is perceived between the business actors that make up the production chain and the exporting companies. There is also a clear separation between collaboration and competition, with preeminence of the latter, which configures a network context dominated by a high level of competitiveness (internal and external) and by the presence of divergent interests that could be hindering the achievement of collective benefits.

4.1.2. Cocoa sector

As in the banana sector, in this sector there is also a clear separation between competition and collaboration, with an emphasis on competition and a low level of integration. The willingness to collaborate seems to be inversely proportional to the competitive position, and the possibility of collaborating with competitors is reduced by a lack of trust, zeal, and a lack of transparency in their actions.

4.1.3. Shrimp sector

In the case of the shrimp industry, the results obtained suggest that the ability to collaborate among competitors is subject to the possibility of obtaining immediate benefits, which would allow us to argue that the center of attention is the company, but not the sector to which they belong. As occurs in the banana and cocoa sectors, this lack of integration around a common purpose could be a response to the high level of competition that exists in the shrimp sector, in which private interests seem to prevail over the benefits of the sector.

4.1.4. Flower sector

In the floriculture sector, it was possible to demonstrate the alignment of the higher collective interests with the business interests, which seems to favor collaboration between companies that compete in the same market, appreciating, in addition, that the strategic objectives of the sector are coherent with the strategic objectives of each company, even when their operational interests are different and even generate conflicts between them.

Below, in Table , the main characteristics of the sectors studied in this research are indicated.

Table 7. Characterization of the agro-industrial sectors considered for the study

4.2. Sources of tensions in coopetitive relationships

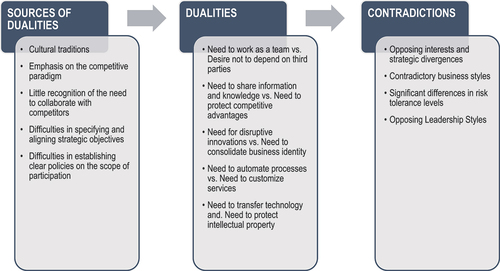

One of the main sources of tension found in the co-coopetitive relationships of the companies that participated in the study was represented by the need to work as a team, but also by the desire not to depend on third parties, which creates even more tension. Significant if the need to share information and knowledge is added, even when the competitive advantages of the company must be protected. (E-1, E-13). Likewise, the need to define who owned the new technology, as well as the need to protect knowledge to maintain competitiveness when the alliance aimed to develop and share joint technologies, was recognized as a major source of tension (C −07). In these circumstances, “a great dilemma is knowing the limit to which information can and should be shared” (C-13). According to the informants, both tensions seem to be influenced by the emphasis on competitiveness and the search for a better position in the market, which can constitute an obstacle to teamwork and collaboration with competitors (C-01 BN- 01, BN-04, BN-15, CC-03, CC-09, SM-08).

Another source of tension emanated from the absence of clear policies on the scope of participation of each company involved in cooperative interactions (C-01, E-03), especially when considering the need to preserve the confidentiality of information, the knowledge and technology (C-03). This may be related to the maturity required to define strategic objectives and act consistently with them (C-05). Other dualities that were recognized as sources of tension were: disruptive innovation versus the consolidation of business identity (E-4, E-12, E-15), process automation versus service customization (E-9, E −14) and, finally, technology transfer versus intellectual property protection (E-1, E-02, E-06, E-10).

As a synthesis, Figure shows the causal relationships between the dualities and contradictions that lead to co-coopetitive tensions, as they have been understood by the managers and experts interviewed.

4.3. Sources of conflict in coopetitive relationships

The conflicts that occur because of the co-coopetitive relationships in the companies studied derive from the conjunction of different perspectives, interests and objectives that lead to contradictory behaviors that are not aligned with the creation of joint value. These contradictions are more noticeable in the case of those companies in which the orientation towards competition predominates. In this regard, the testimonies point to the imposition of prohibitive policies on competitors who, at a given moment and due to market situations, should be recognized as allies. The following testimony exemplifies the contradiction between co-competing partners: “They (the co-competitors) are sometimes part of the tensions and conflicts, due to their imposition of restrictive policies for their competitors and now allies” (E-01).

In fact, with the exception of the floriculture sector where a strategic component of Coopetition was evidenced in the medium and long term (FL-01, FL-11, FL-18), there were abundant references to collaboration between competitors just to satisfy specific needs derived from excess demand, stock management, or pricing, but not as a deliberate development strategy (SM-12, SM-14, BN-03, SM-04, CC-16).

Additionally, conflicts that have arisen because of individualistic positions that come from cultural traditions have been identified. The following testimonies reflect this: “they have their own mentality, and they want to do it their way and that is where conflicts arise between one party and the other party” (BN-03) and “there are always conflicts; there will always be someone to blame” (SM-04). Next, in Figure the main sources of conflicts in the organizations studied are shown in a synthesized manner.

From the testimonies received, it can be inferred that the main source of conflict is found in the predominance of the competitive paradigm that comes from the cultural traditions of company managers, and the experiences obtained through their counterparts in the sector. This belief is based on the desire not to depend on third parties, as well as the emphasis given to the protection of competitive advantages, the confidentiality of information and the search for a better position in the market, even at the expense of competitors. Therefore, the ability to co-operate seems to be subject to two key factors: on the one hand, the influence that the sector itself could exert by encouraging entrepreneurs to collaborate with each other to achieve sectoral benefits that can then be taken advantage of by each company, and on the other hand, the risks. that executives perceive regarding the sustainability of the company in the market. These risks can be perceived from a double perspective:

Risk understood as the consequence of not collaborating with competitors, which can hinder business sustainability due to the impossibility of accessing external resources, developing new capabilities, and taking advantage of business opportunities.

The risk that is implicit in said collaboration due to the need to transfer to competing companies physical, financial, technological or management resources that could threaten the competitive capacity of the company.

From the interviews carried out, indications emerge to consider that the ability to assume such risks is associated with cultural aspects that influence the recognition of the need to cooperate, which in turn is linked to communication factors, joint establishment of objectives and recognition of mutual benefits. Another determining factor in the configuration of the coopetitive capacity of companies is associated with the degree of compatibility they demonstrate with each other. On this topic, in the absence of new corroborating studies, cultural traditions and especially managerial behaviors that emphasize the competitive paradigm seem to have the capacity to inhibit coopetitive interactions. Thus, a company that wishes to promote coopetitive relationships will encounter opposition if the other party is reluctant to work as a team, share information or transfer knowledge, or if it perceives a certain degree of self-sufficiency to climb strategic leadership positions in the sector with which it can take advantage specific market circumstances.

Consistent with the above, the factors that are interpreted as determinants of the coopetitive capacity of small and medium-sized companies in the Ecuadorian agro-industrial sector can be summarized as: cultural compatibility between companies, the influence of the sector, the potential advantages and risks that arise. perceive, the size of the value created and shared, and the demands imposed by the market in which they compete.

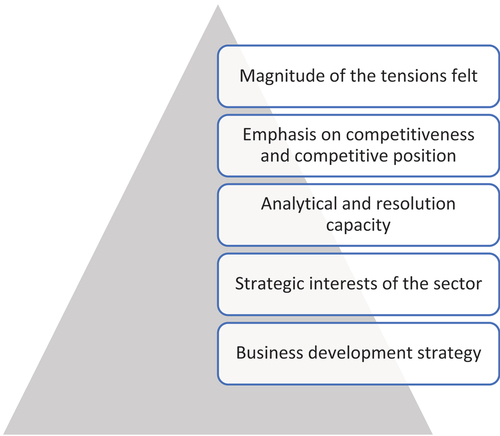

4.4. Determinants of the magnitude of tensions and conflicts deriving from the coopetitive paradox

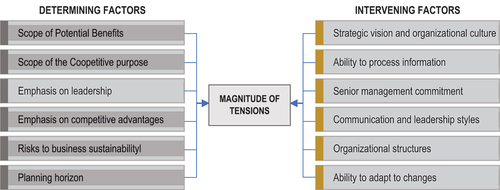

Regarding the intensity with which tensions and conflicts are perceived, managers understand that this depends on the scope of the purpose and the Coopetitive dynamics (E-8), the company’s ability to process the information received (BN- 10, CC-02, CC-06), the ability to retrieve and share the information requested or required by the other company (CC-11, SM-04, SM-07, FL-06), the degree of commitment within the senior management of the companies immersed in the Coopetition process (FL01, FL-02, Fl-09) and, finally, the perception of the advantages obtained by each of them (BN-05, BN-11, CC −08, FL-03, FL-08). The latter is of particular interest since an imbalance in the benefits obtained can be the seed of new tensions and conflicts that could even endanger the Coopetitive relationship (E-13).

Another element that seems to determine the magnitude of tensions and conflicts is represented by individualistic behavior and the consequent perception of a greater risk to the sustainability of the company in the sector (BN-03, BN-07, BN-08, BN- 15, CC-03, CC-09, SM-04 and SM-08). In the same way, trust, assumed commitments, shared knowledge, balance in terms of perceived benefits and transparency in management are factors that have been highlighted as triggers of tensions and conflicts in cooperative relations (C-14, BN-02, BN-06, BN-13, CC-10, SM-01, FL-09).

Regarding the level of organizational formalization, it was argued that the more formal the organization, the fewer the conflicts since the interaction will be carried out strictly in accordance with the established procedures (E-14). Another aspect of special interest lies in the propensity shown by managers to think more about short-term benefits than about their long-term development (E-07, BN-01, BN-04, BN −12, CC-04, CC-09, CC-13, SM-06, FL-01, FL-05), which again highlights the role of cultural values and strategic thinking in joint value creation.

The analysis of the testimonies provided by the interviewees allows us to infer that the magnitude of the tensions is subject, on the one hand, to the scope of the purpose and the Coopetitive dynamic, and on the other, to the recognition of the difficulties in occupying or maintaining positions of leadership in the sector, since the objectives are mainly aimed at maintaining the competitive position and the sustainability of operations (E-8).

Other factors that affect the magnitude of tensions and conflicts are: (a) the company’s ability to process the information received and share the information requested by the other company; (b) the degree of commitment of the companies involved in the Coopetition process, (c) the perception of the advantages obtained by each of the Coopetition companies, and (d) the manifestation of individualistic behavior with the consequent perception of a greater risk to business sustainability, which could generate a climate of unease and uncertainty among the co-competing partners.

Regarding the level of organizational formalization, it is argued that the more formal the organization is, the fewer the conflicts will be since the interaction will only be carried out strictly as established in the procedures (E-13b). Likewise, from the point of view of the interviewees, the factors that determine the magnitude of the dualities and contradictions find correspondence with the type of personality, leadership qualities, business vision, ambition for results and the ability to adapt to changes.

Figure shows the factors that influence the magnitude of tensions and conflicts according to the informants consulted.

4.5. Impact of tensions and conflicts on the achievement of the objectives of the coopetition

From the testimonies received, it is evident that the felt tensions attributed to Coopetition relations directly influence the results of the organization. This is highlighted by the greater commitment to innovation, the search for solutions to market challenges and overcoming routines that do not contribute to value creation (FL-01; FL-03). In fact, it has been claimed that Coopetition opens the doors not only to exchange existing resources, but also to obtain external resources that would not otherwise be possible (Fl-01).

The tensions that arise because of the manifestations of mistrust between individuals can hinder the search for synergies and assertive decision-making (BN-06, BN07, SM-04). In this sense, the negative effect of mistrust on co-competitive performance seems to be associated with the interest in achieving dominant positions in the sector (CC-05, CC-10) and not so much with other factors of a competitive nature, since that the high level of competition in a certain sector of activity is not an obstacle to creating the conditions that promote understanding and cooperation between companies in search of collective benefits and common objectives in terms of social andCitation2021Citation2015 environmental management and cost reduction (FL- 02, FL-03). Figure show positive and negative impacts of tensions and conflicts for the achievement of coopetitive objectives.

4.6. Factors that influence the mediation between tensions and the achievement of objectives

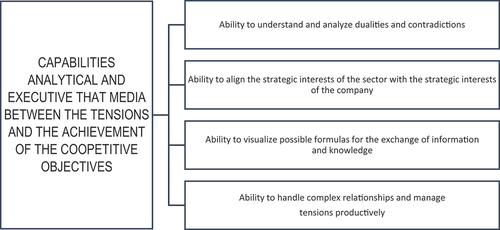

Due to the complexity implicit in the Coopetitive paradox, the way to manage Coopetitive interactions seems to be determined, initially, by the ability to understand and analyze the dualities and contradictions together with their possible implications in terms of discovering new opportunities to act competitively, evaluate critical factors and act accordingly. Thus, the ability to align the strategic interests of the sector with the strategic interests of each company will depend on the analytical skills to foresee the favorable results of this alignment, even when the operational interests of each company are different (BN-08, SM-04, FL-01 and FL-04). The same occurs with the ability to visualize possible formulas for the exchange of information and knowledge between competitors, which do not jeopardize the competitive potential of the company (CC-02; FL-04).

The findings reveal that the greater the ability to perceive a co-competitive relationship, the easier it will be to identify effective processes to manage tensions. This became evident in the different aspects of Coopetitive practices in the flower sector (FL-01; FL-02; FL-04) and in the reasons that promote collaboration between competitors (BN-03; BN-07; CC-02; SM-04; FL-1; FL-03; FL-04). Therefore, the greater the company’s cognitive ability to understand and analyze the paradoxical situation, the greater its ability to execute routines, combine them, refine them, and implement new ways of managing cooperative relationships.

As with the analytical capacity, the execution capacities were also appreciated as essential for cooperative performance. In this regard, the execution capacity is demonstrated by the efficiency with which each Coopetitive relationship is managed for the joint creation of value based on the objectives of the Coopetition, mainly in terms of technology and market value (CC- 02; FL01; FL-03).

As a summary, Figure shows the cognitive and executive capacities that mediate between stress and the achievement of objectives.

4.7. Factors influencing the ability to manage coopetitive tensions and conflicts

The results obtained allow us to infer that the management of tensions and conflicts is influenced by the learning capacity, the commitment shown by management, the leadership style and the organizational structures of the companies involved, and the willingness shown by the actors involved in the network or sector to plan sectoral development objectives that allow it to evolve in a single direction.

Figure highlights the most significant factors that influence the ability to manage tensions and conflicts in Coopetitive interactions.

4.8. The coopetitive paradox

Regarding the formation of paradoxical situations, the findings reveal that these are always subject to the Coopetitive capacity of the company, which depends on unilateral factors associated with the organization, and with multilateral factors associated with the sector or the market (Table ). The recognition of coopetitive paradoxes is determined, initially, by the ability to understand and analyze dualities and contradictions together with their possible implications. Thus, the ability to align the strategic interests of the sector with those of the company will depend on the analytical skills to foresee the favorable results of this alignment, even when the operational interests of each company are different (BN-08, SM-04, FL −01 and FL-04). The same occurs with the ability to visualize possible formulas for the exchange of information and knowledge between co-competing partners that do not jeopardize the competitive potential of the company (CC-02; FL-04).

Table 8. Factors determining the ability to manage the Coopetitive paradox

5. Discussion

As a summary, Table shows the most relevant findings derived from the study of Coopetitive interactions between the SMEs studied, grouping them by areas of interest according to the purposes of study.

Table 9. Sources of stresses, determinants of the magnitude of stresses, and circumstances influencing the ability to manage Coopetitive stresses

The findings allow us to infer that the main source of co-competitive tensions is the predominance of the competitive paradigm, manifested by the desire not to depend on third parties, the emphasis on the protection of competitive advantages, the confidentiality of information and the search for a better position in the market, even at the expense of competitors. Therefore, the capacity for Coopetition seems to be subject to two key factors: (a) the influence that the sector itself can exert by encouraging businessmen to collaborate among competitors to achieve sectoral benefits that can later be taken advantage of by each company, and (b) the risks that executives perceive regarding the company’s sustainability in the market.

The implications of these findings can be summarized as follows: strategic difficulties in exchanging knowledge, resources, and opportunities with other companies in the sector, which limits the potential for joint growth and development; limited capacity for innovation, hindering adaptation to market changes and resulting in missed opportunities for growth and continuous improvement. Furthermore, the predominance of a competitive focus may encourage the emergence of rivalries and conflicts among companies, creating a tense and hostile business environment that can undermine the sustainability of SMEs, which are inherently more vulnerable to the demands imposed by international markets.

These circumstances reduce the ability to create shared value, as proposed by Ryan-Charleton and Gnyawali (Citation2022) and increase the difficulty of managing differences and contradictions that arise when there is a need to collaborate with competitors, especially when strategic decisions in these types of companies are made by one or a few key individuals (Virtanen & Kock, Citation2022).

Another determining factor of the Coopetitive capacity is associated with the degree of compatibility that the companies show among themselves; In this regard, the lack of trust, the risks assumed and the cultural gaps are factors that influence Coopetitive tensions, which are significantly influenced by the purpose, the planning horizon, the perceived benefits and potential risks, the capacity of learning, the commitment shown by senior management, the leadership style and the structures of the organizations involved in co-competitive interactions.

Furthermore, the results obtained allow us to affirm that the persistence of cultural traditions in small and medium-sized enterprises is conditioning the way coopetitive tensions are perceived and managed. This is not so much due to how managers conceive the principles of separation and integration, but rather due to the emotions that arise around the coopetitive phenomenon. Except for the floriculture sector, we observe a predominance of mutual distrust and a lack of understanding regarding common objectives that transcend specific issues arising from business activities.

In another order of ideas, and alluding to the limitations of the research, the authors declare that the reported findings correspond to small and medium-sized companies that are not necessarily representative of this type of companies in Ecuador. For this reason, the results cannot be extrapolated to other business populations, even with the same characteristics in terms of business volume or type of activity.

It is also important to highlight that the data used in this research was collected in a context of global health crisis due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which conditioned business dynamics and, therefore, could influence the testimonies of those interviewed when emphasize competitiveness as a business paradigm. In this sense, the external validation of the research can only be determined by the coherence with the results obtained when studying them in a previously normalized business ecosystem.

6. Conclusions

In response to the questions mentioned in the introduction of this article, the research found that the main sources of tension in co-competitive relationships between MYPEs are: (a) influence of the sector, (b) perceived potential advantages, (c) perceived risks, (d) cultural compatibility of executives, (e) size of the value created and shared, and (f) the demands of the market where they compete. On the other hand, it was found that the sources of conflicts are: (a) the influence exerted by the sector, (b) the advantages that are perceived, (c) the risks that are seen, (d) the cultural compatibility that exists between the companies that co-opt, (e) the size of the value created and shared, and (f) the demands of the market in which they compete.

It was also found that the determinants of the magnitude of such tensions are: (a) the scope and potential benefits of the cooperative purpose, (b) the company’s emphasis on maintaining competitive advantages and preserving its leadership in the sector and (c) the perceived risks to sustainability, being influenced by: (a) the strategic vision and organizational culture, (b) the ability to process and share information, (c) the commitment shown by senior management to promote and maintain coopetitives interactions, (d) communication and leadership styles, (e) the structural design of organizations and (f) the ability of managers to adapt to change.

In another order of ideas, the results of the study allow us to affirm that the analytical and executive capacities of managers act as mediators between tensions and the achievement of objectives. In this regard, among the analytical capacities, the following stand out for their importance: (a) the capacity that the company possesses to understand and analyze the dualities and contradictions that make up the paradoxical relationships, (b) the capacity that it has so that the strategic interests of the company are consistent with the strategic interests of the sector to which it belongs, and (c) the ability to visualize possible formulas that allow the exchange of information and knowledge between coopetitors companies. On the other hand, executive capacities refer to the management of complex relationships and the management of tensions in a productive manner.

Regarding the factors that influence the ability to manage Coopetitive tensions, the following stand out: (a) the magnitude of the perceived tensions; (b) the emphasis on the competitive paradigm, which reduces the ability to visualize the common goals of Coopetition; (c) the development strategy of the industrial sector; (d) the emphasis on innovation; and (e) hierarchical positions, which influence (directly or indirectly) the ability to perceive and manage the tensions that occur as a consequence of Coopetitive interactions.

Lastly, regarding the Coopetitive paradoxes, the findings reveal the influence of factors that are not only internal to each organization but are also affected by factors that derive from the sector and the market in which the companies operate. Among the internal or unilateral factors that determine the ability to manage the Coopetitive paradox, the following stand out; (a) the effectiveness of communication, (b) the ability to make decisions, (c) the coherence between the perceived benefits and the committed resources, (d) the commitment of senior management and (e) the leadership capacity. From an external perspective, among the factors that intervene in the management of the paradox, the following stand out: (a) the trust between the partners that co-opt, (b) the joint establishment of common objectives, goals, and mechanisms for the resolution of conflicts (c) transparency in the contractual relationship, and (d) strengthening the culture of cooperation between companies that compete in the same market.

In this way, the research findings offer insights into the joint creation of value for small and medium-sized companies in four important industries in the primary sector of the Ecuadorian economy, which have been experiencing significant fluctuations in their productive capacity and a reduction in costs profitability margins, fundamentally caused by distortions in international markets, and by the intensity of competition to occupy leadership positions in the respective sectors, which not only reduces the ability to take advantage of growth and development opportunities, but also threatens against the sustainability of the industry.

Based on these results and considering, on the one hand, the emphasis on the competitive paradigm that was expressed by the interviewees, and on the other, the reluctance to share information and other resources with competing companies, an opportunity arises to promote new studies that answer the following questions: how to transcend the classic management paradigms in SMEs in such a way that they allow adopting a new type of strategic reasoning that promotes simultaneity between the competition and collaboration? What are the factors involved in the decision to share information, technology, and resources in a collaborative relationship with competitors?

Finally, considering the limitations of the research, it is recommended to replicate this study in broader and more diverse sectoral contexts to validate the findings about the sources of tension and the way to manage it. In the same way, to overcome the implicit limitations in any cross-sectional study, it is suggested to carry out longitudinal investigations that cover all the phases of the coopetitive phenomenon, from the establishment of agreements and determination of common objectives to the evaluation of the results and the process. In this way it will be easier to obtain information about the cultural dynamics that operate in the coopetitive companies, the type of tensions that are perceived, and the way in which people manage the conflicts that arise. New insights emerging from these studies will help consolidate the theory of the Coopetitive paradox which remains disjointed and highly fragmented.

In any case, from a practical point of view and considering that business contexts are increasingly complex, dynamic and demanding, it is recommended that the competitive paradigm, which currently continues to dominate the business strategy of small and medium-sized companies in the Ecuadorian agricultural industry, begins to be replaced by a new model based on trust, which allows increasing the intensity and performance of coopetitive relationships, in such a way that they can create new business opportunities, maintain their independence, enhance the export desire and consolidate a organizational culture oriented towards innovation and penetration into new sectors of the global market.

Author contributions

The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

About The Author.docx

Download MS Word (13 KB)Public Interest Statement.docx

Download MS Word (12.5 KB)Data availability statement

The data used in this research is available upon request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2287270

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jimmy Gabriel Díaz-Cueva

Jimmy Gabriel Díaz Cueva graduated as an engineer in International Trade with an outstanding track record of success in the field of internationalization of companies and international business. With more than a decade of experience, he has specialized in topics related to international trade and keeps himself constantly updated by attending personal and professional training sessions to learn and show the latest trends and advances in the field. He has shared his knowledge and experience in conferences held in various international trade forums, where he has been able to advise and inspire businessmen and entrepreneurs. In addition, Jimmy Diaz is dedicated to providing training courses on foreign trade, export business plans, international transportation and other essential aspects of international trade. His ability to transmit in a clear and didactic way the knowledge acquired throughout his career, makes his courses a valuable tool for those interested in entering the world of international trade.

References

- Akpinar, M., & Vincze, Z. (2016). The dynamics of coopetition: A stakeholder view of the German automotive industry. Industrial Marketing, 57, 53–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.05.006

- Aparicio, O., & Ostos, O. (2018). El constructivismo y el construccionismo. Revista Interamericana de Investigación, Educación y Pedagogía, 11(2), 115–120. https://doi.org/10.15332/s1657-107X.2018.0002.05

- Bengtsson, M., & Kock, S. (2014). Coopetition—quo vadis? past accomplishments and future challenges. Industrial Marketing, 43(2), 180–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2014.02.015

- Bouncken, R., Fredrich, V., Ritala, P., & Kraus, S. (2018). Coopetition in new product development alliances: Advantages and tensions for incremental and radical innovation. British Journal of Management, 29(3), 391–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12213

- Bouncken, R. B., Gast, J., Kraus, S., & Bogers, M. (2015). Coopetition: A systematic review, synthesis, and future research directions. Review of Managerial Science, 9(3), 577–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-015-0168-6

- Branderburger, A., & Nalebuff, B. (1996). Co-opetition: A revolution mindset that combines competition and cooperation. Doubleday.

- Burgos, S. (2010). La Agroindustria en el Ecuador: Algunos datos para el análisis. In H. Jácome (Eds.), Boletin Mensual de Análisis Sectorial de MIPYMES Nº (Vol. 3, Flacso-Mipro5-11). https://flacso.edu.ec/ciepymes/media/boletines/03.pdf

- Chou, H., & Zolkiewski, J. (2018). Coopetition and value creation and appropriation: The role of interdependencies, tensions and harmony. Industrial Marketing, 70, 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.08.014

- Crick, J., Crick, D., & Chaudhryc, S. (2022). The dark-side of coopetition: It’s not what you say, but the way that you do it. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 30(1), 22–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2019.1642936

- Cygler, J., Gajdzik, B. & Sroka, W.(2014). Coopetition as a development stimulator of enterprises in the networked steel sector. Metalurgija, 53(3), 383–386.

- Cygler, J., Sroka, W., Solesvik, M., & Debkowska, K. (2018). Benefits and drawbacks of Coopetition: The roles of scope and durability in Coopetitive relationships. Sustainability, 10(8), 2688. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082688

- Czakon, W., Gnyawali, D., Le Roy, F., & Srivastava, M. K. (2020). Coopetition strategies: Critical issues and research directions. Long Range Planning, 53(1), 101948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2019.101948

- Dagnino, G. (2009). Coopetition strategy: A new kind of interfirm dynamics for value creation. In G. Dagnino & E. R (Eds.), Coopetition strategy: Theory experiments and cases (pp. págs. 25–43). Routledge.

- Darbi, W., & Knott, P. (2023). Coopetition strategy as naturalised practice in a cluster of informal businesses. International Small Business Journal, 41(1), 88–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/02662426221079728

- Dziurski, P. (2020). Interplay between coopetition and innovation: Systematic literature review. Organization & Management, 1, 9–20. Obtenido de. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Patryk-Dziurski/publication/340655851_Interplay_between_coopetition_and_innovation_Systematic_literature_review/links/5e9736a8a6fdcca7891c0cff/Interplay-between-coopetition-and-innovation-Systematic-literature-review.p

- Eisenhardt, K., & Graebner, M. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2007.24160888

- Gernsheimer, O., Kanbach, D., & Gast, J. (2021). Coopetition research – a systematic literature review on recent accomplishments and trajectories. Industrial Marketing, 96, 113–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2021.05.001

- Gnyawali, D., Madhavan, R., He, J., & Bengtsson, M. (2016). The competition–cooperation paradox in inter-firm relationships: A conceptual framework. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.11.014

- Gnyawali, D., & Park, R. (2009). Co‐opetition and Technological Innovation in Small and Medium‐Sized Enterprises: A Multilevel Conceptual Model. Journal of Small Business Management, 47(3), 308–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2009.00273.x

- Gnyawali, D. R., & Ryan-Charleton, T. (2018). Nuances in the interplay of competition and cooperation: Towards a theory of coopetition. Journal of Management, 44(7), 2511–2534. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318788945

- Hani, M., & Dagnino, G. (2021). Global network coopetition, firm innovation and value creation. JBIM, 36(11), 1962–1974. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-05-2019-0268

- Hannah, D., & Eisenhardt, K. (2018). How firms navigate cooperation and competition in nascent ecosystems. Strategic Management, 39(12), 3163–3192. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2750

- Kark, R., Yacobovitz, N., Segal-Caspi, L., & Kalker-Zimmerman, S. (2023). Catty, bitchy, queen bee or sister? A review of competition among women in organizations from a paradoxical-coopetition perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2691

- Keen, C., Lescop, D., & Sánchez-Famoso, V. (2022). Does coopetition support SMEs in turbulent contexts? Economics Letters, 218, 110762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2022.110762

- Klimas, P., Sachpazidu, K., & Stańczyk, S. (2023). The attributes of coopetitive relationships: What do we know and not know about them? European Management Journal, ahead-of-print https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2023.02.005

- Lascaux, A. (2020). Coopetition and trust: What we know, where to go next. Industrial Marketing, 84, 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.05.015

- Le Roy, F., & Czakon, W. (2015). Managing coopetition: The missing link between strategy and performance. Industrial Marketing, 53, 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.11.005

- Levanti, G., Minà, A., & Picone, P. (2018). La gestione delle relazioni coopetitive quale “fattore abilitante” la crescita delle PMI. In E. R. Ferrari, & Poselli, M. (Eds.), Percorsi di ricerca sui processi di creazione e diffusione del valore nelle PMI. Un approccio multidisciplinare (pp. 113–142). G. Giappichelli Editore.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE Publications.

- Li, W., & Zhao, X. (2022). Competition or coopetition? Equilibrium analysis in the presence of process improvement. European Journal of Operational Research, 297(1), 180–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2021.04.031

- Manzhynski, S., & Biedenbach, G. (2023). The knotted paradox of coopetition for sustainability: Investigating the interplay between core paradox properties. Industrial Marketing Management, 110, 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2023.02.013

- Munten, P., Vanhamme, J., Maon, F., Swaen, V., & Lindgreen, A. (2021). Addressing tensions in coopetition for sustainable innovation: Insights from the automotive industry. Journal of Business Research, 136, 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.07.020

- Niemczyk, J., & Stańczyk-Hugiet, E. (2014). Cooperative and competitive relationships in high education sector in Poland. Journal of Economics and Management, 17, 5–23.

- Okura, M. (2007). Coopetitive Strategies of Japanese Insurance Firms a game-theory approach. International Studies of Management and Organization, 37(2), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.2753/IMO0020-8825370203

- Oñate, J. A., Flores, X. F., & Ordoñez, J. E. (2021). Identificación de sectores agroindustriales alimenticios en el Ecuador que han sido afectados por la pandemia COVID-19. Recimundo, 5(4), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.26820/recimundo/5.(4).oct.2021.65-73

- Pan´kowska, M., & Sołtysik-Piorunkiewicz, A. (2022). ICT supported urban sustainability by example of Silesian metropolis. Sustainability, 14(3), 1586. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031586

- Paul, J., Parthasarathy, S., & Gupta, P. (2017). Exporting challenges of SMEs: A review and future research agenda. Journal of World Business, 52(3), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2017.01.003

- Randolph, R., Fang, H., Memili, E., Ramadani, V., & Nayır, D. (2023). The role of strategic motivations and mutual dependence on partner selection in SME coopetition. International Journal of Entrepreneurship & Small Business, 48(3), 273–295. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2023.129292

- Raza-Ullah, T. (2020). Experiencing the paradox of coopetition: A moderated mediation framework explaining the paradoxical tension–performance relationship. Long Range Planning, 53(1), 101863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2018.12.003

- Riquelme-Medina, M., Stevenson, M., Barrales-Molina, V., & Llorens-Montes, F. (2022). Coopetition in business ecosystems: The key role of absorptive capacity and supply chain agility. Journal of Business Research, 146, 464–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.03.071

- Ritala, P., & Tidström, A. (2014). Untangling the value-creation and value-appropriation elements of coopetition strategy: A longitudinal analysis on the firm and relational levels. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 30(4), 498–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2014.05.002

- Ryan-Charleton, T., & Gnyawali, D. R. (2022). Value creation tension in coopetition: Virtuous cycles and vicious cycles. Strategic Management Review, 2021(1), 1–34. Obtenido de. https://www.strategicmanagementreview.net/articles.html

- Virtanen, H., & Kock, S. (2022). Striking the right balance in tension management. The case of coopetition in small- and medium-sized firms. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 37(13), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-10-2021-0469

- Worimegbe, P. M., Abosede, A. J., & Eze, B. (2022). Coopetition and micro, small and medium enterprises performance. Independent Journal of Management & Production, 13(2), 771–790. Obtenido de. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/8637670.pdf

- Yami, S., & Nemeh, A. (2014). Organizing coopetition for innovation: The case of wireless telecommunication sector in Europe. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2013.11.006

- Zhang, A., & Shaw, J. D. (2012). Publishing in AMJ–part 5: Crafting the methods and results. The Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.4001