?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Organizational change is an inherent challenge that necessitates effective and appropriate management. The presence of human resources plays a pivotal role in the success of organizational change inside a business. Adapting and embracing change is crucial in effectively navigating and managing any change process. The present study examines the impact of psychological capital, perceived organizational support, and work engagement on predicting lecturer readiness to change. A convenience sampling method was employed to select 342 lecturers from private universities in Indonesia for this research. The data processing method uses SEM AMOS. The study results prove that psychological capital, organizational support, and work engagement can increase readiness to change. Then, work engagement can mediate the effect of psychological capital and organizational support on readiness to change. This research provides theoretical implications that work engagement can be an intermediary in increasing readiness for change, which is rarely studied. Furthermore, this study provides managerial implications and recommendations for further research.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Global competition and ever-evolving market demands encourage universities to adapt by adopting more effective technology, strategies and learning methods. As agents of change, lecturers must be ready to change, allowing for increased innovation in teaching, research and community service activities. This study explores what factors can increase readiness to change lecturers. Individual factors such as psychological capital and work engagement increase readiness to change lecturers. In addition, organizational support is also considered to impact increasing readiness to change lecturers. This research is interesting because it focuses on readiness to change as the key to maintaining the relevance, quality, and role of private universities in Indonesia in facing continuous changes in education and society.

1. Introduction

The issue of organizational change and development has been frequently studied mainly due to technological advances, global market policies, organizational environment, and government regulations. Change or transformation is a major problem for organizations because organizational changes can affect the vision, mission, objectives, strategy, and organizational structure and dramatically impact human resources (Kachian et al., Citation2018). Readiness to change can help modern organizational management become more open to innovation and new ideas. Employees are encouraged to develop innovative ideas to improve organizational processes, products, and services. By being ready for change, an organization can better adapt to changes caused by changing customer behavior, technological advances, economic shifts, and other changes occurring in the external environment. Organizations must comprehensively understand organizational change, ensuring that many important components are not overlooked, such as process change, structural modification, innovation, and adaptation (Heracleous & Bartunek, Citation2020).

Digital transformation requires fundamental changes in an organization’s mindset, business procedures, and operating model. Without the necessary preparation, digital transformation risks failure. Organizations that are always ready to change and adapt can survive in the long term because they can adapt to changes in their business environment. Therefore, being prepared to change is the key to a company’s growth and development. It is now an important component in contemporary organizational management. The inability of the management to recognize the comprehensive effects of organizational change at various levels has resulted in a high frequency of failed attempts. It can largely be attributed to the lack of fit between the goals, change agents, recipients, and chosen organizational change paths (Keyser De et al., Citation2019).

The attitude of readiness to change and openness to change are the same because they are analogous to Lewin’s theory in 1951 on the stages of unfreezing and creating readiness to change. According to Burnes (Citation2020), the first step involves “unfreezing” which requires resetting and disturbing the existing balance to begin the change process. The concept of “moving” suggests that there are influential forces supporting change that can initiate and drive change forward. Human resources are the main factor in the organization for the success of an organizational transformation (Nicolás-Agustín et al., Citation2022). In tertiary institutions, the human resources determining change’s success are lecturers. Individuals who will take personal responsibility as agents of change must have an attitude of effective adaptation to changing conditions and proactive anticipation of new challenges. Adapting quickly to new circumstances and being ready to change is critical to successfully dealing with any change (Arnéguy et al., Citation2020; Gigliotti et al., Citation2019).

The global issue stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted several institutions, including universities. They change strategies, mindsets, and ways of working to adapt in times of crisis (Novitasari & Goestjahjanti, Citation2020) and implement changes often called the new normal life. Organizational change is a ubiquitous phenomenon observed in several industrial sectors. Commercial organizations and the education industry, namely universities, also experience the same dynamics (Erlyani & Suhariadi, Citation2022). The world of education is constantly changing because new learning methods and technologies are always emerging. Readiness for change makes lecturers continue to learn and develop. This attitude helps them improve their teaching skills, update their subject knowledge, and become better lecturers. In addition, the current generation of students is very different from previous generations in terms of learning styles, interests, and educational expectations. Lecturers need to adapt their teaching to remain relevant. Universities/colleges where lecturers teach will also continue to change and innovate. Without readiness to change, lecturers can fall behind in institutional policies and vision. However, any of these changes will cause two opposite things in practice. The attitude is in the form of pro with change or con with change. In reality, acceptance of organizational change cannot happen quickly or effortlessly through change programs, so managing people is the main focus of change management. A pro-change mindset is evidenced by a willingness to work with and support the transition. Rejection is indicated by negative views, giving unnecessary advice, and blatantly rejecting any change (Angkawijaya et al., Citation2018; Meria et al., Citation2022).

Readiness must be considered because change will bring up new things and ways of working that may be more challenging. In theory and previous research, psychological capital (PsyCap) reflects the close relationship between attitudes and behavior (Nwanzu & Babalola, Citation2019). PsyCap supports behavior for change. Individuals with high PsyCap will accept change as a challenge that can encourage personal strength and growth, thereby triggering a positive emotional response to change (Liu, Citation2021). Individual reactions to change are influenced by psychological resources and organizational environment perceptions (Kirrane et al., Citation2017). Lecturers with good PsyCap will be more confident in teaching, research, and community service. Increasing the PsyCap factor will significantly increase readiness for change in teaching (Kartika et al., Citation2021; Munawaroh et al., Citation2021). Individuals who have positive feelings about overcoming challenges will be more adaptable to change, able to work simultaneously, and try to succeed by completing tasks well (Ramdhani & Desiana, Citation2021). According to the study’s findings, PsyCap positively influences readiness to change (RTC), or in other words, a high PsyCap can increase RTC (Annisa & Novliadi, Citation2019; Demos, Citation2019; Kartika et al., Citation2021; Kirrane et al., Citation2017; Liu, Citation2021; Luo et al., Citation2022; Ningrum & Salendu, Citation2021; Sani & Hajianzhaee, Citation2019; Sastaviana, Citation2022).

Shah et al. (Citation2017) found that organizational readiness to change can be influenced by perceived organizational support (POS), while individual factors can be driven by self-efficacy and personal resilience that reflects PsyCap. Individuals who resist change may find their energy physically and emotionally drained during organizational change, but these adverse effects can be suppressed and reduced when POS is high (Kurtessis et al., Citation2017; Rockstuhl et al., Citation2020). The influence of POS on change is much greater than that of some prevalent attitudes and individual behaviors, as discussed in the existing literature on organizational behavior, thus highlighting its crucial role in facilitating change (Gigliotti et al., Citation2019). Existing research examining the impact of perceived organizational support (POS) on change readiness has consistently demonstrated a positive relationship. The findings always indicate that higher levels of POS are associated with greater levels of preparedness among employees to navigate and adapt to organizational change effectively. In other words, POS has a positive influence on RTC (Ganni et al., Citation2018; Gigliotti et al., Citation2019; Kebede & Wang, Citation2022; Lestari, Citation2022; Prakoso et al., Citation2022; Ramdhani & Desiana, Citation2021; Taufikin et al., Citation2021).

The change will be successful if individuals in organizations with high work engagement fully support it. Committed individuals are less likely to lose interest and quit when faced with major organizational changes (Meria et al., Citation2022). The crucial factor for facilitating meaningful transformation is the effective engagement of people by management at the organizational level (Parent & Lovelace, Citation2018). When confronted with inevitable organizational change, individuals with heightened work engagement tend to demonstrate greater adaptability than those with lower engagement levels (Raditya et al., Citation2021). Matthysen and Harris (Citation2018) state that workers with high work are more energetic in their tasks, feel more attached to their jobs, are better able to deal with workplace responsibilities, and typically regard the change process as good. Consequently, organizations are compelled to foster engagement. A high WE for lecturers will motivate them to deliver optimal performance and more potential for implementing changes by communicating innovative ideas reflected in teaching, research, and community service activities. Tamar and Wirawan (Citation2020) found that PsyCap contributes positively to WE, which can increase positive behavior at work (Giancaspro et al., Citation2022). This study provides further evidence supporting earlier research that establishes a positive and significant relationship between PsyCap and WE (Alessandri et al., Citation2018; Chen, Citation2018; Diedericks et al., Citation2019; Du Plessis & Boshoff, Citation2018; Kotzé & Nel, Citation2019; Lupsa et al., Citation2020; Niswaty et al., Citation2021; Wirawan et al., Citation2020).

Employee views of organizational support can help to improve work engagement. In other words, POS has a positive impact on WE (Adil et al., Citation2020; Imran et al., Citation2020; Jia et al., Citation2019; Najeemdeen et al., Citation2018; Oubibi et al., Citation2022; Rizky et al., Citation2022). Organizational change requires employee readiness to change, and POS can positively contribute to RTC through the role of WE (Rizky et al., Citation2022). Previous studies analyzing the effect of WE on RTC stated that in organizational change, WE could increase employee readiness to change (Matthysen & Harris, Citation2018; Meria et al., Citation2022; Shafi et al., Citation2021).

Although many empirical studies prove that PsyCap, POS, and WE influence RTC in the context of the transformation that has been studied previously, it is still found that PsyCap has no impact on RTC in adopting an e-learning system (Kartika et al., Citation2021) also the merger of private universities (Putra et al., Citation2021). Previous studies have found that POS does not affect RTC (Al-Hussami et al., Citation2018), and WE does not directly affect RTC (Raditya et al., Citation2021). It proves the existence of a contradictory gap in the literature. It requires the current research response to elaborate through new research to find confirmation of research results to guarantee the consistency of research results. This research also indicates a less-studies/under-research gap literature in the WE mediation role category. Prior studies have emphasized and suggested the need for additional investigation into the relationship between WE and RTC during the phase of organizational change (Mäkikangas et al., Citation2019; Mitra et al., Citation2019; Roczniewska & Higgins, Citation2019). The primary objective of this study is to address a gap in existing scholarly literature by examining the factors that precede work engagement and the subsequent impact on readiness to change.

This study aims to examine the impact of psychological capital and perceived organizational support on readiness to change, with lecturer work engagement as a mediating factor within the context of private institutions in Indonesia. Hopefully, this research can contribute to building human resource development strategies to adapt to organizational changes, especially in universities and other organizations globally.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1. Relationship between PsyCap and RTC

PsyCap is part of the theory of Positive Organizational Behavior (POB), an organizational behavior approach that focuses on understanding and encouraging positive aspects in work and organizational contexts (Luthans, Citation2002). Psychological Capital (PsyCap) refers to a state of positive psychological growth in individuals (Luthans et al., Citation2007). It encompasses several vital attributes, including self-efficacy, which involves having the confidence to undertake and invest effort in completing demanding tasks. Additionally, PsyCap maintains an optimistic outlook by attributing success to the present and future. It also entails persistence in pursuing goals and the ability to adapt and redirect goals, if necessary, to achieve success (hope). Lastly, PsyCap encompasses the capacity to manage and minimize problems and challenges effectively, enabling individuals to survive, surpass their initial state, and attain success (resiliency).

Individuals with good PsyCap will be more flexible and adaptive in their behavior and can meet demands dynamically. So, this PsyCap will have a positive impact on individuals who are facing organizational change (Luthans, Citation2002). Readiness to change can convince employees that the organization will advance by implementing changes. Furthermore, they have a constructive attitude toward organizational change and are willing to participate in its implementation (Armenakis et al., Citation1993). PsyCap plays a role in openness to change, such as self-confidence, optimism, and hope, resulting in positive behavior and concern for the organization. Employees with good PsyCap will more readily accept and agree to change.

Many researchers have explored PsyCap’s relationship with RTC. Research by Liu (Citation2021) conducted on employees in China shows that PsyCap has a positive impact on openness to change. The results of this study support other studies which state that PsyCap, which comprises self-efficacy, resilience, hope, and optimism, positively influences the readiness of employees to confront diverse types of change (Annisa & Novliadi, Citation2019; Kirrane et al., Citation2017; Luo et al., Citation2022; Mufidah & Mangundjaya, Citation2018; Ramdhani & Desiana, Citation2021; Sastaviana, Citation2022). Based on previous research, we develop the following hypothesis:

H1:

PsyCap has a positive effect on RTC.

2.2. Relationship between POS and RTC

The formation of the RTC is significantly influenced by how individuals perceive the support and dedication of the organization to change (Armenakis & Harris, Citation2009). POS is defined by Robbins and Judge (Citation2015) as the extent to which employees perceive that their contributions are appreciated and that the organization genuinely concerns itself with their welfare. According to organizational support theory, employees can acclimate to their organization, recognize the organization’s appreciation for their labor and concern for their interest, and reciprocate this support through enhanced productivity, commitment, and allegiance. Eisenberger et al. (Citation2002) explain that the reciprocal relationship between employees and organizations can be understood through social-exchange theory. The formation of POS can be inferred from employees perceiving that the organization demonstrates concern for their well-being and acknowledges their contributions. Individuals with high POS will view their organization positively (Kurtessis et al., Citation2017). Referring to the theory of social exchange in organizations, POS will instill in employees a sense of responsibility to look out for the organization’s welfare and assist in attaining its objectives. POS functions within the framework of change by facilitating the management of participation and evaluation (Fuchs & Prouska, Citation2014) and thus can change the recipient’s perception of the change. The concept of readiness to change (RTC) encompasses a broad mindset that is influenced by various factors, including the content of the changes being considered, the methods via which these changes are implemented, the context in which the changes take place, and the individual attributes necessary for successful change within an organization (Holt et al., Citation2007). Employees who resist change will feel physically and emotionally drained during the organizational change process. However, this adverse effect can be turned into acceptance of change when employees have a high POS (Turgut et al., Citation2016).

Prior studies have investigated the correlation between perceived organizational support (POS) and individuals’ readiness to change, revealed that POS significantly impacts individual behavior in dealing with change and can increase RTC (Arnéguy et al., Citation2020; Gigliotti et al., Citation2019; Kirrane et al., Citation2017; Mufidah & Mangundjaya, Citation2018; Munawaroh et al., Citation2021). In the context of changes in the university environment, research on private university lecturers found that POS can positively predict lecturer readiness to face change (Taufikin et al., Citation2021). Based on prior research, the subsequent hypotheses may be formulated:

H2:

POS has a positive effect on RTC.

2.3. Relationship between WE and RTC

Work Engagement refers to an employee’s self-control over their work role, characterized by their dedication to their tasks and the active involvement and expression of their thoughts, feelings, and senses in the execution of their work (Kahn, Citation1990). Bakker and Demerouti (Citation2008) and Kahn (Citation1990) formulated the JD-R Model. This theoretical framework elucidates the relationship between work engagement and well-being by considering the impact of job characteristics (including demands and resources). As a result of their strong emotional attachment to the organization, employees with a high WE level are more likely to complete their work satisfactorily (Schaufeli & Bakker, Citation2004). Resistance to organizational change initiatives can be mitigated; organizational readiness to change is the determining factor. Research has shown that highly engaged employees are more inclined to exert effort to effect change, suggesting that they cultivate favorable attitudes towards organizational change. Dalton and Gottlieb (Citation2003) posit that readiness comprises conditions and processes. Condition readiness is substantially impacted by the environment in which it will transpire and is substantiated by the conviction that the proposed change is essential. As a process, readiness consists of cost-benefit analysis, change planning, and identifying the necessity for change. Engagement at work is a significant factor in employee adoption of change. It implies that organizations must concurrently consider employee engagement to effect change, as this discovery facilitates the implementation of changes by leaders. Additionally, prior research proves that WE positively impacts RTC (Shafi et al., Citation2021).

According to another study, work engagement positively affects change readiness (Matthysen & Harris, Citation2018). An increase in employee engagement positively correlates with their readiness for organizational change. Employees who demonstrate support for change tend to exhibit higher energy levels and a stronger sense of work engagement, enhancing their capacity to manage job demands (Prakoso et al., Citation2022; Wulandari et al., Citation2020). Based on prior investigations, the subsequent hypotheses may be formulated:

H3:

WE has a positive effect on RTC.

2.4. Relationship between PsyCap and WE

Thompson et al. (Citation2015) have introduced PsyCap as an employee personal resource. Vigor, dedication, and absorption are the WE components that can be significantly predicted by the combined effect of the four components comprising PsyCap (Alessandri et al., Citation2018). Increased work engagement can be attributed to providing adequate personal resources to manage the job demands effectively. PsyCap includes mental resources people accumulate and conceal when things are going well and poorly.

In circumstances characterized by significant and demanding transformations, individuals possessing PsyCap are more inclined to experience a sense of control over the situation. Consequently, fully engaging in the tasks that characterize WE becomes more accessible. Work engagement encompasses positive aspects of work-related behavior, specifically the cognitive and emotional connection between employees and their work. It is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption in the work context work (Schaufeli & Bakker, Citation2004).

Numerous empirical investigations have explored the correlation between PsyCap and WE, proving a positive influence between PsyCap and WE. It means that the better the employee’s PsyCap level, the more optimal they will devote their abilities to work and the more emotionally attached to work (Kotzé, Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2018; Lupsa et al., Citation2020; Niswaty et al., Citation2021; Tisu et al., Citation2020). Those employees who exemplify this PsyCap will be focused on achieving success. They perceive workplace activity as a chance to consolidate additional resources, which enhances their engagement level. Given the findings of prior research, the subsequent hypothesis may be formulated:

H4:

PsyCap has a positive effect on WE.

2.5. Relationship between POS and WE

POS is increasingly recognized as significant in boosting employee commitment and satisfaction. POS is a kind of cooperation or support needed to carry out the work effectively (Hakkak & Ghodsi, Citation2013; Imran et al., Citation2020). Employees who possess a high level of POS hold optimistic beliefs regarding the organization’s response to their contributions and errors and, as such, are more willing to accept the consequences for their self-image, status, or career as a result of investing entirely in their work. Support and challenging work are the two sources of work found towards work engagement (Byrne et al., Citation2016). Employees with high work engagement enjoy their work and are willing to provide all the help they can to succeed in their work organization. Ahmed et al. (Citation2015) examined 112 papers in a meta-analysis. The findings validate that POS exerts a substantial positive impact on WE. POS is associated with increased work engagement in organizational objectives, as evidenced by increased resilience, commitment, and personal welfare. POS fosters individual zeal, joy, vitality, dedication, and a profound concern for the organization (Lan et al., Citation2020).

A study conducted in Malaysia involving university teaching staff analyzed the influence of POS on WE. This study also reports that POS significantly impacts WE (Najeemdeen et al., Citation2018). Likewise, research results on nurses prove that POS positively affects WE (Al‐Hamdan & Issa, Citation2021). Employees who are psychologically and mentally attached to the organization as a result of POS may be more committed to attaining organizational objectives than to pursuing personal goals. The positive influence between POS and WE was reaffirmed in several previous studies, which also revealed that POS is a predictor of WE (Adil et al., Citation2020; Al-Hussami et al., Citation2018; Al‐Hamdan & Issa, Citation2021; Aldabbas et al., Citation2021; Imran et al., Citation2020; Jia et al., Citation2019; Nasurdin et al., Citation2018; Oubibi et al., Citation2022). Therefore, drawing from the findings of prior research, the subsequent hypothesis may be posited:

H5:

POS has a positive effect on WE.

2.6. Work Engagement (WE) as mediators

Prior empirical and literary research has demonstrated that work engagement mediates the relationship between self-efficacy and RTC (Meria et al., Citation2022), where self-efficacy indicates PsyCap. The study conducted on public sector employees in Korea found that psychological ownership impacts WE and openness to change. WE positively influences employee knowledge and creativity directly to their readiness to change (Chai et al., Citation2020).

The successful implementation of organizational change necessitates the presence of a conducive work environment and the possession of favorable personal resources by employees, including self-efficacy, optimism, and self-leadership. These individual attributes have the potential to exert a beneficial impact on the process of organizational change. Employees play a pivotal role as catalysts of change, exerting their effect on the organizational environment through strategically utilizing behavioral approaches and shaping resources and attitudes toward change. This particular process has an impact on fostering positive attitudes, including work engagement and adaptive performance (Heuvel et al., Citation2010). From the findings of prior research, it is possible to formulate the subsequent hypotheses:

H6:

WE mediates the effect of PsyCap on RTC.

Prior research has identified the mediating effects of WE in conjunction with several antecedent and consequence variables (Saks, Citation2019). Nonetheless, the mediating function of WE in the relationship between POS and RTC has been the subject of few studies. Rizky et al. (Citation2022) demonstrate through research on post office personnel that WE mediates the favorable effect of POS on RTC. Following the JD-R theory, one could contend that POS provides numerous WE-related job resources, ultimately increasing employee disclosure and RTC in pursuit of organizational objectives. Extensive research has been conducted on the antecedents and consequences of WE utilizing the JD-R model (Saks, Citation2021).

Perceived organizational support significantly creates positive intentions toward the organization, leading employees to be more engaged (Aldabbas et al., Citation2021). An engaged employee is more innovative, productive, and willing to exert additional effort. Therefore, WE becomes crucial during a change to create RTC and counter cynicism towards change. RTC is one of affirmative behavior. Therefore, when employees feel that the organization regards them as a valuable asset, they try to become more active in organizational activities. As a result, they are more innovative and supportive of organizational development (Fu et al., Citation2022). The following hypothesis can be made based on the existing literature:

H7:

WE mediates the effect of POS on RTC.

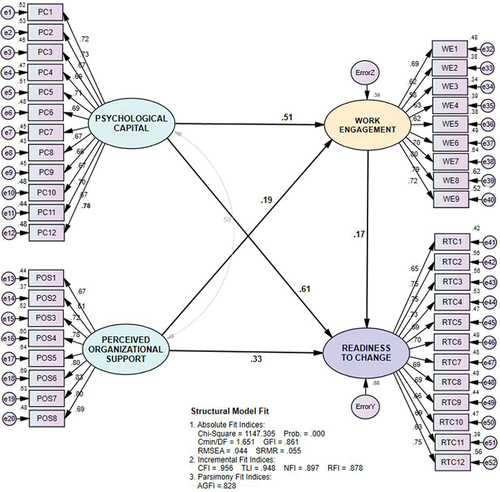

Based on the hypothesis developed, the research framework is presented in Figure .

3. Method

3.1 Data collection

We collected data in this study by distributing questionnaires online through Google Forms. Data was collected for five months, from January to May 2023. The study population was faculty members at private universities in Indonesia, with a sample of 342 lecturers as respondents. The sampling technique is convenience sampling. This sampling technique involves selecting people the researcher can easily access and contact (Sekaran & Bougie, Citation2016). Convenience sampling refers to selecting respondents who are the easiest for researchers to obtain information.

The study’s ethical aspects were conducted following the principles of research ethics. Ethical approval has been issued by the Jakarta State University Doctoral Program in Management Sciences. Respondents volunteer to participate in research and have the opportunity to withdraw as participants if they believe there is a professional danger or a personal view associated with the investigation. Before completing the questionnaire, the cover letter explained the research’s objective so that participants could better understand each question and choose answers according to their perceptions.

3.2 Measurement

This study adopts measurements related to the variables studied from previous studies. The PsyCap variable is measured with 12 questions adapted from (Luthans et al., Citation2007), which reflects self-efficacy, resilience, hope, and optimism. An example of measurement items are “I’m optimistic about what will happen to me at work in the future” and “I’ve been through tough times at work before, so I know how to get through them”. The POS variable is measured using 8 questions adopted from (Rhoades & Eisenberger, Citation2002; Rudnák et al., Citation2022) using indicators including fairness, supervisor support, and organizational rewards and working conditions. Examples of measurement items include “The organization takes my goals and values very seriously” and “The organization is concerned about my overall job satisfaction”. The WE variable was adopted from the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9), representing the dimensions of vigor, dedication, and absorption consisting of 9 questions. Examples of measurement items are “I’m excited about my job.” and “I’m completely absorbed in my work”. The RTC variable is measured using 12 questions adapted from (Holt et al., Citation2007), which have parameters namely appropriateness (accuracy to make changes), change efficacy (belief in one’s ability to change), management support (management support), and personal benefits (benefits for individuals). Examples of measurement items are “I think that the organization will benefit from this change” and “This change will not disrupt many of the personal relationships I have developed”. The entire questionnaire is available in the Appendix. The measurement of all items was conducted using a Likert scale consisting of five scales, which ranged from 1 (indicating severe disagreement) to 5 (indicating strong agreement).

3.3. Data analysis

The present study used a first-order model, wherein variables are directly measured via indicators. The use of first-order refers to the article that is used as a reference (Arnéguy et al., Citation2020; Li et al., Citation2018; Liu, Citation2021; Niswaty et al., Citation2021; Oubibi et al., Citation2022; Ramdhani & Desiana, Citation2021). In addition, considering the number of parameters measured and the number of samples obtained, the estimation results will be better if using a first-order model because the more complex the research model, the larger the sample size (Ferdinand, Citation2015; Hair et al., Citation2014).

3.3.1. Validity and reliability

The questionnaire in this study was declared to have fulfilled content validity because it was based on a strong theoretical basis in its preparation and was adopted and adapted from a reputable journal. The intercorrelation measures the validity of the criteria method by determining the corrected item-total correlation, which is the value of the correlation between the scores of each item and the total score. Criteria validity is established when an item possesses a positive correlation coefficient exceeding 0.30; therefore, each statement item is deemed valid if its correlation value surpasses 0.30 (Malhotra & Birks, Citation2007). Table shows each statement item’s corrected item-total correlation values , ranging between 0.447 and 0.890 (all more than 0.30).

Table 1. Validity and reliability test results

Convergent validity shows how much the weight of each statement item reflects the variable measured using the factor loading value resulting from one-factor exploratory factor analysis. If the loading factor value exceeds the limit value, the indicator is said to have reached convergent validity. In sign factor loading, the minimum is 0.50, and the preferred is 0.70 (Hair et al., Citation2014). The convergent validity test was conducted on each statement item, and the results indicate that all items have loading factors exceeding 0.50, as displayed in Table . Discriminant validity represents the last stage of the validity test. Discriminant validity pertains to the fundamental tenet of minimal correlation between distinct variable measures. The discriminant validity measurement results show that the root AVE value of each variable exceeds the correlation between that variable and other variables.

That reliability measure ranges from 0 to 1 (Hair et al., Citation2014). Cronbach’s Alpha has a generally accepted lower bound of greater than 0.70 (excellent reliability), with values between 0.60 and 0.70 regarded as the lower acceptable range (acceptable reliability). Cronbach’s alpha values for each of the four variables (PsyCap, POS, WE, and RTC) are shown in Table (all are greater than 0.70), indicating that the questionnaire statement items used to measure these constructs can be considered reliable and trusted as a measuring tool.

3.3.2. Common method bias

Common Method Variance (CMV) is a strategic procedure to minimize bias in research. At the same time, Common Method Bias (CMB) is a statistical procedure to test for the presence or absence of bias. This study adopted a procedural CMV and a statistical CMB strategy to control for bias. Regarding the procedure, the researcher made a questionnaire that was explicitly adapted to the conditions of private universities in Indonesia for easy understanding, presenting measurement items in different sections for each construct, selecting respondents who are sufficiently knowledgeable and sufficiently experienced (do not select respondents whose working period is less than one year), and ensure protection of the respondent’s anonymity throughout (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). This procedure ensures that respondents can answer questions carefully and honestly. Thus, through this procedural strategy, the researcher stated that the data was obtained from reliable information sources and there was no bias in the data collection procedure.

Furthermore, with a statistical strategy, the researcher conducted a Harman single-factor test with the EFA and CFA approaches. The EFA results show four factors with eigenvalues above 1, explaining 52.1% of the total variance. The first extracted factor explained only 36.6% of the total variables (below 50%), thus not accounting for most of the variance.

In addition, CFA is also used by connecting all construct items into one method factor. The fit index (probability chi-sq 0.001; CFI 0.567; TLI 0.544; NFI 0.528; RFI 0.503; and PNFI 0.501) cannot be accepted because it is far from the minimum standard of 0.90, so the fit model is not fit if all items are forced into a single factor method. Based on statistical examination, the researcher concluded that the respondents responded differently to each variable even though the statement items were written in the same questionnaire. It shows that the respondents read the questionnaire statements before giving a response (answers). Thus, it can be concluded that general method bias is not a major concern in this study.

4. Results

4.1. Description of respondent characteristics

Respondents of this research are faculty members at a private university in Indonesia. The number of samples collected was 342 respondents. Respondent characteristics are based on gender, education, age, working period, academic position, and lecturer professional certification. Table shows the results of the description of the respondents’ characteristics.

Table 2. Respondent characteristics

4.2. Analysis of measurement model

A measurement model analysis aims to determine whether or not the concept’s indicators are valid and reliable measures of that construct. The CFA test, or measurement model analysis, consists of three phases: assessing the measurement model fit, establishing construct validity, and establishing construct reliability. The results of the measurement model meet the requirements good fit and marginal fit (probability chi-sq 0.000; CMin/DF 1.626; GFI 0.863; RMSEA 0.043; SRMR 0.055; CFI 0.958; TLI 0.950; NFI 0.899; RFI 0.880; and AGFI 0.830).

We test for construct validity after ensuring the measurement model fits well. Construct validity shows testing to find out how far the indicator measures the construct. In SEM, the construct validity test is carried out through convergent validity, with the rule of thumb being said to meet convergent validity when indicators in the construct have a standardized regression weight (factor loading) value of at least 0.50 and preferable 0.70 (Hair et al., Citation2014). The results of the construct validity evaluation for each construct are presented in Table . When the measurement model fits well, the construct validity is evaluated. Construct validity testing demonstrates the extent to which an indicator measures the construct. Convergent validity is used in structural equation modeling (SEM) to determine construct validity. To fulfill convergent validity, construct indicator factor loadings (standardized regression weights) at least 0.50 and ideally 0.70 (Hair et al., Citation2014).

Table 3. Construct Validity and Reliability Test

Assess the reliability of the construct by utilizing the construct reliability value; a construct is deemed reliable when the construct reliability value exceeds 0.70. Hair et al. (Citation2014) state that construct reliability values should generally exceed 0.70. However, construct reliability values above 0.60 are deemed adequate, provided that each indicator satisfies the criterion for convergent validity. Table demonstrates that each variable provides a construct reliability score of more than 0.70. In addition, all AVE values are more than 0.50. Thus, it is determined that these indicators are reliable in the measuring model in reflecting the construct PsyCap, POS, WE, and RTC.

4.3. Analysis of structural model

The structural model analysis begins once the measurement model analysis is complete. The structural model stage starts with assessing the model’s applicability (goodness of fit), which verifies that the constructed model corresponds to the data (fit). The subsequent statements detail the outcomes of the fit index computation performed by the structural model ( and Table ).

Table 4. Fit measures on structural models

Table shows the R12 value of 0.394, indicating that psychological capital and perceived organizational support influence lecturers’ work engagement by 39.4%. Other variables, in contrast, have an impact on the remaining 60.6%. The R22 value is 0.884, which indicates that psychological capital, perceived organizational support, and work engagement account for 88.4% of the variance in readiness to change to lecturers. As a comparison, the remaining 11.6% is influenced by other variables.

Table 5. Coefficient of Determination(R2)

The total coefficient of determination (total R2) is 0.734. It demonstrates the model developed in this study can explain about 73.4 % of the variability of the data. In another sense, the model in this study is very good or relevant to predicting work engagement and readiness to change lecturer at a private university through psychological capital and perceived organizational support.

4.4. Hypothesis testing

4.4.1. Direct effects analysis

The initial phase involves evaluating the direct effect hypothesis explicitly examining the parameter estimates that describe the link between variables associated with each theoretical hypothesis. The acceptance of the hypothesis is contingent upon the statistical significance of the path parameters in conjunction with the projected direction of impact. Specifically, the path parameters must exceed zero for a positive direction of influence, whereas for a negative direction of effect, the path parameters must be less than zero (Hair et al., Citation2014). Table presents the results of the direct influence test in the context of testing the research hypothesis:

Table 6. Direct effect analysis

4.4.2. Indirect effect analysis

In the subsequent phase of hypothesis testing, the indirect effect is examined. SEM employs a bootstrap approach and a bias-corrected percentile method to assess the significance of the path of indirect influence. This method is an extension of the Sobel Test modified for the SEM context. We measure the significance of the mediation effect using the critical ratio (CR) and probability value (p-value). Using the criteria of a CR value of at least 1.96 or a p-value of at least 5% at the 5% level of significance to determine whether the influence between variables is significant or not, it is determined that a significant mediating effect exists.

After evaluating the effect of mediation’s significance, the next stage is to ascertain the specific type of mediation. The nature of mediation can be discerned by examining its impact on endogenous variables when the direct influence of exogenous variables on them is substantial. Partial or complementary mediation is how significant pathways and mediating variables facilitate indirect effects. On the contrary, consider a scenario in which the direct impact of exogenous variables on endogenous variables is not statistically significant. Still, the indirect effect via mediating variables follows a significantly long path. Complete or perfect mediation is the term used to refer to this situation (Baron & Kenny, Citation1986). The test results of the mediating role of WE in the indirect effect of PsyCap and POS on RTC are presented in Table .

Table 7. Indirect effect analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. The effect of psychological capital on readiness to change

The study results show that PsyCap has a positive effect on RTC. It can be interpreted that the better the psychological capital the lecturer possesses, the greater the lecturer’s readiness to face change. The findings of this study support prior evidence indicating PsyCap has a positive influence on RTC (Annisa & Novliadi, Citation2019; Demos, Citation2019; Kirrane et al., Citation2017; Luo et al., Citation2022; Mufidah & Mangundjaya, Citation2018; Sani & Hajianzhaee, Citation2019; Sastaviana, Citation2022). Positive feelings about one’s ability to overcome challenges will foster readiness to accept change so that one can work simultaneously and try to succeed by completing tasks well (Ramdhani & Desiana, Citation2021).

High-resilient lecturers can adapt and deal with every event, problem, and pressure in their careers. Lecturers who may encounter difficulties in scientific publications do not give up easily and stay focused on the goal. An optimistic attitude and a great hope for change will encourage lecturers to think positively that the current changes will positively impact their careers. This attitude enables them to be willing to find learning resources to improve their knowledge and skills, for example, through informal training outside the university. Beliefs also have a particular influence on readiness to change. Trust in their abilities makes them more receptive to academic and non-academic changes. In addition, high self-confidence can encourage lecturers to be brave, come up with new ideas, and find the best solutions to adapt to new habits in change. In Indonesia’s higher education world, policies related to developing and evaluating lecturer tri-dharma activities always experience adjustments to market needs. Lecturers with good psychological capital will tend to be cognitively flexible to deal with changes in learning methods, curriculum development, or new approaches in the educational environment. A readiness to learn and adapt to the widespread implementation of information systems on campus is another manifestation of an open mind.

When considering employee RTC, PsyCap is crucial in human resource management. Employees who are upbeat, self-assured, hopeful about the future, and resilient enough to bounce back from setbacks are better equipped to handle change demands. To be better psychologically equipped to adjust to new work practices, reorganization, and organizational transformation, employees with high PsyCap typically exhibit greater openness and enthusiasm toward novel ideas. PsyCap is a tool that helps workers deal with uncertainty brought on by significant change by overcoming fear and worry. This study’s findings corroborate earlier studies showing that PsyCap improves RTC (Annisa & Novliadi, Citation2019; Demos, Citation2019; Kirrane et al., Citation2017; Luo et al., Citation2022; Mufidah & Mangundjaya, Citation2018; Munawaroh et al., Citation2021; Sani & Hajianzhaee, Citation2019; Sastaviana, Citation2022).

5.2. Effect of perceived organizational support on readiness to change

Research data analyses indicate that POS has a beneficial impact on RTC. The findings suggest that higher levels of organizational support are associated with greater levels of lecturers’ openness and readiness to embrace change. The results of this research corroborate the conclusions drawn in several prior studies that a strong POS correlates directly with a lengthy RTC; that is, as POS increases, so does readiness to change (Arnéguy et al., Citation2020; Gigliotti et al., Citation2019; Kebede & Wang, Citation2022; Kirrane et al., Citation2017; Mufidah & Mangundjaya, Citation2018; Munawaroh et al., Citation2021). Employees, especially those who resist change, may find their energy physically and emotionally drained during organizational change, but these adverse effects can be suppressed and mitigated when POS is high (Kurtessis et al., Citation2017; Turgut et al., Citation2016).

Procedural fairness that the university applies to lecturers in assignments or self-development training according to their expertise creates enthusiasm and openness towards developing new science and technology. They are given space to maximize their potential according to their respective fields, so lecturers will try to make more effort to produce performance according to their expertise. This enthusiasm will make lecturers more open-minded to understand and accept the ever-changing developments in science and technology.

Organizational support is generally reflected directly in the behavior of leaders toward lecturers. Leaders in higher education, including the rector or dean, who consistently prioritize the well-being of lecturers, consider the degree of lecturer satisfaction in taking all actions and decisions, and have the ability to provide solutions to lecturer problems can lead to lecturer perceptions that the organization provides full support for lecturer work activities. Resources such as reliable technology, up-to-date learning resources, and practical, responsive administrative support can reduce barriers to change processes. Moreover, according to the theory of organizational social exchange, a mutualistic relationship will exist when lecturers perceive that their well-being and contentment are duly attended to (Eisenberger et al., Citation2002). Reciprocity between universities and lecturers is that good treatment received by one party must be reciprocal to produce benefits for both parties. Establishing a mutualistic reciprocal relationship engenders a sense of obligation among lecturers to prioritize the organization’s welfare and actively contribute towards attaining organizational objectives by increasing the quality of the tri-dharma (teaching, research, and community service).

The appreciation and pride of the organization shown by the leadership in the contribution of each lecturer in achieving the university’s vision, mission, goals, and strategic plans foster a superior perception for lecturers. Lecturers see that organizations can provide conducive working conditions and treat them according to their positive values. Organizational rewards and good working conditions further motivate lecturers to act more as a form of responsibility as part of the organization. Openness to discussing and collaborating between lecturers about changes can positively impact knowledge sharing and self-strengthening. This attitude is needed when the organization faces change. This good social exchange and reciprocity can encourage the lecturer’s acceptance of the change.

From the standpoint of human resource management, organizational support positively impacts employees’ readiness to confront and adapt to change. Providing organizational support fosters a sense of appreciation among employees and enhances their receptiveness toward changes implemented by management. The recognition and acknowledgment exhibited by management towards employees who effectively embrace and adjust to change will motivate other employees to enhance their preparedness. The feedback process between employees and management fosters a sense of validation among employees, as it ensures that their perspectives on the change plan are acknowledged, enhancing their readiness for its implementation. In the context of change, POS manages involvement and appraisal of change, which can potentially alter the recipient’s view of the change (Fuchs & Prouska, Citation2014). It suggests that an increase in POS quality corresponds to improving RTC. Prior research, which stated that POS is a positive predictor of lecturer readiness to change (Taufikin et al., Citation2021), is further supported by the findings of this study concerning the same unit of analysis.

5.3. Effect of work engagement on readiness to change

The findings indicated that WE exhibited a positive impact on RTC. This positive influence means that lecturers’ high WE will increase their readiness for change. A high WE can reduce resistance to organizational change efforts. Work engagement becomes essential in organizational change readiness because one of these psychological factors is crucial for change implementation (Armenakis et al., Citation1993). This research indicates that lecturers committed to their profession are more inclined to seek improvements within the tertiary institution where they are employed. A high WE for lecturers can be reflected in their willingness and persistence in carrying out work no matter how difficult. In dealing with change, support from lecturers, energy, enthusiasm, and high stamina at work are needed. This strength makes lecturers want to try their best to accept change because change brings progress and more benefits to lecturer work.

Work engagement can describe the dedication of lecturers to work. This dedication refers to a meaningful feeling of the usefulness of knowledge, passion, pride in carrying out their work and feeling inspired and challenged by new things in everyday life. Then, it can be reflected in the attitude of lecturers in teaching who are sincere, have a fighting spirit to provide understanding to their students, and conduct research and community service wholeheartedly. Lecturers with a high dedication score identify with their work because it offers valuable, inspiring, and challenging experience in carrying out all teaching, research, and community service activities. Lecturers will contribute more optimally to innovation through research publications, downstream research results, and increasing the number of copyrights and patents. This psychological factor supports them in adapting to new things in the process of change. Lecturers who support change feel connected to their jobs and can better handle the demands of work in general (Wulandari et al., Citation2020). The change will be more manageable if the lecturer possesses a high WE and is willing to exert more significant focus, concentration, and intensity on a particular task (Meria et al., Citation2022). Dedication to work makes them persistent, passionate, and enthusiastic about learning because they believe that change will benefit them as individuals who must develop.

Employees with high WE are enthusiastic about their jobs. These attributes enable employees to meet the obstacles of change with optimism. Because they are eager to learn new things and increase their potential, they adapt more quickly to diverse conditions at work. Engaged employees believe their work is valuable. Therefore, they are motivated to provide their all for the organization, even when faced with change. As a result, work engagement is a critical HR management aspect in increasing employee readiness for organizational transformation. Previous research that established a positive relationship between WE and RTC is corroborated by the findings of this study, where it is known that high WE can positively increase RTC (Matthysen & Harris, Citation2018; Meria et al., Citation2022; Prakoso et al., Citation2022; Shafi et al., Citation2021; Wulandari et al., Citation2020). WE shows the critical role of lecturers in accepting change, meaning that when universities want to change, they must also see the engagement of lecturers in their work because it is easy for leaders to lead and direct them to change.

5.4. The effect of psychological capital on work engagement

According to this study, WE is positively affected by PsyCap. It can be interpreted as the better the PsyCap owned by the lecturer, the higher the WE. In detail, it can be concluded that lecturers with high self-efficacy, resilience, hope, and optimism will further form tenacity and perseverance in work, increase dedication, enthusiasm, and pride in their profession and work, and can encourage meaningfulness in work. WE can make lecturers more intense and focused in their careers. Integrating the four indicators that reflect PsyCap can strongly predict the components of WE: vigor, dedication, and absorption (Alessandri et al., Citation2018). Lecturers with good PsyCap will have a mindset and be success-oriented. They see on-campus activity as an opportunity to gather more valuable resources for their studies, resulting in a higher level of engagement.

In challenging conditions of change, lecturers with good PsyCap will feel more in control of the situation, making it easier to immerse themselves in work. They have experience, strength, and confidence even in adversity, so it will be easier for lecturers to stay focused on their work. The existence of hope and optimism is a source of strength and persistence for them to continue to strive to produce the best work performance. PsyCap motivates lecturers to actively participate and be more involved in academic activities and assignments. PsyCap allows lecturers to better cope with stress, pressure, and challenges because they have strong psychological resilience. It encourages them to stay focused and energetic while carrying out tasks, which greatly impacts increasing work engagement.

Employees with self-efficacy or self-confidence in executing challenging tasks are likelier to be wholly engaged in their work. Employees’ optimism for the future will drive them to deliver their best efforts and substantial engagement. Employees who are resilient in the face of adversity have higher engagement because they can rebound from failure. Employees with high Psycap believe that their work is relevant and valuable and are enthusiastic about it (engaged). As a result, PsyCap influences employee work engagement. HRM must guarantee that this component is strengthened to maximize employee performance and productivity. The findings of this study are consistent with earlier empirical research, which has also demonstrated a favorable relationship between PsyCap and WE. So, the better the employee’s PsyCap level, the more optimally they devote their abilities to work and the more emotionally attached they are to work (Kotzé, Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2018; Lupsa et al., Citation2020; Niswaty et al., Citation2021; Tisu et al., Citation2020).

5.5. The effect of perceived organizational support on work engagement

According to the findings of this research, POS has a beneficial impact on WE. It implies that professional lecturers are more invested in their work when they positively perceive the support provided by the organization. Individual enthusiasm, happiness, energy, commitment, and significant concern for the organization are all enhanced by POS (Lan et al., Citation2020). Higher levels of organizational support are associated with greater participation by lecturers in pursuing the organization’s vision and mission. They show this tendency with individual strength, high dedication, and more intense immersion in work.

Universities that provide procedural fairness to lecturers will indirectly foster a good perception of organizational support. It can impact lecturers’ acceptance and willingness to provide the best service to their organization as a form of reciprocity. Within an organization, leadership support represents organizational support. Superiors’ support at work will trigger lecturers’ interest in focusing on working to make the best contribution to the organization. Open communication from the rector and dean regarding policies, goals, and institutional developments can increase trust and understanding and strengthen the bond between lecturers and universities. Involving lecturers in decision-making processes such as strategic planning, curriculum development, and performance appraisal increases their sense of belonging and engagement.

Facilitating the lecturer’s job fulfillment may involve creating a favorable working environment. A conducive work environment offers resources to assist instructors in conducting research and publishing, which may motivate them to concentrate more intently on delivering superior work. Professional training and development programs for lecturers, such as teaching, research, and leadership training, make lecturers feel valued and have opportunities to improve their skills, increasing their job engagement. Responsive administrative support in academic administration, data management, and assessment processes can reduce the administrative burden on lecturers, allowing them to focus more on core tasks and increase engagement. Then, support for the welfare of lecturers through welfare programs such as health insurance, recreation programs, and flexible job choices makes lecturers feel more valued and cared for. It is what can increase their bond with the university.

It is possible to conclude that lecturers’ strength, attention, and concentration on their work are a sort of reciprocal effort from lecturers who believe their contributions and values are recognized by the organization. When POS is good, lecturers have high expectations for organizational benefits for their assistance. As a result, they are more willing to fully dedicate themselves to their profession and face the implications of their self-image, status, or career.

POS positively influences WE by strengthening employees’ intrinsic motivation in their tasks (Eisenberger & Stinglhamber, Citation2011). Research conducted in Malaysia involving university teaching staff reported that POS greatly impacted WE (Najeemdeen et al., Citation2018). Additionally, research on health personnel reveals a positive correlation between POS and WE via PsyCap (Al‐Hamdan & Issa, Citation2021; Yang et al., Citation2020). Attributing greater commitment to attaining organizational objectives rather than individual ones, POS has the potential to foster psychological and mental attachment among employees. POS serves as a predictor of WE, as further supported by the findings of this study, which also demonstrate the existence of a positive correlation between POS and WE (Adil et al., Citation2020; Al-Hussami et al., Citation2018; Al‐Hamdan & Issa, Citation2021; Aldabbas et al., Citation2021; Imran et al., Citation2020; Jia et al., Citation2019; Nasurdin et al., Citation2018; Oubibi et al., Citation2022). Support from the organization makes employees more interested in their work. Employees will feel valued and supported, like they belong, and more connected to their jobs and organization. When engaged, employees try to make the best contribution possible and be very dedicated and proactive at work. So, the best way for HR management to get employees more involved is to provide optimal organizational support.

5.6. Mediation of work engagement on the influence of psychological capital on readiness to change

According to the study’s findings, the relationship between PsyCap and lecturer readiness to change in private universities in Indonesia is mediated by WE. As partial mediation is employed, increasing the RTC for lecturers by augmenting their psychological resources is possible. However, increasing RTC can also be done by strengthening WE as a behavior that is a consequence of PsyCap. In this study, WE is a mediator connecting Psycap and RTC. Enhanced WE and a propensity for positivity are indicators that lecturers possess substantial PsyCap and are better equipped to manage change. However, if high WE accompanies it, the lecturer’s RTC can be even higher. Universities require a positive work environment and psychological capital from eminent lecturers, including self-efficacy, optimism, hope, and resilience, to effectuate organizational change optimally. These factors, in turn, can positively impact the capacity to effect organizational change. Lecturers are pivotal in shaping the university environment by implementing optimized behavioral strategies, drawing upon their resources and attitudes toward change. Positive dispositions, including WE and adaptive performance, are impacted by this process. Lecturers and agents of change shape the university environment by optimizing behavioral strategies, which are influenced by personal resources and attitudes toward change. Adaptive performance and WE are positive dispositions affected by this process (Heuvel et al., Citation2010).

Lecturers with strong PsyCap feel confident and optimistic when facing change. Together with high WE, they have an emotional attachment to work and intend to contribute more. This attitude encourages them to take proactive steps to deal with change because they feel responsible for the university’s success. This WE mediation role will lead him to translate PsyCap into actual behavior in change. The findings of this research are consistent with previous research, though not identical, which found that psychological ownership impacts WE and openness to change. WE positively influences employees’ knowledge and creativity in direct proportion to their openness to change (Chai et al., Citation2020). Then, self-efficacy, one of PsyCap’s indicators, was also found to influence RTC through WE’s role as a mediator (Meria et al., Citation2022).

5.7. Mediation of work engagement on the effect of perceived organizational support on readiness to change

According to the study’s findings, the relationship between POS and the RTC of lecturers at private universities in Indonesia was mediated by WE. Partial mediation is employed, which entails augmenting organizational support to facilitate increased RTC for lecturers. However, increasing RTC can also be done by strengthening WE as an attitude that arises from perceptions of good organizational support. Organizational support felt by lecturers significantly raises positive intentions towards tertiary institutions, which directs lecturers to work more actively. Participatory lecturers increase their output, ingenuity, and willingness to exert additional effort. Therefore, WE becomes important as a force to create readiness for change and fight cynicism towards change. RTC is one of affirmative behavior. As a result, lecturers make more tremendous efforts to participate in organizational activities, are ultimately more innovative, and support organizational change when they perceive that their institution regards them as a valuable asset.

Lecturers with solid support from tertiary institutions will feel responsible for the organization’s success due to high work engagement. They want to contribute to college success by committing to adapt and taking real action to deal with change. Work engagement mediation has a positive effect that increases organizational support for readiness to change. The findings of this study are consistent with prior research that demonstrates WE mediates the favorable impact of POS on RTC (Rizky et al., Citation2022). Following the JD-R theory, it can be posited that organizational support is likely to provide work-related resources that contribute to job engagement, ultimately fostering employee receptiveness and preparedness for change to attain organizational objectives. According to Aldabbas et al. (Citation2021), providing organizational assistance can enhance the level of engagement and commitment among members of an organization, hence fostering a more diligent and dedicated approach to work. Organizational support is predicated on the notion that employees are esteemed assets. Consequently, individuals increase their engagement in corporate endeavors, fostering enhanced creativity and facilitating organizational change (Fu et al., Citation2022).

Within the literature on organizational behavior, it is commonly observed that the relationship between two variables is frequently subject to moderation and mediation by additional variables. Further exploration of the middle variable’s role is needed to explain why and how the two are related (Nwanzu & Babalola, Citation2019). The relationship between PsyCap and POS on RTC through the mediation of other variables has been studied before. Existing research suggests that a leadership style perspective completely mediates the relationship between PsyCap and openness to change (Soeharso & Dewayani, Citation2020). Then, the relationship between POS and RTC in previous studies can be partly explained by trust in management. Change recipients can use this trusted source to increase readiness to change (Gigliotti et al., Citation2019). Affective commitment also serves as a bridge between POS and readiness to change. However, the presence of affective commitment can reduce the influence of POS on change readiness (Rochmi & Hidayat, Citation2019).

Ultimately, the findings of this study contribute to the existing body of knowledge in organizational behavior by identifying mediators that have the potential to predict RTC. This study supports the idea that WE can mediate the association between PsyCap and POS toward RTC. Empirical research has indicated that the mediating role of WE in the relationship between PsyCap and RTC is greater than the mediating role of WE in the association between POS and RTC. The outcomes of this study indicate that improving lecturer PsyCap has a stronger influence on strengthening the mediating role of work engagement in fostering readiness to change than increasing organizational support. Hence, it is recommended that universities give precedence to expanding lecturer PsyCap and WE development programs to enhance RTC.

6. Conclusion

All hypotheses in this study are accepted and have been successfully proven, where PsyCap and POS influence RTC directly or indirectly through the role of WE as a mediator. The better the PsyCap the lecturer possesses, the higher the lecturer’s readiness to face change. Likewise, the greater the organizational support lecturers feel in their work and life, the better their readiness for change will be. Apart from influencing RTC, it was found that confirmed PsyCap and POS were able to be positive predictors of WE. The mediating role of WE on the influence of PsyCap and POS on RTC is proven, where lecturers who have good WE will be better prepared to face change. So, it can be concluded that increasing lecturer WE can be done by strengthening PsyCap and increasing POS, and in the end, it will have a positive impact in reducing resistance and increasing RTC in the phase of change.

6.1. Theoretical implications

The concept of change management in this study relates to readiness to change and openness to change, which is the same concept as resistance or resistance to change, which is analogous to Lewin’s theory of the stages of unfreezing and creating readiness to change. This study provides broad theoretical implications and enriches the human resource management literature, particularly in the context of organizational change. This study found that the positive concept of organizational behavior (Luthans, Citation2002; Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, Citation2017) reflected in PsyCap strongly predicts readiness to change. This research is empirical evidence that individual and organizational factors can shape attitudes and encourage organizational members to accept change. PsyCap and WE as individual factors are proven to promote readiness to change together with organizational supporting factors. In the theory of the JD-R model, WE becomes an outcome that affects performance at work and contributes to the behavior of openness to change (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2008; Kahn, Citation1990). Employee reactions to change are shaped by personal psychological resources and their perceptions of the organizational environment. Social Exchange Theory (SET) provides the basis for perceptions of organizational support. SET refers to the norm of reciprocity between employees and the organization where they feel obligated to pay good performance to the organization when they get optimal resources (Saks, Citation2006). They take responsibility as agents of change by being adaptive to changing conditions and proactively anticipating new challenges (Ghitulescu, Citation2012; Kirrane et al., Citation2017). Employees with high WE become more adaptable than employees with low WE (Raditya et al., Citation2021). Fairness, the well-being provided by the organization, and recognition for their contribution can reduce stress and the adverse effects of physical and emotional energy drain during organizational change (Kurtessis et al., Citation2017; Turgut et al., Citation2016). Employees with work engagement are more energetic and connected to work. They will cope better with work demands and not give up quickly, so they view the change process as positive (Matthysen & Harris, Citation2018).

This research digs deeper into the role of WE as a mediator who can enhance readiness and openness to change. WE’s role as a mediator can achieve the influence of PsyCap and POS in increasing RTC. Increasing the readiness of lecturers to change can be accompanied by increased psychological capital, work engagement, and organizational support, which impact the higher level of lecturers’ readiness to change. This finding builds on previous studies that emphasize how important it is for employees to support organizational change. Individual perspective, organizational support, and managerial commitment are important components influencing readiness to change (Armenakis et al., Citation1993; Holt et al., Citation2007; Rafferty et al., Citation2013).

6.2. Managerial implications

The results of this study may ultimately contribute to practical managerial implications for universities. First, the readiness of lecturers to change is influenced by internal factors that come from individuals, namely PsyCap and WE. Strengthening PsyCap and increasing WE lecturers can support lecturers’ ability to accept and adopt organizational changes. Training programs that aim to improve knowledge, skills, and attitudes help add insight regarding PsyCap to increase work engagement and apply this PsyCap in their work.

Second, the organization needs to provide optimal support. This support can be in the form of moral or material. Superiors can give moral support with empathy, strong tolerance, and respect for the lecturer’s ideas/work. Conversely, material support can be provided by giving awards and prizes as an incentive for the lecturer’s best achievements and performance. This organizational support can increase the engagement of lecturers in their work. Finally, they will be ready to try to deal with change. Organizational support and work engagement increase lecturers’ confidence in the positive side of change, so they are not worried about the future and believe that changes must be made and cannot be avoided.

6.3. Limitations and recommendations

This research has limitations because it examines the change in general and has not explicitly identified the type of organizational change. Future studies expect to be able to divide clusters of changes such as technological changes, policy changes, or cultural changes. Then, this research is limited to only measuring the role of PsyCap, POS, and WE in predicting RTC. To improve and explore the topic of organizational change, especially human resource development and organizational behavior, developing research models by combining other variables is a challenge.

Future research might evaluate proactive personality to enhance change readiness. Proactive employees perceive technology as providing opportunities for innovation and digital transformation. Employees’ willingness to adapt to digital changes in the workplace demonstrates their technology readiness (Hamid, Citation2022). Furthermore, emotional intelligence also has the potential to impact RTC. Emotional intelligence is essential for ensuring employees support organizational changes and display a positive attitude toward change. It helps them assess their thoughts and interests to build the appropriate attitude toward the changes occurring in the organization. When change is critical, it also enhances emotional loyalty and feelings of accomplishment (Gelaidan et al., Citation2018).

Additionally, future research might evaluate the role of servant leadership in supporting or making employees grow as persons and professionals, which should be favorable to their readiness to change. Servant leadership is a strategy framework that seeks to address potential adverse effects, such as employee stress and emotional well-being, which may arise during periods of organizational transition characterized by turbulence, ambiguity, and unpredictability (Jiménez-Estévez et al., Citation2023). Moreover, other personal resources, such as mindfulness, can be an antecedent of RTC. Mindfulness is critical in fostering organizational flexibility and resilience in the face of disruptive waves (Ruiz-Palomino et al., Citation2023).

Finally, the data collection method used in this research is a cross-sectional questionnaire. It means that the questionnaire collects data from lecturers at a single time. Therefore, this research design does not allow analysis of changes in lecturers’ attitudes over time. There was no way to compare attitudes from an earlier time point to a later time point. Future research could improve this limitation by incorporating a longitudinal component into the research design. It may involve using additional data collection methods beyond questionnaires, such as interviews, at some times. It will allow researchers to qualitatively document how lecturers’ attitudes may develop over time as changes occur in the university environment. Having both cross-sectional questionnaire data and longitudinal interview data will provide the most complete picture of how faculty attitudes are shaped and changed.

PIS.docx

Download MS Word (77.8 KB)About_the_authors.docx

Download MS Word (77.8 KB)Table_Construct_Reliability_Test.docx

Download MS Word (20.9 KB)Research_Questionnaires.docx

Download MS Word (19.2 KB)Acknowledgments

This study was carried out in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD degree earned by the first author [L.M.] at the Universitas Negeri Jakarta in Jakarta, Indonesia. Additionally, the authors would like to express their gratitude to the research organization for their assistance in enabling the data collection process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available on request from the first author [L.M]. The data are not publicly available due to the privacy of research participants.

Supplemental material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2290616

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lista Meria

Lista Meria is a lecturer at the Faculty of Economics and Business at Universitas Esa Unggul, Indonesia. She is also a doctoral student in the Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Indonesia postgraduate program. Her research interests include human resources management.

Corry Yohana

Corry Yohana is a professor of management at the Faculty of Economics at Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Indonesia. Her research interests include human resources management and higher education.

Unggul Purwohedi

Unggul Purwohedi is an associate professor in management at the Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Indonesia. His research interests include human resources management.

References