Abstract

Employee resilience is closely linked to well-being, happiness, and workplace performance. Many studies have suggested a connection between mindfulness and employee resilience. However, a notable distinction arises between Eastern spiritual mindfulness and Western scientific mindfulness, prompting an investigation into the specific elements of each perspective that contribute to supporting employee resilience. This study aims to clarify whether Eastern mindfulness, characterized by awareness and attention, or Western mindfulness, characterized by qualities like novelty seeking, novelty producing, and engagement, exerts a more apparent influence on enhancing employee resilience. Furthermore, it seeks to explore any correlation between Eastern spiritual mindfulness and Western scientific mindfulness. This research employs a mixed-method approach utilizing critical incident analysis to gain profound insights of mindfulness perspectives. Furthermore, it applies structural equation modeling to rigorously examine the relationship between mindfulness and employee resilience. The findings reveal a positive association between Eastern and Western mindfulness. Surprisingly, while Eastern mindfulness does not directly impact on employee resilience positively, Western mindfulness demonstrates a favorable effect on employee resilience. Moreover, Western mindfulness emerges as a mediator in the relationship between Eastern mindfulness and employee resilience. This study contributes to both theoretical and practical realm of knowledge. Additionally, it acknowledges its limitations and offers recommendations for future research.

Keywords:

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Presently, organizations frequently find themselves confronted with unexpected events and heightened pressures. It is inevitable for organizations to face crises. Simultaneously, employees are navigating through unprecedented times. Significant and rapid changes in the external environments of military operations have a negative effect on the mental health and psychological well-being of personnel, according to Metwally and Ruiz-Palomino (Citation2022). Adverse life circumstances, such as pandemics, can have a significant effect on a person’s mental health and psychological well-being. Challenging life events, including pandemics, can substantially impact an individual’s mental health and psychological well-being. Stress, anxiety, confusion, isolation from others, and depression are some such effects (Yıldırım & Arslan, Citation2022). Various stressors, originating from both internal and external environments, have the potential to exert an impact on employees. An illustration of this can be seen in the manner in which the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the daily operations, well-being, and mental health of personnel within a substantial number of organizations. According to Jiménez-Estévez et al. (Citation2023), the COVID-19 pandemic is a common stressor that organizations encounter, particularly in the hotel sector. This is because the industry encountered substantial operational disruptions as a result of evolving consumer behaviors, health and safety protocols, and travel limitations. The employees’ stress levels were intensified in this environment, characterized by rapid change and uncertainty, which posed a risk to their job stability and overall welfare.

Although our study discusses the COVID-19 pandemic as a contextual background, it is important to acknowledge that organizations regularly encounter a wide range of stressors, including economic downturns and natural disasters. The findings obtained from this research are relevant for promoting resilience and mindfulness in the face of different challenges, thus ensuring their usefulness extended beyond the specific circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic. The extreme circumstances have distinctly added to the stress experienced by employees through multiple direct and indirect channels, greatly effecting their mental health, work-life balance, and overall state of well-being.

Employee resilience refers to the ability to maintain a healthy level of well-being after experiencing unexpected events and it is closely intertwined with well-being itself (Harms et al., Citation2018). Research has demonstrated that employee resilience has a direct, positive impact on organizational resilience, and is inversely related to employee stress and burnout (Chen et al., Citation2017; Kuntz et al., Citation2016). Resilient employees demonstrate greater responsiveness to organizational changes and possess a higher capacity to recover from unforeseen circumstances compared to their non-resilient employees (Shin et al., Citation2012). Hougaard et al. (Citation2020) have suggested that building mental resilience through mindfulness during times of crisis is an effective approach to overcoming difficult situations.

Mindfulness is recognized for its enduring and extensive effects. It is considered an effective strategy for navigating crises (Bearance, Citation2014) for managing and responding to adversity. Engaging in mindfulness practices has been linked to improved decision-making (Fiol & O’Connor, Citation2003), increased psychological flexibility (Hayes & Feldman, Citation2004), and an enhanced ability to perceive events objectively (Shapiro et al., Citation2006). Both resilience and mindfulness share similar characteristics in responding to challenging circumstances. However, research exploring the connection between mindfulness and resilience remains limited (Brown & Ryan, Citation2003; Grafton et al., Citation2010; Rivoallan, Citation2018; Thompson et al., Citation2011).

The conceptual definition of mindfulness has continuously evolved and differs in revised Eastern spirituality as opposed to Western scientific thought. This study distinguishes between the interpretations of mindfulness as viewed from the perspectives of Western scientific and Eastern spiritual frameworks, instead of directly comparing the mindfulness practices of Western and Eastern cultures. The objective of this research is to examine how different conceptualizations, each focusing on mindfulness in their own approach, contribute to the resilience of employees in the same group of participants.

Understanding these relationships will enable the application of appropriate tools to enhance employee resilience, thereby promoting well-being and job satisfaction within organizations. illustrates the theoretical framework of this study.

2. Theoretical background and hypotheses

2.1. Eastern and Western perspectives of mindfulness

The concept of mindfulness varies between Eastern and Western teaching and belief. In Eastern traditions, mindfulness originates from the Pali language word ‘sati’, which refers to awareness, attention, and conscious presence of mind (Bodhi, Citation2000). According to Kabat-Zinn (Citation2003), mindfulness is a psychological notion that is derived from purposefully focusing on the present moment objectively while allowing the experience to change moment by moment. Furthermore, Brown and Ryan (Citation2003) defined mindfulness as the intentional act of focusing one’s attention and being fully aware of the current situation. Eastern mindfulness refers to the capacity for non-judgemental awareness and focused attention in the present moment.

Conversely, In the Western perspective, Ellen Langer (Citation1989) introduced an alternative concept of mindfulness as an ‘active information processing’ mode (p. 138). Mindfulness in the Western context stands in contrast to mindless behavior; it represents a state of being present with heightened awareness, leading to increased sensitivity to one’s surroundings, openness to new information, the creation of new perceptual categories and an enhanced awareness of different perspectives in problem-solving (Langer & Moldoveanu, Citation2000).

To summarize, Eastern mindfulness establishes practices in line with meditation (Bishop et al., Citation2004; Kabat-Zinn, Citation2003), and focuses on inner experiences, non-judgmental observation, and the internal processes of mind and body (Didonna, Citation2009). Conversely, Western mindfulness emphasizes awareness of external events and goal oriented cognitive processes (Baer, Citation2003) through an active information processing mode, leading to novel distinctions, creativity, and effective problem-solving (Langer, Citation1989; Langer & Moldoveanu, Citation2000; Pirson et al., Citation2015).

Djikic (Citation2014) highlighted significant differences in the operational definitions of Eastern and Western mindfulness, including problem formulating, causes of problems, and proposed solutions. Ivtzan and Hart (Citation2016) suggested that various aspects of Eastern and Western mindfulness, including the philosophies, components, measurement tools, goals, and interventions, show differences. However, they identified three aspects where there is some degree of convergence: the definitions, type of outcomes, and self-regulation as a key mechanism. Weick and Putnam (Citation2006) asserted that Eastern wisdom and Western knowledge are mutually reinforcing. Singhatong et al. (Citation2022) suggested that neither perspective alone is adequate for comprehensive understanding of the influence and applicability of mindfulness in organizations. Lee and Jang (Citation2021) demonstrated that the meditative mindfulness (Eastern mindfulness) and sociocognitive mindfulness (Western mindfulness) are positively correlated with each other, and positively associated with positive achievement emotions and academic outcomes.

Despite these insights, empirical evidence regarding the link between Eastern spirituality and Western scientific mindfulness remains limited. In this paper, the researchers aim to bridge this gap by conducting an empirical study to quantify the association between Eastern and Western mindfulness using the concept of mindfulness spectrum.

2.2. Mindfulness spectrum

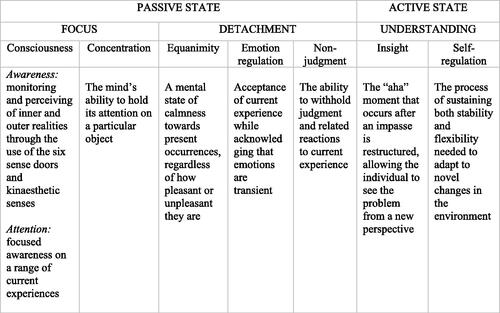

Buranapin et al. (Citation2016) introduced the concept of the mindfulness spectrum by merging the two definitions of mindfulness found in Eastern spirituality and Western science. This concept explains the process of mindfulness and an individual’s capacity to perform effectively in dynamic and novel situations through different states of the mind, ranging from the passive Eastern perspective to the active Western perspective. They proposed that the Eastern perspective emphasis the internal mind and body processes, whereas the Western perspective applies to fostering creativity, goal-orientation thinking, and problem-solving. Despite their differences, both perspectives complement each other across all dimensions of the mindfulness spectrum. The mindfulness spectrum explains the progression of the quality of one’s mental state, which continuously interacts – spanning from passive states associated with experiential awareness (Eastern mindfulness) to active states which create novel distinctions and insights (Western mindfulness). illustrates the two states of the mindfulness spectrum.

Figure 2. The mindfulness spectrum. Note: Reprinted with permission from ‘The mindful spectrum: Merging Eastern and Western Perspectives on Mindfulness.’ By Siriwut Buranapin, Wanlanai Saiprasert and Saifon Singhatong, 2016, Academy of Management Proceedings, , page 29.

The mindfulness spectrum involves two states (passive, and active) and three categories (focus, detachment, and understanding).

In the passive state, firstly, the focus category is on consciousness (i.e. awareness and attention), and concentration. Secondly, the detachment category are equanimity, emotional regulation, and nonjudgment. The primary function is to observe internal and external experiences while detaching from past and future expectations. This state prepares the mind for mental interaction, which leads to decision-making and problem solving in the active state. This state involves the understanding category like insight and self-regulation, allowing individuals to see problems form new perspectives and adapt to changes in their environment. It aligns with Langer’s Western perspective of mindfulness, emphasizing attentiveness, and openness to new information, creating new categories for perception, focusing on the present, heightened environmental sensitivity, and improved problem-solving abilities (Langer, Citation1989).

However, the mindfulness spectrum is a conceptual framework, which currently lacks empirical testing and evidence regarding its practical application. To explore the connection between Eastern spirituality and Western scientific mindfulness, we propose:

Hypothesis 1: Eastern mindfulness is positively related to Western mindfulness.

2.3. Psychological capital

Psychological Capital theory (PsyCap), introduced by Luthans (Citation2002) serves as a core construct of positive organizational behavior (POB). Positive organizational behavior is described as ‘the study and application of positively oriented human resource strengths and psychological capacities that can be measured, developed, and effectively managed for performance improvement in today’s workplace’ (Luthans, Citation2002, p. 59).

PsyCap is a concept that has gained significant attention in the fields of positive psychology and organizational behavior. Luthans et al. (Citation2006) defined PsyCap as an individual’s positive psychological state and consists of four essential components: (1) Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their own ability to effectively completed tasks and overcome obstacles; (2) Hope involves setting clear goals, devising strategies to achieve those goals, and having the determination to pursue them; (3) Optimism entails having a positive perspective on the future, anticipating favourable outcomes, and expecting positive events to occur; (4) Resiliency refers to the capacity to recover quickly from adversity or setbacks. Resilient individuals can maintain their psychological well-being even when facing difficult situations. Importantly, the notion of resiliency in PsyCap theory is the foundation of employee resilience.

2.4. Employee resilience

The concept of employee resilience, as developed by Näswall et al. (Citation2013), draws upon the foundation of resilience in Psychological Capital (PsyCap) theory. Employee resilience is defined as the capacity of employees, supported by the organization, to effectively utilize resources in order to manage, adapt to, and grow in response to changing work conditions. This study emphasizes that employee resilience manifests as workplace behavior within the organizational context.

Näswall et al. (Citation2015) suggested that employee resilience differs from individual resilience in three ways; (1) workplace behavior: Employee resilience is described in terms of workplace behaviors rather than attitudes and beliefs, (2) organizational support: organizations play a crucial role by providing resources that influence the achievement of employee resilience bahaviors, and (3) universal applicability: resilient behavior can be cultivated and achieved in any work environment develop and be achieved in any work environment

Previous research on individual resilience has demonstrated a positive relationship between employee resilience and various desirable outcomes, including well-being, creative behavior, work behavior, job performance, job satisfaction, work happiness, and organizational commitment (Gifford & Young, Citation2021; Luthans, Citation2002; Luthans et al., Citation2005, Citation2007; Luthans & Youssef, Citation2004; Youssef & Luthans, Citation2007). Resilient employees are better equipped to adapt to unexpected challenges and contribute to enhanced organizational performance. Consequently, the cultivation and support of employee resilience are of outstanding importance.

2.5. Mindfulness and employee resilience

Mindfulness is the examination of how individuals efficiently deal with problems in unpredictable conditions (Frigotto & Narduzzo, Citation2017). Personal awareness is associated with an individual’s ability to handle unexpected events and unfamiliar settings (Brown et al., Citation2007). People differ in their degrees of psychological consciousness and their capacity for mindfulness. When confronted with adversity, individuals with lower mindfulness scores are less likely to spend time reflecting on the situation (Rees et al., Citation2015). A correlation of resiliency and mindfulness is positive, as studied by Kemper et al. (Citation2015) and Montero-Marin et al. (Citation2015). Mindfulness has a substantial impact on promoting resilience (Slatyer et al., Citation2017). Practicing mindfulness can result in effective handling of unforeseen circumstances (Weick & Sutcliffe, Citation2007). Mindfulness has been linked to a decrease in burnout and an increase in resilience, according to Olson et al. (Citation2015).

Good et al. (Citation2016) proposed that mindfulness contributes to resilience development in several ways, including (1) fostering recovery from toxic events by providing a more detached perspective (Bishop et al., Citation2004); (2) fostering growth in the face of adversity by experiencing threat and flexibility (Neff & Broady, Citation2011); and (3) recovery with positive emotion (Fredrickson, Citation2000). Darwin and Melling (Citation2011) argued that mindful competence assists military commanders in enhancing their in unexpected situations. Hyland et al. (Citation2015) suggested that mindfulness may help employees cope with organizational change by making them more observant, attentive, and open to new ways of doing things when learning new skills.

Recent studies have consistently shown a positive association between mindfulness and resilience, including among physical educators (Lee et al., Citation2021), university students (Asthana, Citation2021; Liu et al., Citation2022), and nurses (Wu et al., Citation2022). At the organizational level, Buranapin et al. (Citation2023) discovered that mindful organizing positively impacts organizational resilience. However, the question remains unanswered regarding the effects of Eastern or Western mindfulness on employee resilience, therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 2: Eastern mindfulness has a positive impact on employee resilience.

Hypothesis 3: Western mindfulness has a positive impact employee resilience.

2.6. Mindfulness as a mediator

Most studies examining the relationship between Eastern and Western mindfulness have primarily taken a qualitative approach. The role of Western mindfulness as a mediator in the connection between Eastern mindfulness and employee resilience has not been directly investigated to date. However, previous research has identified specific Western mindfulness subscales, such as novelty seeking, novelty producing, flexibility, and engagement, as mediators for various constructs.

For instance, Lin (Citation2020) proposed suggested that the four subscales of Western mindfulness serve as mediators between psychological capital and the engagement of university students in English learning. In other studies, novelty has been identified as a mediator in the relationship between experience and positive emotion (Mitas & Bastiaansen, Citation2018), while engagement has been shown to mediate the relationship between resilience and job performance (Kašpárková et al., Citation2018). Employee engagement has also been found to mediate relationships between work place spirituality and mental health, as well as between organizational justice and mental health (Sharma & Kumra, Citation2020). Additionally, a recent study revealed that engagement and employee resilience act as mediators between human resource management practices and service provider commitment in the context of green hospitality (Arasli et al., Citation2020).

This study represents the first attempt to explore the relationship between Eastern mindfulness and employee resilience, utilizing Western mindfulness as a mediator. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 4: Western mindfulness mediates the relationship between Eastern mindfulness and employee resilience.

3. Research methodology

In this study, an exploratory sequential mixed-methods research design was employed to gather and analyze data, following the approach outlined by Creswell and Tashakkori (Citation2007). Qualitative research aims to attain a deeper understanding of phenomena (Patton, Citation2002) and places a strong emphasis on achieving information saturation (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994). Conversely, quantitative research addresses research questions related to causality and generalisability (Fetters et al., Citation2013). Creswell (Citation2003) suggested that mixed methodology aids in interpreting and gaining more comprehensive understanding of the complex reality of any given situation, together with the implications derived from quantitative data.

Initially, qualitative data collection and analysis were conducted using the critical incident technique (CIT) to explore the relationship between Eastern spiritual mindfulness and Western scientific mindfulness. The CIT, originally developed by Flanagan (Citation1954) as part of the US Army Air Force’s aviation psychology program during World War II, has been effectively adapted for job analysis through expert observation. The CIT comprises five steps: (1) identifying general aims, (2) planning and setting specifications, (3) collecting data, (4) analysing data, and (5) interpreting data and reporting results. The CIT has become a widely utilized qualitative method and an efficient exploratory and investigative tool (Butterfield et al., Citation2005). It has found application in various disciplines, including management (Baker & Kim, Citation2020; Breuer et al., Citation2020; SeokChai et al., Citation2019); marketing (Shankar et al., Citation2020; Yilmaz, Citation2018; Zhang & Wang, Citation2018) education and teaching (Anderson et al., Citation2020; Philpot et al., Citation2021; Wass et al., Citation2020); and healthcare (Keers et al., Citation2018; Wennman et al., Citation2022). The CIT has also been recently used in research focusing on unexpected situations, such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Durosini et al., Citation2021; Kurotschka et al., Citation2021; Voorhees et al., Citation2020). Serrat (Citation2017) proposed that the CIT can transform complex experiences into rich data and in-depth information, particularly when data are collected anonymously. Given its capacity to provide insights into how executives navigate unexpected situations through mindfulness, the CIT was crucial and appropriate for the study.

Subsequently, quantitative data collection and analysis were undertaken to examine the measurement and analysis of causal relationships between mindfulness from different perspectives and employee resilience. The variation in data collection and analysis contributed to the overall validity of this study.

In the methodology of this study, rigorous ethical standards were upheld to ensure the dignity, rights, and welfare of all participants. Before the commencement of the research process, informed consent was obtained from all individuals participating in the study. This consent process involved providing participants with comprehensive information about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits, as well as the confidentiality of their responses. Participants were assured of their right to withdraw from the study at any point without penalty.

All consent forms, whether written or verbal, were securely stored in accordance with data protection regulations to maintain participant confidentiality. The consent procedure was approved by the Chiang Mai University Ethics Committee, ensuring adherence to international ethical guidelines and standards for research involving human participants. This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and received ethical approval from the Chiang Mai University Ethics Committee, under the protocol code CMUREC 63/197, with the approval date being 6 October 2022.

3.1. Qualitative phase

3.1.1. Participants

The interview participants were purposefully selected using the criterion-based selection method. In the qualitative phase, the chosen participants are considered key informants who experienced a critical incident in various types of businesses within their organizations. Participants in selected organizations in this study must have experience making critical decisions that significantly impact organizational financial performance, employee well-being, or the organization’s reputation and image.

The careful selection of appropriate participants is crucial, as it allows us to gain insights into how executives manage unexpected situations with mindfulness based on their learning experiences. Morse (Citation2000) suggested that the more valuable data collected from each person, the fewer participants are required. She emphasized the importance of aligning the sample size with the study’s scope, the nature of the topic, data quality, and study design. Creswell (Citation1998) recommended five to 25 samples for phenomenological studies. Palinkas et al. (Citation2015) suggested that the sample size should be determined by the type of analysis proposed, such as conducting interviews with three to six participants in a phenomenological study.

In this phase of the research, we interviewed 10 high-level executives from various organizations based in Thailand, including hospitals, the Royal Thai Police, the liquid petroleum gas terminal, and manufacturing, wholesale, retailing, service, media, and educational institutions. provides a descriptive summary of organizations, participants, and critical incidents.

Table 1. Descriptive summary of organizations, participants, and critical incidents.

3.1.2. Data collection

Ten participants underwent in-depth, semi-structured interviews, each lasting approximately two hours. At the beginning of the interviews, participants were provided with an overview of the study’s objectives and a definition of what constituted a critical organizational incident. They were then asked to introduce themselves, detailing their background, position, role, and responsibilities within their organizations. Subsequently, participants were prompted to recall an experience involving unexpected circumstances, specifically focusing on the cause process, and sequence of events that they could recall vividly. They were encouraged to elaborate on these critical incidents and describe how they managed them.

In cases where the essential aspects of mindfulness were no spontaneously mentioned during the interviews, additional questions were posed to elicit this information:

Did you actively monitor and perceive the unexpected situation? If so, how did you go about it? (Eastern mindfulness)

Were you specifically focused on the unanticipated circumstances? (Eastern mindfulness)

Did you find ways to adapt to novel changes that arose during the unexpected event? If so, how did you manage this adaptation? (Western mindfulness)

Can you describe your approach or attitude toward actively engaging with the unexpected situation? (Western mindfulness)

3.1.3. Data analysis

All interviews and discussions conducted using the critical incident technique were recorded and transcribed for the purpose of interpretation. Transcriptions were created verbatim from audio recordings, capture both verbal and non-verbal expressions. The data were analysed using thematic analysis, a flexible method for identifying, analysing, and reporting themes which yields a rich and detailed understanding of the data. In this study, we employed a deductive approach to thematic analysis, which involved utilizing a predefined list of themes derived from existing literature and knowledge.

The six steps of thematic analysis were followed: (1) data familiarisation, (2) coding, (3) theme generating, (4) theme review, (5) theme defining and naming, and (6) reporting (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). We began by gaining a comprehensive overview of all data by transcribing the interviews verbatim, followed by careful reading and note-taking. Subsequently, we conducted data coding, where each code described the relevant main idea. The data were then organized into groups based on these codes to gain an overview of the main points. Theme were formulated by combining multiple codes and were named based on the concepts of Eastern and Western mindfulness.

During this phase, CIT was used to explore the experiences of executives and gain a deeper understanding of the theoretical constructs under investigation. Eastern mindfulness, representing a passive state, was characterized by awareness and attention – qualities that involved continuously monitoring and perceiving the environment while focusing awareness on various experiences (Brown & Ryan, Citation2003). In contrast, the core components of Western mindfulness, reflecting an active state, including (1) novelty seeking – curiosity and openness towards the environment, (2) novelty producing – the ability to create new categories, (3) flexibility – the ability to adapt to novel changes in the environment, and (4) engagement – the attitude towards an active interaction with the environment (Langer, Citation2004).

Through the interviews, associations between Eastern and Western mindfulness were identified. For instance, when a hospital director faced an unexpected situation, he draw upon elements of both Eastern and Western mindfulness to manage the issues effectively. He also emphasized the importance of teaching employees to apply mindfulness in problem-solving situations.

When we face a crisis or problem. If we are mindful, aware (awareness), and analyse (novelty seeking), we will know what we should do. Awareness should be in every process. When facing a problem, the leader must be aware, remind staff to be mindful, and meet with the team mindfully (engagement). For example, I always tell our employees that when facing patient dissatisfaction, we must be mindful in communication, aware, attending, and listening. Do not retaliate (awareness, attention)… In each situation, our decision making is not always correct; if it is wrong, review it and make a new decision; if it is correct, make it better (flexibility).

Similarly, the police deputy commissioner highlighted the role of mindfulness in police work, particularly when dealing with unexpected and potentially dangerous events. Concentration and awareness were deemed essential for making critical decisions rapidly.

When we work, police must use judgment, knowledge, and capability, and they should notice things that are not normal. We often face unexpected events such as major accidents, how we manage them (engagement)… Normally, police must face dangerous and unexpected events. So, mindfulness is an important thing in police work. We must notice, attend, and be aware of the situation around us (awareness, attention) whether something is abnormal… In case of emergency, we have only three seconds for the decision whether shoot or not; therefore, concentration is essential (attention).

The managing director of the manufacturing company shared his approach to resolving a severe crisis, which involved a combination of awareness, immediate action, analysis, negotiation, and compromise.

We faced a severe crisis. If we could not sell to this big customer, our company would have closed. Firstly, we must be conscious, calm, and mindful (awareness, attention). Then, we must react immediately (engagement) and analyse the problem (novelty seeking). I tried to find the solution, negotiate and compromise with the customer (novelty producing). If customers thought that we were sincere, they were pleased to negotiate.

Likewise, a private school director discussed how mindfulness played a vital role in responding to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, emphasizing the need for attention, problem analysis, adaptability, and continuous innovation.

When COVID-19 emerged, it impacted our school business. We had never stopped teaching; everyone did not think that this would happen. We concentrated (attention) and divided it into types of problems and thought about how to solve these problems; process, procedure, management, communication, teaching (novelty seeking)… We adjust the curriculum, develop IT (flexibility) to support teaching, develop a new website and continuously create content (novelty producing)… We prepare and arrange because we don’t know when COVID-19 will be finished, nobody can know, if we don’t analyse the problem clearly, we may not have good luck (engagement).

These interviews collectively underscored the executives’ belief in the pivotal role of mindfulness during crises and revealed a connection between Eastern and Western mindfulness concepts. To comprehensively address all research objectives, this study integrated CIT with quantitative methods in the subsequent phase. Employing mixed methods in this study, specifically methodological triangulation, enhances the validity of research findings by utilizing multiple data collection approaches.

3.2. Quantitative phase

3.2.1. Sample and procedures

The sample for this study comprised 783 individuals, including executives, managers, and employees from 21 organizations in Thailand. The paper questionnaire developed specifically for this study was administered to respondents who had experienced an organizational crisis. Data collection took place from November 2020 to December 2021. A total of 764 questionnaires were collected; however, 25 samples were excluded due to incomplete, incorrect, or outlier responses. As a result, 739 usable questionnaires, accounting for 94.38% of the collected data, were included for analysis in this study. Detailed demographic characteristics of the participants can be found in .

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of the participants (n = 739).

3.2.2. Measurement of variables

The questionnaire used in this study, written in Thai, consisted of three parts: Eastern mindfulness, Western mindfulness, and employee resilience. Each part is described below.

3.2.2.1. Eastern mindfulness

Eastern mindfulness, representing mindfulness in a passive state, was assessed using The Mindfulness Awareness Attention Scale (MAAS). This unidimensional scale captures the essence of Eastern mindfulness, characterized by (1) awareness or monitoring and perceiving of inner and outer realities through using the six sense doors and kinaesthetic senses and (2) attention, or focused awareness on a range of current experiences. The MAAS, designed by Brown and Ryan (Citation2003), consists of 15 items and is the first widely used measure of mindfulness. The tool is well recognized for its ability to assess mindfulness by examining individuals’ attention to or disregard of their thoughts, emotions, bodily sensations, and activities (Sauer et al., Citation2013). It is distinguished by robust measurement qualities, including a consistent unidimensional structure. Research conducted by multiple international groups has substantiated the dependability of this unidimensional framework (MacKillop & Anderson, Citation2007). The mindfulness scale is commonly used since it is short and strongly reliable, allowing it to be applicable in both clinical and nonclinical settings (Medvedev et al., Citation2018). The MAAS meets the unidimensionality assumption and its items exhibit internal validity between acceptable to very good level (Morera & Stokes, Citation2016), with a Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.78 to 0.92. Respondents rated the items on a six point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = almost always to 6 = almost never with the scale scores computed as the mean of the 15 items. It has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, including positive overall quality rating in systematic reviews of self-reported mindfulness instruments (Park et al., Citation2013). Most studies confirmed validation of the MAAS (Carlson & Brown, Citation2005; MacKillop & Anderson, Citation2007; Van Dam et al., Citation2010).

3.2.2.2. Western mindfulness

To measure mindfulness in the active state from a Western perspective, which emphasizes understanding, including (1) insight (the ability to see problems form new perspectives) and (2) self-regulation (the ability to sustain stability and flexibility needed to adapt to novel environmental changes), the Langer Mindfulness Scale (LMS-14) was employed. The LMS-14 based on Langer’s construct of mindfulness (from the Western perspective) on the mindfulness spectrum. Originally, the scale contained 21 items and four subscales (novelty producing, novelty seeking, engagement, and flexibility). However, due to concerns about reliability and model fit (Haigh et al., Citation2011), a new 14-itme version (LMS-14) with three subscales was developed by Pirson et al. (Citation2015), omitting the flexibility subscale. The LMS-14 has been translated and validated cross culturally in multiple languages, demonstrating high internal consistency (Haller, Citation2015; Leong & Rasli, Citation2013; Moafian et al., Citation2017; Pagnini et al., Citation2018). Yang et al. (Citation2023) validated the Langer Mindfulness Scale Japanese version (LMS-J), confirming its reliability and validity for assessing socio-cognitive mindfulness in Japan. In the present, the LMS -14 is widely used in numerous research studies. Guan et al. (Citation2024) adopted the LMS -14 to measure participants’ trait mindfulness. Quang and Thuy (Citation2024) modified the LMS -14 to test a model of mindfulness affecting loyalty (return intention and word of mouth) with the mediating role of customer experience. The scale were rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree with higher scores indicating greater mindfulness. Pirson et al. (Citation2012) demonstrated good internal validity of LMS -14 with overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83 and acceptable model fit indices from CFA of the four-factor structure. They also compared LMS-14 with MAAS and established discriminant validity, convergent validity (r = 0.37) and construct validity via the nomological network with other relevant construct. Siegling and Petrides (Citation2014) further found the shared dimensionality of several mindfulness scales including the MAAS and LMS-14, recognizing the multidimensional nature of mindfulness and the distinct contributions of different mindfulness scales. While there is evidence for shared dimensionality among the measures, each scale also captures specific facets of mindfulness based on its theoretical foundation and scale construction. In Ivtzan’s handbook (2020), Krägeloh emphasized the importance of recognizing the diversity in mindfulness definitions and measures, as they reflect different aspects and perspectives of the concept. Besides, Krägeloh argued that this diversity in mindfulness conceptualizations and measures contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the construct and its various applications in mindfulness research. While these works used both scales, it appears that they primarily used them for comparison and validation purposes rather than administering both scales to the same participants in a study. Until recently, Laeequddin et al. (Citation2023) investigated whether there are differences in mindfulness/mindlessness among business school students by applying Langer’s scale and the MAAS. Pagnini et al. (Citation2024) identified a significant negative correlation over time between mindfulness and stress in crew members, especially when assessed using the MAAS and the LMS-14.

3.2.2.3. Employee resilience

In this study, employee resilience (EmpRes) was measured as individuals’ resilience within an organizational context, aligning Luthans (Citation2002) definition of resilience in psychological capital (PsyCap) theory. This concept involves both the recovery process, which includes successfully coping with change and returning to the original state, and the transformational process of learning from change and adapting to thrive in a new environment. Unlike other individual resilience measurements, EmpRes encompasses the employee’s perspective within a work context, emphasizing their capacity to thrive amidst adversity. The scale was facilitated by the organization and focused on resilience in terms of employee adaptability (Hartmann et al., Citation2019; Hodliffe, Citation2014). Näswall et al. originally introduced a 14-item scale in 2013, which was later refined into a nine-item version by removing items and adjusting wording to better reflect the behavioral focus on employee resilience. This scale has demonstrated strong construct validity, discriminant validity, and criterion-related validity. Its reliability stands at 0.91 (Näswall et al., Citation2015, Citation2019). Respondents rated the items on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always, with higher scores indicating higher resilience.

3.2.3. Factor analysis

All constructs were subjected to purification through both exploratory (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

3.2.3.1. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

EFA was employed initially to identify underlying factors explaining the pattern of correlations among observed variables before conducting CFA. A sample size of 100 was used for EFA, as it recommended to have at least 100 samples for factor analysis (Gorsuch, Citation1983; MacCallum et al., Citation1999). The suitability of the data for factor analysis was assessed by checking whether they met the minimum standard, which included the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The KMO values for all measures ranged from 0.820 to 0.870, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significance at p < 0.05, indicating that the data were suitable for factor analysis. This study also tests assessed validity and reliability. Average variance extraction (AVE) was employed to check validity; AVE value should exceed 0.50 to be adequate for convergent validity, indicating that a latent variable explains at least half of the indicator’s variance (Hair et al., Citation2010). To test discriminant validity, the square root of the AVE of each construct should be greater than inter-construct correlations (Fornell & Larker, 1981). Composite reliability (CR) is a measure of internal consistency in scale items; it is equal to the total amount of true score variance relative to the total scale score variance (Brunner & SÜβ, Citation2005). In exploratory research, a CR value between 0.60 and 0.70 is acceptable, while in a more advanced stage the value must be >0.70 (Hair et al., Citation2021). EFA was conducted in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). High factor loadings from each instrument were retained for use in CFA.

EFA of the 15-item MAAS, measuring Eastern mindfulness, revealed one component explaining 59.24% of the variance. Convergent validity was assessed using factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). Four MAAS items (EMP7, EMP8, EMP9, and EMP10) with high factor ladings were selected for consistency. These four items explained 68.98% of the variance, surpassing the recommended 60% of Hair et al. (Citation2010). Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.845.

EFA of the LMS-14, measuring Western mindfulness, identified two components (novelty producing and seeking, and engagement) explaining 49.99% of the variance. Convergent validity was assesses based on factor loading, CR, and AVE. Four novelty producing and seeking items (NP2, NP3, NS2, and NS3) and two engagement items (E1 and E3) with high factor loadings were selected for consistency. These six items explained 82.70% of the variance, meeting the acceptable threshold. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.766

EFA of the nine-item EmpRes scale, measuring employee resilience, yielded a single component explaining 47.65% of the variance. Convergent validity was assessed using factor loadings, CR, and AVE. Three employee resilience (ER2, ER3, and ER4) with high factor loadings were selected for consistency. These three items explained 75.60% of the variance. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.831. Reliability and validity analysis of variables is presented in .

Table 3. Reliability and validity analysis of variables.

3.2.3.2. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

CFA was employed to assess the measures’ validity before exploring the correlations among constructs in structural equation modeling (SEM). Five fit indices were used to evaluate model fit, including the relative chi-square (X2/degree of freedom), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR), non-normed fit index (NNFI) or the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the comparative fit index (CFI). These indices were chosen for their robustness against sample size, model misspecification, and parameter estimates (Hooper et al., Citation2008). Criteria for assessing model fit included a relative chi-square (X2/df) within the range of 2.00–5.00 (Marsh & Hocevar, Citation1985), RMSEA values of <0.05 indicate a good fit, 0.05–0.08 a fair fit, 0.08–0.10 a mediocre fit, and >0.10 a poor fit (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999; MacCallum et al., Citation1996). TLI values >0.90, CFI values close to 0.95, and the SRMR values <0.08 were considered indicative of good fit (Byrne, Citation1994).

The measurement model for MAAS yielded a good fit: X2 (1, n = 739)=2.217. X2/df = 2.217, TLI = 0.993, CFI = 0.999, RMSEA = 0.040, and SRMR = 0.009. The measurement model for LMS-14 also demonstrated a good fit: X2 (8, n = 739)=24.869. X2/df = 3.109, TLI = 0.979, CFI = 0.989, RMSEA = 0.053, and SRMR = 0.024. The measurement model for EmpRes exhibited a good fit: X2 (1, n = 739)=3.844. X2/df = 3.844, TLI = 0.987, CFI = 0.996, RMSEA = 0.061, and SRMR = 0.014. Summary of Goodness-of-fit for measurement models in this study was illustrated in .

Table 4. Summary of goodness-of-fit for measurement models in this study.

4. Results

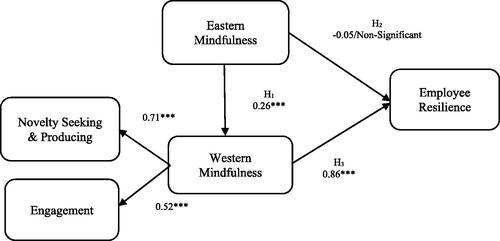

The hypothesized model in was assessed using Analysis of moment structure (AMOS) 24 software with maximum-likelihood estimation. The study’s findings reveal a statistically significant relationship between Eastern and Western mindfulness (β = 0.26, p < 0.001). Additionally, the model demonstrates a relationship between Western mindfulness and employee resilience (β = 0.86, p < 0.001). Thus, H1 and H3 were supported, while H2 did not find support, indicating that Eastern mindfulness does not have a positive impact on employee resilience.

Figure 3. Results of structural equation modeling analysis (N = 739). ***p < 0.01, Goodness of fit for structural model: X2/df = 3.133; RMSEA = 0.054; SRMR = 0.068; TLI = 0.954; CFI = 0.965.

The hypothesised model demonstrated a very good fit in all indices: X2 (60, n = 739)=187.973; X2/df = 3.133; RMSEA = 0.054; SRMR = 0.068; NNFI (TLI)=0.954; CFI = 0.965, and R-squared value of the model is 0.712.

To examine the mediation effects of H4, Hair et al. (Citation2010) suggested a series of steps for testing mediation by comparing models with and without mediation. Initially, we tested the model without mediation. The direct effect of Eastern mindfulness on employee resilience was found to be positive and significant (β = 0.17, p < 0.01). Subsequently, the second model was estimated by adding mediation. After incorporating Western mindfulness into the model, a statistically significant relationship between Eastern mindfulness and employee resilience was no longer observed. Therefore, it is concluded that Western mindfulness fully mediates the relationship between Eastern mindfulness and employee resilience, H4 was supported.

5. Discussion

This study focuses on the relationship between Eastern mindfulness, Western mindfulness, and employee resilience. Employing an exploratory mixed-method design, we set out to investigate and measure the constructs of our model. Our approach involved both qualitative and quantitative phases. In the qualitative phase, the findings unveiled intriguing links between Eastern and Western mindfulness. Moving on to the quantitative phase, most of our hypotheses, which aimed to establish correlations between constructs, found support.

Our first hypothesis, H1 was supported, affirming that Eastern mindfulness in a passive state, characterized by awareness and attention, is positively associated with Western mindfulness in an active state, encompassing novelty seeking, novelty producing, and engagement. This suggests that consciousness in a passive state of mindfulness can transform into active mindfulness, fostering creativity, curiosity, openness to the environment, and active interaction with it.

Previous research has already demonstrated the impact of mindfulness on individual resilience (Good et al., Citation2016; Kemper et al., Citation2015; Mitchell, Citation2021; Slatyer et al., Citation2017; Yuan, Citation2021). Our findings support Hypothesis 3 (H3), revealing a positive influence of Western mindfulness on employee resilience. However, Hypothesis 2 (H2), positing a direct effect of Eastern mindfulness on employee resilience, was not supported. Instead, we found that Western mindfulness mediates the relationship between Eastern mindfulness and employee resilience (H4).

This suggests that the core components of Western mindfulness, such as novelty seeking, novelty producing, and engagement, significantly impact employee resilience. In contrast, the elements of Eastern mindfulness, primarily awareness and attention, do not exert a direct influence on employee resilience. These results highlight the interconnectedness of the constructs in our study, emphasizing that Eastern mindfulness in a passive state alone may not be sufficient.

Several factors may explain why H2 was not supported. Firstly, the Eastern perspective, rooted in Buddhist teachings and religion, places its focus on the process of consciousness within the mindfulness spectrum. Secondly, the essence of Eastern mindfulness lies in the observation of current experiences and the acknowledgement of their presence without attempts to enact change. Conversely, the Western perspective, emerging from social psychology and scientific inquiry, proves to be more applicable in the dynamic work environments commonly found in workplaces (Brown et al., Citation2007; Singhatong et al., Citation2022).

Moreover, our study demonstrates that Eastern mindfulness is linked to Western mindfulness (H1) and plays a crucial mediating role (H4). This suggests that Eastern mindfulness in a passive state may serve as a prerequisite for the development of Western mindfulness in an active state.

6. Study contributions

Our study findings align with prior theoretical and empirical research on the relationship between mindfulness and employee resilience. Mindfulness has consistently been associated with positive outcomes such as enhanced well-being, job-related attitudes, and emotional intelligence at work (Aikens et al., Citation2014; Lee et al., Citation2021; Ristić & Hizarci-Payne, Citation2020). However, these studies often didn’t explore into the specifics of how mindfulness, and which facets of mindfulness, influence employee resilience.

Firstly, our study contributes to existing knowledge by bridging the gap between Eastern spiritual mindfulness and Western scientific mindfulness. We quantified the association between these two perspectives using the mindfulness spectrum concept, offering empirical evidence that complements the theoretical framework. This framework has lacked empirical validation until now.

Another theoretical contribution lies in uncovering the links between Eastern and Western facets of mindfulness and employee resilience. Ours is the first study to identify the mediating role of Eastern mindfulness in the relationship between Western mindfulness and employee resilience. While Eastern mindfulness didn’t directly impact employee resilience, it indirectly influenced it through Western mindfulness. This nuanced finding enriches the literature on mindfulness and resilience research.

In addition, our study has practical applications for enterprises. The findings provide significant knowledge to both employees and management teams, enabling them to understand the process of mindfulness and resilience. Utilizing this comprehension might be employed to strengthen staff resilience by implementing mindfulness techniques. The results of our study highlight the significance of promoting mindfulness in workplaces, which can enhance employee resilience. This, in turn, enables workers to effectively anticipate, manage, and bounce back from challenging circumstances and adversities.

To successfully enhance mindfulness within an organization, several key policies and practices are recommended:

Top management should demonstrate confidence and faith in fostering a mindfulness culture.

The management team should establish mindfulness as a core organizational value and communicate this throughout all levels of the workforce to cultivate an organizational culture of mindfulness.

Design and implement a mindfulness development system, processes, and activities that are linked to employee resilience.

Develop a work design, physical environment, and workplace atmosphere that all contribute to the growth of mindfulness at the individual, team, and organizational levels.

Establish a learning network around mindfulness infrastructure that includes the organization, other institutions, and society.

7. Limitations and future research

However, this research has certain limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, our study focused on mindfulness and employee resilience in Thailand, potentially limiting the generalizability of our results to other countries. Different cultures have unique perspectives, and Thailand’s Eastern Buddhist context may differ significantly from modern Western settings. Secondly, mindfulness is not a static trait but can change over time, influenced by experience or crises. Our cross-sectional survey examined the relationship between mindfulness and resilience at a single point in time, without considering potential changes in these variables over an extended period. Thirdly, in the context of meditation retreat practices in Buddhism, the relationship between passive and active mindfulness states is not strictly linear. Instead, these states are seen as interconnected and iterative processes of the mind. Our study captured a simplified, one-directional relationship between passive and active mindfulness. Future research should explore these intricate relationships more comprehensively. Lastly, our study primarily focused on mindfulness in an organizational context and its influence on employee resilience related to their work life. We did not extensively explore personal resilience, which would encompass an individual’s ability to bounce back after facing adversity. Investigating these diverse views on resilience would further enrich the application of resilience within organizations.

In conclusion, although research in mindfulness and resilience has significantly expanded, applying these concepts within organizational behavior still requires further exploration. Future research should address the influence of organizational culture, structure, and leadership on fostering higher levels of mindfulness and resilience. Additionally, the development of effective training programs and activities that promote these qualities within diverse organizational settings is crucial. Longitudinal studies that track the impact of mindfulness on resilience over time could provide deeper insights into this evolving relationship. Moreover, considering recent studies, such as that by Ruiz-Palomino et al. (Citation2023), which suggest that mindfulness may differentially affect organizational citizenship behaviors depending on employment status, future research should further investigate these dynamics. Their findings indicate that while permanent employees exhibit increased organizational citizenship behaviors in response to a strong person-organization fit, temporary employees demonstrate a weaker connection unless they have high levels of mindfulness. This suggests that mindfulness could potentially alleviate the uncertainties associated with temporary employment, thus fostering deeper engagement with organizational values and behaviors. Exploring these relationships in more diverse organizational settings and examining additional variables such as job type and employment duration will not only enrich our understanding of how mindfulness and employment type interact but also guide more tailored resilience-building programs that consider these crucial factors.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Siriwut Buranapin; Methodology: Siriwut Buranapin, Wiphawan Limphaibool; Formal analysis and investigation: Wiphawan Limphaibool; Writing - original draft preparation: Wiphawan Limphaibool; Writing - review and editing: Siriwut Buranapin, Nittaya Jariangprasert, Kemakorn Chaiprasit; All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Table3_Reliability and validity analysis of variables.docx

Download MS Word (13.1 KB)Table 2_Demographic characteristics of the participants.docx

Download MS Word (12.7 KB)Figures3_Results of SEM analysis.jpg

Download JPEG Image (148.9 KB)Table 4_Summary of Goodness of fit for measurement models in this study.docx

Download MS Word (12.2 KB)Table1_Descriptive summary of organizations participants and critical incidents.docx

Download MS Word (12.8 KB)Acknowledgment

The authors received no direct funding for this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary material. Raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Siriwut Buranapin

Siriwut Buranapin is an associate professor, and lecturer in the Faculty of Business Administration in Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand. His research interests include mindfulness, strategic management, and risk management.

Wiphawan Limphaibool

Wiphawan Limphaibool has graduated from Faculty of business Administration in Chiang Mai University. She is interested in mindfulness and resilience.

Nittaya Jariangprasert

Nittaya Jariangprasert is an associate professor, and lecturer in the Faculty of Business Administration in Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand.

Kemakorn Chaiprasit

Kemakorn Chaiprasit is an assistant professor, and lecturer in the Faculty of Business Administration in Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand.

References

- Aikens, K. A., Astin, J., Pelletier, K. R., Levanovich, K., Baase, C. M., Park, Y. Y., & Bodnar, C. M. (2014). Mindfulness goes to work: Impact of an online workplace intervention. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 56(7), 721–731. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000209

- Anderson, V., Rabello, R., Wass, R., Golding, C., Rangi, A., Eteuati, E., Bristowe, Z., & Waller, A. (2020). Good teaching as care in higher education. Higher Education, 79(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00392-6

- Arasli, H., Nergiz, A., Yesiltas, M., & Gunay, T. (2020). Human resource management practices and service provider commitment of green hotel service providers: Mediating role of resilience and work engagement. Sustainability, 12(21), 9187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219187

- Asthana, A. N. (2021). Organizational citizenship behavior of MBA students: The role of mindfulness and resilience. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(3), 100548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100548

- Baker, M. A., & Kim, K. (2020). Dealing with customer incivility: The effects of managerial support on employee psychological well-being and quality-of-life. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 87, 102503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102503

- Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg015

- Bearance, D. (2014). Mindfulness in moments of crisis. Revue de la Pensée Éducative [The Journal of Educational Thought], 47(1/2), 60–70. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24713052.

- Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., Segal, Z. V., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D., & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bph077

- Bodhi, B. (2000). A comprehensive manual of abhidhamma. BPS Pariyatti Editions.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Breuer, C., Hüffmeier, J., Hibben, F., & Hertel, G. (2020). Trust in teams: A taxonomy of perceived trustworthiness factors and risk-taking behaviors in face-to-face and virtual teams. Human Relations, 73(1), 3–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718818721

- Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

- Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 211–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/10478400701598298

- Brunner, M., & SÜβ, H. M. (2005). Analyzing the reliability of multidimensional measures: An example from intelligence research. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 65(2), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164404268669

- Buranapin, S., Limphaibool, W., Jariangprasert, N., & Chaiprasit, K. (2023). Enhancing organizational resilience through mindful organizing. Sustainability, 15(3), 2681. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032681

- Buranapin, S., Saiprasert, W., & Singhatong, S. (2016). The mindful spectrum: Merging Eastern and Western perspectives on mindfulness. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2016(1), 15428. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2016.15428abstract

- Butterfield, L. D., Borgen, W. A., Amundson, N. E., & Maglio, A.-S. T. (2005). Fifty years of the critical incident technique: 1954–2004 And beyond. Qualitative Research, 5(4), 475–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794105056924

- Byrne, B. M. (1994). Structural equation modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Sage.

- Carlson, L. E., & Brown, K. W. (2005). Validation of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale in a cancer population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58(1), 29–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.04.366

- Chen, Y., McCabe, B., & Hyatt, D. (2017). Impact of individual resilience and safety climate on safety performance and psychological stress of construction workers: A case study of the Ontario construction industry. Journal of Safety Research, 61, 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2017.02.014

- Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Sage.

- Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Creswell, J. W., & Tashakkori, A. (2007). Developing publishable mixed methods manuscripts. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(2), 107–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689806298644

- Darwin, J., & Melling, A. (2011, June 21–23). Mindfulness and situation awareness [Paper presentation]. The sixteenth International Command and Control Research and Technology Symposium (ICCRTS 2011), Québec, Canada.

- Didonna, F. (Ed.) (2009). Clinical handbook of mindfulness. Springer.

- Djikic, M. (2014). Integrating eastern and western approaches. The Wiley Blackwell handbook of mindfulness. John Wiley & Sons.

- Durosini, I., Triberti, S., Savioni, L., & Pravettoni, G. (2021). In the eye of a quiet storm: A critical incident study on the quarantine experience during the coronavirus pandemic. PLOS One, 16(2), e0247121. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247121

- Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6 Pt 2), 2134–2156. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12117

- Fiol, C. M., & O’Connor, E. J. (2003). Waking up! Mindfulness in the face of bandwagons. Academy of Management Review, 28(1), 54–70. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2003.8925227

- Flanagan, J. C. (1954). The critical incident technique. Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), 327–358. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0061470

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Fredrickson, B. (2000). Cultivating positive emotions to optimize health and well-being. Prevention & Treatment, 3(1), 1a. https://doi.org/10.1037/1522-3736.3.1.31a

- Frigotto, M. L., & Narduzzo, A. (2017). Mindfulness in action and time: An analysis of 911 response on September 11, 2001. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2017(1), 16915. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2017.16915abstract

- Gifford, J., & Young, J. (2021). Employee resilience: An evidence review. Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.

- Good, D. J., Lyddy, C. J., Glomb, T. M., Bono, J. E., Brown, K. W., Duffy, M. K., Baer, R. A., Brewer, J. A., & Lazar, S. W. (2016). Contemplating mindfulness at work: An integrative review. Journal of Management, 42(1), 114–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315617003

- Gorsuch, R. L. (1983). Factor analysis (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Grafton, E., Gillespie, B., & Henderson, S. (2010). Resilience: The power within. Oncology Nursing Forum, 37(6), 698–705. https://doi.org/10.1188/10.ONF.698-705

- Guan, J., Du, X., Zhang, J., Maymin, P., DeSoto, E., Langer, E., & He, Z. (2024). Private vehicle drivers’ acceptance of autonomous vehicles: The role of trait mindfulness. Transport Policy, 149, 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2024.02.013

- Haigh, E. A. P., Moore, M. T., Kashdan, T. B., & Fresco, D. M. (2011). Examination of the factor structure and concurrent validity of the Langer Mindfulness/Mindlessness Scale. Assessment, 18(1), 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191110386342

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications.

- Haller, C. S. (2015). Mindful creativity scale (MCS): Validation of a German version of the Langer Mindfulness Scale with patients with severe TBI and controls. Brain Injury, 29(4), 517–526. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2014.989906

- Harms, P. D., Brady, L., Wood, D., & Silard, A. (2018). Resilience and well-being. In: E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds), Handbook of well-being. DEF Publishers.

- Hartmann, S., Weiss, M., Newman, A., & Hoegl, M. (2019). Resilience in the workplace: A multilevel review and synthesis. Applied Psychology, 69(3), 913–959. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12191

- Hayes, A. M., & Feldman, G. (2004). Clarifying the construct of mindfulness in the context of emotion regulation and the process of change in therapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bph080

- Hodliffe, M. (2014). The development and validation of the Employee Resilience Scale (EmpRes): The conceptualisation of a new model [Doctoral dissertation]. Canterbury University.

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mulen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7CF7R

- Hougaard, R., Carter, J., & Mohan, M. (2020). Build your resilience in the face of a crisis. Coronavirus and business: The insights you need from Harvard Business Review, 2020, 70–73. https://hbr.org/2020/03/build-your-resiliency-in-the-face-of-a-crisis.

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hyland, P. K., Lee, R. A., & Mills, M. J. (2015). Mindfulness at work: A new approach to improving individual and organizational performance. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 8(4), 576–602. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2015.41

- Ivtzan, I., & Hart, R. (2016). Mindfulness scholarship and interventions: A review. Mindfulness and Performance, 2016, 3–28.

- Jiménez-Estévez, P., Yáñez-Araque, B., Ruiz-Palomino, P., & Gutiérrez-Broncano, S. (2023). Personal growth or servant leader: What do hotel employees need most to be affectively well amidst the turbulent COVID-19 times? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 190, 122410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.12241

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg016

- Kašpárková, L., Vaculík, M., Procházka, J., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2018). Why resilient workers perform better: The roles of job satisfaction and work engagement. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 33(1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/15555240.2018.1441719

- Keers, R. N., Plácido, M., Bennett, K., Clayton, K., Brown, P., & Ashcroft, D. M. (2018). What causes medication administration errors in a mental health hospital? A qualitative study with nursing staff. PLOS One, 13(10), e0206233. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206233

- Kemper, K. J., Mo, X., & Khayat, R. (2015). Are mindfulness and self-compassion associated with sleep and resilience in health professionals? Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 21(8), 496–503. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2014.0281

- Kuntz, J. R., Näswall, K., & Malinen, S. (2016). Resilient employees in resilient organizations: Flourishing beyond adversity. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 9(2), 456–462. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2016.39

- Kurotschka, P. K., Serafini, A., Demontis, M., Serafini, A., Mereu, A., Moro, M. F., Carta, M. G., & Ghirotto, L. (2021). General Practitioners’ experiences during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: A critical incident technique study. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 623904. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.623904

- Laeequddin, M., Waheed, K. A., & Sahay, V. (2023). Measuring mindfulness in business school students: A comparative analysis of Mindful Attention Awareness Scale and Langer’s Scale. Behavioral Sciences, 13(2), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020116

- Langer, E. J. (1989). Minding matters: The consequences of mindlessness-mindfulness. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 22, 137–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60307-X

- Langer, E. J. (2004). Langer mindfulness scale user guide and technical manual. IDS.

- Langer, E. J., & Moldoveanu, M. (2000). Mindfulness research and the future. Journal of Social Issues, 56(1), 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00155

- Lee, M., & Jang, K. S. (2021). Nursing students’ meditative and sociocognitive mindfulness, achievement emotions, and academic outcomes: Mediating effects of emotions. Nurse Educator, 46(3), E39–E44. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0000000000000902

- Lee, Y. H., Richards, K. A. R., & Washburn, N. (2021). Mindfulness, resilience, emotional exhaustion, and turnover intention in secondary physical education teaching. European Review of Applied Psychology, 71(6), 100625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2021.100625

- Leong, C. T., & Rasli, A. (2013). Investigation of the Langer’s Mindfulness Scale from an industry perspective and an examination of the relationship between the variables. American Journal of Economics, 3(5C), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.5923/c.economics.201301.13

- Lin, Y. T. (2020). The interrelationship among psychological capital, mindful learning, and English learning engagement of university students in Taiwan. SAGE Open, 10(1), 215824402090160. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020901603

- Liu, X., Wang, Q., & Zhou, Z. (2022). The association between mindfulness and resilience among university students: A meta-analysis. Sustainability, 14(16), 10405. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610405

- Luthans, F. (2002). The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(6), 695–706. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.165

- Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60(3), 541–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x

- Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Walumbwa, F. O., & Li, W. (2005). The psychological capital of Chinese workers: Exploring the relationship with performance. Management and Organization Review, 1(02), 249–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2005.00011.x

- Luthans, F., & Youssef, C. M. (2004). Human, social and now positive psychological capital management: Investing in people for competitive advantage. Organizational Dynamics, 33(2), 143–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2004.01.003

- Luthans, F., Vogelgesang, G. R., & Lester, P. B. (2006). Developing the psychological capital of resiliency. Human Resource Development Review, 5(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484305285335

- MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130

- MacCallum, R. C., Widaman, K. F., Zhang, S., & Hong, S. (1999). Sample size in factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 4(1), 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.4.1.84

- MacKillop, J., & Anderson, E. J. (2007). Further psychometric validation of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29(4), 289–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-007-9045-1

- Marsh, H. W., & Hocevar, D. (1985). Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: First-and higher order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychological Bulletin, 97(3), 562–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.97.3.562

- Medvedev, O. N., Titkova, E. A., Siegert, R. J., Hwang, Y. S., & Krägeloh, C. U. (2018). Evaluating short versions of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire using Rasch analysis. Mindfulness, 9(5), 1411–1422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0881-0

- Metwally, M., & Ruiz-Palomino, P. (2022). The organisational psychology of ethical military leadership during times of crisis: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Military Ethics, 21(3-4), 337–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/15027570.2023.2177419

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage.

- Mitas, O., & Bastiaansen, M. (2018). Novelty: A mechanism of tourists’ enjoyment. Annals of Tourism Research, 72, 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.07.002

- Mitchell, A. E. (2021). Resilience and mindfulness in nurse training on an undergraduate curriculum. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 57(3), 1474–1481. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12714

- Moafian, F., Pagnini, F., & Khoshsima, H. (2017). Validation of the Persian version of the Langer Mindfulness Scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 468. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00468

- Montero-Marin, J., Tops, M., Manzanera, R., Piva Demarzo, M. M., Álvarez de Mon, M., & García-Campayo, J. (2015). Mindfulness, resilience, and burnout subtypes in primary care physicians: The possible mediating role of positive and negative affect. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1895. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01895

- Morera, O. F., & Stokes, S. M. (2016). Coefficient α as a measure of test score reliability: Review of 3 popular misconceptions. American Journal of Public Health, 106(3), 458–461. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302993

- Morse, J. M. (2000). Determining sample size. Qualitative Health Research, 10(1), 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973200129118183

- Näswall, K., Kuntz, J., Hodliffe, M., & Malinen, S. (2013). Employee Resilience Scale (EmpRes): Technical report (Resilient Organizations Research Report 2013/06). University of Canterbury, Christchurch.

- Näswall, K., Kuntz, J., & Malinen, S. (2015). Employee Resilience Scale (EMPRES) measurement properties. Resilient Organizations. https://www.resorgs.org.nz/publications/employee-resilience-scale/.

- Näswall, K., Malinen, S., Kuntz, J., & Hodliffe, M. (2019). Employee resilience: Development and validation of a measure. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 34(5), 353–367. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-02-2018-0102

- Neff, L. A., & Broady, E. F. (2011). Stress resilience in early marriage: Can practice make perfect? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(5), 1050–1067. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023809

- Olson, K., Kemper, K. J., & Mahan, J. D. (2015). What factors promote resilience and protect against burnout in first-year pediatric and medicine-pediatric residents? Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 20(3), 192–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156587214568894

- Pagnini, F., Bercovitz, K. E., & Phillips, D. (2018). Langerian mindfulness, quality of life and psychological symptoms in a sample of Italian students. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-0856-4