Abstract

The past fifteen years have witnessed increasing effort to study and understand the belief system of Bronze Age Scandinavia. Different forms of material culture—including rock art and metalwork—and allusions to texts such as the Vedic Rig Veda, have led many to suggest the existence of a shared belief system with an Indo-European solar focus. Yet certain symbols attributed to this Indo-European system seem to have striking parallels in later Norse religious iconography—symbols such as weapon dancer imagery. Several examples of Bronze Age rock art display scenes of weapon-bearing figures, performing ritualistic motions that some have interpreted as dancing. Could this represent a case of prehistoric continuity? By presenting and comparing the Iron and Bronze Age evidence, this paper suggests a possible continuity in representations of warrior rituals on figurative material, underlining the importance of advertising a warrior identity and mentality in Prehistoric Scandinavian communities. In doing so, it also emphasizes the endurance of Prehistoric Scandinavian symbolic structures overall.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

For the past fifty years the archaeological community has worked to better understand Bronze Age Scandinavia; a period where our lack of information has often painted it as one of myth and legend. Much of the archaeological evidence, including the numerous rock carvings found throughout the region and their intricate symbols, often led scholars to characterize Scandinavian communities of this time as drastically different from those of the Norse Iron Age. Recent reviews of the evidence however, call these characterizations into question. Using prehistoric Scandinavian depictions of warrior figures as an example, this paper argues that Bronze Age and Norse communities of Scandinavia shared similar cultural values—in this case, the particular importance of the strength and power of the prehistoric warrior in local society.

1. Introduction

The past fifteen years have witnessed increasing efforts to study and understand Bronze Age Scandinavia (1700–500 BC). By examining different forms of material culture—including rock art and metalwork—and using allusions to texts such as the Vedic Rig Veda, the existence of a shared Bronze Age southern Scandinavian belief system with an Indo-European solar focus has come to be suggested by several scholars (e.g., Kaul, Citation2017; K. Kristiansen & Lisbeth, Citation2014; J. Ling & Uhnér, Citation2014). Yet when examining the iconography linked to this Indo-European system and that of the Norse Iron Age, respectively, it becomes clear that there may be possible overlap. For example, weapon dancer imagery—iconography commonly attributed to the Norse Scandinavian belief system—seems to have several correlations in Bronze Age rock art. Do they represent the same symbol?

Defining “weapon dancer” imagery as Norse depictions of anthropomorphic figures wielding weaponry, posed in a dance-like stance, the following paper examines the possible use of this motif in both periods of prehistoric Scandinavia. It first introduces weapon dancer iconography and its use during the Norse period (AD 400–800). It then proceeds by analysing examples of similar-looking motifs found on Bronze Age rock art (1700 BC-200 AD) using three case studies. While there are similar depictions of possible weapon dancer imagery on figurines, for the sake of time this paper will focus on rock art. By examining the potential similarities and differences of these depictions, this paper aims to emphasize the endurance of Prehistoric Scandinavian symbolic structures. Specifically, it seeks to underline the long-standing importance of the signalling of a warrior identity in Prehistoric Scandinavian communities. Before beginning, however, it is important to understand current views regarding possible continuity between Iron and Bronze Age Scandinavia.

2. Current arguments: Bronze and Iron age connections

Increasing academic attention is being directed towards the potential continuity which may exist between Bronze and Iron Age Scandinavian belief systems. Over the past twenty years several archaeologists have presented arguments suggesting key Norse religious elements—including symbolism and ritual practice—may have been shaped by enduring symbolic structures of the Bronze Age (e.g., Ahlqvist & Vandkilde, Citation2018; Andrén, Citation2014; Fredell, Citation2003, pp. 250–253; Glørstad & Melheim, Citation2016; K. Kristiansen & Lisbeth, Citation2014). For example, Anders Andrén performs a comparative analysis of Norse and Bronze Age iconography in his 2014 book Tracing Old Norse Cosmology. In this text, Andrén (Citation2014) uses pictorial depictions and a thorough theoretical understanding of the mythological cosmologies of both periods to show that several Bronze Age icons (including solar, dual figure, and ship symbolism) endured and were given new contexts in the Norse system. Yet that is not all; in several cases, Andrén shows that practices of the earlier Bronze Age system may have gone on to shape rituals and myths of that of the Iron Age.

Andrén’s analyses are symptomatic of a growing movement seeking to view the development of Prehistoric Scandinavian social structures in the longue dureé. Previously, archaeologists studying the different periods of Prehistoric Scandinavian society preferred to view their material in isolation. This was, and in some cases still is, prevalent in the Iron and Viking Age archaeological traditions. Scholars of this period have often preferred to study its social developments in relation to the processes occurring within Scandinavia at this point—namely the long-distance interaction which took place between local communities and foreign groups (e.g., L. Hedeager, Citation2007; Storgaard, Citation2001; Storgaard & Jørgensen, Citation2003). This may be the result of a reliance on the ethnographical studies and later historical accounts available for this period, where contact between Iron Age Scandinavia and groups such as the Roman Empire and later Christian Europe are more or less recorded. While the immense amount of trade and interaction which took place between these foreign organizations and Iron Age Scandinavian groups undoubtedly helped shape the Norse belief system (as also shown by Andrén), such a dependence on textual evidence has made practitioners of this tradition hesitant to make connections to earlier phases of society, where no such evidence exists.

Yet many convincing studies are now presenting the various possible patterns in long-term Scandinavian belief. Symbolic elements classically attributed to Iron Age Scandinavia are now being argued to represent enduring Scandinavian social structures, some having origins as early as the Early Bronze Age (see Davidson, Citation1971; Fredell, Citation2003; Kristiansen, Citation2014, Citation2016 ; Melheim, Citation2013). Kristian Kristiansen (Citation2016) argues that the study of enduring Scandinavian ritual practices grants the academic community a better understanding of the long-term processes affecting society during the prehistoric period. For example, K. Kristiansen (Citation2016) argues that what he sees as the continued use of Bronze Age ship symbolism in Norse iconography emphasizes the importance of mobility, trade, and technological innovation during this period. If weapon dancer imagery faces similar continuity, as this paper suggests, how would this characterize the social structures of prehistoric Scandinavia? This paper will go forward with this question in mind, determining how the possible similarities and differences of the depictions in both periods reflect long-term processes in Scandinavian society.

3. Norse weapon dancers

The Scandinavian Iron Age begins around 500 BC. It is at this point that a system of centralised confederacies began to emerge onto the cultural landscape, where manipulation of trade and military resources allowed powerful individuals to control/shape immense hinterlands (Hedenstierna-Jonson, Citation2009; Nielsen, Citation2005; T. D. Price, Citation2015; Thurston, 2001; Williams, Citation2008). It is also at this point that—based on examinations of rock art and material culture—worship of the Aesir/Vanir pantheon (such as Odin, Thor, and Freyr) begins to appear in Scandinavian society (Andrén et al., Citation2006; L. Hedeager, Citation2011; K. Kristiansen & Lisbeth, Citation2014; T. D. Price, Citation2015; Pearson, Citation2006).

The following section of this paper introduces the weapon dancer motif in this Norse context. It first introduces the stylistic elements which characterize this imagery and the interpretations surrounding them. It then examines it in the wider context of Norse society and belief, reflecting on how it characterizes the ritual practices of Scandinavian groups during this period and contemporary social developments/movements. As stated above, this period is frequently studied using later textual evidence and comparative analyses of Indo-European Germanic mythology/societies. While this has allowed for a good understanding of Norse belief, it will still be important for this author to view such information with a critical eye.

3.1. The imagery and the ritual

The Norse weapon dancer motif appears in Sweden and Denmark, as well as Anglo-Saxon England, from AD 400 to 800 (Axboe, Citation1986; T. D. Price, Citation2015; Speidel, Citation2004). Depictions of this motif typically portray individual or dual male figures characterized by the following stylistic traits:

Helmets or headpieces with attached horns, usually terminating in bird beaks

Belts around the waist

Lightly-clothed or naked bodies

Weaponry held in both hands, positioned at various angles (incl. spears, swords, axes)

Poses giving the impression of active motion

The above five elements, with minor variations, are schematically found on all examples of the Norse weapon dancer motif. Study of this imagery has revolved around each of these traits, yet the last three—naked or nearly naked bodies, poses indicating motion, and weaponry—have received the brunt of scholarly attention. The nakedness of the depicted figures and the poses each are presented taking—as if in the midst of leaping or running, perhaps dancing (Figure )—have resulted in frequent ritualistic interpretations (Bastian and Masquelier, 2005; Bonfante, Citation1989; Davidson, Citation1971; Hawkes et al., Citation1965; Nordberg & Wallenstein, Citation2016; Price, Citation2008). Additionally, several suggest that the dancing figures are portrayed holding their weapons in a ceremonial manner, either pointed up or down as if in presentation (Bayless, Citation2016; Davidson, Citation1971; Nordberg & Wallenstein, Citation2016; Price, Citation2008). As a result, the scholarly community has often interpreted this form of iconography as portraying a ritualistic martial dance, coining the terms “weapon dancer” or “warrior dancer” imagery

Due to its frequent ritual-martial interpretation, Norse weapon dancer imagery is often associated with the rituals of the Germanic Indo-European warrior societies which are suggested to have existed during this period—including that of the Berserkirs (bearshirts or bareshirts) and Ulfhednar (wolfshirts) (Figure ) (Jackson, Citation2016; Raffield et al., Citation2016; Rees, Citation2018; Schjødt, Citation2011; Speidel, Citation2002, Citation2004). The weapon dance is suggested to have served as a ritual of initiation and battle preparation for these societies, through which warriors invoked the power of Odin—Norse inventor/leader of the weapon dance—in order to achieve an ecstatic battle madness (Figure ). Wearing the skins and masks of predatory animals, warriors are suggested to have nakedly danced themselves into a frenzy, believing Odin would allow them to transform into the animals they represented; granting invulnerability as well as animalistic strength and speed (Jackson, Citation2016; Liberman, Citation2005; Nordberg & Wallenstein, Citation2016; Raffield et al., Citation2016; Schjødt, Citation2011; Wade, Citation2016). This is argued to reflect the animistic belief in shapeshifting which Norse and Indo-European ritual is suggested to have focused on (L. Hedeager, Citation2007, Citation2011; Hedenstierna-Jonson, Citation2009; Jennbert, Citation2011; Price, Citation2002). These societies believed that animals and mankind shared the same soul essence and that by associating one’s self with nature, one became endowed with wild/raw power through animistic transformation (Helmbrecht, Citation2011; Liberman, Citation2011; Pluskowksi, Citation2006; Rood, Citation2017; Wade, Citation2016). As a result, Norse warriors associated themselves with predatory animals (bears, wolves, eagles, etc.) through rituals such as the weapon dance in the hope that ritual transformation would allow them to obtain the predatory/violent characteristics with which they were attributed.

Figure 1. A foil design from one of the Vendel ceremonial helmets (500–700 AD). This foil depicts two figures wearing horned-helmets (terminating in bird beaks) and light robes. They are wielding swords upright in one hand and crossing spears in the other. Their feet are presented as if in motion, with one foot off the ground and the other set firmly forward, as if they had just leapt forth. As a result, they are interpreted as dancing, a classic example of the weapon dancer motif. (Viking Rune Citation2018)

Figure 2. Plate D of the Torslunda Die Matrix (500–700 AD). This foil depicts a horned, naked male figure—suggested to be Odin—dancing while wearing a sheathed sword and wielding two spears, one angled upward and another angled downward. Much like Figure , the figure’s feet is presented as if he had just leapt forward, interpreted as dance. This example, however, portrays the dancer with a spear-bearing warrior wearing a wolf-skin. This may suggest that this picture portrays the Norse god Odin leading a mortal warrior of the wolf-warrior group in the weapon dance. As a result it portrays the function of animistic transformation attributed to Odin and the weapon dancer ritual, in which the participated wolf-warrior would be granted the ability to transform into a wolf, lending him its predatory strength and speed. (Stjerna 1903)

Figure 3. Drawings from the different sections of one of the Danish Gallehus Horns (AD 400–500). Looking at the top-most section, one can see two naked horned-figures wielding various weapons in their hands (one holding what seems to be a spear and an axe, while the other holds a spear and a sword). To the left of these figures are what seem to be bare-chested figures holding swords and shields. As the Gallehus horns have been interpreted to provides scenes from Norse myth, it could be possible that this represents an early portrayal of the weapon dance. Where naked Odin-like figures are leading human warriors in the ritual, much like Figure . (Rasmussen 2011)

This animistic ritual function of the Norse weapon dance is reflected by its symbolic depictions. For example, Michael Speidel (Citation2002) argues that the Danish Års bracteate (Figure ) depicts the Norse god Odin in the midst of transformation, achieved through the use of the weapon dance. Presented in violent motion interpreted as dancing, he suggests the figure shows Odin twirling an axe in one hand and what may be a sword in the other, with a wolf-tail emerging from his lower body. As a result, he suggests that the bracteate depicts Odin’s patronisation of the wolf warrior cult and his ability to bestow wolf-like characteristics upon those who perform the ritual (Speidel, Citation2002, Citation2004). This proposed animistic focus of weapon dancer imagery is strengthened further when examining the horned helmets with which every example is characterized. Scholars of Indo-European religion argue that these horned-headpieces represent a long-standing Indo-European tradition where the transformative capabilities of divine and heroic figures were portrayed through the use of horned-helmets (Ahlqvist & Vandkilde, Citation2018; K. Kristiansen & Lisbeth, Citation2014; J. Ling et al., Citation2015; Nordbladh, Citation2012; H. Vandkilde, Citation2013). For example, the Greek Dioscuri were consistently depicted with either horns or horned-helmets in Bronze Age imagery due to several myths depicting their transformation into bulls (K. Kristiansen & Lisbeth, Citation2014; Speidel, Citation2004). While Indo-European allusions should always be taken with a grain of salt, such an interpretation is strengthened by the bird-beaked terminal ends which many of the horns of the dancers are shown with (Figure )—suggested to represent the heads of eagles, alluding to Odin’s frequent transformation into the animal in many of the Norse myths (Ahlqvist & Vandkilde, Citation2018; Gräslund, Citation2006; Langer, Citation2002; Nordbladh, Citation2012).

Figure 4. The Danish Års bracteate (400–500 AD). Representing a profile view of a helmeted Odin participating in the weapon dance ritual, the reader can observe a line of ornamented dots extending from his lower body on the left. This ornamentation can be interpreted as a tail, possibly that of a wolf. As such, this bracteate once again portrays the animistic functions attributed to the Norse weapon dance. (Weng 2001)

3.2. Find background and social context

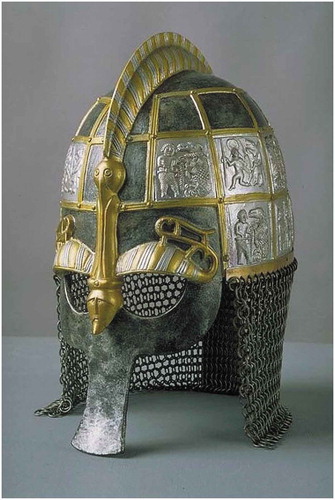

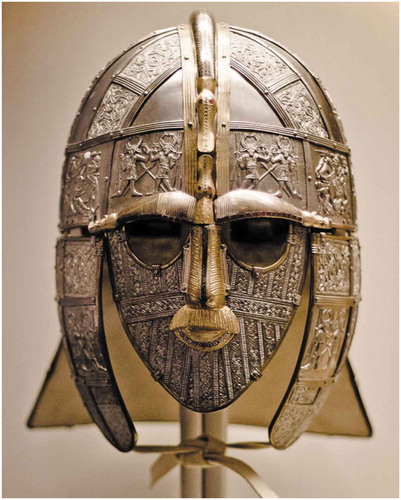

Found on material culture including jewellery, feasting equipment, and ceremonial helmets; many examples of weapon dancer imagery have been found in contexts related to the Iron Age elite. For example, the ceremonial helmets found in graves 1, 12, and 14 of the Swedish Vendel boat graves and that of Anglo-Saxon Sutton Hoo (600 to 700 AD) (Figures and ) were decorated using the Torslunda die matrix—Plate D depicting what is suggested to be Odin performing the weapon dance (Hawkes et al., Citation1965; T. D. Price, Citation2015; Price & Mortimer, Citation2014). When worn in a fire-lit hall, it is suggested that foils decorated by these plates would be emphasized by the light, hiding all other features of the wearer (Price & Mortimer, Citation2014; Rood, Citation2017). The hall acted as cultural centre to Iron Age Scandinavian society—where the elite regularly organized various assemblies, many revolving around establishing/maintaining the loyalty of war-bands (Hamerow, Citation2002; Larsson, Citation2011; T. D. Price, Citation2015; Raffield et al., Citation2016). As a result, it may be possible that the use of Norse weapon dancer imagery was closely tied to this function of the elite. Plate D was an intensely copied design of the Torslunda die matrix, with many of the dies for this plate having been found battered and partially-blurred from overuse (Axboe, Citation1986). This, and the uniformity with which weapon dancer imagery seems to be portrayed, makes it clear that Iron Age elite made an active choice to display/emphasize the weapon dancer motif in this ceremonial setting. As a result, it may be possible that this motif had a more strategic purpose aside from possibly depicting the rituals of elite warrior societies—specifically, elite hegemony.

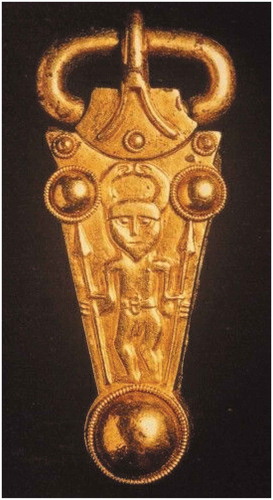

Figure 5. The Swedish Kungsängen figurine (800–1050 AD). This figurine portrays the Norse god Odin wearing a helmet with attached horns, terminating in bird beaks. These features have been interpreted as eagle beaks, alluding to the importance of the animal as a form often selected by Odin for shapeshifting. (Denstoredansk Citation2018)

Figure 6. A recreation of one of the Vendel ceremonial helmets (500–700 AD). Notice how a foil from Plate D of the Torslunda die, depicting Odin a wolf-warrior participating in the weapon dance, is featured prominently for all to see (top right design). When worn in a fire-lit hall, this design would be emphasized by the light, connecting the owner to this ritualistic tradition. (Deligiannis 2012)

The weapon dancer motif may have been used to signal a warrior mentality in ceremonial settings—specifically by the elite. As stated above, stylistic traits such as bull horns are depicted on every example of weapon dancer imagery. While suggested to portray the transformative abilities of the Norse god Odin, these elements were also associated with the Norse values of power, virility, discipline, aggressiveness, force, and strength (Davidson, Citation1971; Langer, Citation2002; Nordbladh, Citation2012). These were the ideal characteristics of a warrior in Norse society. Lotte L. Hedeager (Citation2011) argues that Norse symbols were used to reflect/reinforce the social and physical order of the universe. By portraying the god of warfare in association with the traits and rituals of a warrior ideology on visible ceremonial material culture, the social importance of such an ideology may have been increasingly brought into focus. This is reinforced by how widespread the use of weapon dancer imagery appears on elite material culture (Figure ). By displaying weapon dancer imagery on their personal belongings—associated with ceremonial assemblies and social functions—the elite may have manipulated social attitudes and identities, presenting the role of a warrior as one socially accepted and associated with power. Not only this, but by displaying this symbol on items which they regularly manipulated/handled, the elite may have signalled their leadership over the ideology/mentality they were emphasizing—symbolically affirming their control over Iron Age warriorhood and the society it characterized.

Figure 7. A recreation of the Sutton Hoo ceremonial helmet (500–700 AD). Notice how, like the above Vendel helmet, the dual weapon dancing Odin foil is featured prominently on the front of the helmet, meant to be seen by the viewer. This once again reinforces the idea that Iron Age elite wanted to emphasize this relief, and possibly the social values connected with it, in a ceremonial setting (Ramsay 2017)

4. The Bronze Age: A possible connection?

The Nordic Bronze Age occurs from 1700 to 500 BC (T. D. Price, Citation2015). Unlike the Iron Age, however, no textual evidence remains for study of this period. As a result, many turn to comparative analyses, examining Bronze Age Scandinavia in relation to either contemporary outside groups or later periods of local society (e.g., Glørstad & Melheim, Citation2016; Kaliff, Citation2005; K. Kristiansen & Lisbeth, Citation2014; Melheim, Citation2013). Many comparisons have focused on contemporary Indo-European groups in south-eastern Europe, where Scandinavian evidence such as the Trundholm chariot has close comparisons (K. Kristiansen & Fredell, Citation2010a; Thrane, Citation2013; H. Vandkilde, Citation2014; Wang, Citation2017). As a result, many have characterized the belief system of Bronze Age Scandinavia as Indo-European (Goldhahn, Citation2013; Kaul, Citation1998, Citation2017; Kristiansen & Larsson, Citation2010; J. Ling & Uhnér, Citation2014; H. Vandkilde, Citation2014). Scholars such as K. Kristiansen and Lisbeth (Citation2014) argue that through interaction with south-eastern Europe, Bronze Age Scandinavian belief came to revolve around the universal power of the sun and its cycle of night/day. While it is debated whether there was an accompanying pantheon of deities which participated in this cycle—including the Indo-European sky god, sun goddess, and divine twins—Bronze Age iconography is often argued to focus on this proposed Indo-European system (Ahlqvist & Vandkilde, Citation2018; Goldhahn, Citation2013; Kaliff, Citation2005; K. Kristiansen & Fredell, Citation2010a; J. Ling et al., Citation2015).

Figure 8. The Anglo-Saxon Finglesham belt (500–700 AD). Borrowing heavily from Scandinavian designs, this belt-buckle depicts a naked Wodan/Odin wearing a horned-helmet, wielding spears in either hand. Another example of the weapon dance on material culture, this piece is suggested to have belonged to a retainer of an Anglo-Saxon lord. This represents another instance where the elite were both connecting themselves and their retinue to images of warrior rituals. Much like the Vendel helmets, this may represent an elite-driven effort to signal both the social importance of a warrior identity and elite leadership of this identity (Viking Archeurope Citation2018)

The following section of this paper will now examine cases of Bronze Age rock art portraying scenes similar to that of Norse weapon dancer imagery. The author will observe three examples from southwestern and western Sweden, the heart of the rock art tradition in southern Scandinavia; including the “Dancing God” of Järrestad and panels of horned-figures at Bro Utmark and Kville. While there are many others, these three examples represent the most impressive and clearly researched. The author will compare the stylistic characteristics of the three examples to that of Norse Iron Age weapon dancer imagery, taking note of the similarities and differences. He will then put forward his own suggestive interpretation based on the apparent connections. As stated, there are no contemporary texts on which to fall back for interpretation. This ultimately forces the author to view the Bronze Age material through an Iron Age Norse lens, something he must proceed carefully with in order to avoid instances of circular reasoning.

4.1. Case study 1: The Järrestad “Dancing God”

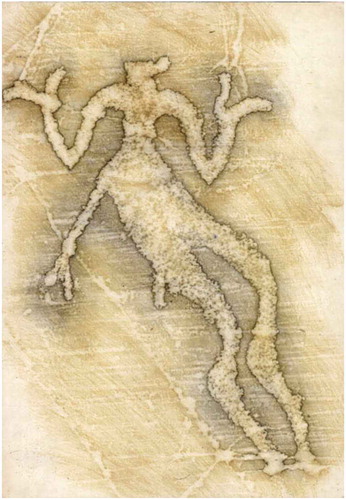

Lying on a cleared slope in south-eastern Skåne, the Järrestad panels were found to have one of the largest concentrations of Bronze Age rock petroglyphs in Sweden. Out of all of the images recorded, however, one has taken clear precedence in research. “The Dancing God”, as it has come to be called, presents the first example of possible Bronze Age weapon dancer imagery. Representing the largest of the Järrestad images, “The Dancing God” consists of a large (.8 meters tall) anthropomorphic figure pecked with distinct edges and carefully hammered out limbs (Figure ) (Coles, Citation1999). Its narrow upper body is separated from a heavier lower body by an un-pecked band denoting it as male (a trait found on other images of male figures at locations in Bohuslän) and has slender long legs bent at the knees in a position previously interpreted as a “ballet” stance (Coles, Citation1999). The figure’s arms are bent, with possible bands found on the upper arms, and its hands are upraised with only its thumbs distinguished. Concerning the figure’s head, it has been argued to resemble that of a bird (Coles, Citation1999). Additionally, there seem to be both the scabbard of a sword and that of a knife hanging from the waist of the individual, though the blades themselves are not shown in the motif. Surrounding the figure from the northwest and southwest are also a number of footprint images, including both single and paired feet with detailed toes (Figure ).

Figure 9. A rubbing of the Järrestad “Dancing God”. Starting with the head, one can see possible bird-like characteristics of the figure—representing the head of a swan or goose. Proceeding downward, the un-pecked band splitting the figure’s two upper halves seems to be attached to the scabbard and the potential knife sheath shown in the image, possibly representing a belt. Pairing the large size this figure with its stance, shown with its knees bent and its legs together (as if about to leap), it is hard to deny the ritualistic interpretations attributed to this image. (Swedish Rock Art Research Archives Citation2008)

Figure 10. The “Dancing God” of Järrestad and the various motifs surrounding it. As one can see, a large amount of footprint images and cupmarks surround the more central figure on all sides. If the current interpretations of these signs are accurate, specifically their various associations to divine and ritual contexts, it further reinforces the potential socio-ritual significance of the central dancing figure. (Coles, Citation1999)

Dated to the Late Bronze Age (1100–200 BC), the “Dancing God” possesses both differences and similarities to Norse weapon dancers. Unlike Norse weapon dancer imagery, it is debated whether the figure is naked, as it is possible that the figure is depicted wearing both different bands and a garment on its upper body (Bertilsson & Anati, Citation2014; Coles, Citation1999; Skoglund, Citation2013). Also, the head of the “Dancing God” does not have horned characteristics, instead possibly possessing those of other animals such as a bird. Yet scholars such as Peter Skoglund (Citation2013) have compared this figure to later Norse depictions of weapon dancers. This is primarily due to its previously-mentioned bent-kneed stance, suggesting the motion of dancing, and the pieces of military equipment with which it is portrayed. Many use the figure’s large size and its central placement within the panel to suggest that the carving represents a human or deity in the midst of performing a ritual (Bertilsson, Citation2013; Bertilsson & Anati, Citation2014; Coles, Citation1999; Skoglund, Citation2013, Citation2016, pp. 109–110). When also considering the animistic transformation the figure seems to be experiencing—the bird-like traits of its head suggesting shapeshifting—the figure is certainly reminiscent of later depictions of a dancing Odin undergoing similar transformations while performing the weapon dance. This ritualistic interpretation is reinforced by the numerous images of footprints clustered around the motif, which are consistently interpreted in similar contexts—representing either the soles of an invisible deity, the feet of the dead, or the signatures of spiritual leaders who had previously partaken in rituals associated with that image (Bertilsson, Citation2013; Bradley, Citation1999; Melheim, Citation2013; Skoglund, Citation2013; Skoglund et al., Citation2017).

4.2. Case study 2: Bro Utmark’s warrior figures

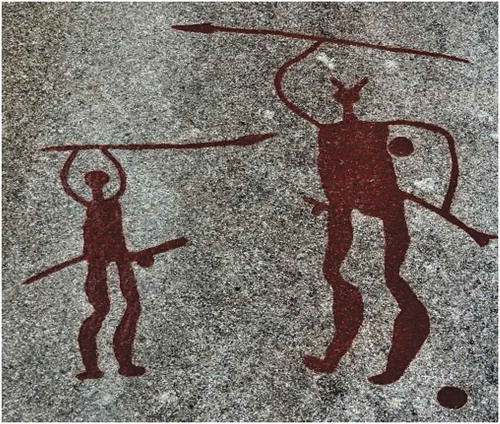

The second case study of this paper focuses on a rock art location in Swedish northern Bohuslän. Located on an open ridge, Bro Utmark is one of the largest and most striking rock art sites of the region. The unusual quality of the petroglyphs on-site and the incredible state of preservation of the material has few comparisons elsewhere. Amongst the several images found here, specifically on the centrally-placed Panel A (according to John Coles’ grid of 2004), seven depictions of weapon-bearing figures are displayed (Figures and 1). Each of the individuals are pecked deeply into the granite of the location, presenting large (0.5 meters each) figures wielding a mixture of weaponry; including four spears, possibly two axes, and bolas (Coles, Citation2004). Depicted taking an almost sedentary stance, with exaggerated legs and calves brought close together, each of the individuals are holding their weapons in an upright position and performing what is interpreted as a waving motion (Coles, Citation2004). Additionally, each of the figures are also displayed with scabbards for swords attached to their hips, similar to that of the Järrestad figure. Five of the seven figures are also portrayed possessing definitive horned traits, depicted with either horned-helmets or heads replaced entirely with horns. These figures are accompanied by a number of other figurative elements: including thinly-drawn boats, a human performative figure (typically characterized as acrobat imagery) (Coles, Citation2004; Iversen, Citation2014) placed above them, animal-like figures at their feet, a smaller spear-bearing horned-figure in a boat to the West, and a number of more abstract images including cupmarks.

Figure 11. A drawing of the various horned and non-horned weapon-bearing figures observed at Bro Utmark. As one can see, the horned figures are placed centrally in the motif with a particular emphasis on their weapons and how they are wielding them. As stated in the paper, John Coles suggests that their bearing seems to give off an impression of waving. (Coles, Citation2004)

Figure 12. John Coles’ drawing of the layout of the Bro Utmark petroglyphs. As shown by the drawing, the weapon-bearing figures were placed centrally in not only their own panel, but also more or less centrally in the midst of all the images found at Bro Utmark—perhaps indicating their importance to the groups who maintained them. (Coles, Citation2004)

The horned characteristics of the Bro Utmark images and the designs of the pecked-in boats surrounding them date these figures to the Late Bronze Age (1100–200 BC). The similarity of their physical characteristics and their close proximity to one another make it possible that they were all pecked within a short time during this period. Additionally, the physical forms of each of these figures were continuously re-pecked by the artists over time, maintaining the motif and suggesting that they were all supposed to be seen together (Coles, Citation2004). As a result, John Coles (Citation2004) suggests that the warrior figures of Bro Utmark may have been used to mark the prestige of fighters in Bronze Age society and the wider/deeper ideologies attributed to such a class. In the case of this study, these figures represent another possible example of Bronze Age rock art sharing similar characteristics with that of later Iron Age Norse imagery. While the figures themselves are depicted stationary, not appearing to be leaping or dancing, the suggested “waving” of the figure’s weapons and the acrobat placed directly above them gives off an impression of ritualistic motion or even shapeshifting (Figure ). The depiction of at least two possible phalluses also suggests that it is likely that some of the figures presented in the motif are naked. Yet this ritualistic interpretation is perhaps most reinforced when considering the horned-figures taking part in the scene. Many of these figures are accompanied by cupmarks and possess exaggerated calves—figurative elements often interpreted to convey power and transformative capabilities—suggesting they are undergoing transformation (Fredell, Citation2003, pp. 270–275; J. Ling et al., Citation2015; T. D. Price, Citation2015). Additionally, each of the horned figures are placed centrally in the motif amongst the non-horned figures, as if they were leading them in the ritual taking place. This brings to mind later Norse imagery depicting Odin leading wolf-warriors in the weapon dance a striking comparison when examining a similar motif found at another site nearby (Figure ).

Figure 13. A close-up image of the horned figures of the Bro Utmark panel. Comparing the central figure on the left to the Järrestad figure, one can observe a similar leg position which gives off the impression of built-up tension—as if the figure were about to leap. This suggests that not all of the figures depicted were stationary. Overall, paired with the acrobat placed above them and the particular emphasis which all show in waving their weapons, a general impression of motion is given off. (Swedish Rock Art Research Archives 2015)

Figure 14. A rock carving from Tanum in Bohüslan depicting a similar motif to that found at Bro Utmark. In this carving, a large horned-figure and a smaller non-horned figure are wielding spears in a position similar to that of Bro Utmark, possibly waving them. Both of the figures are also depicted naked and with sword scabbards attached to their waists. Several characteristics—including the cup marks surrounding the figure on the right, its exaggerated characteristics and larger size, and its horns—have led many to characterize this motif as a possible depiction of a heroic or divine figure from Bronze Age myth leading a mortal in the weapon dance (Horn et al. Citation2018).

4.3. Case study 3: The battle of Kville

The final case study of this paper remains in Bohuslän, at the Hede site of the parish of Kville. Pecked into the granite slabs of what was once an open landscape, one panel possesses a large number of both horned and non-horned figures (numbering to at least ten figures) standing amidst several different forms of imagery (Figure ). Many, if not all, of the figures presented are shown to be naked; with several phalluses suggesting the predominating male gender of those portrayed. Seven of the figures presented, primarily those with horned traits, are also shown wearing sword scabbards and wielding different forms of weaponry (including spears, swords, and axes). All of the pecked figures are presented surrounding a larger central weapon-bearing horned figure. Paired with the scattering of suggested shields, swords, and abstract sun motifs; an interesting scene reminiscent of battle is presented. Of particular interest to this study, however, is in the uppermost limits of this panel, where two horned figures are presented with exaggerated calves portrayed in a bent-kneed stance similar to that of the Järrestad “Dancing God” (Figure ). These figures are raising their weapons into what seems to be a waving motion, giving off an overall impression of active motion. Facing these figures is a non-horned figure with their arms upraised, a gesture often interpreted as representative of adoration or participation in ecstatic ritual (Bertilsson, Citation2013; Price, Citation2008).

Figure 15. The panel found at Hede, Kville, on which this case study focuses. As shown, a large number of both horned and non-horned figures are depicted amongst several different forms of abstract imagery. The large amount of figures shown with weaponry, and what seems to be many shields and swords deposited throughout the scene, gives off an impression of battle (expanded on below) (Swedish Rock Art Research Archives 2019)

Figure 16. The possible motif of ritual dancing taken from the uppermost limit of the Hede panel. As stated, this scene depicts two horned figures possibly dancing with their weapons as a non-horned figure observes the ritual taking place. Looking at the two right-most figures, it seems that tail-like lines are descending from their lower bodies. These figurative details could represent an instance of animistic transformation, with both the horned dancer and non-horned adorant shapeshifting as a result of the possible ritual which is taking place. This possibility is reinforced by the cup mark placed above the two dancers. (Swedish Rock Art Research Archives 2019)

Once again dated to the Late Bronze Age (1100–500 BC), the Hede panel provides another possible Bronze Age parallel to Norse weapon dance imagery, particularly in its uppermost images. As stated above, two horned figures are presented taking stances one could describe as dancing, their long legs bent at the knees and their weapons waving. Next to these figures is a non-horned individual who seems to be facing them with their arms upright, possibly participating in the ritual taking place adjacent to them. Considering the cupmark placed above them and both the exaggerated calves and tail-like lines with which they are depicted, it appears that at least two of the figures (two to the right) may be undergoing a transformation. Both D. Vogt (Citation2014) and H. Vandkilde (Citation2013) suggest that the overall panel represents a battle, possibly fought by several heroic figures. This is a convincing interpretation when one looks to the central motif, where a large figure is shown dominating the field with what appears to be discarded swords and shields littering the space around it. Yet this is also an interesting interpretation when considering the possible ritual taking place above. If this were in fact a scene of battle, perhaps commemorating a past victory of the artists, one could view the ritual depicted above as either adoration of the beings who granted them victory or as signalling of the ideology and rituals which allowed them to persevere. This interpretation of ritualistic commemoration is further reinforced by additional depictions of similar motifs recorded elsewhere on the site (Figure )

Figure 17. A motif found close to the battle scene at the Hede panel. Much like the scene placed above the battle motif, this scene could represent yet another instance of a possible weapon dancing ritual. While sedentary leg-wise, the figure on the left is waving its weapon and the figure on the right has its arms raised in possible adoration of the weapon-waving figure. These figures seem to be placed amongst various cupmarks and possibly discarded shields, suggesting a possible connection with power and battle. The repetition of this motif of ritualistic motion is interesting, especially when taking in its possible martial surroundings. (Swedish Rock Art Research Archives 2019)

4.4. Similarities and differences, what do they mean?

Each of the case studies examined by this paper presented Bronze Age rock art with stylistic elements similar to that of Iron Age Norse weapon dancer imagery. In each case, the figures studied were presented wielding a mixture of weaponry; primarily spears and axes with sword scabbards attached to their waists. Each of these figures were also depicted in stances giving off an overall impression of motion, either through a bent-kneed stance or the waving of weapons. As a result, it may be possible that these scenes represent a ritualistic narrative, perhaps one focused on animistic transformations similar to that of the later Norse material—suggested by the predominant use of horned, naked, and animalistic characteristics. While it is still possible that all of the figures examined by this paper represent staged fighters, the above elements makes it easy for one to establish a link between the Bronze Age figures and that of Norse weapon dancer symbols. Yet there were also cases of variation observed. For example, the Järrestad “Dancing God” was both clothed and depicted with bird-like characteristics rather than horned. How should the similarities be interpreted? How should the differences be taken? Should this author view them as just regional variations of the same phenomenon, depicting an overall tradition with links to later Norse practices?

It is possible, but in what way? As stated above, many archaeologists study Bronze Age Scandinavia using the same Indo-European lens employed for later Norse society. Such studies frequently link possible Bronze Age weapon dancer imagery to that of the later Iron Age by placing the ritual’s origin during this period (e.g., K. Kristiansen & Fredell, Citation2010a; Speidel, Citation2004). These arguments are based on comparisons to similar rituals found in contemporary Indo-European groups in south-eastern Europe, where regular use of weapon/war dances is recorded (Figure ) (Campbell, Citation2012; Douka et al., Citation2008; J. Ling & Uhnér, Citation2014; Lykesas & Mouratidisof, Citation2005). They suggest that rituals such as the weapon dance were imported from this area through connecting trade routes, where elite Scandinavian groups adopted/adapted a ritual with which they identified (Ahlqvist & Vandkilde, Citation2018; Bengtsson, Citation2017; J. Ling & Uhnér, Citation2014; Speidel, Citation2004; H. Vandkilde, Citation2014; Winter, Citation2005). Kristian Kristiansen (Citation2011) goes even further, suggesting that the horned figures depicted in Bronze Age Scandinavian weapon dancer imagery actually represent the Divine Twins—Indo-European inventors and patrons of the weapon dance—instructing and leading Scandinavian warriors in the weapon dance ritual. As a result, such arguments suggest that Bronze Age weapon dancer imagery represents a direct link to Norse iconography, representing an earlier adopted ritual which faced extended use in society despite the transition to a different belief system. Yet should this be the main take away from this imagery? Could there be a more pragmatic interpretation?

5. Discussion: Weapon dancers, warrior institutions, and a warrior identity

Interpretations such as those above—while helpful in allowing archaeologists to conceptualize Bronze Age cosmology and the possible effects of cultural transmission—are done through an Iron Age/Indo-European lens, one which can never be proven. It might be more productive to instead turn to the material context of this iconography, determining how its use reflects social developments in Bronze Age Scandinavia. For instance, it seems that weapon dancer imagery emerged as war-bands became increasingly prevalent in Bronze Age Scandinavian society. Warrior graves and archaeological evidence of warfare (skeletal trauma, mass graves, weapon repair and deterioration, etc.) suggest that a system of warrior aristocracies emerged in Scandinavia by the Late Bronze Age (Earle, Citation1997, pp. 18–23; Harding, Citation2015, Citation2018; Thrane, Citation2013; H. Vandkilde, Citation2012, Citation2014). This system, and the power of the individuals who ruled through it, is argued to have focused on the ability to organize groups of warriors for use in violent competition (K. Kristiansen, Citation2010b; J. Ling & Toreld, Citation2018; Skogstrand, Citation2016; Thrane, Citation2009; Vandkilde 2018). As a result, it was often the case that the long-term success of socio-political organizations during this period depended on legitimization through ideology (Harding, Citation2015; K. Kristiansen & Lisbeth, Citation2014; J. Ling, Citation2014; D. Vogt, Citation2014). Therefore, it is possible that the emerging Bronze Age elite used symbolic structures such as weapon dancer imagery to signal and reinforce the social importance of the warrior institutions on which they depended for control.

Power in prehistoric Scandinavian society was entrenched and directly linked with ritual. As a result, it is often suggested that Scandinavian rock art was used as a medium where figurative material communicated socio-economic discourse through the depiction of myth and ritual (Anati, Citation2017; Fredell, Citation2003, pp. 270–273; J. Ling, Citation2014; D. Vogt, Citation2014). For example, J. Ling (Citation2014, pp. 170–180) argues that many of the rock art scenes attributed to prehistoric Scandinavia used figurative depictions to illustrate rhetoric and articulate social matters. Operating outside of spoken language, he suggests that rock art worked as “socio-symbolic media”, using dramatic and suggestive themes to direct attention to certain social positions and practices that were relevant at the time of their creation. The majority of Late Bronze Age rock art depicting warrior scenes and rituals in the landscape was created in a short amount of time—with most possibly coming into existence in a shorter time span than one hundred eighty to two hundred years (, Citation2011, Citation2014). As stated above, warrior groups became important parts of Scandinavian society at this time, especially as a means of attaining/maintaining political power. This movement in rock art could be approached as an expression of the growing role warrior institutions played in Bronze Age socio-political development. Specifically, it may represent the use of social mediums to encourage cultural acceptance of the growing presence of warrior aristocracies in Scandinavia at this time—weapon dancer symbolism representing one material expression of this movement.

Each of the examples of possible Bronze Age weapon dancer imagery examined above were placed on panels in open landscapes, either on or close to important passages through the region (Coles, Citation1999; Sjöberg, Citation1994; Skoglund, Citation2013). They were also placed centrally in each of the panels into which they were pecked. As a result, it was often the case that the weapon dancer motifs were the first observed upon approach. It is possible that the elite may have used weapon dancer imagery on rock art to signal warrior institutions and their associated identities, ideologically legitimizing and normalizing their growing roles in society. The repeated use of these motifs in such visible and ceremonial settings may have both publicly stressed the growing importance of a warrior identity in Scandinavian society and emphasized what a warrior should be—using such characteristics as horns, exaggerated calves, and depictions of ritual dance to express strength, endurance, and power. In doing so, such features may have not only encouraged further participation in contemporary warrior institutions, but also created a symbolic system which provided group cohesion for those already a part of such organizations. As a result, Bronze Age warriorhood would have been increasingly placed in the social spotlight—making this ideology dominant—with the controlling role of the elite being signalled as well.

Such an interpretation provides a possible link to the use of weapon dancer imagery during the Norse Iron Age. As stated above, a system of confederacies appeared throughout southern Scandinavia during this period. These organizations were involved in constant warfare and, similar to the Bronze Age elite, the groups controlling Iron Age Scandinavia did so through the ability to organize bands of warriors (T. D. Price, Citation2015; Hedenstierna-Jonson, Citation2009; Thurston, 2001; Williams, Citation2008). Weapon dancer iconography seems to have been used similarly in both periods, placed on visible features or material culture used in ceremonial settings. Not only this, but the stylistic characteristics with which this form of imagery was depicted seems to have been consistent—despite the seemingly significant gap between the two periods of use—using elements such as horns, exaggerated limbs, and at times nakedness to convey the warrior values of strength, power, and recklessness. As expressed throughout this paper, it is possible that this continuity in the use of weapon dancer iconography represents the long-standing importance of warrior identities and mentalities to Scandinavian society during the Prehistoric period. As a consistently important factor in establishing power and territory in society, significant importance may have been placed on the signalling of Scandinavian warriorhood; not only to ensure the existence of a ready supply of warriors, but also to reinforce the growing control of the elite.

6. Results: Prehistoric iconography in the Longue Durée

This paper aimed to determine the possible similarities between Iron Age Norse and Bronze Age Indo-European Scandinavian use of the weapon dancer motif. Examination of this motif in both periods has revealed a possible long-term persistence in both use and meaning. Possibly appearing during a period of change and socio-political instability, weapon dancer symbolism may have been used to reflect/emphasize the importance of a warrior ideology in an increasingly militaristic society. As masculine warrior identities became fully established/predominant during the Iron Age, the weapon dancer symbol continued to be used to emphasize/reflect the importance of this mentality to Scandinavian society—despite the transition to the Norse belief system. Yet it is important to remember the limitations of modern study of prehistoric belief systems and any interpretations produced as a result.

The interpretation presented is based on analysis of material culture and later documentation. Just as interpretations of an Indo-European Bronze Age are based on examinations of solar imagery on uncovered material and comparative analyses with contemporary Indo-European societies, arguments for a Norse Iron Age are based on recovered finds and later texts (Andrén et al., Citation2006; L. Hedeager, Citation2011; Pearson, Citation2006). As a result, interpretation of prehistoric Scandinavian social systems can only be theoretical. Yet the appearance of the weapon dancer motif in ceremonial contexts during both the Iron and Bronze Ages—often in association with martial elements—lends credibility to the argument presented in this paper. In both periods, weapon dancer symbolism was found in a ceremonial context, emphasizing the various masculine traits associated with Scandinavian warriorhood.

Scandinavian society during both the Norse Iron Age and Indo-European Bronze Age was defined by a warrior aristocracy which thrived/survived due to a culture which emphasized violence as part of the social fabric, representing it as a characteristic social normality (L. Hedeager, Citation2008, Citation2011; Hedenstierna-Jonson, Citation2009; Jackson, Citation2016; K. Kristiansen, Citation2010b). As this culture was based on an oral tradition, the elite of both periods used symbolic structures focusing on violence and masculinity—including motifs such as the weapon dancer—in order to ritually affirm a warrior mentality. This ritual affirmation of warfare as a critical component of prehistoric society allowed local leaders to mobilize large followings and maintain their own chiefly retinues throughout a period of Scandinavian history defined by an unstable, competitive, and violent power structure; specifically by representing the role/profession of a warrior as desirable and socially accepted.

7. Consequences

The similarities between Iron Age and Bronze Age Scandinavian symbolic structures emphasizes the need to continue to re-evaluate current models of social change and development. Rather than viewing the Iron Age and Bronze Age as two distinct periods, future scholarship must continue to approach prehistoric Scandinavia as a period of continuous transformation and development. Only then will scholars reach a better understanding of the rise of socio-political complexity throughout this period in Scandinavian history. Socials structures—including religion and symbolism—are long-lived and persistent, as well as permutative and highly adaptive (Kristiansen & Larsson, Citation2010; Thrane, Citation2013). Consequently, elements such as symbols have the capacity to cross generations due to their ability to touch upon the collective memory which encapsulates mythic knowledge and master narratives.

A potentially beneficial avenue of future research regarding Prehistoric Scandinavian use of symbolic structures to signal warrior identities and mentalities might be to perform an overall comparison of warrior characterisations in Bronze Age rock art, Iron Age material culture, and Medieval Skaldic poems. Each of these symbolic structures seem to emphasize similar ideals and characteristics in regards to what a warrior should be—including traits such as aggression, fearlessness, and strength (see Jesch, 2010; Thrane, Citation2009). Is it possible that such a comparison may reveal a particularly Scandinavian tradition, developing alongside society as it progressed in socio-political development? This would be an interesting avenue of research which would allow the scholarly community to better understand both cultural and socio-political development in Prehistoric Scandinavian society.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Timmis Maddox

Timmis Maddox is a PhD student for the Anthropology department of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in the United States. As a prehistoric archaeologist whose interests lie in Bronze and Iron Age southern Scandinavia, Mr. Maddox’s research focuses on power and the use of symbolic structures—including rituals and symbols—by elite groups and individuals as a means of influencing the organization of communities. His interest in concepts of power have led to studies of identity, territoriality, religion, and conflict; paying particular attention to their role in prehistoric southern Scandinavian social organization. His most recent work, as evidenced by this article, aims to determine how certain strategies of manipulation experienced persistent use throughout the prehistoric period. In doing so, Mr. Maddox hopes to deconstruct the border between the Bronze and Iron Ages, presenting prehistoric Scandinavia as a single period of continuous transformation and development.

References

- Ahlqvist, L., & Vandkilde, H. (2018). Hybrid beasts of the Nordic Bronze Age. Danish Journal of Archaeology, 7(2), 180–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/21662282.2018.1507704

- Anati, E. (2017). Prehistoric art and religion. In B. L. Christensen & J. T. Jensen (Eds.), Religion and material culture: Studying religion and religious elements on the basis of objects, architecture, and space (pp. 103–24). Brepols Publishers.

- Andrén, A. (2014). Tracing Old Norse cosmology: The world tree, middle earth, and the sun in archaeological perspectives. Nordic Academic Press.

- Andrén, A., Jennbert, K., & Raudvere, C. (2006) Old Norse religion: Some problems and prospects. In A. Andrén (Ed.) Old Norse religion in long-term perspectives: Origins, changes, and interactions: An international conference in Lund, Sweden, June 3- 7,2004 (pp. 11–16). Lund: Nordic Academic Press.

- Axboe, M. (1986). Copying in antiquity: The torslunda plates. Studien zur Sachsenforschung, 6 (1), 13–17. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/2326941/Copying_in_Antiquity_The_Torslunda_Plates

- Bastian, M. (2005). The naked and the nude: Historically multiple meanings of oto (undress) in Southeastern Nigeria. In A. Masquelier (Ed.), Dirt, undress, and difference: Critical perspectives on the body’s surface (pp. 34–60). Indiana University Press.

- Bayless, M. (2016). The Fuller Brooch and Anglo-Saxon depictions of dance. Anglo-Saxon England, 45(1), 183–212. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0263675100080261

- Bengtsson, B. (2017). Sailing Rock Art Boats: A reassessment of seafaring abilities in Bronze Age Scandinavia and the introduction of the sail in the North. BAR Publishing.

- Bertilsson, U. (2013). Divine footprints. Traces of cosmological archetypes and prehistoric religion on the rock faces. Papers of the XXV valcamonica symposium (pp. 1–9).

- Bertilsson, U., & Anati, E. (2014). Carved footprints and prehistoric beliefs: Examples of symbol and myth in practice and ideology. Expression, 6(1), 29–46.

- Bonfante, L. (1989). Nudity as a costume in classical art. American Journal of Archaeology, 93(4), 543–570. https://doi.org/10.2307/505328

- Bradley, R. (1999). Dead soles. In A. Gustafsson & H. Karlsson (Eds.), Glyfer och arkeologiska rum (pp. 661–666). Gothenburg University, Department of Archaeology.

- Campbell, D. (2012). Spartan Warrior 735-331 BC. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Coles, J. (1999). The dancer on the rock: Record and analysis at Järrestad, Sweden. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 65(1), 167–187. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0079497X00001985

- Coles, J. (2004). Bridge to the outer world: Rock carvings at Bro Utmark, Bohuslän, Sweden. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 70(1), 173–205. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0079497X0000116X

- Davidson, H. E. (1971). The battle god of the vikings: The first G. N. Garmonsway memorial lecture. In University of York Medieval monograph series (pp. 1–32).

- Denstoredanske (2018). Odinfigur med hornet opsats. [Image]. Available at: http://denstoredanske.dk/Danmarks_Oldtid/Yngre_Jernalder/Mellem_to_religioner_800-1050_e.Kr/Den_gamle_tro (Accessed 09 August 2018)

- Douka, S., Kaïmakamis, V., Papadopoulos, P., & Kaltsatou, A. (2008). Female pyrrhic dancers in ancient Greece. Studies in Physical Culture and Tourism, 15(2), 95–99.

- Earle, T. (1997). How chiefs come to power: The political economy in prehistory. Stanford University Press.

- Fredell, Å. (2003). Bridging images: Pictorial communication of ideology and cosmology in the southern Scandinavian Bronze Age and the pre-roman Iron Age. Göteborgs universitet: Institutionen för arkeologi.

- Glørstad, Z., & Melheim, L. (2016). Past Mirrors: Thucydides, Sahlins and the Bronze and Viking Ages. In L. Melheim, H. Glørstad, & Z. Glørstad (Eds.), Comparative perspectives on past colonisation, maritime interaction and cultural integration (pp. 87–109). Equinox Publishing Ltd..

- Goldhahn, J. (2013). Rethinking Bronze Age cosmology: A Northern European perspective. In H. Fokkens & A. Harding (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age (pp. 248–270). Oxford University Press.

- Gräslund, A. S. (2006) Wolves, serpents, and birds: Their symbolic meaning in Old Norse belief. In A. Andrén (ed.) Old Norse religion in long-term perspectives: Origins, changes, and interactions: An international conference in Lund, Sweden, June 3- 7,2004 (pp. 124–129). Lund: Nordic Academic Press.

- Hamerow, H. (2002). Early medieval settlements: The archaeology of rural communities in North-West Europe, 400-900. Oxford University Press.

- Harding, A. (2015). The Emegence of Elite Identities in Bronze Age Europe. In A. Cardarelli, A. Cazzella, & M. Frangipane (Eds.), Origini: Prehistory and protohistory of ancient civilizations (pp. 111–123). Gangemi Editore.

- Harding, A. (2018). Bronze Age encounters: Violent or peaceful? In C. Horn & K. Kristiansen (Eds.), Warfare in Bronze Age Society (pp. 16–23). Cambridge University Press.

- Hawkes, S. C., Davidson, H. R., & Hawkes, C. (1965). The finglesham man. Antiquity, 39(153), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00031379

- Hedeager, L. (2007). Scandinavia and the huns: An interdisciplinary approch to the migration era. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 1 ()1, 0–17.

- Hedeager, L. (2008). Scandinavia before the viking Age. In S. Brink & N. Price (Eds.), The viking world (pp. 11–23). Routledge.

- Hedeager, L. (2011). Myth and materiality: An archaeology of Scandinavia AD 400-1000. Routledge.

- Hedenstierna-Jonson, C. (2009). A brotherhood of feasting and campaigning: The success of the northern Warrior. In E. Regner, C. von Heijne, L. Kitzler Åhfeldt, & A. Kjellström (Eds.), From ephesos to dalecarlia. Reflections on body, space and time in medieval and early modern Europe (pp. 43–56). The Museum of National Antiquities.

- Helmbrecht, M. (2011). Wirkmächtige Kommunikationsmedien: Menschenbilderder Vendel-und Wikingerzeit und ihre Kontexte. Acta Archaeologica Lundensia, 30(1), 13–539.

- Horn et al. (2018). Warfare in Bronze Age Society. [Image] Available at: http://www.cambridge.org/gb/academic/subjects/archaeology/prehistory/warfare-bronze-age-society?format=HB (Accesed 05 May 2018)

- Iversen, R. (2014). Bronze Age acrobats: Denmark, Egypt, Crete. World Archaeology, 46(2), 242–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2014.886526

- Jackson, P. (2016). Cycles of the wolf: Unmasking the young warrior in Europe’s past. In P. Haldén & P. Jackson (Eds.), Transforming warriors: The ritual organization of military force (pp. 36–49). Routledge.

- Jennbert, K. (2011). Animals and humans: Recurrent symbiosis in archaeology and Old Norse Religion. Nordic Academic Press.

- Kaliff, A. (2005). The vedic agni and Scandinavian fire rituals. A possible connection. Current Swedish Archaeology, 13(1), 77–96.

- Kaul, F. (1998). Ships on bronzes. A study in Bronze Age religion. Text. Vols. 3,1. PNM, Publications from the National Museum.

- Kaul, F. (2017). The shape of the divine powers in Nordic Bronze Age mythology. In B. L. Christensen & J. T. Jensen (Eds.), Religion and material culture: Studying religion and religious elements on the basis of objects, architecture, and space (pp. 199–227). Brepols Publishers.

- Kristiansen, K. (2010a). Rock art and religion: The sun journey in Indo-European mythology and bronze age rock art. In Fredell, Å., Kristiansen, K., and F. Boado (Eds.). Representations and communications: Creating an archaeological matrix of late prehistoric rock art (93–115). Oxbow Books.

- Kristiansen, K. (2010b). Decentralized complexity: The case of Bronze Age Northern Europe. In T. D. Price, & Feinman, G. (Eds.), Pathways to power: New perspectives on the emergence of social inequality (pp. 169–192). Springer.

- Kristiansen, K. (2011). Bridging India and Scandinavia: Institutional transmission and elite conquest during the Bronze Age. In T. Wilkinson, S. Sherratt, & J. Bennet (Eds.), Interweaving worlds: Systematic interactions in Eurasia, 7th to 1st Millennia BC (pp. 243–266). Oxbow Books.

- Kristiansen, K. (2014). Religion and society in the Bronze Age. In Christensen, L., Hammer, O., and D. Warburton (Eds.). The handbook of religions in ancient Europe (77–93). Routledge.

- Kristiansen, K. (2016). Bronze Age vikings? A comparative analysis of deep historical structures and their dynamics. In L. Melheim, H. Glørstad, & Z. Glørstad (Eds.), Comparative perspectives on past colonisation, maritime interaction and cultural integration (pp. 177–189). Equinox Publishing Ltd.

- Kristiansen, K., & Larsson, T. (2010). The rise of Bronze Age society: Travels, transmissions, and transformations. Cambridge University Press.

- Langer, J. (2002). The origins of the imaginary Viking. Viking Heritage Magazine, 4(2), 7–9.

- Larsson, L. (2011). A ceremonial building as a ‘home of the gods’? Central buildings in the central place of Uppåkra. In O. Grim & A. Pesch (Eds..), The Gudme-Gudhem phenomenon: Papers presented at a workshop organized by the Centre for Baltic and Scandinavian Archaeology (ZBSA) (pp. 189–206). April 26th and 27th, 2010.

- Liberman, A. (2005). Berserks in history and legend. Russian History, 32(1–4), 401–411. https://doi.org/10.1163/187633105X00213

- Liberman, A. (2011). Berserk rage through the ages. Valla, 2(1), 132–134.

- Ling, J., Rowlands, M. (2015). The ‘Stranger King’ (bull) and rock art. In Skoglund, P., Ling, J., and U. Bertilsson (Eds.). Picturing the Bronze Age. Swedish Rock Art Series 3 (pp. 89–104). Oxbow Books.

- Ling, J., & Toreld, A. (2018). Maritime warfare in Scandinavian rock art. In C. Horn & K. Kristiansen (Eds.), Warfare in Bronze Age Society (pp. 61–81). Cambridge University Press.

- Ling, J., & Uhnér, C. (2014). Rock art and metal trade. Adoranten (pp. 23–43).

- Ling, J. (2014). Elevated rock art: Towards a maritime understanding of Bronze Age rock art in northern Bohuslän. Oxbow Books.

- Lykesas, G., & Mouratidisof, I. (2005). Dance during the classical period in Greece, Athens and Sparta. Stiinta Sportului, 46(1), 3–20.

- Melheim, L. (2013). An epos carved in stone: Three heroes, one giant twin, and a cosmic task. In S. Bergerbrant & S. Sabatini (Eds.), Counterpoint: Essays in archaeology and heritage studies in honour of professor Kristian Kristiansen (pp. 273–282). Archaeopress.

- Nielsen, K. H. (2005). “ … the sun was darkened by day and the moon by night … there was distress among men … ”—on social and political development in 5th-to 7th-century southern Scandinavia. In U. L. Hansen, C. Hills, B. Magnus, U. E. Hagberg, L. Impe, L. Fr., & C. Lorren (Eds.), Neue Forschungsergebnisse zur nordwesteuropäischen Frühgeschichte unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der altsächsischen Kultur im heutigen Niedersachsen (pp. 247–285). Isensee Verlag.

- Nordberg, A., & Wallenstein, F. (2016). ”Laughing I shall Die!” The total transformations of berserkers and úlfheðnar in Old Norse society. In P. Haldén & P. Jackson (Eds.), Transforming warriors: The ritual organization of military force (pp. 49–66). Routledge.

- Nordbladh, E. A. (2012). Ability and disablity: On bodily variations and bodily possibilities in viking age myth and image. In I. M. Danielsson & S. Thedéen (Eds.), To tender gender: The pasts and futures of gender research in archaeology (pp. 31–63). Stockholm University.

- Pearson, M. P. (2006) The origins of old Norse ritual and religion in European perspective. In A. Andrén. (Ed.) Old Norse religion in long-term perspectives: Origins, changes, and interactions: An international conference in Lund, Sweden, June 3- 7,2004 (pp. 86–92). Lund: Nordic Academic Press.

- Pluskowksi, A. (2006) Harnessing the hunger: Religious appropriations of animal predation in early medieval Scandinavia. In A. Andrén (Ed.). Old Norse religion in long-term perspectives: Origins, changes, and interactions: an international conference in Lund, Sweden, June 3- 7,2004. Lund: Nordic Academic Press, pp. 119–123.

- Price, N. (2002). The viking way: Religion and war in late Iron Age Scandinavia. Department of Archaeology and Ancient History.

- Price, N. (2008). Bodylore and the archaeology of embedded religion: Dramatic license in the funerals of the vikings. In D. Whitley & K. Hays-Gilpin (Eds.), Belief in the past: Theoretical approaches to the archaeology of religion (pp. 143–167). Left Coast Press, Inc.

- Price, N., & Mortimer, P. (2014). An eye for odin? Divine role-playing in the age of sutton hoo. European Journal of Archaeology, 17(3), 517–538. https://doi.org/10.1179/1461957113Y.0000000050

- Price, T. D. (2015). Ancient Scandinavia: An archaeological history from the first humans to the vikings. Oxford University Press.

- Raffield, B., Greenlow, C., Price, N., & Collard, M. (2016). Ingroup identification, identity fusion and the formation of Viking war bands. World Archaeology, 48(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2015.1100548

- Rees, O. (2018). Going berserk: The psychology of the Berserkers. Medieval Warfare, 2(1), 23–26.

- Rood, J. (2017) Ascending the steps to Hliðskjálf: The cult of Óðinn in early Scandinavian aristocracy. ( PhD thesis). University of Iceland. Retrieved from August 20, 2017, from https://skemman.is/handle/1946/27717

- Schjødt, J. P. (2011). The Warrior in Old Norse Religion. In G. Steinsland, J. V. Sigurdsson, J. E. Rekdal, & I. Beuermann (Eds.), Ideology and power in the viking and middle ages: Scandinavia, Iceland, Ireland, Orkney, and the Faeroes (pp. 269–297). Brill.

- Sjöberg, R. (1994). Diagnosis of weathering on rock carving surfaces in northern Bohuslän, Southwest Sweden. In D. A. Robinson & R. B. G. Williams (Eds.), Rock weathering and landform evolution (pp. 223–244). John Wiley and Sons.

- Skoglund, P. (2013). Images of shoes and feet: Rock-Art motifs and the concepts of dress and nakedness. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 46(2), 159–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00293652.2013.836563

- Skoglund, P. (2016). Rock art through time: Scanian rock carvings in the Bronze Age and Earliest Iron Age. Oxbow Books.

- Skoglund, P., Nimura, C., & Bradley, R. (2017). Interpretations of footprints in the Bronze Age rock art of south Scandinavia. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 83(1), 289–303. https://doi.org/10.1017/ppr.2017.2

- Skogstrand, L. (2016). Warriors and other men: Notions of masculinity from the late Bronze Age to the early Iron Age in Scandinavia. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd.

- Speidel, M. (2002). Berserks: A history of Indo-European mad warriors. Journal of World History, 13(2), 253–290. https://doi.org/10.1353/jwh.2002.0054

- Speidel, M. (2004). Ancient Germanic warriors: Warrior styles from Trajan’s column to Icelandic sagas. Routledge.

- Storgaard, B. (2001). Himlingøje: Barbarian empire or Roman implantation? In B. Storgaard (Ed.), Military aspects of the aristocracy of barbaricum in the roman and early migration periods (pp. 95–111). National Museum of Denmark.

- Storgaard, B. (2003). Cosmopolitan aristocrats. In Jørgensen, L., Storgaard, B., and L. Thomsen (Eds.). The spoils of victory-the north in the shadow of the roman empire (106–125). National Museum of Denmark.

- Swedish Rock Art Research Archives (2008). The so-called Dancer at Järrestad. [Rubbing] Swedish Rock Art Research Archives/Österlens museum, Source: id: 276.

- The Viking Rune. (2018). Odin as Weapon Dancer. [Image] Available at: https://www.vikingrune.com/2009/10/odin-as-weapon-dancer/ (Accessed: 15 June 2018)

- Thrane, H. (2009). Aggression, territory and boundary - and the Nordic Bronze Age. In L. H. Olausson & M. Olausson (Eds.), The martial society: Aspects of warriors, fortifications, and social change in Scandinavia (pp. 11–25). Stockholm University.

- Thrane, H. (2013). Scandinavia. In H. Fokkens & A. Harding (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the European Bronze Age (pp. 746–767). Oxford University Press.

- Vandkilde, H. (2012). Warfare in Northern European Bronze Age societies: Twentieth-century presentations and recent archaeological research inquiries. In S. Ralph (Ed.), The archaeology of violence: Interdisciplinary approaches (pp. 37–63). State University of New York Press.

- Vandkilde, H. (2013). Bronze Age voyaging and cosmologies in the making: The helmets from viksø revisited. In S. Bergerbrant & S. Sabatini (Eds.), Counterpoint: Essays in archaeology and heritage studies in honour of professor kristian Kristiansen (pp. 165–177). Archaeopress.

- Vandkilde, H. (2014). Breakthrough of the Nordic Bronze Age: Transcultural warriorhood and a carpathian crossroad in the sixteenth century BC. European Journal of Archaeology, 17(4), 602–633. https://doi.org/10.1179/1461957114Y.0000000064

- Viking Archeurope (2018). Finglesham Buckle. [Image]. Available at: http://viking.archeurope.info/index.php?page=finglesham-buckle (Accessed 05 May 2018)

- Vogt, D. (2011). Rock carvings in Østfold and Bohuslän, South Scandinavia. An interpretation of political and economic landscapes. The Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture, Novus forlag Oslo.

- Vogt, D. (2014). Silence of signs—power of symbols: Rock art, landscape and social semiotics. In D. Gillette, M. Greer, M. Hayward, & W. Murray (Eds.), Rock art and sacred landscapes (pp. 25–49). Springer.

- Wade, J. (2016). Going berserk: Battle trance and ecstatic holy warriors in the European war magic tradition. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 35(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2016.35.1.21

- Wang, L. (2017). Freyja and freyr: Successors of the sun: On the absence of the sun in Nordic saga literature. University of Oslo.

- Williams, G. (2008). Raiding and warfare. In S. Brink & N. Price (Eds.), The viking world (pp. 193–203). Routledge.

- Winter, L. (2005). Rock art, landscape and interaction: Examples from Bronze Age Bohuslän. Traballos De Arqueoloxia E Patrimonio, 33(1), 123–139. https://digital.csic.es/handle/10261/6206