Abstract

This study seeks to provide evidences on the distinctive creative elements of the Jukun “keku” dance music among other indigenous music of the sub-Saharan African cultures. An examination of its creative milieu and the musicians in the context of composition, performance and cultural implications were carried out through an ethnographic procedure. To achieve this, the study adopted a qualitative study design, using the Wukari Jukun community as its research area. The sample study purposively selected 25 persons who are the custodians and audience of the “Keku” dance. Through the structural analysis of the data, the findings show a significant distinction in the creative manipulation of the melodic and rhythmic motives of the music compared to similar traditional genre from the region. The implication of these findings, therefore, is a need for continuity, sustainability and wider visibility of the indigenous music.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The article “Documenting distinctive features of ‘Keku’ dance ensemble of the Jukun nation of the sub-Saharan Africa” is a documentation of an endangered musical tradition of the Wukari Jukun community of the Southern Taraba State, Nigeria. It discusses the philosophy that informed the composition and performance of the musical style. The article went a step further to argue against the homogeneous treatment of African music and its effect on the relatively unknown musical cultures. The study provides insight for further investigation on the socio-cultural, economic, and political engagement of the Jukun people.

1. Introduction

A wide range of dance music ensemble of the sub-Saharan Africa has undoubtedly received scholarly attention over the decades. Early scholars like Ward (Citation1927), Varley (Citation1936), Merriam (Citation1951), Boulton (Citation1957), Nketia (Citation1986), Akpabot (Citation1986) and Euba (Citation1989), and more recent literatures as found in the works of Turino (Citation2000), Omojola (Citation2001), Agawu (Citation2003), Blench (Citation2004), Welsh (Citation2004), DjeDje (Citation2008), Mbaegbo (Citation2015), Onyeji (Citation2016), and Malcolm (Citation2019), etc., extensively discussed the characteristics of African indigenous music. This, however, is not without the exception of some endangered musical traditions like the Jukun and other cultures from the region. For example, Malcom, writing about African Music traditions observed the posterity and complexity of its elements, as well as the classification of the instruments which in most cases form the different ensembles found in Africa.

This study proposes an argument against the homogeneous treatment of the creativity and performance of African music which consequently has submerged the authenticity and visibility of many of its traditional music. The judgmental comments of some researchers of African music as argued by Agawu and other African scholars have been called to question, considering the ratio of African indigenous music reviewed against the total number of cultures of the continent. Nigeria alone as a sub-Saharan African nation records well over 1000 cultures with unique musical practices out of which less than 50 has been thoroughly investigated. It is based on this erroneous approach that we seek to document the distinctive idioms and elements of Keku dance music of the Jukun people. Rather than emphasising the limitations encountered in accessing these endangered cultures, we propose that a deliberate attempt at fishing them out and documenting them along the already discovered musical cultures like the Nigerian Yoruba, Igbo, Hausa musical cultures; the Ghanian Akan, Ewe, Akplu and Dagbon musical cultures; the Tanzanian Maasai and Bantu musical cultures among others.

In comparison with similar musical instruments and ensembles found in the sub-Saharan Africa such as the Imzad/Amzad of the Tuareg people, the Gambian Fulbe Nyanyeru, Tanzanian Fiddle – Zeze; Ghana Dagbamba fiddle – Gondze; as well as the “lute found in central Africa, the Zither (Bassa) of Liberia and the Inanga or through zither of Ruanda” (Gansemans, Citation1988), the Keku ensemble consist of only three musical instruments, namely, the Keku (fiddle), Akacha (shakers) and the Akwe (calabash). Through the ethnographic survey of its creative milieu and the musicians in the context of composition, performance and cultural implications Keku dance music ensemble has demonstrated some notable distinctions in its melodic and rhythmic formations and instrument part relationship worthy of scholarly attention.

2. Methodology

This study engaged an interpretive ethnographic approach hinged on the musical theory of continuity and change (Herskovits and Bascom (Citation1975)) also known as cultural dynamism in reviewing the documented characteristics of African music in the light of “Keku” dance music. Through interview, observation and participation, primary data for this study were gathered with the aid of audio-visual recorders, music manuscripts, note pads etc., since there are no detailed written documents on the subject. Printed sources that discussed the characteristic of African music were also consulted. The sample study purposively selected 25 persons who are the custodians and audience of the “Keku” dance. Transcription of the recordings was done to extract the distinctive idioms and elements of the music. Structural and comparative analysis of the data was carried out to validate the result of the study.

3. Generalizing African music

African music scholarship has moved away significantly from the generalizing approach of the earlier years to ethnographic studies that focus on specific traditions. See, for example, the works of Euba (Citation1990), which studies Yoruba music, Kwasi Ampene (Citation2005), which focuses on Akan culture, and DjeDje (Citation2008), which examines the music of Fulbe, Hausa, and Dagbamba ethnic groups. These studies draw attention to the fact that Africa is a vast and culturally diversified continent, though viewed as homogeneous by appearance, they exhibit unique cultural values and creativity. To be more specific, music creation in Africa is completely unique to respective cultures irrespective of the similarities. These similarities may doubtlessly compel an assumption of homogeneity of its characteristics. Similar musical instruments are found across Africa, but a more careful look into the construction, tone dynamics, and techniques employed in playing the instruments in each culture are quite distinct, as well as the ensemble formation and performance. However, the documentation of the selected musical traditions upon which such limiting conclusions were drawn has at least created some credible global awareness of African music.

Blench (Citation2004), observed that “globalization is rapidly impairing traditional African music via homogenization and the escalation of profit-driven global forms”. As beneficial as globalization may be, so has it indirectly sieved out some core traits of African indigenous practices that seems unprofitable to the powers that be. There exist a wide range of unknown African indigenous musical practices that are capable of increasing the content or nullifying the general conclusions about the music. A closer look at the submission of Stapleton and May (Citation1989), on the characteristic of sub-Saharan African music as being of “strong rhythmic interest” that exhibits common characteristics in all regions of this vast territory, to form one main system may not necessarily justify the Ladzekpo (Citation1996) affirmation of the profound homogeneity of approach of West African rhythmic techniques. As earlier pointed out, the vastness of African continent and cultural practices, has suffered so much of undermining treatment in its entirety so far. “Ethnicity is not merely a political mode of identification, locally and globally, but an essential part of the way people imagine their place in the world and the way they reflect upon and sense their position. Ethnic belonging is existentially important in national and trans-national contexts” (Gravers, Citation2007). Traditional heritage of which music is paramount informs the ethnic identity of the people, and muddling it up is simply denying the existence of such ethnic groups. Irrespective of the general features of African music, the distinctive features should also be recognized and captured as much as possible. For instance, “African rhythms are complicated as compared to Western rhythm” (Munyaradzi & Zimidzi, Citation2012), is a popular statement in the comparison of African and Western music. But in the real African context, African music to the owners is as simple as the air they breathe! The statement complex or complicated, monotonous or off beat may be derogatory and could connote not worth going after, thus discouraging further search into the remaining cultures and maintaining the status quo.

“The history of African music has always been of some interest to researchers, but the absence of any follow-up on some published volumes says much about the interests of ethnomusicologists and the lack of interaction with other disciplinary scholars in African history” (Blench, Citation2004). This observation is very true about the Jukun culture; no substantial literature on Jukun music has been published compared to the volume of publications on the history of the people. For instance, the Jukun tribe is just one of the 51 ethnic groups found in Taraba state Nigeria, out of which barely four has been researched. It is obvious that no amount of archaeology or other types of reconstruction are going to recover the music in Africa’s past; this doubtlessly is the implication of the fusion of the known features with relatively unknown musical elements of Africa which have kept majority of the cultures in the dark and subjected to extinction as a result of civilization. Blench further argues that one intriguing aspect of broader categories of musical forms in Africa is their relative conservatism over extensive regions of the world. He provided examples of the heterophonic ensembles that characterize South-East Asia and the monody that is found all the way from North East India to the edges of Europe as being quite distinctive and admit of no real exceptions. Virtually all the musical instruments of the West have their replica in Africa which may justify the tendency of finding similar characteristic of the opposing cultures.

Therefore, in agreement with Blench’s submission that “Individual ethnic groups, their languages and their cultures, are strongly linked but should never be confused. Indeed, it would be disingenuous to claim that there are no general correspondences between language and ethnic distribution, especially in the case of minority groups. Nonetheless, it must be emphasized that the social definition of an ethnic group has many aspects, of which language is just one” (Blech, Citation2013). It is then worthy of note that similarity in cultural values does not necessitate cultural homogeneity. Music like language is integral to any cultural practice and should be treated as such with high degree of carefulness. Musical performances arguably saturate the daily lives of indigenous people of Africa. Therefore, failing to research such music is a direct abandonment of their culture.

4. Causes and consequence of general view of African music

The problem of generalizing African traditional music can be traced to some limiting factors encountered by musicologist both within and outside Africa. In the literature, three major problems have been identified in ethnomusicology: the location of disciplinary borders; the problem of translation, and “a network of political and ideological matters” (Agawu, Citation2003:70). These listed factors directly provide insights into the under exploration of “Keku” dance ensemble of the Jukun. To start with, crossing disciplinary borders and eradication of research barriers prove to provide lasting solution to limited literatures on the musical cultures of Africa. Drezek et al. (Citation2008) while discussing on new approach of crossing disciplinary boarders recommended aside the FIGER program which entails developmental assessment of “concrete, interdisciplinary results”, such as numbers of interdisciplinary grants written/awarded; number of interdisciplinary conferences attended; or number of interdisciplinary papers published and so on. They are of the opinion that developments of suitable epistemic beliefs—i.e., a scheme by which scholars can begin to deliberately channel the knowledge composition procedure both within the scope of their primary discipline and other disciplines may yield better result.

Secondly, accurate translation of data is core to authentic research presentation. Collier et al. (Citation2011) noted that “verification of the existence of data is essential to find it, followed by the means of accessing it and ability to interpret the annotations, properties and background information of the data”. The general opinion of some scholars on African music tends to indirectly suggest non-existence of data to start with. Also, other limiting factors are tied to policy and cultural issues that restrict access of non-initiates to the integral content of the cultural practice. Edewor et al. (Citation2014), noted the preference for cultural homogeneity that was sustained and strengthened in the twentieth century, as a result of the occurrence of communal violence in the 1950s and 1960s in Nigeria. The violence in Nigeria similar to countries like Bangladesh and India, as consequently strengthened the political scientist’s opinion about ethnically diverse societies. Their claim is that, such diversity will inevitably lead to conflicts, or that at least undermine the sense of national belonging or the loyalty toward the nation-state. Also, expressing a fearful concern about the respect of social order, they believe that shared identity among the members of a society fosters a feeling of general trust among the people. Therefore, national identity may not be achieved as a result of increasing cultural diversity in a country like Nigeria. Contrary to this view, however, the vilification of ethnicity since independence in 1960 has doubtlessly encouraged inequalities in interpersonal incomes, imbalanced development rate, and submergence of cultural heritage among various communities in different geographical areas of the country, to mention a few.

Similarly, Mustapha’s observation of the tripodal regional administrative structure of the 1950s on Nigeria has availed each majority ethnic group a region of its own as a form of main context for ethnic mobilization and contestation. According to him, “Nigeria has about 374 ethnic groups that are broadly divided into ethnic ‘majorities’ and ethnic ‘minorities’. The major ethnic groups are the Hausa-Fulani of the north, the Yoruba of the southwest, and the Igbo of the southeast. These three ‘hegemonic’ ethnic groups constituted 57.8% of the national population in the 1963 census. All the other ethnicities constitute different degrees of ‘minority’ status” (CitationMustapha 2006). It is important to note that while this amalgamation may be helpful for easy governance, it is detrimental to the endurance of indigenous cultural heritage like music. The uniqueness of the people’s cultural practices, and the indefectible, relationship that exists between the indigenes, their territories and their leaders among other cultural elements, should not be undermined. Mustapha further explained that the “Colonial administrative regionalism consolidated the link between ethnic distinctiveness and administrative boundaries: Hausa-Fulani in the north; Igbo in the east and the Yoruba in the west. The ethnic minorities in each region were forced to accommodate themselves the best they could in each region”. The so-called wazobia syndrome has crept into the academic research domain, whereby most attention were given to these major cultures as manifestations of inequalities, at the expense of other cultures they have assimilated, and subsequently used as a yardstick to describing the Nigerian indigenous music for instance. These afore-mentioned observations, therefore, justify the huge gap in the ratio of documented indigenous musical heritage in Nigeria and sub-Saharan African at large against those on the verge of extinction. Conservatism on the part of custodians of some traditional African music has made it more difficult for researchers to access and document, respectively. Consequently, misinterpretation and distortion of available data are indubitably false and incomplete research outcomes.

Also, despite the promising improvement in the ease of data collection in African countries today, there are other factors that must be considered as highlighted by Riley when discussing artificial barriers to data sharing in “making a case for international sharing of scientific data symposium” (Riley, Citation2012). Issues about quality, access and affordability of data collection devices were raised. His observation was that the most paramount challenge faced in Africa is the shortage of competent hands on the technical knowhow of routers and other gadgets necessary for effective research. Various technical research aids available for ethnomusicological data collation and analysis are still unexplored by many African researchers, as a result of unaffordability of the gadgets and inadequate training on such devices.

5. The socio-cultural background of Keku dance

The performance of Keku dance is not without some socio-cultural philosophies such as identity and emancipation, aesthetics and ethics, religion and myths and so on. The Jukun culture like other cultures of the world is guided by specific beliefs and ideas through which their daily activities are shaped. The performance of Keku dance is saturated with various cultural philosophies of the Jukun, ranging from the construction of the instruments to the functionality of the genre to its group taxonomy, instrument part relationships, dance formation, as well as the choice of melodic phrase, text and the costume used.

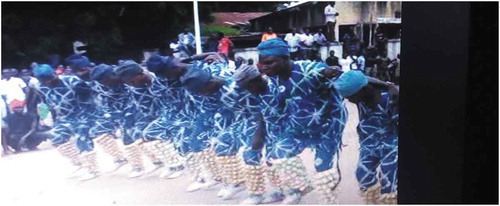

Considering the choice of materials used in the construction of the musical instruments- (i) the calabash (ii) alligator skin (iii) horsetail (iv) bent iron rod and (v) carved sticks from Marlena wood; all signify strength and tenacity. To the Jukun, strength combined with patience is highly rewarding and imbibed in any of her human interaction. The calabash drum left open signifies transparency. The Jukun abhors insincerity during any form of contract. The synergetic interaction of the instruments and the dancers connote an inter-dependence of Jukun people in achieving better result in any endeavour of life. They believe that no man is an island of strength and knowledge. The people have an adage that “no man can survive the huddles of life on his own”. The same philosophy is displayed towards the end of the dance, when the dancers form a straight line with hands joined shoulder to shoulder to form a single chain, producing a perfectly coordinated unison and rhythm in response to the melody and rhythm of the instruments. All through the performance, individual skill of the members of the society is appreciated and admired as well as displayed.

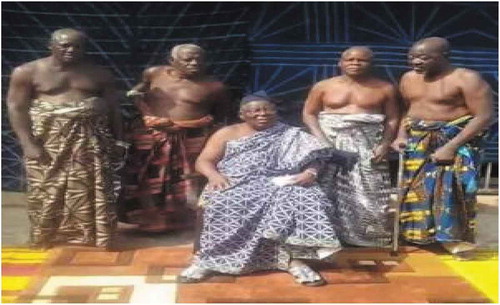

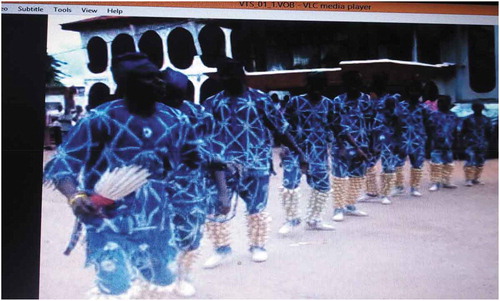

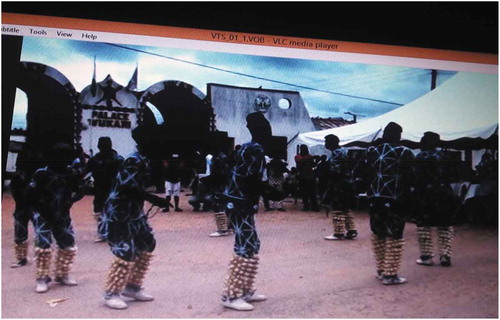

As earlier discussed, the Jukun people are known for their symbolic lifestyle displayed through colours, shapes, patterns, animals and insects among others. The choice of Adire (a traditional Jukun blue attire with fishbone-like white stripes) by the Keku dance ensemble as costume, harmonizes with the overall philosophy of the dance. According to Jukun philosophy of colours and shapes; blue colour represents the supremacy of God over all while white connotes peaceful coexistence. The formation of circle and age group representation among the Keku dancers portray continuity of the music tradition.1-8

6. The Jukun people

According to Dauda (Citation2017) and the researcher’s oral interview with King Shekarau (The Aku-Uka of Kwararafa Kingdom on 25 February 2017), the Jukun are an ethnolinguistic group or ethnic nation in West Africa which came from the Arabian Peninsula through Western Sudan. They are a direct scion of the Kwararafa nation. Kwararafa was a confederation, with the Aku Uka as the divine and supreme leader. The Jukun are habitually found in Taraba, Benue, Nasarawa, Plateau, Adamawa, and Gombe states and extend to the Benin Republic, far outside Nigeria, well into Niger, Cameroun and Chad. In fact, they are found in 27 out of 36 states in Nigeria, including Arochukwu and some parts of Bendel; certain parts of the North, South-South, such as Cross River State, part of Borno like Biu. In Okunna and Gausa (Citation2014), Zakaria submitted that “the Jukun (PaJukun) is largely recognized as the Wapan whose original history is very esoteric. Wapan (or Jukun) is the general name by which the people call themselves and is widely accepted. The word, Jukun simply means human being and this place we are. Wukari in Jukun language is interpreted as a better place. It is the headquarters of the Kwararafa kingdom” (King Shekarau, 2017).

Similarly, Agbu et al. (Citation2019) note that there are many dialects of Jukun but the name Jukun stands as a general name for all the dialects, because the dialects spoken at Wukari have a remarkably differentiating feature with the dialects of the other groups. However, when one is talking of one indivisible tribe, it is referred to as Adankoye.

Before the advent of Christianity, the Jukun people were adherents of traditional religion. This fact can also be said of many tribes in Nigeria. In spite of the influence of Christianity, the language, socio-cultural, political and religious beliefs of the Jukun people remain intact to a large extent. Their regard for social justice, equity and freedom of individuals without any form of discrimination about religion, gender or age cannot be overstated.

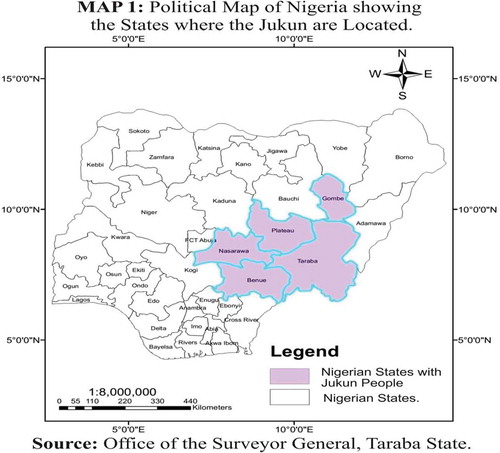

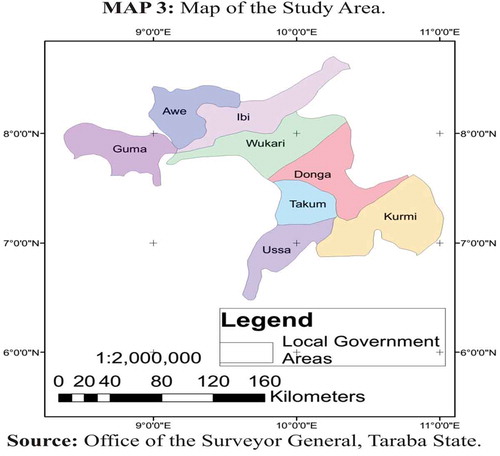

Geographically, the landmass occupied by the Jukun (i.e. Wukari Local Government Area) is positioned between latitude 7°51′N, 9°47′E and longitude 7.85°N, 9.783°E. (Google maps; retrieved September 2017). Created in 1976, Wukari Local Government Area was prorated into 15 traditional central zones, namely Akwana, Arufu, Assa, Avyi, Bantaje, Chinka, Chonku, Gidan-Idi, Jibu, Kente, Matar-Fada, Nwokyo, Rafin-Kada, Tsokundi, and Wukari. The area of Jukun inhabitation is bounded by Abinshi to the west, Kona to the east, Pindiga to the north and Donga to the south (Figure 1-3).

Figure 1. Map of Nigeria showing states with Jukun people (Dauda, Citation2017).

Figure 2. Map of Taraba State (Dauda, Citation2017).

Jukun people are predominantly farmers and warriors. Simply put, their socio-cultural life rallies around agriculture. The supreme deity (Yaku-Keji)’s worship is principally saturated with prayers for productivity and peace. Over time, the socio-cultural, economic and religious ideas, as well as daily experiences of the Jukun people, have been communicated via music. Traditionally, the Jukun employed the Gaya system of farming; a system whereby the workforce for farming activities constitutes communal efforts of friends, neighbours and relatives. Crops like yam, melon, maize, millets, beans, corn, guinea corn, rice, soya beans, groundnut, cassava, vegetables and fruits such as orange, watermelon, sweet melon and mango and so on are largely cultivated by the Jukun. Also, they rear livestock like goats, pigs, cows, sheep, and poultry. The riverine areas of Jukun are predominantly inhabited by fishermen.

The Jukun have respect for the culture and this is daily reflected in their traditional attire. The Jukun men wear a dark-blue traditional cap called Abishi-Shaki. Other traditional items of clothing are Apu, Adire and Akya. These are mostly used for cultural festival and on social occasions (Aboshi, Citation2010). Okunna and Gausa (Citation2014) affirm that cultural garb as used by the Jukun is an aspect of their tradition which emphasizes the notion of brotherhood recognition. The traditional Jukun attires are made from different patterns, colors and weaves for different occasions and purposes. Among which are; Kadzwe, Ayin—po, Adire (a blue attire with fish bonelike white stripes, often used during cultural festivals) and Baku, while the Kyadzwe is used by the Jukun rulers for royalty. The Jukun lifestyle is saturated with symbols. These are evident in the way and manner they adore the Aku (i.e. the King). For instance, among other symbols of the Jukun is the Circle shape, which is a symbol of continuity. Jukun people are resolute about the perpetuity of their cultural heritage from one generation to the other. Also, in terms of color Gausa (Citation2013) affirms the symbolic representations of colors among the Jukun, for example, the Red colours (Abukhan) signify the warring attribute of the Jukun tribe, Black colour (Abu pe) on the other hand describe the king as a rainmaker; the white colour (Abu Fyen) connotes the peace-loving nature of the Jukun, while the supremacy of God over everything is represented as blue colour. They also revere some reptiles and insects such as crocodiles, chameleon and scorpion. The submission of the Jukun oral tradition narrates the assistance the crocodile accorded them when crossing the river when they were being pursued by their enemies and subsequently made a life covenant of reverence with the reptile. Till date, music, dance, color, shapes and motifs, as well as symbols, are important means of communication among various Jukun ethnic groups. However, in Dauda (Citation2017), while comparing the Jukun with their neighbors in terms of leisure and entertainment, it is stated thus “The Jukun are not musical people like their neighbors the Munshi, but they have a variety of drums including the hour-glass drum with bracing strings, various double-membrane drums, and the large single membrane drums which are beaten while standing on the ground.”

In agreement with the words of Dauda, contrary to Meek’s assumption, resent findings present a clear indication that leisure and entertainment were obtainable during the Jukun pre-colonial days and most importantly were saturated with music as revealed by further researches by other historians like Grace, Ake Yamusa in her Clock of Justice, etc.

7. Jukun music

The music of the Jukun People of the Benue river basin of Nigeria is one of such music of the African culture that has received little or no scholarly attention so far. The Jukun possess a wide range of musical genre such as Akishe dance (during marriage ceremonies), Ajo-Niku (farming dance) Ajo-Bwi, Agyogo, Garaza, Ajo-Kovo and Keku (Goge) dance among others.

Recent historical investigations on Jukun cultural practices described the Jukun as music lovers. During the pre-colonial Jukun era, songs were mostly composed for religious worship of deities like Akuwahwan, Akuma, Kenjo, and Yaku-Keji to express their allegiance and thanksgiving as well as the presentation of various petitions. Among the Jukun, music is seen as an instrument of discipline and social control as well as an effective means of communicating acceptable cultural moral values of the people and sensitization tool for an excellent result. A good example as cited in Dauda (Citation2017) is found during the Jukun pre-colonial society. During this era, communal farming called Aniku was encouraged and was accompanied with music during which the farmers competed among themselves as the drummers played. Composers sang to praise the farmers, energizing them as they tilled the soil.

History also has it that the Jukun are notable warriors, thus during battles they employ songs and incantations to solicit for supernatural assistance and encourage the soldiers as they engage in territorial defense or expansion. In the same vein, during Jukun’s social celebrations such as marriage ceremonies, house warming, coronations, naming ceremonies, and the likes, songs were composed to suit the particular occasion. The functionality of music among the Jukun also extends to its mystical and curative potential in the treatment of spiritually, psychological and emotionally induced disorders.

A critical look into Adamu’s submission in Dauda (Citation2017) reveals that until a few years ago, all royal drummers and praise singers of the Aku-Uka were Hausa people. Since they were born and brought up among the Jukun, they were fluent in the Jukun language. Adamu also states that the royal brass wind instruments (Algaita and Kakaki) were always played by the Jukun themselves. Here, Dauda’s submission presents music as one of the major stances of intergroup and political relation in the pre-colonial Jukun era. Traditions demand continuous praise of the king, as a result of which there existed palace drummers and singers who composed and sang praises of the Monarch (Aku-Uka) daily as well as a special musical presentation during specified occasions.

Jukun traditional musical instruments are made up of different kinds of drums such as tiny twin metal pot drums, calabash drum, wooden drums and hourglass drums; zithers; flutes; trumpets; fiddle; gongs and shakers. Virtually all Jukun music is referred to as Ajo meaning dance, probably because of their energetic daily lifestyle. Jukun dances among the women folk mostly engage the shoulder, the neck supported forward and backward movement of the hands, either held in a fist or stretched forward in a descriptive gesture with the entire body half bent. The dancing posture of the men folk is slightly different from that of the women, with a more upright posture sill engaging the shoulders and the neck and seldom stamping of feet in harmony with the rhythm of the drum, and with their right hand holding a hand fan made of feather to fan themselves majestically while dancing; sometimes swinging to left and right sides.

Jukun cultural festivals exhibit different social masquerades like- Agba-Keke, Ashama Agashi, Akuma, Akumaga, Nyadodo, Atukon, Aku-wa-shon, Adashan and Anarik each of which is characterised by peculiar dance, song and musical instrument. Most of the Jukun indigenous dance groups and musicians are identified with distinct attire most of which are made from Adire traditional Jukun attire. In practice, the musical tradition of the Jukun is not characteristically far from other indigenous Nigerian musical practices. Adeogun (Citation2006), when discussing pre-colonial Nigerian music, observed that other typical historical contents of musical practices in Nigeria include emphasis on spontaneous creation, performance-composition and skilled improvisation, evident in the use of drums as well as the accentuation of call and response in vocal and instrumental techniques, lyrical content and a colossal dependence on the performer’s analytical dexterity. And, this is dependent on the quality or effectiveness of the music.

Jukun traditional music is extensively functional and is mostly in call and response form, this could be between voice and musical instruments or vocal leader and chorus style. The composition and performance of musical pieces during ceremonies and festivals are usually spontaneous as demanded by the occasion. It is a constant phenomenon to see various kinds of skilled improvisations from the vocalist, instrumentalists as well as the dancers. Usually, these periods of improvisation among the Jukun is to showcase the holistic strength and brilliancy of the group. Since virtually all Jukun music is described as dance, there exists an extensive use of drums. Compared to their neighbors in the northern region of the state, the music of the Jukun processes reveals some minute Islamic influences.

8. Keku as an instrument and musical style

The term Keku can be treated as a musical instrument and when combined with other elements and instruments, could be referred to as an ensemble. Keku as a musical style is best expressed in the context of its construction, functionality, group taxonomy, instruments and instrument part relationships, performance techniques and the consensus of its existence among the Jukun. Keku as an ensemble is accompanied by the Akwe (calabash drum) and the Akacha (leg shakers) to create a percussive effect. The performance of keku dance is constantly characterized by a leader/chorus relationship common with African music performance, making variations or improvisations possible on short melodic and rhythmic motives. Keku being a simple solo instrument, when manipulated skillfully, produces synchronous sounds by producing overtones with the bow. Also, the Akwe (calabash drum) and the Ashaka (shakers) both supply the percussive quality peculiar to the music. The melodies are made up of two balanced phrases that are often in a call and response performance style, initially between the fiddle and voice and later transferred to the musical instruments. The lead instrument usually builds on variations or improvisations on short melodic motifs, which are repeated and sustained throughout the performance.

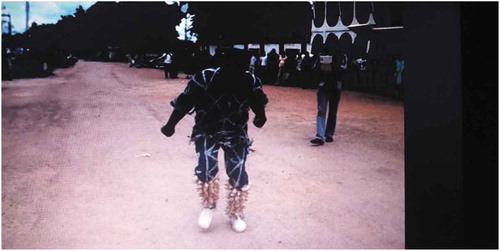

The performance of Keku dance is often in six movements in a cyclic form expressed in slow, fast and very fast tempo, respectively. The Akwe and the Akacha maintain the rhythmic dynamics of the dance while producing pleasurable percussive sounds that inspire the dancers. Density and motion broadly characterize the performance of keku dance, coupled with high degree amplitude. This is because it is mostly an outdoor performance. The performance of Keku is peculiar to the Jukun and plays a significant traditional role of conveying the new king from the coronation site to the palace. Although in recent times, due to civilization, its performance is now extended to other major celebration of the people. It is open to any interested member of the society and still maintains its original musical instruments and modes of performance with drastic modifications of the costume to satisfy aesthetic demands of civilization. The music like many African heritages is maintained and transferred to the younger generation by observation, training and participation. Initially, the performance of keku dance involves both men and women, but this gradually fizzled out leaving it as an exclusive men dance ensemble because of the vigor required in its performance.

9. The origin and philosophy of Keku dance

Keku Dance, as earlier discoursed, is peculiar to the Jukun. The instrument (Keku) is similar to the popular fiddle, Goje. According to the oral tradition narrated by Mr Fari (14 April 2017), it was part of the indigenous musical heritage of the Jukun right from Yemen. Due to the portable nature of the fiddle, it was able to survive the hurdles of Jukun migration over many decades. Keku is a mono-stringed fiddle with a calabash resonator; it is reported to have originated and almost predominantly played by the Sahel and Sudan of West Africa with sparsely vegetated grassland terrain. Philosophically speaking, the performance of Keku dance is a reflection of the communal values of the people. Right from the beginning of the performance to the end, the overall Jukun philosophy of unity and peace is emphasized. Nzewi (Citation2010) wrote that the philosophy behind African music creation is closely linked to the African philosophy of life.

10. Membership

Presently, membership of the ensemble is restricted to the interested male counterpart of the community. According to Mr Istifanus (14 April 2017), a member of the group, there is no age barrier to being part of the group; only that preference is given to younger people for posterity purpose. Members are trained through an active and consistent observation and participation during rehearsal and actual performances. The Keku dance ensemble is characterized by high level of discipline; members are expected to be of noble conduct in the society. The group also possesses a constituted line of hierarchy for proper administration and discipline. Although during event performances, highly skilled dancers are showcased, there is no limit to the number of its members.

11. Composition of “Keku” dance music

The task of music composition is primarily laid on the Keku (fiddle) player, who initiates the theme of the performance as informed by the event in question. “During an interview session with the group, Mr Ibrahim (the fiddle player on 14 April 2017) submitted that most of the melodies played are familiar folk songs that address various issues in the community and are rephrased to satisfy the purpose of the event.” However, being an instrumental music, the chosen melody is usually established at the procession stage of the performance and improvised upon to form variations and developments of theme throughout the performance.

12. Characteristics of Keku dance music

The Keku dance music is distinctively known as an instrumental genre. It features brief vocal responses at the initial part of its performance. It is in six major cyclic movements. The vocal parts are in response to the melodic theme from the fiddle. The dance part of the music, is actually a means of playing the third instrument – Akacha (the foot shakers/rattles).

13. The exposition

The exposition is the opening section of the music. It introduces the theme which is improvised upon as the variation. This section of the music is performed at a moderately slow tempo. It is a combination of the three instruments and voice. The Keku plays the leading role here by making the call, while the voice responds in unison by imposing suitable texts on the melodic idea in reference to the prevailing event. The refrain of the subject ushers in the second movement in a fast tempo as a variation of the main theme.

14. Instrument and instrument part relationship

Contrary to the general notion about African music, Keku dance is majorly an entertainment genre. In terms of its instruments and instrument part relationships, there is an exchange of leadership role between the instruments as the music proceeds. This comes in the case of the Western symphony. This is unlike the general notion of the prominence of the lead drummer in African music. At the beginning of the music, the Keku being a melodic instrument take the leading role by announcing the opening motive of the music, while the other instruments play the accompanying role. Subsequently, as the music proceeds, the Akwe takes over the leadership role by dictating the rhythmic motives while the dancers (with the Akacha) and the Keku follow. When the Akacha takes over the lead role, the Keku and Akwe simply follow suit, respectively. At the climax of the performance, the Akacha takes over the stage as the dancers improvise on the established motives initiated by the Akwe in a very fast tempo till the end of the music.

The group taxonomy of the dancers expresses the continuity structure of the genre, the line up of the dancers as observed during the opening procession is arranged hieratically, as well as the mono performance of the dancers which is usually introduced by the eldest of the group and passed on to the next in rank till the youngest of the group after which everyone comes back again with their hands joined together to form a united dancing team. The performance technique is demonstrated by high rhythmic patterns as an expression of vigor and life, with the three instruments fusing to form an indivisible part. The melodic summation of the entire performance rallies round six-notes (making a hexatonic scale). The vocal responses were sung in unison in the typical African call-and-response pattern which is aggrandized by the instruments. The improvisation of rhythmic pattern over the passive initial pattern is the major characteristic of Keku Dance.

15. The dance

The Jukun are described as happy people. Virtually all of their musical genres are referred to as dance. As earlier noted, the dance part of the music is a means of playing the third instrument- Akacha (the foot shakers/rattles). Nzewi (Citation2010) notes that dance is an integral part of most religious worships. The dances most times are choreographed. Keku dance is in two dimensions – namely the mono dance and the cooperate dance. The dance is quite dramatic, as it intends to interpret the philosophical values of the community to its audience. The dance vigorously engages the legs, while the arms are held in a manner that enhances the movements of the legs.

16. The text

The text of the Keku dance is informed by the general occurrences of the society. Sometimes popular folklore/songs are imbibed. Ben-Amos (Citation1971) describes folklore as an indigenous phenomenon, because of its central role in sustaining cultural practices. Any form of departure from tales, songs, or sculptures from their indigenous locale, time and society automatically results in substantial change of values. Keku dance employs very brief textual phrase in its performance; yet, the text concisely communicates the general philosophical idea of the event in question.

17. Structural features

Keku dance music primarily engages the heterophonic and monophonic textures. In a situation where more than one fiddle is played, it also employs the polyphonic texture. Monophonic texture is a single melody line, but when played by more than one musician it is referred to as unison while the polyphonic texture is made up of two or more independent melody lines. The heterophonic textures on the other hand, consist of multiple performers playing or singing a single melody all at once, each adding their own subtle variations. This texture best describes the overall performance of Keku dance music.

It is worthy of note that melodic aspect of the music is performed in unison, while the instrument parts engage the heterophoni-polyphonic structure.

18. Training, rehearsal, aesthetics and performance organization of “Keku” dance

Functionally, the genre is entertainment music for major social events of the Jukun. In terms of its instruments and instrument part relationships, there is an exchange of leadership role between the instruments as the music proceeds. At the beginning of the music, the Keku being a melodic instrument takes the leading role by announcing the opening motive of the music, while the other instruments play the accompanying role. Subsequently, as the music proceeds, the Akwe takes over the leadership role by dictating the rhythmic motifs the dancers are to follow while the Keku and the Achacha simply follow suit. At the climax of the performance, the Achacha takes over the stage as the dancers improvise on the established motifs initiated by the Akwe in a very fast tempo till the end of the music. The group taxonomy of the dancers expresses the continuity structure of the genre, the line up of the dancers as observed during the opening procession is arranged hieratically, as well as the mono performance of the dancers which is usually introduced by the eldest in the group and passed on to the next in rank till the youngest of the group after which everyone comes back again with their hands joined together to form a united dancing team. The performance technique is demonstrated by high rhythmic patterns as an expression of vigour and life, with the three instruments fusing to form an indivisible part. The melodic summation of the entire performance rallies round six-notes (making a hexatonic scale). The vocal responses are sung in unison in the typical African call-and-response pattern which is aggrandized by the instruments. The improvisation of rhythmic pattern over the passive initial pattern is the major characteristic of Keku Dance.

19. The stage

Keku dance is traditionally an outdoor performance. Its performance stage is not with special arrangement outside the common African performance arrangement. Onyeji (Citation2002:44) emphasizes the common use of open space, most especially the village squares or any leveled ground wide enough to accommodate uninhibited movement “explosions”. The stage is usually at the center of a rounded audience, with the instrumentalist at the agreed top of the stage, while the dancers take a position directly opposite them. More recently, at political, state and national events, Keku ensemble has performed on contemporary stages.

20. Costume

According to Mr Farii (14 April 2017), initially, there was no specific dress code for performance; people just dress to suit the occasion. But with the advent of civilization, the group has arrived at a uniformed costume, made of the Jukun traditional attire (Adire), with a pair of white tennis for comfort. And the rattles tied around their two legs.

21. Rehearsal

Rehearsals are intrigue to the effective performance of Keku dance ensemble. Building of adequate skills on the instruments and dance are subjected to consistent rehearsals. More intensive rehearsals are usually embarked on to ensure adequate preparation and coordination of forthcoming public presentation (s) or other anticipated events. The group rehearsals often take place at a scheduled venue and time.

22. Discipline

Members of the Keku dance ensemble are expected to be of noble character. Discipline within the group transcends members’ activities within the group. They are considered ambassadors of the community, who are well informed about the cultural values of the people and are as such expected to be a good example to other members of the community. According to Mr Fari (14 April 2017), any member found to be of questionable character are punished and subsequently excommunicated from the group. Absenteeism and disrespect are not condoned by the group. Since the dance and the playing of instruments require special skills, members are expected to be well groomed through consistent training and discipline.

23. Distinctive characteristic element of Keku Dance

In comparison with similar musical instruments and ensembles found in the sub-Saharan Africa such as the Amzadi/Amzad of the Tuareg people, the Gambian Fulbe Nyanyeru, Tanzanian Fiddle – Zeze; Ghana Dagbamba fiddle – Gondze; as well as the “lute found in central Africa, the Zither (Bassa) of Liberia and the Inanga or through zither of Ruanda” which are often accompanied with clapping of hands and accompanied with brass wind instrument with the melodies highly influenced by Islam. The music is without any form of religious interference, often performed in cyclic form. The long multi-movement nature of the work gives it a kind of “song cycle” impression, with an overarching theme and structure connecting them. Also, the repetition of the sections intermittently as an “ostinato” especially in the rhythm section, is combined with the development and variation that result into a new melodic idea; all of which gradually changes and evolves throughout the music. This intense-repetition type of cyclic form is very common in traditional folk music. Unlike similar music types found in the region, it does not engage parallel harmonic styles; rather it performed in unison, sometimes in parallel octaves apart. Also, the performance of the music is similar to the sonata-allegro form because of the concurrent repetition and development of melodic themes displayed within its framework which creates a unified long movement.

24. Transcription and structural analysis of Keku dance music

24.1. Example 1

It is the opening and major theme of the music. It marks the group’s procession into the stage. It is a responsorial chorus between the Keku and the dancers in unison. This section of the music is usually inspired by the presiding event. The melody may vary, depending on the prevailing circumstances of the community. As at the time of the interview, the Wukari community was passing through some turbulent period of ethnic and religious crisis. The people believe that any form of attack on the community is an indirect attack on the king. This is a form of prayer and words of encouragement to the king and the community as a whole; with the text interpreted thus: “this crisis will not last, because the king will always overcome his enemies, all their evil will surely go back to them!”

The opening motif is in four bars repeated several times to encourage the heart of the people. It is common meter 4/4 in the key of C/A natural minor. The percussion parts began with crochet note and semiquaver note on the shakers line and calabash, respectively. While the melody starts with a quaver anacrusis. The melodic statement landed on the submediant “A” (6th) note giving an impression of an incomplete statement in a minor mode. The shakers provided the timeline upon which the other instruments improvised. It was played in a moderately fast tempo, 110. The scale is hexatonic – ABCDEG.

24.2. Example 2

The second example is the development of the opening motif which is the subject of the music, with an increased tempo, 120. The shakers at this point adopted a syncopative rhythm line, while the calabash maintains the initial rhythmic pattern in the first section. The melody appears as a continuation of the subject starting with the opening notes of the subject, i.e. E and G, respectively. The second section is without vocal part; it is purely instrumental. The melody engaged the upper range notes ABCDEG (3). With a constant use of repetition of a descending motif (m:r:d:l-EDCA) and alternating between A and B as a variation of the thematic phrase. The section ended on A, then flows smoothly into the third section.

24.3. Example 3

This section still maintains the upper notes and the rhythmic pattern of the second section in a faster tempo of 125. It also engages the six-notes ABCDEG in the construction of its melody. It seems to be a recapitulation of the preceding sections with major variations on the motif. The abrupt leap between D1 and D2 created a sense of excitement in preparation of the succeeding section. Unlike the preceding sections, this third section ends on D and also flows smoothly into the fourth section without much notice.

24.4. Example 4

The tempo of the fourth section increases to 130. The melody employs the pentatonic scale, consisting CDEGA. It engages the lower notes with a consistent leap between the A1 and A2. Characterized with repetition of motifs, it emphasizes the excitement of the performers and the peak of the music. This section is an introduction of a new idea that is still within the central theme of the music. On the percussion lines, there is a switch of leadership role between the shakers and the calabash. The rhythmic pattern between the two instruments are alternated and harmonized intermittently. The section ends on A and flows into the fifth section.

24.5. Example 5

This section is a recapitulation of the preceding sections similar to the third section. It employs the hexatonic scale-ABCDEG. Still characterized with repeated leap between the first and second ranges of the scale, it maintains the 130 tempo and is elongated by repetitions and variation of the main motif as shown in bars- 4-6 (l:s:m:t:d:l:-m:s:l:–,l:s:m:(s)l:d:l:-m:s:l, etc.). By using G as an auxiliary note for smoother passage between E and A, it also provides the needed variation to satisfy the aesthetics of the music. The activities of the percussion lines in this section are similar to that of the fourth section. This section engages all the ranges in its composition and ended on A which also flows into the last section.

24.6. Example 6

The sixth section serves as the closing section of the music. It employs the pentatonic scale-ACDEG. Still in common meter and maintains a steadier melodic contour without abrupt tonal leaps. This section is characterized with a more consistent repetition of note as its closing signal in a very fast tempo. The calabash and the shakers at this point maintain the same rhythmic pattern in a hurried manner till the end of the music on the last strike of the calabash. The melody ends on A.

24.7. Summary of the analysis of Keku dance

The music is of a mixed ensemble of vocal, dance and instrumental ensemble, with dominance given to the dance and instrumental ensemble.

This piece of music is in cyclic form in six integrated sections.

There are only two categories of three instruments; the chordophone Keku which is the lead solo instrument and the idiophones Akwe (leg shakers) and Akacha (calabash drum). A closer look into the music reveals a heavy interdependence of the idiophones and switch of lead role from the chordophone to the idiophone instruments.

The rhythmic pattern employed is additive and asymmetric rhythmic patterns.

The musical piece is in a simple time 4/4 quadruple meter.

The scale of this music is hexatonic – consisting A B C D E G.

The music begins with a moderately fast tempo and gradually increases speed until it gets to a very fast tempo and thus end.

there is a melodic arm-bit of A3-G5 (using piano pitch measurement method).

C/A minor.

25. Conclusion

This paper documents the distinctive creative elements of the Wukari Jukun keku dance music to support its argument against the homogeneous treatment of African indigenous music at the expense of the many endangered musical cultures of the sub-Saharan Africa. By outlining the outcome of its findings on the creative milieu and musicians in the context of composition, performance and cultural implications of the chosen musical style among others within the study area (Wukari town) through an ethnographic procedure, the authors conducted the structural analysis of the music to exhibit its distinctive characteristic as well as validating the need for continuity, sustainability and wider visibility of the indigenous music to bridge an existing gap in knowledge.

Convincingly, the whole essence of globalization is to facilitate holistic representation of all nations and their identity on the globe and not to reduce its valuable contents. Therefore, increasing the status of Nigeria and Africa as a whole requires diligent search and detailed documentation of our indigenous musical heritage on the verge of extinction via research collaboration and other possible means. There are more characteristic features of African indigenous music that must be discovered. While it is important to add to existing knowledge of the already discovered cultures, the relatively unknown ones too should be paid attention to. Ethno-musicological research forums, institutions and government cultural development agencies should make this a priority, as it promises to directly or inversely increase our contribution to international trade and tourism, as well as a capable means of improving our status as a nation and continent as a whole.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Omotolani Ebenezer Ekpo

Omotolani Ebenezer Ekpo is a graduate of music theory and composition from Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife (OAU) and University of Nigeria Nsukka (UNN) respectively. She is a member of faculty in the Federal University Wukari, Taraba state, Nigeria. She has composed and performed three symphonic and choral works as well as 15 popular songs and the University Anthem for the Federal University Wukari. Her research interest is in research composition, ethnomusicology and ecomusicology; on which she has presented and published articles in local and international conferences and journals.

References

- Aboshi, D. (2010). The heritage: A survey of the history and culture of Jukun-Awanu people of Benue State. Makurdi Oracle Business Limited.

- Adeogun, A. (2006). Music education in Nigeria, 1842 – 2001: Policy and content evaluation, towards anew dispensation [PhD thesis]. University of Pretoria South Africa.

- Agawu, K. (2003). Representing African music: Postcolonial notes, queries, positions. University of California.

- Agbu, A., Shishi, Z., & Useini, B. (2019, March). Jukun-Tiv relations in the benue valley region: The 2019 scuffles in Southern Taraba State, Nigeria. International Journal of African Society, Cultures and Traditions, 8(1), 1–22. Published by ECRTD-UK Print 2056-5771(Print), Online 2056-578X(Online).

- Akpabot, S. (1986). Foundations of Nigerian traditional music. Ibadan: Spectrum Books Limited, 113 pp. Africa, 58(4), 503–504. https://doi.org/10.2307/1160373

- Ampene, K. (2005). Female song Tradition and the Akan of Ghana: The creative process Nnwonkor. Ashgate publishing.

- Arom, S. (2018). Musical system of the sub Saharan Africa. Chapter contribution. Retrieved April 2019, from http://link springer.com

- Ben-Amos, D. (1971). Toward a definition of folklore in context. The Journal of American Folklore, 84(331), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.2307/539729

- Blech, R. (2013). The restructuring of ethnicity in Nigeria. Ethnicity book IN AFRICA.

- Blench, R. (2004). Reconstructing African music history: Methods and results. Printout. http://homepage.ntlworld.com/roger_blench/RBOP.htm

- Boulton, L. (1957). African music: Straus West African expedition of field museum of National History, Chicago. Folkways records and service Corp.

- Collier, D., Laporte, J., & Seawright, J. (2011). Putting typologies to work: Concept- formation, measurement, and analytic rigor. Political Research Quarterly, 65(1), 217-232. DOi:10.1177/1065912912437162

- Dauda, A. (2017). A history of leisure and entertainment among the Jukun people of the lower benue valley of Nigeria [Ph.D Thesis]. School of postgraduate Studies, Benue State University.

- DjeDje, J. (2008). Fiddling in West Africa: Touching the spirit in Fulbe, Hausa, and Dagbamba cultures. Indiana University Press.

- Drezek, K., Olsen, D., & Borrego, M. (2008). Crossing disciplinary borders: A new approach to preparing students for interdisciplinary research. Fronteers in Education conference, 2008. FIE,2008. 38th ASEE/IEEE.

- Edewor, P., Aluko, Y., & Folarin, S. (2014). Managing ethnic and cultural diversity for national integration in Nigeria. Developing country studies www.iiste.org 2224-607X (Paper) 2225-0565 (Online) Vol.4, No.6

- Euba, A. (1989). Essays on music in Africa. Vol. 2. Intercultural perspectives. Elekoto Music Centre. Bayreuth African Studies Series, no. 16. Google Scholar.

- Euba, A. (1990). Yoruba Drumming: The dundun tradition. Eckhard Breitinger, Universita¨t Bayreuth. Lagos: Elekoto Music Centre.Google Scholar.

- Gansemans, J. (1988). Les instruments de musique du Rwanda : étude ethnomusicologique. Leuven University Press.

- Gausa, S. (2013). An adaptive study of jukun cultural symbols for textile design a master of fine arts (MFA) in textiles design thesis submitted to the department of fine and applied arts [Unpublished] (pp. 51–60). University of Nigeria Nsukka.

- Gravers, M. (2007). Exploring ethnic diversity in Burma. - (NIAS studies in Asian topics; 39) ISBN-10: 87-91114-96-9; ISBN-13: 978-87-91114-96-0. NIAS Press UK.

- Herskovits, M. J., & Bascom, W. R. (1975). The problem of stability and change in African culture. In W. R. Bascom & M. J. Herskovits (Eds.), continuity and change in African cultures (pp. 1–14). University of Chicago Press.

- Ladzekpo, C. (1996). Cultural understanding of polyrhythm http://home.comcast.net/~dzinyaladzekpo/PrinciplesFr.html.

- Malcolm, X. (2019). Ancient music of Northern Africa. Ancient Egyptian music. Chapter 1 of African Traditional music. http://.artsite.UCSC,edu

- Mbaegbu, C. (2015). The Effective Power of Music in Africa. Open Journal of Philosophy, 5(3), 176–183. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojpp.2015.53021

- Merriam, A. An annotated bibliography of African and African-derived music since 1936. (1951). Africa, XXI(Oct., 1951), 319–329. CrossRef | Google Scholar. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0001972000062999

- Munyaradzi, G., & Zimidzi, W. (2012). Comparison of Western music and African music. Journal of Creative Education, 3(2), 193-196. DOI: 10.4236/ce.2012.32030

- Mustapha, A. (2006). Ethnic structure, inequality and governance of the public sector in Nigeria. Democracy, Governance and Human Rights Programme Paper, United Nations Research Institute for Social Development.

- Nketia, K. (1986). The music of africa ISBN 0575038470 9780575038479 0575032340 9780575032347. Victor Gollancz publishers.

- Nzewi, O. (2010). The use of performance composition on African music instruments for effective classroom music education in Africa. University of Pretoria South Africa.

- Okunna, E., & Gausa, S. (2014). Adapting the Jukun Traditional Symbols for Textile Design and Production. Mgbakoigba: Journal Of African Studies, 3, 170.

- Omojola, B. (2001). African Musical Resources and African Identity in the New African Art Music” African Art Music in Nigeria. Starling-Horden Publisher (Nig) Lt.d.

- Onyeji, C. (2002). The study of Abigbo choral-dance music and its application in the composition of abigbo for modern symphony orchestra [Ph.D Thesis]. University of Pretoria.

- Onyeji, C. (2016). Composing art music based on African indigenous music paradigms. 102nd Inaugural Lecture, University of Nigeria Nsukka (UNN).

- Riley, D. (2012) ‘Barriers to the access and sharing of scientific data’ The case for international sharing of scientific data: A focus on developing countries. Proceedings of a symposium of the national research council of the national academies. The National Academies Press Washington. D.C.www.Nap.Edu

- Stapleton, C., & May, C. (1989), African All-Stars, Paladin (p. 6). Frontiers in education conference.

- Turino, T. (2000). Nationalists, Cosmopolitans, and Popular Music in Zimbabwe. The University of Chicago Press Books.

- Varley, D. (1936). African Native Music: An annotated Bibliography (London: Royal Empire Society Bibliographies, No. 8. Google Scholar. studies in ethnomusicology series. University of Chicago Press.

- Ward, W. (1927). Music in the gold coast. Gold Coast Review, III( Google Scholar), 214, 203-4-222.

- Welsh, K. (2004). African dance (p. 35). Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0791076415.