?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The paradigm shift orchestrated by evolving New Growth Theory has “endogenized” technical change with its production embedded in the positive neoclassical belvedere. Knowledge no longer assumed as naturally endowed but demands a conscious organization and production by rationally optimizing the behavior of economic agents. The divergence in knowledge in Africa supports the assumption that confirmed the tacit nature of technological knowledge. This suggests that knowledge requires to build competitive economy is inarticulate and may not be easily transmitted at zero marginal cost. To this end, technological knowledge possesses the feature of an ordinary private good and can only be transmitted at a cost via imitation and apprenticeship. This study assesses the role of the knowledge types—basically codified (scientific knowledge) and tacit (technological and entrepreneurial knowledge) on the growth process in Africa for the period 1990–2017. The data used for the empirical investigation were obtained from the World Bank 2018 World Development Indicators and World Governance Indicators. The study adopted the System Generalized Method of Moments in performing empirical investigation. In addition, statistics from World Economic Forum’s Global Competitive Index and World Bank’s Human Capital Index were analyzed. The study found evidence supporting a strong link between technological knowledge (and entrepreneurial) and economic growth while the responsiveness of growth to scientific knowledge infinitesimally approaches zero. The paper recommends a framework that builds competitive knowledge capable of addressing developmental challenges. As domestic sufficiency is attained, trans-border transfers in terms of products and processes will attract wealth.

Keywords:

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The study looked at the relationship between knowledge and economic growth in selected African countries. The study disaggregated knowledge into scientific, technological and entrepreneurial knowledge and uniquely assesses their influence on the growth process. The study covers the period 1990-2017 for fifty-three African countries. The outcome of the study shows that Sub-saharan Africa is the least knowledge competitive region in the world. Also a further evidence reveals a strong link between technological, entrepreneurial knowledge and economic growth while scientific knowledge induces a weak response. This evidence necessitates the need for a framework that enhances the competitive technological and entrepreneurial knowledge capable of addressing African developmental challenges.

1. Introduction

The last two decades have witnessed an upsurge in the empirical study of forces that shape the rate of economic growth. The theoretical front witnessed an unrelenting effort by researchers to produce a variety of models in which sustained growth can occur in the absence of exogenous growth in productivity (Barro, Citation1997; Barro & Salai-i-Martin, Citation1992, 1995, Selkina & Bakanova 2016). Similarly, the empirical front maintained an intense search for variables that correlate with growth performance (Acemoglu, Citation1997; Rodriguez & Martinez 2007; Robelo, Citation1998; De la Fuente & Domenech, Citation2006). In quest of the above, a number of studies in Africa have emphasized knowledge as a crucial determinant of competitiveness and national progress. Undoubtedly, the capacity to innovate—which ascends from knowledge, and bringing innovation successfully to market is crucial for global relevance. Similarly is the recent awareness among policy makers that innovative capacity is the main driver of economic progress and a potential factor in addressing global challenges such as environment and health (OECD, Citation2007; Ogundipe & Ola-David, Citation2015). In the same vein, prominent studies identified that growth would be steadily marginal, if not entirely cease, without the support of knowledge and that in the long-run knowledge would be the only varied determinant of sustainable economic growth (Solow, Citation1957; Lucas, Citation1988, Nguyen & Nguyen 2015; Asongu 2017).

Despite this outlook, a variety of processes that stimulates innovation needs to be discussed. This basically involves understanding the knowledge sources, nature and drivers of innovation and growth to set priority focus for developing Africa economies. Though, the neoclassical and the new growth theory have conceptualized knowledge as an engine of endogenous growth and this led to accounting for technology, learning and innovation as determinants of economic growth. However, a clear transmission of how knowledge drivers culminate into innovation is required to enable developing Africa economies reinvent the structure of institutions and organizations to promote growth and channel investment appropriately. Although, the relevance of knowledge and competitive innovations for economic agents and economies of African states, respectively, have received strong confirmation in literature and needs not to be affirmed using new data and figures (Kefela, Citation2010; Asongu 2018; Oluwatobi et al., Citation2016; Ogundipe et al., Citation2019)

However, the experiences in most African economies and the attention directed towards knowledge creation leaves much concern and one doubt if the policy makers really understand the path to economic competitiveness. The concept of innovation is often misconstrued in most cases as a one-step thing rather than an outcome of a coordinated and coherent (knowledge processes) intervention; it simply implies that growth succeeds a conscious and concerted knowledge accumulation process. Contrary to the some extant studies that treated innovation as stock concept (Oluwatobi et al., Citation2016, Citation2016), succinctly, this re-examination follows an emerging trend in economic theory that classifies knowledge into three main categories: scientific knowledge, technological knowledge and entrepreneurial knowledge (Bacovic & Lipovina-Bozovic, Citation2010). The scientific and technological knowledge are embodied in higher learning institutions or firms while entrepreneurial knowledge is related to market dynamism and the functioning of an economy (Wolff, Citation2013). While extant studies treated innovation in isolation, this study opines that it is either an application of entrepreneurial knowledge or combined result of technological and entrepreneurial knowledge. In our opinion, the answer to growth differential across nations lies on the expansion of scientific and technical knowledge which raises the productivity of labour and other inputs, and form the basis for innovation. This study disaggregates knowledge components to identify the important factor inputs capable of stimulating the rate of growth in African economies.

The extent theoretical and empirical studies reached a common consensus on the fact that human capital development enhances the rate of innovation (Oluwatobi et al., Citation2016, 2018). Knowledge accumulation is at the center of human capital development and the quality of human capital differs across the nations of the world, hence, accounting for the gap in the rate of innovation and economic prosperity. It implies that knowledge acquisition and its application are not constant across nations. It is either some countries are knowledge deficient or knowledge migrated to places commanding high returns. The knowledge deficiency could mean knowledge is never acquired or the necessary infrastructural and institutional capacities to attain competitive knowledge are deficient. Whichever the case is, it implies that knowledge is acquired haphazardly, hence, cannot be applied and not competitive. This limits the ability of the human to innovate and stimulate a widening growth differential among nations.

Available evidence revealed that scientific knowledge which literally denotes the knowledge of methods and procedures of science and captured using scientific and academic journal publications were actually greater than the world average in the period 2005–2015 in Africa; whereas, the growth rate fell from 5.56 to 3.03% in the same period (see in appendix). The scientific and technical articles and the number of patents application have been growing consistently (most times more than the world average) since 1990, whereas, high tech exports have been declining considerably. The growth rate of patent application in North Africa has been more than the world average until 2010, whereas, export of high tech goods has never reached one-sixth of the world average. Though, new business density in Africa has gained marginal increase overtime but among the lowest in the world. This evidence shows that knowledge accumulation in Africa is internally competitive (rather than complementary) and externally non-competitive.

The paper assumes a broader perspective and focusses on the growth performance of African economies as induced by knowledge components. These knowledge components comprise the scientific knowledge, technical and entrepreneurial knowledge. This approach, for the first time in literature, will rigorously access the influence of knowledge categories on the African growth process. In addition, the study adopts a dynamic modeling approach which is adjudged suitable to better handle probing analysis of policy reforms with long-term effects. Specifically, the study employs the System Generalized Method of Moments (SGMM) estimator based on two-step procedure. This approach is necessary to control possible prevalence of unobserved heterogeneity and potential endogeneity of the key explanatory variables; in addition to maintaining a moderate number of instrument vectors.

2. Review of literature

Improving the performance of economies through growth represents part of the objectives of nations; hence, economies all over the world invest in ensuring they continually improve their economic performance. While some have paid attention to investing in factor inputs to facilitate economic growth, some others have gone beyond that to investing in innovation in the form of technological progress. The outcome of these reflects a huge gap between two categories of economies—developing and advanced economies. Studies have proven that advanced economies invest in R&D, innovation and knowledge capital accumulation (Corrado et al., Citation2012; OECD, Citation2007; UNCTAD, Citation2013). This is an indicator that reflects the importance of knowledge accumulation and innovation in the development process, thus, validating the outcome of Solow’s (Citation1957) study that innovation is responsible for 85% of the variations in growth. This path has also enabled economies that used to be considered as less-developed to emerge and catch up with advanced economies. The East-Asian miracle is a testament to the fact that less-developed economies can fast-track their growth and development (World Bank Report, Citation2013; Page, 1994; Stiglitz, Citation1996). Moreover, it shows from empirical literature that knowledge accumulation and innovation have crucial roles to play in facilitating growth and development in an economy. Thus, the more knowledgeable an economy becomes, the more capacity it has for growth.

Knowledge accumulation is therefore an essential process in enabling an economy’s capacity to generate sustainable development. It increases a nation’s innovation capability, which ultimately drives growth as confirmed by the results from the works of proponents of the new growth theory (World Bank Report, Citation2018; Romer, Citation1986, Citation1990, Citation1994; Aghion & Howitt, Citation1997; Fine, Citation2000; Funke & Strulik, Citation2000; Ha & Howitt, Citation2007; De, 2014). These views suggest that developing economies in Africa can also emerge, leapfrog and catch up with advanced economies simply by following the knowledge economy path to growth and development. The situation of Africa is not that Africa does not have knowledge. The conventional idea of comparative advantage had limited Africa’s capacity for growth. That idea posits that countries should focus on areas where they have comparative advantage; thus, African countries had been trading raw materials without adding value through processing. While they export raw products, they import refined products. Based on this ideology, when are Africa countries allowed to start processing and exporting processed products with higher value? This study therefore faults the comparative advantage idea and supports the idea of economic complexity, which promotes the development of various competencies by economies. The process of developing these competencies involves knowledge accumulation, which will ultimately translate into the development of new and refined products, innovation and improved growth.

Various studies have been carried out that supports this idea. Hence, some of these studies have been reviewed in this study to further buttress the argument. Some of these studies emphasized the need to invest in technical and scientific knowledge. It has been proven from extent literature that economies that experience sustainable and upward growth usually are the ones that invest maximally in technical and scientific knowledge and human capital development (Marz et al., Citation2006; Harshberg et al., Citation2007; Tappeiner et al., Citation2008; Oluwaseyi, Citation2012; Miguelez & Moreno, Citation2015; Pelinescu, Citation2015; Kim and Lee, 2015; Kong et al., Citation2017; Minniti & Venturini, Citation2017). It is also evident that investing in the expansion of physical capital capacity is not a guarantee for sustainable long-term growth. The studies of Solow (Citation1957) and Romer (Citation1990) have proven these theoretically and empirically; and their findings acknowledge the importance of knowledge and its accumulation in enabling the rate of growth and development of economies. A few studies have therefore given some attention to find out how to make the process deliberate (Funke & Strulik, Citation2000; Bacovic & Lipovina-Bozovic, Citation2010; De, 2014).

Bacovic and Lipovina-Bozovic (Citation2010), therefore embarked on a study to investigate the importance of investing in knowledge capital for sustainable development in the long term. They did this by examining the trends of investment in education and research as well as estimating the impact of knowledge capacity on employment and GDP per capita. Their findings confirm the significance of accumulating knowledge capital for sustainable economic development. Clearly from their findings, the most advanced economies are the topmost investors in knowledge and its accumulation. They also found out that less advanced economies were investing in skills development and higher education, even though they were not involved directly in knowledge accumulation investment.

While investment in skills development and education is essential for developing economies, it is essential for them to accumulate knowledge through R&D to cultivate the capacity to drive development through knowledge (Eliasson, Citation2001; Nicolaides, Citation2014; Ogundari & Awokuse, Citation2018). Ignoring the importance of going beyond investment in skills development and higher education, limits those in developing economies to users of advanced techologies developed by advanced economies rather than developers (Miah & Omar, Citation2012). However, this study acknowledges that developing economies have to develop the required capacity base for knowledge accumulation through investment in human capital development before embarking on the actual process of knowledge accumulation. Investment in human capital development engenders the capacity to use advanced technologies as well as the capacity for R&D. This leads to innovation and ultimately sustainable economic progress.

Despite the necessity for developing economies, such as those in Africa, to go beyond investment in human capital development to investment in R&D for knowledge accumulation, it is crucial to understand to what extent they can utilize knowledge to create value, opportunities and wealth for their economic progress. Developing economies are already making progress in the area of knowledge creation through research (Oluwatobi et al., Citation2015); however, the level at which the knowledge is harnessed and employed to produce economic value is yet to match up with those of advanced economies. What has distinguished advanced economies is their ability to go beyond knowledge creation to employing it for innovation. The experience of emerging economies coupled with the East Asian Miracle is prooved that developing economies can bridge the gap (World Bank Report, Citation2013; Page, 1994; Stiglitz, Citation1996). Thus, investing in knowledge creation is not sufficient; knowledge needs to be employed to generate innovation, given that it is the factor responsible for the major variations in economic growth and development (Kaur & Singh, Citation2015). This is why it is essential to figure out factors that influence it.

Some of those factors that affect innovation are institutions and openness. Tebaldi (Citation2016) did an exploration of the dynamics of innovation and the factors that affect it. Using the system generalized method of moments (SGMM), he found out that the quality of institutions and openness are crucial determinants that affect innovation growth. This finding clearly shows that economic progress, driven by innovation, is assured with better institutions. It also reveals that the innovation and growth gap between developing and developed economies will keep widening overtime if the quality of institutions in developing economies is not improved. In addition to this, developing economies can catch up with advanced economies if they open up their economies for the transference of knowledge and technology, which also triggers innovation growth.

The studies reviewed to validate the essence of knowledge accumulation and innovation in influencing economic growth and development. They also buttress the fact that African countries can catch up with advanced economies in the development process, if they embrace the knowledge economy path to development. Thus, beyond investment in skills development and human capital development, developing economies, such as those in Africa, can invest in knowledge accumulation, R&D, and innovation. This will enable them to go beyond being users of advanced technologies to becoming creators and developers of advanced technologies. Part of the ideology behind this is the idea that economies, including less-developed economies, can develop and improve on their competencies rather than merely following the idea of doing only what they have comparative advantage in. With this, African economies can accomplish knowledge-driven growth and development.

3. Data and methodology

3.1. Data and variables

In measuring institutions, the study used the WGI definition which includes the following six proxies: control of corruption, governance effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, political stability, and voice and accountability. These proxies addressed the three main institutional framework including political, economic and legal framework. The World Bank’s compilation of institution measures was chosen because they are consistent, best and more suitable for cross-country analysis (Sani, Ismail & Mazlan 2019; Kar and Saha 2012; Ogunniyi et al., 2020; Azuh et al., Citation2019; Ogundipe et al., Citation2019). Although, the WGI institution variables lack sufficient variations, evidence from literature portrayed its reliability, and of course more comprehensive than that provided by the U.S Freedom HouseFootnote1 and Kunčič (2014).Footnote2 The FDI variables used are the net inflows and the data were obtained from United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) country profile database. The data for other variables used in the study were obtained from the World Bank 2017 Development Indicators. The study employs a longitudinal data structure covering 53 African countries over the period 1990 to 2017. The variable choice and period of study are based on data availability and the need to sample over sufficiently large observation. The details of the variables description and measurement are contained in .

Table 2. Data sources and measurements

3.2. Model specification and estimation procedure

The last decades of the twentieth century have witnessed an increasing interest among economists to examine the determinants of long-run economic growth. Similarly, there has been a considerable increase in both theoretical and empirical economic literature pointing out the importance of knowledge in economic growth. Economic growth or development remains a central objective in the economic agenda of decision makers in developing economies. In an attempt to achieve these objectives, different political and economic scenarios have been induced by different models of growth. This results into the emergence of chain of growth theories depicting various sources of economic growth. Pioneer models by Harrod (Citation1939) and Domar (Citation1946) emphasized accumulation of capital as major sources of growth. The model was revisited and revised by Solow (Citation1957) who augmented the model with the inclusion of technological process, which represents another production factor. The Solow model viewed technological progress as exogenous to the economy, the externality of this factor breeds ambiguity, as explaining the source of technological progress generates intense controversies. A paradigm shift was initiated by Arrow, Romer and Lucas resulting in the emergence of the endogenous growth model which emphasizes the inducement of technical progress through the process of learning, investment in research and capital accumulation.

The learning-by-doing theory espoused by Arrow (Citation1962) revealed the prominent role of knowledge creation and knowledge spillover for offsetting diminishing returns to capital. He emphasized that increasing stock of knowledge enhances efficiency in the production processes over time. Similarly, the perfect competitive model advanced by Romer (Citation1986) included knowledge as a factor of production in addition to labour and capital. Romer emphasized that knowledge exhibits increasing returns and also generates externalities. As illustrated by Kaur and Singh (2016), the Romer’s model suggests that production of knowledge by one firm also benefits the others with that knowledge. In the spirit of the endogenous model, Lucas (Citation1988) in his model framework addressed the ambiguity regarding the source of growth. He developed an endogenous model in which growth is stimulated by the rise in human capital. According to Lucas, in addition to physical capital, human capital achieved through schooling and on the job training is the significant factor leading to economic growth.

The study takes lead in disintegrating knowledge into three categories including scientific, technological and entrepreneurship knowledge and equally assesses the weight and contribution of these knowledge categories to growth process in African economies.

The theoretical model follows the spirit of Solow (Citation1957), Romer (Citation1990), and Mankiw et al. (Citation1992). This was further espoused by Oluwatobi et al. (Citation2015), which signifies that human capital, innovations and ICT infrastructure are critical in stimulating growth processes. This study takes a leap from others, as it addresses the type of knowledge that better propel growth for developing economies. To examine the relationship between identified knowledge types (scientific, technological and entrepreneur) and economic growth in Africa, the following model is specified:

Where captures the growth rate of the economy,

refers to the available capital stock,

is labour force,

is a vector of knowledge categories and

comprises other important determinants of the growth model such as the strength of financial intermediation and foreign knowledge spillovers. It follows that

and

.

The explicit form of Equationequation 11

1 in a panel structure can be presented as follows:

In order to estimate the model within the framework of classical regression model, a logarithmic transformation is required. Invoking a double log operation on Equationequation 22

2 , the dynamic form of the model becomes:

Where ,

,

connotes the entities (African countries) and

is the time identifier. The model addressed knowledge as a critical stimulant of economic growth; especially by addressing the knowledge components that are more important for economic growth.

Where is as previously defined in Equationequation 1

1

1 ,

is a vector of the control variables.

The study further examines how some structural composition of an economy can stimulate or mitigate the contribution of these knowledge components on economic growth. The indicators of knowledge components; scientific knowledge (scientific & technical journal articles, and school enrollment), technological knowledge (export of high tech good, and ICT goods export) and entrepreneurial knowledge (new business density) were lagged to one period to account for knowledge process which is perceived as dynamic. These indicators capturing dynamism in knowledge process is then interacted with structural components such as strength of financial intermediation, ICT infrastructures, foreign knowledge spillover and institutions. In this regard, we considered knowledge as flow concept and assessed its impact on the growth process in the region (See Equationequation 4)4

4 .

The study employs a dynamic estimation approach to assess the influence of knowledge components on economic growth in Africa. The dynamic nature of growth and the need to adequately address potential endogeneity bias necessitates the use of dynamic panel model framework. The need for this framework is also based on the fact that policy reforms arising from the dynamic functioning of the economic process tends to exhibit long-term effects, considerably far beyond the immediate term. Based on this, attention has drifted from the use of static model, especially for studies conducting cross-country analysis (Ogunniyi et al., 2020; Azuh et al., Citation2019; Headey, Citation2013). The GMM dynamic framework allows to model growth as a function of past (initial growth) and the current explanatory variables. The dynamic model is specified as:

Where denotes GDP growth rate, it is the per cent increase in annual GDP which reflects the productiveness of an economy (Ogundipe et al., Citation2019).

represents the GDP growth rates lagged one year or the initial value of GDP.

is a column vector of the indicators of knowledge categories. This includes scientific, technological and entrepreneur knowledge (Brooks 1994).

represents the control variables included in the model that are determinants of output growth in the African economies.

is the composite of the institutional strength indictor measured as the first principal component of indicators of WGI governance indicators, including government effectiveness, rule of law, control of corruption, political stability, regulatory quality, and voice and accountability (See Ogundipe, Oye,Ogundipe et al., Citation2019).

is the unobserved country-specific effects. It captures the effect of heterogeneous factors that are time invariant such as geographical and cultural factors.

denotes the time-specific effect which accounts for shocks that do not vary among countries such as global demand shock (Ogunniyi et al., 2020). Finally,

is the random error term,

are the estimated parameters. The subscripts

and

denote the country and time periods, respectively.

The combination of the lagged dependent variable and the time invariant unobserved entity differences () pose estimation challenges to Equationequation 4

4

4 . If the unobserved heterogeneity is not accounted for, it can bias the predictors (serial correlation). Also, due to the dynamic nature of the model and possible correlation between

and

; the OLS estimation will be biased upward (Bond 2002; Ogunniyi et al., 2020). One would think that given the first problem, the use of fixed effect model would be appropriate but given the second problem the estimation would still produce a bias result. This position was also emphasized by Nickell (Citation1981) because the lagged of the dependent

is still correlated with

. Two possible solutions exit in handling the estimation problems; first is the first differencing of the data in order to purge the time invariant term and the unobserved differences across entities (Anderson & Hsiao, Citation1982; Arellano & Bond, Citation1991; Holtz-Eakin et al., Citation1988). The second is the use of forward orthogonal deviations (Arellano & Bover, Citation1995). The study employs the first difference procedure, a preliminary check reveals no meaningful difference in results obtained when the forward orthogonal deviation was attempted. The same evidence was documented by Ogunniyi et al., (2020).

By incorporating the first differencing, Equationequation 44

4 becomes:

The instruments address the correlation problem and

in equation 5. The instrument comprises the previous observations of the lagged dependent variable and same procedure is applied to account for the potential endogeneity of other explanatory variables. If we assume the explanatory variables are weakly exogenous and the

serially uncorrelated, the lagged levels of the explanatory variables can be used as instruments in the specification (Ogunniyi et al., 2020; Dejong & Ripoli 2006). When the first difference is used with the level of past values as instruments, it results in the known Difference-Generalized method of moments (DGMM) estimator (Arellano & Bond, Citation1991). Though, the DGMM is superior to static panel data estimator, a known deficiency is that lagged levels appear to be weak instruments for first differences, if the series is very persistent (Bond, Jaeger & Baker, 1995). Also, long-run information associated with the relationship between the dependent variable and explanatory variables can be lost. In the same manner, Baltagi (2008) opines that due to the prevalence of weak instruments, the asymptotic and small-sample performance of DGMM estimator could be adversely affected; hence resulting in inefficient and biased coefficient estimate.

Furthermore, the shortcoming of the DGMM can be addressed and its efficiency enhanced by adding the original equation in levels to the system (this is referred to as the system-GMM estimator). In the light of this, the study employs the two-step system-GMM estimator incorporating the Windmeijer’s (Citation2005) finite sample correlation for standard errors. The study adopted an optimal weighting matrix, following Roodman (Citation2009) such that highly correlated instruments get less weight in the estimation process. In ascertaining whether the lagged values of the explanatory variables are valid instruments, the study used the Arellano and Bond (Citation1991) AR(1) and AR(2), and Hansen (1982) J-test for examining the serial correlation properties and over-identifying restrictions, respectively.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics of variables in the model

shows the summary statistics of the variables in the model to be estimated. The Table indicates the mean, minimum, maximum, standard deviation and measures of normality for the variables. The mean value of the growth rate of GDP is about 4.1, a minimum of −62.08 and a maximum of 149.97. The wide difference between the mean and maximum shows that some African economies at some time experienced a huge growth (about 150%) and the minimum value of −62% reflects that certain economies retrogressed significantly. The standard deviation of about 8% also buttressed the instances of significant deviation from the average growth path in the region. In the same manner, the strength of the financial system also differs significantly among economies in the region as reflected by the standard deviation of 19.4. The mean, minimum and maximum values are 19.2, 0.15 and 160.1, respectively, reflecting significant diversity in the strength of financial system in the region, largely due to the varying market sizes of the economies. Similarly, the series capturing FDI inflows as share of GDP reflects a similar trend, with a mean of 3.3%, a minimum of −82.9% and a maximum value of 161.8%. The statistics show that on the average FDI inflows into Africa is small; while some resource-rich economies have attracted significant inflow, the performance has been dismal in others. Other factors that could have impeded FDI inflow into some countries are tensions and political unrest, this singular factor has been a deterrent to investment inflow into Africa.

Table 3. Summary statistics of variables

Considering the knowledge variables, entrepreneur knowledge differs widely in the region with a mean of 23,905, a minimum of 14 and maximum of 376,727 new business registrations. Generally, the recent decade has seen a rapid increase in the number of new businesses and start-ups to jumpstart the economies and ensure inclusive growth in the region. In the same vein, technological knowledge is advancing, the number of scientific journal publications have been growing steadily in Africa with growth rate faster than other regions of the world. The scientific knowledge has a mean, minimum and maximum values of 565 and 11, 991 published journals and a standard deviation of 1601 articles. The technological knowledge captured with “ICT goods export as a share of GDP” has mean of 0.8%, a maximum of 20.9% and a standard deviation of 1.9%. The disparity between the mean and maximum reflects the gap in technological adoption in African economies. Finally, on the average, mobile phone subscriber and secured internet servers usage in the Africa are 15 persons and 501 persons per 1,000 users, respectively.

The symmetric distribution of the series were obtained using the skewness, kurtosis and the Jarque-bera statistics. The evidence (See ) shows that the series is not normally distributed. This was corroborated by the rejection of the null hypothesis (stating that the assumption of normal distribution was not violated) via the significance of the probability of the Jarque-bera statistics at 5% significance level.

4.2. Multicollinearity test

The pairwise correlation in shows no significant correlation between the knowledge components and growth rates. Where the correlation becomes significant (for new business density), it is negatively correlated with growth rates. The scientific and academic journal articles (Scientific knowledge) is positively and significantly correlated with number of patents application, trademarks and new business density but negatively and not significantly correlated with high-tech exports. This implies that the knowledge generated in the economy could not invent internationally competitive products, hence accounts for the development gap across the nations of the world; which is predominantly widen for African economies. The foregoing implies that the knowledge components in African economies are theoretically skewed and technologically deficient. Hence, there is need for investment in globally competitive knowledge. The overall assessment of shows no serious problem of multicollinearity in the model, hence, the parameter estimates are suitable for drawing inferences.

Table 4. Pairwise correlation analysis

4.3. System GMM results

The analysis was preceded with a quiet estimation of the static panel analysis, however, due to the obvious shortcoming of the static analysis in handling endogeneity problems, the result seems not empirically reasonable. According to Arellano and Bond (Citation1991), Arellano and Bover (Citation1995); and Blundell and Bond (1998), the GMM is a suitable estimation strategy for handling exogeneity biases. Having satisfied that some of the explanatory variables are not strictly exogenous and that the dynamic panel bias does not exist—the cross sectional dimension (N) is greater than the time dimension (T); the system GMM results for the models are specified in . Table 1 comprises the effect of the knowledge components on growth while the effect of each of the knowledge components on growth rate following interaction with structural economic variables.

Table 5. Effect of knowledge on Growth

Table 6. Scientific knowledge—Scientific journals (interacted with structural variables) and growth

Table 7. Scientific knowledge—Tertiary education⁺⁺ (interacted with structural variables) and growth

Table 8. Technological knowledge—High tech exports⁺ (interacted with structural variables) and growth

Table 9. Technological knowledge—ICT goods exports⁺ (interacted with structural variables) and growth

Table 10. Entrepreneurial knowledge—New density business interactions⁺ (interacted with structural variables)

Table A Human capital index

The study adopted the two-step procedure and a corrected cluster robust errors based on Windmeijer (2003). The estimation procedure involves different specification of the models with collapsed instruments matrices (See Roodman, Citation2009) until an empirically reasonable result was attained. The estimation process treated FDI, knowledge components variables and investment as endogenous while other explanatory variables are treated as strictly exogenous.

4.4. Descriptive analysis

The study assesses the reliability of the empirical analyses using an independent statistics in examining the evidences obtained. The global competitive report published by the World Economic Forum (WEF) in 2018 was adopted. This enables us to assess relevant statistics on the drivers of productivity in the African economies. The report provides statistics and rank world economies based on competitiveness—which comprises twelve distinct blocks including: institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic, health and primary education, higher education and training, goods market efficiency, labour market efficiency, financial market development, technological readiness, market size, business sophistication and innovation.

4.5. Discussion of result

Following the two-step SGMM estimation based on Roodman’s specification, the parameters in the model were checked for autocorrelation. This was conducted using the Arrelano-bond tests, the AR(1) and AR(2) tests show that the empirical results presented in to 10 are void of autocorrelation. Also, the instrument vector was moderate and considered valid using the Sargan and the Hansen J test. The F-test confirms the joint significance of the explanatory variables in explaining the observed variation in the growth of African economies. The satisfactory outcome of the post estimation diagnosis strengthen the outcome of the empirical analysis and hence validates the usefulness of the parameters for drawing inferences and making policy decisions.

The result in shows that scientific and academic journal article (scientific knowledge) does not stimulate growth positively in Africa. The knowledge advanced in most theoretical research outcome ends on paper in Africa, whereas, most material inputs used in acquiring scientific knowledge and publication outlets are sourced across the border and financed locally. In the same manner, the quest for higher education institutions to attain global relevance, better still, the seal for global acceptability has mitigated the desire to address local/domestic problems with research outputs. Most research outputs from the region are written and composed to appeal to global audience or the preferred audience of the foreign-based high ranking journals. In addition, the education process in terms of its content and structure is deficient towards national development, it was inherited by the colonial master and a number of African economies have failed in developing a transformational education structure capable of addressing domestic development challenges but has consistently hock to the colonial structure. The evidence is consistent with that of Bloom et al. (Citation2006) and Seetanah and Teeroovengadum (Citation2019) which posited that impact of tertiary education is limited in sub-Saharan Africa when compared with other regions. The evidence reflects the inadequate understanding of the resulting positive externalities of higher education on economic development.

On the other hand, the exports of high tech goods (technological knowledge) pose a positive and significant influence on growth rates. This knowledge component is very crucial in expanding the growth potentials of African economies as it leads to advancing inventions and innovations that commands high returns in the global market. In the same manner, new business density is important in stimulating the growth process in the region. This constitutes the development of SMEs and start-ups that serves as the engine of economic growth. This foregoing portrays that Africa policy makers and government need to rethink the present knowledge framework as it regards to learning curriculum in Schools and on-the-job training to ensure that curriculum and vocations are designed to address cogent economic problem and ensure the process of knowledge accumulation is adequately financed to ensure that globally competitive knowledge capable of generating inventions are acquired at all levels of schooling and training. A similar evidence was attained by Asougu & Tchamyou (2016) which suggested that an enabling business environment can significantly boost the transmission to knowledge economy and growth outcomes. In this regard, knowledge environment in terms of commitment by the government and policy makers in stimulating the technological and entrepreneurial knowledge via sufficient financing will boost economic growth.

The empirical analysis proceeds by examining the role of structural capabilities in influencing the impact of scientific knowledge on the growth process in Africa. The structural economic capabilities to be considered include: institutional capability, foreign knowledge spill-over capability, financial intermediation capability and infrastructural capability. The capabilities are simply interacted with a one period lag value of the different knowledge category to capture the role this structural capabilities play in knowledge creation and how this in returns impact the growth process of African economies. The results for the scientific knowledge and structural capability interactions are contained in . The results indicate that scientific knowledge has negligible effect on growth, even after interaction with the structural economic capabilities. It implies that, even after controlling for role of institutions, foreign knowledge spill-over, financial intermediation and infrastructure; the indicator of scientific knowledge exert a minimal impact on growth. The scientific knowledge though has been on the increase in the region but this knowledge category does not in itself drive the growth processes meaningfully. The empirical evidence corroborates the fact shown by the data in Table A1 (see appendix), which suggests a rising profile of scientific and academic journal articles with relatively declining growth rate for the period observed.

The outcome corroborates the post-world war II assertion by Friedman suggesting no evidence that higher education produces any benefit beyond the sense of schooling itself. However, against this backdrop, emerging evidence (World Bank 2004; Hoenack 1993; Seetanah & Teeroovengadum, Citation2019) asserts that higher education could meaningfully drive growth process in SSA if investment is adequately channelled coupled with more research in unearthing the role of higher education in addressing the critical domestic developmental needs and challenges. In the same vein, Bloom et al., Citation2006) attributed the launching of India’s economy into the world stage as resulting from its decades-long successful efforts to provide high-quality, technically oriented tertiary education to a wide range of the citizens.

More so, in order to further assess the role of the structural capabilities on other categories of knowledge, show the interaction of the structural capabilities with one period lag of technological knowledge. A one period lag of technological knowledge is used to ensure that we obtain the appropriate influence of the structural economic capabilities on the technological knowledge and growth linkage. Here, the emphasis is to derive how the structural capabilities stimulate the actualization process of technological knowledge. Unlike the scientific knowledge, the technological knowledge is significant and growth inducing both at its level and after interaction with structural economic capabilities (with the exception of institutional capabilities). The interaction with institutional capability could not yield a meaningful response on growth process for the region. This would not be unconnected with the weak institutional capacity in enforcing rule of law, executing a sound transformational framework and implement a people centered and benevolent disbursement of state resources for development of human capital. It is necessary to note that the foreign knowledge spill-over and the infrastructure capability interaction with the technological knowledge acquisition strengthen the growth process. More specifically, controlling for these categories of capabilities enhances the growth-inducing potential of technological knowledge. The evidences portray the reality in Africa, in the sense that foreign direct investment helps in transferring knowledge across borders, hence enhancing local assimilation and reproduction. Likewise, infrastructural development is crucial in acquiring relevant and competitive knowledge. Provision of adequate infrastructure creates avenue for conducive knowledge transfer, it stimulates the mind of the leaner and encourages to lean-by-doing. The fast-growing emerging economies of the 20th century with increasing exports of technological products have had to imitate and gradually reproduce technology. This evidence corroborates the result obtained using ICT goods exports as a measure of technological knowledge. In the same version, foreign knowledge spill-over and infrastructural capabilities strengthen the progressive link between technological knowledge and growth in the region.

In furtherance, illustrates the role of structural capabilities in influencing the entrepreneurship knowledge and growth nexus. The entrepreneurship knowledge significantly stimulate growth, as it’s capable of yielding an approximately a proportionate returns on growth to a unit rise in entrepreneurship knowledge. In ascertaining the role of structural capabilities, the study interacted these capabilities with a one period lag of entrepreneurial knowledge in an attempt to account for the role of the structural economic capabilities in the effective acquisition of the knowledge category. The infrastructural capability, specifically, mobile telecommunication service, was more important in stimulating the entrepreneurship process and growth. Also, the foreign knowledge spill-over enhances the growth-inducing capacity of entrepreneurship knowledge.

4.6. Discussion of descriptive evidence

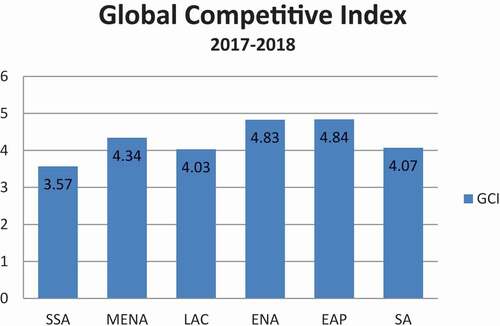

Knowledge and innovation are virtues embodied in humans; then competitiveness makes a compelling argument that human capital is important to growth in an increasingly knowledge-driven global economy. It implies that a highly competitive economy will possess a workforce with high spectra of knowledge that are competitive in the global space. Figure A1 (see in appendix) shows the level of competitiveness across regions of the world, the index is based on 12 distinct basic requirements.

The index as shown in shows the competitiveness of the regions, the chart was constructed using the region’s average. Based on the pillars, the sub-Saharan Africa is the least competitive region in the world; the average score for the countries in the region is 3.57 out of possible 7. This report indicates that of the 32 SSA countries captured, 14 countries scored below average, being the region with the largest number of less competitive economies. The East Asia & pacific, and Europe & North America top the competitive table with average score of 4.84 and 4.83, respectively. Ironically, the scientific knowledge in SSA (scientific and academic journal articles) exceeds the world’s average for the period considered. This again suggests that the knowledge embodied in an average African is not yielding inventions that are competitive in the global market place. The evidence supports the emerging call for SSA economies to transform learning and embrace ICT to reap its growth potentials (Tasamba, 2019). This also reflects in the nature and composition of Africa’s trade with the world, which is highly concentrated with exports of income and supply inelastic primary commodities, and imports of skilled intermediate and manufactured good. The former, due to its weak value addition commands low and unstable prices in the global market place while the latter due to its value-addition and knowledge-based contents does not suffer from scarcity, exhibits a weak diminishing returns and attracts high prices in the global market. The evidence also supports the assertion by Prebisch (1950), Singer (1950) and Ogundipe et al. (Citation2019). To ascend on the track of competitiveness, there is need to channel investment into the development of technological productivity by conscious investment in the expansion of technological knowledge.

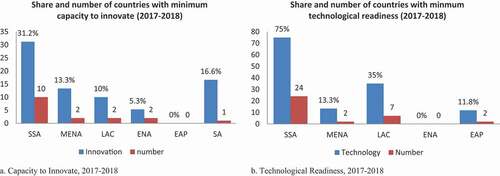

Consequently, important statistics on some of the basic pillars in the world competitive report reveals the reason for the widen gap in African competitiveness relative to other regions of the world. (see appendix) shows the capacity to innovate across regions; the SSA region has the highest number of countries with less capacity to innovate. Specifically, 10 out of the 32 SSA countries scored below average in innovative capacity representing 31.2%, compared with other regions like middle east and north Africa, Latin America and Caribbean, Europe and north America, east Asia and pacific and South Asia with 2, 2, 2, 0 and 1 countries with minimum potential to innovate. In the same manner, (see appendix) shows the index of technological readiness as a measure of competitiveness with SSA countries being the least technologically ready region. The figure depicts that 75% of SSA economies are less technological ready suggesting that 24 out of the 32 economies observed scored below average for the index; the least technological ready country in the world “Chad Republic” also featured in this group. Whereas, only 13.3% (2 countries), 35% (7 countries), 11.8% (2 countries) scored less than average in Middle and East Asia, Latin America and Caribbean, and East Asia and Pacific, respectively. All countries in Europe and North America are technologically ready with the least score of 4.1 out of possible 7 corresponding to Albania almost at per with the SSA maximum.

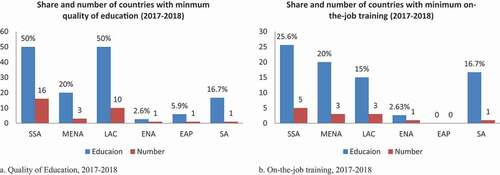

The study also considers the indexes on the quality of education and on-the-job training as measures of competitiveness (see , ). Similar to the foregoing, the SSA region underperformed relative to other regions of the world. The statistics show that half of the SSA economies currently among the countries with the least quality of education in the world. In the same manner, on the average, the region performed worst in the quality of on-the-job training with about 30% of the economies in the category of the world's worst economies in this regard. These emerging evidenceshow that the region is deficient in the upstream and downstream knowledge acquisition process, hence, this accounts for the lean global competitiveness.

5. Conclusion and policy recommendation

The recent thought espoused by emerging theories on the knowledge of growth has identified knowledge as crucial for growth, competitiveness and employment. It is then suggests that global shifts in the production and flows of knowledge lead to an associated global shift in wealth. The depleting nature of human and natural resources signifies that growth will progressively depend on knowledge-based productivity because knowledge-based capital is free of scarcity and diminishing returns. To this end, it becomes paramount to channel investment and structure development efforts to the improvement and expansion of human ingenuity by conscious investment in competitive knowledge creation. This will in turn help economies enhance their competitive advantage, increase the value-added spectra and heighten relevance in the global market place.

In an attempt to assess the knowledge category that drive African’s growth process, the study examines the effect of knowledge on growth rates in Africa by assessing the specific role of scientific knowledge, technological knowledge and entrepreneurial knowledge. Surprisingly, African’s stock of scientific knowledge has grown steadily in the observed period, even above the world’s average while the case is reverse for technological and entrepreneurial knowledge. Specifically, not only is the African’s technological knowledge growth the weakest in the world but also exhibits a retarding growth, being about one-fifth, one-seventh, one-sixth and one-fifth of the world’s average in 1995, 2000, 2010 and 2015, respectively. The empirical model adopted the Solow (Citation1957) framework and estimated the model using the system generalized method of moments (GMM) which is necessitated to overcome possible problem of endogeneity inherited in the specified model. The readily available results show that the scientific knowledge retards the growth process in Africa, whereas, technological and entrepreneurial knowledge contributes meaningfully to growth expansion. It implies that scientific knowledge is essential foundation knowledge—can be alternatively called primary knowledge, it requires to be filtered and proceed into tangible and rent attracting competitive products and inventions to attract reward in the global market space, hence stimulating growth.

Moreover, the study analyzed the role of institutional, infrastructural, foreign knowledge spill-over and financial intermediation on the knowledge—growth nexus in Africa. We discovered that the structural capabilities tend to influence the technological knowledge—growth nexus and entrepreneurial knowledge—growth nexus than the scientific knowledge—growth relationship. The study achieved this by obtaining a one-period lag of knowledge and interacted with structural capabilities to appropriately derive the role of the structural capabilities in the knowledge generation processes. Consequently, a robustness check was conducted using statistics from Global Competitive Index of World Economic Forum and the Human Capital Index of the World Bank. The two primary measures of global competitiveness by WEF are innovation and business sophistication. African economies occupy the lowest rung in these indexes, as the region has the highest number of countries with the least capacity to innovate and about 75% of the SSA countries are not technologically ready. Also the HCI corroborates the existing evidence as no SSA countries featured in the first 100 countries, out of the 157 countries captured. All the SSA countries were lined from 113rd position downward. Specifically, the last 50 positions comprise entirety of African economies. The policy decision makers in Africa need to channel development effort towards enhancing competitiveness by a conscious value addition to primary knowledge. As a matter of urgency, the government should incorporate into their development agenda a drive towards building knowledge-based capital in learning and skill development infrastructures needed in acquiring a developmental oriented and competitive knowledge—whose awareness is prevalent in driving growth in today’s global market place.

There is need for an overhaul in the knowledge acquisition processes in SSA economies. The government and education authorities need to reassess their commitment towards provision and improving the quality of higher education and on-the-job training. Presently, a number of countries in the region can hardly boast of quality higher education of learning, and where is barely existed, the masses are been priced out. This suggests adequate provision, periodic assessment and evaluation of the framework to ensure that adequate knowledge and needed skill-set being developed are capable of addressing development challenges. A simple framework is to build capacity to develop systems and products that address local challenges, as the processes continue; domestic sufficiency stimulates trans-border transfers and hence, attracts wealth.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Adeyemi A. Ogundipe

Adeyemi A. Ogundipe holds a PhD in Economics, with specific focus on Resource and Environmental Economics. He currently lectures and conducts research at Covenant University in the Department of Economics and Development Studies, Nigeria. He is also a Research Fellow at the Covenant University Centre for Economic Policy and Development Research (CEPDeR)

Oluwa Tomisin M. Ogundipe

Oluwa Tomisin M. Ogundipe lectures in the Department of Economics and Development Studies, Covenant University, Nigeria. Her research interests are cost and benefit analysis, health care quality improvements and health outcomes.

Notes

1. The institution measures are available @ https://freedomhouse.org/reports.

2. Kunčič (Citation2014) recommended a composite indicator which combines the information of several empirical measures.

References

- Acemoglu, D. (1997). Why do new technologies complement skills? Directed technical change and wage inequality, Working Paper , Cambridge, MA: MIT

- Aghion, P., & Howitt, P. (1997). A schumpeterian perspective on growth and competition. In D. M. Kreps & K. F. Wallis (Eds.), Advances in economics and econometrics: Theory and applications, 2 (pp. 279–34). Cambridge University Press.

- Anderson, T. W., & Hsiao, C. Formulation and estimation of dynamic models using panel data. (1982). Journal of Econometrics, 18(1), 47–82. (1982). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(82)90095-1

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. (1991). The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297. 1991. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2297968

- Arellano, M., & Bover, O. Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. (1995). Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 29–51. (1995). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)01642-D

- Arrow, K. (1962). The economic implications of learning by doing. Review of Economic Studies, 29(3), 155–173. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2295952

- Azuh, D., Ogundipe, A. A., & Ogundipe, O. (2019). Determinants of women access to healthcare services in sub-saharan Africa. Open Public Health Journal, 12(1), 504–514. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2174/1874944501912010504

- Bacovic, M., & Lipovina-Bozovic, M. (2010). Knowledge accumulation and economic growth. faculty of Economics ( pp. 37–50). University of Montenegro and ASECU.

- Barro, R. (1997). Determinants of economic growth: A cross country empirical study. MIT Press.

- Barro, R., & Salai-i-Martin, X. (1992). Convergence. Journal of Political Economy, 100(2), 223–251. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/261816

- Barro, R., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (1994). Economic growth. McGraw-MillR.

- Bloom, D., Canning, D., & Chan, K. (2006). Higher Education and Economic Development in Africa. The World Bank. Available @ https://www.edu-links.org/sites/default/files/media/file/BloomAndCanning.pdf

- Corrado, C., Haskel, J., Jona-Lasinio, C., & Lammi, M. (2012). Intangible capital and growth in advanced economics: measurement methods and Comparative Results. IZA Discussion papers, no. 6733

- De la Fuente, A., & Domenech. (2006). Human capital in growth regressions: how much difference does data quality make? Journal of the European Economic Association, 4(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/jeea.2006.4.1.1

- DeJong, D. N., & Ripoll, M. Tariffs and growth: An empirical exploration of contingent relationships. (2006). The Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(4), 625–640. (2006). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.88.4.625

- Domar, E. D. (1946). Capital Expansion. Rate of Growth and Employment, 14(2), 137–147.

- Eliasson, G. (2001). The role of knowledge in economic growth. Royal Institute of Technology (RTH). , available @ www.oecd.org/innovation

- Eliasson, G. (2001). Industrial policy, competence blocs and the role of science in economic development.. In D. C. Mueller & U. Cantner (Eds.), Capitalism and Democracy in the 21st Century. Physica.

- Fine, P. E. M. (2000). Gaps in our knowledge about transmission of vaccine-derived polioviruses : Round table discussion/Paul E. M. Fine. Bulletin of the World Health Organization : The International Journal of Public Health2000r, 78(3), 358–359. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/57264

- Funke, M., & Strulik, H. (2000). On Endogenous growth with physical capital, human capital and product variety. European Economic Review, 44(3), 491–515. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(98)00072-5

- Ha, J., & Howitt, P. (2007, June). Accounting for trends in productivity and R&D: A schumpeterian critique of semi-endogenous growth theory. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Blackwell Publishing, 39(4), 733–774. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-4616.2007.00046.x

- Ha, J., & Howwit, P. (2007). Accounting for trends in productivity and R&D. A schumpeterian critique of semi-endogenous growth theory. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 39(4), 733–774. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-4616.2007.00045.x

- Harrod, R. F. (1939). An essay in dynamic theory. The Economic Journal, 49(193), 14–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2225181

- Harshberg, E., Nabeshima, K., & Yusuf, S. (2007). Opening the ivory tower for business: University-industry linkages and the development of knowledge-intensive clusters in Asia Cities. World Development, 35(6), 931–940. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.05.006

- Headey, D. Developmental drivers of nutritional change: A cross-country analysis. (2013). World Development, 42(2), 76–88. (2013). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.07.002

- Holtz-Eakin, D., Newey, W., & Rosen, H. E. (1988). 1988. Estimating Vector Autoregressions with Panel Data. Econometrica, 56(6), 1371–1395.

- Kaur, M., & Singh, L. (2015). Knowledge in economic growth of developing economies. discussion papers in development economics and innovation studies, centre for development economics and innovation studies (CDEIS), Discussion paper no. 12

- Kefela, G. T. (2010). Knowledge-Based economy and society has become a vital commodity to countries. International Journal of Educational Research and Technology, 1(2), 68–75.

- Kim, S., & Lee, H. (2006). The Impact of organizational context and information technology on employee knowledge-sharing capabilities. Public Administration Review, 66(3), 370–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00595.x

- Kong, D., Zhou, Y., Liu, Y., & Xue, L. (2017). Using the data mining method to assess the innovation gap: A case of Industrial Robotics in a catching-up country. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Elsevier, 199(c), 08–97.

- Kunčič, A. Institutional quality dataset. (2014). J. Institut. Econ., 10(1), 135–161. (2014). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137413000192

- Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(88)90168-7

- Mankiw, N. G., Romer, D., & Weil, D. W. (1992). A contribution to the emprics of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(2), 407–437. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2118477

- Marz, S., Friedrich-Nishio, M., & Grupp, H. (2006). Knowledge transfer in an innovative simulation model. In. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 73(2), 138–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2005.05.002

- Miah, M., & Omar, A. (2012). Technology advancement in developing countries during digital age. International Journal of Science and Applied Information Technology, 1(1), 30–38.

- Miguelez, E., & Moreno, R. (2015). Knowledge flows and the absorptive capacity of regions. Research Policy, 44(4), 833–848. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2015.01.016

- Miguélez, E., & Moreno, R. (2015). Knowledge flows and the absorptive capacity of regions. Research Policy, 44 (4), 833–848. , Elsevierr

- Minniti, A., & Venturini, F. (2017). R&D policy, productivity growth and distance to frontier. Economics Letters, Elsevier, 156(C), 92–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2017.04.005

- Nickell, S. Biases in dynamic models with fixed effect. (1981). Econometrica, 49(6), 1417–1426. 1981. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1911408

- Nicolaides, A. (2014). Research and Innovation. The drivers of economic development. African journal of hospitality. Tourism and Leisure, 3(2), 1–16.

- OECD 2007. Annual report on sustainable development work in the OECD, available @ www.oecd.org/greengrowth/40015309

- Ogundari, K., & Awokuse, T. (2018). Human Capital Contribution to Economic Growth in Sub- Saharan Africa. Does Health Status Matter More than Education? Economic Analysis and Policy, 58, 131–140.

- Ogundipe, A., & Ola-David, O. (2015). Foreign aid, institutions and economic development in West Africa: Implications for Post-2015 Development. Nigerian Journal of Economic and Social Studies, 57(2), 15–34.

- Ogundipe, A. A., Adu, O., Ogundipe, O. M., & Asaleye, A. J. (2019). Macroeconomic Impact of agriculticural commodity price volatility in Nigeria. Open Agricultural Journal, 13(1), 162–174. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2174/1874331501913010162

- Oluwaseyi, A. A. (2012). Human Capital Investment and economic growth in Nigeria: A longrun path. Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences, 9(4), 188–194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3923/pjssci.2012.188.194

- Oluwatobi, S., Efobi, U., Olurinola, I., & Alege, P. (2015). Innovation in Africa: Why Institutions Matter. South African Journal of Economics, 83(3), 390–410. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/saje.12071

- Oluwatobi, S., Ola-David, O., Olurinola, I., Alege, P., & Ogundipe, A. (2016). Human Capital, institutions and innovation in Sub-saharan Africa. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 6(4), 1507–1514.

- Pelinescu, E. (2015). The impact of human capital on economic growth. Procedia Economics and Finance, 22, 184–190. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00258-0

- Robelo, S. (1998). The role of knowledge and Capital in economic growth, available @ www.kellogg.northwestern-edu/faculty/robelo/htm/finland.pdt

- Romer, P. M. (1986). Increasing Review and long-run Growth. The Journal of Political Economy, 94,(5), 1002–1037. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/261420

- Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. The Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), 571. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/261725

- Romer, P. M. (1994). The origins of endogenous growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.8.1.3

- Roodman, D. How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. (2009). Stata Journal, 9(1), 86–136. (2009r). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0900900106

- Seetanah, B., & Teeroovengadum, V. (2019). Does higher education matter in African economic growth? Evidence from a PVAR approach. Policy Reviews in Higher Education, 3(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23322969.2019.1610977

- Solow, R. M. (1957). Technical Change and the Aggregate production function. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 39(3), 312–320. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1926047

- Stiglitz, J. E. (1996). Some Lessons from the East Asian Miracle. The World Bank Research Observer, 11(2), 151–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/11.2.151

- Tappeiner, G., Hauser, C., & Walde, J. (2008). Research Policy, 37(5), 861–874. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2007.07.013

- Tebaldi, E. (2016). The Dynamics of total factor productivity and Institutions. Journal of Economic Development, Chung-Ang University, Department of Economics, 41(4), 1–25.

- UNCTAD, 2013. United Nations Conference on trade and development Report 2013, available @ unctad.ord/en/publicationslibrary.

- Windmeijer, F. A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step GMM estimators. (2005). Journal of Econometrics, 126(1), 25–51. 2005. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2004.02.005

- Wolff, J. G. (2013). The SP theory of intelligence: An overview. Information, 4(3), 283–341. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/info4030283

- World Bank. (2003, December). ICT and MDGs: A World Bank Group Perspective.

- World Bank Report, 2013. Accessed @ http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/468831468340807129/World-development-report-1993-investing-in-health 03/04/2020

- World Bank Report, 2018, Think Africa Partnership: A Knowledge Platform for Economic Transformation and Growth in Africa. Available @ https://www.worldbank.org

Appendix

Table A0. Growth of knowledge category across regions