Abstract

As a cultural phenomenon, the Buginese who settled in Malaysia perceived the Bugis identity differently. In Malaysia, the Buginese were considered unique, since they had strong social linkage to the country and the region but remained proud of their narrative of origins. Utilising a multidisciplinary approach by combining the study of history and culture, this article explores the development of the identity of the Malaysian Buginese through the establishment of various communities on social media. Data was gathered from interviews with Malaysian Buginese respondents, as well as from analyses of social media accounts, such as Facebook, which the Malaysian Buginese were using as an interaction platform. In this way, we illuminated cultural identity as a sociocultural construction. Communities and social media were used as the channel of networking that linked the Buginese’s present existence with the past. Our work shows that, over time, the Bugis identity became less essential, in the sense that it could be seen as an ever-transforming identity influenced by growing history, culture, and authority.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Diaspora could be considered as a factor that changes how human perceive and embrace multiculturalism. It is a cultural phenomenon that allows a group of people to have strong social linkage to the country they settled in, as well as to remain proud of the connection they have with their land of origin. Such expression could be seen on the social media – today’s platform on displaying many kinds of social interaction. In Facebook, as an example, we could see how groups were made to accommodate various interest and activities, including the Bugis diaspora in Malaysia (Johor and Selangor) who use Facebook Groups as a channel of networking that linked their past and present existence. This research examines how cultural assimilation transformed them and allowed them to redefine their identity through collective memories.

1. Introduction

This research explored the construction of the Bugis identity in Malaysia, as it is expressed on various social media platforms. The main focus of this research is to understand the articulation process Malay-Bugis community members used to represent and further explore their identity through Facebook, an online social media and social networking service known for decades in Southeast Asia alone. We identified several posts representing group members’ understanding of the relationships between their Bugis identity and their whole identity. These posts included daily status updates and photo and video uploads, as well as Bugis-related insignia used in profile photos. On the one hand, these posts could be considered a mere expression of excitement; on the other, they could manifest cultural pride and attachment.

That the articulation process must be elaborated from the point of view of the Malay-Bugis Malaysians became clear when the Bugis identity entered the political spotlight in 2017. According to BBC News, Dr. Mahathir Mohammad, then a candidate for Malaysian Prime Minister, referred to the Malay-Bugis people as descendants of lanun (pirates) in his campaign speech on 3 November 2017. This comment evoked various responses. Most Malay-Bugis Malaysians expressed shock that a prominent Malaysian politician could deliver such a tone-deaf and resentful speech. Malay-Bugis communities established several groups on Facebook in an effort to counter the accusation with posts showcasing their identity, cultural linkage, and historical background. They utilised the social media platform to reveal aspects of their cultural identity that people might not have known about a diaspora community in their country. For example, they highlighted stories of the Buginese arrival to the Malay Peninsula, which required constructing networks among many Malay ethnic groups during a treacherous sea voyage. According to Buginese Facebook posts, the Buginese people’s courage throughout this journey made them acknowledged as accomplished seamen instead of pirates. At the individual and group level, these Facebook accounts thus redefined the identity of the Buginese, combatting the negative stereotype ascribed to them recently.

In this article, we positioned identity in a sociocultural frame or construction, where it is reconstructed for a reason that is somehow related to evolving interest. This positioning is important because without representation and acculturation processes, no such identities might exist. Furthermore, such movements in cyberspace give apparent opportunity to these communities to retrace their past—to walk down memory lane—and develop a stronger personal identity in a multicultural society. By promoting the importance of tradition and language, these movements are perhaps also a strategy to increase cultural fervour.

In assessing the reality constructed in the platform, we argued that these communities on Facebook could be seen as a pioneering agency of the establishment of a global village, supported by major enhancements in technology and communication sectors in the shape of new media. Fikri (Citation2018, p. 38) elaborated the Internet’s deep role in conflicting and conjoining identities at the present time. Facebook groups are becoming a convenient “hall of fame” for the Malay-Bugis people to recollect their past, as well as establish a collective memory.

Even beyond these explorations, studies about Malaysian identity have always been fruitful. Malaysia is a country with a multicultural society consisting of various ethnic groups. One of the ethnic groups was the Buginese, who were introduced to the loyalty oath of the Malay world in the 18th century but ceased to mention it further since the “pemelayuan” practice (to generalise Malay speaking groups as Malay) acculturated the Buginese in the Malay configuration. However, awareness of being “half-Buginese” rose—among those residing in Malaysia and elsewhere—after the statement of Dr. M mentioned earlier (Tirto.id, 10 November 2017).

Recognising this increasing awareness, this research delved deeper into the process of identity-making among Malay-Bugis people to understand how they perceived and expressed themselves through the wide use of social media. We focused on the way the Malay-Bugis people produced several notions related to their Bugis identity, which were quite apparent in the postings and messages that appeared on their Facebook pages.

Indeed, the Malay-Bugis identity can be seen as both an individual and communal construct. Efforts to construct their autochthonous identity were influenced by fluctuating political tensions and social, cultural, and economic shifts. Zhao et al. (Citation2008) elaborated two aspects related to the construction of identity. While the first—the process of identity announcement—is generated by individuals or a group of people, the second—identity placement—is given. These two aspects of identity are contentious and difficult to separate, making it likewise difficult to determine whether identity is generated internally or merely assigned by others.

When exploring the Malay-Bugis community, it was also interesting to observe their efforts to preserve their narrative of origins and ancestral beliefs and practices, as well as indigenous tradition of the Buginese in South Sulawesi. These efforts involved the establishment of cultural institutions, museums, and community accounts on social media. The combination of cultural and historical studies was fundamental to answering the question of why the Bugis identity articulated in modern day Malaysia and how that identity became a contested proposition recently.

In an effort to reconstruct their past identity, the Malay-Bugis people established a community account to gather various family groups sharing a similar ethnic identity. They chose Facebook as the medium of networking because the platform offered extensive and profound opportunities to reach a larger audience of stakeholders in their articulation process. According to Hall (Citation1996, pp. 141–142), at least two major functions of the articulation process operated. They were:

‘ … the process of rendering a collective identity, position, or set of interests explicit and the process of conjoining (articulating) that position to definite political subjects.’

Within such a definition, articulation was considered a linkage, conjoining binary options, differences, and even contradictory elements. Under certain circumstances, the link between the two need not always be absolute and essential. Meanwhile, the act of conjoining to establish unity and togetherness of a discourse was exactly the articulation of many different elements, which could be re-articulated through different procedures to eventually actualise the sense of belonging among the people of the same descent. Hence, we concluded that the theory of articulation was one of the ways we could understand the ideological element’s contribution to the process, blend into the discourse, and then ask how they did or did not articulate at certain conjunctions for certain politics.

This research posed at least three questions to the respondents: First, how did the Malay-Bugis people see themselves in relation to their past and present identity or position? Second, how did the Malay-Bugis people preserve their vernacular identity? And third, why would such vernacular identity be maintained for such a long time and even passed on through generations?

2. Method

This research used the method of history with qualitative approach, based on the previous study on the diaspora of the Buginese to the peninsular area of Southeast Asia. The method of history allows this article to delve deeper into the cultural relationship between the Buginese and the Malay people in Johor and Selangor, as they were once a part of a singular cultural core.

In the process of gathering the data, we collected case studies from Facebook, especially Facebook accounts with explicit reference to the Bugis or Malay-Bugis community. We interacted with fellow members of the Bugis-Malay community in Johor and Selangor through a questionnaire, gathered from at least 42 respondents. We also held two focus group discussions with fellow historians and anthropologists who had conducted similar studies or who held similar interests in the sociocultural life aspects of the Buginese in general, such as Dr. Mukhlis PaEni, Dr. Abdul Malik from Raja Haji Fisabilillah University in Tanjung Pinang, Dr. Azhar Ibrahim from the Malay Studies of National University of Singapore, R.A. Huzaifah bin Dato’ R.H. Hashim from Persatuan Melayu Bugis Serumpun (Malay-Bugis Cluster Association), Alwi bin Daud from University of Malaya, Prof. Dr. Asmiyati Amat from Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Mohammad Romazi Nordin from Kesenian Citra Ugik (Citra Ugik Art Space), and Dr. Hj. Al Azharri Siddiq Kamunri from Putrajaya, Malaysia. They provided us much information for our background research. We then analysed sources using the descriptive analysis method, which is suitable not just for portraying and analysing the situation in a specific period of time but also for describing the overall development of a group of people in a broader temporal context. Thus, this method enabled a closer look at the changes that happened over time and the ways those changes happened.

Studies of social media have become very common and powerful as the information given can vary from the most basic information to a complex corpus of lexical parallelism. Daniel Miller’s Tales from Facebook (2011) and Social Media in an English Village (2016), as well as Yuyun Surya’s “The Black of Indonesia”: The Articulation of Papuan Ethnic Identity on Social Media (2017) were three examples of how social media could act as a medium of identity construction and social branding. Facebook was the most preferable platform for most people to articulate themselves in an open, generic, and flexible manner. Although numerous studies exist to show the role of social media in modern-day society, none have specifically explored the diaspora story of the Buginese in Malaysia.

3. The early stage of the buginese arrival at the Malay Peninsula

The existence of the Buginese in the Malay Peninsula (Malaysia) has deep historical roots. Political factors appear to be the most prominent issue introduced in various narratives, but social, economic, and cultural factors also contributed to further diaspora to the area, later known as modern-day Malaysia. The first wave of migration, which began at the end of the 17th century, was caused by the war between Makassar and Dutch colonists from 1660–1669. In such a lengthy period of conflict, many Buginese from South Sulawesi choose to evacuate to new settlements in Nusantara and East Asia. They sailed across the sea with their own ships, explored shores and coastal areas, and established connections with the locals before finally establishing more permanent settlements (Ammarell, Citation2000, p. 492).

As a migrating community, which was sometimes also referred to as a community in refuge, the Buginese were known for their strong work ethic. They were hard-working and adaptive men and women who had entrepreneurial skills that opened economic opportunities in underdeveloped areas. They managed to cultivate new agricultural areas, develop a small-scale fishing industry, and introduce a marketplace for daily transactions and trading. Their contribution to the Malay community was indeed a fruitful one, and it made them fairly well-accepted migrants, refugees, or foreigners, depending on how we perceive their displacement into the Malay world (Ammarell, Citation2000; Li, Citation2000; Pelras, Citation2006).

The second wave of the Buginese migration occurred in the 18th century, marked by the emergence of a number of small Buginese kingdoms scattered around the coastal areas in the peninsula, which had been known as the destination of Bugis migration. Beyond those kingdoms, the Buginese had actually created a diaspora network to various places outside of South Sulawesi since the 18th century. The area called “Kampung/Kampong Bugis” could be found in every settlement in the peninsula and archipelago area.

In his book Manusia Bugis, Christian Pelras identified the Buginese as a sojourning community that acquired such diasporic activity as their second nature, permanently embedded into their identity as it was also acknowledged publicly. Nevertheless, their journey was not without a cause. Pelras elaborated several reasons the Buginese chose to wander. These included efforts to resolve conflicts, to avoid public humiliation, to express outrage, to seek safety in unsafe situations, or merely to leave the sociocultural constraints or coercions imposed by the local community in their place of origin (Pelras, Citation2006, pp. 370–371).

Yet, the most significant and noteworthy motivation for Buginese migration to various areas outside of South Sulawesi arose from their growing economic needs. Pelras highlighted this factor, finding that the migrating Buginese who left South Sulawesi were experienced entrepreneurs who could do more than open agricultural areas with traditional farming systems. In addition to agricultural pursuits, they had a strong orientation toward economic development (Pelras, Citation2006, p. 376).

The third wave of Buginese migration occurred after the establishment of the modern concept of the nation-state in Southeast Asia. It was a product of the decolonisation process of the region after World War II. During this period, most countries in the region gained independence and began constructing their own configurations and geographical boundaries. Indonesia gained independence in 1945, followed by Malaysia in 1957. These developments thus separated the two by modern political construction. The term Malay-Bugis was then introduced to distinguish a Malay-born Bugis from the indigenous Buginese of South Sulawesi, even though both shared similar—or, in truth, essentially the same—sociocultural values and practices.

From these three different phases, a consistency in the purposive values of the migrating community becomes apparent. First, the Buginese will always be remembered as the most successful sojourning community in Nusantaran history (Pelras, Citation2006). Malleke dapureng, the traditional conduct of living the Buginese have held since their earliest migration, referred to their basic knowledge about moving in and out of a community. Malleke means “taking away”, while dapureng means “cooking furnace”, and therefore malleke dapureng referred to the situation in which a Buginese individual took his or her cooking furnace out of the house before a long journey. It signifies that the Buginese were not coming back to live and eat inside the house because they had decided to migrate to another area. Installing a cooking chamber or kitchen in another place, in turn, means that they had established a new connection to a new place.

Second, the Buginese are also known for their adaptive nature (Saripaini & Yusriadi, Citation2016, p. 171). This was a philosophy of life of the Buginese, known as mallabu sengareng, or “the boat rests where the memory lays anchor” (Paeni, Citation2020). Therefore, they could conveniently “install” themselves into a new community in the destined area. Moreover, in general, the Buginese in Malaysia could assimilate further by becoming a part of the Malay society, living according to Malay conduct and standards to the point where they actually instituted an alternative existence for the Buginese in Malaysia with minimum authentic characteristics applied (Yusriadi, Citation2015; Saripaini & Yusriadi, Citation2016).

This matter could be associated further with the context of social adaptation. Barth (Citation1982) explained that in order to keep up with challenges and threats, every community would choose to adapt so as to survive and thrive, even if doing so forced them to abandon their indigenous identity. Thus, adaptation processes determine the development of every community, including ethnic groups like the Buginese.

4. And identity construction of the buginese in technology malaysia

Rapid shifts of technology go hand-in-hand with the development of a society and its surrounding culture. In this process, norms, values, meanings, faith, beliefs, habits, and mentalities are constantly reconfigured (Piliang, Citation2014, p. 77). However, we must understand that the relation between technology and culture was never passive nor unidirectional but mutual. Culture affects technology, while technology can directly alter culture. According to Piliang, culture is a space where ideas, imaginations, and fantasies are created, and an imagined community is very likely to be one of the outcomes, with technology as the enabler of any imagination.

Through the lens of technological determinism, we can identify technological advancement as a natural driving force of a cultural subsystem shift (Kaplan in Piliang, Citation2014, p. 78). The altering landscape of technology and information also carries a shift in the way people communicate and retain information. The Internet was perhaps the key of this otherwise unimaginable shift. With the Internet, everything moved faster, processed in a more seamless way than ever before. Then came social media, which helped humanity developed mutual connections and became an extension of the human experience. McLuhan argued that social media was the auxiliary part installed to the five basic senses. It maximised our ability to retain the multitude of information given or scattered around us, even during menial daily activities (McLuhan, Citation1982 in Fikri, Citation2018, p. 2).

In the era of disruption, the media has grown bigger and bulkier. McQuail (Citation2010) classified its development across three main forms: printed media, electronic media, and new media, each with its own typologies. Each media has its own market and target, but all of them were working under the same notion, which was to deliver messages to anyone at any time under many circumstances. This shared goal left the media prone to conflicts of interest.

This article highlights the linkage between technological advancement and Malay-Bugis efforts to preserve a collective memory and retrace their diaspora identity to the past. Through media, especially the new media, information travels more quickly and efficiently than before, and this speed and efficiency triggers seamless identity reconstruction among its users. Social media, as a part of the new media, also has a growing audience (Fikri, Citation2018, p. 10). Sudibjo stated that the new media could be considered the key of an additional development: the birth of new public spaces offering a more open, egalitarian, and liberating space for many (Sudibjo, Citation2019, p. 9). Such character is urgently needed to bring balance to the on-going evolution of any society.

The construction of cultural identity by the Malay-Bugis on Facebook brought a clear depiction of the ways in which technology enabled the creation of a new space for various people or communities to articulate their identity, while questioning, attaching, or detaching themselves to the collective memory between the Malay-Bugis people. The Internet held the primary role in shaping their collective identity and reproducing their diaspora identity at the same time. This diaspora identity could only be achieved through a process of production and reproduction and a series of transformations and alterations over time. Therefore, diaspora identity is something of a hybrid. In this context, Hall (1990) described:

‘The diaspora experience as I intended here is defined, not by essence or purity, but by the recognition of a necessary heterogeneity and diversity; by a conception of “identity” which lives with and though, not despite, difference; by hybridity. Diaspora identities are those which are constantly producing and reproducing themselves anew, through transformation and difference.’

At last, such a phenomenon proceeds in a linear way with the transformation of media, which, since its early arrival, made it possible for people to extend their reach and transcend geographical circumstances or limitations (Masco in Fikri, Citation2018, p. 29).

5. The identity of Malay-Bugis individuals on social media

Identity is an essential part of human nature, attached to individuals by default to set them aside from others. It includes both physical and nonphysical characteristics. Gusnelly et al. (Citation2014) explained identity as the distinguishing features of an individual or group that generate a differentiated perception toward themselves and others. This perception helped us to understand differences and make unique traits, markings, or attributes.

Kietzmann et al. (2011) also agreed to this premise by mentioning identity as the predominant aspect that an individual or a group of people might seek to portray in their social media accounts. In his view, activity on social media platforms represented an individual’s identity, focus, and goals, along with his or her commonality with a group of people if he or she also belonged to a community account.

Eisenlauer (Citation2013, p. 18) argued that social media could actually be more than merely a communication system or an entertainment application because it offered the function of representing and managing the identity of an individual or a whole community to create and display a public profile. In this way, we could say that social media has the ability to install one’s identity inside the perception of others. In this article, we found it necessary to explore the use of social media—Facebook in particular—as the medium of Malay-Bugis efforts to install their own identity: liberated but not segregated.

“Liberated but not segregated” was a phrase established by the Malay-Bugis people in Malaysia to characterise themselves in the contemporary context. They considered themselves to be different, since they had not had a chance to meet their great ancestors or visit South Sulawesi, for instance. Phinney (in Xu, 2014) described ethnic identity as a characteristic formalised by the interpretation of an individual toward the community or settlement to which he or she belonged, so perhaps this is the principle of the re-assembly process of the Malay-Bugis identity.

Zhao et al. (Citation2008) emphasised the meaning of identity construction as a set of processes, consisting of the announcement of individual identity made on purpose whenever an individual tried to justify or claim their existence, and the positioning of identity made by others to hold the individual justification or claim together. Nevertheless, the most important aspect of the construction of a whole ethnic identity depends on an individual’s interpretation toward him or herself, predisposed by certain milieu and social constructions imposed by others.

As we came to understand this perspective, we focused on how the Malay-Bugis utilised Facebook as the medium of announcing and positioning the kind of identity they wanted others to acknowledge and as an output of the later predisposition of surrounding circumstances. The process of identity construction among the Malay-Bugis people in Malaysia could be analysed further by examining posts and threads.

As a product of the new media, Facebook offered simplicity and convenience to individuals or groups seeking to articulate their thoughts and notions. McLuhan (Citation2001) explained that it also changed the way people communicate one to another, discover new information, and see the world, since the medium is the message. In Journalism and New Media, Pavlik (Citation2001) elaborated the five dimensions of contextual journalism: wide communication model, hypermedia, high audience engagement, dynamic content, and customisation (Pavlik, Citation2004, p. 4 in Fikri, Citation2018, p. 118). These dimensions provide the foundation to examine Facebook as the platform of choice for the Malay-Bugis communities in articulating their identity.

6. Facebook: The medium of modern-day articulation

Social media is a command-based platform providing digitisation, convergence, interactivity, and development of networks to generate and deliver messages (Watie, Citation2011, p. 70). The new platform has much to offer, including ever-developing features and an open space for its users to discover and take control of any information on the World Wide Web. The ability to transform regular social activity to a more interactive state is the promise of the new media (Flew in Watie, Citation2011, p. 70).

The announcement of the Malay-Bugis identity in Malaysia on Facebook began the initiatives of a certain group of people who sought to encourage Malay-Bugis individuals to revive the Bugis language by interacting with each other using their native language in the Facebook group. The announcement helped them identify themselves and the purpose of the group. The group also allowed individuals to practice the Bugis language and dialects, while showcasing other cultural elements, such as the traditional costume, traditional practices and beliefs, laws and customs, and special dishes and cooking practices. In these ways, they established and branded themselves as a diaspora community, while introducing the context of their identity, which distinguished them from the Buginese of South Sulawesi.

The announcement of identity through Facebook had the same important notion as an ordinary identity announcement. Analysing the posts shared, we discovered significant background on the origins of their diaspora identity and came to understand the political, social, and cultural preferences encapsulating the process. Our efforts highlighted four community accounts on Facebook, which we studied further to uncover the characteristics and nature of their interaction. Some intended to utilise the account as a forum to exchange ideas and knowledge about the Malay-Bugis narrative of origin, while others exhibited a more personalised intention, which was to lay a base for political supports or movements and construct and articulate identity. This article analysed four main accounts:

7. Persatuan persepaduan rumpun bugis melayu Malaysia (PRBM/ Malaysian Malay-Bugis association)

Persatuan Persepaduan Rumpun Bugis Melayu Malaysia (PRBM), or the Malaysian Malay-Bugis Association, is the name of the Facebook account of one Malay-Bugis community in Malaysia. The account was created in 2011 with the purpose of raising public awareness toward the existence of the Malay-Bugis ethnic group in Malaysia, as well as contributing to the development of the nation in many different aspects.

Based on our observation toward the posts, PRBM has shared posts regarding economic, social, cultural, and even political issues in Malaysia, which reveals the identity construction the group sought to achieve. In an effort to acquire the Buginese identity as accomplished sailors or seamen in the Southeast Asian maritime world, the account displays a profile picture (), showing a sailing ship, along with two badik handles (the traditional weapon of the Buginese in South Sulawesi) and two hands holding a flagstaff with the Malaysian national flag. Thus, the construction was meant to articulate their identities as the descendants of the Buginese who were once a group of skillful sailors who travelled across the region but remained proud of being Malaysians at the same time.

Figure 1. The badge of PRBM (PRBM’s facebook account, accessed from https://www.facebook.com/pages/category/Artist/Persatuan-Perpaduan-Rumpun-Bugis-Melayu-Malaysia-PRBM-244076175628288/).

Based on other PRBM Facebook activity, which included uploaded pictures and shared comments, we classified two types of posts: politically influenced posts and regular posts. Regular posts simply contained materials supporting the group’s aim to increase cultural knowledge among members of the community. These included suggestions for preserving traditions and practices in the contemporary world. As an example, one post encouraged members to learn how to read and write in the Bugis language. Gradually, these efforts aimed to increase members’ familiarity with and pride in the language, enabling them to share it with others.

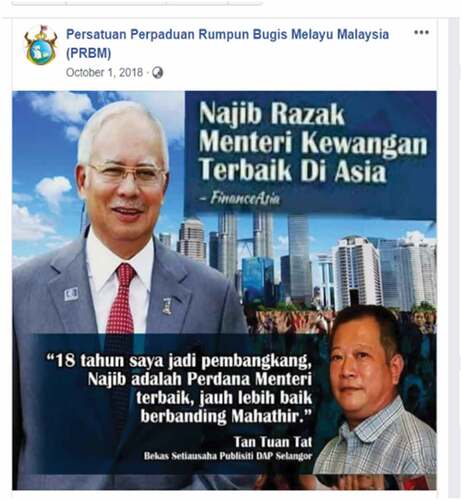

Politically influenced posts, in contrast, presented members’ political affiliations openly to the group and posted informative yet provocative issues on the forum. The objective of these posts was to gather public opinion about the political situation in the country. At the same time, the posts aimed to shape the Malay-Bugis people’s consciousness of the growing circumstances by specifically rooting for the coalition under Barisan Nasional (BN), which consists of United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA), Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC), and Parti Bersatu Rakyat Sabah (PBRS). This coalition, which recently supported Najib Razak, the Malaysian Prime Minister from 2009–2018, represented the longest serving government in Malaysia.

Some posts, like below, were dedicated to supporting Barisan Nasional and Najib Razak as the incumbent in the 2017 election.

Figure 2. PRBM’s post supporting Najib Razak from Selangor, contrasting the achievements of the incumbent with rival candidates, Mahathir Mohammad (PRBM’s Facebook Account, accessed from https://www.facebook.com/pages/category/Artist/Persatuan-Perpaduan-Rumpun-Bugis-Melayu-Malaysia-PRBM-244076175628288/).

Still, the PRBM account proved most interesting in its efforts to maintain a focus on articulating and preserving the partial identity of the whole Bugis ethnic group, including contemporary memories of the Malay-Bugis people in Malaysia, who joined the forum as community members.

8. Wija bugis selangor (bugis-selangor noblesse)

Wija Bugis Selangor, or the Bugis-Selangor Noblesse, is another Malay-Bugis Facebook group in Malaysia. This group was established in 2017, when a member shared its first post. According to the group description, its purpose is to preserve Bugis culture in Selangor.

The groups’ members kept its focus simple by sharing and updating information on the history of the Bugis diaspora to Malaysia, as well as the cultural aspect of the Buginese as they assimilated with common practices in Malay culture. After analysing the groups’ posts, we concluded that the Malay-Bugis people in Malaysia sought linkages and networks with the indigenous Buginese in South Sulawesi because they believed these connections would help them uncover their narratives of origins and better understand their past. At the same time, they managed to maintain their loyalty to the country as they admitted to understanding the reality constructed by a modern sociopolitical configuration.

In correlation with Hall’s elaboration (1996), identity can preserve past memories, but it is the social, political, economic, and cultural realities that shape it further, causing development, changes, and even re-constructing of the identity. Therefore, we assumed that being a part of the Buginese or Bugis ethnic group was considered a past identity, while becoming a part of the Malay-Bugis community was considered the currently enduring identity. In this conception, the identity was perceived as separated but not completely disconnected.

Similar to the regular posts found in the PRBM Facebook account, the regular posts in this account also announced and positioned the currently enduring identity publicly, with a specific emphasis on the Malay-Bugis of Selangor. below was among our discoveries on Wija Bugis Selangor’s Facebook account.

Figure 3. Wija Bugis Selangor’s posts (accessed from https://www.facebook.com/wijaogiselangor/).

[Trans.] The Bugis diaspora from Sabah, originated from South Sulawesi in Klang, Selangor. The Bugis diaspora from Sabah, originated from South Sulawesi is the most recent diaspora occurred in Selangor. As if their ancestors called them, they arrived in Klang and became a reminiscence of their ancestors’ arrival between 1669 and the 1800s. However, various groups from South Sulawesi dominated this recent diaspora, adding colours to Klang, especially in Andalas and Bukit Tinggi.

These posts appear to represent the Malay-Bugis people’s peculiar pride toward their ancestral features, as they admitted that the Buginese were the “founding fathers” of the Malay world configuration, especially at Johor and Selangor, where their legacy remained even after centuries had passed.

9. Perkumpulan bugis selangor (bugis-selangor association)

Perkumpulan Bugis Selangor (), or the Bugis-Selangor Association, is a Facebook community account created in 2012. This group was utilised further to create connections between Malay-Bugis children and strengthen their sense of belonging as descendants of the same ancestor. A significant characteristic of this group appeared in the “Ungkapan Toriolo” threads, which used proverbs and sayings to introduce prominent Malay-Bugis values to the young generation. The thread was posted by an account named Princess Bugis on 23 June 2012, explaining ungkapan toriolo as the teaching of moral values and life skills, including honesty and integrity, public health, cleanliness, respect and honour, ethics and manners, obedience, anger management, and the art of living in a communal space. These values were transmitted through an accessible and dynamic platform by using the progressive approach of social media.

Figure 4. Perkumpulan Bugis Selangor’s Facebook Account (accessed from https://www.facebook.com/groups/241274762615935/about).

10. Perkumpulan anak bugis johor (johor-bugis youth association)

Perkumpulan Anak Bugis Johor, or Johor-Bugis Youth Association, is a Facebook group established in 2013. It encourages Malay-Bugis children in Johor to preserve and be proud of their identity. We also analysed the way this group branded itself through the badge uploaded as its profile picture (). Similar to PRBM’s efforts, this group articulated its identity through the symbol of maritime glory of a Muslim community from South Sulawesi.

Figure 5. The Badge of Anak Bugis Johor on 12 March 2019 (accessed from https://id-id.facebook.com/AnakBugisJohor0123/).

Analysing this badge and its interpretation and re-articulation among the young generation reveals certain meanings:

The core value and character of the Buginese as individuals with a downright, agile, yet dauntless personality.

An ancestral belief toward the ancestors as accomplished seamen (orang laut) with strong entrepreneurial skills and a key role in establishing the Malay sultanates.

The black, pirate’s flag-like badge showcasing the Buginese as a mighty people whose power terrified pirates (lanun).

The anchor emphasising the prowess of the Buginese in the ancient Southeast Asian maritime world.

These meanings were adopted as the main principle of the group, highlighting the young generation’s pride toward their Buginese ancestors in South Sulawesi, Indonesia, in spite of the fact that they were Malaysian citizens.

11. Diaspora identity construction: The bugis-malay

The existence of the Malay-Bugis community in Malaysia proves the arrival of the Buginese in the Malay World. The diaspora process encouraged the introduction of two identities, a cultural identity and a diaspora identity. According to Hall (Citation1990), the construction of cultural identity can be described further by two definitions available, an essential definition and a positioning definition. Essentially, cultural identity is perceived as one shared culture, a sort of collective one true self, which can be understood as a constant identity, referring to the unchanged past actuality. Positioning allows cultural identity to become a matter of becoming as well as being, meaning that the identity is linked to a historical root but adjacent to transformation and alteration caused by the constantly shifting course of history, culture, and authority (Hall, Citation1996, pp. 223–225).

Alternatively, when viewed through the constructionist approach, which used identity as mere positioning, cultural identity is constructed through memory, narratives, and myths. In a larger context, the cultural identity of the Malay-Bugis is also related to these points, as integrating factors, especially in the way they seek to cope with the highly multicultural society in Malaysia. Barker explained that identity is constructed through symbols, stories, imaginations, and rituals that encourage the sense of belonging and the understanding of mutual or shared cultural affiliation (Barker, Citation2000, p. 198). Barker based this notion on Anderson’s idea of the nation as an imagined community, which is significantly different from any other community and a place where its members could engage in a proper face-to-face interaction (Anderson, Citation1991, pp. 6–8).

Diaspora identity has a slightly different practice. Diaspora refers to a conscious disbandment of a population to various places that are geographically detached from one another, while diaspora identity is a set of characteristic that defined the fact of being whom or what a person or thing is. Therefore, diaspora identity is the identity of the people who, in conducting the diaspora, managed to create an entirely new identity, recalibrating their position from their casual past and paving a distance between the past and the present, while questioning their linkages to the ancestral land and descendants and lost particular memories (Hall, 1990, p. 235). In the case of the Malay-Bugis, identity was not perceived as an essential identity, and this explains how they could be further installed into the Malay world configuration. Previously, Hall (2010) had explained that diaspora identity could generate a rather hybrid identity. Thompson (1997, p. 17in Hall, Citation1997Citation1997, p. 17). added that the articulation of identity is the key to understanding how conflicting discourse may produce similarities, connections, and even interactions in the broad cultural space.

The people who belonged to the Malay-Bugis community were constructing their new identity, known as the diaspora identity, to adjust to a situation where they were no longer considered part of the whole Bugis community of individuals who were born and raised in South Sulawesi. In contrast from this original group, the Malay-Bugis community already had a more hybrid configuration both culturally and politically. The Buginese in Malaysia, who now proudly identify themselves as the Malay-Bugis, are part of Malaysia, while representing their own cultural identity based on the diaspora identity they brought and transmitted from one generation to another.

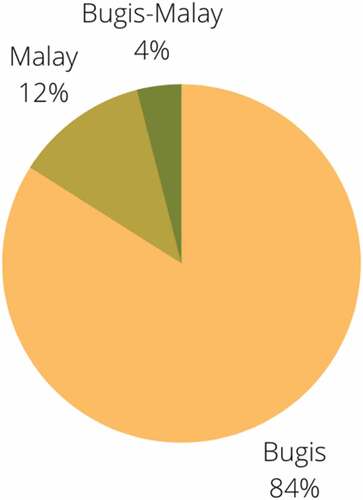

This identity can be seen in the statistical data gathered from a questionnaire presented to 42 respondents who were of Malay-Bugis descent. The first question asked respondents how they would like to be identified. As shows, eighty-four per cent of the respondents wanted to be identified as Buginese.

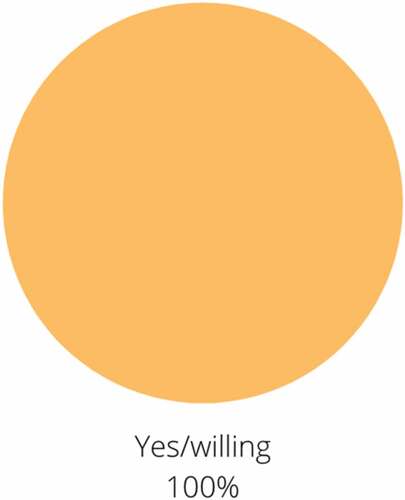

The next question explored their willingness to be identified further as Malay-Bugis. shows that, without exception, respondents agreed to this identification.

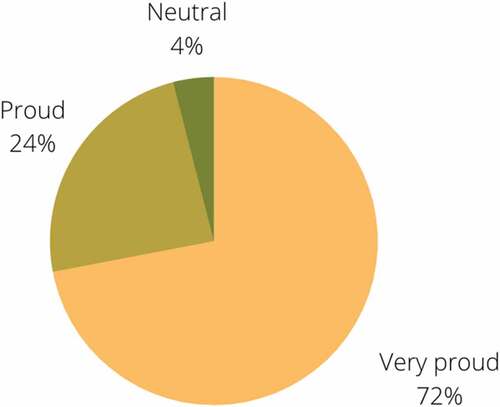

However, respondents were still proud of the narrative of origins and the ancestral tradition and practice, which actually originated in South Sulawesi. They even kept some traditions and practices alive by establishing customary institutions, museums, and various social media communities and groups on Facebook to showcase these linkages to the public. When asked whether they are proud of their identity as a Malay-Bugis, respondents expressed pride in their status as people of Malay-Bugis descent. As we could see, from below.

Thus, we can conclude that the identity of the Malay-Bugis people in a contemporary context and its representation on social media has influenced the way we see the identity of diaspora communities all around the world. By studying the articulation and reconstruction processes, this research paves the way for further analyses regarding Malay-Bugis efforts to trace and gather their collective memories in the past and shape present-time aggregation through social media platforms.

12. Conclusion

Identity is a construction, made by announcement and positioning of the self, either as an individual or as a group of people, toward entities outside of the self, who are called “others”. This research presented cultural identity as a sociocultural construction. By analysing various Facebook groups, we conclude that these groups have a strong tendency to re-articulate and re-construct their current identity based on the new narrative of origin and the outcome of diaspora activity carried out by their Bugis ancestors from the 17th century. By creating a link between their past identity and the currently adopted identity and eventually generating a connection between the diaspora community in Johor and Selangor, these groups reconstructed the Malay-Bugis identity. The Malay-Bugis descents believed that their identity—as part of the Buginese people who originated from South Sulawesi, Indonesia—was less essential because this identity had to share space with the identity they acquired in the present as Malaysian citizens.

While their situation did not preclude them from identifying as Buginese, let alone as Malay-Bugis, in reality they had agreed to the notion that identity might be perceived as an imaginary component that shaped their lives with both external and internal factors enveloping the construction. We also revealed that the Malaysian Buginese people are different from the Buginese in South Sulawesi because the Malaysian Buginese had already become part of Malaysia. Hence, their Buginese identity became less essential, in the sense that it could be seen as an ever-transforming identity, influenced by on going history, culture, and authority. Thus, history left both identities connected and disconnected at the same time, while transformation and transmission would have kept both identities intact.

Hence, we present two major conclusions from this research. First, the arrival of the Bugis diaspora in the Malay Peninsula area was encouraged by a combination of political, social, and cultural factors from the migration of the Buginese who refused to surrender to Dutch colonists in the Treaty of Bongaya to the narrative of origin as accomplished seamen in the Southeast Asian maritime world. The Buginese were also known as pioneers of the establishment of Malay sultanates, which led to the establishment of the country of Malaysia.

Second, the preservation of cultural values and practices was carried out through numerous Facebook accounts, announcing and positioning the Malay-Bugis identity via social media branding. We considered this use of social media as an important step in bridging the gap between the past and the present, especially as it is explored more deeply and for specific purposes, such as the legitimation of political prowess, making identity a forever contested and articulated element of the Malay-Bugis people’s lives.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Indonesian Ministry of Research, Technology, and Higher Education’s Research under grant number NKB-119/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2020, managed by the Directorate of Research and Community Engagement of Universitas Indonesia, and led by Dr. Linda Sunarti, M.Hum.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Linda Sunarti

Linda Sunarti is a faculty member of the Faculty of Humanities, Universitas Indonesia. She is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of History, Faculty of Humanities, Universitas Indonesia. She has conducted research across multiple fields in history, particularly in relation to Southeast Asian studies, international relations, diplomacy, and politics.

Raisye Soleh Haghia is a Doctoral Student in the History Department of the Faculty of Humanities, Universitas Indonesia. She is also an Associate Lecturer at the same university. She has an interest in studying mass media in a historical context, as well as the history of society and politics in Indonesia.

Noor Fatia Lastika Sari is an Associate Lecturer in the History Department of the Faculty of Humanities, Universitas Indonesia. She graduated from the Master’s Program at the same university. Focusing her work on the history of Australia and the Pacific, she finds the relation between Australian culture and history uniquely captivating as well as challenging to study. Her research about the continent focuses mainly on cross-borders issues and the maritime border between Indonesia and Australia.

References

- Y. (2015). Identitas Orang Melayu di Hulu Sungai Sambas. Jurnal Khatulistiwa, 5(1), 74–16.

- Ammarell, G. (2000). Bugis migration, ethnic conflict, and national integration. Antropologi Indonesia, 1, 491-495. .

- Anderson, B. (1991). Imagined Communities: Reflection on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso.

- Barker, C. (2000). Cultural studies: Theory and practice. Sage Publications.

- Eisenlauer, V. (2013). A Critical Hypertext Analysis of Social Media. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Fikri, A. R. M. (2018). Sejarah media: Transformasi, pemanfaatan, dan tantangan. UB Press.

- Gusnelly (2014). Studi Dinamika Identitas di Asia dan Eropa. Ombak.

- Hall, S. (1996). Cultural identity and diaspora. In P. Mongia (Ed.), Contemporary postcolonial theory: A reader (pp. 110–121). Bloomsbury Academic.

- Hall, S. (ed.). (1997). Representation: Cultural Representation and Signifying Practices.

- Hall, S. (ed.). (1997). Representation: Cultural Representation and Signifying Practices. London: Sage Publication.

- Li, M. (2000). Articulating indigenous identity in Indonesia: Resource politics and the tribal slot. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 42(1), 149–179. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417500002632

- McLean, S. (1982). Humanity in the Thought of Karl Barth. T&T Clark Ltd.

- McLuhan, M. (2001). Understanding media: The extension of man. McGraw Hill.

- McQuail, D. (2010). Mass Communication Theory. Sage Publications.

- Paeni, M. (2020, August 26). Diaspora bugis-makasar. [Online focus group discussion]. Posted to https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC7eGMvvTsJhMlVVYAMzD4Tw

- Pavlik, J. V., & McIntosh, S. (2004). Converging Media: An Introduction to Mass Communication. Allyn & Bacon.

- Pelras, C. (2006). Manusia Bugis. Jakarta: Nalar.

- Piliang, Y. A. (2014). Transformasi budaya sains dan teknologi: Membangun daya kreativitas. Jurnal Sosioteknologi, 13(2), 76-83.

- J. Ruthenford (Ed.). (1990). Identity, Community, Culture, Difference. Lownerk & Wishant.

- Saripaini & Yusriadi. (2016). Identitas orang bugis di dabong, kalimantan barat. Jurnal Katulistiwa. 170–182 doi:10.24260/khatulistiwa.v6i2.649.

- Sudibjo, A. (2019). Jagat Digital: Pembebasan dan Penguasaan. Gramedia.

- Sutherland, H. (2001). The makassar Malays: Adaptation and identity, ca. 1600 – 1790. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 32(3), 397–421. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022463401000224

- Watie, E. D. S. (2011). Communication and social media. The Messenger, 3(1), 69–74. https://doi.org/10.26623/themessenger.v3i2.270

- Zaenudin, D. (2011). Diaspora Bugis di Sabah, Malaysia Timur. LIPI Press.

- Zhao, S. (2008). Identity construction on Facebook: Digital empowerment in anchored relationships. Computers in Human Behavior.