Abstract

A 68 year-old female presents with an ulcerated mass of the 5th digit, with rapid growth during the previous month to surgery. The mass was excised and covered with a 4th dorsal metacarpal artery perforator flap. The histologic analysis was compatible with the diagnosis of fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the digit.

Introduction

The hand surgeon acts both as an oncological surgeon, ablating all the tumor mass, potentially compromising aesthetics and function, and as a reconstructive surgeon, trying to optimize hand function. Balancing these goals may be a demanding task [Citation1].

Even though the majority of hand tumors are benign, especially if they do not involve the skin, some malignant tumors arise in the hand. In the latter, a more aggressive approach would be justified [Citation2].

Fibro-osseous Pseudotumor of the Digits (FOPD) is a rare benign tumor with clinical characteristics that can mimic a malignant tumor. We present a case of FOPD and a review of the literature.

Case description

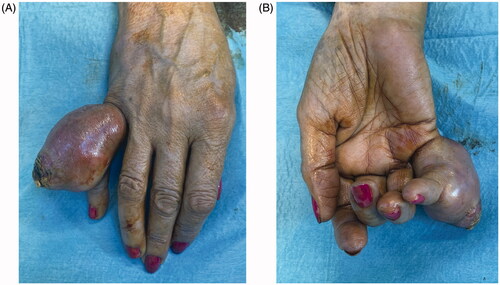

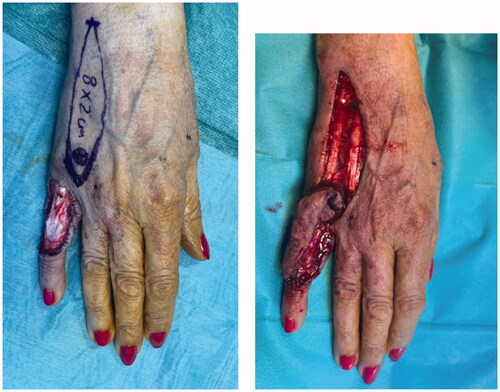

A 68 year-old female, smoker, presented to the ER with an ulcerated mass of the dorsum of the 5th finger involving the proximal phalanx to the DIP joint (). It had been progressively enlarging for the past year with substantial growth in the previous month. It was presented as a painless mass that limited PIP flexion. The neurovascular examination was normal. The ultrasound showed a 4.4 × 2.6 cm hypoechogenic mass with a significant doppler sign.

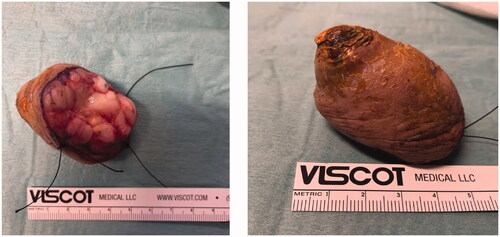

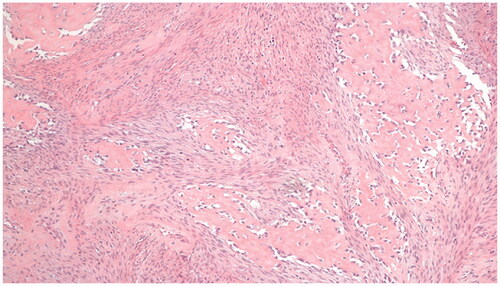

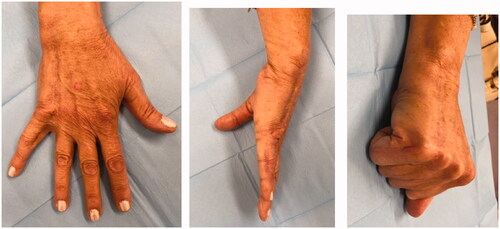

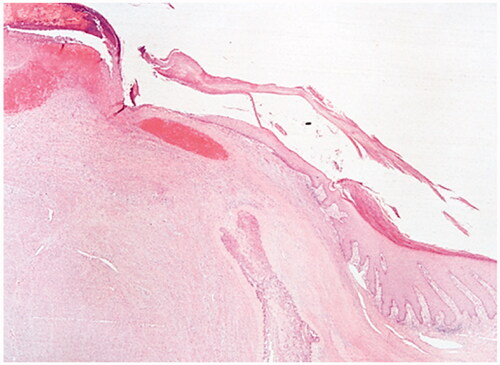

Excision with the overlying skin was performed down to a tumor less surgical plane, preserving the extensor apparatus (). The resulting defect was covered with a 4th dorsal metacarpal artery perforator flap and the donor area primarily closed (). Histopathological study revealed a lobulated tumor, self-limited and centered in the dermis, causing epidermal ulceration. Histologically, it is composed of fascicles of uniform spindle cells, admixed woven bone without zonation. There’s a mixture of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, arranged in hyper and hypocellular hyalinized areas and deposits of osteoid rimmed by uniform osteoblasts. Cells have bland cytology and no necrosis or mitotic figures are seen, compatible with the diagnosis of FOPD ( and ). The patient was followed for 22 months with no evidence of recurrence ().

Figure 3. Intra-operative views after surgical excision of the tumor with preservation of the extensor apparatus (A) and after raising the flap (B).

Figure 4. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of digits. The lesion presents as a well-circumscribed dermal mass, with epidermal ulceration. Hematoxylin-eosin × 25.

Discussion

FOPD is a rare entity. There are 173 cases documented in the literature [Citation3–54], totaling 174 with the present case report (). The first case dates back to 1931. There have been several terms to classify this entity including: ‘pseudo-malignant osseous tumor of soft tissue’ [Citation36], ‘parosteal fasciitis’ [Citation49], and ‘florid reactive periostitis’ [Citation3,Citation4,Citation7,Citation13]. This disease was unified under the term ‘fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the digits’ in 1986 by Dupree and Enzinger [Citation50]. The tumor is characterized by reactive fibroblastic proliferation and focal bone formation limited to the skin and subcutaneous tissue. The tumor is not of bone origin, though [Citation52]. It presents as an enlarging mass, which can be tender or painless. Even though a history of trauma has been described in as many as 40% of patients, it is hard to assess the relevance and prevalence of injury since minor trauma of the extremities is common. Skin ulceration may occur; the tumor mimics pyogenic granuloma, especially if it affects the toes [Citation7,Citation31,Citation38,Citation48]. Due to its growth and local aggressiveness, it can simulate malignancies. When mentioned, we found a high rate of suspicion of sarcoma [Citation14,Citation19,Citation50,Citation51], namely osteogenic sarcoma. Some case series did not report the individual patient data regarding age [Citation19,Citation46,Citation50]. The age ranged from 5 to 81, with a mean age of 36 and a median of 30 years old. The majority of patients were female (56.9%, 99 cases). It is more frequent in the upper limb (82.6%) than in the lower limb (16.9%). There is a sole case of FOPD outside the extremities [Citation28]. In the upper limb, the most common segment affected is the finger (76.8%), more precisely the 2nd finger (32%) and the proximal phalanx (62.3%), followed by the hand (21.1%) and wrist (2.1%).

Table 1. FOPD reported cases in the literature.

Radiologically, FOPD usually presents as a soft tissue mass with ill-defined margins and might reveal extraosseous ossification and bone formation. The periosteal reaction has been described [Citation42]. Cortical involvement or bony destruction seldom occurs. MRI findings are commonly non-specific and frequently demonstrate a non-invasive soft tissue mass.

Histologically, FOPD presents as a multi-nodular lesion with irregular margins and it is localized in the dermis and subcutaneous tissues. Muscular and cartilage involvement is absent.

Typically, FOPD shows fibroblastic/myofibroblastic proliferation without atypia, in a myxoid stroma, and immature trabeculae with osteoid rimmed by osteoblasts, without zoning phenomenon [Citation10,Citation23,Citation51]. Osteoclasts and bone marrow elements are rarely seen [Citation42].

Immunohistochemically, the majority of studies has demonstrated positive staining for vimentin 14 [Citation11,Citation21,Citation25,Citation26,Citation34], and focal reactivity to actin [Citation18,Citation21,Citation26,Citation27,Citation40,Citation51,Citation53], which is in favor of myofibroblastic differentiation [Citation18]. There is, however, controversial data, since Chan et al. found no reactivity to actin, myosin, myoglobin, desmin, and no dense bodies on electron micrograph, which is against the involvement of myofibroblasts [Citation11], and Sayar et al. found no evidence of immune-reactivity to actin and desmin [Citation34].

The majority of cases demonstrated negative staining to S – 100, CD 34, cytokeratin (MAK-6 and CAM 5.2), desmin, and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) [Citation3,Citation11,Citation18,Citation25–27]. Diagnosis is challenging – FOPD is a rare disease with only 174 cases documented, and it shares many histological and clinical features with malignant disease. This might lead to incorrect diagnoses, such as extraskeletal osteosarcoma, resulting in unnecessary procedures, including amputation. It should, however, be considered as a potential diagnosis of fast-growing tumors of the hand or feet with no previous history of trauma [Citation42]. Osteosarcoma is usually diagnosed in older people (scarcely under 40) and is rarely found in the fingers, being more common in the large bones of the upper and lower extremities [Citation42]. Myositis ossificans has been associated with FODP, being the latter considered by some authors as a superficial variant of the first. However, in myositis ossificans there is commonly a history of trauma [Citation38,Citation42,Citation51]. Other differential diagnosis include bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation (Nora’s lesion), ossifying plexiform tumor, acral osteoma cutis, and subungual exostosis [Citation45,Citation50].

FOPD might be included in a group of USP-6-rearranged myofibroblastic neoplasms that share a genetic rearrangement of the USP-6 gene and are known for their rapid yet self-limited growth and low recurrence rate [Citation52,Citation55]. Recent studies have identified COL1A1-USP6 fusions in the majority of their FOPD cases [Citation50,Citation52,Citation56]. Molecular and genetic studies can therefore help diagnosis and avoid over-treatment, particularly in cases where biopsy is difficult to obtain [Citation52,Citation55], or clinical history is insufficient [Citation52] since these lesions frequently mimic soft tissue sarcomas [Citation52], but are self-limited and can be cured with a more conservative surgical excision [Citation55].

The treatment for FOPD is surgical excision. Prognosis is excellent as recurrence has been related to incomplete excision [Citation10,Citation11,Citation42]. We found 13 cases in which amputation was the treatment of choice [Citation4–11,Citation23,Citation25,Citation27,Citation39]. Some of these cases were initially suspected or diagnosed as malignant – de Silva and Reid described a 13% of malignancy assumption by radiologists and a 9% incorrect malignant diagnosis by pathologists [Citation23], while in others the extension of the disease and bone destruction led the surgeons to decide for amputation.

Nine cases of recurrence were described in the literature [Citation6,Citation8–11,Citation15,Citation23,Citation31,Citation43]. Most of them did not provide information about the reason for the recurrence. However, in three cases incomplete excision seems to be the reason for it thus reinforcing the need for complete excision.

After complete removal of the tumor, no recurrences were found with a median follow up of 15 (4–168) months [Citation4,Citation5,Citation7–16,Citation19,Citation21–25,Citation28–31,Citation34–37,Citation40–46,Citation48,Citation53]. Even though no malignant transformation has been described in the literature, close follow-ups are recommended.

Conclusion

FOPD should be considered in the differential diagnosis of fast-growing lesions of the extremities. An excisional biopsy allows for complete tumor removal and avoids overzealous treatment. FOPD should be treated without radical excisions provided if totally removed.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Sacks JM, Azari KK, Oates S, et al. Benign and malignant tumors of the hand. In: Plastic surgery: hand and upper extremity, Vol. 6. London: Elsevier; 2018. p. 334–354.

- Plate A-M, Steiner G, Posner MA. Malignant tumors of the hand and wrist. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(12):680–692.

- Mallory TB. A group of metaplastic and neoplastic bone- and cartilage-containing tumors of soft parts. Am J Pathol. 1933;9(Suppl):765–776.

- Goncalves D. Fast growing non-malignant tumour of a finger. Hand. 1974;6(1):95–97.

- McCarthy EF, Ireland DC, Sprague BL, et al. Parosteal (nodular) fasciitis of the hand. A case report. JBJS. 1976;58(5):714–716.

- Spjut HJ, Dorfman HD. Florid reactive periostitis of the tubular bones of the hands and feet. A benign lesion which may simulate osteosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1981;5(5):423–433.

- De Smet L, Vercauteren M. Fast-Growing pseudomalignant osseous tumour (myositis ossificans) of the finger. A case report. J Hand Surg. 1984;9(1):93–94.

- Bulstrode C, Helal B, Revell P. Pseudo-malignant osseous tumour of soft tissue. J Hand Surg. 1984;9(3):345–346.

- Patel MR, Desai SS. Pseudomalignant osseous tumor of soft tissue: a case report and review of the literature. J Hand Surg. 1986;11(1):66–70.

- Dupree WB, Enzinger FM. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the digits. Cancer. 1986;58(9):2103–2109.

- Chan KW, Khoo US, Ho CM. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the digits: report of a case with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies. Pathology. 1993;25(2):193–196.

- Franchi A, Nesi G, Carassale G, et al. Fibroosseous pseudotumor of the digit: report of a case. J Hand Surg. 1994;19(2):290–292.

- Aboujaoude J, Bocquet L, Oberlin C. Pseudo-tumeur fibro-osseuse des doigts. Une entité méconnue: À propos d’un cas chez une fillette de 11 ans. Ann Chir Main Memb Supér. 1995;14(1):43–48.

- Horie Y, Morimura T. Fibro-Osseous pseudotumor of the digits arising in the subungual region: a rare benign lesion simulating extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Pathol Int. 1995;45(7):536–540.

- Prevel CD, Hanel DP. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the distal phalanx. Ann Plast Surg. 1996;36(3):321–324.

- Riaz M, McCLUGGAGE WG, Bharucha H, et al. Florid reactive periostitis of the thumb. J Hand Surg. 1996;21(2):276–279.

- Tang J-B, Gu YQ, Xia RG. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor that may be mistaken for a malignant tumor in the hand: a case report and review of the literature. J Hand Surg. 1996;21(4):714–716.

- Sleater J, Mullins D, Chun K, et al. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the digit: a comparison to myositis ossificans by light microscopy and immunohistochemical methods. J Cutan Pathol. 1996;23(4):373–377.

- Moon SE, Park BS, Kim JA, et al. Subungual fibro-osseous pseudotumor. Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;77(3):247–248.

- Takahashi A, Tamura A, Ishikawa O. A case of fibro-osseous pseudotumour of the digits. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144(6):1274–1275.

- Nishio J, Iwasaki H, Soejima O, et al. Rapidly growing Fibro-Osseous pseudotumor of the digits mimicking extraskeletal osteosarcoma. J Orthop Sci. 2002;7(3):410–413.

- Solana J, Bosch M, Español I. Florid reactive periostitis of the thumb: a case report and review of the literature périostite Floride Du Pouce: Cas Clinique et Revue de La Littérature. Chir Main. 2003;22(2):99–103.

- de Silva MVC, Reid R. Myositis ossificans and fibroosseous pseudotumor of digits: a clinicopathological review of 64 cases with emphasis on diagnostic pitfalls. Int J Surg Pathol. 2003;11(3):187–195.

- Hirao K, Sugita T, Yasunaga Y, et al. Florid reactive periostitis of the metatarsal bone: a case report. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26(9):771–774.

- Coleman RA. Fibro-osseous pseudotumour of the digit-amputation for a benign but aggressive lesion. J Hand Surg Br. 2005;30(5):504–506.

- Usta U, Bafi M, Aydin NE, et al. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the digits. Med J Trakya Univ. 2007;24(1):77–80.

- Moosavi CA, Al-Nahar LA, Murphey MD, et al. Fibroosseous [corrected] pseudotumor of the digit: a clinicopathologic study of 43 new cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2008;12(1):21–28.

- Nalbantoglu U, Gereli A, Kocaoglu B, et al. Aktas, S. Fibro-Osseous pseudotumor of the digits: a rare tumor in an unusual location. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33(2):273–276.

- Kaddoura I, Zaatari G. Fibro-Osseous pseudotumor of the thenar eminence: a rare aggressive but benign tumor. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;62(3):326–328.

- Bettex S, Guillou L, Jovanovic B, et al. [Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the thumb. Report of a case]. Chir Main. 2009;28(2):107–112.

- Chaudhry IH, Kazakov DV, Michal M, et al. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the digit: a clinicopathological study of 17 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37(3):323–329.

- Song W-S, Choi J-C, Kim H-S, et al. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the great toe: a case report. J Korean Bone Joint Tumor Soc. 2010;16(2):91–94.

- Tan K-B, Tan S-H, Aw DC-W, et al. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the digit: presentation as an enlarging erythematous cutaneous nodule. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16(12):7.

- Sayar H, Yilmaz A, Bal N. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of toe: a case report. Turk Klinikleri J Med Sci. 2010;30(5):1720–1723.

- Anand M, Deshmukh SD, Devasthali DA. Fibro-osseous pseudotumour of the metacarpal. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2011;36(8):701–702.

- Lee DH, Ko HR, Song EJ, et al. A case of fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the digit. Korean J Dermatol. 2012;50(6):536–538.

- Seeger M, Schulte D, Winiker H. Fibroossärer Pseudotumor in der Hohlhand eines 5-jährigen Jungen – ein naher Verwandter der Myositis ossificans. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2012;44(3):178–180.

- Javdan M, Tahririan MA. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the digit. Adv Biomed Res. 2012;1(31):31.

- Cornec D, Le Nen D, Saraux A. Fibro-osseous pseudotumour of the digit in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2013;52(5):779–779..

- Hashmi A, Faridi N, Edhi M, et al. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the digit presenting as an ulcerated lesion: a case report. Int Arch Med. 2014;7(1):4.

- Kwak MJ, Kim SK, Lee S-U, et al. Radiological features of a fibro-osseous pseudotumor in the digit: a case report. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2015;73(2):131–135.

- Zhou J, McLean C, Keating C, et al. Fibro-osseous pseudotumour of the digit: an illustrative case and review of the literature. Hand Surg. 2015;20(3):458–462.

- Meani RE, Bloom RJ, Battye S, et al. Subungual fibro-osseous pseudotumour of the toe: subungual FOPT of the toe. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57(2):e57–e60.

- Kontogeorgakos VA, Papachristou DJ, Varitimidis S. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the hand. J Hand Surg Asian Pac Vol. 2016;21(2):269–272.

- Choi K-H, You JS, Huh JW, et al. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the digit: a diagnostic pitfall of extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28(4):495–496.

- Singal A, Gogoi P, Pandhi D, et al. Subungual fibro-osseous pseudotumour of the digit: a rare occurrence. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56(1):e11–e13.

- Gómez-Zubiaur A, Pericet-Fernández L, Vélez-Velázquez MD, et al. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the digits mimicking pyogenic granuloma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34(3):e126–e127.

- Cho YS, Park SY, Choi YW, et al. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the digit presenting as an enlarging erythematous subungual nodule. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29(4):497–499.

- Takahashi K, Kumata T, Sugita K, et al. Fibro-osseous pseudotumour of the digit associated with prominent bone formation: time course of the tumour and clinicopathology. Eur J Dermatol. 2018;28(3):386–387.

- Flucke U, Shepard SJ, Bekers EM, et al. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of digits – expanding the spectrum of clonal transient neoplasms harboring USP6 rearrangement. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2018;35:53–55.

- Jawadi T, AlShomer F, Al-Motairi M, et al. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the digit: case report and surgical experience with extensive digital lesion abutting on neurovascular bundles. Ann Med Surg. 2018;35:158–162.

- Švajdler M, Michal M, Martínek P, et al. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of digits and myositis ossificans show consistent COL1A1-USP6 rearrangement: a clinicopathological and genetic study of 27 cases. Hum Pathol. 2019;88:39–47.

- Sakuda T, Kubo T, Shinomiya R, et al. Rapidly growing fibro-osseous pseudotumor of the digit: a case report. Medicine. 2020;99(28):e21116.

- Rela M, Bantick G. Fibro-osseous pseudotumour of the digit—a diagnostic challenge. J Surg Case Rep. 2020;5:rjaa125.

- Malik F, Wang L, Yu Z, et al. Benign infiltrative myofibroblastic neoplasms of childhood with USP6 gene rearrangement. Histopathology. 2020;77(5):760–768.

- Wang J, Li W, Kao Y, et al. Clinicopathological and molecular characterisation of USP6-rearranged soft tissue neoplasms: the evidence of genetic relatedness indicates an expanding family with variable bone-forming capacity. Histopathology. 2021;78(5):676–689.