Abstract

We report a case of malignant transformation of a phalangeal enchondroma into a grade II chondrosarcoma requiring two successive transcarpal amputations owing to recurrence. Soft tissue defects were repaired using single-stage reconstruction with a posterior interosseous artery flap. The 2-year follow-up assessment was satisfactory and no recurrence was observed.

Introduction

Chondrosarcomas are the most common primary malignant bone tumor except for osteosarcomas [Citation1]. They represent 20%–27% of all primary bone tumors and their occurrence is equally distributed with respect to gender, with a reported incidence of 1:200,000–1:500,000 [Citation2–4].

Sites where they commonly occur are the pelvis, proximal femur, and proximal humerus in patients aged between 50 and 70 years [Citation3]. Hand chondrosarcomas are rare, accounting for 1.5%–3.2% of all chondrosarcomas [Citation5,Citation6]. They usually involve the phalanges, metacarpals, trapezium, and trapezoid [Citation7].

These tumors are composed of cartilage-producing cells and usually present as slow-growing and painful masses. They are histologically classified into three grades: grade I or low, grade II or intermediate, and grade III or high [Citation8], with the majority of lesions belonging to the low-grade category [Citation9]. Oncological outcomes are mainly determined by histological grading: the higher the grade, the more likely it is that the tumor will metastasize [Citation4].

Although they may be primary tumors, chondrosarcomas can also result from the malignant transformation of a pre-existing lesion, such as enchondromas, multiple enchondromatosis, or osteochondromas [Citation6,Citation7,Citation10]. Benign solitary enchondromas are the most common tumors found in the hand and are usually located in the phalanges [Citation11]. It is difficult to differentiate between enchondromas and low-grade chondrosarcomas (LGCS) because of their similar appearance on radiography and biopsy [Citation12]. Intermediate- and high-grade chondrosarcomas demonstrate more specific signs, such as perilesional edema and cortical destruction. LGCS are usually treated by means of amputation, however, more recent literature advocates for intralesional surgery [Citation4]. Wide resection is usually recommended to avoid recurrence, as adjuvant therapies are ineffective [Citation13].

It is particularly challenging to manage soft tissue defects of the hand following wide-margin resection because numerous underlying structures such as bones, tendons, vascular pedicles, and nerves are exposed. Various types of hand reconstruction techniques and skin flaps have been described, to preserve limb function as well as the integrity of underlying structures; however, the posterior interosseous artery (PIA) flap is the option that was selected by us. These flaps are known to be reliable for wrist and hand reconstruction in the background of traumatic soft tissue defects [Citation14] and following resection of soft tissue [Citation15].

In this case report, we describe a rare case of a patient initially treated with curettage and bone filling for a symptomatic enchondroma of the fourth proximal phalanx that presented with malignant transformation to secondary chondrosarcoma (Grade II) at the first follow-up at one year following initial treatment. We performed a wide resection of the 4th ray, and a recurrence of the lesion was discovered again at the 8-month follow-up, which resulted in ulnar transcarpal amputation. The hand defect was repaired using a posterior interosseous artery flap, and at the follow-up 2 years after transcarpal amputation, the clinical evaluation was satisfactory.

Case report

A 66-year-old Caucasian man with no significant medical history was referred to our department of hand surgery and treated for an enchondroma of the proximal phalanx of the fourth ray of the left hand with curettage and bone filling using a cancellous allograft. Anatomopathological analysis revealed an enchondroma without malignancy.

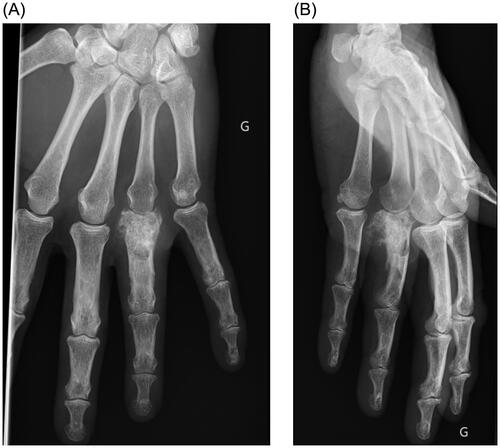

A year later, the patient presented with a mass appearing next to the metacarpophalangeal joint on the fourth ray, along with persistent pain. Standard radiographs revealed bone lysis and periosteal reaction suggestive of malignant evolution of the previous lesion’s remnants into chondrosarcoma (). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was also performed to determine the extent of the tumor. Biopsy confirmed the presence of a grade 2 chondrosarcoma. The patient then underwent tumor resection with amputation of the fourth ray at the base of the metacarpal, as per the modified Le Viet technique (). The resected specimen was sent for pathological analysis to confirm chondrosarcoma and determine appropriate surgical margins.

Figure 1. (A) Plain AP view of the hand, bone lysis and periosteal reaction are visible on the proximal phalanx of the fourth ray. G Left side (in French: Gauche). (B) Plain lateral view of the hand. G Left side (in French: Gauche)

Figure 2. Plain AP view of the hand after amputation of the fourth ray, as per the modified Le Viet technique. G Left side (in French: Gauche).

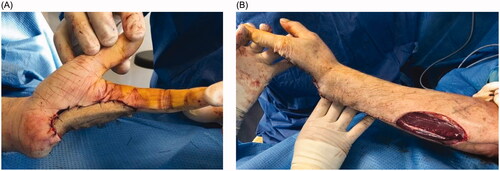

Unfortunately, recurrence was observed 8 months following the resection. Local revision surgery was performed, prior to which the patient was informed of the intraoperative risk of amputation being required in the forearm. Transcarpal amputation was performed, and only the first two rays of the hand were preserved (). The motor branch of the ulnar nerve was preserved. To avoid instability and radialization of the wrist, the extensor carpi ulnaris tendon was preserved and fixed to the triquetrum using an anchor (Non-absorbable Mitek© 3.0). The defect was covered with a posterior interosseous flap ().

Figure 4. (A) Palmar view of the hand after the defect was covered with a posterior interosseous flap. (B) Dorsal view of the forearm with the donor site.

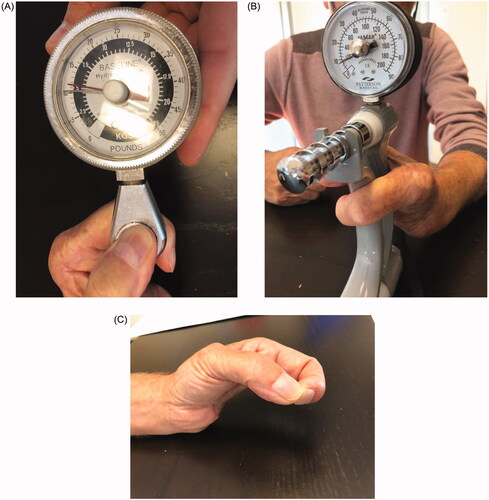

The evolution of the flap was favorable. Two years later, the patient showed satisfactory functional outcomes, without any signs of local or distant recurrence. No complications occurred at the donor sites. The patient reported no hand or wrist pain at the last follow-up. The thumb-index force was 5.5 kg and the wrist was capable of generating a force of 10 kg (). The patient was able to perform most activities of daily living by this juncture.

Discussion and conclusions

Asymptomatic enchondromas are usually incidental findings that do not require immediate treatment. On radiographs, they are intramedullary lucent lesions with lobulated contour, endosteal scalloping, and chondroid calcification [Citation16]. Enchondromas can simply be observed, and radiographic follow-up is not required. However, when symptoms such as pain, swelling, deformity, or pathological fractures are present, surgical treatment is recommended [Citation17].

Moreover, pain in the absence of a pathological fracture can be an important feature to differentiate LGCS from enchondromas, which are usually painless because of their slow growth, minimal peritumoral reaction, and avascularity [Citation6]. This differentiation is essential in the selection of an appropriate treatment modality and for decreasing the rate of recurrence. First-line treatment of enchondromas comprises of intralesional curettage and filling of the defect using autologous or allogenic bone grafting or augmentation [Citation17]. Single-stage curettage is usually preferred over delayed surgery [Citation18,Citation19]. Another possible surgical procedure that may be indicated is additional plate fixation to reduce the risk of nonunion of displaced pathological fractures [Citation20]. To decrease the rate of recurrence and eliminate residual tumor cells, surgical adjuncts such as bone cement can be used [Citation21]. In our case, defect filling following curettage was performed by augmentation using a cancellous allograft.

Recurrence of enchondromas is uncommon, and malignant transformation of a benign enchondroma or multiple enchondromatosis to secondary chondrosarcomas in the hand is extremely rare [Citation6]. Some conditions, such as Ollier disease or Maffucci syndrome, characterized by multiple enchondromas, are associated with a high malignant transformation rate, varying from 20% to 57% [Citation10]. Nevertheless, in our case, a malignant transformation of an enchondroma to a grade II chondrosarcoma was observed.

Our case report highlights the difficulty in differentiating between enchondromas and low-grade chondrosarcomas at the time of initial diagnosis. When in doubt, apart from standard clinical as well as radiological evaluations, MRI and histopathological evaluations should be performed. In our patient, the biopsy revealed a benign enchondroma without histological features suggestive of malignancy. Welkerling et al. reported that the same biopsy can be graded differently by different labs [Citation22]. This caveat must be kept in mind by hand surgeons, who will inevitably treat many enchondromas during the course of their careers.

Chondrosarcomas vary from low-grade, which are relatively benign to high-grade, or dedifferentiated tumors which are associated with very poor survival rates [Citation4]. On the hand, primary chondrosarcomas are rare entities, found in phalangeal bones in 60% of cases and in the metacarpals in the remaining 40% of cases [Citation23]. Radiography shows intralesional calcification with the popcorn-like pattern, cortical erosion, periosteal reaction, and soft tissue mass [Citation16]. An LGCS of the hand behaves as a locally aggressive lesion and, in contrast to chondrosarcomas located in the talus and calcaneus, rarely metastasizes [Citation13]. Nevertheless, pulmonary metastasis has been reported in higher-grade tumors [Citation6]. Historically, LGCS are treated by wide-margin resection, however, recently there has been a tendency to perform intralesional surgery with curettage, along with the concurrent use of local adjuvants, such as phenol, bone polymethyl methacrylate and cryotherapy [Citation4]. Dierselhuis et al. reviewed 18 studies and concluded that intralesional treatment is associated with better functional outcomes and equal recurrence-free survival compared to wide-margin resection [Citation4]. In grade II chondrosarcomas, as in our case, wide resection of local healthy tissue is required, to avoid local recurrence or metastases [Citation24]. We first performed a trans-metacarpal osteotomy of the fourth ray, which was as per a modified version of the original Le Viet technique [Citation25,Citation26]. Following the diagnosis of the second recurrence, we performed a partial amputation of the fifth and third rays, which resulted in a large soft-tissue defect. In similar cases, hand amputation is also a viable treatment option [Citation5].

In large soft tissue defects, the primary focus is to minimize donor site morbidity and at the same time, to obtain sufficient flap coverage to preserve limb function. In our case, we chose a PIA flap as a therapeutic option for reconstruction. It was first described as a reverse-flow pedicle flap in 1986 [Citation27–30] and provides a reliable flap with adequate vasculature. to cover wrist and hand defects [Citation31]. The PIA flap does not sacrifice the major blood vessels of the hand because it relies on the posterior interosseous artery and its anastomosis with the anterior interosseous artery, which offers a much-needed alternative option, when the radial or ulnar artery is damaged or when palmar arches are absent. Jones et al. reported that the reverse radial forearm and contralateral free radial forearm flaps are more reliable than the posterior interosseous flap for the coverage of moderate-sized defects of dorsal or palmar hand and wrist defects following trauma or tumor resection [Citation32]. Ultimately, the choice of flap depends on the surgeon’s experience and preference for a particular technique.

In this report, we present a rare case of a phalangeal enchondroma that demonstrated malignant transformation into chondrosarcoma. Following resection of the fourth ray, recurrence was observed despite wide-margin resection being performed, leading to partial amputation of the ulnar ray of the hand. Although chondrosarcomas rarely metastasize, local aggressiveness has the potential to result in recurrence; therefore, clinical and radiological follow-up must be performed. There is no consensus regarding the management of chondrosarcomas of the hand, and large soft-tissue defects at this site remain challenging to tackle. Based on our experience, we suggest that the posterior interosseous artery flap remains an effective option to cover ulnar soft tissue defects following transcarpal amputation in cases of chondrosarcoma. Finally, it is recommended that such cases are approached by multidisciplinary teams comprising of orthopedicians, pathologists, and oncology specialists.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to participate in this study for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent form is available for review on request.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Evola FR, Costarella L, Pavone V, et al. Biomarkers of osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:150.

- Murphey MD, Walker EA, Wilson AJ, et al. From the archives of the AFIP: imaging of primary chondrosarcoma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2003;23(5):1245–1278.

- ESMO/European Sarcoma Network working group. Bone sarcomas: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 7):vii100–109.

- Dierselhuis EF, Goulding KA, Stevens M, et al. Intralesional treatment versus wide resection for central low-grade chondrosarcoma of the long bones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):CD010778.

- O"Connor MI, Bancroft LW. Benign and malignant cartilage tumors of the hand. Hand Clin. 2004;20(3):317–323. vi.

- Müller PE, Dürr HR, Nerlich A, et al. Malignant transformation of a benign enchondroma of the hand to secondary chondrosarcoma with isolated pulmonary metastasis. Acta Chir Belg. 2004;104(3):341–344.

- Chaudhary S, Singh D, Sen R. Chondrosarcoma of distal Radius- A case report and brief review of literature. Webmed Cent Orthop. 2010;1(12):WMC001274.

- Evans HL, Ayala AG, Romsdahl MM. Prognostic factors in chondrosarcoma of bone: a clinicopathologic analysis with emphasis on histologic grading. Cancer. 1977;40(2):818–831.

- Weinschenk RM, Wang W-L, Lewis VO. Chondrosarcoma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29(13):553–562.

- El Abiad JM, Robbins SM, Cohen B, et al. Natural history of Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome: patient survey and review of clinical literature. Am J Med Genet A. 2020;182(5):1093–1103.

- Simon MJ, Pogoda P, Hövelborn F, et al. Incidence, histopathologic analysis and distribution of tumours of the hand. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:182.

- Randall RL, Gowski W. Grade 1 chondrosarcoma of bone: a diagnostic and treatment dilemma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2005;3(2):149–156.

- Ogose A, Unni KK, Swee RG, et al. Chondrosarcoma of small bones of the hands and feet. Cancer. 1997;80(1):50–59.

- Cheema TA, Lakshman S, Cheema MA, et al. Reverse-flow posterior interosseous flap-a review of 68 cases. Hand. 2007;2(3):112–116.

- Wang JQ, Cai QQ, Yao WT, et al. Reverse posterior interosseous artery flap for reconstruction of the wrist and hand after sarcoma resection. Orthop Surg. 2013;5(4):250–254.

- Boriani F, Raposio E, Errani C. Imaging features of primary tumors of the hand. Curr Med Imaging. 2021;17(2):179–196.

- Lubahn JD, Bachoura A. Enchondroma of the hand: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24(9):625–633.

- Lin SY, Huang PJ, Huang HT, et al. An alternative technique for the management of phalangeal enchondromas with pathologic fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(1):104–109.

- Zheng H, Liu J, Dai X, et al. Modified technique for one-stage treatment of proximal phalangeal enchondromas with pathologic fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(9):1757–1760.

- Bachoura A, Rice IS, Lubahn AR, et al. The surgical management of hand enchondroma without postcurettage void augmentation: authors experience and a systematic review. Hand. 2015;10(3):461–471.

- Bickels J, Wittig JC, Kollender Y, et al. Enchondromas of the hand: treatment with curettage and cemented internal fixation. J Hand Surg Am. 2002;27(5):870–875.

- Welkerling H, Werner M, Delling G. Histologic grading of chondrosarcoma. A qualitative and quantitative analysis of 74 cases of the Hamburg bone tumor register. Pathologe. 1996;17(1):18–25.

- Wirbel RJ, Remberger K. Conservative surgery for chondrosarcoma of the first metacarpal bone. Acta Orthop Belg. 1999;65(2):226–229.

- García-Jiménez A, Chanes-Puiggrós C, Trullols-Tarragó L, et al. Chondrosarcoma of the hand bones: a report of 6 cases and review of the literature. J Hand Surg Asian Pac Vol. 2019;24(1):45–49.

- Le Viet D. Translocation of the fifth finger by intracarpal osteotomy. Ann Chir Main. 1982;1(1):45–56.

- Le Viet D, Dailiana ZH. Third and fourth finger ray amputations by intracarpal osteotomy. Tech Hand up Extrem Surg. 1999;3(2):110–115.

- Zancolli E, Angrigiani C. Colgajo dorsal de antebrazo (en isla) (pediculo de vasos interóseos posteriores). Rev Asoc Arg Ortop Traumatol. 1986;54:161–e168.

- Zancolli EA, Angrigiani C. Posterior interosseous island forearm flap. J Hand Surg Br. 1988;13(2):130–135.

- Lu LJ, Shoufu W, Jan Young E. The posterior interosseous flap: a report of 6 cases. Paper presented at: The Second Symposium of the Chinese Association of Hand Surgery, Qing Dao city; 1986, p. 187–191.

- Penteado CV, Masquelet AC, Chevrel JP. The anatomic basis of the fasciocutaneous flap of the posterior interosseous artery. Surg Radiol Anat. 1986;8(4):209–215.

- Vögelin E, Langer M, Büchler U. How reliable is the posterior interosseous artery island flap? A review of 88 patients. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2002;34(3):190–194.

- Jones NF, Jarrahy R, Kaufman MR. Pedicled and free radial forearm flaps for reconstruction of the elbow, wrist, and hand. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(3):887–898.