Abstract

This paper examines the bequest motives of Indian households in a context of changing demographic factors such as ageing and economic shocks such as the financial crisis of 2009, and demonetization in the year 2016. We employ a standardized questionnaire, and collect data from a random sample of 220 participants. The results indicate that self- interest has a negative association and social norms is positively associated with the intention to bequest. Further, altruism, religiosity and social norms negatively amplifies the relationship between self-interest and intention to bequest.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In this paper, we examine the bequest motives of Indian households in the context of changing demographic factors such as aging trends and the increasing percentage of the dependent population. Our study reveals that as self-interest increases the intention to bequest decreases. Households that are more sensitive to social norms have a higher probability of bequeathing than those who give lesser importance. Further, we find that altruism amplifies the negative relationship between self-interest and intention to bequeath. One plausible reason for this could be the desire for social recognition through charitable bequest outside the family. Demystifying bequest intentions of households is crucial in understanding wealth dynamics and for formulating policies such as tax treatment of savings, social insurance, and pension policies.

1. Introduction

According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division’s report on “Global and Regional Trends in Population Ageing”, 2017, the older population in developing regions is growing much faster relative to developed regions. The report projects that, by 2050, 79% of the world’s population aged 60 or over will be living in the developing regions. Given the aging trends in emerging economies and population growth in countries such as India, the old age dependency ratio, reflecting the percentage of dependent population, is expected to rise considerably. According to the India Vision 2020 report of the Planning Commission, Government of India, this trend is expected to be more pronounced in the southern states of India, which is projected to have a median age of 34 years in 2025 when compared to 26 in the year 2000. Population aging has implications for markets such as labor and financial, housing demand, and policies such as social protection, and inheritance tax laws. According to the Household Finance Committee Report published by the Reserve Bank of India in 2017, a large proportion of the wealth of Indian households is concentrated in physical assets such as gold and real estate. Moreover, the report documents that the debts of Indian households show an unusual pattern of peaking towards the retirement age when they are no longer earning income. It notes that the social arrangements through which households bequeath housing wealth to future generations is an important determinant of these patterns. However, the report argues that these traditional structures are increasingly under pressure due to shifting demographic patterns, and changes in social norms and economic conditions.

In this context, we explore the bequeathing behavior of Indian households. It is important to understand the bequest behavior of households from a public policy perspective, particularly for framing inheritance tax laws. Economic theory broadly classifies bequest into “altruistic bequest”, “strategic bequest”, and “accidental bequest”. According to the theory on altruistic bequest, parents try to maximize the marginal utilities of their children. Strategic bequest theory argues that parents provide additional compensation to children who provide more services. Accidental bequest occurs due to the premature death of the estate owner, resulting in an equal division of the estate among the children. While altruistic bequest reduces inequality, accidental bequests exacerbates it. Hence, from an inheritance tax perspective, the regularity of accidental bequest in a society warrants a higher inheritance tax rate. Lower inheritance tax rates in a society with equal estate division would potentially increase inequality. Furthermore, understanding the preferences of the asset-rich but cash-poor elderly is important from a financial products perspective. In India and similar developing markets, financial products for the elderly such as “reverse mortgage” have low levels of market penetration. A better understanding of the bequest behavior of households could potentially help in enhancing market penetration of products such as “reverse mortgage”.

Western countries have also dealt with the financial insecurities of the “asset- rich” but “cash-poor” elderly (Ong, Citation2008; Shan, Citation2011), a situation that has led to the widespread promotion of “reverse mortgage”. The extant literature categorizes the factors driving demand for the reverse mortgage product into socio-cultural, economic, institutional and behavioral.

In this paper, we attempt to spur a discussion about the bequest motives of Indian households in the prevailing context of rapidly changing demographic patterns, social norms, and economic conditions. More specifically, we examine the implications of altruism, religious belief, social norms, inheritance of wealth, and self-interest on the intention to bequest.

We collect data using a contextually modified questionnaire, originally employed by Wiepking, Scaife, and McDonald (Citation2012), to suit Indian conditions. We analyze the data using bivariate logistic regressions and two-way interactions, and t-tests for comparing means.

Our study finds that as self-interest increases the intention to bequeath decreases significantly. Moreover, altruism, religiosity, and social norms, negatively amplify the relationship between self-interest and intention to bequest. Contrary to the results of Horioka (Citation2014), the result of bivariate logistic regression did not find any significant effect of altruism on the intention to bequest. The t-test corroborates the finding that altruism does not significantly discriminate between households intending to bequeath and those who do not. The moderating effect of social norms and religiosity on the relationship between altruism and the intention to bequest were also not significant. Additionally, we find that households that place more importance on social norms have a higher probability to bequeath than those that do not. Our findings have important implications for firms in financial services and regulatory and policy making institutions in the domains such as inheritance tax laws, financial products such as a reverse mortgage, pension plans etc.

2. Theory and hypotheses

The relevance of bequest and other intergenerational transfers have been debated for more than three decades. In one of the earliest papers, Kotlikoff and Summers (Citation1981) documents that around 46% of wealth is accounted for by bequests. Some of the previous studies on bequests have a focus on the distribution of wealth during the different stages of the life cycle (e.g., Hurd, Citation1990; Menchik and David, Citation1983; Diamond and Hausman, Citation1984). Previous studies have also found evidence in support of the existence of the bequest motive (Joulfaian, Citation2004; Bernheim et al., Citation2004).

We initiate the discussion on bequest motives with some theoretical definitions of “bequest”. Although a bequest involves a gratuitous exchange of an asset’s legal status where the transferor has no legal duty to perform the transaction, it is invariably motivated by a variety of socio-economic reasons such as lack of family need, desire to be part of a good cause and spite as per the extant literature. The motives and barriers for making a bequest is a subject of much debate, and it implies and assumes that the unwritten agreements between family members are enforceable. As noted by Horioka (Citation2014), there are at least three competing assumptions concerning household preferences: individuals are selfish, they are altruistic and they have a desire for dynasty building.

This study deduces hypotheses from the general philanthropic and consumer behavior literature and tries to empirically capture the reasons underlying the intention to bequest or not to bequest. More specifically, in this paper, we focus on bequest behavior where the prospective donor received an inheritance from his/her forefathers.

2.1. Hypothesis development

2.1.1. Self-interest

A part of a selfish life-cycle model is also called “strategic bequests” under the exchange bequests. Individuals who are selfish would want their children to devote time and resources to them in their old age. Such people would bequeath their assets to the children who have promised to set aside time and resources for them (Lee & Xiao, Citation1998; Leopold & Raab, Citation2011). Bernheim et al. (Citation1985) developed the ‘“strategic bequest motive” where parents threaten their children with disinheritance in order to induce them to provide care, attention and financial support during their old age. Kotlikoff and Spivak (Citation1981) discussed the “‘implicit intra-family annuity contract,’” wherein parents receive a regular income from their children during old age till death in exchange for bequeathing their wealth to them.

The motive to bequest based on selfish interest has been found to exhibit a significantly weaker influence in India as compared to Japan, United States and China (Horioka, Citation2014). Although the altruistic motive is quite prevalent in the Indian culture, exchange-related selfish reasons are stronger in India.

Hypothesis 1: Self-interest influences the intention to leave a bequest.

2.1.2. Religious belief

People who believe strongly in religious values are more likely to help others. In all religions, helping others is considered an important religious value. Religious donors generally make large and structured donations (Bekkers and Wiepking, Citation2011). (Xiaonan Kou and Heidi Frederick, Citation2009) in their study observed that donors who visits church at least once a week are strongly more likely than those who are not religiously observant to have a charitable provision in their will. In contrast, Nair et al. (Citation2017) find that religious affiliation negatively affects intention to bequest. Thus, this study tried to explain the intention to leave a bequest with religious affiliation as an independent variable. This led us to formulate hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 2: Religious beliefs influence the intention to leave a bequest.

2.1.3. Inheritance

People save money in order to finance their expenses during their retirement years and whatever remains when they die is bequeathed automatically to their heirs Davies (Citation1981) and DeBoer and Hoang (Citation2017) found that inheritance recipients have a higher probability to leave a bequest relative to households that had not received an inheritance. The inheritances already received or expected to be received may be an important transmission mechanism underlying the bequest motive. Family tradition also affects bequest decision. Those with a family tradition of leaving bequest via inheritances have a positive impact on bequeathing their assets to future generations (Stark & Nicinska, Citation2015).

Hypothesis 3: Inheritance influences the intention to leave a bequest.

2.1.4. Social norms

Social information can change apparent descriptive social norms, which in turn changes donation behavior (Croson, Handy, & Shang, Citation2009). Shang, Reed, and Croson (Citation2008) found that bequests are mostly made by people who have a high collective-identity esteem. Collective customary beliefs and values of a society may shape an individual’s personal norms and in turn, influence economic decision making. Social reputation is considered an important motivation for charitable giving, particularly among those in the higher social strata and are wealthier (Schervish, Citation2005). (Bekkers & Wiepking, Citation2007) found that people always prefer to make structured donations to organizations they trust because they want their money to be spent effectively.

Hypothesis 4: Social norms influence the intention to leave a bequest

2.1.5. Altruism

Altruism is the most prominent motive driving bequests according to the economic theories of intergenerational transfers. Becker and Barro (Citation1986) and Wilhelm (Citation1996) find that bequeathing can be attributed to altruistic traits in people and is independent of the children providing care and financial backing during old age. The motivation to help others and donate to charity is characteristic of people with strong altruistic attitudes (Wiepking et al., Citation2012). Interestingly, Stark and Nicinska (Citation2015) found that bequeathing behavior is more common in people who have not received the inheritance as they do not want their children to go through a similar experience, displaying altruistic attributes of their personality. Consistent with this theory, we formulate hypothesis 5:

Hypothesis 5: Altruistic attitudes influence the intention to leave a bequest.

3. Methodology and research process

3.1. Survey

The survey was carried out in two stages. In the first phase, data were collected using a non-probability sampling survey technique among Indians of differing demographics including gender, age, educational and social backgrounds during 2016–17. Considering the sensitivity of the topic, the survey instrument was administered to only those who were willing to take the survey. Thus, it was difficult to calculate a response rate based on the number of people who refused to respond. Two hundred and sixty-three individuals responded to the survey but only 222 responses could be used for the analysis after accommodating the missing values.

The mean and median age of the respondents is 46.5 and 48 years, respectively.

3.2. Development of the survey instrument

For its explanatory superiority in the Indian context, the final instrument used in this study was predominantly that from Wiepking et al. (Citation2012). The questions were organized into several groups like altruistic attitudes, religious values, financial perception and social reputation were applied in the Australian setting by the researchers. “Social reputation” was renamed “social norms” for its appropriateness in nomenclature in the Indian setting. All the attributes were measured on the 5-point Likert scale. Socio-demographic questions were included and the survey instrument was vetted through an expert review process. Cronbach’s alpha value obtained in a pilot study was 0.63.

3.3. Empirical analysis

The data obtained from the survey were analyzed using bivariate analysis. The sample consisted of 48% men and 52% women. Of the total 222 respondents, around half of the married respondents were seen to have an intention of leaving a bequest. Interestingly, around 75% of those who were single also showed an intention to make a bequest. About 76 percent of the respondents who had a bequest intention had not received an inheritance from their ancestors.

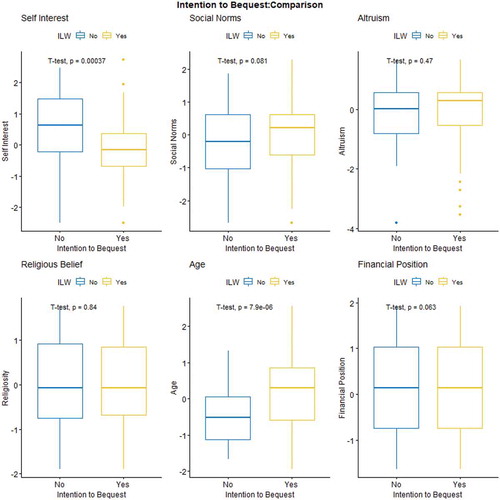

Table shows the standardized summary statistics for all the continuous variables, grouped by the dependent variable, intention to make a bequest. The mean self-interest for households that do not intend to make a bequest is 0.54, which is 0.71 standard deviation units higher than those households that intend to bequeath their wealth. Interestingly, the mean religiosity of households that are not planning to make a bequest is 0.04 standard deviation units higher than the households that are planning to make a bequest. Further, the mean social norm for households willing to leave a bequest is 0.32 units higher than those people who are not willing to bequeath.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics (Number of Observations = 222)

Table shows the correlations between the continuous variables. Social norms and religiosity have a significant positive correlation of 0.4. There is a significant positive correlation between religiosity and self-interest at the 5% level. Further, none of the variables are found to have a significant negative relationship.

Table 2. Correlations between Continuous Variables

3.3.1. Bivariate and interaction analysis

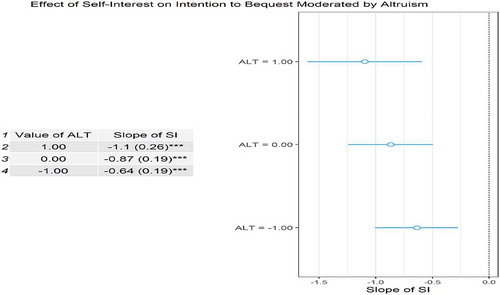

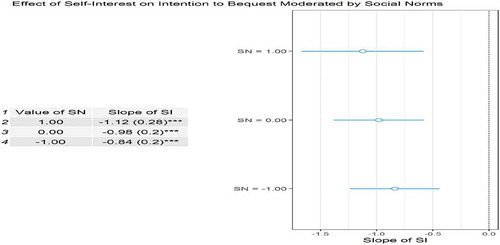

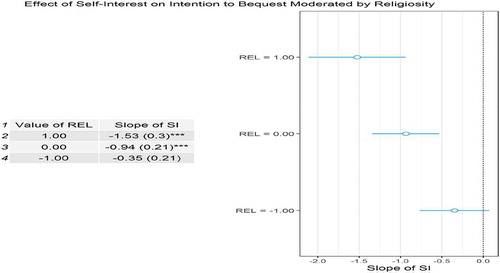

The selfish life-cycle model of Modigliani and Brumberg (1953x) assumes that an average household is selfish and derives utility only from its own consumption. Our bivariate analysis of how self-interest affects the intention to bequest shows that as self-interest increases by one standard deviation unit, the probability of leaving a bequest decreases by almost half that of not leaving a bequest (odds = 0.49) (Refer Table ). The result is significant at 1% level and is consistent with the life-cycle hypothesis of Modigliani and Brumberg (1953). Further, we also explored the interaction effect of altruism on the relationship between self-interest and intention to make a bequest. The interaction effect shown in Figure indicates that altruism negatively amplifies the relationship between self-interest and the intention to bequest. More specifically, as self-interest increases by one unit, the probability of bequeathing is one-third of not bequeathing. The result is significant at the 5% level. Similarly, Figure shows the interaction effect of religiosity on the relationship between self-interest and the bequest intention. The results, significant at the 1% level, indicate a sharper negative amplifying effect on the probability to leave a bequest than the effect of altruism on self-interest. For a one-unit increase in self-interest, the odds of leaving a bequest to the odds of not leaving a bequest is equal to 0.21.

Table 3. Bivariate Analysis

A bivariate analysis of the effect of social norms on intention to bequest suggests that a one-unit increase in social norms significantly increases the odds of leaving a bequest by a factor of 1.37. We also found that for a household with average self-interest, a one-unit increase in social norms doubles the odds of leaving a bequest. Similarly, for households with average altruism and religiosity, a one-unit increase in social norms increases the odds by a factor 1.35 and 1.52, respectively.

The interaction analysis of self-interest and altruism as shown in Figure suggests that an increase in altruism amplifies the negative relationship between self-interest and intention to bequest. To elaborate further, our findings do not support the common theory that Indian households with high levels of altruism have a higher intention to bequest wealth. There may be many households that continue to imbibe the Indian culture of philanthropy and leave their wealth to help the less-fortunate outside the family. Another plausible reason for charitable bequests outside the family is the expectation of social recognition, which is unlikely with a bequest to one’s children who might consider the bequest as an entitlement.

Similar to the moderating effect of altruism, we find evidence that social norms negatively amplify the relationship between self-interest and the intention to leave wealth. Prosociality of households on an average is an important positive predictor of bequeathing. However, our results suggest that for households with higher levels of social norms, as self-interest increases probability to bequest decreases faster than for those with lower levels of prosociality. It could be because of the peculiar need of the families with the higher social status to leave a reputational legacy behind because of cultural norms prevailing in the country.

Religiosity is also seen to negatively amplify the relationship between self-interest and intention to bequest. More specifically, as in Figure we found that among Indian households that are highly religiosity, self-interest increases the probability to bequeath decreases. This is consistent with the philanthropic literature and research on religion and inter vivo transfer (Lyons & Nivison-Smith, Citation2006) which suggests that greater religious involvement is positively correlated with charitable giving to religious and nonreligious charitable organizations (structured charitable donations). India is no exception for its deep rooted philanthropic tradition, characteristics of which is still displayed largely motivated by religion.

With an objective to understand the factors that help in discriminating between the households with an intention to bequeath and those with no such intention, we conduct a series of t-tests. The results shown in Figure indicate that self-interest of households with an intention to bequeath is significantly lower than those who do not have such an intention. Social norms of households with an intention to leave a bequest is found to be higher than the rest. The result is significant at the 10% level. In contrast to Horioka (Citation2014), we find that the level of altruism is not significantly different for households with and without an intention to bequeath. Finally, the age of households with an intention to bequeath is significantly higher than those with no such intention.

4. Policy implications

In this paper, we examine the relationship between household preferences and bequest intentions in an emerging market context, India. We find that, among the factors related to household preferences, self-interest has a negative association and social norms has a positive association with the intention to bequest. Interestingly, altruism does not have a significant effect on the bequest intentions of Indian households. Further, we find that self-interest, altruism, social norms negatively amplifies the relationship between self-interest and bequest intention. The results would be useful for economists modelling household preferences, particularly in an emerging market context with relatively less matured social security systems and policies.

Economic and cultural contexts play a critical role in determining the impact of government policies on household behavior. Traditionally, in contrast to the developed economies, the savings behavior of Indian households have shown a bias towards physical assets such as real estate and gold. The sub-optimal savings behavior of the households poses several challenges to policy makers.

For example, in 1985, government abolished the inheritance tax, levied against the value of an asset during the time of its inheritance. According to the RBI’s Household Finance Committee Report (2017), 84% percentage of the assets of Indian households is in the form of physical assets comprising mostly property and gold. Reinstatement of inheritance taxes for physical assets would stimulate the households, particularly the selfish households, to sell the less productive physical assets and increase their consumption spending. This would also help alleviate wealth inequalities prevailing in Indian society.

Further, pay-as-you-go is a system in which a person or organization pays for the costs of something when they occur rather than before or afterwards. Introduction of an effective pay- as- you –go pension systems would enable selfish households to spend more during their pre-retirement period, as they would be less concerned about the post-retirement life. This would improve their overall living standards.

Finally, the reverse mortgage market in India is in the nascent stage of its development. Conducive policies, exploiting the findings of our study, could potentially help in unlocking the substantial wealth trapped in the residential properties using innovative reverse mortgage products.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Smitha Nair

Smitha Nair is currently working as Assistant Professor with the Department of Management of Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, India. Her research interest is in the area of financial economics in emerging markets, with a particular focus on India.

References

- Becker, G. S., & Barro, R. J. (1986). Altruism and the economic theory of fertility. Population and Development Review, 12, 69–11. doi:10.2307/2807893

- Bekkers, R., & Wiepking, P. (2007, October). Understanding philanthropy: A review of 50 years of theories and research. In 35th Annual Conference of the Association for Research on Nonprofit and Voluntary Action, Chicago. doi:10.1094/PDIS-91-4-0467B

- Bekkers, R., & Wiepking, P. (2011). Who gives? A literature review of predictors of charitable giving part one: Religion, education, age and socialisation. Voluntary Sector Review, 2(3), 337–365.

- Bernheim, B. D., Lemke, R. J., & Scholz, J. K. (2004). Do estate and gift taxes affect the timing of private transfers? Journal of Public Economics, 88(12), 2617–2634.

- Bernheim, B. D., Shleifer, A., & Summers, L. H. (1985). The strategic bequest motive. Journal of Political Economy, 93(6), 1045–1076. doi:10.1086/261351

- Croson, R., Handy, F., & Shang, J. (2009). Keeping up with the Joneses: The relationship of perceived descriptive social norms, social information, and charitable giving. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 19(4), 467–489. doi:10.1002/nml.v19:4

- Davies, J. B. (1981). Uncertain lifetime, consumption, and dissaving in retirement. Journal of Political Economy, 89(3), 561–577.

- DeBoer, D. R., & Hoang, E. C. (2017). Inheritances and Bequest Planning: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 38(1), 45–56. doi:10.1007/s10834-016-9509-0

- Diamond, P. A., & Hausman, J. A. (1984). Individual retirement and savings behavior. Journal of Public Economics, 23(1–2), 81–114.

- Horioka, C. Y. (2014). Are Americans and Indians more altruistic than the Japanese and Chinese? Evidence from a new international survey of bequest plans. Review of Economics of the Household, 12(3), 411–437. doi:10.1007/s11150-014-9252-y

- Hurd, M. D. (1990). Research on the elderly: Economic status, retirement, and consumption and saving. Journal of Economic Literature, 28(2), 565–637.

- Joulfaian, D. (2004). Gift taxes and lifetime transfers: Time series evidence. Journal of Public Economics, 88(9–10), 1917–1929.

- Kotlikoff, L. J., & Spivak, A. (1981). The family as an incomplete annuities market. Journal of Political Economy, 89(2), 372–391. doi:10.1086/260970

- Kotlikoff, L. J., & Summers, L. H. (1981). The role of intergenerational transfers in aggregate capital accumulation. Journal of Political Economy, 89(4), 706–732.

- Kou, X., Han, H., & Frederick, H. (2009). Gender differences in giving motivations for bequest donors and non-donors. The Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University. Retrieved from https://archives.iupui.edu/bitstream/handle/2450/7699/2009_afp_charitablebequestsgenderdifferencesgivingmotivations.pdf?sequence=1

- Lee, Y. J., & Xiao, Z. (1998). Children's support for elderly parents in urban and rural China: Results from a national survey. Journal of Cross-cultural Gerontology, 13(1), 39–62.

- Leopold, T., & Raab, M. (2011). Short‐term reciprocity in late parent‐child relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73(1), 105–119.

- Lyons, M., & Nivison-Smith, I. (2006). Religion and Giving in Australia. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 41(4), 419–436. doi:10.1002/j.1839-4655.2006.tb00997.x

- Menchik, P. L., & David, M. (1983). Income distribution, lifetime savings, and bequests. The American Economic Review, 73(4), 672–690.

- Modigliani, F., & Brumberg, R. (1954). Utility analysis and the consumption function: An interpretation of cross section data. In K. K. Kurihara (Ed.), Post keynesian economics (pp. 388–436). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Nair, S., Amrutha, S., Gopikumar, V., & Sandhya, G. (2017). Religious affiliation and bequest behavior. Purshartha, 10(2), 36-45.

- Ong, R. (2008). Unlocking housing equity through reverse mortgages: The case of elderly homeowners in Australia. European Journal of Housing Policy, 8(1), 61–79.

- Schervish, P. G. (2005). Major donors, major motives: The people and purposes behind major gifts. New Directions for Philanthropic Fundraising, (2005(47), 59–87. doi:10.1002/pf.95

- Shan, H. (2011). Reversing the trend: The recent expansion of the reverse mortgage market. Real Estate Economics, 39(4), 743–768.

- Shang, J., Reed, A., & Croson, R. (2008). Identity congruency effects on donations. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(3), 351–361. doi:10.1509/jmkr.45.3.351

- Stark, O., & Nicinska, A. (2015). How inheriting affects bequest plans. Economica, 82(s1), 1126–1152. doi:10.1111/ecca.12164

- Wiepking, P., Scaife, W., & McDonald, K. (2012). Motives and barriers to bequest giving. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 11(1), 56–66.

- Wilhelm, M. O. (1996). Bequest behavior and the effect of heirs’ earnings: Testing the altruistic model of bequests. The American Economic Review, 86(4), 874–892. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2118309