?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this paper is to examine alternative reporting formats of comprehensive income (CI) information and measures the extent to which losses are being accumulated in other comprehensive income (OCI) in the specific context of two major FASB updates: Summary of Financial Accounting Standard (SFAS) No. 130 and Accounting Standard Update (ASU) 2011–05. Design/methodology/approach: This paper investigates alternative reporting formats of CI information and its effect on Earnings Per Share (EPS) of 100 top US firms over the 1997–1999 period. The pattern of Other Comprehensive Income (OCI) is then examined using a sub-sample of ten companies with 31 December year ends over the 1995–2014 period. Findings: The results indicate that several firms show OCI items as part of shareholders’ equity. On average, the difference between CI and net income is significant for the majority of firms, fluctuating by up to 15% (in absolute terms) over three-years. The negative effect on EPS is significant. For sub-sample firms, OCI is predominantly negative (i.e., is reported as a loss). Research limitations/implications: The effect of the above findings is that reported earnings generally provide an overly optimistic picture of book values. Conservative book values are shown to be a more sufficient statistic for returns than earnings for investors.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The financial statement of a company is used by external users as the main source of information to take financially informed decisions. The quality of financial information particularly earnings amount is important for creditors, investors that enable the process of the formation of the company’s profitability and better decision making. Researchers raised the issue of defining which income items are included in earnings and which are included in OCI. Standard setters have been unsuccessful at mitigating the use of OCI and recycling in the current conceptual framework, which affects the consistency, transparency, and quality of earnings. The failure of income to be reported in comprehensive income hides the impact of losses on the market which may be interesting for stakeholders. The impact of this is that reported earnings generally provide an over-optimistic picture of book value. Standard setters and the conceptual framework need to examine the flexibility of FASB standards to determine if such flexibility does address the issue of earnings quality.

1. Introduction

More than a decade ago, the Financial Accounting Standard Board (FASB) released the Statement of Financial Accounting Standard (SFAS) 130, relating to the reporting of CI Topic 220, “Comprehensive Income (CI)”. CI includes all shareholders’ equity changes during a financial period except those events or transactions resulting from investments or distributions to owners.

The FASB introduced the concept of other comprehensive income (OCI) in SFAS 130 in 1997 to facilitate improved reflections of certain revenue and expenses items, gains and losses of CI that are not included in net income under US GAAP. CI is considered a much broader concept than net income; it includes net income as well as OCI. Net income (NI) is listed at the bottom of the income statement, whereas OCI items are based on unrealised gains and losses. Some OCI items bypass the income statement and moved directly through shareholders’ equity as a distinct component. Those firms with no OCI items in a financial period do have to report CI (FASB, Citation1997).

The FASB tried to balance the requirements of both preparers and users of financial statements in SFAS 130, which resulted in a significant debate about the best presentation of CI, OCI, and NI. Some researchers preferred to separate OCI items from NI for various reasons. For example, OCI is usually not related to core business activities and is based on unrealised gains and losses and increased volatility in earnings. In contrast, other researchers argued that separating the effects of OCI items decreases the focus of stakeholders on transactions or events that might substantially affect a firm’s equity.

In June 2011, the FASB released Accounting Standard Update (ASU) 2011–05 Comprehensive Income (Topic 220) and revised the presentation rules of CI. In doing so, the FASB attempted to achieve two goals: first, by presenting OCI items more conspicuously, it has aimed to help financial statement users to evaluate the effect of OCI items more carefully. Second, this update has provided a basis for the upcoming implementation of accounting rules regarding the presentation of CI.

The motivation for this paper is to improve our understanding of the idea of CI disclosure and earnings per share (EPS) in the specific context of the FASB updates. The focus is on the Summary of Financial Accounting Standard (SFAS) No. 130 and Accounting Standard Update (ASU) 2011–05.

This paper contributes to the literature by evaluating why the accumulative Other why the accumulated Other Losses are increasing over time and may reverse in more than two years.This has implications to the standard-setting: the compliance or non-compliance by companies indicates large losses reported in OCI and not reversing out, in contravention of the 2011 standards. Standard setters and the conceptual framework need to examine the flexibility of FASB standards to determine if such flexibility does address the issue of earnings quality. Prior researchers claimed that accruals have a finite adjustment of one or two years (Burgstahler, Jiambalvo, & Shevlin, Citation2002; Dechow & Ge, Citation2006; Dechow, Ge, Larson, & Sloan, Citation2011; Dechow, Ge, & Schrand, Citation2010; Fairfield, Sweeney, & Yohn, Citation1996). Linsmeier, Gribble, Jennings, and Lang (Citation1997) finds that OCI gains and losses are transitory and reverse regularly. This study also finds support for the propositions that reversals take longer (Jones & Smith, Citation2011), that gains, and losses may not necessarily be transitory, and that certain OCI items recur over time (Cready, Lopez, & Sisneros, Citation2010; Elliott & Hanna, Citation1996; Francis, Hanna, & Vincent, Citation1996).

This paper also contributes to the literature by evaluating why after SFAS 130, majority of companies presented OCI items as part of their shareholder’s equity instead of two other options provided (1) in a single comprehensive income statement that includes both net income and all other comprehensive income statement items; (2) in two separate statements that include a statement of earnings (income statement) and comprehensive income statement. This study finds support for the propositions that reporting of OCI items in shareholders’ equity create several issues, includes potentially reducing the informativeness and predictive power of accounting earnings (Barker, Citation2004); decrease transparency and visibility (Linsmeier et al., Citation1997); decrease information usefulness (Veltri & Ferraro, Citation2018). This suggests that if investors consider OCI while evaluating a company’s performance, they may draw a different conclusion than they would if they based their assessment on net income alone.

This has also an implication that the failure of income to be reported in comprehensive income hides the impact of losses on the market. The impact of this is that reported earnings generally provide an over-optimistic picture of book value.

This paper contributes to the literature by investigating the CI disclosure and EPS in the specific context of the two major FASB updates (SFAS 130 in 1997 and ASU in 2011) which is different from prior researches. Most of the prior researchers compared the value relevance, predictive value, and persistence of other comprehensive income and special items.

This paper finds that most companies report CI as a part of their stakeholders’ equity disclosures. On average, the difference between CI and net income is significant for the majority of the companies, fluctuating by as much as 15% (in absolute terms) in the three years.

From 1997–1999, the number of sample companies negatively affected by OCI is substantially higher than the number positively affected. Therefore, the effect on earnings per share (EPS) is significant. EPS is considered a key financial measure of a firm’s performance. If analysts ignored OCI items while evaluating a firm’s performance, basing their conclusions on net income alone, they may reach to different conclusions. This paper also finds that losses reported in OCI of most of the sample firms are economically significant after ASU 2011–05 (FASB, Citation2011).

After a brief literature review in Section 2, Section 3 outlines the theory, method, and data used in the paper. Section 4 provides some relevant summary statistics regarding comprehensive income disclosure and Section 5 presents information about the accumulation of losses in Other Comprehensive Income. Section 6 concludes.

2. Relevant theories

The study focuses on the Comprehensive Income (CI) statement that enables the creditors and investors to assess the process of the formation of the firm’s profitability. The theory underlying this study is based on FASB regulations and mandatory presentation requirements of earnings. The FASB released mandatory OCI presentation requirements in 1997 and again in 2011.

In 1997, FASB issued Statement of Financial Accounting Standard (SFAS) No. 130 and allowed entities to show OCI items according to one of three listed options: (1) in a single comprehensive income statement that includes both net income and all other comprehensive statement items; (2) in two separate statements that include a statement of earnings (income statement) and comprehensive income statement; (3) in changes in the shareholders’ equity statement (Chambers, Linsmeier, Shakespeare, & Sougiannis, Citation2007; Kim, Citation2016).

In June 2011, FASB released Accounting Standard Update (ASU) 2011–05 after considering the concerns raised by several stakeholders (Kim, Citation2016). After this update, entities were no longer permitted to show their OCI items in the shareholders’ equity statement. Entities could report their OCI items in either a single statement or in two distinct statements, comprising an income statement and comprehensive income statement (Eaton, Easterday, & Rhodes, Citation2013; Kim, Citation2016).

The FASB also amended the definitions of the accounting concepts of Comprehensive Income, Earnings and Other Comprehensive Income (OCI) and the relations that hold between these accounting variables to make the process of the formation of the firm’s profitability more transparent for investors. CI signifies all changes in shareholders’ equity except transactions with owners. CI is derived from the concept of an all-inclusive income statement which refers to all changes in assets and liabilities other than transactions with owners (Du, Stevens, & Mcenroe, Citation2015). It includes all items of Net Income (NI) and other comprehensive income (OCI).

The main identity assumed is that period closing Book Value, , is related to period opening Book Value,

, Net Income in period t,

, Other Comprehensive Income in period t,

, Dividends in period t,

, and transactions with owners in period t,

, by the identity:

Earnings (NI) is that part of income that is reported in the profit and loss account, while OCI is reported elsewhere in Equity but is not part of what is currently referred to in accounting standards as ‘transactions with owners. “Retained earnings” is defined as the accumulated sum of and

(with

having negative values) from the first period, 0, onwards,

Consequently, Other Comprehensive Income, in theory, is related to the change in Retained Earnings by the formula:

The FASB notifies that although CI amount is a useful number, the disclosure of OCI information particularly items bypassing the income statement are needed in order to better understanding of an entity’s performance and its future cash flows (Shi, Wang, & Zhou, Citation2017).

3. Prior literature

3.1. Overview of other comprehensive income presentation

Before the release of SFAS No. 130 (FASB, 1997), companies were required to report three items in the balance sheet as distinct items of shareholders’ equity, bypassing the income statement. These OCI items included currency transaction adjustments, additional pension liability adjustments, and unrealised gains and losses on marketable securities. The users of financial statements raised a concern regarding the misuse of financial reporting when these items bypass the income statement (Brauchle & Reither, Citation1997). They also argued that this format creates a lack of consistency in the presentation of OCI. Consequently, FASB released SFAS No. 130 for the improvement of OCI presentation (FASB, 1997), effective from the financial year starting after 15 December 1997.

Under SFAS No. 130, FASB (1997) allowed entities to show OCI items according to one of three listed options: (1) in a single comprehensive income statement that includes both net income and all other comprehensive statement items; (2) in two separate statements that include a statement of earnings (income statement) and comprehensive income statement; (3) in changes in the shareholders’ equity statement (Chambers et al., Citation2007; Kim, Citation2016).

Although three options were given for presenting OCI items, FASB encouraged entities to present their OCI items using either the first or second options. FASB (1997) believed that the purpose of transparent reporting and high quality of financial statements could be achieved by reporting OCI items in one of these two options (FASB, 1997).

Despite this FASB encouragement, most entities started reporting OCI using the third option: in the statement of change in shareholders’ equity (Bamber, Jiang, Petroni, & Wang, Citation2010; Bhamornsiri & Wiggins, Citation2001; Chambers et al., Citation2007; Jordan & Clark, Citation2014; Pandit & Phillips, Citation2004).

Researchers argued that reporting of OCI items in shareholders’ equity created several issues, including potentially reducing the informativeness and the predictive power of accounting earnings (Barker, Citation2004); decreasing transparency and visibility (Linsmeier et al., Citation1997); impairing the quality of earnings and decreasing the usefulness of earnings information (Biddle & Choi, Citation2006); increasing errors in accounting-based valuation models (Isidro, O’Hanlon, & Young, Citation2004, Citation2006); and increasing the cross-country differences in the applicability of such models.

FASB released ASU 2011–05 in June 2011 after considering the concerns raised by several stakeholders (Kim, Citation2016). After this update, entities were no longer permitted to show their OCI items in the shareholders’ equity statement. Entities could report their OCI items in either a single statement or in two distinct statements, comprising an income statement and comprehensive income statement (Eaton et al., Citation2013; Kim, Citation2016).

FASB also added a disclosure requirement, whereby entities were required to display reclassification adjustments from comprehensive income to net income on the face of the financial reports (Eaton et al., Citation2013; Henry, Citation2011).

Proponents believe that FASB update 2011–05 (FASB, 2011) improved the presentation of OCI items by excluding the third option and those reclassifications adjustments to make clear to financial statement users’ certain items that are already included in a previous period’s comprehensive income (Casabona & Coville, Citation2014; Henry, Citation2011). Researchers argued that FASB update 2011–05 enhanced the transparency in disclosing CI and changes in OCI and increased the importance of OCI items (Schaberl & Victoravich, Citation2015).

However, researchers raised various other standard-setting issues regarding the current reporting requirements of comprehensive income, the most prominent of which may be the issue of defining which income items are included in earnings and which are included in OCI (Black, Citation2016; Linsmeier et al., Citation1997; Nishikawa et al., Citation2016; Rees & Shane, Citation2012). Standard setters have been unsuccessful at mitigating the use of OCI and recycling in the current conceptual framework, which affects the consistency, transparency, and quality of earnings (Nishikawa et al., 2016). This FASB update only affected the reporting location of OCI (Eaton et al., Citation2013; Jordan & Clark, Citation2014; Lin, Martinez, Wang, & Yang, Citation2018 ; Rees & Shane, Citation2012; Schaberl & Victoravich, Citation2015); the single continuous statement permitted in FASB 2011–05 may create confusion among financial statement users (Kim, Citation2016; Streaser, Sun, Zaldivar, & Zhang, Citation2014); Value relevance of OCI decreases for firms that changed the reporting location of OCI after the implementation of ASU 2011–05 (Lin, Martinez, Wang, & Yang, Citation2018).

Stakeholders also raised many additional concerns about the requirement for presentation of reclassification adjustments out of accumulated OCI at the time of implementation of update 2011–05 (FASB, 2011) and argued that earnings quality has not met the objectives of the update. The relevant Broad Consideration (BC) released in ASU, 2011–12 are outlined below.

Eaton et al. (Citation2013) argued that presentation format should not matter if the market is efficient and investors are rational. He further argued that public information shown in any format is entirely incorporated into a company’s stock price in an efficient market.

As a result of conflicting arguments on update 2011–05, FASB made another attempt to improve OCI presentation and issued Accounting Standard Update (ASU) 2013–02 in February 2013 (FASB, Citation2013). ASU 2013–02 aimed to enhance the transparency of OCI changes and reclassified the adjustment of OCI components.

4. Methodology

The objective of this paper is to analyse two major FASB updates (SFAS 130 and ASU 2011–05) relating to Comprehensive Income Disclosure. The method is divided into two parts.

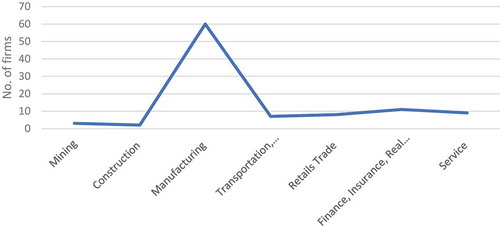

First, this study investigates different reporting formats of OCI items following the implementation of SFAS 130 and examines its effect on EPS. For this purpose, 100 top US companies are selected from seven main sectors comprised of mining, construction, manufacturing, transportations, retails trade, finance, and service.

Second, this paper examines the pattern and reporting format of OCI using a sub-sample of ten companies with 31 December year ends over the 1995–2014 period. It is expected that OCI should appear as a stationary time series around zero and that AOCI should behave as a time series, integrated of order 1 (I (1)), and returning to zero after some finite time interval. If this is not observed, this suggests that the failure of income to be reported in comprehensive income hides the impact of losses on market value.

4.1. Definition of variables and source of data

This subsection describes the variables used in the econometric models.

4.1.1. Earnings (NI)

Earnings are Compustat net income (NI), a firm’s profit disclosed in its income statement and not included in other comprehensive income.

4.1.2. Other comprehensive income (OCI)

This is defined by the FASB and other standards, and usually consists of foreign exchange differences arising from translating functional currencies to presentation currencies FASB Statement No. 52, Foreign Currency Translation paragraph 13 (FASB, Citation1981b); FASB Statement No. 115, fair value adjustments, paragraph 16 (FASB, Citation2006); and FASB Statement No. 87, Employers’ Accounting for Pensions, paragraph 37 (FASB, Citation1985b).

4.1.3. Accumulated other comprehensive income (AOCI)

Accumulated other comprehensive income (AOCI) is the cumulative amount of OCI components, reported in each period’s statement of comprehensive income.

4.1.4. Reported book value (B)

Book value is defined as the reported book value of net assets. This is defined in the Compustat annual data field and measured at the end of the relevant period.

The data used in this paper is based on the implementation of two major FASB updates: SFAS, 130 and ASU 2011–05. These updates are relating to the ‘reporting of comprehensive income. Data over the period 1997–1999 is collected from publicly available financial reports. However, a sub-sample US firm’s data over the period 1995–2014 is extracted from the Compustat file.

Data fields used for each model variable are either as directly defined by Compustat or defined in Table .

Table 1. Data definitions

5. Comprehensive income disclosure

Figure displays the industrial division of sample firms; 60% of sample companies are from the manufacturing sector, 35% of companies are from the transportation, retail trade, finance, and service sectors. Only 5% of companies belong to the construction and mining industries.

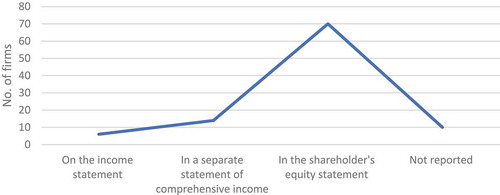

Figure indicates that most sample companies (70) reported CI as a part of the shareholder’s equity statement, of which 10 companies altered the term “shareholder equity” to include the term “comprehensive income”. In another common method of presentation, 14 companies presented information in a distinct CI statement. Only 6 companies displayed CI on the face of the income statement. Of the sample companies, 10 did not disclose of CI. Of these, 4 companies indicated that CI and net income were the same in the reported year. Another 6 companies provided no disclaimers or disclosures.

Ten companies altered the shareholder’s equity statement title to include “comprehensive income”.

Six companies presented no information regarding CI. Four companies declared that CI and net income were the same in the reported year.

Separate disclosure of CI is not specified in the notes of the financial statements of any sample companies. CI is usually referred to in the notes of investments, pensions, and other related areas.

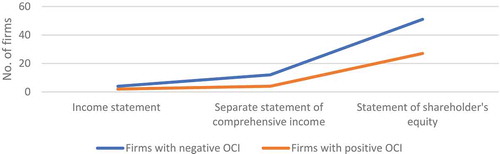

Many companies reported CI in the shareholder’s equity in 1999 irrespective of positive or negative OCI. Figure indicates that 5–7% the companies in both positive and negative OCI groups selected to present CI on the face of the income statement, 15–17% of each group selected to report information in a separate CI statement and 77–79% selected to report CI in the statement of shareholder’s equity. The percentages presented in Figure are consistent with the overall percentage reported in Figure .

Table indicates three main components of OCI as presented by the sample companies from 1997–1999. These OCI components are foreign currency translation, minimum pension liabilities, and unrealised holding gains and losses. Approximately 76–80% of sample companies commonly reported foreign currency translations each year, which is significantly higher than the other two OCI components in monetary terms. Approximately 31–35% presented minimum pension benefit plans and 46–50% reported unrealised gains and losses each year.

Table 2. Analysis of OCI components

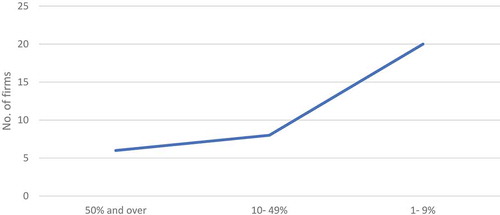

Figure shows that the number of sample companies that were negatively affected by OCI is higher than the number of companies that were positively affected. The average OCI is—$192 million in 1997 but declined to—$45 million in 1999. More careful management is required in reporting of OCI items. The nature of OCI items could make earnings more volatile and lead to different conclusions.

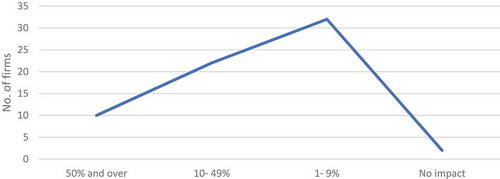

Figures and demonstrate how the use of CI instead of reported net income affects EPS. The EPS of 64 companies would be negatively affected if OCI is included in CI, while there are only 34 sample companies that would be positively affected. If 10% is taken as a material threshold, 32 sample companies were materially impacted by OCI. The effect on earnings per share (EPS) can be explosive; The negative change in EPS of some companies is more than 50% (see Table ).

Table 3. Largest effects of Other Comprehensive Income (OCI)

6. Behaviour of “other comprehensive income”

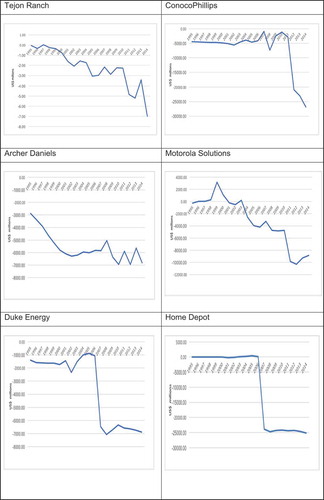

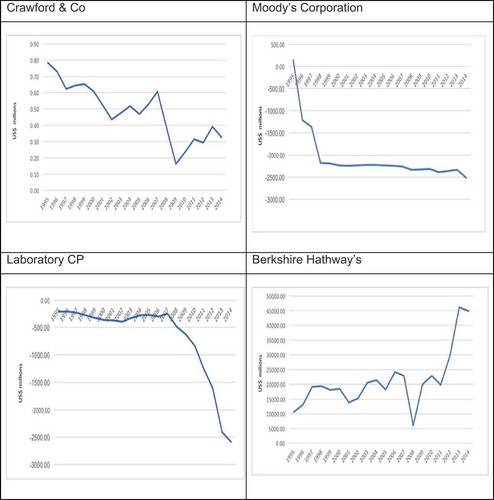

In seeking better to understand the pattern of Other Comprehensive Income over time we have chosen one individual company each from 10 major US Industries. Different industries are subject to different economic factors contributing to the behaviour of the items that are included in Other Comprehensive Income and these, as well as possible accounting policy choices, may explain some of its patterns.

The accumulation of losses in Other Comprehensive Income overtime is common to most of the individual companies. Figure displays AOCI for the 10 individual companies. All the sample companies except Crawford & Co and Berkshire Hathway’s with a strongly increasing negative value over time. This suggests that the failure of income to be reported in comprehensive income hides the impact of losses on market value.

7. Discussion and conclusion

This paper contains evidence that the majority of companies presented CI as part of their shareholders’ equity from 1997–1999. In each year studied, the number of companies that were negatively affected by OCI is substantially higher than the number of companies that were positively affected. Therefore, EPS is affected significantly. If investors consider OCI while evaluating a company’s performance, they may draw a different conclusion than they would if they based their assessment on net income alone. In SFAS 130, the FASB clearly indicated that the broad concept of income plays an important role in upcoming financial decision-making.

This study finds support for the propositions that reporting of OCI items in shareholders’ equity created several issues, including potentially reducing the informativeness and predictive power of accounting earnings (Barker, Citation2004); decreasing transparency and visibility (Linsmeier et al., Citation1997); impairing the quality of earnings and decreasing the usefulness of earnings information (Biddle & Choi, Citation2006); increasing errors in accounting-based valuation models (Isidro et al., Citation2004, Citation2006); and increasing the cross-country differences in the applicability of such models.

This paper contains also evidence that the AOCI of most of the individual companies studied from 1995 to 2014 is becoming increasingly negative over time and now sums across all firms to a very large aggregate amount by 2014. This suggests that the failure of income to be reported in comprehensive income hides the impact of losses on market value. The impact of this is that reported earnings generally provide an over-optimistic picture of book values.

There are several implications. First, the Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income indicates that there is little reversal of the unrealised gains and losses. This has implications for the debates that accruals have a finite adjustment of one or two years (Burgstahler et al., Citation2002; Dechow & Ge, Citation2006; Dechow et al., Citation2011, Citation2010; Fairfield et al., Citation1996); that OCI gains and losses are transitory and reverse regularly (Bamber et al., Citation2010; Barker, Citation2004; Chambers et al., Citation2007; Linsmeier et al., Citation1997; Yen, Hirst, & Hopkins, Citation2007); and that accounting accrual estimates reverse in subsequent periods (Hou, Karolyi, & Kho, Citation2011; Ince & Porter, Citation2006; Novy-Marx, Citation2013). This study also finds support for the propositions that reversals take longer (Jones & Smith, Citation2011), that gains and losses may not necessarily be transitory, and that certain OCI items recur over time (Cready et al., Citation2010; Elliott & Hanna, Citation1996; Francis et al., Citation1996).

This study suggests the standard setters, and the conceptual framework to examine the flexibility of FASB standards to determine if such flexibility does address the issue of earnings quality.

The majority of instances where Other Comprehensive Income can be identified with particular events and sets of transactions appear to be mandated by accounting standards. However, the problem does pertain to Earning’s quality, in the context of the clean surplus principle which may be an interesting topic for future researchers.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Javed Mahmood

Dr. Javed Mahmood is working as a Sessional Academic Staff at Tasmanian School of Business and Economics (TSBE), University of Tasmania, Australia. He has more than eight years of teaching and research experience in total. His areas of research interest are financial reporting, earnings quality, earnings management, and corporate finance. Dr. Mahmood has supervised 4 honors/master students to their successful completion. Further, he is an individual member of the Accounting and Finance Association of Australia and New Zealand (AFAANZ) and Associate Fellow of Higher Education Academy UK.

Irfan Mahmood

Dr. Javed Mahmood is working as a Sessional Academic Staff at Tasmanian School of Business and Economics (TSBE), University of Tasmania, Australia. He has more than eight years of teaching and research experience in total. His areas of research interest are financial reporting, earnings quality, earnings management, and corporate finance. Dr. Mahmood has supervised 4 honors/master students to their successful completion. Further, he is an individual member of the Accounting and Finance Association of Australia and New Zealand (AFAANZ) and Associate Fellow of Higher Education Academy UK.

References

- Bamber, L. S., Jiang, J., Petroni, K. K., & Wang, I. Y. (2010). Comprehensive income: Who’s afraid of performance reporting? The Accounting Review, 85, 97–14. doi:10.2308/accr.2010.85.1.97

- Barker, R. (2004). Reporting financial performance. Accounting Horizons, 18, 157–172. doi:10.2308/acch.2004.18.2.157

- Bhamornsiri, S., & Wiggins, C. (2001). Comprehensive income disclosures. The CPA Journal, 71, 54.

- Biddle, G. C., & Choi, J.-H. (2006). Is comprehensive income useful? Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics, 2, 1–32. doi:10.1016/S1815-5669(10)70015-1

- Black, D. E. (2016). Other comprehensive income: A review and directions for future research. Accounting & Finance, 56, 9–45. doi:10.1111/acfi.12186

- Brauchle, G. J., & Reither, C. L. (1997). SFAS No. 130: Reporting comprehensive income. The CPA Journal, 67, 42.

- Burgstahler, D., Jiambalvo, J., & Shevlin, T. (2002). Do stock prices fully reflect the implications of special items for future earnings? Journal of Accounting Research, 40, 585–612. doi:10.1111/1475-679X.00063

- Casabona, P. A., & Coville, T. (2014). Statement of comprehensive income: New reporting and disclosure requirements. Review of Business, 35, 23–35.

- Chambers, D., Linsmeier, T. J., Shakespeare, C., & Sougiannis, T. (2007). An evaluation of sfas no. 130 comprehensive income disclosures. Review of Accounting Studies, 12, 557–593. doi:10.1007/s11142-007-9043-2

- Cready, W., Lopez, T. J., & Sisneros, C. A. (2010). The persistence and market valuation of recurring nonrecurring items. The Accounting Review, 85, 1577–1615. doi:10.2308/accr.2010.85.5.1577

- Dechow, P., Ge, W., & Schrand, C. (2010). Understanding earnings quality: A review of the proxies, their determinants and their consequences. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50, 344–401. doi:10.1016/j.jacceco.2010.09.001

- Dechow, P. M., & Ge, W. (2006). The persistence of earnings and cash flows and the role of special items: Implications for the accrual anomaly. Review of Accounting Studies, 11, 253–296. doi:10.1007/s11142-006-9004-1

- Dechow, P. M., Ge, W., Larson, C. R., & Sloan, R. G. (2011). Predicting material accounting misstatements. Contemporary Accounting Research, 28, 17–82. doi:10.1111/care.2011.28.issue-1

- Du, N., Stevens, K., & Mcenroe, J. (2015). The effects of comprehensive income on investors’ judgments: An investigation of one-statement vs. Two-statement presentation formats. Accounting Research Journal, 28, 284–299. doi:10.1108/ARJ-11-2013-0083

- Eaton, T. V., Easterday, K. E., & Rhodes, M. R. (2013). The presentation of other comprehensive income. The CPA Journal, 83, 32.

- Elliott, J. A., & Hanna, J. D. (1996). Repeated accounting write-offs and the information content of earnings. Journal of Accounting Research, 34, 135–155. doi:10.2307/2491430

- Fairfield, P. M., Sweeney, R. J., & Yohn, T. L. (1996). Accounting classification and the predictive content of earnings. Accounting Review, 71(3), 337–355.

- Financial Accounting Standard Board (1981b), Financial Statement No. 52, Foreign Currency Translation, paragraph 13.

- Financial Accounting Standard Board (1985b), Financial Statement No. 87, Employers’ Accounting for Pensions, paragraph 37.

- Financial Accounting Standards Board. (1997). Disclosures about segments of an enterprise and related information (statement of financial accounting standards no. 130). Norwalk, CT: Financial Accounting Standards Board.

- Financial Accounting Standard Board (2006). Statement of Financial Accounting Standard (SFAS) No. 158. Employers’ Accounting for Defined Benefit Pension and Other Post retirement Plans.

- Financial Accounting Standards Board. (2011). Comprehensive income (Topic 220), ASU 2011-12, 13-16.

- Financial Accounting Standards Board. (2013). Comprehensive income (Topic 220), ASU 2013-02.

- Francis, J., Hanna, J. D., & Vincent, L. (1996). Causes and effects of discretionary asset write-offs. Journal of Accounting Research, 34, 117–134. doi:10.2307/2491429

- Henry, E. (2011). Presentation of comprehensive income: Another (small) step toward convergence. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance, 23, 85–90. doi:10.1002/jcaf.21726

- Hou, K., Karolyi, G. A., & Kho, B.-C. (2011). What factors drive global stock returns? The Review of Financial Studies, 24, 2527–2574. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhr013

- Huang, H.-W., Lin, S., & Raghunandan, K. (2015). The volatility of other comprehensive income and audit fees. Accounting Horizons, 30(2), 195–210. doi:10.2308/acch-51357

- Ince, O. S., & Porter, R. B. (2006). Individual equity return data from thomson datastream: Handle with care! Journal of Financial Research, 29, 463–479. doi:10.1111/jfir.2006.29.issue-4

- Isidro, H., O’Hanlon, J., & Young, S. (2004). Dirty surplus accounting flows: International evidence. Accounting and Business Research, 34, 383–410. doi:10.1080/00014788.2004.9729979

- Isidro, H., O’Hanlon, J., & Young, S. (2006). Dirty surplus accounting flows and valuation errors. ABACUS, 42, 302–344. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6281.2006.00203.x

- Jones, D. A., & Smith, K. J. (2011). Comparing the value relevance, predictive value, and persistence of other comprehensive income and special items. The Accounting Review, 86, 2047–2073. doi:10.2308/accr-10133

- Jordan, C. E., & Clark, S. J. (2014). Reporting preferences under the comprehensive income standard: Examining its use in practice. The CPA Journal, 84, 34.

- Kim, J. H. (2016). Presentation formats of other comprehensive income after accounting standards update 2011-05. Research in Accounting Regulation, 28, 118–122. doi:10.1016/j.racreg.2016.09.009

- Lin, S., Martinez, D., Wang, C., & Yang, Y.-W. (2018). Is other comprehensive income reported in the income statement more value relevant? The role of financial statement presentation. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 33, 624–646. doi:10.1177/0148558X16670779

- Linsmeier, T. J., Gribble, J., Jennings, R. G., & Lang, M. H. (1997). An issues paper on comprehensive income. Accounting Horizons, 11, 120.

- Nishikawa, I, Kamiya, T, & Kawanishi, Y. (2016). The definitions of net income and comprehensive income and their implications for measurement. Accounting Horizons, 30, 511–516.

- Novy-Marx, R. (2013). The quality dimension of value investing. Rnm. Simon. Rochester. Edu, 1–54.

- Pandit, G. M., & Phillips, J. J. (2004). Comprehensive income: Reporting preferences of public companies. The CPA Journal, 74, 40.

- Rees, L. L., & Shane, P. B. (2012). Academic research and standard-setting: The case of other comprehensive income. Accounting Horizons, 26, 789–815. doi:10.2308/acch-50237

- Schaberl, P. D., & Victoravich, L. M. (2015). Reporting location and the value relevance of accounting information: The case of other comprehensive income. Advances in Accounting, 31, 239–246. doi:10.1016/j.adiac.2015.09.006

- Shi, L., Wang, P., & Zhou, N. (2017). Enhanced disclosure of other comprehensive income and increased usefulness of net income: The implications of accounting standards update 2011–05. Research in Accounting Regulation, 29, 139–144. doi:10.1016/j.racreg.2017.09.005

- Streaser, S., Sun, K. J., Zaldivar, I. P., & Zhang, R. (2014). Summary of the new fasb and iasb revenue recognition standards. Review of Business, 35, 7.

- Veltri, S, & Ferraro, O. (2018). Does other comprehensive income matter in credit-oriented systems? analyzing the italian context. Journal Of International Accounting, Auditing, and Taxation, 30, 18–31.

- Yen, A. C., Hirst, D. E., & Hopkins, P. E. (2007). A content analysis of the comprehensive income exposure draft comment letters. Research in Accounting Regulation, 19, 53–79. doi:10.1016/S1052-0457(06)19003-7