?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

We assess the role of psychological and social factors in the decision-making of investors mediated by risk perception. We use a questionnaire survey to collect data from 470 individuals who have invested in firms listed at Pakistan Stock Exchange. We use confirmatory factor analysis to refine the instrument and structural equation model for hypothesis testing. We find that psychological and social factors play a significant role in investors’ decision-making. Specifically, anger, fear and a positive mood positively affect investors’ decision-making whereas stress, social interaction and herding produce negative effects. Furthermore, risk perception plays a mediating role between psychological factors, social factors and the investment decision.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Behavioral finance is inspired by the assumptions of traditional financial theory that claims people behave in a rational way. There are many cases where feelings, emotions, fears and other psychological factors influence the judgments and decision-making of investors and induce them to behave in inconsistent or irrational ways. Behavioral finance explains the psychological and social factors which may influence the investors’ decision. Investors in stock markets do not act rationally all the time because they are influenced by a large number of behavioral factors and their personal biases. If investors are not aware to deal with psychological and social factors which may lead to irrational decisions while investment. Therefore, understanding of behavioral factors like anger, fear and positive mood help the investors to make better decisions. Furthermore, social interaction and herding also influence the financial decision making of individual investors.

1. Introduction

Decision making on financial matters is considered a complicated task (De Bondt, Muradoglu, Shefrin, & Staikouras, Citation2008). Financial decision-making for investors is complex because they have to deal with risks, alternatives, uncertainty and dynamic environments (Lucey & Dowling, Citation2005). Financial decisions can impact investors’ future and overall life experiences. It is believed that decision-making by stock market investors cannot be based solely on the size of their individual financial resources. Investors’ psychology is seen to be affected by the news, market variations and personal factors (Cornell, Citation2013; Grable & Roszkowski, Citation2008).

Traditional finance theory suggests that investors are rational and behave rationally when making their investment decisions (Markowitz, Citation1952; Sharpe, Citation1964). This means that investors always make choices that fully support their ultimate personal benefit. Furthermore, investors focus on the risk associated with specific security when making their investment decisions (Shefrin, Citation2008; Yudkowsky, Citation2008). Behavioral finance theory challenges traditional finance theory by suggesting that investors do not exhibit rational behaviour (Simon, Citation1955). Further, prospect theory asserts the cognition and psychology behaviours of investors lead them to prefer certain gains and sometimes make irrational decisions instead of optimal decisions (Kahneman & Tversky, Citation1979). There are times when they make decisions which are not in their favour or to their personal benefit, and they sustain losses (Kubilay & Bayrakdaroglu, Citation2016).

In the literature, behavioral factors are considered to have an important affect on investors’ decisions. The investment decision is grounded on the investors’ past performance, abilities to predict or forecast market trends, and technical analysis of the financial securities (Bhavani & Shetty, Citation2017; Mayfield, Perdue, & Wooten, Citation2008). Thus, it is important to identify the major factors which significantly influence individual investor’s decision-making. Behavioral finance is an area that is gaining importance in studies of financial decision-making processes.

Human psychology forms the basis for human needs, objectives, motives, and highlights the extensive human errors occur as a result of perceptual biases, overconfidence, emotions, and heuristics. These biases have certain influences on individual investors’ decision-making (Slovic, Finucane, Peters, & MacGregor, Citation2002). Psychological and social factors influence the normal procedures of decision-making.

Psychological researchers emphases that humans experience different emotions at different times, they can think, learn, take action, manage communications and information to perform daily tasks (Ianole, Citation2011). Behavioral finance theory mixes the concepts and theories of finance with personal behavioral and psychological theories of individuals and investors (Chira, Adams, & Thornton, Citation2008). Psychological factors are known to affect the decisions making process of institutional investors, financial analysts, stock exchange brokers, portfolio managers, options and futures traders, plan sponsors, financial commentators in media, currency exchange brokers and financial securities’ traders (Shefrin, Citation2006). Behavioral finance gives new dimensions to study the mental attitude, mindset, and approaches of investors while making financial decisions.

Due to the lack of awareness of practical applications of behavioral finance, investors may face many problems while being involved in trading activities in their efforts to understand market trends and to make fruitful decisions. There is a need for research that identifies and establishes the critical factors influencing stock exchange investors’ choices and ultimate decision-making (Azam & Kumar, Citation2011). A study by Zahera and Bansal (Citation2018) identifies several common biases involved in investment decision-making and found that psychological biases have a considerable impact on the investor’s financial decision making. Therefore, this study attempts to answer the questions i.e. what is the impact of psychological and social factors on investment decisions and risk perception of individual investors? Furthermore, how the risk perception mediates between psychological, social factors and investment decisions of individual investors?

Our study tests some behavioral biases and their influences on investment decision making, using data gathered from individual investors operating on the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX). In comparison to the global stock market trading practices, Pakistan’s stock market is immature (Sulaiman et al., Citation2016). Individual investors in developing countries are influenced by negative emotions which lead to make misjudgments in risk perception and decision making. Our study helps the investors to understand that some factors can utilize prolifically to improve investment decisions. This study investigates the behavioural and social influence on investment decision-making in Pakistan.

This study is important for the individual investors in the stock markets of developing countries like Pakistan because markets of such countries are not efficient and influenced by numerous factors. Economic stability and political processes are major factors to influence financial markets, but, individual investors’ perceptions and reactions also play a crucial part (Boda & Sunitha, Citation2018). Individual investors in stock markets are less familiar with personal bias and their role in different market sentiments to make better decisions. Investors do not utilize their personal factors to predict the market and most of the time become victims of unexpected trends. It is evident that individual investors suffer losses in Pakistan stock exchange as they do not make the right decisions whether the market showing a bullish trend. This study is also important for individual investors investing in unpredictable and immature stock markets where individual investors experience more negative emotions.

Our study identifies the effect of emotions, social, and personality factors by examining individual investor’s behavior. It also distinguishes those social and psychological factors that have more influence on the investment decisions and those factors that have less influence. We test six social and psychological factors: anger, fear, positive mood, stress, social interaction and herding for their affect on investment decision-making.

Our empirical findings reveal that anger, fear, and a positive mood affects investors’ decision-making positively, whereas stress, social interaction and herding affect investors’ decision-making negatively. Of the six factors tested, anger has the greatest favourable influence on investor decision-making.

The rest of this paper comprises the following sections. Section 2 explains the major theories on which hypotheses are built. Section 3 discusses the method, data collection and statistical techniques used to identify the relationship among variables. Section 4 explains the empirical results. Section 5 sets out the implications, limitations and possible future directions for this study.

2. Theoretical framework and hypothesis development

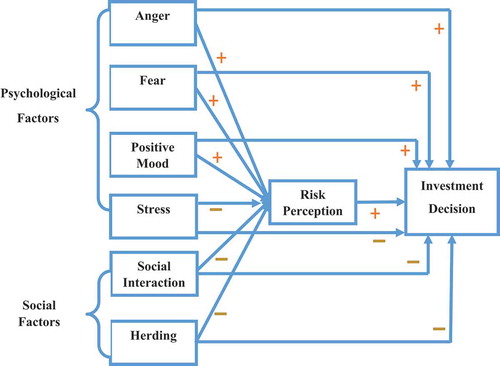

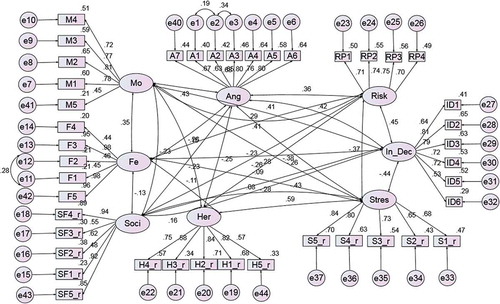

Behavioral finance is inspired by the assumptions of traditional financial theory that claims people behave in a rational way (Markowitz, Citation1952; Sharpe, Citation1964). However, there are many cases where feelings, emotions, fears and other psychological factors which influence the judgments and decision-making of investors and induce them to behave in inconsistent or irrational ways. The theory of a behavioral asset pricing model was proposed in 1994 as an alternative to the traditional theory of the capital asset pricing model. Behavioural theorists conclude that investors make cognitive errors in investment decisions (Shefrin & Statman, Citation1994). According to the literature, the theoretical statements and theoretical frameworks are constructed in accordance with the relationships among the various factors deemed to influence behaviours. In our study, we use the factors identified in the literature as our variables for testing (Figure ).

2.1. Variables

In this section, we examine each of the six factors (anger, fear, positive mood, stress, social interaction and herding) as independent variables for the study.

2.1.1. Anger

The literature shows the impact of anger on individuals’ judgments and decision-making as being positive, negative or neutral depending on the setting used for the study. The results are different as causes of anger are varies i.e., frustration or something bad happens. Some researchers argue that angry investors’ consciousness starts giving them more clues about the situation and they have more hold on the situations than normal investors (Ellsworth & Scherer, Citation2003). Therefore, anger contributes to establishing a way for positive outcomes. Anger uplifts the propensity of investors to observe the circumstances as known, and under their control.

Lerner and Keltner (Citation2001) find a positive relation of anger with investment decisions. Small and Lerner (Citation2008) argue that anger causes for improved memory and analytical ability. Investors use anger and gain a quick analysis of the situation, options and risk. Mitchell and Ambrose (Citation2012) develop a research tool to examine the different emotional states and the relationship of anger with several other variables. Their findings reveal that aggression leads to negative consequences, but anger guides the investors to evaluate situations promptly. It appears that, for investment and financial decision-making, anger has a positive effect on decisions and overall financial performance (Gambetti & Giusberti, Citation2012; Szasz, Hofmann, Heilman, & Curtiss, Citation2016). So, based on literature and relevant theories, we hypothesize that the construct “anger” has a positive relationship with the investor’s decision-making.

H1: Anger positively impacts the investment decision.

2.1.2. Fear

The literature recommends that fear in financial decisions positively influences the outcomes. Fearful individuals make pessimistic judgments about future events (Lerner & Keltner, Citation2001). Logically, fearful investors become more conscious and apprehensive about the circumstances and do not invest in risky and unfamiliar stocks in an attempt to avoid uncertainty (Tiedens & Linton, Citation2001). Moreover, influenced the fear of loss, they try to obtain maximum knowledge about investments which ultimately helps them to improve decision-making and leads them to a positive conclusion. Fear is a negative emotion but its consequences are often positive. The direction of the effect of fear on investment decision-making, however, is not clear.

Katkin, Wiens, and Öhman (Citation2001) state that fear can make people conscious about the danger and thus influences investors to spend time and make clear judgments about underlying investment decisions. By contrast, Chanel and Chichilnisky (Citation2009) argue that fearful investors tend to avoid ambiguity and move towards less risky choices. The element of fear may guide the investors to make avail of fewer profitable opportunities. Fearful investors are considered more cautious and pessimistic in risk-taking options. They feel more uncomfortable in financial decision-making when decisions are risky. So, they may decide to leave the market or make less risky decisions (Lee & Andrade, Citation2011). Fear of loss is an unpleasant feeling and makes the investors think more or avoid the situation. Fear also could be considered as beneficial for the investors because it avoids losses by hesitating to make decisions (Cao, Han, Hirshleifer, & Zhang, Citation2009). When investment options are available and investors are fearful about unfamiliar companies to invest, they use diversification to avoid risk and loss (Kligyte, Connelly, Thiel, & Devenport, Citation2013; Nuñez, Schweitzer, Chai, & Myers, Citation2015). Fear may guide investors to diversify their investments is another important positive impact. Accordingly, we hypothesize that the construct “fear” has a positive relationship with the investor’s decision-making.

H2: Fear positively impacts the investment decision.

2.1.3. Positive mood

While making a decision people consider how they feel, then they take other relevant information, judge the situation, analyze the available choices, and make a decision (Schwarz & Clore, Citation2003). The literature discusses at length two common states of mood viz., positive and negative moods. In general, the different types of moods lead to positive as well as negative effects (Rusting, Citation1998). Grable and Roszkowski (Citation2008) investigate the relationship of mood states and risk acceptance attitudes and find a positive association. Negative mood outcomes are seen as instant and undesirable (Isen, Citation2001). Consequences of negative (or a depressed mood) are negatively related to investment decisions (Hockey, John Maule, Clough, & Bdzola, Citation2000).

The positive mood sways individuals to take risks, that lead to positive outcomes (Johnson & Tversky, Citation1983). The investor’s satisfaction indicates a positive mood. It provides a bright picture of events and an optimistic view of situations (Bless et al., Citation1996; Bless, Schwarz, & Wieland, Citation1996). A happy mood induces risk-taking actions (Lepori, Citation2010; Strydom, Scally, & Watson, Citation2018). It is found that both positive and neutral mood states favour risk-seeking preferences while decision-making (Yuen & Lee, Citation2003). Positive mood expressively improves intuitive judgments (Pham, Citation2007). It leads the investors towards more financial risk takings (De Vries, Holland, Corneille, Rondeel, & Witteman, Citation2012). Accordingly, we hypothesize that the construct “positive mood” has a positive relationship with the investor’s decision-making.

H3: Positive mood positively impacts the investment decision.

2.1.4. Stress

Relationship of human stress and financial decision-making is a topic remains relatively unexplored (Gillis, Citation1993). Decision making when alternative choices are available is quite tactical. In general, it is seen that investors who make decisions under stress would choose a stock which they would not have chosen otherwise. This means under stressful circumstances, people are unable to make optimum use of their cognitive skills, leading them to a negative outcome (Davidson, Jackson, & Kalin, Citation2000). The stress can be such as work stress, investment breakdowns, and even domestic issues. Stress is usually associated with negative experiences. Investors feel pretty worried or distressed under stress. It means when people under stress make a difficult and less wise decision. Decision making under stress shows that a stressed situation is often created ambiguity in the decision-making process (Useem, Cook, & Sutton, Citation2005).

Acute stress may cause decision-making problems for both men and women differently. One performance evaluation study of stress reveals that female participants perform better than male participants when acting under stress (Ganster, Citation2005; Preston, Buchanan, Stansfield, & Bechara, Citation2007). By contrast, another study demonstrates better performance by male participants under stressed circumstances than by females (Shiv, Loewenstein, Bechara, Damasio, & Damasio, Citation2005). Overall the impact of stress on decision-makers’ performance is found a negative (Bos van den, Harteveld, & Stoop, Citation2009; Kalra, Citation2009). Human stress often influences negatively when decisions are to be made under a restricted environment (Norris & Wollert, Citation2011).

Starcke and Brand (Citation2012) ascertain the effect on stress on decision-making and show that decisions made under stress lead to decreased or poor performance and mostly lead to risky investments. Their findings are confirmed by later studies (Matthews, Fallon, Panganiban, Wohleber, & Roberts, Citation2014; Pabst, Brand, & Wolf, Citation2013). So, stress and investment decisions appear to be inversely related to each other. Accordingly, we hypothesize that the construct “stress” has a negative relationship with the investor’s decision-making.

H4: Stress negatively impacts the investment decision.

2.1.5. Social interaction

The literature on social interaction offers theories and empirical studies that examine its impact on individuals and the subsequent consequences. Individuals are surrounded, or to some extent bounded by, social groups which include relatives, friends, and neighbors. (Bala & Goyal, Citation1998).The tendency of individuals to evaluate others and compare themselves with others leads them to question the certainty of events and leads a behavioral bias, particularly when there are large groups for comparison (Holtz & Miller, Citation1985). We draw upon Behavioural economics and network theory that explains how individuals ignore their own knowledge and even fail to gather more information about the decision to be made, in favour of doing what they observe others are doing (Dotey et al., Citation2011). It appears logical that social interaction is negatively associated with investment decisions as individuals tend to be influenced by the group position and perceptions. They believe others’ information as a respectable source, and they prefer those sources to their own beliefs and knowledge. Social projection and informational cascades create great conflict between an individual’s perceptions and others’ respectable information (Kokinov, Citation2003; Kuran, Citation1998).

Madrian and Shea (Citation2001) highlight the importance of social relations and suggestions in saving and investment behaviors, noting that others’ advice works to become the default choice. These behaviors may lead investors to potentially negative returns. The financial advisors are also implicated because they influence the decision-making choices of others negatively (Hirshleifer & Teoh, Citation2003). Studies indicate that individuals use both personal and market information but heavily rely on personal inferences (Ames, Citation2004). This informative function of the social network is due to a lack of information and uncertainty (Hoffmann, Post, & Pennings, Citation2015).

Before making an investment decision, investors gather information from people around such as friends and family (Hong, Kubik, & Stein, Citation2004; Ianole, Citation2011). It is observed from practical field experiments that, while interacting with a large members group, individuals are influenced by the advice of others (Bowden & McDonald, Citation2008) Investors are strongly affected by social contacts in their decision-making and negative productivity is evidence in the form of returns (Wang & Yu, Citation2015). Accordingly, we hypothesize that the construct “social interaction” has a negative relationship with the investor’s decision-making.

H5: Social interaction negatively impacts the investment decision.

2.1.6. Herding

The belief of investors that other investors are “right”, leads them to follow the other investors—a behavior called “herding”. This behavior is observed in stock markets when individuals investors make decisions on the basis of what the majority is doing (Bikhchandani, Hirshleifer, & Welch, Citation1998). Herding behavior is similar to but distinct from social interaction as the latter relates to influence by those within individuals’ social contacts (Celen & Kariv, Citation2004). Many reasons exist why investors to choose to herd e.g., they rely on others’ investors’ information, or they think other investors are better informed (Scharfstein & Stein, Citation1990). This behavior of investors often leads to poor results for the individual investment decision-maker (Bikhchandani, Hirshleifer, & Welch, Citation1992). The literature submits that “herding” negatively influences the perception and decision-making patterns of the individual investor. Investors stop relying on their own set of information and thinking; they do not make a rational choice (Devenow & Welch, Citation1996). When individuals herd, they become blind to their private knowledge (Chang, Cheng, & Khorana, Citation2000). Investors in underdeveloped countries follow herding behaviors is a common practice (Kumari & Sar, Citation2017).

One study finds herding has a carry-on effect, in that past herd behavior may cause the next herd behavior (Hachicha, Bouri, & Chakroun, Citation2007). Further, analysts tend to herd towards pessimistic forecasts when they are not certain or have less information (Van Campenhout & Verhestraeten, Citation2010). Lin (Citation2011) ascertains that females are more prone to herding biases and blindly follow other groups of investors. Similarly, young investors are more to fall prey to herding bias than old investors who are more experienced (Hassan, Shahzeb, & Shaheen, Citation2013; Subash, Citation2012). Results indicate that herding influences the investors’ decisions negatively, in many countries, including India (Agarwal, Verma, & Agarwal, Citation2016). Thus, herding behaviour distorts the decision-making patterns of individual investors (Qasim, Hussain, Mehboob, & Arshad, Citation2019). Accordingly, we hypothesize that the construct “herding” has a negative relationship with the investor’s decision-making.

H6: Herding negatively impacts the investment decision.

2.2. Role of risk perception

The concept of risk perception in decision-making has evolved under many psychological and social theories and approaches. Every human being is different in perceiving the risk at the same time, or at different times, depending on situational factors or personal factors (Slovic, Citation1971). Along with other psychological and social factors, the perception of risk while investing is an important factor, (Johnson & Tversky, 198; Slovic, Fischhoff, & Lichtenstein, Citation1982). The role of risk perception in financial decision-making is discussed by researchers and analysts over many years (Slovic et al., Citation1982). Risk perception is directly associated with the judgments of investment options and the ultimate decision-making (Kahneman & Tversky, Citation1979). Investors’ intuition and psychological factors prompt them to consider options with calculated risk (Slovic et al., Citation1982).

2.2.1. Impacts on risk perception

Communication theory elaborates on the information and communication of risk events (Fischhoff, Citation1995). It is found that age, gender, income and wealth scores can significantly influence the judgments of risk perception and risk tolerance attitudes (Hallahan, Faff, & Mckenzie, Citation2004; Slovic, Peters, Finucane, & MacGregor, Citation2005). A lack of self-confidence, self-control and environmental issues further impact the risk perception ability of individuals (Renn, Citation1998, Citation2004). If risk perception is declared as a subjective matter, investors are influenced by psychological and cultural factors while making a judgment or investment (Slovic, Citation1987; Slovic et al., Citation1982). Additionally, personal emotion and lack of experience strongly influence risk perception (Cohen, Etner, & Jeleva, Citation2008; Slovic, Finucane, Peters, & MacGregor, Citation2004).

Sjöberg (Citation2007) discusses the role and position of emotions in risk perception of investors, arguing that some of the feelings and emotions are positively interrelated to the perception of risk in decision-making procedures. Perception of risk and uncertainty is always considered basic to the decision-making process, however, signal words, movements in surround and effect are also factors to influence risk perception (Williams & Noyes, Citation2007). By using behavioral approaches, emotions and intuition can be used by the investors to measure the intensity of risk associated with particular security while investment decision-making. These behavioral aspects have been neglected in the literature, but more recently intuition and affect are considered to be two major factors which impact the judgments and decision-making processes of individuals (Böhm & Brun, Citation2008). Results indicate that investors exhibit less risk aversion towards a company they know about (Singh & Bhowal, Citation2010). Male and adult participants show more risk-taking and positive attitudes than other sectors of the population (Rhodes & Pivik, Citation2011). Anger and fear can influence the judgments of risk perception in any direction, although in most cases, fear and anger influences risk perception positively (Lu, Xie, & Zhang, Citation2013). Accordingly, we generate the following hypotheses on the impact of psychological and social factors on risk perception:

H7: Anger positively impacts the investors’ risk perception.

H8: Fear positively impacts the investors’ risk perception.

H9: Positive Mood positively impacts the investors’ risk perception.

H10: Stress negatively impacts the investors’ risk perception.

H11: Social interaction negatively impacts the investors’ risk perception.

H12: Herding negatively impacts the investors’ risk perception.

2.2.2. Risk perception as a mediating influence

Empirical studies can help investors improve their decisions by considering all the factors which may distort the way towards making rational decision-making (Hasseldine & Diacon, Citation2005). The dynamics of decision-making involve perceptions of risk. In the decision-making literature, two types of mediators are found: personal or emotional factors (along with demographic characteristics) and behavioural factors. The experience of investors can influence the relationship. Gender, age and marital status are other factors which are involved in determining the decision-making procedures (Cohen et al., Citation2008). Gender and experience are the two most influential factors which can influence the relationships. Other factors influence risk perception, including lack of knowledge, fear and a lack of confidence (Deb & Singh, Citation2018).

Models of decision-making and independent factors incorporating mediating or moderating factors improve the picture of the effects of risk perception on decision-making. Most of the psychological base models use the risk propensity, risk tolerance or risk perception as a mediator in the causal relationships (Hoffmann et al., Citation2015; Mahmood, Ahmad, Khan, & Anjum, Citation2011). The mediating role of risk perception is also analyzed by Riaz and Hunjra (Citation2015), who use psychological factors as the independent variable.

The literature identifies many human and social factors that influence the rational decision-making patterns of stock market investors. Moreover, it indicates that different factors influence different investors in different ways. Further, the results on relationships among different variables indicate that the same variable can produce different associations in different settings. We use risk perception as a mediator variable, as it is a result of the subjective behavior of investors, dependent on psychological factors like anger, fear, mood and stress, and social factors like social interaction and herding behaviours of those individual investors. Accordingly, we generate the following hypothesis to test for mediating effects of risk perception on the different variables and ultimately on the investment decision.

H13: Risk perception positively impacts the investment decision.

H14: Risk perception positively mediates between Anger and the investment decision.

H15: Risk perception positively mediates between Fear and the investment decision.

H16: Risk perception positively mediates between Positive Mood and the investment decision.

H17: Risk perception negatively mediates between Stress and the investment decision.

H18: Risk perception negatively mediates between Social Interaction and the investment decision.

H19: Risk perception negatively mediates between Herding and the investment decision.

In our study, the investment decision of an investor is a dependent variable while anger, fear, mood, stress, social interaction, and herding are taken as independent variables. Risk perception is taken as a mediating variable. The research model for this study is as given in figure-follows:

Kempf, Merkle, and Niessen-Ruenzi (Citation2014) demonstrate that investor’s assessment of risk and return depends on their emotional ratings. If the investor has positive emotions towards the stocks of any company then they expect high returns and also low risk from it. Negative emotions lead to the prediction of high risk and low returns. Lubis, Kumar, Ikbar & Muneer (Citation2015) explain that psychological factors and specific personality traits influence investment decisions. Investors are not always rational; they behave irrationally as they rely more on intuitions rather than collecting valid information before they go for investment decision making. Moreover, investors state that emotions and psychological biases lead to financial loss (Shah, Ahmad, & Mahmood, Citation2017). Boda and Sunitha (Citation2018) describe that investor’s moods and sentiment participate in predicting market movements. Therefore, the understanding of personal investment behaviour enables investors to convert the underlying psychological biases into financial gains. Furthermore, the perception of risk while investing is also an important factor, along with other psychological and social factors. Literate reveals that psychological factors influence the risk perception of investors (Slovic et al., Citation2004). Personal and social factors influence risk perception and in turn, it can impact the judgments and decision-making process (Riaz & Hunjra, Citation2015). Based on the literature we develop the hypotheses and attempt to find the answers to our research questions.

3. Data and method

We use different psychological and social factors that are incorporated to recognize their relationships to improve the investors’ investment decision-making. Our research design consists of eight variables of which six are independent variables (anger, fear, positive mood, stress, social interaction and herding) one mediating variable (risk perception), and one dependent variable (investment decision-making).

3.1. Sample selection

The survey method was used to collect the responses from individual investors in the stock market because it is deemed reliable for collecting the perceptions of respondents about their behaviours (Bloch, Ridgway, & Dawson, Citation1994). The data was collected (June, July & August 2018) through personally distributed questionnaires to selected investors using the stock exchange from the Lahore, Karachi, Faisalabad and Islamabad trading floors of PSX. Israel (Citation1992-B), Godden (Citation2004), Djira, Guiard, and Bretz (Citation2008) and Rea and Parker (Citation2014), suggest the sample size for an unknown population should be a minimum of 385 respondents, to obtain generalizability of results. Accordingly, 650 questionnaires were distributed to the targeted respondents; 510 were returned. Some questionnaires were not completed or completed wrongly, therefore; 40 questionnaires were excluded from the data base. Consequently, 470 questionnaires were used in the analyses. The response rate was 72.30 %.

The sample was extracted using a purposive sampling technique. The individual investors of the PSX were the target population. The PSX is disbursed across stock exchange brokerage houses, so purposive sampling technique is appropriate for selecting the sample. Day traders were excluded from the sample because they are not likely to have knowledge about the application of behavioural theories in decision-making and psychological bias. Only investors aged 25 years or older and with 3 years or more investment experience in the stock exchange were selected for our study. Data were collected on a five-point Likert scale in the questionnaire and the two-step procedure was adopted as proposed by Hoyle and Smith (Citation1994) to access the information. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to extract and analyze results (Nachtigall, Kroehne, Funke, & Steyer, Citation2003).

3.2. Pilot testing

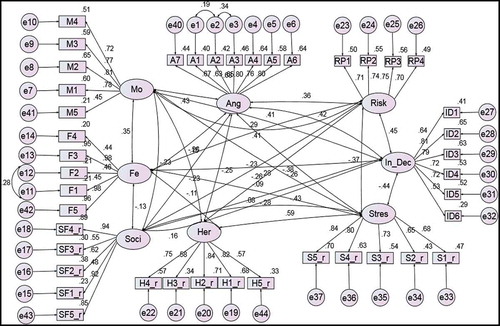

Pilot testing was used to check for possible reliability and validity issues and measurement problems. SEM was used to measure the relationships among variables and hypothesis testing by using AMOS 22.0. According to Scarpi (Citation2006) & Ong et al. (Citation2018), it is the most appropriate data analysis software to check the causal relationships. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is used to check the measurement model as well as the structural model, as supported by Kline (Citation2018). Pilot testing was applied to 210 questionnaires for the refinement of the instrument so that only significant items should be included in the final questionnaire. The model fit indices exhibit the values 0.853, for the goodness of fit index (GFI), 0.831 for the adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), 0.922 for the Comparative fit index (CFI), 0.915 for the Tucker-Lewis coefficient (TLI), and 0.046 for the Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). These results indicate a good model fit.

Convergent validity is exhibited in Table reported to appendix-1. Standardized estimates were applied to make a decision about inclusion or exclusion of the items belonging to each variable. We applied CFA to check the convergent validity of the instrument and items within a construct (Steenkamp & Baumgartner, Citation2000). Items of different constructs were included or excluded based on factor loadings values of each item. Table (see appendix-1) sets out the values of factor loadings of items belonging to the variables used in our study. According to Cua, McKone, and Schroeder (Citation2001) factor loadings values above 0.5 are considered significant to include an item in the instrument. A construct is considered invalid if the factor loading values are less than 0.5, and items below this score were excluded from our study.

Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) argue that the average variance extracted (AVE) must be 0.50 or above for convergent validity. The AVE for the variables is greater than 0.50 in Table A1. Results of factor loadings and AVE initially supporting the existence of convergent validity. However, for final judgment about the instrument, the construct reliability (CR) test was calculated for each variable. The index for the CR should be greater than 0.70 (Netemeyer, Bearden, & Sharma, Citation2003; Slavec & Drnovsek, Citation2012). The CR of all variables in our study is greater than 0.70 in all cases. This means the condition of internal consistency of items exists.

Figure exhibits the relationship of variables and the load factors along with direction and magnitude. These covariance values are used for evaluating the discriminant validity. Inter construct correlation (IC) and the square of inter construct correlation (SIC) were calculated to determine the discriminant validity. The path diagram (Figure ) shows the inter-construct correlations weights between the variables which were used to make decisions on discriminant validity and nomological validity.

Table (see in appendix-1) demonstrate that all the values of IC, SIC and AVE and clearly show discriminant validity is established. The criteria used to measure the discriminant validity is proposed by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981). The condition of discriminant validity is satisfied if the values of AVE are greater than the values of SIC for both constructs. Nomological validity is verified by investigating the inter-construct correlations between the constructs to make sense in the measurement model. Nomological validity should be demonstrated in the proposed model in line with the baseline theory i.e., the coefficient correlation has to be (±) as the directions proposed in the model (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Table A2 confirms that all the variables are interlinked to each other significantly and logically as they are in line (±) with proposed directions and in accordance with the baseline theory. IC values express that a significant association among variables exists and nomological validity is satisfied.

Table exhibits the study variables, number of items and valid items along with reliability scores of each variable. The source of the instrument is also shown. A reliability test is a measure used to assess the consistency of the responses (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, Citation2014). Cronbach’s alpha scores of all the variables are above 0.8 which is acceptable because the criteria are 0.70 or above. The instrument is considered reliable and can be used for further analysis in the main study.

Table 1. Variables detail and their reliability

4. Empirical analysis

This section explains the descriptive statistics present in Table , while correlation analysis discusses in Table , multicollinearity in Table , and model fit indices are exhibited in Table . Hypothesis testing and mediation results are presented at the end of this section.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics (N = 470)

Table 3. Correlation analysis

Table 4. Multicollinearity diagnostics test

Table displays the descriptive statistics of all variables. The mean value of most of the variables (anger, fear, mood, risk perception and investment decision-making) is approaching 4, meaning that most of the respondents agree with the statements about the influence on decision-making. The mean values for three variables (stress, social interaction and herding) are less than 2.50, meaning that respondents tend to disagree. Standard deviation values in all cases indicate that the responses are well dispersed.

Table exhibits the correlation analysis measures the association amongst the study variables. Pearson’s coefficient of correlation is used to provide the direction and strength of the affiliation among different variables. Results show that there is no issue of multicollinearity in the model.

Table explains if there is a high correlation between two or more independent variables used in the study. The variance inflation factors (VIF) and tolerance (Tol) are used as indicators of the existence of a multicollinearity issue. Two versions of the model are examined: the direct model excludes the mediator (risk perception), whereas the indirect model includes the mediator. Results for both models show that all the independent variables are fairly correlated. The value of VIF = 1 means the predictor is not correlated to other predictors, VIF less than 3 is an ideal condition (Hair et al., Citation2014). Table reveals VIF values are low as 1.100 and 1.128 for social interaction and the highest values are exceeding the limit of VIF to meet multicollinearity conditions. So, our results indicate that multicollinearity does not exist.

Table exhibits the results of different measures uses to test the adaptability of the model i.e., CFI, GFI, AGFI and chi-square (Keramati, Mehrabi, & Mojir, Citation2010). Different criteria are used for the acceptable values of these measures. It is suggesting that it is adequate for the model’s “goodness of fit” to check chi-square and absolute fit index along with GFI, AGFI, TLI and NFI (Hair et al., Citation2014). Table confirms the desired model fitness index of the direct model (without mediator) and indirect model including a mediator, as proposed by McAulay, Zeitz, and Blau (Citation2006) and (Roh, Ahn, & Han, Citation2005), which represent the model as a good fit.

Table 5. Model fit index

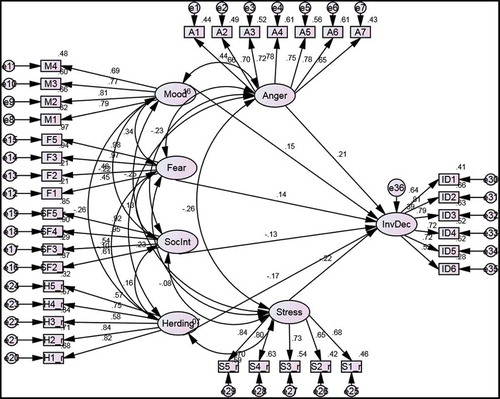

Figure expresses the direct effects of independent variables (anger, fear, mood, stress, social interaction, herding) on the dependent variable (investment decision) without mediation. Furthermore, the regression weights are given on the paths which are used for hypotheses testing. The same values are used in the below tables and we can prove or disapprove our hypotheses.

Table reveals the results of the regression weights of the independent variables (anger, fear, mood, stress, social interaction and herding) on the dependent variable (investment decision). It is evident that anger has a positive and highly significant relationship with an investment decision. Fear and positive mood show a positive and significant positive impact on decision-making. The positive mood has fewer regression weights than anger and fear, but it is still a significant and positive relationship. Furthermore, stress shows a negative relationship with the investment decision with high significance. Social interaction and herding have also a negative but less significant relationship with investment decision-making than stress. All the hypotheses 1 to 6 are thus supported.

Table 6. Regression weights and hypothesis testing (direct effects)

The results support the hypotheses about the direction and magnitude of relationships as all independent variables have a significant role in decision-making whether positive or negative. Anger positively impacts the decision-making of investors in PSX. Angry investors’ consciousness may provide them with more clues about the situation and they are open to observe more circumstances and to have a better understanding of the situations than do normal investors. Fear also has a positive influence on investment decision-making, as the fearful investors may become conscious and apprehensive about the circumstances of an investment, so they avoid uncertainties by not investing in risky and unfamiliar stocks. Fear also induces the investors to spend time and check their judgment on investment decisions. Further, a positive mood can be a source of information. In a positive mood, the investor can bring balanced judgment and clarity that allows the investors to take risks under the positive effect. The positive mood gives them a realistic picture of events and an optimistic view of the situation.

Variables like stress, social interaction and herding have a significantly negative impact on the investment decision of investors in the PSX. Investors may make decisions under stress and choose stocks which they would not have chosen otherwise. This means under stressful circumstances, investors have less control over their thinking and are unable to make optimum use of their cognitive skills, leading them to wrong decisions and negative outcomes. Social interaction also leads investors to make poor decisions. Investors are surrounded by some social groups, including relatives, friends, and neighbors, can be misled or badly influenced. Most of the investors start believing others’ information as a respectable source and they prefer others’ ideas to their own beliefs, intuition and knowledge. So, when investors make decisions on the information provided by social groups, they can make massive mistakes which leads them to poor results. Herding behavior similarly impacts the investment decisions negatively as the belief of investors that other investors are doing “right”, tends them to follow the other investors. Most of the times while making quick decisions, investors choose to herd i.e., they rely on others’ information as they think the information other investors have is better.

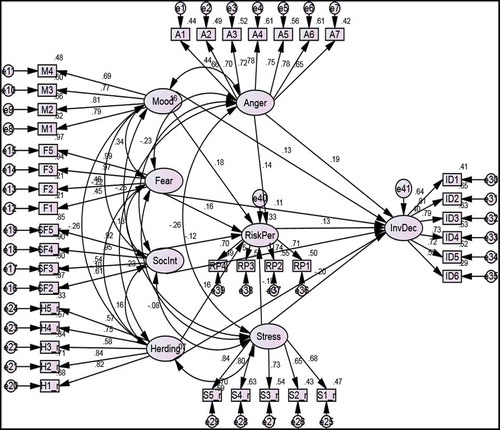

After analyzing the direct relationships, the mediating role of risk perception is checked as shown in Figure . The structural model shows the results of the regression weights of independent variables on the dependent variable with the mediation role of risk perception. The model indicates the direction and magnitude of each of the indirect relationships among dependent, mediator and independent variables of the current study.

Table reveals the results of the regression weights of independent variables (anger, fear, mood, stress, social interaction and herding) on the mediating variable (Risk Perception). It is evident that anger, fear, and positive mood produce positive and statistically significant relationships with risk perception. Thus H7, H8 and H9 are supported.

Table 7. Regression weights and hypothesis testing (indirect effects)

By contrast, stress, social interaction and herding produce a negative but significant relationship with risk perception. So, the results supported H10, H11 and H12. Additionally, the relationship between risk perception and investment decision-making is positive and significant and it follows that H13 is also supported.

Table shares the results of regression weights (indirect effects) of the independent variables (anger, fear, mood, stress, social interaction and herding) on the dependent variable (investment decision) when risk perception is included as the mediator. It is evident that anger has a positive and highly significant relationship with investment decisions when risk perception is used as the mediator. Regression weights are marginally reduced from 0.206 when the mediator is not used to 0.187 when the mediator is used, but this is still significant. Baron and Kenny (Citation1986) suggest that if regression weights are reduced through the indirect effects and the relationship is significant, then the results indicate a partial mediation. So, our results indicate that a partial mediation exists, supporting H14 as anger has both direct effects on investment decision and indirect effects through the mediation of risk perception.

Table 8. Comparison between direct and indirect effects

The variables fear and positive mood show a positive and significant relationship with investment decisions when risk perception involved as a mediator. Regression weights are reduced after mediation and the relationship is significant, so partial mediation exists, and H15 and H16 are supported.

Stress shows a negative relationship with the investment decision when risk perception involved as a mediator with high significance. Regression weights for stress reduced but the relationship is significant which indicates a partial mediation of risk perception. Results for social interaction and herding also indicate similar outcomes. Consequently, H17, H18 and H19 are also supported.

The results of the study indicate that psychological factors have a significant effect on investors’ decision-making, our results support the findings from behavioral finance. Anger, fear and mood have a positive and significant impact on the investment decisions of individual investors. In the state of anger, investors are more likely to use constructive problem-solving skills, leading to positive results as identified by Ellsworth and Scherer (Citation2003). Fearful investors are more conscious about their investments, thus making them more observant and cautious about investment decisions. Our results are in line with the findings of previous studies (Bless et al., Citation1996; Hassan et al., Citation2013; Katkin et al., Citation2001; Tiedens & Linton, Citation2001). A positive mood has also a positive and significant impact on investment decisions, supported by Isen (Citation2001), Yuen and Lee (Citation2003), Vries et al. (Citation2012) and Lepori (Citation2015) and also supported by the theory of “mood as information” by Schwarz and Clore (Citation2003). Our results show that investors under stressful conditions are unable to make positive decisions, due to lack of optimum use of knowledge and experience, in line with the findings of Pabst et al. (Citation2013) and Starcke and Brand (Citation2012).

Social interaction and herding have a negative but significant impact on the investment decisions of individual investors. These results are in agreement with the findings of Janssen and Jager (Citation2003) and Lee and Andrade (Citation2011). The investors under the influence of social circles, friends and relatives make decisions advocated by others, which may mismatch with their own financial knowledge and expertise. Investors often get confused when they get many bits of advice from the people around them and consequently make wrong decisions (Duflo & Saez, Citation2003). Our findings show that herding has a negative impact on the investment decisions of individual investors. While observing the herd behavior of other investors, investors usually follow what the majority is doing and ignore their perception, knowledge and skills. The findings of our study are supported by Ottaviani and Sørensen (Citation2000) and Cipriani and Guarino (Citation2008).

Risk perception positively influences the investment decision-making of investors, results supported by communication theory and the results of past studies (Fischhoff, Citation2013; Renn, Citation2004). Further, risk perception partially mediates the relationship of psychological, social factors and investment decision-making. The direct and indirect effects of psychological and social factors on investment decisions supported by (Johnson & Tversky, Citation1983; Sitkin & Weingart, Citation1995; Slovic et al., Citation1982; Slovic & Peters, Citation2006). Investors’ level of risk perception affects the investment behavior of investors (Deb & Singh, Citation2016; Singh & Bhowal, Citation2010).

5. Conclusion

Our research identifies psychological and social factors of individual investors which influence their processes in investment decision-making. Data are collected from investors of the PSX. Our study uses a survey questionnaire to measure the relationships of different factors in the natural world. We identify the mediating role of risk perception between the independent variables (anger, fear, positive mood, stress, social interaction and herding) and the dependent variable (the investment decision). The results indicate investors agree that psychological factors, social factors and risk perception are significant in investment decision-making.

The variables of anger, mood, and fear are found to be positively and significantly correlated to the dependent variable (Investment Decision) and to the mediating variable (Risk Perception), whereas social interaction, herding and stress are negatively correlated to both the dependent and mediating variables. Anger positively impacts investment decision-making i.e., investors under the state of anger make favorable decisions.

It is recommended that investors should consider psychological factors as well as social factors while making an investment decision. As behavioral finance theories suggest, investors are not always rational. Investors are recommended to avoid making decisions based on what their social interactions lead them to consider to be more reliable information. Further, they should avoid herding by relying on their own knowledge and instincts when making an investment decision. The results of the study may be beneficial for the individual investors, and stakeholders of other developing countries where investors make irrational decisions without having awareness of psychological, social factors in predicting the market sentiments and markets are inefficient. Investors should not ignore but be prepared to deal with such factors as anger, fear, mood and stress. Investors also should be aware of the importance of social factors that can have a great influence on their decisions in the stock market especially those from social interactions and the tendency of herding.

Our study has practical implications for individual investors, institutional investors, and mutual fund managers while making their investment decisions. The outcomes of our study have relevance for shareholders, financial securities traders, financial securities consultants, and financial advisors while making investment decisions (Appendix-2). The results of our research suggest investors make optimistic use of the factors with a positive impact on decision-making while avoiding the factors with negative influence. We examined six variables that influence the investor’s decision-making. This study could be extended by taking investment performance as a dependent variable after analyzing the role of psychological and social factors in decision-making. Furthermore, other external social factors which appear to influence the process of decision-making of the investors could be researched e.g. the role of social and electronic media in investor’s decision-making.

Correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ahmed Imran Hunjra

Abdul Moueed is PhD (Finance) Scholar at National College of Business Administration and Economics (NCBA&E) Lahore, Pakistan. Abdul’s areas of interest are Behavioral Finance, Financial Management, and Stock Markets. Abdul has a wide teaching & research experience at the undergraduate level. Ahmed Imran Hunjra is an Assistant Professor (Finance) at University Institute of Management Sciences-PMAS-Arid Agriculture University Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Ahmed has more than a decade of teaching & research experience. Ahmed is working in the domain of Corporate Finance, Corporate Governance, Behavioral Finance and Financial Risk management. Ahmed has published in well-reputed journals and supervising Master & PhD students.

References

- Agarwal, A., Verma, A., & Agarwal, R. K. (2016). Factors influencing the individual investor decision making behavior in India. Journal of Applied Management and Investments, 5(4), 211–29.

- Ames, D. R. (2004). Strategies for social inference: A similarity contingency model of projection and stereotyping in attribute prevalence estimates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(5), 573–585. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.573

- Azam, M., & Kumar, D. (2011). Factors influencing the individual investor and stock price variation: Evidence from karachi stock exchange. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 5(12), 3040–3043.

- Bala, V., & Goyal, S. (1998). Learning from neighbours. Review of Economic Studies, 65(1), 595–621. doi:10.1111/1467-937X.00059

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research. Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Bhavani, G., & Shetty, K. (2017). Impact of demographics and perceptions of investors on investment avenues. Accounting and Finance Research, 6(2), 198–205. doi:10.5430/afr.v6n2p198

- Bikhchandani, S., Hirshleifer, D., & Welch, I. (1992). A theory of fads, fashion, custom, and cultural change as informational cascades. Journal of Political Economy, 100(5), 992–1026. doi:10.1086/261849

- Bikhchandani, S., Hirshleifer, D., & Welch, I. (1998). Learning from the behavior of others: Conformity, fads, and informational cascades. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12(3), 151–170. doi:10.1257/jep.12.3.151

- Bless, H., Schwarz, N., Clore, G. L., Golisano, V., Rabe, C., & Wölk, M. (1996). Mood and the use of scripts: Does a happy mood really lead to mindlessness? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(4), 665–679. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.71.4.665

- Bless, H., Schwarz, N., & Wieland, R. (1996). Mood and the impact of category membership and individuating information. European Journal of Social Psychology, 26(6), 935–959. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199611)

- Bloch, P. H., Ridgway, N. M., & Dawson, S. A. (1994). The shopping mall as consumer habitat. Journal of Retailing, 70(1), 23–42. doi:10.1016/0022-4359(94)90026-4

- Boda, J. R., & Sunitha, G. (2018). Investor’s psychology in investment decision making: A behavioral finance approach. International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics, 119(7), 1253–1261.

- Böhm, G., & Brun, W. (2008). Intuition and affect in risk perception and decision making. Judgment and Decision Making, 3(1), 1–4.

- Bos van den, R., Harteveld, M., & Stoop, H. (2009). Stress and decision-making in humans: Performance is related to cortisol reactivity, albeit differently in men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34(10), 1449–1458. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.04.016

- Bowden, M., & McDonald, S. (2008). The impact of interaction and social learning on aggregate expectations. Computational Economics, 31(3), 289–306. doi:10.1007/s10614-007-9118-y

- Cao, H. H., Han, B., Hirshleifer, D., & Zhang, H. H. (2009). Fear of the unknown: Familiarity and economic decisions. Review of Finance, 15(1), 173–206. doi:10.1093/rof/rfp023

- Chanel, O., & Chichilnisky, G. (2009). The influence of fear in decisions: Experimental evidence. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 39(3), 1–45. doi:10.1007/s11166-009-9079-8

- Chang, E. C., Cheng, J. W., & Khorana, A. (2000). An examination of herd behavior in equity markets: An international perspective. Journal of Banking and Finance, 24(1), 1651–1679. doi:10.1002/ijc.2910340112

- Chira, I., Adams, M., & Thornton, B. (2008). Behavioral bias within the decision making process. Journal of Business & Economics Research, 6(8), 11–20. doi:10.19030/jber.v6i8.2456

- Cipriani, M., & Guarino, A. (2008). Herd behavior in financial markets: An experiment with financial market professionals. IMF Working Paper. doi:10.1257/000282805775014317

- Cohen, M., Etner, J., & Jeleva, M. (2008). Dynamic decision making when risk perception depends on past experience. Theory and Decision, 64(2), 173–192. doi:10.1007/s11238-007-9061-3

- Cornell, B. (2013). What moves stock prices: Another look. The Journal of Portfolio Management, 39(3), 32–38. doi:10.3905/jpm.2013.39.3.032

- Cua, K. O., McKone, K. E., & Schroeder, R. G. (2001). Relationships between the implementation of TQM, JIT, and TPM and manufacturing performance. Journal of Operations Management, 19(6), 675–694. doi:10.1016/S0272-6963(01)00066-3

- Davidson, R. J., Jackson, D. C., & Kalin, N. H. (2000). Emotion, plasticity, context, and regulation: Perspectives from affective neuroscience. Psychological Bulletin, 126(6), 890–909. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.6.890

- De Bondt, W., Muradoglu, G., Shefrin, H., & Staikouras, S. K. (2008). Behavioral FInance: Quo vadis? Journal of Applied Finance, 18(2), 7–21.

- De Vries, M., Holland, R. W., Corneille, O., Rondeel, E., & Witteman, C. L. M. (2012). Mood effects on dominated choices: Positive mood induces departures from logical rules. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 25(1), 74–81. doi:10.1002/bdm

- De, Holland, Vries, M, Corneille, R. W, Rondeel, O, & Witteman, C. L. M. (2012). Mood effects on dominated choices: positive mood induces departures from logical rules. Journal Of Behavioral Decision Making, 25(1), 74–81.

- Deb, S., & Singh, R. (2016). Impact of risk perception on investors towards their investment in mutual fund. Pacific Business Review International, 1(2), 16–23.

- Deb, S., & Singh, R. (2018). Dynamics of risk perception towards mutual fund investment decisions. Iranian Journal of Management Studies, 11(2), 407–424. doi:10.22059/ijms.2018.246392.672920

- Devenow, A., & Welch, I. (1996). Rational herding in financial economics. European Economic Review, 40(3–5), 603–615. doi:10.1016/0014-2921(95)00073-9

- Djira, G. D., Guiard, V., & Bretz, F. (2008). Efficient and easy-to-use sample size formulas in ratio-based non-inferiority tests. Journal of Applied Statistics, 35(8), 893–900. doi:10.1080/02664760802125544

- Dotey, A, Rom, H, & Vaca, C. (2011). Information diffusion in social media. Final Project. CS224W.

- Duflo, E., & Saez, E. (2003). The role of information and social interactions in retirement plan decisions: Evidence from a randomized experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(8), 815–842. doi:10.1109/ICRA.2011.5980267

- Ellsworth, P. C., & Scherer, K. R. (2003). Appraisal Processes in Emotion. Handbook of affective sciences, 572, V595.

- Fischhoff, B. (1995). Risk perception and communication unplugged: Twenty years of process. Risk Analysis, 15(2), 137–145. doi:10.1109/acc.2013.6580909

- Fischhoff, B. (2013). Risk perception and communication. In Risk analysis and human behaviour (pp. 17-46). Routledge.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gambetti, E., & Giusberti, F. (2012). The effect of anger and anxiety traits on investment decisions. Journal Of Economic Psychology, 33(6), 1059–1069. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2012.07.001

- Ganster, D. C. (2005). Response executive job demands: Suggestions from a stress and decision-making perspective. Management, 30(3), 492–502.

- Gillis, J. S. (1993). Effects of life stress and dysphoria on complex judgments. Psychological Reports, 72(3), 1355–1363. doi:10.2466/pr0.1993.72.3c.1355

- Godden, B. (2004). Sample size formulas. Journal of Statistics, 3(66).

- Grable, J. E., & Roszkowski, M. J. (2008). The influence of mood on the willingness to take financial risks. Journal of Risk Research, 11(7), 905–923. doi:10.1080/13669870802090390

- Hachicha, N., Bouri, A., & Chakroun, H. (2007). The herding behaviour and the measurement problems: Proposition of dynamic measure. Journal of Business and Policy Research, 3(2), 44–63.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Harlow: Pearson Education Limited, UK.

- Hallahan, T. A., Faff, R. W., & Mckenzie, M. D. (2004). An empirical investigation of personal financial risk tolerance. Financial Services Review, 13(1), 57–78.

- Hassan, E., Shahzeb, F., & Shaheen, M. (2013). Impact of affect heuristic, fear and anger on the decision making of individual investor: A conceptual study. World Applied Sciences Journal, 23(4), 510–514. doi:10.5829/idosi.wasj.2013.23.04.13076

- Hasseldine, J., & Diacon, S. (2005). Framing effects and risk perception: The effect of prior performance presentation format on investment fund choice. Journal Of Economic Psychology, 28, 31–52.

- Hirshleifer, D., & Teoh, S. H. (2003). Limited attention, information disclosure, and financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 36(Special Issue), 337–386. doi:10.1016/j.jacceco.2003.10.002

- Hockey, G. R. J, John Maule, A, Clough, P. J, & Bdzola, L. (2000). Effects of negative mood states on risk in everyday decision making. Cognition & Emotion, 14(6), 823-855.

- Hoffmann, A. O. I., Post, T., & Pennings, J. M. E. (2015). How investor perceptions drive actual trading and risk-taking behavior. Journal of Behavioral Finance, 16(1), 94–103. doi:10.1080/15427560.2015.1000332

- Holtz, R., & Miller, N. (1985). Assumed similarity and opinion certainty. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(4), 890–898. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.48.4.890

- Hong, H., Kubik, J. D., & Stein, J. C. (2004). Social interaction and stock-market participation. Journal of Finance, 59(1), 137–163. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2004.00629.x

- Hoyle, R. H., & Smith, G. T. (1994). Formulating clinical research hypotheses as structural equation models: A conceptual overview. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(3), 429–440. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.62.3.429

- Ianole, R. (2011). Exotic preferences: Behavioral economics and human motivation. International Journal of Social Economics, 38(4), 408–410. doi:10.1108/03068291111112086

- Isen, A. M. (2001). An influence of positive affect on decision making in complex situations: Theoretical issues with practical implications. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 11(2), 75–85. doi:10.5465/AMR.2001.4378011

- Israel, G. D. (1992-B). Determining sample size, program evaluation and organizational development. IFAS. PEOD-6. Florida (FL): University of Florida.

- Janssen, M. A., & Jager, W. (2003). Simulating market dynamics: interactions between consumer psychology and social networks. Artificial Life, 9(4), 343–356. doi:10.1162/106454603322694807

- Johnson, E. J., & Tversky, A. (1983). Affect, generalization, and the perception of risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(1), 20–31. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.45.1.20

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291. doi:10.2307/1914185

- Kalra, R. (2009). Financial stress: What is it, how can it be measured, and why does it matter? Economic Review Second Quarter, 40(1), 5–50. doi:10.2469/dig.v40.n1.29

- Katkin, E. S., Wiens, S., & Öhman, A. (2001). Nonconscious fear conditioning, visceral perception, and the development of gut feelings. Psychological Science, 12(5), 366–370. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00368

- Kempf, A., Merkle, C., & Niessen-Ruenzi, A. (2014). Low risk and high return - Affective attitudes and stock market expectations. European Financial Management, 20(5), 995–1030. doi:10.1111/eufm.12001

- Keramati, A., Mehrabi, H., & Mojir, N. (2010). A process-oriented perspective on customer relationship management and organizational performance: An empirical investigation. Industrial Marketing Management, 39(7), 1170–1185. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2010.02.001

- Kligyte, V., Connelly, S., Thiel, C., & Devenport, L. (2013). The influence of anger, fear, and emotion regulation on ethical decision making. Human Performance, 26(4), 297–326. doi:10.1080/08959285.2013.814655

- Kline, R. B. (2018). Response to leslie hayduk’s review of principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 4th edition. Canadian Studies in Population, 45(3–4), 188–195. doi:10.25336/csp29418

- Kokinov, B. (2003). Analogy in decision-making, social interaction, and emergent rationality. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 26(2), 167–168. doi:10.1017/S0140525X03370050

- Krueger, J., & Zeiger, J. S. (1993). Social categorization and the truly false consensus effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(6), 1090. doi:10.1037/h0090369

- Kubilay, B., & Bayrakdaroglu, A. (2016). An empirical research on investor biases in financial decision-making, financial risk tolerance and financial personality. International Journal of Financial Research, 7(2), 171–182. doi:10.5430/ijfr.v7n2p171

- Kumari, N, & Sar, A. K. (2017). Recent developments and review in behavioural finance. International Journal Of Applied Business and Economic Research, 15(19), 235-250.

- Kuran, T. (1998). Ethnic norms and their transformation through reputational cascades. Journal of Legal Studies, 27(2), 623–659. doi:10.1086/468038

- Lee, C. J., & Andrade, E. B. (2011). Fear, social projection, and financial decision making. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(Special Issue), S121–S129. doi:10.1509/jmkr.48.SPL.S121

- Lepori, G. M. (2010). Positive mood, risk attitudes, and investment decisions: Field evidence from comedy movie attendance in the U.S. SSRN. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1690476

- Lepori, G. M. (2015). Investor mood and demand for stocks: Evidence from popular TV series finales. Journal Of Economic Psychology, 48(1), 33–47. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2015.02.003

- Lerner, J. S., & Keltner, D. (2001). Fear, anger and risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(1), 146–159. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.1.146

- Lin, H. (2011). Elucidating rational investment decisions and behavioral biases : Evidence from the Taiwanese stock market. African Journal of Business Management, 5(5), 1630–1631. doi:10.5897/AJBM10.474

- Lu, J., Xie, X., & Zhang, R. (2013). Focusing on appraisals: How and why anger and fear influence driving risk perception. Journal of Safety Research, 45(1), 65–73. doi:10.1016/j.jsr.2013.01.009

- Lubis, H, Kumar, M. D, Ikbar, P, & Muneer, S. (2015). Role of psychological factors in individuals investment decisions. International Journal Of Economics and Financial Issues, 5, 397-405.

- Lucey, B. M., & Dowling, M. (2005). The role of feelings in investor decision-making. Journal of Economic Surveys, 19(2), 211–238. doi:10.1111/joes.2005.19.issue-2

- Madrian, B. C., & Shea, D. F. (2001). The power of suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) participation and savings behavior. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4), 1149–1188. doi:10.1162/003355302753399535

- Mahmood, I., Ahmad, H., Khan, A. Z., & Anjum, M. (2011). Behavioral implications of investors for investments in the stock market. European Journal of Social Sciences, 20(2), 240–247.

- Markowitz, H. (1952). Portfolio selection. The Journal of Finance, 7(1), 77–91. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1861.017.01-02.11

- Matthews, G., Fallon, C. K., Panganiban, A. R., Wohleber, R. W., & Roberts, R. D. (2014). Emotional intelligence, information search and decision-making under stress. Personality and Individual Differences, 60, 03–22. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2013.07.406

- Mayer, J. D., & Gaschke, Y. N. (1988). The experience and meta-experience of mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(1), 102–111. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.55.1.102

- Mayfield, C., Perdue, G., & Wooten, K. (2008). Investment management and personality type. Financial Services Review, 17, 219–236.

- McAulay, B. J., Zeitz, G., & Blau, G. (2006). Testing a ‘Push-Pull’ theory of work commitment among organizational professionals. Social Science Journal, 43(4), 571–596. doi:10.1016/j.soscij.2006.08.005

- Mitchell, M. S. (2006). Understanding employees’ behavioral reactions to aggression in organizations. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 848. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/848

- Mitchell, M. S., & Ambrose, M. L. (2012). Employees’ behavioral reactions to supervisor aggression: An examination of individual and situational factors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(6), 1148–1170. doi:10.1037/a0029452

- Nachtigall, C., Kroehne, U., Funke, F., & Steyer, R. (2003). (Why) should we use SEM? Pros and cons of structural equation modeling. Methods of Psychological Research, 8(2), 1–22.

- Netemeyer, R. G., Bearden, W. O., & Sharma, S. (2003). Scaling procedures: issues and applications.. London: Thousand OaksCA: Sage Publications.

- Norris, W. A., & Wollert, T. N. (2011). Stress and decision making. FLETC training research branch/homeland security. doi:10.1109/ICSIP.2014.75

- Nosic, A., & Weber, M. (2010). How risky do i invest? The role of risk attitudes, risk perceptions, and overconfidence. Decision Analysis, 7(3), 282–301. doi:10.1287/deca.1100.0178

- Nuñez, N., Schweitzer, K., Chai, C. A., & Myers, B. (2015). Negative emotions felt during trial: The effect of fear, anger, and sadness on juror decision making. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 29(2), 200–209. doi:10.1002/acp.3094

- Ong, C. B, Ng, L. Y, & Mohammad, A. W. (2018). A review of zno nanoparticles as solar photocatalysts: synthesis, mechanisms and applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 81, 536-551.

- Ottaviani, M., & Sørensen, P. (2000). Herd behavior and investment: Comment. American Economic Review, 90(3), 695–704. doi:10.1257/aer.90.3.695

- Pabst, S., Brand, M., & Wolf, O. T. (2013). Stress and decision making: A few minutes make all the difference. Behavioural Brain Research, 250, 39–45. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2013.04.046

- Pasewark, W. R., & Riley, M. E. (2010). It’s a matter of principle: The role of personal values in investment decisions. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(2), 237–253. doi:10.1007/s10551-009-0218-6

- Pham, M. T. (2007). Emotion and rationality: a critical review and interpretation of empirical evidence. Review Of General Psychology, 11(2), 155-178.

- Porcelli, A. J., & Delgado, M. R. (2009). Acute stress modulates risk taking in financial decision making. Psychological Science, 20(3), 278–283. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02288.x

- Preston, S. D., Buchanan, T. W., Stansfield, R. B., & Bechara, A. (2007). Effects of anticipatory stress on decision making in a gambling task. Behavioral Neuroscience, 121(2), 257–263. doi:10.1037/0735-7044.121.2.257

- Qasim, M., Hussain, R. Y., Mehboob, I., & Arshad, M. (2019). Impact of herding behavior and overconfidence bias on investors’ decision-making in Pakistan. Accounting, 5, 81–90. doi:10.5267/j.ac.2018.07.001

- Rea, L. M., & Parker, R. A. (2014). Designing and conducting survey research: A comprehensive guide. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 078797546X

- Renn, O. (1998). The role of risk perception for risk management. Reliability Engineering and System Safety, 59(1), 49–62. doi:10.1016/S0951-8320(97)00119-1

- Renn, O. (2004). Perception of risks. Toxicology Letters, 149(1–3), 405–413. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.12.051

- Rhodes, N., & Pivik, K. (2011). Age and gender differences in risky driving: The roles of positive affect and risk perception. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 43(3), 923–931. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2010.11.015

- Riaz, L., & Hunjra, A. I. (2015). Relationship between psychological factors and investment decision making: The mediating role of risk perception. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences, 9(3), 968–981.

- Roh, T. H., Ahn, C. K., & Han, I. (2005). The priority factor model for customer relationship management system success. Expert Systems with Applications, 28(4), 641–654. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2004.12.021

- Rusting, C. L. (1998). Personality, mood, and cognitive processing of emotional information: Three conceptual frameworks. Psychological Bulletin, 124(2), 165–196. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.165

- Scarpi, D. (2006). Fashion stores between fun and usefulness. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 10(1), 7–24. doi:10.1108/13612020610651097

- Scharfstein, D. S., & Stein, J. C. (1990). Herd behaviour and investment. The American Economic Review, 80(3), 465–479.

- Schwarz, N., & Clore, G. (2003). Mood as information: 20 years later. Psychological Inquiry, 14(3), 296–303. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli1403&4_20

- Shah, S. Z. A., Ahmad, M., & Mahmood, F. (2017). Heuristic biases in investment decision-making and perceived market efficiency. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 10(1), 85–110. doi:10.1108/qrfm-04-2017-0033

- Sharpe, W. F. (1964). Capital asset prices: A theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk*. The Journal of Finance, 19(3), 425–442. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1964.tb02865.x

- Shefrin, H. (2006). A behavioural approach to asset pricing (1st ed.). London: Academic Press Inc.

- Shefrin, H. 2008. Developing behavioral asset pricing models. A behavioral approach to asset pricing 2nd. pp.101–148. Elsevier Monographs, number 9780123743565. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-374356-5.X5001-3

- Shefrin, H., & Statman, M. (1994). Behavioral capital asset pricing theory. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 29(3), 323. doi:10.2307/2331334

- Shiv, B., Loewenstein, G., Bechara, A., Damasio, H., & Damasio, A. R. (2005). Investment behavior and the negative side of emotion. Psychological Science, 16(6), 435–439. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01553.x

- Simon, H. A. (1955). A behavioral model of rational choice. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 69(1), 99–118. doi:10.2307/1884852

- Singh, R., & Bhowal, A. (2010). Risk perception of employees with respect to equity shares. Journal of Behavioral Finance, 11(3), 177–183. doi:10.1080/15427560.2010.507428

- Sitkin, S. B., & Weingart, L. R. (1995). Determinants of risky decision-making behavior: A test of the mediating role of risk perceptions and propensity. Academy of Management Journal, 38(6), 1573–1592. doi:10.5465/256844

- Sjöberg, L. (2007). Emotions and Risk Perception. Risk Management, 9(4), 223–237. doi:10.1057/palgrave.rm.8250038

- Slavec, A., & Drnovsek, M. (2012). A perspective on scale development in entrepreneurship research. Economic and Business Review, 14(1), 39–62.

- Slovic, P. (1971). Psychological study of human judgement: implications for investment decision making. The Journal of Finance, 11(1), 1–41.

- Slovic, P. (1987). Perception of Risk. Science, 236(1), 280–285. doi:10.1126/science.3563507

- Slovic, P., Finucane, M., Peters, E., & MacGregor, D. G. (2002). Rational actors or rational fools: Implications of the effects heuristic for behavioral economics. Journal of Socio-Economics, 31(4), 329–342. doi:10.1016/S1053-5357(02)00174-9

- Slovic, P., Finucane, M. L., Peters, E., & MacGregor, D. G. (2004). Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: Some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Analysis, 24(2), 311–322. doi:10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00433.x