?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This article analyses the nexus between exports, established indicators of governance, and economic growth in Fiji. It finds that exports and governance co-operate to promote economic growth. The interplay between these variables is also meaningful. The findings imply that Fiji needs to improve export productivity and quality of institutional governance to ensure persistent rates of economic growth. Other variables such as human capital, private investment, foreign aid, and policy environment are also growth-enhancing in this small and vulnerable economy.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In view of global uncertainties and pessimistic economic outlook around the globe, there is an urgent need to revisit the economic challenges faced by small and vulnerable economies (hereafter SVEs) particularly in the south pacific region. There is no one size fit economic growth model. The economic growth strategies are better understood in country specific context. The economic growth in SVEs often suffer from capacity constraints and quality of governance.

This article promotes an idea that export productivity coupled with good governance is a possible way to sustain decent rates of economic growth in SVEs. Using Total Factor Productivity Analysis, the economic growth is made to depend on growth rates of exports, composite governance indicator and other plausible determinants. The econometric results of our findings have supported the hypothesis of this paper. The research has potential to expand for other smaller economies in the region.

1. Introduction

With world trade being continually affected by the US-China trade, geopolitical tensions, and other compounding uncertainties (including COVID-19), economic activity and incomes have declined rapidly in most countries (Asian Development Bank, Citation2020; The World Bank, Citation2019). The resulting contagion effects are depressing because countries have just recovered from the 2008/9 global financial crisis. To support recovery in the last crisis, Keynesian economic policies were implemented, which, however, did not focus on enhancing productive capacity (International Monetary Fund, Citation2014; Jahan et al., Citation2014). Consequently, government-funded austerity measures have caused fiscal stress in many countries (The United Nations, Citation2012) and these have translated into severe economic burdens, especially in the Small and Vulnerable Economies (SVEs).Footnote1 On the contrary, the withdrawal of such initiatives is upsetting the local political-will, investment climate, and economic activity (The United Nations, Citation2019). The International Monetary Fund (Citation2020) projects a global growth outlook of 3.3% for 2020 and 3.4% for 2021, but these are likely to be revised downwards, confirming that risks are intensifying almost everywhere leading to difficult socio-economic consequences (Asian Development Bank, Citation2020; Sellers et al., Citation2019). Situations in the SVEs are worsening faster because of their less agile economic systems, fragmented markets, weak institutions, and high-dependency on foreign aid.

The past economic crises have shown that weak institutions can even fail efficient markets (Diamond & Rajan, Citation2009; Page & Tarp, Citation2017; The World Bank, Citation2000). Acemoglu and Robinson (Citation2012) dispense a classic on why nations fail and they recently discuss how the balance of power between the state and the society can promote human welfare (Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2019). Their “Shackled Leviathan” (guardian of good governance) is the key to promoting economic opportunity and prosperity. In the South American and African states, parts of Europe and Asia, other ugly versions of the Leviathan is also blamed for reduced liberty and ill-fare. Therefore, despite the stages of development, economic growth is hindered by unresponsive and corrupt administrations usually cultivated under weak governance structures.Footnote2 Institutions are impactful as they can acquire and utilise resources and information unlike private agents (The World Bank, Citation2013). Further, this line of thinking has created influential literature to promote our understanding of the role of institutions in societiesFootnote3 (see, for Acemoglu, Citation2002; Citation2010; Acemoglu et al., Citation2005; Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2001; Citation2012). This body of literature, however, lacks insights on SVEs.

The current paper contributes to the literature by promoting the idea that export productivity coupled with good governance can sustain decent rates of economic growth in the SVEs.Footnote4 We focus on SVEs because they have capacity constraints to benefit from free trade which restricts their economic prospects. Conventional wisdom states that good governance promotes superior trade performance because transparency reduces corruption and creates ethical exchanges (Kaufmann et al., Citation2004; The World Bank, Citation2007). Besides, it is attractive to international donors and development partners who are crucial agents for developing the needed capacity in the SVEs (The United Nations, Citation2019). The WTO’s Aid-for-Trade program is based on this novelty and has been instrumental in supporting the aspirations of SVEs in achieving the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (The World Trade Organization, Citation2019). This paper aims at using the established indicators of governance to determine if trade-based growth supported by good governance is possible in small economies. We take Fiji as a representative SVE due to the availability of data.Footnote5 Besides, Fiji is exploring trade opportunities with its new trade policy framework and is a signatory to several regional and international trade agreements. Furthermore, the local literature on trade, governance, and economic growth is limited for this small economy.

The curent paper is structured as follows: Section 2 is a brief survey of literature while Section 3 specifies the model and variables. Key findings are discused in Section 4. Sections 5 and 6 include senstivity analysis, while Section 7 concludes the paper with implications for trade-based growth policy.

2. Literature review

The literature on trade, governance, and economic development is voluminous—our summary is given below. But first, we devote some space for indicators of governance and their measurement. In recent years, there has been an upsurge in demand for better governance indicators. Some internationally recognized ones are: Freedom House Survey Index,Footnote6 International Country Risk Guide,Footnote7 Transparency International Index,Footnote8 Global Integrity Index,Footnote9 Open Budget Index,Footnote10 Global Competitiveness Index,Footnote11 and Countries Performance and Institutional Assessment based statistics.Footnote12 The Worldwide Governance Indicator (known as WGI/KKZ) is well-regarded in the literature. It ranks countries into six different aspects of Kaufmann et al. (Citation1999a) and (Kaufmann et al., Citation1999b). The WGI dataset has been produced bi-annually from 1996–2002 and annually from 2002 onwards by the World Bank. Far and large, this is a break-through in quantitative measurement of governance (a highly qualitative variable) and its composite index for Fiji is also used in this paper.

The WGI is developed from individual variables measuring different aspects of governance but the six board sub-indicators are: Voice and Accountability, Political Stability and Violence, Governance Effectiveness, Rule of Law, and Control of Corruption are available. These are defined in Kaufmann et al. (Citation1999a; Citation1999b)). However, there has been significant debate on the methodology of WGI, generally on the relevance of the said indicators to capture the true essence of quality of governance, including measurement issues. These are discussed in Arndt and Oman (Citation2006), Knack (Citation2006), Thomas (Citation2009), and Kaufmann et al. (Citation2007) provide a detailed response to the major critics. Table below shows basic WGI statistics for selected developed and developing countries (including SVEs of the Pacific). The trends are interesting!

Table 1. Governance indicators (5-yr average)

In Table , Voice and Accountability are significantly higher in the OECD countries. However, it declined in the US since 2000 but improved somewhat in Japan. In the large developing country sample, China recorded the worst outcome. In comparison, smaller economies performed better. Similar trends are noted for Political Stability and Absence of Violence and Terrorism. France, the UK, and the US rank at the bottom of the OECD group, but these have improved for almost all OECD countries. In large developing countries sample, Colombia ranks the lowest after India and Kenya, but others show marginal improvement. Mauritius has performed reasonably well, while almost 50% of the Pacific SVEs recorded good outcomes. The Solomon Islands show significant improvement since 2011 and the other good performers are Vanuatu, Samoa, and Tuvalu. All OECD countries (excluding France) have had an impressive outcome on the Effectiveness of Governance. The large developing countries seem to have lost some grounds, except for Kenya and Colombia. The Pacific nations (except for the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, and Samoa) do not show much progress.

Data also show that the Quality of Regulations has been high in the OECD sample. In developing countries, South Africa and Mauritius have improved their performances, while this indicator has declined for almost all developing countries in the sample. The worst outcome has been recorded in Argentina. In the Pacific, a similar trend has been noted, but the Solomon Islands and Kiribati have had the worst outcomes. The Rule of Law indicator has been consistently high for all the OECD countries but in the developing country sample, Argentina and Kenya rank at the lowest. Data show that Kenya and Colombia seem to have improved on this recently while the rest have shown marginal progress. The developed countries show improvement in Control of Corruption, except for the USA. However, most large developing countries have declined in this indicator with Kenya being at the bottom. China has made significant improvements, like most of the Pacific SVEs. However, PNG ranks lowest with only marginal improvement in this indicator.

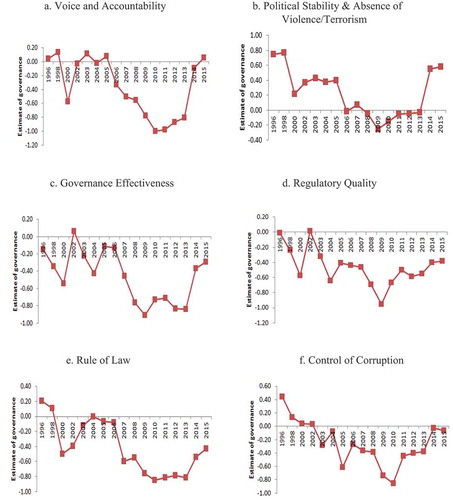

For Fiji, the political situation has been very fragile, with frequent change of governments. Data show that during the political instability periods (1987, 2000 and 2006) Voice and Accountability were low, (Figure )). However, the current Government has improved the Fijian constitution and maintained stability by preventing any political unrest since 2006. These could have led to positive developments noted in Figure ). On Governance Performance (Figure )) Fiji recorded a decline in 2000 and in the 2006–2013 period. The Government Effectiveness data (Figure )) shows unsatisfactory performance since 1996, but there were some positive outcomes possibly connected to the restoration of democracy following the 2014 general elections. The Regulatory Quality (Figure )) indicator shows a fragile performance since 2002. However, following 2012, this has marginally improved. Data on Rule of Law (Figure )) generally declined from 1996 until 2013 but improved since. This could be related to strengthening security forces, better regulations, and strategic institutional reforms recently undertaken in by the Government. The indicator on Control of Corruption (Figure )) was low during the 1996–2010 period but it improved afterward. We conjecture that the establishment of Fiji’s Independent Commission Against Corruption (in 2009) and the Financial Intelligence Unit (in 2006) could have possibly contributed to this positive outcome.

Figure 1. Governance indicators for Fiji (1996–2015).

More intensive analysis of the impact of good governance on national economies is noted from the international literature. For example, Campos and Nugent (Citation1999) and Kaufmann et al. (Citation1999a; Citation1999b) suggest that good governance can strongly promote development.Footnote13 Chauvet and Collier (Citation2004) argue that countries with less developed governance structures experience lower rates of growth. Likewise, Emara and Chiu (Citation2015) suggest that selected countries in the Middle East and North Africa show a positive association between governance and growth. Sen (Citation1999) points out that macroeconomic stability and good governance have a significant positive impact on economic development as well. Saha et al. (Citation2014) find that institutional development associated with mature democracy is crucial for economic development. Fosu (Citation1992) conclude that long-run growth is reduced by political instability and Barro (Citation1996) show the plausible negative effects of political instability on economic development. Alesina and Perotti (Citation1994) state that weak institutions reduce growth through their negative impact on investment while Knack and Keefer (Citation1997) stress that protection of property rights and the ability to enforce contracts are a positive stimulus to growth.

The literature on SVEs is relatively limited. Some influential studies, for example, Congdon Fors (Citation2014) finds that country size is negatively related to institutional quality. Brown (Citation2010) suggests that a strong institution is a pre-requite to development while the binding constraints of the small states hinder the development of the strong public institution. However, there is a strong body of literature on development issues of SVEs, which argues that the core of the hardships in these economies lies in their weak economic potential dictated by narrow resource base and small populations (Asian Development Bank (Citation2020); The United Nations (Citation2019), Tisdell (Citation2014), Bertram (Citation2006), Armstrong et al. (Citation1998), and Armstrong and Read (Citation1998). Although all studies on SVEs discuss the underlying characteristics of these economies, the Asian Development Bank (Citation2020) considers the Asia-Pacific regional SVEs’ vulnerability to COVID-19 and its impact on the national economies. This together with The United Nations (Citation2019) report explain how vulnerable these economies are, in the face of exogenous shocks and weak domestic capacity. Similarly, Briguglio (Citation1995) state that SVEs’ special disadvantages render these economies very vulnerable to forces outside their control—a condition which sometimes threatens their very economic viability. Alesina and Wacziarg (Citation1998) argue that smaller countries have larger public sectors and are more open to trade which could increase their exposure making them vulnerable to external shocks. Bertram (Citation2006) states that the combination of a large government sector and a limited productive base, left post-colonial small state economies quite reliant upon state employment and aid funding. Armstrong et al. (Citation1998) show that most successful microstates are associated with not only a rich exportable resource base but successful tourism and business/financial services.

Studies on Fiji are only a handful. Jayaraman (Citation2006) argues that weak investment climate and lack of business confidence have strong connections with weak institutions. Prasad (Citation2003) propose that property rights which would enable enforcement of contracts and lowered transaction costs can promote productivity in Fiji. Gounder (Citation2004; Citation2005)) suggests that political instability adversely affects economic growth through investment. Gani and Duncan (Citation2007) developed an index of governance based on 3 dimensions of WGI (rule of law, government effectiveness, and regulatory quality) and find that governance in Fiji was badly affected by the weakening of the quality of institutions and rule of law. However, they do not conduct empirical tests. Gounder and Sooreea (Citation2013) show that negative political developments have had significant adverse effects on economic growth by reducing foreign direct investment and exports. All these studies highlight the need to improve institutional governance in Fiji, possibly with reforms.

3. Model specification

In exploring the connection between export performance, governance, and economic development in Fiji (the latter proxied by real GDP growth), time-series data for the period 1970–2015 are used. The aim is to evaluate how exports complemented by governance indicators (together with other conditioning variables) affect Fiji’s real income. The World Bank data for Fiji are available on the six sub-indicators of governance only from 1996–2015. Therefore, our first set of analysis relates to this sub-sample. Governance in this paper is taken as a composite average of these sub-indicators (denoted as GG). Noting the limited data points in this experiment, POLITY2, an index of democracy measured by INSCR is used as an alternative measure in the second set of regressions. Data are derived from the Fiji Bureau of Statistics (various years), RBF-2018, IFS-2018, World Bank/WDI-2018 databases, and the INSCR database. The real capital stock is extracted from the Penn World Table 8.1 and labor employment is proxied by population in the age of (15–64) years. All variables are in natural logs, except for POLITY2. Details of data are in Appendix-A1.

In what follows, we discuss the empirical procedures and key findings. First, the growth rate of TFP (Total Factor Productivity) is estimated and made to depend on growth rates of exports, composite governance indicators, and other plausible growth determinants. This approach is based on an IMF study (Senhadji, Citation2000) and is different from others which use the growth rate of output as the dependent variable. The idea here is that productivity growth is a better proxy for economic growth because the annual or short span of data does not guarantee that an economy has achieved the steady-state (Singh, Citation2014; Solow, Citation2008). In addition, it is claimed that any variable that impacts TFP directly affects economic growth, Solow (Citation2008). These are the underlying premises of our TFP-based growth regressions.

However, the modeling strategy involved in this experiment is laborious but can be explained as follows. First, we estimate a production function using the Solow (Citation1956) approach but advanced by Mankiw et al. (Citation1992). The real output (Y) is assumed to depend on an index of knowledge (A) and traditional inputs such as K (physical capital), L (labor), and H (human capital). H is human capital as estimated by Barro and Lee (Citation1993) method.Footnote14 The share of capital (= 0.33) is theoretically assumed parameter. The constant returns to scale Cobb-Douglas production technology is represented as (1) below:

All variables are defined above. Taking logs and the first difference of (1), we get EquationEquation (2)(2)

(2) .

EquationEquation (2)(2)

(2) is re-parametrized and used to compute the growth rate of productivity

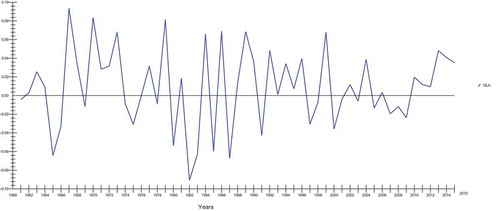

residually. We are aware of the limitations in residual-based TFP but agree with Pritchett (Citation2006) that with a lack of real data (on TFP), we settle for the second-best. We will revisit this issue through sensitivity analysis later in the analysis. Figure shows that after highly volatile growth rates in the mid-1980s, productivity growth in Fiji seems to have stabilized in the recent past. The latest productivity report (Fiji National Productivity Centre, Citation2019) also states that since 2012, productivity has increased.

4. Interpretation of RESULTS

Now we concentrate on our key task—estimating growth effects. Senhadji (Citation2000) estimated TFP similarly and related it to a set of hypothesized growth-enhancing variables for most developed and developing countries. We conjecture that real exports, governance indicators, and other conditioning variables such as human capital, private investment, government expenditure, etc. are important determinants of growth. Estimates in the first difference of variables are obtained using OLS Non-linear Least Squares Method (Table ). Column (A) shows conventional estimates without the composite governance indicator, and we get theoretically consistent results for all plausible determinants included in the analysis. Exports (RX) seem to drive growth rates, together with human capital (HK) and private investment (IRAT). Foreign aid seems to inject significant positive influence. The goodness of fit indicates a need for improvement, but the estimates are quite reasonable and without diagnostic problems.

Table 2. Effects of exports on growth (1970–2015)

We then added the governance indicator (GG) and find its positive and significant impact on economic growth, Column (B). The inclusion of GG also leads to an improvement in the growth effects of human capital and exports. We also estimate the effects of interacting exports and governance and the results are plausible. In addition, the difference in the explanatory power of (B) relative to (A) indicates the important role of governance in trade-based growth. To minimize endogeneity bias, (B) is re-estimated using the two-stage instrumental variables (2SIV) method and reported in (C). The results are quite consistent and respond well to the instruments (one-period lagged independent variables) used, without compromising the goodness of fit or diagnostic tests. The adjusted R and GR squares are close as well. We then introduced the POLITY2 indexFootnote15 in the model to capitalize on the weakness of limited data points in the above analysis. The extended sample now is 1970–2015. Estimates in (D) show that the growth effect of POLITY2, together with that of its interaction is reasonable and agrees with the conclusions derived with GG. Finally (D) is re-estimated with the 2SIV method and the results affirm the above findings. Due to increased data points and consistent results obtained with 2SIV, (E) is our preferred model.

Model (E) agrees with some of the earlier findings stated above, as well as with others in the literature. The active role of institutions is evident in Fiji. This agrees with Gounder and Sooreea (Citation2013) who show that political instability has had serious negative impact. Other studies (Gounder (Citation2004; Citation2005), Jayaraman (Citation2006), and Gani and Duncan (Citation2007)), although not comparably analytical, are similar in their conclusions about the role of governance. Due to data limitations, we used alternative proxies with sensitivity tests (details below) and found that governance indicators are statistically significant determinants of growth along with others such as human capital and private investment. This agrees with the general findings on the role of institutions, such as with Congdon Fors (Citation2014) who suggests that both political and economic institutions are important. The link between improvement in governance quality and positive growth is also established by Emara and Chiu (Citation2015). Other estimates in (E) are consistent with our earlier findings. So far, it can be concluded that economic growth in Fiji depends heavily on international factors (exports and foreign aid) and ability to engage with trade partners (good governance, human capital and private investment). We find small but significant influence of indicators of governance, and impacts as expected for foreign aid, investment, human capital and exports productivity.

The diagnostic test results are reasonable and all variables are significant and appropriately signed. The adjusted R and GR squares are close. Sargan’s X2 = 2.03 with p = 0.15 implies adequacy in instruments. The estimates identify that traditional forces of growth are important, but good governance and export performance work jointly to promote economic growth in Fiji. This is consistent with but updated from Jayaraman (Citation2006) and Gounder (Citation2004; Citation2005)). However, due to lack of empirical studies on Fiji, these are less comparable. In the present paper, importance is placed on the use of better proxies of governance, robust estimation methods, and revised dataset. We also obtain evidence that the dynamics between governance and exports are noteworthy. That is, Fiji’s trade and international relations must demonstrate principles of good governance to promote economic growth.

5. Sensitivity analysis: methodology

In the above analysis, issues surrounding the estimation of TFP could induce fragility in the estimates. As such, one needs to conduct sensitivity analysis possibly using alternative methodologies, data sets, and assumptions. To further gain confidence in our findings, we invoked another but consistent estimation technique. This second modelling framework is based on Rao and Singh (Citation2010), where pre-estimating TFP is not required. For a detailed review of this approach, see Singh (Citation2014). We use both the GGI and POLITY2 indices, sequentially, and maintain the application of a two-stage instrument technique to control for reverse causation.

The present approach is based on estimating an augmented production function with constant returns to scale and an extended definition of TFP. Here, the TFP is made to depend on any plausible growth factor (RX, for example). One may recall that in the original model of Solow (Citation1956), TFP growth is exogenous. The Solow model is essentially represented by EquationEquations (3(3)

(3) and Equation4

(4)

(4) ), where the output (Y) depends on the level of technology (A) and other traditional inputs labor (L) and capital (K), with the assumption that g1 = 0.

We argue that if RX promotes growth, g1 will be significantly greater than zero. To estimate the growth effects of exports with good governance (GG), the following alternative specification of (3) is derived after substituting an extended version that incorporates GG and RX of (4) into (3).

The assumption here is that productivity depends on exports, its interaction with the governance indicator, as well as other plausible forces of growth. In (5) the variables (y, h, k) are in per worker terms. The conditioning variables (vector of Zt’s) include a theoretically consistent set of determinants of growth, as used in the previous analysis (Table ).

6. Sensitivity analysis: results

All estimates are obtained using the LSE-Hendry’s GETS method, see Hendry et al. (Citation1984) for an explanation. This is a widely used approach for time series work involving dynamic specifications. Using the standard variable deletion tests, we arrived at the most parsimonious estimates in Table , controlling for path dependency bias, auto-correlation, heteroscedasticity, and misspecification of functional form. The results obtained with the standard GETS non-linear least square method, following Unit Root testsFootnote16 initially, and then with 2 stages instrumental variable option.

Table 3. Effects of exports performance on growth rate

Estimates in column (A) are conventional without the governance indicator. Including POLITY2 and its interaction with exports, we find that consistent and improved estimates, column (B). We then re-estimated (B) with a 2-SIV method by including one period lagged independent variables as instruments. The estimates are good, with adjusted GR square adequately high. Sagan test rejects the null of inadequate instrument selection at a 5% level. As in the analysis before, the interaction and their dynamics significantly affect the growth rate of output. Human and physical capital per worker, investment, and policy environment impact economic growth as expected, with correct signs. The diagnostic test results are appropriate and the speed of adjustment to long-run equilibrium (λ) is high and significant. Finally, we tested if our conclusions would differ when POLITY2 and exports (RX) are introduced as “shift variables” in the production function. This is reflected in D obtained using the 2-SIV method. The results, after removing some dynamic variables, are not systematically different. Thus, we converge to accepting C-2SIV as the final model, indicating that governance and exports co-operate to promote economic growth in Fiji. Sadly we do not have many comparative studies on Fiji to compare our results. But we present updated evidence to previous empirical studies.

7. Conclusions and policy implications

The essence of literature on governance and growth is that institutions matter for long-run stable growth (Acemoglu et al., Citation2005). Earlier discussion was concerned with nexus between democracy and growth (Barro, Citation1996), for example. Congdon Fors (Citation2014), while articulating political institutions (democracy) and economic institutions (rule of law), finds that economic institutions account for better economic performance. Our present study is an addition on the existing literature on SVEs. It investigates the trio relationship of export, good governance and economic growth. Political and economic institutions related variables along with other control variables have been included our empirical model. The results identify that traditional forces of growth are important, but good governance and export performance work jointly to promote economic growth in Fiji. This is consistent with but updated from Jayaraman (Citation2006) and Gounder and Sooreea (Citation2013). The importance is placed on the use of better proxies of governance (such as WGI), robust estimation methods, and revised dataset. It is also evident that the dynamics between governance and exports are noteworthy, and for this reason, the paper suggests developing quality of institutions in Fiji. As shown in Tables and , the interaction among governance and exports and their dynamics, significantly affect the growth rate in Fiji.

The findings confirm that exports and governance co-operate, and thus, the manner in which these dynamics are managed has important implications on Fiji’s export performance and economic growth. Besides, physical and human capital, FDI, private investment, and policy environment are also important sources of growth. Fiji being a small and vulnerable economy continues to face several economic challenges, and should, therefore, improve the existing institutions through bold and systematic reforms. This will make Fiji a more competitive and attractive destination for foreign investment. The lesson for other SVEs is that good governance is necessary to benefit from trade-based growth policies. The role of governance in resource allocation, investment in infrastructure, social protection and environmental protection should be given same priority with other roles.

Authors’ statement

Key Research areas: Governance and growth, Macro-financial risks in the South Pacific, and COVID-19 on Tourism and Housing. This paper directly relates to our first research activity related to the role of good governance in promoting economic growth and export.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ronal Chand

Ronal Chand Teaching Assistant in Economics, Faculty of Business and Economics (FBE) University of South Pacific (Suva) Fiji. His research interests are in the areas of Trade, Economic growth, Governance, Agriculture and Health efficiency.

Rup Singh

Rup Singh Senior Lecturer in Economics, Faculty of Business and Economics (FBE) University of South Pacific (Suva) Fiji. Former Central Banker. Research interests: Economic Growth, Monetary Policy and Applied Econometrics.

Arvind Patel

Arvind Patel Professor of Accounting and Finance, Faculty of Business and Economics (FBE), University of South Pacific (Suva) Fiji. Distinguished career as an academic and administrator. Research interest: Corporate Governance, Fraud, Ethics and Auditing

Devendra Kumar Jain

Devendra Jain Senior Lecturer in Finance, Westminster International University of Tashkent. Research interests: Macro-Financial Risks, Foreign Currency Exposure and Financial Markets.

Notes

1. These are economies with small populations (below 5 million), landlocked, limited resources, and technological constraints. They depend heavily on imports for consumption, economic activity and trade. Foreign aid, heavy migration and remittance incomes additionally support livelihoods in such economies.

2. Acemoglu and Robinson (Citation2019) label it as “Desolate and Paper Leviathans” which are less desirable and require honest reforms.

3. The Institutional Economics literature (North, Citation1981; Citation1990) view institutions as a deeper source of economic development as they incentivise innovation and risk-taking by reducing transaction costs and uncertainty.

4. But of course, there could be other determinants of growth—for an exhaustive survey, see Durlauf et al. (Citation2005).

5. Fiji has less than 1 million people, and is heavily dependent on imports and international support. Besides, Fiji has unsettled land ownership and land administration issues restricting the supply of land.

6. The survey covers 193 countries, data available from www.freedomhouse.org

7. This evaluates economic, financial and political risks for 161 countries.

8. The Corruption Perception Index (released in 1995) ranks 180 countries by their perceived levels of corruption guided by expert assessments and opinion polls.

9. An index of independent, non-profit organisation tracking governance and corruption trends around the world.

10. Measures the extent to which budget processes are open to their citizens.

11. Is an index for measuring competitiveness of countries, documentation are available at www.weforum.org

12. Produced annually by the World Bank, now included in WDI.

13. Of the sixteen (16), five (5) are the WGI. The World Bank (Citation2007) elaborates that many NGOs the U.S. Government and other donors rely on the WGI to evaluate the quality of governance for determining aid programs.

14. In this method, years of schooling data and average rate of returns of 9% (see Singh (Citation2014) are used.

15. Marshall et al. (Citation2016) present the methodology of the POLITY index. In summary, the POLITY is computed by subtracting the autocracy score from the democracy score which is obtained using country surveys. The resulting combined POLITY score ranges from +10 (strongly democratic) to −10 signifying strongly autocratic.

16. Details of Unit Root tests are available from the authors. In summary, we find all variables are difference stationary.

References

- Acemoglu, D. (2002). Technical change, inequality, and the labor market. Journal of Economic Literature, 40(2002), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.40.1.7

- Acemoglu, D. (2010). Theory, general equilibrium, and political economy in development economics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(3), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.24.3.17

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. (2005). Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run growth. Handbook of Economic Growth, 1(6), 386–472.

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1369–1401. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.91.5.1369

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Crown Business.

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2019). Why nations fail: The narrow corridor states, societies, and the fate of liberty. Penguin Press.

- Alesina, A., & Perotti, R. (1994). The political economy of growth: A critical survey of the literature. The World Bank Economic Review, 8(3), 351–371. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/8.3.351

- Alesina, A., & Wacziarg, R. (1998). Openness, country size and government. Journal of Public Economics, 69(3), 305–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(98)00010-3

- Armstrong, H., Kervenoael, D., Li, X., & Read, R. (1998). A comparison of the economic performance of different micro-states, and between micro-states and larger countries. World Development, 26(4), 639–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00006-0

- Armstrong, H., & Read, R. (1998). Trade and growth in small states: The impact of global trade liberalization. The World Economy, 21(4), 563–585. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9701.00148

- Arndt, C., & Oman, C. (2006). Uses and abuses of governance indicators, OECD development centre studies. OECD Publishing.

- Asian Development Bank. (2020). The economic impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on developing Asia (ADB Briefs No 128). ADB.

- Barro, R. (1996). Democracy and growth. Journal of Economic Growth, 1(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00163340

- Barro, R., & Lee, J.-W. (1993). International comparisons of educational attainment. Journal of Monetary Economics, 32(3), 363–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(93)90023-9

- Bertram, G. (2006). Introduction: The MIRAB economy in the twenty-first century. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 47(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8373.2006.00296.x

- Briguglio, L. (1995). Small island developing states and their economic vulnerabilities. World Development, 23(9), 1615–1632. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(95)00065-K

- Brown, D. (2010). Institutional development in small states: Evidence from commonwealth Caribbean. Halduskultuur – Administrative Culture, 11(1), 44–65. http://halduskultuur.eu/journal/index.php/HKAC/article/view/13

- Campos, F., & Nugent, B. (1999). Development performance and the institutions of governance: Evidence from East Asia and Latin America. World Development, 27(3), 439–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00149-1

- Chauvet, L., & Collier, P. (2004). Development effectiveness in fragile states: Spill overs and turnarounds. Centre for the Study of African Economies, Department of Economics, Oxford University.

- Congdon Fors, H. (2014). Do island states have better institution? Journal of Comparative Economics, 42(1), 34–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2013.06.007

- Diamond, D. W., & Rajan, R. G. (2009). The credit crisis: Conjectures about causes and remedies. American Economic Review, 99(2), 606–610. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.2.606

- Durlauf, N., Johnson, P., & Temple, J. (2005). Growth econometrics. Handbook of Economic Growth, 8(1), 555–677.

- Emara, N., & Chiu, I. (2015). The impact of governance on economic growth: The case of Middle Eastern and North African Countries. MPRA Paper 68603. University Library of Munich.

- Fiji National Productivity Centre. (2019). Fiji national productivity master plan 2021–2036. Asian Productivity Organization.

- Fosu, A. (1992). Political instability and economic growth: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 40(4), 829–841. https://doi.org/10.1086/451979

- Gani, A., & Duncan, R. (2007). Measuring good governance using time series data: Fiji Islands. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 12(3), 367–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860701405979

- Gounder, R. (2004). Fiji’s economic growth impediments: Institutions, policies and coups. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 9(3), 301–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354786042000272973

- Gounder, R. (2005). Fiji’s public-private sector investment, policy, institutions and economic growth: Evidence from time series data. Fijian Studies, 3(1), 87–110.

- Gounder, R., & Sooreea, R. (2013). Understanding foreign direct investment and economic growth in export-oriented economies: Case study of Fiji and Mauritius. Presented at American Economic Association allied social science associations conference 2013, San Diego, California, United States.

- Hendry, D., Pagan, A., & Saragan, J. D. (1984). Dynamic specification. In Z. Grilliches & M. Intriligator Eds., Handbook of econometrics (Vol. 2, pp. 1023-1100). Elsevier.

- International Monetary Fund. (2014). (IMF multilateral policy issues report). International Monetary Fund.

- International Monetary Fund. (2020) . World economic outlook January 2020. IMF Publication.

- Jahan, S., Mahmud, A., & Papageorgiou, C. (2014). The central tenet of this school of thought is that government intervention can stabilize the economy. IMF Publication, 51(3), 53–54. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2014/09/pdf/basics.pdf

- Jayaraman, T. (2006). Macroeconomic aspects of resilience building in small states. Chapter 1. In L. Briguglio & E. Kisanga (Eds.), Building the economic resilience of small states (pp. 33–58). University of Malta and Commonwealth Secretariat.

- Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2004). Governance matters III: Governance indicators for 1996, 1998, 2000, and 2002. The World Bank Economic Review, 18(2), 253–288. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhh041

- Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2007). Governance matters VI: Governance indicators for 1996–2006. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4280. World Bank.

- Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Zoido-Lobatón, P. (1999a). Aggregating governance indicators. World Bank.

- Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Zoido-Lobatón, P. (1999b). Governance matters. World Bank.

- Knack, S. (2006). Measuring corruption in Eastern Europe and Central Asia: A critique of the cross-country indicators. World Bank.

- Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Why don’t poor countries catch up? A cross-national test of an institutional explanation. Economic Inquiry, 35(3), 590–602. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.1997.tb02035.x

- Mankiw, N., Romer, D., & Weil, D. (1992). A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(2), 407–437. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118477

- Marshall, G., Gurr, R., & Jaggers, K. (2016). POLITY™ IV PROJECT political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800-2015 dataset users’ manual (Polity IV project). Center for Systemic Peace.

- North, D. (1981). Structure and change in economic history. Cambridge University Press.

- North, D. (1990). Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

- Page, J., & Tarp, F. (2017). The practice of industrial - Government–Business coordination in Africa and East Asia. Oxford University Press.

- Prasad, B. (2003). Institutional economics and economic development—the theory of property rights, economic development, good governance and the environment. International Journal of Social Economics, 30(6), 741–762. https://doi.org/10.1108/03068290310474120

- Pritchett, L. (2006). Does learning to add up add up? The returns to schooling in aggregate data. Handbook of the economics of education (Vol. 1). Elsevier.

- Rao, B., & Singh, R. (2010). Effects of trade openness on the steady-state growth rates of selected Asian countries with an extended exogenous growth model. Applied Economics, 42(29), 3693–3702. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840802534468

- Saha, S., Gounder, R., Campbell, N., & Su, J. J. (2014). Democracy and corruption: A complex relationship. Crime, Law, and Social Change, 61(3), 287–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-013-9506-2

- Sellers, S., Ebi, K., & Hess, J. (2019). Climate change, human health, and social stability: Addressing interlinkages. Environment Health Perspectives, 127(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP4534

- Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Alfred Knopf Publisher.

- Senhadji, A. (2000). Sources of economic growth: An extensive growth accounting exercise. IMF Staff Papers, No 47/1. International Monetary Fund.

- Singh, R. (2014). Bridging the gap between growth theory and policy in Asia: An extension of the Solow growth model. IGI Global.

- Solow, R. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 71(1), 65–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/1884513

- Solow, R. (2008). The last 50 years in growth theory and the next 10. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 23(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grm004

- The United Nations. (2012). (Trade and development report – Policies for inclusive and balanced growth). The UN Publication.

- The United Nations. (2019) . Sustainable development outlook – Gathering storms and silver linings. Department of Economics and Social Affairs, UN Publication.

- The World Bank. (2000). Reforming public institutions and strengthening governance (A World bank strategy). 20433. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / THE WORLD BANK.

- The World Bank. (2007). (A decade of measuring the quality governance—Governance matters 2007: Worldwide governance indicators, 1996–2006: Annual indicators and underlying data). The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank.

- The World Bank. (2013). Rethinking the role of the state in finance (Global Finance development report). World Bank.

- The World Bank. (2019). East Asia and Pacific: Growth slows as trade tensions and global uncertainties intensify. Press Release.

- The World Bank. (2016). Worldwide Governance Indicators at URL https://databank.worldbank.org/source/worldwide-governance-indicators

- The World Trade Organization. (2019). Aid for trade global review 2019. WTO Publication.

- Thomas, M. (2009). What do the worldwide governance indicators measure. European Journal of Development Research, 22(1), 31–54. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2009.32

- Tisdell, C. (2014). The MIRAB model of small island economies in the pacific and their security issues: Revised version. Social economics, policy and development. Working Papers 165087. University of Queensland.