?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Foreign aid is one source of physical capital accumulation in Ethiopia. It is also a main media of government revenue in meeting increasing trends of government expenditure. To investigate the impact of foreign aid flow on economic growth, various empirical studies were conducted, but they came up with mixed result. This leads to raise question of why impact of aid on economic growth in Ethiopia continues to be paradoxical in its findings. To assess the effectiveness of foreign aid in Ethiopia; this study sets predictability of foreign aid and economic growth in Ethiopia as a general objective. Specifically, the study sought to examine the contribution of foreign aid and the macroeconomic policy environment to economic growth in the country. In order to meet the aforementioned objective, the study employed an autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) approach over the period 1985–2019. The empirical finding shows that foreign aid has a positive role in economic growth in the long run but its short run effect is found to be insignificant. Again, this finding also reveals that both in the short run and long run the predictability of foreign aid has a positive effect both on economic growth. Macroeconomic policy index also has a positive effect in the long run, but its short run effect become negative. Based on the listed empirical finding, the study came up with policy recommendation; the government should allocate the external assistance on the successful development projects rather than simply on consumption. Furthermore, for the persistent and predictable flow of foreign aid overtime, joint mechanism of transparency has to be developed between Ethiopian government and donor communities.

Introduction

It is widely accepted that domestic capital accumulation is needed to promote economic growth in developing countries. However, it is insufficient. Foreign aid therefore becomes one potential external source of capital that is expected to significantly boost economic growth in developing countries. Accordingly, the debate on the relationship between foreign aid and economic growth has been greatly heightened for decades. Although economic theories are fairly consistent with respect to the pivotal role of aid in spurring growth, the empirical evidence has remained controversial. While some studies have found the significantly positive relationship between foreign aid and final economic outcomes (e.g., Clemens et al., Citation2012; Galiani et al., Citation2016; Juselius et al., Citation2014), others have reached to the conclusion of insignificant or even significantly negative relation between aid and growth (Adeyemi et al., Citation2014; Dreher & Langlotz, Citation2017; Mitra & Hossain, Citation2013). For example, Liew et al. (Citation2012) concluded that foreign aid had a significant negative impact on economic growth in eastern African countries.

Kirikkaleli et al. (Citation2021) investigated whether foreign aid fostered economic growth in Chad by employing ARDL, FAMOLS and DOLS techniques from the year 1982 to 2018. The finding of the study showed that foreign aid had no impact on GDP growth in the country. In contrary, export and import has a positive and significant impact on economic growth. According to the authors, the reason for insignificant role of external assistance is that the nation spent aid on consumption that doesn’t have any contribution to enhance economic growth. Furthermore, the study was adopting a wavelet coherence technique in order to explore the association between economic growth and the determinate variables under the study. Thus, the outcome implied that though foreign aid and economic growth had a positive correlation between the years 1983 to 1986; but the study reported that there was not association among the two variables between 1990 and 2015.

On the other study, A.k (Citation2021) analyzed the effectiveness of foreign aid on economic growth from 1996 to 2018 in South Asian countries. The study utilized a Panel Fully Modified Square model to assess the relationship between foreign aid and economic growth. The study found that foreign aid has a positive association with economic growth both in the short run and long run period. Similarly, the study of Azam and Feng (Citation2022) investigated the impact of foreign aid and economic growth of 37 developing countries by taking a sample of low income, lower middle income, and upper middle income countries from 1985 to 2018. According to the outcome of the result, foreign aid enhanced economic growth in the overall level. In a disaggregated level, for lower income countries, foreign aid has a positive effect on economic growth; but it has no role on economic growth for upper middle income countries; and limited impact in low income countries.

Employing different approach,Tosun et.al (Citation2020) investigated the factors that played a crucial role for the effectiveness of foreign aid to accelerate economic growth in Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). According to the authors, while foreign aid is an important source of financing development, but the nation has not been utilized the opportunity; and this external assistance could not bring the expected achievement. Thus, the study would prioritize to identify the drawbacks factors to the effectiveness of foreign aid for TRNC. Through rigorous works the study identified about 21 factors from various literatures and they assigned a score for each of the factors. To determine whether these factors also determine the effectiveness foreign aid in TRNC; the authors developed questionnaires and conducted a survey; and then they selected and collected from 50 respondents who had a direct role on the efficiency of foreign aid. On their investigation, taking the response of the participant, 16 factors of 21 were strongly determined the effectiveness external assistance; and on their conclusion, convenient climate should be needed prior to the use of foreign aid for its effectiveness in TRNC.

While a rising concern was perceptible about the problems raised by volatility, several recent papers, followed by more official documents and political declarations, have underlined the problem induced by aid volatility (Neanidis and Varvarigos (Citation2009), Markandya et al. (Citation2010), Aldashev and Verardi (Citation2012), Kathavate and Mallik (Citation2012), Kodama (Citation2012), and Museru et al. (Citation2014)) if aid is volatile, it may contribute to macroeconomic instability, and then be itself a factor of vulnerability. This concern has been reinforced by the prospect of an acceleration of disbursements in order to achieve the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

On the other side, the international community has adopted the concept of the “predictability of aid” through the Paris declaration Wood e.al (Citation2011) aid effectiveness in which donors committed to providing “better aid” for the purpose of MDGs’ attainment. As pointed by Bacarreza-Canavire et al. (Citation2015), when foreign aid is predictable, it has a significant role to enable appropriate macro-economic management; but if it is not, the effectiveness of foreign aid to enhance the socio-economic development of recipient countries would be in doubt. Low predictability, by contrast, is costly by requiring adjustments to government consumption and investment plans with potential harmful effects on the objective attached to the spending of aid resources.

It is a general consensus among scholars that volatile and unpredictable aid flows impair the effectiveness of foreign aid in promoting the economic and social development of recipient countries. Mansoor et al. (Citation2018) empirically concluded that volatile aid inflows hamper the positive effects of macroeconomic policies and adversely affect economic growth. Kodama (Citation2012) concurs showing that unpredictability “significantly damages aid’s growth-enhancing effect.” Kodama (Citation2012) also underscores the point made earlier by Celasun and Walliser (Citation2008) that both aid shortfalls and windfalls tend to undermine macroeconomic management in the recipient countries. Ltd (Citation2011) concludes from detailed country studies that “the characteristic unpredictability of aid has serious costs at all levels of public finance management and therefore for development results.” Bulír and Hamann (Citation2008) argue that it is mainly in poor, aid-dependent recipient countries that volatile aid has adverse macroeconomic effects. However, this claim is disputed by Hudson and Mosley (Citation2008).

The debate seems to be mainly driven by the results from cross-country regression analyses, whilst there have been few studies that adopt specific-country approach to investigate the impact of aid volatility on economic growth. However, aid effectiveness is diverse across countries. Although cross-country empirical analyses have progressively developed and enormously contributed to understanding of aid-growth link, there is clear need for country case studies to capture country-specific heterogeneous features. Hence, this study makes a contribution to the less researched country-level literature on aid unpredictability. A very striking feature of aid flows is that they are highly volatile (see, see, Desai & and, Citation2011). Though in the long run, on average, aid volatility has a negative association with real economic growth of recipient countries; however, the adverse impact is even severe and stronger for sub Saharan African countries (Markandya et al. Citation2010).

In Ethiopia the government is the main source of the budget deficit. The inadequacy of the domestic economy to expand domestic revenue sources to finance the deficit by itself also makes inflows of foreign capital an important source to mitigate the challenge. Thus, the presence of these resource gaps in one way or another shows that the domestic economy is not capable of generating enough finance to close these gaps and make the country’s reliance on foreign capital inflow compulsory.

This paper is intended as a contribution to the literature on the predictability of aid and economic growth. The study will draw attention to the potential importance of a previously neglected factor, namely that aid receipts (and capital inflows more generally) volatility and its impact on growth. As capital inflows are important determinants of investment decisions, their volatility may in turn influences growth. Similarly, aid is an important component of government revenues therefore volatility of receipts may impact on fiscal behaviour that in turn may influence growth. Thus, this study investigated whether uncertainty associated with (volatility or instability of) the level of aid inflows affects the impact of aid on growth.

The significance of this study rests on informing public mandate towards foreign aid predictability-economic growth nexus in Ethiopia and give glimpse of ideas on debates surrounding the mixed results from empirical literature on the contribution of foreign aid towards economic growth in Ethiopia. Policy recommendations from this finding thereof are of great importance in as far as on effectiveness of foreign aid in spurring economic growth in the country. Moreover for researchers with interest on effectiveness of foreign aid, this research will give a connotation in further analyzing the required the institutional and political set up on the operation of government. As commonly known aid is a back bone of the Ethiopian economy, therefore the expected outcome from this study could also be useful in improving policy design, institutional setup, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of foreign aid.

1. Brief literature review on aid predictability and foreign aid on economic growth

A higher unpredictability of aid flow can potentially escalate corruption in recipient countries through increased incentives from political leaders that are risk averse and corrupt, to engage in rent seeking activities (see for example, Kangoye, Citation2011). Agnor (Citation2016) empirically investigated that aid volatility has an adverse effect on economic growth. In the same manner, Kodama (Citation2012) found that the effect of aid unpredictability on economic growth is significant and results in a waste of one-fifth of the aid. To sum up, Agénor and Aizenman (Citation2010) found that the lack of predictability in aid disbursements (especially project aid) may adversely affect growth because it makes it difficult for recipient governments to formulate medium-term investment spending plans.

Meanwhile, evidence shows that donor countries do not honor their aid commitments (see for example, Celasun & Walliser, Citation2008; Chervin & Wijnbergen, Citation2009; Desai & and, Citation2011). In addition, external and domestic shocks affecting donors in their host countries (usually developed countries) can lead to a sudden decrease in the remittances sent. In such circumstances, the public finances in developing countries could be severely affected and prompt the interested countries to adopt fiscal consolidation measures.

The finding of Markandya et al. (Citation2010) showed that aid unpredictability is more prevalent and stronger in poor countries specifically in Sub-Saharan Countries is therefore not surprising. Aldashev and Verardi (Citation2012) depicted that doubling aid volatility causes a fall in GDP growth of a typical beneficiary country by two-thirds. This effect mainly operates through the increase in violent conflict and displacement of the production in the economy towards less advanced sectors. On the other hand, Hudson (Citation2015) has examined the effects of aid and aid volatility on specific sectors using database of 50 sectors from the OECD Creditor Reporting System. He found that when debt and humanitarian aid are ignored, the most volatile sectors are linked to government and industry but other social sectors including health and education have low volatilities.

Aid unpredictability in general would hurt the recipient’s ability to plan and effectively execute investments financed through such funds. Such occurrence would necessitate a re-organization of the recipient’s consumption plans particularly if the activities that were meant to be funded by donor funds cannot be postponed. This may negatively affect growth. Ojiambo et al. (Citation2015) made a similar suggestion by considering a specific country case of Kenya. The Authors stated that increase in aid inflow variability may reduce economic growth. Studies (Chauvet & Guillaumont, Citation2008; Mansoor et al., Citation2018) have examined the issue of aid volatility arguing that it may contribute to macroeconomic instability. According to Kodama (Citation2012), the effect of aid unpredictability on economic growth is significant and results in a waste of one-fifth of the aid.

The volatility of aid may have a significant role to determine the effectiveness of foreign aid on economic growth in the developing countries. Museru et al. (Citation2014) for instance, tried to analyzed effectiveness of foreign aid by examining though the impact of the volatility of aid on economic growth in 26 Sub Saharan Africa countries over the period from 1992 to 2011. Using the Generalized Method of Moment (GMM) and averaged data for five four-year sub-periods, the authors found that foreign aid has a positive impact on growth; however the volatility of aid flow negatively related to growth in SSA and also it has an adverse effect the effectiveness of foreign aid.

Dozens of Studies on impact of aid in Ethiopia economic growth shows that aid has come up with conflicting impact on the Economic growth. For instance, Girma (Citation2015) found that foreign aid has negative contribution on RGDP growth both in short run and long run in Ethiopia. According to the author, in the long-run and short run on average, a one percentage increase in the aid-to-RGDP ratio leads to a decrease in RGDP growth by about 0.65 % and 0.28% respectively, other variables being constant. In addition, Girma (Citation2015) showed that Foreign aid interacted with policy index has positive coefficient showing that the effectiveness of aid depends on macroeconomic policy.

In similar studies such as Ejigu (Citation2015) examined the effect of foreign aid on economic growth in Ethiopia over the period of 1980/81 to 2013/14 using multivariate co-integration analysis. Thus, the author found that foreign aid has a significant positive effect on economic growth. Tadesse et al. (Citation2011) also found that aid contributed positively to economic growth in the long run, but its short run effect appeared insignificant. In the contrary, when aid is interacted with policy, the growth impact of aid is negative implying the deleterious impact of bad policies on growth in the long run. Aid squared, unlike the theoretical view, has got a positive sign, pointing the absence of capacity constraint in the flow of aid to Ethiopia. Indeed, this call for a deeper investigation and further research on the absorptive capacity of the country regarding aid flow. This raises the question of why impact of aid on economic growth in Ethiopia continues to be with paradoxical findings and relationships. The main purpose of this paper is however, to investigate and examine the inconsistency in findings and solve intellectual puzzles on the literature of effectiveness of aid in Ethiopia. This paper explores this question by analyzing the impact of aid unpredictability on economic growth in Ethiopia. The only literature addressing aid uncertainty in Ethiopia Tadesse’s (Tadesse et al., Citation2011) which included the uncertainty of aid in the economic growth regression. The author found that volatility of aid by creating uncertainty in the flow of aid has a negative influence on domestic capital formation. But methodologically rather than computing aid unpredictability, the author introduced expected aid flow based on autoregressive estimates. This study fills the gap in the literature by introducing the aid predictability indicator rather than proxying aid uncertainty. Therefore, this study will focus on the effects of aid flow uncertainty on economic growth in Ethiopia; as it switches from traditional measures of aid dependency to one feature of its delivery: its unpredictability.

2. Trends of economic growth performance in Ethiopia

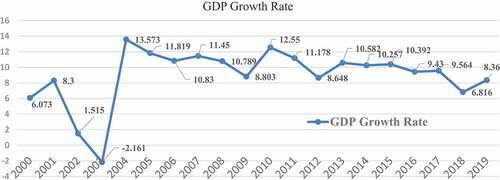

Trends in economic performances are determined by economic factors that can play a significant role in decision making of an institution about who, what and when to do a given activities in the general working of an economy. The Ethiopian economy has experienced inspiring growth performance over the last decade with average GDP growth rate of more than 10 %, which is about double of the average growth for Sub Saharan Africa (UNDP, Citation2014).

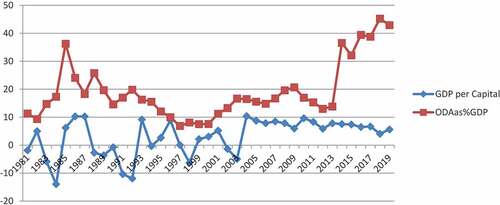

below rivals that during the first half of 1980ʹs the country’s economic growth rate showed continuous decline and even went below zero in the 1985 (which was −11.1%), this is due to fact that the country has faced a catastrophic drought and famine in the year 1984. As indicated on the figure compare to other period, the share of foreign aid to GDP in the year were the highest level (which was 36.3%), which gives a connotation that external assistance flows (in terms of food aid or other source) remain to be during occurrence of natural hazard. To sum up, as it shown from the graph above, the external assistance reached at its highest point during 2018 once again (that was around 45.2%), the reason behind this was that the new replaced administration in the ruling government launched a new economic policy that was called the home grown economy that will implemented up to 2022, due to this fact the government have got acceptance by donor countries, and this helped them to acquire additional capital from developed nations and multilateral agencies for the implementation of this new policy.

The other reason that contributed for growth rate to decline in the first half of 1980ʹs was internal political unrest and conflict in the country. Similarly, the share of foreign aid to GDP also moderately decline from 25.6 percent in 1988 to 16.9 percent in 1991. The border conflict between the Ethiopian and Eritrean government, resulted in deterioration of economic growth rate to −3.4 percent and the share of foreign aid relatively lower to 8.1 percent.

GDP growth has been successively growing over decades. However, the recent years, starting from 2018ʹs slow growth of an economy below 10percent mirrors that there is a need to make an adjustment to the of effectiveness of economic policy measures to achieve the national goal of poverty reduction strategy. However, agricultural and industrial sector growth shows promising sector for the economy to overcome the prospective economic challenges.

2.1. Role of foreign aid in economic growth

To understand the role foreign aid on GDP over the study period, the below graph gives us a clear picture:

It is clearly observed from the on average the share of foreign aid to GDP showed increasing trend from 9.3% in 1982 to 42.9% in 2019; on the other hand there is slight fluctuation in GDP per capital growth rate over time, it is also evident that there is a rising trend from 0.9% in the year 1981 to 5.6% in 2013.

Predictability of the Aid Flow

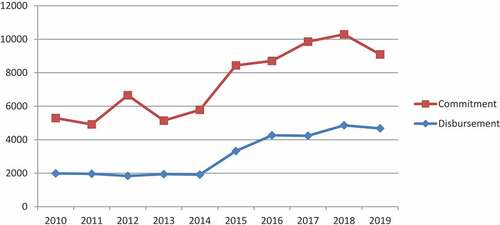

The role of foreign aid in Ethiopia’s short-run and long-run economic growth cannot be overlooked. Through passage of time the volume foreign aid flow has grown tremendously, which gives rise to an implication that an increasing country’s reliance on external assistance to achieve development goals. Taking this into account, making an in-depth investigation into the nexus between economic growth and studying the unpredictability of aid (the deviation between committed and disbursed aid) to aid dependent country like Ethiopia is of enormous important to policy makers and evidence based policy making. It is not debatable that unpredictability of aid affects country’s economic development adversely because during phases of economic planning the government may consider the commitment of aid to increase whilst the disbursement of the actual aid might reduce. . The issue of aid predictability got the expected attention during the Paris Declaration in 2005 and the Accra Agenda for Action in 2008(Holvoet, N., & Inberg, L. (Citation2009)as a factor that affect governments’ planning and budgeting processes in general, and aid effectiveness specifically.

Various studies revealed that unpredictability of aid affect public investment negatively and economic growth by undermining the effectiveness of foreign aid in aid dependent countries (see, Mansoor et al. (Citation2018), Agnor (Citation2016), and Kangoye (Citation2011). It is clear that in developing countries foreign capital inflows determine the actual investment decisions, the uncertainty of aid make the government decide to postpone even cancel the investment decision and which in-turn affects economic growth. The variability of the flow of aid also adversely affects economic policy of the recipient countries because foreign aid is one component of the countries national budget.

Alemayehu and Kibrom (Citation2011) discussed in their study, even though the net disbursement of Official Development Assistance increased from US$ 15 million in 1960 to US$ 3.8 billion in 2009, due to change in the political setup in different period the flow was not smooth.

shows that through time, the aid commitment have been higher than its disbursement in Ethiopia. The figure depicted that over the study periods both the bilateral and multilateral donors actual disbursements of Official Development Assistance were less than their commitments. This clearly provides the real picture of the flow of foreign aid in terms of commitment and disbursement in Ethiopia.

3. Theoretical Framework

The exogenous growth model developed by Solow and Swan (Citation1956) is used to investigate the nexus between predictability of aid and economic growth. The Solow growth model was originally developed to describe how growth in the capital stock, growth in the labor force, and advances in technology interact in an economy, and how they affect a nation’s total output of goods and services (Mankiw, Citation2002). The production function takes in the form of:

Where is Gross Domestic Product at time

is Physical capital stock at time

is labor force and

is Technology at time t

The Solow growth model assumes physical capital stock is the main determinant of economy’s output, through which it changed overtime and those changes can lead to economic growth. Among different factors that influence to raise capital stock in the country’s economy was investment i.e. both private and public investment (Mankiw, Citation2002). Cognizant of this fact, both private and public investment have an effect of increasing physical stock of an economy in turn contribute to gross national output positively. In this regard, public investment is financed from various sources such as tax, foreign aid or loan from external source.

Inclusion of both aid and investment variables as regressors creates a problem of double counting, as some part of investment will be funded by aid. In this regard, there is a possibility of including the aid variable and omitting the investment variable, but this has potential of causing model misspecification and a biased coefficient estimate on the variable (Feeny, Citation2005). Gomanee et al. (Citation2005) also argued that omitted investment in the growth model will cause the problem of omitted variable bias because any effect of investment on growth is attributed to the other variables (especially aid). To address the mentioned challenges in emperical studies, Gomanee et al. (Citation2005) introduced the technique of generated regressors (the mechanism of residual generated regressor) to examine the effect of non-aid financed investment in the growth model by separating from aid financed investment. On the other hand, Ojambo (Citation2009) proposed in order to address the problem of multicollinearity, public investment variable is omitted from the growth equation and instead the tax and foreign debt variables are found to be better substitutes as they formed major ways in which public investment was funded.

Hence, in this study as last time aid (i.e. concessional loan is included as ODA) will be a current period debt that create a highly correlation between aid and debt with one period lag; and has come up with the problem of functional misspecification in the estimated equation. So that in order to address this issue, the variable of foreign debt is not include in the model. Thus, the growth functional specification of equation becomes:

Where is the foreign external assistance at time

as a share of GDP,

is the total tax revenue at time

as a share of GDP,

is private investment at time

as a share of GDP

The other important variable that needs to be considered in determining the effectiveness of aid on the economic growth is macroeconomic stability. In order to capture the effect of macroeconomic stability in the model, the level of inflation, trade openness and government spending are included as good macroeconomic variables that can give a clear picture of the macroeconomic stability indicator. In their study, Burnside and Dollar (Citation1997), they stated that economic growth depends on foreign aid, investment and macroeconomic policy environment.

Inflation plays an important role in understanding the macroeconomic stability of the economy. Higher and rising inflation causes many distortions in the economy through discouraging savings, causes nominal interest rates to rise and this may affect demand for credit, thus affecting investment and economic growth negatively and it also erodes the value of financial assets. According to Burnside and Dollar (Citation1997), Burnside & Dollar (Citation2000), high inflation rates are an indication of macroeconomic instability, which is not good for foreign aid effectiveness. Thus, inflation is considered a monetary policy measure in the aid-growth debate (Burnside & Dollar, Citation1997, Citation2000). It would be assumed, therefore, that foreign aid flows would be predictable under situations of stable macroeconomic policy environment (Ojambo, Citation2009).

Foreign trade is also another variable that influences economic growth, on the other hand, increases competitiveness and provides access to enlarged markets (Balassa, Citation1978; Feder, Citation1982). Trade openness has been used as a trade policy variable in the role of macroeconomic policy environment in the aid growth relation (Burnside & Dollar, Citation1997, Citation2000; Feeny, Citation2005). An increased in the trade openness would enhance the trade relations between the recipient and donor country. It would be assumed that in such case, foreign aid flow would be predictable, arising from the increased trade flows between the countries.

The other macroeconomic variable is government spending. To capture the fiscal policy in the model, Burnside and Dollar (Citation1997) argued that budget deficit was also another good proxy. Budget deficit increases in final government consumption expenditure beyond the revenue generating capacity of the economy. In this regard, it is expected that foreign aid would play an important role in filling the financing gap arising from budget deficit. The study uses the final government consumption expenditure as a proxy for fiscal policy (Ojambo, Citation2009). Therefore fiscal policy was proxied by government final consumption expenditure (Easterly & Rebelo, Citation1993), while monetary policy was proxied by inflation (Burnside & Dollar, Citation1997, Citation2000). Trade policy was proxied by trade openness measure, which is (imports + exports)/GDP (Burnside & Dollar, Citation1997; Feeny, Citation2005).The macroeconomic policy variable was first time indexed by Burnside and Dollar (Citation1997), including inflation, trade openness and budget deficit included. The macro policy environment index (policy index) will be constructed for the study as,

Where ,

and

are the weights for inflation, final government consumption and openness, respectively.

Thus production function is as follow:

Moreover, this study introduced measurement in capital inflow uncertainty in the spirit of the works of Lensink and Morrissey (Citation2000). The Authors measured aid unpredictability by first estimating a forecasting equation so as to be able to determine the expected component of the variable under consideration. Secondly, the uncertainty (unpredictability) proxy was derived by calculating the standard deviation of the residuals from the forecasting equation. However, the study used cross-section data, and therefore, would not provide a good measure for a country specific study. For this problem, this study used a predictability indicator defined as the difference between commitments and disbursements as a percentage of disbursements (also known as the predictability per a unit of aid dollar; see, Celasun & Walliser, Citation2008). This measure of aid predictability is independent of the scale of aid as a share of GDP.

The aid predictability indicator was constructed by finding the difference between commitment and disbursement. The unpredictability of aid (predictability indicator) is defined as the difference between commitments and disbursements as a percentage of disbursements (Celasun & Walliser, Citation2008).

Where is aid predictability indicator at time t

To examine the effect of aid unpredictability in the model, aid predictability indicator (xAid) is incorporated in the model.

Then the production function is:

Where xAid (t) is aid predictability indicator and

Now, final specification of the growth model to be estimated becomes:

3.1. Data and variables

In order to conduct econometric analysis, the study used secondary data over the period 1985–2019. The sources of the data are World Bank Citation2015 and Citation2019, Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (MoFED), National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE), Organization for Economic Corporation and Development (OECD) (from OECD stat database).

3.2. Estimation technique

To examine the long-run relationship between economic growth and explanatory variables (private investment, tax revenue, foreign aid, policy index, aid predictability indicator and labor force), the study employed an autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model which was developed by M. H. Pesaran and Shin (Citation1999). below shows the describtion of variables included in ARDL estimation. Compared to other estimation techniques, ARDL approach has different advantages. First, ARDL approach is simple to apply; unlike to other cointegration techniques, once the lag order of the model is identified it’s possible to estimate the long-run relationship by OLS. Second, pre-testing of the variables for unit root test in the model is not necessarily required, it is applicable irrespective whether the underlying regressors are I(0), I(1) or mixed (H. M Pesaran et al., Citation1999). For instance, the cointegration approach by Johansen (Citation1991) and Johansen and Juselius (Citation1990) requires that variables be of the same order of integration (i.e., I(1)).

Table 1. Descriptions of variables used in the study

Third, ARDL approaches give a reliable estimate of long-run parameters and a valid t-statistics even in the presence of endogenous variables (Inder, Citation1993 as cited in Ojambo (Citation2009). Finally, in contrast to Johansen and Juselius cointegration technique, ARDL is relatively more reliable and efficient approach for small sample (see; M. H. Pesaran & Shin, Citation1999). This is the case for this study that the sample size is limited to a total of 34 observations only, this approach will be appropriate. It is also argued that using the ARDL approach avoids problems resulting from non-stationary time series data (Laurenceson & Chai, Citation2003) as cited in Bathalomew (Citation2011). The ARDL form of the growth model (lnYt) is:

3.3. Stationary properties

A time series data by its nature either has stationary or non-stationary property. It’s a rare case for time series data to become stationary in the level form (i.e I(0)). The responsiveness to shock has a significant difference among the stationary and non-stationary time series data. Effect of a shock for stationary time series is temporary and will die out gradually over time, while effects of shock for non-stationary time series persist over time and permanent. As a result, regression with non-stationary time series will lead to problem of spurious regression. Therefore, it’s important to check the stationary property of the variables before making estimation in the regression model. To avoid the above problem, the study will test the unit root test for each time series variable using Augmented Dickey-Fuller test (ADF). The ADF equation without intercept and trend gives as:

Where is a time series variables under consideration in this model at time t; Δ denotes the first difference operator;

is a random white noise error term; p is the optimal lag length.

Then the ADF equation with both intercept and trend is:

Where is the intercept; t is a time trend variable and

coefficient for time trend variable.

Now, to test stationarity of the variable, the ADF test of hypothesis is:

Against

If is rejected we simply conclude that

does not contain a unit root. Or in other word, if the t-statistics less than the critical values (t-value < C), then the null hypothesis (I.e.

) is rejected and conclude that the series is stationary and vice versa.

3.4. The auto regressive lag (ARDL) model bound testing approach

In order to conduct ARDL technique, the study utilized two steps tests (Pesaran & Pesaran, Citation1997). In the first steps, the bound test was conducted for the hypothesis of no cointegration. In this study, the null hypothesis is the coefficients of the regressors of the underlying ARDL model are jointly zero. The hypothesis of long run relationship of the variables specified as:

Against

There are two set of critical values in the bound testing result; the upper critical bound that assumes that all the series are I(1) and the lower critical bound values assume that the series are all I(0; M. H. Pesaran et al., Citation2001). If the computed F-statistic is higher than the upper critical value, then the null hypothesis of no cointegration is rejected, but if the computed F-statistics lower than the lower critical bound, then the null hypothesis of no cointegration accepted rather than rejected. In cases where the F-statistics falls inside the upper and lower bounds, a conclusive inference cannot be made. In the second step, using ARDL method the long run and short run parameters will be estimated. To obtain the optimal lag length for each variables in the model, the study will use Akaike’s Information Criteria (AIC), because of its advantages for small sample size (Tsadkan, Citation2013), this study apply the same technique. After establishing the long run relationship among the variables, the long run ARDL (p, q1, q2, q3, q4, q5, q6, q7, q8) model for Yt can be estimated as:

Where p, q1, q2, q3, q4, q5, q6, q7 are the lag lengths for each of the variables.

The short-run error correction model also specified as follow:

Where δ1, δ2, δ3, δ4, δ5, δ6, δ7are the short-run dynamic coefficients of the model’s convergence to equilibrium, and π is the speed of adjustment to long-run equilibrium following a shock to the system.

3.5. Diagnostic and stability test

To be certain whether the coefficients of the estimates were consistent and could be relied up on in making economic inferences, the study has to apply diagnostic tests. Based on this, the study applied Breuch-Godfrey for serial correlation test, the Lagrange multiplier test for heteroscedasticity (ARCH), which were used on the residuals to determine the OLS assumption on the error term. The Ramsey RESET test was used for functional form, which is conducted for the correct specification of the error-term. The Jarque-Berra statistic was used for normality test, which helps to determine whether the sample data have the skewness and kurtosis matching a normal distribution.

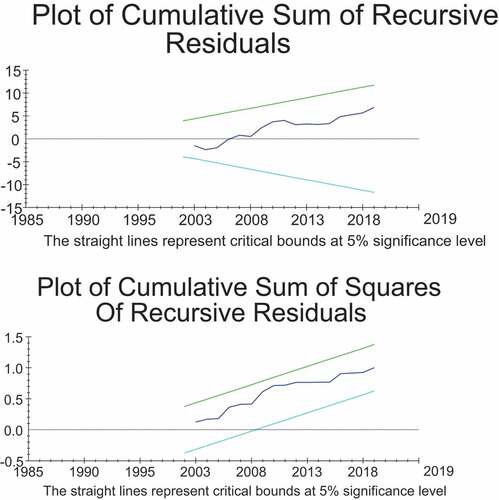

To check the stability of the long-run parameters together with the short-run movements for the model, the study used cumulative sum of squares (CUSUM) and cumulative sum squares recursive (CUSUMSQ) tests as proposed by Borensztein et al. (Citation1998). The CUSUM test is particularly important for detecting systematic changes in the regression coefficients, while the CUSUMSQ test is useful in situations where the departure from the constancy of the regression coefficients is arbitrary and sudden (Pesaran & Pesaran, Citation2009) as cited in Ojambo (Citation2009).

4. Empirical results and discussion

4.1. Unit root test analysis

Before conducting ARDL cointegration test, first it is recommended to conduct test for the stationarity status of the given time series data to determine their order of integration. A unit root test is carried out using Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test for each variable in the model. In order to apply ARDL approach and to avoid spurious results, all the variables used in the regression model should not be stationary at an integrated of order two (I(2), because the computed F-statistics provided by M. H. Pesaran et al. (Citation2001) are valid only when the variables are I(0) or I(1). Therefore, Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test was conduct and its result is presented in below. The below unit root test results clearly show all the variables are stationary on the I(0) and I(1) and but not on I(2).This gives a clue to meet the basic requirements in applying ARDL model due to fact that the order of integration of the time series is not I(2).

Table 2. Unit root test (augmented dickey-fuller test)

As indicated in the above unit root test result, real per capital income (LnY), foreign aid(LnAid), Tax revenue (LnTax), Labor force (LnLF) and Macroeconomic policy environment (LnPolicy) are integrated of order 0ne (I.e. I(1)) while Private investment (LnPinv) and foreign aid predictability indicator(LnXaid) are integrated of order zero (I(0)) with Intercept . On the other hand, with intercept and trend real per capital income, private investment, foreign aid, tax revenue and labor force are stationary in first difference and aid predictability indicator and macroeconomic policy environment are stationary at level.

4.2. Diagnostic and model stability analysis

After checking the stationarity of the variables, standard property of the model is tested through diagnostic and model stability test. In order to check the diagnostic test for this study, we applied tests such as Serial correlation test (Breusch & Godfrey LM test), Functional form (Ramsey’s RESET) test, Normality (Jaque-Bera test), and Heteroscedasticity test. In order to reject or accept the null hypothesis, we can decide by looking the p-values associated with the test statistics. That is the null hypothesis is rejected when the p-value are smaller than the standard significance level (I.e. 5%) . Presents the summary of the diagnostic tests of the estimated ARDL model of the study. The p-value associated with both LM version and F version of the diagnostic test statistics is above the standard critical value (its above 5 percent). Therefore, it is possible to conclude that the ARDL cointegration model of the study passes all the diagnostic tests (which include serial correlation, functional form, normality and heteroscedasticity).

Table 3. Short run and long run ARDL estimation result

To check whether the long run relationship are stable over the study period, the study employed the cumulative sum of recursive residual (CUSUM) and the cumulative sum of squares of recursive residuals (CUSUMSQ) to test whether the model is stable or not for the entire study period, which was proposed by Brown et al. (Citation1975). If the plot of the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ stays within the 5 percent critical bound the null hypothesis that all coefficients are stable cannot be rejected. If however, either of the parallel lines are crossed then the null hypothesis (of parameter stability) is rejected at the 5 percent significance level.

As shown from the above , the plot of CUSUM stays within the critical 5 percent bound for all equations, and CUSUMSQ statistics does not exceed the critical boundaries that confirms the long-run relationships between the economic growth and the explanatory variables, thus we can able to conclude that the parameters of the model do not suffer from any structural instability over the study period.

4.3. Long Run ARDL bounds tests for co-integration

The study employed Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) bounds testing approach to examine whether there is a long run relationship among the variables. Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) with a maximum of two lag length was selected (see, M. H. Pesaran & Shin, Citation1999; Narayan, Citation2004). Selection of AIC as an appropriate lag length selection criteria for the study is because of that it used as a better optimal lag length selection for small sample size data, and additionally AIC also produce the least probability of under estimation among all criteria available (Liew & Khimsen, Citation2004) as cited in Tsadkan (Citation2013).

The joint significance of the coefficients is performed by F-test through the bound test. This test is conducted by imposing restrictions on the estimated long-run coefficients of real per capital income, private investment, foreign aid, aid predictability indicator, tax revenue, policy index and labor force. The computed F-statistic value is compared with the lower bound and upper bound critical values provided by M. H. Pesaran et al. (Citation2001) and Narayan (Citation2004).

reveal that the calculated F-statistic (6.422938) was higher than the upper bound critical value at 1 percent level of significance using intercept only. Thus, the null hypothesis of no long-run cointegration between the variables is rejected, without taking into consideration the order of their integration implying that there was a long-run relationship between the variables.

4.4. Long run ARDL model estimation

Once we are checking long run cointegration among the variables, and then it is good to estimate the ARDL model to find out the long run coefficients. The results of the long-run estimations of the growth model presented in , which presents the summary of estimated results of the long run growth model in the regression with respect to their significant levels. As shown from the growth model, government tax revenue, foreign aid flow, foreign aid predictability and macroeconomic policy environment have a positive contribution on the economic growth in Ethiopia and on the other hand, private investment has a positive but insignificant effect and labor force has a negative impact.

The result in , shows that elasticity of foreign aid has a positive and statistically significant effect on economic growth in the long run at 1 percent level of significant. This implies that by holding other things constant, a 1 percent increase in the flow of foreign aid, will lead to a 0.49212 percent increase in economic growth in the long run over the study period. Moreover, the result of this study similar to Ejigu (Citation2015) and Tadesse et al. (Citation2011) which found that in the long run foreign aid contributes positively to Ethiopian economy. In contrary, Girma (Citation2015) and Alemayehu (Citation2011) argued that the flow of foreign aid has a negative impact on economic growth in Ethiopia. At global level, the result of this study was also affirmed by other researches like Lloyd et al. (Citation2001), Bhattarai (Citation2005), Chervin and Wijnbergen (Citation2009), Ojambo (Citation2009), Bhavan et al. (Citation2010), Kargbo (Citation2012), Mitra (Citation2013), Raheem and Ogebe (Citation2014), Trinh (Citation2014), and Refaei and Sameti (Citation2015). Contrarily, some of studies by contradicted to result of the study, such as Griffin and Enos (Citation1970), Griffin and Enos (Citation1970), Gong and Zou (Citation2001), M’Amanja and Morrissey (Citation2005), Rajan and Subramanian (Citation2005), and Ogundipe et al. (Citation2014) stated that foreign aid has negative impact on the economic growth.

The result of the study also consistent with the Harro-Domar growth model and the Chenery-Strout two gap models, as they described that physical capital was a driving force for economic growth and foreign aid flow is one source of physical capital accumulation to the developing countries like Ethiopia. Therefore, foreign assistance supplemented domestic saving and financed the required investment to attain a targeted growth rate by creating employment opportunity and by allocating enough resources to the execute national development plan in the long run. The finding of the study indicates that an increase in foreign aid inflow will promote economic growth by increasing both demand for consumption and investment to upgrade technological progress by creating the ability to import capital goods.

The above result in shows that over the study period private investment has a positive effect on economic growth but statistically insignificant. This may be due to the significant flow of external assistance will contribute to an increase in public investment and this create a crowding out effect on private investment.

As it is mirrored in the result, the coefficient of aid predictability indicator which is measured by the difference between commitments and disbursements as a ratio of disbursements has a positive effect on economic growth and it is statistically significant at 1 percent. It is found that a 1 per cent increase in aid predictability led to a 0.18405 percent increase on the economic growth in Ethiopia. The possible reason for positive effect of aid predictability may be as it is indicated in the descriptive analysis the relatively predictability of aid and variation in flow of aid is small over the study period. This is in line with the suggestion of Alemayehu and Kibrom (Citation2011); compared to other Africa countries, Ethiopia has received moderately a predictable Official Development Assistance.

The possible reason for the positive contribution of aid predictability on the economic growth perhaps related repeatedly heralded economic success stories of Ethiopia which gives donors countries a confidence to increase their commitments of aid flow to the country. This implies the current successive economic growth of Ethiopia provides the correct signal to the donor communities to provide necessary amount of resources to the country for achieving the growth target set by the policy makers in the long run. This is consistent with the Paris Declaration (2005) and the Accra Agenda for Action (2008) that donor countries agreed that predictability of aid raised governments’ planning and budgeting processes as well as aid effectiveness specifically.

The finding on impact of aid predictability of this study similar to other studies on this topic for instance: Ojambo (Citation2009), Lensink and Morrissey (Citation2000), Djankov et al. (Citation2006), Neanidis and Varvarigos (Citation2009), Chervin and Wijnbergen (Citation2009), and Kodama (Citation2012). According to these studies aid unpredictability in developing countries undermine the effectiveness of aid and has a negative impact on economic growth through its adverse effect on fiscal posture of government as well as contribute development programs not achievable as planned. Finding by native Ethiopian Tadesse et al. (Citation2011) also confirm that volatility of aid by creating uncertainty in the flow of aid had a negative impact on domestic capital formation.

As it is revealed from the above result table, over the study period the elasticity policy index has a positive contribution and statistically significant at 5 percent level of significance. The composite variable (policy) was constructed by weighted macro policy variables (by taking inflation, final government consumption as a percentage of GDP) to examine the status of macroeconomic policy environment of the country. Based on the result, taking other things constant a 1 percent increase in the macroeconomic policy environment leads to 0.51626 percent increase on the economic growth. Among different macro policy parameters, government consumption expenditure took the largest weight in the macroeconomic policy index (based on computation by SPSS version 20) which give rise to macro policy instability as a result of significant government budget deficit in Ethiopia. This provide strong justification for tight government macro policies, in the long run the macroeconomic policy environment become stable and it will have positive contribution on the economic growth.

Consistent with findings of IMF (Citation2001), sound macroeconomic policy environment contributes to economic growth positively. It is natural to expect that over time, there will be a better frame to macro policy environment, so that their impact to economic growth is positive. Additionally in the long run, the country’s macroeconomic policy environment improves effectiveness of foreign aid and promotes growth rate in the country. The result of the study is consistent with Burnside and Dollar (Citation1997), Durbarry et al. (Citation1998), and Chauvet and Guillaumont (Citation2004). Therefore, the finding of this study suggests that the elasticity of macroeconomic policy environment to economic growth is positive and statistically significant.

Moreover, the result of this study also revealed that the elasticity of tax revenue has a positive contribution to economic growth and statistically significant at 5 percent level of significance. This implied that a 1 percent increase in the level of government tax revenue leads to a 0.55105 percent increase in economic growth. This may due to that non distortionary tax revenue such as tax on imports will have a positive contribution to economic growth as this tax are taken as incentive to domestic investment and strengthen the import substitution macro policy.

Government tax revenue will also have a positive contribution to gross domestic physical capital accumulation and provision of finance to public investment for enhancing economic growth. This finding is consistent with the finding of Medee and Nenbee (Citation2011), Ogbonna and Appah (Citation2012), and Ihendinihu et al. (Citation2014). To the reverse, the result of the study contradicted with the findings of Srithongrung and Juárez (Citation2015), who suggested that government tax revenue has a negative short run and long run impact on economic growth in Mexico. Therefore, the government should expand the tax base system, build strong institution to fight corruption and minimize wastage in the use of tax revenue through appropriate legislative adjustments and financial discipline in governance.

As shown from result . The elasticity of labor force has a negative and statistically significant impact on the economic growth at 5 percent level of significant. The finding shows that a 1 percent increase in the share of labor will lead to decrease the growth rate by 4.8931 percent. This negative and statistical significant relationship between labor force and economic growth due to the combined effect associated with increasing demographic pressure in the economy and a rising nature of disguised unemployment of the labor force. This is further implied by the fact that agriculture is the main stay of the economy and takes the predominant share in employment of labor opportunity without growth of total productivity leads the contribution of labor force negative. This result is consistent with the finding of Belloumi (Citation2012) and in contrary Alemayehu et al. (Citation2002) concluded that labor force had a strong contribution to economic growth both in the short and long run in Ethiopia.

4.5. Short run error correction model

The short run dynamic coefficient estimation was obtained from estimation of the Error-Correction Model (ECM). The error correction term (ECM) indicates the speed of adjustment to restore equilibrium in the dynamic model. It is a one lagged period residual obtained from the estimated dynamic long run model. The coefficient of the error correction term indicates how quickly variables converge to equilibrium and it should have a negative sign and statistically significant (i.e. p-value should be less than 0.05).

As presented in the above error correction model table, the error correction term is strongly significant and its coefficient (ecm-1) is −.25046, which implies that the deviation from the long-term in economic growth is corrected by 25 percent in the next year. As cited in Ojambo (Citation2009), Bannerjee et al. (Citation1998) stated that a highly significant error-correction term was a further evidence of the existence of a stable long-run relationship. De Boef and Granato (Citation2000) additionally noted that an ECM is of great relevance in the estimation of the aid-growth relationship as the short-run change is necessary to maintain the long-run relationship. In the short run error correction model, about 85 percent of variation in real per capital income explained by the explanatory variables in the model. This implied that the regressors highly explained real per capital income (the dependent variable).

The result . Presents that consistent to the long run cointegration result both government tax revenue and predictability of aid have a positive and statistical significant contribution to economic growth in the short run at 5 percent level of significant. This implies that a 1 percent increase in the tax revenue and aid predictability indicator will result a 0.13802 and 0.024176 percent increase in economic growth rate in the short run, respectively.

Indicated in the above result table, contrary to its long run result the macroeconomic policy environment and its lagged variable has a negative and statistically significant impact at 5 percent and 1 percent to economic growth in the short run, respectively. As a result, a 1 percent increase in the instability of the macroeconomic policy environment and its lag variable deteriorates the economic growth by 0.13343 and 0.24652 percent in the short run, respectively. This instability of macroeconomic policy may create policy inconsistency and poor institutional framework that discourage private sectors to invest in the country. As shown from the short run model, instability of macroeconomic policy also has an adverse effect to aid growth relationship. As a result, in the short run bad macroeconomic policy become a challenge to economic growth.

On the other hand, in the short run foreign aid and labor force has no contribution to the economic growth, which is different from the long run result. However, one period lagged variable of foreign aid has a negative and statistically significant to economic growth at 5 percent level of significance. The finding shows that a 1 percent increase in the disbursed volume of aid will adversely affect the economic growth rate by 0.073723 percent in the short run. In the short run, foreign aid may simply rises government spending on nonproductive sector and it simply increase the size of government which doesn’t do nothing to support investment or economic growth; and the economy may suffer from absorptive capacity and fungibility of aid.

5. Conclusion

Similar to other developing countries, physical domestic capital accumulation has a pivotal role to lifting up economic growth in Ethiopia. Due to domestic resources gap, the country obliged to look for external source of capital in terms foreign aid to enhance economic growth. There are several empirical studies that are undertaken to analyze the nexus between foreign aid and economic growth in Ethiopia; but they came up with different results. Some of the studies concluded that foreign aid has a positive and significant effect on economic growth, while the other showed that foreign aid has a negative impact on economic growth. This enables to raise question of why impact of aid on economic growth in Ethiopia continues to come up with paradoxical findings. To investigate and examine the inconsistency in findings in the literature of effectiveness of aid in Ethiopia; this study aims at exploring this question by analyzing the the nexus between aid unpredictability and economic growth in Ethiopia. In addition, study also examined the contribution of foreign aid and the macroeconomic policy environment to economic growth in the country.

In order to examine the long run and short run economic growth model, the study applied an autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) approach over the period 1985–2019. This is because that ARDL gives reliable estimates even if in the presence of endogenous variables; It’s possible to apply whether the regressors are I(0), I(1) or mixed; it is relatively more reliable and efficient for small size sample, which is the case for this study.

The empirical finding of the study revealed that in the long run, foreign aid flow has a positive and strongly significant contribution to economic growth in Ethiopia . This implies that by raising the level of domestic physical capital accumulation and financing investment, foreign aid promotes economic growth in the long run. This requires government to introduce mechanism of promoting and easing cost of doing business for the private sector which is expected to employ the largest section of labor force in the economy. Result from the study also shows that aid predictability indicator has a positive and statistically significant result on economic growth in the long run as well as in the short run in Ethiopia. The positive effect of aid predictability may be due to the potential effect of small variation in flow aid to the country over the study period (i.e. commitment vs disbursement) in moderate term, contributing to the repeatedly heralded economic success stories of the country may give donor countries a confidence to increase their commitments of aid flow to the country in the long run.

Macroeconomic policy environment and tax revenue also the other variables that have a positive and statistically significant effect on the economic growth. This has an important implication that good macroeconomic policy environment is important for the effectiveness of foreign aid and stability of aid flow to the country as well. The positive contribution of tax revenue to economic growth emanates perhaps from non-distortionary component of tax revenue such as tax on imports, which is expected to influence the country’s economy positively and strengthen the import substitution macro policy in particular. During the study period, labor force has a negative and statistically significant impact to economic growth in the long run. This may be because of the primary and traditional sector i.e agriculture is the main stay of the economy and takes the predominant share in employment of labor opportunity which may give rise to negative contribution of labor force to the economy.

It is also confirmed that predictability of aid play a significant role for effectiveness of foreign aid as well as economic growth in Ethiopia. To make the flow of aid more predictable and persistent over time, both the government of Ethiopia and the donor communities should come up mechanism of transparently working jointly. From the government side, government of Ethiopia should create a smooth socio-political and economic relation with the donor countries so that donors will meet their commitments. From donors’ side, there should be more transparent in the allocation of aid and should also introduce proper timing in informing Ethiopian government in the event of inconsistency i.e. where there is possibility that the committed aid will not disbursed.

5.1. Policy implication

Based on the empirical findings, the study provides credible policy implication to the government of Ethiopia as well as the donor communities to formulate and implement policies.

The empirical finding of the study revealed that in the long run, foreign aid is an important component for Ethiopian economy. Therefore to enhance the contribution of external assistance, the government of Ethiopia should allocate on the successful development projects rather than simply on consumption and spending this resources properly without wastage. Further, the government should build strong absorptive capacity and install proper monitoring and evaluation mechanisms for effectiveness of foreign aid.

Macroeconomic policy environment is major important component for effectiveness of aid in turn contributing positively to promote economic growth. The macroeconomic policy should gear towards stable and sustainable macroeconomic policy environment. This will also results in stimulating domestic saving and encouraging private investment by allocating the required finance. To maintain stable macroeconomic policy, the government should develop instruments of both prudent fiscal and monetary policy to control the level of inflation.

The study also found that tax revenue was important to enhance economic growth both in the short and long run. Tax revenue have a crucial role by financing domestic investment demand to reduce the country’s aid dependency in the long run. Therefore, the government should expand the tax base, build strong institution that can combat fraud and corruption in the tax allocation process and minimize wastage in the use of tax revenue through appropriate legislative adjustments and financial discipline in governance.

Authors’ contributions

The authors contribute to the drafting of all sections of the paper. This paper is also part of term paper of Tewodros Girma, and Solomon Tilahun Department of Economics, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia.

Acknowledgements

This paper represents the personal opinions of individual staff member and is not meant to represent the position or opinions of the respective institute or its members, nor the official position of any staff members. Any errors or omissions are the fault of the authors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability statement

Data and material would be made available upon request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- A.k, D. (2021). Does foreign aid influence economic growth? Evidence from South Asian countries. Transitional Corporations Reviews, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/19186444.2021.1974257

- Adeyemi, A. O., Ojeaga, P., & Ogundipe, O. M. (2014). is aid really dead? Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 4(10). https://ssrn.com/abstract=2523500

- Agénor, P. R., & Aizenman, J. (2010). Aid volatility and poverty traps. Journal of Development Economics, 91(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2009.03.003

- Agnor, P. R., (2016), “Promises, promises: Aid volatility and economic growth”. Fondation pour les études et recherches sur le développement international. Policy brief No. 148

- Aldashev, G., & Verardi, V. (2012). Is aid volatility harmful? University of Namur (FUNDP) and ECARES. Preliminary draft.

- Alemayehu, G., Shimelis, A., & Weeks, J. (2002). Growth, poverty and inequality in Ethiopia: Which way for pro-poor growth? Journal of International Development, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 21(7), 947–970. https://ideas.repec.org/a/wly/jintdv/v21y2009i7p947-970.html

- Alemayehu, G. (2011). Reading on the Ethiopian economy. Addis Ababa University Press.

- Alemayehu, G., & Kibrom, T. (2011), “Official development assistance (Aid) and its effectiveness in Ethiopia”. Institute of African Economic Studies Working Paper Serious NO. A07 /2011.

- Azam, M., & Feng, Y. (2021). Does foreign aid stimulate economic growth in developing countries? Further evidence in both aggregate and disaggregated samples. Quality & Quantity, 56(2), 533–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01143-5

- Bacarreza-Canavire, G. J., Neumayer, E., & Nunnenkamp, P. (2015). Why aid is unpredictable: An empirical analysis of the gap between actual and planned aid flows. Journal of International Development, 27(4), 440–463. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3073

- Balassa, B. (1978). Exports and economic growth-further evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 5(2), 181–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3878(78)90006-8

- Banerjee, A., Dolado, J., & Mestre, R. (1998). Error-correction mechanism tests for cointegration in a single-equation framework. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 19(3), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9892.00091

- Bathalomew, D. (2011). An econometric estimation of the aggregate import demand function for Sierra Leone. Journal of Monetary and Economic Integration, 10(1).

- Belloumi, M. (2012). The relationship between Trade, FDI and economic growth in Tunisia: An application of ARDL model. Faculty of Economics and Management of Sousse, University of Sousse.

- Bhattarai, B. P. (2005). Foreign aid and growth in Nepal. The Journal of Developing Areas, 42(2),283–302. spring 2009. https://doi.org/10.1353/jda.0.0026

- Bhavan, T., Changueng, X., & Chunping, Z. (2010 October). Growth effect of aid and its volatility: An individual country study in South Asia countries. Business and Economic Horizons. 3(3), 1–9. ( 1804-1205 https://doi.org/10.15208/beh.2010.23

- Borensztein, E., Gregorio, D. J., & Lee, J. W. (1998). How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? Journal of International Economics, 45(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(97)00033-0

- Brown, R. L., Durbin, J., & Evans, J. (1975). Techniques for Testing the Constancy of Regression Relationships over Time. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological), 37(2), 149–192.

- Bulír, A., & Hamann, A. J. (2008). Volatility of development aid: From the frying pan into the fire? World Development, 36(10), 2048–2066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.02.019

- Burnside, C., & Dollar, D. (1997). Aid spurs growth – In a sound policy environment. Finance & Development, 34(4), 4–7.

- Burnside, C., & Dollar, D. (2000). Aid, Policies, and Growth. American Economic Review, 90(4), 847–868. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.4.847

- Celasun, O., & Walliser, J. (2008). Predictability of Aid: Do fickle donors undermine the predictability of aid? Economic Policy, 23(55), 545–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0327.2008.00206.x

- Chauvet, L., & Guillaumont, P. (2004), Aid and growth revisited: policy, economic vulnerability and political instability. In Annual world bank conference on developmentEconomics, Europe, 2003: Toward pro-poor policies – Aid, institutions and globalization,edited by N. Stern, B. Tungodden, & I. Kolstad, 95–110.

- Chauvet, L., & Guillaumont, P. (2008), Aid, volatility and growth revisited: policy, economic vulnerability and political instability”. Toward Pro-Poor Policies Aid, Institutions, and Globalization, 95–109.

- Chervin, M., & Wijnbergen, S. V. (2009), “Economic growth and volatility of foreign aid”. Tinbergen Institute Discussion paper. TI 2010-002/2.

- Clemens, M. A., Radelet, S., Bhavnani, R. R., & Bazzi, S. (2012). Counting chickens when they hatch: Timing and the effects of aid on growth. Economic Journal, 122(561), 590–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2011.02482.x

- De Boef, S., & Granato, J. (2000). Testing for cointegrating relationships with near-integrated data. Political Analysis, 8(1), 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pan.a029807

- Desai, R. M., & and, H. K. (2011). The Determinants of Aid Volatility. Annual International Studies Association meeting.

- Djankov, S., Montalvo, J. G., & Reynal-Querol, M. (2006). Does foreign aid help? Cato Journal, 26(1), 1–28.

- Dreher, A., & Langlotz, S. (2017), “Aid and growth: New evidence using an excludable instrument”. Center for Economic Studies & Ifo Institute Working Paper No. 5515

- Durbarry, R., Gemmell, N., & Greenaway, D. (1998). New evidence on the impact of foreign aid on economic growth. CREDIT Research Paper 98/8, University of Nottingham.

- Easterly, W. R., & Rebelo, S. T. (1993). Fiscal policy and economic growth: An empirical investigation. Journal of Monetary Economics, 32(3), 417–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(93)90025-B

- Ejigu, F. S. (2015). The impact of foreign aid on economic growth of Ethiopia (through transmission channels). International Journal of Business and Economics Research, 4(3), 121–132. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijber.20150403.15

- Feder, G. (1983). On exports and economic growth. Journal of Development Economics, 12(1/2), 59–73.

- Feeny, S. (2005, August). Impact of foreign aid on economic growth in Papua New Guinea. The Journal of Development Studies, 41(6), 1092–1117. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380500155403

- Galiani, S., Knack, S., Xu, L. C., & Zou, B. (2016), “The effect of aid on growth: Evidence from a quasi-experiment”. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper No. 22164. Cambridge.

- Girma, H. (2015). The impact of foreign aid on economic growth: Empirical evidence from Ethiopia (1974-2011) using ARDL approach. J. Res. Econ. Int. Finance, 4(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.14303/jrief.2014.044

- Gomanee, K., Girma, S., & Morrissey, O. (2005). Aid and growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: Accounting for transmission mechanisms. Journal of International Development, 17(8), 1055–1075. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1259

- Gong, L., & Zou, H. F. (2001). Foreign aid reduces labor supply and capital accumulation. Review of Development Economics, 5(1), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9361.00110

- Griffin, K. (1970, May). Foreign capital, domestic savings and economic development. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, Department of Economics, University of Oxford, 32(2), 99–112.

- Griffin, K. B., & Enos, J. L. (1970). Foreign assistance: Objectives and consequences. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 18(3), 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1086/450435

- Holvoet, N., & Inberg, L. (2009). Paris Declaration and Accra Agenda for Action through a gender lens: An international perspective and the case of the Dutch Development Cooperation. In DPRN, CIDIN, HIVOS, Oxfam Novib, Ministerie Buitenlandse Zaken Nederland. Papers Expert Meeting ‘On track with Gender’(May 29th 2009). DPRN, CIDIN, HIVOS, OXFAM Novib, Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken (pp. 1–25).

- Hudson, J., & Mosley, P. (2008). Aid volatility, policy and development. World Development, 36(10), 2082–2102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.02.018

- Hudson, J. (2015). Consequences of aid volatility for macroeconomic management and aid effectiveness. World Development, 69, 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.12.010

- Ihendinihu, U. J., Jones, E., & Ibanichuka, A. E. (2014). Assessment of the long-run equilibrium relationship between tax revenue and economic growth in Nigeria: 1986 to 2012. The SIJ Transactions on Industrial, Financial & Business Management (IFBM), 2(2), 39–47.

- IMF and World Bank, (2001). “Macro-economic policy and poverty reduction; world development report”. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/exrp/macropol/eng/.

- Inder, B. (1993). Estimating long-run relationships in economics: A comparison of different approaches. Journal of Econometrics, 57(1–3), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(93)90058-D

- Johansen, S., & Juselius, K. (1990). maximum likelihood estimation and inference on cointegration - with applications to the demand for money. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 52(2), 169–2 10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.1990.mp52002003.x

- Johansen, S. (1991). Estimation and hypothesis testing of cointegrating vectors in gaussian vector autoregressive models. Econometrica, 59(6), 1551–1580. https://doi.org/10.2307/2938278

- Juselius, K., Møller, N. F., & Tarp, F. (2014). The long-run impact of foreign aid in 36 African countries: Insights from multivariate time series analysis. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 76(2), 154–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/obes.12012

- Kangoye, T. (2011). Does aid unpredictability weaken governance? New evidence from developing countries. In Working Paper Series No. 137. African Development Bank.

- Kargbo, P. M. (2012), Impact of foreign aid on economic growth in Sierra Leone. UNU-WIDER, Working Paper No. 2012/07.

- Kathavate, J., & Mallik, G. (2012). The impact of the interaction between institutional quality and aid volatility on growth: theory and evidence. Economic Modelling, 29(3), 716–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2012.01.020

- Kirikkaleli, D., Adeshola, I., & Adebayo, T. S. E. A. (2021). Do foreign aid triggers economic growth in Chad? A time series analysis. Futur Bus J7, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-021-00063-y

- Kodama, M. (2012). Aid unpredictability and economic growth. World Development, 40(2), 266–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.07.015

- Laurenceson, J., & Chai, J. C. H. (2003). Financial reform and economic development in China. Edward Elgar.

- Lensink, R., & Morrissey, O. (2000). Aid instability as a measure of uncertainty and the positive impact of aid on growth. Journal of Development Studies, 36(3), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380008422627

- Liew, V., & Khimsen, A. (2004). Which lag length selection criteria should we employ. Economic Bulletin, 3, 331–9.

- Liew, C., Masoud, R. M., & Said, S. M. (2012). The impact of foreign aid on economic growth of east African countries. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 3(12), 129–138.

- Lloyd, T., Morrissey, O., & Osei, R. (2001), Aid, exports and growth in Ghana. Centre for Research in Economic Development and International Trade, University of Nottingham, No. 01/01.

- Ltd, M. (2011), Aid predictability: Synthesis of findings and good practices, Prepared for the DAC Working Party on Aid Effectiveness –Task Team on Transparency and Predictability Volume I. http://www.oecd.org/development/effectiveness/49066202.pdf.

- M’Amanja, D., & Morrissey, O. (2005). Foreign aid, investment, and economic growth in Kenya: A time series approach. Credit Research Paper, Centre for Research in Economic Development and International Trade, University of Nottingham.

- Mankiw, G. N. (2002). Principal of economics. Thomson, 2004), P, 53

- Mansoor, S., Muhammad, J., & Mirza, A. B. (2018). Aid volatility and economic growth of Pakistan: A macroeconomic policy framework. Pakistan Business Review (PBR),20(1).

- Markandya, A., Ponczek, V., & Soonhwa, Y. (2010), What are the Links between Aid volatility and growth? The World Bank IDA Resource Mobilization Department: Policy Research Working Paper No. 5201.

- Medee, P. N., & Nenbee, S. G. (2011). Econometric analysis of the impact of fiscal policy variables on Nigeria‟s economic growth (1970-2009). International Journal of Economic Development, Research and Investment, 2(1), 171–183.

- Mitra, R. Feb 2013 (2220-6140. (2013). Foreign aid and economic growth in Cambodia. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, 5(2), 117–121.

- Mitra, R., & Hossain, S. (2013). Foreign aid and economic growth in the Philippines. Economics Bulletin, AccessEcon, 33(3), 1706–1714.

- Museru, M., Torien, F., & Gossel, S. (2014). The impact of aid and public investment volatility on economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Development, 57, 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.12.001

- Narayan, P. K. (2004),Reformulating the critical values for the bounds R statistics approach to cointegration: An application to the tourism demand model for Fiji. Discussion Papers, Department of Economics, Monash University, Australia.