?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The informal economy is a complex phenomenon present, to a large extent, in both developing and developed countries. Despite an increasing focus on the nexus between public spending and the informal economy, little is known about the moderating role of budget imbalance in this relationship. This study investigates how a budget imbalance moderates the effects of public spending on the informal economy of 32 Asian countries from 2000 to 2017. We have employed the generalized method of moments and various second-generation tests in this analysis to ensure the approach is appropriate and the findings are robust. Our results indicate that increasing public spending and budget imbalance will increase the informal economy size. Interestingly, the effect of public expenditure on the informal economy will enhance with an increase in the budget imbalance. Additionally, we also find that tax burden and economic growth contribute to the increased informal economy in Asian countries. This study also offers some useful policy implications for reducing the informal economy.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The informal economy has attracted attention from scholars and policymakers. Understanding the determinants of the informal economy is important in formulating and implementing economic policies. Public spending is generally considered an important determinant of informal economy. This study investigates the impact of public spending on informal economy with the moderating role of budget imbalance. We find that public spending and increased budget imbalance (or budget deterioration) are associated with increased informal economy. Moreover, public spending intensifies the size of the informal economy when the budget imbalance increases.

1. Introduction

The informal economy is a topic of interest among academics, policymakers, and regulators that have emerged in recent years not only in emerging markets and developing countries but also in advanced economies. The informal economy, also known as the undeclared, underground, hidden, or shadow, is a pervasive economic feature (Dell’Anno, Citation2021). As such, in this study, these terms are used interchangeably. The informal economy includes all economic activities not covered by law or formal arrangement (OECD/ILO, Citation2019). In emerging markets and developing countries, far too many people and small enterprises operate outside the line of sight of governments—in the informal sector. This sector constitutes more than 70 per cent of total employment and approximately one-third of output in these countries (Loayza, Citation2016). In terms of employment, around 62.1 per cent of the total employed population age 15 years and older, equivalent to two billion people, operate in the informal sector (ILO, Citation2018).

Interest in the informal economy partly responds to the potentially high costs they impose on inclusive economic development, especially in developing countries. A widespread informality has been associated with significantly poorer/worse governance and more significant lags in achieving every dimension of the Sustainable Development Goals. Countries with larger shadow economies tend to have less access to finance for the private sector due to tax revenue erosions, limiting their ability to enhance social inclusion (Elgin & Erturk, Citation2019), lower productivity (Loayza, Citation2018), slower capital and human capital accumulation, and smaller fiscal resources (Docquier et al., Citation2017). Moreover, the informal economy is, on average, less productive than the formal sector because it tends to hire more low-skilled workers, has more restricted access to markets and funding, and lacks economies of scale (Loayza, Citation2018). The informal economy also widens the income and poverty gap, making progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals difficult (Özgür et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, some studies show that the informal economy is associated with higher corruption (Friedman, Johnson, Kaufmann, Zoido-Lobaton et al., Citation2000; Johnson et al., Citation2000), which leads to political instability (Elbahnasawy et al., Citation2016). Nevertheless, the advantages of the informal economy are also discussed. The benefits of the informal economy are providing employment opportunities, especially in a crisis, competitive prices, promoting local economies, and an increase in income level (Hoinaru et al., Citation2020; Ruzek, Citation2015).

Academics and policymakers have long had good reasons to identify the drivers of the informal economy due to its significant role in proposing, and implementing economic policy (Elgin & Erturk, Citation2019). The determinants of informality are multifaceted. They vary from unemployment (Mauleón & Sardà, Citation2017); to the design of the tax and social security system (Hassan & Friedrich, Citation2016; Schneider, Citation2010); to the quality of institutions (Canh et al., Citation2021; Dreher & Schneider, Citation2010). However, the evolution of socio-economic structures in recent decades has raised concerns over the new augmented determinants of the informal economy. Our literature review indicates that public spending does not attract much attention from researchers in empirical studies on the informal economy. On the one hand, many studies have demonstrated that public spending impacts favourably on the informal economy (Berdiev & Saunoris, Citation2018; Xu et al., Citation2018). On the other hand, many scholars have argued that public spending has a negative or insignificant impact on the shadow economy (Baklouti & Boujelbene, Citation2019; Farzanegan et al., Citation2020). The absence of consensus among researchers on the impact of public spending on the informal economy opens the importance and necessity for further research to ascertain the nexus between these two variables, which could be attributed to different econometric methods, data, periods and countries included in these empirical studies.

Previous studies have identified factors that moderate the relationship between public spending and economic growth, such as value-added tax (Chan et al., Citation2017) and institutional quality (Khan et al., Citation2020). Such moderating effects should be investigated since the public expenditure is a multi-dimensional phenomenon of various interrelations (Christie, Citation2014). Our literature review indicates that the moderating role of budget imbalance on public spending and informal economy nexus has been largely neglected in the existing literature. However, this moderating effect should be taken into account since the effectiveness of public spending depends on the level of budget imbalance (Gemmell et al., Citation2012).

The Asian countries provide a fruitful research context to investigate this critical relationship. Many countries in Asia suffer from considerable budget deficits. At the same time, these countries endure significant country risks owing to the large informal economy, with an average informal economy size of about 28 per cent of the national GDP. Pervasive informality is particularly pernicious at the current juncture. In the global recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the informal sector has been hit hard by lockdowns and changes in consumer behaviour triggered by the pandemic. With a prominent presence in the services sector, workers in the informal economy were more likely to lose their jobs or suffer severe income losses. Moreover, informal workers are largely excluded from formal social safety nets, and government support programs often cannot reach them. Significantly, governments across Asia are unleashing massive stimulus packages to support economies heading into recession as COVID-19 affects consumption and investment.

Given the crucial role of public spending in these countries, this study makes several contributions to the existing literature on the informal economy on the following grounds. First, to the best of our knowledge, this study is one of the first of its kind to investigate the effects of public spending, budget imbalance, and the informal economy in the Asian context. Second, the impact of public expenditure on the informal economy with the moderating role of budget imbalance is still widely investigated. As such, whether an increase in budget imbalance favourably or adversely moderates the impact of public spending on the informal economy remains unanswered. Third, findings from this study provide empirical evidence for policymakers to use appropriate fiscal policy to control the informal economy.

Following this introduction, the remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents and synthesizes the literature review on the relevant issue. Section 3 presents the research methodology and data. The results are presented and discussed in section 4, followed by the concluding remarks and policy implications in section 5 of the paper.

2. Literature review

2.1. Informal economy and its measurements

The presence of the informal economy is inevitable due to the complexity of economic activities and events that cannot be fully controlled and counted by authorities. In recent years, the informal economy has attracted much attention from scholars and policymakers (Williams, Citation2019). However, there is no consistent definition of the informal economy. In the literature, the informal economy implies all economic events or activities outside the public governance and private sector establishment (Ajide, Citation2021; Hart, Citation2008). Medina and Schneider (Citation2018) consider that the shadow economy includes all hidden activities from public authorities due to regularity, monetary, or institutional purpose. For example, legal goods and services may be produced in the shadow economy but are not reported to the tax authorities to avoid paying taxes and social security contributions. This definition does not consider illegal or criminal activities, do-it-yourself, charitable, or household activities as part of the shadow economy.

The informal economy is, by nature, challenging to measure because agents engaged in the informal economy activities try to remain undetected. Despite the difficulty of measuring informality, many estimation methods have been developed to capture its scale. Elgin et al. (Citation2021) argue that twelve measures are most commonly used in the literature. These methods can be categorized into direct, indirect, and model-based approaches (Schneider & Buehn, Citation2018). The first group encompasses direct measures from surveys, such as labour force, firm and household surveys. Although this approach provides detailed information about informal activities and the structure of labour in the informality, it has limitations regarding times, countries, and short-run point estimation, resulting in lower reliability than other methods. Second, for the indirect approaches, scholars use macroeconomic indicators, including currency demand (Awad & Alazzeh, Citation2020), transactions indicators (Feige, Citation1979), and electricity consumption (Psychoyios et al., Citation2021), to infer the size of the informal economy under certain assumptions. Third, the size of the informal economy can be estimated using model-based approaches, such as the multiple indicators-multiple causes (MIMIC) method (Schneider et al., Citation2010) and the dynamic general equilibrium (DEG) method (Elgin & Oztunali, Citation2012). Among these techniques, the MIMIC and DEG model, albeit imperfect, stand out in terms of their long time-series and extensive country coverage and is widely applied in the macro empirical research about the informal economy (Kelmanson et al., Citation2019; Schneider & Buehn, Citation2018). These recent attempts of scholars to estimate the informal economy size provide a more comprehensive picture of what the informal economy is and the informal economy’s drivers to understand this phenomenon better and give some policy recommendations.

2.2. The impact of public spending and budget imbalance on the informal economy

This section is devoted to a brief review of relevant theory and empirical studies on the relationship between public spending, budget imbalance, and the informal economy. Each of these relationships is discussed in turn below.

2.2.1. Public spending and the informal economy

Understanding the determinants of the informal economy is an important issue in proposing and implementing economic policy. The causes of the informal economy can be categorized into three groups: economic, policy-related, and regulatory and institutional quality (Williams & Schneider, Citation2016). Previous empirical studies have mainly concentrated on taxation, unemployment, economic structure, and institutional quality as the leading causes of the existence of an informal economy (Friedman, Johnson, Kaufmann, Zoido-Labton et al., Citation2000; Schneider & Enste, Citation2000; Tanzi, Citation1999).

Public spending is one of the overriding pillars of fiscal policy and an important determinant of the informal economy. It plays a significant role in individuals’ decisions to stay in the formal sector or move to informality. We consider that public spending might be a key determinant for the informal economy for the following reasons. First, increased public spending is normally associated with increased taxes to overcome the budget imbalance. Such an increase in taxes and fees creates a vicious cycle of pushing more people into the shadow sector. Furthermore, an increase in government leads to the crowding-out effect, distortion of economic incentives, allocation of resources, and discourages savings, and investment, thus hindering economic growth (Barro, Citation1990; Christie, Citation2014), which in turn, encourages individuals and firms toward informal economy (Dell’Anno et al., Citation2018). Third, the growth in public spending typically comes with a heavy burden of laws, regulations, and cumbersome and costly procedures, which cause operational constraints reducing the freedom of choice to work in the formal sector. These contribute to an expansion of the informal economy because, in Legalist theory, the informal economy is a choice made by rational actors to avoid excessive government regulations (De Soto, Citation1989).

Berdiev and Saunoris (Citation2018) examine the factors affecting the shadow economies of 108 countries during the 1984–2006 periods. Their findings indicate that government expenditure has resulted in a bigger shadow economy. Furthermore, using the datasets for the 131 countries from 1999 to 2007, Xu et al. (Citation2018) confirm that public spending enlarges the size of the shadow economy. This result is consistent with the studies of Elgin and Oztunali (Citation2014), Esaku (Citation2021). Table presents a summary of selected writings on the topic. In line with the literature, the first hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1:Increased public spending leads to a rise in the informal economy.

Table 1. A summary of the selected papers concerning the effects of public spending on the informal economy

2.2.2. Budget imbalance and the informal economy

Fiscal policy plays an important role in managing economies in both developed and developing countries (Easterly & Rebelo, Citation1993). However, the impact of budget imbalance on the informal economy is unclear due to the dearth of empirical studies. The COVID-19 pandemic has precipitated large macroeconomic imbalances, exacerbated an already precarious fiscal position, and led to a loss of fiscal sustainability (Burger & Calitz, Citation2021; Makin & Layton, Citation2021) which in turn impacts the informal economy.

In the neoclassical economic theory, the budget imbalance is considered to arise from market borrowing and lending decisions in inter-temporal optimization problems (Bernheim, Citation1989). The Neoclassical theoretical view promotes that budget imbalance leads to increased lifetime consumption, reduces the saving rate, raises interest rates, and crowds out private investment. In the Neoclassical postulation, therefore, deficits can deteriorate the overall economic growth. Furthermore, the budget imbalance arises out of current account deficits, in what has become popularly known as the twin-deficit hypothesis (Kim & Roubini, Citation2008). The Modernization theory, rooted in Boeke’s (Citation1942), and Lewis’s (Citation1954) studies, postulates that the informal economy is a product of economic under-development. Thus, the informal economy has a counter-cyclical relationship with the formal economy (La Porta & Shleifer, Citation2014). It means that the informal economy may increase with the decline of the formal sector.

Moreover, the literature indicates that unsustainably high budget imbalances are associated with macroeconomic instability, especially inflation (Cebula, Citation1995). Friedman (Citation1968), Sargent and Wallace (Citation1981) presented a model where a higher imbalance of debt results in higher money growth in the current period or future and thus leads to inflation. High inflation rates bring hardship for many households, creating incentives to participate in the informal sector. Some studies found that the amplification of the inflation rate is strongly linked to the expansion of the informal economy (Baklouti & Boujelbene, Citation2019; Mazhar & Méon, Citation2017). Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2:Increased budget imbalance leads to an increased informal economy.

The literature on public finance emphasizes the crucial role of the effectiveness of public spending. However, the significance of public spending depends on the level of budget imbalance (Gemmell et al., Citation2012). In addition, the moderating role of budget imbalance in the public spending—informal economy nexus is not investigated either theoretically or empirically. Findings from previous studies indicate that public spending increases the size of the informal economy. Similarly, the budget imbalance raises the informal economy. Moreover, an interaction between public spending and budget imbalance is observed because higher spending can activate a higher budget imbalance, which multiplies the detrimental effect of public spending on the informal economy through this channel.

Hypothesis 3:The increase in budget imbalance intensifies the impact of public spending on the informal economy.

3. Methodology and data

3.1. Research model

In line with previous studies from Huynh and Nguyen (Citation2020), Khan and Rehman (Citation2022), this paper investigates the impact of public spending on the informal economy and the role of budget imbalance in moderating this impact using a sample of 32 Asian countries from 2000 to 2017. The following model is as follows:

i, t denotes country i at year t, respectively; β is the coefficient; Ɛ is the error term.

The dependent variable represents the informal economy size (IE), measured by the per cent of GDP. The regressors are public spending (PS) and budget imbalance (BI), measured by the per cent of GDP. PS*BI represents the interaction term between public spending and budget imbalance. The interaction term between public spending and budget imbalance measures the role of budget imbalance in moderating the impact of public spending on the informal economy size. This term can be calculated using a partial derivative of equation (1) concerning public spending:

The role of budget imbalance in affecting how public spending impacts the informal economy is conditioned on the two parameters: β1 and β3 in EquationEq. (2)(2)

(2) . These parameters produce four possibilities:

If β1 > 0 and β3 > 0, meaning that larger public spending will increase the informal economy size, and budget imbalance enhances and complements this positive effect.

If β1 < 0 and β3 < 0, larger public spending will decrease the informal economy size, and budget imbalance worsens this negative effect.

If β1 > 0 and β3 < 0, implying that increased public spending is linked with an increased informal economy. However, budget imbalance constitutes a reduction which leaks out the positive effect.

If β1 < 0 and β3 > 0, implying that larger public spending leads to the decrease of the informal economy, but budget imbalance mitigates and lessens the negative effect.

We note that if β1 and β3 in EquationEq. (2)(2)

(2) have different signs, it confirms the existence of the threshold effect, suggesting that the impact of public spending on the informal economy differs depending on the levels of budget imbalance.

Various studies have attempted to determine the drivers of the informal economy. To better explain this economic phenomenon, selected studies emphasize the effect of sociocultural factors on the informal economy (see, Achim et al., Citation2019; Amin & Ahmad, Citation2021). Our study focuses on economic and institutional indicators to investigate the effects of public spending on the informal economy due to the data availability. Control variables (X) include economic growth, tax burden, corruption, and rule of law. The selection of these control variables can be justified as follows:

Economic growth: The impact of economic growth on the informal sector is ambiguous (Goel et al., Citation2019). The followers of the dualist approach claim that economic growth impacts the informal economy negatively because the dualist view considers the informal economy as a residual of the official economy (La Porta & Shleifer, Citation2008, Citation2014). However, empirically, the studies of Cooray et al. (Citation2017), Blanton et al. (Citation2018) show that the informal economy is counter-cyclical to the official economy. On the contrary, according to a recent report by ILO (Citation2018) and Baklouti and Boujelbene (Citation2019) and Saunoris (Citation2018) studies, the results indicate that the informal economy is a procyclical engine of economic growth because the informal sector provides services, goods for the formal sector. In addition, informal economy income may support the demand of the official sector.

The tax burden is one of the main causes of the informal economy. Most schools of thought on the informal economy presume that tax burden positively affects the informal economy since greater tax complexity imposes heavier compliance burdens on taxpayers, disincentivizes tax compliance, and encourages taxpayers to move into the shadow sectors. Tax burden leading to a larger informal economy is found in various studies, including Mazhar and Méon (Citation2017), Wu and Schneider (Citation2019), and Kelmanson et al. (Citation2019).

Corruption: Theoretical considerations in the literature classify the relationship between corruption and informal economy as dual or ambiguous since they are found to be either complements or substitutes. The former term indicates the situation in which there is a positive relationship between the variables, while the latter term implies a negative one. Furthermore, the empirical examination of the relationship between corruption and the informal economy could be either positive (Buehn & Schneider, Citation2012; Esaku, Citation2021; Goel & Saunoris, Citation2014; Huynh & Nguyen, Citation2020) or negative in high-income countries (Dreher & Schneider, Citation2010)

The rule of law: In economic literature, the rule of law is one of the various aspects of an institution (Nguyen et al., Citation2021). A better rule of law contributes to reducing transaction costs (Hoffman et al., Citation2016) and risk (Busse & Hefeker, Citation2007), therefore, encouraging official economic activities. In addition, some studies found that a better rule of law leads to a smaller informal sector (Hayat & Rashid, Citation2020; Khan & Rehman, Citation2022).

3.2. Data

Data are collected for 32 Asian countries over the period 2000–2017. A list of countries is presented in Table . The selection of these 32 Asian countries is mainly due to data unavailability. However, data for the informal economy, public spending and budget imbalance should be sufficient for econometric analysis.

Table 2. List of countries included in the analysis

The informal economy data set is collected from Medina and Schneider’s (Citation2019) study. Medina & Schneider estimate the size of the informal economy for 157 economics from 1991 to 2017 using the MIMIC techniques at the time this analysis is conducted. Annual data on GDP growth rate and public spending (per cent of GDP) are obtained from World Development Indicators. Data on the budget imbalance are from the Fiscal Monitor of the International Monetary Fund. Additionally, the data on controlling corruption and the rule of law are collected from Worldwide Governance Indicators. Table summarises the measurement of the variables used in this paper.

Table 3. Description of variables and measurement

The descriptive statistics of the variables and the correlation matrix between the variables are presented in Tables , respectively. The largest and smallest sizes of the informal economy are 60.6 per cent and 10.31 per cent of the national GDP. The average size of the informal economy of the Asian countries is about 28 per cent of GDP. The mean value of public spending, proxied by the public spending, is 13.4816 with a standard deviation of 5.52, a minimum of 3.46, and a maximum of 30 per cent GDP. The highest level of economic growth is about 34.5, whereas the lowest level is −14.1. The mean value of control corruption is −0.047, the highest value of 2.325, and the lowest value of −1.496. Moreover, the standard deviations of the variables indicate wide variations, implying that the variables are dispersed around their means.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics

Table 5. The correlation matrix

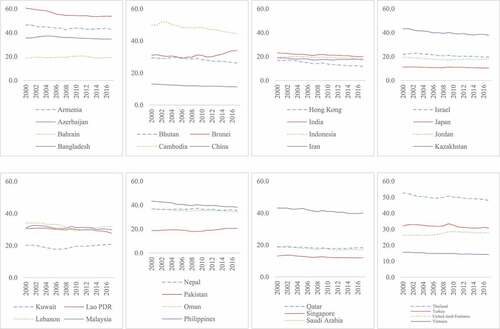

Figure presents the size of the informal economy of each country across the years. On average, Japan has the smallest informal economy size while the largest informal economy size belongs to Azerbaijan. Vietnam is one of the countries with a small size of the informal economy, which is approximately 16.5 per cent of the national economy in the region.

Table presents the correlation matrix of the concerned variable from the Asian countries. A highly negatively correlation (−0.307) is observed between public spending and the informal economy, while a highly positive correlation (0.145) exists between economic growth and the size of the informal economy. The results indicate that the estimated model does not suggest the presence of multicollinearity.

4. Empirical results and discussions

4.1. Cross-sectional dependence test

Panel data estimation strategies ignore the problems of cross-sectional dependency, which may cause bias and misleading information and unreliable results. There is a probability of possible cross-sectional dependency due to the financial, globalization, and economic integration. Therefore, it is important to examine this cross-sectional dependency problem in our analysis.

The Pesaran CD (2004) test is used to examine cross-sectional dependence in this study. The null hypothesis of this test is that there is no evidence of cross-sectional dependency. Empirical results from Table reject the null hypothesis. The presence of cross-sectional dependency in this study implies that second-generation econometric techniques should be used to produce robust and consistent results.

Table 6. Cross-section dependence test results

4.2. Slope homogeneity test

In addition to cross-sectional dependence, Breitung (Citation2001) argues that assuming panel homogeneity will mislead the results if the panel is heterogeneous. Therefore, the slope homogeneity test developed by Pesaran et al. (Citation2008) is used. The results in Table reject the null hypothesis of slope homogeneity, confirming the presence of slope heterogeneity in our data set.

Table 7. Slope homogeneity test results

4.3. Panel unit root test

The next step of the empirical investigation is to examine all variables’ integration order and stationarity level. Our empirical analysis examines the order of integration of each variable using the CIPS test (Pesaran, Citation2007). Furthermore, the CADF unit root test is used, and the results are presented in Table . The results from both tests indicate that our concerned variables are at level I(I).

Table 8. Panel unit root test results

4.4. Panel cointegration test

The cointegration is tested among the variables using three different cointegration techniques for the robustness of the results: Pedroni’s (Citation1999, Citation2004), Kao’s (Citation1999), and Westerlund’s (Citation2005) residual cointegration tests. Table presents the results of the panel cointegration test. Our results reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration and confirm a long-run relationship between public spending, budget imbalance and the informal economy.

Table 9. Results of the cointegration test

4.5. Empirical findings on the relationship between public spending, budget imbalance and informal economy

Our literature review indicates that various techniques can be used to examine the relationship between variables in a dynamic panel. Empirical methods such as fixed effects and random effects models are also highly recommended in panel data. However, these estimation techniques have limitations when data shows issues such as endogeneity and heteroskedasticity (Hansen, Citation2020). In addition, Ullah et al. (Citation2018) and Roodman (Citation2009) argue that GMM can be used to deal with three sources of endogeneity, namely, unobserved, simultaneous and dynamic endogeneity. In addition, previous studies also show that GMM can address heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation issues. The time dimension of our data is smaller than the number of groups (T < N). As such, we consider that the GMM estimator is an appropriate approach (Wooldridge, Citation2010). The GMM method uses the Arellano and Bond (Citation1991) test to examine the first-order and second-order autocorrelation via the AR (1) and AR (2). In addition, statistics from Sargan and Hansen examine the validity of the instrument variables.

As shown in Table , AR (2), Sargan and Hansen test results indicate that the autocorrelation, endogeneity, and heteroskedasticity issues do not exist. These results ensure the validity of GMM estimation. As such, we consider that the use of the GMM appears to be appropriate for this study.

Table 10. Empirical findings on the relationship between public spending, budget imbalance and informal economy using the GMM estimation techniques

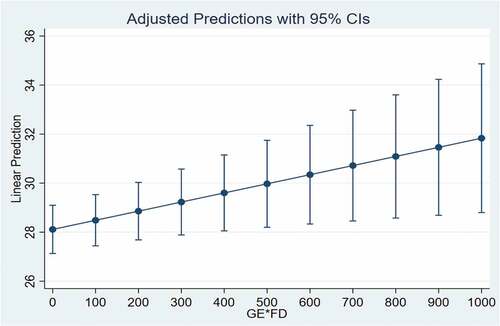

Our empirical results are reported in Table . Key findings can be summarised as follows. First, a higher level of public spending leads to a larger informal economy. More specifically, a 1 per cent increase in public spending will lead to an increase of 0.268 per cent in the informal economy. This finding supports the Legalist theory, which argues that the rise in public spending typically comes with a heavy burden of laws, regulations, and costly and cumbersome procedures (De Soto, Citation1989). All these impacts contribute to the motivation of individuals and firms to operate in the informal sector. This finding is in line with results from other studies (Berdiev & Saunoris, Citation2018; Esaku, Citation2021), which confirms a positive relationship between public spending and the size of the shadow economy. Second, our empirical findings indicate that budget imbalance is significantly and positively associated with the informal economy. These results suggest that an unregulated budget deficit is the fundamental driver of hyperinflation and macroeconomic instability, leading to an increased extent of the informal economy. Third, having dissected the different effects of public spending and budget imbalance on the informal economy in Asian countries, the coefficients of the interaction between public spending and budget imbalance (PS*BI) on the informal economy are statistically significant and positive. This finding indicates that budget imbalance enhances a positive effect of government spending on the informal economy. This finding is not recorded in the existing literature. This finding implies that, with an increased budget imbalance/deficit level, an increase in public spending is associated with an increased informal economy size (as presented in Figure ). The marginal impacts of public spending on the informal economy at the minimum, mean, and maximum levels of budget imbalance are 0.244, 0.267, and 0.311, respectively.

In addition, our findings indicate that the significant effect of economic growth on the informal economy is consistent with the theoretical framework and previous studies. The higher economic growth is associated with a larger informal economy. This finding supports a structuralist theory concerning the procyclical relationship between formal and informal economy. The informal and formal modes of production are inextricably linked within the same economic system (Chen et al., Citation2004; Dell’Anno, Citation2021). Firms in the informal sector provide services and final and intermediate goods to the formal sector. As such, a positive correlation between formal and informal sector may emerge. Furthermore, income from an informal economy can support and encourage demand from a formal economy (Dell’Anno, Citation2021). This finding is line with Baklouti and Boujelbene (Citation2019) and Saunoris (Citation2018). A higher tax burden contributes to the increase of the informal economy since a high tax rate leads economic agents to operate in the informal economy to take advantage of tax evasion. Moreover, the complicated tax system has undermined the tax base resulting in the misallocation and distortions of input and leading to the erosion of tax morality in the long run. This result is consistent with results from Wu and Schneider (Citation2019) and Kelmanson et al. (Citation2019). Nevertheless, control of corruption and the rule of law have a negative effect on the informal economy. However, the effects are insignificant.

4.6. Robustness check

Various analyses have been conducted to ensure the robustness of our empirical findings. First, we re-estimate the results using two separate samples: a sample of high vs low informal economy; a sample of high vs middle income. Second, we re-estimate our results using the alternative method. We also include an additional control variable.

First, it is interesting to re-examine the significant and positive relationship between public spending and the informal economy from different country groups. We divide the sample of countries into two groups: (i) samples including large and small sizes of the informal economy based on the mean level of each country with the mean level of the shadow economy from the whole sample; and (ii) samples of high-income and the middle-income countries based on the classifications from the World Bank. Our robust findings are presented in Tables . These findings show that the estimated coefficients of public spending, budget imbalance and interaction between public spending and budget imbalance are significant and positive. In addition, we find the negative impact of the control of corruption on the informal economy in both subsamples. This finding confirms that the control of corruption reduces the informal economy because this factor directly contributes to creating a business-friendly environment in which economic agents can operate with better protection, lower transaction cost, and less risk. This result is consistent with findings from previous studies by Medina and Schneider (Citation2018) and Canh et al. (Citation2021).

Table 11. Empirical findings from two sub-samples: a sample of large informal economy versus a sample of a small informal economy

Table 12. Empirical findings from two sub-samples: a sample of high-income countries versus a sample of the middle-income countries

Second, for the robustness analysis, our study also uses an alternative estimation method, generally known as the common correlated effect with GMM (referred to as CCE-GMM). One of the advantages of this method is to avoid potential endogeneity, cross-section dependence and the exogenous common factor dependence (Comunale, Citation2017; Zhao et al., Citation2022). Table reports the findings of our results using this CCE-GMM estimation technique. In summary, the findings of this method are largely consistent with those from the GMM approach, as previously reported in Table .

Table 13. A robust analysis using the CCE-GMM estimation

Additionally, we add an interaction term known as (economic growth * public spending * budget imbalance) to investigate the informal economy’s effects further. As presented in Table , the estimated coefficients of public spending and budget imbalance are positive and significant. These additional results are largely consistent with our main results using the GMM estimation.

Table 14. A robustness analysis using an interaction variable

5. Concluding remarks and policy recommendations

The large size of the informal economy is a major impediment to developing the economy sustainably. As such, controlling the growth of the informal economy has been a subject of discussions and debates among researchers and policymakers globally, especially in developing countries. While several studies argue that unemployment, tax burden, and weak institution have been considered the main causes of the informal economy, few studies have been conducted to investigate the relationship between public spending and the informal economy. The moderating role of budget imbalance in the relationship between public spending and the shadow economy has largely been ignored in the existing literature. As such, this study is conducted to provide empirical evidence on this important relationship

Our analysis uses a sample of 32 Asian countries from 2000 to 2017 using the GMM panel estimation. Various robustness analyses such as using different estimation techniques, sub-samples and additional control variables have also been conducted. Our results indicate that increased public spending leads to an increase in the informal economy in these 32 Asian countries. This finding supports the Legalist theory which considers that the excessive involvement of the government in the market encourages firms to divert their business into the informal sector characterized by a shorter duration, lower costs, and less bureaucratic procedure to accomplish. This result is consistent with the results from Khan and Rehman (Citation2022), and Esaku (Citation2021). Moreover, an increase in budget imbalance also leads to increased size of the informal economy. We also examine the moderating role of budget imbalance on the public spending—informal economy relationship. Interestingly, the results show that public spending intensifies the size of the informal economy when the budget imbalance increases. Furthermore, the results also demonstrate that economic growth contributes to an increased informal economy. Our results also indicate that increased taxation is a major reason behind the growth of the informal economy.

Policy implications have emerged based on these findings for the governments, policymakers, and stakeholders concerning controlling the informal economy for sustainable development. First, the governments of the Asian countries should be careful when implementing an expansionary fiscal policy. They should be aware that an increase in public spending may trigger the growth of the informal economy. This effect is significantly intensified based on a sustained significant budget imbalance. We note that policies targeting a reduction in the informal economy cannot be considered in isolation from public spending and budget imbalance policies. In addition, policymakers should consider minimizing the tax burden by systematic tax reforms because tax burden has been found to be the key driver leading to an increase in the informal economy. Supporting sustainable economic growth and development requires the governments of Asian countries to take measures to control the informal economy effectively. In summary, we advocate for a comprehensive set of policies targeting reducing the informal economy. Furthermore, we consider that policies tackling the informal economy should be considered in conjunction with other conventional policies addressing tax burden and supporting employment creation and institutional quality.

This study suffers limitations. Data unavailability is worth noting. Studies in the future may benefit from using an extended period for the estimates of the informal economy. Furthermore, our analysis is undertaken using a relatively small sample of 32 countries in Asia. Extending a sample of countries across different continents with different economic and social characteristics should be interesting for international comparison. It is very important to initiate a new theoretical framework to explain the channels through which public spending impacts the informal economy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Phuc Van Nguyen

Phuc Van Nguyen is Deputy Minister, Ministry of Education and Training in Vietnam. His research interests are entrepreneurship, economic growth and entrepreneurial environment. Professor Nguyen has widely published in North American Journal of Economics and Finance, Emerging Markets Finance and Trade; International Journal of Emerging Markets and many others.

Duc Hong Vo

Duc Hong Vo is an academic and practitioner of Applied Economics and Finance. He has more than 20 years of teaching experience in Australia and Vietnam. More than 100 papers from his research have been published in international journals, including Journal of Economic Surveys; Applied Economics, Journal of Intellectual Capital, International Journal of Finance and Economics, Journal of Asian Economics and many others. His current research interest covers the informal economy, corporate finance and governance, international finance and public finance, including the cost of capital; market and credit risks; fiscal federalism; energy; financial integration and inequality; and intellectual and human capital.

Toan Pham-Khanh Tran

Ngoc Phu Tran is a PhD student at Ho Chi Minh City Open University, Vietnam. His research interests include issues on intellectual capital, corporate governance and corporate social responsibility. He has published in various international journals, including Journal of Intellectual Capital, Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, Journal of Asia Business Studies and Competitiveness Review.

Toan Pham-Khanh Tran is a PhD student at Ho Chi Minh City Open University, Vietnam. His research interests are informal economy, institutional quality and public finance. He has published in PLoS ONE and International Journal of Emerging Markets.

Ngoc Phu Tran

Ngoc Phu Tran is a PhD student at Ho Chi Minh City Open University, Vietnam. His research interests include issues on intellectual capital, corporate governance and corporate social responsibility. He has published in various international journals, including Journal of Intellectual Capital, Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, Journal of Asia Business Studies and Competitiveness Review.

Toan Pham-Khanh Tran is a PhD student at Ho Chi Minh City Open University, Vietnam. His research interests are informal economy, institutional quality and public finance. He has published in PLoS ONE and International Journal of Emerging Markets.

References

- Achim, M. V., Borlea, S. N., Găban, L. V., & Mihăilă, A. A. (2019). The shadow economy and culture: Evidence in European countries. Eastern European Economics, 57(5), 352–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/00128775.2019.1614461

- Ajide, F. M. (2021). Shadow economy in Africa: How relevant is financial inclusion? Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, 29(3), 297–316. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRC-10-2020-0095

- Amin, S., & Ahmad, N. (2021). Diversity and informal economy: An international perspective. The Review of Black Political Economy, 48(2), 206–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034644620967003

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297968

- Awad, I. M., & Alazzeh, W. (2020). Using currency demand to estimate the Palestine underground economy: An econometric analysis. Palgrave Communications, 6(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0433-4

- Baklouti, N., & Boujelbene, Y. (2019). The economic growth–inflation–shadow economy trilogy: Developed versus developing countries. International Economic Journal, 33(4), 679–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/10168737.2019.1641540

- Barro, R. J. (1990). Government spending in a simple model of endogenous growth. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5, Part 2), S103–S125. https://doi.org/10.1086/261726

- Berdiev, A. N., & Saunoris, J. W. (2018). Does globalization affect the shadow economy? The World Economy, 41(1), 222–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12549

- Bernheim, B. D. (1989). A neoclassical perspective on budget deficits. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 3(2), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.3.2.55

- Blanton, R. G., Early, B., & Peksen, D. (2018). Out of the shadows or into the dark? Economic openness, IMF programs, and the growth of shadow economies. The Review of International Organizations, 13(2), 309–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-018-9298-3

- Boeke, J. H. (1942). Economics and economic policy of dual societies as exemplified by Indonesia. TjeenkWillnik, Harlem.

- Breitung, J. (2001). The local power of some unit root tests for panel data. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Buehn, A., & Schneider, F. (2012). Shadow economies around the world: Novel insights, accepted knowledge and new estimates. International Tax and Public Finance, 19(1), 139–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-011-9187-7

- Burger, P., & Calitz, E. (2021). Covid‐19, economic growth and South African fiscal policy. South African Journal of Economics, 89(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/saje.12270

- Busse, M., & Hefeker, C. (2007). Political risk, institutions and foreign direct investment. European Journal of Political Economy, 23(2), 397–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2006.02.003

- Canh, P. N., Schinckus, C., & Dinh Thanh, S. (2021). What are the drivers of the shadow economy? Further evidence of economic integration and institutional quality. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 30(1), 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2020.1799428

- Cebula, R. J. (1995). The impact of federal government budget deficits on economic growth in the United States: An empirical investigation, 1955–1992. International Review of Economics & Finance, 4(3), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/1059-0560(95)90042-X

- Chan, S. G., Ramly, Z., & Karim, M. Z. A. (2017). Government spending efficiency on economic growth: Roles of value-added tax. Global Economic Review, 46(2), 162–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/1226508X.2017.1292857

- Chen, M. A., Vanek, J., & Carr, M. (2004). Mainstreaming Informal Employment and Gender in Poverty Reduction: A Handbook for Policymakers and Other Stakeholders. London: Commonwealth Secretariat. https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstream/handle/10625/27817/IDL-27817.pdf

- Christie, T. (2014). The effect of government spending on economic growth: Testing the non‐linear hypothesis. Bulletin of Economic Research, 66(2), 183–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8586.2012.00438.x

- Comunale, M. (2017). Dutch disease, real effective exchange rate misalignments and their effect on GDP growth in EU. Journal of International Money and Finance, 73(B), 350–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2017.02.012

- Cooray, A., Dzhumashev, R., & Schneider, F. (2017). How Does Corruption Affect Public Debt? An Empirical Analysis. World development, 90, 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.08.020

- De Soto, H. (1989). The other path: The invisible revolution in the third world. Harper and Row.

- Dell’Anno, R., Davidescu, A. A., & Balele, N. P. (2018). Estimating shadow economy in Tanzania: An analysis with the MIMIC approach. Journal of Economic Studies, 45(1), 100–113. https://doi.org/10.1108/JES-11-2016-0240

- Dell’Anno, R. (2021). Theories and definitions of the informal economy: A survey. Journal of Economic Surveys. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12487.

- Docquier, F., Müller, T., & Naval, J. (2017). Informality and long‐run growth. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 119(4), 1040–1085. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjoe.12185

- Dreher, A., & Schneider, F. (2010). Corruption and the shadow economy: An empirical analysis. Public Choice, 144(1), 215–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-009-9513-0

- Easterly, W., & Rebelo, S. (1993). Fiscal policy and economic growth: An empirical investigation. Journal of Monetary Economics, 32(3), 417–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(93)90025-B

- Elbahnasawy, N. G., Ellis, M. A., & Adom, A. D. (2016). Political instability and the informal economy. World Development, 85, 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.04.009

- Elgin, C., & Oztunali, O. (2012). Shadow economies around the world: Model-based estimates. Bogazici University Department of Economics Working Papers, 5, 1–48.

- Elgin, C., & Oztunali, O. (2014). Institutions, informal economy and economic development. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 50(4), 145–162. https://doi.org/10.2753/REE1540-496X500409

- Elgin, C., & Erturk, F. (2019). Informal economies around the world: Measures, determinants and consequences. Eurasian Economic Review, 9(2), 221–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40822-018-0105-5

- Elgin, C., Kose, M. A., Ohnsorge, F., & Yu, S. (2021). Understanding the informal economy: Concepts and trends. In F. Ohnsorge & S. Yu (Eds.), The long shadow of informality: Challenges and policies. World Bank.

- Esaku, S. (2021). Does corruption contribute to the rise of the shadow economy? Empirical evidence from Uganda. Cogent Economics & Finance, 9(1), 1932246. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2021.1932246

- Farzanegan, M. R., Hassan, M., & Badreldin, A. M. (2020). Economic liberalization in Egypt: A way to reduce the shadow economy? Journal of Policy Modeling, 42(2), 307–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2019.09.008

- Feige, E. L. (1979). How big is the irregular economy? Challenge, 22(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/05775132.1979.11470559

- Friedman, M. (1968). The role of monetary policy. Essential Readings in Economics, 58(1), 215–231. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1831652

- Friedman, E., Johnson, F., Kaufmann, D., & Zoido-Labton, P. (2000). Dodging the grabbing hand: The determinants of unofficial activity in 69 countries. Journal of Public Economics, 76 (3), 459–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(99)00093-6

- Friedman, E., Johnson, S., Kaufmann, D., & Zoido-Lobaton, P. (2000). Dodging the grabbing hand: The determinants of unofficial activity in 69 countries. Journal of Public Economics, 76(3), 459–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(99)00093-6

- Gemmell, N., Misch, F., & Moreno-Dodson, B. (2012). Public spending and long-run growth in practice: Concepts, tools, and evidence. In B. Moreno-Dodson (Ed.), Is fiscal policy the answer? A developing country perspective (pp. 69). The World Bank.

- Goel, R. K., & Saunoris, J. W. (2014). Global corruption and the shadow economy: Spatial aspects. Public Choice, 161(1–2), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-013-0135-1

- Goel, R. K., Saunoris, J. W., & Schneider, F. (2019). Drivers of the underground economy for over a century: A long term looks for the United States. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 71, 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2018.07.005

- Hansen, B. E. (2020). Econometrics. University of Wisconsin. available at https://www.ssc.wisc.edu/∼bhansen/econometrics/Econometrics.pdf

- Hart, K. (2008). Informal economy. In S. N. Durlauf & L. E. Blume (Eds.), The new Palgrave dictionary of economics (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hassan, M., & Friedrich, S. (2016). Size and development of the shadow economies of 157 worldwide countries: Updated and new measures from 1999 to 2013. Journal of Global Economics, 4(3), 1–14.

- Hayat, R., & Rashid, A. (2020). Exploring legal and political-institutional determinants of the informal economy of Pakistan. Cogent Economics & Finance, 8(1), 1782075. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2020.1782075

- Hoffman, R. C., Munemo, J., & Watson, S. (2016). International franchise expansion: The role of institutions and transaction costs. Journal of International Management, 22(2), 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2016.01.003

- Hoinaru, R., Buda, D., Borlea, S. N., Văidean, V. L., & Achim, M. V. (2020). The impact of corruption and shadow economy on the economic and sustainable development. Do they “sand the wheels” or “grease the wheels”? Sustainability, 12(2), 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020481

- Huynh, C. M., & Nguyen, T. L. (2020). Fiscal policy and shadow economy in Asian developing countries: Does corruption matter? Empirical Economics, 59(4), 1745–1761. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01700-w

- ILO. (2018). Women and men in the informal economy: A statistical picture.

- ILO (2018). Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Picture. ILO Publishing, Geneva.

- Johnson, S., Kaufmann, D., McMillan, J., & Woodruff, C. (2000). Why do firms hide? Bribes and unofficial activity after communism. Journal of Public Economics, 76(3), 495–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(99)00094-8

- Kao, C. (1999). Spurious regression and residual-based tests for cointegration in panel data. Journal of Econometrics, 90(1), 1–44. 625. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00023-2

- Kelmanson, M. B., Kirabaeva, K., Medina, L., Mircheva, M., & Weiss, J. (2019). Explaining the shadow economy in Europe: Size, causes and policy options. International Monetary Fund.

- Khan, M., Raza, S., & Vo, X.V. (2020). Government spending and economic growth relationship: can a better institutional quality fix the outcomes?. The Singapore Economic Review, 66(3), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217590820500216

- Khan, S., & Rehman, M. Z. (2022). Macroeconomic fundamentals, institutional quality and shadow economy in OIC and non-OIC countries. Journal of Economic Studies. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JES-04-2021-0203.

- Kim, S., & Roubini, N. (2008). Twin deficit or twin divergence? Fiscal policy, current account, and real exchange rate in the US. Journal of International Economics, 74(2), 362–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2007.05.012

- La Porta, R., & Shleifer, A. (2008). The unofficial economy and economic development. National Bureau of Economic Research. No. w14520

- La Porta, R., & Shleifer, A. (2014). Informality and development. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(3), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.28.3.109

- Lewis, W. A. (1954). Economic development with unlimited supplies of labour. Manchester School of Economic and Social Studies, 22(2), 139–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9957.1954.tb00021.x

- Loayza, N. V. (2016). Informality in the process of development and growth. The World Economy, 39(12), 1856–1916. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12480

- Loayza, N. V. (2018). Informality: Why is it so widespread and how can it be reduced? Research & Policy Brief, World Bank.

- Makin, A. J., & Layton, A. (2021). The global fiscal response to COVID-19: Risks and repercussions. Economic Analysis and Policy, 69, 340–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2020.12.016

- Mauleón, I., & Sardà, J. (2017). Unemployment and the shadow economy. Applied Economics, 49(37), 3729–3740. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2016.1267844

- Mazhar, U., & Méon, P. G. (2017). Taxing the unobservable: The impact of the shadow economy on inflation and taxation. World Development, 90, 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.08.019

- Medina, L., & Schneider, F. (2018). Shadow economies around the world: What did we learn over the last 20 years? IMF Working Paper WP/18/17. International Monetary Fund.

- Medina, L., & Schneider, F. (2019). Shedding light on the shadow economy: A global database and the interaction with the official one. CESifo Working Paper No. 7981.

- Nguyen, B., Canh, N.P. & Thanh, S.D. (2021). Institutions, Human Capital and Entrepreneurship Density. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 12, 1270–1293.

- OECD/ILO. (2019). Tackling vulnerability in the informal economy. OECD Publishing.

- Özgür, G., Elgin, C., & Elveren, A. Y. (2021). Is informality a barrier to sustainable development? Sustainable Development, 29(1), 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2130

- Pedroni, P. (1999). Critical values for cointegration tests in heterogeneous panels with multiple regressors. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 61(s1), 653–670. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0084.61.s1.14

- Pedroni, P. (2004). Panel cointegration; asymptotic and finite sample properties of pooled time series tests, with an application to the PPP hypothesis. Econometric Theory, 20(3), 597–625. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266466604203073

- Pesaran, M. H. (2007). A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross‐section dependence. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 22(2), 265–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.951

- Pesaran, M. H., Ullah, A., & Yamagata, T. (2008). A bias‐adjusted LM test of error cross‐section Independence. The Econometrics Journal, 11(1), 105–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1368-423X.2007.00227.x

- Psychoyios, D., Missiou, O., & Dergiades, T. (2021). Energy-based estimation of the shadow economy: The role of governance quality. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 80(C), 797–808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2019.07.001

- Roodman, D. (2009). How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. The Stata Journal, 9(1), 86–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0900900106

- Ruzek, W. (2015). The informal economy as a catalyst for sustainability. Sustainability, 7(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7010023

- Sargent, T. J., & Wallace, N. (1981). Some unpleasant monetarist arithmetic. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, 5(3), 1–17.

- Saunoris, J. W. (2018). Is the shadow economy a bane or boon for economic growth? Review of Development Economics, 22(1), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12332

- Schneider, F., & Enste, D. H. (2000). Shadow economies: Size, causes, and consequences. Journal of Economic Literature, 38(1), 77–114. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.38.1.77

- Schneider, F. (2010). The influence of public institutions on the shadow economy: An empirical investigation for OECD countries. Review of Law & Economics, 6(3), 441–468. https://doi.org/10.2202/1555-5879.1542

- Schneider, F., Buehn, A., & Montenegro, C. E. (2010). Shadow economies all over the world. International Economic Journal, 24(4), 443–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/10168737.2010.525974

- Schneider, F., & Buehn, A. (2018). Shadow economy: Estimation methods, problems, results and open questions. Open Economics, 1(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1515/openec-2017-0001

- Tanzi, V. (1999). Uses and abuses of estimates of the underground economy. The Economic Journal, 109(456), 338–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00437

- Ullah, S., Akhtar, P., & Zaefarian, G. (2018). Dealing with endogeneity bias: The generalized methods of moments (GMM) for panel data. Industrial Marketing Management, 71, 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.11.010

- Westerlund, J. (2005). New simple tests for panel cointegration. Econometric Reviews, 24(3), 297–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/07474930500243019

- Williams, C. C., & Schneider, F. (2016). Measuring the global shadow economy: The prevalence of informal work and labour. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Williams, C. C. (2019). The informal economy. Columbia University Press.

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross-section and panel data. MIT press.

- Wu, D. F., & Schneider, F. (2019). Nonlinearity between the shadow economy and level of development (No. 12385). IZA Discussion Papers.

- Xu, T., Lv, Z., & Xie, L. (2018). Does country risk promote the informal economy? A cross-national panel data estimation. Global Economic Review, 47(3), 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/1226508X.2018.1450641

- Zhao, X., Ramzan, M., Sengupta, T., Sharma, G. D., Shahzad, U., & Cui, L. (2022). Impacts of bilateral trade on energy affordability and accessibility across Europe: Does economic globalization reduce energy poverty? Energy and Buildings, 262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2022.112023