Abstract

This study explores to answer the question: does the introduction of a moveable collateral registry lead to significant increase in access to credit to micro, small and medium-sized enterprises? We examine this question through a unique dataset collected from the moveable collateral registry and commercial banks in Malawi. The findings indicate that the introduction of the registry in Malawi has led to marginal increase in MSME’s access to bank credit. Real property, however, remains the preferred collateral and ability to repay the loan is the most important consideration amongst banks in assessing whether to lend to micro, small and medium-sized enterprises. We recommend the registry to integrate into its programs financial literacy training for MSMEs, and credit guarantee schemes to mitigate the perceived high risk associated with small enterprises. This will equip the MSMEs to keep proper accounts and enhance their access to the registry and bank credit.

1. Introduction

Access to finance has long been recognised as a key impediment facing the micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) sector in Malawi. According to the 2012 FinScope Survey of Malawi, up to 59% of MSME are financially excluded, with only 22% of MSMEs having access to, or using financial products such as, savings offered by a commercial bank. It further indicates limited access to credit amongst MSMEs with only 12% of MSMEs accessing credit, mainly from microfinance institutions and co-operatives (FinMark Trust, Citation2013). The survey noted that the difficulty of MSMEs in accessing credit was in part due to their lack of ownership of real assets, such as land or buildings which institutional lenders generally prefer as collateral (FinMark Trust, Citation2013). This situation particularly affects businesses owned by women who, in many developing countries, do not have clear property rights (United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Citation2013).

As part of measures to address the above statistics on MSMEs’ access to finance, the Malawian parliament passed the Personal Property Security Act in 2013 pursuant to which, the Personal Property Security Registry was introduced. The Registry is an online public database that allows financial institutions to register security interests in moveable assets, such as machinery, crops and livestock. As to whether this collateral registry has facilitated the extension of credit to those who were previously segmented outside the credit market by commercial banks is yet to be verified empirically. Theoretically, it is argued that collateral performs a screening and signalling function to reduce adverse selection caused by ex-ante agency problems as a result of asymmetric information characteristic in credit markets (Besanko & Thakor, Citation1987; Bester, Citation1985; J. E. Stiglitz & Weiss, Citation1981; Ioannidou et al., Citation2022). Another theory explains collateral as an enforcement device by securing against both exogenous and endogenous risks that lead to default (Nagarajan & Meyer, Citation1995).

The empirical evidence suggests that collateral laws such as secured transactions regulations are important drivers of access to credit. For example, Haselmann et al. (Citation2010) show that in Central and Eastern Europe credit supplied by banks increased subsequent to changes to collateral laws. Similarly, Chaves et al. (Citation2004) argue that collateral laws decrease the cost of credit through significantly lower interest rates and longer repayment periods, but weak collateral laws decrease access to bank credit (Calomiris et al., Citation2017). Whilst these statistics support the theory that secured transactions laws and registries increase availability of credit, they do not necessarily establish that such credit is allocated to MSMEs that were previously unable to secure credit. Collateral registries, which have been introduced in Ghana, China, Nigeria and Romania have witnessed increased registrations and access to external credit (Allafrica.com, Citation2019; World Bank, Citation2010c, Citation2012a, Citation2012b). These studies are, however, limited because some of the statistics reported are not specific to registration of moveable property secured loans granted to MSMEs. Also, Love et al. (Citation2013) study though inspiring is not restricted to MSMEs but include all types of firms. In addition, it does not consider whether financial institutions are in fact accepting diverse types of collateral, particularly those types of collateral that MSMEs in developing countries are likely to own.

The current study deals with these limitations by using a unique dataset to focus on MSMEs, which have historically been excluded from the credit market by large commercial banks. Our findings show that although the moveable collateral registry has witnessed increased registration of MSMEs, the influence on MSMEs’ access to bank credit has been very marginal. This study contributes to the literature in a number of significant ways. Unlike previous studies, this study isolates MSMEs, which were previously excluded from bank lending and then evaluates if the moveable collateral registry has facilitated credit extension to them. It also suggests policy changes that the collateral registry can adopt to improve MSMEs’ access to bank credit.

2. Overview of the banking sector and the moveable collateral landscape in Malawi

The banking sector in Malawi is small with low but increasing levels of financial intermediation (Chirwa, Citation2001). According to the United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF; Citation2015), banks dominate the financial services market in Malawi, providing 92% of total credit. The banking sector in Malawi is segregated into the formal, semi-formal and informal sector (Chirwa, Citation1999). The formal banking sector can be further categorised by types of financial services offered into the following markets—commercial banks, corporate banks, leasing finance, savings banks and building societies (Chirwa, Citation1999). Ownership structures in the Malawian banking industry are highly concentrated, with the majority of the banks controlled by a few international and domestic agricultural and industrial conglomerates (Chirwa, Citation1999). The industry has a total of 9 banks of which two are dominant with a controlling power of 56.2% and 46.1% of the industry total loans and deposits, respectively. As at December 2019, the banking system had 100 branches, 120 agencies, kiosks and vans and 496 automatic teller machines (ATMs).

The Malawian banking sector has historically concentrated its lending to corporate and well-established clients. In particular, the lending portfolio of the commercial banks is concentrated in well-established firms found in the wholesale and retail, agriculture and manufacturing sectors of the economy. Retail credit portfolio in which MSMEs are classified constitutes a small portion of the total loan portfolio.

The World Bank (Citation2010a) reported that whilst most financial institutions in Malawi recognized the potential of moveable property in securing credit and reported some use of moveable collateral albeit modest, some expressed scepticism regarding their ability to rely on this type of property. Dubovec and Kambili (Citation2015) report that this scepticism was due to several factors, including:

Weak and disjointed legal framework for moveable secured credit.

Very poor system for publicizing security interest in moveable assets and obtaining the information on existing creditor security interests.

Slow and unreliable administration and enforcement of moveable property rights by the courts; and

The perception that moveable asset-based lending is riskier because borrowers are less likely to repay loan secured by moveable assets than those secured by landed property.

The World Bank noted that the law relating to (moveable asset) secured transactions was obsolete and scattered across multiple pieces of legislation. The different pieces of legislation were not based on criteria used by modern law relating to secured transactions but rather on the type of property, type of borrower and/or type of transaction. Furthermore, the different pieces of legislation had different priority regimes and had their own underlying policy considerations. As a result, the rules under the various pieces of legislation were often inconsistent and contradicted each other. Malawi had a number of registries recording property rights against moveable assets. These registries operated under a number of specialized legislations as described. However, these registries operated under obsolete IT systems or were paper-based, therefore rendering it difficult for creditors to obtain information. Furthermore, the registries did not communicate with each other, making it difficult to carry out a reliable search and consequently making it difficult for creditors to rely on moveable property as collateral.

In light of the above, the World Bank recommended a modern, conceptually integrated secured transaction legal regime. It proposed the concept of single right, “security interest” which arises in any transaction which is, in essence, a financial transaction secured with moveable assets. The law would provide for a set of predictable priority ranking rules under a single piece of legislation. The World Bank recommended a centralized, modern, digitized registry under the reformed law for publication of claims against moveable assets. It was recommended that access should be available for investors, including those located outside of Malawi. This led to the establishment of new moveable collateral registry in 2013.

3. The literature review

3.1. The theoretical discussion

It is generally agreed that collateral is a critical feature of debt contracts and the ability and ease with which creditors can enforce their contracts with debtors is central to the market for credit (Berger et al., Citation2011; Calomiris et al., Citation2017). According to Fleisig et al. (Citation2006), between 70% and 80% of firms applying for a loan are required to pledge some form of collateral. Collateral is defined as an asset, moveable or immoveable, that upon liquidation, is adequate to cover all or the majority of a lender’s exposure, including principal, accrued interest and recovery costs (Larr, Citation1994). In addition, collateral is said to be characterized by appropriability (ease with which assets can be liquidated), absence of collateral-specific risks (risks, such as theft, fire, disease as well as inflation and political risks) and accrual of returns to the borrower during the loan contract period (either direct economic returns from the asset itself, or indirect returns from investments with loans obtained using the asset; Binswanger et al., Citation1986).

There are two leading schools of thought on the function of collateral. The first school of thought argues that collateral performs a screening and signalling function (J. E. Stiglitz & Weiss, Citation1981; Ioannidou et al., Citation2022). This school of thought motivates that collateral is a screening device to reduce adverse selection caused by ex-ante agency problems as a result of asymmetric information characteristic in credit markets (Besanko & Thakor, Citation1987; Bester, Citation1985). Asymmetric information is particularly problematic in the credit markets of developing countries. Fleisig et al. (Citation2006) note that in low- and middle-income countries, credit reporting systems, if they do exist, often contain very limited information. They further note that typical borrowers in low- and middle-income countries often lack audited financial statements. In developing countries, this often results in lenders choosing to do business with borrowers with whom they have longstanding relationships.

The first school further explains collateral as arising from ex-ante information asymmetry between borrowers and lenders that can otherwise lead to equilibrium characterised by credit rationing (J. E. Stiglitz & Weiss, Citation1981). Credit rationing refers to a situation in which lenders are unwilling to extend additional funds to borrowers even if the borrowers are willing to pay higher interest rates (J. Stiglitz & Weiss, Citation1992). It is an example of market failure in that the price mechanism is unable to bring out equilibrium in the credit market. In these models, lenders offer a variety of contracts with various combinations of collateral requirements, interest rates and other terms and conditions (Berger et al., Citation2011; J. E. Stiglitz & Weiss, Citation1981; Nagarajan & Meyer, Citation1995). These models predict that riskier borrowers are less likely to pledge collateral, whilst borrowers with less risk of default are likely to accept increases in collateral requirements in exchange for reductions in loan interest rates. In this sense, collateral is said to be a signalling device, as borrowers signal their risk type by their preference between collateral and interest rates and other terms and conditions. Lenders can use this information as a low-cost screening device to assist in sorting borrowers according to their risk type. Furthermore, this school of thought motivates collateral as a device to attenuate various ex-post frictions, including moral hazard (Berger et al., Citation2011; Boot & Thakor, Citation1994; Boot et al., Citation1991), costly public verification (Gale & Hellwig, Citation1985) and imperfect and costly contract enforcement (Albuquerque & Hopenhayn, Citation2004; Townsend, Citation1979).

The second school of thought explains collateral as an enforcement device. This school of thought argues that collateral secures against both exogenous (poor or unsatisfactory business performance due to events or circumstances outside the borrower’s control) and endogenous risks (risks that a borrower will engage in moral hazardous activities) that lead to default (Nagarajan & Meyer, Citation1995). For collateral to serve as an effective enforcement device, it must be able to reduce the lender’s loss or at least make it costly for the borrower to default, or both (Barro, Citation1976). This requires that pledged assets have well-established and transferable property rights, a conducive legal and regulatory environment that facilitates loan enforcement and assumes the marketability of assets offered as collateral (Nagarajan & Meyer, Citation1995). It is clear that law is critical if collateral is to perform its intended function; well-defined creditor rights and ease of enforcement influence lending activity and access to finance (Haselmann et al., Citation2010).

Given the theoretical importance of collateral laws, much attention has been paid recently to the importance of developing the law of secured transactions (Xu, Citation2018; Fleisig et al., Citation2006). The law of secured transactions is considered critical in increasing the supply of, and promoting access to, credit. Technically, a transaction can be regarded as secured where property is pledged by a borrower to a lender under the terms of a loan agreement to secure future payment, with the lender being entitled to dispose of the property if the borrower defaults on payment (Otabor-Olubor, Citation2017). Theoretically, most forms and types of property are amenable as the basis of granting of security (Otabor-Olubor, Citation2017; United Nations Commission on International Trade Law, Citation2010). However, the literature in relation to access to finance generally uses the term secured transactions in relation to moveable assets. The concentration on moveable property has been motivated by empirical research that indicates the dominance and importance of moveable assets to firms. According to the World Bank (Citation2018), up to 80% of capital stock of private firms in developing countries comprises moveable assets. This percentage is even higher for MSMEs (Ahmad, Citation2018). The situation is not any different in developed countries. According to statistics from Fleisig et al. (Citation2006), moveable property consists of up to 60% of an enterprise’s capital stock. However, whilst in developed countries lenders consider a wide variety of moveable assets including inventories, account receivables and intellectual property as sources of collateral; the situation is a lot different in developing countries (Fleisig et al., Citation2006). In low- and middle-income countries, there is a significant mismatch between the assets that firms have and the assets that lenders accept as collateral and this mismatch is the root of lack of access to credit (Fleisig et al., Citation2006). The theoretical assumption is that legal reforms allowing for the recognition of varied types of moveable collateral and provision of public notice of interests in moveable assets and establishment of priority in registered interests, would improve access to credit.

Collateral registries for moveable assets perform two key functions, the first of which is to notify parties of the existence of a security interest in moveable property. A reliable registry eliminates the risk that a borrower pledges the same property as collateral to secure other loans without the knowledge of the lender. Secondly, it establishes a ranking as between existing registered security interests and vis-à-vis other unsecured creditors (Campa et al., Citation2012). Therefore, without some form of functioning record system for moveable security interests, even the most basic of secured transaction laws can be rendered ineffective or useless (Love et al., Citation2016). There is abundant theoretical literature on the advantages of moveable collateral laws and registries. Moveable collateral registries assist in addressing the agency problem arising from information asymmetry. Registries provide a screening device, thereby reducing adverse selection and moral hazard (Besanko & Thakor, Citation1987; Bester, Citation1985). Registries also eliminate or reduce government verification costs as well as imperfect enforcement. Registries allow lenders to enforce their contract with borrowers in a smooth and cost-effective manner (Osuji, Citation2017). It is believed that providing legal structures through which moveable assets can be effectively used as security will significantly increase access to credit by those firms that need it the most (World Bank, Citation2010b).

3.2. The empirical literature

Some empirical studies exist on the impact of moveable collateral laws and registries. Following a study of lending behaviour of banks in 12 transition economies of Central and Eastern Europe after changes in creditor rights protection (including a change in collateral laws), Haselmann et al. (Citation2010) found that credit supplied by banks increased subsequent to legal change. They also found that collateral laws mattered more for credit market development than bankruptcy law. In a study on the relationship between the law of secured transactions and economic development, Safavian et al. (Citation2006) found that in countries where security interests were perfected and where there was a mechanism for priority of security interests in cases of loan default, credit to private sector as a percentage of gross domestic product averaged 60%, compared to only 30% to 32% on average for countries without such mechanisms of creditor protection. Similarly, Calomiris et al. (Citation2017) found that loan to values of loans collateralized with moveable assets were lower in countries with weak collateral laws relative to immoveable assets. They also found that in the countries with weak collateral laws, lending was biased towards the use of immoveable property. Studies have indicated that a secured transaction system decreases the cost of credit through significantly lower interest rates and longer repayment periods (Chaves et al., Citation2004). Whilst these statistics support the theory that secured transaction law and registries increase availability of credit, they do not necessarily establish that such credit is allocated to MSMEs that were previously unable to secure credit.

Some specific studies exist on the effect of the introduction of collateral registries. Following Ghana’s introduction of collateral registry laws in 2008, it was reported that 20,000 transactions were recorded in 1 year. By 2012, it was reported that the registry recorded 40,544 registrations, more than five times the initial target. It was also reported that as of June 2012, more than 5,000 small- and medium-sized enterprises and 22,000 microbusinesses had obtained credit granted by banks and non-bank financial institutions (World Bank, Citation2012a). In China, where the law became operational in 2007, it was reported that there was a 21% increase per year in commercial loans secured by moveable assets from 2008 to 2010. It was reported that by 2012, the Credit Reference Centre recorded cumulating accounts receivables finance of approximately USD 3.5 trillion from 2007, representing 385,000 registrations (World Bank, Citation2012b). In Romania, collateral registry laws were introduced in 1999 and registrations increased from 65,227 in 2000 to 536,067 in 2006 (World Bank, Citation2010c). In 2002, the Slovakian government introduced a reform package that included a bankruptcy regime, corporate governance rules and a framework for secured transactions. A registry, the “Chamber of Notaries”, was introduced and handled moveable assets. According to the Slovakian government, annual registrations increased from 7,508 in 2003 to 31,968 in 2007, a yearly increase of over 50% (World Bank, Citation2010c). In Nigeria, the national collateral registry was introduced in 2017 and it was reported that a cumulative of 154,827 MSMEs used moveable assets to obtain loans from financial institutions (Allafrica.com, Citation2019).

There are various limitations to the above empirical studies in assessing the impact of moveable collateral laws and registries on access to credit of previously marginalized borrowers. Firstly, some of the statistics reported are not specific to registration of moveable property secured loans granted to MSMEs. It would not be clear therefore whether the statistics comprise registrations by businesses who hitherto were already able to access credit from financial institutions. Secondly, in the absence of statistics on moveable collateral secured loans granted in the years prior to the introduction of the registry, it would be unclear how much impact the registry has had on access to credit. Thirdly, whilst year-on-year increases in registration are positive statistics, there could be other reasons for this besides the increase in access to credit. An increase in registrations could be a result of increase in credit appetite and hence increase in lending generally by financial institutions. Increase in registrations could equally be the result of an increase in the number of financial institutions, especially microfinance institutions. Given that microfinance institutions generally already lend to MSMEs and typically readily accept moveable property as collateral, an increase in registrations because of an increase in the number of microfinance institutions speaks little of the impact or effect of the registry on access to bank credit.

The most comprehensive empirical study to date was undertaken by Love et al. (Citation2013). Using firm-level surveys for up to 73 countries, the survey explored the impact of introducing moveable collateral registries on firms’ access to bank finance. The survey compared firms’ access to bank credit in seven countries that introduced moveable collateral registries against three control groups. The three control groups comprised firms in all countries that did not introduce a moveable collateral registry, firms in a sample of countries matched by location and income per capita to the countries that introduced moveable collateral registries and thirdly, firms in countries that pursued other types of reforms but did not introduce registries. The study found that, overall, the introduction of moveable collateral registries increased the access of firms to bank finance. However, again, the limitation of this study is that it includes all types of firms and is not restricted to MSMEs. In addition, this study does not consider whether financial institutions are in fact accepting diverse types of collateral, particularly those types of collateral that MSMEs in developing countries are likely to own.

The current study investigates the effect of the introduction of a collateral registry on access to bank credit by MSMEs only. Focusing on only MSMEs is very important in determining whether the introduction of the registry has been beneficial to those who were previously unbanked. As discussed before, this is important because banks may continue to assess loan applications based on risk profile of firms so that despite a registry, MSMEs may still be unable to access loans. The registry may in this case only assist those firms that have a lower risk profile.

4. The methodology

As stated previously, the main objective of the study was to explore whether the introduction of a moveable collateral registry led to greater access to bank credit amongst MSMEs.

4.1. Sampling technique and sample size

The sample size is limited to commercial banks, which lend to MSMEs. Of the nine banks in Malawi, only five have MSMEs’ loan portfolios. These comprise National Bank of Malawi, Standard Bank of Malawi, NBS Bank Malawi, First Capital Bank of Malawi and FDH Bank. The remaining banks in Malawi: Nedbank, Ecobank, CDH Investment Bank are largely corporate banks and have a specific target market that excludes MSMEs and therefore were excluded from the sample size. The New Finance Bank is a new bank that would not have the data required for this study. In addition, data from microfinance institutions were not used in this study as it would not be appropriate as the purpose of the study was to evaluate whether lending to MSMEs by commercial banks that previously avoided lending to this group has increased following the introduction of the registry.

4.2. Data collection and analysis

Both primary and secondary data were used for the study. The secondary data was sourced from the database of the Personal Property Security Registry of Malawi. The data covers the first 5 years since the introduction of the registry. It covers monthly data on moveable asset-based lending by commercial banks, which had previously segmented out MSMEs from their credit portfolios. The data is grouped by types of collateral (e.g., vehicles, machinery, crops and cattle). Information on total lending of financial institutions was obtained from the Reserve Bank of Malawi. This data was used to assist in analysis of the registry statistics.

The primary data was collected from the credit departments of the five commercial banks. Data was collected on MSME lending in the 3-years prior to the introduction of the registry and for the 3 years after the introduction of the registry. The survey questionnaire requested the commercial banks to rank their preferred sources of collateral prior to and after the introduction of the registry.

The survey questionnaire has questions, such as:

Has the introduction of the registry led to more moveable asset-based lending in your institution in general and in particular, to MSMEs? Why or why not?

Has the introduction of the registry impacted the credit evaluation process in your institution, and if so, how?

Do you view moveable property more favourably as collateral compared to before the introduction of the registry?

What, in your opinion, is the most important factor affecting your decision whether to lend to MSMEs?

A mixed-method technique comprising quantitative and qualitative methods was used for the empirical evaluations. The quantitative method was in the form of descriptive statistics and t-test. The t-test was used to determine if there is a statistically significant difference between large firm and MSMEs access to bank credit following the introduction of the collateral registry. It was also used to determine the statistical difference between commercial banks and microfinance instructions (MFIs) lending to MSMEs following the introduction of the collateral registry. From the primary data, the percentage range of MSME loans prior to the introduction of the registry was compared with the percentage range of MSME loans after the introduction of the registry for each of the five commercial banks. This provided a clear indication of the nature of the effect, if any, of the collateral registry. The ranking of preferred collateral source prior to and after introduction of the Registry as well as the reasons for the preferences was also analysed. The analysis facilitated an evaluation of the effect of the registry on MSMEs’ access to bank credit.

5. The results and discussion

5.1. Registry and central bank statistics

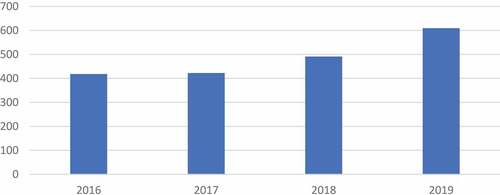

From the illustration in Figure , the number of registrations by banks at the registry in the years 2017 to 2019 remained relatively steady. There was a 48% reduction in number of registrations in 2017. According to the registry, the high number of registrations by banks in 2016 was largely the result of banks registering the moveable collateral that they were already holding and which were hitherto maintained in other registries or which were unregistrable.

Figure 1. Number of registrations per year per category of lenders, 2016–2020.

Before the introduction of the collateral registry, MSMEs were mostly sourcing for loans from microfinance institutions (MFIs). It was expected that the introduction of the collateral registry would enhance MSMEs access to loans from commercial banks. Indeed, Figure shows that there is a growing supply of commercial banks’ loans to MSMEs after the collateral registry introduction. Although the increment in commercial banks’ lending to MSMEs is lower than that of MFIs, we show through a t-test that the difference is not statistically significant. Table presents the results of the t-test between lending from commercial banks and MFIs. The insignificant difference suggests that commercial banks have opened-up their loan portfolios to MSMEs because of the setting up of the moveable asset-based lending registry. Indeed, Figure points to this point. It illustrates that lending from commercial banks has witnessed increased market activity since the introduction of the collateral registry.

Table 1. Number of moveable asset-based lending registered by commercial banks and MFIs

We also run a comparative test between large firms and MSMEs access to moveable asset-backed loans. The intention is to determine whether the collateral registry and the subsequent increase in commercial banks’ lending are dominated by large firms. Our findings indicate the opposite. It shows that MSMEs have as much access as large firms. The number of large firms on the registry does not statistically differ from MSMEs, an indication that the registry is addressing the prior imbalance in MSMEs access to bank credit. This confirms the findings of Love et al. (Citation2016) and Chapoto and Aboagye (Citation2017). It is, however, important to note that certain lending to some large firms is not listed on the registry because such lending may be unsecured. Table shows the comparative access to moveable asset-backed loans by large firms and MSMEs following the introduction of the registry.

Table 2. Access to moveable asset-backed loans: Comparison between large firms and MSMEs

5.2. Analysis of the survey results from commercial banks

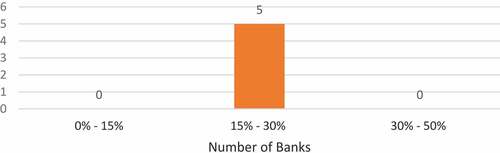

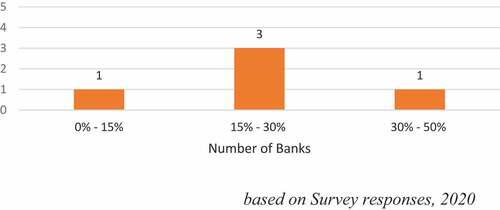

The graphs presented in Figures above summarize the key statistics regarding the average MSME lending by the commercial banks that participated in the survey.

Figure 4. Banks’ lending to MSME after the introduction of the registry.

According to the questionnaire responses, the average percentage lending to MSMEs in the 3 years prior to the introduction of the registry among all the surveyed commercial banks was between 15% and 30%. The average lending to MSMEs in the 3 years following the introduction of the registry ranged from 0% to 50%. This indicates an increase in the upper limit percentage from 30% to 50%. Although this increment is minimal, it is a good start (within the first 3 years) and a signal of the potential of the registry. The average increase in lending to MSMEs appears to correspond to the general increase in gross loans and advances as per Figure .

Regarding the type of moveable assets preferred by commercial banks, the results indicate that the most favoured categories of collateral prior to the introduction of the registry were cash, treasury instruments, vehicles, plant, machinery and debentures. Inventory, receivables and commodities were accepted by some banks although not preferred. From the survey results, these preferences have remained unchanged following the introduction of the registry. The survey results clearly correspond with the statistics from the registry with the number of cash collateral registrations leading, followed by vehicles, plant and machinery and debentures.

All respondent banks indicated that cash was the easiest collateral to enforce prior to the introduction of the registry and this situation has remained unchanged. According to the survey, crops and plant, machinery and equipment were the most difficult to enforce. Again, this situation has remained unchanged.

Sixty percent of the respondents indicated that the introduction of the registry has not caused significant changes in their credit evaluation process. However, a sizeable minority of 40% have initiated changes in their credit evaluation process, but only to the extent that they were able to confirm if proposed collateral was already encumbered. Aside from this, all the respondent banks offered similar reasons for the minimal increase in MSME loans despite the introduction of the registry. The key reason for the lack of substantial increase in MSME lending is the fact that the most important factor in assessing whether to lend to customers remains their ability to repay the loan (which, according to the banks, should be evidenced by financial records, cash flow projections and business activity) with collateral only being a secondary consideration. Some perceived lending to MSMEs to be very risky and costly. The risky profiles associated with MSMEs can be minimized if microinsurance is integrated into the loan portfolios (Akotey & Adjasi, Citation2016). In terms of the factors that commercial banks take into consideration when deciding whether to accept moveable assets as collateral, the banks were unanimous in that the three most important factors are ease of enforcement, ease of conversion into cash and rate of depreciation. Other relevant secondary factors included location of assets, ease of monitoring the assets and loan-to-value ratio.

6. Conclusion and policy recommendations

The study has assessed the effect of a moveable collateral registry on MSME access to bank credit. The study employed quantitative data obtained from the registry on registrations since it became operational and qualitative data from commercial banks on MSME lending prior to and after the introduction of the registry. The findings show that the registry has led to a marginal increase in MSME lending. Furthermore, the evaluation process for lending to MSMEs by commercial banks remains largely unchanged and real property remains the preferred collateral source amongst commercial banks.

Given that ability to repay remains the driving consideration for commercial banks for their decision to lend, and since most MSMEs in Malawi do not keep sufficient financial records to enable banks to properly assess their financial strength, this study recommends the introduction of financial literacy training to equip MSMEs with the necessary bookkeeping skills required to prepare quality financial records. Augmenting the collateral with skill training and financial literacy will equip MSMEs to access substantial loan amount for productive activities. Commercial banks continue to view MSMEs as high risk, thus bounding appropriate microinsurance with the loans will benefit both the bank and the MSMEs in terms of welfare gains and loss reduction and timely loan repayment. Again, government credit guarantee scheme can be used to mitigate some of the perceived high risk associated with MSMEs.

Author on contributors

Susan works with Eastern and Southern African Trade and Development Bank. She took part in this research during her MPhil studies at University of Stellenbosch Business School. The correspondence author can be reached at [email protected]; [email protected]

Disclosure statement

The authors do not have any competing interest as far as this research is concerned.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmad, D. (2018). Can introduction of collateral registries for movable assets spur firms’ access to credit in Nigeria? International Journal of Research and Scientific Innovation, 5(12), 102–13.

- Akotey, J. O., & Adjasi, C. K. D. (2016). Does microcredit increase household welfare in the absence of microinsurance? World Development, 77, 380–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.09.005

- Albuquerque, R., & Hopenhayn, H. A. (2004). Optimal lending contracts and firm dynamics. Review of Economic Studies, 71(2), 285–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/0034-6527.00285

- Allafrica.com. (2019). Nigeria: Unlocking access to finance. https://allafrica.com/stories/201902110635.html

- Armendáriz, B., & Morduch, J. (2010). The economics of microfinance. MIT Press.

- Barro, R. J. (1976). The loan market, collateral, and rates of Interest. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 8(4), 439–456. https://doi.org/10.2307/1991690

- Berger, A., Frame, W. S., & Ioannidou, V. (2011). Tests of ex ante versus ex post theories of collateral using private and public information. Journal of Financial Economics, 100(1), 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2010.10.014

- Besanko, D., & Thakor, A. V. (1987). Collateral and rationing: Sorting equilibria in monopolistic and competitive credit markets. International Economic Review, 28(3), 671–689. https://doi.org/10.2307/2526573

- Bester, H. (1985). Screening vs. rationing in credit markets with imperfect information. American Economic Review, 75(4), 850–855. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1821362

- Binswanger, H. P., Balaramaiah, V., Bashkar Rao, Bhende, M. J., & Kashirsagar, K. V. (1986). Credit markets in rural South India: Theoretical issues and empirical analysis. Hyderabad: ICRISAT, Working Paper. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/584921468033614109/credit-markets-in-rural-south-india-theoretical-issues-and-empirical-analysis

- Boot, A. W. A., & Thakor, A. V. (1994). Moral hazard and secured lending in an infinitely repeated credit market game. International Economic Review, 35(4), 899–920. https://doi.org/10.2307/2527003

- Boot, A. W. A., Thakor, A. V., & Udell, G. F. (1991). Secured lending and default risk: Equilibrium analysis, policy implications and empirical results. Economic Journal, 101(406), 458–472. https://doi.org/10.2307/2233552

- Calomiris, C. W., Larrain, M., Liberti, J., & Sturgess, J. (2017). How collateral laws shape lending and sectoral activity. Journal of Financial Economics, 123(1), 163–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2016.09.005

- Campa, A. A., Downes, S. C., & Hennig, B. T.(2012). Making security interests public: Registration mechanisms in 35 jurisdictions. World Bank Group. https://www.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/media/Special-Reports/Making-Security-Interests-Public.pdf

- Chapoto, T., & Aboagye, A. Q. Q. (2017). African innovations in harnessing farmer assets as collateral. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 8(1), 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJEMS-03-2017-144

- Chaves, R., Nuria, P., & Heywood, F. (2004). Secured transaction reform: Early results from Romania. CEAL Issues Brief, Center for Economic Analysis of Law. http://www.ceal.org/publications/CEALRomaniaSecTransNote.pdf

- Chirwa, E. W. (1999). Financial sector reforms in Malawi: Are the days of financial repression gone? Savings and Development, 23(3), 327–351. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25830698

- Chirwa, E. W. (2001). Market structure, liberalization, and performance in the Malawian banking industry. In AERC Research Paper (Vol. 108). Nairobi: African Economic Research Consortium. https://aercafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/RP108.pdf

- Dubovec, M., & Kambili, C. (2015). A guide to the personal property security act: The case of Malawi. Pretoria University Law Press (PULP).

- Fleisig, H., Safavian, M., & de la Peña, N. (2006). Reforming collateral laws to expand access to finance. World Bank Publications, August. https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/978-0-8213-6490-1

- Gale, D., & Hellwig, M. (1985). Incentive-compatible debt contracts: The one-period problem. Review of Economic Studies, 52(4), 647–663. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297737

- Haselmann, R. F. H., Pistor, K., & Vig, V. (2010). How law affects lending. The Review of Financial Studies, Society for Financial Studies, 23(2), 549–580. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhp073

- Ioannidou, V., Pavanini, N., & Peng, Y. (2022). Collateral and asymmetric information in lending markets. Journal of Financial Economics, 144(1) 93–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.12.010

- Larr, P. (1994). Two sides of collateral: Security and danger. The Journal of Commercial Lending, 8–17.

- Love, I., Pería, M. S. M., & Singh, S. (2013). Collateral registries for moveable assets: Does their introduction spur firms’ access to bank finance? Policy Research Working Paper, No. 6477. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/15839

- Love, I., Pería, M. S. M., & Singh, S. (2016). Collateral registries for movable assets: Does their introduction spur firms’ access to bank financing? Journal of Financial Services Research, 49(1), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-015-0213-2

- Nagarajan, G., & Meyer, R. L. (1995), Collateral for loans: When does it matter? Economics and Sociology Occasional Paper No. 2207, https://kb.osu.edu/bitstream/handle/1811/66599/CFAES_ESO_2207.pdf?sequence=1

- Osuji, E. (2017). Moveable assets registry in Nigeria: Promoting growth through effective legislation. Paper presented at the Conference of the African Bar Association held in Port Harcourt Nigeria, August 6, 2017. https://www.afribar.org/portHarcourt2017/papers/MovableAssetsRegistryinNigeriaPromotingEcon.pdf

- Otabor-Olubor, I. (2017). A critical appraisal of secured transactions over personal property in Nigeria: Legal problems and a proposal for reform. Nottingham Trent University. http://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/31955/

- Reserve Bank of Malawi (RBM). (2020). Financial Supervision Annual Reports, 2016–2019. https://www.rbm.mw/(S(23o3cjymwtshm3eogihvsi45))/Supervision/BankSupervision/?activeTab=BASUAnnualReports

- Safavian, M., Heywood, F. H., & Jevgenijs, S. J. (March 2006). Unlocking dead capital: How reforming collateral laws improves access to finance. Private Sector Development Viewpoint. (307), World Bank https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/7100

- Stiglitz, J. E., & Weiss, A. (1981). Credit rationing in markets with imperfect information. The American Economic Review, 71(3), 393–410. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1802787

- Stiglitz, J., & Weiss, A. (1992). Asymmetric information in credit markets and its implications for macro-economics. Oxford Economic Papers, 44(4), 694–724. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.oep.a042071

- Townsend, R. M. (1979). Optimal contracts and competitive markets with costly state verification. Journal of Economic Theory, 21(2), 265–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0531(79)90031-0

- Trust, F. (2013). FinScope Malawi MSME Survey 2012. https://info.undp.org/docs/pdc/Documents/MWI/Malawiper cent202012per cent20MSMEper cent20Mainper cent20Reportper cent20-per cent20Final.pdf

- United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF). (2015). Making access possible (MAP) program: Demand, supply, policy and regulation. Malawi country diagnostic report.

- United Nations Commission on International Trade Law. (2010). Legislative guide on secured transactions. https://uncitral.un.org/sites/uncitral.un.org/files/media-documents/uncitral/en/09-82670_ebook-guide_09-04-10english.pdf

- United States Agency for International Development (USAID). (2013). State of the evidence: Finance and moveable collateral. Enabling Agricultural Trade (EAT) Project. https://www.agrilinks.org/sites/default/files/resource/files/State_of_the_Evidence_Finance_Movable_Collateralz.pdf

- World Bank. (2010a).Getting credit–Secured transactions in Malawi. Investment Climate Advisory Services, https://stlrp.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/getting-credit-in-malawi-_-may-212010.pdf

- World Bank. (2010b). Secured transactions systems and collateral registries. Investment Climate Advisory Services, https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/d74da177-192e-49bc-a69a-716cfb95b0c7/SecuredTransactionsSystems.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=jkCVsiF

- World Bank. (2010c). Secured transactions & collateral registries: Global expansion, global results. http://www.oas.org/en/sla/dil/docs/gm_jamaica_feb_2015_presentations_Jennifer_Barsky_1.pdf

- World Bank. (2012a). It started in Ghana: Implementing Africa’s first collateral registry. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/17054/752410BRI0SMAR0teral0Registry0FINAL.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- World Bank. (2012b). Secured Credit Transaction Advisory Project in China. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/cad7af98-791b-4c7b-b8c3-b5edbcc81214/Secured+Transactions+Project+in+China+Notes.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=jr1VTZe

- World Bank. (2018). Improving access to finance for SMES: Opportunities through credit reporting, secured lending, and insolvency practices. https://www.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/media/Special-Reports/improving-access-to-finance-for-SMEs.pdf

- Xu, B. (2018). Permissible collateral and access to finance: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. BOFIT Discussion Paper No. 3/2018. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/212888/1/bofit-dp2018-003.pdf