Abstract

Crude oil is one of the sources by which budgets are financed in OPEC countries. However, the fall in oil prices in 2014 put their governments’ finances under significant pressure. Healthcare was one of the sectors experiencing fiscal strain. This study examined the effect of a fall in oil prices on healthcare financing in eight OPEC countries and whether such financing has shifted away from the dependence on oil. Quantitative healthcare expenditure data from the WHO covering the period from 2003 to 2019 were evaluated using a comparison of means Welch’s t-test. The result showed that government healthcare expenditure in Iran, Venezuela, and Kuwait increased in the period post-2014 compared to the expenditure after 2008 and 2002, suggesting that these countries succeeded in shielding such spending against the fall in oil prices. By contrast, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Nigeria, and Algeria did not, highlighting that they have not yet moved from dependence on oil. With the economic uncertainty caused by oil fluctuations, global political and economic developments, and the world transitioning to green energy, oil-dependent countries should free their governments’ healthcare expenditure from dependence on such sources of funding. Furthermore, they should not focus on temporary plans by shifting the burden to private spending at a time of falling oil prices, but to utilize different financing approaches.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study investigates the effect of the fall in oil prices on healthcare expenditure in OPEC countries, and whether these countries have shifted away from the dependence on oil. Quantitative data from the WHO for the period from 2003 to 2019 were used, and Welch’s t-test was applied. The proportion of government expenditure on healthcare to total expenditure on healthcare decreased in 2015–2019 due to oil prices shock as compared to 2003–2007 and 2009–2013 in the majority of the countries, to shift the burden of healthcare expenditure into the private spending and specifically to individuals. It was argued that a majority of OPEC countries have not yet moved from the dependence on oil, and oil-dependent countries are urged to increase their investment in healthcare and utilize different sources of healthcare financing.

1. Introduction

Many governments’ financing relies on oil in different ways, such as taxing fuel consumption or oil companies and income from the oil companies owned by the government. In 2018, a total of 24 countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) taxed fuel at $2 per gallon whereas 10, most from the EU, taxed up to $3 (OECD, Citation2019). Globally, the revenue from oil in 27 countries exceeded 3% of their GDP and by more than 20% in 10 of them (Global Economy, Citation2019). Such high dependence on oil along with the absence of a sustainable alternative may affect the finances of many governments during falling oil prices.

The global financial crisis of 2008 slowed the world’s economic activities, which reduced the demand for energy (Keegan et al., Citation2013; Lindström & Giordano, Citation2016) and decreased oil price by 75% to a low of $35 per barrel between July and December that year (OPEC, Citation2022a). Similarly, the price fell by 52% between July and December in 2014 to $51 per barrel due to low demand, particularly in China and Europe, and oversupply, notably from the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC; Mead & Stiger, Citation2015). Consequently, many governments’ finances were placed under significant strain. For example, OPEC countries experienced immediate budget deficits in 2008 and 2014, specifically Iraq, Venezuela, Angola, and Iran (Country Economy, Citation2020; World Bank, Citation2022). The effect was higher 1 year later; in 2009, the deficit was 13% of GDP in Iraq and 8% in Angola and Venezuela. In 2015, it was more than 15% in Algeria and Saudi Arabia (SA) and significantly higher in Libya, exceeding 70%, also influenced by political instability (Country Economy, Citation2020). One area that was severely affected was healthcare financing, which has long-term ramifications.

There is a large body of evidence in the literature that provides reliable grounds for healthcare financing in different regions and countries. However, there is a lack of evidence on the effect of falling oil prices on healthcare expenditure and if countries pursued alternative sources of healthcare financing to oil. Although some studies implied to the effect of falling oil prices on public spending, public policy, and the economic growth in oil-dependent countries (Ali, Citation2021; Charfeddine & Barkat, Citation2020; Martinez, Citation2022), the focus was on the 2008 financial crises and its indirect impact on healthcare outcomes.

Many studies investigated the impact of the 2008 financial crises on healthcare coverage and prevalence of specific health aspects in the EU and OECD countries, such as declining hours for homecare (Burke et al., Citation2014), unmet healthcare needs (Karanikolos et al., Citation2016; Pappa et al., Citation2013), and increasing incidences of mental health disorders (Barr et al., Citation2012), but with no insights on oil price shocks. Other studies directed analysis of public expenditure to some types of mortality (Budhdeo et al., Citation2015), pharmaceutical (García Ruiz et al., Citation2019), and health outcomes in EU and OECD countries (Edney et al., Citation2018), and others focused on the prevalence of specific diseases such as tuberculosis in Nigeria (Sede & Osifo, Citation2017), to fill gaps in important scientific topics. However, inputs on the effect of the fall in oil prices are lacking.

More recent literature broadened investigations on financing healthcare systems, and included the period of the 2008 financial crisis and the fall in oil prices in 2014, where different types of comparisons were conducted to cover diverse groups of countries, but with less direct insight into the effect of the fall in oil prices. For example, the response of the G7 countries to different economic indicators including healthcare was investigated with comparison to the response in Emerging Markets Seven (E7) before, during, and after the 2008 financial crisis (Jakovljevic et al., Citation2020), but given the valuable contribution to healthcare financing, the effect of oil prices was not highlighted. Another study analyzed healthcare expenditure of Mediterranean countries via different healthcare spending indicators (Grima et al., Citation2018). Other studies investigated the effect of the 2008 financial crisis on healthcare spending among EU countries that received financial bailout after the crisis (Loughnane et al., Citation2019). Others focused on the affordability of the private healthcare expenditure (Johnston et al., Citation2019; Keane et al., Citation2021). However, none added inputs regarding oil prices shocks. Moreover, Karanikolos et al. (Citation2016) conducted a systematic review that included 122 studies on the effect of the 2008 financial crisis on healthcare, but no contribution to the impact of the fall in oil prices was mentioned either (Karanikolos et al., Citation2016).

Further investigation of the literature revealed a wide contribution to healthcare financing bridging gaps in relation to the trends of historical and future healthcare spending, such as those conducted in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS; Jakovljevic et al., Citation2022), which challenge aging and population growth. Other research investigated previous and future healthcare spending in 184 countries for more insight in relation to growth in healthcare needs and sufficient spending (Dieleman et al., Citation2017b, Citation2017a; Reshetnikov et al., Citation2019). Some studies also focused on the historical development and healthcare financing in the Global South (M. B. Jakovljevic, Citation2015; Jakovljevic et al., Citation2021), G7, and BRICS (M. M. Jakovljevic, Citation2016) countries. Despite more insight on historical and future trends of healthcare financing in these countries, the effect of oil remains unknown.

Given the valuable contribution of studies into healthcare financing among countries around the world, the lack of evidence on the effect of falling oil prices on healthcare expenditure and any attempts by countries to utilize alternative sources of financing to shield their healthcare system against oil prices fluctuations, especially in OPEC countries, creates a scientific gap. Advancing the literature by contributing to this topic would be a valuable contribution potentially filling certain knowledge gaps in the literature and would be a crucial input into planning healthcare financing in the future.

The OPEC was established in 1960 with the ultimate mission to stabilize oil markets via coordinating policies and regulating oil production for its members, so that each of its members is limited to a specific level of oil production. This is in addition to a continuous revision of each member’s increase or decrease in the proportion of production based on market economic changes (Kisswani et al., Citation2022). Such control of production is mainly to secure an efficient, economical, and regular supply to consumers (Kisswani et al., Citation2022). Since OPEC was established, 16 countries have taken membership at different times, and some have suspended their membership for some time or permanently. At the time of conducting this study, there are 13 member countries (OPEC, Citation2022b).

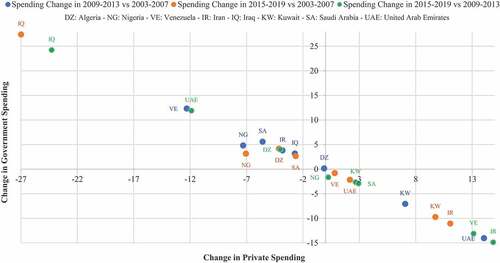

In OPEC countries, which rely predominantly on oil for financing their budgets, governments’ average healthcare expenditure between 2009 and 2013, the period post the 2008 fall in oil prices (hereafter called “post-2008”), decreased compared to that between 2003 and 2007, which precedes the 2008 fall in oil prices (hereafter called “post-2002”), in Venezuela, Nigeria, SA, Iran, Iraq, and Algeria (see the northwest quadrant of Figure ; World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2022). This meant the shifting of burdens on private expenditure, including individuals, which might have adverse effects on people’s health and healthcare systems in the long-run. This should have made governments prudent in their healthcare financing and prevented them from relying predominantly on oil for financing due to its volatility. However, whether the fall in oil prices in 2014 affected the OPEC countries’ healthcare financing between 2015 and 2019, the period post the 2014 fall in oil prices (hereafter called “post-2014”), and whether the financing in this period shifted away from the dependence on oil remain open questions in the literature.

Figure 1. Change in government and private spending on healthcare as a % of total spending on healthcare.

Financing healthcare systems differ among the OPEC countries; those from the Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMIC) tend to have a large proportion of their healthcare systems financed privately (Iraq, Nigeria, Venezuela, Algeria, and Iran). By contrast, those from the High-Income Countries (HIC) tend to finance the majority of their systems via the government (Kuwait, SA, and UAE). In Iraq, the country's constitution ensures a universal right to healthcare, where the public sector provides free healthcare services to citizens, primarily financed from oil revenues (Jaff et al., Citation2018), and the private sector supplements the public sector in curative care (Al Hilfi et al., Citation2013), which now finances most of the system (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2022). The Nigerian healthcare system is financed in different ways but mainly via out-of-pocket (OOP; Uzochukwu et al., Citation2015). The Venezuelan healthcare system is fragmented between private and public funding with a growing share of OOP that is one of the highest in the world (Atun et al., Citation2015; Roa, Citation2018). Algeria provides free healthcare services for all citizens, and the majority of the system finances are derived from the government (Expat Financial, Citation2018; Scherer et al., Citation2018). In Iran, the system is financed in different ways, such as public funds, social healthcare insurance, private insurance, and OOP, where government support is through public revenue (Dizaj et al., Citation2019; Zare et al., Citation2014), and the system is mostly financed privately with a high OOP share (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2022; Zakeri et al., Citation2015). In Kuwait, the system provides free healthcare services to citizens, financed by the government (Alkhamis et al., Citation2014; Khoja et al., Citation2017), with a low private share financed through OOP (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2022, Alkhamis et al., Citation2014). Similar to SA, where the government ensures free public services to all Saudis and non-Saudis employed publicly as well as their dependents, the private sector provides free services mainly to cover privately employed people and their dependents, which is financed via their employers (Al Mustanyir et al., Citation2022). In the UAE, the government mainly finances the system, where most Emirates are served by the Ministry of Health, and private insurance covers health services more in the Emirates of Abu Dhabi and Dubai (Andersen, Citation2013; Koornneef et al., Citation2017).

2. Methodology

Data were categorized into three groups for statistical comparison: i) post-2014, ii) post-2008, and iii) post-2002. To understand governments’ healthcare financing post 2014 and whether it shifted away from the dependence on oil, first, the healthcare financing post-2014 was compared to that post-2008. Thereafter, healthcare financing post-2014 was compared to that post-2002, which was a stable period, unaffected by falling oil prices. This should provide a comprehensive insight into the financing situation after 2014. In this study, moving healthcare financing away from the dependence on oil is defined as the increase in government healthcare financing post-2014, a time of falling oil prices, given the condition that oil production is controlled. In addition, as the fall in oil prices occurred in just half of 2008 and 2014, these years were excluded from the comparison to avoid bias in the study data and groups.

The shares of government and private expenditure on healthcare to total healthcare expenditure were used as indicators for analysis, which reflect their capacity to demonstrate government healthcare financing post-2014, compared to post-2008 and 2002. Moreover, this study used healthcare expenditure aggregation as opposed to absolute values, which is usually used for a given country or specific disease (Turner, Citation2017; Zhang et al., Citation2010). Aggregates are appropriate if the case is comparison across countries as it permits the investigation of different institutional systems and explanatory variables (Gerdtham & Jönsson, Citation2000). As this study compares expenditure on healthcare across countries, aggregation is appropriate because it can reveal relevant changes in the shares of government and private expenditure on healthcare even if the absolute values remain unchanged (Loughnane et al., Citation2019). Moreover, this study used data from the global health expenditure database of the World Health Organization (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2022).

The mean changes in healthcare expenditure post-2014 along with the expenditure post-2008 and 2002 were analyzed. The Welch’s t-test was employed to assess the difference in healthcare expenditure in the aforementioned periods. The test was used due to its capability to measure the significance of the difference between the means (Burke et al., Citation2014). The test was also deemed appropriate for measuring mean changes of two independent groups, especially if a small sample was involved, as in this study (Delacre et al., Citation2017). A two-sided t-test was conducted, and significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels was indicated in the results. The comparison of means calculates the differences between the observed means in two independent samples. The significance value (p-value) of the difference is reported, which is the probability that there is a difference between the samples if the null hypothesis is true, and the null hypothesis is the hypothesis that the difference is 0. Statistical analysis was performed using the STATA software version 14.0.

To ensure best practices and to investigate whether governments healthcare financing post-2014 shifted away from the dependence on oil, OPEC countries were chosen as the study sample. This was done to control any effect on governments’ financing strategy, which could otherwise crucially bias government spending and study comparison. This occurs when governments offset the drop in oil prices in 2014 by increasing oil production to collect more taxes or increase revenue from the government-owned oil companies. This is because producers out of OPEC countries are independent in their decisions on oil production (Kisswani et al., Citation2022), and this should be controlled for better analysis and comparison between the countries.

This study included OPEC countries that have held membership for the entire study period (2003–2019). These countries are Algeria, Nigeria, Venezuela, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, SA, and UAE (OPEC, Citation2022b). Owing to the lack of access to Libya’s healthcare data since 2012, Libya was excluded even though it held membership for the study period (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2022).

3. Results

The comparison of mean results indicates that the share of government healthcare expenditure to total expenditure on healthcare in Algeria post-2014 declined significantly by 4% (p = 0.00) compared to the period post-2008 and declined significantly by 4.1% compared to the period post-2002 (p = 0.04; see, Figure and Table ). Concurrently, the mean change of private healthcare expenditure to total expenditure on healthcare post-2014 increased significantly by 4% compared to post-2008 (p = 0.00) and increased significantly by 4.1% compared to post-2002 (p = 0.04).

Table 1. Welch’s t-test results for changes in healthcare spending in 2015–2019 compared to 2009–2013 and 2003–2007

In Nigeria, the government healthcare expenditure post-2014 increased slightly by 0.2% (p = 0.77) compared to the period post-2008 and declined significantly compared to that post-2002 by 7% (p = 0.00). At the same time, the private expenditure on healthcare post-2014 decreased 1.6% compared to post-2008 (p = 0.35), and increased 3.1% compared to post-2002 (p = 0.14).

In Venezuela, the government healthcare expenditure post-2014 increased significantly by 13.1% (p = 0.01) compared to post-2008 and increased slightly by 0.8% (p = 0.85) relative to post-2002. Meanwhile, in the same period, the private healthcare expenditure in 2014 decreased significantly by 13.1% (p = 0.01) compared to post-2008 and decreased 0.8% compared to post-2002 (p = 0.86).

In Iran, the government healthcare expenditure post-2014 increased significantly by 14.8% (p = 0.00) compared to post-2008 and increased significantly by 11% compared to post-2002 (p = 0.00). In the same period, the private healthcare expenditure decreased significantly by 14.8% (p = 0.00) compared to post-2008 and decreased significantly by 11% compared to post-2002 (p = 0.00).

In Iraq, the mean change in the government healthcare expenditure to total expenditure on healthcare post-2014 decreased significantly by 24.2% compared to post-2008 (p = 0.05), and decreased significantly by 27% compared to post-2002 (p = 0.00). Concurrently, the mean change of the private healthcare expenditure post-2014 increased significantly by 24.22% relative to post-2008 (p = 0.05) and increased significantly by 27.4% relative to post-2002 (p = 0.00).

In Kuwait, the government healthcare expenditure post-2014 increased significantly by 2.6% (p = 0.01) compared to post-2008 and increased significantly by 9.7% compared to post-2002 (p = 0.00). At the same time, the private healthcare expenditure post-2014 decreased significantly by 2.6% (p = 0.01) compared to post-2008 and decreased significantly by 9.7% compared to post-2002 (p = 0.00).

In SA, the government healthcare expenditure post-2014 increased significantly by 2.9% compared with post-2008 (p = 0.10) and decreased significantly by 2.6% compared with post-2002 (p = 0.02). Meanwhile, in the same period, the private healthcare expenditure post-2014 decreased significantly by 2.9% compared with post-2008 (p = 0.10) and increased significantly by 2.6% compared with post-2002 (p = 0.02).

In the UAE, the government healthcare expenditure post-2014 decreased significantly by 11.8% compared to post-2008 (p = 0.03) and increased 2.1% compared to post-2002 (p = 0.65). At the same time, the private healthcare expenditure post-2014 increased significantly by 11.8% compared to post-2008 (p = 0.03) and decreased 2.1% compared to post-2002 (p = 0.65; see, Figure and Table ).

4. Discussion

The study results showed that the effect of the fall in oil prices on government healthcare financing differed among the OPEC countries and in the periods of comparison, with the majority having not shifted from the dependence on oil yet. Surprisingly, with the expected pressure on government healthcare spending in OPEC countries in those from LMIC, results indicated some succeeded in shielding spending against the fall in oil prices, where others from the HIC did not. The share of government healthcare financing to total expenditure on healthcare appears in the northwest quadrant of Figure .

Iran and Venezuela, two countries from the LMIC, shifted their governments’ healthcare financing away from dependence on oil, where their government healthcare financing post-2014 increased compared to both periods (see, Figure ). In Iran, government healthcare financing increased notably compared to other countries; this could be attributed to the country having been dealing with economic sanctions, which may have encouraged the government to utilize different approaches for financing government healthcare. The same could be applicable to Venezuela, in which case the country has been facing economic sanctions; government healthcare financing did not respond to the fall in oil prices post-2014, even though the response was at lower levels compared to Iran. This has shifted the healthcare system financing from private to government expenditure, which may have reduced the burden on individuals who finance a significant share of the system in both countries (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2022; Roa, Citation2018; Zakeri et al., Citation2015), given the high levels of inflation in both countries (Pittaluga et al., Citation2021; Statista, Citation2022; Trading Economics, Citation2022).

Unsurprisingly, the analysis revealed that government healthcare financing post-2014 did not shift from dependence on oil in Iraq and Algeria compared to both periods (post-2008 and 2002). Government healthcare financing responded significantly to the fall in oil prices, where reductions in such financing prevailed in both periods, with notable reductions in Iraq influenced by war and economic instability (Al Hilfi et al., Citation2013; Lafta & Al-Nuaimi, Citation2019). The high dependence on oil moved the healthcare system to be privately financed; the study data showed significant increases in private healthcare financing in both countries for both periods. This is inappropriate for the system as it may leave out individuals with insufficient access to healthcare due to the unaffordability. Similar to the situation in Nigeria, government healthcare financing decreased significantly compared to post-2002 and increased marginally compared to post-2008. This may also indicate that the government is still dependent on oil to finance their system with no insight to increase their healthcare spending given their very high proportion of private spending and the dwindling economy (see the southeast quadrant of Figure ; Otu, Citation2018).

From the HIC, Kuwait did not experience reductions post-2014 compared to both periods (post-2008 and 2002), indicating that the government is less influenced by the fall in oil prices (see, Figure ). However, this does not necessarily indicate that the financing shifted from the dependence on oil because Kuwait has the smallest population among all the other countries involved in the study and is the fourth largest oil producer among the OPEC countries (OECD, Citation2022; Statista, Citation2020). This has reduced the burden on private financing, including on individuals, which may have allowed them greater access to healthcare.

Healthcare expenditures in the UAE and SA were unexpectedly influenced given their strong economies. Analysis revealed that the government healthcare financing in the UAE did not move from dependence on oil compared to post-2008, with a significant reduction in such financing, but increased slightly compared to post-2002. Similar to SA, government healthcare financing decreased significantly compared to post-2002, but increased significantly compared to post-2008. Within these countries, government healthcare financing reductions are mostly higher than the increases in either period (post-2008 or −2002). Such results suggest that shifting government healthcare financing from oil is still rudimentary in both countries.

Iran and Venezuela exhibited positive experiences in financing their healthcare systems because the majority of their systems were financed by the government (more than 50% in both countries; World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2022), which makes increasing such finances difficult during falling oil prices, especially for a country with a general budgetary system predominantly relying on oil and at a time of economic sanctions. By contrast, with the very low share of government healthcare financing to total healthcare financing in Nigeria and Iraq (less than 20% and 40%, respectively; World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2022), which may have yielded them higher chances of increasing their government financing, their government healthcare financing showed significant reductions.

Previous studies identified higher spending on healthcare in HIC compared to LMIC, but the percentage increase in healthcare spending seemed higher in LMIC (Dieleman et al., Citation2017b, Citation2017a; M. M. Jakovljevic, Citation2016). In line with these, the resilience to the fall in oil prices, and shifting dependence on oil by some LMIC such as Iran and Venezuela may indicate increasing their chance to spend more on healthcare in the future and could be at levels exceeding the average healthcare spending of LMIC. By contrast, healthcare spending in some rich Arab countries may lag behind that of the HIC due to their high reliance on oil. In the long term, this may lead some LMIC to reach or exceed the healthcare spending by some HIC unless such high reliance on oil for financing is reversed.

With the world moving to more transition in financing their healthcare systems, BRICS nations tend to transform to more investments in healthcare to increase and ensure more stability in their healthcare expenditures, given the serious challenges facing these nations such as aging and burden of communicable diseases (Jakovljevic et al., Citation2022, Citation2017). Countries that experienced instability in government healthcare financing from LMIC and HIC in this study are no exception to such challenges. Their predominant dependence on oil for financing and no healthcare financing transition insight in the future should expose their healthcare systems to more challenges in the long term.

Not long after the world economy stabilized in 2018 and 2019 (Loughnane et al., Citation2019), the COVID-19 pandemic led to further global disruption, which decreased oil prices to the lowest levels in the past three decades (Macrotrends, Citation2022). The outbreak of war in Ukraine caused oil prices to rebound, but prices have fluctuated significantly between $80 and $130 (OPEC, Citation2022a). Given such continuous economic and political developments, as well as the high instability and sensitivity of oil to markets change and the economic uncertainty oil creates, which was perceived historically (Onour & Abdo, Citation2022; Bayati & bin Nasser, Citation2022; Qin et al., Citation2020), and the global transformation to green energy (Su et al., Citation2022), oil-dependent countries should release their healthcare financing from dependence on oil to ensure stability in their healthcare systems.

5. Conclusion

This study examined the effect of the fall in oil prices on OPEC countries’ healthcare financing post-2014 and whether government healthcare financing shifted from the dependence on oil. The effect differed among countries; some moved from the dependence on oil given their higher proportion of government healthcare financing to total healthcare financing, while others could not, prompting them to shift their financing to private spending, including individuals.

Keeping the dependence on oil for financing and shifting the burdens to private expenditure during falling oil prices could solve the issue and absorb the effect temporarily. However, this may have long-term adverse effects. The short-sighted nature of shifting healthcare financing to private expenditure during falling oil prices to control government finances and keeping governments dependent on oil are likely to worsen healthcare outcomes over time and increase healthcare needs unless such patterns are reversed. Moreover, population growth, increases in aging, and people with chronic diseases may lead to more challenges. Thus, with the anticipated recovery of economies and healthcare systems, the increased demand for healthcare could be challenged, which, in turn, may require more healthcare financing.

The results of this study suggest that countries across the world that depend on oil for financing their healthcare systems try to minimize the reliance on such sources due to their high volatility and to bolster their healthcare finance resources. It is also suggested that the focus should not be on short-term plans, such as shifting the burden to private expenditure. This study also suggests that further investigation of Iran and Venezuela’s positive experience in financing their healthcare systems must be conducted to understand the potential changes that were applied to their healthcare systems and to understand how they shielded their financing from the fall in oil prices.

Highlights

The fall in oil prices in 2014 put the OPEC countries’ public finances under significant strain.

The effect of the fall in oil prices on governments’ healthcare financing has been investigated to determine whether financing shifted from the dependence on oil.

The effect differed among OPEC countries, but most still depend on oil for financing.

Healthcare financing shifted to private financing in many countries.

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Salem Al Mustanyir

Dr. Salem Al Mustanyir is a senior economist with experience in different public and private organizations in Saudi Arabia and abroad in departments of accounting, finance, investment, insurance, and risk management. His research activities focus on health economics and financing, policy impact assessment studies, labor market, energy, education, smart cities, economics of data, investment in artificial intelligence, and building public and private performance indices (e.g., education, healthcare, population, labor, commerce and finance, infrastructure, environment sustainability, and social equalization).

References

- Al Hilfi, T. K., Lafta, R., & Burnham, G. (2013). Health services in Iraq. The Lancet, 381(9870), 939–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60320-7

- Ali, A. J. (2021). Volatility of oil prices and public spending in Saudi Arabia: Sensitivity and trend analysis. International Journal of Economics and Policy, 11(1), 165–172. https://doi.org/10.32479/ijeep.10601

- Alkhamis, A., Hassan, A., & Cosgrove, P. (2014). Financing healthcare in Gulf Cooperation Council countries: A focus on Saudi Arabia. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 29(1), e64–e82. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2213

- Al Mustanyir, S., Turner, B., & Mulcahy, M. J. (2022). The population of Saudi Arabia’s willingness to pay for improved level of access to healthcare services: A contingent valuation study. Health Science Reports, 5(3), e577. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.577

- Andersen, B. J. (2013). The effects of preventive mental health programmes in secondary schools. World Hospitals and Health Services, 49(4), 8–11. https://doi.org/10.25142/spp.2016.003

- Atun, R., De Andrade, L. O. M., Almeida, G., Cotlear, D., Dmytraczenko, T., Frenz, P., Garcia, P., Gómez-Dantés, O., Knaul, F. M., Muntaner, C., de Paula, J. B., Rígoli, F., Serrate, P. C. F., & Wagstaff, A. (2015). Health-system reform and universal health coverage in Latin America. The Lancet, 385(9974), 1230–1247. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61646-9

- Barr, B., Taylor-Robinson, D., Scott-Samuel, A., McKee, M., & Stuckler, D. (2012). Suicides associated with the 2008-10 economic recession in England: Time trend analysis. BMJ, 345(aug13 2), e5142. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e5142

- Bayati, Y. F. K. A. L., & Bin Nasser Bin Al-Hamid, Z. (2022). The impact of oil price fluctuations on the general budget and the Iraqi gross domestic product form the period 2010 to 2020. Journal of Business and Management Studies, 4(3), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.32996/jhsss.2022.4.3.11

- Budhdeo, S., Watkins, J., Atun, R., Williams, C., Zeltner, T., & Maruthappu, M. (2015). Changes in government spending on healthcare and population mortality in the European Union, 1995–2010: A cross-sectional ecological study. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 108(12), 490–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076815600907

- Burke, S., Thomas, S., Barry, S., & Keegan, C. (2014). Indicators of health system coverage and activity in Ireland during the economic crisis 2008–2014: From ‘more with less’ to ‘less with less’. Health Policy, 117(3), 275–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.07.001

- Charfeddine, L., & Barkat, K. (2020). Short-and long-run asymmetric effect of oil prices and oil and gas revenues on the real GDP and economic diversification in oil-dependent economy. Energy Economics, 86(Article), 104680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2020.104680

- Delacre, M., Lakens, D., & Leys, C. (2017). Why psychologists should by default use Welch’s t-test instead of Student’s t-test. International Review of Social Psychology, 30(1), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.5334/irsp.82

- Dieleman, J., Campbell, M., Chapin, A., Eldrenkamp, E., Fan, V. Y., Haakenstad, A., Kates, J., Liu, Y., Matyasz, T., Micah, A., Reynolds, A., Sadat, N., Schneider, M. T., Sorensen, R., Abbas, K. M., Abera, S. F., Kiadaliri, A. A., Ahmed, M. B., Alam, K., … Murray, C. J. L. (2017b). Future and potential spending on health 2015–40: Development assistance for health, and government, prepaid private, and out-of-pocket health spending in 184 countries. The Lancet, 389(10083), 2005–2030. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30873-5

- Dieleman, J., Campbell, M., Chapin, A., Eldrenkamp, E., Fan, V. Y., Haakenstad, A., Kates, J., Liu, Y., Matyasz, T., Micah, A., Reynolds, A., Sadat, N., Schneider, M. T., Sorensen, R., Evans, T., Evans, D., Kurowski, C., Tandon, A., Abbas, K. M., … Murray, C. J. L. (2017a). Evolution and patterns of global health financing 1995–2014: Development assistance for health, and government, prepaid private, and out-of-pocket health spending in 184 countries. The Lancet, 389(10083), 1981–2004. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30874-7

- Dizaj, J. Y., Anbari, Z., Karyani, A. K., & Mohammadzade, Y. (2019). Targeted subsidy plan and Kakwani index in Iran health system. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 8, 98. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_16_19

- Economy, C. (2020). Deficit: Countries comparison. https://countryeconomy.com/deficit

- Edney, L. C., Haji Ali Afzali, H., Cheng, T. C., & Karnon, J. (2018). Mortality reductions from marginal increases in public spending on health. Health Policy, 122(8), 892–899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.04.011

- Expat Financial. (2018). Algeria healthcare system & insurance options for expats. https://expatfinancial.com/healthcare-information-by-region/african-healthcare-system/algeria-healthcare-system/

- García Ruiz, A. J., García-Agua Soler, N., Martín Reyes, Á., & García Ruiz, A. J. (2019). Crisis, public spending on health and policy. Revista Espanola de Salud Publica, 93, e201902007. https://europepmc.org/article/med/30783077

- Gerdtham, U.-G., & Jönsson, B. (2000). International comparisons of health expenditure: Theory, data and econometric analysis. In Handbook of health economics (pp. 11–53). Elsevier.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0064(00)80160-2

- Global Economy. (2019). Oil revenue: Country rankings. https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/oil_revenue/

- Grima, S., Spiteri, J. V., Jakovljevic, M., Camilleri, C., & Buttigieg, S. C. (2018). High out-of-pocket health spending in countries with a Mediterranean connection. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 145. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00145

- Jaff, D., Tumlinson, K., & Al-Hamadan, A. (2018). Challenges to the Iraqi health system call for reform. Journal of Health Systems, 3(2), 9–12. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335965009_Challenges_to_the_Iraqi_Health_System_Call_for_Reform

- Jakovljevic, M. B. (2015). BRIC’s growing share of global health spending and their diverging pathways. Frontiers in Public Health, 3, 135. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2015.00135

- Jakovljevic, M. M. (2016). Comparison of historical medical spending patterns among the BRICS and G7. Journal of Medical Economics, 19(1), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.3111/13696998.2015.1093493

- Jakovljevic, M., Lamnisos, D., Westerman, R., Chattu, V. K., & Cerda, A. (2022). Future health spending forecast in leading emerging BRICS markets in 2030: Health policy implications. Health Research Policy and Systems, 20(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-022-00822-5

- Jakovljevic, M., Liu, Y., Cerda, A., Simonyan, M., Correia, T., Mariita, R. M., Kumara, A. S., Garcia, L., Krstic, K., & Osabohien, R. (2021). The Global South political economy of health financing and spending landscape: History and presence. Journal of Medical Economics, 24(sup1), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2021.2007691

- Jakovljevic, M., Potapchik, E., Popovich, L., Barik, D., & Getzen, T. E. (2017). Evolving health expenditure landscape of the BRICS nations and projections to 2025. Health Economics, 26(7), 844–852. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3406

- Jakovljevic, M., Timofeyev, Y., Ranabhat, C. L., Fernandes, P. O., Teixeira, J. P., Rancic, N., & Reshetnikov, V. (2020). Real GDP growth rates and healthcare spending: Comparison between the G7 and the EM7 countries. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00590-3

- Johnston, B. M., Burke, S., Barry, S., Normand, C., Fhallúin, M. N., & Thomas, S. (2019). Private health expenditure in Ireland: Assessing the affordability of private financing of health care. Health Policy, 123(10), 963–969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.08.002

- Karanikolos, M., Heino, P., McKee, M., Stuckler, D., & Legido-Quigley, H. (2016). Effects of the global financial crisis on health in high-income OECD countries: A narrative review. International Journal of Health Services, 46(2), 208–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020731416637160

- Keane, C., Regan, M., & Walsh, B. (2021). Failure to take-up public healthcare entitlements: Evidence from the medical card system in Ireland.Social Science and Medicine, 281, 114069. Article 114069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114069

- Keegan, C., Thomas, S., Normand, C., & Portela, C. (2013). Measuring recession severity and its impact on healthcare expenditure. International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economics, 13(2), 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-012-9121-2

- Khoja, T., Rawaf, S., Qidwai, W., Rawaf, D., Nanji, K., & Hamad, A. C. (2017). Health care in gulf cooperation council countries: A review of challenges and opportunities. Cureus, 9(8), e1586. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.1586

- Kisswani, K. M., Lahiani, A., & Mefteh-Wali, S. (2022). An analysis of OPEC oil production reaction to non-OPEC oil supply. Resources Policy, 77(Article), 102653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102653

- Koornneef, E., Robben, P., & Blair, I. (2017). Progress and outcomes of health systems reform in the United Arab Emirates: A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2597-1

- Lafta, R. K., & Al-Nuaimi, M. A. (2019). War or health: A four-decade armed conflict in Iraq. Medicine, Conflict, and Survivial, 35(3), 209–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/13623699.2019.1670431

- Lindström, M., & Giordano, G. (2016). The 2008 financial crisis: Changes in social capital and its association with psychological wellbeing in the United Kingdom - A panel study. Social Science and Medicine, 153, 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.008

- Loughnane, C., Murphy, A., Mulcahy, M., McInerney, C., & Walshe, V. (2019). Have bailouts shifted the burden of paying for healthcare from the state onto individuals? Irish Journal of Medical Science, 188(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-018-1798-x

- Macrotrends. (2022). Crude oil prices - 70 year historical chart. https://www.macrotrends.net/1369/crude-oil-price-history-chart#google_vignette

- Martinez, L. R. (2022). Natural resource rents, local taxes, and government performance: Evidence from Colombia. Working paper, University of Chicago.

- Mead, D., & Stiger, P. (2015). The 2014 plunge in import petroleum prices: What happened? US Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-4/pdf/the-2014-plunge-in-import-petroleum-prices-what-happened.pdf

- OECD. (2019). Fuel taxes by country. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development OECD. https://afdc.energy.gov/data/10327

- OECD. (2022). OPEC countries 2022: World population review. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/opec-countries

- Onour, I. A., & Abdo, M. M. (2022). Sensitivity of crude oil price change to major global factors and to the Russian–Ukraine war crisis. Journal of Sustainable Business and Economics, 5(2), 69. Article 4641. https://doi.org/10.30564/jsbe.v5i2.4641.

- OPEC. (2022a). OPEC basket price. https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/data_graphs/40.htm

- OPEC. (2022b). OPEC member countries. https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/about_us/25.htm

- Otu, E. (2018). Geographical access to healthcare services in Nigeria: A review. Journal of Integrative Humanism, 10(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3250011

- Pappa, E., Kontodimopoulos, N., Papadopoulos, A., Tountas, Y., & Niakas, D. (2013). Investigating unmet health needs in primary health care services in a representative sample of the Greek population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(5), 2017–2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10052017

- Pittaluga, G. B., Seghezza, E., & Morelli, P. (2021). The political economy of hyperinflation in Venezuela. Public Choice, 186(3), 337–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-019-00766-5

- Qin, M., Su, C.-W., Hao, L.-N., & Tao, R. (2020). The stability of US economic policy: Does it really matter for oil price? Energy, 198(Article), 117315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.117315

- Reshetnikov, V., Arsentyev, E., Bolevich, S., Timofeyev, Y., & Jakovljević, M. (2019). Analysis of the financing of Russian health care over the past 100 years. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(10), 1848. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16101848

- Roa, A. C. (2018). The health system in Venezuela: A patient without medication? Cadernos de Saude Publica, 34, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2022.2077794

- Scherer, M. D. A., Conill, E. M., Jean, R., Taleb, A., Gelbcke, F. L., Pires de Pires, D. E., Joazeiro, E. M. G. C., & Coletiva, S. (2018). Desafios para o trabalho em saúde: Um estudo comparado de Hospitais Universitários na Argélia, Brasil e França [Challenges for health: A comparative study of University Hospitals in Algeria, Brazil and France]. Science & Public Health, 23, 2265–2276. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232018237.08762018

- Sede, P. I., & Osifo, O. (2017). Impact of government healthcare financing on tuberculosis in Nigeria. Yobe Journal of Economics, 4(2), 93–105. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325503445_IMPACT_OF_GOVERNMENT_HEALTHCARE_FINANCING_ON_TUBERCULOSIS_IN_NIGERIA

- Statista. (2020). Daily production of crude oil in OPEC countries from 2012 to 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/271821/daily-oil-production-output-of-opec-countries/

- Statista. (2022). Venezuela: Inflation rate from 1985 to 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/371895/inflation-rate-in-venezuela/

- Su, C. W., Chen, Y., Hu, J., Chang, T., & Umar, M. (2022). Can the green bond market enter a new era under the fluctuation of oil price? Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 87(3), 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2022.2077794

- Trading Economics. (2022). Iran inflation rate. https://tradingeconomics.com/iran/inflation-cpi

- Turner, B. (2017). The new system of health accounts in Ireland: What does it all mean? Irish Journal of Medical Science, 186(3), 533–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-016-1519-2

- Uzochukwu, B. S. C., Ughasoro, M. D., Etiaba, E., Okwuosa, C., Envuladu, E., & Onwujekwe, O. E. (2015). Health care financing in Nigeria: Implications for achieving universal health coverage. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice, 18(4), 437–444. https://doi.org/10.4103/1119-3077.154196

- World Bank. (2022). GDP (current US$). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2022). Global health expenditure database. https://apps.who.int/nha/database/Select/Indicators/en

- Zakeri, M., Olyaeemanesh, A., Zanganeh, M., Kazemian, M., Rashidian, A., Abouhalaj, M., & Tofighi, S. (2015). The financing of the health system in the Islamic Republic of Iran: A National Health Account (NHA) approach. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 29, 243. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4715399/

- Zare, H., Trujillo, A. J., Driessen, J., Ghasemi, M., & Gallego, G. (2014). Health inequalities and development plans in Iran; an analysis of the past three decades (1984–2010). International Journal for Equity in Health, 13(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-13-42

- Zhang, P., Zhang, X., Brown, J., Vistisen, D., Sicree, R., Shaw, J., & Nichols, G. A. (2010). Global healthcare expenditure on diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 87(3), 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2010.01.026