?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

In this paper, we study another approach to the profit shifting costs function of multinational profit shifting. First, we describe the modelling approaches of such costs functions and provide a synthesized analysis. More precisely, we investigate the involved resource costs that multinational firms incur through a tax-motivated reallocation of profit across tax jurisdictions. Second, we set up a simple theoretical model of a representative multinational firm within which we conceptualize our new cost function. We expand the literature by including a relationship between profit shifting costs and tax uncertainty. Furthermore, we describe the costs split, the property of our costs function and we express its parameters. Finally, we discuss our results in conjunction with the literature, emphasizing that profit shifting costs and tax uncertainty cause more concerns for developing countries than advanced economies.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

A description of your paper of NO MORE THAN 150 words suitable for a non-specialist reader, highlighting/explaining anything which will be of interest to the general public. Tax avoidance by multinational enterprises is still at the top of the current public debate. In particular, the cases of large companies such as Google, Apple, Amazon, Starbucks and others engaging in tax avoidance schemes have gained huge media attention. Understanding the anatomy of profit shifting by multinational enterprises is a major issue in tackling tax avoidance. Given this background, we critically assess the literature’s profit-shifting functions and other modelling approaches. We further provide a new function of profit shifting costs and expand the literature by including a relationship to tax uncertainty. Our study contributes to a better understanding of how profit shifting should be modelled in terms of thinking about government policies limiting the opportunities for multinational enterprises to artificially shift profits. However, more research is needed to inform the debate on effective policy design, including all possibly relevant stakeholders in the discussion.

1. Introduction

It is well known that profit shifting is a huge concern for tax authorities and international institutions. Indeed, in the public debate, policymakers and international organizations, such as the OECD, have pointed out that tax planning by multinationals through transfer pricing and profit shifting generate unintended competitive advantages over domestic companies (Nielsen et al., Citation2014, p. 2). In this regard, differences between countries in tax rates generate incentives for multinational enterprises (MNEs) to locate profits in low-tax jurisdictions (De Mooij et al., Citation2021, p. 49). However, the concerns with tax planning differ in advanced economies as compared to developing countries (De Mooij et al., Citation2021, p. 69). Developing countries may suffer in particular from these difficulties by seeing their tax base being eroded (De Mooij et al., Citation2021, p. 6). In 2013, with support from the G20 and individual governments, the OECD (Citation2013) launched its Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project to tackle international tax avoidance. Their aim is to make tax planning more transparent to all tax authorities concerned, requiring substance from both companies and countries (i.e. restoring taxation to the place where economic activities and value creation occur), closing off cross-border tax loopholes, and thus enhance revenue mobilization (Álvarez Martínez et al., Citation2022; Beer et al., Citation2018; Dharmapala, Citation2014; OECD, Citation2018).

For more clarity and conciseness, we recall that “profit shifting” refers to cross-border tax avoidance by multinational corporations (MNCs) to reduce their overall tax liability (De Mooij and Liu (Citation2020, p. 269); Dharmapala (Citation2019, p. 488)). Profit shifting can occur through the mispricing of transactions between related parties (that are vertically integrated entities within the same corporate structure or with shared ownership; De Mooij et al., Citation2021, p. 314). We notice that a large empirical literature on multinational shows that the profit shifting behaviour of MNCs responds to differences in corporate tax rates across countries Dharmapala (Citation2014, Citation2019); Heckemeyer and Overesch (Citation2017)Footnote1). In particular, several papers provide ample evidence for the presence of tax-motivated transfer mispricing (Beer et al., Citation2018, p. 5). Furthermore, there is a consensus in the literature that profit shifting activities within the multinational involve resource costs (see Haufler and Schjelderup (Citation2000), Huizinga and Laeven (Citation2008), Lohse and Riedel (Citation2013), and De Mooij and Liu (Citation2020) among others). However, despite the wealth of work on this topic, we have identified two important issues which are closely related, namely the various aspects of the cost function modelling approaches and the uncertainty of the tax and transfer pricing legislation.Footnote2 These two problems will be the subject of our study. We aim to chronologically analyse the cost function modelling approaches and to provide insights not only into the literature of profit shifting but also into the current policy debate on international taxation and development. Moreover, this paper fills this literature gap by modellingFootnote3 a new profit shifting costs function. Our investigation shows (for example) that there is no consensus in the literature regarding the main stakes and issues of profit shifting costs. Loretz and Mokkas (Citation2015) assumed that the real costs of profit shifting are unknown (Loretz & Mokkas, Citation2015, p. 5), whereas Hines and Rice (Citation1994) considered positive costs of transferring profits in either direction, which are assumed to be constant across all affiliates (Hines & Rice, Citation1990, p. 16). Beer et al. (Citation2018) considered that costs of profit shifting are likely to differ across MNCs of different operating scales or industry structures and across countries with a varying enforcement and administrative capacity (Beer et al., Citation2018, p. 10). Moreover, the empirical study of Huizinga and Laeven (Citation2008) provided evidence that European firms incur considerable costs in shifting profits internationally. On average, these costs are estimated to be 0.6% of the tax base of multinational firms in Europe (Huizinga & Laeven, Citation2008, p. 1179). Furthermore, these authors have shown that international profit shifting by European multinationals is significant and it leads to a substantial redistribution of national corporate tax revenues.

While research studies have not considered the mechanism through which profit shifting costs and tax uncertainty interact, our paper investigates, whether a functional relationship between both of them exists and could be modelled. Policymakers and international organizations recognized that tax certainty becomes a more important factor for economic agents (De Mooij et al., Citation2021, p. 345); (see communiqué G20 (Citation2016) and the OECD & IMF (Citation2017); (OECD & IMF, Citation2018); and (OECD & IMF, Citation2019)). In recent years, tax policy has been the single largest source of elevated U.S. policy uncertainty (Davis, Citation2017, p. 9). Likewise, uncertainty is the biggest concern in developing countries (Smith & Hallward-Driemeier, Citation2005).Footnote4 Moreover, tax uncertainty appears to have a more frequent impact in developing countries than in the OECD countries (OECD & IMF, Citation2018, p. 42).Footnote5 Niemann (Citation2011), in particular, has emphasised that legislation is not the only source of tax uncertainty. Rather, there is tax uncertainty even if the tax law remains unchanged (Niemann, Citation2011, p. 2). Moreover, if changes rationalize and simplify the tax system, overall uncertainty may actually be reduced in the longer term (OECD & IMF, Citation2017, p. 16). Firms face massive risk and uncertainty due to variability in policy actions that results from the weak capability for implementation of regulations (Hallward-Driemeier et al., Citation2016, p. 217). The literature on regulatory uncertainty is closely related to the tax uncertainty literature. The economic literature discusses the effects of tax uncertainty for more than two decades (Niemann, Citation2011, pp. 3–4).Footnote6 The term “regulations”, also called rules, are the primary tools that the government uses to implement laws and achieve policy goals (Sinclair & Xie, Citation2021, p. 5). Transfer pricing regulations for tax purposes usually prescribe particular standards or methods, which must be followed when determining transfer prices. Non-compliance with these regulations will often result in a tax adjustment and the imposition of fines and corresponding interest (Cooper et al., Citation2016, p. 4). Whitford (Citation2010) consider that regulatory uncertainty may come when the state, through taxation policy, tries to shape how firms distribute their profits (Whitford, Citation2010, p. 273). Even though the source, the domestic and the international dimensions of tax uncertainty are already addressed and documented (OECD & IMF, Citation2017, pp. 47–49), until now, the literature has considered both tax uncertainty and profit shifting cost two separate issues. To date, it seems that there is no paper in the literature that investigates the functional relationship between both of them.

The results of our paper show that, when the multinational firm engages in profit shifting via transfer mispricing by incurring profit shifting costs and if the tax uncertainty decreases, this will lead to higher profit shifting costs, whereas these costs are low if tax uncertainty increases. Thereby, our costs function modelling approach draws on two streams identified in our literature overview and it is basically close to Stöwhase (Citation2006) and De Mooij and Liu (Citation2020). To facilitate the understanding of the basic relationship and the interaction between profit shifting costs and tax uncertainty, we used a simple theoretical model of a representative multinational within which we conceptualize our cost function. We follow Mardan and Stimmelmayr (Citation2020) by assuming that governments maximize national welfare by non-cooperatively setting their tax rates.

This paper provides three major contributions to the current state of profit shifting research and policy debate. First, we describe and analyse the modelling approaches of the profit shifting costs and fill the gap in the literature. Because modelling of profit shifting is a critical factor by designing and implementing empirical studies’ strategies, the paper contributes to a better understanding of the anatomy of profit shifting costs. Most papers conducted in an empirical set-up draw theoretical models of optimal profit shifting that are used to develop their empirical strategy by considering profit shifting costs at a quick glance. Second, we extend the existing literature by modelling a new function taking into account the functional relationship between profit shifting costs and tax uncertainty. Third, our paper’s results and discussed issues may shed new light on profit shifting costs and tax uncertainty in the context of developing countries. To the best of our knowledge, it seems that a similar work has not been published before. This paper is the first attempt to provide such a theoretical investigation and modelling approach. Our study contributes to several areas of ongoing research related to transfer pricing and multinational behaviour, including reported profits (Bernard et al. (Citation2006), De Mooij et al. (Citation2021)), tax uncertainty (Niemann (Citation2011)), tax competition (Stöwhase (Citation2005, Citation2006)), and development (Fuest and Riedel (Citation2009, Citation2010), Hallward-Driemeier et al. (Citation2016), Mardan and Stimmelmayr (Citation2020)).

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 provides a brief overview of the profit shifting costs modelling approaches in the literature. We analyse and discuss the results and the main findings. Section 3 presents our theoretical model of a multinational firm with a new profit shifting costs function. In this section, we describe the property of the costs function, express its parameters, discuss the results and the propositions derived. In section 4, we discuss our results in conjunction with the literature and conclude by suggesting possible issues for future research.

2. On the functional models of the profit shifting cost function and tax uncertainty

In order to shed more light on the two problems considered in the introduction, namely the various aspects of the profit shifting cost function and its related models, and the tax uncertainty, we propose to deepen their contexts in this section. The literature in those areas is usually technical in nature, detailed, and complex. First of all, we will present the different aspects of the functional models of the cost function of profit shifting. Then, we will provide an analysis and discussion on the tax uncertainty and its relation with the profit shifting costs.

2.1. The profit shifting cost function. Our paper is at the crossing of at least three different strands of literature. In the research, profit shifting costs are closely related to the transfer pricing, in particular concerning tax-motivated profit shifting within multinational firms, tax anti-avoidance legislation, tax competition, and multinational investments. First, we aim to investigate what is known about profit shifting cost, its splits and delimitation. In the second step, we go over the question of how the modelling in the literature is performed.

Let’s begin with the pioneering study on transfer pricing by Kant (Citation1988), which represents a seminal academic paper. Kant (Citation1988) investigated the use of the transfer price mechanism by a multinational firm (MNF) to improve global welfare. In his model, he shows that an increased threat of penalty makes the MNF reduce the use of the transfer price mechanism. Increased surveillance of the transfer price by a government makes the multinational firm move its transfer price towards the arm’s lengthFootnote7 market price and checks fiscal abuses.

Kant’s model represents a multinational firm that produces and sells a final good to its affiliates in two countries. The parent exports part of its output in country 1 (source country) to its affiliate in country 2 (host country). It is assumed that, either due to international convention or otherwise, both countries adopt the same definition of arm’s length (AL) price. The author distinguishes between the transfer price charged , the AL market price

, and the transfer price which triggers a transfer price penalty with certainty

. Kant’s model differs from previous papers regarding MNF facing legal requirements on the transfer price. Thereby, the author sets up an infinite period model as the only possible source of a penalty. The transfer price regulation requirement, which obligates the MNF to charge a transfer price equal to the AL price, is not imposed for some a while, but this obligation can be always applied in later periods to provide the threat of regulation, thus discourage transfer pricing mispricing in the present. Then, the penalty

would be the effect on the present value of the entire future of the firm due to whatever regulation is imposed. Thus, there are some penalties of known size that can be imposed on the MNF with some probability denoted by

. The probability

of the imposition of a transfer price penalty depends on the divergence between

and

, and it may apply to either country. The attitude towards the MNF may change, for example, due to a change in the government in either country. Or, an existing government attitude may change due to its own study and policy review. The probability function can now be stated as

where is the shift parameter. It is assumed that the government’s estimate of arm’s length price is unchanged at

. But for

, in the situation of a more strict attitude, the probability of penalty increases. Thus, the probability of penalty function pivots upwards around

and the absolute value of its slope also increases. In symbols:

Before moving on to the next paper, we note that during the 1990s it was increasingly difficult for tax authorities to monitor the transfer pricing behaviour of multinationals. In the United States, serious doubts were raised by politicians and tax authorities about whether the price-oriented methods were still appropriate and whether they sufficed to preserve the U.S. tax base. The comparable profit method (CPM) as an instrument for regulating transfer prices was introduced (Schjelderup & Weichenrieder, Citation1999, pp. 817–818). For the subject matter hereof, the subsequent paper investigates multinational firms’ behaviour to shift their reported profits.

The second study by Hines and Rice (Citation1994) is widely cited in the literature on transfer pricing and profit shifting. Profit shifting costs are heavily emphasized in the general literature by the authors. The paper examines the closely related issue of the ability of U. S. firms to shift their reported profits and real business activities between high-tax foreign countries and low-tax foreign tax havens. The basic premise is that shifted income is determined by the tax incentive to move income in or out of the affiliate. The paper assumed that profit shifting is likely to be costly. Because firms may need to set up additional facilities to make transfer prices seem plausible, legal costs may be incurred, and (inefficient) intrafirm trades may take place to facilitate profit-shifting. In the same previous model, the authors consider that there are positive costs of transferring profits in either direction, which are assumed constant across all affiliates (Hines & Rice, Citation1990, p. 16). Let

represent before-tax profits earned (the true profits) in country

by factors located there. Suppose that a firm adjusts its transfer prices to allocate an additional profit

(the shifted profits) in profits to location

. The authors hypothesize that the marginal cost of shifting profits into a location is very small at first, but rises in proportion to the ratio

. Let

denote this factor of proportionality so that the total cost

of adjusting local reported profits is given by

Due to an increasing internationalisation of national economies, in particular through the growing importance of MNCs, several papers have addressed corporate tax competition in the presence of multinational firms’ cross-border profit shifting (see, Haufler and Schjelderup (Citation2000) and references therein). The subsequent paper deals with this concern.

In their paper, Haufler and Schjelderup (Citation2000) proposed an analytical framework as a simple two-period model of investment. The authors examined the international tax competition where countries can use the tax rate and the definition of the tax base as strategic variables. The study analysed the optimal taxation of corporate profits, transfer pricing, and profit shifting. To limit the extent of misdeclaration, the authors assumed that transfer pricing involves resource costs for the integrated firm. This is justified either by an increased probability of detection (see, e.g., Kant (Citation1988)) or by additional efforts that need to be taken to conceal the transfer pricing (mispricing) activity from tax authorities. The transaction costs incurred by the firm represent a pure waste of resources. So the paper’s framework is based on the joint assumptions that the only costs associated with the concealment cost , and that these costs depend only on the difference between the true and the declared price of the input traded. This concealment (transaction) cost function is a convex function

, where

is the transfer price satisfying some standard conditions, namely

=

,

=

,

.

The concealment cost was established as the most predominant and popular interpretation of profit shifting costs. Overall, the paper’s results indicate that it becomes optimal to allow only imperfect deduction of investment expenditures, thus distort the firm’s investment decision since this permits the government to lower the corporate tax rate and reduces the incentive to shift profits abroad. As to the literature on countries’ tax competition, several studies began to explore how income shifting may reduce the cost of capital in high tax countries, thereby making it a more attractive location for foreign investments (see, Stöwhase (Citation2006) and the main relevant references therein). The following paper investigates this topic.

Stöwhase’s (Citation2006) paper is related to the literature on tax competition, profit shifting and discrete investment. The author investigates how an exogenous change in the costs of profit shifting affects equilibrium tax rates between two competing countries by introducing the possibility that the multinational can shift a fraction of its profits out of the country where the production plant is located. In particular, the paper analyses how a change in the cost parameter affects multinationals’ tax payments and the tax revenue of the low and high tax countries. In this theoretical framework, countries and

levy a source tax on the profits declared within their borders. A multinational firm that produces in only one of the two countries may, at some costs, reduce its tax payments in the high tax country by declaring a fraction

of its profits in the low tax country

where the sales-office is located. The author models profit shifting between a high tax and a low tax country in a very similar way to Stöwhase (Citation2005) by assuming that multinational shifting activities involve resource costs to the firm and that the (non-deductible) total costs of misreporting increase linearly with the tax base and is given by,

where the parameter is defined as the fraction of the tax base that is misreported. The parameter

is exogenously given and it describes the general costs of misreporting activities. This former parameter can also be related to the degree of globalization or to the tax codes of the two countries. The author follows Kant (Citation1988); Haufler and Schjelderup (Citation2000), making the standard assumption that the resource costs are a convex function of the parameter

, and justifies this by additional efforts that need to be made in order to conceal the misreporting activity from tax authorities. Stöwhase (Citation2006) shows that profit shifting costs increase with

. Accordingly, low values of

may either depict a situation in which increased globalization creates generous opportunities for the firm to undertake misreporting activities or a situation where there is a number of loopholes in the national tax codes that make it rather easy to shift profits. One of the main results is that higher costs of profit shifting lead to an increase in both the multinational firm’s tax payments and the high tax country’s tax revenue, whereas, to a decrease of low tax country’s tax revenue. A further important result is that a reduction in the costs of profit shifting will typically harm the multinational firm. Only if profits can be shifted rather easily and costless from one country to the other, the multinational firm will be better off compared to the case without profit shifting. Looking at EU multinationals, typically active in several countries, one of the most influential papers is by Huizinga and Laeven (Citation2008), who investigate the opportunities and incentives generated by international tax differences for international profit shifting by the EU multinationals.

Huizinga and Laeven’s (Citation2008) research paper studies the overall extent of tax-motivated profit reallocation. The paper extends the conceptual framework developed by Hines and Rice (Citation1994) taking into account a more complex version of the overall pattern of tax rates faced by all the affiliates of the MNC. The theoretical model considers an MNC whose establishments operate in several countries. The multinational can manipulate its transfer prices for international intra-firm transactions to shift profits into country

. This paper also considers that manipulating transfer prices is assumed to be costly, as the multinational needs to modify its books, and possibly its real trade and investment patterns, to be able to justify the distorted transfer prices to the tax authorities. Even if firms comply with transfer pricing regulations, they may face considerable costs in dealing with, for instance, documentation requirements (Huizinga & Laeven, Citation2008, p. 1166).

Total shifting expenses, , incurred by the multinational in country

are calculated as,

where represents the profits generated by the multinational firm in country

and

is the profit shifted into country

. The authors follow Hines and Rice (Citation1994) by assuming that the marginal cost of shifting profits rises in proportion to the ratio of shifted to generated profits with

being the factor of proportionality.

This functional form reflects that company’s accounts have to be distorted relatively less to accommodate profit shifting if true profits

are relatively large. Profit shifting costs are considered to be tax deductible in the country where they are incurred. The theoretical model of the authors shows that the international profit shifting by an individual multinational firm depends on its overall international structure, as well as on the tax incentives and the tax regime it faces in each of the countries where it operates (Huizinga & Laeven, Citation2008, pp. 1178–1180). The authors found evidence that European firms incur significant costs in shifting profits internationally and that international profit shifting leads to a substantial redistribution of national corporate tax revenues. In response to this serious issue, many countries have implemented policies to limit the extent of profit shifting by MNCs, for example, by incorporating the core of OECD Guideline into their domestic tax code, and include specific provisions according with their regulatory background (Rathke et al., Citation2020, p. 152). The next paper is a leading study which examines whether the existing and the strictness level of transfer pricing rules are instrumental in restricting shifting behaviour.

In their paper, Lohse and Riedel (Citation2013) empirically examine the link between multinational profit shifting and the existence of transfer pricing regulation, documentation requirements, and the disclosure extent of transfer pricing information in 26 European countries between 1999 and 2009. The study considered that price deviation between transfer price and AL market price incurs positive costs though as aggressive mispricing would, if challenged by the tax authorities, have a lower probability of being sustained by courts or may require more resources to defend the mispricing successfully. Furthermore, the structure of the costs plausibly depends on the countries’ transfer pricing laws. The stricter the laws, the higher the probability that mispricing will be challenged, which increases the concealment costs.Footnote8 The study’s theoretical model considers a representative MNF with two affiliates operating in countries and

that produce and sell an output

, with

. Affiliate

additionally produces an input good that is required for production by both affiliates and is sold to affiliate

at a transfer price

. The MNF may shift income between the affiliates by choosing a transfer price

which deviates from the input’s true value

. Formally, they choose a simple multiplicative formulation of the cost function,

where the function captures how the scope of the countries’ transfer pricing laws

affects the level of transparency in price setting behaviour and the costs profit shifting. It is assumed that

0 and

0,

and

may differ across countries. The function

captures the difference between the transfer price and the AL market price (they qualified the market price as the input’s true value) of the exported intermediate input. The authors followed Haufler and Schjelderup (Citation2000) by assuming that the cost function

is u-shaped in

, with a minimum at

:

, where

and

.

is assumed to be non-tax-deductible.Footnote9 The authors consider that the multiplicative formulation of the cost function

implies that tighter transfer pricing legislation increases the MNE’s absolute and marginal costs to engage in mispricing behaviour. The result shows that multinational profit shifting activities are significantly reduced when countries introduce or tighten transfer price documentation requirements. Specific transfer pricing penalties exert an additional dampening effect on income shifting behaviour. Further literature research examined rather the link between inspection policy and multinational firm behaviour. One obvious argument is the aim of tax authorities to combat profit shifting by avoiding undesirable side effects on multinational production and investment activities. In this regard, the following study is one of the important papers that analyses this issue.

The model of Nielsen et al. (Citation2014) investigated whether it should be preferable that tax authorities audit the deviation of the transfer price from the AL market priceFootnote10 rather than the amount of income shifted.Footnote11 Thereby, in addition to the concealment costs, they analyse the effects of higher tax authorities detection effort and increased tax law quality on profit shifting. Their theoretical model considers a multinational firm that produces in only one of two countries (a high and low tax jurisdictions) an intermediate input good at marginal cost

. The affiliate in country

exports the intermediate good with a surcharge

at price

to the affiliate in country

. The multinational firm shifts profit from affiliate

to affiliate

. Affiliate

wants to conceal the true cost of the input good

and does so by incurring costly concealment effort

. Based on the premise that it is costly for the firm to exert effort

to conceal transfer pricing manipulation, Nielsen et al. (Citation2014) defined on one hand the concealment (transaction) cost function by

, where

is a parameter for the quality of the transfer pricing regulation in the tax code and

is the concealment cost. Hence, a high

quality of transfer pricing rules will increase the related costs of concealing mispricing. Thus, the cost function

satisfies

. In addition, the authors made the assumption that the concealment costs are convex in concealment cost, i.e.,

,

, and that countries differ substantially when it comes to the transfer pricing regulation (Lohse et al., Citation2012).Footnote12 On the other hand, they considered that tax authorities try to reveal the true nature of the transaction by exerting detection effort

. If the tax authorities detect that the intermediate good

is over invoiced to shift income, firm

will be fined. The expression for the fine is

, where

is the (surcharge) difference between the transfer price and the AL market price.

is not decreasing in its arguments. The approach of the modelling profit shifting costs is based on the premise that the detection probability increases with the detection effort exerted by tax authorities, but decreases with the concealment effort of firms. We point out that the authors defined an additive function form of the concealment effort cost

and the expected fine

defined as follows,

where the probability is increasing in mispricing

, the detection effort

of the tax authorities, and the level of the intermediate good

; whereas, it is assumed decreasing by the firm’s concealment effort

. Therefore, we show that

and

.

Finally, this paper shows that profit shifting could be fought by improving the tax-law quality so that less room is left for inconsistency and tax loopholes. Such good tax-law quality unambiguously reduces profit shifting and the wasteful concealment effort. More investments in detection effort

by the tax authorities foster the concealment effort, has a (theoretically) ambiguous effect on profit shifting and leads to a more wasteful use of resources.

Another strand of literature investigated the effects of corporate taxes on the level of reported profits. The tax-induced difference in profit is interpreted as evidence for the existence of profit shifting. In line with this research area, the following paper argues that it is important to incorporate the impact of the investment decision on the analysis of profit shifting.

The model of Loretz and Mokkas (Citation2015) investigated the extent to which subsidiaries of multinational firms in 25 countries engage in profit shifting. In contrast to existing research, the paper models the effects of corporate taxes on profitability measured as the ratio of profits to total assets. In their theoretical framework, the authors present a model of a multinational enterprise (MNE) consisting of two entities, which operate in two different countries. The profits functions of the two subsidiaries are ,

. The MNE can transfer a part of its profits

from subsidiary 1 to subsidiary 2. However, this profit-shifting activity comes at a cost of,

where is a scaling parameter of the profit-shifting costs. Further, the costs depend only on

, for simplicity. The authors provide an intuitive explanation that the MNE might need to defend the level of profits, particularly in the high-tax country 1 (Loretz & Mokkas, Citation2015, p. 5). Although the authors consider that the real costs of profit shifting are unknown, they follow the literature (Hines and Rice (Citation1994); Huizinga and Laeven (Citation2008)) in assuming the profit-shifting cost by a convex function of

, so that additional profit shifting becomes more costly. The paper considers more generally that costs of profit shifting may be resource costs, such as hiring tax and transfer price experts to allocate accounting profits efficiently, or they may represent costs that the firm pays only if they are caught by the tax authorities. It is assumed that the profit-shifting costs are not deductible from the tax base of any of the subsidiaries. Following the paper, this assumption stands regardless of whether one interprets profit shifting as an illegal activity and the costs involved as the potential fines if caught, or as agency cost arising within the firm. Alternatively, the profit-shifting costs might simply be born by the parent company, thus not be included at the subsidiary level. The theoretical proposition predicts that if multinationals engage in profit shifting and if profit shifting is not too costly, then the reported pre-tax and post-tax profitability will be higher in the low tax country than subsidiaries resident in countries with higher tax rates.

International tax issues came into increased prominence after the global financial crisis of 2009 (see, De Mooij et al. (Citation2021) and Dharmapala (Citation2014)). These concerns have led to major new international initiatives to curb international tax avoidance—most notably the G20/OECD initiative on base erosion and profit shifting (OECD, Citation2015; see, Beer et al. (Citation2018)). It is important to note that measuring BEPS is a complex issue. Thus, there is a growing desire for policy-makers to try to measure BEPS (Álvarez Martínez et al., Citation2022, p. 168). In this regard, a broad stream of research provides several methodologies and instruments to estimate the magnitude of BEPS, such as, among others, by Dharmapala (Citation2014), IMF (Citation2014), OECD (Citation2015), UNCTAD (Citation2015), Bolwijn et al. (Citation2018), and Álvarez Martínez et al. (Citation2022). According to the method developed by UNCTAD-2015,Footnote13 profit shifting would amount to USD 200 billion annually for the world economy (Álvarez Martínez et al., Citation2022, p. 172) whereas, (Bolwijn et al., Citation2018) estimate revenue losses of around USD 100 billion annually for developing countries. Leaving aside the estimates for overall government revenue losses, a more systematic, not anecdotal assessment of BEPS practices at the firm level is difficult (UNCTAD, Citation2015, p. 192). A strand of literature is devoted to these initiatives and proposals, in particular by analysing the specific profit shifting channels. In this context, the next paper investigates the question of whether multinational firms optimize the use of different profit shifting channels jointly.

Nicolay et al. (Citation2017) present a novel development in the profit shifting and anti-avoidance literature. The authors investigated whether firms substitute different profit shifting strategies with one another if the channels’ specific costs change due to anti-avoidance legislation. It is considered that profit shifting may induce costs, which are assumed to be non-tax-deductible (Nicolay et al., Citation2017, p. 8).Footnote14 The incurred profit shifting costs may be split into general (or non-channel-specific) costs and channel-specific costs, depending on whether they arise from the use of a particular profit shifting channel or from profit shifting as such. Furthermore, the authors distinguish between costs related to tax regulations (general: tax enforcement, tax audit probabilities relating to overall shifting volume; specifically: anti-avoidance rules targeting specific profit shifting channels). General costs may result from an increased risk of being audited, an increased need for mitigation strategies, as well as potential adjustments of intra-group transactions via one or both channels if profits are below a certain threshold. In addition, by shifting high volumes of profits MNCs may run the risk of damaging their reputation. Moreover, a multinational might also have to bear the costs of complying with the regulations aiming at tackling intra-group profit shifting and of establishing circumvention strategies. The channel-specific costs include negative channel-specific side effects from profit shifting.

The theoretical model presented considers a MNC that consists of two affiliates, where one affiliate resides in a high-tax country and the other in a low-tax country. The true profit can be shifted from the high-tax to the low-tax affiliate through two profit shifting channels via transfer manipulation and

via internal debt. The true pre-tax profit is defined as the taxable profit that would have been reported in the absence of profit shifting.

denotes the combined volume of shifted profits via the channels

and

.

is the optimal amount of shifting out of the high-tax country, when the tax advantage from profit shifting equals marginal profit shifting costs.

represents both the channel-specific and the general costs of profit shifting. Consequently, the total cost function of profit shifting

of profit shifting is derived from the minimum cost combinations of the two input factors (which equal the two shifting channels) for all potential output levels:

where and

denote the costs of shifting unit

via transfer pricing

and unit

via debt

. Whether substituting one profit channel for the other is optimal depends on how these costs per shifted unit are determined. The authors followed the existing literature by assuming that all profit shifting costs are convex in the amount of shifted profits and formalized it as follows,

with , where

. The paper suggests that the costs of profit shifting depend exclusively on the amount shifted via the respective channel and not on the total amount shifted. Furthermore, if one profit shifting channel is becoming more costly, firms will reduce the amount shifted via this channel by substituting one channel with the other.

To tackle this issue, several countries hosting foreign firms have responded unilaterally by introducing specific anti-profit-shifting rules, i.e., rules that restrict the foreign subsidiaries’ ability to shift profits abroad. The question is, however, whether such restrictions are generally beneficial for the imposing countries. A small, but growing, literature analyses the effect of anti-avoidance rules on investment. If anti-avoidance rules reduce the scope for profit shifting, then there should be a negative impact on real investment (see, Buettner et al. (Citation2018) and De Mooij et al. (Citation2021)). The last publication devoted a work related to this issue.

De Mooij and Liu’s (Citation2020) study is related to the literature that investigated the effects of introducing or tightening transfer pricing regulations on key aspects of firm behaviour, including profits shifting and investment. The theoretical framework considers a parent of a multinational firm that supplies its subsidiary with intermediate input good used in the production. De Mooij and Liu (Citation2020) considered that in deviating the transfer price from the AL market price the parent faces an expected cost , e.g., due to a penalty when caught or because of costs associated with a transfer pricing dispute. The expected cost of mispricing per unit of the intermediate input

is assumed to rise quadratically in the price deviation

. The authors stipulate that the parameter

can be influenced by the government through the transfer pricing regulation in the tax code of the respective country. The transfer pricing regulation determines the probability of an adjustment in the transfer price or the penalty in case of detected mispricing. Hence, a higher

reflected stricter transfer pricing regulation rules.

It is worth mentioning that no paper in our review deals with the tax uncertainty relationship. Our motivation to analyse all those papers is simple. The variety of their investigation areas is closely related to profit shifting costs. In any case, it remains true that further studies in the literature deal with profit shifting costs. However, we would expect that our qualitative results in the following section will still be valid. After having investigated what is known about the profit shifting cost, its splits and delimitation, and after having described the respective modelling approaches of the costs functions, we now turn to analyse some findings and discuss the tax uncertainty and its relation with the profit shifting costs.

2.2. Analysis and discussion. It has been theoretically established and empirically confirmed that multinational firms trade off the profit shifting costs against the tax gains generated by the tax rate differential between a high and low tax jurisdiction. It seems to be widely agreed on the fact that transfer mispricing and misreporting activities within the multinational involve resource costs. Profit shifting is not costless because tax authorities have an interest in preventing profit relocation from their countries. It is likewise important to emphasise the consensus in the literature that firm incurred costs are a convex function. The shape of the function is crucial (De Mooij et al., Citation2021, p. 178). Overall two distinct strands or streams of literature emerge:

(1) a stream of literature that assumes that mispricing activities involve resource costs to the firm, and these costs depend only on the difference between the charged transfer price and the AL market price.Footnote15 Papers which follow this approach are: Kant (Citation1988), Haufler and Schjelderup (Citation2000), Lohse and Riedel (Citation2013), Nielsen et al. (Citation2014), and De Mooij and Liu (Citation2020).

(2) Another stream of literature rather assumes that misreporting activities (misdeclaration of taxable income or rather a profit) incur positive costs for the firms, and then that these costs depend on the amount of profit shifted.Footnote16 Papers that follow this approach are Hines and Rice (Citation1994), Huizinga and Laeven (Citation2008), Loretz and Mokkas (Citation2015), Stöwhase (Citation2006), and Nicolay et al. (Citation2017).

One of the main challenges in both streams is the split of the different types of profit shifting costs. For example, although Loretz and Mokkas (Citation2015) considered that the real costs of profit shifting are unknown, they assumed that these costs may be resource costs, such as hiring tax and transfer price experts to allocate accounting profits efficiently, or they may represent costs that the firm pays only if they are caught by the tax authorities (Loretz & Mokkas, Citation2015, p. 5). Nicolay et al. (Citation2017) considered that these costs may be split into general (or non-channel-specific) costs and channel-specific costs, depending on whether they arise from the use of a particular profit shifting channel or from profit shifting as such. Whereas, Lohse and Riedel (Citation2013) considered that the structure of the costs plausibly depends on the countries’ transfer pricing laws (Lohse & Riedel, Citation2013, p. 5). In section 3, we propose a set of profit shifting resource costs that may be borne by the shifting firm by a direct transfer pricing deviation.

By and large, in the first stream, there is a large heterogeneity of modelled costs functions. Lohse and Riedel (Citation2013) set up the cost function as a product of two functions: the price deviation and the scope of countries’ transfer pricing laws. Nielsen et al. (Citation2014) modelled the cost function as an additive form of two functions: the concealment effort cost and the expected fine. De Mooij and Liu (Citation2020) modelled a cost function as a product of the price deviation and an exogenous parameter that can be influenced by the government through the transfer pricing regulation in the tax code of the respective country. We may explain this heterogeneity through the different research issues and the respective objects of investigation. Concerning the second stream, the predominant approach is based on the assumption that shifting profits costs rise in proportion to the ratio of shifted profits to true profits with a factor of proportionality or scaling parameter. This conceptual framework developed by Hines and Rice (Citation1994) and extended by Huizinga and Laeven (Citation2008) is the predominant form in this line of research. Loretz and Mokkas (Citation2015) followed the literature (Hines and Rice (Citation1994); Huizinga and Laeven (Citation2008) by making some simplifications in their model. Stöwhase (Citation2006) used a modified form of the cost function as a ratio with the fraction of the tax base that is misreported without considering the true profits. In contrast, Nicolay et al. (Citation2017) suggested that the total cost of profit shifting is the sum of the cost via the respective channel transfer pricing and internal debt.

In this strands of literature, almost studies propose a scaling parameter of profit shifting costs. For example, De Mooij and Liu (Citation2020) consider that a higher parameter reflected stricter transfer pricing regulation rules, which might have an effect on the cost of capital and investment of multinational firms. Whereas, in a recent study, Klemm and Liu (Citation2019) model a scaling parameter

which measures the extent of misreporting as a quotient

, with high values of

implying lower profit shifting costs. The authors consider that parameter as a proxy for an anti-avoidance rule or stronger administrative capacity. In the same vein, Mardan and Stimmelmayr (Citation2020) modelled a parameter

which is expressed as countries’ thin capitalization rule. In this regard, we observe the following: First, most papers assume that the scaling parameter can be generally related to countries’ tax laws and transfer pricing regulations (see, De Mooij et al. (Citation2021, p. 178); De Mooij and Liu (Citation2020, p. 276); Lohse and Riedel (Citation2013, p. 5); Nielsen et al. (Citation2014, p. 5) and Stöwhase (Citation2006, p. 180) among others). Second, they linked the respective scaling parameter to, e.g., the penalty in case of detected mispricing, the probability of an audit or a single anti-avoidance rule. There is a common assumption that the existence of a single transfer pricing provision or anti-avoidance rules implies higher profit shifting costs. Being based on this approach, those parameters are used to model the respective object of investigation and, therefore, derive related hypotheses and propositions. This modelling approach however must be seen very critically as it considers an intuitive assumption and ignores the interaction with other triggers of profit shifting costs. Furthermore, countries have different regulatory preferences, and these differences are the main reason for the existing mismatches and blind spots (Rathke et al., Citation2020, p. 165). Does a single anti-avoidance rule, e.g., countries’ thin capitalization rule, the only proxy of multinational incurred shifting costs? How about the interaction between other transfer pricing provisions and the respective anti-avoidance rule? Do transfer pricing provisions have equal effects in different countries? Obstacles will arise if countries lack appropriate legislation. Indeed, developing countries frequently lack appropriate legislative and administrative resources, and are generally seen as more vulnerable to income shifting than developed countries (Fuest & Riedel, Citation2010, pp. 2–13). Existing studies indicate that tax rules are implemented and enforced according to established tax characteristics of each country, and empirical findings indicate that similar transfer pricing rules produce varying impacts on different countries (see, Rathke et al. (Citation2020, p. 154) and references therein). Therefore, the interpretation and expression of many scaling parameters carried some reserve. We understand that these questions are not appropriately addressed and gain importance for theory and empiric research, particularly in the context of developing countries.

Finally, no paper in our study has taken the tax uncertaintyFootnote17 into consideration. Despite the broad application of OECD transfer pricing guidelines as a baseline standard, countries maintain unilateral rules to prevent transfer pricing manipulation. Countries typically implement the core of OECD guidelines into their domestic tax systems and include specific provisions according with their regulatory background (Rathke et al., Citation2020, p. 152). Unclear, vague or poorly drafted legislative provisions will lead to tax uncertainty. And it is likely for the uncertainty to increase where tax provisions are unnecessarily difficult to understand, poorly organised within or not integrated into the consolidated tax law and where they fail to give clear effect to the stated policy objective (OECD & IMF, Citation2017, p. 19). Moreover, the choice of an inappropriate anti-avoidance instrument or poor drafting and arbitrary implementation of the relevant provisions could be a source of tax uncertainty. Therefore, tax policy design represents the earliest stage at which uncertainty can be tackled (OECD & IMF, Citation2017, pp. 20–43). The major drivers of tax uncertainty for businesses relate to uncertain tax administration practices, inconsistent approaches of different tax authorities in applying international tax standards, and issues associated with dispute resolution mechanisms (OECD & IMF, Citation2018, p. 5). The OECD & IMF (Citation2017) report highlighted that the sources of tax uncertainty arising from tax administration and the tools for reducing such uncertainty can be broadly split into two categories. The first category concerns the avoidance of disputes through a more transparent relationship between businesses and the tax administration together with mechanisms to provide greater clarity around the application of tax law. The second category provides that, where disputes do arise, effective and timely dispute resolution mechanisms need to be put in place. Both categories have a domestic and international dimension (OECD & IMF, Citation2017, p. 47). In this regard, the unpredictability of the costs of litigation and any ancillary dispute resolution processes is likely to add to tax uncertainty (OECD & IMF, Citation2017, p. 22). The IRS’s transfer pricing case against Veritas Software illustrates the uncertainty that exists in setting transfer prices and how this uncertainty can potentially lead to large benefits for the firm but also creates risk if the tax authority exploits the assumptions to their favour (Veritas Software Corp. v. Commissioner, 133 T.C. No. 14 [10 December 2009]). This case demonstrates the widely varying possible transfer prices and the potential for large tax savings or costs, depending on one’s perspective (Mescall & Klassen, Citation2018, p. 834). Another prominent case is the Kenya vs Unilever Kenya Ltd, October 2005, High Court of Kenya, Case no. 753 of 2003. Kenya has revised its transfer pricing legislation since this decision (Unilever & Kenya, Citation2005). Therefore, we support the idea that the relationship between tax uncertainty and profit shifting costs has to be taken into consideration by modelling the profit shifting costs function.

Further topics in the analysed papers is the assumption of the tax-deductibility of profit shifting costs. Most papers assumed that profit shifting costs are non-deductible. In practice, some of the types of costs may be tax-deductible, while others are not. Furthermore, the fact that the deductibility adds considerable complexity needs to be taken into account, as it is not entirely obvious in which country the costs would be incurred, and there would be an incentive to shift these deductions from the low-tax to the high-tax country (Lohse & Riedel, Citation2013, p. 5). For example, changes in the tax rate may induce firms to evaluate uncertain tax positions and push the amount of tax deductibles harder in order to offset governments’ attempts to increase the effective taxation (Rathke et al., Citation2020, p. 162). It appears important for future research to stress this issue.

Taking all these results into account, we present in the next section a theoretical model considering a representative multinational firm, therein we conceptualize our cost function. Thereby, we expand the literature by suggesting a new profit shifting costs function that includes tax uncertainty.

3. An other modelling approach

In this section, we formulate our modelling approach and show how the link between profit shifting costs and tax uncertainty looks like. First of all, we present a simple model of a representative multinational firm with two affiliates and its underlying assumption. Then, we describe the costs split, the property of our costs function and we express its parameters. Finally, we plot the costs function using ScilabFootnote18 and GeoGebraFootnote19 software and derive our proposition.

3.1. Multinational firm and profit shifting. Consider a representative vertically integrated MNF with the parent and its wholly ownedFootnote20 single affiliate

. The ownership establishes a nexus between the two firms, which allows them to engage in tax arbitrage activities through profit shifting. Following Bernard et al. (Citation2006), we consider an explicitly partial equilibrium approach to the problem of transfer pricing by taking the location of the firm activity as given.Footnote21 Our model differs from previous papers by assuming two countries asymmetric. The first asymmetry originates from the fact that countries’ tax laws and transfer pricing regulations are implemented and enforced differently. Furthermore, both countries’ tax authorities have different administrative capacities. Although, it is assumed that, either due to international convention or otherwise, both countries adopt the same definition of arm’s length (AL) price. The second asymmetry is that country

is the larger of the two markets and has more advanced technology than country

. The parent

produces an intermediate homogenous input good

in its home country

at a marginal cost

and sells it free-on-board to its overseas affiliate

, which operates in country

. Sales of

to the affiliate are internally priced, with

denoting the transfer price. Alternatively, the parent can buy the intermediate input good at the local market at price

and ship it to the affiliateFootnote22 in country

. The affiliate

uses the imported intermediate input good

to produce a final good

. It is reasonable to assume that one unit of primary intermediate good

is needed to make one unit of final good

.Footnote23 Output and factor markets are perfectly competitive. The final good is sold in country

.

Our analysis assumes that international taxation follows a pure source principle. Both countries levy taxes on the profit of the firms operating within their jurisdiction (this is the only policy instrument available to the governments) and no group taxation applies. Let and

denote the corporate income tax rate (CIT) set by the parent and affiliate governments respectively. We follow Mardan and Stimmelmayr (Citation2020) by assuming governments in each country maximize national welfare by non-cooperatively setting their tax rates. Under the ruling international standard of separate accounting, the profits are considered separately of each entity a the MNF. This is consistent with both countries applying the so-called separable accounting method of taxing MNF’s profits. We note that low tax rates attract foreign business and foreign profits in two ways. The first way is that firms have incentives to transfer profits from high-tax locations where much of their productive physical activity takes place in low-tax locations where, for lack of economic opportunities, it does not. The second one is that operations that would be unprofitable at normal tax rates might become profitable at very low rates (Hines & Rice, Citation1994, p. 158). Indeed, if the corporate tax rate

charged by the country where the affiliate is located is lower than the corporate tax rate

charged by the country of the parent and the repatriation of income is exempt in the parent country, it will be attractive to shift income from the parent to the affiliate (De Mooij & Liu, Citation2020, p. 276). MNFs may be able to charge artificially low prices for exports sold from high-tax to low-tax countries or artificially high prices for inputs coming from low-tax countries, to reduce their global tax liability (Beer et al., Citation2018, p. 5). This is one popular tax-minimizing practice to violate or misuse the arm’s length principle (the notion that intragroup prices should be valued at the prices charged to unrelated parties), by overpricing imports from affiliated companies in a low-tax jurisdiction (that is, inflating costs in high-tax countries) or underpricing exports to these affiliates (that is, understating incomes in high-tax countries; De Mooij et al., Citation2021, p. 34). Furthermore, in the absence of clear regulatory provisions (or where the benefits of non-compliance outweigh the potential costs), associated parties may have an incentive to manipulate transfer prices (Cooper et al., Citation2016, pp. 5–6). Profit shifting in our model takes the following simple form: Without loss of generality, we assume that when the parent supplies

to its affiliate

, it charges a transfer price

that deviates from the AL market price

. The true (AL) market price

of this intermediate homogenous input good

must equal a one-good setting, but this price cannot be directly observed by tax authorities. Hence, the transfer price

becomes an additional choice variable for the multinational firm, which may either over invoice (

) or under invoice (

) in order to reduce aggregate tax payments (Haufler & Schjelderup, Citation2000, p. 312).

3.2. Profit shifting costs function. We assume that profit shifting activities in our model involve resource costs for the multinational firm denoted by . We take the following simplification that these costs will be independent of the capital allocation between tax jurisdictions. This assumption will serve to isolate the effects of transfer mispricing on the profit shifting costs. We follow Beer et al. (Citation2018) considering that costs of profit shifting are likely to differ across MNCs of different operating scales or industry structures, and across countries with varying enforcement and administrative capacity (Beer et al., Citation2018, p. 10). Hence, this assumption in our model can be interpreted as an explicit consequence of countries’ asymmetry mentioned above. Finally, we follow the literature Kant (Citation1988) and Nielsen et al. (Citation2014) by assuming that firms’ default probability to be audited is positively correlated to mispricing activities.

Profit shifting activities in our model involve resource costs for the multinational firm. We split the MNF incurred costs as follows:

(1) costs associated with firms’ increased need for mitigation and establishing circumvention strategies because by shifting high volumes of profits, MNF may run the risk of damaging its reputation (Nicolay et al., Citation2017, pp. 8-9).

(2) costs related to countries’ tax and transfer pricing laws and regulations as well as anti-avoidance rules which target specific profit shifting channels. Because firms need to justify the distorted transfer prices to the tax authorities (Huizinga & Laeven, Citation2008, p. 1166) and may set up additional facilities to make it seem plausible (Hines & Rice, Citation1994, p. 159). Following Huizinga and Laeven (Citation2008) even if firms comply with transfer pricing regulations, they may face considerable costs in dealing with, for instance, documentation requirements (Huizinga & Laeven, Citation2008, p. 1166).Footnote24

(3) costs may result from a high probability of detection (see, e.g., Kant (Citation1988), Nielsen et al. (Citation2014)). The stricter the laws, the higher the probability that mispricing will be challenged which increases the concealment costs. If the tax authorities detect that the intermediate good is over invoiced to shift profit (see, (Lohse & Riedel, Citation2013, p. 5), (Nielsen et al., Citation2014, p. 4)), a penalty and potential adjustments of intra-group transactions (Nicolay et al., Citation2017, p. 8) will be imposed.

(4) the firm could face costs associated with a transfer pricing dispute (De Mooij & Liu, Citation2020, p. 276). Disputes with tax authorities about how the transfer price is calculated could emerge and/or for wrong, missing or incomplete transfer pricing documentation. In this case, legal costs may incur (Hines & Rice, Citation1994, p. 159), because the challenged mispricing by the tax authorities have a lower probability of being sustained by courts or more resources may be required to defend the legal dispute successfully (Lohse & Riedel, Citation2013, p. 5).

As described, our costs’ split encompasses most of the assignment that has been identified in the literature (see, section 2 review of the literature) in a clearly structured manner. Without consequence for our qualitative results, let the total profit shifting costs rise quadratically in the weighted deviation of the transfer price from the AL market price. The cost function is defined as,

We can show that , for

, and

, when

. Furthermore, we have

, for every

. Therefore, the function

is convex in the transfer price

, or equivalently in the deviation

. For simplification reasons, the profit shifting costs are assumed to be non-tax-deductible. We follow the literature in relating

to countries’ tax and transfer pricing laws and regulations (see, De Mooij and Liu (Citation2020, p. 276); De Mooij et al. (Citation2021, p. 178); Lohse and Riedel (Citation2013, p. 5); Nielsen et al. (Citation2014, p. 5); Stöwhase (Citation2006, p. 180) among others). Lohse and Riedel (Citation2013) demonstrate in particular that the transfer price distortions are reduced if the scope of a country’s transfer pricing laws rise (Lohse & Riedel, Citation2013, p. 6). In the absence of clear regulatory provisions (or where the benefits of non-compliance outweigh the potential costs), associated parties (the parent

and its affiliate

) may have an incentive to manipulate transfer prices (Cooper et al., Citation2016, pp. 5–6). The profit shifting costs

increase with the given exogenously scaling parameter

. The cost scale is substantially determined by the extent of the implementation and tightening of transfer pricing regulation (Rathke et al., Citation2020, p. 153) in countries

and

.Footnote25 We follow Marques and Pinho (Citation2016) by assuming that the existence of statutory transfer pricing regulations, penalty rules, and law enforcement mechanisms implies a higher strictness level (Rathke et al., Citation2020, p. 153). Hence, countries’ extensive transfer pricing laws and regulations as well as anti-avoidance rules are reflected in a higher

. High values of

imply higher profit shifting costs. Instead, if

is low, the costs of mispricing are only modest. An intuitive interpretation of the parameter

may be the government’s capability through tax legislation and regulations to shape the curbing of profit shifting.

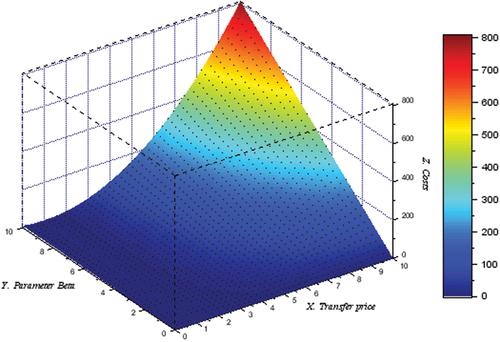

We plot the 3D surface of the costs function with the Scilab Software to investigate the relationship between two predictors on the and

axes and a continuous surface that represents the response values on the

axis.

is a real matrix explicitly defining the heights of nodes, of sizes

. At each node of the data grid, a

coordinate is given using the

matrix. Each point has a value equal to the

coordinate of the point which is proportional to the height. All grid cells are quadrangular. The colours parameter is linked to the

matrix, one colour per patch. The peaks and valleys correspond to combinations of

and

that produce local maxima or minima. Minitab uses interpolation to create the surface area between the data points. Without loss of generality and following our model in section 3, the true (AL) market price

of the intermediate homogenous input good

must equal a one-good setting. The cost functions is given by,

, where

and

.

.

The 3D surface in Figure shows the relationship between the transfer price and

settings to determine the calculated profit shifting costs

.

The peak of the plot corresponds to the highest distortion of the transfer price, combined with the highest values of . An interpretation of this result is, when the multinational firm engages in profit shifting via transfer mispricing

, the profit shifting costs

increase with countries’ extensive tax and transfer pricing laws and regulations

. This could be justified by the fact that the structure of the costs

plausibly depends on the countries’ transfer pricing laws (Lohse & Riedel, Citation2013, p. 5). Furthermore, countries differ substantially when it comes to the transfer pricing regulation (Nielsen et al., Citation2014, p. 5). Indeed, countries typically implement the core of OECD guidelines into their domestic tax systems and include specific provisions according with their regulatory background (Rathke et al., Citation2020, p. 152). In this regard, for example, some countries do not have explicit rules in domestic law for the transfer pricing regulation but rely on the OECD double tax convention and the arm’s length principle. Other countries have incorporated the arm’s length principle explicitly in domestic law. These countries can also require that the firm documents the transfer price during a public audit. Finally, some countries have a transfer pricing regulation that requires firms that trade with related companies to document how the transfer price is calculated. Such documentation must either be submitted with the firm’s annual return or submitted upon request. In countries with high-quality transfer pricing regulation, there may be penalties for wrong, missing or incomplete documentation of how the transfer price has been calculated. This fine would come in addition to fines related to mispricing or misdeclaration of taxable income (See, Lohse et al. (Citation2012)).

Following our modelling approach, the parameter is related to countries’ tax legislation and transfer pricing regulation of the involving countries. With respect to the above results and the discussion in section 2, countries’ tax legislation and transfer pricing regulation may figure as a source of uncertainty. Whitford (Citation2010) considers that regulatory uncertainty may come when the state, through taxation policy, tries to shape how firms distribute their profits (Whitford, Citation2010, p. 273). The choice of an inappropriate anti-avoidance instrument, unclear, vague or poorly drafted legislative provisions and arbitrary implementation of the relevant provisions will lead to tax uncertainty (OECD & IMF, Citation2017, pp. 19–43). Firms face massive risk and uncertainty due to variability in policy actions that result from the weak capability for implementation of regulations (Hallward-Driemeier et al., Citation2016, p. 217). Therefore, we assume a functional relationship between profit shifting costs and tax uncertainty. Thus,

is an exogenous parameter that expresses the tax uncertainty. In our model, the parameter

is an intensiveness parameter. We define that intensive uncertainty is reflected in a large

. Consider

.

The cost function reads as follows

We can infer that intensive uncertainty with a large will lead to a decrease in profit shifting costs

. The parameter

can be influenced by the government, e.g., by avoiding discretionary application and uncertainty for taxpayers that lead to a trade off (De Mooij et al., Citation2021, pp. 254–345). Therefore, tax policy design represents the earliest stage at which uncertainty can be tackled (OECD & IMF, Citation2017, pp. 20–43). The major drivers of tax uncertainty for businesses relate to uncertain tax administration practices, inconsistent approaches of different tax authorities in applying international tax standards, and issues associated with dispute resolution mechanisms (OECD & IMF, Citation2018, p. 5).

Indeed, if the instruments and mechanisms adopted within a tax regulation do not clarify the application of the tax laws and legislation in a rigorous manner, the consequence is that uncertainty emerges for businesses and the tax administration. Moreover, firms face significant uncertainty about how governments view intragroup transactions (Whitford, Citation2010, p. 271). Thus, a large depicts lower or modest tax laws and regulations quality, inconsistency and tax loopholes, missing of anti-avoidance rules and related regulations to prevent profit shifting in the domestic tax code, time spend on disputes and costly litigation between businesses and tax administration, insufficient administrative capacities and outdated information communication technology within the tax administration. On the other hand, a low

reflects high quality, simple and clear tax laws and regulations based on objective criteria, so that less room is left for inconsistency and tax loopholes. It also reflects effective measures and instruments to prevent profit shifting, to minimize dispute between businesses and tax administration and to mitigate adverse effects, as well as strong administrative capacities and a modern IT infrastructure within the tax administration. A significant decrease of tax uncertainty and regulatory risk that governments might seek to mitigate (Whitford, Citation2010, p. 270) will provide governments with significant instruments at their disposal to prevent profit shifting and secure the tax base in their countries.

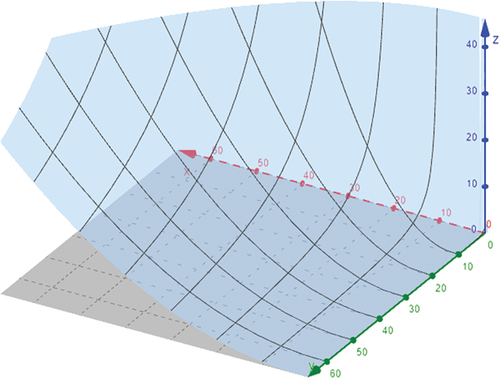

Taking all these results into account, we now plot the 3D costs functions using GeoGebra Software. The transfer price

and tax uncertainty

on the

and

axes and the response values on the

axis. Thus, the cost function is given by:

where and

.

.

Figure shows clearly that a low value of tax uncertainty makes the profit shifting curve steeper.

Consequently, when the multinational engages in profit shifting via transfer mispricing, it will face implicitly extensive tax and transfer pricing regulations (higher ). Therefore, firms incurred costs will increase. An increase in the involved costs makes profit shifting not easy and expensive for the multinational firm. The effect of a low value of tax uncertainty on profit shifting costs is more pronounced. Because tax authorities of involving countries have the capability and the right instruments at their disposal to prevent profit shifting and tackle intra-group profit shifting to secure the tax base in its border. Whereas, higher values of tax uncertainty

will implicitly decrease

and consequently lead to decrease profit shifting costs

. An explanation might be that an increase in tax uncertainty which reflects a weak tax code, lower tax-law quality, missing of anti-tax avoidance rules in the national tax code to curb intra-group profit shifting will encourage the multinational firm rather shift easily profits than to conceal the transfer mispricing from tax authorities or to incur expenses for mitigation and circumvention strategies. Furthermore, due to insufficient administrative capacities, the probability of mispricing detection will be lower. We rule out this result with the following proposition:

Proposition. When the multinational firm engages in profit shifting via transfer mispricing by incurring profit shifting costs and if the tax uncertainty decreases, this will lead to higher profit shifting costs, whereas these costs are low if the tax uncertainty increases.

Overall, the literature confirms our results. Nielsen et al. (Citation2014) demonstrate that improving the tax-law quality, so that less room is left for inconsistency and tax loopholes, will unambiguously reduce profit shifting. This is coherent with our argumentation that, if the government is somewhat effective through tax legislation and transfer pricing regulation to shape the curbing of profit shifting, e.g., closing tax loopholes, improving tax-law quality and implementing a transfer pricing regulation with a set of minimum standards, that will decrease and therefore it will lead at least to a moderate increase of profit shifting costs

which unambiguously makes profit shifting much more difficult for MNCs. According to Stöwhase (Citation2006), the low tax country

may find it optimal to implement at least some regulations that make it more difficult for the multinational firms to shift profits into the country (Stöwhase, Citation2006, p. 16). After having described the costs split, the property of the costs function and expressing its parameters, we now come to discuss our derived proposition in conjunction with the literature.

3.3. Discussion and conjunction with the literature. It is perhaps of somewhat greater interest to discuss our proposition jointly with the results of some papers of our literature review. Loretz and Mokkas (Citation2015) empirically tested whether profit shifting costs have an effect on the pre-tax and post-tax profitability of affiliates in the low tax country. The authors found that if profit shifting costs are low and if a country increases its tax rates then affiliates will decrease their capital stock to satisfy the marginal condition, which will tend to raise the pre-tax profitability. In addition, it will transfer profits to the lower-taxed affiliates. On the other hand, the reported post-tax profitability should definitely be reduced in reaction to an increase in the tax rate. If profit shifting costs are high that may not decrease the pre-tax profitability of affiliates (Loretz & Mokkas, Citation2015, p. 27).

For our proposition, we can infer that if the country increases its tax rates

and when the tax uncertainty

in country

is large, profit shifting costs

will decrease, which may lead to raising the reported pre-tax profitability of the affiliate

in the low tax country

. But it should reduce its reported post-tax profitability in reaction to the increase in the tax rate in country

. Our proposition expands the results of Loretz and Mokkas (Citation2015) by providing a link to tax uncertainty to explain the extent of profit shifting costs. A question of great relevance is if the post-tax profitability of affiliate

is reduced in the low tax country

, what happens to tax revenues of both countries? Stöwhase (Citation2006) analyses how a change in the costs of profit shifting affects equilibrium tax rates and tax revenues between low and high tax countries. The author found that higher profit shifting costs lead to a decrease in tax revenue of the low tax country. Maximal revenue is given for medium costs of profit shifting. Whereas, higher profit shifting costs will increase both tax payments of the multinational and tax revenue of the high tax country (Stöwhase, Citation2006, pp. 12–13). In conjunction with our proposition, when tax uncertainty

is low, the profit shifting costs

will increase, consequently tax revenue of the low tax country

will decrease whereas that of the high tax country

will increase. Low tax country