?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The industrialisation of the Ghanaian economy has seen less light despite the high levels of trade and being one of the highest receivers of foreign direct investment (FDI) in West Africa. This low performance in the industrial sector may be due to the frequent shocks the country suffers in her trade engagements and FDI inflows. Therefore, this study sought to examine the asymmetric effect of trade openness and FDI on industrialisation in Ghana. In achieving this, contemporary time series approaches, involving Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) and Non-Linear Autoregressive Distributed Lag (NARDL) approaches to cointegration, were used to analyse the time series data from 1983 to 2019. The results revealed that in both the long- and short-run, the positive shocks in trade openness have no effect on industrialisation, and the negative shocks in trade openness cause industrialisation to fall. Regarding FDI, the positive shocks in FDI exert positive effect on industrialisation in both the long- and short-run, but the negative shocks exert no effect on industrialisation in the long-run, however, a positive effect on industrialisation in the short-run. Findings from the study imply that trade openness in both the long- and short-run is detrimental to industrial progress in Ghana. Also, FDI is much needed for Ghana to industrialise her country. It is recommended that government policies should be channelled to reducing external shocks faced by traders, mostly exporters, while focusing on creating an enabling environment to attract the needed FDI to the industrial sector, and increasing infrastructural base of the country.

1. Introduction

Over the years, most developing countries have relied mainly on their natural resources in order to propel growth. With limited value addition, they depend heavily on the production and export of primary commodities and far less forward and backward relations with other sectors of the economy (United Nation Conference on Trade and Development [United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Citation2019). Consequently, they become susceptible to external shocks which have diverse implications on the growth of their economies. Due to this the region has been embedded with huge unemployment rate, low standard of living and poverty (Opoku & Yan, Citation2019).

It is in this setting that United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (Citation2019) asserted that economic and export diversification, value addition and industrialisation are the sure ways to contribute to strengthening the pliability of developing countries enabling them to extract revenue from multiple sources and create job opportunities. A study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (Citation2017) also postulated that without industrialisation, the economic development of Africa cannot be possible; and further asserted that the total merging of the region with the advanced countries can only be triggered by industrialisation. More so, the African Union (AU) proclaims industrialisation as the core tool for fostering and attaining inclusive economic transformation (Opoku & Yan, Citation2019). Hence, Effiong et al. (Citation2019) opined that industrialisation is not an option but a necessity to attain sustainable development which has long lasting benefits on economic growth.

In the light of the enormous benefits of industrialisation, it is imperative that its nature and determinants are well understood by each country (most especially a developing country like Ghana). Some researchers propose trade openness and FDI as means to achieve higher levels of industrial growth and economic development (Majumder & Rahman, Citation2020; Miah & Majumder, Citation2020; Tahir et al., Citation2016; Zhang, Citation2014). According to Khobai and Moyo (Citation2020), trade openness is a policy option that boosts productivity in the domestic economy by providing access to cheaper and improved technology, enhanced quality of inputs and managerial skills from overseas. Also, Adamu and Dogan (Citation2017) opined that trade openness brings competition which promote efficiency in the domestic economy which benefit local consumers. Exporting firms in the domestic country may be able to take advantage of economies of scale brought about by the larger market (Adofu & Okwanya, Citation2017).

In the same vein, Gui-Diby and Renard (Citation2015), Majumder (Citation2019), Majumder et al. (Citation2022), and Opoku et al. (Citation2019) noted that FDI inflows also have the potential of bringing with it financial as well as knowledge assets needed by developing countries to improve their productivity. Bodman and Le (Citation2013) asserted that FDI is one of the significant conduits of technology transfer and human capital development across borders needed for a country to industrialise.

Therefore, as Ghana seeks to reduce her rate of unemployment, improve living standards, alleviate poverty, and achieve higher levels of economic growth, there is the need for her to greatly improve her industrial sector. Corollary, she has engaged in greater level of trade openness (Abeka, Citation2018) which sought to encourage both export and import of goods and services. Again, in line with suggestions of various trade theories, she has lowered tariffs and removed some barriers to trade. Furthermore, a number of trade agreements have been formed to ease the flow of goods and services between her and other countries. Due to this, trade in goods and services has escalated over the few decades.

Moreover, Ghana’s FDI inflow has also increased substantially over the past decade (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Citation2019). She is currently among the highest receivers of FDI in West Africa (World Bank, Citation2017). The country has been pursuing efforts to simplify the complex and lengthy procedures of doing business while also offering tax incentives in order to attract more FDI inflow. However, despite all these efforts in Ghana’s trade and her FDI, her industrial sector performance continues to remain low (Fenny, Citation2017). Growth in the sector for the recent past years has been 15.7%, 10.7% and 6.4% depicting a downward trend (World Bank, Citation2020).

Unequivocally, this low performance in the industrial sector may be due to the shocks in trade and FDI inflows. This is because Di Pace et al. (Citation2020) expounded that developing countries may not benefit fully from their trade engagements and FDI inflows as they are very vulnerable to external shocks. Also, Davidson et al. (Citation2010) argued that data of macroeconomic variables such as trade openness and FDI are generally non-stationary, that is a part at least of their movement each quarter is random. Accordingly, this feature makes industrialisation long-term future considerably uncertain. Hence, it has become imperative that the effect of trade openness and FDI on industrialisation be empirically assessed in the Ghanaian context taking into consideration the shocks in trade openness and FDI.

The effect of trade openness and FDI on industrialisation has been the subject of many discussions and studies. This is because empirical works conducted on the effect of trade openness and FDI on industrialisation depict inconclusive results. While some studies such as Adamu and Dogan (Citation2017), Adofu and Okwanya (Citation2017), and Umoh and Effiong (Citation2013) found trade openness to be beneficial, others such as Umer and Alam (Citation2013) found trade openness to be detrimental to industrialisation. In the case of FDI, Effiong et al. (Citation2019), Nkoa (Citation2016), and Zhang (Citation2014) found significant positive effect of FDI on industrialisation, whereas, Samantha and Liu (Citation2018) and Gui-Diby and Renard (Citation2015) found no effect of FDI on industrialisation.

These conflicting findings could be as a result that these empirical works have not examined the effect of trade openness and FDI on industrialisation taken into account the shocks in the predictor variables (trade openness and FDI). Therefore, it is in line with this that this study proposed a method (Non-Linear Autoregressive Distributed Lag-NARDL) to analyse the effect of the shocks in trade openness and FDI on industrialisation in the short- and long-runs.

To add, most of the empirical studies on the effect of trade openness and FDI on industrialisation are mainly cross-country studies (Adegboye et al., Citation2016; Khobai & Moyo, Citation2020; Njangang et al., Citation2018; Tahir et al., Citation2016) with the implicit assumption that developing countries share many common characteristics: low per-capita incomes and high illiteracy rate, etc. Whereas this may be true to some extent, these countries differ largely in their exposure to economic problems, stabilisation policy experiences and most importantly in their reactions to external shocks. And so, the findings and recommendations of these studies cannot be directly applied to country specific (say Ghana) since these findings may not accurately and adequately reflect country specific experience.

Studies that have ventured to highlight the short-run and long-run effect of trade openness and FDI on industrialisation in country specifics are elusive. More specifically, empirical studies in this area in Ghana to serve as a guide to policymakers to the best of our knowledge are few (Adenutsi, Citation2007; Iddrisu et al., Citation2015). Nevertheless, these studies have explored the relationship among the variables using only Johansen and Katarina (Citation1990). It must be noted that trade openness and FDI are very crucial which is frequently hypothesised to boost industrialisation across many avenues, such as: greater access to a variety of production inputs, wider markets accessibility, technological innovations, human capital development, assess to foreign capital and improved competitiveness that raises the efficiency of domestic production through increased specialisation. It, therefore, stands to reason that a better understanding of the effect of the shocks in trade openness and FDI on industrialisation in the short- and long-runs through the NARDL approach is important for policy and strategy formulation to open trade and attract the needed FDI to propel the industrialisation of the economy.

Since industrialisation is the engine to attain sustainable development with lasting benefits on economic growth of any nation, this study will contribute to the development of policies and strategies that seek to promote industrialisation. Again, it will contribute to existing literature on the relationships among trade openness, FDI and industrialisation in the context of the Ghanaian economy. More so, the study will serve as a helpful instrument for policy makers, students, academicians and individuals who want to learn more about the relationships among trade openness, FDI and industrialisation. The rest of sections are arranged starting with literature review, methodology, results and discussion, and then conclusion.

2. Literature review

2.1. Trade openness and industrialisation

Some studies considered the effect of trade openness on industrialisation. Among them are: Khobai and Moyo (Citation2020) who studied the effect of trade openness on industrial performance in eight Southern Africa Developing Council (SADC) countries. The data from 1990 to 2017 was analysed using Pooled Mean Group estimator. Industrial performance was measured using industrial output as a share of GDP whilst trade openness was proxied as the sum of export and import as a ratio of GDP. The result showed that trade openness has a significant positive long-run and short-run effect on industrial output. This is in line with the study by Svilokos et al. (Citation2019) conducted in Central and Eastern Europe.

Tahir et al. (Citation2016) also ended up with similar results when they investigated the impact of trade openness on industrial sector development: evidence from South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). Panel data econometric techniques were used to analyse the data for the period 1980–2013. The study used industrial value added as a percentage of GDP as the measure of industrial sector development and exports plus imports as a percentage of GDP as the measure for trade openness and found that trade openness positively and significantly influences the industrial sector of the sampled countries.

Also, using the ARDL bounds testing methodology over a time series data from 1970 to 2008, Umoh and Effiong (Citation2013) arrived at the same findings when they attempted to investigate the relationship between trade openness and manufacturing sector performance in Nigeria. Trade openness was measured as the ratio of exports plus imports to GDP and manufacturing production index was used for manufacturing sector performance. The results suggested that trade openness has a significant positive impact on manufacturing productivity in Nigeria both in the short- and long-runs.

Similarly, Adamu and Dogan (Citation2017) also used the ARDL approach to co-integration and their findings were no different from Umoh and Effiong (Citation2013) when they considered a paper on trade openness and industrial growth in Nigeria. Quarterly data for the period from 1986 to 2008 were used. The sum of import and export as a share of GDP was used as the proxy for trade openness whilst industrial production index was used as the proxy for industrial growth. Trade openness was found to have significant positive effect on industrial growth in both the long- and short-runs.

However, despite the positive effects found by the above studies, Umer and Alam (Citation2013) assessed the effect of trade openness on industrial sector performance in Nigeria and found that trade openness has insignificant short-run and negative long-run relationship with industrial sector growth. The study employed Johansen co-integration technique to estimate the short-run and the long-run relationship using annual time series data for the period 1960–2011. Trade openness was measured as trade to GDP ratio and industrial sector growth was also measured as industrial sector value-added as a percentage of GDP. Moreover, similar study by Ogu et al. (Citation2016) revealed that trade liberalisation hurts manufacturing output in the short-run but positively affect manufacturing output in the long-run. Additionally, Emediegwu (Citation2021) and Nnadozie et al. (Citation2021) found an unfavourable effect of trade on industrialisation in Nigeria both in the short and long-runs.

In the case of Ghana, Adenutsi (Citation2007) also employed Johansen co-integration technique in estimating quarterly data for the period from 1983(1)—2006(4) when examining the impacts of trade openness and FDI on industrial performance in Ghana and found that trade openness has significant negative effect on industrial performance in both the short and long-runs. Trade openness was measured as export plus imports per GDP and industrial performance was measured as share of the industrial sector to GDP.

Hence, the following research hypotheses are found;

: There is significant long-run effect of the positive and negative shocks in trade openness on industrialisation in Ghana.

: There is significant short-run effect of the positive and negative shocks in trade openness on industrialisation in Ghana.

2.2. Foreign direct investment and industrialisation

Above and beyond trade openness, some studies also examined explicitly the relationships between FDI and industrialisation. Such studies include Adegboye et al. (Citation2016) who investigated the impact of FDI on industrial performance in Africa. The Pooled OLS and the Fixed Effect Least-Square dummy variable model were used over 43 African countries from 1996 to 2015. Measuring FDI as the share of FDI inflow to GDP and industrial performance as industrial value added as a percentage of GDP, the study found that FDI has statistically significant positive effect on industrial performance.

Effiong et al. (Citation2019) also achieved similar outcome when they examined the nexus between foreign direct investment and industrial sector performance in Nigeria. Johansen estimation technique was adopted to analyse the time series data from 1981 to 2017. The study used portfolio investment to represent FDI and the ratio of industrial output to GDP to capture industrial sector performance. The findings revealed that FDI has both long-run and short-run positive effect on Nigerian industrial sector.

Iddrisu et al. (Citation2015) results differed significantly from Adenutsi (Citation2007) even though both studies considered the country Ghana and employed the same estimation technique. Iddrisu et al. explored the influence of FDI on the productivity of the industrial sector in Ghana using the Johansen co-integration estimation technique over a time series data covering the period 1980–2013. FDI was measured as the net inflows expressed as a share of GDP and the industrial sector productivity was measured as the value added to the industrial sector. The study revealed that FDI is insignificant in the short-run but has significant long-run positive effects on the performance of the industrial sector in Ghana.

Moreover, Njangang et al. (Citation2018) also investigated the relationship between Chinese FDI and industrialisation. The study used the System Generalised Method of Moments (GMM) to analyse a panel data of 41 African countries from 2003–2015. Industrial value added as a share to GDP was used to measure industrialisation and the Chinese FDI stock in Africa was used to measure FDI. The results revealed that Chinese FDI does not significantly influence the industrialisation process in African countries. This outcome is confirmed by Emediegwu (Citation2021) and Nnadozie et al. (Citation2021) who revealed insignificant effect of FDI on industrialisation both in the short- and long-runs when the cointegration approach was employed.

Similarly, Samantha and Liu (Citation2018) explored the relationship between inward FDI and industrial sector performance of Sri Lanka. A time series data covering the period 1980 to 2016 was used. ARDL estimation technique was used to identify the long-run relationship and short-run dynamics of the selected variables. FDI was measured as percentage of inward FDI to GDP and industrial sector performance was measured as industrial value added based on the price level of 2010. The study found that in both the long-run and short-run there is no significant relationship between FDI and industrial sector growth of Sri Lanka.

Accordingly, the study is guided by the following research hypotheses;

: There is significant long-run effect of the positive and negative shocks in FDI on industrialisation in Ghana.

: There is significant short-run effect of the positive and negative shocks in FDI on industrialisation in Ghana.

2.3. Gaps in literature

Based on the preceding literature review, it is evident that there is conflict among existing studies which have considered the relationship among trade openness, FDI and industrialisation. While some studies offer support for trade openness as a mechanism for industrialising a domestic country (Adamu & Dogan, Citation2017; Adofu & Okwanya, Citation2017; Khobai & Moyo, Citation2020; Tahir et al., Citation2016) other studies hold that trade openness is deleterious on industrialisation (Adenutsi, Citation2007; Emediegwu, Citation2021; Nnadozie et al., Citation2021; Umer & Alam, Citation2013). Similarly, FDI’s relation with industrialisation is no exception. Studies such as Adegboye et al. (Citation2016), Effiong et al. (Citation2019), and Zhang (Citation2014) hold evidence to suggest that FDI has had a positive impact on industrialisation in the recent decades, meanwhile, other studies such as Emediegwu (Citation2021), Gui-Diby and Renard (Citation2015), Nnadozie et al. (Citation2021), Njangang et al. (Citation2018), and Samantha and Liu (Citation2018) also demonstrate an opposite view of FDI on industrialisation.

These conflicting results demonstrated above, perhaps, could be as a result that these empirical works have not examined the effect of trade openness and FDI on industrialisation taking into account the shocks in the predictor variables. In Ghana, the few studies that exist in the area (Adenutsi, Citation2007; Iddrisu et al., Citation2015) have used only the Johansen co-integration approach. This creates a gap for recent studies to employ robust methods to analyse the relationship among the variables. In that regard, this study employed the Non-Linear Autoregressive Distributed Lag (NARDL) approach developed by Shin et al. (Citation2014) and the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) approach advocated by Pesaran and Shin (Citation1998) and Pesaran et al. (Citation2001).

This study contributes to the existing literature by employing estimation techniques that establish the effect of trade openness and FDI on industrialisation in the context of Ghana. These methods are employed mainly because the asymmetric effect (thus the positive and negative shocks) of trade openness and FDI on industrialisation in the short- and long-runs can be ascertained. Again, these methods are efficient in handling small data sizes and are applicable when the variables are either wholly I(0) or I(1) or even being mutually co-integrated (Pesaran & Shin, Citation1998; Pesaran et al., Citation2001). Accordingly, the analysis will provide valuable empirical evidence for policymakers to evaluate the suitability of Ghana’s existing trade, investment, and industry policies. Additionally, the study will serve to update the existing literature and provide a platform for future research into industrial productivity in open economies.

3. Methodology

Explanatory research design was employed by this study. This is because, this design helps to establish the cause-and-effect relationship between variable, which is the case of the objectives of this study, where the first and second objects seek to establish the effect of trade openness and FDI on industrialisation respectively, and the third objective seeks to assess the direction of causality among trade openness, FDI and industrialisation. The study, therefore, employed the quantitative approach. The study explained the relationships among trade openness, FDI and industrialisation in Ghana.

Ghana is taken into account as the study’s context because the country seeks to lower her unemployment rate, raise living standards, reduce poverty, and achieve higher rates of economic growth. To do this, she must significantly enhance her industrial sector. Additionally, she has increased trade openness in an effort to promote both export and import of goods and services (Abeka, Citation2018). Additionally, over the past ten years, Ghana’s FDI inflow has also significantly expanded (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Citation2019). She is currently one of West Africa’s top recipients of FDI (World Bank, Citation2017). However, despite all of this trade and FDI initiatives, Ghana’s industrial sector performance is still subpar (Fenny, Citation2017). the sector has seen growth in recent years

The study employed a secondary data. An annual time series data, spanning from 1983 to 2019, was used. This period was specifically chosen to ensure consistent data availability for the selected variables and also to mitigate the adverse impact of the COVID-19 pandemic to enhance effective comparison throughout the sample period. The series for all variables used, except for FDI, was drawn from World Development Indicators database (World Bank, Citation2020). Data for FDI was drawn from UNCTAD statistics. The motivation for the period selected was because of data availability for the specified variables and the control variable.

4. Model specification

To investigate the asymmetric effect of trade openness and FDI on industrialisation in Ghana, the study followed Nkoa (Citation2016) and Jie and Shamshedin (Citation2019) and framed symmetric econometric models for the study and subsequently modified to obtain the asymmetric models for the study. The long-run symmetric (linear) model estimated for this study was specified as:

where is industrialisation,

is trade openness,

is foreign direct investment,

is gross fixed capital formation (domestic capital),

is the intercept, the coefficients

are the parameters of the respective variables,

is the time, and

is the error term.

Also, the long-run asymmetric (non-linear) model estimated for this study was specified as:

where INDUS is industrialisation, is positive trade openness,

is negative trade openness,

is positive foreign direct investment,

is negative foreign direct investment,

is positive gross fixed capital formation (positive domestic capital),

is negative gross fixed capital formation (negative domestic capital),

is the intercept, the coefficients

are the parameters of the respective variables, t is the time, and μ is the error term.

From Equationequation (1)(1)

(1) , the linear short-run model estimated for this study was established as:

where is the difference operator,

is the intercept,

is the short-run coefficient of industrialisation,

are the short-run dynamic coefficients of the respective variables, with

showing the speed of adjustment,

is the error correction term lagged one period, t denotes time and finally ɛ is the stochastic error term.

The short-run asymmetric model following Equationequation (2)(2)

(2) was specified as:

where is the difference operator,

is the intercept,

is the short-run coefficient of industrialisation,

are the asymmetric short-run dynamic coefficients of the respective variables, with

showing the speed of adjustment,

is the error correction term lagged one period, t denotes time and finally ɛ is the stochastic error term.

5. Summary of variables

Table provides a summary of the variables employed in this study, how they were measured, their source, their sign expectations and the empirical justification for their measurements.

Table 1. Description of variables and source of data

6. Data processing and analysis

The data was analysed using Econometric Statistical Software Eviews 10 package. The study employed both descriptive and quantitative analysis. Charts such as graphs and tables were employed to aid in the descriptive analysis. Unit roots tests were carried out on all variables to ascertain their order of integration. Further, the study adopted ARDL and NARDL econometric methodologies to co-integration introduced and popularised by Pesaran et al. (Citation2001) and Shin et al. (Citation2014) to obtain both the short- and long-run (symmetric and asymmetric) estimates of the variables involved. This study applied econometric procedures such as co-integration and error-correction models to assess the effect of trade openness and FDI on industrialisation.

First, differencing appears to provide the appropriate solution to time series data that are non-stationary with a unit root. Meanwhile, first differencing has the tendency of eliminating all the long-run information which researchers may invariably be interested in. Granger (Citation1986) identified a link between non-stationary processes and preserved the concept of a long-run equilibrium. Two or more variables are said to be co-integrated (i.e. there is a long-run equilibrium relationship), if they share common trends.

7. Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) Approach to co-integration

In order to analyse the symmetric long-run relationships as well as the dynamic interactions among the various variables of interest empirically, the ARDL co-integration procedure developed by Pesaran et al. (Citation2001) was used. The choice of ARDL to estimate the model was informed by the following reasons.

First, the ARDL co-integration procedure is relatively more efficient in small sample data sizes as is the case in this study. This study covers the period from 1983 to 2019. Meaning, the total observation for the study is 37 which is relatively small.

Second, ARDL enables the co-integration to be estimated by the ordinary least square (OLS) method once the lag of the model is identified. This makes this procedure very simple. This is, however, not the case of other multivariate co-integration techniques such as the Johansen co-integration test developed by Johansen & Katarina, (Citation1990).

Third, whether the variables in the model are either I(0) or I(1) or even mutually co-integrated, the ARDL procedure is applicable. In other words, unlike the other conventional techniques such as the Johansen approach, as long as the series are not I(2), this technique can be employed.

Lastly, traditional co-integration methods, such as Johansen (Citation1988), and Johansen and Katarina (Citation1990), may experience endogeneity problem. However, the ARDL method can distinguish between dependent and explanatory variables and eradicate the problems that may arise due to the presence of autocorrelation and endogeneity. ARDL co-integration estimates short-run and long-run relationships simultaneously and provide unbiased and efficient estimates.

Therefore, following Pesaran et al. (Citation2001), as summarised in Nkoro and Uko (Citation2016), the study applied the bounds test procedure by modelling the long-run linear equation, that is, Equationequation (1)(1)

(1) , as a general autoregressive (AR) model of order p, in

:

With representing (k + 1)—a vector of intercept (drift), and

denoting (K + 1)—a vector of trend coefficients, Pesaran et al. (Citation2001) further derived the following vector error correction model (VECM) corresponding to equation (9) as:

Where (k + 1) x (k + 1)-matrices, =

and Γ =

i = 1, 2, …,ρ—1 contain the long-run multipliers and short-run dynamic coefficients of the VECM.

is the vector of variables

and

respectively;

is an I(1) dependent variable defined as

;

(

) is a vector matrix of “forcing” I(0) and I(1) regressors as already defined with a multivariate independent and identical distribution (iid) zero mean error vector

, and a homoscedastic process.

Further, assuming that a unique long-run relationship exists among the variables, the conditional VECM of Equationequation (10)(6)

(6) now becomes:

On the basis of Equationequation (11)(7)

(7) , the symmetric or linear conditional VECM can be specified as:

Where is the drift,

are the symmetric short-run parameters,

are the symmetric long-run parameters and

is the white noise.

8. Non-linear ARDL approach to co-integration

The above specification in Equationequation (8)(8)

(8) is the situation where there is linearity or symmetric effect. Here, there is the general belief that the underlying long-run relationship is following a symmetrically linear combination. In addition, it is assumed that there is no difference between the decomposed partial sum processes of negative and positive impacts of these non-stationary stochastic explanatory variables on industrialisation.

To capture the non-linear model, the study adopted the NARDL approach proposed by Shin et al. (Citation2014). The choice of the NARDL model was influenced by the fact that its properties are similar to the ARDL approach with the additional benefit of being able to assess the asymmetrical effect of the explanatory variables on industrialisation. Thus, it provides the possibility to investigate the impact of a reduction in the explanatory variables on industrialisation compared to the impact of an increase in the explanatory variables on industrialisation. This is an important issue, because the size of a positive change can be different from the size of the impact of a negative change in the absolute terms.

Therefore, following Shin et al. (Citation2014), the study decomposed the changes of the explanatory variables into partial sum processes of both positive and negative to capture their asymmetric impacts on industrialisation. In this direction, the components constructed to capture these effects are as follows:

Where the superscripts (+) and (-) denote the partial sum processes of positive (increases) and negative (decreases) changes in the various variables in the period t.

On this basis the conditional non-linear ARDL model was specified as:

Where is the drift,

are the short-run asymmetric parameters,

are the long-run asymmetric parameters and

is the white noise. The responses of industrialisation to increases and decreases in the explanatory variables can be quantified through the asymmetric dynamic multipliers as follows:

By construction, when

and

where

and

are the asymmetric long-run coefficients as illustrated above. Based on the estimated multipliers, it is possible to observe both the path from the old to the new equilibrium following a positive or negative shock and the equivalent duration of the temporary disequilibria.

9. Results and discussion

9.1. Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics of the relevant variables involved in the study are presented in Table . The descriptive statistics included the mean, median, maximum, minimum, standard deviation, skewness, Jarque-Bera and its probability as well as the number of observations.

Table 2. Summary statistics of the regressand and the regressors

From Table , it was observed that out of 37 observations for all the variables, the average (mean) values appeared positive. However so, from the skewness results presented, it can be seen that industrialisation (INDUS), trade openness (TOP) and gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) were negatively skewed, implying that majority of the values for these variables are greater than their means of 22.9, 67.1 and 18.8 respectively. Meanwhile, foreign direct investment (FDI) was positively skewed, which implied that majority of its values were less than its mean of 2.3.

More so, the minimal deviation of the variables from their means as shown by the standard deviation gave indication of low fluctuation of the variables over the period under consideration. Further, considering the P-value of the Jarque-Bera statistic for each variable, it was evidenced that all the variables under consideration in this study were normally distributed. They proved to be normally distributed with their probability values being higher than the critical value of 0.05.

9.2. Unit root test results

Although the bounds test (ARDL and NARDL) approach to co-integration does not require the pretesting of the variables for unit roots, however, it is imperative to perform unit root test in order to verify that the variables are not integrated of an order higher than one. The purpose is to ascertain the absence or otherwise of I(2) variables to exonerate the results from spurious regression. That is to say, there is a need to complement the estimated process with unit root tests to ensure that no variable is integrated in a higher order.

For this reason, unit root tests are conducted to investigate the stationarity properties of the variables. As a result, the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and Phillips-Perron (PP) tests were applied to all the variables in levels and in first difference in order to formally establish their order of integration. The tests were conducted with intercept and time trend in the model. The optimal number of lags and bandwidths included in the test were based on automatic selection by Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Newey-West Bandwidth respectively. The study based its decision, to either reject or accept the null hypothesis that the series contain unit root, by using the P-values in the parenthesis, which arrived at similar conclusions with the critical values.

The results of ADF and PP test for unit root with intercept and trend in the model for all the variables are presented in Tables , respectively. The null hypothesis is that the series is non-stationary, or contain a unit root. The rejection of the null hypothesis is based on the probability values.

Table 3. Results of unit root test with constant and trend: ADF test

Table 4. Results of unit root test with constant and trend: PP test

From the unit root test results in Table , all the variables are insignificant in their levels at any of the traditional level of significance (1%, 5%). Meanwhile, at first difference, they become stationary. Hence, the null hypothesis of the presence of unit root for all the variables at their first difference can be rejected since the P-values of the ADF statistic are significant at 1% level of significance. This is because the null hypothesis of the presence of unit root (non-stationary) is rejected at 1% significant level for all the estimates.

The PP test results for the presence of unit root with intercept and time trend in the model for all the variables are presented in Table . From the unit root results in Table , the null hypothesis of the presence of unit root for all the variables in their levels cannot be rejected since the P-values of the PP statistic are not statistically significant at any of the levels of significance (1%, 5%). Nevertheless, at first difference, all the variables become stationary. This is because the null hypothesis of the presence of unit root (non-stationary) is rejected at 1% significant level for all the estimates.

From the above discussions, it can be seen that the PP unit root test results in Table confirm and are in line with the ADF test in Table . It is therefore clear that none of the variables are integrated of order two, I(2). Since the test results have confirmed the absence of I(2) variables, the ARDL and NARDL methodologies were used for estimation.

9.3. Co-integration analysis

The focus of this study was to ascertain the relationship among trade openness, FDI and industrialisation; hence, it was essential to test for the existence of long-run equilibrium relationship among these variables within the framework of the bounds testing approach to co-integration. A maximum lag length of two for annual data was used in both the ARDL and NARDL bounds tests, since the study employed an annual data. Pesaran et al. (Citation1999); Wooldridge (Citation2016) suggested a maximum lag of two for annual data in the bounds testing to co-integration. After the lag length was determined, an F-test for the joint significance of the coefficients of lagged levels of the variables was conducted.

Pesaran and Pesaran (Citation1997) indicated that “OLS regression in the first difference are of no direct interest” to the bounds co-integration test. It is, however, the F-statistic values of all the regressions when each of the variables are normalised on the other which are of great importance. This F-statistic tests the joint null hypothesis that the coefficients of the lagged levels are zero. In other words, there is no long-run relationship between them, the essence of the F-test is to determine the existence or otherwise of co-integration among the variables in the long-run. The results of the computed F-statistic when INDUS is normalised (i.e. considered as dependent variable) are presented in Table .

Table 5. Bounds test results for symmetric and asymmetric co-integration

From Table , the F-statistic that the joint null hypothesis of lagged level variables (i.e. variable addition test) of the coefficients is zero is rejected at 1% significant level. Further, since the calculated F-statistic of both the symmetric and asymmetric bounds tests exceeded the upper bound of the critical values (i.e. (.) = 7.8193

4.66 for the ARDL bounds test; and

(.) = 10.3164

3.99 for the NARDL bounds test), the null hypothesis of no co-integration, that is, no long-run relationship among industrialisation and its determinants is rejected.

These results indicate that there is exceptional co-integration relationship among industrialisation and its determinants in Ghana and that all the determinants of industrialisation can be treated as the “long-run forcing” variables for the explanation of industrialisation in Ghana. Therefore, since there is the existence of co-integration among the variables, the long-run and short-run estimations were proceeded.

9.3.1. Long-run results

Table showed results of the symmetric and asymmetric long-run estimates based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). The ARDL (2, 0, 2, 0) and NARDL (2, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2) selected by the AIC pass the standard diagnostic test of serial correlation, functional form, normality and heteroscedasticity.

Table 6. Estimated long-run model using ARDL and NARDL approaches

9.3.1.1. Trade openness and industrialisation in Ghana

From Table , the long-run results of trade openness, foreign direct investment, and the control variable (gross fixed capital formation) were presented. The results depicted that, symmetrically, in the long run trade openness exerted no effect on industrialisation in Ghana, since it was not significant at any of the traditional levels of significance. The above notwithstanding, the Wald test result showed that the effect of trade openness on industrialisation was asymmetric in nature. However, the positive shocks in trade openness depicted no effect on industrialisation in Ghana, since the result was not significant at any of the levels of significance. This result refuted the hypothesis that the positive shocks in trade openness have a significant effect on industrialisation in the long run in Ghana. Meanwhile the negative shocks in trade openness exhibited an effect on industrialisation in Ghana, since the result was at 5% significant level. The coefficient of the negative changes in trade openness was 0.637, which implied that, in the long run a percentage fall in trade openness causes industrialisation to also fall by 0.64 percent, all other things being equal. Hence, this finding supported the hypothesis that the negative changes in trade openness have a significant effect on industrialisation.

Therefore, since rises in trade openness exhibited no effect on industrialisation and falls in trade openness caused industrialisation to fall, it indicated that in the long run trade openness was deleterious to industrialisation in the Ghanaian economy. Feasibly, this result revealed the import dependency nature of the Ghanaian economy and as theorised negative shocks in trade lead to fall in export prices and rise in imported products, which adversely affect domestic output and demand, largely stifling local industries from expanding.

Arguably, the result of the asymmetric long-run effect on trade openness proved more practical relevance since the real effects of movements in variables on other variables are mostly asymmetric. However, to the best of my knowledge, since none of the available studies have considered the impact of the shocks in the predictor variables on industrialisation, the results of this study were compared with the symmetric results of studies available. In doing so, it was observed that this result was in line with the findings of Umer and Alam (Citation2013) who showed that trade openness negatively affects industrial sector growth in the long run and Adenutsi (Citation2007) who also found that trade openness in the long run is harmful to industrial performance. Emediegwu (Citation2021), Nnadozie et al. (Citation2021), and Ogu et al. (Citation2016) further found adverse effect of trade openness on industrialisation. However, the result was contrary to the studies of Adamu and Dogan (Citation2017), Adofu and Okwanya (Citation2017), Khobai and Moyo (Citation2020), Tahir et al. (Citation2016), Svilokos et al. (Citation2019), and Umoh and Effiong (Citation2013), who found a positive long-run effect of trade openness on industrialisation.

9.3.1.2. Foreign direct investment and industrialisation in Ghana

The symmetric results, as indicated in Table , also revealed that FDI exerted positive effect on industrialisation at 1% significance level. The coefficient of 1.096 indicated that if FDI increases by one percent, industrialisation has the potential of increasing by 1.1 percent in the long run, ceteris paribus. On the other hand, if FDI decreases by one percent, industrialisation also has the potential of decreasing by 1.1 percent in the long run, ceteris paribus. However, considering the asymmetric results, the Wald test result for FDI indicated the presence of asymmetric effect of FDI on industrialisation, which signified that the rise and fall of FDI in the long run affected industrialisation differently in Ghana.

From the results, the positive changes in FDI were significant at 5% significant level, which justified the hypothesis that positive shocks in FDI have a significant effect on industrialisation in the long run in Ghana over the period under consideration. The positive changes in FDI revealed a positive coefficient of 3.413, which signified that, at 5% significant level, a percentage increase in FDI increases industrialisation by 3.4 percent in the long run, ceteris paribus. Meanwhile, the results of the negative changes in FDI showed that the negative changes in FDI are insignificant at any of the traditional levels of significance. Hence, this result rejected the hypothesis that negative shocks in FDI exhibit a long-run significant effect on industrialisation in Ghana over the period under consideration.

This revealing result explained the assertion by Zhang (Citation2014) that the continues inflow of FDI boosts the productivity of all firms and not just those receiving the foreign capital. Again, this result elucidated the theoretical assertion that FDI inflow leads to the expansion of firms into host countries which causes these recipient countries to industrialise.

The result of the positive changes in FDI was consistent with the findings of some symmetric empirical studies in the literature. Particularly, it agreed with Effiong et al. (Citation2019), who examined the nexus among globalisation, foreign direct investment and industrial sector performance in Nigeria and found that FDI has a significant positive effect on the industrial sector. Iddrisu et al. (Citation2015) also found a significant long-run positive effect of FDI on industrialisation when they assessed the influence of FDI on the productivity of the Ghanaian industrial sector. Similarly, Zhang (Citation2014) and Adegboye et al. (Citation2016) found that significant positive changes in FDI lead to positive changes in industrialisation. Also, the outcome of the negative changes in FDI was in line with some symmetric studies such as Emediegwu (Citation2021), Gui-Diby and Renard (Citation2015), Njangang et al. (Citation2018), Nnadozie et al. (Citation2021), and Samantha and Liu (Citation2018) who found no relationship between FDI and industrialisation in the long-run. However, Adenutsi (Citation2007) found negative long-run effect of FDI on industrialisation.

9.3.2. Short-run estimates

The short-run estimates, just as the long-run estimates, were also based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) employed for the estimation of symmetric (ARDL) and asymmetric (NARDL) models. The results of these estimates were reported in Table .

Table 7. Estimated short-run error correction model using ARDL and NARDL approaches

From Table , the standard regression statistics on both the ARDL and NARDL models were obtained. It was observed that for the symmetric ARDL model the adjusted was approximately 0.89. Which could be explained as approximately 89 percent of the variations in industrialisation was explained by the independent variables. Also, Durbin-Watson (DW) statistic of approximately 2.2 revealed that there was no autocorrelation in the residuals. Further, the results also showed that the coefficient of the lagged error correction term ECT (−1) exhibited the expected negative sign (−0.6871) and is statistically significant at 1 percent significant level. This result indicated that approximately 68 percent of the disequilibrium caused by previous years’ shocks converged back to the long-run equilibrium in the current year.

Correspondingly, the adjusted of the asymmetric (NARDL) model was also approximately 0.97. This, therefore, meant that approximately 97 percent of the variations in industrialisation were explained by the independent variables. Again, a DW statistic of approximately 2.1 revealed that there was no autocorrelation in the residuals. Also, the coefficient of the lagged error correction term ECT (−1) was statistically significant at 1 percent significant level and showed the expected negative sign of −0.4485. This result pointed out that approximately 45 percent of the disequilibrium caused by previous years’ shocks converged back to the long-run equilibrium in the current year.

According to Kremers et al. (Citation1992), a more efficacious way of instituting co-integration is by the error correction term. Thus, the study grasped that, when surprised or disturbed in the short-run, the variables in the model display signs of moderate response to equilibrium. It is theoretically debated that an error correction mechanism exists whenever there is a co-integration relationship among two or more variables. The error correction term is thus obtained from the negative and significant lagged residual of the co-integration. The ECM stands for the rate of adjustment to restore to equilibrium in the dynamic models following a disturbance. The negative coefficient is an indication that any shock that takes place in the short-run will be corrected in the long-run. According to Acheampong (Citation2007), the rule of thumb is that, the larger the error correction coefficient, in absolute terms, the faster the variables equilibrate in the long run when shocked.

From Table , the short-run effect of trade openness, FDI and the control variable (gross fixed capital formation) on industrialisation were depicted. It was seen that the results also presented the lagged form of industrialisation (the dependent variable). This was because industrialisation is a process and that previous levels of industrialisation affect current levels. It can be seen from the symmetric result that the coefficient of the lag industrialisation variable was positive and significant. The positive sign of the coefficient of the lag industrialisation variable meant that previous periods of industrialisation in Ghana contributes positively to the industrialisation process of that of the current periods. This was expected because as a country industrialises it sends signals to prospective investors that the country is a growth prospect of which they may be willing to invest in such country. Hence, as investors troop in, industrialisation in the country is likely to rise further.

However, on the contrary, the asymmetric results showed that the coefficient of the lag industrialisation variable is significant, but negative. This negative sign of the coefficient of the lag industrialisation variable implied that previous periods of industrialisation in Ghana contribute negatively to the industrialisation process of that of the current periods. This reveals the true state of the industrial sector in the country as the downwards trend in the growth of the industrial sector does not appeal to investors.

9.3.2.1. Trade openness and industrialisation in Ghana

From Table , the symmetric results did not present any output on trade openness. Meaning, in the short-run trade openness does not have any relationship with industrialisation in Ghana. In the same vein, the asymmetric results indicated that positive changes in trade openness in the short-run exert no effect on industrialisation. It bears a coefficient of −0.013 but statistically insignificant. Hence, the hypothesis that in the short run the positive shocks in trade openness on industrialisation is significant was rejected by this finding.

However, the above notwithstanding, the current period of the negative changes in trade openness was significant and positive in the short-run. This finding supported the hypothesis that the effect of the negative changes in trade openness on industrialisation is significant in the short-run. The coefficient of 0.107 meant that a percentage fall in the current period of the negative changes in trade openness leads to 0.11 percentage fall in industrialisation in the short-run, and this result was statistically significant at 1%, ceteris paribus. Yet, the previous period of negative changes in trade openness turned to have a significant negative effect on industrialisation. However, their net effect was that as the negative changes in trade openness fall industrialisation also falls in the short-run in Ghana, all other things being equal.

Corollary, from the above discussion, it is obvious that, increases and decreases in trade openness affect industrialisation negatively in the short-run. This result is not surprising in Ghana’s case as negative shocks in trade openness affect domestic firms’ income and equally local demand, which end up reducing total industrial output, rendering some domestic firm to be out of business.

This finding was in line with the findings of Ogu et al. (Citation2016) who established that trade openness hurts manufacturing output in the short-run. More so, Adenutsi (Citation2007) also discovered that trade openness in the short-run is harmful to industrial performance. Further, Umer and Alam (Citation2013) found that the effect of trade openness on industrialisation is insignificant in the short run. Iddrisu et al. (Citation2015), also found no effect of trade openness on industrial sector growth in the short run. Meanwhile, Adamu and Dogan (Citation2017), Adofu and Okwanya (Citation2017), Khobai and Moyo (Citation2020), Tahir et al. (Citation2016), and Umoh and Effiong (Citation2013) expressed contradictory results. They found that trade openness positively affect industrialisation in the short-run.

9.3.2.2. Foreign direct investment and industrialisation in Ghana

The symmetric results from Table showed that FDI and its lag assumed a negative sign and are statistically significant, which signalled an unfavourable effect on industrialisation in the short term. The coefficient of −0.686 indicated that in the short-run, at a level of significance of 5%, when FDI increases by one present, industrialisation will decrease by 0.69 percent and when FDI decreases by one present, industrialisation will increase by 0.69 percent, ceteris paribus.

However, interestingly, the asymmetric results revealed that, in the short-run, whenever FDI is rising in the current period, it impacts on industrialisation positively, although for a short while, since its lag portrayed an opposite result. On the other hand, in the short-run, the current period of decreases in FDI exhibited a negative effect on industrialisation, however, in its one lag period, it exerted a positive effect on industrialisation. These results were significant at 1% for the positive changes in FDI and at 5% for the negative changes in FDI. Meaning, the results justified the hypothesis that the short-run effect of the positive and negative changes in FDI on industrialisation in Ghana is significant.

Considering the positive changes in FDI, the coefficient of 0.778 indicated that a percentage increase in FDI causes industrialisation to increase by 0.78 percent, ceteris paribus. This result is at 1% significant level. This notwithstanding, negative changes in FDI also showed a coefficient of −1.303. Indicating that a percentage fall in FDI leads to 1.3 percentage increase in industrialisation in the short term and this result is at 5% significant level, ceteris paribus. This can be attested to the fact that FDI has been channelled into more viable sectors of the Ghanaian economy. Key among the latest recipients are the crude oil, mining, banking and telecommunications sectors.

Therefore, generally, it has been attested by this result that the current year’s rise and fall in FDI increases industrialisation in Ghana in the short-run. These results were supported by Effiong et al. (Citation2019), Zhang (Citation2014), and Adenutsi (Citation2007) who found that FDI in the short-run positively affect industrialisation. However, these findings were inconsistent with the findings of Njangang et al. (Citation2018), Samantha and Liu (Citation2018), Gui-Diby and Renard (Citation2015), and Iddrisu et al. (Citation2015), who found that FDI do not have significant impact on industrialisation.

9.4. Model diagnostic tests

Diagnostic tests were conducted for both the ARDL and NARDL models. Table presented the summary of the results of the various tests.

Table 8. Diagnostic tests

The diagnostic tests, as reported in Table , indicated that the P-value of the F-statistic of the Breusch-Godfrey Serial Correlation LM test was 0.567 for the ARDL model and 0.753 for the NARDL model and both were greater than the critical value of 0.05, hence, the test show evidence of non-existence of autocorrelation. Meaning the estimated models passed the Lagrange Multiplier test of residual serial correlation among variables.

Also, the P-values of the F-statistic of the Ramsey Reset test of 0.946 and 0.099 for both the ARDL and the NARDL models respectively were above the critical value of 0.05. This implied that the models were correctly specified and that the estimated models passed the tests for Functional Form Misspecification using square of the fitted values. Further the test of Normality was conducted. The P-values of the Jarque-Bera statistic of 0.8 and 0.883 for both models were above the critical value of 0.05. This indicated that the models were normally distributed. Hence, the models also passed the Normality tests based on the skewness and kurtosis of the residuals. Thus, the residuals of both models were normally distributed across observation. Finally, heteroskedasticity test was also conducted and the estimated models passed the test. Thus, the F-statistic of the Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey heteroskedasticity test displayed P-values of 0.153 and 0.166 for both the ARDL and the NARDL models respectively, which are more than the critical value of 0.05. Hence, we accept that there is no heteroscedasticity and conclude that the errors are not changing over time.

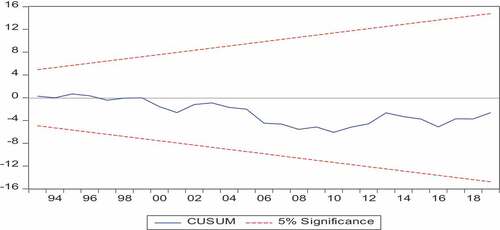

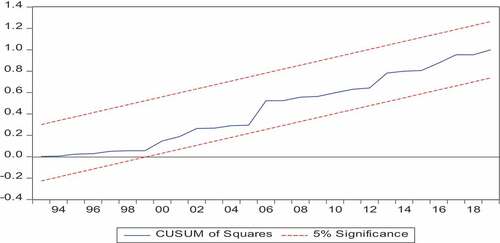

9.5. Stability tests

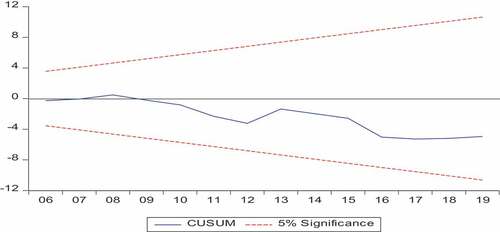

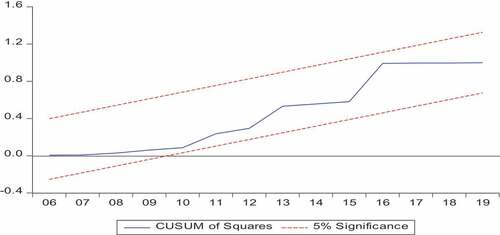

In order to assess the stability of both the ARDL and the NARDL models Pesaran and Pesaran (Citation1997) and Shin et al. (Citation2014) suggested that the test for the stability for parameters using cumulative sum of recursive residuals (CUSUM) and cumulative sum of squares of recursive residuals (CUSUMSQ) plots be conducted after the models are estimated. This is done to eliminate any bias in the results of the estimated models due to unstable parameters. Also, the stability test is appropriate in time series data, especially when one is uncertain about when structural changes might have taken place.

The results for the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ for both the ARDL and the NARDL models are presented in Appendices (A) (Figure ) and (B) (Figure ), respectively. The null hypothesis is that the coefficient vector is the same in every period and the alternative is that it is not the same in every period (Bahmani-Oskooee & Nasir, Citation2004). The CUSUM and CUSUMSQ statistics are plotted against the critical bound of 5% significant level. According to Bahmani-Oskooee and Nasir (Citation2004), if the plot of these statistics remains within the critical bounds of 5% significance level, the null hypothesis that all coefficients are stable cannot be rejected.

Appendices A(1) (Figure ) and B(1) (Figure ) depict the plots of CUSUM for the estimated ARDL and NARDL models respectively. The plots suggest the absence of instability of the coefficients since the plots of all coefficients fall within the critical bounds at 5% significance level. Thus, all the coefficients of the estimated models are stable over the period of the study. Again, appendices A(2) and B(2) depict the plots of CUSUMSQ for the estimated ARDL and NARDL models respectively. The plots also suggest the absence of instability of the coefficients since the plots of all coefficients fall within the critical bounds at 5% significance level. Thus, all the coefficients of the estimated models are stable over the period of the study.

9.6. Dynamic multipliers of the NARDL model

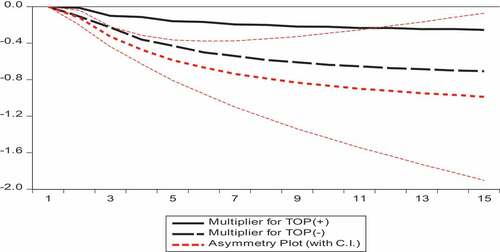

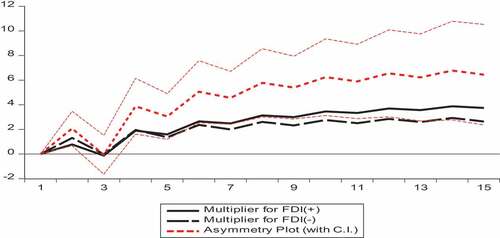

The asymmetric cumulative dynamic multipliers show the patterns of adjustment of the dependent variable to its new long-run equilibrium following a positive or negative shock in the regressor (Shin et al., Citation2014). From the graphs, the asymmetric plot reflects the difference between the dynamic multipliers of positive and negative changes in the regressor.

9.6.1. Dynamic multiplier of trade openness on industrialisation

Figure shows the dynamic effect of positive and negative changes of trade openness on industrialisation in Ghana.

From Figure , it can be seen that both lines of the positive and negative shocks in trade openness lie below the zero-horizontal line, thus, they lie in the negatives. This means that both positive and negative changes in trade openness exert negative effect on industrialisation in Ghana. This explains why the asymmetric plot lies below both the lines of the positive and negative shocks in trade openness; however, it lies in between the upper and lower bounds of 5% significant level.

Further, it can be seen from Figure that both the positive and negative shocks in trade openness are further apart at their tail end than their beginning; indicating that the negative effect on industrialisation by either the positive or negative changes in trade openness is more pronounced in the long-run than in the short-run. Also, it can be observed that the magnitude of decrease in industrialisation due to a positive shock in trade openness is smaller than the magnitude of decrease in industrialisation due to a negative shock in trade openness.

9.6.2. Dynamic multiplier of FDI on industrialisation

Figure depicts the dynamic effect of positive and negative changes of FDI on industrialisation in Ghana.

From Figure , it can be seen that both lines of the positive and negative shocks in FDI lie above the zero-horizontal line. This means that both positive and negative changes in FDI exert positive effect on industrialisation in Ghana. This explains why the asymmetric plot lies above both the lines of the positive and negative shocks in FDI. All the same, the asymmetry plot lies between the upper and lower bounds of 5% significant level.

More so, as shown from the graph, both positive and negative shocks in FDI are slightly apart at their tail end but stayed very closed together at the early stages; signifying that the positive effect on industrialisation by either the positive or negative changes in FDI is more pronounced in the long-run than in the short-run. Finally, it can be observed that the magnitude of increase in industrialisation due to a positive shock in FDI is larger than the magnitude of increase in industrialisation due to a negative shock in FDI.

10. Discussion and conclusion

10.1. Conclusions

The study sought to examine the asymmetric effect of trade openness and FDI on industrialisation in Ghana. In doing so, the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) and the Non-linear Autoregressive Distributed Lag (NARDL) models were employed. Symmetrically, in the long-run, it was revealed that there is no relationship between trade openness and industrialisation in Ghana. Nevertheless, the Wald test demonstrated that the relationship between trade openness and industrialisation is asymmetric in the long-run, however, the positive changes in trade openness conformed to the symmetric result in that it exerted no effect on industrialisation in Ghana. Meanwhile, it was discovered that in the long-run decreases in trade openness causes industrialisation to fall.

Regarding the short-run dynamics, it was revealed that, symmetrically, there is no relationship between trade openness and industrialisation in Ghana. But asymmetrically, it was revealed that increases in trade openness were insignificant, while decreases in trade openness and its lag were significant. However, considering the decreases in trade openness and its lag, it was established that their net effect has a positive effect on industrialisation. Meaning, as trade openness falls industrialisation also falls in the short-run in Ghana, ceteris paribus.

Moreover, in the long-run, the symmetric results revealed that FDI exerts positive relationship on industrialisation, which meant that as FDI rises industrialisation also rises and when FDI falls industrialisation also falls. However, the Wald test result indicated that the relationship between FDI and industrialisation is asymmetric. In considering the asymmetric result, it was identified that positive changes in FDI exert positive effect on industrialisation but negative changes in FDI exert no effect on industrialisation, meaning as FDI rises industrialisation rises and as FDI falls industrialisation remains unaffected in the long run in Ghana, all other things being equal.

Also, regarding the short-run results on FDI, it was found that, symmetrically, FDI exercises negative effect on industrialisation in the short-run. Meaning, as FDI rises industrialisation falls and as FDI falls industrialisation rises in the short-run. Meanwhile, the effect of the positive and negative changes in FDI exert positive and negative effects on industrialisation respectively. Meaning, as FDI increases industrialisation increases and as FDI decreases, industrialisation still increases. However, the one period lags of the positive and negative changes in FDI showed that these increases in industrialisation caused by FDI is just for a short period.

10.2. Theoretical implications

Feasibly, this result revealed the import dependency nature of the Ghanaian economy and as theorised negative shocks in trade lead to fall in export prices and rise in imported products, which adversely affect domestic output and demand, largely stifling local industries from expanding. The outcome on trade openness contradicts the classical theories of trade openness by Smith (Citation1776) and Ricardo (Citation1817), mercantilism as well as the Hecksher-Ohlin theory who argued that trade openness promotes competition which propagates pressure for increased efficiencies, product improvements and technological changes which in the long run turns to increase output of domestic firms leading to domestic countries industrialisation which ultimately stimulate economic growth. Accordingly, trade openness is detrimental to industrialisation and generally to economic growth in that it comes with it unhealthy competition which may force domestic firms out of business and also serves as a means for dumping goods by advanced countries which could lead to deterioration of the economy if adopted by developing economies (Ayibor, Citation2012).

Regarding the theories of FDI (the capital market, internalisation, international production and industrial organisation theories), the presence of FDI leads to the establishment of firms in host countries which increase their firm base leading to the industrialisation of these host countries. Again, the economic and socio-political stability shocks influence the flow of FDI such that FDI flows to countries with higher prospects of net gain on investment. The results support the theoretical deduction that FDI contributes positively to the industrialisation process of a country such as Ghana.

10.3. Practical implications

It can be concluded that trade openness in both the long- and short-run is detrimental to industrial progress in Ghana as the study found that trade openness is only significant when it is falling and as it falls it moves in the same direction with industrialisation. More so, FDI is much needed for Ghana to industrialise her country, since the study found that in the long-run and in the current year of the short-run, positive changes in FDI is significant and contributes positively to the industrialisation of the Ghanaian economy.

We recommend that government policies should the channelled to reduce the external shocks faced by traders, most especially exporters. These policies can be implemented by adding value to exported primary product other than exporting them in their raw form, strengthening the local currency and stabilising the exchange rate. When these are done the external shocks by trade openness may be reduced and the positive impact of trade openness on industrialisation may be realised. Also, since the shocks in FDI rises industrialisation in both the long- and short-run in Ghana, mainly the positive shocks, it is recommended that government policies should be focused on encouraging and attracting more foreign investors to invest in the country.

10.4. Limitations and future research

The interaction of the predictor variable was ignored in the industrialisation nexus. Future studies can consider the interaction of the predictor variables in examining their effect on industrialisation, since it has been theorised that trade openness has the potential of attracting FDI. Again, the impact of the individual components of trade openness (export and import) on industrialisation can be assessed. Further, other measures not considered in this study such as: the share of employment in the industrial sector to total employment as proxy for industrialisation, trade intensity as a measure for trade openness and industrial output by foreign-invested enterprises as a proxy for foreign direct investment, can be explored. Moreover, future studies can also employ other estimation techniques other than those employed in this study. It must also be noted that the sample size used for this study although above 30 (statistically considered as a large sample) could influence the results of the current study. It is pertinent for future studies to perform similar estimations by expanding the sample size to enhance representativeness, reliability and generalisation of the results.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

The data is available upon request

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abeka, M. J. (2018). Trade openness and financial development in Sub-Saharan Africa: the role of institutional quality. ( Doctoral dissertation, University of Cape Coast). https://scholar.google.co.uk/scholar?hl=en≈sdt=0%2C5&q=Abeka%2C+M.+J.+%282018%29.&btnG=

- Acheampong, I. K. (2007). Testing Mckinnon-Shaw thesis in the context of Ghana’s financial sector liberalisation episode. International Journal of Management Research and Technology, 1(2), 156–28.

- Adamu, F. M., & Dogan, E. (2017). Trade openness and industrial growth: Evidence from Nigeria. Panoeconomicus, 64(3), 297–314. https://doi.org/10.2298/PAN150130029A

- Adegboye, F. B., Ojo, J. A., & Ogunrinola, I. I. (2016). Foreign direct investment and industrial performance in Africa. The Social Sciences, 11(24), 5830–5837.

- Adenutsi, D. E. (2007). Effects of trade openness and foreign direct investment on industrial performance in Ghana. Journal of Business Research, 2(1), 71–89. https://doi.org/10.4314/jbr.v2i1-2.43212

- Adofu, I., & Okwanya, I. (2017). Linkages between trade openness, productivity and industrialization in Nigeria: A co-integration test. Research in World Economy, 8(2), 78–87. https://doi.org/10.5430/rwe.v8n2p78

- Ayibor, R. E. (2012). Trade liberalisation and economic growth in Ghana. Unpublished master’s thesis. University of Cape Coast.

- Bahmani-Oskooee, M., & Nasir, A. B. M. (2004). ARDL approach to test the productivity bias hypothesis. Review of Development Economics, 8(3), 483–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9361.2004.00247.x

- Bodman, P., & Le, T. (2013). Assessing the roles that absorptive capacity and economic distance play in the foreign direct investment-productivity growth nexus. Applied Economics, 45(8), 1027–1039. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2011.613789

- Davidson, J., Meenagh, D., Minford, P., & Wickens, M. (2010). Why crises happen-nonstationary macroeconomics. Cardiff Working Paper Series (pp. 1–13). Cardiff Business School, University of Cardiff.

- Di Pace, F., Juvenal, L., & Petrella, I. (2020). Terms-of-trade shocks are not all alike. Bank of English Working Paper (pp. 1–28). IMF Working Papers.

- Effiong, C. E., Odey, F. I., & Nwafor, J. U. (2019). Globalization, foreign direct investment and industrial sector performance nexus in Nigeria. International Journal of Social Sciences and Management Research, 5(2), 58–70.

- Emediegwu, L. (2021). Does foreign direct investment matter for industrialisation in Nigeria? Zambia Social Science Journal, 7(1), 31. https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/zssj/vol7/iss1/3

- Fenny, A. P. (2017). Ghana’s Path to an industrial–led growth: The role of decentralisation policies. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 9(11), 22–34. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v9n11p22

- Granger, C. W. J. (1986). Developments in the study of cointegrated economic variables. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 48(3), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.1986.mp48003002.x

- Gui-Diby, S. L., & Renard, M. F. (2015). Foreign direct investment inflows and the industrialization of African countries. World Development, 74, 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.04.005

- Iddrisu, A. A., Adam, B., & Halidu, B. O. (2015). The influence of foreign direct investment (FDI) on the productivity of the industrial sector in Ghana. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences, 5(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARAFMS/v5-i3/1736

- Jie, L., & Shamshedin, A. (2019). The impact of FDI on industrialization in Ethiopia. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 9(7), 726–742. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i7/6175

- Johansen, S. (1988). Statistical analysis of cointegration vectors. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 12(2–3), 231–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1889(88)90041-3

- Johansen, S., & Katarina, J. (1990). Maximum likelihood estimation and inference on cointegration with applications to demand for money. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 52(2), 169–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.1990.mp52002003.x

- Khobai, H., & Moyo, C. (2020). Trade openness and industry performance in SADC countries: Is the manufacturing sector different? International Economics and Economic Policy, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-020-00476-0

- Kremers, J., Ericson, N. R., & Dolado, J. J. (1992). The power of cointegration tests. Board of governors of the federal reserve system. International Finance Discussion Paper, 431(431), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.17016/IFDP.1992.431

- Majumder, S. C. (2019). Impacts of FDI inflows on domestic investment, trade, education, labor forces and energy consumption in Bangladesh. European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences, 8(2), –316.

- Majumder, S. C., & Rahman, M. H. (2020). Impact of foreign direct investment on economic growth of China after economic reform. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Business and Economics, 8(2), 120–153.

- Majumder, S. C., Rahman, M. H., & Martial, A. A. A. (2022). The effects of foreign direct investment on export processing zones in Bangladesh using generalized method of moments approach. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 6(1), 100277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2022.100277

- Miah, M. M., & Majumder, S. C. (2020). An empirical investigation of the impact of FDI, export and gross domestic savings on the economic growth in Bangladesh. The Economics and Finance Letters, 7(2), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.29.2020.72.255.267

- Njangang, H., Chameni, N. C., & Nembot, N. L. (2018). Can Chinese foreign direct investment promote industrialization in African countries? Cameroon. University of Dschang https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/89726/

- Nkoa, B. E. O. (2016). Foreign direct investment and industrialization of Africa: A new approach. Innovations, 51(3), 173–196.

- Nkoro, E., & Uko, A. K. (2016). Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) cointegration technique: Application and interpretation. Journal of Statistical and Econometric Methods, 5(4), 63–91.

- Nnadozie, O. O., Emediegwu, L. E., & Monye-Emina, A. (2021). Does foreign direct investment matter for industrialisation in Nigeria? Zambia Social Science Journal, 7(1), 3. https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/zssj/vol7/iss1/3

- Ogu, C., Aniebo, C., & Elekwa, P. (2016). Does trade liberalization hurt Nigeria’s manufacturing sector. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 8(6), 6. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v8n6p175

- Opoku, E. E. O., Ibrahim, M., & Sare, Y. A. (2019). Foreign direct investment, sectoral effects and economic growth in Africa. International Economic Journal, 33(3), 473–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/10168737.2019.1613440

- Opoku, E. E. O., & Yan, I. K. M. (2019). Industrialization as driver of sustainable economic growth in Africa. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 28(1), 30–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2018.1483416

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2017). Entrepreneurship and industrialisation. OECD.

- Pesaran, M. H., & Pesaran, B. (1997). Working with microfit 4.0. Oxford University Press.

- Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (1998). An autoregressive distributed-lag modelling approach to cointegration analysis. Econometric Society Monographs, 31, 371–413. https://ideas.repec.org//p/cam/camdae/9514.html