?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Diversifying rural livelihoods plays a significant role for rain feed-dependent economy of the rural households like in Ethiopia. Hence the objective of the study was to investigate the determinants of rural households’ livelihood diversification strategies choice in north wollo zone of Ethiopia. A multi-stage stratified random sampling technique was used to select 384 rural household heads as a sample in study areas. Primary data was collected from sample rural household heads using an interview schedule. Multivariate Probit Model was employed to identify the factors influencing the rural household heads’ decision to choose livelihood strategies. The model result showed that agriculture livelihood strategy was positively and significantly associated with male headed household, land holding, cooperative membership, and participation in rural productive safety net program; while it is negatively and significantly affected by distance to market. Non-farm livelihood strategy was positively and significantly affected by dependency ratio, education level, total income, and remittance; while it is negatively and significantly affected by the sex of household head and participation in rural productive safety net program. Off-farm livelihood strategy was positively and significantly influenced by sex of household head; while it is negatively and significantly affected by the land holding, total livestock unit, cooperative membership, credit use, participation in rural productive safety net program. Therefore, the study recommends that local government should attempt to promote the above significant determinants of rural households’ livelihood diversification strategies choice to build more profitable and sustainable livelihood strategies.

1. Introduction

Agriculture-based livelihood is vulnerable to the effect of several nature-induced hazards such as flash floods, droughts, riverbank erosions, and embankment damages (Ahmad & Afzal, Citation2020; Ferdushi et al., Citation2019). To cope with the changing situation, reduce loss from farming activities, secure economic and environmental shocks rural households are adopting on-farm (planting drought-tolerant crops and mixed farming), non-farm (mining, manufacturing, utilities, construction, commerce, transport, masonry, carpentry, petty trade, and government services), and off-farm (income activity takes place away from the farm typically includes all wage or exchange labour on other farms, and labour payments in kind such as harvest sharing and other non-wage labour contracts) diversification strategies (Ellis Citation1998; Baird & Hartter, Citation2017; Barrett et al., Citation2001; Gautam & Andersen, Citation2016; Haggblade et al., Citation2010; Kabir et al., Citation2017; Kassie, Citation2017; Losch et al., Citation2012; Martin & Lorenzen, Citation2016); these diversified activities allow farming households to manage risk and improve their lives (Aniah et al., Citation2019; Baird & Hartter, Citation2017).

In rural Ethiopia, farming is the main source of livelihood for the overwhelming majority of farming households, but it has long been established that households tend to diversify their income sources (Degefa, Citation2005; Demeke & Regassa, Citation1996). As for Amsalu et al. (Citation2014) finding, rural households diversify their activities into off-farm and non-farm activities to offset the diverse forms of risks and uncertainties that are associated with agriculture such as variability in soil quality, pests and diseases, price shock, unpredictable rainfall, floods, erosion menace, and weather-related events. Rural households combine a diverse set of economic and social activities, which construct a portfolio of livelihood income-generating activities like agriculture, migration, mining, and tourism to meet and enhance sustainable rural livelihood outcomes (Davis et al., Citation2010; Jiao et al., Citation2017; Khatiwada et al., Citation2017; Pagnani et al., Citation2020; Uddin et al., Citation2018). Rural households also tend to diversify and pursue a portfolio of activities rather than a single activity for their livelihood (Barrett et al., Citation2001; Dercon & Krishnan, Citation1996; Ellis, Citation1998; Janvry & Sadoulet, Citation2001; Rahut & Scharf, Citation2012a); hence, it is important to look into a livelihood portfolio rather than a single activity. Livelihood is not just income or employment; rather, it includes various aspects of living. Rural livelihoods can be derived from a range of farm, off-farm, and non-farm activities, which together provides a variety of means and strategies for living.

In other words, livelihood is a means of living, skills required, property/assets, and activities (Chambers & Conway, Citation1992). Whereas diversification of livelihoods is a mechanism by which rural households in their struggle for survival and improvement in their living standards develop a diverse portfolio of activities and social support capabilities (Ellis, Citation1998). A livelihood strategy is a combination of assets and activities to earn income. Livelihood diversification is a process by which households build a portfolio of different activities and assets in order to survive and improve their standards of living (Ellis, Citation1998). Livelihood strategies comprises the households’ capabilities, income activities, and assets holding (natural, physical, human, financial, and social) that contribute to a means of living (Chambers & Conway, Citation1992; Islam et al., Citation2013; Rahman & Hickey, Citation2020). Livelihood diversification strategies have become an issue of central interest to development researchers and policymakers. According to Loison (Citation2019), livelihood diversification plays a crucial role in promoting economic growth and reducing rural poverty in developing countries.

Therefore, diversification of the rural economy’ refers to a sectoral shift of rural activities away from farm to non-farm activities, associated with the expansion of the rural non-farm economy (Start, Citation2001). Side by side, non-agricultural activities (secondary and tertiary) provide an important source of income for the households in rural area. Since agriculture is associated with risk and uncertainties, farming households rely on both agricultural and non-agricultural activities to secure their livelihood (Asmah, Citation2011; Martin & Lorenzen, Citation2016). As several studies point out, crop cultivation and non-crop occupation should go hand in hand for improved and sustainable living of farmers (Dev et al., Citation2002; Khatun & Roy, Citation2012; Meena et al., Citation2017). Currently, most rural households are engaged in agriculture, but it does not produce enough food to meet their needs. This is because farming systems are facing constraints such as small land size, lack of resources, and increasing degradation of soil quality that hamper sustainable crop production and food security. The effects of climate change (e.g., frequent occurrence of extreme weather events) exacerbate these problems. That is why households are forced to engage in non-farm activities (Singh et al., Citation2018). However, the growth in non-farm employment opportunities remained inadequate to absorb the surplus labour left agriculture sector due to push factors. Therefore, creation of non-farm and off-farm employment opportunities for rural households holds the key for a sustainable livelihood (Roy et al., Citation2018). It is the process of combining both agricultural and non-agricultural activities to survive and improve the standard of living (Martin & Lorenzen, Citation2016; Pritchard et al., Citation2019). Different studies indicate that, rather than promoting specialization within existing portfolios, improving returns to existing non-farm activities to increase income could be more realistic and relevant for poverty reduction (Barrett et al., Citation2001; Ellis & Freeman, Citation2005).

However, there are several factors, such as education level, number of livestock, farming experiences that affect the adoption of diversified activities (Akhtar et al., Citation2019). Most importantly, the age of the household head, along with possession of crop land and distance from markets, is an essential determinant of rural households’ livelihood diversification strategy (P. Corral & Radchenko, Citation2017; Ismail et al., Citation2018; Tesfaye et al., Citation2011). Households with low levels of education, less land, and fewer livestock have a higher probability of being engaged in agricultural wage employment (Maertens, Citation2000). As different studies said, educational attainment is one of the most important determinants of non-farm earnings, especially in more remunerative employment as education is an important part of human capital, which determines both participation in and income from non-farm activities (Barrett et al., Citation2001; Janvry & Sadoulet, Citation2001; Micevska & Rahut, Citation2008; Rahut & Scharf, Citation2012a, Citation2012b; Reardon et al., Citation2001).

Furthermore, studies by Lanjouw (Citation1998) and Adams and He (Citation1995) point out that non-farm income benefits the poor because the share of non-farm income varies inversely with both size of land owned and total income. Household size and structure also affect the ability of a household to supply labor to the non-farm sector (Micevska & Rahut, Citation2008; Rahut & Scharf, Citation2012a, b). In the rural areas of some sub-Saharan African countries, culture also plays an important role in participation in non-farm activities (L. Corral & Reardon, Citation2001; Elbers & Lanjouw, Citation2001). Rural households closer to markets have more opportunities to diversify their income than households located in far-flung villages (Abdulai & CroleRees, Citation2001). Larger households with a large proportion of young male members are able to diversify into non-farm sectors, which require skills and physical energy (Tuan et al., Citation2000). Shortage of capital is a critical problem for poor households to diversify their income (Abdulai & CroleRees, Citation2001). A study by Zerai & Gebreegziabher (Citation2011) indicated that although the rural households are involved in diverse livelihood activities, their participation in non-farm and/or off-farm activities is influenced by a complex and yet empirically unidentified factors (Zerai & Gebreegziabher, Citation2011).

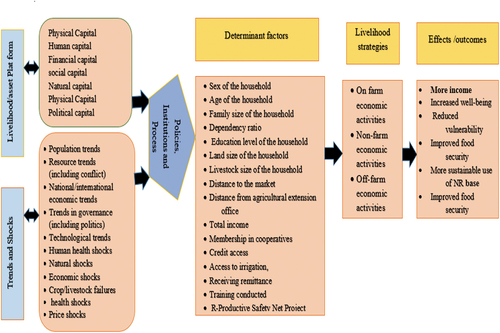

Besides, the determinants of livelihood diversification decision can vary from one local area to another, across time, and individuals and/or community to community (Gebrehiwot & Fekadu, Citation2012). As different literature have shown, the patterns, socioeconomic status, cropping patterns, impacts of rural livelihood diversification on household well-being and poverty reduction, livelihood vulnerability, participation in an activity, and extent of livelihood strategies are different (Ellis, Citation1998; Elbers & Lanjouw, Citation2001; Brouwer et al., Citation2007; Rahut & Scharf, Citation2012a; Gautam & Andersen, Citation2016., Alam et al., Citation2017). There was limited studies conducted study area that has examined and answered the question of what are the deriving determinants of rural households’ livelihood diversification strategies choice in the study area (Figure ).

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework: Determinants of rural livelihood diversifications.

Therefore, there is a gap in knowledge on the choice and determinants of rural households’ livelihood diversification strategies choice in the study area. The objective of this study was to investigate the determinants of rural households’ livelihood diversification strategies choice in the case of North Wollo Zone, Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia.

1.1. Conceptual Research Framework

Based on the information obtained from previous scientific journals, research papers published by well-known scientists and similar materials, the following variables that may positively or negatively affect the household livelihood diversification strategy and related to the research topic were identified. The framework for the analysis of determinants of rural households’ livelihood diversification presented in this paper provides a holistic and integrated view of the processes by which the household achieve or fail to achieve in diversifying rural livelihood strategies. Livelihood strategies of rural households belong to either of three broad categories: On-farm, non-farm, and off-farm activities. On-farm refers to household activities from own-account farming, whether on owner-occupied land or on land accessed through cash or share tenancy. Non-farm activities refer to household participation in non-agricultural activities, including wage employment, business activities. The frame work explains the combination of livelihood resources endowments (or access), policy, institutional settings, and process in the ability of a household to decide which kind of livelihood strategy or combination of livelihood strategies to pursue and what are the immediate outcomes that have been delivered (Figure ).

The households combine their capabilities, skills, and knowledge with different resources at their disposal to create activities that will enable them to achieve the best possible livelihood for themselves including on-farm, non-farm and off-farm economic activities (see Figure ). In asset-based frameworks, capitals are usually allocated across five categories. Households can access a range of assets or resources (physical, natural, economic, human, and social capital) which they can use to engage in farm or non-farm activities or both (Scoones, Citation1998). Livelihood outcomes are the achievements of livelihood strategies, such as more income, increased well-being, reduced vulnerability, improved food security, and a more sustainable use of natural resources (DFID (Department for International Development), Citation1999; Ellis, Citation1998).

A livelihood comprises of assets (resources, claims, and access) and activities (on-farm, non-farm, and off-farm activities) that together determine the way of living a household can afford (Chambers & Conway, Citation1992; Ellis, Citation1999). The decision of rural households to participate in non-/off-farm activities is influenced by individual or household specific factors, as well as other social, economic, and environmental factors (Escobal, Citation2001; Idowu et al., Citation2011; Lay et al., Citation2008). Moreover, the household decisions to do on-farm work directly or indirectly affect their respective decisions to work at non-/off-farm activities, mainly because of the limited available resources households own and can distribute among the livelihood activities because the activities are not mutually exclusive. Policy and institutional context refers to available policies and strategies at the local level regarding property right like land, community’s access to agricultural inputs and financial schemes, and availability of other schemes to households’ livelihood conditions. Knowing the existing livelihood strategies and pointing out the determinant factors affecting rural household livelihood diversification in practicing on-farm, non-farm and off-farm sources of livelihood are unquestionably important in the provision of information to formulate an appropriate strategy.

An important influence on livelihood strategies is exposure to various trends and shocks. Trends and shocks are the events and situations that are beyond the control of the individual/household. Trends include broad changes affecting large sections of the population, for example, demographic and population changes, shifts in the national and global economy, e.g., recession and processes of deindustrialization, as well as changes of government (although the significance of each of these will vary greatly over time and place). Shocks are major events in the life of the individual or household, such as a grief or the loss of a job or home. They represent gradual and sudden change respectively (see Figure ). Shocks can wipe out assets very suddenly if they are not protected and adverse trends can result in gradually eroded if livelihoods are unable to adapt to change.

Based on the above information, the following Conceptual Research Framework is generated that shows the key variables of the study and how their complementation helps in answering the major research problem defined. It also shows the relationships among the basic elements of the framework. Generally, investigating each element laid out in the framework from contextual factors through livelihood resources to strategies and outcomes with an institutional outlook is potentially a significant undertaking for policy formulations to secure rural livelihood.

2. Research methodology

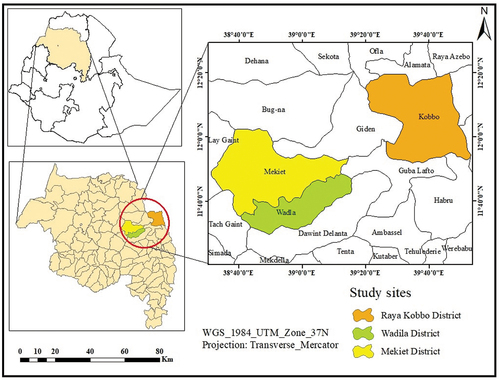

2.1. Descriptions of the Study Area

The North Wollo administrative zone is one of the eleven zones of Amhara Regional state. It is located at about 521 km from the capital city of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. It is composed of 12 administrative districts and 3 registered towns. It has a total population of 1,500,303, of whom 752,895 are males and 747,408 females (Central Statistical Authority, Citation2007). It is situated in the northern part of the country and geographically located at 11°50′N 39°15′E and 11.833°N 39.250°E. North Wollo zone covers an area of 472.1 square kilometers, of which 47.3% is degraded, 24% is arable, 17.4% shrub-land, 4.6% pasture, 0.37% forest, and the remaining 6.3% for all other uses. Most of the land in this zone is steep, rugged, and mountainous, and unsuitable for agriculture. The zone is endowed with many perennial springs, rivers, and seasonal streams. It is bordered by South Wollo in the west, South Gonder in the south, Wag Hemra in the north; Tigray Region in the north east, Afar Region in the east, and part of its southern border is defined by the Mille River.

The people of North Wollo zone are categorized as food insecure, and there is high rate of mobility and migration of people in illegal ways even abroad due to different internal and external factors. All 11 rural districts of this zone have been grouped amongst the 48 districts identified as the most drought prone and food insecure in the Amhara Region (Seid, Citation2011). The livelihood of much of the population depends on agricultural practices (mixed crop-livestock subsistence agriculture has historically remained the mainstay of livelihoods in North Wollo Zone), including both crop production and livestock rearing. Agriculture is the main source of livelihood as nearly 80% of the population depends on agriculture for their livelihood. The dominant crops of the area are wheat, barley, teff, and sorghum. Rain-fed agriculture is the mainstay of the rural economy of north Wollo zone. However, the level of agricultural dependency and its importance to overall household income is vital in the area, the income of the rural households received from agriculture is supplemented by off/non-farm income sources, and households have adopted different strategies to achieve their livelihood outcomes in the study area, even though its degree varies from area to area. Shortage of start-up capital, limited land, poor infrastructure, limited skills, inadequate training, poor working habits of youths, weak marketing systems, and lack of employment opportunities in non-farm or off-farm activities are identified as challenges in the study area (Office of Habru District Agricultural & Rural Development, Citation2019).

2.2. Sampling techniques and determination of the sample size

In this study, multi-stage sampling procedure was employed to select sample households. In the first stage, out of the 12 districts in the Zone, three districts – Raya kobo, Meket, and Wadila districts – are selected purposively to capture different agro-ecological zones existing in the area which may determine household’s livelihood diversification choices. The procedure starts with categorizing the districts into agro-ecological conditions it exhibits: Lowland, midland, and high land. In the second stage, the kebeles (the smallest administrative unit of Ethiopia similar to a ward) in each district were listed based on their agro-ecological characteristics and stratified into three ecological zones: highland, midland, and low land. The first reason is that households in one livelihood zone are relatively assumed to be more homogeneous because they share common livelihood activities than others. The second reason is that all kebeles are vulnerable to drought risk as far as all are rain feed–based livelihood systems. Classifying kebeles based on their livelihood zone helps to attain the most representative sample from the district. Since agro-ecology is a stratifying variable, rural livelihood analysis in Ethiopia is agro-ecological sensitive (Tsegaye, Citation2012). Based on this procedure, 9 kebeles (one kebeles each from lowland, midland, and highland agro-ecological zone) from the selected districts were selected randomly. In the third stage, the probability proportional to sample size methods were applied to draw the sample household heads from each strata according to the number of household heads in different category. When farmers are encouraged to adopt a new practice and when a large population adopt, but that do not know the variability in the proportion that adopt the practices. In this case, Cochran sample size determination formula is appropriate to determine the sample size of the study. Therefore, 384 sample household heads are determined based on the Cochran (Citation1977) formula.

where

Z2 = the abscissa of the normal curve that cuts off an area α at the tails (1—α equals the desired confidence level is 95%),

e = is the desired level of precision, p is the estimated proportion of an attribute that is present in the population, and

q = is 1-p.

Lastly, representative samples will be selected randomly from sampled kebeles of selected districts based on proportional to sample size based on the following formula. Table and Table shows the sample size distribution for each sample of the district of the study areas.

Table 1. Sample size distribution for each sample districts

Table 2. Definition, measurement, and hypothesis of variables used in the MVP Model

2.3. Methods of data collection

This study adopted mixed research approach. In this study, only primary data were used which were qualitative and quantitative in nature. Primary data were collected from sample household heads using an interview scheduled, which is designed to generate data on the household socio-economic, farm, and institutional characteristics that are related to livelihood strategies. The researchers collected the data during the period between February and March 2020. Although questionnaire is an efficient way of getting in-depth quantitative data, it has some limitations on collecting qualitative data (Cheung, Citation2014). Hence, some popular qualitative data collection tools such as Focus Group Discussion (FGD) and Key Informant interview methods have been employed to overcome the limitation.

Accordingly, primary data were collected through FGD and key informant interviews from sampled kebeles through personal interview with checklist to supplement the research finding with qualitative information. FDG at 9 kebeles of the study area was conducted with the selected 7–12 members who are representatives of different section of the populations and organization from each kebeles. The discussion used a semi-structured interview checklist/guide to encourage active participation and in-depth discussion that allows flexibility, and stimulating participants to share and discuss among each other. Furthermore, to get more information about a pressing issue or problem from each district, “Key Informant Interview” was conducted from 10 well-connected and informed offices of the study areas. Prior to actual survey, pre-tests on non-sample respondents of 2 kebeles of Habru and Guibalafto districts for a maximum of 3 days were conducted under supervision of the researcher and necessary modification was made on the basis of the results obtained. The qualitative data were analyzed through narration, summarization, and discussion, whereas the quantitative data were analysed using simple descriptive and inferential statistics.

2.4. Analytical techniques

In order to achieve the stated objectives of the study, the survey data were analysed by using by using STATA software version 14. The study employed descriptive statistics and econometric models to analyse the data. Descriptive statistical tools like frequency, percentage mean, standard deviation, test of significance such as t-test and chi-square test, mean values, and standard deviation were employed on livelihood strategies pursued by rural households.

Regarding choosing models to identify the determinants of rural household decision to engage in various livelihood activities, there is no natural ordering in the alternatives. When there are more than two alternatives the appropriate econometric model would be either Multinomial Logit (MNL) or Multivariate Probit (MVP) regression models. Regarding estimation, both of them estimate the effect of explanatory variables on a dependent variable involving multiple choices with unordered response categories (W. Greene, Citation2000). The MNL is popular in livelihood diversification studies; it fails to explain the factors that lead a household to choose a given number of livelihood strategies simultaneously by clustering households into livelihood strategies categories. It also assumes that if a household has been clustered in a given category of livelihood strategies it does not participate in a strategy that is in another category.

MNL is suitable only when the livelihood strategies are mutually exclusive (independent). But, the MVP model is used for analyzing the factors that significantly influence livelihood diversification choices. MVP model is one form of a correlated binary response regression model that simultaneously estimates the influence of independent variables on more than one dependent variable, and allows for the error terms to be freely correlated (W.H. Greene, Citation2012). It is suitable when the alternative livelihood strategies are not mutually exclusive (interdependent). This study assumed that the selected livelihood strategies are interdependent to one another. Besides, multivariate regression is a technique that estimates a single regression model with more than one outcome variable. When there is more than one predictor variable in a multivariate regression model, the model is a multivariate multiple regressions (Afifi et al., Citation2004). That is why this study used MVP to analyse determinants of rural households’ livelihood diversification strategies in the study area. The individual chooses between more than two choices, once again, making the choice that provides the greatest utility. The choices among the livelihood diversification are not mutually exclusive as rural households are willing to choose more than one strategy at the same time. Therefore, this study used a MVP model as households choose more than one strategy at the same time and collinearity of errors.

The observed outcome of livelihood diversification choice can be modeled following random utility for individual choice (W.H. Greene, Citation2012). Consider the ith rural household (i = 1, 2 … … N), facing a decision problem on whether or not to choose available livelihood strategies. Let U0 represent the utility the household gets by choosing on-farm, and Uk represents the utility of household by choosing the Kth livelihood strategy: where K denotes a choice of any alternative strategy. The observed choice between the two reveals which one provides the greater utility. Hence the household decides to choose the Kth livelihood strategy if Uk > Uo.

The net benefit latent regression model can be specified as:

where

Yik* = Unobserved variable representing the latent utility of choosing strategy k.

Xi = a vector of observed characteristics determining the choice of livelihood strategy.

β = represents a vector of unknown coefficients to be estimated, and ε is a vector of error terms.

The utility Yik* that the household derives from choosing a livelihood strategy is a latent variable determined by observed explanatory variables (X) and the error term (ԑ):

Yik* is an unobservable latent variable denoting the probability of choosing k type of livelihood strategy by an individual, for k = 1 (On-farm), k = 2 (Non-farms), k = 3 (Off-farm). The model can be specified as follows:

Where, Yi1 = 1, if household choose on-farm (0 otherwise), Yi2 = 1, if households choose Non-farm (0 otherwise), Yi3 = 1, if farmer chooses Off-farm (0 otherwise), Xi = vector of factors affecting livelihood strategy choice, β = vector of unknown parameters and εi = is the error term.

2.5. Definition of variables and working hypotheses

2.5.1. Dependent variable

A combination of socioeconomic, demographic, institutional, farm, and location factors are used to examine the determinants of livelihood diversification. The dependent variable in this study is the choice of livelihood strategy, which is a polychromous variable. In study three non-mutually exclusive livelihood diversification strategies are identified. These include on-farm, non-farm, and off-farm income. If the choice of the household lies in livelihood strategies, rational household head chooses among the three non-mutually exclusive livelihood strategy alternatives that offer the maximum utility.

The dependent variable has 3 categories, namely:

k = 1, On-farm

k = 2, Non-farm income

k = 3, Off-farm income

2.6. Justification of the independent variables in the empirical model

In this study, 15 variables are hypothesized to explain determinants of participation in diversified livelihood activities. describes the expected relationship between the dependent variable and independent variables.

3. Results and discussion

Sample households were composed of both male and female household heads. Out of the total sample household heads about 79.95% were male headed and the remaining 20.05% were female headed households (Table ). As of their male counterpart females usually participate in farm, non-farm and off-farm activities.

Table 3. Sex of sample household head (categorical variables)

As shown in Table , out of the total sample respondents, 269 (70.05%) of the sampled households were members of cooperatives and 115 (29.95%) were not organized under any cooperatives. Regarding credit use, 333 (86.72%) of the total sampled households were users of credit and the remaining 51 (13.28%) were credit non-users. The availability of irrigation water is very important because it raises the productivity of the product. According to the survey result, about 237 (61.72%) of respondents have used irrigation services and about 147 (38.28%) are non-users of irrigation water. Regarding remittance 211 (54.95%) of total respondents have received remittance from their relatives or friends abroad during the study period, while 173 (45.05%) of the respondents are non-receivers of remittance. On the topic of productive safety net program 305 (79.43%) of the sampled respondents are participated in the productive safety net program, while the remaining 79 (20.57%) of the respondents have not participated in productive safety net program.

The average age of the sampled household heads, during the survey period, was about 47.98 years with standard deviation of 11.39. The average family size of the sample household heads was 1.97 man equivalents with standard deviation of 1.43. The dependency ratio mean value was 0.79 with standard deviation of 0.58 (Table ). The mean value of sample respondents’ level of formal education was 2.66 years of schooling with standard deviation of 2.08. The average area of land owned by household heads was 0.79 hectares with standard deviation of 0.37. The average livestock holding by household heads in the study area was 2.57 TLU with standard deviation of 1.87. The mean income of household heads was 42,386.38 per year with standard deviation of 17,151.5 (Table ).

Table 4. Demographic, socio-economic, and institutional characteristics of household heads (continuous variables)

The mean distance to the nearest market was 1.61 km with a standard deviation of 0.73 (Table ). The mean extension contact frequency provided for household heads in the study area was found to be 4.79 day per month with standard deviation of 2.44 as mentioned in Table .

3.1. Livelihood diversification strategies adopted by rural households

According to survey result the livelihood diversification strategies in the study area are identified to be agriculture (e.g., crops and livestock); non-farm (e.g., employment and self-employment unrelated to agriculture), and off-farm activities (wage labor on farms). This is in line with Imane (Citation2020), who report sthe same result.

Agriculture is the practice of cultivating plants and rearing livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domestic species created food surpluses that enabled people to live in cities. The major agricultural products can be broadly grouped into foods, fibers, fuels, and raw materials. According to the survey result, 71.6% of total respondents mentioned agriculture as their livelihood strategy (Table ).

Table 5. Summary of the livelihood strategies adopted by rural household

Non-farm activities are those which do not relate to farms or farming. According to the survey result, 64.1% of total respondents mentioned non-farm as their livelihood strategy (Table ). Off-farm activities are those which help to receive cash money from agricultural wage employment and non-agricultural wage employment. According to the survey result, 59.1% of total respondents mentioned off-farm as their livelihood strategy (Table ).

Households in the study area have three major livelihood strategy alternatives to rely on for survival. MVP model was used to analyze the determinants of households decision on livelihood strategies choices as households more likely choose different livelihood strategies simultaneously. The model estimated jointly for three categorical dependent variables, namely: (1) Agriculture, (2) Non-farm, and (3) Off-farm livelihood strategies. The correlation coefficients of the error terms in MVP model had positive as well as negative signs, indicating that there is interdependency between different livelihood strategies chosen by households. The signs of correlation coefficients indicate the complementary and competitive nature of different livelihood strategies.

***

is significant at 1% significance level; this implies that the coefficients are jointly significant and the explanatory power of the factors included in the model is satisfactory. The likelihood ratio test of the null hypothesis of independency between livelihood strategies choice decision (

) is rejected at 1% level of significance (

37.81***). This indicated that among estimated coefficients across the equations in the model there are negative and significant joint correlations between agriculture and non-farm, positive and significant correlations between non-farm and off-farm. However, the correlation between agriculture and off-farm is negative and insignificant. The model result also shows the probability that households that chose agriculture, non-farm, and off-farm livelihood strategies were 72.28%, 64.21%, and 58.89%, respectively. The joint probability of choosing all livelihood strategies was 23.44%, and the joint probability of failure to choose all market outlets was 0.00%.

The MVP model analysis indicated that out of 15 explanatory variables included in the model two variables significantly affected the choice of entire livelihood diversification strategies at different magnitude and probability level. Among the variables included five variables significantly affected the choice of agriculture, while six variables significantly affected the choice of non-farm and off-farm strategies (Table ).

Table 6. Multivariate probit estimation results for determinants livelihood diversification strategies choice

3.2. Sex of Household Head

Sex of household head was positively and significantly associated with the likelihood of participating in Agriculture and off-farm activities at 10% and 5% significant level respectively and negatively and significantly associated with the likelihood of participating in non-farm activities at 10% level of significance. It is also interesting to note that male-headed households are 31.7% and 40.7% more likely to choose agriculture and off-farm activities respectively as their livelihood strategies than female household heads. However, female-headed households are 29.4% more likely to choose non-farm activity as their livelihood strategy. Hence, female-headed households had higher chances of choosing non-farm activity because female-household heads have more connections and are sociable with buyers whom they often meet in markets. While male-headed households are more energetic in agricultural field work on as well as off their farm land. Results from other studies for instance, Kassie et al. (Citation2017), reported that being male household head has significantly influenced agriculture and off-farm livelihood diversification. Additionally, Yishak et al. (Citation2014) implied that female-headed households have difficulty of participation in off-farm activities because of cultural barriers and being more responsible for taking care of children and making food for household rather than for market.

3.3. Dependency Ratio

Dependence ratio has positively and significantly affected the likelihood of choosing non-farm activities at 5% significant level. This means when the dependency ratio increases, the ability of farmers to meet family needs decreases and a chance for alternative livelihood to non-farm activities increases. This result is in line with the finding of Richard (Citation2017), Wegedie et al. (Citation2018), and Amevenku et al. (Citation2019) who indicated that those households with high dependent ratio are more likely to choose non-farm livelihood strategies.

3.4. Formal Education Level of Household Head (EDUHH)

Education level of household head has a positive and significant effect at 10% probability level in choosing non-farm livelihood strategy. The positive relationship between formal education level and non-farm activity can be explained by the fact that being educated enhances the capability of households in making informed decisions with regard to the choice of non-farm business activities. This might be due to their improved capacity to look at available opportunities of revenue-generating non-farm business activities and a better probability of taking calculated risks. This result concurs with findings of Dzanku (Citation2015), Ahmed (Citation2016), and Eshetu and Mekonnen (Citation2016), Yishak (Citation2017), A. Asfaw et al. (Citation2017), and Gebru et al. (Citation2018) who reported that households are relatively better educated, have better access to technologies, and look for alternative livelihood opportunities like non-farm activities.

3.5. Land Holding (LAND)

Land holding was found to influence the probability of livelihood diversification into agricultural activity positively and significantly at 10% probability level, while it influenced the probability of livelihood diversification into off-farm activity negatively and significantly at 1% significant level. The result showed that a unit increment in land holding could result in increasing the probability of household’s engagement in agricultural activities by about 46.3% and decreasing the probability of household’s engagement in off-farm activities by about 89.4%. That means households having more land size depend on crop production than to go for off-farm activities on someone else’s farm land. The result is similar to the findings of Sallawu et al. (Citation2016) and A. Asfaw et al. (Citation2017).

3.6. Livestock (LVSTKTLU)

The likelihood of choosing off-farm livelihood activity was negatively and significantly affected by total livestock unit at 1% levels of significance. Households who owned more livestock were found to be more likely not to engage in off-farm activity than those with less livestock holding. The negative associations may imply that households with more livestock had better income and benefits associated with selling of livestock and livestock products. In addition to that, oxen and horse are used for agricultural production processes. Farm households that have many oxen and horses may rent them out and collect non-farm income. Consequently they were more likely to not choose off-farm activities. This result is in line with the results found by Adepoju and Obayelu (Citation2013), Rahman and Akter (Citation2014), and S. Asfaw et al. (Citation2015).

3.7. Distance to market (DISTMK)

Analogous to priori expectations, distance to market negatively and significantly influenced the likelihood of choosing agriculture as livelihood strategy at 1% significant level. Households whose residence are far from nearest market are more likely to not engage in crop production as it is difficult to take their produce to market due to distance and bad weather roads. This is similar to the findings of A. Asfaw et al. (Citation2017), who reported that farmers who lived further away from the market centres are less likely to be involved in agricultural activities. In addition, it is clear that the more households are distant from market center, the more disadvantaged from diversifying their livelihood income into non-farm options whereas the nearest market for rural farmers encourage participating in livelihood diversification strategies as the results found by Riithi (Citation2015), Gebru et al. (Citation2018), and Amevenku et al. (Citation2019).

3.8. Total Income (TOTINC)

The result indicated that total income positively and significantly affected the probability of the households to engage in non-farm activities at 1% probability level. Wealthy households lean towards non-farm business activities as their livelihood strategy as compared to those households with low income. The finding showed the necessity to consider financial position of households in designing development intervention systems which would offer chances for those households with lower income. A similar result was reported by Yishak et al. (Citation2014) and Adem and Tesafa (Citation2020) who found that total income has a positive and significant influence on the level of income diversification in to non-farm activities.

3.9. Cooperative Membership

Cooperative membership had a significant and positive relationship with the likelihood of choosing agricultural activities at 1% significance level. However, cooperative membership had a significant and negative relationship with the likelihood of choosing off-farm activities at 1% level of significance. This is because those households belonging to cooperative were easily access information about the profitability of agricultural activity and the benefit from profit bonus in the future in addition to the product price as compared to the cooperative non-members. Besides, households who are members of formal cooperatives gain benefits like sharing income and labour, access to credit, reduced individual transaction cost, and updated market information on farm produce such as on inputs and farm equipment. The result is in agreement with previous findings obtained by Khatun and Roy (Citation2012) and Kassie et al. (Citation2017).

3.10. Credit Use

Credit use negatively and significantly affected the likelihood of household’s engagement in off-farm activity at 10% level of significance. Use of credit services had reduced the probability of choosing off-farm activities as livelihood strategy. This is probably due to the fact that use of credit facility can relieve the existing financial limitations of the household for the time being, letting farm households shift from off-farm activity to the strengthening of agricultural activity by purchasing and adopting better farm technologies or non-farm business activities. This result is coinciding with the finding of Kassie et al. (Citation2017), Amevenku et al. (Citation2019), and Dinku (201 8) who reported the same result.

3.11. Remittance

Remittance was positively and significantly associated with the likelihood of households to choose non-farm activities at 1% significant level. The more the income received from remittance the more the chance to engage in non-farm activity. This might be due to the fact that increasing rural households remittance income plays a vital role for enhancing and smoothing household consumption problem, strengthening social network/social capital, increasing saving and investment, helping households gain access to diversified opportunities like trading, and then being able to improve their livelihood. The result is supported by the findings of Adem and Tesafa (Citation2020), Dinku (Citation2018), and Amevenku et al. (Citation2019).

3.12. RPSFTNTP

Participation in rural productive safety net program positively and significantly affected household’s probability of selecting agricultural activity at 1% level of significance. On the other hand, it affected the probability of the households to choose non-farm and off-farm activities negatively and significantly at 5% significant level each. This might be because in rural Ethiopia, rural productive safety net program is intended to supply mainly agricultural inputs so that households have much higher chances to participate in agricultural activities rather than other activities.

4. Conclusions and recommendations

4.1. Conclusions

The study was aimed at analyzing the determinants of rural households’ livelihood diversification strategies choice. To meet the objectives of the study primary data were collected from 384 sample respondents using pre-tested structured interview schedule. Determinants of rural households’ livelihood diversification strategies choice were analyzed using MVP model.

The model result showed that sex of household head was positively and significantly associated with the rural households’ likelihood of participating in agriculture and off-farm activities at 10% and 5% significant level, respectively, and negatively and significantly associated with the likelihood of participating in non-farm activities at 10% level of significance. Dependency ratio has positively and significantly affected the likelihood of choosing non-farm activities at 5% significant level. Education level of household head has positive and significant effect at 10% probability level in choosing non-farm livelihood strategy. Land holding was found to influence the probability of rural households’ livelihood diversification into agricultural activity positively and significantly at 10% probability level, while it influenced the probability of rural households’ livelihood diversification into off-farm activity negatively and significantly at 1% significant level. The likelihood of choosing off-farm livelihood activity was negatively and significantly affected by total livestock unit at 1% level of significance. Distance to market negatively and significantly influenced the likelihood of choosing agriculture as rural households’ livelihood strategy at 1% significant level.

In addition, total income positively and significantly affected the probability of the rural households’ to engage in non-farm activities at 1% probability level. Cooperative membership had a significant and positive relationship with the likelihood of choosing agricultural activities at 1% significance level. However, cooperative membership had a significant and negative relationship with the likelihood of choosing off-farm activities at 1% level of significance. Credit use negatively and significantly affected the likelihood of household’s engagement in off-farm activity at 10% level of significance. Remittance was positively and significantly associated with the likelihood of rural households to choose non-farm activities at 1% significant level. Participation in rural productive safety net program positively and significantly affected rural household’s probability of selecting agricultural activity at 1% level of significance. On the other hand, it affected the probability of the rural households’ to choose non-farm and off-farm activities negatively and significantly at 5% significant level each.

In general, the study concluded that the demographic, socio-economic, and institutional factors play a vital role in determining rural households’ livelihood diversification strategies’ choice decision in the study area. Hence, solid efforts should be made on significant determinants to promote the diversification of rural households’ livelihood strategies choice in the study area to transform the local context and enable poor households to build more profitable livelihood strategies.

4.2. Recommendations

Depending up on the findings of the study the following recommendations are made to be considered the significant variables for the promotion of livelihood diversification strategies to benefit rural households.

Awareness creation must be conducted among the community to participate women equally with men in all development activities by building potential recognition for female-headed households so that they can uplift their readiness to take risks, which will sooner or later improve their selection of livelihood strategies such as agriculture, off-farm in addition to non-farm activities only.

Facilitate and providing trainings are very critical for those households who have dependent household members to participate on different non-farm activities to earn an additional income and supplement their main income source.

There should be an investment for formal education which will extend the chances of rural households’ participation in all livelihood diversification strategies.

Suitable policies and strategies need to be developed, specifically for land resources as land holding was found to influence the probability of livelihood diversification.

Improving rural households’ livestock holdings through provision of new breeds, forage, veterinary drugs, and vaccination for seasonal livestock diseases will permit households to diversify their livelihood strategies and income.

Market infrastructure needs to be developed, repairing roads and improving road networks, minimizing transportation and other marketing costs which in turn improve households to diversify their livelihood strategies.

Annual earnings of the households should be enhanced through the creation of jobs that will provide exceptional desire to diversify their livelihoods strategies.

Improving credit availability and improving credit institutional arrangements are strongly advised in order to promote the participation of households in non-farm and agricultural livelihood strategies.

Authors’ contributions

The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The author wants to declare that he can submit the data at any time based on publisher’s request. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the author on reasonable request.

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdulai, A., & CroleRees, A. (2001). Determinants of income diversification amongst rural households in Southern Mali. Food Policy, 26(4), 437–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-9192(01)00013-6

- Adams, R. H., & He, J. J. (1995). Sources of income inequality and poverty in rural Pakistan. Research Report 102. International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Adem, M., & Tesafa, F. (2020). Intensity of income diversification among small-holder farmers in Asayita Woreda, Afar Region, Ethiopia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 8, 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2020.1759394

- Adepoju, A. O., & Obayelu, O. A. (2013). Livelihood diversification and welfare of rural households in Ondo State, Nigeria. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 5(12), 482–489. https://doi.org/10.5897/JDAE2013.0497

- Afifi, A., Clark, V. A., & May, S. (2004). Computer-aided multivariate analysis, fourth edition. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 16(1), 67–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/09622802070160010604

- Ahmad, D., & Afzal, M. (2020). Flood hazards and factors influencing house-hold food perception and mitigation strategies in Pakistan. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27(13), 15375–15387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-08057-z

- Ahmed, B. (2016). What factors contribute to the smallholder farmers’ farm income differential? Evidence from east Hararghe, Oromia, Ethiopia. Journal of Asian Scientific Research, 6(7), 112–119. www.aessweb.com

- Akhtar, S., Li, G. C., Nazir, A., Razzaq, A., Ullah, R., Faisal, M., Naseer, M. A. U. R., & Raza, M. H. (2019). Maize production under risk: The simultaneous adoption of off-farm income diversification and agricultural credit to manage risk. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 18(2), 460–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-3119(18)61968-9

- Alam, M. S. U., Ahmed, J. U., Mannaf, M., Fatema, K., & Mozahid, M. N. (2017). Farm and non-farm income diversification in selected Areas of Sunamganj district of Bangladesh. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics and Sociology, 27(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.9734/AJAEES/2017/36873

- Amevenku, F. K. Y., Asravor, R. K., & Kuwornu, J. K. M. (2019). Determinants of livelihood strategies of fishing households in the volta Basin, Ghana. Cogent Economics & Finance, 7(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2019.1595291

- Amsalu, B., Kindie, G., Belay, K., & Chaurasia, S. P. R. (2014). The role of rural labor market in reducing poverty in West Ethiopia. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 6(7), 299–308. https://doi.org/10.5897/JDAE2013.0518

- Aniah, P., Kaunza-Nu-Dem, M. K., & Ayembilla, J. A. (2019). Smallholder farmers’ livelihood adaptation to climate variability and ecological changes in the Savanna agroecological zone of Ghana. Heliyon, 5(4), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01492

- Asfaw, S., McCarthy, N., Paolantonio, A., Cavatassi, R., Amare, M., & Lipper, L. (2015). Diversification, climate risk and vulnerability to poverty: Evidence from rural Malawi. FAO-ESA Working Paper, 2015, 15–22.

- Asfaw, A., Simane, B., Hassen, A., & Bantider, A. (2017). Determinants of non-farm livelihood diversification: Evidence from rain-fed dependent smallholder farmers in north central Ethiopia (Woleka sub-basin). Development Studies Research, 4(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/21665095.2017.1413411

- Asmah, E. E. (2011). Rural livelihood diversification and agricultural household welfare in Ghana. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 3(7), 325–334. http://www.academicjournals.org/JDAE

- Baird, T. D., & Hartter, J. (2017). Livelihood diversification, mobile phones and information diversity in Northern Tanzania. Land Use Policy, 67, 460–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.05.031

- Barrett, C. B., Reardon, T., & Webb, P. (2001). Nonfarm income diversification and household livelihood strategies in rural Africa: Concepts, dynamics, and policy implications. Food Policy, 26(4), 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-9192(01

- Brouwer, R., Akter, S., Brander, L., & Haque, E. (2007). Socioeconomic vulnerability and adaptation to environmental risk: A case study of climate change and flooding in Bangladesh. Risk Analysis, 27(2), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2007.00884.x

- Central Statistical Authority. (2007). Population And Housing Census Of Ethiopia: Administrative Report.

- Chambers, R., & Conway, R. (1992). Sustainable rural livelihood: Practical concept for the 21st century, Discussion paper, IDS No. 296. Institute of Development Studies.

- Cheung, K. L. A. (2014). Structured questionnaires. In Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 6399–6402). Springer.

- Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques (3rd) ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Corral, P., & Radchenko, N. (2017). What’s so spatial about diversification in Nigeria? World Development, 95, 231–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.02.028

- Corral, L., & Reardon, T. (2001). Rural nonfarm incomes in Nicaragua. World Development, 29(3), 427–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00109-1

- Davis, B., Winters, P., Carletto, G., Covarrubias, K., Quiñones, E. J., Zezza, A., Stamoulis, K., Azzarri, C., & Di Giuseppe, S. (2010). A cross-country comparison of rural income generating activities. World Development, 38(1), 48–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.01.003

- Degefa, T. (2005. Rural Livelihoods, Poverty and Food Insecurity in Ethiopia: A Case Study at Erenssa and Garbi Communities in Oromiya Zone, Amhara National Regional State. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Geography, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU, Trondheim.

- Demeke, M., & Regassa, T. (1996). Non-farm activities in Ethiopia: The case of North Shoa. In B. Kebede & M. Taddesse (Eds.), The Ethiopian Economy, poverty and poverty Alleviation proceedings of the Fifth Annual Conference on the Ethiopian Economy (pp. 39–62). Ethiopian Economic Association.

- Dercon, S., & Krishnan, P. (1996). Income portfolios in rural Ethiopia and Tanzania: Choices and constraints. Journal of Development Studies, 32(6), 850–875. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220389608422443

- Dev, U. K., Rao, G. D. N., Rao, Y. M., & Slater, R. (2002). Diversification and livelihood d options: A study of two villages in Andhra Pradesh, India 1975-2001. ODI Working Paper No. 178.

- DFID (Department for International Development). (1999). Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets (Sections 1 & 2). (Accessed November 24, 2016). http://www.eldis.org/go/topics/dossiers/livelihoods

- Dinku, A. M. (2018). Determinants of livelihood diversification strategies in Borena pastoralist communities of Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. Agriculture & Food Security, 7(41), 2–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-018-0192-2

- Dzanku, F. M. (2015). Transient rural livelihoods and poverty in Ghana. Journal of Rural Studies, 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.06.009

- Elbers, C., & Lanjouw, P. (2001). Intersectoral transfer, growth, and inequality in rural Ecuador. World Development, 29(3), 481–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00110-8

- Ellis, F. (1998). Household strategies and rural livelihood diversification. Journal of Development Studies, 35(1), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220389808422553

- Ellis, F. (1999). Rural Livelihood Diversity In Developing Countries: Evidence And Policy Implications. Overseas Institute Development, 40, 1. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/42765249

- Ellis, F., & Freeman, H. A. (2005). Comparative evidence from four African countries. In F. Ellis & H. A. Freeman (Eds.), Rural Livelihoods and Poverty Reduction Policies (pp. 31–47). Rutledge.

- Escobal, J. (2001). The determinants of non-farm income diversification in rural Peru. World Development, 29(3), 497–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00104-2

- Eshetu, F., & Mekonnen, E. (2016). Determinants of of farm income diversification and its effect on rural household poverty in Gamo Gofa Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 8(10), 215–227. https://doi.org/10.5897/JDAE2016-0736

- Ferdushi, K. F., Ismail, M. T., & Kamil, A. A. (2019). Perceptions, knowledge and adaptation about climate change: A study on farmers of haor areas after a flash flood in Bangladesh. Climate, 7(7), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli7070085

- Gautam, Y., & Andersen, P. (2016). Rural livelihood diversification and household well-being: Insights from Humla, Nepal. Journal of Rural Studies, 44, 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.02.001

- Gebrehiwot, W., & Fekadu, B. (2012). Rural household livelihood strategies in drought-prone areas: A case of Gulomekeda District, the eastern zone of Tigray, Ethiopia. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 4(6), 158–168. https://doi.org/10.5897/JDAE12.026

- Gebru, G. W., Ichoku, H. E., & Phil-Eze, P. O. (2018). Determinants of livelihood diversification strategies in Eastern Tigray Region of Ethiopia. Agriculture Food Security, 7(62), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-018-0214-0

- Greene, W. (2000). Econometric analysis. Prentice Hall.

- Greene, W. H. (2012). Econometric Analysis (7th) ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Haggblade, S., Hazell, P., & Reardon, T. (2010). The rural non-farm economy: Prospects for growth and poverty reduction. World Development, 38(10), 1429–1441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.06.008

- Idowu, A. O., Aihonsu, J. O. Y., Olubanjo, O. O., & Shittu, A. M. (2011). Determinants of income diversification amongst rural farm households in South West Nigeria. Economics and Finance Review, 1(5), 31–43.

- Imane, H. (2020). Livelihood Diversification Strategies: Resisting Vulnerability in Egypt, GLO Discussion Paper, No. 441, Global Labor Organization (GLO). http://hdl.handle.net/10419/210455

- Islam, M. R., Hoque, M. N., Galib, S. M., & Rahman, M. A. (2013). Livelihood of the fishermen in Monirampur upazila of Jessore district Bangladesh. J Fish, 1(1), 37–41. https://doi.org/10.17017/j.fish.72

- Ismail, N., Okazaki, K., Ochiai, C., & Fernandez, G. (2018). Livelihood strategies after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami in Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Procedia Engineering, (212), 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2018.01.071

- Janvry, A., & Sadoulet, E. (2001). Income strategies among rural households in Mexico: The role of off-farm activities. World Development, (29)(3), 467–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00113-3

- Jiao, X., Pouliot, M., & Walelign, S. Z. (2017). Livelihood strategies and dynamics in rural Cambodia. World Develop, 97, 266–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.04.019

- Kabir, M. J., Cramb, R., Alauddin, M., Roth, C., & Crimp, S. (2017). Farmers’ perceptions of and responses to environmental change in southwest coastal Bangladesh. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 58(3), 362–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12165

- Kassie, G. W. (2017). The Nexus between livelihood diversification and farmland management strategies in rural Ethiopia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 5(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2016.1275087

- Kassie, G. W., Kim, S., Francisco, P., & Fellizar, J. R. (2017). Determinant factors of livelihood diversification: Evidence from Ethiopia. Cogent Social Sciences, 3(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2017.1369490

- Khatiwada, S. P., Deng, W., Paudel, P., Khatiwada, J. R., Zhang, J., & Su, Y. (2017). Household livelihood strategies and implication for poverty reduction in rural areas of central Nepal. Sustainability, 9(612), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040612

- Khatun, D., & Roy, B. C. (2012). Rural livelihood diversification in West Bengal: Determinants and constraints. Agricultural Economics and Resource Review, 251, 115–124.

- Lanjouw, P. (1998). Poverty and the non-farm economy in Mexico’s ejidos: 1994–1997. In Background Paper Prepared for Economic Adjustment and Institutional Reform: Mexico’s Ejido Sector Responds. World Bank.

- Lay, J., Mahmood, T. O., & M’mukaria, G. M. (2008). Few opportunities, much desperation: The dichotomy of non-agricultural activities and inequality in western Kenya. World Development, 36(12), 2713–2732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.12.003

- Loison, S. A. (2019). Household livelihood diversification and gender: Panel evidence from rural Kenya. Journal of Rural Studies, 69, 156–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.03.001

- Losch, B., Freguin-Gresh, S., & White, E. T. (2012). Structural transformation and rural change revisited: Challenges for late developing countries in a globalizing world. Agence Française de Development and the World Bank. World Bank Publications.

- Maertens, M. (2000). Activity Portfolios in Rural Ethiopia: Choices and Constraints. A Paper Presented at the American Agricultural Economics Association 2000 Annual Meeting.

- Martin, S. M., & Lorenzen, K. A. I. (2016). Livelihood diversification in rural Laos. World Development, (83), 231– 243, 83, 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.01.018

- Meena, P. C., Kumar, R., Sivaramane, N., Kumar, S., Srinivas, K., Dhandapani, A., & Khan, E. (2017). Non-Farm Income as an Instrument for Doubling Farmers’ Income: Evidences from Longitudinal Household Survey. Agricultural Economic Research Review, 30, 127–137. https://doi.org/10.5958/0974-0279.2017.00027.1

- Micevska, M., & Rahut, D. B. (2008). Rural nonfarm employment and incomes in the Himalayas. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 57(1), 163–193. https://doi.org/10.1086/590460

- Office of Habru District Agricultural & Rural Development. (2019). Annual report of the Woreda. North Wollo Zone, Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia.

- Pagnani, T., Gotor, E., & Caracciolo, F. (2020). Adaptive strategies enhance smallholders’ livelihood resilience in Bihar India. Food Security, 13, 419–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01110-2

- Pritchard, B., Rammohan, A., & Vicol, M. (2019). The importance of non-farm livelihoods for household food security and dietary diversity in rural Myanmar. Journal of Rural Studies, (67), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.02.017

- Rahman, S., & Akter, S. (2014). Determinants of Livelihood Choices: An Empirical Analysis from Rural Bangladesh. Journal of South Asian Development, 9(3), 287–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973174114549101

- Rahman, H. M. T., & Hickey, G. M. (2020). An analytical framework for assessing context-specific rural livelihood vulnerability. Sustainability, 12(14), 5654. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145654

- Rahut, D. B., & Scharf, M. M. (2012a). Livelihood diversification strategies in the Himalayas. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, (56)(4), 558–582. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8489.2012.00596.x

- Rahut, D. B., & Scharf, M. M. (2012b). Non-farm employment and incomes in rural Cambodia. Asian-Pacific Economic Literature, (26)(2), 54–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8411.2012.01345.x

- Reardon, T., Berdegue, J., & Escobar, G. (2001). Rural nonfarm employment and incomes in Latin America: Overview and policy implications. World Development, 29(3), 395–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00112-1

- Richard, K. A. (2017). Livelihood diversification strategies to climate change among smallholder farmers In Northern Ghana. Journal of International Development, 30, 8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3330

- Riithi, N. A. (2015). Determinants of choice of alternative livelihood diversification strategies in solio resettlement scheme, Kenya. A thesis submitted to the Department of Agricultural Economics in partial fulfillment for the award of a Master of Science degree in Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of Nairobi.

- Roy, B. C., Khatun, D., & Roy, A. (2018). Rural Livelihood Diversification in West Bengal; Study No.- 189 (pp. xiii+85). Agro-Economic Research Centre.

- Sallawu, H., Tanko, L., Nmadu, J. N., & Ndanitsa, A. M. (2016). Determinants of income diversification among farm households in Niger state, Nigeria. Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences, 2(50), 55–65. https://doi.org/10.18551/rjoas.2016-02.07

- Scoones, I. (1998). Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis. Working Paper 72, Institute for Development Studies, Brighton, UK.

- Seid, Y. (2011). Small-Scale Irrigation and Household Food Security: A Case Study of Three Irrigation Schemes in Gubalafto Woreda of North Wollo Zone, Amhara Region”. Master’s Thesis Graduate School of the University of Addis. 34–42.

- Singh, R. D., Tewari, P., Dhaila, P., & Tamta, K. K. (2018). Diversifying livelihood options of timberline resource dependent communities in Uttarakhand Himalayas: Conservation and development implications. Tropical Ecology, 59(2), 327–338. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329128792

- Start, D. (2001). The rise and fall of the rural non-farm economy: Poverty impacts and policy options. Development Policy Review, 19(4), 491–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7679.00147

- Tesfaye, Y., Roos, A., Campbell, B. M., & Bohlin, F. (2011). Livelihood strategies and the role of forest income in participatory-managed forests of Dodola area in the bale highlands, southern Ethiopia. Policy Economics, (3)(4), 258–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2011.01.002

- Tsegaye, M. (2012). Vulnerability, Land, Livelihoods and Migration Nexus in Rural Ethiopia: A Case Study in South Gondar Zone of Amhara Regional State. International institute of social studies.

- Tuan, F., Somwaru, A., & Diao, X. (2000). Rural Labor Migration, Characteristics, and Employment Patterns. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- Uddin, M. T., Dhar, A. R., & Hossain, N. (2018). A socioeconomic study on farming practices and livelihood status of haor farmers in kishoreganj District: Natural calamities perspective. Bangladesh Journal of Extension Education, 30(1), 27–42. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335160930

- Wegedie, K. T., Lankoande, Y. B., Sanogo, S., Compaore, Y., & Senderowicz, L. (2018). Determinants of peri-urban households’ livelihood strategy choices: An empirical study of Bahir Dar city, Ethiopia. Cogent Social Sciences, 4, 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1514688

- Yishak, G. (2017). Rural farm households’ income diversification: The Case of Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Social science, 6(2), 45–46. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ss.20170602.12

- Yishak, G., Gezahegn, A., Tesfaye, L., & Dawit, A. (2014). Rural household livelihood strategies: Options and determinants in the case of Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Journal of Social Sciences, 3(3), 92–104.

- Zerai, B., & Gebreegziabher, Z. (2011). Effect of nonfarm income on household food security in Eastern Tigrai. Ethiopia: An Entitlement Approach. Food Science and Quality Management, 1, 1–22.