Abstract

The complex relationship between profit margins and environmental sustainability practices (ESPs) in Ghana’s manufacturing industry is examined in this study. Utilizing information gathered from six manufacturing firms, the study uses regression analysis to examine how different ESPs affect profit margins. The hypothetical statements were tested using analysis of variance (ANOVA). ANOVA was used to ascertain the variability between the dependent and independent variables. The result from the model summary showed a significant relationship between the MCs’ profit margins and their ESPs. The results show that although certain ESPs, like using conventional pollution protection techniques, may only slightly raise profit margins, others, like putting modern pollution control technology into practice, may drastically lower profitability. Furthermore, the study emphasizes how waste management and environmental regulations have a favorable impact on profit margins, indicating that businesses that have strong environmental strategies typically have better financial results. However, the study also reveals the possible downsides of programs like eco-awards and environmental socialization, which have expenses but little return on investment. Overall, the study highlights the intricate relationship between economic performance and environmental sustainability in Ghanaian manufacturing, providing useful information for industry stakeholders and policymakers who want to support sustainable development practices without sacrificing profitability. By providing empirical evidence of the connection between ESPs and profit margins, the study advances academic knowledge and improves corporate economics and environmental management knowledge. The design of incentive programs and regulatory frameworks to support sustainable behaviors can be informed by findings, that balance environmental responsibility and financial feasibility.

1. Introduction

To achieve better value addition and contribute to a nation’s socioeconomic prosperity, manufactured items must undergo more refining from their basic components. In the tertiary sector, produced goods are marketed to encourage socioeconomic progress. This system requires the industrial sector to automatically collect raw materials from the primary sector and transform them into completed goods to fulfill human needs. Notwithstanding these advantages, it is noted that extended mechanical manufacturing is exacerbating global energy consumption, wastewater production, waste, and residue problems (Lee et al., Citation2022). Simply put, the industrial process degrades the environment by removing raw materials from it and producing rubbish that contaminates the same. This conclusion also makes it right the fact that the environment of modern manufacturing companies (MCs) is less secure (Chandio et al., Citation2022). With the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, environmental deterioration and pollution increased at an alarming rate. Industrialization, through advanced manufacturing, was viewed as a sine qua non for development, and as a result, manufacturing operations were launched without regard for long-term implications for the environment (Akuoko & Bour, Citation2013; Le Quéré et al., Citation2016). This resulted in massive physical damage to our environment and its devastating effects. As a result, the modern world is said to be beset with numerous problems, including poverty, climate change, unemployment, poor health, hunger, and food insecurity (Adu et al., Citation2023; Bour et al., Citation2023; Draghici, Citation2019). In late 2021, a group of climate experts warned the world, particularly poor nations, about the facts and consequences of climate change (Draghici, Citation2019). Due to unrestrained industrial activities, cocoa production in Ghana and Ivory Coast faces extinction by 2050 due to environmental issues in Africa (Adu et al., Citation2023; Barima et al., Citation2016). By 2080, a rise of 5–8% is predicted in the proportion of dry and semi-arid regions in Africa (Barima et al., Citation2016; Bour et al., Citation2019). Aside from worsening some nations’ present water stress levels, climate change will also raise the likelihood of water stress for others who now enjoy it.

It’s also true that the society we live in now demands that some things be changed, most notably the way we create things, that is, moving from non-green to green production. Green manufacturing, also known as environmental awareness manufacturing, is a contemporary manufacturing approach that takes into account the utilization of raw materials and the impact on the environment throughout the production process. The long-term growth of human society is promoted, as is the use of the circular economy model in the contemporary industrial sector (Bjørnbet et al., Citation2021; Kumar et al., Citation2019). The Brundtland Commission's 1987 mandate to examine the sustainable integration of economic activity and environmental well-being gave rise to the "circular economy" (CE) notion. To enhance ecological functionality and human well-being, as well as to contribute more to sustainable business models, CE places a strong emphasis on process redesign and material recycling (Adu et al., Citation2024; Kumar et al., Citation2019). Climate change, air, water, and soil pollution, biodiversity loss, and resource depletion are a few of the environmental challenges of the twenty-first century. According to Lundberg et al. (Citation2019), addressing ecological problems requires changing a wide range of human behaviors, from the individual citizen-actor to corporations and governments.

Every inhabitant of Ghana has been feeling the effects of climate change, according to Mesti (Citation2013), which can be seen in events like floods, droughts, and a rise in the frequency of high maximum temperatures. Moreover, Ghana’s CO2 emissions rose sharply between 1990 and 2007, rising from 3927.80 kt to about 9801.20 kt. Methane emissions have also gone up from about 7237.60 kt in 1990 to 8989.50 kt in the present. The nation’s emissions of particulate matter (PM10) have increased, rising from around 34.5 micrograms per cubic meter in 1991 to approximately 42.1 in 2001 (Mesti, Citation2013). Ghana’s total greenhouse gas emissions for the year 2019 were 58.56 MtCO2e, or million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, which is 16% more than what it was in 2016 (Seini, Citation2022). The nation’s waterways have also been contaminated due to inadequate waste disposal practices and discharges from industries and agriculture. Tragically, the World Bank (Citation2020) warned that environmentally unsound practices might hamper Ghana’s economic expansion. The body of research indicates that industrial companies need to answer for the horrific damage they are causing to the environment (Bour et al., Citation2019). This is because producing goods was seen as a means of advancement without giving the effects on the environment any thought. The corporate climate has become more competitive due to the omnipresent needs of clients. It has been shown that several manufacturing companies release both organic and inorganic waste into the environment, especially into air and water bodies. These substances include acids, highly poisonous minerals like arsenic or mercury, and hazardous organic compounds. Serious repercussions from such environmental injustice might include the unfitness of the water for residential use and even agriculture. Pollutants have the potential to penetrate the food chain and harm animals’ and humans’ health (Carter, Citation2018; Songsore, Citation2004). These effects on health are rather worrisome.

Paradoxically, for these MCs to register or incorporate as economic organizations, they must submit their environmental sustainability plans and strategies to the EPA (Bour et al., Citation2019). What then went wrong? What stands in the way of these MCs keeping their word to the EPA and the nation at large? Is there an issue with the connection between profit and ESPs?

None of the empirical studies that have been used to support the existing literature’s claims regarding pollution and environmental deterioration have looked at the relationships between profit and ESPs. For example, Kumar et al. (Citation2019) looked at sustainable business models and how to optimize human well-being and ecological functioning. The focus of the studies by Bour et al. (Citation2019); Bjørnbet et al. (Citation2021); Kumar et al. (Citation2019) and Kwakwa et al. (Citation2022) was on environmental deterioration, pollution, and the consequences of economic activity on the environment and human health. Therefore, rather than concentrating on the dynamics of polluter behavior, much of this research in the field of environmental sustainability has concentrated on chemicals or pollutants (Bour et al., Citation2019; Songsore, Citation2004). Consequently, the following were established as the main goals of this study to close the previously described gap: (1) To ascertain the reason behind MCs’ failure to reach their ES goals. (2) To forecast if there would be a decline or rise in profit regarding ESPs. (3) To offer suggestions for corporate governance and policy development.

This study deals with the policy-level issue of striking a balance between environmental sustainability and economic viability in Ghana’s industrial sector. In particular, it looks at how manufacturing organizations’ adoption and use of Environmental Sustainability Practices (ESPs) are influenced by profit as a predictor variable. By examining this link, the research hopes to shed light on how we may achieve green manufacturing in the modern day, where sustainable practices must be encouraged without sacrificing the industry’s potential to make money.

These provided the impetus for the conduct of this study, which thus, adds a social science viewpoint to the ongoing debate on environmental sustainability (ES) and manufacturing in terms of identifying profit motive as a determinant of ESPs of MCs in Ghana. By doing so, that gap in the literature is filled. The study’s findings are more broadly applicable to environmental sustainability objectives and policies, not only for Ghana but also for other developing nations with comparable industrial sectors dealing with comparable issues, the resulting policies may be more broadly applicable. However, this paper is presented in logical, sequential sections to enhance the reader’s appreciation of the importance of the paper. Section ‘Introduction’ discusses the introduction, ‘Literature Reviews’, literature reviews, hypotheses, and conceptual framework, while Sections ‘Methods’ and ‘Discussion and results’ present the methods and the discussion of results, respectively. Section ‘Conclusion’, on the other hand, presents the paper’s limitations and policy implications.

Literature review

The theoretical basis of the article

The main theory on which this paper rests is Hardin (Citation1968) tragedy of the commons theory, which posits that users of common properties such as the environment cannot be left to decide how to use them and that their use of such property has to be controlled to avoid over-exploitation of it. Hardin sought to draw the attention of humanity to the basic problem that, there is a rift between the short-term welfare of individuals and the long-term welfare of society and the environment. Hardin’s ideas are consciously or unconsciously embodied in the treadmill of production theory by Schnaiberg (Citation2012) which posits that there is an inherent need for an economic system (capitalist) to continually yield profit by creating consumer demand for new products through advertising, even if this means stretching the ecosystem beyond its physical limits to growth or carrying capacity. This explains why environmental assaults are prominent in manufacturing locations around the world, and the growing worry about the ever-increasing environmental deterioration caused by industrial activity (Khan et al., Citation2022, Citation2023).

As a consequence, many researchers actively participate in finding answers to this problem by influencing public policy discussions with their research findings (Brulle & Roberts, Citation2017). Others are analyzing movements in favor of the sharing economy and degrowth, which indicate that history may be about to change. That is, a widespread countermovement against market-centric neo-liberalism may be forthcoming as Karl Polanyi had predicted in the 1944s in The Great Transformation (Brechin & Lee, Citation2023; Stuart et al., Citation2023). Similar to the views of other researchers, Polanyi believed that the economy should be structured to best serve social welfare and environmental conservation not the other way around.

Alternative models are concrete, achievable, and eminently doable. Even while creating alternatives to the treadmill is likely to be far easier than defeating it. Treadmill theory gives global citizens and activists the psychological comfort of knowing that the neoliberal paradigm is no longer the only game in town (Curran, Citation2017).

Challenges to maintaining effective ESPs in the MCs

In support of these theories, research has revealed that, unlike the extractive industry, the manufacturing industry has a twofold influence or impact on the environment: The input impact–receiving raw materials from the extractive and agricultural sectors–and the output impact–generating waste and disposing of trash as pollution (Adu et al., Citation2020; Citation2022; Bour et al., Citation2019). Environmental social scientists are thus challenged by these pressing concerns including global climate change to create awareness for stakeholder engagement leading to securing solutions for socioenvironmental problems (Pennington et al., Citation2021). The need to learn more about the obstacles manufacturing organizations have in adhering to environmental sustainability standards while promoting improved socioeconomic development is a research focus for now. Though there is enough scientific evidence that MCs have some measures in place for environmental sustainability (Agyabeng-Mensah et al., Citation2021; Cherrafi et al., Citation2017), literature seems to suggest that MCs must improve their ESPs; that is, practical steps to control production processes at the production sites must be taken. But this has not been easy coming. According to Bowen and Aragon-Correa (Citation2014), several assessments show ‘greenwashing’, which denotes that many businesses break numerous laws in addition to not adhering to their stated standards. For instance, if the leadership of the company is profit-centered then the uptake of profit-sapping ESPs and strategies will be compromised for the sake of maximizing profit. One of the exciting findings of a survey conducted by Collins and Kumral (Citation2020) was that many companies were not experiencing internal or external pressure to adopt effective environmental sustainability practices. Another discovery of that study was that the main drivers for the adoption of sustainability practices were personal values, beliefs, and commitments of management. Agyabeng-Mensah et al. (Citation2021) cited the profit maximization focus of companies as one of the factors that influence the implementation of environmental sustainability practices of companies. In their view, the laissez-faire theory of capitalism requires decision-makers to maximize the long-run profit of businesses. The findings of Agyabeng-Mensah et al. (Citation2021) show that financial performance is significantly impacted by green human capital. However, social performance and green competitiveness are not significantly impacted by green human capital. Additionally, social performance, financial performance, and green competitiveness are all markedly enhanced by green logistics techniques.

Predictors of uptake of ESPs by MCs

The link between green human capital and financial, social, and competitive performance is mediated by green logistical techniques. Green human capital therefore plays a role in the effective use of green logistics techniques, which strengthens green competitiveness and improves social and financial outcomes. Further studies demonstrate that Lean, Six Sigma, and green techniques improve an organization’s economic, social, and environmental sustainability performance (Cherrafi et al., Citation2017). Nonetheless, it appears from their data that organizations have encountered difficulties integrating and implementing them (Agyabeng-Mensah et al., Citation2021; Cherrafi et al., Citation2017). As evidenced by their findings, the organizations were able to minimize energy and mass stream costs by 7–12% and cut resource usage from 20–40% on average thanks to the combination of Lean Six Sigma and Green. However, the factories should gradually integrate the Green and Lean Six Sigma framework, first evaluating their strengths and weaknesses, establishing priorities, and setting targets for effective adoption.

These are followed by several ‘whys’ about the difficulties MCs face in their pursuit of environmental sustainability that have not received enough attention from studies. According to Bour et al. (Citation2019), MCs as a legal requirement submit their environmental protection plan (EPP) or policy before being incorporated. It would seem reasonable that every manufacturing business will adhere to environmental sustainability standards in light of this obligation. Paradoxically, businesses that claimed to use ESPs at work failed the test when it came to their implementation (Bedu-Addo, Citation2022; Boatemaa Darko‐Mensah & Okereke, Citation2013; Ng et al., Citation2022). There is a social truth lacking, and scientific study is desperately needed to fill it in. There is a dearth of scientific research on the obstacles to Ghanaian MCs’ environmental sustainability practices, even though several studies have been conducted on how businesses adhere to the country’s environmental sustainability regulations (Moses et al., Citation2014). Other studies have shown that ESPs have boosted corporate development, competitiveness, and employment both directly and indirectly (Rayment et al., Citation2009). As per the authors’ findings, the European Commission (EU) has projected that the EU's eco-innovative product and technology portfolio in the areas of sustainable construction, renewable energy, bio-based products, and recycling could potentially generate over 2.4 million new jobs by 2020, with a total commercial value from €92 billion in 2006 to €259 billion in 2020, leading to the creation of more than 2.4 million new jobs.

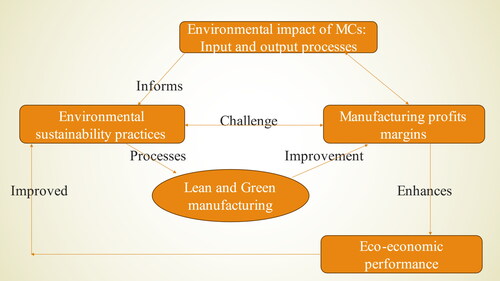

No matter the situation, the predictive validity of the relationship between MCs’ profit margin and ESPs is still under-explored. Therefore, this study sought to close this gap in the literature by examining profit-ESPs dynamics as to ‘why’ most MCs fall behind in implementing environmental sustainability strategies. More significantly, the majority of the studies on environmental sustainability or deterioration have focused on chemicals or pollutants, the relationship between green manufacturing and the financial position of MCs, and a few on socioeconomic implications for ESPs of MCs (Agyabeng-Mensah et al., Citation2021; Bour et al., Citation2019; Jum’a et al., Citation2021). None or little is known about how much profit is gained or lost when certain ESPs are embarked on by the MCs. gives a conceptual framework for profit as a predictor variable for environmental sustainability practices.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for profit as a predictor variable for environmental sustainability practices.

Consequential to this review are the hypotheses that:

H1: There is a significant relationship between ESPs and the economic performance of the MCs.

H2: There is a significant relationship between ESPs and the profit margins of the MCs

H3: There is a significant difference among ESPs as regards profit margins of the MCs

Methods

The study’s approach was centered on examining how environmental sustainability practices (ESPs) affected the expansion of Ghanaian manufacturing companies.Footnote1 The study focused on manufacturing firms, particularly those that the EPA assessed as having low environmental sustainability in 2012. These businesses were selected based on their main industries, which include the processing of wood, chemicals, agro-business, food and meat processing, oil processing, and drinks and beverages. Using Moser and Kalton’s sample size calculation technique, the sample size of 600 respondents from six chosen businesses was calculated, assuming a 60% agreement rate on the association between ESPs and corporate profit and aiming for a margin of error of 0.02. The classification was made at the suggestion of the EPA's public relations officer in Kumasi. The companies analyzed were selected from a list of 14 (graded red) companies listed with the EPA-Ghana for environmental evaluation in 2012 (Please see adopted from Bour et al. (Citation2019)Footnote2). It is worth noting that informed consent for participation in the study has been obtained from the individuals and corporate institutions concerned. This study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Department of Sociology and Social Work, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana.

Table 1. List of selected companies for the study.

The proportion of each stratum (each company) of the study population that made up the sample can be found in . The research used a two-stage approach of proportional stratified sampling and cluster sampling techniques to achieve representation throughout the various industrial sectors. A careful evaluation of the literature, surveys, key informant interviews, and, in certain situations, direct observations were all used in the data-gathering process. Reliability testing, data editing, coding, and statistical analysis using SPSS software were all part of the data analysis process. Inferential statistics like linear regression were the main emphasis to forecast the relationship between ESPs and corporate profit margins. The research sought to shed light on the relationship between Ghanaian manufacturing enterprises’ financial success and environmental sustainability measures.

Table 2. Sample size for each of the selected companies.

Demographics of the respondents

depicts the socio-demographics of the (4 non-response) respondents of the study, comprising 26% management, 54% senior staff, and 20% junior staff (see for the details). Other demographic data displayed in include sex, level of education, and years of service with the company.

Table 3. Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents.

Discussion and result

ESPs of MCs

is a descriptive statistical table depicting the various ESPs found to be operational in the MCs, even though some of them were found to be infrequent. By using the mean ranking method, it is realized that the companies engage in eight ESPs, of which three are major and predominant. They include the installation of facilities to reduce pollution, such as bio-digesters for treatment of liquid waste and kilns fueled by sawdust for drying wood (M = 4.5587, S = 2.10440). This is followed by traditional practices such as using chimneys, dustbins, and clean-up, with an M = 4.0973 and S = 0.95825. The use of fume-free machinery, such as LPG-powered vehicles, and energy conservation practices are also considered major practices, with a mean of 4.0218 and a standard deviation of 2.15793.

Table 4. The descriptive statistics of the ESPs.

The remaining five clusters of practices have relatively low means. For instance, environmental and waste management policies on reuse and recycling (M = 3.9849, S = 2.00624), inspection and monitoring of releases into the environment by external (EPA and ISO) and internal structures especially environmental department (M = 3.6980, SD = 0.96287), environmental auditing and disclosure of environmental performance (M = 3.3742, S = 2.10544) as well as environmental socialization and eco-award (M = 1.8003, S = 1.54226), all have relatively low means indicating that they were of low priority areas to the companies. It is observed that environmental socialization and eco-awards received the least attention as ESP in those companies. This aligns with the findings of Christmann (Citation2000), Cherrafi et al. (Citation2017), and Agyabeng-Mensah et al. (Citation2021) that when environmental issues became part of public opinion in the late 1980s, industries responded primarily by cleaning up their operations through pollution prevention and refining their products.

Profit-ESPs’ relationship

The regression analysis outcome indicates a relationship between ESPs and the profit the MC makes. shows the impact of a particular ESP on the profit of the MC.

Table 5. Regression coefficients of the predictor variable (ESPs).

The results of the regression analysis are summarised in and . However, the information in shows the magnitude of the relationship between the various ESPs and the profit margin of the MCs.

Table 6. Model summary of the effects of ESPs on the profit of the MCs.

The information in presents a model summary of the relationship between the ESPs and the profit margins of MCs as evidenced by regression analysis. From the summary model, the R square of 0.813 indicates that the independent variable accounts for approximately 81.3% of the changes in the dependent variable. In other words, the independent variable (ESPs) accounts for approximately 81.3% of the variations in the dependent variable (profit margin). Even after adjusting for errors, the independent variable accounted for approximately 65.7% of the variability in the dependent variable. depicts the observed correlations in terms of the regression coefficients of the predictor variables. It is vital to note that negative coefficients indicate that a 100% increase in the employment of that specific practice reduces the company’s profit margin by a percentage point equal to the coefficient multiplied by 100. The positive coefficient implied that increasing the use of that specific technique by 100% increased the profit margin by a percentage point equal to the coefficient multiplied by 100. shows that enterprises that use typical ESPs such as chimneys, garbage cans, and clean-ups are likely to raise their profit margin by 4.1%. The coefficient of 0.041, on the other hand, was not significant at 0.05 since the p-value was 0.352, which was more than 0.05. This means that there was a lot of variation among the scores, and the outcome might not be legitimate or dependable. It indicated that there were more significant variables or factors influencing the equation or circumstance and that the means used to determine the line of best fit were far distant from the scores that produced them. The alternative view is that the technique itself may not add to the company’s profit, but these traditional procedures require the use of less expensive resources meaning that a small increase in output is likely to boost profit. As a result, such an increase in profit margin might be attributed to such ESPs. Nonetheless, the cheap cost of engaging in such traditional behaviors and the public relations components in those practices have the potential to boost the company’s profit margin. This finding reinforces an earlier finding that environmental costs are significant and that enterprises engage in ESPs that are likely to improve or preserve their profit margins (Bour et al., Citation2023; García Alcaraz et al., Citation2022; Rehman et al., Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2020). No wonder it is one of the popular ESPs of MCs.

The Table also shows that the installation of state-of-the-art facilities such as bio-digesters for handling liquid waste and kilns for drying wood to prevent pollution will likely reduce profit margin by 6%. The regression coefficient of −0.060, which was significant at 0.01 with a p-value of 0.003, was used to infer this association. Similarly, the Hannover Chamber of Commerce discovered that materials for environmental sustainability initiatives currently account for 40% of manufacturing expenditures, as opposed to labor, which accounts for 23% of total costs (Amir et al., Citation2020; Johnstone, Citation2020). As a result, the prediction is more likely to be correct. This evidence demonstrated that the likelihood of losing 6% of the company’s earnings due to environmental sustainability efforts was considerable, and so management was more likely to cut corners to decrease that cost. This could explain why MCs failed to achieve EPA environmental sustainability guidelines because they did not want to lose 6% or more of their revenues.

In the case of the usage of fume-free machinery, such as LPG-powered and energy-saving machines, the regression analysis demonstrated that such a practice considerably reduces the company’s profit margins. Statistically, the research found that a 100% increase in the adoption of this method might reduce the company’s profit margin by 10.3%, which was significant at the 5% level. According to Rayment et al. (Citation2009), the cause for this state of affairs was the high cost of acquiring these machines, which subsequently increased the total cost of production. They also stated that it would be the cause of high unit prices of products, which would be unwelcome by buyers and hence diminish corporations’ profit margins.

The analysis also found that implementing environmental and waste management policies such as reuse and recycling would enhance profit margins by 2.1%, which was significant at the 1% level. An earlier study by Rayment et al. (Citation2009) found that having an environmental policy in place at a company keeps employees aware of their environmental tasks and responsibilities. This improves cost control, decreases occurrences that result in liability, conserves raw materials and energy, increases environmental impact monitoring, and improves process efficiency.

Given the benefits of having an environmental strategy, it is not surprising that this study revealed that having environmental and waste management policy boosts earnings by 2.1%. It has been demonstrated that environmental policies have directly and indirectly stimulated competitiveness, growth, and job creation in businesses (Rayment et al., Citation2009). According to these authors, the European Commission (EU) estimated that the total commercial value of eco-innovative products and technologies in sustainable construction, renewable energy, bio-based products, and recycling in the EU could increase from €92 billion in 2006 to €259 billion in 2020, resulting in the creation of more than 2.4 million new jobs. This thus confirms H1: There is a significant relationship between ESPs and the eco-economic performance of the MCs.

Last but not least ESPs for attaining environmental sustainability are environmental socialization through workshops, seminars, conferences, etc., and eco-awards tactics. It also found that such methods are expected to reduce the company’s earnings by 6.3%, which is significant at 5%. This could be explained by the costs associated with organizing such events. These outcomes confirm the H2: There is a significant relationship between ESPs and the profit margins of the MCs.

Conclusion

The study discovered that some ESPs have a favorable effect on profit margins, such as the adoption of environmental and waste management policies like reuse and recycling. This proves that environmental sustainability policies do have an impact on manufacturing enterprises’ financial performance and directly supports hypothesis H1. Different ESPs have different effects on profit margins, according to the report. For example, the adoption of state-of-the-art facilities like bio-digesters and energy-saving machinery may result in a large drop in profit margins, while traditional practices like the usage of chimneys and clean-ups may marginally boost profit margins. This validates H2, showing a clear correlation between particular ESPs and MCs’ profit margins. Regression analysis results support the study’s findings that different ESPs have differing effects on profit margins. It has been discovered that certain activities, like waste management and environmental regulations, increase profit margins, while other practices, such as using machinery that emits no fumes, are linked to lower profit margins. This demonstrates how important it is to take into account the variety of ESPs and how each affects profit margins differently, supporting H3. So, what now? In light of these findings, it is suggested that the Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology and Innovation in collaboration with the Environmental Protection Agency formulate policies and bills to be passed into law to compel MCs to allocate a substantive part of their budget for ESPs. At corporate management levels, since there is no incentive for employees to embrace and uphold the ESPs, we recommend the institution of an attractive eco-awards system for both departments and employees who strictly adhere to the finest ESPs. This will serve as motivation for employees to develop green consciousness and a habit to maintain the highest ESPs in and around the MC for ES. By so doing Ghana will be making progress toward achieving SDG 15 and promoting green manufacturing as well. Even if the study’s conclusion is trustworthy and legitimate, there is one small catch. This paper’s primary limitations are that it only looks at MCs in Ghana’s cities and that its conclusions might not hold up outside of the study’s confines. Furthermore, it excluded mining, commercial farms, and service firms that are regarded as some of Ghana’s worst polluters. Similar studies may thus be conducted in service companies and commercial farms in Ghana and beyond.

Author contributions

Kwame B. Bour, Kwaku Adu and Anthony Amoah conceptualized the research problem, developed the theory and performed the computations. Kwame B. Bour, Kwaku Adu, Anthony Amoah, Braimah Kassum, and Collins Gameli Hodoli, developed the model, the theoretical and computational frameworks, and analyzed the data. Patience A. K. Awua-Boateng proof read the manuscript and made suggestions for final work. All authors contributed to the design through to the writing of the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript.

Acknowledgment

No funding was received.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The identity of the six companies used must be protected at all costs. This may have dire consequences for them as authorities (e.g., EPA, Ghana Revenue Authority, etc.) may use it against them. Moreover, the companies indicated that their ethical principles do not permit such information to be shared with the public. It is for this reason that we could not use the full names of the companies used for this research but rather their abbreviations.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kwame B. Bour

Kwame B. Bour (Ph.D.) is a lecturer at the Department of General Studies, University of Environment and Sustainable Development (UESD) Somanya, Ghana. He obtained his Ph.D. in Sociology from KNUST, Kumasi, and his MPhil in Sociology from the University of Ghana. He has a B.A. (Sociology and Law) from KNUST, Kumasi. He also has certificates in introduction to epidemiology and project management from the University of Washington, USA, and a certificate in Theology and Pastoral studies from Pentecost University Ghana.

Kwaku Adu

Kwaku Adu (Ph.D.) is a lecturer at the Department of Applied Economics, School of Sustainable Development, University of Environment and Sustainable Development, Somanya, Ghana.

Anthony Amoah

Anthony Amoah (Ph.D.) serves as an Associate Professor and the Ag. Dean of the School of Sustainable Development at the University of Environment and Sustainable Development (UESD), Somanya, Ghana.

Braimah Kassum

Braimah Kassum (Ph.D) and Collins Gameli Hodoli (Ph.D.) are lecturers at the Department of Build Environment, School of Sustainable Development, University of Environment and Sustainable Development, Somanya, Ghana.

Collins Gameli Hodoli

Braimah Kassum (Ph.D) and Collins Gameli Hodoli (Ph.D.) are lecturers at the Department of Build Environment, School of Sustainable Development, University of Environment and Sustainable Development, Somanya, Ghana.

Patience A. K. Awua-Boateng

Patience A. K. Awua-Boateng is an Assistant lecturer at the Department of General Studies, University of Environment and Sustainable Development (UESD) Somanya, Ghana.

Notes

1 The same methodology was used in the paper below since they are all from the same project.

2 This study is actually part of a Ph.D. project that was carried out between 2018 and 2022, of which part was published in 2019. Contributions and reviews of the earlier publication by academics suggest that a separate publication on the aspect of predicting profit using environmental sustainability practices will be interesting and unique to appreciate. Hence, the processing of the current study for publication.

References

- Adu, I. K., Tetteh, J. D., Puthenkalam, J. J., & Antwi, K. E. (2020). Intensity analysis to link changes in land-use pattern in the Abuakwa North and South municipalities, Ghana, from 1986 to 2017. International Journal of Geological and Environmental Engineering, 14(8), 225–242.

- Adu, K., Ankomah Damoah, E., Bour, K. B., Oppong-Kusi, B., & Sackey, F. G. (2024). An economic valuation of the Bunso Eco-Park, Ghana: An application of travel cost method. Cogent Social Sciences, 10(1), 2341481. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2024.2341481

- Adu, K., Puthenkalam, J. J., & Kwaben, A. E. (2023). New framework for multidimensional environmental well-being for sustainable development. Journal of African Development, 24(1), 136–173. https://doi.org/10.5325/jafrideve.24.1.0136

- Adu, K., Puthenkalam, J. J., & Kwabena, A. E. (2022). Agricultural and extension education for sustainability approach. British Journal of Environmental Studies, 2(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.32996/bjes.2022.2.1.2

- Agyabeng-Mensah, Y., Tang, L., Afum, E., Baah, C., & Dacosta, E. (2021). Organisational identity and circular economy: are inter and intra organisational learning, lean management and zero waste practices worth pursuing? Sustainable Production and Consumption, 28, 648–662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.06.018

- Akuoko, K. O., & Bour, K. B. (2013). Effect of mining pollution on the people of Wassa West District of Ghana. ZENITH International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 3(2), 330–344.

- Amir, M., Rehman, S. A., & Khan, M. I. (2020). Mediating role of environmental management accounting and control system between top management commitment and environmental performance: A legitimacy theory. Journal of Management and Research, 7(1), 132–160. https://doi.org/10.29145/jmr/71/070106

- Barima, Y. S. S., Kouakou, A. T. M., Bamba, I., Sangne, Y. C., Godron, M., Andrieu, J., & Bogaert, J. (2016). Cocoa crops are destroying the forest reserves of the classified forest of Haut-Sassandra (Ivory Coast). Global Ecology and Conservation, 8, 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2016.08.009

- Bedu-Addo, K. (2022). Is the AKOBEN programme the panacea to gold mining related environmental degradation in Ghana? An integrated analysis of the AKOBEN programme. Heliyon, 8(5), e09428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09428

- Bjørnbet, M. M., Skaar, C., Fet, A. M., & Schulte, K. Ø. (2021). Circular economy in manufacturing companies: A review of case study literature. Journal of Cleaner Production, 294, 126268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126268

- Boatemaa Darko‐Mensah, A., & Okereke, C. (2013). Can environmental performance rating programmes succeed in Africa? An evaluation of Ghana’s AKOBEN project. Management of Environmental Quality, 24(5), 599–618. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEQ-01-2012-0003

- Bour, K. B., Adu, K., & Angmor, E. N. (2023). Green manufacturing for environmental sustainability: The hiccups for manufacturing companies in urban Ghana. Sustainable Environment, 9(1), 2274643. https://doi.org/10.1080/27658511.2023.2274643

- Bour, K. B., Asafo, A. J., & Kwarteng, B. O. (2019). Study on the effects of sustainability practices on the growth of manufacturing companies in urban Ghana. Heliyon, 5(6), e01903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01903

- Bour, K. B., Mensah, H. K., Asafo, A. J., & Dapaah, J. M. (2019). Socio-economic performance of manufacturing companies in Urban Ghana. European Journal of Business and Management, 11(15), 64–74.

- Bowen, K., & Aragon-Correa, J. A. (2014). Greenwashing in corporate environmentalism research and practice: The importance of what we say and do. Organization & Environment, 27(2), 107–112.

- Brechin, S. R., & Lee, S. (2023). Will democracy survive climate change? Sociological Forum, 38(4), 1382–1392. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12957

- Brulle, R. J., & Roberts, J. T. (2017). Climate misinformation campaigns and public sociology. Contexts, 16(1), 78–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536504217696081

- Carter, N. (2018). The politics of the environment: Ideas, activism, policy. Cambridge University Press.

- Chandio, A. A., Akram, W., Sargani, G. R., Twumasi, M. A., & Ahmad, F. (2022). Assessing the impacts of meteorological factors on soybean production in China: What role can agricultural subsidy play? Ecological Informatics, 71, 101778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2022.101778

- Cherrafi, A., Elfezazi, S., Govindan, K., Garza-Reyes, J. A., Benhida, K., & Mokhlis, A. (2017). A framework for the integration of Green and Lean Six Sigma for superior sustainability performance. International Journal of Production Research, 55(15), 4481–4515. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2016.1266406

- Christmann, P. (2000). Effects of “best practices” of environmental management on cost advantage: The role of complementary assets. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 663–680. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556360

- Collins, B., & Kumral, M. (2020). Environmental sustainability, decision-making, and management for mineral development in the Canadian Arctic. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 27(4), 297–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2019.1684397

- Curran, D. (2017). The treadmill of production and the positional economy of consumption. Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne de Sociologie, 54(1), 28–47.

- Draghici, A. (2019). Education for sustainable development. MATEC Web of Conferences, 290, 13004. https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201929013004

- García Alcaraz, J. L., Díaz Reza, J. R., Arredondo Soto, K. C., Hernández Escobedo, G., Happonen, A., Puig I Vidal, R., & Jiménez Macías, E. (2022). Effect of green supply chain management practices on environmental performance: Case of Mexican manufacturing companies. Mathematics, 10(11), 1877. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10111877

- Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons: the population problem has no technical solution; it requires a fundamental extension in morality. Science, 162(3859), 1243–1248.

- Johnstone, L. (2020). A systematic analysis of environmental management systems in SMEs: Possible research directions from a management accounting and control stance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 244, 118802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118802

- Jum’a, L., Zimon, D., & Ikram, M. (2021). A relationship between supply chain practices, environmental sustainability and financial performance: evidence from manufacturing companies in Jordan. Sustainability, 13(4), 2152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042152

- Khan, H., Khan, I., & BiBi, R. (2022). The role of innovations and renewable energy consumption in reducing environmental degradation in OECD countries: An investigation for Innovation Claudia Curve. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(29), 43800–43813. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-18912-w

- Khan, S. A. R., Yu, Z., & Farooq, K. (2023). Green capabilities, green purchasing, and triple bottom line performance: Leading toward environmental sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(4), 2022–2034. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3234

- Kumar, V., Sezersan, I., Garza-Reyes, J. A., Gonzalez, E. D., & Al-Shboul, M. d A. (2019). Circular economy in the manufacturing sector: Benefits, opportunities and barriers. Management Decision, 57(4), 1067–1086. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-09-2018-1070

- Kwakwa, P. A., Adjei-Mantey, K., & Adusah-Poku, F. (2022). The effect of transport services and ICTs on carbon dioxide emissions in South Africa. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(4), 10457–10468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-22863-7

- Le Quéré, C., Andrew, R. M., Canadell, J. G., Sitch, S., Korsbakken, J. I., Peters, G. P., Manning, A. C., Boden, T. A., Tans, P. P., Houghton, R. A., Keeling, R. F., Alin, S., Andrews, O. D., Anthoni, P., Barbero, L., Bopp, L., Chevallier, F., Chini, L. P., Ciais, P., … Zaehle, S. (2016). Global carbon budget 2016. Earth System Science Data, 8(2), 605–649. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-8-605-2016

- Lee, K., Azmi, N., Hanaysha, J., Alzoubi, H., & Alshurideh, M. (2022). The effect of digital supply chain on organizational performance: An empirical study in Malaysia manufacturing industry. Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 10(2), 495–510. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.uscm.2021.12.002

- Lundberg, P., Vainio, A., Ojala, A., & Arponen, A. (2019). Materialism, awareness of environmental consequences and environmental philanthropic behaviour among potential donors. Environmental Values, 28(6), 741–762.

- Mesti, G. (2013). Ghana national climate change policy. Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology and Innovation.

- Morgan, S., Pfaff, A., & Wolfersberger, J. (2022). Environmental Policies Benefit Economic Development: Implications of Economic Geography. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 14, 427–446.

- Moses, K., Alhassan, F., & Sakara, A. (2014). The effects of manufacturing industry on the environment: Case of Atonsu-KaaseAhinsan in the Ashante Region of Ghana. ADRRI Journal of Physical and Natural Sciences, 1(1), 14–28.

- Ng, T. C., Lau, S. Y., Ghobakhloo, M., Fathi, M., & Liang, M. S. (2022). The application of industry 4.0 technological constituents for sustainable manufacturing: A content-centric review. Sustainability, 14(7), 4327. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074327

- Pennington, D., Vincent, S., Gosselin, D., & Thompson, K. (2021). Learning across disciplines in socio-environmental problem framing. Socio-Environmental Systems Modelling, 3, 17895. https://doi.org/10.18174/sesmo.2021a17895

- Rehman, S. U., Kraus, S., Shah, S. A., Khanin, D., & Mahto, R. V. (2021). Analyzing the relationship between green innovation and environmental performance in large manufacturing firms. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 163, 120481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120481

- Schnaiberg, A. (2012). Sustainable development and the treadmill of production. In Politics of sustainable development (pp. 83–98). Routledge.

- Seini, H. A. (2022). The Role of Environmental Protection Agency Under Ghana’s Fourth Republic. In Democratic Governance, Law, and Development in Africa: Pragmatism, Experiments, and Prospects (pp. 669–694). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Songsore, J. (2004). Urbanization and health in Africa: Exploring the interconnections between poverty, inequality, and the burden of disease. Ghana Universities Press.

- Stuart, D., Petersen, B., & Gunderson, R. (2023). Articulating system change to effectively and justly address the climate crisis. Globalizations, 20(3), 432–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2022.2106040

- Wang, H., Khan, M. A. S., Anwar, F., Shahzad, F., Adu, D., & Murad, M. (2020). Green innovation practices and its impacts on environmental and organizational performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 553625. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.553625

- World Bank. (2020). Ghana country environmental analysis. World Bank.