Jane Collins in conversation with Asiimwe Deborah Kawe, Artistic Director of the Kampala International Theatre Festival (KITF)

Asiimwe Deborah Kawe is an award-winning playwright, producer, and performer and, currently, the Producing Artistic Director of Tebere Arts Foundation and Artistic Director of the Kampala International Theatre Festival. In June 2023 she was a keynote speaker at the Prague Quadrennial of Performance Design and Space (PQ23).Footnote1 Watching Asiimwe’s presentation triggered memories of my own time working in Uganda in the late 1980s and 1990s, with the internationally renowned playwright, actress and academic the late Rose Mbowa.Footnote2 At that time Uganda was still recovering from the aftershocks of the bloody and murderous regimes of Idi Amin and Milton Obote that followed the post-independence political turmoil there, when many prominent theatre artists were forced into exile, and some were murdered. Theatrical performance in Uganda has always been at the centre of cultural and social life as a potent religious, educational, and political force, in spite of the suggestion from western critics ‘that Uganda, along with all other African countries, lacked any form of real theatre until the late the nineteenth century’ ( Kaahwa Citation2004, 82). This is because, in the words of Mbowa, theatre in their understanding consisted of ‘formal scripted theatre performed on a proscenium arch stage, an artistic form that was introduced [in Uganda] by the colonial educators and missionaries’ (1999, 227 cited in Kaahwa Citation2004, 82).

Before her untimely death in 1999, Rose was head of the music, dance, and drama department at Makerere University,Footnote3 where she was at the forefront of challenging these tired and reductive assumptions about theatre in Africa. During her tenure she established regenerative programmes of theatre for development, merging traditional epic storytelling with western theatre in education techniques; she set up programmes in production arts and encouraged a generation of young Ugandans to find their own voice in a culture still dominated by the colonial mindset of the well-made play. One of those students, it transpires, was Asiimwe, who was taught by Rose in her first year at university and, in one of our first email exchanges, told me ‘She was very instrumental in my life and in shaping my artistic journey’.Footnote4 With Rose as a connecting thread, I was really excited to learn more about the history of the festival, the current theatre scene in Uganda and the extent to which design and scenography featured in the programme in its tenth edition in November 2023, which of course was still in the planning stages when Asiimwe gave her keynote in June of that year. A report from Kampala seemed the perfect vehicle to continue the conversation that started at PQ23.

The Kampala International Theatre Festival celebrated its 10th birthday in November 2023, and you have been associated with it from the beginning. Can you tell me a little bit about its inception? How did it come about?

The Kampala International Theatre Festival was born out of the Sundance Institute theatre programme East Africa. The Sundance Institute is an arts organisation founded by the actor/director Robert Redford in the USA. It is now mainly known for film, but they used to have a theatre programme. In fact the organisation started based on storytelling and for many years, for over 20 years I think, they used to run a theatre lab in America.Footnote5 So in the early 2000s the artistic director of the Sundance Institute theatre programme, Philip Himberg, who had been running the programme for over 10 years, became curious about what else was happening in theatre in the parts of the world he knew nothing about, particularly Eastern Europe and East Africa. So, with the support of the Sundance Institute, Ford Foundation and Center for International Theatre Development he made a trip to East Africa, including Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. In Uganda he came to Kampala, and I was a student at Makerere University at that time doing an internship at the National Theatre.Footnote6 I remember taking him round the National Theatre and other theatre venues, and as we talked, he was very interested to know how and where people were developing new work in Uganda. One of the things I explained to him was the lack of space for development. People just sit in their rooms, write their plays, and put them on stage without a process of feedback and rewriting. I did mention to him that the British Council had been running a programme in East Africa to support theatre, specifically playwriting.

I remember that programme; in the 1990s it was run in conjunction with new writing theatres like the Royal Court in London.

Yes, but by the early 2000s that programme was coming to an end. And one of the questions I had as a student was, ‘I’m just finishing university, I’m interested in theatre, I’m not sure if I want to be a playwright but where is the space to enable me to develop my craft?’ Well, after his visit he went back to the US and set up a programme to invite different theatre makers, whether established or emerging like myself, from East Africa, to come to Utah to the Sundance Theatre Lab. He wanted to know if what they were doing had any kind of resonance for us. I remember being completely blown away by the luxury of people having the time and space to develop new work. I thought to myself, could this ever happen in our part of the world? And towards the end of the lab Philip and I went for a walk, and went up the Sundance Mountain in chairlifts, and he asked me what I thought of the programme, and I said I really wish something like this could happen in East Africa.

Let’s fast forward, because you then got a scholarship to study in the United States and you and Philip Himberg kept in touch, is that right?

Yes, he kept in touch with me and other theatre artists from East Africa, and by the time I finished my course at the California Institute of the Arts, the Sundance Institute had set up a board of East African artists to begin to talk about whether it was indeed possible to set up a lab in East Africa. Then they put out a call for people who might be interested in working on this project. I applied and was lucky enough to get the job. So for several years I divided my time between New York and a number of East African countries, because although Philip had initially only visited Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania, by then there was an expansion to other East African countries, Rwanda for example, and Burundi and Ethiopia. So when we started the lab, we wanted to set up connections between these countries.

Do you remember the date the lab started?

It was from 9th to 29th July 2010. Take a look at the link below.Footnote7 I was so excited to land on it!

Where was the lab based – or did it move around?

The lab was initially based at Manda Island in Kenya, off the coast of Indian Ocean. But we also ran a stage directors’ lab in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. As the initiative was beginning to wind up, there was insecurity in Kenya, so by then we had moved the theatre lab from Manda to Zanzibar.

How popular was the initiative with theatre artists in those countries?

One of things the Sundance Institute East Africa staff did every year was to ask the artists themselves if what we were doing was supporting their development as theatre makers. Was it still interesting to them? Whether it still had relevance. I travelled to various countries and had meetings with artists, and I asked them what in your opinion would be the next great phase of this project? And all of them said, we need a platform to showcase our work. And that was how the Kampala International Festival started.

Why did you choose to site the festival in Uganda?

I was familiar with Uganda and knew the theatre landscape quite well so it made more sense that the theatre festival should happen here. I was also aware that there was no theatre festival here at the time, the theatre festivals that had started in Uganda had never gone beyond their second or third birthday, so my purpose was to ensure that this festival had a long life. Initially we wanted it to be only for East Africa artists but after the first edition it was very clear to us that East African theatre artists were very insular, and it was important for them to be exposed to work from elsewhere on the continent of Africa and beyond. So, in 2015 we invited applications from all over the world. It was an open submission process, people saw the call and applied. However during the selection process we were always careful to maintain a balance, promoting work by East African artists first and foremost, and then from across the African continent and only after that we invited productions from elsewhere.

When you gave your keynote at PQ23 you were preparing for the festival in November. What were some of the highlights of the festival for you in 2023?

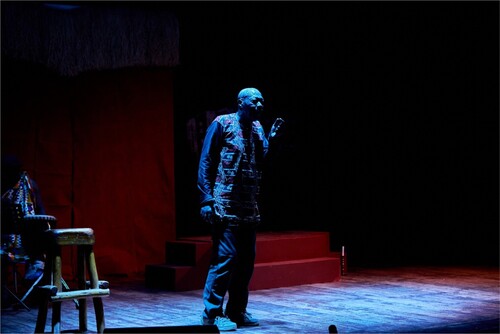

Last year was very special. We were turning 10 years old, and this was a landmark. For a festival that relies solely on donor funding, to survive this long is amazing. In fact, it’s a miracle. So, to mark the event we wanted to invite someone who was working in theatre when it was thriving in this country as an art form, but who was also familiar with what is happening today. So we invited the playwright George Bwanika Seremba.Footnote8 Seremba fled Uganda in 1980 after surviving execution. This was after the turmoil that followed the departure of Idi Amin in 1979 and just at the point when we thought we were going to have a free and fair democratic election. Seremba was a political activist and anti-Milton Obote. He was arrested, tortured, and taken to Namanve forest outside Kampala and shot. But he survived and with the help of local villagers and then his friends eventually managed to flee the country. He is now living in Canada and in fact he divides his time between Stuttgart in Germany and Toronto. We invited him to perform his autobiographical play, Come Good Rain,Footnote9 which is about his experiences but is also about the political history of this country ().

Ugandan theatre is tragically intertwined with the political history of the country, is it not?

Yes, it is. Byron Kawadwa and Robert Serumaga were both murdered by the authorities for their political activism.Footnote10 But miraculously Seremba survived, and he performed his play, which he has toured all over the world, in Uganda for the first time last year, at the festival. It was an extraordinary experience, particularly for the younger generation, to be presented with living history like that.

The festival is based in Kampala, but what about beyond the capital? Do you solicit works from the regions and how do you deal with the multiplicity of languages spoken across the country?

Plays come from everywhere across the country, but the majority of the plays in the festival are performed in English, or predominantly in English. However, we have a separate organisation associated with the festival called the Tebere Arts FoundationFootnote11 and we have several programmes for emerging artists to encourage them to write in the language they feel most comfortable in. So far, some of the students we work with have been writing in Luganda,Footnote12 but no students so far have worked in other languages like AcholiFootnote13 or Runyankore,Footnote14 for instance, or any other of the many ethnic languages spoken in Uganda. However, last year we had a playwriting residency, which is another programme we run, and the writer in residence was mixing languages, so her script had English, Kiswahili,Footnote15 Runyankore, Kinyarwanda,Footnote16 and Luganda. More and more plays are beginning to mix languages, but we have never had a performance at the festival totally in an indigenous language.

Do you see that as a loss?

I think it is. Performance and language are inextricably linked. Language informs the philosophy of a writer and works through the body of the performer, and much is lost when someone is trying to tell an indigenous story in a language which is foreign to them because there are things that are untranslatable. So we are interested to go into communities that are practising indigenous art forms that would make no sense if a European structure was imposed on them, to encourage and support them. There is still a big debate about this in Uganda, and the play that opened the festival in 2022 by Peter Kagayi Ngobi, for my negativity, was focused on speaking in the ‘vernacular’.Footnote17 Even today, in some Ugandan schools speaking in your mother tongue is regarded as an offence – even today in some schools children are punished for this. That is one of the legacies of colonialism. That is why, for the future, it is important to look towards some kind of hybridity in terms of language and in terms of form in theatre ( and ).

And will this hybridity incorporate the complex visuality of these indigenous forms?

Yes indeed. And there is a precedent for this. Robert Serumaga, political activist, theatre director and playwright who I mentioned earlier. The language he was trying to develop with his company, Abafumi Theatre, was basically visual theatre, with no text, that drew from all the diverse cultures of Uganda. The company was made up of people from different regions who brought their indigenous art forms into the mix and told their stories with their bodies. So on the one level he was developing a hybrid form of Ugandan performance but, on another level, given the terrible political climate at that time, he was engaging in a veiled form of political activism. The messages were conveyed through costume, gesture, and movement. No words. So it was very difficult for the those in power to pin them down as anti-government. It was an aesthetic mechanism to protect the performers and himself, but he was also passionate about developing a specific performance language that integrated indigenous and imported European forms.

So, if I’m understanding you correctly, you are saying it’s important to be reaching out to these various vernacular forms but you’re not looking for some kind of authenticity or ontological purity. As the traditional is already imbued with the modern. It’s not about conservation. Your interventions are more dynamic than that.

Yes, it’s about putting these different forms in conversation. We don’t embody the purest forms of indigenous performance anymore, that’s not who we are. And it’s important that we recognise that, and then we can start to define who we are by embracing all our different selves.

Having established the history of the festival, and briefly glimpsed at some of the key figures in Ugandan theatre history, as well as the richness and diversity of all the various strands of performance happening in Uganda currently, I'd like to talk specifically about design and scenography. You focus a lot on oral culture and storytelling, and it’s interesting that you said in your PQ presentation that design/scenography is the last thing you think about when staging a performance. But actually most of the work you showed demonstrated a very sophisticated understanding of scenography.

I hear you. I completely understand when you say that the images I presented during my keynote came across as having a strong awareness of scenographic composition. And this is what we also see, usually after the performance. But in the moment of making these choices we are not consciously thinking about scenographic effects. We are not selecting this or that as a conscious aesthetic choice, we are just utilising what is there. If we had a number of black box theatres available to us, or a variety of proscenium stages, we would not be making these choices. If we had these venues at our disposal, when incoming companies say we need a black box or a proscenium stage with a trapdoor, we would say fine we can provide. But, in the absence of those things, we really have to think outside of what is given to us as a brief, to create an experience the artists and audience [are] going to truly appreciate. So, what we do is not an artistic exploration but a response to needs we must meet. We have to think how we can create something for visiting companies that will meet their artistic needs but won’t be a replica of what they have done elsewhere. So the choices are purely accidental, they are a pragmatic response to the problems posed by the incoming artists. They are made by myself and my team, none of whom have any training in scenography. So while I appreciate what you are saying, that is our reality, that is our truth. What we’re trying to do is make the best of what we have, what is around, what is available in terms of space and materials.

So while there has been investment in writing for the stage, what you’re saying is there hasn’t been the same investment in studying or understanding the way plays work in performance, the dynamics between all the elements that make up a performance event.

Exactly, that is why it is so important for our students and young theatre artists to work with experienced designers and scenographers who work in different environments. This will help them to understand that we can make things happen with what we have here, we just need to think about space and materials differently. As it is, we have to work very fast and creatively when we receive a submission that comes across as tech heavy, that requires things that we don’t have, like the kind of lighting or sound we can’t produce. We have to think what is within our means, within our environment, that we can utilise to create something that is going to come across effectively and as a gift to the artists.

Do you think that the festival, and the exposure it offers to different configurations of stage space and materials, is having an impact on the way young theatre makers think about performance? As they experience these aspects of production firsthand and begin to understand their powerful effect on audiences, do you think they will start to build this into the writing processes and become less dependent solely on words to express their ideas?

Yes. Absolutely. Recently, I was teaching a workshop on directing, and it was interesting that the students were very keen that our organisation should set up a programme where we bring in an expert to guide them and give them the tools to create and direct a show with no text. What are the things they have to think about visually, not just in terms of the actor’s body but also in terms of the use of space and materials? And I was delighted to hear them make this request, because clearly it indicates that they are thinking about telling stories in different ways. I believe the students that have gone through our programme and some of those at Makerere are showing an interest in moving beyond the word.

Do you think we might see design and scenography courses offered at Makerere in the future?

At the moment in Makerere they have separated the courses into drama, music, and dance. The music department is focused on music, and in dance they study different dance forms and in drama they study plays, mainly as texts. When I was a student there, they were all integrated which I believe better reflects the nature of performance in Uganda. I think this focus on specialisation will make it more difficult to introduce scenography into the curriculum, because this segregation works against the holistic and dynamic nature of scenography.

So you see the inseparability of the physical, visual, vocal, sonic and the material as integral to indigenous performance in Uganda. And I assume everything was imbued with symbolic meaning. Do you think this current emphasis on the written word in Ugandan theatre is in part a legacy of colonialism? Is it an aspect of a broader colonial cultural hegemony that promulgates the transmission of ideas and values across the continent of Africa as predominantly oral? Because that has always seemed to me to be a rather reductive way of describing cultural forms that, as you say, are far more multidimensional and nuanced. I’m not saying that oral culture is not an integral part of tradition, just [that] it’s not the full story.

It definitely isn’t the full story. And in fact what you are saying reminds me of a TED Talk by the Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie called ‘The Danger of a Single Story.’Footnote18 That is the problem with so much that is written and spoken about the African continent, we only get one story. I think this emphasis on the oral comes from a fear of the visual and the power of images. Many of the missionaries tried to stamp out what they saw as idolatry and the work of the devil. It’s interesting because West Africa is not like that, this is particularly prevalent in East African countries. Maybe the French colonists were more open than the English and Germans.

More Catholic and less iconophobic perhaps.

Certainly. And young theatre makers in Uganda are really beginning to think more about how they can draw on that heritage and use it not only to talk about the present, without glossing over the problems posed by the current political situation, but also to look to the future.

There is a strong movement towards Africanisation in fashion; is that happening in theatre?

I really like the fact that you talk about fashion. Because Africanisation in fashion is a combination of many things. Western influences, certainly, but also drawing on the way indigenous people used to think about their bodies. But it is not trying to recreate that, it’s seeking ways to embody all of the things that we are now. So yes, that is happening in theatre. I think the direction things are moving is very exciting.

What do you think young theatre artists in Uganda, potential scenographers, would have made of PQ23?

I think they would have been fascinated. Most of all I think they would have been fascinated by the technology, so much detail in terms of the technology used. I think they would have questions about how much of what they saw could be achieved in their world. ‘That looks great but how would we do it? How else could it be done?’ I think many of the designs have European stages in mind. Young theatre artists in Uganda are also very climate-aware and environmentally conscious, and I think they would have questions about some of the materials used. They would be asking ‘What are the environmental consequences of what I’m looking at?’ They would have been very conscious of waste and cost, as well as access to resources. We have to do so much with very little.

Do you envisage work moving out of building-based theatres and more site-specific work in the future? Performance interventions into some of the old factories around Kampala, for instance, or within the colonial buildings themselves in the centre?

We have to be aware of our current political landscape, that is a major prohibitive factor, otherwise we would be doing more of this kind of work. For example, during the pandemic we made radio drama. Our internet connections are not great, and we were aware that audiences would not be able to watch performances online without interruption, so we ran programmes where we encouraged people to write for the ear and we ran audio courses for students. So at the festival in 2022, and last year, we created an audio installation, and this had to be cleared by the authorities. But people came and listened to stories through headphones. Now we are interested in taking work like this into public spaces, in matatusFootnote19 for instance and on other forms of public transportation. Recently I was talking about this with a colleague in Germany, and he was suggesting maybe we could take the headphones out into the streets. He had this idea the artists could differentiate themselves by wearing different-coloured tunics, green, blue, or red depending on what channel they are listening to through the wireless headphones, because each channel has a different kind of story. And I got excited by this, and I wondered, if we had twenty artists, established artists, and emerging artists, and we each have headsets and we shared the stories with the public, what would happen? Well I know what would happen, the authorities would come, and we would be stopped. The problem being of course we might get permission from the police but another arm of security, unaware that we have permission from the police, would come and stop us. So you see the thought and desire is there, but we have to consider what are the consequences. But we are ever hopeful. At the moment, one of our former playwrights in residence is working on a script with a visual artist, and they want to stage this in a public space near the train station. They are going to try to do a performance there and we will wait to see how that works out. Maybe we can get some ideas for how we might proceed in the future. But at the moment we are thinking buses and matatus might be safer than going into physical buildings or open public spaces.

I wish you luck negotiating that.

We will find a way.

In the face of such difficult political circumstances it is wonderful to hear so much positivity about the future of theatre in Uganda. Thank you so much, Asiimwe, for your time.

Notes

2 Rose Mbowa (1943–1999) was a Ugandan writer, actress, academic and feminist. She was a professor of theatre arts and drama at Makerere University. Her play Mother Uganda and her Children was first performed in 1987 and has since been performed internationally, its success signifying a growing local and international interest in and respect for East African theatre. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rose_Mbowa, accessed 22 March 2023. See also https://www.theguardian.com/news/1999/mar/15/guardianobituaries1, accessed 22 March 2023.

3 Makerere University in Kampala was founded as a technical school in 1922. Formerly known as the University of East Africa, it is the oldest and largest university in Uganda, having been granted its current name and status in 1970. The Department of Performing Arts (music, dance, drama and film) was established in 1971.

4 Email exchange between Asiimwe Deborah Kawa and the author June 2023.

5 The Utah Playwrights Conference formally became the Sundance Playwrights Laboratory in 1984.

6 The National Theatre of Uganda was officially opened in 1959.

8 George Bwanika Seremba (1958–), playwright, actor and activist, was born in the city of Kampala.

9 Come Good Rain was first published in 1993 and has toured internationally.

10 Byron Kawadwa of the Kampala City Players and Robert Serumaga and his Abafumi Theare Company were celebrated playwrights and directors in the late 1960s and 1970s in Uganda. Kawadwa was murdered by the forces of Idi Amin in 1977 and Serumaga died in Nairobi in 1980 in exile from President Milton Obote’s regime. The circumstances surrounding his death are unclear.

12 Luganda is a Bantu language spoken by the Baganda people who live in the Buganda region, which includes the capital Kampala.

13 Acholi is a dialect spoken in northern Uganda.

14 Runyankole is a Bantu language spoken by around two and a half million people in south-west Uganda.

15 Kiswahili or Swahili is a Bantu language, spoken on the east coast of Africa. It is heavily influenced by Arabic as a result of Arab trade with the coastal peoples over centuries. It spread to Uganda in the early nineteenth century, being the language of the Arab ivory and slave caravans as they penetrated inland.

16 Kinyarwanda is a Bantu language spoken by c. 7 million people, mainly in Rwanda, but also spoken in Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Burundi.

17 Peter Kagayi Ngobi is a poet, author and performer born in Jinja, Uganda. In 2022 his controversial play about language opened the Kampala International Theatre Festival. That same year the festival almost had to be cancelled as, in the week it was due to start, the organisers were ordered to acquire permits from the Media Council of Uganda for all the works to be shown, including play readings and works in progress. The permits were granted at the last minute and the festival was allowed to go ahead.

19 Privately owned minibuses used as shared taxis.