ABSTRACT

The Russian Federation is the regional focal attraction point for labor from former Soviet Union (fSU) countries. It occupies one of the top five places in the world on number of labor migrants (about 9-10 mln. people) (WB 2017). The Majority (about 90%) are from fSU countries (MVD 2017). The free visa regime within the post-Soviet space is accompanied by difficulties in obtaining legal registration and work permits in Russia that turns many migrants into the situation of illegality. Russia has done a lot in terms of legal provisions to combat illegal migration and human trafficking by signing the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, and two Palermo Protocols against Trafficking in Persons and against the Smuggling of Migrants in 2004 and has made a lot of amendments to the Russian Criminal Code. In spite of all these efforts, the real situation with combating human trafficking is problematic. Russia has been an origin, transit, and destination country for men, women and children trafficked for labor and sexual exploitation to and from numerous countries mostly neighboring. How does Russian migration policy, particularly the propiska (registration system), create vulnerabilities for labor trafficking? An Inconsistent migration policy and it’s implementation in Russia produce roots for constant violation of migrants’ rights by local government administrations, employers, and by law enforcement bodies, creating irregular migrants vulnerable to human trafficking. This analysis shows how national anti-trafficking laws intersect with other domestic laws, including migration policies, and create new vulnerabilities for trafficking.

The severity of Russian laws is softened by the lack of implementation

Peter ViazemskiFootnote1 in his dairy (1852)

Twenty years have passed since the enactment of the Palermo Protocol in 2000. In the intervening years, many countries have adopted the Protocol. Russia is one of the signatories as well. However, many shortcomings still exist in the national implementation of the Palermo Protocol. This analysis shows how national anti-trafficking laws intersect with other domestic laws, including migration policies, and create new vulnerabilities for trafficking. The Russian case shows that more attention needs to be placed on the synergies (or lack thereof) between national anti-trafficking laws and other kinds of domestic policies.

Russian Criminal Law Vs. The Palermo Protocol

Russia is an origin, transit, and destination country for trafficking of men, women, and children. The number of victims is estimated to range from 0.6 to 1.5 million (Pravda, Citation2017; Ryazantsev, Citation2015; TIP, Citation2019). In 2000, Russia signed two treaties and ratified both in 2004: (1) the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, including the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress, and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children, also known as the Palermo Protocol, and (2) the Protocol against Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea, and Air. In 2004, two anti-trafficking articles, namely 127.1 (Human Trafficking) and 127.2 (Use of Slave Labor), were introduced into the Russian Criminal Code (CC) by the Federal law 162-FZ3. Russian legislation does not include a definition of a “trafficking victim.” Instead, the Russian definition of trafficking focuses mainly on the trafficking process and types of exploitation; the focus on force, fraud, and coercion does not figure in the Russian definition (Voinikov, Citation2013, p. 2).Footnote2

Between 2003 and 2012, numerous additions were made to the anti-trafficking law; 18 additional articles, covering sex and trafficking-related crimes, have been included in the Russian Criminal Code. They range from distribution and production of pornographic materials to forgery and anything in between. According to Article 52 of the Russian Constitution, the rights of crime victims are protected by different laws. In reality, however, the state mechanism works poorly: there is no funding for victim protection and both victims and witnesses often do not want to testify in the court of law, fearing revenge by their perpetrators. Unsurprisingly, since 2013, Russia continues to be placed in Tier 3 of the U.S. Trafficking in Persons (TIP) report (TIP, Citation2013, Citation2019).

Against this backdrop, this article analyzed one critical, yet often under-appreciated, element of Russian anti-trafficking efforts: How does Russian migration policy, particularly the propiska (‘registration’ system), create vulnerabilities for labor trafficking? To answer this question, I examine the nexus of Russian migration and anti-trafficking policies since 2000 to the present. The first two sections of this article present the situation of human trafficking in Russia, the people at risk of exploitation, and existing statistical data. The following sections analyze the development of migration regulation in the post-Soviet era and how this resulted in vulnerabilities for labor trafficking. I conclude by proposing ways for Russia to mitigate these risks and strengthen its national anti-trafficking laws and adherence to the Palermo Protocol.

Trafficking in Human Beings in Russia

To understand the nature and evolution of anti-trafficking efforts in Russia, one needs to understand the characteristics of international migration after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the unique sociopolitical and economic contexts, the intricacies of Russian migration policy, and changes in the Russian Criminal Code since the adoption of the Palermo Protocol. After the dissolution of USSR, Russia became the regional focal point for repatriation and labor migration, mainly from the former Soviet Union (fSU). According to the World Bank (Citation2016), Russia currently ranks fifth in the world in terms of the scale of labor migration (approximately 9–10 million people) and according to information from Ministry of Interior (MVD), about 2 million people are with irregular status (RIA, Citation2018). The existing mobility control system, including remnants of the Soviet systems such as propiska,Footnote3 has left many international migrants, especially irregular migrants, at risk for trafficking. Ironically, the free visa regime within the post-Soviet space is accompanied by difficulties in obtaining legal registration and work permits (Tyuryukanova, Citation2006).

Russian migration policy often makes the shadow economy more attractive to both employers and employees by decreasing costs and time associated with following endless bureaucratic procedures and regulations. Migration scholars indicate that the shadow economy in Russia “constitutes about 25% of GDP on average but it increases to 40% for small businesses, where labor exploitation is much more widespread, and up to 60% in particular regions and economic sectors“ (Aronowitz, Theuermann, Tyurykanova, OCSE, Citation2010, p. 26). Experts of the Public Chamber in the Duma (Russian Parliament) argued that one in five labor migrants in Russia is exploited (OPRF, Citation2014). This shadow economy facilitates human trafficking. Another contributing factor to trafficking is the vastness of the country: Russia spans 11 time zones. Trafficked victims are usually removed from their friends or relatives (Buckley, Citation2018); in remote areas or national republics with unfamiliar languages and suspicion toward outsiders, the chance is slim of a migrant returning to ‘normal’ life.

Academic Research and Statistics on Human Trafficking in Russia

There is considerable literature on human trafficking in Russia. The first studies considered trafficking for sexual exploitation (e.g. IOM, Citation2002) and the signing of the Palermo Protocol (IOM, Citation2002, IOM Citation2007; ILO, Citation2004, ILO Citation2006; UNICEF Citation2006). Elena Tyuryukanova (Citation2006) highlighted human trafficking, its gender peculiarities, and the legal norms that provide the foundation for anti-trafficking campaigns in Russia. Trafficking of women for sexual exploitation was a topic addressed by scholars such as Erokhina (Citation2005), Orlova (Citation2004), Buckley (Citation2009), Ryazantsev (Citation2013), and Ryazantsev et al. (Citation2015). Research on sexual exploitation of men was begun much later (e.g. HRW Citation2009).

Journalists and some scholars focused on public opinion about trafficked victims (Buckley, Citation2009; NG Citation2016; Sharafiev, Citation2016). Mary Buckley (Citation2018) conducted a robust interdisciplinary study of the Russian politics surrounding human trafficking, migration, and labor exploitation, as well as their associated narratives, expert assessments, and public appraisals. She discusses the historical, socio-economic, and political contexts that have shaped migration since the protracted collapse of the USSR. Legal scholarship provides critiques of Russian law enforcement and police behavior (McCarthy, Citation2010, Citation2015; IOM, p. 2015), as well as the peculiarities of Russian legislation and migration policy (Zaionchkovskaya, Mkrtchan, & Turukanova, Citation2008; Pravda, Citation2017; IOM, Citation2009; Mukomel, Citation2013; Mukomel & Grigor’yeva, Citation2014; Voinikov, Citation2013; Ivakhnyuk & Iontsev, Citation2013). Susanne Schatral (Citation2010) analyzed IOM’s work in Russia. Her critique suggested that the categorizations IOM uses indicate the politicization of illegality for security reasons.

From an employer’s perspective, free movement in fSU countries creates opportunities to lower labor costs. The Russian profit-oriented economy demands cheap labor, hailing mainly from the less developed fSU countries or remote rural areas in Russia. Employers can take advantage of migrant laborers by paying them lower wages than they would pay Russians. A recent survey showed that only 50% of migrants had labor permits; about 30% were stopped by police often or occasionally to have their documents checked, and 11% had to pay bribes (Problemi, Citation2018).

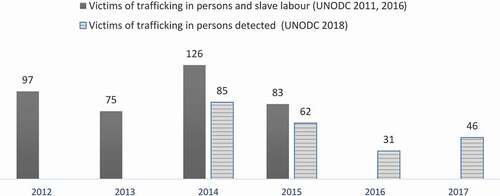

Russia submits statistics on human trafficking to UNDOC regularly (UNODC, Citation2011, Citation2016, Citation2018), but no information on methodology is provided; thus, the analytical value of these data is questionable (). Data on human trafficking in Russia are collected by the Analytical Center of the Ministry of Interior (MVD), using special monitoring forms 1-EGS, 2-EGS, 3-EGS.Footnote4 The MVD publishes an Annual Report on Crime (MVD, Citation2017a, Citation2017b) in aggregated indices and has no separate line for trafficking statistics (MVD, Citation2018, Citation2019). The 2018 crime statistics in Russia for 2018Footnote5 include many crimes, not just those violating anti-trafficking laws. Another compilation from the UNODC reports (UNODC, Citation2011, Citation2016, Citation2018) shows the absence of data for 2012 and difference in victims of trafficking in different reports.

The senior inspector of the General Directorate for Procedural Control of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation,Footnote6 Natalia Salenkova, identified the three most common types of human trafficking. The first is the organization of and recruitment for prostitution. Salenkova (Citation2013) argued that these victims are often addicted to alcohol, unemployed, from marginal families, and from rural areas. The second is the sale by women (or by families) of their young children.Footnote7 The third and most hidden crime is the exploitation of migrants. According to Salenkova, weaknesses in migration policy are the main factors contributing to human trafficking. Unresolved legal status affects vulnerability as migrants are unable to protect themselves from exploitation by recruiters and employers. A high demand for low-paid workers increases the migration of poorly educated and unqualified rural migrants from Central Asia ; however, they do not speak Russian and are unfamiliar with urban environments (IOM, Citation2013).

The Different Patterns of Labor Trafficking in Russia

There are several types of labor trafficking in Russia. One relates to the orgnabor recruitment system: beginning in the 2010s, the Russian government organized recruitment of migrant workers for the construction of facilities for the Olympic Games in Sochi, the APEC meeting in Vladivostok, and the World Cup Football stadiums through the bilateral agreements with North Korea, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan. North Korean migrants were managed by North Korean government staff, and their working conditions were similar to slavery. The Russian government does not see this practice as violating its anti-trafficking legislation because the Korean government agreed to it (HRW, Citation2013).

Direct human trafficking is a system in which victims are moved to places where they cannot operate independently, often far from relatives, friends, and acquaintances (e.g., in Dagestan republic brick factories). In Dagestan, for example, victims are brought from other regions and abused by the employers: “There is not a single criminal case when the director of a brick factory was imprisoned for using slave labor. The owners can resell him [victim], beat, or even kill him – nothing happens to the director” (Sharafiev, Citation2016). There are no fences surrounding the factories, but people are afraid of physical violence and do not know where to run without money or documents. Indirect trafficking involves turning legal migrants into irregular status by state or private enterprises. The migrant's freedom of movement is limited by employers who keep migrants’ documents ‘for registration’ or ‘for contract management.’

For Russian officials, such labor relations do not legally exist, because a person is either employed by a temporary company known as prokladka (subcontractor) or unemployed (Tax, Citation2015). Prokladka firms lend themselves to fraud and exploitation of labor migrants. Factories, department stores, municipal services, and even schools create subcontracting firms to recruit migrants to benefit from tax cuts, money laundering, and defrauding state funds. It costs 10,000 rubles (170 euro) to create such firms. The subcontractors are used by legal enterprises to transfer money and absolve the employer from the responsibility to pay salariesFootnote8 and tax. According to the Labor Code, prokladka firms can delay payment to the workers without consequences. They can even declare bankruptcy and not pay the workers at all. The Russian federal government newspaper Rossiiskaya gazeta reported that in 2011, out of 4.5 million registered enterprises, about half were “one-day fakes.” Such companies bribe the police and officers of the Migration Service (UFMS). An expert from the NGO «TONG JAHONI», V. Chupik, argued: “The situation has changed for the worse in recent years, which relates to the migration registration system and the attitude of the police toward migration. Nonpayment of wages to migrants is increasing. In 2012, our NGO received 10 thousand complaints for nonpayment of salary, in 2017 approximately 19 thousand, and in 2018 about 24 thousand” (Interview, December 3, 2018). Progress, however, has been made; by January 2016, the number of fake enterprises decreased from 45% to 15% as a result of legislation improvements and controls by the Federal Tax Service (RG, Citation2016). To understand the problems of labor trafficking in Russia, it is useful to understand the historical antecedents to current Russian migration policy; these will be described in more detail below.

Free Population Movements and New Trafficking Phenomena in the 1990s

The dissolution of the USSR resulted in freedom of movement and the replacement of the propiska system by registration. The new law ‘On Citizenship’ (1991) gave fSU citizens born before the collapse of the USSR the right to resettle in Russia for ten years. These fSU migrants were not foreigners according to the law, and were entitled to Russian social benefits (e.g., pensions and medical services). The Federal Migration Service (FMS), established in 1993, was responsible for the migration policy and assistance to some groups, including refugees and internally displaced persons.

The transformation of the Soviet planned economy into a free market economy led to unprecedented unemployment and drop in living standards due to massive shutdowns of state enterprises. Between 1990 and 1995, more than 30,000 factories were closed (Lipin, Citation1998). About five million Russians, of whom roughly 50% were women, lost jobs when the defense industry shut down (IOM, Citation2002). The privatization of state enterprises created a massive redistribution of property. By 1999, only 37% of the population worked in state and municipal enterprises (Ryvkina, Citation2003), while 15% to 25% of economically active people worked in the shadow economy.

Massive internal migration emerged when the first Chechen war erupted in 1994 and created fertile ground for criminal groups. The country experienced hostage-taking situations, abductions for money, slavery, and human trafficking. Slavery flourished in Chechnya when the territory was controlled by separatists between 1994 and 2001: about 46,000 people were enslaved or used as forced laborers. Not surprisingly, almost all Russian-speaking citizens – approximately 360,000 people – fled Chechnya in the 1990s (Kavlaz Yzel, Citation2016). I visited the region periodically between 2007 and 2015, and Chechen colleagues reported that during the two wars, many Chechen families in rural areas kept forced laborers – captured Russian soldiers or other Russian-speaking men – for their households.

In Russia, international migrants from various countries were also at risk for trafficking. During interviews, I was told that several helicopter crews found themselves stranded on Tongo Island (in the Pacific Ocean) without money, visas, and opportunities to return. A firmFootnote9 related to the Ministry of Aviation of Russia recruited pilots and technicians for the transportation of helicopters by a Russian jet to Tongo. Upon arrival on the island, the jet disappeared; all pilots and technicians remained there for 3 years, during which time the helicopter pilots worked for food. There was no Russian embassy. One by one, a local priest bought them tickets to Australia to escape from slavery (Interview, Moscow 1999).

Cases of ‘entrepreneurial trafficking’ of Russian-speaking criminals were investigated by US courtsFootnote10 in the 1990s, involving forced prostitution of approximately 8,000 women who were transported from Moscow to Miami to work for the strip-club “Porky’s” (UNICEF/ILO Citation2006). Sex trafficking in Russia reached an unprecedented scale in the 1990s, because the Russian Criminal Code was not yet adopted, the new law enforcement institutions were weak, and transnational criminal groups used these advantages in recruiting unaware migrants. Police corruption was also an obstacle (IOM, Citation2002). In the 1990s, Russian organized crime groups had often replaced the state in providing employment for vulnerable groups, especially single mothers and the poor, who could be victimized by pimps and brothels (Orlova, Citation2004).

In contrast to the present, in the 1990s, international labor migration was limited; the number of labor migrants was estimated at 280,000 people per year (Zaionchkovskaya, Citation2013). The majority of labor migrants were Ukrainians, Byelorussians, and Moldovans; they used their family networks to obtain registration and usually lived legally in Russia. Nevertheless, a quota for labor migrants was introduced at the end of the 1990s, and signs of irregular labor migration appeared. In 1996, Russia adopted a new Criminal Code containing an article detailing punishment for child trafficking (art.152) and organized prostitution, which is distinguished from prostitution as an individual activity. Furthermore, Russia initiated a process to develop the collective responsibility of the CIS countries for combatting transnational crime, illegal migration, and human trafficking. Treaties such as ‘On Cooperation on Border Control’ (1995), ‘On Information Exchange’ (1995), ‘On Combating Illegal Migration’ (1998), ‘On Combating Transnational Crime’ (1998), and ‘CIS Convention on HR and Basic Freedoms’ (1998) were signed by CIS countries (Molodikova, Citation2018).

In summary, in the 1990s, the threat of forced sex work and labor exploitation was not a major concern for Russian society. The collapse of the USSR, wars in Chechnya and on the periphery of Russia, affected the majority of the fSU and Russian population. New state regulations attempted, but were unable to capture, the new realities of exploitation. Russian legislation had not yet created the division between favorable and ‘alien’ fSU migrants.

New Leadership, Novelties in Migration Policy, and Old Problems of Human Trafficking in the 2000s

Toward the end of the 1990s, Russia was able to restore its economic potential, its GDP was several times higher than that of other CIS countries, and massive flows of labor migrants came in searching for work. The new leadership of Vladimir Putin brought peace to Chechnya in 2001. Putin supported activities and cooperation with international organizations, such as the IOM, ILO, UNDP, UNHCR, UNICEF, and UNODC. Russia adopted the Palermo Protocol and the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants in 2000, ratified both in 2004, and implemented them by introducing Article 127.1 and 127.2 (Use of Slave Labor) of the CC (Voinikov, Citation2013).

From 2004, federal and magistrate courts were obliged to keep trafficking statistics under Article 127 of the CC. The same year, the federal law “State Protection of Victims, Witnesses and other Participants of Criminal Proceedings” was adopted. Theoretically, all people – especially victims – involved in human trafficking court cases could ask law enforcement for protection. In reality, the government had no funds to cover those costs. In April 2007, the MVD established an anti-trafficking sub-department within the unit for combating organized crime and terrorism. Also in that year, a contact point was appointed for cooperation with Europol in the Interpol National Central Bureau. In 2010, the government prepared draft agreements for cooperation with law enforcement in the United Kingdom, Germany, Israel, and the United States (Mukomel, Citation2013). Moreover, Russia initiated several agreements with CIS countries (Citation2009, Citation2005; Agreement Citation2002, Citation2010).Footnote11 In 2007, CIS countries approved the first anti-trafficking cooperation program for 2007–2010, which was later extended to 2011–2013, and then to 2014–2018. The agreement included joint measures to combat human trafficking and assist its victims (UNODE Citation2011, Citation2016). Unfortunately, we have no evaluation of this cooperation, but the list of activities shows that Russia was taking trafficking seriously (Mukomel, Citation2013).

In parallel with the anti-trafficking policy, the world-wide movement toward securitization of migration and fears of terrorism significantly influenced Russian migration policy beginning in the 2000s, because between 1991 and 2000, terrorists carried out 1,896 attacks in Russia. In 2001–2010 the number multiplied almost six times (Zelobova, Citation2013). New securitization policies in Russia led to institutional and legislative changes that neutralized its anti-trafficking efforts. For security reasons – to control migration as a precaution against terrorists – the FMS was merged with the MVD, a rather punitive institution in Russia. The MVD had no experience in dealing with migrants or migration legislation, but only with lawbreakers. Their prime metric of success was to count the number of prevented law violations. They applied a similar mindset to migrants, seeing any person of different ethnicity or nationality as a potential terrorist or irregular migrant. Massive checks on people in public places often led to police abusing migrants, which met with criticism from Amnesty International and the “Civil Initiative” NGO (Zakluchenie, Citation2011).

New laws, ‘On Citizenship’ (2001) and ‘On Foreigners’ (2002), affected negatively relationships between different groups of migrants. Migrants from the fSU were separated into three groups with regard to registration and access to the labor market: (1) Russians and BelarusiansFootnote12 as a privileged group; (2) other CIS migrants, a less privileged group with required three-day registration using a new system of migration cards; and (3) ‘other’ third country nationals (with visa regulations). The new norms for CIS migrants registration essentially recreated the Soviet propiska system that was difficult to execute; this led to a situation in which the number of irregular migrants skyrocketed. As a result of these difficulties, only 7% of migrants were able to pass the three-day deadline established for registration by the MVD. All other migrants became irregular; any police officer could stop, arrest, fine, or deport them (Zaionchkovskaya et al., Citation2008). To profit from bribes, police took every opportunity to racially profile migrants (OSI, Citation2006). The MIA slowly realized the impossibility of registration within 3 days, and in 2003, the period for registration was extended to 1 month. However, this did little to improve the situation.

The other challenge of the new law ‘On Foreigners’ was the new ‘employer-employee’ relationship system that presumed the employer’s initiative and authorization by the state. Under this scheme, only an employer could initiate and obtain a work permit for foreign workers. Quotas on jobs and payment for quotasFootnote13 were introduced for employers for all 85 Russian administrative units. Thus, an employer had to submit a request for labor 1 year in advance, which was highly inconvenient. Additionally, employer taxation on foreigners’ wages could be as high as 30% (in comparison to 13% for Russian citizens) (Tyuryukanova, Citation2006). These measures led to the development of discriminatory practices by employers who did not register migrants. Moreover, after migrants completed their work, some employers called the police to deport them without pay. Attempts to initiate an amnesty for illegal migrants were not pursued since ‘victims of exploitation are afraid of law enforcement agencies more than of their employers’ (ILO/Tyurukanova, Citation2005). Speaking in the State Duma, Konstantin Romodanovsky, Director of the Federal Migration Service, called the migrant situation “the slave market” (Molodikova, Citation2009). The new institutional changes in migration management and legislation increased risks for human trafficking.

Unfortunately, in the 2000s, the key actors addressing the trafficking phenomenon in Russia were not state institutions but international and national NGOs. Russian human rights and women’s NGOs actively supported the activities of international organizations, initiating various anti-trafficking campaigns, mainly about the risks faced by migrant women outside the Russian Federation. They supported a series of studies on human trafficking (ILO Citation2005, ILO/Turukanova Citation2005; UNFRA/UNDP/UNICEF/ILO/IOM Citation2006, European Commission, UNICEF, Citation2011). In 2006–2009, a large-scale project entitled “Preventing Trafficking in Persons in the Russian Federation” – funded by the European Commission (EC), the US State Department, and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation – was implemented. It provided support to IOM to assist more than 450 trafficked victims (Ryazantsev, Citation2013). Influenced by fears of terrorist attacks and the anti-migrant rhetoric of law enforcement, public opinion blamed women forced into prostitution and became increasingly negative toward male migrants. In July 2002, positive and negative opinions toward migrants were almost equal (44% and 43%, respectively), but by November 2009 the balance was 30% to 61%, respectively (Levada Center, Citation2019).

Liberalization of Migration Policy, Abolishment of the Propiska System, and Human Trafficking

The demographic crisis (loss of population after 1992 due to population decline), failed migration policy of 2002–2006, and increasing demand for labor (40% of Russian enterprises suffered from labor shortage) facilitated an introduction of a new, liberal migration policy in 2007 (Molodikova, Citation2018). Several changes were introduced: first, the government increased the quota of labor migrants from visa-free countries from one to six million, and to 300,000 from visa countries. Second, it simplified the procedure of residence registration and replaced the propiska system for foreigners with a new migration card. Third, it simplified the procedure for acquiring work permits. Fourth, it imposed high penalties on employers for hiring illegal migrants: 800,000 rubles (about 32,000 USD) for state firms, and about 5,000 rubles (200 USD) for private enterprises. And, finally, it removed FMS from MVD (Molodikova, Citation2009).

The success of this policy was palpable. About 7.5 million migrants from visa-free CIS countries completed the registration process and 2.5 million received work permits. In 2009, 85% of migrants completed registration. These figures clearly indicate migrants’ willingness to be included in the regular labor market and contribute to the country’s economy through taxes. In July 2010, Russia introduced a labor licenseFootnote14 that partly replaced the unsuccessful quota system for migrants from visa-free CIS countries. The license cost was reasonable (USD 30); by 2014, the government approved 2.3 million licenses, up from 865,700 in 2011 (Vorobieva, Ribakovskii, & Ribakovskii, Citation2016).

Unfortunately, the problem of irregular migration was not solved by this liberalization of legislation. The Russian employment market resembles the European Union labor market, in which the implementation of general Directives and Regulations of the European Commission has its own peculiarities in each country. Something similar can be said about Russia’s 85 regional governments, which decide on the cost of the labor license, registration specifics, and demands for employers’ paper work. In Russia, migrant workers are bound to their place of housing and employment. They cannot buy a license for work in one federal region and then work (or live) in another. In 2011, a survey of employers in Moscow revealed that only 1% of employers were ready to accept foreign citizens legally, and only 9.5% would accept migrants legally for unskilled or extremely low-paying work (Chupik, Citation2014). Other employers were ready to hire migrants only on an irregular basis. Another survey showed that the absence of legal status significantly increased the risk of exploitation but did not directly impact their wages (Mukomel & Grigor’yeva, Citation2014). Thus, illegality pays: the average net salary of an irregular migrant is higher than that of legal migrants, because illegal workers, at minimum, avoid paying the 30% tax. In the trade and construction sectors, the gap between official and unofficial salaries was 30.1 and 10.1%, respectively (Mukomel & Grigor’yeva, Citation2014). Research has shown that many migrants in Russia have no motivation to gain legal status.

A similar situation exists among domestic workers, who constitute about 18% of all labor migrants in Russia; they hail mainly from CIS countries (Ryazantsev, Citation2015). The amendment to the law “On foreigners” in 2010 allows domestic workers to leave the shadow economy via obtaining a license and labor contract with a private employer. In 2010, the number of registered domestic workers increased from 20,700 to 129,700 in a six-month period (Zaionchkovskaya, Citation2014, p. 25). Nevertheless, the majority are still irregular: 84.4% of migrant domestic workers have no contract with their employer; of these, only 17.8% mentioned that “the owner was against the contract,” 67% said they “do not need a contract,” and 3.8% arrived without authorization. Unsurprisingly, in most instances, work conditions were negotiated verbally; 35.6% of the workers did not discuss them at all (Zaionchkovskaya, Citation2014, p. 49). There are some human trafficking elements in the domestic work: 46% of domestic workers live in the employer’s house, but 15% have no keys to the residence and free movement; 12.8% cannot leave their employer, and 6.4% have been sexually abused. Some employers stipulate these conditions in the hiring process.

The Eurasian Union, the Ukrainian Crisis, and the Ghost of Propiska in 2010s

The preparations for the Eurasian Union (EAEU) led to changes in migration legislation and a new hierarchy of relations between CIS countries to encourage EAEU member states and “punish” those CIS countries that did not want to join the EAEU. Since 2015, the Russian labor market has included four types of labor migrants: (1) Byelorussians; (2) migrants from EAEU states; (3) migrants from visa-free CIS states; and (4) migrants from visa-regime countries. This created a more complicated hierarchy of labor inequality. The first and second groups have free access to the Russian labor market and do not need work permits. The other migrants must pass three exams within 30 days of arrival to obtain a license or work permit: basic Russian language, Russian law, and Russian history. However, the majority of migrants are temporary workers, and for Chinese, Korean, and many Central Asian migrants it is almost impossible to pass these exams without being well-prepared or paying bribes.

One more negative consequence for migrants was the Ukraine crisis; in 2015, Western countries’ sanctions on Russia hit its economy and Russian currency (roubl) was devalued two times. To increase revenue from labor migrants, the cost of an employment license and the annual fee have risen dramatically, from $30 in 2011 to about $320 in 2019 – and sometimes more in other regions. The fees were supplemented by a mandatory monthly fee of 5,000 rubles per month (about 1000 USD per year). Such high license fees led to a rise in irregularity among migrants as a strategy to save money, which comprised about 33% of all labor migrants (Molodikova, Citation2018).

In addition, since January 2015, residence registration for migrants from non-EAEU, visa-free CIS countries staying in Russia without registration decreased from 180 to 90 days. Consequently, more migrants turned to the shadow economy as a survival strategy (Molodikova Citation2018). In 2013, a ban on migrants with administrative violations came into effect. According to the MVD, (MVD, Citation2018) between 2014 and 2018, about two million migrants, mainly from CIS countries, were deported and new arrivals were banned from entering the country. This ban resulted in irregular migration; some migrants tried to cross the Russian border using smugglers and false documents from CIS countries (IOM, Citation2016).

Last but not least, the FMS was merged again with the MVD in March 2016, despite earlier negative experiences. A restrictive migration policy has since returned: the new Law on Migrants’ Registration (№163-FZ of 28 June 2018) states that foreigners must reside only in their place of registration; otherwise, the owner of the place of registration (an individual or organization) can be fined (Polovinko & Vasil’chuk, Citation2018), and migrants can be banned from reentering Russia. Human rights activists believe the MVD has created these fines as an extra opportunity to solicit bribes. Criminals creating fake registrations are already benefiting from this policy, as the cost of a fake registration is 7000–8000 rubles (120 USD) (Polovinko & Vasil’chuk, Citation2018). Thus, the implementation of this new migrant law is problematic. Diaspora experts argue that the MVD seeks to invoke the propiska system as a kind of new serfdom for labor migrants.Footnote15

The registration system for foreign migrants is complicated and corrupt. The police violate migrants’ human rights through deprivation of freedom and physical abuse. The result is many cases of migrants’ irregularity with confiscation of passports. This means that in Russia, the majority of migrants are subject to systematic unjustified prosecution by police officers and other corrupt government agencies. The migration system of registration and taxation of foreign migrants has created a paradoxical situation in which some employers and employees engage in the shadow economy, which leads to high exploitation and puts workers at risk for trafficking.

The Security of Victims Is Their Own Matter

A case of slavery in the Moscow district of Galyanovo illustrates well the ineffective protection system and corruption of Russian law enforcement institutions. The 24-hour shop «FOOD» became famous in Russian media because the NGO “Alternative” freed eleven women and men from captivity that lasted in some cases for 10 years (Novaia Gazeta, Citation2016). For several years, the trafficked victims were not able to leave and were systematically raped and bitten. The shop owner was an Uzbek woman from Kazakhstan who recruited migrants from Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Many freed women were pregnant as a result of sexual abuse. Several times, some victims managed to escape and get to the police department, but they were returned to the shop. An activist from “Alternative” argued that local law enforcement agencies have known about the workers since at least 2002. Lawyers from the NGOs “Civic Assistance” and “Memorial” tried to file human trafficking and other criminal cases in court, but were refused 16 times (Fergananews, Citation2012). The victims, with the help of NGOs, filed a complaint with the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg in 2016 (Novaia Gazeta, Citation2016).

Lawyer, Ekaterina Melnikova (Citation2018), in her 2017 survey of 120 legal investigators in Russia, asked them about the state’s protection measures for trafficked victims, witnesses, and participants in criminal proceedings, and the effectiveness of the state protection mechanism. In response to the question “Why do victims, witnesses, and others involved in criminal justice proceedings not ask for state protection?” Melnikova received the following responses: 41% said they doubted that law enforcement agencies would be able to ensure their safety; 38% feared retribution from defendants; and 21% expressed unwillingness of victims to cooperate with law enforcement. These responses demonstrate a lack of confidence in Russian law enforcement institutions.

Unsurprisingly, the U.S. TIP report has placed Russia in Tier 3 since 2013 (TIP, Citation2013, Citation2019). The Russian government considered this ranking to be political manipulation and interference in its sovereignty. The politicization of the human trafficking issue coincided with the deterioration of US–Russia relations and had many negative consequences for trafficking as well. For example, Russia adopted a law “On Foreign Agents” (2013)Footnote16 (similar to the U.S. FARA law)Footnote17 and expelled many international donors. As a consequence, many local NGOs lost Western donors and stopped their activities, which seriously undermined assistance to trafficked victims.

There are various loopholes in Russian migration legislation that allow discrimination practices. The majority of trafficking cases involve corrupt state institutions and criminal employers or recruitment agencies (Aronowitz et al., Citation2010). As a result, human trafficking is prevalent in Russia. Irina Biryukova, a lawyer from the NGO “Public Verdict,” argues: “Such cases are hard to prove: … initiation of proceedings under these articles is almost impossible.” Expert Dmitry Poletaev stated: “Apparently, there is a system in which THB [trafficking in human beings] is the norm, … difficulties and time-consuming investigations of THB cases can reduce the overall indicator of success and effectiveness of the police, but their salaries depend on it [the indicator] now” (Sharafiev, Citation2016). A member of the Civil Chamber of the Russian Federation, Joseph Diskin, argued: “The law enforcement bodies are not active enough in the fight against organized crime. They have no motivation for this fight.” About 30% of the income from this illegal business goes for corruption: “the address of this corruption is the official structures that must conduct this control” (OPRF, Citation2014).

Conclusions: New Strategies to Fight Human Trafficking

The dissolution of the USSR led to major changes that increased the freedom of movement within Russia, but decreased living standards and created conditions for vulnerable people to be trafficked. Russia has signed the Convention on combating transnational crime and two Protocols (on trafficking and smuggling), and worked on many similar initiatives. Nevertheless, there are many stumbling blocks in the domestic implementation of migration legislation and policy. It is difficult to obtain accurate statistics on human trafficking in Russia for various reasons, including unclear research methodologies, and the fact that more than 20 CC articles relate in some way to trafficking offenses. The diffuse and ambiguous characterization of how human trafficking is recognized across the CC articles makes it difficult for prosecutors to prosecute these crimes and hinders effective anti-trafficking efforts, particularly with regard to labor trafficking, in Russia.

The government faces domestic challenges in combatting trafficking. Overall, migration policy has favored both the shadow economies that support trafficking and the punitive nature of Russian law enforcement that supports the propiska system. Because the average salary of irregular migrants is often higher than that of legal workers, many migrants are ready to accept some level of exploitation. Law enforcement institutions, taking advantage of loopholes in the legislation (especially with regard to registration regulations), often support the employers in their strategies to profit from discrimination and exploitation of migrants. The corrupt liaisons between law enforcement institutions and employers provide few chances to refuse work in low-paid services and industries.

The protection of victims is ineffective because of many factors, including corruption and distrust of law enforcement. Additionally, little assistance (medical, social, psychological) is available to victims. Currently, there are few NGOs working with trafficked victims, because the law ‘On Foreign Agents’ penalizes Russian NGOs for accepting support from international organizations. Given the ineffectiveness of current government efforts, experts from the Civil Chamber of the Russian Federation suggested the need to enhance civil society anti-trafficking efforts (OPRF, Citation2014). Thus, legislation exists, as well as numerous structures and institutions that should support its implementation, but specific socio-political-economic contexts hamper effective implementation of these laws.

A new Russian migration policy was adopted by Vladimir Putin in November 2018. The policy aimed at creating conditions attractive to migrants. But Russian law enforcement authorities are trying to restore residence registration similar to the system that existed in the USSR. The studies have shown that illegality is paid. There is a need to liberalize registration of seasonal workers, similar to what occurred in 2007, that would not require them to go through such procedures to prevent risks of labor trafficking.

The 2018 migration policy intends to eradicate corruption by using depersonalized electronic forms of communication between migrants and the authorities. However, lack of a clear definition of victims of human trafficking and a real mechanism for their protection, as well as significant distrust of law enforcement, complicate combating illegal migration, including human trafficking. In its fight against human trafficking, the Russian legislation mainly focuses on the use of criminal law mechanisms (Voinikov, Citation2013, p. 4). It is necessary to develop a trafficking victim protection system and to restore civil control of the system for preventing and combating exploitation by financially assisting victims.

The Russian 2018 Migration Policy Concept envisions the implementation of the migration policy through NGO participation “while respecting the principle of non-interference in the activities of public authorities,” which is inconsistent with the civil society concept per se. The current situation with the involvement of civil society in Russia is problematic and needs to be changed. However, it is important to note that the work of many NGOs with victims of trafficking in the beginning of 2000s in Russia shows their effectiveness in this field. Improvements in all these spheres should go a long way in ensuring the effectiveness of implementing the Palermo Protocol.

As the Russian case shows, it is one thing to have laws on the books, but another thing for them to be truly effective in combatting crimes like human trafficking. In addition, the inconsistent and dynamic character of other domestic policies, like migration policies, can cancel out the prosecution and protection efforts of existing Russian anti-trafficking laws. In light of the 20th anniversary of the Palermo Protocol, the Russian examples provide a sobering look at the work needed moving forward to reconcile national laws and policies to be coherently and consistently applied with the aims and spirit of Palermo.

Acknowledgments

This publication was prepared with the support of the Ministry of Education and Science of Russian Federation 28.2757.2017/4.6 Transit migration, transit regions and migration policy of Russia: Security and Eurasian integration, 2017–2019.

Notes

1 Russian poet and writer (1792–1872).

2 The Russian definition of trafficking differs slightly from that of the Palermo Protocol. Under the article 127.1 CC RF 2019, trafficking is defined as selling or purchasing a human being, other transactions with regards to a human being, as well as recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt previously committed for the purpose of exploitation.

3 Propiska was introduced by Stalin for the control of the Soviet population and limited the opportunity of USSR citizens to choose their place of residence. It requested every person to have a fixed residence approved by the authorities.

4 Since 2012, the following were introduced: Federal Form № 1-YEGS “Yedinyy otchet o prestupnosti” (Unified report on crimes), № 2-YEGS “Svedeniya o litsakh, sovershivshikh prestupleniya” (information about criminals), № 3-YEGS “Svedeniya o zaregistrirovannykh, raskrytykh i neraskrytykh” (information about the status of criminal investigation) http://docs.cntd.ru/document/902372684.

5 Of the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation in “Report on the number of prosecuted and types of criminal punishment” forma 10.1 unites all ‘Crimes against the freedom, honor and dignity of the individual’ with the articles from 126 to128.1, See: http://www.cdep.ru/index.php?id=79&item=4894.

6 This Directorate has authority to control the investigation of criminal cases.

7 In 2012, the Investigation Committee created a Specialized Unit to monitor the investigation of crimes both against minors and committed by them. The MVD established a “Child in danger” hotline, and incoming information is promptly checked by the General Directorate for Procedural Control of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation.

8 For a delay in the payment of wages, an employer can be brought both to administrative (Art. 5. 27 KoAP) and to CC (Art. 145.1) for 3 years imprisonment from March 10, 2010.

9 Odnodnevki, firms that are created for money laundering purpose.

10 See: Human Trafficking in the Russian Federation Inventory and Analysis of the Current Situation and Responses, file:///D:/1trafficking%20article/HumanTraffickingRFUnicef_EnglishBookTurukanova2006Eng_copy.pdf.

11 See the Agreement on cooperation of the CIS states on the issue of returning minors to the states of their permanent residence (Citation2002), the Agreement on cooperation of the CIS states in the fight against trafficking of persons, human organs and tissues (Citation2005), the Agreement on cooperation between the general prosecutor’s offices of the CIS member states in the fight against trafficking of persons, human organs and tissues (Citation2009), and the Agreement on cooperation of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (police) of the CIS states in the fight against trafficking of persons (Citation2010).

12 The Union Russia and Belorussia as one state was signed in 2006.

13 The quotas are for each region on the number of migrants. Employers pay for every migrant they want to “order” for the next year.

14 In Russia, patent is a labor license.

15 Roundtable discussions “Corruption and Migration” in the Moscow State Institute of International Relations, under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation on December 1, 2018.

16 It adopted the list of unwanted organization that forbidden provide any charity and other humanitarian assistance to Russian entities, including Russian NGOs. Those Russian NGOs that are ready to accept such funding have to pay very high taxes and report every month about their activities to special security organizations.

17 Foreign Agent Registration Act https://www.justice.gov/nsd-fara.

References

- Agreement on cooperation between the general prosecutor’s offices of the CIS member states in the fight against trafficking of persons, human organs and tissues . (2009). Unified register of legal acts and documents of CIS countries. Executive Committee of CIS countries/Official site. Retrieved from http://www.cis.minsk.by/reestr/ru/index.html#reestr/create

- Agreement on cooperation of the CIS states in the fight against trafficking of persons, human organs and tissues. (2005). Unified register of legal acts and documents of CIS countries. Executive Committee of CIS countries/Official site. Retrieved from http://www.cis.minsk.by/reestr/ru/index.html#reestr/create.

- Agreement on cooperation of the CIS states on the issue of returning minors to the states of their permanent residence. (2002). Unified register of legal acts and documents of CIS countries. Executive Committee of CIS countries/Official site. http://www.cis.minsk.by/reestr/ru/index.html#reestr/create.

- Agreement on cooperation of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (police) of the CIS states in the fight against trafficking. . (2010). Unified register of legal acts and documents of CIS countries. Executive Committee of CIS countries/Official site. Retrieved from http://www.cis.minsk.by/reestr/ru/index.html#reestr/create.

- Aronowitz, A., & Theuermann, G., &Tyurykanova, E., & OCSE. (2010). Analysing the business model of trafficking in human being to better prevent the crime. Vienna: OSCE. Retrieved from https://www.osce.org/secretariat/69028?download=true

- Buckley, M. (2009). Public Opinion in Russia on the Politics of Human Trafficking. Europe-Asia Studies, 61(2), 213–248. doi:10.1080/09668130802630847

- Buckley, M. (2018). The Politics of Unfree Labour in Russia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Chupik, V. (2014). Diskriminatsiya migrantov v Rossii. In V. Mukomel’ (Ed.), Migranty, migrantofobii i migratsionnaya politika (pp. 111–137). Russia, Moskva: Moskovskoye byuro po pravam cheloveka/Academia.

- Erokhina, L. (2005). Trafficking in Women in the Russian Far East: A Real or Imaginary Phenomenon?. In S. Stoecker & L. Shelley (Eds.), Human Traffic and Transnational Crime: Eurasian and American Perspectives. New York: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

- Fergananews. (2012, November 14). Rossia: Prokyratyra zakrila delo o moskovskih rabah za otsytstviem sostava prestyplenia. Mezdynarodnoe agenstvo novostei. Retrieved from https://www.fergananews.com/news/19770

- Gazeta, N. (2016, May 12). Hozyain skazal esli pozvonyu v skoruyu mne etu ruku otrezhut. Retrieved from https://www.novayagazeta.ru/articles/2016/05/12/68560-171-hozyain-skazal-esli-pozvonyu-v-skoruyu-mne-etu-ruku-otrezhut-187.

- Human Rights Watch. (2009). Are You Happy to Cheat Us. Report. HRW, Moscow: HRW.

- Human Rights Watch. (2013). Olympic Anti-Records. Exploitation of Labor Migrants in the Course of Preparation for 2014 Olympic Games in Sochi. Report. HRW, Moscow: HRW Retrieved from http://www.hrw.org/ru/reports/2013/02/06/olimpiiskie-antirekordy

- ILO. (2004). Prinyditelnii trud v sovremennoi Rossii. Nereguliryemaian migratsia I torgovlia ludmi. Moscow: Author.

- ILO/Tyuryukanova, E. (2005). Forced labour in the Russian Federation today: irregular migration and trafficking in human beings. Moscow: ILO. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.int/global/topics/forced-labour/publications/WCMS_081997/lang–en/index.htm

- ILO. (2006). Human Trafficking in the Russian Federation and Analysis of the Current situation and Responses, Report conducted by E.V. Tiurukanova and the Institute for Urban Economics for the UN/IOM Working Group on Trafficking in Human Beings. Moscow: ILO. Retrieved from http://www.childtrafficking.org/pdf/user/Unicef_RussiaTraffickingMar06.pdf

- IOM. (2002). Trafficking for Sexual Exploitation: The Case of the Russian Federation. MRS No. 7. Moscow: Author. Retrieved from https://publications.iom.int/books/mrs-ndeg7-trafficking-sexual-exploitation-case-russian-federation

- IOM. (2007). Torgovlia ludmi v Kaliningradskoi oblasti: Postanovka problem, Protivideistvie, Profilaktika. In T. S. Volchetskaya (Ed.). Vilnus: IOM.

- IOM. (2009). Torgovlia ludmi: viavlenie, raskritie, rassledovanie. Ychebnoe posobie, red. Levchenko O. P. Vladivostok: IOM. Retrieved from http://docplayer.ru/27772854-Torgovlya-lyudmi-vyyavlenie-raskrytie-rassledovanie-uchebnoe-posobie-pod-obshchey-redakciey-kandidata-yuridicheskih-nauk-o-p-levchenko.html

- IOM. (2013). Materiali mezdynarodnogo ‘kryglogo stola: Protivodeistvie torgovle lydmi Iokazanie pomoschi ee zertvam: rol’ I zadachi koordiniryyschih stryktyr gosydarstv-ychastnikov I organiv stran SNG 6 December 2013. Russia, Moscow: Author. Retrieved from http://moscow.iom.int/old/russian/publications/publication_round-table_December_2013.pdf

- IOM. (2016). Migrant Vulnerabilities and Integration Needs in Central Asia: Root Causes, Social and Economic Impact of Return Migration Regional Field Assessment in Central Asia, 2016. IOM. Almati: IOM Report. Retrieved from http://www.iom.kz/images/inform/FinalFullReport18SBNlogocom.pdf

- Ivakhnyuk, I., & Iontsev, V. (2013). Human Trafficking: Russia. Explanatory Note 13/55. Demographic-Economic Module. May, 2013. CARIM-East. European University Institute. Florence. Retrieved from http://humantraffickingsearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Explanatory-Notes_2013-55.pdf

- Kavkaz Yzel. (2016, 22 June). Rabstvo na Severnom Kavkaze. Kavkaz Yzel. Retrieved from https://www.kavkaz-uzel.eu/articles/251454/

- Kratkaya kharakteristika sostoyaniya prestupnosti v Rossiyskoy Federatsii za 2018 goda. 2019. MVD.

- Levada Center. (2019). Prezentatsiya: Migrantofobiya v rossijskom obshhestvennom mnebii. Moskva: Author. https://www.levada.ru/2019/01/18/prezentatsiya-migrantofobiya-v-rossijskom-obshhestvennom-mnenii/

- Lipin, A. (1998). Ekonomika Rossii v 1990-1998 godah. Osnovi Ekonomiki. pp. 4. Retrieved from http://old.nsu.ru/education/genecon/work/less/XXV/XXV.pdf

- McCarthy, L. A. (2010). Beyond Corruption. An Assessment of Russian Law Enforcement’s Fight Against Human Trafficking. Journal Demokratizatsiya, 18(1), 1–27.

- McCarthy, L. A. (2015). Trafficking Justice: How Russian Police Enforce New Laws, from Crime to Courtroom. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Melnikova, E. F. (2018). Realities of application of the legislation on state protection of participants in criminal proceedings. Vestnik Nizhegorodskoy Akademii MVD Rossii., 3(43), 253–259.

- Molodikova, I. (2007). Transformation of migration patterns in the Post-Soviet Space: Russian New Migration Policy of ‘Open Doors’ and its effect on European Migration Flow. Review of Sociology., 13(2), 1–15. doi:10.1556/RevSoc.13.2007.2.4

- Molodikova, I. (2009). New migration policy of Russia and old phobias to ethnic migrants. In J. Č.Žmegač (Ed.), Incorporating Co-ethnic Migrants. IBZ Munich university press.

- Molodikova, I. (2018). Handbook on Migration and Globalisation. In A. Triandafyllidou (Eds.), Eurasian Migration towards Russia: Regional Dynamics in the era of Globalisation. (pp. 334–359). Cheltenham, UK Edward Elgar.

- Mukomel, V. (2013). Human Trafficking: The Russian Federation. CARIM-East Explanatory. Socio-Political Module. Note 13/30. Florence: Florence European Institute. Retrieved from http://www.carim-east.eu/media/exno/Explanatory%20Notes_2013-30.pdf

- Mukomel’, V., & Grigor’yeva, K. (2014). Migranty i rossiyane na rynke truda: Usloviya, rezhim truda, zarabotnaya plata. In V. Mukomel’ (Ed.), Migranty, migrantofobii i migratsionnaya politika (pp. 82–99). Moskva: Moskovskoye byuro po pravam cheloveka Academia.

- MVD. (2017a). O rezultatah borby s organizovannoy prestupnostyu na territorii gosudarstv uchastnikov sng v 2014 godu analiticheskiy obzor. Moscow: Author. Retrieved from https://docplayer.ru/45772856-O-rezultatah-borby-s-organizovannoy-prestupnostyu-na-territorii-gosudarstv-uchastnikov-sng-v-2014-godu-analiticheskiy-obzor.html

- MVD. (2017b). Kompleksnyy analiz sostoianian prestypnosti v Rossiiskoi Federatsii po itogam 2016 goda I ozidaemie tendentsii yeye razvitia. Moskva, MVD: MVD. Analiticheskii obzor. Retrieved from. https://media.mvd.ru/files/embed/997033

- MVD. (2018). Svodka osnivnih pokazatelei dieiatelnosti po migratsionnoi situatsis v Rossiiskoi Federatsii za 2016. Glavnoe ypravlenia po voprosam migratsii MVD Rossii. Retrieved from. https://xn--b1aew.xn--p1ai/Deljatelnost/statistics/migracionnaya/item/9266550/

- OPRF. (2014). Novyye sposoby bor’by s sovremennym rabstvom. 2014, oktyabrya 30. Retrieved from https://www.oprf.ru/press/news/2014/newsitem/26697.

- Orlova, A. (2004). From social dislocation to human trafficking: The russian case. Problems of Post-Communism, 51(6), 14–22. doi:10.1080/10758216.2004.11052184

- OSI. (2006). Ethnic Profiling in the Moscow Metro. New york, NY: Author. Retrieved from https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/metro_20060613.pdf

- Polovinko, V., & Vasil’chuk, T. (2018). Novyye krepostnyye. Novaya gazeta. 2018 July 6. Retrieved from https://www.novayagazeta.ru/articles/2018/07/06/77057-velikoe-perevselenie-narodov

- Pravda. (2017). V Rossii viavili 200 kanalov torgovli ludmi, Pravda.ru 16 iunia 2017. Retrieved from https://www.pravda.ru/news/accidents/16-06-2017/1338289-human_trafficking-0/

- Problemi zaschiti prav detei, ne imeyschih grazdanstvo Rossiiskoi Federatsii v Moskve. (2018). Moskva: Ypolnomochennii po pravam cheloveka v Moskve - ROO Tsentr Migratsionnih Issledovanii.

- RG. (2016, February 15). Chislo firm-odnodnevok rezko snizilos’. Rossiyskaya gazeta. Retrieved from https://rg.ru/2016/02/15/chislo-firm-odnodnevok-rezko-snizilos.html

- RIA. (2018, December 21). V MVD nazvali chislo nelegal’nykh migrantov na territorii Rossii. RIA news. Retrieved from https://ria.ru/20181221/1548398795.html

- Ryazantsev, S. (2013 October). Project. Torgovlia ludmi s tseliu ih trudovoi ekspluatatsii I nezakonnaia trudovaia migratsia v Rossiiskoi federatsii: Formi, tendentsii, protivodeistvie. Sovet Gosudarsts Baltiiskogo moria. ADSTRINGO.

- Ryazantsev, S. (2015). Rossia v globalnou torgovle lydmi. Trydovaia eksplyatatsia v ‘migrantozavisimoy’ ekonomike. Migratsionnia Protsessi, 13,1(40), 6–22.

- Ryazantsev, S. V., Karabulatova, I. S., Mashin, R. V., Pismennaya, E. E., & Sivoplyasova, S. Y. (2015). Actual problems of human trafficking and illegal migration in the Russian federation. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(3 S1), doi: 10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n3s1p621

- Ryvkina, I. V. (2003). Functions and dysfunctions of additional activity in the post-Soviet Russia. In Z. Zaionchkovskaya (Ed.), Trudovaia migratsia v SHG: Sotsialnie I ekonomicheskie effecti (pp. 23–28). Russia, Moskva: Isentr Migratsionnih issledovanii.

- Salenkova, N. (2013). Materialy mezhdunarodnogo kruglogo stola «Protivodeystviye torgovle lyud’mi i okazaniye pomoshchi yeye zhertvam: Rol’ i zadachi koordiniruyushchikh struktur gosudarstv - uchastnikov i organov SNG». Kruglyy stol po trafikinu. Moscow: IOM.

- Schatral, S. (2010 Spring). Awareness Raising Campaigns Against Human Trafficking in the Russian Federation: Simply Adding Males or Redefining a Gendered Issue? Anthropology of East Europe Review, 28(1), S239–267.

- Sharafiev, I. (2016, November 17). 18 tysyach rubley za cheloveka. Meduza. Retrieved from https://meduza.io/feature/2016/11/17/18-tysyach-rubley-za-cheloveka

- Tax. (2015). Pismo Federal Tax Office on 24 July 2015. Retrieved from http://taxslov.ru/n135.htm

- TIP. (2013). Trafficking in Persons Report. 2012. U.S.: Department of State. Retrieved from http://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/2012/

- TIP. (2019). Trafficking in Persons Report: Russia. 2019. US: Department of State. 2019, June 20, Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/reports/2019-trafficking-in-persons-report-2/russia/

- Tyuryukanova, E. (2006). Human Trafficking in Russian Federation: Inventory and Analysis of the Current situation and responses. Moscow: Institute for Urban Economics for the UN/IOM.

- UNFPA/UNDP/UNICEF/ILO/IOM. (2006). Human Trafficking in the Russian Federation: Overview and Analysis of the Current Situation. E.V. Tyuryukanova. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/ru/rights/trafficking/human_trafficking_russia.pdf

- UNICEF. (2011). Analysis of Position of Children in the Russian Federation: on the Path towards Society of Equal Opportunity. Retrieved from http://www.unicef.ru/upload/ATTJVRGA.pdf

- UNODC. (2011). Country Profiles. Europe and Central Asia. Russian Federation. Trafficking data 2008-2010. Retrieved from http://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/glotip/Country_Profiles_Europe_Central_Asia.pdf

- UNODC. (2016). Country Profiles. Europe and Central Asia. Russian Federation. Trafficking data 2012-2015. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/glotip/Glotip16_Country_profile_E_EuropeCentral_Asia.pdf

- UNODC. (2018). Country Profiles Europe and Central Asia. Russian Federation. Trafficking data 2015-2017. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/glotip/2018/GLOTIP_2018_EASTERN_EUROPE_AND_CENTRAL_ASIA.pdf

- Voinikov, V. (2013). Legal regulation of combat against human trafficking in the Russian Federation CARIM-East Explanatory Note 13/38. Legal module. Retrieved from www.Carim-east.eu/media/expo/Explanatory%20Note_2013-38.pdf

- Vorobieva, O., Ribakovskii, L. L., & Ribakovskii, O. L. (2016). Migratsionnaia Politika Rossii: Istoria i Sovremennost. Moscow: Ekon-Inform.

- World Bank group. 2016. Migration and Remittances factbook, third addition, 2016. Washington: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/23743/9781464803192.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

- Zaionchkovskaya, Z. (2013). Migratsia v sovremennoi Rossii.2018, April 16 Retrieved from russiancouncil.ru/inner/?id_4=1714#top-content

- Zaionchkovskaya, Z. (2014). Domashnie Raborniki v Rossii I Kazakhstane. Almati: otsenka polozenia domashnih rabotnikov na rinkah tryda Rossii I Kazakhstana. Moskva: UN-Zinschini.Ex-Libris.

- Zaionchkovskaya, Z., Mkrtchan, N., & Turukanova, E. (2008). Rossia pered vizovami immigratsii. Moscow: INHP RAS.

- Zakluchenie, G. B. (2011). In Voronkova V., Gladareva B., Sagitovoy L (Eds.), Militsiya i etnicheskiye migranty: praktiki vzaimodeystviya. (pp. 589–619). SPb.: Aleteyya.

- Zelobova, M. (2013) Grafik dnia: Po sravneniy s 1990-mi chislo teraktov v Rossii viroslo v 6 raz. Republic. 30 December. Retrieved from https://republic.ru/posts/L/10