Introduction: carto-synaesthesia?

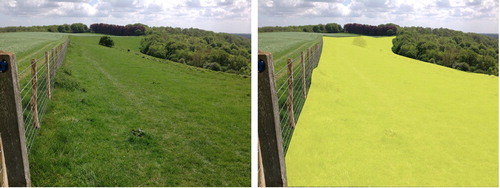

While walking across the rough pasture on the hills above Ashford, Kent (UK), I experienced a dramatic vision. The dull green grassland turned a solid flat bright yellow (). It was over in an instance, like the shutter movement of an old fashion camera, but very real – as if triggered by a physical light stimulus – not as something in my ‘mind’s eye’. While not a case of synaesthesia, that phenomenon is the best way I can describe what happened.

Synaesthesia is a neurological condition in which stimuli (e.g. reflected light) that usually affects one sense impacts on two or more others. Some synesthetes, for example, experience a ‘taste’ associated with a specific colour or word. Synaesthesia occurs when in normal circumstances a person might imagine a colour, but a synesthete will see it projected externally. For true synaesthesia the link is durable – this was not true for me, it has never happened again.

A study of ‘colour-grapheme’ synesthetes indicates that pairings of letters with colours was traceable to childhood toys containing coloured letters (Witthoft & Winawer, Citation2013); the authors characterise this as ‘learned synaesthesia’. By the time I had my experience I had been using Land Utilisation Survey (LUS) maps (1930s) in local field teaching for decades (‘Weald of Kent & Hastings’ sheets 125 & 135). It seemed probable that the experience must have been stimulated by my familiarity with the LUS – the bright yellow I experienced represents ‘Heath, Moorland, Commons and rough pasture’.

Clearly, maps can be a significant element in an immersive relationship with place (Vujakovic & Hills, Citation2017), not just as a navigation aid and store of spatial information but as an artefact that affords constant re-reading of, and re-engagement with a familiar milieu. Topographic maps (e.g. the British Ordnance Survey (OS) series, and related products, such as the LUS), provide a partial but significant representation of the cultural landscapes we inhabit.

This paper argues for a ‘dwelling’ perspective (see below) in understanding the relationship between maps, person, and place, but one in which we need to understand the role of both agency and structure. Agency is the individual’s ability to think and act independently. By contrast, structure involves factors that constrain or limit agency. Structure can involve issues such as economics, social class, gender, and social mores.

Map as biography

This essay takes its theme from Brian Harley’s meditation on a map as a biographic document (including autobiography) and as having a biography (Harley, Citation1987). In his essay (subtitled ‘thoughts on Ordnance Survey map, Six-inch Sheet Devonshire CIX, SE, Newton Abbott’) he celebrates four levels of biography. The first concerns the biography of the map itself and the second the people who created it. It is the next levels, however, that is the immediate concern here – the idea that the map is a biography of a landscape (surveyed in 1885–1886, revised 1904), and finally autobiographical elements. While mentioning the rural domain, Harley's focus is on the map as biography of Newton Abbott and the division of space into the realms of the rich and the poor. The autobiographic level, for Harley, involve bitter-sweet personal place-associations, including the church where his daughter wed, and where his wife and son’s ashes are buried.

People, maps, and memorialised space/place

Harley noted that ‘with the progress of scientific mapping, space became all too easily a socially empty commodity, a geometrical landscape of cold, non-human facts’; maps ‘dehumanize’ landscape (Harley, Citation1988, reprinted 2001; p.99). Yet Harley’s (Citation1987) essay of the previous year is a eulogy to the map as biography and memorial, in the sense that they serve to preserve remembrance. Maps commemorate a place and a time – even when this may involve elements of ‘cultural violence’ by expunging the memory of some peoples from the (colonial) landscape. There is, however, clearly a tension here, between agency – the ability of the individual to engage meaningfully with the landscape through the map – and structure – the ordering and control of land and resources through mapping (see Harley, Citation2001; collected essays 1988–1994).

While Harley’s article was a popular piece aimed at readers of The Map Collector it provides a step toward a post-representational cartography. By writing about life-worlds and introducing the ‘self’ into his discussion of the map as biography, Harley was engaging in a limited form of ‘autoethnography’:

By writing themselves into their own work as major characters, autoethnographers have challenged accepted views about silent authorship, where the researcher’s voice is not included in the presentation of findings. (Holt, Citation2003, p. 19)

Kitchen et al. (Citation2013) discuss ethnographic methods, including ‘self-ethnography’, as a means of understanding mapping as a ‘messy, emergent process’, and as a move from a limited textual and linguistic deconstructionist ontology. The map as ‘immutable mobile’ – as stable and transferable – is challenged and primacy is allotted to the individual as agent, with each reading generating ‘new mappings’ (see also Azócar Fernandez & Buchroithner, Citation2014; Caquard, Citation2015; Kitchen & Dodge, Citation2007 for discussion of post-representational cartography).

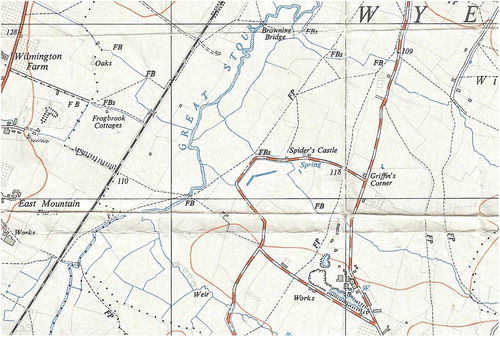

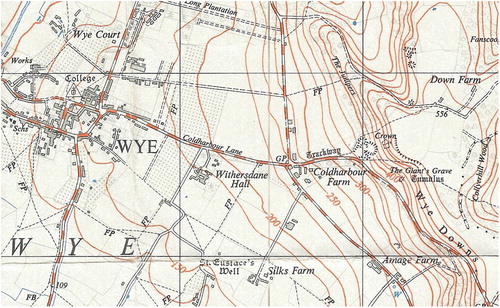

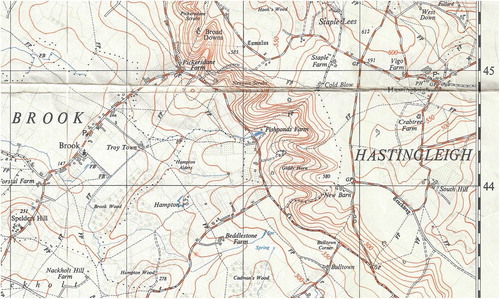

Harley’s essay prompted me to reconsider my own relationship with a map, SHEET TR04 Ordnance Survey Provisional Edition (1:25,000; printed 1958, reprinted with minor editions 1961).Footnote1 The map, representing ten by ten kilometres, is centred very close to my home for nearly a decade and a half (until late 2020). The largest settlement mapped is Ashford, and the map is almost bisected by the river Great Stour, which flows north from Ashford, to cut through the North Downs (chalk hills) near the village of Wye. I visited this landscape regularly as a child, I undertook my undergraduate research project there, and ran a university field exercise on countryside and land use change there for twenty-four years ().Footnote2 My connection, however, predates my own life. My father worked in agriculture on an estate close to Wye in the late 1940s; he was ‘displaced’ (a refugee) during WWII, finally settling in Kent. This was the familial connection that drew us to the area for many years. Like Harley, the area and map contain a memorial; my father’s ashes are scattered on the Downs.

Figure 2. The author’s teaching and research field sites at Broad Down and the location of key elements the Riddley Walker narrative (extract from Sheet TR04).

My engagement with the landscape and one specific map as an autoethnographic process emerged relatively recently. I did not start with any overt intention to understand mapping in the context of TR04 as an ‘emergent process’. The opportunity to coordinate and write several articles for a collection celebrating International Map Year (in 2016) and write a series following the Great Stour from source to sea focused my attention on the OS Provisional Series as an evocative and very personal representation of landscape (both collections were published monthly in Kent Life magazine). The Provisional Series has a distinct aesthetic appeal, especially the use of muted colours. The orange-brown contours clearly reveal the structure of the landscape (disrupted by other symbology on more recent OS series at the same scale); the rivers in mid blue are wonderfully easy to identify and follow – I used this series as my prime source throughout my exploration of the Stour for Kent Life. On TR04 only the slash of orange representing a new road by-pass jars.

My thinking concerning landscape, memory and TR04 further crystalised with the invitation to give the Michael Nightingale Memorial Lecture.Footnote3 This brought into focus my personal relationship with the landscape as ‘my patch’ (walking, foraging, engaging with nature, and location of home) and my professional interest in landscape history and cultural geography. Both worlds involve an immersion in ‘sense of place’ in spatial and temporal terms that I began to explore.

The temporal component involves a strangely unique element as the landscape of TR04 is central to the plot of Russell Hoban’s (Citation1980) cult novel Riddley Walker (the eponymous hero). Set in a post-apocalypse East Kent several thousand years in the future, Riddley’s world is a return to something like the Iron Age, with scavengers eking out an existence alongside a developing agricultural economy. The book is written in ‘Riddley Speak’, a mutated form of English which is difficult to read and best spoken-out slowly to make sense on a first reading (Self, Citation2002). The book contains a map drawn by Riddley on which real places, so familiar to me, are mapped but have altered names reflecting their new ‘reality’ (Vujakovic, Citation2018a). My familiarity with the prehistory and history of the area, as well as ‘Riddley world’, means that my creative engagement with the landscape and maps extends into ‘deep-time’ in two directions. I find my consciousness of place flipping between past, present and future, especially when using maps in the field (this has included use of facsimiles of TR04 to lead an experimental walkFootnote4 through Riddley’s world as part of a conference on sense of place). This concern with ‘deep-time’ comes into focus for me through two specific sets of engagement; one with scars on the landscape, the etched evidence of past peoples and their activities, the other with toponyms (placenames).

Naming and sense of place

Naming imbues space with a ‘sense of place’, although the original meanings are generally lost in time. Toponyms are an essential element of topographic maps and they create a certain poesy of place; ‘Calling at Wye, Chilham, Chartham, and Canterbury West’ – rhyme and alliteration make poetry from the stations along a stretch of the Stour. Names matter and Hoban reminds us of this. Hoban’s names are not those used today, which for many are appelations with no overt meaning. Hoban adds context (examples from within TR04); Godmersham (Old English (OE): the homestead of Godmaer) becomes a place of refuge – ‘Good Mercy’; Ashford becomes ‘Bernt Arse’ (one of the dead towns); and Withersdane (possibly OE: sheep pasture) becomes ‘Widders Dump’ – the widow maker – where Ridddley’s father is crushed to death while scavenging iron.

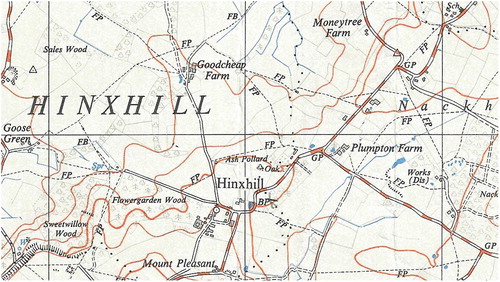

We rarely question the origins of the toponyms on maps or road signs, or in our heads. By conjuring with names Hoban forces us to seek meaning. There is an important passage in the book that explicitly explores the fictional etymology of folk-names for a place and reveals Hoban’s intent as more than playful. In the story ‘The bloak as Got on Top of Aunty’, the origin of ‘Hagmans Il’ [Hinxhill on TR04 ()] is discussed; with permutations including ‘Hangmans Hil’, ‘Hogmans Killen’ (where a man named Hogman made pots), and where he was murdered by his wife, so mutates to ‘Hogmans Kil’, and finally settles as ‘Hagmans Il’ – ‘becaws she ben a rough and ugly old woman and it come il he marrit her’. The protagonist of the story within the story even suggests a change to ‘Hagmans Thril’ having survived sexual intercourse with death (Aunty).

Figure 3. Hinxhill: Old English ‘Haenostesyle’ – hill of the stallion or man named Hengist (extract from Sheet TR04).

So familiar with the story and landscape I find myself thinking in ‘Riddley speak’ for many localities; some places lend themselves to his tone and meaning, but not all. I do not think of Hinxhill as ‘Hagmans Il’, but rather as ‘Hengist Hill’, its purported origin being the Old English ‘Haenostesyle – hill of the stallion or man named Hengist’. Older maps also provide a memorial for placenames now erased by destruction, erosion and map revision; the story of Spider’s Castle () is just one (Vujakovic, Citation2012), a now barren plot of brambles regularly passed on walks.

Map as memory – taskscapes and scarification

Tim Ingold (Citation1993) has argued for a ‘dwelling perspective’ in which ‘the landscape is constituted as an enduring record of – and testimony to – the lives and works of past generations who have dwelt within it, and in doing so, have left there something of themselves’ (p.152). He introduced the term ‘taskscape’ to describe the array of inter-related activities that continuously creates landscape. Ingold echoes the landscape historian W.G. Hoskins, for who an understanding of landscape was arrived at by striving’ … to hear the men and women talking and working, and creating what has come down to us’ (Hoskins, Citation1967, p. 184; cited in Johnson, Citation2007, p. 41)

‘Widders Dump’/Withersdane, where Riddley’s father dies, is the location of a pit where scrap iron is dug out in this future world. His father dies when a crane fails and drops its load. This element of the story resonates with another link between maps and (auto)biography/enthnography. As well as being a largely agricultural landscape TR04 includes several past activities that have scarified the landscape by rubbing, scratching, gouging, or by cutting designs into the skin of the earth. Significant scars include extraction pits, droves and hollow lanes, abandoned ditches and watercress beds, ancient embankments, and modern symbolic carvings in the chalk. Like the damage sustained by veteran trees in the local woods (Vujakovic, Citation2013), these scars add nuance to maps as biographic testimony to past ‘taskscapes’.

Scars and other landscape features are often discussed in terms of the palimpsest. The term is derived from old manuscripts written on vellum; vellum was expensive and was reused by scrapping away unrequired text and writing over it, although the removal was never perfect, and the previous text could still be deciphered. This is the same for ancient trackways, field patterns and so forth – evident in the field or from aerial photography, or recorded on maps; these marks reveal the landscape as congealed ‘taskscapes’. It is in this sense that I approach the landscape and the map. Above Withersdane, for example, I ‘encounter’ a centuries old time-line of delving for resources; from the chalk quarry at the base of the hill, worked until the late 1800s to provide ‘lime’ for the heavy clay fields nearby, I then follow a path that flanks a giant crown carved into the chalk to celebrate the coronation of Edward VII in 1902 (), before ascending to the summit where a series of pits provide evidence of a much older taskscape. The pits, bounded by a low earthwork, are believed to be Iron Age workings of weathered marcasite, an iron oxide; found in a thin superficial deposit above the chalk. This is possibly the earliest iron ore mine in the country (CitationKCC, undated). Here, on a dank winter day, one can visualise, and empathise with those long dead people (Vujakovic, Citation2018b) labouring at their tasks of extraction and transportation of materials from the site just a kilometre or so from the estate my father worked on two millennia later.

Conclusion and some words of warning

This has been a personal exploration of the map as biography based on Harley’s original article that provided a fruitful point of departure for an autoethnography of map use. However, a post-representational approach that privileges individual agency and regards mapping as a constant process is potentially hazardous. Maps are and will remain tools of power. Cartography is implicated in both structural and cultural violence (Vujakovic, Citationin press) which is not erased by a paradigm shift, but is perhaps (conveniently?) hidden by it. Maps as biography have a significant role in unlocking access to and encouraging engagement with landscape and social history, but need to be treated with care. The white space of the UK’s OS maps represents a landscape of power that is not erased by any amount of refolding, artistry or ‘remapping’; some 15% of the freehold land in England & Wales is not registered – its ownership unknown. Access is still restricted over much land in England and Wales despite a good network of public rights of way and more recent ‘open access’ agreements. Understanding and challenging inequalities, coercion and asymmetries of power worldwide may come from acknowledging that maps are an element in the neo-Baroque arsenal of power tools (Vujakovic, Citation2018c), and that critical cartographies and ‘counter-mappings’ (Perkins, Citation2018) can speak truth to power.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 National Library of Scotland - Ordnance Survey, 1:25,000 maps of Great Britain (Regular series) – 1945–1969, https://maps.nls.uk/os/25k-gb-1937-61/info1.html

2 Map extracts Crown Copyright 1961 (copyright expired). Extracts are scans from a copy of TR04 held by Canterbury Christ Church University.

3 ‘The Map As Biography: Maps, Memory And The Kent Landscape’, Seventh Annual Nightingale Lecture (given by Peter Vujakovic), 25 September 2018, Brook Agricultural Museum in association with Kent Centre for History and Heritage (Canterbury Christ Church University).

4 ‘Total Immersion: maps, memory and sense of place’ (walk led by Peter Vujakovic) as part of ‘Sense of Place’: Imagination and the landscapes of Kent’, conference held at Canterbury Christ Church University, 22–23 June 2017.

References

- Azócar Fernandez, P. I., & Buchroithner, M. F. (2014). Paradigms in cartography: An epistemological review of the 20th and 21st centuries. Springer-Verlag.

- Caquard, S. (2015). Cartography III: A post-representational perspective on cognitive cartography. Progress in Human Geography, 39(2), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132514527039

- Harley, B. (1987). The Map as biography: Thoughts on Ordnance Survey map, Six-inch Sheet Devonshire CIX, SE, Newton Abbott, The Map Collector, 41, 18-20; reprinted. In M. Dodge, R. Kitchen, & C. Perkins (Eds.), (2011) The Map reader: Theories of mapping practice and cartographic representation (pp. 327–331). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Harley, B. (1988). Silences and secrecy: The hidden Agenda of Cartography in early modern Europe. Imago Mundi, 40(1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085698808592639

- Harley, B. (2001). The New nature of maps: Essays in the history of cartography. John Hopkins UP.

- Hoban, R. (1980). Riddley walker. Jonathan Cape.

- Holt, N. (2003). Representation, legitimation, and autoethnography: An autoethnographic writing story. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2(1), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690300200102

- Hoskins, W. G. (1967). Fieldwork in local history. Faber.

- Ingold, T. (1993). The temporality of the landscape. World Archaeology, 25(2), 152–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1993.9980235

- Johnson, M. (2007). Ideas of landscape. Blackwell.

- KCC (undated) Possible Iron Age mine pits. 2021. Wye downs. https://webapps.kent.gov.uk/KCC.ExploringKentsPast.Web.Sites.Public/SingleResult.aspx?uid=MKE3868.

- Kitchen, R., & Dodge, M. (2007). Rethinking maps. Progress in Human Geography, 31(3), 331–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132507077082

- Kitchen, R., Gleeson, J., & Dodge, M. (2013). Unfolding mapping practices: A new epistemology for cartography. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 38(3), 480–496. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00540.x

- Perkins, C. (2018). Critical cartography. In A. Kent & P. Vujakovic (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of mapping and cartography (pp. 80–89). Routledge.

- Self, W. (2002). Introduction. In H. R. Riddley Walker (Ed.), Expanded twentieth anniversary edition. pp. v–x. Bloomsbury.

- Vujakovic, P. (2012). Spider’s Moving Castle: re-inscribing a ‘sense of place’, Maplines, Spring 2012, (p. 10–11).

- Vujakovic, P. (2013). Phytobiography: An approach to ‘tree-time’ & ‘long-life learning’. Arboricultural Journal, 35(2), 134–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071375.2013.852363

- Vujakovic, P. (2018a). Maps and imagination. In A. Kent & P. Vujakovic (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of mapping and cartography (pp. 489–499). Routledge.

- Vujakovic, P. (2018b). Prehistoric ‘taskscapes’: Representing gender, Age and the Geography of work. Visual Culture in Britain, 19(2), 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/14714787.2018.1473048

- Vujakovic, P. (2018c). Maps as spectacle. In A. Kent & P. Vujakovic (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of mapping and cartography (pp. 101–113). Routledge.

- Vujakovic, P., & Hills, J. (2017). Total immersion: Maps, landscape and memory. Bulletin of the Society of Cartographers, 50, 37–43.

- Vujakovic, P. (in press). Dark cartographies: The mapping of slow violence. In S. O’Lear (Ed.), Geographies of slow violence: A research agenda (pp. 205–223). Edward Elgar Press.

- Witthoft, N., & Winawer, J. (2013). Learning, memory, and synesthesia. Psychological Science, 24(3), 258–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612452573