ABSTRACT

This paper describes the process and findings of a critical evaluation conducted for a custom-made Location based game (LBG) designed to support reflection on social history. We use a mixed-method protocol to answer the following research questions: “Can a LBG be designed to stimulate situated reflection on social history topics? and “What form and type of reflections can occur when participating in a LBG? Using an innovative approach that took inspiration from the field of museum studies and computer science. We chose a Think-aloud protocol to conduct an evaluation in Valletta, Malta and adapted the Remind study protocol to explore participant experience in Luxembourg. We combined transcripts from both sets of experiments wiith user-generated content to complete a systematic analysis using a predefined set of qualitative codes. We were able to identify that LBG can support reflection on social history topics but the depth of and type of reflection depends on the social history content, the individual locations in the city, and personal connections players are able to make to both.

Ce papier décrit le processus et les résultats d'une évaluation critique réalisée sur un jeu sur mesure basé sur la localisation (JBL) conçu pour faciliter la réflexion sur l'histoire sociale. Nous utilisons un protocole à méthodes mixtes pour répondre aux questions suivantes : « Est-ce que un JBL peut être conçu pour stimuler des réflexions localisées sur des sujets d'histoire sociale ? » et « Quels formes et types de réflexions peuvent subvenir lors de la participation à un JBL ? », en utilisant une approche innovante qui s'inspire du champ des études muséales et de l'informatique. Nous avons choisi un protocole de la pensée à voix haute (think-aloud protocol) pour réaliser une évaluation à la Valette (Malte) et nous avons adapté le protocole d'étude de rappel pour explorer l'expérience des participants au Luxembourg. Nous avons combiné les transcriptions à partir des deux ensembles d'expériences avec du contenu généré par les participants pour réaliser une analyse systématique en utilisant un ensemble prédéfini de codes qualitatifs. Nous avons pu identifier que le JBL peut susciter des réflexions sur des sujets de l'histoire sociale mais que la profondeur et le type de réflexion dépendent du contenu de l'histoire sociale, des localisations individuelles dans la ville et des connections personnelles que les joueurs sont capables de faire entre ces deux points.

1. Introduction

This paper describes the process and findings of a critical evaluation of a custom made Location-based game designed to support reflection on social history.

2. Location-based games and the smart city

Locative media offers users new possibilities to discover and interact in and with the city, using GPS, data connectivity and mapping technologies integrated into smartphones. These pervasive technologies integrated into smartphones enable tools, services and apps that transform our relationship with cities, and the places and people within, leading to a broad range of research (Cashman & Phelps, Citation2009; Saker & Evans, Citation2016; Silva & Jordan, Citation2012). Consequently, we are witnessing a growing market in location-based games (LBG) and gamified location experiences engaging millions of players; take Geocaching, PokémonGo, and Ingress as examples. In addition, there are many niche apps successfully engaging outdoor play and urban discovery, albeit at a different, local scale of use. Such capabilities provide playful experiences where the fabric of the city transforms into something akin to a living board game or interactive playground.

Consequently, these interactions between the digital and physical worlds continuously shape and reshape our experiences with, and our meaning(s) of urban place(s), providing a counter dynamic to the everyday functional uses of the city. They contribute to urban interventions that transform the uses of the city. In the literature such interventions are referred to as urban counter dynamics (Crawford, Citation2012). They result in playful urban interventions that contribute new mechanisms for inhabiting and interpreting spaces, and deeply modify our relationship to space and place, time, human relationships (exchanges, knowledge sharing, etc.), or to work (Crosnier & Vidal, Citation2017).

Location-based games create a confluence between physical and digital spaces, producing new forms of urban play and playfulness that subsequently influence notions of the lived city and its role in play (Saker & Evans, Citation2016). They are said to support the development of new forms of interactions and experience in the city that lead to the development of place value and place identity. Thus, perhaps they could be an antidote to some of the issues arising from modern functional society? Some scholars have argued that it is a fundamental right that we develop our feelings of connection to the spaces we inhabit, i.e. through place attachments, rootedness, place-based meanings, memories identities and feelings that we ascribe (Eldon on Heidegger (Elden, Citation2005; Relph, Citation1976)). Such rights should be nurtured and valued by planners, decision-makers and society in general. But for some the rights are being devalued and eroded because of the dysfunctional effects of modern life and globalisation. For example, modern urban design and development, digital media, smart technology, transient lifestyles, remote working, political rhetoric, economic structures and the emphasis on the functional nature of smart cities all contribute to this sense of placelessness and the deterioration of our attachments and sense of belonging (Connerton, Citation2009; Jacobs, Citation2016; Kitchin, Citation2014; Relph, Citation1976). The challenge then is to consider how and if gamified location-based experiences can alleviate the impact of these dysfunctional effects.

2.1. Design challenges of gamified location-based experiences & location-based games

With the advent of location-aware mobile phones, we observe changes in the activity and materiality of the city, leading to different types of encounters, transforming how we express our relationships and personal identity. Location-aware experiences place the citizen(s) at heart, disrupting the normative materiality and activity of places and seamlessly intertwining the digital and the physical worlds. This shapes the hidden relationships with the city, turning it into a place of play. In this study, we also consider if the city can become a place for playful reflection on history.

3. Study aims

The premise behind the CrossCult:City App was to co-design a location-based game to stimulate citizen's reflection on social history in topics such as migration, art and architecture, industrial heritage, or language and identity. Through the promotion of citizen participation (co-creation), we imagined a playful and thought-provoking game that could support processes of reflective thought. The App attempted to stimulate reflection on history by encouraging the interactive discovery of historical content in relevant places. We designed the App to provoke reflection and (re)interpretation on historical topics in the cities of Luxembourg and Valletta, Malta. The following research description outlines our evaluation methods and analytical findings to determine if we met our aim.

3.1. About the app

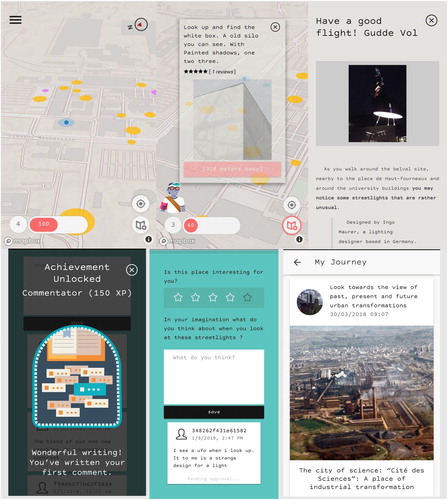

The game's core loop uses location services to identify the participant's location and highlight nearby Points of Interest (POIs) ( – top left). The POIs are symbolised as yellow or purple circles – yellow for curated stories and purple for player-contributed stories. Each POI is also connected to a Navigation clue ( – top middle). The text of the clue hints towards the content and topic of the story, e.g. ‘look up and you will see, painted shadows 1,2,3’. This is a clue about an art installation on an old silo used in the steel industry. The silo is a set of lines painted on it. The painted shadows are the mirror of real shadows from the blast furnace at a particular time of day. As soon as the player's physical location (blue dot) is located within the yellow or purple circle, they can open, read and interact with the story. The stories discovered have either a direct connection to the POI or a metaphorical one (i.e. the location symbolises the story through the age of the building or its use). The location tracking system functions as a sensor, capturing the player's location and delivering information accordingly. A player interacts with the game tasks by answering a reflective question or providing a rating of the story and place for which they receive appropriate rewards. Responses to questions are marked as pending until approved via a moderator app. Each story is categorised using a standard set of keywords, so users can filter POIs accordingly to follow stories that match personal interests. Based on their interactions, players win game points, badges and rewards for their avatar ( – bottom middle). They also have access to a journey log where they can, at any time or place, review their discoveries and interactions.

Figure 1. Screenshots from CrossCult:City App (top left) birds eye map view, (top middle) navigational clue, (top right) story window with title and media, (bottom left) reflective question and user responses (bottom middle) achievement (bottom right) my journey.

We used the cloud-based solution from Mapbox to serve the underlying Map that was integrated into the interface. We played around with a number of different mapping styles and we finally settled on customising an existing MapBox cartographic style called ‘NorthStar’ by Nathaniel Slaugther (see ). This map style was inspired by historical nautical maps – but we felt that the look and feel of it aligned with the goals of the app. The recessive colour palette provides supported the visual hierarchy on which to display the POIs. To adapt it so that it was more appropriate for a location-based game we looked to Pokemon Go for inspiration where we made the roads wider and added a road casing at the local scale. We then added textures to the background landscape to enhance the visual impact and emphasise the parks, then we removed the contour lines as these were not necessary for moving around at a street scale and we were keen to avoid visual clutter.

3.2. Defining reflection

The game was designed to support reflection on social history. But reflection is a complex and often intentional activity that develops from a simple initial reaction (often in the subconscious) as a response to stimuli. So in the App, the different interactions with the city and the digital were designed to be the stimuli. This initial reaction can then develop into more complex and intentional thinking that engages higher order cognitive and affective process, which may or may not result in learning. So the question is how affective is the App in engaging these cognitive processes. Faced with the complexity of definitions for the term reflection, we decided to retain a broad definition. One that encompasses our emotional reactions (such as ‘I like/dislike’), the recollection of old knowledge or personal memories (comparing now and then), the discovery or search for information and going as far as the elaboration of new ideas built from new information. In the App, we consider reflection to occur if participants act upon different information to synthesise and evaluate it. Reflection is, thus, often driven by experiences that allow us to absorb (engage our senses), do (undertake an activity) and interact (i.e. socialise) (Wertenbroch and Nabeth Citation2000), this framework was used to categorise our findings. Furthermore, when we reflect we look for commonalities, differences, and interrelations beyond elements and link them to our own experiences. This supports the development of different types of thoughts. Surbeck et al. (Citation1991) distinguish between: (1) a reaction (commenting on personal feelings), (2) an elaboration (comparing with other experiences, other theories or positions), and (3) a contemplation (self-reflection associated to personal insights allowing one to situate oneself in relation to one's knowledge and to question that knowledge). We used these notions to evaluate the responses (user-generated content).

The real challenge is to determine if someone or something (a device or an application) can encourage people to think or reflect, and can location-based apps be designed to provoke thinking and reflection? Literature shows that thinking is a process often triggered by the subject themselves (Giordan, Citation2017). In research studies on reflection it is acknowledged that the different forms of reflection and its companion action of thinking are traditionally nurtured through different ways, which engage with others; by talking, questioning and confronting helps trigger and stimulate reflection (Hatton & Smith, Citation1995). Traditionally, these reflection processes are elicited using reading, writing, oral interviews, writing tasks, action learning and the like – which must be reimagined in the context of the design of a location-based game.

Therefore, the design of the App was to draw players into the experience using emotions, personal interest and gamification, and included activities, tasks and interactions for the citizen. To achieve this, the app set out to stimulate reflection with the city using a number of different stimuli and interactive mechanisms to tap into these triggers:

Geo-located discovery of cultural heritage in the city;

Freedom of movement, to discover new POIs;

Establishing increasingly deep thought processes:

o Motivating users to discover stories using clues and points on a map;

o Creating new knowledge or affirming existing knowledge by reading and thinking about short stories;

o Encouraging an emotional reaction and an expression of interest by asking players to rate a story;

o Eliciting connections to other users experiences and opinions by adding a comment to a question

o Provoking and confronting the opinions of other users;

o Co-creation of local knowledge about the city through the creation of personal stories;

o Use of gamification processes to spur the player through these steps.

The aim of the reported evaluation goes beyond a traditional user study in usability engineering and moves towards appraising the embodied experience of the participant – attempting to discover what they were really thinking about as they play and offer an understanding of the value of different types of interactions in the process of encouraging reflection on history. Thus, we define our research question as: Can an LBG be designed to stimulate situated reflection on history?

4. Evaluation method

To judge if an LBG can stimulate reflection on history, we have to understand and identify the elements of reflection that result from the intellectual journey of the participant. How can we evaluate this construct when it is something internal and individual to each participant? Traditional practices such as questionnaires or the examination of the mobile phone logs are not adequate tools for exploring people's thought processes. Indeed, evaluating the application simply by observing the traces left by users (visit time, stopping points, interaction with functionalities, etc.) would be insufficient, as they would fail to tell us what people were really thinking as the participants.

Instead, we had to develop a new or modify an existing evaluation methodology that would enable us to trace the intellectual journey of the citizen when they interacted with the App. Both museum studies and computer science had promising methods, namely Think Aloud – walking protocol and the Remind study protocol developed by Schmitt (Schmitt, Citation2012). The Remind museum protocol evaluates the goals of the participant experience in more depth to traditional user studies. The protocol aims to understand if audiences create meaning during their journey through an exhibition. Whilst the Think-aloud protocol asks participants to say what they are thinking about as they experience the App. We chose the two study protocols for pragmatic reasons – the Remind protocol was lengthy to conduct and resource intensive so it was not viable to conduct across multiple sites in different countries.

To achieve our evaluation goal we combined interview transcripts, think aloud transcripts and user-generated content from the participants’ experience. The project obtained ethical approval from the University of Luxembourg's ethics committee.

4.1. The adapted remind protocol (Luxembourg)

The Remind protocol describes the visitor experience of museum exhibitions along different cognitive and physical dimensions, through video and sound recordings taken through special glasses with an integrated video camera (). Then they visit an exhibition and the visit is stopped after 30 min and participants are asked to review and describe the film of their visit. The method is based on the theory of enactment (Schmitt & Aubert, Citation2017). According to this theory, Schmitt suggests that revising the film of a lived experience sets in motion the same neural networks as the experience itself: the interviewee does not see the experience again, they live it again. This process helps them to describe the process more deeply.

We applied the Remind methodology to the Crosscult:City App, evaluating the potential to encourage reflection on history, by equipping participants in Luxembourg City and Belval with an eye tracker, and let them visit the city using the App. After 20–30 min of open exploration (to observe which features are used or not), we then asked them to use all the features of the application in front of a specific POI (always the same to minimise the effects of differences between POIs). Then we stopped the visit and asked them to watch their film of the experience. We asked them to describe their experience as they watched the video. The subsequent interview transcripts were analysed according to a set of predefined codes.

4.2. Description of participants

Thirteen people volunteered to test the application with the Remind protocol in Luxembourg and Belval. We used a snowball method of recruitment using the researchers’ social and professional networks. This means that whilst this sample (in terms of quantity or composition) is not representative of the Luxembourg population, or of users of geolocated application, it is still a valuable cohort for investigating reflection in our App. Seven people tested the application in Belval and six in Luxembourg City. There were six men and seven women, 10 of the participants were between 35 and 44 years old. All had high levels of educational attainment (bachelor's degrees or higher). Six believed they knew the places where they are trying the app well and seven said they had an emotional attachment to the places. Five of our participants are cross-border workers and 8 lived in Luxembourg. From the perspective of technology, only 4 said they are very open to trying new apps whilst 9 had no experience of playing geolocated games.

4.3. The think-aloud protocol (Malta)

The Think-aloud strategy was used in Valletta, Malta. It involved the recording the (re)actions of the respondents and their thoughts. Participants were asked to verbalise out loud what they are thinking about as they experience the App. These open-ended interviews were transcribed and analysed with thematic content analysis as per the analytical method described below and inline with the Remind experiment.

4.3.1. Description of participants

Of the nine participants, eight identified as male and one as female, all had a bachelor's degree or higher. Six of the participants stated their ability to use mobile maps for navigation was very strong and five of the nine stated that they are willing to try new digital applications and try them systematically. Of the nine participants, seven stated that they had played geolocated games on their mobile. This group was also younger in profile than the participants of the Remind protocol. All of whom were between 20 and 34. Still by no means a representative sample but as the demographic characteristics are different, it makes our sample more diverse, which helps to find further supporting evidence.

4.4. Analytical method

To analyse both sets of data we modified the coding strategy proposed by (Schmitt, Citation2018) by adding to and removing some codes.

Representation: identifies what is considered by the respondent in the environment, (for example, it can be the museum object, a feature in the app, or a building in the city) after Schmitt (Citation2018).

Engagements (ENG): type of engagement that is the focus of attention (Representation). It is often an action verb (to look, do, try, activate, turn, click …). after Schmitt (Citation2018).

Emotional reactions: corresponds to an explicit emotion expressed by the participant during the experience (as positive, negative, neutral).

Types of reflection: describes the part of the intellectual journey that corresponds to the concept of reflection.

Localisation: the specific location of where the unit of experience is occurring; specifically, are people walking or have they stopped.

Form of reflection: describes if the thought is a reaction, elaboration or contemplation (Surbeck et al., Citation1991).

Interactions: description of the activity interactions that participants completed (e.g. response to a reflective question).

5. Findings

To answer the research question, ‘Can a LBG be designed to stimulate situated reflection on history’, we first consider how experiences can stimulate reflection. We noted earlier in the paper that reflection is often driven by experiences that: (1) allow us to engage our senses and support an emotional response, (2) facilitate our participation in an activity or task and (3) encourage interaction which in the case of our app we consider as interactions with places, within historical topics or with each other (Wertenbroch and Nabeth Citation2000).

5.1. Which features engage emotions and do they support reflection?

5.1.1. Can the app trigger an emotional response?

We begin by exploring which parts of the experience trigger an emotional response. The transcripts provided evidence of emotional responses that were both positive and negative. We captured two types of emotional reactions. Those that are part of the intellectual journey of reflection and those that are associated with the participant's satisfaction with the application. In the Remind experiments we observed 179 explicitly expressed emotions; 86 were positive (48%), 80 were negative (45%).

The positive emotions were predominantly associated with: acts of discovery (e.g. information, artworks, places); the process of connecting places to personal feelings/previous knowledge/ memories; the activity of questioning either questioning myself or the app. Participants expressed emotions such as interest, happiness, feelings of fascination and curiosity. For example, P03, Belval [translated from French]: ‘I’m interested, concentrated … I’m learning cool things, that I did not know … that the gray on the facade represents the dust of industries. So, you see, I learned things … . or E13.Belval.. ‘but I found it quite fun to look for the, you know, to have places of interest to go to and you had to get inside them to find out the story so I was interested by this point’.

The negative emotions expressed were often occurring either, at the end of the experiment predominantly articulating frustration or, they were expressing a reaction in response to the reflective questions in the app. Frustrations were predominantly the result of technical issues or the result of the limitations of GPS (i.e. loss of accuracy in where you were). These types of issues resulted in negative emotions, which blocked the process of reflection. Therefore, the emotional reactions to the application had two consequences (1) emotions influence the reflection journey especially positive ones that are the result of place discovery or processes of connecting places to personal feelings or previous memories or participative features but (2) negative emotions explicitly expressed about the app usability break this journey.

5.1.2. Does the activity of rating stories in the App elicit an emotional response?

The most mature version of the app asked participants to rate a story associated with the POI. The average story score rating is updated as a ‘real-time’ feature of the navigational clue. Combining the user logs with the participant transcripts we could determine that the act of rating a story was indicative of the extent to which the participant was interested in the story, 5 stars denoted a very strong interest and 1 very little interest. A total of 19 POIs were discovered with 66 individual ratings for which 14 of the 19 points of interest had an average story rating of 4 stars or above.

We observed that rating a story triggered an emotional response based on if the story aroused attention. The interaction supported the expression of a fleeting emotional reaction. There were odd occasions when participants thought more deeply during this activity, which is illustrated by P04 who awarded five stars to a story, saying after it was rated, ‘It's about language and I think this is an important issue’. This suggests a link between the rating and the story where the participant is thinking about the story and its importance to themselves. The rating seems to be influenced by the strength of their personal opinion on the topic. Thus, the act of rating a story encouraged participants to think about the extent to which the story(s) captured their attention and sparked their curiosity.

5.2. Which features support interactions that led to reflection

The App was co-designed to encourage different types of engagements, which were expected to contribute to the participant's intellectual journey of reflection on social history (for more info see Jones et al., Citation2017). From the interviews, we categorised a total of 420 different engagements during the Luxembourg experiment where participants explicitly told us what they were doing. The types of engagements were talked about included Reading (25%), Looking at (20%), Writing (10%), Thinking (10%) and Walking (9%).

5.2.1. Does geo-located discovery using location-aware technology support the process of reflection?

Engagements classified as looking activities were always in relation to the map/city – which led players to think about the area and decide where to go. The act of marking POIs on a digital map encouraged participants to think about where they are going and how they will get there (obviously). The demarcation of POIs on a map had the ability to nudge participants and draw them into the experience and indicate what they should discover. Illustrated in the experience of P03 (Luxembourg). … ‘so I remember that I checked the map quickly and saw the dots a little bit, and I know the area. … So I saw that there were a lot on Kneddeleur sorry not Kneddeleur, Place d’Armes. So I went there’. The cartography and spatial distribution of the POIs encouraged participants to reflect on what they already knew about the area and where they should go. For some it also led to a reflection on what route they should plan, As demonstrated by participant P11 (Belval, Luxembourg) ‘I think at one point, I zoomed out to see where all the other stories were and then I made a sort of path for myself … ’. They were thinking about the map and the spatial distribution of the POIS formulating informal routes through the built environment combining local knowledge with the POI placements.

5.2.2. Does reading and thinking about short stories in situ support reflective thinking?

The act of providing stories to read combined with the personal motivation of players to discover new information supported the reflection journey, and can result in participants feeling that they were learning new things. The activities of reading and thinking were naturally closely connected. Participants often reflected about the place in relation to what they had read in the story texts. For example, P04 ‘And then, I was just looking at the facade and thinking about what was written there [the story] and looking at the building’. Reading was motivated by the goal to acquire information or discover something new. For example, P04 Belval: ‘the next one about the library, which was interesting about the facade and I didn't know any of that so I found it quite informative’. In some instances, the act of reading a story led participants to make connections (by connecting text with previous experience/ memories or question the connection between the place and the story). For example, P10 (Luxembourg):

It's something about Michel Rodange and the Luxembourgish language … His poem ‘the fox’ … There, the link is clear … Between the monument and the story. I found it interesting. But for other people who do not know Luxembourg, it's [also] interesting … what this monument is about.

5.2.3. Does the feature of connecting points of interest and stories on a map encourage participants to reflect on social history?

When designing the example stories to be included in the application, we wrote two types of stories based on our findings from the board game (Jones et al., Citation2017) ones with metaphorical links to POI locations (indirect connection) and ones with explicit links (direct connection) to the POI location. We chose this approach to discuss migration in the city context, as it was not always possible to find explicit locations related to this topic, so we used buildings or locations representative of the period. This was particularly true for Luxembourg City. In Belval, stories had explicit links to the buildings and locations (associated with art, architecture and urban transformation) whilst in Valletta, Malta the connections were more mixed with both direct and indirect linkages between story and POI.

5.2.4. Does the act of reading a story in situ that is explicitly connected to a POI location support reflection?

When the link between POI and stories was explicit, i.e. the story was talking directly about the social history of the building/place where people were standing, it was more likely that participants continued their intellectual journey of thought/reflection. Participants were more likely to confront an idea from a story that was directly linked to a place because they were able to mull over and make sense of the links, building upon the physical and hidden elements. The result was the discovery of new information.

In the Luxembourg experiments, only one POI discovered had a direct link and in Belval there were 5. It led to the creation of connections as participants linked the place and/or the story they had read to personal knowledge, memories or opinion. This was observed in both experiments (Remind and Think Aloud Malta). For example, in encountering an art installation and reading a story about its explanation P11(Belval) stated, ‘it is a natural sort of sun clock to function. To me that's so interesting when art isn't just a painting when it's something that has a meaning that has a change with the light or the sun’ or P07 (Luxembourg),

In a multilingual community/ country and the thing I was thinking for me was, … for me it was personally important to learn the language of the country where you live but also to remind you of your roots your language, mother language is very important when you want to talk about your feelings about your emotions it's the straightest way …

This App feature supported a positive experience, which in turn is more likely to lead to a thought that is not only about the App, its form or style of content but one that encourages the acquisition of new information.

5.2.5. Can indirect connections between a POI and a story support reflection?

Indirect connections between locations and stories most often left participants feeling a sense of confrontation and conflict. The result was a cognitive mismatch between their perception of what the app was for (i.e. to discover historic content about the city and its building) and the type of content that they discovered (stories of historical migration and culture). This was particularly the case in participants that did not have any prior experience with LBGs and was less open to trying new technology. They were expecting stories associated directly with the building. For example, P01 Lux:

I get to the Chamber of Deputies and the app doesn't explain the Chamber of Deputies to you … I’m in front of an administration and a body that governs the country and they don't explain to me how the country is governed and how it works.

Here the participant is clearly frustrated because the content does not match their expectations – they wanted something more akin to a traditional tourist experience. Thus, for POIs that had historical significance in their own right participants felt challenged by this indirect link of place and subject, resulting in a disconnection in the participant experience and a break down in the intellectual journey.

During the Malta Think Aloud experiments, the participants, who had in general a younger profile, and had much more experience playing LBGS were less troubled by the indirect connections. For example, In Valletta a POI located at Europa House did not discuss the EU as an organisation but described the myth of Europa and its symbolism in European Identity. So whilst not presenting a story specifically about the building, the connection between the place and the story was implicitly created by the participant as demonstrated by P02 (Malta TA):

it's nice to see how these kind stories like the myth of Europa ties into the European Union and how it becomes the Actual European Union and the European House. I think that is sort of like the missing link but then we did not learn anything about European house but it is a nice touch, it sort of like It sort of helps you think about your place and this whole burden why you are here and makes you think a bit more than just waltzing through and taking pictures of good looking building.

Here the unexpected story provided a positive experience. The participants are making a connection between the place and the story that provokes thinking about their personal situation and traditional experiences.

What we can understand about these different types of content is that indirect links between stories and POIs need to have a note of explanation on why this location is chosen to help encourage participants to make the connection. Furthermore, the App design needs much stronger game elements to draw upon the imagination for this type of content and justifies the abstract indirect connections.

5.3. Which features support participation?

The App was designed to encourage participation in two main ways: (1) to answer a question connected to the social history topic of the story whilst being in place or (2) to contribute their own personal located story.

5.3.1. Can participation by answering a question connected to a discovered story lead to reflection?

During the process of writing an answer to the question participants were expected to make connections to their own experiences, stimulated by discovering the content in situ. But is this really the case? Can writing a comment in response to a question on a social history topic whilst being in the city truly support the development of reflection? We analysed the comments that people wrote in responses to the questions to understand the form of the reflection.

5.3.1.1. Form of reflection

First, we investigate the form of reflection using a framework proposed by Surbeck et al. (Citation1991) who studied journal writing to determine if it encouraged thinking. We conducted an in-depth examination of the contributions using the three categories of the framework to identify reactions, elaborations or contemplations. Reactions are classified as an initial contribution to the question. They can involve expression of a positive or negative feelings or reporting upon a personal opinion. When participants’ contributions were elaborations, they added an explanation of their initial reaction or offered examples by making links to other information. A contemplation represented a deeper more reflective thought and incorporated both a reaction and elaboration which then expressed thinking about personal or social issues.

Across the two experiments, participants contributed 78 comments. On average, they were 14 words long, but some comments were more lengthy, with the maximum length of a comment being 63 words whilst the minimum being a 1-word response. We were able to classify the comments to discover that 44% of the contributions were reactions, whilst the location-based game supported elaboration 20% of the time and deep contemplative thought was also less common and identified in 20% of the contributions. This shows that despite their short length, more than half of all contributions represented a thought deeper than merely a simple reaction.

Contemplative reflective thoughts most often expressed comparisons and connections between what participants had read, observed in place and their existing knowledge they already knew and contemporary social issues. For example, in response to a question about the architecture and the Urban Forest on Belval campus P11 commented,

It was built as a campus and a place where work is most valued. It doesn't fit residents that well in my opinion, which is why I moved out. Even though the industrial heritage is important, there is no nature or greenery to break that up.

The participant states their reaction to the question, elaborates on their thought and then links their thought to a social issue (lack of green space). Their pre-existing thoughts and opinions are brought into the participants’ consciousness at a particular point in time and space because of their engagement with the App.

Less commonly, some participants contributed elaborate or contemplative reflective thoughts and did so consistently for more than one question and POI. For example P03:

Paying homage to the past through the use of red may also connotate spilled blood of past workers, also to be paid tribute to’ or ‘Historical facts about the furnace are interesting but, for me the most important question is ‘why.’ Why was the furnace so interesting to the Chinese? Couldn't they just learn about the design and technology and build it themselves?.

Participants who contributed the most comments were also the ones that compared the most and made the most connections between pre-existing knowledge and discoveries or different elements of the application. This suggests that they were more engaged in the participative aspects of the app.

5.3.2. Can the creation of content such as writing geolocated stories in situ result in reflection?

During both experiments, a few participants created their own complete POIs (navigational clue plus a story) which they could do so in situ via the App.

5.3.2.1. Writing geo-located stories in place

Participants were asked to try and contribute their own stories during the Remind protocol but many found the process complex and the functionality hidden. The feature was simplified during the Malta TA experiments and three participants found the feature without prompting and shared their stories – during which process they engaged in deeper, more thoughtful reflection. We observed four types of reflective thought processes:

Creating connections between place, the social history topics (migration) and their prior knowledge.

Creating connections between place, the reflective topic (social integration) and personal memories and feelings

Creating connections and comparing – linking between the city, perceptions of place, their personal memories and personal feelings (hopes for the future)

Creating connections and comparing – linking between the city, their personal memories and personal feelings (hopes for the future)

Deep reflection occurred because of the participants authoring, writing stories where they created connections and comparisons that build upon links between place, history and personal memories/feelings/ knowledge.

6. Discussion

The premise behind the App was to use location-based game play to stimulate public reflection on a variety of topics such as migration, art and architecture, industrial heritage, language and identity, etc. We imagined that through the promotion of citizen participation in a playful and thought-provoking game it would be possible to contribute to a collective reflection on history.

The evaluation provided evidence that when participants were involved in their intellectual journey they engaged in interactions associated with historical information discovery and the exploration of places. This journey stimulated reflection processes connected to the historical topics and the city itself (which is a manifestation of social, cultural and historical processes).

The intellectual journey we observed was the result of the process of finding and discovering content in the city, reading the story, thinking about if the story interested you, and then reading and responding to reflective questions on the topic of the story. This process encouraged a train of thought that helped place the topic in participant's consciousness and encouraged participants to think about their own personal experience, perspectives, and memories and connect them to topic. This process brought the topic and the city to the forefront of people's mind (even if for a short time) and led to a re-familiarisation with history and the city/site that would otherwise not have been part of the participant's everyday city experience.

7. Conclusion

Evaluating LBGs is not an easy task. This study used a blended methodology combining the Remind protocol from museum studies with the Think-aloud protocol from user studies in computer science and the qualitative analysis of user-generated content. Using a systematic coding methodology, we were able to determine that a Location-Based Game can stimulate reflection on social history. The results of the evaluation indicate that App experiences need to incorporate the three following notions: firstly, they should engage our senses and support emotional responses by supporting the free exploration of the city and discovery of in situ content together with the completion of quick tasks such as rating stories. Secondly, they must facilitate participation in an activity or task that draws upon our personal experience. Thirdly, they need to encourage direct interactions with the city or other players through the co-creation of personal content. These types of features support the intellectual journey of participants and lead to reactive, elaborate or contemplative thought. Whilst the depth of reflection that is triggered depends on three attributes converging: the social history content, the individual locations and the personal connections players are able to make. Our LBG was able to, albeit in a diluted way for some participants, reshape our place-based experience through processes of re-familiarisation that supported reflection on social history.

Acknowledgements

The CrossCult (www.crosscult.eu) project refers to the Pilot 4 application called CrossCult:City. The following pilot 4 team members contributed to its design, development and parts of the evaluation process: Louis Deladiennee, loanna Ykourentzou, Céline Schall and Antonios Liapis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Catherine Jones

Catherine Jones is an Assistant Professor in Digital Geography at the University of Luxembourg since 2018. Since the beginning of Sept 2020 she holds the position of Director of Studies for the Master programme in the Geography and Spatial Planning Department. She has a PhD in Geographies of Health and a Master of Science in Geographical Information Science (2003), both from University College London. Since the start of her career in GI Science and Digital Geography she has been interested in the public use and access of geographical information. Particularly in the domains of societal health, education, cultural heritage and history as well as to investigate new ways in which to explore individual and collective understanding of place.

References

- Cashman, S., & Phelps, C. G. (2009). Mobile Games. Digital Cityscapes: Merging Digital and Urban Playspaces. Peter Lang.

- Connerton, P. (2009). How modernity forgets. Cambridge University Press.

- Crawford, M. (2012, August). Urban Interventions and the Right to the City. The Journal of the American Institute of Architects, Venice Biennale. https://www.architectmagazine.com/Design/urban-interventions-and-the-right-to-the-city_o.

- Crosnier, H. L., & Vidal, P. (2017). Le Rôle Du Numérique Dans La Redéfinition Des Communs Urbains. Netcom. Réseaux, Communication et Territoires (31-1/2), 09–32. https://doi.org/10.4000/netcom.2598

- Elden, S. (2005). Contributions to geography? The spaces of Heidegger’s Beiträge. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 23(6), 811–827. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/d369t

- Giordan, A. (2017). Apprendre!. Belin.

- Hatton, N., & Smith, D. 1995. Reflection in teacher education: Towards definition and implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051x(94)00012-u

- Jacobs, J. (2016). The economy of cities. Vintage.

- Jones, C. E., Liapis, A., Lykourentzou, I., & Guido, D. (2017). Board game prototyping to co-design a better location-based digital game. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI conference extended abstracts on human factors in computing systems, 1055–64. ACM, Colorado.

- Kitchin, R. (2014). The real-time city? Big data and smart urbanism. GeoJournal, 79(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-013-9516-8

- Relph, E. (1976). Place and placelessness. Vol. 67. Pion.

- Saker, M., & Evans, L. (2016). Everyday life and Locative play: An exploration of foursquare and playful engagements with space and place. Media, Culture & Society, 38(8), 1169–1183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643149

- Schmitt, D. (2012). Expérience de Visite et Construction Des Connaissances: Le Cas Des Musées de Sciences et Des Centres de Culture Scientifique. Université de Strasbourg.

- Schmitt, D. (2018). L’énaction, un cadre épistémologique fécond pour la recherche en SIC. Les Cahiers du numerique, 14(2), 93–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3166/lcn.14.2.93-111

- Schmitt, D., & Aubert, O. (2017). REMIND: Une Méthode Pour Comprendre La Micro-Dynamique de l’expérience Des Visiteurs de Musées. Revue Des Interactions Humaines Médiatisées (RIHM)= Journal of Human Mediated Interactions, 17(2), 43–70. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01575010

- Silva, A. d. S. e., & Jordan, F. (2012). Mobile interfaces in public spaces: Locational privacy, control, and urban sociability. Routledge.

- Surbeck, E., Han, E. P., & Moyer, J. (1991). Assessing reflective responses in journals. Educational Leadership, 48(6), 25–27.

- Wertenbroch, A., and T. Nabeth. 2000. Advanced learning approaches & technologies: The CALT Perspective. The Center for Advanced Learning Technologies, Web Site, Retrieved on February 27: 2010.