Abstract

This article aims to envision more just visual representations of Black spatial collectivity. In light of transformative work in critical cartography and recent turns to narrative cartography, digital mapping has arguably come to offer an opportunity for radical and democratized visualizations. However, the historical and contemporary anti-Blackness of mapping urges caution. Moreover, prominent critical cartographic urges to eschew normativity risk advancing diminished and distorted representations of historically Black communities. In turn, this article questions the extent to which visually countering the ongoing anti-Black work of dominant maps (e.g. erasure of Black communities) might avoid altogether appropriating the medium. Presented are animations created with audio clips from oral histories collected in rural Southern (US) communities. Created in collaboration with a professional animator, these brief animated clips do the work of countering historic erasure without reinforcing the hegemonic legibility of dominant cartographic productions.

本文旨在更公正地对黑人空间集体进行视觉表达。根据批判制图学的变革性工作和近来叙事制图学的转变,数字制图有争议地为激进的、民主化的可视化提供了机遇。然而,历史和当代的反黑人制图令人警惕。此外,批判制图学对规范的明显回避,有可能促使对历史黑人社区的表达的减少和扭曲。针对抵制反黑人的主流地图(如删除黑人社区),本文质疑了其在多大程度上能避免完全占用媒介。本文展现了美国南部农村社区口述历史的音频剪辑动画。与专业动画师合作,在不加强主流地图产品的霸权易读性的情况下,这些简短的动画剪辑抵制了对历史的抹杀。

Este artículo apunta a imaginar representaciones visuales más justas de la colectividad espacial negra. A la luz del trabajo transformador en cartografía crítica y los recientes giros hacia la cartografía narrativa, el mapeo digital indiscutiblemente ha llegado a ofrecer una oportunidad para visualizaciones radicales y democratizadas. Sin embargo, el carácter histórico y contemporáneo anti-negrura del mapeo demanda cautela. Aún más, lo cartográfico crítico prominente insta a rehuir el riesgo de la normatividad fomentando las representaciones disminuidas y distorsionadas de comunidades históricamente negras. Por su parte, este artículo cuestiona la extensión con la cual oponerse visualmente al actual trabajo anti-negrura de los mapas dominantes (e.g. borrón de las comunidades negras) que podría evitar del todo apropiarse del medio. Se presentan animaciones creadas con clips de audio tomados de historias orales recogidas en comunidades rurales sureñas (EE.UU.). Creados en colaboración con un animador profesional, estos clips animados de corta duración hacen el trabajo de disputar el borrón histórico sin reforzar la legibilidad hegemónica de las producciones cartográficas dominantes.

Key Words:

Digitally innovated geospatial tools have arguably come to offer opportunities for more just representations (Crang Citation2015; Offen Citation2013). Projects like Motor City Mapping and Detroit Food Map exemplify the purchase of such representations, which are shaped with input from on-the-ground perspectives in defiance of hegemonic map-making traditions. These digital projects support claims that the yet growing practice of creating StoryMaps and other media-embedded sorts democratizes the means of making what we consider cartography (Caquard Citation2013; Corner Citation2011). What, then, is there to currently say for the cartographic enterprise at-large’s legacy of racism? Further, what possibilities are there for minding the alterity of Black spatial collectivity given the potentials of digital media beyond the whole of mapping? In the summer of 2016, academics from around the United States gathered to address such questions for the NEH Institute on Space and Place in Africana/Black Studies.

Broadly speaking, we came together at the Institute out of concern for how African and African diasporic spaces might be better represented via digital technology and media. We shared our research and listened to trailblazers who presented projects like The Virtual Harlem Project, which uses immersive virtual reality to represent the Black cultural mecca Harlem in the 1920s-30s (Carter Citationn.d.; Johnson et al. Citation2002). With a focus on space and digital technology, conventional geospatial technology took a central place in the collective toolkit of the institute participants. Presenters like Judith Madera, author of Black Atlas: Geography and Flow in Nineteenth-Century African American Literature (Citation2015), furthered this theme. As a consequence, one of three weeks was dedicated largely to learning how to better use different GIS technologies. Such a focus on the map reflects a trend in digital humanities undertakings and “an emerging focus on the role that geospatial technologies can have in engaging with the history of race across the African Diaspora” (Kim Citation2017, 1). However, a focus on GIS gives pause considering how anti-Blackness has been advanced via geospatial representations such as redlining (Lipsitz Citation2011). Indeed this function of mapping continues as GIS contemporarily empowers violent state terror against Black communities vis a vis the likes of predictive crime mapping (Jefferson Citation2018).

With a critical need for disempowering maps as forces of racial violence and inequity, more critical uses of geospatial technology like those advanced by some Institute participants are critical. For instance, The Ward uses digital mapping to enliven the maps in W.E.B. Du Bois’ The Philadelphia Negro, which demarcated the economic diversity of the city’s Seventh Ward, a vibrant Black community (“The Ward: Race and Class in Du Bois’ Seventh Ward” Citationn.d.). Alongside the maps, the public history project aimed at high school students presents oral histories and a board game, which introduces audiences to Du Bois’s rigorous analysis, which itself sought to problematize myopic, oversimplified understandings of Black communities.

The Ward and similar digital mapping projects are important for informing the public of histories and places at risk of being forgotten. However, in this article, I broach the inherent limitations of geospatial technology for visualizing narrated and contested sites of Black collectivity even in light of recent critical cartographic engagements with narrative (Caquard Citation2013; Wood Citation2013). My analysis emerges from the conclusion of the Institute and follow-up workshop that set two tasks: (1) crafting a book project reflecting our collective efforts and (2) more generally, identifying the ground that holds our multidisciplinary work together. We named both “Black spatial humanities.” I aim to consider how such a dual intellectual project, Black spatial humanities, might be more critical of geospatial technology and its limitations. I then propose digital animation as one potential counter-mapping alternative specifically for narrated sites of Black collectivity that have been historically obscured and mismanaged via geospatial technologies.

BACKGROUND

To substantiate inquiry, I turn to animations created in collaboration with a professional animator. These brief animated clips feature oral histories from rural, historically African American communities in Piedmont North Carolina, which were the focus of the Southern Oral History Program’s Back Ways project. The visualized communities were built around back ways or historic wagon roads that led to and from family farms. Despite their importance, many of the paths were never shown on official road maps. Accounts of them are embedded in oral history interviewees’ stories of growing up as well as in passed down genealogical anecdotes. These stories and anecdotes refute the blank space of dominant maps that omit the wagon roads. In critical cartography, a growing interest in the narrative-cartography relationship offers some guidance for reckoning with such oral counter-mapping (Caquard Citation2013; Leszczynski Citation2015; Maharawal and McElroy Citation2018). However, while this work may offer allied support for Black spatial humanities, the back ways narratives show that objects that counter maps need not be some alternative versions of map themselves.

As I hope to make clear, practitioners of Black spatial humanities have an opportunity to clarify the distinction between the scope of representable space and the established boundaries of critical cartographies. Black spatial humanities and its digital representations of space could manifest via means of representing space beyond cartographic visualizations as well as critically assessing the purchase of cartography. As is well-known in geography, dominant constructions of maps arose in the 1500s to help growing Western empires control wide swaths of territory. Critical cartographers theorize the ongoing role of the map from the scale of global empires to that of local governments (Pickles Citation2004; Wood, Fels, and Krygier Citation2010). Indeed, cartographic representations are never neutral, but always at the service of the state.

Among critical cartographers and GIS researchers alike, narrative has been identified as one way to decenter seemingly neutral representations of space (Caquard Citation2013; Kwan Citation2008; Kwan and Ding Citation2008). Such work aligns with core suggestions in Black geographies literature, a likely locus of Black spatial humanities thought (McKittrick and Woods Citation2007). However, there are pertinent differences between critical cartography and Black geographies when it comes to representations of space. While core critiques of cartographic approaches find fault with the dominant maps’ normativity (Knowles, Westerveld, and Strom Citation2015; Wood, Fels, and Krygier Citation2010), Black spatial humanities has the potential to recognize the normativity of Black spatial representation as a matter of promoting radically different understandings of space—ones where narrated Black collectivity predicates place rather than cartographic positioning. This article examines the potential importance of “regularity.” Rather than eschew all order, Black productions “reconfigure classificatory spatial practices” (McKittrick and Woods Citation2007, 5, emphasis added). In meditating on non-cartographic representations of Black spatial productions, this article therefore also takes up the task of “embracing the normative” (Olson and Sayer Citation2009) in consideration of Black spatial humanities.

The argument that I advance begins with the premise that Black life’s demarcations of space with narrative have been subject to some normative regulatory forces born out of alterity. The preservation of these narrative demarcations depends on such regulation. As detailed by Black geographies scholars such as, Clyde Woods, Katherine McKittrick, and Angel David Nieves, critical study of Black space must account for the practical rigidity of humanistic processes such as storytelling to counteract under-developed analysis, particularly those that simply enumerate the physical conditions of Black neighborhoods (Woods Citation2002).

THE MEASURE OF BLACK GEOGRAPHIES

The interdisciplinary field of Black geographies focuses on the production of space by narrative and lived experience. Its contemporary framework is often traced to the work of Clyde Woods and Katherine McKittrick, both of whom have described their work explicitly as “Black geographies” (McKittrick and Woods Citation2007). I focus on Black geographies here through the work of Kathryn McKittrick, Clyde Woods, and Sylvia Wynter (Citation2006, Citation2000), as well as work included in and resolutely followed by their Black Geographies and the Politics of Place text. Work in the interdisciplinary field focuses on the collective emplacement of Black people in contexts of disenfranchising dominant and state-led economic or infrastructural development (Inwood Citation2011; Woods Citation1998). Such development, like urban renewal and interstate highway building, intensifies uneven participation in modernization along racial lines (Bullard et al. Citation2007; McKittrick Citation2011).

Modernizing state development and planning facilitates new rationales for uneven participation, or the disproportionate burden of environmental harms. Meanwhile, the metrics of modernization ignore the vitality of Black communities. The too-frequent result is that Black communities appear suited for unwanted byproducts of modernizing development including ultimate demise. This is seen in countless cases of waste facilities plotted in historically Black neighborhoods (Pulido Citation1996; Woods Citation2002). From planners’ views, Black communities often appear as uniform sites of dilapidation and pathology rather than places of community, family, and history (Pulido Citation2000, Citation1996). Black geographic scholarship provides a less morbid view of these communities and those living in them.

Black geographies fosters a growing recognition that historic Black emplacement implicates collective refutation of the West’s racial misnamings (Hawthorne Citation2019). Disseminated traditions, stories, and ways of navigation draw forth an alternative, self-determined understanding of Black identities are outside of denigrating representations (McKittrick Citation2006; Nieves Citation2007). Black geographies demand we look beyond dominant narratives victimized communities to see the vitality at stake when the state fails to recognize the ongoing importance of historic narrative and lived experience (Woods Citation2002, Citation1998). Rather than translating radical Black geographic spaces into the language of cartography, however radical, we must altogether reconfigure the ways we know spaces to be demarcated and sustained. These ways are hardly outside normative conditions.

BETWEEN PLACE AND NARRATIVE

Critical cartographic work with narrative calls for more attention to history, artistic expression, and subjective experience (Bodenhamer, Corrigan, and Harris Citation2015; Caquard Citation2013; Peterle Citation2018; Tally Citation2014; Wood Citation2013). One part of this complements humanists’ recent reckoning with a historic concern for cartographic representations that has gone without adequate reflection (Offen Citation2013). Other humanists and cultural geographers have joined long-standing critical cartographic explorations of what digitalization and increased accessibility mean for more humanistic visualizations of space (Crang Citation2015; Knowles, Westerveld, and Strom Citation2015). Following the maxim of maps producing place, critical cartography projects consider how the accessibility of online map interfaces, like Google Maps, might allow laymen to “play” with the territories and places wrought by cartographic visualizations (Corner Citation2011; Pickles Citation2004). Concerns with democratization parallel arguments in history suggesting digital accessibility might usher in a welcomed upset of who gets to say exactly what archives are during their digital renovations (Cohen and Rosenzweig Citation2006). Alongside these vibrant, transdisciplinary conversations in journals such as GeoHumanities, there are others reminding scholars to remain mindful of cartography’s fundamental shortcomings even as it attends to more humanistic matters like narratives (Rose Citation2016).

In Rethinking the Power of Maps (Citation2010), “Talking Back to The Map,” Wood et al. lament the failure of public participation GIS (PPGIS) to de-hegemonize the business of mapping: “I’d have to say, despite the high idealism and great goodwill of perhaps all its practitioners, that PPGIS is scarcely GIS, intensely hegemonic, hardly public, and anything but participatory” (160). The text goes on to decry the lack of similarities between PPGIS projects and the counter-mapping work of Debord and The Situationists who embraced emotion while constructing more complete “geographic information systems” based on localized subjective experience. The creation of the Situationists maps, for instance, began with dérives through the city streets of Paris. Eschewing the order imposed by power broking planners like Le Corbusier, Debord created The Naked City map. It was arranged with cutout portions of Parisian maps interspersed with swirling arrows to suggest the subjective and meandering in-and-out flows of derives. The work serves as a reminder that concerns with emotion and subjectivity that are missing from dominant spatial visualizations have not been entirely lost on contemporary geographic visualization, even as they constitute the margins of that particular analytic and empirical examples.

In cultural geography, there is a substantial number of recent and notable methodological undertakings which follow in the tradition of Debord and The Situationists. These are methods empowered by a long-standing reaction to ordering, dominant cartographic representations. They embrace anything-but-abstract outputs. Analyses by Knowles, Westerveld, and Strom (Citation2015) promote “inductive visualization,” which privileges the emotions and narratives of Holocaust survivor testimonies rather than attempting to contort them to fit any sort of conventional GIS visualization. The visualizations take the shape of two-dimensional pictorial and chart-like timelines with no prescribed form. It follows that these visualizations might avoid conforming to what Wood et al. (Citation2010) lambasts as the “normative goal” of PPGIS to “construe the public monolithically, as a people united about ends, if divided over means” (162). This is taken to include work, like Kwan and Ding’s (Citation2008), which makes efforts to humanize GIS with oral history and personal accounts.

Considering the tension between these PPGIS projects and abstract work like the inductive visualization of Holocaust testimonies, I am inclined to question some discursive work surrounding “cartography” for Black spatial humanities. By seemingly assigning “normative” legibility and fixedness exclusively to the likes of maps, counter-projects are potentially left as the makings of fatally incomprehensible visual representations of space. In other words, counter-cartography loses its potential to legibly represent. This critique of cartography then runs the risk of assigning already marginalized perspectives or people as being unrepresentable, the spatial equivalent of those in the margins having “names their captors would not recognize” (Spillers Citation1987, 72). In criticizing PPGIS supporters who tout its legibility to politicians, Wood, Fels, and Krygier (Citation2010) says, “what [the supporters] really mean is that the message has been reframed into the language of regulation” (164). I am inclined to think that for Black spatial humanities, regulation might not be regarded so negatively. Olson and Sayer (Citation2009, 181) argue that much critical geographic work has “become increasingly reticent about making its critiques and their standpoints or rationales explicit, or has softened its critiques, so that in some quarters being critical has reduced to trying merely to ‘unsettle’ some ideas or to being reflexive.” In this sense, “normative” means making evaluative claims via notions of good and bad, flourishing and suffering. I am moved to consider the normative work inherent in the place-charting narratives of the back ways communities and other Black geographies. They have been mobilized repeatedly in efforts to have outsiders readily know of embattled land uses and tenures. In this way, I consider the telling of the narratives counter-mapping, which problematizes the nowhere at all-ness in which conventional maps place Black life with family anecdotes and oft-recounted community sentiments.Footnote1

When I recorded the narratives of the back ways communities, their space-charting qualities were readily apparent. These narratives made the communities at once material and historical, and they have been mobilized in grassroots political fights against local North Carolina governments and in the preservation of the communities themselves. They call for representation that reflects their intelligibility. While visualizations like Debord’s are important and undeniably politically engaged, we must not ignore the allure or comprehensibility of dominant cartographic representation as we attempt to counter it. I do not mean to discount the intellectual projects of Knowles, Westerveld, and Strom (Citation2015) and Wood et al. (Citation2010), in teasing out the flattenings and endless ethical quandaries posed by creating visual representations of space within traditional GIS. On the contrary, I agree with such underlying critique and the “intensely hegemonic” fate of PPGIS “as we know it.” I am weary of even public GIS projects, about which Woods (Citation2002) and McKittrick (Citation2006, Citation2011) offer critiques, and which raise questions about the empirical, positivist nature of mapping that naturalizes, or presents as merely factual, the material conditions of African American neighborhoods. At the same time, I am aligned with the call of PPGIS projects like those lambasted by Wood, which moves us to assess the social justice impacts of counter-mapping in albeit normative contexts. Most importantly, however, I recognize intelligibility as an important motivation for Black spatial humanities though not one for which the holistic alterity of Black productions should be sacrificed.

In the context of the Back Ways interviews, following the edicts of Wood, Fels, and Krygier (Citation2010) might mean over-determining the partiality of some accounts from narrators and failing to mind the ways such accounts are at work to uphold totalizing views and productions of space. If we accept Woods’ (Citation1998) claim that the blues establishes an entire epistemology that challenged a global plantation logic, it stands to reason that it might accommodate worldviews of its own, albeit ones characteristically cast from localized positions (i.e. the Mississippi Delta). Through cadence and melody, the Blues configures all it touches through its doubly critical and “just music” work. By committing ourselves solely to partiality and tensions, we fail to account for that which is not in tension, per se, or that which is creative and unifying rather than confrontational. Such creativity may be subversive yet like the Blues or a personal recount of some back way.

For the digital productions of Black spatial humanities, dualistic thinking (i.e. legibility vs criticality) distorts and discounts the potential variability of abstraction—that is, the abstract is always posited as most dominant and never subversive but always subverted. I wager that the potential of Black spatial humanities is partly hinged on overcoming the prevalence of this dualistic thinking.

PRACTICAL MATTERS AND REPRESENTING THE BACK WAYS

By centering oral histories, the Back Ways project draws from the life stories of African Americans who have lived around historic wagon roads in Orange County (NC) through the twentieth century and onwards. The interviewees weave long road narratives in their personal histories covering birth, school, work, marriage, and the achievement of old age. Though the work of Black geographies scholarship has improved critical knowledge-making practices of racialized geographies of the American South, we do not know how such sites may be critically conceptualized via digital media. The firsthand accounts provide one way of attending to the interrelated benefits and difficulties of life on the back way.

Telling the stories of formerly obscured and marginalized African American communities in the U.S. South like those of the back ways requires methodologies for accessing previously unrecorded data, along with analysis and presentation approaches that may counter the dehumanization resulting from many of our whitewashed histories. Doing so advances existing research on the back ways of North Carolina and efforts to develop alternative digital expressions of place and space that better express the concerns of Black geographies. At the 2016 NEH Black Spatial Humanities Institute, I began designing a new digital humanities project to facilitate analyzing, curating, and sharing the oral history-recorded experiences of back ways community members. Simply, the work is meant to visualize oral history clips with animation similar in form to common television cartoons. The clips illuminate unique Black geographic information through firsthand accounts of living in the spaces and through passed-down stories of elders doing so. The visualizations illustrate the spatial practices of individual community members, like the chore of drawing water from a creek, along with transformations of the landscape, such as the development of the road. The work is meant to yield more critical and accurate representations of communities formed around the roads.

Orange County, the location of the back ways communities, is the home of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. According to the U.S. Census, it has the highest median household income in the state and its schools are recognized as being the best in North Carolina. Despite its notable progressive political leaning, Orange County, as described by the interviewees, is also noted for intense interracial tensions that include violence and harassment over the 20th and 21st centuries. One back ways interviewee, for instance, Dr. Freddie Parker, recounts the violent transition from attending the all-Black Central High School to the newly desegregated Orange County High School in the 1960s: “It was rough, a lot of bloodshed.” His history laments a lack of foresight afforded to his community’s demand for desegregation:

I don’t think we really had the foresight to see what it really meant because if you decide that you’re going to bring the walls of segregation down, the white students are not coming to your school.

Across shifts like school desegregation occurring in the encompassing interracial Orange County, the rural and historically agricultural back ways communities are characterized as maintaining a sense of accommodating normalcy for its residents, which is, however, as precarious as it is essential to the everyday and historical emplacements for those residents and their families.

The back ways, historic wagon roads used by Black farming families, themselves evidence the grounded nature of the communities that emerged around them—communities with histories of land cultivation and inhabited heir’s property. Some residents who contributed their oral histories are as much community historians by living on inherited property along a back way for as long as nine decades and descending from back ways community founders. Indeed, the histories lie with them and not in any official archives. Meanwhile, the narrated coordinates of community boundaries uniquely lie in those histories due to the historical denial of community recognition on the part of local governments. Some back way communities lie in formally marginalized zones called extra-territorial jurisdictions.Footnote2 In the context of the Back Ways project, all are described with nods to antagonistic county-community relations.

Back ways represent communities’ historic exclusion from state transportation mapping, surveillance, and development. In oral history interviews, participants explain that this widespread exclusion is said to have contributed to community and family autonomy from hostile government policies. For those who lived along them and used them, the roads are often presented as entangled components of century-long family histories which anchor the community to the physical environment. Recent development and modernization of these roads through paving and other forms of “improvement” ignore the communities’ historic and racialized emplacement. However, road improvements draw forth how erasures arise when the communities are delineated with US Census blocks and natural features of the landscape. Narrative and heritage are considered too messy even when recognized as important factors to consider in such development processes (Louis Berger Group Citation2001).

Indeed, there is little applied work that minds space-charting accounts of communal subjectivity and historic experiences with the actual impact assessments of communities in local and regional development projects in the U.S. South and elsewhere. It is through such understanding that regulation, which I am interpreting here as the systematized narration of historic Black geographies by those principally residing in them, might be important for representing spaces of Black collectivity. Without doing so, we fail to reckon with the integrity of these real sites of historic and ongoing collectivity. Indeed, these sites have had to be both other-ed and reliable. They require communities’ regulation of knowledge and call for representation that is sufficiently accommodating.

Centering personal accounts facilitates minding the steadfastness of back ways communities like Rogers Road. Population counts and geographic coordinates do not relay its historical depth and intergenerational importance. Without featuring the narratives in spatial representations, the community risks being rendered as an area where Black people have happened to live for some time. The road would not be understood as a binding locus for the families who live there. While the narratives that do provide this information are performed and recited, thus not fleeting or ungraspable, visually representing them is a difficult undertaking. Even so, it is an important one for such legibility and communication.

The inclusion of multimedia animation is somewhat novel in historical accounts of Black life in the U.S. South. My choice of this medium is based on its ability to allow for temporal representations of spatial dynamics such as a community’s formation over the twentieth century (Johnson Citation2002). Further, empirical work in geography has found it to be better suited for promoting course material retention (Crooks, Verdi, and White Citation2005; Edsall and Wentz Citation2007), a point that is perhaps especially important to take into account when communicating marginalized histories that have been violently erased from the landscape and our public knowledge. Animation is characteristically familiar and engaging. While the reading and interpretation of maps may be intimidating to viewers, engagement with animation is intended to be approachable while also clearly implying their obvious representative character. “Cartoons,” as commonly consumed media, are already recognized for being subjective and partial compared to feigned immutability of maps, however public. This empowers potential involvement to include community members’ robust critique of what is being produced rather than acquiescent compliance for fear of getting something wrong or not understanding. As an output, animation stands to be considerably more accessible to diverse audiences. Indeed, spatial work is bound to continually struggle to engage with supposed public-faced digital projects that require a specific literacy, even if they do so out of reluctance to over-simplify.

Because of this ease of access and legibility, the communication of unique spatial information is more likely. This is important as the primary point of the animation is to have people know of Black geographic space singularly demarcated by personal and community narratives. The animations depict life at the scales of the home and the community for the rural Back Ways enclaves. Having these two scales of animation establishes the historical depth of the farming communities established around wagon roads. The underappreciated space-demarcating practices accorded to Black geographies are too important to toy around with obfuscation. We must be attentive to the robust alterity that Black communities have counted on for generations now.

THE PROCESS OF CREATING ANIMATIONS

For this research, three animations were created with a professional animator. These clips came from the set of Back Ways interviews. The first step of the process was to isolate three pertinent oral history clips in which interviewees relay some spatial detail of the community’s shape and historic presence, with features that emplace people and portray them as dwelling in and interacting with the landscape. The interviewees chosen for these animations were in their eighties and nineties. The clips were taken from a collection of already coded and analyzed transcripts. The process involved combing through the pre-coded clips to determine which were most suitable for animation. The criteria used limited clips to accounts of movement through community space (i.e. walking to church) that were succinctly shared in the interest of short animation capability. The clips that were eventually chosen are rich and moving examples of everyday life in the back ways communities. After the clips were selected, they were individually edited with Adobe Premier to improve the quality of the audio and order the narrative if necessary. Editing on Premier sometimes involved rearranging the order information was spoken to account for backtracking and achieve greater clarity of the geographic features and events involved in the narrative. The results of such editing are described in .

TABLE 1 Comparison of Original Transcript Text and Text of Excerpt Edited for Animation

The editing was essential for giving the animator a clear story to depict. As is the case with the original transcription above, Harold Russell describes several different scenes related to the life of the church when asked about its general history. Illustrating all of the details of his oral history, with the looping and bypassing of time, would have been challenging both for the animator, and also due to financial constraints. This, therefore, required limiting the length of animation clips, and not all parts of a coherent narrative could be included for animation. Each of the three animations was limited to ~30 seconds, which meant that certain portions of the narrative like Harold’s sister being left at the church, had to be removed. Care was given to ensure the clips remained true to the content described in the oral histories throughout the process of animation. No editing occurred to alter the meaning of Harold and the other interviewees’ accounts. Nonetheless, it is important to clarify that these representations are not more comprehensive in their data coverage than a cartographic representation of the same space. They are similarly selective, though the types of spatial data that are selected for representation are very different from those that might be selected for cartographic mapping.

The clips selected for animation communicated vibrant instances of life within three back way community spaces. Each is taken from a separate oral history interview collected in the summer and fall of 2014. The selected segments depict scenes of everyday life in the historically agricultural Black communities of Orange County. The scenes cover the holistic and encompassing life community members were able to have all within these rural spaces of collectivity, and include themes of healthcare and religious observance. As described above, Harold Russell’s clip depicts how his family walked four miles through the woods to reach a wooded church site. Mary Cole describes how her childhood home served as the space for church service and how she had to move the furniture weekly to accommodate the congregation. Gertrude Nunn discusses how her mother sent her to get spring water and mended her brother’s leg within the home space after he cut it badly with an ax. These clips were chosen for the vividness of the descriptions and the ease by which I reasoned an animator would be able to depict the words spoken.

EVERYDAY METHODS OF COLLABORATING FOR AN ANIMATED PROJECT

The process of hiring a professional animator was facilitated by a website called upwork.com which matches freelancing creative professionals, such as animators and sound editors, with job opportunities. I selected this service due to its transparency and reputable standing. Those in need of service can post advertisements for jobs along with a fixed price for the task. The figure below is an image of the call for an animator as it appeared on the website. After posting it, I was able to invite animators to place bids based on their public portfolios, which are also accessible for browsing on the website. Other non-invited animators were able to also place bids for the job. The animator I worked with, Stella Rosen, was invited to undertake the job based on the look and quality of her previous animations. Once invited, Stella accepted the position and we entered a contract.

After securing the contract, Stella and I corresponded and exchanged media via the Upwork website’s messaging feature. I shared the first clip with her and described the scene as it is described in the clip itself, to ensure that she identified the key features. I also provided photographs of time/region-appropriate clothing and scenery from the Yale Photogrammar repository. Finally, I provided some background information about the person speaking, such as age and tenure in the community space, as well as the community space (i.e. its status as a family farm). Within a day, Stella delivered a video storyboard of the animation, which is depicted below. This storyboard provided a rough play of the animation and its contents. Upon receiving feedback, Stella then altered the storyboard and sent an updated version, which is also depicted below. This process of revising the storyboard occurred with all three clips, with them all going through two or three rounds of storyboard revisions. For example, with the first clip, I requested that the speaker be depicted as a young girl witnessing the story and that her action of running to a spring for water be included, which were not shown on the initial storyboard as shown below. Having these aspects animated were critical for the overarching goal of the animations being the humanizing of long-disregarded rural sites of Black collectivity. Such sites have been historically unmapped and considered merely wooded and meager. The animations were meant to highlight the evidence of rich livelihoods that occur within the rural spaces themselves along with the people who have lived within them.

Both of the depictions in are taken from the same mark in time. They are shown to illustrate the transformation of the animations’ eventual content per the aims of the project, which were to ensure that representations were also populated with a gaze of the creator of the content (ie, the oral history participant). The process of producing these illustrations was made easier by the responsiveness and talent of the animator, and was supported by my clarity when contracting her; I was careful to convey that I intended to show how the communities from which the stories come exist, and make their histories tangible. She was receptive to such an aim and it showed in the work she was able to produce.

THE FINAL ANIMATIONS

The animations are colorful, dynamic depictions of everyday life in three different historically Black Back Ways communities in rural Orange County, NC. They show the actions of community residents against and with the surrounding rural environments to the effect of humanizing the often disregarded landscape. Oftentimes, such populated Black environments are discursively marginalized or altogether elided in dominant representations of space. Indeed, as Price (Citation2004) notes, exclusion of racialized peoples to such discursive unmapping in the wild is critical to the function of Western understanding of place. Such exclusion, in the form of cartographic erasure and otherwise, allows local governments to disregard the robustness and life within the sites of Black spatial collectivity. This then eases the facilitation of harmful land-use like the placement of a landfill in the Rogers Road community, which is the setting of one of the animations. The map then is a historically polarizing tool of exploitation and harm for these communities. In light of this, the three animations provide some alternative means of counter-mapping without reinvigorating the potentially hostile function of the map itself.

Animation 1: https://vimeo.com/263541225 (Password: backways)

In the first animation (see ), Harold Russell describes the wooded site of his family’s historic church. Harold Russell is a community elder who returned to his rural enclave following a career in chemistry. He received his Ph.D. from Cornell University. Harold Russell has taken on the unofficial role of historian for Harvey’s Chapel, a church founded by his ancestors and the one he attends today. Part of his historical work has involved going a search for the original church site’s land deed and attempting to uncover how the church came to be located in a relatively remote location. The location of the church is the focus of Russel’s animation clip.

The clip opens with Harold stating that he remembers going to the church many years ago, which is shown surrounded by trees. Two birds fly across the sky as the screen pans across the mass of greenery before settling on the home of Harold’s grandparents as he names the location of the church, “near Seven Mile Creek.” Harold is then heard recounting how his mother, in her youth, and his grandparents would walk four miles from their home to the church as a regular practice while the animation depicts them strolling through tall grasses and shrubbery. Though simpler than the other two clips in terms of action, this animation illustrates the wide-ranging forested landscape that set the historic collectivity of Harold’s family and community. The animation concludes with Harold telling how someone once saw a snake slither down the wall of the church. By depicting the woods and the church’s emplacement side-by-side, the animation shows how the rural and natural environments are intertwined. It implicates the ways that the natural environment vis-à-vis the greenery and the snake betray the emplacement rather than the absence of human collectivity vis-à-vis the church. The wilderness, typically depicted as a blank space on the map, is portrayed as a setting for Harold’s family mobility and his community’s coming together.

Animation 2: https://vimeo.com/263541003 (Password: backways)

In the second animation featuring Mary Cole (see ), she recounts moving furniture in her childhood home weekly to make room for church services. Today, she is a community elder whose father bought the land that came to be a community epicenter. Including providing space for religious worship, her father’s land also accommodates a sizable farm and the residences of some of Cole’s relatives. Throughout her oral history, Cole recounts the effort and activities that went into her home serving as community space—the bubbling kitchen and myriad relations colored her childhood experiences. Also, the status of her home as a community space involved work on her part, which is recounted in her clip about moving furniture before worship service.

The animation opens with a shot of her family house. The sun replaces the moon to show how the services and need for moving furniture occurred mornings and nights. On Wednesday nights her family hosted bible study while congregants showed up for worship services on Sunday mornings. Such weekly day and night activity undergirds the status of their home as the designated site for the church. The animation then moves to the inside of the home where a preacher is shown delivering a sermon. Mary narrates the scene relaying how different preachers would come to lead the congregation. The scene then shows a crowd of people as Mary recounts how many people would come to attend the services. Such depiction enlivens the historic communal centrality of Mary Cole’s family land. The animation concludes with a young Mary being shown struggling to move a sofa as she recounts having to move the furniture to accommodate the crowd. The animation concludes with a flashing view of the room that held the congregants now shown as a living space full of furniture—sofa, vases, end tables, and a coffee table—as Mary recalls vowing to never move her furniture so much again as an adult.

Animation 3: https://vimeo.com/263540643 (Password: backways)

The third animation illustrates an emergency from the childhood of Gertrude Nunn where her mother sent her to fetch water from a nearby spring to treat her brother’s wound (see ). Nunn has spent decades living in the rural community that she currently calls home, Rogers Road. She is a well-known matriarch of Rogers Road, which is named after her father. She has also acted as an advocate for the community—organizing and speaking out against the placement of an ill-conceived landfill. She recounts such instances of modernization and how they have affected life in the community space. Reflecting on earlier times, like the one in her animation, she recalls an aspect of self-sufficiency in times of crisis that may now be gone.

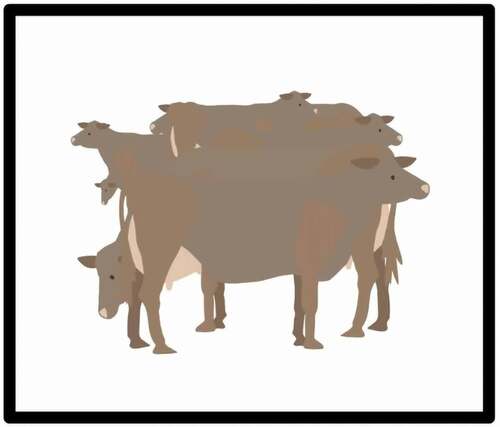

The animation opens with a young Gertrude turning toward a developing pasture scene of cows grazing. Immediately, the agricultural setting is established with the livestock and the Gertrude recalling the everyday practice of having to take them out to graze. Her brother’s injury was a result of his carrying an ax while taking them to do so. At this point, the scene turns to a disembodied ax in the center of the screen. The animation carries on with Gertrude recounting how the ax fell off her brother’s shoulder and badly cut his leg. The animation then depicts the disembodied ax in the center falling to create an also disembodied wound at the bottom of the screen. As Gertrude recalls blood flowing out vigorously, the screen with a fluid pale red hue. The scene then turns to an alert young Gertrude running from the spring as commanded by her mother with an overflowing pail of water in hand. The healing effect of the water is implicated in what follows. Gertrude recalls her mother cleaning the wound with water, packing it with mud and a felt hat, and then wrapping it with a clean cloth. These actions are depicted one-by-one. They are all disembodied. The relationship between the resources of the land—fresh spring water—and the well-being of the community are represented by the animation via the healing of Gertrude’s brother via her mother’s knowledge. The animation closes with her remembering how the wound heals leaving her brother with no complications.

CONCLUSION

The animations produced here were able to depict stories of life in the back ways communities. By just listening to the recorded audio or reading through the transcripts, it is easy to miss the particular illuminations of space relayed by the oral history accounts. The animations, however, provoke viewers to reckon with the particularities of day-to-day life in the rural Black collectives. At the same time, the animations presented here are not without limitations. One is the limitation of cost. It took specialized skill to create the animation, which I like most researchers, do not possess. This meant hiring an independent artist for a limited amount of animation. Naturally, the vast bulk of the spatial account contained in the back ways interviews were left out. Relatedly, the need to hire an independent contractor meant the process of creating them had to be done by someone without much knowledge of the research project—Stella is a professional animator who, by no fault of her own, is not knowledgeable about f Black geographic and critical cartographic literature nor the empirical data that predicates the creation of the three animations.

Future work with animation, like that modeled here, could benefit from more robust partnerships with animators. It could have been useful to have Stella on board at an earlier stage of the project and in thinking through what questions were asked in interviews and what the broad research aims were. Another limitation of animation, here and generally speaking, is the inability to comprehensively represent space. They do not depict how large or populated the communities are. In light of this, it is critical to remain mindful of what scale of space is comparatively represented—that of everyday life, which perhaps makes the lack of comprehensibility a trade-off. With these limitations considered, the animations were still successful in relaying the regularity of occupying the back ways communities as narrated by interviewees.

The regularity of the narratives depicted by the animations is evident in their telling. While Gertrude’s daughter was not yet born during the incident, she is heard in the clip prompting and corroborating the telling of the story. In the portion with Mary Cole, she mentions how she told her kids, as she tells in her oral history, that she vowed to never move furniture in her own home as a result of the previously recounted practice. Harold himself was not yet born when his mother, in her youth, walked with his grandparents to the church; the narrative and its place-illuminating qualities were passed down to him. Also, he recounts the story of the snake, which had been told to him before he told it again. Such is the nature of the narratives, which themselves animate the space of the rural Black communities as historic and lived-in sites of collective self-reliance. To represent such spaces in-depth, we cannot rely on the conventional map. Indeed, such is true for the social depth of all communities.

While cartography provides useful tools for digital humanities and the conduct of Black spatial humanities, the spaces wrought by Black collectivity are likely seldom to find sweeping purchase there. If we take seriously the charge of McKittrick and Woods (Citation2007) that narrative and lived experience determine Black geographic space, we must too consider means of representation that accommodate rather than assimilate humanistic matters. In this paper, I invite the reader to consider animation only one potential means of representing the narratives of individuals from the three Black communities. This means is undoubtedly incomplete and inadequate to “do the job” of representing the totality of any Black geographic space on its own. We must also consider the possibilities of film, still art, audio, and other sorts, which often are produced from within communities themselves as being representations of space. We must too be mindful of the impossibility of the task—representing that which is unfolding and often intently unseen. I hope that this work of aligning the narratives vis-à-vis animations as counter-cartographic and space-demarcating widens the scope of reckoning with such (im)possibilities of alterity represented.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author owes thanks to Angel David Nieves and Kim Gallon who organized Space and Place in Africana/Black Studies: An Institute on Spatial Humanities Theories, Methods and Practice for Africana Studies (National Endowment for the Humanities). In addition, the author appreciates the generous feedback of Seth Kotch, Malinda Maynor Lowery, Betsy Olson, Scott Kirsch, Banu Gökarıksel, and the reviewers.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Darius Scott

DARIUS SCOTT is an Assistant Professor of Geography at Dartmouth College, HB 6017, Hanover, NH 03755. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interest include health, the American South, oral history, and Black geographies.

Notes

1. “Nowhere at all” is a construct adapted from Hortense Spillers’ 1987 essay, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book.”

2. This term is used by governments, in this case, the surrounding city governments, to mark places subject to the authority of their legal power that lie outside of terriorial boundaries. These jurisdictions lack elected political representation.

REFERENCES

- Bodenhamer, D., J. Corrigan, and T. M. Harris. 2015. Deep maps and spatial narratives. Indiana: Indiana University Press.

- Bullard, R., P. Mohai, R. Saha, and B. Wright. 2007. Toxic wastes and race at twenty 1987–2007. A Report Prepared for the United Church of Christ Justice & Witness Ministries. United Church of Christ.

- Caquard, S. 2013. Cartography I: Mapping narrative cartography. Progress in Human Geography 37 (1):135–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132511423796.

- Carter, B. n.d. Virtual Harlem. Accessed July 17, 2020. https://scalar.usc.edu/works/harlem-renaissance/index.

- Cohen, D. J., and R. Rosenzweig. 2006. Digital history : A guide to gathering, preserving, and presenting the past on the web. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Corner, J. 2011. The agency of mapping: Speculation, critique and invention. In The map reader: Theories of mapping practice and cartographic representation, 89–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470979587.ch12.

- Crang, M. 2015. The promises and perils of a digital geohumanities. Cultural Geographies 22 (2):351–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474015572303.

- Crooks, S. M., M. P. Verdi, and D. R. White. 2005. Effects of contiguity and feature animation in computer-based geography instruction. Journal of Educational Technology Systems 33 (3):259–81. doi:https://doi.org/10.2190/NQ6B-3LMA-VMVA-L312.

- Edsall, R., and E. Wentz. 2007. Comparing strategies for presenting concepts in introductory undergraduate geography: Physical models vs. computer visualization. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 31 (3):427–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260701513993.

- Hawthorne, C. 2019. Black matters are spatial matters: Black geographies for the twenty‐first century. Geography Compass 13 (11). doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12468.

- Inwood, J. F. J. 2011. Geographies of race in the American South: The continuing legacies of Jim Crow segregation. Southeastern Geographer 51 (4):564–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/sgo.2011.0033.

- Jefferson, B. J. 2018. Predictable policing: Predictive crime mapping and geographies of policing and race. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (1):1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1293500.

- Johnson, A., J. Leigh, B. Carter, J. Sosnoski, and S. Jones. 2002. Virtual Harlem. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications 22:61–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1109/MCG.2002.1028727.

- Johnson, N. 2002. Animating geography: Multimedia and communication. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 26 (1):13–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260120110331.

- Kim, D. J. 2017. Introductory/framing remarks. In Black spatial humanities: Theories, methods, and Praxis in digital humanities (a follow-up NEH ODH summer institute panel), eds. A. D. Nieves, K. Gallon, D. J. Kim, S. Nesbit, B. Carter, and J. Johnson, 1–2. Montreal: Digital Humanities.

- Knowles, A. K., L. Westerveld, and L. Strom. 2015. Inductive visualization: A humanistic alternative to GIS. GeoHumanities 1 (2):233–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2015.1108831.

- Kwan, M.-P. 2008. From oral histories to visual narratives: Re-presenting the post-September 11 experiences of the Muslim women in the USA. Social & Cultural Geography 9 (6):653–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360802292462.

- Kwan, M.-P., and G. Ding. 2008. Geo-narrative: Extending geographic information systems for narrative analysis in qualitative and mixed-method research*. The Professional Geographer 60 (4):443–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00330120802211752.

- Leszczynski, A. 2015. Spatial media/tion. Progress in Human Geography 39 (6):729–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132514558443.

- Lipsitz, G. 2011. How racism takes place. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Louis Berger Group. 2001. Guidance for assessing indirect and cumulative impacts of transportation projects in North Carolina. Volume I: Guidance policy report. Cary: Louis Berger Group.

- Madera, J. 2015. Black atlas : Geography and flow in nineteenth-century African American literature. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Maharawal, M. M., and E. McElroy. 2018. The anti-eviction mapping project: Counter mapping and oral history toward Bay Area housing justice. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (2):380–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1365583.

- McKittrick, K. 2006. Demonic grounds : Black women and the cartographies of struggle. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- McKittrick, K. 2011. On plantations, prisons, and a Black sense of place. Social & Cultural Geography 12 (8):947–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2011.624280.

- McKittrick, K., and C. A. Woods. 2007. Black geographies and the politics of place. Toronto, ON: Between the Lines.

- Nieves, A. D. 2007. Memories of Africville: Urban renewal, reparations, and the Africadian diaspora. In Black geographies and the politics of place, eds. K. McKittrick and C. A. Woods, 82–96. Toronto: Between the Lines.

- Offen, K. 2013. Historical geography II: Digital imaginations. Progress in Human Geography 37 (4):564–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512462807.

- Olson, E., and A. Sayer. 2009. Radical geography and its critical standpoints: Embracing the normative. Antipode 41 (1):180–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2008.00661.x.

- Peterle, G. 2018 January. Carto-fiction: Narrativising maps through creative writing. Social & Cultural Geography 1–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2018.1428820.

- Pickles, J. 2004. A history of spaces : Cartographic reason, mapping, and the geo-coded world. London: Routledge.

- Price, P. 2004. Dry place : Landscapes of belonging and exclusion. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Pulido, L. 1996. Critical review of the methodology environmental racism research. Antipode 28 (2):142–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.1996.tb00519.x.

- Pulido, L. 2000. Rethinking environmental racism: White privilege and urban development in Southern California. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 90 (1):12–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/0004-5608.00182.

- Rose, G. 2016. Rethinking the geographies of cultural “objects” through digital technologies. Progress in Human Geography 40 (3):334–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132515580493.

- Spillers, H. 1987. Mama’s baby, papa’s maybe: An American grammar book. Diacritics 17 (2):64–81. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/464747.

- Tally, R. 2014. Literary cartographies : Spatiality, representation, and narrative. 1st ed. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- “The Ward: Race and Class in Du Bois’ Seventh Ward.” n.d. Accessed July 17, 2020. http://www.dubois-theward.org/.

- Wood, D. 2013. Everything sings : Maps for a narrative atlas. 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Siglio.

- Wood, D., J. Fels, and J. Krygier. 2010. Rethinking the power of maps. New York: Guilford Press.

- Woods, C. 1998. Development arrested : The blues and plantation power in the Mississippi Delta. London: Verso.

- Woods, C. 2002. Life after death. The Professional Geographer 54 (1):62–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-0124.00315.

- Wynter, S. 2000. Beyond Miranda’s meanings: Un-silencing the “demonic ground” of “Caliban’s woman.” In The Black feminist reader, ed. J. James and T. D. Sharpley-Whiting, xiv, 302. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

- Wynter, S. 2006. On how we mistook the map for the territory, and reimprisoned ourselves in our unbearable wrongness of being, of desêtre: Black studies toward the human project. In A companion to African-American studies, eds. L. R. Gordon and J. A. Gordon, 107–18. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.