Abstract

Athens-Clarke County, Georgia is home to the first publicly chartered institution of higher learning in the United States: The University of Georgia (UGA). For the last 200 + years, UGA has brought settlers to Athens and led them in Indigenous removal, slavery, Jim and Jane Crow politics, segregation, and racial discrimination. A reckoning with this history of slavery and the ongoing harms of settler-colonial higher education is long overdue. This paper describes the efforts of a group of faculty and students at UGA beginning this process. In particular, we utilize Christina Shape’s (2016) notion of “wake work” to reflect upon a visceral moment of anti-Black violence on our campus: the unearthing and contested reburial of human remains that were likely enslaved or formerly enslaved individuals during the expansion of UGA’s Baldwin Hall. Sharpe’s wake work asks us to sit with the omnipresence of Black death, but to also imagine a future otherwise. We provide personal vignettes and remembrances about our experiences with the events and activism surrounding Baldwin Hall as a key component of coming to consciousness about the institutions and practices of white supremacy within the place we work and learn. We conclude with specific recommendations to other universities and their faculty, students, staff, and community members fighting for racial justice.

美国佐治亚州的Athens-Clarke县拥有美国第一所公立特许高等学校:佐治亚大学(UGA)。在过去200余年里, UGA给Athens带来居民, 引导他们实施土著驱逐、奴隶制、吉姆和简·克劳政治、种族隔离和歧视。然而, 迟迟没有对奴隶制历史和定居者殖民高等教育的持续危害进行清算。本文描述了UGA的教职员工和学生群体启动这一过程的努力。特别地, 我们采用Christina Shape(2016)的“觉醒”概念, 反思了UGA校园的一个草率的反黑人暴力时刻:在UGA的Baldwin Hall扩建期间, 挖掘和有争议地重新埋葬可能被奴役或曾经被奴役的人的遗骸。“觉醒“要求我们面临无处不在的黑人死亡, 但也要想象一个不同的未来。本文展现了我们围绕Baldwin Hall的活动和激进主义经历的个人花絮和纪念, 从而意识到我们工作和学习场所的白人至上主义制度和行为。最后, 对于其它大学及其教职员工、学生和社区成员, 我们提出了为种族正义而战的具体建议。

El Condado Athens-Clarke, en Georgia, es la sede de la primera institución pública aprobada de enseñanza superior de los Estados Unidos: la Universidad de Georgia (UGA). Durante los pasados 200 años, la UGA ha traído pobladores a Athens y los ha orientado en la eliminación de los indígenas, la esclavitud, la política de Jim y Jane Crow, la segregación y la discriminación racial. Un balance de esta historia de esclavitud y de los daños que sigue causando la educación colonial de pobladores, es algo que no puede aplazarse más. Este escrito describe los esfuerzos de un grupo de profesores y estudiantes de UGA para iniciar este proceso. Particularmente, utilizamos la noción de Christina Sharpe del “trabajo de vigilia” para reflexionar sobre un momento visceral de violencia contra los negros en nuestro campus: el desentierro y el reentierro disputado de restos humanos de individuos que probablemente fueron esclavizados o que lo habían sido durante la expansión del Baldwin Hall de la UGA. El trabajo de Sharpe nos reclama que asumamos la omnipresencia de la muerte negra, pero que también tratemos de imaginar un futuro diferente.

INTRODUCTION

It is high time that universities in the United States recognize, examine, and atone for their colonial and racist pasts. This includes the role of Indigenous removal, land theft, slavery, segregation, and discrimination in the founding and operations of higher education. Some universities have begun this process, and the Universities Studying Slavery (USS) consortium documents these efforts and connects these institutions. In some cases, this reckoning has been initiated by higher levels of university administration. In other cases, it is undertaken by individual scholars or academic units without the explicit support or approval of higher authorities. In our case, at the University of Georgia (UGA), much of this reckoning has been led by a group of student activists with the help of faculty and community groups, with noted silences on the continued legacy of slavery from upper administration. While UGA acts as though its intersections with slavery, racism, and segregation are part of an unspeakable past that is over now, student activists demonstrate that the practices of exploitation and discrimination continue on in new ways. In all cases, confronting these issues requires acknowledging how these are living histories that built and sustain our academic institutions today, rather than simply “events” of the past; their effects and harms are still with us today and the practices continue on, in new more acceptable forms.

We are members of a group of students and faculty using radical and intersectional Black feminist theory to learn together at the University of Georgia (Athena Co-Learning Collective Citation2018, Citation2021a, Citation2021b). In the spring semester of 2019, we participated in a graduate seminar to examine our own relationships to structures of power and oppression in the university. This involved engagement with scholars, activists, and community members whose experiences of the university are often neglected or erased, as well as critical self reflection about our own roles in these systems. Importantly, we undertook these efforts in the midst of significant upheaval and controversy regarding the exhumation and contested reburial of human remains that were likely enslaved or formerly enslaved individuals during the expansion of Baldwin Hall on UGA’s campus.Footnote1 Since the initial unearthing of these human remains in 2015, many individuals and organizations at UGA have initiated important confrontations with the university’s racist history. Student activist groups organized, along with the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences Faculty Senate and many individual students, faculty, and staff. Many in upper administration at UGA, however, maintain the university’s innocence in the process of desecration and reburial, despite assertions from Black community members otherwise.

These events and our scholarly texts gave us an opportunity to examine ourselves and our school in relation to the legacies of slavery at UGA and settler education, more generally. In this article, we document and describe our process to uncover, confront, and address our relationships to white supremacy in higher education. Authors contributing to this project have different relationships to this history, but despite our varying positionalities, we believe that silence and inaction perpetuate and sanction white supremacy. We join many others doing this work, including Dr. Hillary Green who led the University of Alabama’s Hallowed Grounds Project, as well as Georgetown University who established the Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation to address its legacy of slavery in higher education.

Specifically, we engage with Christina Sharpe’s book In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (2016) to guide us through the many steps of recognition, reconciliation, and redress that are involved in a reckoning process. We take inspiration in how Sharpe (Citation2016) describes “the wake” as having many articulations that allow for reflection and resistance, including “keeping watch with the dead,” “the path behind a [slave] ship,” and “a consequence of…consciousness” (17–18). This, which we describe in detail below, allows us to acknowledge the forms of premature Black death that saturate our past, the forms of “containment, regulation, and punishment” (Sharpe Citation2016, 21) born out of settler colonization and racial capitalism, and the moments of resistance, consciousness, and possibility that are always present. Our goal is to demonstrate the applicability of Sharpe’s framework to understand the events at our own institution of learning and to provide a methodological example of how personal reflection can be useful to evaluate the omnipresence of anti-Black violence.

In what follows, we first outline a few important moments in the colonial and racist history of our institution—the University of Georgia. We then provide more description of the framework we use to illuminate our pathway of recognition and redress offered by Sharpe’s book. Next, we describe three moments of “wake work” related to a significant moment of racial reckoning at UGA during the expansion of Baldwin Hall, where the graves of over one-hundred enslaved or formerly enslaved individuals were unearthed from under the building during an expansion project. Following the modes of reflection and recollection provided by Sharpe, we include personal vignettes and remembrances about our experiences with the events and activism surrounding Baldwin Hall. We do this work to confront white supremacist violence in the context of the “corporate university” (Mohanty Citation2003, 139) and redress the harms it has caused by creating what McKittrick calls “more humanely workable geographies” (McKittrick Citation2006, xii).

This paper represents one of the avenues we have engaged in to hold ourselves and our university accountable for its role in settler colonialism, white supremacy, chattel slavery, anti-Blackness, and continued racial oppression and exclusion. As Sharpe writes, an “ethics of care…an ethics of seeing, and being in the wake as consciousness” (131) is necessary to “counter the violence of abstraction” (130). We hope that our experience of “wake work” through collectively generated thinking, action, and pedagogy will be of value to others engaged in this process of reckoning and redress.

RACIAL VIOLENCE: THE FOUNDATION OF THE United States’ FIRST PUBLICLY CHARTERED INSTITUTION

It is widely touted that UGA is “the birthplace of public higher education in America” (University of Georgia Citation2017). Indeed, UGA was the first U.S. public university chartered in 1785 and it remains a top-tier research and learning institution today. Yet, as we describe here, UGA (like many universities in the United States) is also deeply connected to a violent and ongoing history of dispossession and white supremacy.Footnote2 This is evident in present-day demographics of the university, as well as the state sanctioned forms of land theft, segregation, and discrimination that have affected BIPOC communities for centuries.

In 2020, UGA reported that 8% of its undergraduate enrollment identified as Black or African American, 6% identified as Hispanic, 4% identified as multiracial, 10% identified as Asian, and less than 1% (only 45 students out of 39,147) identified as native or American Indian (University of Georgia Citation2020). Clearly, this means that the vast majority—that is, 67%—of students on UGA’s campus are white. This contrasts significantly with the demographics of the state UGA is supposed to serve, especially for Black people. In 2021, the US census reported that 59.4% of Georgia’s residents are white (alone), while 33% are Black, 10.2% identify as Hispanic or Latino, 4.6% are Asian and 0.5% are American Indian or Native Alaskan (US Census, Citation2021a). This discrepancy in the students that UGA admits compared to the state’s demographics is a result of systemic racism in our communities, schools, and universities.

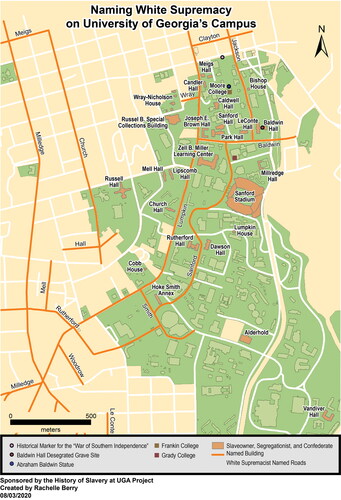

The significant over-representation of white Georgians can be seen and felt all over campus. Dozens of fraternity and sorority houses, many former plantation homes or made to look like plantation homes, line the main thorough way Milledge Avenue that lies just west of campus, harkening back to the town’s violent racial past. The campus prominently displays buildings, colleges, and statues named after slave owners and segregationists (Posey, Citation2020), and Lumpkin Street, one of the main thoroughfares through campus, is named for the governor who presided over Indigenous removal and the appropriation of Indigenous lands during the 1830s.

The University of Georgia is located on the stolen lands of the Mvskoke (Muscogee Creek), S’atsoyaha (Yuchi) and Tsalaguwetiyi (Eastern band of Cherokee) nations (Native Land, Citation2021; Saunt, Citation1999, Citation2020). These nations were organized into hundreds of loosely federated towns with an agricultural economy based on corn (Dunbar-Ortiz, Citation2014). The Mvskoke had three branches of government composed of “civil administration, a military, and a branch that dealtwith the sacred” (Dunbar-Ortiz Citation2014, 26). The sacred element was central to the negotiation of treaties and relations between federated towns by a broad council, to which each town sent a representative delegation. The agreements reached were as much with the sacred power as they were to the other delegations, making treaties difficult to establish with settlers who did not share the same worldview. However, after settler colonization ensued, Europeans brokered multiple treaties with the Indigenous nations of the Southeast, all of which were eventually broken or abandoned by the U.S. government as the desire for more land and wealth pushed the American frontier farther west.

The name of Athens-Clarke County, home to UGA, harkens to a white-washed history of democratic institutions as an homage to Athens, Greece and to Elijah Clarke, a vigilante and militia leader who was involved in several guerilla campaigns in the Revolutionary War, including those against Indigenous settlements (Davis, Citation2017). In 1794, nine years after UGA was chartered, Clarke built a militia to hasten the Indigenous removal of the Mvskoke and Tsalaguwetiyi people because he felt the treaties he oversaw in the Military’s Indian Affairs office did not remove Indigenous tribes from their ancestral lands fast enough, including land upon which the University of Georgia now sits (Georgia Historical Quarterly, Citation1943). In the early 1800s, Georgia Governor John Milledge bought 633 acres of land for the university from a settler land speculator that the Mvskoke once called home.

It is reported by the university itself that “UGA’s own opening was delayed by the Oconee War until 1801, due to violent conflicts between the settlers in Georgia and the Creek Nation’” (Liang, Citation2020). Prominent places in Athens, GA feature the names of white men involved in Indigenous removal: Clarke, Baldwin, Milledge (see ). White city officials honored these jingoistic settlers with streets, buildings, and even the name of the county. Though some Indigenous names persist (i.e., Oconee), their meanings are lost to white supremacist renderings of history. Ultimately, nearly all Indigenous people in what is now Georgia were forcibly removed to reservations in territories to the west. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 removed all of Indigenous land ownership by the middle of the 19th century and forced all Southeastern tribes to move west of the Mississippi River (Saunt Citation1999, Citation2020). This cleared the way for settlers and their institutions—UGA included—to establish private property and make land claims (Smith, Funaki and MacDonald, Citation2021). Indeed, land grant universities, like UGA, are “land grab” universities built on the stolen Indigenous land through the Morrill Act of 1862 (Lee and Ahton, Citation2020).

FIGURE 1 Map of buildings, markers, and roads named for white supremacists, slave owners, and/or segregationists on UGA’s campus produced as part of the History of Slavery at UGA research project.

Initially James Ogelthorpe and his Trustees succeeded in banning slavery from the Georgia colony because they believed slavery would be a threat to the security of the colony (Wood, Citation2021). However, Ogelthorpe found that many settlers were reluctant to work and slaveholders from neighboring states, namely South Carolina, wanted to expand their business into Georgia (Wood, Citation2021). The Trustees eventually caved to the demand for slavery and in 1751 the trustees permitted slavery in the colony (Wood, Citation2021). Carolina planters immediately expanded their slave-based rice economy into the Georgia Lowcountry (Wood, Citation2021). Between 1750 and 1755 the slave population increased from 500 to 18,000 and by the mid-1760s the colony began directly trafficking Africans from Angola, Sierra Leone, and the Gambia (Wood, Citation2021). Slavery quickly spread across the colony as settlers established plantation agriculture arcoss the stolen Indigenous land. Indigenous removal and racial slavery, followed by sharecropping and Jim & Jane Crow segregation, created the deep and violent racist histories that begun under settler colonialism in Athens, GA, as with the rest of the southern Unites States.

After slavery the violence continued in sometimes worse forms. Between 1882 and 1930, Georgia’s lynching victims numbered 458, second only to Mississippi with 538 lynchings (Tolnay and Beck Citation2020). Throughout the twentieth century, confederate monuments and the second coming of the Ku Klux Klan rose up out of Atlanta, GA, a mere 80 miles from Athens, after William J. Simmons was galvanized by the film Birth of a Nation (Lay, Citation2020). Athens, Georgia put up its own Confederate monument memoralizing the fight to continue slavery in 1872 in the city center—a monument that activists have since successfully forced the city to relocate away from the entrance of UGA and downtown Athens, but not destroy.

An estimated six million Black men, women, and children fled racial violence in the South between 1916 and 1970 (Wilkerson, Citation2016). However, the census numbers for Athens show steady population growth for the Black population in Athens during this time, except for one decline of over 2,000 individuals between the years 1920 and 1930 (Social Explorer Dataset Citationn.d.a, Citationn.d.b). Unsurprisingly, this drop is recorded five years after the second rising of the KKK emerged from Atlanta, Georgia; and one year after 1,000 s of men stormed the Athens jail and lynched John Lee Eberhart, a Black man accused of killing a white woman in Oconee County who maintained his innocence until his murder (Kalaji, Citation2021).

CONTEMPORARY RACIST HISTORIES AT UGA: INTEGRATION, THE DESTRUCTION OF LINNENTOWN, AND BANNING OF UNDOCUMENTED STUDENTS

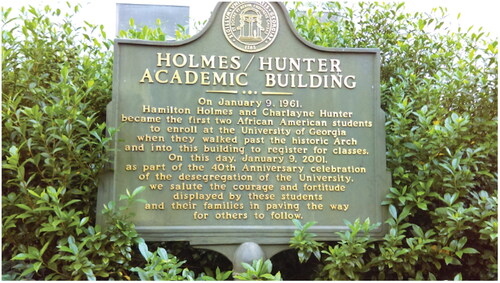

It was not until 1961 that the University of Georgia by court order was forced to integrate starting with admitting Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes (), UGA’s first Black students. In fact, the only building named for a Black person on campus until 2022, the Holmes-Hunter Academic Building, honors these two students. A plaque next to the building reads “the first two African American students to enroll at the University of Georgia when they walked past the historic Arch and into this building to register for classes,” making no mention of the multiple court orders necessary for their sustained enrollment, white students chanting “two, four, six, eight, we don’t want to integrate” as they registered for classes, or the subsequent riot that broke out on campus later that day. In response to the rioting, white students the University took their threats of violence as an opportunity to suspend the two Black students, claiming it was “for their own safety” (Besel, Citation2018). Even today, many Black students report feeling unwelcome at UGA and in Athens, GA, more generally (Miranda, Citation2020).

In the early 1960s, a sign appeared in the Black neighborhood of Linnentown adjacent to the university that read: “University of Georgia Urban Renewal Area Project GA-R50.” Barely a block from the university, this community started developing in the early 1900s, and by 1960, the families in Linnentown maintained a tight-knit, intergenerational Black neighborhood of mostly homeowners and skilled workers (Whitehead, Citation2021). In the early 1940s, UGA identified the land as desirable for their expansion, and when funding became available for land grant universities in the 1960s to participate in urban renewal, UGA administrators targeted this neighborhood for removal (Whitehead, Citation2021). With LBJ’s funding for urban renewal and cooperation from the city of Athens, the properties in Linnentown were acquired and demolished for the university after condemning many of the homes in the “slum” (reports from residents and archival records show this was not the case) and then seizing them through eminent domain, paying as little as possible to the Black homeowners displaced by the process.Footnote3 Living descendants of Linnentown vividly recall the pain and terror of the destruction of Linnentown to this day.

Racialized violence continues into the 21st century and exclusion extends beyond Indigenous and Black populations at the University of Georgia. In 2010, the University System of Georgia Board of Regents passed a series of policies that denied undocumented students admittance into the state’s top institutions. Policy 4.1.6 legally established that “a person who is not lawfully present in the United States shall not be eligible for admission to any University System institution which, for the two most recent academic years, did not admit all academically qualified applicants” (University System of Georgia, Citation2022). This means that any undocumented Georgia student, regardless of her/his/their history of residence or qualifications, are not allowed to attend the state’s leading institutions, including the University of Georgia, Georgia Tech, and Georgia College and State University. This discriminatory policy primarily affects Hispanic and Latinx residents in Georgia and remains in place despite significant efforts by faculty and students to overturn it.

As previously mentioned, many universities participated in this violent and racist history, which remains present today in the landscape of the university, the demographic of UGA’s student body and the university’s role in its local economy. The University of Georgia is the largest employer in Athens-Clarke County, yet, it contributes to significant rates of poverty and displacement. Athens-Clarke County experiences a 26.6% poverty rate (US Census, Citation2021b) and Black people make up 44% of UGA service workers, the lowest-paid workers at UGA (Downey, Citation2021). Meanwhile, the median family income for UGA students is $129,800 and 59% of students come from the top 20% of family incomes in the state (New York Times, Citation2017).

It is in the midst of this history and present, as well as the unearthing and contested reburial of enslaved or formerly enslaved individuals at Baldwin Hall and a national uprising and reckoning over the murders of Black people, that we—faculty and students at the University of Georgia—find ourselves confronting our own institution’s engagement and complicity with white supremacy. Specifically, in 1934, UGA administrators greenlighted the construction of an administrative building—later named Baldwin Hall—on top of the Old Athens Cemetery, including the portion that was the resting place for many enslaved or formerly enslaved Africans (Gresham et al., Citation2019). Construction on Baldwin Hall commenced between the years of 1937 and 1942. There are many accounts of human remains being found during the initial construction, but no official account of any reburial (Gresham et al., Citation2019). In fact, one historian claims that the remains had been thrown into the dump. These stories of indignity and disrespect had been whispered about in Black Athenians’ folklore, but they would not have confirmation until the discovery of additional remains at Baldwin Hall in 2015 during an expansion project; human remains that were reinterred by UGA with no meaningful consultation with the descendant community.

PATHWAYS FORWARD: SHARPE’S WAKE WORK

It is our participation in campus activism during a spring 2019 seminar that underpins the ideas and activities we discuss here. Specifically, we examine the ways that the Baldwin Hall controversy—our experience of it, our organizing around it, and our university’s response to it—intersected with our scholarly commitments against white supremacy during this time. Those of us contributing to this paper are situated with varying relationships to history and oppression: this includes our first author, a Black nonbinary person, and the remaining authors who identify as cis white women—some queer and some straight.

Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being served as the central text for our spring 2019 seminar. In the book, Sharpe (Citation2016) explores what happens if we stop being surprised by Black death and truly recognize it as the antecedent to our modern life; or what Hartman (Citation2008, 6) calls “the afterlife of property: skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment.” We take up Christina Sharpe’s call to recognize anti-Blackness and state-sanctioned violence against Black people as “the ground we walk on” (7), and with this acceptance, we ask, along with Sharpe: “What kinds of possibilities for rupture might be opened up? What happens when we proceed as if we know this, anti-blackness, to be the ground on which we stand, the ground from which we attempt to speak, for instance, an ‘I’ or a ‘we’ who know, an ‘I’ or a ‘we’ who care?” (7).

The discovery under Baldwin Hall shocked many of us to our core, and also, into action. As Sharpe notes about Black death, we reflected on the familiarity of the violence against Black bodies, our unwillingness to stand by and do nothing, and the need for a new consciousness about what was happening. Sharpe (Citation2016), writes that “thinking needs care (‘all thought is Black thought’) and that thinking and care need to stay in the wake” (5). As such, every conversation we have about Baldwin Hall is in conversation with the tragedy that happened there, those whom it impacts, and what alternative possibilities exist. Scholars like Sharpe allowed us, as a group, to position our understanding of white supremacy from nonwhite locations, while still reflecting from our own individual and varied vantage points. Most importantly, Sharpe demonstrates how white supremacy shapes all social relations, not just that which we perceive as Black.

Sharpe (Citation2016) uses the idea of “the wake” in multiple registers, both material and symbolic. She draws on a wide range of artistic creations, personal remembrances, news stories, and other works to think about the ongoing legacies of slavery. The three moments of “the wake” that Sharpe takes up in her book include: a track left on the water’s surface by a [slave] ship (disturbed flow), a watch or vigil held beside the body of someone who is dead, and the state of wakefulness or consciousness. We engage all of these in relation to the tragedy at Baldwin Hall to understand these three ways we know the wake. First, there is the disturbance of African people abducted, shipped to Turtle Island, and then hired out to work at the University of Georgia. Second, is the vigil which is the discovery of their bodies under a building that caused us to confront Black death, the condition of their lives working on labor camps, and the desecration of their final resting place. Lastly, the consciousness that we can either accept or reject, which comes with the knowledge of our relationship to Black death. The framework of the wake gives us a path to travel as we accept and confront the “disaster of Black subjection” (Sharpe Citation2016, 5). These multiple understandings of the wake also allow us to understand the all-encompassing presence of Black death and violence in and after the tragedy of African enslavement: its history and ongoing presence.

For Sharpe, wake work, what we engage in for the remainder of this paper, is to “imagine new ways to live in the wake of slavery, in slavery’s afterlives, to survive (and more) the afterlives of property… a mode of inhabiting and rupturing this episteme with our known lived and un/imaginable lives (Sharpe Citation2016, 18). Importantly, this requires attention and care. We must remember, reflect, imagine: “The orthographies of the wake [which] require new modes of writing, new modes of making-sensible” (Sharpe Citation2016, 113). But, we cannot just simply mourn what has been done and is being done, Sharpe notes:

At stake then is to stay in this wake time towards inhabiting a blackened consciousness that would rupture the structural silences produced and facilitated by, and that produce and facilitate, Black social and physical death…If we are lucky, the knowledge of this positioning avails us particular ways of re/seeing, re/inhabiting, and re/imagining the world. (22, emphasis added)

In what follows, we use Sharpe’s method of wake work to examine and reflect on how we confronted the Baldwin Hall controversy at UGA. For Sharpe, and for us, we “include the personal here in order to position this work, and myself [ourselves], in and of the wake” (Citation2016, 8). Using personal and collective reflection and remembering, we are able to sit together as though at a wake, to observe, archive and remember Black lives lost to and at UGA in multiple ways that were rendered visceral and material when the bodies of likely enslaved individuals were found at Baldwin Hall and reburied in controversy. We use the metaphor of being in the wake to work through various forms of activism, to teach and learn together about the “accumulated erasures, projections, fabulations and misnamings” of slavery (Sharpe Citation2016, 12). The bringing to light the erasures and evasions of UGA, an institution committed to protecting its image, is a form of wake work, in which we collectively generate a new wakefulness (including this paper).

It is important to note that there are many efforts to address the legacies of slavery and settler colonization at colleges and universities with which our work here is in community. For example, some have proposed reconfigurations in the operations of higher education towards a “third university” that does de-colonial work from inside the colonial institution (paperson Citation2017), while others have created a zine about student activism for racial justice as a means to transform themselves and “subvert oppressive university hierarchies” (Feminist Geography Collective FLOCK Citation2021, 531). Student activism against a confederate monument at University of North Carolina brought “university communities into new ways of seeing” (Menefee Citation2018, 171), while Indigenous resistance to settler knowledge production that violated Anishinaabe religious practices via autopsy has also taken place (Smiles Citation2018).

It is also important to acknowledge and reflect on the fact that five of the six authors of this work identify as white. While Rachelle, who identifies as Black, has always worked alongside white folks, they understand the need for Black leadership when working on behalf of those marked by the wake. Since adopting wake work as our guiding principle, we, Black and white, ask if white people can do wake work. The white co-authors of this paper do not engage in the practice of wake work to appropriate Sharpe’s ideas and methodology. Rather, we use Sharpe’s example to bear witness to the ongoing tragedy of anti-Black violence as beneficiaries of white supremacy and privilege who pledge to callout and actively resist the ongoing violence of slavery. We acknowledge and honor that wake work looks and feels quite different from a white vantage point, yet we know it is critical for all of us to stay awake.

AT THE WAKE: THE UNEARTHING AT BALDWIN HALL

I received an email from two colleagues in early 2018 asking to present on an issue of concern to the Franklin Faculty Senate. As Chair of the Executive Committee, it was me and the other committee members who set the agendas. The issue was Baldwin Hall and the treatment of the human remains found there. I had read some about this in local news media, but did not know all the details. It was clear, however, from both the coverage and the tone of the email that this was a big deal. Sometimes you trust your gut. We put the item on the agenda. The first presentation on Baldwin Hall was made to the Franklin Faculty Senate on February 20th, 2018. Faculty Senators were attentive and asked questions. The Vice President for Research was also there, which was highly unusual. After the presentation, the VP for Research spoke (unexpectedly) for fifteen minutes about “research” that was being conducted on Baldwin Hall - on the DNA of the human remains and also the history of the site. Something felt very wrong. Why are we talking about “research,” I thought? These are human remains of individuals who were likely enslaved or formerly enslaved, that many argue have been inappropriately reburied. This is when I knew we had to do something.—Jennifer

In 2015, the University of Georgia embarked on a $8.7 million expansion project on Baldwin Hall, a building housing the Anthropology Department, Sociology Department, and Criminal Justice Studies. Baldwin Hall, originally constructed in 1938, sits beside the Old Athens Cemetery, which contains the oldest known gravesites in Athens-Clarke County. During the expansion, 105 gravesites were uncovered, containing the remains of 64 bodies (Gresham et al., Citation2019). In initial statements, UGA officials reported that these remains were likely of European descent, but local Black historians questioned that assertion because it was known in the local community that the Old Athens Cemetery was racially segregated, and that the remains uncovered during the construction of Baldwin Hall in 1938 were likely enslaved, or formerly enslaved individuals (Gresham et al., Citation2019).

An Anthropology Professor at UGA excavated and conducted some of the analysis on the human skeletal remains, and also partnered with a lab at the University of Texas that provided some information about ancestry through DNA analysis.Footnote4 This work conducted over several months in 2016 eventually revealed that the vast majority of the remains were likely of African descent (Gresham et al., Citation2019). UGA corrected a previous statement that the remains were likely of European descent, but said nothing about the likelihood of these individuals having been enslaved during their lives based on the age and history of the cemetery.

Less than a week later, officials from UGA directed staff to rebury the remains in Oconee Hill Cemetery, a large and once racially-segregated cemetery with a history of desecration of Black graves and violence to Black mourners. Importantly, this reburial took place with no public notice or consultation, and without the descendant community. In March 2017, moving vans carried the remains of the individuals in wooden coffins and buried them side by side so as to not split up any families. Fred Smith, an important leader in the Athens Black community, looked on in horror from the other side of the locked gate of Oconee Hill Cemetery after receiving an anonymous tip that the reburial would happen that day. He watched solemnly as facilities workers unloaded wooden boxes from a moving truck, until a worker obstructed his vision with a large truck. Greg Trevor defended the campus’s position to not have a ceremony, procession, or audience because, “[they] didn’t want it to turn into a spectacle” (Shearer, Citation2017). The “official” memorial event was planned two weeks later and included prominent African Americans from the community.

This reburial was done despite the repeatedly expressed wishes of members of the local Black community for the remains to be buried in a nearby historically Black cemetery, and to be present for the reburial process (Shearer, Citation2017). While the marker for the grave site finally acknowledged the fact that the humans were likely enslaved or formerly enslaved, members of Athens’ Black community were not invited to the reburial of people they saw as their ancestors. The marker at the grave site reads:

Here lie the remains of 105 unknown individuals, originally interred during the 19th century. The vast majority of the 30 remains able to be identified were those of men, women and children of African descent, presumably slaves or former slaves. Others were of European and Asian descent. Their remains were discovered in November 2015 during the University of Georgia’s Baldwin Hall construction project adjacent to the Old Athens Cemetery. May they continue to rest in peace.

This was a time of great frustration, disbelief, and anger for all of us. It was a visceral reminder that Black people rarely matter and even in death they are subjected to violence as a matter of routine. There was no meaningful acknowledgement of UGA’s past with slavery by a single person in upper administration. But, UGA is where we work and learn; it is a community of experts on history, social justice, and African American studies. How can this be? For many of us, this was the moment we had to confront the ways in which UGA perpetuated white supremacy and anti-Black violence in familiar ways. There was no turning away. This was a moment of keeping watch over the dead. As Sharpe (Citation2016) tells us: “Wakes are processes; through them we think about the dead and our relations to them; they are rituals through which to enact grief and memory” (2016, 21). Those of us writing this paper were at this wake in different ways, but all of us were moved to understand and honor those found at Baldwin Hall. Yet, the act of being present with the dead, honoring the dead, bearing witness to Black death, once again, became the foundation for a larger reflection on who we are, who our institution of work and learning is, and how we might document, resist, and create alternative futures.

It is at this wake that activism surrounding Baldwin Hall began.

IN the WAKE: ACTIVISM REVEALS THE PAST AND PRESENT OF ANTI-BLACK VIOLENCE AT UGA

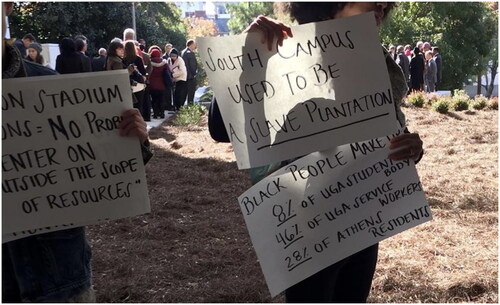

The end of our studio class, held in the Jackson Street Building, is approaching. I eye my watch nervously. I’ll be leaving class early to disrupt a memorial dedication, a direct action intended to highlight the University of Georgia’s refusal to grapple with its legacy of slavery. At 10:30 AM, I reach under a desk and pull out a pile of protest signs, eight in total, sharpied with statements like “UGA presidents, chancellors, and students owned slaves,” and “South Campus used to be a slave plantation.” I slip out of the classroom, walking through a building filled primarily with white students like me, cleaned almost exclusively by Black women. Exiting the building into unseasonably warm November air, I cross the street and meet a group of people in the parking lot of the Main Library. They each take a sign. From our high vantage point in the parking lot, we watch a crowd of formally-dressed people gather under a temporary canopy set up in front of Baldwin Hall. We file under the canopy, joining the crowd, protest signs hidden under our jackets. The president of the university, Jere Morehead, steps up to the podium and begins speaking. I take deep breaths, trying to calm the knot in my stomach and concentrate on what he’s saying. He steps away moments later, never having mentioned the word “slavery,” and we’re pulling out our signs and walking forward. Immediately, some campus police stride towards us. They’re too late to intercept a Black student who heads straight towards Morehead, pulling a ball of cotton out of her pocket and holding it up towards him. “When will UGA acknowledge its history of slavery?” she asks, loudly. Morehead doesn’t look at her and walks towards his seat. She follows, proffering the cotton in her outstretched hand. “This is our material reality,” she repeats again and again. Morehead refuses to make eye contact with her, staring straight ahead.—Alice

Multiple groups challenged the UGA administration’s mishandling of the Baldwin Hall controversy. The UGA Franklin College of Arts and Sciences Faculty Senate formed an Ad Hoc committee on Baldwin Hall to review how the university handled the situation (Schrade, Citation2018). UGA’s Student Government Association Senate passed a resolution calling for several monuments on campus to honor and recognize slaves who worked on and built the university (Schrade, Citation2018). The History Department published an open letter citing the university’s repeated missteps in the Baldwin Hall controversy.

On May 31, 2018, President Morehead responded to criticism by creating an 18-member task force that would meet over the summer to produce a plan to place a memorial on campus to honor the individuals discovered in the slaveFootnote5 burial site at Baldwin Hall; “a move viewed by some as tacit admission that not enough had been done” (Schrade, Citation2018). However, community members, and many of the authors on this paper, would continue to challenge the University’s mishandling and missed opportunity for accountability about the role of slavery on the UGA campus (see ).

The activism of those on this paper and others pushed UGA to acknowledge its past and its present. We wanted the campus to acknowledge its complicity with slavery and segregation, but also address the ongoing frustration by BIPOC students. UGA administration refuses to confront the racist campus climate, dismisses the constant racist incidents that happen year after year that traumatize the few students of color, fails to address the gross under-representation of people of color on campus, and pays poverty wages to Black administrative and cleaning staff. Sitting at the wake, that is Baldwin Hall, brought us to new forms of consciousness and action to address our grievances.

On Monday we asked for the simplest thing: to schedule a meeting to discuss the demands we have made of the university as a coalition of students, staff, faculty, and community members. We walked into the administration building and spoke with a receptionist respectfully at 11 am. She requested 2–3 business days for processing and we then demanded a response by the end of business day. She said she would try and we went on our way. We regrouped at Tate and marched across campus with over 80 students and faculty demanding the University hear our demands. When we reached the admin building the police chief in his usual suit obstructed our entry. He let only six students in at a time and allowed us only to speak with the police. Shocked by their obstruction to a simple follow up, the larger group stayed for longer than planned to protest this escalation. As we started to dwindle in the heat, the leaders addressed the 60+ crowd one more time before dismissing those who did not plan to stay till 5pm. A small, but dedicated, group stayed behind. Needless to say we didn’t get our meeting, but we would be back. After some much needed recuperation, we came back on Thursday for a picnic. It was a lovely day in the blistering sun and we came dressed in our summer best for a restorative picnic on the lawn. At some point we decided to check up on our request for a meeting. A small group of no more than ten walked up the steps to open the door only to again be met with an officer in a suit. We realized the surveillance had been on us the entire time. Six cops, the Associate Dean, and a communications official sat documenting our every move. Caught off guard by this violation, we did not back down. We made the cops explain their closing of a public building before its operating hours had ended. They weaponized the policy for retaliation against us. They said you need to stay in your designated area and the place for expressive activity is not in this building, but we did not come for expressive activity. We came to follow up on our request for a meeting. We soon realized they sent armed guards to block the entry of Black students for the second time into the decision making space of the university. We were not having this and we argued for our right to enter a so-called public building. The cops stuck to their guns and eventually forcibly shoved two students out of the doorway and locked the doors barring our entry into the building. We sat at the steps till 5 with hastily written signs that said they brought guns to our picnic and white supremacy lives here.—Rachelle

Sharpe (Citation2016) includes an entire chapter on “the ship.” The metaphor runs deep and wide, it begs of the reader to reflect on all the ways water behind a [slave] ship is both disturbed and part of the wider ocean processes, also about life on the ship and beyond the ship. This compels us to stay in the wake of the tragedy, the disturbed flow, the movement of bodies. Our activism did these things, even when hard and uncomfortable, but it was done to honor and acknowledge the lives of those unearthed at Baldwin Hall and reburied without their ancestors present. Sharpe writes:

What does it look like, entail, and mean to attend to, care for, comfort, and defend, those already dead, those dying, and those living lives consigned to the possibility of always-imminent death, life lived in the presence of death; to live this imminence and immanence as and in ‘the wake’? (p. 38).

WAKEFULNESS: RECOGNITION, RECONCILIATION, AND REDRESS THROUGH ACTION

Tuesday, April 23, 2019 at 1:32pm I received an email from the Dean of the Franklin College titled “Letter from President Morehead.” I am preparing to conduct a Faculty Senate meeting at 3:30pm the same day to discuss the Ad Hoc Committee on Baldwin Hall’s report that was released to Senators and the public a week prior. This is the first opportunity Senators had to review and ask questions about the report and its recommendations. Yet, the President of the University has already offered a response—one that came just hours before I am to conduct this important and high-stakes meeting. It states “I express my disappointment in the unfair narrative that the ad hoc committee’s report continues to promulgate three and a half years after the discovery of the remains at the Baldwin Hall construction site.” It goes on to say that the report is an “investigation filled with rumor and anonymous sources.” For the first time in my experience working on the Faculty Senate on the issue of Baldwin Hall I feel scared, and I am afraid to conduct the meeting. Why is the President getting involved in this way, at this time, and before we have even met as a Senate? Why am I getting this just hours before our meeting? I call my best friend telling her I am not sure I can go to the meeting. She tells me to “put my big girl pants on” and go conduct the meeting. I do, and the Senate accepts the Report 32-0-1 and agrees to move to recommendations for redress at the next meeting.—Jennifer

Months of activism, led by UGA students including authors of this paper, supported by many faculty, staff, and local residents, put the issue of Baldwin Hall into the public discourse. The Morton theater, a famous African American relic, screened a documentary, Below Baldwin: How an Expansion Project Unearthed a University’s Legacy of Slavery that told of the slave burial grounds on campus and the campuses inadequate response. A letter written by students and local activists, including authors of this paper, echoed the concerns and demands of Athens Black community for recognition and redress of slavery and its aftermath on campus. The letter called out the university and ended with three clear demands from the university:

Issue a public statement taking responsibility for UGA’s role in white supremacy and fully fund the faculty-proposed Center on SlaveryFootnote6 as a first step toward researching and telling the whole story of UGA’s role in slavery and Black oppression, a legacy which persists to this day.

Guarantee full-tuition, all-fees-included scholarships for descendants of the enslaved people who worked on UGA’s campus and for every African-American student who graduates from a public high school in Athens as a first step toward redressing the longstanding reparational debt that UGA owes to the African-American community and the local public schools in Athens.

Implement wages of at least $15/hour for all full-time and part-time/temporary UGA employees as a first step toward sufficiently supporting workers, especially Black workers who are disproportionately underpaid at UGA. As the largest employer in Athens and the flagship university in Georgia, UGA sets a standard for wages across the community and the state. The current inadequate wages fuel poverty in Athens’ Black communities, and UGA must do more to address the massive racial wealth gap.

Another place of action came from the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences Faculty Senate. In April of 2019, the Senate voted to formally accept the “Report from the Ad Hoc Committee on Baldwin Hall to the Franklin College Faculty Senate.” This document extensively describes and officially documents the concerns of faculty and others about the way human remains were handled at Baldwin Hall. The report is the product of more than one year of research by a committee of five UGA professors across the Art and Sciences; a committee of faculty created by the Faculty Senate at large. The report exists as an officially adopted record of events, many of which have been repeatedly dismissed and disputed in public forums by upper administration. Author, Jennifer, presided over the Senate as Executive Committee Chair, then Senate President, throughout the process.

Consistent with the charge of the Franklin Faculty Senate, the report had to focus on faculty concerns, but many of these extend into the local Athens community and the likely descendant community. While the organizing and activism previously discussed were significantly important in calling attention to the issue and making public demands for redress, this report stands as the only formally adopted investigation that highlights mistakes and harms. It serves as an archive at UGA and in the community.

The 120 page report is significant.Footnote7 It described the historical details from the initial discovery of human remains, to the decisions by administration on handing and reburial, to thelack of communication and consultation with the general public and likely descendant community, to the timeline for which the committee was formed and charged. The report identifies seven major concerns held by faculty, including “Secrecy and Lack of Community Consultation,” “Official Responses to Valid Faculty Criticism,” and “Intimidation and Policing of Faculty Teaching Activities” related to the history of slavery at UGA. While the report is focused and described in terms of faculty concerns, it should be noted that the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences includes faculty with expertise in areas that shed light on and confirm wrongdoings (e.g. historical preservation, racial injustice, history of the southern US, archeology, anthropology, geography, etc.).

Furthermore, the report made three formal recommendations that were adopted by the Franklin Faculty Senate on October 15, 2019. These include an apology to the descendant community from President Morehead because the “descendant community [was] not sufficiently respected by UGA’s manner of exhuming, reburying, and researching the graves and human remains discovered in the Old Athens Cemetery,” commencing of public consultation with the descendant community about human remains still buried near Baldwin Hall and additional DNA analysis being conducted, and an apology from the UGA public relations office regarding critical comments made about a junior professor who questioned UGA’s actions. What is important about the report is that it lives in the permanent archive—the official record—much to the dislike of upper administration.

Many other events and actions have also taken place to continue to render visible the violence inflicted on enslaved Africans buried at Baldwin Hall before and after death, as well as how those harms extend to the present-day community that are also part of this story. In reflecting on the Senate’s role in producing wakefulness about the issues, we are reminded of Sharpe’s (Citation2016, 106) “the weather,” that is how anti-Black violence is pervasive as a climate” (ibid). In considering what came out of the organizing, activism, and protest of 2018 and 2019, we are able to see achievements and advancements that must also be understood as in the wake, as coming to consciousness. To bring consciousness, wakefulness to this ongoing tragedy at UGA, the Senate report serves as a type of “Black annotation and redaction”—“towards seeing and reading otherwise; towards reading and seeing something in excess of what is caught in the frame” (Sharpe Citation2016, 117). In the years and months since the adoption of the Franklin Senate report, the documentary, circulation of the letter, the impact of the protest, the surveillance at the picnic, a restorative circle at the slave burial site, the narrative of Baldwin Hall has been annotated to include the full history of what happened. We hope this will lead to future moments of redaction, where we can move into understanding the imaginable lives of African lives at UGA as more than just forced laborers.

It is in this state of wakefulness, that we see pathways for recognition, reconciliation, and redress of the harms done by slavery at UGA and beyond.

CONCLUSION: EMBRACING WAKE WORK THROUGH RADICAL PEDAGOGY

I am a member of the Coalition for Recognition and Redress and I’m tired. I’m tired of the racial violence both symbolic and material, close in proximity to my person and far away. I’m tired of the obstinance of this university in the face of truth tellers of white supremacist violence on this campus that is both past and present. But most of all I have just had a busy week. Besides the teaching and the grading I do, I am now fighting my university for things they should have already done, things that shouldn’t take a fight. I shouldn’t have to fight for a Southern institution of higher learning to tell the truth about slave holders whose names are on many of their buildings, whose statue is on north campus, whose paintings are hanging up in the hallways, and whose whitewashed story plasters the campus. I shouldn’t have to demand the university invest with dollars and cents in the people it has harmed and the Black students of this community. I shouldn’t have to tell the university to pay its own workers a living wage so they can live in this city too. But, alas, I do because it is our duty to fight for our freedom. This is no time for despair. This week we flexed our people power. We believe we have a duty to fight for our freedom as the ancestors of those who had their lives paved over by white supremacy and their graves desecrated in death. And as the ancestors of abolitionists who fought and died for Black freedom, we are our ancestor’s wildest imaginations who remind us to not be afraid of our freedom dreams of a more just and equitable world but to go out and build them. We do not make these demands lightly. The campus thinks it has the upper hand here, but we will not be so easily moved because as Assata Shakur taught us, it is our duty to fight for our freedom and it is our duty to win. We must love and protect one another. That love for each other and our freedom dreams will always keep us coming back to demand equity from those at the seat of power.—Rachelle

Sharpe’s method of wake work asks us to grapple with the ongoing reality of Black death in the legacy of slavery’s afterlife. White supremacy continues to shape institutions, including the university within which we work, and Black death continues to be ignored. Exclusion, regulation, and “abjection from the realm of the human” (Sharpe Citation2016, 14) continues to shape the way UGA enacts anti-Blackness, which is deeply related to the violence done to Indigenous peoples who once lived on this land. Sharpe calls us to understand that we daily attend the wake of Black death, which works in the ongoing afterlives of slavery and that being called to consciousness of this reality requires action. For the authors of this paper, becoming aware of the abjection of Black remains from the realm of the human at Baldwin Hall revealed the conditions of white supremacy that shape the institution in which we work and learn and required action (see ).

FIGURE 4 Student group, Beyond Baldwin, leads march for the University to adopt its “Racial Justice Demands” in April of 2019. Large banner reads “Face Our Past to Free Our Future.”

This “wake work” began with conversations in our classroom about the exhumation of the bodies and their reburial that then sparked wider activism on campus and leadership in the Faculty Senate to address the University’s mishandling of the process. The University of Georgia and the surrounding town of Athens was founded as a colonial settler project, an agenda it continues to perpetuate, while paradoxically claiming to be a diverse and inclusive community. Our experiences engaging with Sharpe’s wake work has given us the language to break the silence about the racial violence we have witnessed as students, faculty, and members of the Athens community. Through sharing personal reflection and theoretical analysis of racial violence perpetrated by our university and town, we hope to annotate the record and counter the illusion of fairness and meritocracy that UGA insists on centering. This is work that must continue to be done in the wake of Transatlantic slavery and ongoing Black death.

We ask ourselves everyday how to continue wake work in the high and low points of our lives, the changing trajectories of our individual locations, and the waxing and waning momentum of community activism. We want to start with recognition of the progress of our university that has been made in the months after the height of our activism. We recognize the University for officially joining the Universities Studying Slavery (USS) consortium. We hope members of campus, at all levels from students, to faculty, to upper administration, will fully participate in the mission of the consortium and continue to understand the lives of enslaved Africans forced to work at the university and in town. We also recognize that UGA’s President provided personal funds to support the History of Slavery at the University of Georgia (HSUGA) project that authors Rachelle and Jennifer participated in and remain involved.Footnote8 The College of Education was renamed for a Black alumni, Mary France Early, in 2019.

We reiterate demands that the University of Georgia create reparational scholarships for Black students.Footnote9 We also recommend the university work with the Athens-Clarke County to fund and staff an Athens Black History Museum. UGA should support the efforts of the Athens-Clarke County Justice and Memory Project. We still ask the President to implement wages of at least $15/hour for all full-time and part-time/temporary UGA employees with an annual wage increase that matches inflation. One issue that weighed on the hearts of minds of organizers is the demoralizing campus climate for students of color who deal with racist incidents on campus multiple times a year. Reparational scholarships could do more harm than good if the campus climate remains as it is. We suggest adopting a zero-tolerance policy for hate speech, intimidation, and harassment that could punish and allow for the re-education of students who commit heinous acts of racism that make the campus unsafe for BIPOC students. The university must invest in diversifying the faculty and staff so that students of color have mentors and role models that understand and can teach to their experience. Moreover, the campus must put the full power and weight into supporting K-12 education in Athens-Clarke County and create meaningful pathways for Athens-Clarke County students to attend UGA. UGA (and all universities) need to find ways to return land to the Indigenous communities from which it was stolen, as well as to the descendants of slavery who built and maintained the university for so many years.

We would like to end this paper by offering some recommendations to other universities and their faculty, students, staff, and community members fighting for justice.

Build momentum through relational organizing and public pressure.

Be sure that the leaders of your movement represent the frontline communities whose oppression you plan to confront.

Be relentless and unwavering in not only your demands, but how you demand them.

Be prepared for the backlash.

Build community and strong relationships around your shared values.

By using Sharpe’s method of personal reflection we have been able to render ourselves visible as a part of the system that maintains the status quo of racist education institutions but also as wake workers attempting to intervene in the mathematics of Black life that equates to Black violence not only in life but in death. We hope that more academics will turn to the personal as a means to examine the politics of higher education that we exist in that maintain white supremacist heteropatriarchy in our classrooms, departments, universities, and student body. We choose this difficult work because we believe in the mission of public higher education and, we are committed to making higher education better for ourselves, our students, and our communities.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rachelle Berry

RACHELLE BERRY is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography, Planning, and Environment at East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina 27858. E-mail [email protected]. Their research focuses on how racial justice organizing can create opportunities for reparational justice, healing, and transformation for Black Geographies.

Jennifer L. Rice

JENNIFER L. RICE is an Associate Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, 30602. E-mail [email protected]. Her research examines urban climate justice and resisting climate apartheid, as well as racial justice in the wake of settler-colonial urbanization and higher education.

Amy Trauger

AMY TRAUGER is a Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602. E-mail [email protected]. Her research interests are on the relationship between food, land, and justice.

Haley DeLoach

HALEY DELOACH in an Independent Scholar, Athens, Georgia 30602. E-mail [email protected].

Amelia H. Wheeler

AMELIA H. WHEELER is a teacher at Joy Village School, Athens, Georgia, 30605. E-mail [email protected].

Alice Hilton

ALICE HILTON in an Independent Scholar, Lexington, Kentucky, 40502. E-mail [email protected].

Notes

1 We use the language of the university – “likely enslaved or formerly enslaved individuals”– which may sound as if we doubt the certainty of the claim of enslavement, but we do so under duress. Community claims and historical analysis of the gravesite specify African ancestry and leave little room to question this assertion, and even more importantly, this phrase makes space for the possibility of freedom in this time period for these individuals, no matter how unlikely.

2 We do not claim that the history presented here is comprehensive or complete. Rather, we focus on aspects of UGA’s past that many students, faculty, and staff rarely know or acknowledge as a part of the history of UGA, and more importantly, many in Administration refuse to critically interrogate at the time this was written.

3 Significant activism has taken place around Linnentown in the past several years, and Athens-Clarke County has issued an apology and created a Justice and Memory Project to examine methods of atonement. UGA, however, denies any wrongdoing and has issued no apology or taken any steps to redress harm done to Linnentown descendants.

4 It should be noted that some experts suggest the practice of assessing ancestry, race, or ethnic background from skeletal remains is highly fraught and unreliable. However, stories from local Black residents and historical analysis of the configuration of the cemetery also suggest the bodies found are of African ancestry.

5 Our wording here acknowledges the reality that Baldwin Hall and its parking lot represent a slave burial site in ways the administration has never acknowledged

6 Proposal from the Working Group for the Study of Georgia Slavery and its Legacies at the University of Georgia

7 Full report can be read here: https://www.franklin.uga.edu/sites/default/files/Faculty%20Senate%20ad%20hoc%20committee%20report%204-17-19.pdf

8 For the HSUGA project, students collected names of enslaved Africans from the wills of university alumni, who likely hired those slaves out to the university and also conducted a two day symposium on “Recognition, Reconculliation, and Redress.” See: www.SlaveryatUGA.org.

9 We understand there are legal restraints to using race as a category for admission, but we ask the university to look to Texas for their program that has won all challenges at the Supreme Court for their use of race within university admissions.

REFERENCES

- Athena Co-Learning Collective. 2021a. Rehumanizing the graduate seminar by embracing ambiguity. Gender, Place, and Culture 28 (4):564–75.

- Athena Co-Learning Collective. 2021b. Toward emergent scholarship: Aligning classroom praxis with liberatory aims. Antipode Interventions Online. https://antipodeonline.org/2021/02/10/toward-emergent-scholarship/.

- Athena Co-Learning Collective. 2018. A femifesto for teaching and learning radical geography. Antipode Interventions Online. https://antipodeonline.org/2018/11/27/a-femifesto-for-teaching-and-learning-radical-geography/.

- Besel, P. 2018. University of Georgia Desegregation Riot (1961). Black Past. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/university-georgia-desegregation-riot-1961/.

- Davis, R. 2017. Elijah Clarke. New Georgia Encyclopedia. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/elijah-clarke-1742-1799/.

- Donovan, S. 2019. Franklin Faculty Senate discusses calling for UGA President Morehead to address handling of Baldwin Hall remains. Red and Black. https://www.redandblack.com/uganews/franklin-faculty-senate-discusses-calling-for-uga-president-morehead-to-address-handling-of-baldwin-hall/article_4168db94-da2f-11e9-ad28-3f90bd621a01.html.

- Downey, M. 2021. Opinion: University of Georgia stonewalls racial justice and reckoning. The Atlanta-Journal Constitution. https://www.ajc.com/education/get-schooled-blog/opinion-university-of-georgia-stonewalls-racial-justice-and-reckoning/OEK7UUC2KRAWBHV2VGRDQB5QTE/.

- Dunbar-Ortiz, R. 2014. An Indigenous peoples’ history of the United States (Vol. 3). Boston: Beacon Press.

- Flock, F. G. C. 2021. Making a zine, building a feminist collective: Ruptures I, student visionaries, and racial justice at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 20 (5):531–61.

- Georgia Historical Quarterly. 1943. Elijah Clearke’s “Trans-Oconee Republic.” 27 (3):285–9.

- Georgia Studies Images. n.d. Georgia Performance Standard SS8H5. https://georgiainfo.galileo.usg.edu/gastudiesimages/Indian%20Cessions%20Map.htm.

- Gresham, T. H., L. J. Reitsema, K. A. Mulchrone, and C. J. Garland. 2019. Archaeological exhumation of burials in the Baldwin Hall portion of the Old Athens Cemetery, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia: Final report. Available online: https://www.architects.uga.edu/home/historic-preservation/archaeology.

- Hartman, S. 2008. Lose your mother: A journey along the Atlantic slave route. New York: Macmillan

- Jean-Charles, R. M. 2018. Occupying the center: Haitian girlhood and wake work. Small Axe 22 (3):140–50. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/710218.

- Kalaji, D. 2021. Georgia’s past and present: 100th anniversary vigil of the lynching of John Lee Eberhart. Red and Black. https://www.redandblack.com/athensnews/georgia-s-past-and-present-100th-anniversary-vigil-of-the-lynching-of-john-lee-eberhart/article_da652812-732f-11eb-8a92-efb244b64542.html.

- Kelderman, E. 2021. Georgia’s campuses will continue to honor people who had ties to slavery and racism. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/georgias-campuses-will-continue-to-honor-people-who-had-ties-to-slavery-and-racism.

- Lay, S. 2020. Ku Klux Klan in the Twentieth Century. New Georgia Encyclopedia. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/ku-klux-klan-in-the-twentieth-century/.

- Lee, R., and T. Ahton. 2020. Land-grab universities expropriated Indigenous land is the foundation of the land-grant university system. High County News. https://www.hcn.org/issues/52.4/indigenous-affairs-education-land-grab-universities.

- Liang, S. 2020. Understanding the history of Native American land in Athens. Sustainable UGA. https://sustainability.uga.edu/stories/native-american-land-in-athens/.

- McKittrick, K. 2006. Demonic grounds: Black women and the cartographies of struggle. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Menefee, H. 2018. Black Activist geographies: Teaching Whiteness as territoriality on campus. South: A Scholarly Journal 50 (2):167–86.

- Miranda, G. 2020. Black student organizations form union to strengthen voices. Red and Black. https://www.redandblack.com/uganews/black-student-organizations-form-union-to-strengthen-voices/article_1c6db10c-c467-11ea-a762-ff8778e6564b.html.

- Mohanty, C. T. 2003. Feminism without borders: Decolonizing theory, practicing solidarity. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Native Land. 2021. Native Land Digital. https://native-land.ca/.

- New York Times. 2017. College Mobility Project: University of Georgia. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/projects/college-mobility/university-of-georgia.

- paperson, L. 2017. A third university is possible. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Posey, K. 2020. An updated list of UGA buildings named after racist figures. The Red and Black. https://www.redandblack.com/uganews/an-updated-list-of-uga-buildings-named-after-racist-figures/article_ef52b270-b42c-11ea-9608-0f9f99f783c3.html.

- Saunt, C. 1999. A new order of things: Property, power, and the transformation of the Creek Indians, 1733–1816. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Saunt, C. 2020. Unworthy republic: The dispossession of Native Americans and the road to Indian Territory. New York: WW Norton & Company.

- Schrade, B. 2018. After missteps and criticism, UGA to honor memory of slaves on campus. Atlanta Journal-Constitution. https://www.ajc.com/news/state–regional/after-missteps-and-criticism-uga-honor-memory-slaves-campus/dja1Kp61WyTrzzr7BNsRkI/.

- Sharpe, C. 2016. In the wake: On Blackness and being. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Shearer, L. 2017. Sting of death: UGA's handling of Baldwin Hall remains faces criticism. https://www.onlineathens.com/story/news/state/2017/03/11/sting-death-uga-s-handling-baldwin-hall-remains-faces-criticism/15431921007/.

- Smiles, D. 2018. … to the Grave”—Autopsy, settler structures, and indigenous counter-conduct. Geoforum 91:141–50. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.02.034.

- Smith, A., H. Funaki, and L. MacDonald. 2021. Living, breathing settler-colonialism: The reification of settler norms in a common university space. Higher Education Research & Development 40 (1):132–45. doi:10.1080/07294360.2020.1852190.

- Social Explorer Dataset. n.d.a. Census 1920, digitally transcribed by Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. Edited, verified by Michael Haines. Compiled, edited and verified by Social Explorer.

- Social Explorer Dataset. n.d.b. Census 1930, digitally transcribed by Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. Edited, verified by Michael Haines. Compiled, edited and verified by Social Explorer.

- Tolnay, S., and E. Beck. 2020. Lynching. New Georgia Encyclopedia. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/lynching/.

- University of Georgia. 2017. Birthplace of higher education. https://www.franklin.uga.edu/news/stories/2017/birthplace-higher-education.

- University of Georgia. 2020. UGA factbook. Office of Institutional Research. https://oir.uga.edu/_resources/files/factbook/pages/UGAFactBook_p21.pdf.

- University System of Georgia. 2022. Board of Regents Policy Manual (Section 4.1.6). https://www.usg.edu/policymanual/section4/C327/#p4.1.6_admission_of_persons_not_lawfully_present_in_the_united_states.

- US Census. 2021a. QuickFacts Georgia. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/GA.

- US Census. 2021b. QuickFacts Clarke County Georgia. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/clarkecountygeorgia.

- Whitehead, H. T. 2021. Giving voice to Linnetown. Grayson, GA: Tiny Tots and Tikes.

- Wilkerson, I. 2016. The long-lasting legacy of the Great Migration. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/long-lasting-legacy-great-migration-180960118/.

- Wood, B. 2021. “Slavery in Colonial Georgia.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/slavery-in-colonial-georgia/.