Abstract

This study explores the presence of different moral natures—neutral, good, bad, ambivalent—and its association with sociodemographic characteristics in 3 television genres, through content analysis (N = 3,993). Results show that morally ambivalent characters dominate the cast of fiction, whereas neutral characters form a majority in news and information programming. In all genres, morally ambivalent characters are typed by social and professional transgression, while morally bad characters are typed by transgressions of the law. Although two thirds of all transgressions are punished, morally bad characters are always punished, whereas morally ambivalent characters more often get away without consequences.

Introduction

Television has traditionally focused on affirming and rewarding good characters and their deeds and punishing and bringing to justice evil and transgressive characters (Gerbner, Citation1995; Raney, Citation2005). From that vantage point, it seems that television has undergone a significant change: The morally ambivalent character (MAC) has become more and more present in popular television fiction and film, such as The Sopranos, Mr. Robot, Dexter, Mad Men, Breaking Bad, and House MD (Raney & Janicke, Citation2013). The popularity of MACs has begun to cause concern in the public debate as well as a vested interest in the academic community (Askar, 2013; Polatis, Citation2014). One concern about the content that includes MACs is that the morally conflicted content might tarnish the viewer’s moral compass, and as a result might lead to audience members not understanding the difference between right and wrong (Askar, 2013; Polatis, Citation2014). Although generally an ethical appraisal of the behavior of good and bad characters leads to a positive or negative valence, this is obviously more complex with MACs who intermix good and bad behavior and are not always punished when they exhibit bad behavior (Konijn & Hoorn, Citation2005; Raney & Janicke, Citation2013). Therefore, the fear of moral relativism and a progression toward situational ethics that permeate these debates (cf. Fletcher, Citation1966; Kamtekar, Citation2004) can be considered from a social learning perspective as well as a cultivation perspective (Bandura, Citation1977; Hastall, Bilandzic, & Sukalla, Citation2013). Taken together, these concerns about MACs are a new addition to the public and scientific debates about morality and television. This issue starts with the assumption that through the indirect experiences encountered through media exposure, viewers might get a distorted image of what is considered socially normal, good or bad in society (Bandura, Citation1977; Gerbner, Citation1995).

The primary interest of the academic community in MACs has mostly been part of an endeavor to better understand media enjoyment and not public morality (e.g., Eden, Grizzard, & Lewis, Citation2011; Krakowiak & Oliver, Citation2012; Krakowiak & Tsay-Vogel, Citation2013). Most of the studies, grounded in the affective disposition theory, find that moral considerations are central to character liking which then influences enjoyment (Raney, Citation2005; Zillmann & Bryant, Citation1975). The affective disposition theory formula would suggest that viewers would disapprove of ambivalent characters’ actions, and their enjoyment would correspondingly decrease. However, some research suggests that this does not seem to be the case (Krakowiak & Tsay-Vogel, Citation2013; Raney & Janicke, Citation2013).

Given the focus of the academic community on the possible effects MACs might have on viewer enjoyment and the prevalence of these characters it suggests, there are very few systematic studies of the actual prevalence of these characters in the television landscape as a whole. Some case studies have focused on the morally ambivalent main characters in television fiction (e.g., De Wijze, Citation2008; Keeton, Citation2002), and one systematic study revealed an increase of morally ambivalent characters in fiction over time (Daalmans, Hijmans, & Wester, Citation2013). Taken together, these studies reveal nothing about the presence of people of differing moral natures in the complete cast of TV. Furthermore, most studies also seem to tie moral ambivalence strongly to the realm of television fiction, while one might also argue that these characters are so well liked because they resemble people in real life who also hold both good and bad characteristics (Konijn & Hoorn, Citation2005; Krakowiak & Oliver, Citation2012). Last, because the way we consume television has radically changed over the past decade and distinct genre preferences might guide our viewing patterns (cf. Bilandzic & Rössler, Citation2004), differentiating between the moral casting in distinct genres could reveal genre-specific conceptions of the (non)ethical behavior that is cultivated through the examples of good, bad, and ambivalent characters. As such, this study is the first to focus on exploring and describing the presence of moral ambivalence in the Dutch television landscape, and assessing whether there are differences between genres.

Theoretical frame

People today are born into a symbolic environment with television as its main source of daily information, thereby bringing virtually everyone into a shared culture. This shared culture is created (in part) through storytelling. Humans live in a world experienced, created, and maintained largely through many different forms of storytelling (Fisher, Citation1984; Gottschall, Citation2012; Lévi-Strauss, Citation1979). Storytelling thus plays a vital role in the (informal) enculturation of humans in society and stories are seen as one of the primary vehicles for the ritual maintenance of society’s cherished morals and values over time (Carey, Citation1975). Before the mass media were instated, parents or community elders would tell stories to younger generations, like myths, to explain how the world works (Rosengren, Citation1984). Today, television acts as our main storyteller, integrating individuals into the established social order by offering certain models about appropriate values, behaviors, norms and ideas (Gerbner, Citation1995). As such, television is a product of society as ruminator, masticating essential categories and contradictions in everyday life through a message system of repetitive stories that preserve and legitimate the society’s identity and social order.

In other words, television tells us “about life, people, places, striving, power, fate and family life. It presents the good and the bad, the happy and sad, the powerful and the weak, and lets us know who or what is a success or a failure” (Signorielli & Morgan, Citation2001, p. 335). As a result, televised stories represent what and who counts as good, important and valuable in our culture, through selecting and highlighting some aspects of our culture and some persons in our culture more frequently and diversely than others (Gerbner, Citation1995).

As outlined before, whereas a dramatic increase in morally ambivalent lead characters in contemporary television fiction was noted (Eden, Grizzard, & Lewis, Citation2011; Krakowiak & Oliver, Citation2012), there is no indication of how moral nature is represented in other genres. Television fiction boasts traditional heroes and villains, or good and bad characters, and also a plethora of morally ambivalent characters (Daalmans, Hijmans, & Wester, Citation2013). For news and information programming and reality and entertainment programming, this empirical differentiation in terms of morality is lacking. While one might assume that the traditional categorization of good and evil, for objectivity’s sake, would be a hallmark for news and information programming (Baym, Citation2000), there is no evidence to substantiate this. Furthermore, some researchers have proposed that the popularity of reality genres might be due to the prevalence of morally ambivalent behavior (Krakowiak & Oliver, Citation2012), suggesting that the cast of reality and entertainment programming might include many morally ambivalent persons. All in all, there is a lack of clarity regarding the moral casting of persons in different genres, leading to the following research question:

Research Question 1: Does the distribution of characters with various moral natures (i.e., good, bad, and ambivalent) differ across genres?

Previous research has shown that the television world overrepresents certain demographic groups (i.e., adult men), while it under-represents others (i.e., women, elderly adults, children), and as an aggregate these television messages transform into societal messages of moral worth (Gerbner, Gross, Signorielli, & Morgan, Citation1980). Furthermore, research by Koeman and colleagues (Citation2007) provided evidence that in the Dutch television world there are distinct genre differences in the degrees of over and under representation of certain sociodemographic groups. These degrees of differences might lead to the cultivation of genre-specific societal messages of moral worth (cf. Cohen & Weiman, Citation2000). These results, coupled with the idea of moral casting (Gerbner, Citation1995), leads to the question of how moral nature is distributed over these groups and if there are genre-specific differences. Furthermore, when considering the fears about viewer moral judgments becoming more relaxed as a result of seeing moral ambivalence and moral relativism (Askar, Citation2011; Polatis, Citation2014), coupled with the notion that people tend to emulate those who are like themselves, it becomes important to assess what sociodemographic characteristics characters with varying moral natures in different television genres have (Rai & Holyoak, Citation2013). This then leads to the second research question:

Research Question 2: Are there differences between genres in the association between moral nature and gender, age, and ethnicity?

Television articulates and reveals the moral nature of its characters through their actions, and more importantly how they are judged and punished for those actions by the various communities they are a part of (Grabe, Citation2002; Hastall, Bilandzic, & Sukalla, Citation2013). A study by Daalmans, Hijmans, and Wester (Citation2014) revealed that morality was connected to the actions of people and characters, either through transgression of commonly shared laws, norms and values or by exemplifying commonly shared ideals by their behavior. Research by Grabe (Citation2002) also pointed in this direction, given that it revealed that in The Jerry Springer Show all of the committed social transgressions were punished either via the audience or the host, thereby reestablishing the moral order.

Research into popular reality programming focused on transforming subjects reveals that the narrative of these shows is often preoccupied with subjects being seen as transgressing the boundaries of what is deemed as normal or morally good (Inthorne & Boyce, Citation2010; Rich, Citation2011; Skeggs & Wood, Citation2012). Examples of this can be seen in programs focused on regulating the obese body (e.g., The Biggest Loser), parents who neglect proper nutrition in the meals of their children (e.g., Honey, We’re Killing The Kids), and improperly dressed men and women (e.g., What Not To Wear). The value of normal, and moral personhood is regimented not by punishment in a straightforward sense, but by rules and advice and inciting shame and guilt—in essence, social punishment (Skeggs & Wood, Citation2012).

All in all, previous research has revealed distinct combinations of transgressions of the law, social transgressions as well as professional transgressions and subsequent forms of punishment in fictional television as well as specific types of reality programming. The literature lacks an examination of the transgression-punishment representation in the news and informational genre; an examination of the transgression-punishment representation in the reality genre as a whole (which is more than just transformational reality TV); and a comparison of possible differences in the representation of transgression and punishment in the different genres directly informed by the notion that different genres might cultivate specific moral worldviews (Bilandzic & Rössler, Citation2004). This leads to the last two research questions of the present study:

Research Question 3: Are there differences between genres in the association between moral nature and committed transgressions?

Research Question 4: Are there differences between genres in the association between moral nature and the punishment that follows transgressions?

Method

The main research goal of this study was to explore the differences between genres regarding the representation of moral nature in prime time television. To meet this goal, a quantitative content analysis was conducted in 2012, on the basis of a sample of Dutch primetime television programs (N = 485).

Sample

This study analyzed a large-scale sample of primetime television programming (6 p.m.–12:00 a.m.) aired in the Netherlands. The clustered sample includes 485 programs, from 10 channels (public: NL 1, 2, and 3; commercial: RTL 4, 5, 7 and 8 as well as Net5, Veronica and SBS6 aired on seventy consecutive evenings broadcasted in the period between March 19 and May 27 of 2012.

Coding procedures

The programs were first coded for general information, the first being channel (either public or commercial), and the second being genre cluster of the program (i.e., News and Information—which included news broadcasts, consumer programs and documentaries; Entertainment—which included reality programs, lifestyle programs, quizzes and game shows; and Fiction—included comedy, soaps, psychological drama and crime drama; Daalmans, Hijmans, & Wester, Citation2014; Emons, Citation2011). The third aspect that was coded was the origin of the program (i.e., the Netherlands, the United States, Germany, Great-Britain, France, other, not able to code).

The unit of analysis was the main persons and main characters of the program. For non-fictional programming, this meant that we coded the figures represented who had the most speaking and/or screen time during the show (up to eight per show). For nonfictional content, we coded up to ten items per program, on the basis of the idea that the most prominent, newsworthy, and/or most morally laden items would be featured first in both news and entertainment (cf. Hill, Citation2005; Scott & Gobetz, Citation1992). For fictional programming, the main characters of the main storyline were coded (up to eight per show), on the basis of the assumption that they are the carriers of the most important storyline and therefore embody important moral characteristics. A main character was defined as a character who plays a leading role, is the carrier of a storyline and is thereby indispensable to the narrative (Egri, Citation1960; Weijers, Citation2014).

For the main persons (figures) and characters, we coded demographic categories, transgression, consequences and moral nature. The coding categories for gender of the main character were male; female; male animated/creature; female animated/creature or other (Emons, Citation2011). In the analysis, only the categories (human) male and female were used. The coding category for age of the main character reflected five life cycles, and the coders were instructed to establish the age of the character by determining which age group or life stage (i.e., child: 0–12 years, teenager: 13–18 years, young adult: 19–29 years, adult: 30–64 years, or elderly adults: 65 years and older) the character was supposed to represent (Emons, Citation2011; Koeman, Peeters, & D’Haenens, Citation2007). Age was later recoded in the analysis by combining child and teenager and maintaining the other categories. Ethnicity was coded as Caucasian/White, Black, Asian, Mediterranean—Arabic, Mediterranean—Europe, South/Latin American, or other (Emons, Citation2011; Koeman et al., Citation2007). For the analysis, Mediterranean—Europe, South/Latin American, and other categories were combined in the other category because of low cell frequencies. For each character, the variable transgression was coded to discern whether the character committed any transgression (yes/no). If a transgression was committed, then it was coded as what type of transgression it was: transgression of law, professional transgression or a social transgression (Daalmans, Hijmans, & Wester, Citation2013; Grabe, Citation2002; Hastall, Sukalla, & Bilandzic, Citation2013). The presence of each or these types of transgressions was recorded individually, since one person or character could commit more than one type of transgression. Furthermore, these three types of transgression were also divided into subcategories (for example, transgression of the law was divided as a coding category into violent offence, sexual offence, financial offence or other transgression of the law). The coders were instructed that they could only code behavior as transgressive if the behavior was unambiguously transgressive within the predefined forms of transgression (i.e., law, profession or social) and/or if other characters (visually or verbally) condemned or identified the behavior of the character as such (the underlying idea being that we are held accountable by others). In the analysis, the different types of transgressions were recoded as dichotomous variables (transgression of the law: yes/no, professional transgression: yes/no, social transgression: yes/no). When the presence of a transgression was coded, then the consequences of the transgression were also coded in the following categories: no, consequences, transgression is punished, transgression is rewarded, transgression produces mixed/ambivalent consequences, and other. Consequences were later recoded for analysis into no, consequences, punishment, reward, and other.

The moral nature of each main character was coded as good, bad, ambivalent, neutral or unable to code. Moral nature had to be determined by behavior of the person/character (i.e., transgressions committed) as well as the verbal judgment of persons/characters of that behavior. Good persons/characters were categorized as such if they were good in their goals, motivations, intentions, and other observable behavior (i.e., they committed no transgressions or only minor transgressions) and they received no criticism or other negative judgments from others. Bad persons/characters were categorized as such if their observable behavior could be typed as evil or bad (in goals, motivations or intentions), if they committed severe transgressions and were judged for them by others. Ambivalent persons/characters were categorized as such if their observable behavior is categorized by both good and bad with regard to goals, intentions and motivations (for example doing the wrong things for the right reasons), as exemplified by the verbal praise of judgment from others. Neutral persons/characters have no goals, commit no transgressions and function purely as a source of (professional) information in an item (the reporter in the news broadcast, the weatherman in the news, the person informing viewers about the statistics of the stock market of the day).

Coder training and reliability

The coding itself was part of a specialized seminar on the methodology of content analysis for undergraduate students in Communication Science, in the spring of 2013. Forty coders took part in the data collection. After several weeks of discussion, around 30 hours of intensive in-class coder training as well as independent practice on programs that were not part of the sample, and reliability checks, they coded a sample of 485 programs. The coders worked individually, and around 20% (n = 105) of the programs in the present sample were double-coded. Coders consulted the primary researcher when there was disagreement, which was then resolved by the researcher. On the basis of this overlap, the levels of inter-rater reliability were calculated using the macro by Hayes and Krippendorff (Citation2007). Taking Krippendorff’s criteria for acceptable (.67) and good (.80) interrater reliability (Citation2007, p. 241). The Krippendorff’s alphas were good overall, ranging from .91 to 1.00.

Results

The sample of 485 programs contained a total of 1,278 items (i.e., fictional storylines or items in nonfictional programming) for analysis. News and information programs supplied 684 items (53.5%) in the sample, 482 items (37.7%) were classified as part of an entertainment program, and 112 items (8.8%) were classified as the main storyline in a fiction program.

The total cast that was coded in the sample consisted of 3,993 persons (N = 3,993). Of the cast 62.8% was male (n = 2507), and 37.2% was female (n = 1486). The age-composition of the cast was made up as follows: children 2.9%, teenagers 4.4%, young adults 29.1%, adults 57.5% and seniors 6.1%. The ethnic make-up of the cast consisted persons that were 85% White, 4.7% Black, 2.4% Asian, 4.0% Mediterranean—Arabic, 1.6% Mediterranean—Europe, 2.0% South/Latin American, and 0.3% other ethnicities.

Moral nature

The results concerning moral nature revealed an overall significant difference between genres regarding the distribution of persons and characters of various moral natures (χ2[6], N = 3993) = 1149.962, Cramer’s V = .379, p < .001). Overall, two thirds of the persons and characters (61.4%) were categorized as neutral, a small fifth was categorized as ambivalent (19.3%), 17% were categorized as good, and a very small portion (2.3%) were categorized as bad.

The adjusted standardized residuals revealed distinct genre differences that deviated from this overall pattern. Comparatively, news and information had an overrepresentation of neutral persons and characters (n = 1,364, 85.9%, adjusted residual = 25.9, p < .001), followed by very small portions of good (n = 111, 7.0%), ambivalent (n = 100, 6.3%), and bad persons (n = 12, 0.8%). Almost two thirds of the persons and characters in the entertainment genre were coded as neutral (n = 966, 58.0%), a small portion as bad (n = 20, 1.2%) and almost a fifth of the cast as morally ambivalent (n = 320, 19.2%). Comparatively, the cast of entertainment hosts had an overrepresentation of morally good persons and characters (n = 360, 21.6%, adjusted residual = 6.5, p < .001). The results for the fictional genre revealed it to be a mirror image of news and information, since it comparatively has an overrepresentation of morally good (n = 209, 28.2%, adjusted residual = 9.0, p < .001), morally bad (n = 60, 8.1%, adjusted residual = 11.7, p < .001) and morally ambivalent characters (n =351, 47.4%, adjusted residual = 21.5, p < .001). Neutral characters comprised only 16.2% of the cast of fiction, which was the lowest proportion comparatively.

Moral nature and demographic characteristics

Gender

The results with regard to the distribution of the various moral natures over male and female persons and characters (see ), revealed that overall there are significant gender differences in the moral make-up of prime time programming (χ2[3], N = 3,993) = 26.817, Cramer’s V = .082, p < .001). Men were significantly overrepresented as neutral (adjusted residual = 3.3, p < .001) and bad (adjusted residual = 2.5, p < .001), while women were significantly overrepresented as good persons and characters (adjusted residual = 4.4, p < .001). The overall results showed a relative gender-neutrality when it comes to moral ambivalence.

Table 1. Combined Overview of Genre Differences in Association of Moral Nature and Gender.

The results also revealed that there were significant gender differences in the moral make up within the cast of the news and information genre (χ2[3], N = 1,587) = 14.204, Cramer’s V = .095, p < .01). For news and information, the adjusted standardized residuals revealed that contrary to the overall pattern, neutral females (adjusted residual = 3.4, p < .01) and good men (adjusted residual = 2.1, p < .01) were overrepresented, while the overrepresentation of bad men (adjusted residual = 2.3, p < .01) was in line with the described overall pattern for prime time programming as a whole.

For the entertainment genre, the results also indicated significant gender differences in the moral makeup of the cast (χ2 (3, N = 1666) = 16.806, Cramer’s V = .100, p < .01). In line with the described overall pattern, the cast of entertainment programs revealed an overrepresentation of neutral men (adjusted residual = 3.9, p < .01) and good women (adjusted residual = 2.9, p < .01). Contrary to the overall pattern of gender neutrality in moral ambivalence, the cast of entertainment programming also showed an overrepresentation of ambivalent women (adjusted residual = 2.0, p < .01).

Last, the fictional genre also revealed gender differences in the moral make up of its cast (χ2[3], N = 740) = 15.267, Cramer’s V = .144, p < .01). Similar to the overall pattern, analyzing the cast of fiction shows revealed an overrepresentation of good women (adjusted residual = 3.3, p < .01) and bad men (adjusted residual = 2.0, p < .01), and contrary to the overall pattern of gender neutrality regarding moral ambivalence, there was an overrepresentation of ambivalent men (adjusted residual = 2.4, p < .01).

In sum, each genre revealed a unique gender pattern in the distribution of moral natures. News and information harbored an overrepresentation of good men, while good women were overrepresented in the entertainment and fictional genre. And while the fictional genre revealed no gender differences in moral neutrality, the news and information genre held an overrepresentation of neutral women and entertainment held an overrepresentation of neutral men. The association of males with moral badness held up in the news and information genre as well as the fictional genre, but there were no gender differences in badness in the entertainment genre. And while overall and in the news and information genre, moral ambivalence is seemingly gender-neutral, the entertainment cast boast an overrepresentation of ambivalent females and fiction of ambivalent males.

Age

The results with regard to the distribution of the various moral natures over the different age categories (see ) revealed that overall there were significant age differences in the moral make-up of prime time programming (χ2[9], N = 3993) = 159.026, Cramer’s V = .115, p < .001). Overall, the results revealed a pattern of exceeded expected frequencies for neutral adults (adjusted residual = 9.0, p < .001), neutral seniors (adjusted residual = 2.9, p < .001), good children and teenagers (adjusted residual = 4.0, p < .001), good young adults (adjusted residuals = 6.0, p < .001), bad adults (adjusted residual = 2.2, p < .001), and ambivalent young adults (adjusted residual = 8.0, p < .001).

Table 2. Combined Overview of Genre Differences in Association of Moral Nature and Age.

The results comparing the moral make up of casts and age revealed that there were significant age differences in the moral make up within the cast of news and information (χ2[9], N = 1,587) = 55.957, Cramer’s V = .108, p < .001). Similar to the described overall pattern, the cast of news and information programming showcased an overrepresentation of neutral adults (adjusted residual = 3.5, p < .001) and good young adults (adjusted residual = 5.9, p < .001). Contrary to the overall patterns, the cast of news and information programming also had an overrepresentation of neutral children and teenagers (adjusted residual = 2.4, p < .001) and bad young adults (adjusted residual = 2.0, p < .001).

With regard to the cast of entertainment programming, the results indicated significant age differences in its moral makeup (χ2[9], N = 1,666) = 110.453, Cramer’s V = .149, p < .001). Similar to the described overall pattern, the cast of entertainment program hosts revealed an overrepresentation of neutral adults (adjusted residual = 6.2, p < .001), neutral seniors (adjusted residual = 2.2, p < .001), good children and teenagers (adjusted residual = 6.7, p < .001), and ambivalent young adults (adjusted residual = 7.5, p < .001).

The cast of fictional programming also revealed significant age differences in its moral make up (χ2[9], N = 740) = 43.722, Cramer’s V = .140, p < .001). In line with the pattern described for prime time programming as a whole, within the cast of fictional programs good young adults (adjusted residual = 2.9, p < .001) and bad adults (adjusted residual = 4.0, p < .001) exceeded expected frequencies, while contrary to the overall pattern, the results also revealed exceeded expected frequencies for neutral children and teenagers (adjusted residual = 4.3, p < .001) in fiction.

In sum, each genre revealed a distinctly different age distribution in moral natures. For the news and information genre, the most dominant moral nature in all age categories was moral neutrality. The news and information cast also revealed an overrepresentation of good and bad young adults and an age neutrality for moral ambivalence. For the entertainment genre, the cast revealed an overrepresentation of good children and teenagers, neutral adults and seniors and ambivalent young adults as well as an age neutrality for moral badness. Last, in the fiction category, the results revealed an overrepresentation of neutral children and teenagers, good young adults and morally bad adults and relative age-neutrality for moral ambivalence.

Ethnicity

The chi-square analyses revealed significant overall differences in the distribution of the various moral natures over the different categories of ethnicity (see ) in prime time programming as a whole (χ2[12], N = 3,993) = 39.132, Cramer’s V = .057, p < .001). The results revealed a pattern of overrepresentation for neutral Arabic persons and characters (adjusted residual = 2.5, p < .001), bad Arabic persons and characters (adjusted residual = 2.9, p < .001), and ambivalent Black persons and characters (adjusted residual = 2.4, p < .001).

Table 3. Combined Overview of Genre Differences in Association of Moral Nature and Ethnicity.

Results also demonstrated significant differences for the news and information genre regarding the distribution of the various moral natures over the different categories of ethnicity (χ2[12], N = 1,587) = 36.404, Cramer’s V = .087, p < .001). Adjusted standardized residuals revealed that similar to the described overall pattern, the news and information category showcased an overrepresentation of bad Arabic persons and characters (adjusted residual = 5.0, p < .001).

For the cast of entertainment programming, results also indicated significant differences in the distribution of the various moral natures of characters over the different categories of ethnicity (χ2[12], N = 1,666) = 62.404, Cramer’s V = .112, p < .001). Contrary to the pattern described for prime-time programming, the reality genre showed an overrepresentation of neutral White persons and characters (adjusted residual = 3.1, p < .001) and bad Black persons and characters (adjusted residual = 3.0, p < .001). In line with the overall pattern, the results revealed an overrepresentation of ambivalent Black persons and characters (adjusted residual = 2.8, p < .001) and bad Arabic persons and characters (adjusted residual = 2.0, p < .001) for entertainment programming.

Last, for the cast of fictional programming, the results also revealed significant differences in the distribution of various moral natures over the different categories of ethnicity (χ2[12], N = 740) = 26.256, Cramer’s V = .109, p < .05). Contrary to the pattern described for prime time programming as a whole, fictional programming revealed an overrepresentation of ambivalent Whites (adjusted residual = 2.7, p < .05) and neutral Asians (adjusted residual = 2.5, p < .05).

Overall, we saw an overrepresentation of neutral and bad Arab persons and characters and ambivalent Black persons and characters. In the news, we only saw an overrepresentation of bad Arab persons and characters; in the entertainment genre, neutral Whites, bad Arabs and bad and ambivalent, Blacks were overrepresented. Last, fiction revealed an overrepresentation over neutral Asians and White ambivalence.

Moral nature, transgressions, and punishment

In the presentation of the results on transgression and consequences, it is important to note the absence of neutral persons and characters (who have no goals, commit no transgressions). In general, of the total cast of 1,543 persons that were either good, bad or ambivalent 48.2% (n = 744) committed a transgression. Distinct genre differences in transgressive behavior became clear when we considered the division of the cast along the line of inclusion of transgressors. For the news and information genre, 36.3% (n = 81) of cast members committed a transgression. Of the entertainment cast, 40.6% (n = 284) committed a transgression, and of the fictional cast, 61.1% (n = 379) committed a transgression. Analyzing the cast of fictional genre revealed a much larger proportion of transgressive persons than either the news and information or the entertainment genre.

The overall results revealed significant differences between the persons and characters of various moral natures and the perpetration of transgression (χ2[2], N = 1543) = 1102.938, Cramer’s V = .845, p <.001). Of the total cast of bad characters, a majority committed a transgression (n = 89, 96.7%, adjusted residual = 9.6, p < .001). Of the total cast of ambivalent characters, 84.3% (n = 650, adjusted residual = 28.4, p < .001) committed a transgression and of all of the good characters, a negligible amount committed a transgression (n = 5, 0.7%). This overall pattern of significant differences between the good persons and characters who committed virtually no transgressions and the large proportions of the cast of bad and ambivalent persons and characters who did commit transgressions was found for all the individual genres (news and information: χ2[2], N = 223) = 119.966, Cramer’s V = .733, p < .001, entertainment: χ2[2], N = 700) = 501.568, Cramer’s V = .846, p <.001, fiction: χ2[2], N = 620) = 474.946, Cramer’s V = .875, p < .001).

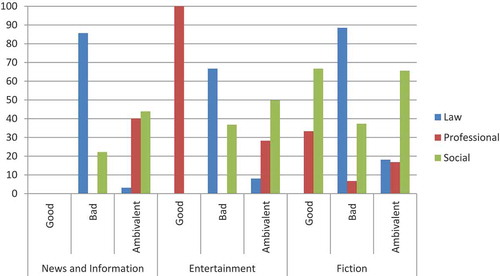

This association between moral nature and transgressions was further explored by analyzing the three distinct sets of transgressions (transgression of the law, professional transgression and social transgression) in general and per genre (see ). Overall, the results revealed that of the very small amount of good persons who committed a transgression in general (n = 5), these transgressions were made up out of professional transgressions and social transgressions. For the bad characters who committed a transgression, the majority of those transgressions were transgressions of the law, followed by social transgressions and a small proportion of professional transgressions. For ambivalent transgressors, the majority of transgressions was social in nature, followed by professional transgressions and a small proportion of transgressions of the law.

Figure 1. Combined overview of types of transgressions committed by persons of various moral natures per genre.

The overall results revealed a significant overrepresentation of morally bad characters in the category of transgressions of the law (adjusted residual = 14.4, χ2[2], N = 673) = 208.792, Cramer’s V = .557, p < .001), a significant overrepresentation of morally ambivalent characters in the category of professional transgressions (adjusted residual = 3.9, χ2[2], N = 736) = 18.444, Cramer’s V = .158, p < .001) as well as a significant overrepresentation of morally ambivalent characters in the category of social transgressions (adjusted residual = 3.9, χ2[2], N = 654) = 14.913, Cramer’s V = .151, p < .01). In sum, overall it seems that morally bad characters can be typed by their association with transgressions of the law, whereas ambivalent characters can be typed by their association with both professional and social transgressions.

The results for types of transgression committed by persons of various moral natures per genre () revealed interesting similarities and differences from the overall presented distribution.

For the news and information genre, the results revealed significant differences between the various moral natures in the committing of a transgression of the law (χ2 (1, N = 71) = 43.048, Cramer’s V = .779, p < .001), and professional transgressions (χ2[2], N = 80) = 6.154, Cramer’s V = .277, p < .05). In line with the overall pattern, the results for the news and information genre showcased an overrepresentation of morally bad characters who committed transgressions of the law (adjusted residual = 6.6, p < .001), and morally ambivalent characters who committed a professional transgression (adjusted residual = 2.5, p < .05). With regard to social transgressions committed in the news and information genre, there were no significant differences between the different moral natures in committing them (χ2[2], N = 67) = 2.198, Cramer’s V = .181, p > .05).

For the entertainment genre, the results revealed significant differences between the various moral natures of the people committing of a transgression of the law (χ2[2], N = 254) = 48.176, Cramer’s V = .436, p < .001), and professional transgressions (χ2[2], N = 283) = 10.393, Cramer’s V = .192, p < .01). In line with the overall pattern, the results for the entertainment genre showcased an overrepresentation of morally bad characters who committed transgressions of the law (adjusted residual = 6.9, p < .001), and morally ambivalent characters who committed a professional transgression (adjusted residual = 2.3, p < .01). With regard to social transgressions committed in the entertainment genre, similar to the results reported for the news and information genre, there were no significant differences between the different moral natures in committing them (χ2[2], N = 231) = 2.110, Cramer’s V = .096, p > .05).

Last, for the fictional genre, the results revealed significant differences between the various moral natures in the committing of a transgression of the law (χ2[2], N = 348) = 108.648, Cramer’s V = .559, p < .001), and social transgressions (χ2[2], N = 356) = 16.645, Cramer’s V = .216, p < .001). In line with the overall pattern, the results for the fictional genre showcased an overrepresentation of morally bad characters who commit transgressions of the law (adjusted residual = 10.4, p < .001), and morally ambivalent characters who committed a social transgression (adjusted residual = 3.9, p < .001). With regard to professional transgressions committed in the fictional genre, unlike the results reported for both the news and information and the entertainment genre, there were no significant differences between the different moral natures in committing them (χ2[2], N = 373) = 4.728, Cramer’s V = .113, p > .05).

For the characters who committed transgressions, there was the possibility that that transgression would be followed by consequences. As can be seen in , overall the results revealed significant differences between persons and characters of various moral natures and the consequences they faced for their transgressions (χ2 (6, N = 720) = 13.438, Cramer’s V = .097, p < .05).

Table 4. Combined Overview of Genre Differences in Association of Moral Nature and Consequences.

Overall, of all the transgressors, 64.7% were punished for their transgression, 27.1% faced no consequences, 3.1% were rewarded and 5.1% faced ambivalent consequences for their transgression.

Overall, the adjusted standardized residuals revealed an overrepresentation of no consequences for ambivalent persons and characters (adjusted residual = 2.5, p < .05) that had committed a transgression as well as bad persons and characters that were punished for their transgressions (adjusted residual = 3.5, p < .05). The results for the genres news and information and entertainment indicated no significant differences between the consequences of persons and characters of various moral natures faced for their transgressions. The cast of fiction, however, did reveal significant differences in the consequences faced by persons and characters of different moral natures (χ2 (6, N = 365) = 17.402, p < .01). Similar to the overall pattern, the fictional cast had a significant overrepresentation of ambivalent persons and characters (adjusted residual = 2.6 p < .01) that had committed a transgression and faced no consequences as well as bad persons and characters that were punished for their transgressions (adjusted residual = 4.0, p < .01).

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to shed light on the possible genre specific differences in the representation of moral nature in prime-time programming. Following a recent trend in cultivation research that argued that specific genres might cultivate specific moral messages for viewers (cf. Bilandzic & Rössler, Citation2004), a distinction was made between the genre clusters of news and information, entertainment and fiction. The moral content and moral casting of these genres were compared and contrasted.

The distribution of moral natures differed significantly between genres; the most striking results were the predominance of neutral characters in news and information and entertainment programming as well as the much more moral diverse cast and dominance of ambivalent characters in fiction. These results might be explained by the ambitions that the different genres have; news and information as a genre strives to inform its viewers in an unbiased manner, which might translate into moral neutrality for most of the persons it presents, while fictional programming might use the ambivalent characters as fuel for increasingly complex plots (Baym, Citation2000; Mittel, Citation2006).

When reflecting on these results from a moral growth perspective, the diverse cast of television (and especially fiction) might be argued to prompt moral reflection, moral deliberation and thereby moral growth in viewers. Turiel (Citation1983) described viewers as moral scientists who construct and simulate social experience to develop their ideas about right and wrong. The diverse moral casting might—through mechanisms such as narrative transportation, identification, empathy and temporary expansion of the self (Eden, Daalmans, & Johnson, Citation2015; Lewis, Tamborini, & Weber, Citation2014; Shedlosky-Shoemaker, Costabile, & Arkin, Citation2014; Slater, Johnson, Cohen, Comello, & Ewoldsen, Citation2014)—function as a moral laboratory (Ricoeur, Citation1984) or moral playground (Vorderer, Klimmt, & Ritterfeld, Citation2004). In this moral laboratory, viewers are prompted by the behavior of characters both virtuous and not so virtuous to explore, reflect upon and deliberate about moral issues without facing the consequences of actually making those moral decisions in real life (Krijnen, Citation2007). Mar and Oatley (Citation2008) also argued that interacting with narrative content—whether fictional or not—encourages empathetic growth and the transmission of (ethical) knowledge about the social world through the vicarious experience.

Aside from the possibility of the diverse moral casting prompting moral deliberation and reflections during viewing as a leisure activity, previous research has also argued that MACs challenge perceptions of right and wrong in various private, professional and societal contexts (Van Ommen, Daalmans, & Weijers, Citation2014; Weaver, Salamonson, Koch, & Porter, Citation2012; Weaver & Wilson, Citation2011). Therefore, programs featuring MACs might also prove to be a useful tool in ethics education to introduce and discuss ethical dilemmas in an accessible way.

With regard to the gender differences between moral natures, the results revealed a predominant (proportional) association of women with good and ambivalent moral natures in the entertainment and fictional programming. These results are in line with the gender differences reported for fiction (Daalmans, Hijmans, & Wester, Citation2013). Furthermore, the results also indicate an association of men with moral neutrality overall, and in entertainment and news and information programming. These results might be seen as in line with male moral authority also reported in previous studies (Gerbner, Citation1995), thereby maintaining stereotyped gender roles and attributions of (moral) worth and power in the social world (cf. Eagly & Steffen, Citation1984).

Age differences between the genres indicated that overall adulthood was associated with moral ambivalence in fiction and entertainment and moral badness in fiction, while moral neutrality was the dominant category for all ages except in fiction. With regard to ethnicity, striking differences were found when comparing the genres. Both the news and information as well as the entertainment genre featured overrepresentations of Arabic in the morally bad category, while entertainment also showcased White moral neutrality and Black badness and ambivalence. These results are largely in line with the results reported by Chiricos and Eschholz (Citation2002), and Mastro and Greenberg (Citation2000), who indicated that ethnic minorities are more often associated with criminality than Whites are and are thus assigned the role of perpetrator or villain. It is surprising that fiction showed an overrepresentation of White ambivalence. White ambivalence (for example, Walter White in Breaking Bad and Don Draper in Mad Men) is a phenomenon that is also noticed by television critics (Wayne, Citation2014). For example, Todd van der Werff (Citation2013) argued that the popularity of White morally ambivalent characters should be seen as “a movement dominated by singular White men, whose combination of ruthlessness, inherently sympathetic nature and sexual charisma has led them to deeper and darker things.” All in all, the messages of moral categorization in different genres reveal strikingly different color palettes, which might be problematic for the limited and damaging views people with distinct genre preferences could cultivate about different ethnic groups (cf. Gerbner, Citation1995).

It is rather unsurprising that, in all genres, bad and ambivalent characters were dominant in committing transgressions. Overall, and in all genres, morally bad characters are typed by their association with transgressions of the law, while morally ambivalent characters were tied to the “less severe” professional and social transgressions. Two thirds of all transgressions were punished. In addition, all morally bad lawbreakers were always punished, and ambivalent characters who committed mostly professional and social transgression sometimes went unpunished. Furthermore, punishment for the transgressions of bad characters was proportionally much more frequent in fiction than in any of the other genres. These results reveal a more straightforward moral lesson presented in the fiction genre than in news and information or entertainment. Lawbreakers and criminals were punished, which reinforces (and simultaneously cultivates) viewers’ desire for a belief in a just world (Shrum, Citation1999). Television ritualizes transgressive events—particularly transgressions of the law—and their punishment with functional implications for the maintenance of social order. From a functionalist (Durkheimian) perspective, television clearly reproduces guidelines of acceptable and unacceptable (ethical) behavior in society, through the unambiguous punishment of unlawful behavior (Grabe, Citation2002; Krijnen, Citation2007). Simultaneously, the somewhat less strict enforcement of punishment for professional and social transgressions suggest that MACs potentially offer motives and insight into the moral reasoning behind their transgressions, therefore making some transgressions acceptable (Konijn & Hoorn, Citation2005). Thus, the fears concerning viewers’ moral judgments becoming more relaxed as a result of seeing moral ambivalence and moral relativism can be tempered.

As with all studies, this study was not without limitations, which open up interesting avenues for further research. The choice to code only the main storyline for fiction resulted in differing of the subsample sets. Although the comparisons in the study were based on relative proportions, a more complete picture of television’s public moral discourse would have been created by coding all fictional storylines.

Even though our sample was very diverse in genres, it was also characterized to a large degree by news and information programming that was of Dutch origin, while the entertainment and fiction programming was to a large degree of American or other Anglo-Saxon origin. One might expect national differences between and within the genres if it contains a large degree of foreign-made programs, since “every country’s television system reflects the historical, political, social, economic, and cultural contexts within which it has developed” (Gerbner, Gross, Jackson-Beeck, & Signorielli, Citation1978, p. 178). However, Dutch broadcasters may simply select American programs that resemble Dutch productions; after all, media organizations want a large audience and will arguably choose programs in line with what they see as the Dutch audience’s conceptualization of public morality.

Despite its limitation, the presented explorative study of genre differences in moral content in television programs provides a first empirical base for further research into differences between and in genres regarding the representation of moral natures. More research is still needed to fully flesh out the differences regarding the representation of moral natures within the larger genre clusters, and the potential implications these genre differences in the representation of morality might have for viewers at large as well as viewers with distinct genre preferences that are enabled by technological changes in the media landscape (DVR, TiVo). Because television and its stories continue to serve an important source in the unconscious moral education of viewers (Bandura, Citation1977; Gerbner, Citation1995), moral constitutions will continue to be questioned and debated, and continued explorations of television’s moral content will remain vital to inform the disputes ahead about the relationship between television and morality in our society.

References

- Askar, J.G. (2011). The rise of the anti-hero on TV and the impact it could have on kids. Deseret News. Retrieved from http://www.deseretnews.com/article/700208623/The-rise-of-the-anti-hero-on-TV-and-the-impact-it-could-have-on-kids.html?pg=all

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Baym, G. (2000). Constructing moral authority: We in the discourse of television news. Western Journal of Communication, 64, 92–111.

- Bilandzic, H., & Rössler, P. (2004). Life according to television. Implications of genre-specific cultivation effects: The gratification/cultivation model. Communications, 29(3), 295–326.

- Carey, J. (1975). A cultural approach to communications. Communication, 2, 1–22.

- Chiricos, T., & Eschholz, S. (2002). The racial and ethnic typification of crime and the criminal typification of race and ethnicity in local television news. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 39(4), 400–420.

- Cohen, J., & Weiman, G. (2000). Cultivation revisited: Some genres have some effects on some viewers. Communication Reports, 13(2), 99–114.

- Daalmans, S., Hijmans, E., & Wester, F. (2013, August). The good, the bad, and the ambivalent? Exploring the moral nature of fiction characters over time. Paper presented at the annual conference of the Association for the education of Journalism and Mass Communication, Washington, DC.

- Daalmans, S., Hijmans, E., & Wester, F. (2014). “One night of prime time”: An explorative study of morality in one night of prime time television. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 29(3), 184–199.

- De Wijze, S. (2008). Between hero and villain: Jack Bauer and the problem of dirty hands. In J. H. Weed, R. B. Davis, & R. Weed (Eds.), 24 and philosophy: The world according to Jack (pp. 17–30). Oxford, England: Blackwell.

- Eagly, A. H., & Steffen, V. J. (1984). Gender stereotypes stem from the distribution of women and men into social roles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(4), 735–754.

- Eden, A., Daalmans, S., & Johnson, B. K. (2015, November). From hero to zero: Morality predicts enjoyment but self-expansion predicts appreciation of morally ambiguous characters. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Communication Association, Las Vegas, NV.

- Eden, A., Grizzard, M., & Lewis, R. (2011). Disposition development in drama: The role of moral, immoral and ambiguously moral characters. International Journal of Arts and Technology, 1(4), 33–47.

- Egri, L. (1960). The art of dramatic writing. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Emons, P. (2011). Social-cultural changes in Dutch society and their representations in television fiction, 1980–2005. Nijmegen, The Netherlands: Knust.

- Fisher, W. R. (1984). Narration as a human communication paradigm: The case of public moral argument. Communications Monographs, 51(1), 1–22.

- Fletcher, J. F. (1966). Situation ethics: The new morality. Westminster, UK: John Knox Press.

- Gerbner, G. (1995). Casting and fate. Women and minorities on television drama, game shows and news. In E. Hollander, P. Rutten, & L. van der Linden (Eds.), Communication, culture & community. Liber amicorum James Stappers (pp. 125–137). Houten, The Netherlands: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

- Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Jackson-Beeck, M., & Signorielli, N. (1978). Cultural Indicators: Violence Profile n. 9. Journal of Communication, 28(3), 176–207.

- Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Signorielli, N., & Morgan, M. (1980). Aging with television: Images on television drama and conceptions of social reality. Journal of Communication, 30, 37–47.

- Gottschall, J. (2012). The storytelling animal: How stories make us human. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Grabe, M. E. (2002). Maintaining the moral order: A functional analysis of “The Jerry Springer Show.” Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 19(3), 311–328.

- Hastall, M. R., Bilandzic, H., & Sukalla, F. (2013, June). Are there genre-specific moral lessons? A content analysis of norm violations depicted in four popular television genres. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, London.

- Hayes, A. F., & Krippendorff, K. (2007). Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication Methods and Measures, 1, 77–89.

- Hill, A. (2005). Reality TV: Audiences and popular factual television. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Inthorne, S., & Boyce, T. (2010). “It’s disgusting how much salt you eat!” Television discourses of obesity, health and morality. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 13(1), 83–100.

- Kamtekar, R. (2004). Situationism and virtue ethics on the content of our character. Ethics, 114(3), 458–491.

- Keeton, P. (2002). The Sopranos and genre transformation: Ideological negotiation in the gangster film. New Jersey Journal of Communication, 10(2), 131–148.

- Koeman, J., Peeters, A., d’Haenens, L. (2007). Diversity Monitor 2005: Diversity as a quality aspect of television in the Netherlands. Communications: the European Journal of Communication Research, 32, 97–121.

- Konijn, E. A., & Hoorn, J. F. (2005). Some like it bad: Testing a model for perceiving and experiencing fictional characters. Media Psychology, 7, 107–144.

- Krakowiak, M. K., & Oliver, M. B. (2012). When good characters do bad things: Examining the effect of moral ambiguity on enjoyment. Journal of Communication, 62(1), 117–135.

- Krakowiak, K. M., & Tsay-Vogel, M. (2013).What makes characters’ bad behaviors acceptable? The effects of character motivation and outcome on perceptions, character liking, and moral disengagement. Mass Communication & Society, 16, 179–199.

- Krijnen, T. (2007). There is more(s) in television: Studying the relationship between television and the moral imagination. Docotral dissertation, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Amsterdam.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1979). Structural anthropology. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

- Lewis, R. J., Tamborini, R., & Weber, R. (2014). Testing a dual‐process model of media enjoyment and appreciation. Journal of Communication, 64, 397–416.

- Mar, R. A., & Oatley, K. (2008). The function of fiction is the abstraction and simulation of social experience. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(3), 173–192.

- Mastro D., & Greenberg, B. S. (2000). The portrayal of racial minorities on prime time television. Journal of Broadcasting Electronic Media, 44, 690–703.

- Mittell, J. (2006). Narrative complexity in contemporary American television. The Velvet Light Trap, 58, 29–40.

- Polatis, K. (2014). Why moral ambiguity is popular on TV and the big screen. Retrieved from http://national.deseretnews.com/article/1640/Why-moral-ambiguity-is-popular-on-TV-and-the-big-screen.html#WHAFjJUVkYB77dbw.99

- Rai, T. S., & Holyoak, K. J. (2013). Exposure to moral relativism compromises moral behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(6), 995–1001.

- Raney, A. A. (2005). Punishing media criminals and moral judgment: The impact on enjoyment. Media Psychology, 7, 145–163.

- Raney, A. A., & Janicke, S. (2013). How we enjoy and why we seek out morally complex characters in media entertainment. In R. Tamborini (Ed.), Media and the moral mind (pp. 152–169). London, England: Routledge.

- Rich, E. (2011). ‘I see her being obesed!’ Public pedagogy, reality media and the obesity crisis. Health, 15(1), 3–21.

- Ricoeur, P. (1984). Time and narrative (Vol. 1). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Rosengren, K. E. (1984). Cultural indicators for the comparative study of culture. In G. Melischek, K. E. Rosengren, & J. Stappers (Eds.), Cultural indicators: An international symposium (pp. 11–47). Vienna, Austria: Verlag der Osterreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Scott, D. K., & Gobetz, R. H. (1992). Hard news/soft news content of the national broadcast networks, 1972–1987. Journalism Quarterly, 69, 406–412.

- Shedlosky-Shoemaker, R., Costabile, K. A., & Arkin, R. M. (2014). Self-expansion through fictional characters. Self and Identity, 13, 556–578.

- Shrum, L. J. (1999). Television and persuasion: Effects of the programs between the ads. Psychology and Marketing, 16(2), 119–140.

- Signorielli, N., & Morgan, M. (2001). Television and the family: The cultivation perspective. In J. Bryant & J. A. Bryant (Eds.), Television and the American family (pp. 333–351). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Skeggs, B., & Wood, H. (2012). Reacting to reality television: Performance, audience and value. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Slater, M. D., Johnson, B. K., Cohen, J., Comello, M. L. G., & Ewoldsen, D. R. (2014). Temporarily expanding the boundaries of the self: Motivations for entering the story world and implications for narrative effects. Journal of Communication, 64, 439–455.

- Turiel, E. (1983). The development of social knowledge: Morality and convention. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Van der Werff, T. (2013). ‘Breaking Bad’s racial politics: Walter White, angry White man. Retrieved from http://www.salon.com/2013/09/22/breaking_bads_racial_politics_walter_white_angry_white_man/.

- Vorderer, P., Klimmt, C., & Ritterfeld, U. (2004). Enjoyment: At the heart of media entertainment. Communication Theory, 14(4), 388–408.

- Wayne, M. L. (2014). Ambivalent anti-heroes and racist rednecks on basic cable: Post-race ideology and White masculinity on FX. Journal of Popular Television, 2(2), 205–225.

- Weaver, R., Salamonson, Y., Koch, J., & Porter, G. (2012). The CSI effect at university: Forensic science students’ television viewing and perceptions of ethical issues. Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences, 44(4), 381–391.

- Weaver, R., & Wilson, I. (2011). Australian medical students’perceptions of professionalism and ethics in medical television programs. BMC Medical Education, 11(50), 1–6.

- Weijers, A. (2014). The craft of screenwriting. Den Haag, The Netherlands: Boom Lemma Uitgevers.

- Zillmann, D., & Bryant, J. (1975). Viewer’s moral sanction of retribution in the appreciation of dramatic presentations. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 11, 572–582.