ABSTRACT

In this article we first explore the concept of ‘multi-stakeholderism’, focusing on how the term was understood when internet governance was first envisioned. We then elaborate on how the concept has evolved in recent years. The focus of the article here, given the shift in how cyberspace is treated by state actors – increasingly as a domain of conflict. We detail how the United Nations (UN) has approached international peace and security online since 2004, via a series of ad hoc working groups that have been largely exclusive to a small number of state participants, and the expansion of interstate conflict online during this same period.

The article also introduces a number of informal initiatives that have been spearheaded by multi-stakeholder groups outside the auspices of the UN since 2018 – the Charter of Trust, the Cybersecurity Tech Accord, the Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace, the Contract for the Web, and the Let’s Talk Cyber dialogue series – focusing on the role of the private sector in particular to promote peace and security online. Finally, the article explores what could help ensure that the next generation of cybersecurity dialogues at the UN are structured to address escalating conflict in cyberspace and to take full advantage of external voices in this effort.

1. Introduction: the internet as a multi-stakeholder experiment

The internet continues to be the greatest experiment in human history – a global network for connectivity and sharing of information that has been built, maintained and enabled by a wide range of multi-stakeholder partners. Whether we trace its origins to the original ARPANET in the 1960s, or to the founding of the World Wide Web in 1989, the internet itself has always been defined by a (sometimes awkward) collaboration amongst and between governments, private industry and academia (Leiner et al., Citation1997, pp. 3–7) – and increasingly broader elements of civil society.

Simply put, the internet itself is not really one network but instead a massive composite of smaller, independently managed networks that are connected by shared communications protocols. As information and communications instantaneously transmit between networks and across borders, there are many overlapping responsibilities and equities. Much, if not most, of the physical infrastructure and intellectual property that defines cyberspace continues to be privately owned by a wide range of technology companies, and the internet protocols themselves are supported by technical standards and resource assignment organizations like the Internet Society (ISOC) and the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) (Internet Governance Project, Citation2018). Meanwhile, governments set a range of regulatory and legal expectations on everything from data privacy, to content moderation, to issues of commerce and trade online, that are enforced by the relevant authorities. Finally, civil society groups play an increasingly essential watchdog role in highlighting concerns surrounding accountability, human rights, safety and access as cyberspace becomes integral to daily life around the world.

This multi-stakeholder governance structure has progressed over the years, alongside the evolution of the internet itself, but its core postulates persist to this day. Many of these are now nearly two decades old, established by the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) in 2003 and 2005 (ITU, Citation2009). WSIS was a United Nations-sponsored summit on information society that aimed to bridge the global digital divide. It took place across two phases. The 2003 Summit failed to agree on the future of the internet governance but adopted a ‘Declaration of Principles’ (Citation2003) and a Working Group on Internet Governance (WGIG) was formed to come up with ideas for future progress (UN n.d.). Two years later, WSIS reached agreement on the Tunis Agenda (Citation2005), and in particular the creation of the Internet Governance Forum (IGF), Citation2021.

Even in this highly simplified outline of how internet governance is structured and shared across different stakeholders, it is not difficult to imagine numerous of points of friction emerging. The most basic one stems from the definitional arguments surrounding what ‘internet governance’ even means – whether it focuses solely on the infrastructural and technical layers of the technology or whether it also includes what actors can do with the internet. The latter is very much the assumption with which the authors align themselves. Beyond that, the speed of internet adoption across the globe, the integration of technology in increasingly varied aspects of our lives and economies, and the constantly evolving nature of the internet itself all would suggest that any governance effort is no simple task. Despite these challenges, however, the multi-stakeholder model for internet governance has proven largely successful in building and sustaining a resilient and effective global public internet.

However, there is at least one critical area where the multi-stakeholder model has not been embraced – the issue of international peace and security in cyberspace. Instead, leading dialogs on the issue, at the United Nations (UN), Citationn.d. and elsewhere, have largely remained exclusive to states, in line with an interpretation of internet governance that focuses on technical layers. Here, states have looked to their historical sovereign responsibilities for peace and security in the kinetic world as a model, rather than examples from other areas of internet governance. That approach, as we explore below, seems ill-suited to promoting stability and security in cyberspace. Moreover, there are also many good examples of multi-stakeholder inclusion in UN dialogs on issues of peace and security in different domains – several of which are cataloged in a recent report from a working group of the Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace, a global multi-stakeholder initiative described further in Section 3 (Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace, Citation2021b).

2. Methods

In addition to a desk review of relevant materials, the authors benefitted from insights based on their active engagement in international discussions on peace and security in cyberspace over decades and direct involvement in several of the multi-stakeholder initiatives described in the article that have been established in recent years. Moreover, much of the technical data and insights stem from the authors’ work with Microsoft, a leading global technology firm. This affiliation of course comes with limitations and the authors recognize that their experience is not necessarily indicative of the private sector as a whole. However, as active participants in the multi-stakeholder community, these experiences nevertheless have value in developing recommendations for the future of multi-stakeholder diplomacy.

3. Discussion

3.1. Multilateral approach to a new domain of conflict

International security considerations related to cyberspace began to take shape in the 1990s. The potential of an increasingly connected world to augment the impact of what had been previously referred to as ‘information operations’ was becoming clear, at least to certain states. To address this emerging challenge, these discussions were brought to the UN, as the multilateral institution responsible for maintaining international peace and security. In 2004, the UN established, via resolution A/RES/58/32, the first Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on ‘Developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security’. The working group included representatives from 15 UN member states (Belarus, Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, Jordan, South Korea, Malaysia, Mali, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, the United Kingdom and the United States) with a mandate to deliberate ‘existing and potential threats in the sphere of information security and possible cooperative measures to address them … ’ (UN, Citation2003). Neither this first working group, nor the successive GGEs since, have provided space for the formal inclusion of non-governmental participants in the deliberations at any level. Instead, the only opportunities for multi-stakeholder voices to be heard have been outside the GGE deliberations, at the discretion of individual states when they choose to consult with non-state actors.

There have now been six iterations of this GGE model – each established by a separate resolution – and the format proved effective in achieving consensus on foundational expectations for responsible state behavior in the early years of cyber conflict. The consensus reports produced by the GGEs in 2010, 2013 and 2015 combined – referred to by some as the ‘Framework for Responsible State Behavior in Cyberspace’ (AUS-DFAT, Citation2019) – set an important precedent by recognizing the application of international law to state behavior online, as well as 11 voluntary, non-binding norms for responsible state behavior in cyberspace (UN, Citation2015). However, progress in GGE negotiations has been limited since 2015. The subsequent GGE convening in 2017 did not manage to produce a consensus report and while the most recent iteration of the GGE was able to provide additional guidance on how states might interpret and uphold international expectations in cyberspace, it was unable to agree upon any new commitments (UN, Citation2021).

However, recently a parallel working group has emerged at the UN as well. The first Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) on information security ran from 2019-2021, with a nearly identical mandate to the GGE – though in addition to addressing norms, rules and principles, capacity building and confidence building measures, and international law in cyberspace, the OEWG was asked to consider existing and potential threats, establishing a regular institutional dialogue on cybersecurity within the UN, and relevant international concepts for securing global IT systems (DiploFoundation, Citation2021). The OEWG is also already now confirmed for second round of deliberations that will run through 2025. Apart from the slight distinction in mandates, the major difference between the GGE and OEWG was that the OEWG was open to participation from all UN member states (UN, Citation2018). Moreover, the OEWG also included some degree of multi-stakeholder participation. In particular, it hosted one official in-person consultation with representatives of the multi-stakeholder community at the UN Headquarters in New York, in December 2019, during an informal intersessional meeting (UN, Citation2019). However, while the OEWG set an important precedent as it relates to inclusion, the final report from March 2021 failed to set any new expectations for state behavior online and, instead, restated existing expectations with some additional guidance on how states might implement them.

Another proposal currently being discussed at the UN is the Program of Action (PoA) on cybersecurity, a French-led initiative with over 50 government supporters (France, Citation2020). While not yet officially introduced for a vote, this initiative would seek to establish a permanent structure for dealing with cybersecurity within the UN First Committee, departing from the current ad hoc frameworks employed by the GGE and OEWG models. Moreover, the PoA would create an opportunity to place multi-stakeholder engagement at the center of its operational model, recognizing the need for civil society, academia and industry participation in efforts to secure cyberspace. While there is still much to be determined before the PoA can become a reality, it is certainly the most innovative proposal being discussed by member states at the moment and would seem to address the shortcomings of the traditional ad hoc and exclusive processes for addressing international cybersecurity at the UN.

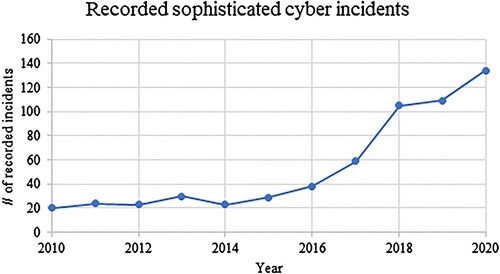

The fact that the global community was able to come together twice in 2021 in consensus reports from the OEWG and GGE, despite geopolitical tensions, is an achievement in itself, however, the slow progress in setting and enforcing expectations online remains alarming in light of the precipitous escalation of sophisticated attacks in cyberspace. This lack of progress reflects a growing perception that cyberspace is a domain of conflict and competition by governments with competing visions for internet governance and how international law applies to cyberspace. With that in mind, it is important to understand that, despite being the most recently recognized domain of conflict, cyberspace has already become perhaps the most active. The recent Microsoft Digital Defense Report Citation2020, based on threat intelligence from Microsoft security teams, highlights the expanded breadth and depth of state activity online over the past year, including the exploitation of the COVID-19 crisis in attacks, as well as the targeting of political campaigns and the Olympic Games. Meanwhile, data maintained by the Center for Strategic and International Studies on recorded sophisticated cyber incidents (shown on the graph below) gives some indication of just how rapidly the numbers of these attacks have grown over the past decade.

Figure 1. Based on data from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (Citation2021).

This raises an important question – whether the current model of ad hoc and term-limited UN working groups is best suited to advancing international expectations in a fast-moving and constantly evolving domain of conflict that requires cooperation across not just states, but multiple stakeholder groups. Recent events have only served to further place the inadequacy of current approaches in stark relief. 2021 began with continuing revelations about the scope and scale of the SolarWinds hack that targeted the ICT supply chain by corrupting a software update process (Temple-Raston, Citation2021); a cybercriminal group operating with impunity dismantled the operations of one of the United States’ largest gas pipelines (Jasper, Citation2021); food supplies were impacted when meat production was severely damaged by a ransomware attack (BBC, Citation2021); and a state-sponsored cyberattack targeted humanitarian aid agencies and organizations in an advanced phishing campaign (Burt, Citation2021). However, it also still remains unclear whether any of these would transgress the expectations established in the UN dialogs.

The expectations set and reinforced in both the GGE and OEWG bodies apply to state behavior online and, in some instances, the attacks cited above were committed by independent criminal groups. Whether – and to what degree – states have an obligation of due diligence to prevent such attackers from operating within their borders has not been adequately resolved. Meanwhile, some of the attacks that were state-sponsored, such as the SolarWinds hack, appear to have been focused on espionage, which has traditionally been tolerated by the international community, though in this case the ICT software supply chain was also compromised which harmed many more in the process. To some extent, especially as it relates to the interpretation of international law, this could be helped by states citing in their attribution statements specifically how international expectations have been violated by an attack. In other instances though, the expectations themselves are ambiguous and need to be clearer, or a new expectation is needed altogether – for example, if the norm recognized by the UN calls on governments to ‘ensure the integrity’ of the ICT supply chain, does this forbid attacks which target the ICT supply chain or simply require that states do more defensively? The answers to these and other questions remain ambiguous but are an important part of establishing a rules-based order online.

3.2. A need for multi-stakeholder inclusion

As with every other element of internet governance, international cybersecurity can benefit from multi-stakeholder cooperation. Many now take for granted that the majority of what we consider ‘cyberspace’ is owned, operated and maintained by the private sector (Klimburg & Faesen, Citation2018), often without any physical presence in countries where the companies operate. Meanwhile, the weapons, the battlefield and the victims of state-sponsored cyberattacks (whether intended or not) are frequently private organizations that, as a result, wind up with access to valuable information about how attacks were conducted and/or mitigated. This makes it hard to imagine how effective rules for responsible behavior online could be developed and upheld without the input and participation of the technology industry. While private organizations have always owned and operated the industry and resources that exist in physical domains of conflict where states have set rules, in cyberspace, this dynamic is different as private entities are largely responsible for the very fabric of the domain itself. While private organizations might own ships that operate on the high seas, they do not create the water. And beyond private industry, as cyberspace increasingly becomes a domain of human activity, as well as a domain of conflict, decisions made in the interests of security have implications for human rights and free expression, as well as for the safety of the most vulnerable, requiring the inclusion of civil society organizations that act in defense of these priorities.

While ultimate decision-making regarding peace and security in any domain will always be the exclusive responsibility of states, addressing conflict in cyberspace will require cooperation with non-governmental actors in a new form of multi-stakeholder diplomacy. This refers to the structured and consistent inclusion of non-governmental actors in deliberations about international rules and expectations. While non-governmental actors may not have decision-making authority, their deliberate inclusion in the dialogue is essential to ensure necessary perspectives are reflected and that there is cooperation in upholding international expectations moving forward. While pursuing this kind of multi-stakeholder diplomacy creates responsibilities for states to create the space to facilitate such inclusion, it also requires that non-governmental entities equip themselves to contribute to, and participate in, forums that had previously been exclusive to states.

3.3. The rise of multi-stakeholder approaches to peace and security online

2017 was perhaps the most consequential year (thus far) in the relatively short history of sophisticated cyberattacks and conflict online. If previous concerns surrounding the escalating frequency and severity of cyberattacks had been largely limited to IT communities, following the successive far-reaching and high-profile cyber incidents in 2017 – including the WannaCry and NotPetya attacks – the issue quickly garnered widespread attention. Over a few short months in 2017, shipping giants had their systems taken offline (Greenberg, Citation2018), hospitals went dark (Palmer, Citation2021), and the Social Security information of nearly half of all Americans was stolen (FTC, Citation2019).

These attacks showed that more must be done by all stakeholders to uphold expectations for responsible behavior online. Microsoft President Brad Smith made this clear in his remarks at the RSA Conference in San Francisco that same year: ‘I think nation-state attacks call on us, as employes, as an industry, as private citizens, to ask ourselves one fundamental question, ‘what are we going to do?’ (Smith, Citation2017). 2017 was also the year that the GGE on information security failed to reach a consensus report at the end of its deliberations at the UN, underscoring how intractable the issue had become in traditional diplomatic spaces.

Against this backdrop, several new approaches began to emerge the following year, outside the auspices of the UN, and have continued to develop since – initiatives which have allowed non-governmental stakeholders to play a leading role in promoting security and responsible behavior across the digital ecosystem. These efforts include two industry-led initiatives, the Charter of Trust (Citation2021a) and the Cybersecurity Tech Accord (Citation2021a), as well as multi-stakeholder commitments in the Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace (Citation2021a) and the Contract for the Web (Citation2020), and a consultative series open to all stakeholders, Let’s Talk Cyber (Citation2020). Pulling together different coalitions of stakeholders, each of these efforts has been aimed at promoting a safer and more secure online world by leveraging a diversity of valuable expertise.

3.3.1. The Charter of Trust

First launched at the Munich Security Conference in February of 2018, the Charter of Trust is an industry compact spearheaded by Siemens which focuses on addressing escalating risk associated with increased connectivity (Charter of Trust, Citation2021a). The group includes 17 partner companies, as well as an extended group of partners from other stakeholder groups. It is committed to three main objectives: (i) to protect the data of individuals and companies, (ii) to prevent damage to people, companies and infrastructures, and (iii) to create a reliable foundation on which confidence in a networked, digital world can take root and grow (Charter of Trust, Citation2021a). Its efforts are organized around 10 principles based on these objectives and have focused on scaling supply chain security, promoting security by default and cybersecurity education, as well as harmonizing standards and regulations (Charter of Trust, Citation2021a). It has particularly focused on aligning the members around supply chain security principles and information sharing.

3.3.2. The Cybersecurity Tech Accord

The Cybersecurity Tech Accord arose from an effort within the technology industry to take greater responsibility and to speak with one voice on issues of peace and security online. Launched in April 2018 with 34 signatory companies, the coalition is open to private technology firms that maintain its commitments and today boasts over 150 signatories from around the world – including household names like Facebook, Cisco, Microsoft and Oracle, as well as many smaller companies – making it the largest such industry commitment to cybersecurity principles. The Cybersecurity Tech Accord also reflects the breadth and diversity of the technology industry itself, with signatories that include software developers, hardware manufacturers, social media platforms, cloud service providers and many more, all committed to four foundational cybersecurity principles for the entire technology industry – better defense, no offense, capacity building, and collective action (Cybersecurity Tech Accord, Citationn.d.).

Beyond simply a statement of principles, the Cybersecurity Tech Accord is an active body which draws upon the expertise of its signatory base to improve security across the digital ecosystem via initiatives aligned with its four principles. It has provided input and guidance to government organizations and intergovernmental bodies, including the OECD (Cybersecurity Tech Accord, Citation2020a), the US Cyberspace Solarium Commission (Citation2020), and the UN OEWG on information security (Cybersecurity Tech Accord, Citation2021b), among others. It has also been a prominent supporter of the Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace, producing multiple White Papers supporting the implementation of Paris Call principles on hack back (Cybersecurity Tech Accord, Citation2020b) and advancing cyber hygiene (Cybersecurity Tech Accord, Citation2020c), as well as on other topics to help guide global capacity building and policymaking efforts. The group has also invested in ensuring that its signatories are committed to specific cybersecurity good practices, for example ensuring they have a coordinated vulnerability disclosure policy in place.

3.3.3. The Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace

The Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace (Paris Call) is an international commitment to cybersecurity principles initiated by the French government in November 2018, emphasizing the need to prevent conflict in the digital domain (Rose, Citation2018). The nine principles of the agreement largely reflect commitments made in other multilateral forums, including the norms first recognized by the GGE in 2015. However, what sets the Paris Call apart is its multi-stakeholder structure. Today, with over 1200 supporting entities from around the world, including 80 national governments, as well as many of the world’s largest companies and most prominent civil society organizations (it is a leading forum for multi-stakeholder cooperation on peace and security in cyberspace Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace, Citation2021d). In 2021, the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs launched six working groups to support the vision of the agreement and facilitate cooperation among its supporters, and the resulting work products reflect a unique and robust collaboration between government, industry and civil society groups, as well as academics (Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace, Citation2021b; Global Commission on Stability of Cyberspace, Citation2019; Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace, Citation2021c).

In 2020, the communities of supporters for the Paris Call pursued independent initiatives to demonstrate the implementation and to uphold the principles of the agreement; this included industry, civil society and multiple governments. This included the work of the Cybersecurity Tech Accord in support of principles on cyber hygiene and hack back referenced above, as well as the collaborative efforts of other supporters (Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace, Citation2021e). The authors of this report co-championed the Paris Call Community on Countering Election Interference (Paris Call Principle #3), alongside the Government of Canada and the Alliance for Securing Democracy. Throughout 2020, these co-champions brought the global community together in multi-stakeholder workshops addressing priority topics related to interference in electoral processes. These consultations resulted in the publication of a compendium of good practices for election management bodies, governments and other stakeholders to support their efforts to safeguard elections and democracy (Government of Canada, Citation2021). The initiative reflected the potential of a community to convene the necessary experts and cooperate to produce a valuable new resource under the umbrella of the Paris Call.

3.3.4. Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace

The Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace (GCSC) was a multi-stakeholder group committed to the formation of diplomatic norms concentrated on governmental offensive action in cyberspace. The group operated from 2017 to 2019. It was co-chaired by Michael Chertoff and Latha Reddy and comprised 26 prominent commissioners in total, bringing together stakeholders across the different sectors, and from around the world. The Commission produced eight norms for responsible state behavior (Global Commission on Stability of Cyberspace, Citation2019), which have since been taken up in various other forums.

3.3.5. Contract for the Web

Launched by the World Wide Web Foundation, Citation2021 in November 2019, the Contract for the Web is, similar to the Paris Call, a multi-stakeholder initiative meant to promote a better online world. However, the Contract for the Web is less focused on cyber conflict specifically and more on promoting a public internet that is accessible, secure and rights-respecting. It is designed around distinct responsibilities across three stakeholder groups – governments, companies and citizens.

3.3.6. Let’s Talk Cyber

Following the official OEWG multi-stakeholder consultation in 2019, there were hopes that this would be the beginning of more dynamic and robust inclusion of multi-stakeholder voices in cybersecurity dialogs at the UN. When that did not occur, a coalition of partners, including the Governments of Canada and Australia, Global Partners Digital, European Union Institute for Security Studies, Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, Research ICT Africa, and Microsoft, organized an informal multi-stakeholder dialogue called ‘Let’s Talk Cyber’ to give input to the OEWG discussions (EU Institute for Security Studies, Citation2021). The Let’s Talk Cyber series hosted two convenings to support the OEWG’s work, in December 2020 and February 2021, which enabled exchange between governments, industry and civil society participants and effectively tripled the number of multi-stakeholder consultations included in the OEWG’s deliberations. The Let's Talk Cyber consultations brought together more than 1000 participants, across all stakeholder groups. The value of these consultations was highlighted in the OEWG’s final report (United Nations General Assembly, Citation2021).

4. Recommendations: the future of multi-stakeholder diplomacy for peace and security online

All of the multi-stakeholder initiatives above constitute ongoing collaborations that will continue to mature in the coming years to promote security and to discourage reckless behavior. In March 2021, the French government announced the creation of six working groups under the auspices of the Paris Call, each chaired by organizations with relevant expertise and open to participation from the broad base of supporters from across stakeholder groups (Coker, Citation2021). The Cybersecurity Tech Accord has been co-chairing the Paris Call working group for the promotion of a multi-stakeholder approach to cybersecurity dialogs at the UN (French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, Citation2021). Meanwhile, the Charter of Trust is promoting its baseline requirements for supply chain security (Charter of Trust, Citation2021b) and the Contract for the Web is planning the development of a web presence to evaluate how its supporters are living up to their commitments (Contract for the Web, Citation2020).

These efforts can create innovative paths forward to help implement existing agreements and identify gaps that emerge in the current framework, but also help to hold malicious actors accountable, even when it is not politically expedient. They will also likely play important roles in cybersecurity capacity building, for government, civil society and industry – ensuring that stakeholders from around the world can participate in these discussions on an equal footing. Many of the initiatives mentioned thus far have included capacity-building elements, but there are also efforts that focus on that space alone, for example the Global Forum on Cyber Expertise, Citationn.d..

This is important as clear gaps exist between the international expectations that have been agreed upon, and state practice which continues to violate expectations by, inter alia, undermining the integrity of the ICT supply chain, targeting critical infrastructure, and not preventing wrongful acts originating in one’s own territory. Implementing these and other expectations for responsible behavior will require a combination of further elaboration/development of existing expectations, capacity building, and accountability efforts that hold bad actors responsible for their actions – this will need cooperation across stakeholder groups. To accomplish this, multi-stakeholder initiatives and coalitions, like the ones introduced here, will need to be incorporated into formal international processes.

The multi-stakeholder community has an important part to play in advancing accountability to support international cybersecurity. When considering the role of the technology industry alone, it already does – and must continue to do more to – support and inform international capacity building efforts to ensure states can implement international commitments to improve cyber resilience and defenses, thereby deterring bad actors by raising the stakes for successful attacks. Moreover, the private sector is also already playing an increasingly important role in providing technical attributions for cyberattacks. But in addition to supporting the implementation of expectations, the multi-stakeholder community also has a valuable part to play in providing guidance when setting expectations as well.

Considering the 11 UN norms for responsible state behavior in cyberspace as an example of an agreement reached among states exclusively, while the norms themselves provide a valuable baseline of expectations it is nonetheless remarkable how derivative they are of expectations for other domains of conflict. Things like security cooperation; caution in attributing wrongful acts; not knowingly allowing territory to be used for wrongful acts; cooperation in combatting criminals and terrorists; respect for human rights; not supporting activity contrary to international law; protecting critical infrastructure; responding to requests for assistance; protecting supply chains; and not targeting first responders are all norms that could be reasonably applied to any domain of conflict as readily as they could be to cyberspace. In fact, the only UN norm that would seem unique to cyberspace is 13(J) on the reporting of ICT vulnerabilities. This is not to say that these are not all the relevant norms for cyberspace, but there are likely others that would be included if voices with deeper and different expertise on cybersecurity participated in the deliberations. This was certainly the case in the efforts of the multi-stakeholder GCSC, which recognized the need for additional international norms to protect the public core of the internet and to address botnets – more clearly technical elements that reflect the unique nature of cyberspace and what it requires to be secured (Global Commission on Stability of Cyberspace, Citation2019). These kinds of expectations can help further advance security but identifying them requires perspectives that governments do not generally possess endogenously.

With the recent conclusions of the both the latest GGE and OEWG dialogs reaffirming international expectations, there is opportunity for the UN in particular to reconsider how best to structure its approach to this domain of conflict moving forward and to focus on accountability and enforcement. As with other areas of internet governance, a multi-stakeholder community will need to be heavily engaged in this work alongside governments, and the different initiatives described here indicate both a willingness, and now a capacity, for non-governmental stakeholders to participate. The UN has recently begun a new round of OEWG negotiations which, unfortunately, do not make provisions for greater multi-stakeholder inclusion by design. Multi-stakeholder inclusion should be built into the framework for any future cybersecurity dialogs at the UN, with minimum standards set for both written and in-person consultative sessions with non-governmental stakeholders (Ciglic, Citation2021).

In addition, dialogue on international cybersecurity at the UN should take place within a standing body. In comparison to physical domains, cyberspace is constantly evolving alongside technological innovations and applications, and so too are the threats. The only certain thing is that this is an issue area that will persist into the foreseeable future as the world continues through this period of rapid digital transformation (Ciglic, Citation2021). As a result, term-limited, ad hoc working group dialogs, established by successive UN resolutions, are poorly designed to respond to this issue space. Instead, the UN should pursue a standing body that will be able to facilitate ongoing dialogue and cooperation. The proposal by the French government for a Program of Action (PoA) at the UN provides perhaps the greatest hope for a standing deliberative body that could address the issue space on an ongoing basis while facilitating multi-stakeholder inclusion.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kaja Ciglic

Kaja Ciglic As part of the Digital Diplomacy team at Microsoft, Kaja leads Microsoft’s work on issues related to international peace and stability to advance trust in the computing ecosystem. Previously, she led Microsoft’s international cybersecurity policy work in an effort to develop policies that support development, growth, and innovation, and advance security, privacy, and trust in the information age.

Before joining Microsoft, Kaja led the APCO Worldwide’s technology practice in Seattle; directing public affairs and communication work for consultancy’s clients in this space. Previous to that she worked as a director in APCO Worldwide’s Brussels office, focusing on pan-European campaigns, addressing her clients’ regulatory and antitrust challenges. She holds a Bachelor of Science in international relations and history, and a Master of Science in European politics, both from the London School of Economics.

John Hering

John Hering is a Senior Government Affairs Manager for the Digital Diplomacy team at Microsoft. He analyzes the global cybersecurity landscape, drives engagement with regional government teams and contributes to Microsoft’s efforts to promote peace and security in cyberspace through various multi-stakeholder initiatives. He leverages experiences working in and across the U.S. Government to support Microsoft teams as well as policymakers to improve cybersecurity strategies and policies. Prior to joining Microsoft, John served as a White House Defense Fellow in the Obama administration at the Department of Defense, in the Office of the Secretary of Defense for Policy. He has also previously led humanitarian aid research in northeast Nigeria with the Danish Refugee Council and worked as a math and science teacher through Teach For America. John holds a bachelor’s degree in Political Science from Boston College and a Master of Arts in Law and Diplomacy from The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy.

Bibliography

- AUS-DFAT (Australia Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade). 2019. Public Consultation – Responsible State Behaviour in Cyberspace in the Context of International Security at the United Nations. https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/public-consultation-responsible-state-behaviour-in-cyberspace-in-the-context-of-international-security-at-the-united-nations.pdf.

- BBC. 2021. “Meat giant JBS pays $11m in ransom to resolve cyber-attack.” BBC, June 10. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-57423008.

- Burt, Tom. 2021. “Another Nobelium Cyberattack.” Microsoft On the Issues. Microsoft, May 27. https://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2021/05/27/nobelium-cyberattack-nativezone-solarwinds/.

- Charter of Trust. 2021a. “Charter of Trust: About.” Charter of Trust. https://www.charteroftrust.com/about/

- Charter of Trust. 2021b. “Webinar Invitation: Responsibility Throughout the Digital Supply Chain Beyond Existing Standards and Norms: Are we Doing Enough?” Charter of Trust. https://www.charteroftrust.com/news/charter-of-trust-p2-webinar-2021-06-02/

- Ciglic, Kaja. 2021. “The next chapter of cyber diplomacy at the United Nations beckons” Microsoft On the Issues. Microsoft, December 16. https://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2021/08/30/united-nations-gge-cybersecurity-diplomacy/.

- Coker, James. 2021. “Kaspersky to Co-Chair Working Group of the Paris Call.” Infosecurity Group Magazine. https://www.infosecurity-magazine.com/news/kaspersky-working-group-paris-call/.

- Contract for the Web. 2020. “What’s next for the Contract for the Web?” Contract for the Web, November 10. https://contractfortheweb.org/2020/11/10/whats-next-for-the-contract-for-the-web/.

- CSIS (Centre for Strategic and International Studies). 2021. “Significant Cyber Incidents.” Centre for Strategic and International Studies. Accessed 17 June 2021. https://www.csis.org/programs/strategic-technologies-program/significant-cyber-incidents.

- Cybersecurity Tech Accord. 2020a. “Cybersecurity Tech Accord comments on OECD work on Digital Security.” Cybersecurity Tech Accord, June 29. https://cybertechaccord.org/cybersecurity-tech-accord-comments-on-oecd-work-on-digital-security/.

- Cybersecurity Tech Accord. 2020b. No Hacking Back: Vigilante Justice vs. Good Security Online. https://cybertechaccord.org/uploads/prod/2020/11/hack-back-update-131120-pages.pdf.

- Cybersecurity Tech Accord. 2020c. The Compendium on Cyber Hygiene. https://cybertechaccord.org/uploads/prod/2020/11/Cyber-Hygiene-Appendium-update-191120-pages.pdf.

- Cybersecurity Tech Accord. 2021a. “Cybersecurity Tech Accord Celebrates over 150 Signatories.” Cybersecurity Tech Accord, April 7. https://cybertechaccord.org/cybersecurity-tech-accord-celebrates-over-150-signatories/.

- Cybersecurity Tech Accord. 2021b. “Cybersecurity Tech Accord response to OEWG’s draft final report.” Cybersecurity Tech Accord, March 10. https://cybertechaccord.org/cybersecurity-tech-accord-response-to-the-un-oewgs-substantive-report-first-draft/.

- Cybersecurity Tech Accord. n.d. “About the Cybersecurity Tech Accord.” Accessed: November 18, 2021. https://cybertechaccord.org/about/.

- DiploFoundation. 2021. “UN GGE and OEWG.” Geneva Internet Platform’s Digital Watch. https://dig.watch/processes/un-gge

- EU Institute for Security Studies. 2021. “Informal Multi-stakeholder Cyber Dialogue 2020–2021.” https://letstalkcyber.org/.

- France, Egypt, Argentina, Colombia, Ecuador, Gabon, Georgia, Japan, Morocco, Norway, Salvador, Singapore, the Republic of Korea, the Republic of Moldova, The Republic of North Macedonia, the United Kingdom, the EU and its member States (Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Republic of Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden). 2020. “The future of discussions on ICTs and cyberspace at the UN.” https://front.un-arm.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/joint-contribution-poa-future-of-cyber-discussions-at-un-10-08-2020.pdf.

- French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs. 2021. “Cybersecurity: Paris Call of 12 November 2018 for Trust and Security in Cyberspace.” Diplomatie.gouv.fr. https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/french-foreign-policy/digital-diplomacy/france-and-cyber-security/article/cybersecurity-paris-call-of-12-november-2018-for-trust-and-security-in.

- FTC (Federal Trade Commission). 2019. “Equifax to Pay $575 Million as Part of Settlement with FTC, CFPB, and States Related to 2017 Data Breach.” Federal trade Commission, July 22. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2019/07/equifax-pay-575-million-part-settlement-ftc-cfpb-states-related.

- Global Commission on Stability of Cyberspace. 2019. Advancing Cyberstability: Final Report. The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies and EastWest Institute. GCSC-Advancing-Cyberstability.pdf.

- Global Forum on Cyber Expertise. n.d. thegfce.org Accessed November 18, 2021. https://thegfce.org/.

- Government of Canada. 2021. Multi-stakeholder Insights: A Compendium on Countering Election Interference. Mult-Stakeholder insights: A compendium on countering election interference - Democratic Institutions - Canada.ca - Canada.ca.

- Greenberg, Andy. 2018. “The Untold Story of NotPetya, the Most Devastating Cyberattack in History.” Wired, August 22. https://www.wired.com/story/notpetya-cyberattack-ukraine-russia-code-crashed-the-world.

- IGF (Internet Governance Forum). 2021. Internet Governance Forum. https://www.intgovforum.org/multilingual/.

- Internet Governance Project. 2018. “What Is Internet Governance?” School of Public Policy at Georgia Institute of Technology. https://www.internetgovernance.org/what-is-internet-governance/.

- ITU (International Telecommunication Union). 2003. “Declaration of Principles: Building the Information Society: a global challenge in the new Millennium.” World Summit on the Information Society, December 12. https://www.itu.int/net/wsis/docs/geneva/official/dop.html.

- ITU (International Telecommunication Union). 2005. “Tunis Agenda for the Information Society.” World Summit on the Information Society, November 18. https://www.itu.int/net/wsis/docs2/tunis/off/6rev1.html.

- ITU (International Telecommunication Union). 2009. “World Summit on the Information Society, First Phase: 10-12 December 2003.” World Summit on the Information Society. https://www.itu.int/net/wsis/geneva/index.html.

- Jasper, Scott. 2021. “Assessing Russia’s role and responsibility in the Colonial Pipeline attack. Atlantic Council, June 1. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/assessing-russias-role-and-responsibility-in-the-colonial-pipeline-attack.

- Klimburg, Alexander, and Louk Faesen. 2018. “A Balance of Power in Cyberspace.” (Rep.). Hague Centre for Strategic Studies Paper Series 14. Accessed June 17, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep19350.

- Leiner, Barry M., Vinton G. Cerf, David D. Clark, Robert E. Kahn, Leonard Kleinrock, Daniel C. Lynch, Jon Postel, Larry G. Roberts, and Stephen Wolff. 1997. “Brief History of the Internet.” Reston: Internet Society.

- Microsoft. 2020. Microsoft Digital Defense Report October 2021. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/download/details.aspx?id=101738.

- Palmer, Danny. 2021. “Ransomware: How the NHS learned the lessons of WannaCry to protect hospitals from attack.” ZDNet, May 13. https://www.zdnet.com/article/ransomware-how-the-nhs-learned-the-lessons-of-wannacry-to-protect-hospitals-from-attack/.

- Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace. 2021a. Advancing International Cyber Norms: Multi-stakeholder Recommendations. https://pariscall.international/assets/files/WG4-Final-Report-101121.pdf.

- Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace. 2021b. Multi-stakeholder participation at the UN: The need for greater inclusivity in the UN dialogues on cybersecurity. https://pariscall.international/assets/files/10-11-WG3-Multi-stakeholder-participation-at-the-UN-The-need-for-greater-inclusivity-in-the-UN-dialogues-on-cybersecurity.pdf.

- Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace. 2021c. Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace Working Group 5: Building a Cyberstability Index Executive Summary and Final Report. https://pariscall.international/assets/files/PWGR5-8-11-21.pdf.

- Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace. 2021d. “Supporters — Paris Call.” Paris Call. https://pariscall.international/en/supporters.

- Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace. 2021e. “The 9 Principles — Paris Call.” Paris Call. https://pariscall.international/en/principles.

- Rose, Michel. 2018. “Macron and tech giants launch 'Paris call' to fix internet ills.” Reuters, November 12. Accessed 17 June 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-cyber-un-macron-idUSKCN1NH0FS.

- Smith, Brad. 2017. “Brad Smith RSA Keynote, 2017.” [Live Address] RSA Conference. YouTube, March 1. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C-YvpuJO6pQ.

- Talk Cyber. 2020. https://letstalkcyber.org/.

- Temple-Raston, Dina. 2021. “A 'Worst Nightmare' Cyberattack: The Untold Story Of The SolarWinds Hack.” NPR, April 16. https://www.npr.org/2021/04/16/985439655/a-worst-nightmare-cyberattack-the-untold-story-of-the-solarwinds-hack.

- UN (United Nations). 2003. A/RES/58/32 – Developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security. https://undocs.org/A/RES/58/32.

- UN (United Nations). 2015. A/70/174 – Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security. https://undocs.org/A/70/174.

- UN (United Nations). 2018. A/RES/73/27 - Developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security. https://undocs.org/A/RES/73/27.

- UN (United Nations). 2019. “Informal intersessional consultative meeting of the OEWG with industry, non-governmental organizations and academia (2-4 December 2019).” United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. https://www.un.org/disarmament/oewg-informal-multi-stakeholder-meeting-2-4-december-2019/.

- UN (United Nations). 2021. Report of the Group of Governmental Experts on Advancing Responsible State Behaviour in Cyberspace in the Context of International Security. https://front.un-arm.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/final-report-2019-2021-gge-1-advance-copy.pdf.

- UN (United Nations). n.d. “World Summit on Information Society (WSIS).” United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: Public Institutions. Accessed November 18, 2021. https://publicadministration.un.org/en/Themes/ICT-for-Development/World-Summit-on-Information-Society.

- United Nations General Assembly. 2021. A/AC.290/2021/CRP.2 – Open-Ended Working Group on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security: Final Substantive Report. https://front.un-arm.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Final-report-A-AC.290-2021-CRP.2.pdf.

- United States of America Cyberspace Solarium Commission. 2020. Cyberspace Solarium Commission Report. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ryMCIL_dZ30QyjFqFkkf10MxIXJGT4yv/view.

- World Wide Web Foundation. 2021. “Contract for the Web: A global plan of action to make our online world safe and empowering for everyone.” Contract for the Web. https://contractfortheweb.org/.