ABSTRACT

This article analyses how humanitarian and development Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) have responded to the alteration of public funding opportunities over a long time period. Analysing a long time period allows for a better understanding of the potential impact of external shocks, such as the European sovereign and debt crisis. Data show that many CSOs severely affected by budget cuts at the national level in the context of the euro crisis have adopted a compensation strategy consisting on turning more frequently to international and European funds. Thus, in some countries, the economic crisis has contributed to the Europeanization of CSOs. This in-depth comparative qualitative analysis is based on the study of national humanitarian and development CSOs based in France and Spain.

1. Introduction

How do external shocks, such as the Euro crisis, alter the structural conditions in which Humanitarian and Development Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) operate in Europe? The answer to this question calls for an in-depth analysis of the evolution of CSOs Europeanization strategies over a long time period. When Europeanization strategies are analysed over a long time period, events such as the economic and debt crisis offer a unique opportunity to analyse the changing role of public donors and the evolution of CSOs under the stress of serious external shocks. In this area of research, studies on multi-level governance (MLG) substantially overlap with literature on Europeanization (Stephenson, Citation2013). The study of CSOs strategies in a multi-level system includes indeed the analysis of Europeanization strategies, which are the ones that have attracted most scholarly attention (Beyers, Citation2002; Beyers & Kerremans, Citation2012; Callanan, Citation2011).

The main goal of this article is to investigate how CSOs strategies evolve over a long time period in a multi-level system, showing how they are (or not) affected by serious external shocks. An external shock can plausibly affect the Europeanization strategies of CSOs through the alteration of political opportunities offered by different levels of governance. The economic crisis may have created a new situation in which Europeanization strategies become more likely. If the economic crisis cuts down political opportunities at the national level, CSOs could decide to turn to the European level. The adoption of Europeanization strategies by CSOs could also be less likely in the new circumstances. In times of crisis, CSOs may become more vulnerable and thus, they may lack the organizational capacity required to engage in venue shopping across levels of governance.

Since this article cannot analyse all existing political opportunities at different levels, the emphasis is placed on public funding and the evolution of CSOs grant-seeking strategies. This focus is a valuable addition to literature on European studies on this area, which focuses on opportunities to access the policy-making process (Beyers, Citation2002; Beyers & Kerremans, Citation2012; Callanan, Citation2011). The importance of public funding for interest groups in Europe has been highlighted by many authors (Greenwood, Citation2007; Mahoney & Beckstrand, Citation2011; Mahoney, Citation2004; Sanchez Salgado Citation2014a) but detailed empirical analysis on this topic remain rare.

The study of the evolution of funding opportunities in times of crisis is of utmost importance for major debates on the relationships between governments and the voluntary sector. Public funding of CSOs is often regarded with suspicion, since it could endanger CSOs autonomy and inhibit their political activities (Mosley, Citation2012). On the other hand, previous research shows that public funding does not necessarily suppress CSOs political activities (Chaves, Stephens, & Galaskiewicz, Citation2004). Strong and balanced ties with government can contribute to active involvement in the policy process (Khaldoun, Citation2014; Steen, Citation1996). The associative democracy perspective even considers that public funds are essential to promote healthy characteristics among CSOs and to avoid imbalances in the system of interest representation (Cohen & Rogers, Citation1992; Sanchez Salgado, Citation2014b). The fragmentation of funds allows CSOs to tap into a diversified set of legitimacy and funding sources and thus, it helps avoiding dependence on one single donor (Molenaers, Jacobs, & Dellepiane, Citation2014). If EU-based CSOs can engage in venue shopping over long time periods -including in times of crisis- this would support the argument that a multi-level system (offering public funds at multiple levels) can enhance the autonomy of CSOs.

This article’s focus on complex funding opportunities and multi-level grant-seeking strategies over a long time period calls for an in-depth qualitative comparative analysis across policy areas and EU member states. EU impact is addressed through the analysis of CSOs based on two EU member states: France and Spain. While both countries share a certain number of characteristics, they vary in the key variables for this analysis: they have dissimilar funding opportunities for CSOs and they have been affected by the economic crisis in very different ways. This article studies humanitarian and development CSOs, two related policy sectors that have been strongly affected by the crisis in Europe. According to CSO representatives, budget cuts in the development and humanitarian policy areas have been much more important than those in other areas since in a context of crisis, public authorities tend to focus on poverty reduction at home.Footnote1 EU aid has indeed significantly decreased in absolute terms in 2011 and 2012 since it went from 54.3 billion euro in 2010 to 49 billion euro in 2012 (CONCORD, Citation2014). The most drastic budget cuts during this period took place in Spain (49% between 2011 and 2012) that reached in 2012 its lowest levels of aid since 1989 (0.15 of GINI).

In a multi-level system, an economic crisis affects differently the evolution of national public funds and the response by CSOs, depending on a complex combination of factors. The cases under analysis show that the economic crisis lead to the Europeanization of CSOs under certain circumstances, in agreement with the assumptions of early MLG perspectives. In the wake of drastic budget cuts at the national level, many CSOs engaged in international and EU-level strategies. This article introduces first the most relevant academic discussions on MLG and an analytical framework designed to investigate the evolution of CSOs Europeanization strategies. In the empirical part, the article gives a detailed account of the most relevant factors in the countries under analysis. It explores to which extent European and national funding opportunities have been altered after the economic crisis and the evolution of CSOs’ grant-seeking strategies.

2. Analysing the evolution of humanitarian and development CSOs strategies

2.1. Accounting for the evolution of CSOs strategies in the EU multi-level system

European CSOs operate in a multi-level system, composed of different tiers of governance. The concept of MLG has been often used to refer to this pluralistic and highly dispersed political system, where multiple actors participate at various political levels, from the supranational to the local (Stephenson, Citation2013). In this setting, early MLG studies argued that domestic actors would develop strategies to circumvent the national level by engaging in supranational activity (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2001). When domestic actors engage in European strategies, MLG substantially overlaps with literature on Europeanization of non-state actors. While most Europeanization literature has so far focused on the top-down impact of the EU, much less attention has been given to horizontal and bottom-up Europeanization involving CSOs (Exadaktylos & Radaelli, Citation2009). A broad conceptual discussion on the concept of Europeanization is beyond the scope of the present article, since the attention is drawn to a specific dimension of the Europeanizaton process: the Europeanization strategies of non-state actors. Many studies on the Europeanization of interest groups and social movements focus on strategies across levels of governance (Beyers & Kerremans, Citation2007, Citation2012; Beyers, Citation2002; Imig & Tarrow, Citation1999; McCauley, Citation2011). While the emphasis has been placed on access opportunities, my analysis focuses on funding opportunities and the evolution of CSOs strategies over a relatively long time period. The use of EU funding opportunities in the areas where they are available is quite widespread (Sanchez Salgado, Citation2014a). An increase in CSOs multi-level grant-seeking strategies is relevant because they are not just a means to increase CSOs’ income. Even in situations where the autonomy and independence of CSOs is preserved, the use of public funding has relevant effects in the form of goal displacement, the diffusion of management techniques and the transnationalisation of CSO activities (Sanchez Salgado, Citation2010).

It is not so easy to shift from one level of governance to another. There are multiple factors facilitating or hindering Europeanization strategies. Political opportunities offered at different levels of governance are not the only relevant explanatory factor. Other factors frequently emphasised are the degree of national embeddedness, CSOs’ organizational capacity and resources, relational aspects, the degree of fit between modes of interest intermediation at different levels and the interrelatedness and complementarity among opportunities at different levels. Domestic embeddedness of national CSOs is related to their inclination to address venues situated at other levels and relational aspects seem to have a significant explanatory power (Beyers & Kerremans, Citation2012). Organizational capacity and resources tend to have a positive impact on the Europeanization of lobbying activities but they cannot fully explain engagement in multi-level strategies (Klüver, Citation2010). Language and international grant-seeking skills may contribute to CSOs inclination to apply for EU grants, which could be also interpreted as a goodness of fit between CSOs skills and EU requirements (Sanchez Salgado, Citation2014a). However, the goodness of fit argument does not seem to hold much explanatory power when applied broadly to countries (Beyers & Kerremans, Citation2012). National CSOs also tend to engage more frequently in advocacy when they are already in contact with public authorities for other reasons, such as grant-seeking (Sanchez Salgado, Citation2014a; Mosley, Citation2012).

To investigate the evolution of CSOs strategies over a long time period, I adapt Beyers’s (Citation2002) typology of Europeanization strategies to include a temporal dimension. Beyers proposed four hypotheses for analysing Europeanization strategies of interest groups, which have also been applied to the study of sub-national actors (Callanan, Citation2011). This analytical framework has been used so far to study access opportunities, but it can be adapted to the study of funding opportunities and grant-seeking strategies (). The positive persistence hypothesis assumes that CSOs that benefit from generous funding schemes at the domestic level tend to use more European funds, since their capacity carries over to the European level. In sharp contrast, the negative persistence hypothesis predicts that when domestic actors enjoy prolific domestic funds, they do not request European funding. In line with the by-passing assumption, the compensation hypothesis argues that domestic groups tend to compensate for the absence of domestic funds with European funds. The reverse positive persistence hypothesis expects that CSOs based in countries with little public funding lack the capacity to apply for EU funds. Chasing new funding streams is not an easy task and more importantly, it costs money. CSOs need skilled professionals, time and resources to put together high competitive applications. In this line, interest groups from Central and Eastern Europe are less likely to develop viable proposals (Mahoney & Beckstrand, Citation2011).

Table 1. Possible causal paths regarding CSOs grant-seeking strategies.

As shown by previous qualitative analysis, a complex combination of factors leads to the prevalence of each one of these hypotheses in different members states (Callanan, Citation2011, Sanchez Salgado, Citation2014a). It is expected that the strategies of CSOs evolve over a long time period, especially in cases of external shocks. Economic downturns are crucial events in which political opportunities, especially public funds, can be altered, and thus, one should expect changes in the strategies of CSOs. However, the alteration of public funds is only one relevant factor among the many others mentioned above. A complex combination of factors is expected to lead to a multiplicity of outcomes that evolve over time.

For example, one would expect that if drastic budget cuts intervene at the domestic level while European funding opportunities remain more or less stable, these domestic budget cuts will contribute to the adoption of compensation strategies by domestic CSOs (). However, the extent to which CSOs actually adopt compensation strategies also depends on other factors such as national embeddedness, economic resources and organizational capacity. When most factors are not favourable or if there are not significant budget cuts at the national level, CSOs will not be expected to adopt a compensation strategy.

2.2. Comparative case study and data: development and humanitarian CSOs in France and Spain

For the purpose of this article, CSOs include actors outside of the public sector, the informal sector and the market sector. Without seeking to form a government, CSOs pursue public policy goals. These include advocacy, lobbying and service delivery. Most CSOs studied are primarily service providers, but service provision is more often than not also accompanied by advocacy activities. CSOs are formally democratically accountable and involve some degree of voluntary participation. In order to address the main methodological challenges attributed to Europeanization studies, this context-sensitive in-depth study will apply one of the proposed solutions: a long-term comparison in different member states (Saurugger, Citation2005). The purpose of this in-depth comparison is to show how the relevant explanatory factors previously identified (political opportunities, national embeddedness, resources and organizational capacity) can be combined in different forms leading to different outcomes. Following an INUS approach to causation, this article aims at identifying causes that are jointly sufficient for an outcome (Mahoney & Goertz, Citation2006). The factors under analysis are thus considered as Insufficient and Non-redundant parts of Unnecessary but Sufficient causes (INUS).

2.2.1. A qualitative comparative case study across countries and policy areas

A comparative analysis across two countries permits to include in the analysis relevant factors such as national embeddedness and different political opportunities. This article focuses on two inter-connected policy fields: development and humanitarian aid. Humanitarian aid intervenes in crisis situations on the basis of principles such as urgency, non-discrimination and neutrality. Development aid is generally based on a bottom-up long-term cooperation with local populations, captured in the motto ‘from help to self-help’ (Ryfman, Citation2004). Development and humanitarian EU policies are characterized by soft law, which creates a permissive context that preserves member states frameworks (Orbie & Carbone, Citation2016).

Given the limited degree of Europeanization in development and humanitarian aid, multi-level strategies by CSOs are expected to depend much more on national contexts. Comparing two member states illustrates how the evolution of CSOs Europeanization strategies evolves in a long time period, including the effects of the euro crisis. The two countries under analysis, France and Spain, are relatively similar since they are both Western democracies. However, they differ in some of the key factors for this study such as types of political opportunities and impact of the economic crisis. Regarding aid channeled through CSOs, the differences between these two countries are striking. While France only dedicates around 1% of its total ODA to CSOs, Spain offered up to 20% in 2009 (OECD, Citation2011).

Regarding the effects of the crisis, Spain was one of the bailout countries most affected by the Euro crisis. After tapping money for its banking system, it had to fulfil the conditions set by a memorandum agreement with the EU. To cope with the crisis Spain implemented budget cuts. Among the most drastic cuts, development aid fell from 0.46% of GDP in 2008 to 0.16% in 2012 (OECD, Citation2015b). In spite of falling productivity and a stagnating economy, France, the eurozone’s second largest economy, is not facing the same constraints. Public expenditure in France has remained stable in all sectors including development assistance (OECD, Citation2015a). Given the significant divergences in these two key factors, I expect that the Europeanization strategies of CSOs from France and Spain will have evolved differently over the time period analysed.

In times of crisis, CSOs are affected by decreasing revenues and an increase in demand. It is difficult to predict with any certainty what a crisis means for the voluntary sector as a whole, given the diversity of funding sources (Paarlberg, Citation2009). All sources of revenue may be potentially affected, especially corporate donations, fees for services and non-profit assets. Swings in individual giving tend to be less severe than broader economic down turns. Many individuals tend to respond positively to appeals in times of crisis since they consider that their giving is more important than ever. Public and private donors giving in times of crisis is also normally ensured – at least for a while- by multi-annual financing instruments or the use of rolling averages. However, these buffer mechanisms have not been systematically adopted by donors all across Europe and are only effective in the event of a short crisis. Even if not all sources of revenue are equally affected in times of crisis, CSOs still face important struggles and may even enter in a true fight for survival. The most typical coping strategies include scaling back charitable work, cuts in overheads, in training programes and in staff numbers, finding fresh sources of funding and restructuring (FRP, Citation2011).

2.2.2. Type of organizations under analysis and data collection

The analysis of a variety of CSOs allows taking into account the other set of relevant factors: resources and organizational capacity. One would expect that the adoption of multi-level strategies among CSOs is affected by their size and by their level of internationalization. Large internationalized CSOs have sufficient capacity to engage in multilevel strategies and they tend to have sufficient skills to apply for larges amounts of money, finding it easier to turn to other levels. Thus, the study of the largest and internationalized CSOs is completed with the study medium-sized CSOs.

Among the largest CSOs, attention is focused on the Spanish and French sections of Oxfam, Doctors Without Borders (Medecins Sans Frontieres- MSF) and Doctors of the World (Medecins du Monde-MDM). These CSOs were selected because they are among the most popular and largest in Europe and because of the quality of the data available on their websites. They are also among those CSOs obtaining a significant amount of EU funds in absolute terms in France and Spain. These large CSOs are highly internationalized and have adopted venue shopping strategies for many years.

To complete this analysis with detailed information from medium and small CSOs, data was also retrieved from the national platforms gathering Humanitarian and Development CSOs in the countries analyzed. These platforms are Coordination Sud and Cordinadora de ONG para el desarrollo (CONGDE). Coordination Sud gathers around 160 French CSOs active in international development (including human rights and environmental CSOs). CONGDE gathers around 100 Spanish development and humanitarian CSOs (108 members in 2008 and 80 in 2014) active in 110 countries, mainly in Latin America and Africa. While no single medium or small CSOs was analyzed individually, both platforms provided relevant information on the situation of medium and small CSOs in their respective countries.

It is important to highlight that small CSOs in France and Spain have not been affected by the crisis substantially, since they were not receiving substantial amounts of public funds for ideological reasons.Footnote2 Their volume of activities remained small and based on voluntary work. According to our interviews, they did not engage in Europeanization strategies in both countries under analysis.Footnote3

Data was drawn from a variety of sources including surveys, activities and economic reports, databases and 6 semi-structured interviews. Data on public funding of CSOs was retrieved from databases such as the Financial Transparency System (FTS), Eurostat and the OECD. The FTS is an online database including information about grants offered by the EU since 2007.Footnote4 Eurostat and OECD statistics register public spending of their members on a yearly basis. Detailed data about the activities and resources of CSOs in France and Spain come from a multiplicity of sources. For the analysis of large CSOs, 47 activities and economic reports (from the 6 selected national sections) have been systematically analysed. Information about small and medium CSOs was retrieved from 10 annual surveys carried out by the Spanish platform CONGDE and by 5 multi-annual surveys carried out by the French platform (Coordination Sud) in cooperation with French Public Bodies. These surveys include data on the resources of more than 100 large and medium CSOs for each country. These sources of primary documentation were triangulated with 6 semi-structured interviews with representatives of the two platforms in the two member states under analysis and with representatives of large CSOs.Footnote5

3. The evolution of public funding for humanitarian and development CSOs in times of crisis

This section shows how funding opportunities in the EU multi-level system evolved over time, with specific attention to how they were (or not) affected by the euro crisis. EU and national funding opportunities have not been drastically altered right after the start of the economic crisis in 2008 in most European countries (CONCORD, Citation2014). This suggests that external shocks (such an economic crisis) do not translate automatically into budget cuts. The alteration of funding opportunities depended on the combination of a multiplicity of factors, including governmental agency and institutional capacity. At the EU level, given the existence of multiple veto points and long programing periods, significant cuts on short-term spending are less likely, even in cases where these cuts are a political priority. National policy-makers have much more room to reduce expenditure in the short term, but drastic budget cuts only occurred in a few countries like Spain.

3.1. Eu funding of humanitarian and development CSOs in times of crisis

The Commission was one of the first administrative bodies in Europe to set up a co-financing system for development CSOs in 1975, within the context of the crisis of the ‘developmental’ state. After a period of significant expansion during the 1980s and 1990s, EU spending reached its climax in the middle 1990s. Ever after this year, funding opportunities have stagnated (Sanchez Salgado, Citation2014a). The sector that benefits of most attention at the EU level is humanitarian aid. The EU budget for humanitarian aid has not been reduced after the financial crisis in 2008. Quite the contrary, it has continued to increase from 741 million euros in 2007 to 1273 million euros in 2012.Footnote6

Even if funds dedicated to development and human rights are not so popular, there has not been a significant reduction right after the crisis. The traditional CSO co-financing has been merged with the funding of sub-national authorities in a new programe: the Development Cooperation Instrument, which comprises 702 million euros for two years.Footnote7 The European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights also secured its funding with 390 million euros for the period 2011–2013.Footnote8 Even if the pressure was high, EU leaders did finally not make real terms cuts to the EU external spending in 2013 (CONCORD, Citation2014). Member states would have liked more significant cuts in the wake of the economic crisis, but the European Parliament tried to prevent them. The Parliament, a traditional ally of CSOs (Carbone, Citation2008), called for the maintenance of expenses, for more flexibility and for a review of the multi-financial framework in light of an eventual new economic situation (European Parliament, Citation2013). The growth of humanitarian aid remains an exception. However, the situation of other policy areas is not very different from the development and human rights policy fields.

3.2. The funding of humanitarian and development CSOs in France and Spain

Drastic budget cuts in development and humanitarian aid only occurred in Spain. Interestingly, these drastic cuts did not come right after the crisis, but around 2011, running parallel to the arrival of conservative governments into power. In France, there have been reductions of public funding on development and humanitarian aid, especially from local authorities, but they were not so significant.

The Spanish Agency for International Development (AECI) offered yearly more than 200 million euros to CSOs during the 2000s. This considerable investment in international cooperation reflects the political willingness of successive Spanish governments to raise the profile of Spain in external relations during the 2000s.Footnote9 Conservative and socialist government alike made a clear choice for the promotion of Spanish leadership in international fora, which included international cooperation and the support of CSOs. Since the late 1990s, local authorities, especially autonomous communities and city councils also supported the activities of humanitarian and development CSOs. For example, from 2007 to 2010 Catalonia channeled around 50% of all its public aid through Catalan CSOs (around 110 million euros for the whole period) (ACCD, Citation2011).

The economic crisis has significantly altered economic opportunities for development cooperation in Spain. Spain has experienced severe budget cuts in almost all items of its general government expenditure, particularly since 2010 (OECD, Citation2015b ). ODA is one of the areas that experienced the most drastic cuts in relative terms since budget cuts went from 0.46% of the GDP in 2009 to 0.16% in 2013. According to Spanish CSOs, the official development aid in Spain has been reduced by 73% (Polo, Citation2015). These cuts have obviously affected AECI’s budget and the funding of Spanish development CSOs. The most drastic cuts intervened after the change of government in 2011, when funds for CSOs were reduced by 35%.

The public spending offered by Autonomous Communities (AACC) has also been abruptly and drastically reduced. During the economic crisis, many voices have been raised challenging the need and appropriateness of decentralized aid; claiming that international aid should be an exclusive competence of the central state.Footnote10 More importantly, according to CONGD, in 2012 local authorities owed 70 million euros to around 80 Spanish development CSOs. In Catalonia, the most drastic cuts in aid came with the arrival in office of the conservative government in 2010. In 2011 the budget for development aid was reduced from 49 million to 22 million euros (FCONGD, Citation2011). Even if budget cuts have often intervened after the accession to power of conservative parties, this is not systematically the case. For example, budget cuts for development and humanitarian aid have not been so severe in the Barcelona City council, which is ruled by a conservative political party as well. Catalan CSOs have not only less funds at their disposal, they also faced delays in payments for funds approved in 2010 (FCONGD, Citation2013).

In France, the amount of domestic funds directed to development and humanitarian CSOs is considerably low compared to other European countries. During the 2000s the total amount of funds allocated to CSOs per year was around 50 million euros managed by the Mission for non-profit cooperation (MCMG) (Senat, Citation2005). During the 2000s the French government considered doubling the aid channeled through CSOs to reach the same levels of other OECD countries. However, this initiative was opposed by the Court of Auditors and many politicians and commentators (Senat, Citation2005). The funding of CSOs was criticized for lack of transparency and rigor. The senator in charge of this report also argued that since France – unlike other OECD countries- had an specific ministry for cooperation, there was no need to use CSOs to this purpose. Since 2009 onwards, the funds for CSOs are channeled through the French Development Agency (AFD). President Hollande promised that before the end of its mandate, public aid channeled through CSOs would double.Footnote11 However, no significant step has been taken towards this direction.Footnote12 In 2011 AFD offered 43,2 million euros to CSOs for a total of 71 projects.Footnote13 Since the financial crisis affected France less than Spain in terms of government expenditure (OECD Citation2015a), there have not been drastic budget cuts. As suggested in the interviews, a few local authorities might have introduced budget cuts on development Aid in the wake of the economic crisis.Footnote14 In France, around 3800 local authorities are engaged in international cooperation. Many of them offer a small quantity of funds for CSOs based on their territory of jurisdiction. For example, the French region Ile de France the wealthiest French region, offered in 2003 around 400.000 euros for CSOs based in the region for international development activities.Footnote15

4. Riding the storm in the EU multi-level system: the evolution of humanitarian and development CSOs strategies

This section shows how CSOs grant-seeking multi-level strategies have evolved on a long time period, including the changes that intervened in the wake of the economic crisis. Data show that while the evolution of political opportunities in times of crisis are a relevant explanatory factor, the choice of a Europeanization strategy also depends on other factors, especially resources and organizational capacity and the degree of internationalization. Values, identity and ideology also contribute to explain individual CSO decisions at the micro-level; but micro-level decisions are not developed in this article due to lack of space.

4.1. Spanish humanitarian and development CSOs: from negative persistence to compensation

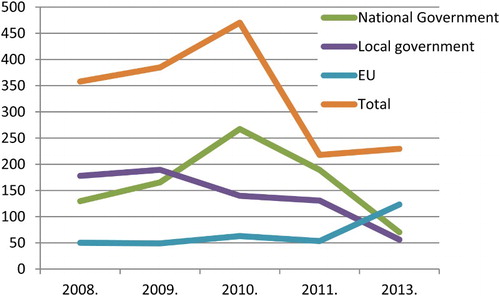

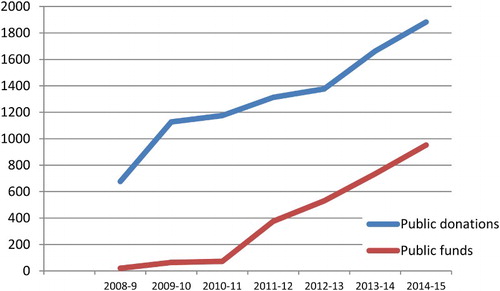

Since there have been significant budget cuts in Spain, one would expect that Spanish CSOs behavior and strategies have been much more transformed than the ones from French CSOs. The analysis of multi-level strategies of Spanish CSOs over a long time period shows indeed that their engagement in MLG depends much on domestic funding opportunities. At the beginning of the 1990s, national and sub-national funds were not very generous. In this context, Spanish CSOs applied frequently for EU funds. In some years such as 1995, they obtained on average more EU funds than national funds (Sanchez Salgado, Citation2014a). However, a considerable expansion of domestic funding opportunities during the 2000s (while EU funding opportunities remained constant) contributed to the re-nationalization of CSOs, supporting the negative persistence hypothesis and decreasing the degree of Europeanization. In the own words of a CSO representative: ‘CSOs did not ask for EU funds because they did not need them. There were many funds at the national and local level and their needs were already covered’.Footnote16 As expected, Spanish CSOs changed their strategy after the budget cuts from negative persistence to compensation. After the budget cuts in 2011, as shows, many Spanish CSOs decided to compensate the shortage of national funds with EU funds.

Figure 2. Use of public funds by Spanish CSOs 2008–2013 (in million euros). Source: elaborated by the author with figures from CONGDE repports (2008–2014). *Data for 2012 is missing.

The changes observed do not apply to all types of Spanish CSOs in the same way. The adoption of European strategies depended on the extent to which individual CSOs were affected by the crisis, on CSOs organizational capacity and on their degree of internationalization.

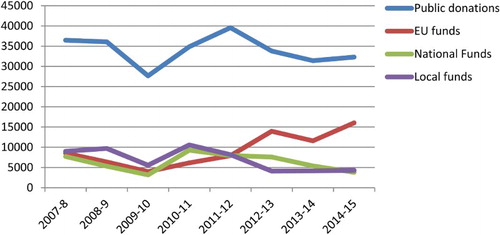

From the large CSOs under analysis, the Spanish sections of Doctors without Borders and Doctors of the World compensated the reduction of national funds with EU and international funds.Footnote17 However, given the little importance of EU funds for these CSOs in relative terms, this was not very visible in their budgets. Oxfam-Spain, -since it combines all the causes that are jointly sufficient for the adoption of an Europeanization strategy- is the clearest illustration. Oxfam-Spain initiated in 2011 a legal procedure to fire a non-negligible share of its permanent staff and reduced substantially the overheads costs (up to 14.7%) and the work time of the remaining staff (up to 10%) (Oxfam Spain, Citation2012). All these measures had to be adopted to deal with the deficit of this CSO, which in 2011 was of 4,9 million euros (Oxfam Spain, Citation2011). The adoption of a European compensation strategy is particularly visible in Oxfam-Spain ():

Spanish society still supports us, but we receive less money from business and foundations and above all, from public authorities, including both the central government and autonomic and local governments. To compensate for this loss, we are currently diversifying our funding sources. We got more support from international donors such as the European Union and the United Nations (Oxfam Spain, Citation2012:41).

Figure 3. Evolution of Funds of Oxfam-Spain 2007–2015 (thousand euros). Source: elaborated by author with figures from Oxfam-Spain repports (2007–2015).

The Spanish CSOs the most severely affected by the crisis were medium-sized and had a low degree of internationalization. Since 2010 the income of 74 Spanish CSOs went from 811 to 479 million euros and the number of projects decreased from 6200 in 2008 to 2800 in 2013 (Polo, Citation2015). According to our interviews, all medium-sized CSOs from the Catalan Federation of CSOs initiated legal procedures to fire part of their staff. They also encouraged their employees to take long sabbatical periods or to reduce their salaries. Medium-sized CSOs also reduced administrative costs, for example, by sharing office space.Footnote18

Even if the situation of Spanish CSOs was critical, including deficits and non-payments, the worst scenario (negative persistence hypothesis) did not prevail. Many Spanish CSOs engaged in a transformation process largely based on creative solutions and social solidarity. For example, the Catalan federation of CSOs initiated a negotiation with the city council of Barcelona to get free or cheap working space for medium-sized CSOs that were confronting a difficult situation. Spanish CSOs have also organized training workshops and seminars to promote best practices such as diversification of public sources of funding, fusions, and forms of auto-financing.Footnote19

While a combination of factors lead to Europeanization strategies, no single factor was a necessary condition. While Spanish medium-sized CSOs had little capacity to engage in venue shopping across levels of governance, a few of them also adopted a Europeanization strategy. For example, the Catalan federation of CSOs successfully submitted two requests for EU funding in the wake of the economic crisis (Lafede.cat, Citation2006). The Catalan Federation of CSOs did not necessarily dispose of the necessary expertise or experience to apply for a EU project. To increase its chances of success the application was submitted in partnership with a French and an Italian CSO. Ever since, they are regularly approached by other Spanish medium-sized CSOs that would like to get advice and tips to follow their example.Footnote20 According to the national platform, medium-sized Spanish CSOs were not very well connected to the EU level in the past, but in the absence of domestic funds, they are becoming increasingly concerned about the evolution of EU funding opportunities.Footnote21 Thus, the Europeanization strategy of Spanish CSOs took multiple forms: CSOs turned to several levels of governance (vertical Europeanization) and established contacts with CSOs from other countries (horizontal Europeanization).

4.2. The pervasive compensation strategy of French humanitarian and development CSOs

One should not expect such a significant change in strategy in France. On the one hand, France was less affected by the crisis and budget cuts were not drastic. On the other hand, given the little amount of French public funds on offer, Humanitarian and Development French CSOs were already (before the crisis) pursuing a compensation strategy.

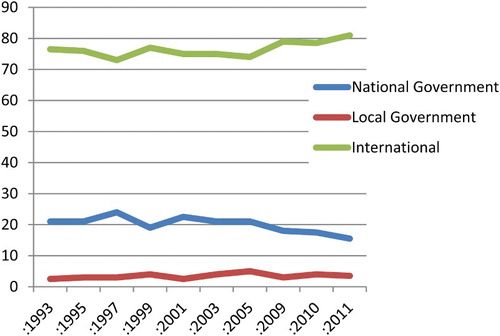

The European compensation strategy of French CSOs is indeed well established. Since French CSOs in the policy areas under analysis have traditionally only little access to domestic funds, many of them have always been largely dependent on EU funding opportunities. As shows, in the 1990s and 2000s, more than 70% of French CSO’s total public resources came from international sources while national and local funds were considerably less important. Most of French CSOs international resources come from the EU level, while international organizations are approached much less frequently (CCD, Citation2000). Regarding the origin of their public funds, French CSOs seem to be far more European than French.

Figure 4. Use of public funds by French CSOs 1993–2011 (in percentages)*. Source: Elaborated by author with data from 5 surveys carried out by the French ministry for Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, Coordination Sud and the French Agency for Development. *The same surveys show that the great majority of international funds come from the EU, but unfortunately they do not provide detailed data for all the years from 1993 to 2011.

The European compensation strategy has not been altered during the crisis in the humanitarian sector. Even during the economic crisis, the large humanitarian CSOs under analysis (Oxfam-France, Doctors without borders-France and Doctors of the World-France) experienced a process of growth. This is related to the increase in public funds and donations following another relevant external shock: the 2010 earthquake in Haiti (Coordination sud, MAE & AFC, Citation2015). The amount of EU funds channeled through French CSOs has increased significantly from 91 million euros in 2009 to 140 million in 2010, the year of the earthquake.Footnote22 Since national funding opportunities continue to be limited, large French CSOs seem to continue to rely largely in EU funding opportunities ().

Figure 5. Evolution of Funds of Oxfam-France 2008–2015 (thousand euros)*. *The EU is the most relevant public donnor of Oxfam-France. Source: elaborated by author with figures from Oxfam-France repports (2008–2015).

While there has not been any significant change in the Europeanization strategy of large humanitarian CSOs, there have been a few changes for medium-sized development CSOs. Empirical data retrieved by the French platform show that many French development CSOs have been affected by the economic crisis. Around 76% of respondent CSOs to a post-crisis survey experienced economic difficulties, mainly related to a reduction of public funds and donations (Coordination Sud and Diagonale Participative, Citation2013). Medium-sized French CSOs also lacked room to manoeuvre when confronted to a difficult economic context. Given the crisis, French medium-sized CSOs engaged in defensive strategies including the reduction of expenses, but this only seems to have affected a minority of CSOs: 22% of respondents according to the same survey. In this context of crisis, the affected French CSOs also became increasingly interested in European funding opportunities; considering a (mainly European) compensation strategy. The French platform reported that there was an increasing demand for seminars and workshops on EU funding opportunities and that when these seminars were organized, the number of participants was much higher than in the pre-crisis situation.Footnote23

Quite interestingly, the responses to the economic crisis chosen by French CSOs were often different from the ones adopted by Spanish CSOs. Much more than it has been the case in Spain, French CSOs have engaged in alliances and fusions. This concerns at least eight CSOs during the crisis period, including popular CSOs such as Première urgence-Aide Médicale Internationale (PU-AMI) (Coordination Sud and Diagonale Participative, Citation2013). Fusions and alliances grant more visibility and economy of scales, increasing the chances of obtaining EU funds. Fusions in France are not only related to the crisis, but also to the perceived need to reach a critical size to survive in a context of increased competition (Salignon, Citation2013). Since French CSOs are more dependent from international and EU funds than Spanish CSOs, the pressure to initiate a process of professionalization and be competitive is higher. French CSOs have also developed partnerships with private companies with the aim of diversifying their sources of income and contributing to the professionalization process.

5. Conclusion

This article shows the evolution of CSOs grant-seeking strategies over a long time period, contributing to a better understanding of the evolution of CSOs Europeanization strategies in a multi-level system. The analysis of a long time period showed that external effects, particularly the debt and sovereign crisis, had significant effects in CSOs Europeanization strategies when certain conditions were met. The crisis led to an increase of Europeanization strategies in Spain because of a confluence of factors such as drastic budget cuts, sufficient organizational capacity and sufficient degree of internationalization (or willingness to develop such factors). This article also shows that the euro crisis did not have the same effects when the intervening factors are not jointly sufficient, as was the case in France. France was less affected by the crisis and French CSOs were less dependent on national funding opportunities. In this country, the earthquake in Haiti also contributed more to neutralize the impact of the crisis than in other EU countries.

It is first shown that the economic crisis did not directly translate into budget cuts. For reductions in expenditure to occur, other factors were relevant such as institutional capacity and governmental agency. When CSOs were affected by budgets cuts adopted at the national level, they compensated the shortage of national funds with funds originating from other levels of governance, mainly EU funds. A complex combination of factors led to the adoption of a Europeanization strategy by many Spanish CSOs and by a few medium-sized French development CSOs. The identified Europeanization strategy depends on the combination of a multiplicity of factors and thus this in-depth qualitative study does not permit to conclude that this is a general trend across Europe.

The capacity of many CSOs to adopt Europeanization strategies in a multi-level system has interesting consequences for citizen’s participation in service delivery. The European multi-level system offers a variety of funding opportunities. In this situation of plurality of options, the autonomy of CSOs is increased. When for some reason, such as economic crisis, public funding in some member state fails, CSOs can turn to the EU and they can engage in partnerships with CSOs from other countries. However, even if the EU multi-level system offers interesting perspectives for transnational forms of citizen participation, there are also risks. The gap between ‘connected’ citizens operating in a multi-level system and small CSOs not willing (or not able) to engage in a transnational strategy could widen.

The impression among CSOs is that, within the framework of the EU Agenda for Change, funds will be increasingly directed to larger projects and that small CSOs will find it much more difficult to benefit. The EU has indeed a strong preference for the funding of projects managed by consortia composed by a great variety of CSOs from different countries. Small and medium-sized CSOs can hardly expect to become project coordinators, but their chances to get some funding via the participation in consortia may increase.

The economic crisis may also have encouraged the adoption of Europeanization strategies in other policy fields with similar funding opportunities. For example, the situation of the social sector, where the management of EU funds depends on member states, is quite intriguing. According to the new ESF regulations, at least 20% of ESF funds have to be dedicated to social exclusion activities and for the first time, the Commission has defined specific guidelines for the involvement of CSOs in the implementation process. If these principles are applied, one would expect a significant increase of Europeanization of this policy area as well.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Interview with a CSO representative, June 2013.

2 Interview with a CSO representative, June 2013.

3 Information was confirmed by two CSO representatives, June & October 2013.

4 Database available at: http://ec.europa.eu/beneficiaries/fts/, Last accessed: April 2016.

5 The names of the interviewed people are not displayed for confidentiality reasons. A detailed list of interviews has been provided to the editors and reviewers.

6 ECHO budget is available online: http://ec.europa.eu/echo/files/funding/figures/budget_implementation/AnnexI.pdf, accessed November 2013.

7 Extensive information available at: http://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/how/finance/dci/documents/brochure_low_resolution_en.pdf last accessed October 2012.

8 Extensive information available at: http://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/how/finance/dci/documents/brochure_low_resolution_en.pdf last accessed October 2012.

9 Information was confirmed by two CSO representatives, June 2013.

10 Interview with a CSO representative, June 2013.

11 (2013) François Hollande fixe un cadre à l’aide au développement, Le Monde, 2nd April.

12 Interview with representative of French CSOs, October 2013.

13 Information available at: http://www.afd.fr/home/AFD/nospartenaires/ONG/solliciter-une-subvention Accessed october 2012.

14 Interview with representative of French CSO, October 2013.

15 Information available at: http://www.iledefrance.fr/action-quotidienne/s-ouvrir-international, Accessed 5th November 2013.

16 Interview with a representative of Spanish CSO, June 2013.

17 The amount of EU funds increased considerably in the budget of MDM-Spain; but this CSO was less affected by the reduction of national public funds; and thus, the compensation strategy is less visible. MSF-Spain economic reports do not provide the amount of EU funds but the compensation strategy was confirmed during an interview.

18 Interview with a CSO representative. June 2013.

19 Interview with a CSO representative, June 2013.

20 Interview with a CSO representative, June 2013.

21 Interview with a CSO representative, June 2013.

22 Information retrieved from the Finantial Transparency System. Database available at: http://ec.europa.eu/beneficiaries/fts/, Last accessed: April 2016.

23 Interview with a CSO representative, October 2013.

References

- ACCD. (2011). Memoria 2010. Cooperació Catalana. Barcelona: Author. Retrieved April 25, 2013, from http://www20.gencat.cat/docs/cooperaciocatalana/Continguts/01ACCD/06resultats_cooperacio_catalana/01resultats_2007-2010/documents/Memoria_ACCD_2010.pdf

- Beyers, J. (2002). Gaining and seeking access: The European adaptation of domestic interest associations. European Journal of Political Research, 41, 585–612. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.00023

- Beyers, J., & Kerremans, B. (2007). Critical resource dependencies and the Europeanization of domestic interest groups. EU lobbying: Empirical and theoretical studies (pp. 128–149). New York: Routledge

- Beyers, J., & Kerremans, B. (2012). Domestic embeddedness and the dynamics of multilevel venue shopping in four EU member states. Governance, 25(2), 263–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2011.01551.x

- Callanan, M. (2011). EU decision-making: Reinforcing interest group relationships with national governments?Journal of European Public Policy, 18(1), 17–34. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2011.520873

- Carbone, M. (2008). Theory and practice of participation: Civil society and EU development policy. European Politics and Society, 9(2), 241–255.

- Chaves, M., Stephens, L., & Galaskiewicz, J. (2004). Does government funding suppress nonprofits’ political activity?American Sociological Review, 69(2), 292–316. doi: 10.1177/000312240406900207

- Cohen, J., & Rogers, J. (1992). Secondary associations in democratic governance. Politics and Society, 20, 393–411. doi: 10.1177/0032329292020004003

- Commission Coopération Développement (CCD). (2000). Résultats de l’enquête sur les ressources et les dépenses des OSI en 1998 et 1999. Paris: Author.

- CONCORD. (2014). The unique role of European Aid. The fight against global poverty. Brussels: Author. Retrieved October 22, 2015, from http://www.concordeurope.org/publications/item/275-2013-aidwatch-report

- Coordination Sud and Diagonale Participative. (2013). Etude sur les pratiques des ONG francaises dans un context financier difficile. Retrieved November 1, 2013, from http://www.coordinationsud.org/appui-aux-ong/dispositif-frio/echange-dexperiences/etudes/

- Coordination sud, MAE & AFC. (2015). Argent et associations de solidarit internationale 2006-2011. Paris: Author.

- European Parliament. (2013). Long-term EU budget negotiations: EP sets out its stance, 13 March. Retrieved April 18, 2013, from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/content/20110429FCS18370/1/html/Long-term-EU-budget-negotiations-EP-sets-out-its-stance

- Exadaktylos, T., & Radaelli, C. M. (2009). Research design in European studies: The case of europeanization. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 47(3), 507–530.

- FCONGD. (2011). La brutal davallada del pressupost de Cooperació amenaça més d'un milió i mig de persones al Sud. Barcelona: Author. Retrieved April 26, 2013, from http://www.fcongd.org/fcongd/

- FCONGD. (2013). Més de 20 ONG catalanes inicien les accions legals contra la Generalitat davant els impagaments. Barcelona: Author. Retreived April 25, 2013, from http://www.fcongd.org/fcongd/

- FRP. (2011). Voluntary organizations and the economic crisis: Riding the storm. London: FRP Advisory

- Greenwood, J. (2007). Interest representation in the European union. London: Macmillan.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2001). Multi-Level governance and European integration. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Imig, D., & Tarrow, S. (1999). The Europeanization of movements? A New approach to transnational contention. In D.Della Porta, H.Kriesi, & D.Rucht (Eds.), Social movements in a globalizing world (pp. 113–133). London: Macmillan.

- Khaldoun, A. (2014). Get money get involved? NGO’s reactions to donor funding and their potential involvement in the public policy processes. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 25, 968–990. doi: 10.1007/s11266-013-9389-y

- Klüver, K. (2010). Europeanization of lobbying activities: When national interest groups spill over to the European level. Journal of European Integration, 32(2), 175–191. doi: 10.1080/07036330903486037

- Lafede.cat. (2016). Projectes europeus. Barcelona: Author. Retrieved January 26, 2017, from http://www.lafede.cat/projectes-europeus/

- Mahoney, C. (2004). The power of institutions: State and interest group activity in the European union. European Union Politics, 5(4), 441–466. doi: 10.1177/1465116504047312

- Mahoney, C., & Beckstrand, M. (2011). Following the money: European union funding of civil society organizations. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 49(6), 1339–1361.

- Mahoney, J., & Goertz, G. (2006). A tale of two cultures: Contrasting quantitative and qualitative research. Political Analysis, 14, 227–249. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpj017

- McCauley, D. (2011). Bottom-up Europeanization exposed: Social movement theory and non-state actors in France. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 49, 1019–1042.

- Molenaers, N., Jacobs, B., & Dellepiane, S. (2014). NGOs and aid fragmentation: The Belgian case. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 25, 378–404. doi: 10.1007/s11266-012-9342-5

- Mosley, J. (2012). Keeping the lights on: How government funding concerns drive the advocacy agendas of nonprofit homeless service providers. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22, 841–866. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mus003

- OECD. (2011). How DAC members work with civil society organizations. Paris: Author.

- OECD. (2015a). Country statistical profile. Spain. Retrieved October 22, 2015, from http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/country-statistical-profile-france_20752288-table-fra.

- OECD. (2015b). Country statistical profile. Spain. Retrieved October 22, 2015, from http://www.oecdilibrary.org/economics/country-statistical-profile-spain_20752288-table-esp.

- Orbie, J., & Carbone, M. (2016). The Europeanisation of development policy. European Politics and Society, 17(1), 1–11. doi: 10.1080/23745118.2015.1082688

- Oxfam Spain. (2011). Memoria 2010-11. Barcelona: Author.

- Oxfam Spain. (2012). Memoria 2011-12. Barcelona: Author.

- Paarlberg, L. E. (2009). Nonprofits and the economic recession (Discussion paper). Retrieved April 18, 2013, from http://www.cof.org/files/Documents/Family_Foundations/Philanthropy-and-the-Recession/Nonprofits-and-the-Economic-Recession.pdf

- Polo, Y. (2015). Informe del sector de las ONGD. Madrid: CONGDE. Retrieved January 26, 2017, from, http://coordinadoraongd.org/2015/05/informe-del-sector-de-las-ongd-la-solidaridad-ciudadana-por-encima-del-compromiso-politico-con-la-cooperacion/ocde

- Ryfman, P. (2004). Les ONG. Paris: La Decouverte.

- Salignon, P. (2013). Les ONG face a la crise: Tentative d’état de lieux et de réflexions prospectives. L’Humanitaire, 35, 80–97.

- Sanchez Salgado, R. (2010). NGO structural adaptation to funding requirements and prospects for democracy: The case of the European Union. Global Society, 24(4), 507–527. doi: 10.1080/13600826.2010.508986

- Sanchez Salgado, R. (2014a). Europeanizing civil society: How the EU shapes civil society organizations. Houndmills: Palgrave.

- Sanchez Salgado, R. (2014b). Rebalancing EU interest representation? Associative democracy and EU funding of civil society organizations. Journal of Common Market Studies, 52(4), 337–353. doi: 10.1111/jcms.12092

- Saurugger, S. (2005). Europeanization as a methodological challenge: The case of interest groups. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 7(4), 291–312. doi: 10.1080/13876980500319337

- Senat. (2005). Rapport d’information relative aux fonds octroyés aux ONG françaises par le ministère des affaires étrangères, N46. Paris: Author.

- Steen, O. I. (1996). Autonomy or dependency? Relations between non-governmental international Aid organizations and government. Voluntas, 7(2), 147–159. doi: 10.1007/BF02354109

- Stephenson, P. (2013). Twenty years of multi-level governance: ‘Where does it come from? What is it? Where is it going?’Journal of European Public Policy, 20(6), 817–837. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2013.781818