ABSTRACT

Internationally, the social-liberalism of the Third Way is experiencing a deep crisis. The Netherlands is no exception to the trend. In the 2017 elections, the Dutch social democrat party suffered the worst defeat in Dutch parliamentary history. At the same time, the Dutch Third Way distinguishes itself from its more famous Anglo-American counterparts by its implicit character. Social democrat leaders in the Netherlands have sought to downplay the idea of a break with traditional social democracy, combining a Third Way agenda with more classically social democratic rhetoric. As a result, the crisis has taken on a different form. The Dutch social democrat party is commonly associated with a wholesale lack of principles and ideas, rather than with the Third Way. As such, the curious case of the Dutch Third Way might be illustrative of a broader, ‘muffled’ crisis in other countries where the Third Way has been adopted in a more implicit manner.

1. Introduction

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a wave of academic publications assessed the adoption by social democrat parties of the Third Way, a middle course between Keynesian social democracy and neoliberal supply side policies (Giddens, Citation1998; Hale et al., Citation2004; Kersbergen, Citation2003; Lewis & Surender, Citation2004; Merkel et al., Citation2008). Since the financial crisis of 2008 and the ensuing electoral defeats suffered by Third Way social democracy in large parts of Western Europe, a more recent series of studies seeks to address what it identifies as the ‘political failure’ of the Third Way (Arndt, Citation2013; Cramme & Diamond, Citation2012; Keating & McCrone, Citation2015; Manwaring & Kennedy, Citation2017; Meyer & Rutherford, Citation2012; Ryner, Citation2010). Scholars have argued that the recent electoral defeats signify a clear rejection of the Third Way agenda by the electorate (Arndt, Citation2013; Arndt & Kersbergen, Citation2015; Schumacher, Citation2012). The embrace of neoliberalism by Third Way social democrats rendered them powerless to posit alternatives to the free market ideas that are widely seen to have contributed to the financial crisis (Davies, Citation2012; Meyer & Rutherford, Citation2012; Newman, Citation2013; Ryner, Citation2010). A series of proposals have been formulated for a ‘clean break from a decade of Third Way policies’ (Meyer & Rutherford, Citation2012, p. 3).

This more recent wave of scholarship generally departs from an explicit Third Way politics as has been the case in the British context, which has often served as the reference point for international discussions on the Third Way. But the rise and subsequent crisis of Third Way politics has not generally been as clear-cut. One of the notable conclusions of comparative analyses is that ‘a full-blown and explicit Third Way discourse was prominent in a relatively small number of countries, most notably the US and the UK’, while the Third Way agenda was ‘introduced more stealthily in others’ (Lewis & Surender, Citation2004, pp. 6–7). Seeing that the rise of the Third Way has manifested itself in a more implicit manner in these countries, the crisis of the Third Way is likely to play out differently too. Instead of open discussion, adaptation and/or rejection of Third Way ideas and principles, we are more likely to encounter complaints on the wholesale absence of clear ideas and principles. In this paper, a revision of the history of the Dutch Third Way – based on an extensive analysis of publications by party members and interviews with party leaders in the Dutch media – serves to underline this argument.

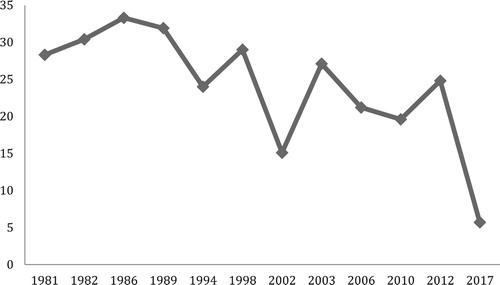

While the Dutch social democrat party (PvdA, Partij van de Arbeid) is rightly seen as one of the pioneers of the Third Way policy agenda, the party leadership has hesitated to publicly commit itself to the Third Way. The party has combined a Third Way policy agenda with more traditional social democratic rhetoric. As a result, the historic defeat of the Dutch social democrat party in the elections of March 2017 – it lost 29 of its 38 seats, out of 150 seats in total (see ) – has generally not been linked with the Third Way. Instead, it has come to be associated with a long-term crisis of political identity dating back to the early 1990s. In contrast to the UK, where the Third Way has been the subject of an open power struggle in the Labour Party between a Blairite and a Corbynite wing, or the US, where the campaign of Bernie Sanders has mounted a challenge to the Third Way legacy of the Clintons, the lack of clarity surrounding the Third Way in the Netherlands has prevented a similar confrontation. As such, the Dutch experience could be representative of a wider range of cases where the Third Way has been adopted in a more implicit manner.

The argument is divided into five sections. It opens with an elaboration on the implicit character of the Dutch Third Way. It then links the hesitancy by Dutch social democrats to publicly embrace the Third Way with the persistent discussions on the party’s identity crisis. The remainder of the paper is dedicated to a revision of the rise and crisis of the Dutch Third Way, divided into three periods. First, the emergence of the Third Way under the so-called ‘Purple’ cabinets, and the leadership of Wim Kok (from 1987 till 2001), when there is a break with the old democratic socialist ideology, but Kok keeps his distance from the Third Way label. Second, the period under Ad Melkert and Bos (from 2001 till 2012), when there is a failed ‘coming out’ of the Third Way. And third, the eventual crisis under Diederik Samsom and Lodewijk Asscher (from 2012 till 2017), when the PvdA joined a centrist coalition government, enacted drastic austerity policies and suffered a dramatic electoral defeat.

2. The Third Way and Dutch introversion

The Third Way emerged internationally in the mid-1990s, under the leadership of Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, as an attempt of centre-left parties to regain the political initiative (Giddens, Citation1998; Hale et al., Citation2004; Lewis & Surender, Citation2004; Merkel et al., Citation2008). The core idea of the Third Way is that the market is a more effective instrument than government on many terrains, and that bolstering rather than curtailing the market mechanism, can be made to serve social ends. An authoritative overview of the Third Way policy agenda is given in the Blair-Schröder paper, which mentions a long list of supply-side policy measures (Blair & Schröder, Citation1999). A communicative Third Way discourse legitimized the new policy mix in terms of community, responsibility and opportunity (Fairclough, Citation2000; Hale et al., Citation2004; Le Grand, Citation1998, March 6). The Third Way was framed as a necessary response to globalization and presented as a hard ‘Manichean’ break with traditional social democracy (Randall, Citation2009, p. 196; Schmidt, Citation2002; Watson & Hay, Citation2003).

As mentioned above, the Dutch case occupies a somewhat paradoxical position in the academic debate on the Third Way. On the one hand, the Dutch social democratic party has been described as an early frontrunner of the Third Way agenda as elaborated by Blair and Clinton. Most famously, Bill Clinton hailed Wim Kok as a trailblazer at an international Third Way conference in Washington D.C. in 1999 (Giddens, Citation2000a). The Dutch social democrat party is said to have developed a Third Way politics avant la lettre (Cuperus, Citation2001, p. 165; Green-Pedersen & Kersbergen, Citation2002, p. 508; Hemerijck & Visser, Citation1999). According to Green-Pedersen et al. (Citation2001, p. 320) it is justified to speak of a Dutch Third Way as a ‘fairly coherent set of supply-side policy intentions’, with many similarities to the Blair-Schröder paper.

The Dutch example has even been presented – with some reservations – as a ‘model’ to be emulated by other social democratic parties (Cuperus, Citation2001, p. 166; Green-Pedersen et al., Citation2001, p. 309). Moreover, the think tank of the Dutch social democrat party has been at the forefront of the development of the Third Way agenda in international networks (Cuperus, Citation2001; Cuperus & Kandel, Citation1998). René Cuperus, senior member of the Dutch social democrat think tank, lauded the Dutch model, which he labelled ‘the tulip-variation of the Third Way’, in an edited volume published jointly by the Dutch, German and Austrian social democrat think tanks (Cuperus, Citation2001, p. 166). Subsequent leaders of the PvdA have been prominent guests of events organized by Policy Network, the international Third Way think tank. Wouter Bos, party leader from 2003 till 2010, was dubbed ‘darling of the Third Way’ by Peter Mandelson, the former spin-doctor of Blair (De Waard, Citation2006, May 20).

On the other hand, Dutch social democrats have always kept a cautious distance to the Third Way label. They have wavered in identifying themselves as such and denied that there has been a break with traditional social democracy. Wim Kok actively implored his social democratic colleagues to be cautious with their political rhetoric and to ‘not fly the Third Way flag too exuberantly’ (Zwaap, Citation1999, November 10). His successor Wouter Bos disavowed the existence of a break with traditional social democracy and presented the Third Way as ‘mainstream social democracy, nothing more and nothing less’ (Bos, Citation2010, p. 6). Understandably, René Cuperus lamented the lack of courage among the PvdA leadership to make the Third Way agenda explicit, and to openly confront the more traditionalist wing of the party (Cuperus, Citation2000, March 3).

The political philosopher Steven Lukes once wrote that the ambiguity of British Third Way rhetoric served to obscure internal ideological conflicts and enable political leaders to pursue their own goals while winning the votes of ideologically motivated voters. (Lukes, Citation2000, p. 100) Probably this is, even more, the case for the Dutch Third Way. Contrary to countries such as the US and the UK, the Netherlands has no majoritarian voting system. The electoral centre is, therefore, less important and the PvdA is more vulnerable to competition on its left flank. There is, therefore, a larger need to keep the leftist voter on board. Cuperus argued that point in a newspaper interview (Valk, Citation2007):

Bos wanted from the beginning to be the Dutch Tony Blair. He moved to the middle to become the biggest party. But that only works, it turns out, in a two-party system. In the Netherlands, space immediately opens up on the left flank and the SP [Socialist Party] comes in. The base of the party is much more leftist and traditional than the leadership thinks.

In the Netherlands, this resulted not only in vague rhetoric but also in ideological ambiguity. In her work on discourse and political transformation, Vivien Schmidt distinguishes between a ‘coordinative discourse’ primarily focused on developing new policy agenda among an elite of policy makers and a ‘communicative discourse’, focused on normatively legitimizing a policy shift in the eyes of the larger public (Schmidt, Citation2002, pp. 232–239). The Dutch Third Way seems to exemplify a successful coordinative discourse heralding a broad policy shift among the leadership of the social democrat party, combined with the failure by social democrats to develop a new communicative discourse to publicly legitimize that shift. Instead, party leaders have fallen back on a more classical social-democratic communicative discourse to defend their policies to the broader public.

On the 1st of May, the leadership of the PvdA still sings The Internationale. At jubilees, the party nostalgically cherishes the very socialist tradition it has publicly severed ties with in the 1990s. Party chairman Hans Spekman is known to call for ‘rallying political forces against capital’ (De Volkskrant, Citation2015). While his party colleague at the time, then finance minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem, gained an international reputation for his preferential treatment of the Dutch financial sector and the Dutch tax evasion industry (Becker et al., Citation2015, November 6). This combination of a Third Way policy agenda and a more traditional social democrat communicative discourse has not been consistent. Over time, the party has kept on vacillating between public embrace of the Third Way and the public disavowal of the social-liberal break with traditional social democracy. The result of this wavering attitude, this paper argues, has been an ongoing identity crisis, contributing significantly to the party’s eventual electoral demise.

3. The identity crisis of Dutch social democracy

The identity crisis of the Dutch social democrat party has been a longstanding and recurring theme in Dutch public opinion. Ever since Wim Kok proclaimed to have rid the party of its ‘ideological feathers’ in a landmark speech in 1995, uncertainty prevails concerning what has come in their place. This ‘riddle of the missing feathers’ is a discussion that has kept Dutch commentators busy for years, if not decades. In satirical newspaper cartoons, the party has been depicted as a plucked and grilled chicken. No other Dutch party has seen its identity crisis become such an integral part of its political culture.

‘The only way to describe the present situation of the PvdA, is the word crisis’. Ruud Koole, a prominent social democrat and political science professor, wrote this sentence – since become aphorism – in a comparative analysis of the struggle of European social democrat parties in the early 1990s. It was the time of the difficult transition from the old, Keynesian social democratic politics to the social-liberalism of the Third Way. ‘A party can’t limit itself to abandoning positions, it has to replace them with something’, Koole (Citation1993, pp. 93–95) wrote, expressing the soul-searching of the time. ‘Only a new body of ideas and not just a nice idea can provide the basis for the recovery of the PvdA’. In the typical fashion history responds to such appeals, Koole was soon given what he was pleading for, even though it wasn’t much to his liking. One year later, in 1994, Tony Blair was elected leader of the Labour Party. Together with the sociologist Anthony Giddens, he would become the main exponent of the Third Way, the political ideology that would replace the traditional social-democratic politics in large parts of Europe (Giddens, Citation1998; Hale et al., Citation2004; Lewis & Surender, Citation2004; Merkel et al., Citation2008). As noted, the PvdA remained ambiguous towards the Third Way. The new ideology served predominantly an internal function, as an instrument of cohesion for the increasingly dominant social-liberal wing of the party. As a result, discussions on the political identity crisis of the party kept recurring.

In 1993, Ruud Koole argued that ‘the most important reason for the crisis of the PvdA’ is that the party is ‘incapable of formulating a clear social-democratic answer to the socio-economic problems of this time’ (Koole, Citation1993, p. 92). By entering government in 1989, the party had abandoned its traditional moorings but had trouble replacing these with something new. In 1998, after participation in the first ‘Purple’ coalition government (1994–1998) with the right-wing liberal party VVD (Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie), the PvdA-senator Thijs Wöltgens asked whether the PvdA would continue with that agenda or whether it would look for an ‘appropriate opportunity to make its identity visible’ (Wöltgens, Citation1998, p. 371). In 2002, due to an impressive election victory of the right-wing populist party LPF (List Pim Fortuyn), the PvdA lost a dramatic twenty-two seats, fifteen per cent of the total vote. In the party’s evaluation report, the disaster was attributed to the fact that the ‘social-liberal centrist course has barely been internalised by the party’, leading to a fatal ‘lack of conviction and sense of direction’ (Becker & Cuperus, Citation2002, p. 85). In the elections of 2006, the PvdA lost eight seats due to the breakthrough of a left-wing competitor, the Socialist Party. An official party evaluation, written by former party chairman Ruud Vreeman, explained how ‘the political vision with which [the new party leader] Wouter Bos started his party leadership’ in 2002, did not sink in ‘to the hearts and minds of party members’ and ‘remained too much his personal vision’ (PvdA, Citation2007, p. 15). At the time of the report’s publication, an article appeared in the Dutch newspaper of note, NRC Handelsblad, with the familiar subtitle ‘The PvdA is in crisis’. Senior party members were interviewed who doubted what the party stood for, and what segment of the population it was supposed to represent (Valk, Citation2007). In February 2012, after the early resignation of Wouter Bos’ successor Job Cohen, the newspaper Trouw wrote: ‘The PvdA is in an unprecedented crisis’. The editorial concluded: ‘There is nobody with a convincing idea of what the position of the PvdA ought to be’ (Trouw, Citation2012). At the end of 2014, when a renewed crisis sets in because the party reached a historical low in the polls, the circle is squared. Sheila Sitalsing, prominent columnist of de Volkskrant, remarked on the ‘timeless truth’ of the sentence that Ruud Koole wrote in 1993: ‘The only way to describe the present situation of the PvdA, is the word crisis’. She concluded in now familiar fashion: ‘The PvdA has no idea what it stands for’ (Sitalsing, Citation2014).

Of course, it is normal for any political party to experience recurring political crises. The exceptional element here is that every time that a crisis occurs, no one seems to have a clear idea of what the PvdA actually stands for, or what it ought to stand for. This notion of identity crisis that has come to define the public image of the social democrat party over the decades needs to be approached with a degree of caution, however. A party without a clear idea or a minimal consensus concerning the course to be followed is bound to be chaotic, free-floating and directionless; incapable of the discipline required for governing. In contrast, the PvdA is known to be a very disciplined party. When discord emerges about the direction of the party, the party leadership is known to intervene in resolute manner, criticized by party MPs as ‘excessive paternalism’ (De Volkskrant, Citation2006, April 27).

Intriguing is that the observations of a lacking sense of direction in the abovementioned analyses, often go hand in hand with the observation that the social-liberalism of the Third Way remains dominant within the party. That is what party intellectuals Frans Becker and René Cuperus state after the demise of the ‘purple’ coalition in 2002 (Becker & Cuperus, Citation2002). Likewise, future leader Diederik Samsom explained in 2007 that the Third Way ‘still prevails in the PvdA’ (Valk, Citation2007). And the leftist social democrat senator Adri Duijvestein remarked in 2014, in seemingly euphemistic fashion, that ‘the social-liberal wing is rather well represented among the party leadership’ (Verbraak, Citation2014). The picture that emerges from the writings of senior party members such as Wouter Bos (Citation2002, Citation2010), René Cuperus (Citation2001), Rick van der Ploeg and Jet Bussemaker (Citation2001), and Frans Timmermans (Citation2010)), can be interpreted as a reasonably coherent Third Way discourse. Similarly, the impression one gets from the political speeches of Bos (Citation2005, Citation2008) and Asscher (Citation2014, Citation2015) at the international Third Way think tank Policy Network is not one of confusion. The party leadership appears to have a quite clear idea what the party stands for. The uncertainty is whether to convey it to the public, and how.

4. Rise and disavowal of the Dutch Third Way (1989–2001)

How did this ambiguous politics come into being? The formation of the CDA-PvdA government Lubbers III on the 7th of November 1989, paved the way for a transformation of Dutch social democracy. The core of this political metamorphosis consisted of a change in macro-economic policy from keynesianism to a supply side approach, a shift towards the political centre and the emphasis on an activating welfare state and personal responsibility. Only five years later, this policy programme would come to full fruition in the ‘Purple’ coalition governments that were in power from 1994 till 2002. (The label ‘Purple’ refers to the combination of the party colours of PvdA and the right-wing liberals VVD, red and blue.) In the Netherlands, the word ‘Purple’ functioned as the far better-known synonym for the Third Way. It is telling that Giddens’ book on the Third Way was translated in Dutch as ‘Purple, the Third Way’ (Giddens, Citation2000b).

The transition was long in the coming. The Keynesian demand management policies that served as the basis for the PvdA’s course under the leadership of Den Uyl, entered into a severe crisis of legitimacy in the 1970s. In the 1980s a wide range of supply-side reforms was enacted, led by the three-term Lubbers government (Green-Pedersen et al., Citation2001; Touwen, Citation2014). If the PvdA wanted to remain in the picture as a potential coalition partner, then it needed to distance itself from its Keynesianism and its leftism. Shortly after the elections of 1986, former trade union leader Wim Kok succeeded Den Uyl, and ‘the blinds were opened’ (Koole, Citation1993; Beus & Notermans, Citation2000). The renewal project that followed was conceived in a series of reports at the end of the eighties – Politics a la Carte (Politiek à la Carte), Shifting Panels (Schuivende Panelen) and Stirred Movement (Bewogen Beweging) – in which respectively party organization, political goals and strategy were discussed (Koole, Citation1993).

In a famous lecture in 1995, Wim Kok marked a clear break with the democratic socialism of Den Uyl. He spoke of the ‘liberating effect of shedding the ideological feathers’, and distanced himself from old school social democracy: ‘A true renewal of the PvdA begins with a definitive departure from socialist ideology; with a definite severing of the ideological ties with other heirs of the traditional socialist movement’ (Kok, Citation1995). He followed that up by adding that this separation had, by the time of his speech, been as good as completed. Kok refrained, however, from replacing the traditional social democrat politics with something new. In contrast to the US and Great Britain, where the Third Way was loudly proclaimed to be the new party identity, Wim Kok took care not to profile himself that way.

In the 1998 State of the Union Bill Clinton triumphantly declared: ‘We have moved past the sterile debate between those who say government is the enemy and those who say government is the answer. My fellow Americans, we have found a Third Way’ (Clinton, Citation1998, January 27). One year later, an international gathering took place in Washington on the Third Way, where Wim Kok was a guest of honour. Clinton introduced him as follows: ‘Wim Kok, from the Netherlands, actually was doing all this before we were. He just didn’t know that – he didn’t have anybody (…) who could put a good label on it’. Kok reluctantly agreed that he ‘put it into practice without having the label on it, the Third Way’ (Bos, Citation2010, p. 4). What Clinton didn’t know, however, is that Wim Kok had political reasons to spurn good labels. Kok immediately qualified his admission, remarking that the Third Way is, in reality, a very broad Third Avenue. Among political colleagues, Wim Kok admitted being a great fan of the Third Way (Giddens, Citation2000a, p. 5). Publicly, he insisted there was no need for new grand narratives. On the 21st congress of the Socialist International in Paris, Wim Kok advised his ‘international comrades to not fly the Third Way flag too exuberantly. It is about renewal, not terminology’ (Zwaap, Citation1999, November 10). At the inauguration of the first Purple coalition government in 1994, Wim Kok had minimized its symbolic importance, calling it a ‘perfectly ordinary cabinet’. This in sharp contrast with the British and American case, where an extensive new terminology was introduced – starting with the renaming of the party: New Democrats and New Labour – to mark a ‘Manichean contrast’ with the past (Randall, Citation2009, p. 196).

The officious motto of the Dutch Third Way under Wim Kok could be summarized as ‘show, don’t tell’. In the party journal Socialisme & Democratie, prominent social democrats voiced their discontent with this strategy of disavowal. Jos de Beus (Citation2000, p. 13) commented drily on the notable difference with the international context: ‘Strange actually: while almost all prominent statesmen and commentators abroad associate Kok’s leadership with the Third Way, in the kitchen of Kok himself, the Third Way seems to be a discussion for discussion’s sake where the PvdA can freely opt out of’. In a retrospective on the Purple cabinet under Kok, the economist Paul de Beer (himself a prominent advocate of the Third Way) argued that the policy shift under Kok was hidden behind the compromises with coalition partner VVD. De Beer described a conflict within the party between a classic social-democratic current, referred to as a trade union wing, and a modern social-liberal current. According to De Beer, the trade union wing favoured a strong presence of the state, curtailing the market, limiting income inequality and reserving a prominent role for the trade unions. The social-liberals, in contrast, underlined the limited steering capacities of the government, wanted to realize social goals through the market, and preferred the equal opportunity to equal outcomes. According to De Beer, this internal conflict was actively obscured by the party leadership. When the PvdA entered into a historic coalition government with the VVD and became part of the purple coalition in 1994, the party opted for a social-liberal course that wasn’t communicated to the public as such:

The liberal policy of this government could be attributed to the VVD, so that the PvdA apparently could stay true to its traditional positions, albeit diluted to social-liberal government policy. In so doing the PvdA, under the leadership of former trade union leader Wim Kok, entered a completely new path in the nineties, without any serious internal debate’. (De Beer, Citation2004, p. 68)

Purple was, in terms of a social-liberal centrist course for the PvdA, internalised by four members of government and three MP’s at most. The rest of the party cadre and base sat with the red buttocks pressed together, relating uncomfortably to Purple and the ‘class enemy’ VVD. […] Purple has never been internalised by the party base; many felt that the liberals in Purple had the last laugh. The party leadership has not perceived, confronted or overcome the resistance. […] The real course of Kok, the flirt with the centre position in the Dutch political spectrum by a combined orientation on a strong supply-side economy and a modern, activating welfare state, has not been made subject of debate and programmatic renewal in the PvdA after the intense debates on disability benefits in the beginning of the nineties. No courageous Clause Four-confrontations between Kok and his party, let alone an independent design of a Dutch version of the Third Way. There was only that one Den Uyl-lecture, the shedding of the ideological feathers, but that remained without consequence, like an opening gambit in a never continued chess game. (Becker & Cuperus, Citation2002, p. 84)

5. The failed ‘coming out’ of the Dutch Third Way (2001–2012)

Because Wim Kok was wary of a new narrative that would make the party’s change of direction explicit, the so-called ‘Third Way-debate’ only really started at the end of his term (De Beus, Citation2000). In this period, proponents of the Third Way within the party repeatedly complained that the ‘true course’ of the party was not openly communicated towards the public. The ‘PvdA has to embrace the Third Way with conviction’, Cuperus (Citation2000, March 3) advised in an opinion piece. The party ‘will have to arrogate the factual course of Kok to a much greater degree and make it more its own’. A similar plea could be heard from the party executive committee member Gritta Nottelman and the political scientist Kees van Kersbergen: ‘Openly admitting to the Third Way is the way to give the party new ideological feathers’ (Kersbergen & Nottelman, Citation2001, p. 40). The year before, Van Kersbergen (Citation2000, p. 280) had published a noteworthy essay in the party journal, titled ‘The inevitability of the Third Way’. He pleaded for a public embrace of the Third Way and described this agenda in terms of a striving to ‘transform the welfare state from a passive, bureaucratic and centralized monster, focused on handing out benefits’ to a ‘social investment state’ that fosters maximum participation and decentralizes power. The call within the party to more explicitly own up to the new centrist course coincided with the international promotion of the Third Way by Giddens, Blair and Schröder. In the years 1999, 2000 and 2001, the Dutch party leadership cautiously discussed the Third Way in a series of publications, seeking to find a middle way between the Anglo-Saxon and the continental Third Way model (Becker & Cuperus, Citation1998; Bos, Citation2002; Bussemaker, Jet en Van der Ploeg, Citation2001; Cuperus, Citation2001). Key Third Way ideas were now imported from abroad.

Many of the changes in political and electoral strategy that the Third Way implied, were expressed in the concept of the ‘radical centre’. It originated with Giddens (Citation1994), who gave new meaning to radicality and progressiveness in his book Beyond Left and Right. According to Giddens, radicality was in essence synonymous with progressiveness. It meant willingness to enact change and the conviction that one can shape history. That political optimism, Giddens noted, had changed sides and could now be found among the proponents of neoliberalism and (neo)conservatism. Socialism had become a conservative movement, because it aimed at the preservation of the welfare state. Giddens proposed a new ‘radical’ politics, where the word radical entailed change with regards to existing leftist thought. In the book Life after Purple? (Leven na Paars?), senior PvdA politicians Jet Bussemaker and Rick van der Ploeg (Citation2001) adopted Giddens’ concept of the radical centre. The word radical, in their words, stood for ‘the willingness to break with existing government policy and established socialist thinking’ (Bussemaker, Jet en Van der Ploeg, Citation2001, p. 20). At the same time, however, in marked contrast with the radicality implied, they qualified their appeal with hesitance and caution:

The PvdA has to keep a sound distance to the liberal version of the Third Way, just like the PvdA shouldn’t identify one hundred per cent with the policies of Purple. At the same time, we need to forcefully distance ourselves from the old-fashioned leftist agenda. Sticking to an old-fashioned left agenda will lead to a conservative politics. The PvdA has to invent the radical centre: the centre of a recognisable, left-realist agenda. (Bussemaker, Jet en Van der Ploeg, Citation2001, p. 20)

When governing parties PvdA and VVD suffered a dramatic electoral defeat in 2002, Melkert resigned and the debate on the Third Way stalled. The rise of the right-wing populist politician Pim Fortuyn and his popular critique of the policies of the Purple coalition made the label into political poison. The word became a term of derision, implying a technocratic politics disconnected from the general population. Due to this particular circumstance, Wouter Bos, the successor of Melkert, continued the Third Way agenda without much fanfare. In the party journal, Bos called the radical centre the great promise of purple, a promise that was not fully realized: ‘This possibility of radicality in combination with a broad degree of support, created by bridging traditional left-right cleavages, remains the great promise of purple. A promise that regrettably, has in many respects not been fulfilled’ (Bos, Citation2002, p. 62). But even though Bos was nicknamed ‘darling of the Third Way’ by New Labour spin-doctor Peter Mandelson and called ‘prince of Purple’ by journalists in the Netherlands, he refrained from publicly propagating the Third Way.

Only in 2010, at the end of his leadership term, did Wouter Bos expand on the Dutch Third Way in a prominent lecture, or in his own words ‘give it a place in the development of social democratic thought’ (Bos, Citation2010, p. 1). But even here we find a strategic denial of the specific character of that development: according to Bos the Third Way was ‘no victory of the social-liberals over more traditional social-democrats. It was mainstream social democracy, no more, no less’ (Bos, Citation2010, p. 6). There were no ‘large ostentatious breaks with the past’, only a very gradual and necessary correction of an excessive belief in the effectiveness of government intervention (Bos, Citation2010, p. 6). And while the Dutch Third Way consisted of ‘a decline of faith in the state’, ‘a reappraisal of the market’ and more ‘responsibility’ for people themselves, Bos argued that the combination of neoliberalism and Third Way was due to ‘tragic timing’. The ‘leading role of the Partij van de Arbeid in two purple governments’ happened to coincide with the emergence of neoliberalism and the unleashing of global capitalism (Bos, Citation2010, p. 6). Furthermore, Wouter Bos denied the defining role of British Third Way ideas on the PvdA (and on himself): ‘the Third Way was not imported by the PvdA, we did not imitate others. No, it came from inside and we were in many ways preceding our colleagues in the United Kingdom and the United States’ (Bos, Citation2010, pp. 6–7). Dutch journalists subsequently made the confusion complete, by interpreting the lecture as a break from the Third Way (Keulen & Kroeze, Citation2010). While Wouter Bos in reality suggested ‘a sympathetic reappraisal’:

Who came here tonight with the idea: in this old conventicle [the national events of the PvdA are traditionally held in an old conventicle in Amsterdam, de Rode Hoed] Wouter Bos will finally put on the hair shirt as the repentant reprobate of the sinful breed of reformers, yes, even the sinful breed of social-liberal members of the Third Way, these people are deceiving themselves. Well, half-deceiving themselves at the very least. Because the accursed Third Way is for sure worth a confession, but it also deserves a sympathetic reappraisal. (Bos, Citation2010, p. 1)

6. Austerity politics and electoral collapse (2012–2017)

Initially, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis and under the new leadership of Diederik Samsom and Lodewijk Asscher, the PvdA seemed to make a turn to the left. Bos (Citation2010) had compared the financial sector to a gorilla that had broken loose from the zoo, while Diederik Samsom proposed plans to make bankers serve society, instead of the other way around (Giebels, Citation2012). In the 2012 elections, the PvdA campaigned successfully against the austerity policies of the first Rutte cabinet and won a convincing election victory, increasing its vote share from 20 to 25 per cent. After the election, however, the PvdA quickly changed tack and formed a government with the right-wing liberal party (VVD), the second Rutte cabinet. It would continue and deepen the restrictive fiscal policies of its precursor, effectuating a total of 38 billion euros of austerity measures, a reduction of roughly 3 per cent of state spending per year (Jacobs, Citation2016; Suyker, Citation2015). Among the measures were politically delicate cuts to social security, social care, housing, education and sheltered workshops.

Even though the label Purple had by now fully disappeared from Dutch political discourse, technically this was another Purple cabinet if considered strictly in terms of party colours. Also politically, it conformed to many of the key themes of the Third Way as discussed ten years before. The coalition agreement was appropriately titled Building Bridges. The transcending of traditional left-right cleavages that Wouter Bos saw as the promise of Purple, was the official raison d’être of this government (Rutte & Samsom, Citation2012). And there was a radical break with traditional social democrat thinking – the government enacted a sweeping range of pro-cyclical austerity policies, going against the advice of the IMF (Citation2012) and OECD (Citation2012). The Minister of Social Affairs, Lodewijk Asscher, declared he did ‘not want to go down into history as an old-fashioned social democrat’ (Van Weezel, Citation2016). According to Asscher, the government could not create jobs and he preferred the Third Way policy of training schemes and private sector subsidies. Jette Kleinsma, the social democrat state secretary of Social Affairs implemented the Participation Law and oversaw an extensive cutback and decentralization of social security and social care. These reforms were sold to the public in the King's speech of 2013 (Rutte & Asscher, Citation2013) as an attempt to replace the welfare state with a 'participation society', where citizens felt responsible for solving their own problems.

Straight from the start of the new government in 2012, the PvdA plummeted dramatically in the polls. The policies that the social democrats pursued in the second Rutte cabinet were seen by many as a betrayal of the party’s social democrat values and a capitulation to the market-oriented agenda of the VVD. Even after the historic electoral defeat of 2017, the Third Way did not become a prominent topic of discussion within the party. Senior party figures as Diederik Samsom, Lodewijk Asscher, René Cuperus and Jeroen Dijsselbloem all complained that they had saved the country from its demise and were rewarded with the electoral implosion of their party. As Dijsselbloem stated in an interview (Hinrichs & Jonker, Citation2017):

I still think that what we did was necessary. Responsible and good for the Netherlands. But where we have failed as the PvdA, is that we weren’t able to take our electorate along with us. We have lost them somewhere along the way.

7. Conclusion

Commentators have jestingly likened the British Third Way to the Loch Ness Monster – everyone has heard about it, occasional eyewitness-accounts come in, but no one is really sure whether the creature really exists (BBC, Citation1999, September 27). As a consequence of the ambiguous attitude of the Dutch social democrat party towards the Third Way, this characterisation seems even more appropriate for the Netherlands. International comparative studies of the Third Way have highlighted the fact that an explicit Third Way discourse was prominent in a select range of countries, while the Third Way policy agenda was embraced more discreetly elsewhere. Up to now, discussions of the crisis of the Third Way have often taken the explicit Third Way politics as their frame of reference.

The historical review in this paper serves to underline the broader argument that the crisis of the Third Way plays out differently in countries where it has been adopted in a more implicit manner. Instead of an open emergence, success and subsequent crisis and/or rejection of the Third Way agenda, we find instead a perceived absence of identity and lack of clear ideas and principles, dating back to the very beginning of the Dutch Third Way. The relative obscurity, of the Third Way in the Netherlands, presents a series of particular challenges to social democratic renewal. It is difficult to change the politics of the party when it is unclear what agenda, the party has actually pursued in the past decades. Moreover, due to the PvdA’s continued recourse to a traditional social democrat communicative discourse to implement a Third Way policy agenda, the electorate has become distrustful of the party as such.

A core element of the Third Way was the idea that the future of Dutch politics was to be determined by the parties populating the political centre. Wouter Bos wrote in 2002 on the ‘battle for the centre that will be a constant in the politics of the coming decades’, as a consequence of long-term ‘demographic, sociological and electoral developments’ (Bos, Citation2002, p. 62). With the benefit of hindsight, this appears to have been a strategic mistake. The decade after, saw the resurgence of the parties on the political flanks, and the crisis of the political centre is also that of the Third Way. Despite all this, it is still too early to write obituaries for the Third Way, even though the vital signs do seem to be lacking.

References

- Arndt, C. (2013). The electoral consequences of third way welfare state reforms. Amsterdam University Press.

- Arndt, C., & Kersbergen, K. v. (2015). Social democracy after the third way: Restoration or renewal? Policy & Politics, 43(2), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557315X14295223027356.

- Asscher, L. (2014). Fighting injustice. Making progressive politics work in Europe and beyond, Amsterdam, April 24. Retrieved March 10, 2020, from https://www.government.nl/documents/speeches/2014/04/25/speech-by-minister-asscher-of-social-affairs-and-employment-for-conference-making-progressive-politics-work-in-europe-and-beyond.

- Asscher, L. (2015). Towards a bright future for the progressive movement. Progressive Politics in the New Hard Times, Amsterdam, September 1. Retrieved 10 March 2020 from https://vimeo.com/138004165.

- BBC. (1999, September 27). What is the third way? BBC. Retrieved January 1, 2019, from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/458626.stm.

- Becker, F., & Cuperus, R. (1998). ‘Dutch social democracy between Blair and Jospin. In R. Cuperus & J. Kandel (Eds.), European social democracy: Transformation in progress (pp. 247–255). Wiarda Beckman Stichting and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Becker, F., & Cuperus, R. (2002). Alarmfase 1! Zonder grondig zelfonderzoek gaat het niet. Socialisme & Democratie, 5/6, 82–89.

- Becker, M., Müller, P., & Pauly, C. (2015, November 6). How the Benelux blocked anti-tax haven laws. Der Spiegel International,. Retrieved March 10, 2020, from https://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/eu-documents-reveal-how-benalux-blocked-tax-haven-laws-a-1061526.html.

- Beer, P. d. (2004). Het debat over sociaal-liberalisme op herhaling. Socialisme & Democratie, 5–6, 68–73.

- Beus, J. d. (2000). De Europese sociaaldemocratie: Politiek zonder vijand. Socialisme & Democratie, 1, 10–14.

- Beus, J. d., & Notermans, T. (2000). Een taxatie van de derde weg. Beleid & Maatschappij, 27(2), 78–92.

- Blair, T., & Schröder, G. (1999). Europe: The third way/ die neue Mitte. Reprinted and commented on by Joanne Barkan. Dissent, 47(2), spring 2000, 51–65.

- Bos, W. (2002). Zoeken na(ar) Paars. Socialisme & Democratie, 1, 60–64.

- Bos, W. (2010). De derde weg voorbij: 21e Den Uyl lezing. Retrieved January 1, 2019, from https://www.pvda.nl/nieuws/den-uyl-lezing-wouter-bos/.

- Bos, W. (2005). New dilemmas on solidarity. Policy Network, London, March 12. Retrieved March 10, 2020, from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/democracy/news/2005/04/07/1433/new-dilemmas-on-solidarity/.

- Bos, W. (2008). Modernising social democracy: Back to the future. Policy Network , London, April 4. Retrieved March 10, 2020, from: https://www.pvda.nl/wp-content/uploads/2008/04/10669-pvda-wouterbos-speechmodernisingsocialdemocracy.pdf .

- Bussemaker, Jet en Van der Ploeg, R. (2001). Rood in paars: Visie op een links-radicale politiek. In J. Bussemaker & R. van der Ploeg (Eds.), Leven na Paars? (pp. 11–40). Prometheus.

- Clinton, B. (1998, January 27). Text of President Clinton's 1998 State of the Union Address. The Washington Post.

- Cramme, O, & Diamond, P. (2012). After the third way: The future of social democracy in Europe. London: I.B. Taurus.

- Cuperus, R. (2000, March 3). Pvda moet zich met overtuiging op de derde weg richten. NRC Handelsblad.

- Cuperus, R. (2001). The new world and the social democratic response. In R. Cuperus, K. Duffek, & J. Kandel (Eds.), Multiple third ways: European social democracy facing the twin revolution of globalisation and the knowledge society (pp. 153–169). Wiarda Beckman Stichting.

- Cuperus, R, & Kandel, J. (1998). European social democracy: Transformation in progress. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Davies, J. S. (2012). Active citizenship: Navigating the conservative heartlands of the New Labour project. Policy & Politics, 40(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1332/147084411X581781

- Depla, P. (2017). Op de toekomst. Den Haag.

- De Volkskrant. (2006, April 27). Bos trekt de teugels van zijn fractie alvast strakker aan, De Volkskrant.

- De Volkskrant. (2015). Spekman: 'Links moet samenwerken tegen grootkapitaal'. De Volkskrant.

- Fairclough, N. (2000). New Labour, New Language. Routledge.

- Giddens, A. (1994). Beyond left and right: The future of radical politics. Stanford University Press.

- Giddens, A. (1998). The third way: The renewal of social democracy. Polity Press.

- Giddens, A. (2000a). The third way and its critics. Polity Press.

- Giddens, A. (2000b). Paars, de derde weg: Over de vernieuwing van de sociaaldemocratie. Baarn/Antwerpen: Houtekiet.

- Giebels, R. (2012, August 15). PvdA wil ABN Amro in overheidshanden houden. De Volkskrant.

- Green-Pedersen, C., & Kersbergen, K. v. (2002). The politics of the “third way”: The transformation of social democracy in Denmark and the Netherlands. Party Politics, 8(5), 507–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068802008005001.

- Green-Pedersen, C., Kersbergen, K. v., & Hemerijck, A. (2001). ‘Neo-liberalism, the “third way” or what? Recent social democratic welfare policies in Denmark and the Netherlands. Journal of European Public Policy, 8(2), 307–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760110041604.

- Hale, S., Leggett, W., & Martell, L. (2004). The third way and beyond: Criticisms, futures and alternatives. Manchester University Press.

- Hemerijck, A., & Visser, J. (1999). The Dutch model: An obvious candidate for the ‘Third Way. European Journal of Sociology, 40, 103–121. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975600007281.

- Hinrichs, J., & Jonker, U. (2017, May 29). Wij hebben de afgelopen jaren al het land gered, nu gaan we de partij redden. Financieel Dagblad.

- IMF. (2012). World economic outlook.

- Jacobs, B. (2016). De rekening van Rutte. Retrieved January 1, 2019, from https://basjacobs.wordpress.com/2016/09/19/de-rekening-van-rutte/.

- Keating, M., & McCrone, D. (2015). The crisis of social democracy in Europe. Edinburgh University Press.

- Kersbergen, K. v. (2000). De onontkoombaarheid van de “derde weg”. Socialisme en Democratie, 6, 275–283.

- Kersbergen, K. van. (2003). The politics and political economy of social democracy. Acta Politica, 38, 255–273. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500032.

- Kersbergen, K. v., & Nottelman, G. (2001). De derde weg en de Nederlandse Politiek. In J. Bussemaker & R. van der Ploeg (Eds.), Leven na Paars? (pp. 40–51). Prometheus.

- Keulen, S., & Kroeze, R. (2010). Breken met het verleden. Socialisme & Democratie, 3, 54–62.

- Kitschelt, H. (1994). The transformation of European social democracy. Cambridge University Press.

- Kok, W. (1995). We laten niemand los. Den Uyl-lezing 1995. Retrieved January 1, 2019, from https://europanetwerk.pvda.nl/nieuws/den-uyl-lezing-1995-wim-kok-we-laten-niemand-los/.

- Koole, R. (1993). De ondergang van de sociaaldemocratie: De PvdA in vergelijkend en historisch perspectief. Socialisme & Democratie, 7, 73–98.

- Kranenburg, M. (2002, January 11). De derde weg loopt dood, NRC Handelsblad.

- Le Grand, J. (1998, March 6). The third way begins with CORA, New Statesman, 26–27.

- Lewis, J., & Surender, R. (2004). Welfare state change: Towards a third way? Oxford University Press.

- Lukes, S. (2000). Een doodlopende weg? Het laatste woord over de Derde Weg. Beleid en Maatschappij, 27(2), 99–100.

- Manwaring, R., & Kennedy, P. (2017). Why the left loses: The decline of the centre-left in comparative perspective. London: Policy Press.

- Melkert, A. (2001, 29 November). Nieuwe coalitie moet andere basis krijgen dan Paars 1 en 2, NRC Handelsblad.

- Merkel, W., Petring, A., Henkes, C., & Christoph, E. (2008). Social democracy in power: The capacity to reform. Routledge.

- Meyer, H., & Rutherford, J. (2012). The future of European social democracy: Building the good society. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Newman, J. (2013). Performing new worlds: Policy, politics and creative labour in hard times. Policy and Politics, 41(4), 515–532. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557312X655693

- OECD. (2012). Economic outlook 2012.

- PvdA. (2007). De Scherven Opgeveegd: Een Bericht aan onze Partijgenoten. Report of the Vreeman committee, Den Haag: PvdA.

- Randall, N. (2009). Time and British politics: Memory, the present and teleology in the politics of New Labour. British Politics, 4(2), 188–216. https://doi.org/10.1057/bp.2009.4

- Rutte, M., & Asscher, L. (2013). Troonrede 2013. Retrieved January 1, 2019, from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/toespraken/2013/09/17/troonrede-2013.

- Rutte, M., & Samsom, D. (2012). Bruggen slaan; regeerakkoord VVD-PvdA [Building Bridges; Coalition Agreement VVD-PvdA]. The Hague: Ministry of General Affairs.

- Ryner, M. (2010). An obituary for the third way: ‘The financial crisis and social democracy in Europe’. The Political Quarterly, 81(4), 554–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-923X.2010.02118.x

- Schmidt, V. A. (2002). Does discourse matter in the politics of welfare state adjustment? Comparative Political Studies, 35(2), 168–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414002035002002.

- Schumacher, Gijs (2012) ‘Modernize or die’? Social democrats, welfare state retrenchment and the choice between office and policy [Doctoral dissertation, VU University Amsterdam]. https://research.vu.nl/en/publications/modernize-or-die-social-democrats-welfare-state-retrenchment-and-.

- Sitalsing, S. (2014, November 14). PvdA heeft geen idée waar het voor staat. de Volkskrant.

- Suyker, W. (2015). Tekortreducerende maatregelen 2011-2017. CPB.

- Timmermans, F. (2010). Glück Auf! Het relaas van een bronsgroene Europeaan. Bert Bakker.

- Touwen, J. (2014). Coordination in transition: The Netherlands and the world economy, 1950–2010. Brill.

- Trouw. (2012, February 21). Vertrek Cohen is niet meer dan symptoombestrijding, de PvdA zit in ongekende crisis. Trouw.

- Valk, G. (2007, June 2). Witte arbeider, waar bent u?; PvdA'ers over de crisis in hun partij. NRC Handelsblad.

- Verbraak, C. (2014, December 20). Ik stam uit de tijd van zwart en wit. NRC Handelsblad.

- Waard, P. d. (2006, May 20). Wouter Bos, nieuwe darling van derde weg. De Volkskrant.

- Watson, M., & Hay, C. (2003). The discourse of globalisation and the logic of no alternative: Rendering the contingent necessary in the political economy of new labour. Policy & Politics, 31(3), 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557303322034956

- Weezel, M. v. (2016, January 20). Hoe juist banen de achilleshiel van Asscher werden. Vrij Nederland.

- Wöltgens, T. (1998). De ideologie van Paars. Socialisme & Democratie, (9), 371–376.

- Zwaap, R. (1999, November 10). Waarheen leidt de weg? De Groene Amsterdammer.